Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

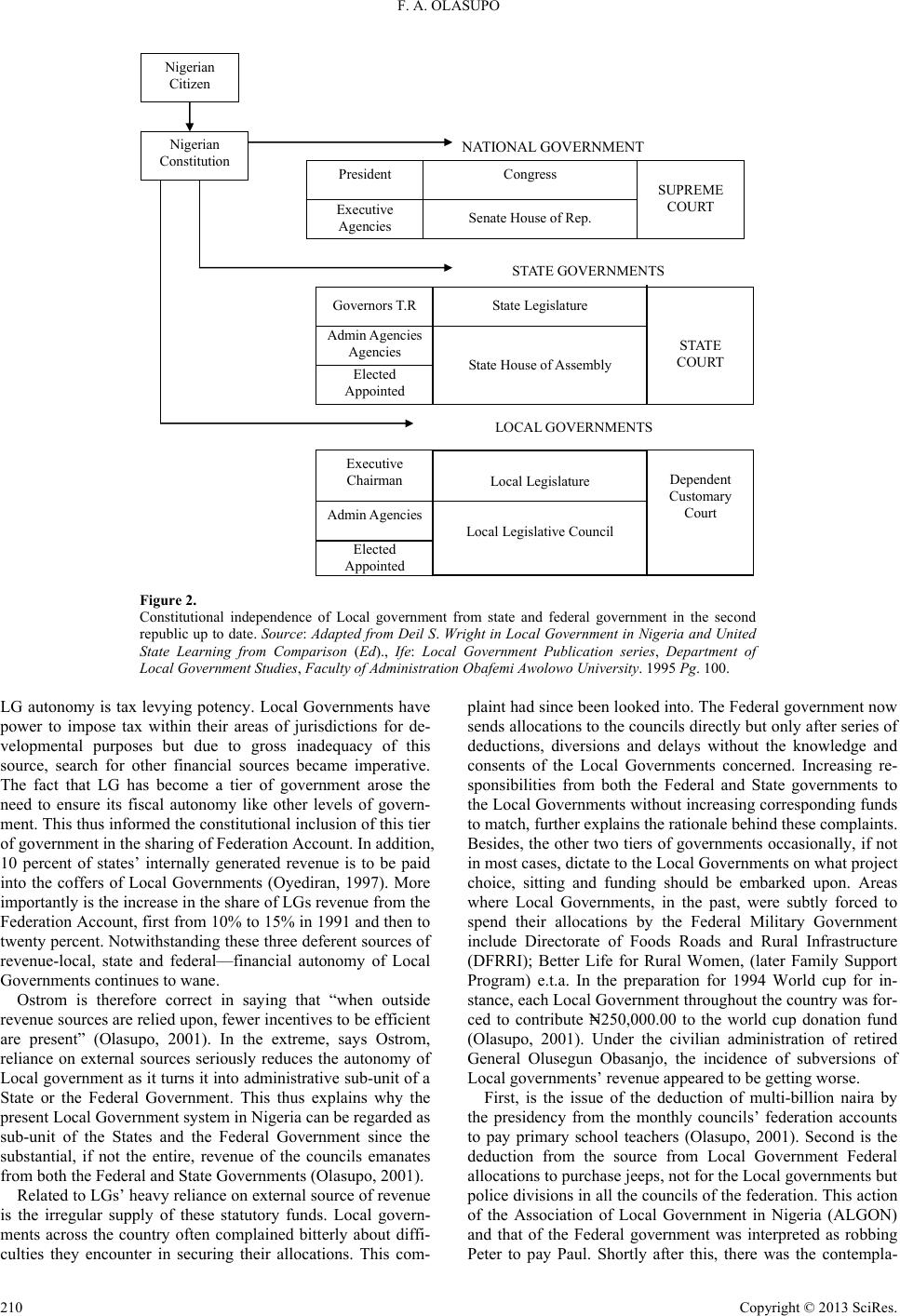

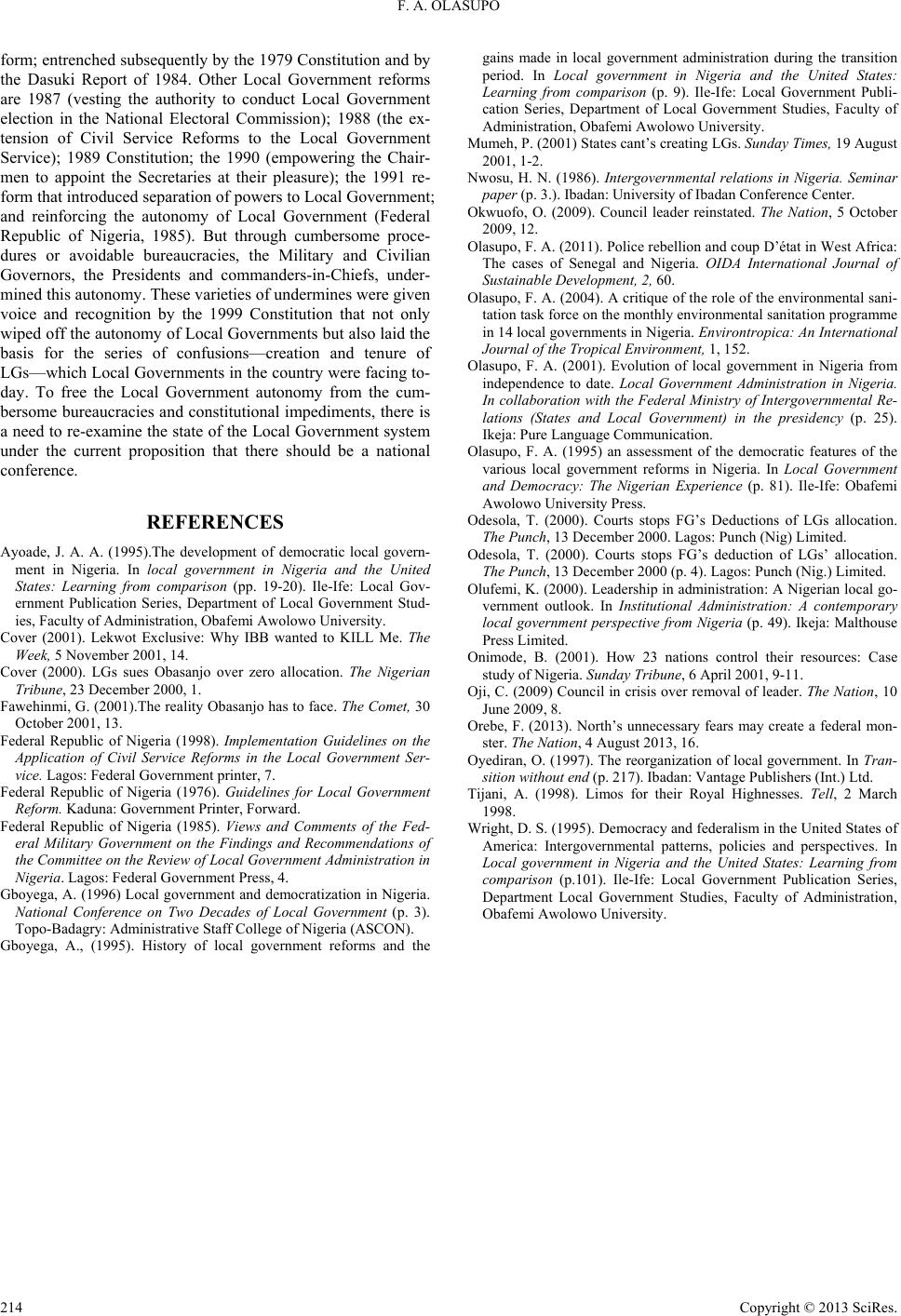

Advances in Applied Sociology 2013. Vol.3, No.5, 207-214 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2013.35028 Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 207 The Scope and Future of Local Government Autonomy in Nigeria F. A. Olasupo Department of Local Government Stud i es, Faculty of Administration, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Email: faolasupo@yahoo.com Received July 4th, 2013; revised August 4th, 2013; accepted August 11th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 F. A. Olasupo. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The crisis of Local Government autonomy in Nigeria is a recurrent issue. How much autonomy this third tier of government possesses is unclear and uncertain to the extent that it engenders the problem of meas- urement. In other words, what are the defining characteristics of Local Government autonomy? How can it be evaluated and measured? Keywords: Local Government; Autonomy; Revenue; Federation Account; Deductions Introduction Across these three epochs—colonial, independent and post independent—variants of Local Government in Nigeria exer- cised some degrees of autonomy. These enabled them to em- bark on some developmental projects, however rudimentary these might be. But it was 1976 Local Government Reform that categorically expressed the fact that “Local Government should do precisely what the word government implied”. That is gov- erning at the grass-roots or local level (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1976). Implied in this statement, there is the substantial degree of autonomy which the Local Governments are to enjoy under the newly reformed Local Government system. Deil S. Wright identifies five parameters by which local autonomy and indeed democratic participation can be measured in any Local Government system. These are a) political tradi- tion, b) finance, c) geographic distance, d) local political initia- tive and leadership, and e) electoral realities (Wright, 1995). But the sixth one in the case of Nigeria where the constitution recognizes Local Government as a third tier of government is separateness. How has the decentralization process impacted on these? In short, this paper aims to study the local government autonomy in Nigeria. Analysis of Concepts Generally, three concepts attract our attention here—Sover- eignty, Autonomy, Local Government, and Local Government autonomy. Sovereignty Section 14 subsection 2A of the 1999 constitution says “Sovereignty belongs to the people of Nigeria from whom the government derives its authority and power” (Fawehinmi, 2001). If “Local Government should therefore do precisely what the word government implies i.e. governance at the grass- root or local level” it presupposes that government at the local level should be sovereign at that level. This is because sover- eignty at the local level should belong to the local people from whom the government at the local level should derive its au- thority and power. However, this contradicts the prevailing situation in Nigeria where State/Provincial governments, in certain circumstances appoint Local Chief Executives. Such appointed or nominated Local Chief Executives come under different appellations such as “Sole Administrator”, “Council Manager System”, “Care- taker Committee”, and “Electoral College or Cabinet System” (Olasupo, 2001). Autonomy Autonomy, according to Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictio- nary, is control over one’s own affairs; independence. The Dic- ti onary illustrated the meaning thus: a campaign for greater auto- nomy. Branch managers have full autonomy in their own areas. Local Government Federal Military Government, in 1976 Nationwide Local Government Reform, recognized “Local Government as the third tier of governmental activity in the nation”. Providing a working definition for Local Government System in Nigeria, it defined it thus “Local Government should do precisely what the word government implies i.e., governing at the grass-roots or local level” (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1976). Local Government Autonomy Olowu says Local Government should have some degree of sovereignty or what some people call autonomy. Local Gov- ernment autonomy could therefore be defined as the ability of the Local Government to take some political, economic and social decisions without recourse to any of the two superstruc- tures—State and Federal Governments. Elements of Local Government Autonomy As identified by Wright, there are seven elements in Local  F. A. OLASUPO Government’s autonomy: Separateness, Government, Taxation, Political tradition, Local Political Initiative and Leadership, Geographic distance and Electoral Realities. Lack of any of these, diminishes the autonomy of Local government because each has different contents that enhances or diminishes local autonomy. Separateness This is one of the elements of local government on which decentralization process has significantly impacted. It has to do with Local Government as governmental entity separate from the two other superior levels of government—State and Federal Governments. And this is recognized by the constitution. It should therefore have its own sovereignty, autonomy or free- dom. Federations all over the world can be categorized into two—young and old. The young ones comprises of India, Bra- zil Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico, Russia and China. Old fed- erations on the other hand include former West Germany but now Germany due to the unification between her and former East Germany, United States of America, Canada, Australia, Switzerland and Bosnia, formerly known as Yugoslavia. Nigeria should belong to the young federations but it can hardly be categorized here because of its radical deviation from one of the basic principles of Federalism. In ideal federal sys- tem, Local Government affairs are placed under Provincial or State government. The power to create and abolish Local Gov- ernment resides with them (Provincial or State government). But the opposite is the case with Nigeria federalism. The affairs of Local Government in Nigeria (e.g. creation, abolition and finance) are placed under concurrent list. In Nigeria, States or Provincial governments are empowered by the constitution to create Local Government but approval must be given by the Federal Government. As a matter of facts all the 774 Local Governments in Nigeria have their names enshrined in the con- stitution. To create or abolish Local Government therefore re- quires impute of both the National and Provincial Assem- blies—a cumbersome and difficult process. This cumbersome- ness places limitation on the local autonomy. Femi Orebe cap- tured it more accurately when he said: “Nigeria is the only federation in the whole world where the federal government decides how, where and when a local gov- ernment council must run. In all civilized countries and in all democratic countries, it is the state and or provincial or regional government that legislate on local government” (Orebe, 2013) Federal Government also almost exclusively finances Local Government in Nigeria. These constitutional confusions seri- ously and negatively impact on Local Government’s autonomy in Nigeria. The main cause of these constitutional confusions is hinged on the fact that Nigeria is about the only federation in the world with three-tiered federal system; in which Local Government is a separate entity from the other two levels of government (Onimode, 2001). The constitution of the country recognizes this as such. Government I976 Local Government Reform categorically stated that Local Government system in Nigeria is a tier of government. It is therefore expected “to do precisely what the word govern- ment implies i.e. governing at the local level”. But it could not. Things which “government” at the local level in Nigeria does can be categorized in to three: 1) regulatory role, 2) provision of social services and 3) legislative functions. The extent to which these roles are performed without interference from two other levels of government, measure the genuine Local Gov- ernment autonomy. But the two superior levels of government do interfere. 1) Regulatory role that LGs perform include the control of certain social activities such as vigilante, sales of alcohol, en- vironmental exercise and night parties etc. Vigilante and Envi- ronmental exercise are two basic sources of conflicts between the Local Government and the two other levels of government. State and Local Governments are not permitted by Federal governments to have State or Local police. Before independ- ence, Local governments under Regional governments had local police. However, at independence, this was abolished (Olasupo, 2011). Due to this, community people resorted to communities created and funded vigilante; but they regularly clash with Federal law enforcement agents. The same for envi- ronmental exercise which was exclusive preserve of the Local Government. It was, initially, Local government affair, particu- lar in during the colonial period and the first Republic. Federal Military government, under General Buhari/Idiagbon regime in 1983, hijacked this role. But under the current civilian admini- stration, State governments are in charge; dictating to Local Governments what to do and not ought to do (Olasupo, 2004). 2) Social services delivery is however the most conflicting area in which most Local Governments often clash with their state governments particularly where such services are revenue yielding type e.g. market administration and refuse disposal. The constitution is unambiguously clear as to who is responsi- ble for these duties. But the state governments flout this consti- tutional provision and thus weaken the freedom of this level of government, especially in the areas of revenue generation. In some cases LG’s functions are hijacked completely by the state governments. 3) Legislative functions of LGs as exercised by the council- ors in the present fourth republic have been turned into weapon of undue control over the local executives. The impeachment power of the councilors, propelled by the State Governors, has been so brazenly used to intimidate the LG Chairmen to the point where they (Local Government Chairmen) could no longer freely exercise their constitutional duties. To date, quite a large number of LG Chairmen have been removed. Kaduna state started it with the removal of 10 LG Chairmen. Following Kaduna is Ondo state that has so far removed six LG chairmen: chief Dupe Ogundiminegba (Ose LG); chief Gilbert Adepoju (Ondo East LG); chief Adedayo Adesida (Ondo West LG); chief Siaka Olorunyomi (Odigbo LG); chief Ayeni Olayeye (Okiti pupa LG); and Dr. Francis Ajih (Ese odo). From Osun state the impeached chairmen include Mr. Nathaniel Arabambi (Ayedaade LG); Mr. Adebowale Olaoye (Odo-otin LG). In Oyo state, the following chairmen among others were removed: Olujide Solomon Ajao (Ibadan North East LG); Mr. Afolabi (Kajola LG). Lagos state: Engineer (Otunba) Dele Kuti(Ikorodu LG), Prince Luqman Ajose, (Lagos Island LG), Yusuf Olasun- kami, vice-chairman (Amuwo Odofin council) was suspended from of office. Others from other parts of the country such as Zamfara, Niger, Kano, Rivers, Enugu,Anambra, Kwara and Akwa Ibom states who were impeached were: Solomon Kogi, Aliu Ikara, Aliu Wara, Smaila Gurijian,Mina Cleve Tende, Sunday Anyanwa, Ben Onyin, Chuks Anah, Etheobi Okpala, Emmanuel Ebe, Opaknte Jackreese, Me. Yakubu Jesse, Ikara Bibis, Alhaji Jibrin Sabo Keana. Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 208  F. A. OLASUPO Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 209 As a matter of facts, Speakers of Local legislative councils who refused prodding of the Governors’ to initiate impeach- ment moves against recreant Local Government Chairmen were also impeached. Although there are instances of impeachments due to power struggle between the Executive Chairmen and the Speakers of Local legislative councils, the frequencies of these are low compared with State/Provincial induced impeachments. Local Speakers Leaders of local legislative councils also have their own ex- cessive politicking that result in removal of the leadership. At Nsukka Local Government, in Enugu State, the leader of Leg- islative Council, Mr. Dominic Ajibo was removed in a funny way. For a long time, the council could not sit to bring this about. On few occasions it did, it could not form quorum. Eventually, when it was time to begin the process of impeach- ing the leader, the Clerk of the Legislative Council, Mr. Joseph Ugwuanyi, ran away with the mace thus preventing members of the council from sitting. On the long run, “the council boss re- portedly invited the leader (Ajibo) to his office on Monday and asked him to resign his position in the council (Orji, 2009). The accusation made against the leader of the Legislative Council borders on corruption. The councilors in the area want to know how 2 billion naira accruing to the council from the federal allocation was spent. In the case of Akuku local government area, in one fell swoop, the entire leadership of the council was impeached. When the Chairman of Akuku-Toru local government area of Rivers State, Chief John Briggs, was found to be behind the “masterminding the change in the leadership of the legislative arm of his council”… and for declaring “six councillorship seats vacant”, he himself had to be accordingly suspended from office by the state government. Only in Lagos state had a local legislative council demon- strated its independence of the external forces by removing its leader and reinstating him back as well without the interference of the State government or any godfather. “The leader of Ifako- Ijaye Local Gove rnment Legisla tive House in Lagos State, Hon. Niyi Fadare” was impeached on September 8, 2009 (Okwuofo, 2009). Less than a month thereafter, at a plenary session of the council held on 29th September 2009 at the chamber, Iju Areas office, a legislative member, “Hon Babajide Atala, moved the motion that the House revert to the status quo” (Okwuofo, 2009). The motion was supported by Hon. Sesi Davids, and Fadare, the pardoned impeached leader of the legislative coun- cil was reinstated. He thanked his colleagues for their maturity. Technically therefore, the governmental power of Local Go- vernment is under erosion; and so is its autonomy. This shows present LGs as not different from what obtained under local administration system of the first Republic. Then, Local gov- ernment power was subjected to the control of Regional gov- ernment that was the delegating power and authority to the “Local Government” rather than the constitution under which the present system of Local Government derives its autonomy. Please see Figures 1 and 2. Taxation Next in order of importance in determining and measuring Nigerian Citizen Nigerian Constitution President Prime Minister Parliament Senate House of Rep. SUPREME COUR T County Council Local Council District Council NATIONAL GOVERNMENT Executive Agencies Governors T. R Premiers State Legislature Administrative Agencies STATE COUR T House of Assembly REGIONAL GOVERNMENTS House of Chiefs Elected Figure 1. Governments in Nigeria in the first Republic: Systems and Structures. Source: Adapted from Deil S. Wright in Local Government in Nigeria and United States: Learning from Comparison (Ed)., Ife: Lo- cal Government Publication series, Department of Local Government Studies, Faculty of Administra- tion Obafemi Awolowo University. 1995 Pg. 100.  F. A. OLASUPO Nigerian Citizen Nigerian Constitution President SUPREME COURT Executive Agencies Senate House of Rep. NATIONAL GOVERNMENT STATE GOVERNMENTS Congress STATE COURT Admi n Agencies Agencies Elected Appointed State House of Assembly State Legislature Executive Chairman Dependent Customary Court Admi n Agencies Elected Appointed Local Legislative Council Local Legislature LOCAL GOVERNMENTS Governors T.R Figure 2. Constitutional independence of Local government from state and federal government in the second republic up to date. Source: Adapted from Deil S. Wright in Local Government in Nigeria and United State Learning from Comparison (Ed)., Ife: Local Government Publication series, Department of Local Government Studies, Faculty of Administration Obafemi Awolowo Un iver sit y. 1995 Pg. 100. LG autonomy is tax levying potency. Local Governments have power to impose tax within their areas of jurisdictions for de- velopmental purposes but due to gross inadequacy of this source, search for other financial sources became imperative. The fact that LG has become a tier of government arose the need to ensure its fiscal autonomy like other levels of govern- ment. This thus informed the constitutional inclusion of this tier of government in the sharing of Federation Account. In addition, 10 percent of states’ internally generated revenue is to be paid into the coffers of Local Governments (Oyediran, 1997). More importantly is the increase in the share of LGs revenue from the Federation Account, first from 10% to 15% in 1991 and then to twenty percent. Notwithstanding these three deferent sources of revenue-local, state and federal—financial autonomy of Local Governments continues to wane. Ostrom is therefore correct in saying that “when outside revenue sources are relied upon, fewer incentives to be efficient are present” (Olasupo, 2001). In the extreme, says Ostrom, reliance on external sources seriously reduces the autonomy of Local government as it turns it into administrative sub-unit of a State or the Federal Government. This thus explains why the present Local Government system in Nigeria can be regarded as sub-unit of the States and the Federal Government since the substantial, if not the entire, revenue of the councils emanates from both the Federal and State Governments (Olasupo, 2001). Related to LGs’ heavy reliance on external source of revenue is the irregular supply of these statutory funds. Local govern- ments across the country often complained bitterly about diffi- culties they encounter in securing their allocations. This com- plaint had since been looked into. The Federal government now sends allocations to the councils directly but only after series of deductions, diversions and delays without the knowledge and consents of the Local Governments concerned. Increasing re- sponsibilities from both the Federal and State governments to the Local Governments without increasing corresponding funds to match, further explains the rationale behind these complaints. Besides, the other two tiers of governments occasionally, if not in most cases, dictate to the Local Governments on what project choice, sitting and funding should be embarked upon. Areas where Local Governments, in the past, were subtly forced to spend their allocations by the Federal Military Government include Directorate of Foods Roads and Rural Infrastructure (DFRRI); Better Life for Rural Women, (later Family Support Program) e.t.a. In the preparation for 1994 World cup for in- stance, each Local Government throughout the country was for- ced to contribute N=250,000.00 to the world cup donation fund (Olasupo, 2001). Under the civilian administration of retired General Olusegun Obasanjo, the incidence of subversions of Local governments’ revenue appeared to be getting worse. First, is the issue of the deduction of multi-billion naira by the presidency from the monthly councils’ federation accounts to pay primary school teachers (Olasupo, 2001). Second is the deduction from the source from Local Government Federal allocations to purchase jeeps, not for the Local governments but police divisions in all the councils of the federation. This action of the Association of Local Government in Nigeria (ALGON) and that of the Federal government was interpreted as robbing Peter to pay Paul. Shortly after this, there was the contempla- Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 210  F. A. OLASUPO tion, again, for another round of deduction from Local Gov- ernments statutory revenue for the procurement of a new set of jeeps for the Local Government Chairmen throughout the coun- try (Olasupo, 2001). It is ironic however that ALGON, with the set objectives of protecting the interests of the councils, could turn out to aid and abet unconstitutional acts against it (Olasupo, 2001). Thirdly, the Federal government under the civilian dis- pensation made deductions from Local Governments’ federally and monthly allocated revenue to maintain external debt ser- vicing (Olasupo, 2001). These are responsibilities which are absolutely federal government’s but were transferred to Local Government (Olasupo, 2001). In each of these cases, the Local Government Chairmen, in some states of the federation, had picked up the gauntlet. In Lagos state, for instance, the Chairman of Mushin Local gov- ernment council had withdrawn his membership of ALGON (Olasupo, 2001). In Ogun state, it took the intervention of the state Governor, Chief Olusegun Osoba, before the restive Local government Chairmen could allow the jeeps to be distributed to Divisional police officers in the state (Olasupo, 2001). The sce- nario in Ekiti state is a perfect example of how elite collaborate to subvert and undermine institutions and the people in general. The Local Government council Chairmen in Ekiti state sought and got the support of the Governor to deny the Divisional police officers the use of the Prado jeeps. Rather, the Governor was prevailed upon to provide the police with vans as alterna- tive, while the jeeps were distributed among themselves (Chair- men) (Olasupo, 2001). However, there were some brave Council Chairmen and State Governors who challenged the corrupt and unconstitu- tional attitudes of the Federal government and their collabora- tors. Some states had taken far-reaching steps by seeking re- dress in the court of law. In Oyo State, eleven Local Govern- ment Chairmen in Ibadan took Federal government to court over deductions of primary school teachers’ salaries and al- lowances from their monthly allocations. And in Ondo state, similar number of Local Government Chairmen had besieged Akure high court to obtain injunction against federal govern- ment’s deductions of their monthly allocations. In both cases, the courts had granted the prayers of the Local Government Chairmen by ordering the presidency from further deductions pending the determination of the cases (Olasupo, 2001). Federal Government is not however alone in this unconstitu- tional act. State Governments are collaborators of the federal government on the venture of subverting the financial auton- omy of the Local governments. Suffice to mention these few examples: 1) The donation of N=760,000.00 by the Military Governor of Oyo state to the Nigerian society of Engineers on behalf of Local Governments in not only Oyo State, as Erero observed, but also in Ondo and Ogun states respectively without consult- ing the Local governments. Divide the number of Local Gov- ernments in these states with the amount donated, each local government in these areas must have contributed not less than N=10,000.00 (Olasupo, 2001). 2) Towards building parties’ secretariats in Local Govern- ments headquarters, in the days of General Babangida’s admi- nistration, Kwara State Government ordered each Local Gov- ernment to contribute N=400,000.00 each, totaling N=5.6 mil- lion. 3) A colossal amount of N=32.2 million was said to have been extracted from the Local Government, through monthly levies in Borno state by Lt. Col. Maina (Olasupo, 2001). 4) This month alone (December 10, 2000) a total of N135 million was deducted from not less than six Local government councils in Delta State. The breakdown was as follow: Warri South L.G (N32.58 million); Ika South L.G. (N21.92 million); Ughelli North L.G. (N28.03 million); Sapele L.G. (N20.14 million); Ethiope L.G. (N17.61million); and Oshimili South L.G. (N14.56 million) (Olasupo, 2001). Local Government councils are equally not blameless of un- dermining their financial resources. In volumes of petitions by individuals to the Senate committee on State and Local Gov- ernment matters, which reviewed the performance of the 774 Local government councils in the country, not less than 80 council Chairmen had been referred to the police for theft of councils’ funds. Other gross financial improprieties, for which they were arrested, ranged from contract inflation, diversion of council fund to acceptance of kickbacks on contracts awarded by them since the inception of the current Fourth Republic that began on May 29, 1999 (Olasupo, 2001). The Fourth Republic Local government system is thus characterized by fluctuations, delays, diversions, deductions and embezzlements of Local governments’ statutory allocations. All these led to significant loss in the autonomy of Local Government system throughout the country. Political Tradition Political tradition of the people is another important factor that impact either negatively or positively on the autonomy of the Local Government. Where the tradition is such that allows for mass participation in political process and governance at the local level, the arena of local autonomy widens; because de- mocratic culture ensures checks and balances and ultimately stability in governance. However, Nigeria has under gone three different types of po- litical traditions that have tended to slow-down her democratic culture. These traditions are colonialism, civilian administration and the military. Colonialism Until 1945, the educated elite were completely excluded from local governance, leaving the traditional rulers, most of whom were barely literate, to dominate the affairs of Local Government. When the educated elite were later incorporated into local governance, they were subordinated to the traditional rulers who had always been the presidents of Local Govern- ment councils (Olasupo, 2001). In the 46 years of Local Gov- ernment development under colonial power therefore the auto- nomy of Local Government, if there was any at all, was abso- lutely subordinated to the regional government. Military Regime For more than 32 years that the military was in power out of 53 years of Nigeria independence, one of its land-mark contri- butions to the autonomy of Local Government was the 1976 Local Government reform that severed the traditional rulers from Local Government. Hitherto, the traditional rulers had always constituted a source of challenge to the authority and legitimacy of Local Government (Olasupo, 2001). Arising from this severance, a separate council known as traditional council or emirate council was created for the traditional rulers. It Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 211  F. A. OLASUPO should be conceded however that the separation of this council from the Local Government was not total. One, major impor- tant traditional rulers, especially in the Northern States, con- tinue to wield considerable influence on local administration. Two, the traditional councils were placed above the Local Governments even when the (traditional or emirate councils) functions were merely advisory and deliberative (Olasupo, 2001). Thirdly, the traditional or emirate councils that were placed above the Local Governments were to be maintained with financial contributions from Local Governments. But rather than the States to determine this as stipulated by the 1976 Local Government reform, Federal government took it up upon herself and mandated every Local Government to make 5% of their federal allocations available for the maintenance of the traditional rulers in their respective areas of Jurisdiction (Ola- supo, 2001). This is strange and asymmetrical to place tradi- tional or emirate council over and above the Local Government councils; given the fact that the LGs not only maintain the tra- ditional councils but also, in Alex terms, are the sole statutory organ of development at the local level. It is unconstitutional and disgusting to robe Peter to pay Paul, and make Paul master over Peter. The emergence of the military and its negative impact on not just Local Government but also State governments and other governmental institutions had the following as it corollaries: “increased centralization and nationalization of political author- ity, ascendancy of centripetal forces, greater concentration of national wealth at the national level, greater leadership initia- tives by federal government, and more dependency of the states and Local Governments on the federal government. It was fur- ther characterized with various Local Government and civil service reforms leading to the recognition of Local Government as a third tier of government” (Nwosu, 1986). This “new” fed- eralism as against the “old” (1954-1966), instituted various forms of management committees for managing Local Gov- ernment affairs at the local level. Although there were periods when elections were held, such periods were always at the eves of military disengagement for ushering in of democratic gov- ernance. But once they (the military) were back on political scene, they preferred any other method of managing local af- fairs except electoral process (Nwosu, 1986). Please see Table 1. Civilian Regime The civilian eras of 1979-1983, in the second republic and, the current fourth republic, have presented amazing spectacle of pseudo-democracy at the local level. A profound example of sham democracy at the local level in Nigeria between 1979 and 1983 was the replacement of elected councils that assume of- fice under military rule with unelected management committees appointed by the civilian Governors for the entire duration of the Second Republic (Gboyega, 1996). Although there was con- stitutional impediment to conducting Local Government elec- tion during this period the State governments could have seized the advantage of State Electoral Commissions under their con- trol if they were not benefiting from the absence of elected councils (Ayoade, 1995). The second important example is the controversy going on presently as to which level of government between the Federal and the State has power to create and determine the tenure of Local Government councils. At a meeting of all Attorney- Table 1. The statistics of local government management system between 1976- 1999. Dates Nomination/ Appointment o r Indirect ElectionCaretaker Sole Admin Elected Chairman Zero Party 1976-1979 1979-1983 1983-1984 1984-1986 1986-1987 1987-1993 1989-1991 1994-1996 1993-1994 1994-1996 1996-1997 1997-1998 1998-1999 1999 to Date Source: Ife Central Local Government. General’s of the states and that of the federal government, it was unanimously agreed that the powers to create and deter- mine the tenure of Local Governments belonged to the State Governments but the Senate ruled otherwise. The Senate posi- tion was that the business of creating Local Government is between the community seeking such council, the State House of Assembly and the National Assembly. In short, according to the Senate, section 8, subsection 3 of the 1999 constitution laid down the procedure to be followed in carrying out such exer- cise which most States have not complied with (Tijani, 1998). The deduction that can be made from this is that several years of military rule have militarized civilian administrations to the extent that in acts and utterances the civilian administrators behave like their military counterparts. In all therefore, coloni- alism, military and the civilian epochs have impacted greatly (and mostly negatively) on LG’s autonomy. Local Political Initiative and Leadership Local political initiative and leadership, as a measurement of LG’s autonomy, is another important factor in the measurement of Local Government autonomy. This has to do with the ability of the Chief executive of the Local Government as an individ- ual and the Local Government as an institution to freely initiate and execute policies. The initiative and the leadership power of the Local Government Chairmen could be measured under democratic and military dispensations. Starting from 1976 and until 1987, LG Chairmen throughout the country were elected by Electoral College systems comprising the Councilors of whom they were parts. The drama of electing the Chairmen by the councils involved the State Governors and there were two Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 212  F. A. OLASUPO ways by which this was done. One, the council could select three candidates from its own memberships list in order of pre- ference. From the list, the State government would nominate the Chairman. Secondly, the council could elect a Chairman from its own membership but such election would be subjected to ratification by the State Governor (Olasupo, 2001). The Supervisory Councilors were similarly elected by the councils and thus ascended to their positions through direct selection or mandate of other Councilors just like the Chairmen (Olasupo, 2001). The upshots of these ways of constituting the Local Government executives were, one, weak mayors as they could not be too assertive. This was more so given the 1987 reforms that designated the Secretaries to the Local Govern- ments as the Chief Executive (officers) of the Local Govern- ments. Secondly, since the Supervisory Councilors were simi- larly elected by the councils, like the Chairmen, the latter’s coordinating powers were not too great and had to depend, in Alex terms, “a great deal on their (LG chairmen) skills, the force of their personalities and the voluntary cooperation of the Supervisory Councilors”. Thirdly, the consenting authorities of the Military Governors turned out to be strangulating hold on the Local Government Chairmen since their final appointments were made by the Governors. By 1987 however, these weak- nesses in the executive authorities of the Chairmen were re- versed and enhanced by giving them the power to appoint their Supervisory Councilors and to dismiss them when necessary. More importantly, the 1988 application of the Civil Service Reform to LG service stated categorically that the Chairmen were the Chief Executives and Accounting Officers of the Lo- cal Governments (Olasupo, 2001). As the Accounting officers, the spending powers of the Chairmen were severely curtailed as individuals and as institu- tions by the same reform that designated them the Chief Execu- tives and the Accounting Officers. Besides, contracts above certain amounts could not be awarded by the three categories of Local Governments: urban, semi-urban and rural LG’s. Ap- proval must be taking from the designated State Commissioner or official in the Military Governors’ offices, or the States’ Executive Councils as the case may be (Gboyega, 1995). This loop hole was however seized upon by the State governments to force LGs to make central purchases which further reinforced the erosion of LGs autonomies; regardless of the introduction of the presidential system to the Local Government level and the power to pass the LGs budgets (Gboyega, 1995). The au- thority to pass the budget locally was intended to render, in Alex terms, “obsolete and in-operative the financial control which the States use to have to sanction the award of contracts beyond a certain value”. Geographic Distance Geographic distance as a factor in Local Government auto- nomy has to do with the situation where there are hundreds of kilometers between the Local Governments headquarters and the neighboring towns and villages that constitute the Local Governments. This is more so where there is ineffective com- munication system. Most LGs in the North are in this situation. For instance, up to 1980, Kachia LG in Kaduna state was the largest in Nigeria. It stretches from the periphery of Kaduna state to the boundary with Suleja in Niger state. Ditto Jema’a LG (Mumeh, 2001). But both LGs have now been broken down into smaller Local Government. Further efforts made to solve the problem of geographic distance were the recommendation of Dasuki Committee report that a population of between 25,000 and 50,000 within a Local Government should qualify for a Development Area Office (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1988). Where the problem of geographic distance is not prop- erly addressed it could lead to lack of quick and effective deci- sion making and implementation which could concomitantly impact on Local Government autonomy. Electoral Realiti e s Finally, electoral realities are the last but not the least con- tributors to Local Government autonomy. “Electoral realities” refer to the fact that direct election by popular vote gives lo- cally elected officials a substantial degree of influence and, at times, even significant control over their supposed “superior” at the State and National levels (Cover, 2001). The political man- date so directly received from the whole electorate was a con- scious emulation of that at the State and Federal levels. As the President of the country has the entire country as it constituency and the State Governors have their respective states as their constituencies, so do the Local Government Chairmen should have their entire Local Governments as their constituencies. This was therefore a significant departure from the old order where the primary constituencies of the Chairmen were their various wards. By this arrangement however, LG Chairmen have acquired Executive authorities required of Chief Execu- tive at the local level in line with the spirits of 1976 Reforms, the 1979 Constitution and the Dasuki Report of 1984 (Gboyega, 1996). The realization that Local Governments are corporate or statutory bodies emboldens some LGs to take legal actions against the States and the Federal Government to protect their constitutional rights. First, on the issue of LGs functions which the State governments have always encroached, especially re- fuse disposal, most LGs have taken them to court and court decisions have always favored them. Calabar Local Govern- ment is a good example here (Olasupo, 1995). When Federal Government was flouting the principle of Revenue Allocation, eleven LGs from Oyo State and another eighteen LGs from Ondo state respectively took the Federal Government to court and won their cases though the Federal Government continues to disregard court rulings (Olasupo, 2001). As a collectivity, all Local Government Chairmen in Nigeria through their Associa- tion of Local Governments in Nigeria (ALGON) sued the State Governments for undue interference in their autonomy (Ola- supo, 2001). Thus, severally and collectively, Local Govern- ments have been exploiting democratic environment, however meager, to assert their independence from the other two tiers of government; a situation that was not possible under the military regime. Indeed when the military regimes, especially that of Babangida, was, in Kola Olufemi’s terms, toying with the autonomy and vitality of Local Governments by balkanizing, interfering and dismissing elected Local Government Chairmen, attempt was ma de by Dr. Emmanuel Orji of Enugu LG to seek legal redress (Olufemi, 2000). Although he was militarily blocked from doing so; the point was made. Observation and Conclusion The autonomy of Local Government councils in Nigeria was expressly stated by the 1976 land mark Local Government re- Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 213  F. A. OLASUPO Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 214 form; entrenched subsequently by the 1979 Constitution and by the Dasuki Report of 1984. Other Local Government reforms are 1987 (vesting the authority to conduct Local Government election in the National Electoral Commission); 1988 (the ex- tension of Civil Service Reforms to the Local Government Service); 1989 Constitution; the 1990 (empowering the Chair- men to appoint the Secretaries at their pleasure); the 1991 re- form that introduced separation of powers to Local Government; and reinforcing the autonomy of Local Government (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1985). But through cumbersome proce- dures or avoidable bureaucracies, the Military and Civilian Governors, the Presidents and commanders-in-Chiefs, under- mined this autonomy. These varieties of undermines were given voice and recognition by the 1999 Constitution that not only wiped off the autonomy of Local Governments but also laid the basis for the series of confusions—creation and tenure of LGs—which Local Governments in the country were facing to- day. To free the Local Government autonomy from the cum- bersome bureaucracies and constitutional impediments, there is a need to re-e xamine the state of the Local Government system under the current proposition that there should be a national conference. REFERENCES Ayoade, J. A. A. (1995).The development of democratic local govern- ment in Nigeria. In local government in Nigeria and the United States: Learning from comparison (pp. 19-20). Ile-Ife: Local Gov- ernment Publication Series, Department of Local Government Stud- ies, Faculty of Administration, Obafemi Awolowo University. Cover (2001). Lekwot Exclusive: Why IBB wanted to KILL Me. The Week, 5 November 2001, 14. Cover (2000). LGs sues Obasanjo over zero allocation. The Nigerian Tribune, 23 Decem ber 2000, 1. Fawehinmi, G. (2001).The reality Obasanjo has to face. The Comet, 30 October 2001, 13. Federal Republic of Nigeria (1998). Implementation Guidelines on the Application of Civil Service Reforms in the Local Government Ser- vice. Lagos: Federal Government printer, 7. Federal Republic of Nigeria (1976). Guidelines for Local Government Reform. Kaduna: Government Pri n t er, Forward. Federal Republic of Nigeria (1985). Views and Comments of the Fed- eral Military Government on the Findings and Recommendations of the Committee on the Review of Local Government Administration in Nigeria. Lagos: Federa l G ov e rnment Press, 4. Gboyega, A. (1996) Local government and democratization in Nigeria. National Conference on Two Decades of Local Government (p. 3). Topo-Badagry: Administrative Staff College of Niger i a (ASCON). Gboyega, A., (1995). History of local government reforms and the gains made in local government administration during the transition period. In Local government in Nigeria and the United States: Learning from comparison (p. 9). Ile-Ife: Local Government Publi- cation Series, Department of Local Government Studies, Faculty of Administration, Obafemi Awolowo University. Mumeh, P. (2001) States cant’s creating LGs. Sunday Times, 19 August 2001, 1-2. Nwosu, H. N. (1986). Intergovernmental relations in Nigeria. Seminar paper (p. 3.). Ibadan: University of Ibadan Conferen ce Center. Okwuofo, O. (2009). Council leader reinstated. The Nation, 5 October 2009, 12. Olasupo, F. A. (2011). Police rebellion and coup D’état in West Africa: The cases of Senegal and Nigeria. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development, 2, 60. Olasupo, F. A. (2004). A critique of the role of the environmental sani- tation task force on the monthly environmental sanitation programme in 14 local governments in Nigeria. Environtropica: An International Journal of the Tropical Environment, 1, 152. Olasupo, F. A. (2001). Evolution of local government in Nigeria from independence to date. Local Government Administration in Nigeria. In collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Intergovernmental Re- lations (States and Local Government) in the presidency (p. 25). Ikeja: Pure Language Communication. Olasupo, F. A. (1995) an assessment of the democratic features of the various local government reforms in Nigeria. In Local Government and Democracy: The Nigerian Experience (p. 81). Ile-Ife: Obafemi Awolowo University Press. Odesola, T. (2000). Courts stops FG’s Deductions of LGs allocation. The Punch, 13 December 2000. Lagos: Punch (Nig) Limited. Odesola, T. (2000). Courts stops FG’s deduction of LGs’ allocation. The Punch, 13 December 2000 (p. 4). Lagos: Pu nch (Nig.) Lim ited. Olufemi, K. (2000). Leadership in administration: A Nigerian local go- vernment outlook. In Institutional Administration: A contemporary local government perspective from Nigeria (p. 49). Ikeja: Malthouse Press Limited. Onimode, B. (2001). How 23 nations control their resources: Case study of Nigeria. Sunday Tribune, 6 April 2001, 9-11. Oji, C. (2009) Council in crisis over removal of leader. The Nation, 10 June 2009, 8. Orebe, F. (2013). North’s unnecessary fears may create a federal mon- ster. The Nation, 4 August 2013, 16. Oyediran, O. (1997). The reorganization of local government. In Tran- sition without end (p. 217). Ibadan: Va nt a ge P ub l is he rs (Int.) Ltd. Tijani, A. (1998). Limos for their Royal Highnesses. Tell, 2 March 1998. Wright, D. S. (1995). Democracy and federalism in the United States of America: Intergovernmental patterns, policies and perspectives. In Local government in Nigeria and the United States: Learning from comparison (p.101). Ile-Ife: Local Government Publication Series, Department Local Government Studies, Faculty of Administration, Obafemi Awolowo University. |