Open Journal of Social Sciences 2013. Vol.1, No.3, 23-32 Published Online August 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss) DOI:10.4236/jss.2013.13004 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 23 A Study of Social Engineering in Online Frauds Brandon Atkins1, Wilson Huang2 1Department of Criminal Justice, Moultrie Technical College, Tifton, USA 2Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminal Justice, Valdosta State Univers ity, Valdosta, USA Email: jbatkins@vald o st a.edu Received July 16th, 2013 ; revised August 17th, 2013; accepted August 21st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Brandon Atkins, Wilson Huang. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the origina l w o rk is properly cited. Social engineering is a psychological exploitation which scammers use to skillfully manipulate human weaknesses and carry out emotional attacks on innocent people. This study examined the contents of 100 phishing e-mails and 100 advance-fee-scam e-mails, and evaluated the persuasion techniques exploited by social engineers for their illegal gains. The analyses showed that alert and account verification were the two primary triggers used to raise the attention of phishing e-mail recipients. These phishing e-mails were typically followed by a threatening tone via urgency. In advance-fee e-mails, timing is a lesser concern; potential monetary gain is the main trigger. Business proposals and large unclaimed funds were the two most common incentives used to lure victims. The study revealed that social engineers use statements in positive and negative manners in combination with authoritative and urgent persuasions to influence in- nocent people on their decisions to respond. Since it is highly unlikely that online fraud will ever be com- pletely eliminated, the most important strategy that can be directed to combat social engineering attacks is to educate the public on potential threats from perpetrators. Keywords: Advance-Fee Scam; Internet Fraud; Online Fraud; Phishing; Social Engineering Introduction The notion of social engineering has appeared recently in the study of online fraudulent activities (Blommaert & Omoniyi, 2006; Holt & Graves, 2007; Huang & Brockman, 2011; King & Thomas, 2009; Mann, 2008; Ross, 2009; Workman, 2008; Zook, 2007). This stream of research has centered on the exploitive nature of deceptive communications employed by social engi- neers in the commission of fraudulent acts. Accounts of such acts are built on the assumption that people fall victim to scams because they are ignorant, naïve, or greedy (King & Thomas, 2008). This study, instead, would suggest that neither gullibility nor ignorance explains the success of such frauds. The study, focusing on online fraud, will show that social engineers are able to exploit human weaknesses to obtain desired behaviors and privilege information via psychologically constructed com- munications. These fraudsters can skillfully manipulate victims into an emotionally vulnerable state with a disguised, attractive e-mail. The severity and consequences of online frauds warrant an analysis of this type of crime. According to the Consumer Sen- tinel (US Federal Trade Commission, 2008), 221,226 com- plaints concerning Internet-related fraud were filed by consum- ers in 2007, up from 205,269 in the previous year. E-mail com- munication plays an important role in Internet crimes. In 2008, the Internet Crime Report (National White Collar Crime Center, 2008) revealed that e-mail was the most frequent contact me- thod used by perpetrators of Internet fraud (74%) The total dollar loss in 2009 for all referred cases of Internet fraud was $559.7 million which is up $295.1 million from the previous year. The average monetary loss in 2009 was $575, while some advance-fee scams reported average losses of up to $1500 (The Internet Crime Complaint Center, 2009). The emotional impact and lingering effects on victims scammed by computer fraud can also be grave. Some phishing victims can suffer from dis- orders ranging from embarrassment to depression, which some psychologists liken to post traumatic stress disorder (Carey, 2009). The Federal Trade Commission reported that 31% of identity theft victims who had credit cards taken out in their name required over 40 hours to correct credit issues and faced consequences such as harassment by creditors (48%), loan re- jections (25%), and criminal investigations (12%). According to data retrieved from the Internet Crime Complaint Center, the median loss filed per victim was the highest among check fraud ($3000), confidence fraud ($2000) and Nigerian advance-fee fraud ($1650). In one rare and extreme case, a British man committed suicide when victimized by an Internet money- laundering scam (BBC News, 2004). The Social Engineering Perspective The most direct discussions on social engineering can be found in applied psychology (Long, 2008; Mann, 2008; Raman, 2008; Thompson, 2006; Workman, 2008). The term “social engineering” involves a process of deceiving people into giving away confidential information. Social engineers run a type of “con game” to scam people. Social engineers are individuals who intentionally mislead and manipulate people for personal benefit (Huang & Brockman, 2011). Mann (2008) defines so- cial engineering as “to manipulate people, by deception into giving out information, or performing an action” (p. 3). A number of tactics are employed by the social engineer to impact  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 24 the emotional state of the victim, consequently influencing their willingness to disclose personal information (Workman, 2008). Social engineering attacks can occur at the corporate or indi- vidual level. By use of deception, social engineers obtain per- sonal information, commit fraud, or gain computer access (Thompson, 2006). Gaining access to or control of an information system is not the only goal of a social engineering attack. Other goals may include gaining money or other valuable items, such as finan- cial records. A Social engineer greatly depends on his/her abil- ity to develop a trusting relationship with the target (Mitnick & Simon, 2002; Thompson, 2006). Social engineering attacks take place at both the physical and psychological level. The most common locations for the social engineer to seek unau- thorized information and access and work toward a psycho- logical attack include the workplace, telephone, trash cans, and the Internet. Psychological attacks focus on persuasion, imper- sonation, ingratiation, conformity, and friendliness (Workman, 2008). Social engineers rely on cognitive biases or errors in the mental process to initiate and execute their attacks (Raman, 2008) and produce automatic emotional responses in their vic- tims. Cognitive biases may include choice supportive bias, exposure effect, and/or anchoring (Raman, 2008). Choice sup- portive bias is when an individual has a tendency to remember past experiences as being more positive than negative (Mather, Shafir, & Johnson, 2000). For example, an individual who pur- chases items on eBay may unintentionally enter his/her credit card information to a fraudulent site posing as eBay, claiming they have not received payment on a purchased item. Confir- mation bias states that people will collect and interpret informa- tion in a way that confirms their views (Nickerson, 1998). For example, if employees regularly see custodians in specific uni- forms they may not be alarmed at the site of an imposter wear- ing the same uniform. Therefore, the social engineer is able to gain access without having to identify himself/herself. Expo- sure effect claims that people like items and people that are familiar to them (Zajonc, 1968). For instance, someone who is involved with online social networks may be more willing to visit a malicious website claiming to have an “online dating service”. Anchoring suggest that a person focuses on identify- ing a noticeable trait (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). For exam- ple, fraudulent websites displaying identical logos of actual banks may deceive visitors. Some common social errors can arise from fundamental at- tribution bias, salience effect, and pressing conformity, com- pliance, and obedience. Fundamental attribution error states that individuals assume the behaviors of others and directly reflect permanent characteristics, which define the person (Gil- bert & Malone, 1995). Therefore, social engineers try to make a positive first impression in order to gain the trust of their victim. However, Huang and Brockman (2011) also revealed that so- cial engineers have used persuasive statements in either positive or negative tones—or both—to attack online users. The sali- ence effect suggests that a person who stands out the most in a group is the least influential person (Taylor & Fiske, 1975). This is why social engineers are experts at fitting in to their surroundings. Pressures of conformity, compliance, and obedi- ence cause people to change their behaviors (Raman, 2008). Social engineers have learned to predict the responses to these pressures. By using authority and manipulation, a social engi- neer may pretend to be an executive, and even without provid- ing identification may convince an employee to give over cru- cial information. Social engineers use cognitive biases and social errors to help them devise the best approach for an attack. A person’s awareness or recognition plays a large role in their decision making process. A person who is perceived to be bad is gener- ally avoided, whereas a person that is good or familiar tends to be accepted. Social engineers use this to their advantage by presenting themselves in a positive manner and making good first impressions. With the knowledge of cognitive biases and errors, social engineers have discovered new techniques to influence behavior. Categorie s o f Soc i a l Engineering Social engineering can be divided into two different catego- ries: computer-based deception and human-interaction-based deception. In both methods, before the social engineer conducts an attack, they perform some kind of background research on their target. One example is to simply walk into an organiza- tion’s facilities and read names off the information board. These boards will usually provide helpful information, includ- ing department names and sometimes the names department heads. Another approach to background research is the practice of dumpster diving—simply going to the target organization’s trash cans and analyzing the contents. If people and organiza- tions are not too careful about what they throw away in the trash, the contents of their trash cans may prove valuable to a social engineer. In the computer-based approach to deception, the social en- gineer relies on technology to deceive the victim into supplying the information needed to fulfill the purpose. For example, this can be performed through the use of fake pop-ups that trick victims into believing they must reveal passwords in order to remain connected to the organization’s computer network. The authorization information is then sent off to the social engineer, who can use this information to gain access to the organization network (Gulati, 2003). The human-interaction approach of social engineering is based primarily on deception through human interaction. The attack becomes successful by taking advantage of the victim’s natural human inclination to be helpful and liked (Gulati, 2003). This can be performed through various forms of impersonation. For example, the social engineer can pose as a repairman, IT- support person, fellow employee, manager, or trusted third party in order to gain the victim’s trust and thus unauthorized access to desired information. Types of Social Engineering Attacks The variation and extent of social engineering attacks are only limited by the creativity of the hacker (Manske, 2000). These attac ks prove to be effect ive because t hey target the most vulnerable link of any organization, its people. Social engi- neering attacks have the potential to bypass the best technical security and expose an organization’s critical information. There are numerous types of social engineering attacks; a few include Trojan e-mail and phishing messages, advance-fee fraud, impersonation, persuasion, bribery, shoulder surfing, and dumpster diving. Among them, Trojan e-mail and phishing messages are two of the most common examples of social engineering attacks.  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 25 They are technical attacks in nature, but they actually rely on strategically constructed messages to lure victims to open at- tachments or click on embedded hyperlinks. This makes these classic examples, which assist technical exploits, a very com- mon feature in many social engineering attacks. According to Manske (2000) these attacks serve as stepping stones to the attacker’s ultimate goal, which could be, for example, complete control of an organization’s network servers. Phishing e-mails or Trojan attacks can be employed to collect private informa- tion or system credentials, or potentially to compromise the security of the user’s operating system by installing malicious software that allows the attacker full access to the system. In 2007, phishing attacks accounted for more than a quarter of all reported computer crimes (Richardson, 2007). Another common technique employed by social engineers is the use of fake credentials. This can be a simple ploy executed by printing fake business cards, or a more elaborate tactic such as creating counterfeit identification cards or security badges. The use of contemporary technology has made it easy to create hard-to-detect duplicates of identification cards. With that in mind, attackers do not always need to create the most realistic looking fake credentials as they are able to sell a good story to go with it. According to Applegate (2009), in one vulnerability assessment, an attacker created a very simple green plastic badge with a commonly seen recycling symbol. When caught going through the dumpsters by the organization’s security personnel, the attacker assumed the role of a recycling coordi- nator doing a compliance inspection. The attacker claimed that, because the organization was not sorting its recyclable waste aside, the company leadership could be subject to a large fine from the government (Applegate, 2009). As a result of this simple trick, supervisors from the organization personally en- sured all paper products were separated off to the side for the remainder of the assessment. Each day the social engineer re- turned to collect presorted paper products and sorted through them at leisure to look for any information of value. This at- tacker was so successful at this trick that he was given a tour of the organization later in the week and was able to come and go at will once personnel got used to seeing him on a daily basis. Social Engineers can utilize various techniques to imperson- ate a person. Attackers will often conduct impersonation attacks by calling personnel in the target organization on the telephone, pretending to be coworkers from a different department, re- porters, or even students doing research. Social engineers will even carry out impersonation attacks in person by walking into a selected organization utilizing fake credentials or a good story to elude security. Additional techniques frequently employed by social engi- neers are persuasion attacks. Persuasion attacks consist of the social engineer tricking a person into giving critical information or to assist the attack in a different way. Oftentimes the victim is persuaded into believing the attacker is doing him/her a favor in some way. The victim, then, feels obligated to assist the at- tacker even when organizational policies may be violated. In a variation of this attack, the social engineer uses persuasion techniques to have the employee bypass company procedures in order to hurry up the process or bypass the problem alto- gether. Types of Online Fraud Some of the more common forms of online fraud are credit card fraud, identity theft fraud, web and e-mail spoofing (re- ferred to as phishing), IM spimming (similar to spoofing, but involving the use of instant messaging), high-tech disaster fraud, and online hoaxes (referred to as advance-fee fraud) (Harley & Lee, 2007; McQuade, 2006). While considerable time could be spent on each form of fraud, the current work primarily focuses on web and e-mail spoofing (phishing) and online hoaxes (ad- vance-fee fraud), since these are two of the most well-known and recognizable scams involving a variety of deceptive tech- niques exploited in online communications. Phishing Phishing is a growing area of Internet fraud with the number of victims on the rise. In 2007, the number of US adults who reported receiving phishing e-mails was 124 million, up from 109 million in 2005 (Litan, 2007). According to Jakobsson and Meyers (2007: p. 1), phishing is a form of social engineering in which the attacker (or phisher) fraudulently retrieves confiden- tial or sensitive information by imitating a trustworthy or public organization. Phishing, sometimes called brand spoofing, in- volves the use of e-mails that originate from businesses with which targeted victims have been, or are currently associated. In the past few years there has been an alarming trend both in the increase and complexity of phishing attacks. Some of the most common businesses and industries associated with phish- ing include banks, online businesses (e.g., eBay and PayPal), and online service providers (e.g., Yahoo and AOL). Unsus- pecting victims receive e-mails that appear to be from these entities, usually suggesting suspicious activity regarding the account and requesting personal information (e.g., personal identification numbers, credit card numbers, and social security numbers). The phisher ultimately seeks to use the victim’s per- sonal information for individual gain (Larcom & Elbirt, 2006). The e-mails convince up to 20 percent of recipients to respond to them, sometimes leading to financial losses, identity theft, and other forms of fraud (Kay, 2004). Association with certain types of “brands” is an effective technique that allows scam- mers to steal information directly or be able to use social engi- neering to persuade users to disclose financial information (James, 2005; Harley & Lee, 2009). Phishing Operations Two basic methods are commonly employed by phishers to steal valuable personal identification (APWG, n.d.). The first method is the technical artifice method, which involves infect- ing personal computers with malicious software. This software is capable of recording keystrokes entered by the user, and sending that information to the phisher. This software can also redirect Internet users from legitimate websites to false ones via a remote connection. The next method that phishers employ is social engineering, which, is defined by Yoo (2006) as “gaining intelligence through deception or also as using human rela- tionships to attain a goal” (p. 8). Phishers using social engi- neering techniques employ deceptive devices to trick Internet users into a situation where they are willing to disclose sensi- tive information. Usually, the social engineering methods launch a false e-mail urging the receiver to click on a linked website appearing to come from a genuine business. After clicking the link, the user is actually brought to a fraudulent site asking for personal financial information such as credit card or  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 26 bank account numbers. Phishers then use the records they ob- tained to swindle money from the credit card or bank account, or even apply for a new credit card with a false identity. Phishing tactics and targets vary in social engineering appli- cations. While some simpler e-mails contain fill-in forms, other more complex ones direct victims through a variety of synthetic websites. As phishing is performed mostly for financial reasons, the most commonly attacked sector in 2009 was financial ser- vices, which accounted for 74% of reported phishing activity for that year (Symantec Corporation, 2009). The next most active area of phishing was the Internet service provider, at 9%. Although fraudsters are not as likely to produce monetary gains in this area, it is likely that they are able to use the stolen in- formation and accounts to further their phishing activities, such as sending mass e-mails through the stolen accounts. The third most lucrative segment for phishers is retail, accounting for 6% of phishing attacks. Phishers attempt to purchase goods online and request that the items be shipped to a location which the phisher has access to. The Symantec study (2009) revealed that the difference between financial scams (74%) and all other areas (26%) lies in the relative ease and immediate financial reward for successful deception. One common feature that phishing e-mail messages at- tempted to do is to imitate a creditable entity. Some fraudsters use tricks to make their e-mails seem more legitimate. These tricks include the use of company logos, hyperlinks to the home page of the company, false return addresses. The next step in the phishing process is to create a message that requires the recipient to take a specific action, such as replying to the phish- ing e-mail, completing a form provided by the e-mail, or click- ing on a guided link. The content within the messages vary, with the most common form claiming to require information for account verification or security upgrade. Because fraudulent web- sites and e-mail messages are detected quickly and subse- quently blocked, the messages are typically written to instill a sense of urgency in the reader. Criminals push for their victims to respond immediately by threatening termination of the ac- count if a reply is not received promptly (MailFrontier, 2004). After the users have clicked the fake link and entered into the spoofed site, it is essential that the web pages appear authentic to the user. The deceptive online features used by phishers in- clude company logos and slogans, page layouts, fonts, and co- lor schemes (MailFrontier, 2004). Many online phishers are not only effective in replicating the graphic look of legitimate web- sites, but also in adding some of the indicators users typically look for a website’s security and authenticity. These include the use of a safety padlock in a menu bar, an https device in the URL, and a “TRUST-e” symbol (University of Houston, 2005). In earlier days, one could examine a website’s URL and be more confident of detecting a counterfeit site; since early phishers used domain names that were only similar to the valid company they were spoofing. Today’s fraudsters, however, can make the company’s actual domain name visible, such as www.ebay.com, but when the user clicks on the hyperlink it really directs them to the phisher’s website. Advance-Fee Fraud As it has been demonstrated criminals use the Internet to commit all types of fraud; however, the largest dollar losses are attributed to advance-fee fraud e-mail messages. These mes- sages are sent from individuals claiming to need assistance moving a large sum of money out of their country. Receivers of these messages who respond often become victims of fraud and identity theft. There has been a large amount of criminological research that has explored the prevalence and incidence of fraud, where criminals gain property or money from victims through deception or cheating. Most fraud involves some type of interaction between the victim and the offender, either through face-to-face meetings, or telephone-based exchanges (Holt & Graves, 2007). As individuals around the world have increasingly become dependent on the Internet, criminals have begun to use it as a means to commit fraud (Wall, 2001). Advance-Fee Fraud Operations Advance-fee fraud gets its name because these schemes re- quire the victim to pay the scammer in advance with the prom- ise of receiving rewards later. This scam is neither the most costly nor frequent Internet crime; however, it remains to be the most ubiquitous and well-known of all cyber-crimes. Nigeria 419 scams are a very common type of advance-fee fraud where scammers generally claim to be from Nigeria and execute a variety of deceptive schemes that require victims to front money (Microsoft, 2009). Scams like the Nigeria 419 scam are frequently carried out from areas such as local cyber cafes, which have become the target of more recent raids from Nige- ria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (Lilly, 2009). Nonetheless, Internet scammers often remain undeterred by law enforcements efforts (Goodman & Brenner, 2002). The circum- stances in Nigeria illustrate the conditions created by lenient laws and enforcement concerning the Internet. Advance-fee fraud initially appeared as handwritten letters in postal mail or faxes in the 1980s (United States Department of State, 1997). These scams began to spread via e-mail in the early 1990s as individuals began adopting e-mail technology. In the past decade, advance-fee schemes have been labeled as spam, or unsolicited bulk e-mails with multiple messages that offer illicit or counterfeit services and information (Wall, 2004). Although there may be individuals who act alone to initiate contact and sol icit informati on, the scammers gene rally work in small teams with a specialized division of labor. Nigerian scammers are different than con artists who hope for a quick score by taking their gain in a single transaction—known as a short con. Nigerian scammers work on a long con, one designed to play out over time and gradually drain a victim’s assets. Contrary to public perceptions, the goal of most Nigerian ad- vance-fee fraud scams is not to simply empty a bank account by immediately obtaining financial information as some other scams do. Rather than obtaining a quick score, the scammers intend to draw increasingly large sums from the victim, who is manipu- lated into looking for additional sources to supply them. The relationship between the scammer and the victim can drag out for months, and the transformation can be complex (NExT, 2007). The US Secret Service (n.d.) adds that, if carried to the conclusion, the victim often will be enticed to come to Nigeria for the final financial coup de grace. Advance-fee scams have many variants, but they all share the same essential characteristics. First, a large sum of money will become available because of some tragic event. Most of the time the event will be very specific, such as a plane crash, ma- jor catastrophe (World Trade Center in 2001 or the Earthquake  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 27 in Haiti 2010), an auto accident, political conflict, or a fatal disease. Usually they will include legitimate names of the wealthy victim. This allows the scammer to provide a URL link to a legitimate source that confirms both the accident and the actual death, providing credibility. Second, the scammer reports that the money remains unclaimed and provides reasons why swiftness is needed in order to claim it, and secrecy needs to be maintained to protect the project. Third, a reason for the need to rush the transfer, usually be- cause of political conflict or a looming deadline in which the money will be given back to the bank or government, adds a sense of urgency to the transaction. Fourth, the scammer always implies that the transaction needs help from a foreigner in order to evade laws, or outsmart others who are also after the funds, or to avoid leaking that the fortune exists. This is done to em- phasize the compelling requirement of secrecy. Finally, the direct attempt to establish direct personal contact between the scammer and the recipient comes. Occasionally, this may be a direct request for information, including personal details and bank account number and bank’s routing number. However, in most variations, the scammer initially requests only a reply, which can lead to extended email exchange or phone calls (Sturgeon, 2003). In some circumstances, the e-mail will in- clude attachments containing pictures or other information to improve credibility. However, the attachments may also contain malware that includes spyware or worms capable of extracting the recipient’s e-mail address book or allowing the users’ PC to be used to rela y fu rther e-mails through a legitimate system. Given the unlikely scenarios, it might seem implausible that any Internet users, most likely people with some sophistication and basic literacy skills, would fall victim to the scams. At least with increasing visibility and awareness of the scam, it would seem that, the prevalence of vi ctimizatio n woul d decrease. Nev- ertheless, victimization continues to increase. The Internet has greatly expanded the pool of potential vic- tims while reducing the costs of committing fraud. These and other factors have resulted in deceptive e-mails being sent out to an estimated 10 million-plus recipients worldwide daily, which is a very conservative estimate (King & Thomas, 2008). Scammers send out large numbers of e-mails in order to capture the relatively small number of respondents who are attentive to the persuasions embodied in the e-mails. The investigation be- low attempts to address what deceptive techniques have been used in scam e-mails. Generally when studying crime, re- searchers will focus on the motivations of the offender. Instead of focusing on motivations, this study investigates the persua- sive techniques that drive victims to fall for the online fraud- sters’ scams. Methodology To examine the deceptive operations and techniques used in phishing and advance-fee e-mails, the study has collected a sample of 200 fraudulent e-mails related to the two types of scam. These e-mails were gathered from a data archive main- tained by an anti-phishing site, MillerSmiles, in Great Britain, and also from the inbox of the researchers. A total of 100 phishing e-mails were gathered from the MillerSmiles site, and another 100 advance-fee e-mails were gathered collectively from the MillerSmiles site, as well as the researcher’s mail inboxes. No overlap in the collected data existed between the two sets of e-mails. The archived e-mails were used to increase the number and diversity of the sample e-mails The 100 phishing e-mails were strategically gathered from the MillerSmiles site. The MillerSmiles site offers an alpha- betical listing of company names. At the bottom of the home- page they offer a list of top targets by scams. From her e , the to p three targets were selected (PayPal, eBay, HSBC bank) and to have one main banking institution from the United States and the UK, Bank of America and Abbey bank were chosen. In order to gather 100 e-mails, 20 were collected from each insti- tution. For each of the five institutions, e-mails were selected be- tween 6/08/2010 (the day that the e-mail extractions began) and 6/08/2009 (retrospective to the previous 12 months). The Mil- lerSmiles site offers a collection of 300 e-mails for each institu- tion. All e-mails between the aforementioned dates were print- ed and then numbered, selecting every 5th e-mail for the sam- ple. If any e-mail was repetitive or used any language other than English a rotation would be skipped (e.g. if e-mail 5 is the same as e-mail 1, e-mail 5 is skipped and e-mail 10 is the next to be chosen) until 20 e-mails were reached for a chosen insti- tution. Once 20 e-mails were selected for each institution, the e-mails were printed and coded based on the codebook created for this study. Another 100 e-mails for advance-fee frauds were gathered from the inboxes of the researchers as well as the MillerSmiles website. Due to the low number of advance-fee e-mails on the MillerSmiles site, only 15 e-mails were gathered, with the other 85 e-mails coming from the researchers’ inboxes. The selection criteria and process for the previously mentioned 85 e-mails were consistent with that of prior studies (Blommaert & Omoniyi, 2006; Ross, 2009; Huang & Brockman, 2011). The criteria were the e-mails had to be written in English despite grammatical errors or typos found in the text; they had to ap- pear to be full letters, showing an e-mail address, subject line, salutation, body text, and closing; and they had to reflect the sender’s control of funds, power of monetary distribution, and knowledge of scheme procedures. Spamming e-mails that did not fit into solicitations for personal privileged information or monetary funds were excluded. For example, these exclusions included e-mails promoting low home mortgage rates, brand- name products at extremely low prices, online dating, online drugs, sex enhancement pills, and x-rated entertainment. Measuring Triggers and Persuasions Each of the 100 phishing e-mails were read and coded based on triggers. Triggers can be defined as the main reason or sub- ject of the deceptive e-mail. In phishing mails, these triggers can be an account update, account verification, account suspend- sion/disabled/frozen etc. Triggers for the 100 advance-fee e- mails were coded based on incentives. Incentives are classified into five types according to the e-mail content: Nigeria 419 funds, lottery winning, working at home, job offer, and busi- ness proposal. Eight types of persuasive techniques were applied to the 200 e-mails. These techniques were authority, urgency, tradition, fear/threat, attraction/excitement, pity, politeness, and formality. Definitions of these persuasions are based on Capaldi (1971), Huang and Brockman (2011), and Ross (2009). After coding the e-mails, the collected data were entered into Microsoft Ex- cel and then transferred into SPSS. Definitions of the persua- sions are provided below.  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 28 1) Authority: Persuasive statements used to create legitimacy, trust, and credibility. Institutional markers such as affiliations and professional titles are included; 2) Pity: Refe rs to sy mpa thy an d char ity expressed i n th e mes- sages; 3) Tradition: An appeal to ideal values such as honor and legacy comm onl y rec ognized by the public; 4) Attraction: An incentive which can draw excitement or a sense of subversive joy. Examples of attraction include huge cash prizes, easy job offers, or opportunities for profits; 5) Urgency: A stress on the exigency of the situation. Urgent statements are used to stress the requirement to respond promptly to receive the offer or award. They can also be stated in a nega- tive tone, such as threat to disable account if a request is not fulfilled in tim e; 6) Fear/threat: Used to intimidate the reader. Examples of fear/threat include; threat to delete account, freeze account, or suspend account; 7) Politeness: Used to construct the author as a real human being. Examples of politeness would be the use of please, thank you, et c.; 8) Formality: Professional terms used to convince the reader that the letter is legitimate and safe. Examples of formality include the use of confidentiality, safety, etc. Social engineers take advantage of all elements of the e- mails they send. One need not to read the body of the e-mail to see the persuasive phrases social engineers use. Often the sub- ject line, the title of the e-mail which highlights the main con- cern, contains such words as alert, warning, attention, and up- date followed by exclamation points to strike fear in the reader. Sometimes, social engineers use friendly salutations (e.g., Dear Valued Customer/Member) and closures (e.g., Best Regards, Sincerely, Thank you) to make a positive first impression and familiar appearance. Regardless of the approach used by scam- mers, the e-mails always show institutional affiliations. The authors have to enhance fundamental attributions to encourage recipients to comply with the e-mails’ request for action (Gil- bert & Malone, 1995). Results Table 1 identifies the triggers that were used in phishing Table 1. Triggers used in phishing e-mails (N = 100). Triggers % Security upgrade/update of account 13% General (unspe cified) upg rade/update of account 6% Alert, warning, attention 18% Account verif i cation 18% Account suspension/disabled/frozen 8% Purchase confirmation 8% Invalid logi n attempts 17% Identity ve r i fi cation 5% Other 7% Total 100% mails. The top three triggers used by scammers were: alert, warning, attention (18%); account verification (18%); and inva- lid login attempts (17%). Phishers often use triggers that catch the reader’s attention and immediately cause a sense of fear. For example, senders of fraudulent e-mails will include subject lines such as “NOTIFICATION OF LIMITED ACCOUNT AC- CESS” or “Attention Your Account Has Been Violated!” to strike immediate fear in the reader. The “others” category is made up of triggers such as policy violation, purchase cancella- tion, reward offer, complete survey, leave feedback, and auc- tion response. Due to the low frequency of occurrences these categories were grouped into one category for better analysis. Scammers also use urgent statements to persuade readers to reply quickly to their e-mails. Table 2 portrays that 71% of the phishing e-mails expressed urgent statements. For example, senders will include statements like “you have to log-in within 48 hours after receiving this notice to re-update your Internet banking account for urgent review,” “You have 3 days to con- firm account information or your account will be locked,” and “You have 24 hours to click on the link below and confirm your PayPal personal information, otherwise your ATM Debit/ Cre- dit Card access will become restricted.” Other words like “ASAP”, “account suspension”, “account deleted”, “new mes- sage waiting”, and “new bill” are used sometimes followed by multiple exclamation points to instill a sense of urgency in the recipient. Table 2 also shows that fear/threat is used in 41% of the phishing e-mails. Using fear/threat allows the phishers to de- mand readers to respond, for fear that not responding in a timely manner will result in unwanted consequences. For ex- ample, senders will use phrases such as “failure to verify ac- count will lead to account suspension,” “your account has been limited,” and “due to an unusual number of login attempts, we had to believe that, there might be some security problem on your account.” Senders will often inform the users of why they have received the messages, command the users to take proper action and threaten them with unwanted consequences if they do not comply immediate ly. This logical sequence is consiste nt with the notions of conformity, compliance, and obedience (Huang & Brockman, 2011). Polite statements are often used in phishing e-mails as a way to build a friendly relationship between the phisher and the potential victim. Seventy-four percent of the phishing e-mails used polite statements. Sometimes, social engineers use friendly salutations (e.g., Dear Valued Customer/Member) and closures (e.g., Best Regards, Sincerely, Thank you) to make a positive first impression and familiar appearance. Scammers will sometimes use formality in their e-mails to make the reader feel safe. Of the e-mails analyzed, 55% used formality to at- Table 2. Persuasions used in phishing e-mails (N = 100). Types of Persuasions % Yes Authority 100% Urgency 71% Fear/Threat 41% Politeness 74% Formality 55%  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 29 tempt to establish a trusting relationship with the reader. Phish- ing e-mails will often use confidential statements or the use of safeguards to ensure the reader that no one else will be able to see the information except for the “trusted entity”. For example, senders often include statements like “it may contain confiden- tial or sensitive information” or “Unauthorized recipients are requested to preserve this confidentiality”. Table 3 details the average number of persuasions used across the triggers types in phishing e-mails. The triggers with the greatest mean number of persuasions utilized included: account suspension, disabled, or frozen (4.50); invalid login at- tempts (4.18); and identity verification (3.80). The grand mean suggests that scammers have used 3 or 4 persuasions on aver- age per phishing e-mail. Further analyses were conducted to examine the average number of persuasions used per e-mail by financial institutions. The three greatest means were found in PayPal (3.75), Bank of America (3.75), and Abbey Bank (3.70). An ANOVA test was administered to test differences of group means amongst institutions, the results showed no statistical significance. Results suggest that the average number of per- suasions used by phishers did not differ by the financial ta rgets that they had chosen. Table 4 displays incentives used in the advance-fee fraud e-mails. As the data show, fraudsters use Nigeria 419 funds (46%) and business proposals (41%) most often. Unlike phish- ing e-mails, advance-fee e-mails use direct incentives such as large sums of money, work-from-home jobs, and business op- portunities to attract the attention of recipients. Table 5 exemplifies the persuasions used in the 100 ad- vance-fee e-mails collected for this study. Just as phishing e- mails use authority to create an image of legitimate entity, ad- vance-fee e-mails also use authority as a way to develop legiti- macy. However, persuasions are used more elaborately in ad- vance-fee fraud e-mails. Social engineers attempt to explain the nature and source of the funds in detail in order to convince the reader that the offer is legitimate. As shown in the collected mails, social engineers pretend to be executives of corporations, attorneys, retired FBI officials, and doctors in order to further their credibility. Eighty-four percent of the advance-fee e-mails Table 3. Number of persuasions used in phishing e-mails by trigger types (N = 100). Triggers Mean number of persuasions used Security upgrade/update of account 3.54 General upgr ade/update of ac count 2.83 Alert, warning, attention 3.44 Account ve ri fication 3.56 Account suspe nsion/disabled/frozen 4.50 Purchase c onfirmation 2.75 Invalid login attempts 4.18 Identity verification 3.80 Other 3.14 Grand mean 3.59 Table 4. Triggers used in advan c e -fee e-mails (N = 100). Incentives % Nigeria 419 funds 46% Lottery winning 6% Work from home 2% Job offer 4% Business proposa l 41% Payment approval 1% Total 100% Table 5. Persuasions used in adv ance-fee e-mails (N = 100). Types of Persuasions % Yes Authority 84% Urgency 70% Tradition 28% Attraction/Excitement 94% Pity 31% Politeness 78% Formality 24% used authority to persuade readers to fall for the scam. Urgent responses are critical for advance-fee fraudsters to scam their readers. If readers do not reply quickly, scammers run the risk of being caught and shut down. Of the e-mails re- viewed 70% expressed urgent statements. Urgent responses used in advance-fee fraud e-mail are similar to those used in phishing e-mails. For example, social engineers will add state- ments like “Please I want you to quickly help me out of this bad situation because my life is not safe here,” and closing state- ments such as “waiting with thanks”. This sometimes entices the reader to hurry and respond because they believe someone’s life is in danger Tradition is sometimes used in advance-fee e-mails to trigger an emotional response from the reader. Readers will sometimes respond to fraudulent e-mails in hopes that they can help a per- son, family, or organization in need. Social engineers often use tradition along with pity, using statements such as “My late husband who was a contractor with Zimbabwan government on commercial farming was assassinated with my only son by the Zimbabwan rebel troop,” “I am contacting you because of my inheritance fund that my late mother deposited in the famous banks in Cote d’Ivoire”, and “because of the war my late father sold his shipping company and took me to a nearby country Cote d’Ivoire.” Of the advance-fee fraud e-mails coded one of the most commonly used persuasions by social engineers in advance-fee fraud e-mails is attraction/excitement. Attraction/ excitement is used in advance-fee e-mails to make readers be- lieve that they have just won a large sum of money or the op- portunity to make a large sum of money by doing little or noth-  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 30 ing in order to attain it. Ninety-four percent of all advance-fee e-mails tested used attraction/excitement. Social engineers of- ten menti on large sums of money to immedia tely cause a sense of excitement to the reader. Offers like “I was assigned by two of my colleagues to seek for a foreign partner who will assist us in the transfer of US $27,500,000.00,” and “If your company acts as the beneficiary of this fund 35% of the total sum will be for you for providing the account”. Another way attraction/ excitement is used is through the use of “lottery winnings”. Social engineers will use greetings such as “Attention lucky winner” and then go on to state “We are pleased to notify you the ‘winner’ of our Internet lottery draws.” The reader will then be instructed to give over confidential information in order to receive the la rge sum of money. Pity, another persuasive element employed by social engi- neers, is sometimes used in advance-fee e-mails to trigger a sympathetic feeling from the reader. Thirty-one percent of the e-mails analyzed used pity as a way to obtain confidential in- formation from the reader. Social engineers will fabricate sto- ries of the death of loved ones or concerns of personal safety/ health for help. Pity along with tradition is used to dramatize their story and make readers feel sympathetic. Examples of pity include “I honorably inherited from my late father Mr. D. Mummar, who the Empigigo rebels killed recently in a political crisis in our country that resulted in war” and “the above sum belongs to our deceased father who died along with his entire family in the Benin plane crash 2003.” Another persuasive element often used in advance-fee e- mails is politeness. Using polite statements allows the scammer to build a friendly relationship with the reader in hopes that the reader will reveal important information. Seventy-eight percent of the e-mails coded used politeness. Social engineers use friendly salutations and closings to make the reader feel as if there is a connection between him/her and the author of the e-mail often including text such as “Thanks for your greatest kindness,” “Thanks and god bless you and your family,” and “Please help me get out of this situation and our almighty will bless you.” Lastly, it is important for the author of advance-fee e-mails to make the reader feel that the e-mails are safe and any infor- mation given by the reader will be used for only purposes stated in the e-mail. The use of formality is used in 24% of the tested e-mails. Statements of security and confidentiality include “I wish for the utmost confidentiality in handling this transaction” and “I assure you that this transaction is completely safe and legal.” Table 6 describes the mean number of persuasions used by trigger types. The largest mean numbers of persuasions used by scammers can be found in business proposal (4.41), Nigeria 419 funds (4.11), and work from home opportunities (4.00). Overall, scammers used an average of 4 persuasions per e-mail. Among the mean differences of trigger types, the ANOVA test revealed a significance level of .028. It is suggested that busi- ness proposal, Nigeria 419 funds, and work at home involve a significantly greater number of persuasions used in advance-fee scams. Discussion and Conclusion The analysis and results revealed in the study underscores the importance of examining triggers and persuasive techniques used in social engineering attacks. The findings indicate that Table 6. Number of persuasions used in advance-fee e-mails by trigger types (N = 100). Trigger Mean number of persuasions used Nigeria 419 funds 4.11 Lottery wi nning 2.33 Work from home 4.00 Job offer 3.50 Business prop osa l 4.41 Payment approval 3.00 Grand mean 4.09 alert/warning/attention and account verification were the two primary triggers used to raise the attention of e-mail recipients. These phishing emails were typically followed by a threatening tone via urgency. In advance-fee fraud emails, timi ng is a lesser concern; potential monetary gain is the main trigger. Business proposals and large unclaimed funds were the two most com- mon incentives used to lure victims. In both phishing and ad- vance-fee emails, authority and politeness were employed widely. It seems that social engineers intend to use the combi- nation of these two persuasive techniques to increase the le- gitimacy of the e-mail and at the same time the sense of cour- tesy commonly seen in business practices. This study also discovered that social engineers have con- structed statements in positive and negative manners to per- suade readers to fall victim to their scams. Online fraudsters have used e-mails to tap into emotions such as excitement, pity and fear to affect viewers. The use of authoritative and often- times emotional persuasions has caused readers to drop their guards against potential risks. The study showed that politeness and formality were used frequently as a way to make the reader feel comfortable and secure in responding to the e-mail. By exploiting human weaknesses, social engineers have strategized and carried out emotional attacks on innocent people. As social engineers continue to get better at attacks through deceptive persuasions, potential victims need to prepare themselves for counter attacks at any given time. Social engineering attacks are easy to commit and very dif- ficult to defend against because they focus on the human factors. Since most people are usually helpful in attitude and tend to believe that this type of attack will not happen to them, they are often fooled without even knowing they have been a victim of an online fraud. The natural human tendency to take people at their word continues to leave users vulnerable to social engi- neering attacks. Ultimately, the best way to defend against so- cial engineering attacks is through education. This can be ac- complished by training users to be aware of the value of the information resources at their disposal as well as by creating awareness of human hacking techniques, which makes it easier for users to detect a social engineer. Education has been a stra- tegy used by governments and businesses to prevent online fraudulent acts. Efforts have been made by organizations to raise awareness of social engineering through speeches, pam- phlets, web pages, and the delivery of security messages in e-mails sent to users (Huang & Brockman, 2011).  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 31 Cautions have also been raised concerning the psychological effects that educational campaigns may have on users (Bardzell, Blevis, & Lim, 2007; Emigh, 2007; Mann, 2008). Looking at it from a customer’s viewpoint, banks have been perceived as security providers who are assumed to offer protection advice and warnings to users. According to Mann (2008), although the strategy used has good intentions, when a user receives new communications from the bank about security updates, he/she has been pre-programmed to follow the instructions or visit the suggested link. Since ordinary users feel ignorant when it comes to IT, they know they must follow the instructions of the experts. Users will often follow their emotions and what is familiar to them to make their decisions on what to do, usually ignoring security threats, faulty traps, or future financial losses they are facing. Expecting users to be able to distinguish be- tween a fraudulent e-mail and a legitimate e-mail and not to follow the instructions in the former is an unattainable expecta- tion (Emigh, 2007). It is very unlikely that advance-fee fraud and phishing e-mails will ever be completely eliminated. The creation of anti-spam laws such as the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 in the United States and international directives by the European Un- ion have had little impact on the volume of e-mails sent out daily (Wall, 2004). There is also no easy way to identify the fraudsters responsible for these messages due to the use of spoofing and software that conceal an individual’s location. Thus, it is difficult for law enforcement agencies to effectively deal with fraudulent e-mails. These challenges have led to a greater reliance on techno- logical defenses developed by private sectors to combat social engineering attacks. Microsoft and other computer companies have embodied phishing filters, security firewalls, and e-mail authentication devices in their online application software as frontline barriers (Brandt, 2006; Kornblum, 2006). These pro- viders are adaptive to the competitive environment and have the technical expertise to better control and monitor the flow of e-mail communications. Their supporting role in fighting online frauds has complemented many aspects of police efforts in crime prevention. As to ordinary citizens, preventative strate- gies remain the most practical and useful ones (Musgrove, 2005). These include never providing account information in response to a solicitation e-mail, constantly changing pass- words, typing or copying URL addresses from legitimate sources instead of following a hyperlink embedded in an e-mail, and calling the financial institution directly when suspicions arise from an e-mail. Overall, a basic understanding of the op- erations of social engineering attacks coupled with constant skepticism will reduce chances of victimization of such attacks. It is understandable that no easy solutions can be identified to prevent online fraud from occurring. Nonetheless, more legisla- tive efforts in the area of online fraud and computer crimes, in general, are needed. By this it is meant that there must be ade- quate statutes addressing the various computer crimes and their punishment, and consistent rulings from the courts as to how the law can be ap p lied to crimes online. Although governmental agencies are dedicating more staff and resources to the investi- gation and prosecution of computer crimes, many legal scholars question whether the legal system will be able to handle high- technology crimes in the future. In many areas it seems that technology changes faster than the laws themselves. As soon as a statute has been enacted to regulate an activity, the technol- ogy may change and the statute becomes either obsolete or no longer covers all possible activities. Therefore, education re- mains the most effective approach to prevent online frauds. Social scientists should continue their role in this approach to educate the public on potential threats from social engineering perpetrators. REFERENCES Applegate, S. D. (2009). Social engineering: Hacking the wetware. Information Security Jo u r n al, 18, 40-46. Bardzell, J., Blevis, E., & Lim, Y. (2007). Human-centered design considerations. In M. Jakobsson, & S. Myers (Eds.), Phishing and countermeasures (pp. 241-259). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. BBC News (2004). Suicide of i n ternet scam victim. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/cambridgeshire/344430 7.stm Blommaert, J., & Omoniyi, T. (2006). E-mail fraud: Language, tech- nology, and the indexicals of globalization. Social Semiotics, 16, 573- 605. doi:10.1080/10350330601019942 Brandt, A. (2006). How bad guys exploit legitimate sites (electronic version). PC World, 24, 39. Capaldi, N. (1971). The art of deception. New York: Donald W. Brown Inc. Carey, L. (2009). Can PTSD affect victims of identity theft: Psycholo- gists say yes. http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/2002924/can_ptsd_affect_ victims_of_identity.html Emigh, A. (2007). Mis-education. In M. Jakobsson, & S. Myers (Eds.), Phishing and countermeasures (pp. 260-275). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The correspondence bias. Psy- chological Bulletin, 117, 21-38. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.21 Gulati, R. (2003). The threat of social engineering and your defense against it. SANS Institute InfoSec Reading Room. http://www.sans.org/rr/papers/index.php?id=1232 Harley, D., & Lee, A. (2007). The spam-ish inquisition. ESET antivirus and security white papers. http://www.eset.com/download/whitepapers/CommonHoaxes+Chain Letters%28May2008%29.pdf Harley, D., & Lee, A. (2009). A pretty kettle of phish. ESET antivirus and security white papers. http://www.eset.com/download/whitepapers/PhishingOnline.pdf Holt, T. J., & Graves, D. C. (2007). A qualitative analysis of advance fee fraud e-mail schemes. International Journal of Cyber Criminol- ogy, 1, 137-154. http://www.cybercrimejournal.com /thomas&danielleijcc.htm Huang, W., & Brockman, A. (201 1 ). Social engineering exploi tations in online communications: Examining persuasions used in fraudulent e-mails. In T. Holt (Ed.), Crime online: Correlates, causes, and con- text (pp. 87-111). Durham, NC: Caroli na Aca demic Press. James, L. (2005). Phishing exposed. Rockland, MD: Syngress Publish- ing. Kay, R. (2004). Phishing. Computerworld, 38, 44. King, A., & Thomas, J. (2009). You can’t cheat an honest man: Making ($$$s and) sense of the Nigerian e-mail scams. In F. Schmallegar, & M. Pittaro (Eds.), Crimes of the internet (pp. 206-224). Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Educat ion. Kornblum, A. (2006). Enforcement takes the fight to the phishers. IEBlog, The Microsoft Internet Explorer We bbl og. http://blogs.msdn.com/ie/archive/2006/06/22/643173.aspx Larcom, G., & Elbirt, A. J. (2006). Gone phishing. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 25, 52-55. doi:10.1109/MTAS.2006.1700023 Lilly, P. (2009). Nigerian police crack down on scammers, shut down hundreds of websites. Max imum PC. http://www.maximumpc.com/article/news/nigerian_police_crack_do wn_scammers_shuts_down_hundreds_websites Litan, A. (2007). Phishing attacks escalate, morph and cause consider- able damage. Business Wire, Lexis Nexis Academic Database.  B. ATKINS, W. HUANG Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 32 Long, J. (2008). No tech hacking: A guide to social engineering, dump- ster diving, and shoulder surfing. Rockland, MA: Syngress Publish- ing. MailFrontier, Inc. (2004). Anatomy of a phishing email, 2004. http://www.mailfrontier.com/docs/MF_Phish_Anatomy.pdf Mann, I. (2008). Hacking the human: Social engineering techniques and security measures. Burlington, VT: Gow e r Publishing Company. Manske, K. (2000). An introduction to social engineering. Information Systems Security, 9, 53-60. doi:10.1201/1086/43312.9.5.20001112/31378.10 Mather, M., Shafir, E., & Johnson, M. (2000). Misrememberance of op- tions past: Source monitoring and choice. Psychological Science, 11, 132-138. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00228 McQuade III, S. C. (2006). Understanding and managing cybercrime. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Microsoft (2009). Scams that prom ise m one y, gifts, or prizes. http://www.microsoft.com/protect/yourself/phishing /hoaxes.mspx Mitnick, K., & Simon, W. (2002). The art of deception: Controlling the human element of security. New York, New York: Wiley Publishing. Musgrove, M. (2005). “Phishing” keeps luring victims. The Washing- ton Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2005/10/21/ AR2005102102113.html National White Collar Crime Center (2008). Internet crime report. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance. http://www.ic3.gov/media/annualreport/2008_IC3Report.pdf NExT Web Security Services (2007). 419 Nigerian advance fee fraud scam lifestyle. http://nextwebsecurity.com /419LifeCycle.asp Nickerson, R. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review o f G e ne r a l Psychology, 2, 175-220. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175 Jakobsson, M., & Myers, S. (2007). Phishing and countermeasures: Understanding the increasing problem of electronic identity theft. New York, New York: Wiley Publishing. Raman, K. (2008). Ask and you will receive. McAfee Security Journal, 1-12. Ri chardson, R. (2007). CSI survey 2007: The 12th annual computer crime and security survey. Computer Security Institute. http://www.csi.org Ross, D. (2009). ARS dictaminis perverted: The personal solicitation e-mail as a genre. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 39, 25-41. doi:10.2190/TW.39.1.c Sturgeon, W. (2003). Nigerian money scam: What happens when you reply? Silicon.com: The spam report. http://www.silicon.com/research/specialreports/thespamreport/0,390 25001,10002928,00.htm Symantec Corporation (2009). Symantec global internet security threat report trends for 2009. http://eval.symantec.com/mktginfo/enterprise/white_papers/b-whitep aper_internet_security_threat_report_xv_04-2010.en-us.pdf Taylor, S., & Fiske, S. (1975). Point of view and perception so causal- ity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 439-445. doi:10.1037/h0077095 The Internet Crime Complaint Center (2009). 2009 Internet crime re- port. http://www.ic3.gov/media/annualreport /2009_IC3Rep ort.pdf Thompson, S. (2006). Helping the hacker? Library information, secu- rity, and social engineering. Information Technology and Libraries, 25, 222-225. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: He- uristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124-1130. doi:10.1126/science.185.4157.1124 United States Department of State (1997). Nigerian advance fee fraud. Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. Washington DC: Un ited States Department of State. United States Secret Service (n.d.). Public awareness advisory regard- ing “4-1-9” or advance fee fraud schemes. Washington DC: United States Secret Service. http://www.secretservice.gov/alert419.htm University of Houston (2005) . Phishing scams. http://www.uh.edu/infotech/news/story.php?story_id=802 US Federal Trade Commission (2008). Consumer fraud and identity theft compliant data: January-December, 2007. Washington DC: Fe- deral Trade Commission. http://www.ftc.gov/semtinel/reports/semtinel-annual-reports/sentinel- cy2007.pdf Wall, D. S. (2001). Cybercrimes and the internet. In D. S. Wall (Ed.), Crime and the internet (pp. 1-17). N ew Y o rk: Routledge. Wall, D. S. (2004). Digital realism and the governance of spam as cybercrime. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 10, 309-335. Workman, M. (2008). Wisecracker: A theory-grounded investigation of phishing and pretext social engineering threats to information secu- rity. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1-27. Yoo, J. (2006). Phi shi ng: A su rvey. http://zoo.cs.yale.edu.classes/cs490/05-06b/yoo.dunne.pdf Zajonc, R. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Per- sonality and Social Psychology, 9, 1-27. Zook, M. (2007). Your urgent assistance is requested: The intersection of 419 spam and new networks of imagination. Ethics Place and En- vironment, 10, 65-88.

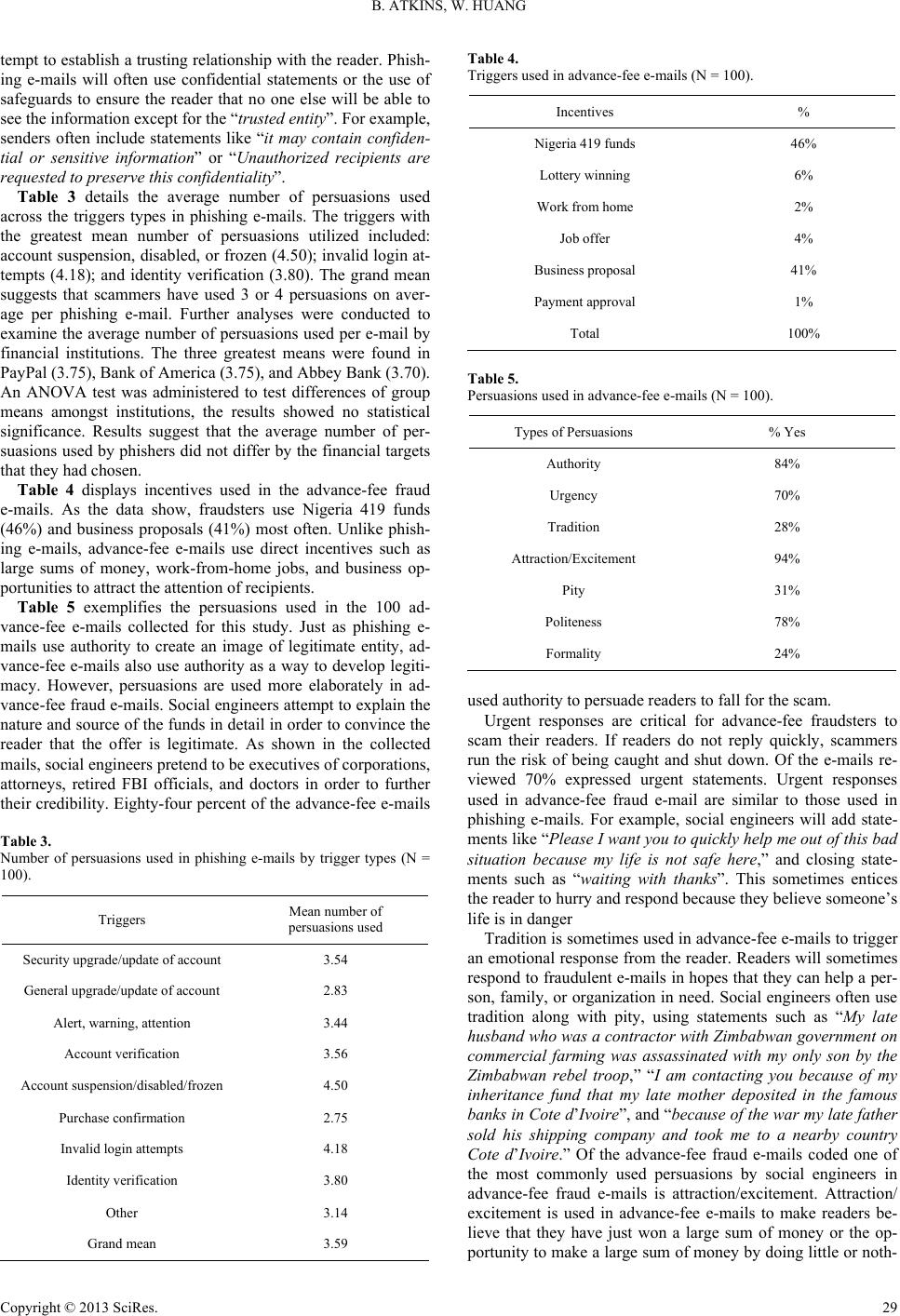

|