Vol.4, No.9, 443-448 (2013) Agricultural Sciences http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/as.2013.49059 Pre-harvest fruit bagging influences fruit color and quality of apple cv. Delicious Ram Roshan Sharma1*, Ram Krishna Pal2, Ram Asrey1, Vidya Ram Sagar1, Mast Ram Dhiman3, Mani Ram Rana4 1Division of Post Harvest Technology, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi, India; *Corresponding Author: rrs_fht@rediffmail.com 2National Research Centre for Pomegranate, Solapur, India 3IARI Regional Research Station, Katrain, India 4Pomologist and Fruit Grower, Baragaon, Kullu, India Received 9 May 2013; revised 10 June 2013; accepted 15 July 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ram Roshan Sharma et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Li- cense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT An attempt was made to observe the effect of pre-harvest bagging with spun-bound fabric bags on color and quality of Delicious apple. Bagging was done about a month before har- vesting and removed 3-day before harvesting. Bagged and non-bagged fruits were stored at 2˚C ± 1˚C and 90% - 95% RH. Observations were recorded on color and fruit quality attributes such as total phenolics, AOX activity, fruit Ca contents, LOX activity, SSC and ascorbic acid contents at harvest and during storage. Our studies have revealed that bagged fruits have better color development (Hunter “a” = 52) than non-bagged fruits at harvest (Hunter “a” = 38), which declined slightly during storage. Similarly, at harvest, bagged fruits contained high amounts of Ca (5.38 mg/100g) and total phenolics (9.3 mg GAE/100g pulp) exhibited higher AOX activity (12.6 µmoles Trolox g−1), and had better SSC and ascorbic acid contents than non-bagged fruits, and there was a decline in all recorded parame- ters during storage. Bagged fruits exhibited lower LOX activity (1.38 µmoles min−1 g−1 FW) at harvest than non-bagged fruits (2.14 µmoles min−1 g−1 FW), indicating that non-bagged fruits were more senescent than bagged fruits. Further, LOX activity increased during storage both in bagged and non-bagged apples but increase in LOX activity was slower in bagged apples than in non-bagged apples. Keyw ords: Apple; Fruit Bagging; Color; Firmness; LOX Activity; AOX Activity; Fruit Quality 1. INTRODUCTION Apple is considered as one of the most important fruit crops of the world. In India, it is the 5th most important fruit crop, which is grown primarily in hilly states like Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttrakhand, northern-eastern states and to some extent in hilly re- gions of south India. From hills, the fruits are transported to plains for storage or marketing [1]. Red colored ap- ples are preferred in the market as these attract the con- sumers. However, at lower elevations, color development is not adequate, and hence, majority of the farmers use ethrel (2-Chloroethyl Phosphonic Acid) as the pre-har- vest foliar spray for color enhancement of the fruits. Ethrel helps in the development of attractive red color in apple fruits but it causes several adverse effects. For ex- ample, it enhances fruit drop, pre-mature leaf-fall, be- sides, the harvested fruits are of poor keeping-quality, and such apples need to be harvested at a stretch to get desirable price in the market [1]. Further,apples suffer badly from several post harvest diseases and disorders during storage and transportation, for which several che- micals and fungicides are used. These chemicals and fungicides may cause severe health problems to consumers. Hence, efforts worldwide have been started to find out some non-chemical approaches to reduce the incidence of diseases and disorders in fruits including apple [2]. Of several such alternatives, pre-harvest fruit bagging has emerged as one of the best approaches in different parts of the world. In this technique, individual fruit or fruit bunch is bagged on the tree for a specific period to get desired results. It is a physical protection technique commonly applied to many fruits, which not only im- proves fruit visual quality by promoting fruit coloration but also enhances internal fruit quality [3-8]. Pre-harvest bagging of fruits has been conventionally practiced for Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. R. Sharma et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 443-448 444 fruit growing in Japan, Australia and China as well as in peach, apple, pear, grape and loquat cultivation in order to optimize fruit quality through reduced physiological and pathological disorders and for improving fruit col- oration to increase their market value [5] leading to im- proved appearance [7]. Several authors have reported contradictory results for the effects of pre-harvest bag- ging on fruit size, maturity, peel color, flesh mineral content and fruit quality, which may be due to differ- ences in the type of bag used, the stage of fruit develop- ment when it was bagged, duration of fruit exposure to natural light after bag removal (before harvesting), and/ or fruit- and cultivar-specific responses [4,9,10]. Hence, attempts have been made to observe the effects of col- ored spun-bounded fabric bags on color and quality of Delicious apple, which is most abundantly grown in India. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Experimental Site and Fruit Material This study was conducted in the Division of Post Harvest Technology, Indian Agricultural; Research Insti- tute, New Delhi-110 012, India during 2010-2012. In both the years, “Delicious” apples were bagged on-the- tree with spun-bounded light-yellow colored fabric bags, 30 days before the expected date of harvesting (15th July) every year in a private orchard at Kullu, Himachal Pra- desh (India). Such bags have performed well in terms of retention of color and other quality attributes in our pre- liminary studies. The bags were removed 3 days before the expected date of harvesting. 50 percent fruit on indi- vidual tree were bagged and rests were not bagged. Each bag treatment was given to 5 trees with three replications. Every possibility was ensured for uniform distribution of bags in the tree-directions and canopy heights. During the period of bagging, trees were subjected to routine cultural practices. 2.2. Observations Recorded and Methodology The observations on fruit color, firmness, Calcium (Ca) content, lipoxygenase (LOX) activity, and fruit quality attributes such as soluble solid content (SSC), total phe- nolics, antioxidant (AOX) activity, ascorbic acid (AA) contents were recorded in bagged and non-bagged apples at harvest. Then, apples were stored in cold storage (2˚C and 90% ± 5% relative humidity) for six months. At the end of 6th month of storage, apples were removed from cold store and observations were recorded on above- mentioned parameters. 2.2.1.Determination of Fruit Color Fruit color in apple peel was measured from 20 ran- domly selected apples. The parameters CIELab: L*, a* and b*, were measured with a CR-200b tristimulus re- flectance colorimeter (Minolta, Osaka, Japan). The pa- rameter L* indicates brightness or lightness (0 = black, 100 = white), a* indicates chromaticity on a green (-) to red (+) axis, and b* indicates chromaticity on a blue (−) to yellow axis (+). 2.2.2. Determination of Fruit Firmness Fruit firmness was determined in 20 randomly selected fruits with peel on both cheeks, using a texture analyzer (model: TA + Di, Stable micro systems, UK) using com- pression test and represented as N (Newton) (Sharma et al., 2012). Each run was a replicate of 3 samples. 2.2.3. Determination of Total Phenolic Content, and AOX Activity Total phenolics of the fruit extracts were determined by the Singleton and Rossi method [11] with some modi- fications, and expressed in mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/100g of extract. Antioxidant capacity was deter- mined by following CUPRAC method [12], and ex- pressed as μmol Trolox g−1. 2.2.4. Estimation of Ca Concentration in Fruit Fruit Ca content in bagged and non-bagged fruits were determined as per procedure of Sharma et al. [13]. After ashing, the residue was dissolved in nitric acid to a final solution concentration of 0.16 M. Fruit calcium content was measured by atomic absorption spectrophotometer. Samples of affected and normal fruit were drawn from the storage, and from each fruit, 3 - 4 mm thick longitu- dinal slices were taken, reducing the total weight of the sample to 50 - 60 g. 2.2.5. Estimation of Lipoxygenase (LOX) Activity 1) Preparation of Substrate The substrate was prepared as per the procedure des- cribed for apple by Feys et al. [14] with slight modifica- tions. First, linolenic acid (0.1 ml) was dissolved in 1 ml 0.1 N·NaOH solution. To this, 150 μL Triton-X-100 was added. The solution was emulsified in an Ultra Turrax for 2 min, and diluted to 50 ml with distilled water. Blank was prepared similarly by using substrate solution. The sub- strate and the blank were stored at 4˚C in dark until use. 2) Preparation of Crude Enzyme Extract Crude enzyme extract was prepared at 4˚C, following the method of Axelrod et al. [15] with minor modifica- tions. Diced 1 g apple fruit was homogenized in pre-chil- led pestle and mortar by mixing in ice cooled 10 ml EDTA. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4˚C and supernatant was used for assay of lipoxygenase activity. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. R. Sharma et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 443-448 445 3) Measurement of LOX Activity LOX enzyme assay was carried out as per the proce- dure of Axelrod et al. [15] with minor modifications. Firstly, 50 µL of enzyme extract was added to 2.50 µl of substrate solution in a cuvette, mixed thoroughly and absorbance was recorded at 234 nm in a spectropho- tometer (Double beam UV-VIS spectrophotometer UV5704SS) for 3 min at 30 sec interval. LOX activity was expressed as “µmoles min−1 g−1 FW”. 2.3. Statistical Design and Data Analysis The data generated for different parameters were pooled and subjected to analysis as per standard proce- dures [16]. The significance of the treatments was deter- mined by developing ANOVA and the means were com- pared by calculating critical difference (C.D.). 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 3.1. Effects on Fruit Color Results of the study have revealed that fruit bagging has significantly influenced the color development in apples. Bagged apples with light-yellow bags resulted in the development of attractive red color over non-bagged apples (Figure 1). Conversely, the yellow/green color development was suppressed by bagging. Hunter “a” value, which is indicative of red color, was much higher (52) in the bagged apples than non-bagged ones (38), which slightly decreased during storage (Figure 1). Fruit color is the basic point of attraction for the consumers. Attractive color improves the physical appearance of the fruit, which helps to get better price in the domestic or export market. Earlier studies have reported that fruit bagging in apple inhibited color development, however it has now been established that fruit bagging is an effec- Figure 1. CIB Hunter “a” values in bagged and non-bagged Delicious apples at harvest and after 6th month of storage at 2˚C ± 1˚C and 90% - 95% RH. Data are the mean of 30 fruits across three replications. Vertical bars indicate ± SE. tive way to promote anthocyanin synthesis and improve fruit coloration in apples [17,18]. It is believed that bag- ging increases light sensitivity of fruit and stimulates anthocyanin synthesis when fruits are re-exposed to light after bag removal [19,20]. Bagged fruits are capable of synthesizing anthocyanin when they were exposed to light for few days before the actual date of harvest [18]). 3.2. Effect on Fruit Firmness, Ca Content and LOX Activity Fruit firmness is an important indicator for harvesting of fruit at appropriate maturity, which also determines the post harvest life of fruit. In this study, we observed that fruit bagging has affected the fruit firmness. At har- vest, bagged fruits had higher firmness (38.6 N) than non-bagged fruits (32.0 N), and higher firmness was also maintained during storage of apples, yet it declined sharply during storage (Figure 2(a)). Only a few studies have been conducted on this aspect, which revealed that pre-harvest fruit bagging can influence the fruit firmness at harvest. For example, Bentley and Viveros [21] re- ported that fruit firmness of “Granny Smith” apples was improved by brown paper bags when done at golf-size of fruit development. However, Hofman et al. [4] reported that fruit firmness was not affected by white paper bag in mango. Further, there was a significant effect of fruit bagging on fruit Ca contents and LOX activity at harvest and during storage. Bagged fruits also maintained higher level of Ca (5.38 mg/100 g) than non-bagged fruits (4.58 mg/100g) at harvest (Figure 2(b)), and the LOX activity in the bagged fruits was much lower (1.38 µmoles min−1 g−1 FW) than non-bagged fruits (1.82 µmoles min−1 g −1 FW) (Figure 2(c)), which increased sharply with in- crease in storage period, being maximum at the end of 6th month of storage (Figure 3). Fruits contain several nu- trients, which contribute to their quality. Since fruit bag- ging is usually done in the orchard during fruit develop- ment stage, hence it may subsequently influence the nu- trient composition of fruits. For example, Kim et al. [20] reported that fruit bagging in pear helped in increasing Ca content but the contents of N and P were not signifi- cantly affected by bagging. Further, the contents of K, Ca, Mg were decreased by 9.6 %, 38.9 % and 6.7%, respec- tively [22]. Similarly, Wang et al. [23] found that Ca contents in the bagged apple fruits were higher than un- bagged ones, and the incidence of bitter pit in the bagged fruits was lower than that in the un-bagged fruits. In con- trast, bagging in “Keitt” mango reduced the Ca concen- tration in fruits [4]. However, Amarante et al. [15] re- ported that pre-harvest bagging of pear did not affect flesh content of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg. Similarly, Wang et al. [24] reported no significant effect of bagging on fruit Ca content in fruit peel of “Huangguan” pear. Lower Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. R. Sharma et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 443-448 446 (a) (b) (c) Figure 2. Fruit firmness (a), calcium content (b) and lipoxy- genage activity (c) in bagged and non-bagged Delicious apples at harvest and after 6th month of storage at 2˚C ± 1˚C and 90% - 95% RH. Data are the mean of 30 fruits across three replica- tions. Vertical bars indicate ± SE. LOX activity in bagged apples indicates that bagged ap- ples were less senescent than non-bagged apples. 3.3. Effects on Total Phenolic Content and AOX Activity Our study has revealed that fruit bagging has signifi- cantly influenced total phenolics contents, AOX activity (a) (b) Figure 3. Total phenolics (a) and antioxidant activity (b) in bagged and non-bagged Delicious apples at harvest and after 6th month of storage at 2˚C ± 1˚C and 90% - 95% RH. Data are the mean of 30 fruits across three replications. Vertical bars indi- cate ± SE. and fruit eating quality attributes such as soluble solids and ascorbic acid contents significantly (Figure 3(a)). Bagged apples contained higher levels of phenolics (9.3 mg GAE/100g pulp) and exhibited higher AOX activity (12.6 µmoles Trolox g−1) at harvest, which decreased during storage but the level was higher in bagged fruits (Figure 3(b)). Literature reveals that the effects of bag- ging on phenolic compounds of fruits have given contra- dictory information, which may reflect differences in cultivar, bagging material, date of bagging, period of bagging, date of bag removal and climatic conditions. For example, Ju et al. [19] reported that simple phenol concentration increased with bagging up to 60 days and then declined in “Delicious” apple. Similarly, Hudima and Stamper [25] reported that bagging of “Conference” pears increased some phenolic compounds such as epi- catechin and caffeic acid in skin. In contrast, Xu et al. [8] reported that the total phenolic and flavonoid contents in loquat were decreased by bagging treatments, which lowered total antioxidant capacity (AOX) of the fruit. Yet, Wang et al. [23] reported that bagging did not affect Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. R. Sharma et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 443-448 447 (a) (b) Figure 4. Soluble solids content (a) and ascorbic acid content (b) in bagged and non-bagged Delicious apples at harvest and after 6th month of storage at 2˚C ± 1˚C and 90% - 95% RH. Data are the mean of 30 fruits across three replications. Vertical bars indicate ± SE. chlorogenic acid and catechol contents of either fruit peel or flesh in “Wanmi” peach. 3.4. Effect on Eating Quality Attributes The ultimate aim of the producer is to produce fruits of better quality, and consumer also wants to have fruits of high quality. Eating quality of fruit includes attributes such as total soluble solids, acidity etc. It appears from our study that bagged apples had fairly higher level of soluble solids (13.6˚B) and ascorbic acid content (28.6 mg/100pulp) at harvest than non-bagged apples (Figures 4(a) and (b))., which decreased during storage but was maintained at a higher level than non-bagged apples. Several studies have reported increase in fruit quality attributes following fruit bagging. For example, Bentley and Viveros [21] reported that fruit sweetness of “Granny Smith” apples was improved by brown paper bags when it was done at golf-size of fruit development. Similarly, improvement in soluble solids has also been reported in loquat [8], “Red Globe” grapes [26], peach [27], guava [28], pear [29], mango [30] and litchi [31]. 4. CONCLUSION Based on these observations, it can be concluded that fruit bagging with spun-bounded fabric light-colored yel- low bags in Delicious apples is quite effective in improv- ing fruit color and maintaining fruit quality at harvest and during storage. It is a simple, cost-effective and eco- friendly technology, which has positive effects on apple fruits. REFERENCES [1] Chadha, K.L. and Awasthi, R.P. (2005) The apple. Mal- hotra Publishing House, New Delhi. [2] Sharma, R.R., Singh, D. and Singh, R. (2009) Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables by microbial antagonists: A review. Biological Control, 50, 205-221. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.05.001 [3] Kitagawa, H., Manabe, K. and Esguerra, E.B. (1992) Bagging of fruit on the tree to control disease. Acta Hor- ticulturae, 321, 871-875. [4] Hofman, P.J., Smith, L.G., Joyce, D.C., Johnson, G.L. and Meiburg, G.F. (1997) Bagging of mango (Mangifera in- dica cv. “Keitt”) fruit influences fruit quality and mineral composition. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 12, 83-91. doi:10.1016/S0925-5214(97)00039-2 [5] Joyce, D.C., Beasley, D.R. and Shorter, A.J. (1997) Effect of pre-harvest bagging on fruit calcium levels, and stor- age and ripening characteristics of “Sensation” mangoes. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture, 37, 383- 389. doi:10.1071/EA96074 [6] Tyas, J.A., Hofman, P.J., Underhill, S.J.R. and Bell, K.L. (1998) Fruit canopy position and panicle bagging affects yield and quality of “Tai So” lychee. Scientia Horticul- turae, 72, 203-213. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(97)00125-8 [7] Amarante, C., Banks, N.H. and Max, S. (2002) Effect of pre-harvest bagging on fruit quality and Postharvest phy- siology of pears (Pyrus communis). New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science, 30, 99-107. doi:10.1080/01140671.2002.9514204 [8] Xu, H.X., Chen, J.W. and Xie, M. (2010) Effect of dif- ferent light transmittance paper bags on fruit quality and antioxidant capacity in loquat. Journal of Science of Food and Agriculture, 90, 1783-1788. [9] Witney, G.W., Kushad, M.M. and Barden, J.A. (1991) In- duction of bitter pit in apple. Scientia Horticulturae, 47, 173-176. doi:10.1016/0304-4238(91)90039-2 [10] Fan, X. and Mattheis, J.P. (1998) Bagging “Fuji” apples during fruit development affects color development and storage quality. HortScience, 33, 1235-1238. [11] Singleton, V.L. and Rossi Jr., J. A. (1965) Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Ameican Journal of Enology and Viticul- ture, 16, 144-158. [12] Apak, R., Guclu, K., Ozyurek, M. and Karademir, S.E. (2004) Novel total antioxidants capacity index for dietary polyphenol and vitamins C and E using their cupric ion reducing capability in the presence of neocuproine: CU- PRAC method. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemis- try, 52, 7970-7981. doi:10.1021/jf048741x Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. R. Sharma et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 443-448 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 448 [13] Sharma, R.R., Pal, R.K., Singh, D., Singh, J., Dhiman, M.R. and Rana, M.R. (2012) Relationships between storage disorders and fruit calcium contents, lipoxygenase activity, and rates of ethylene evolution and respirationin “Royal Delicious” apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.). Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 87, 367-373. [14] Feys, M., Naesens, W., Tobback, P. and Maes, E. (1980) Lipoxygenase acitivty in apples in relation to storage and physiological disorders. Phytochemistry, 19, 1009-1011. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(80)83048-2 [15] Axelrod, B., Cheesbrough, T.M. and Leakso, S. (1981) Lipoxygenase from soybeans. Methods Enzymology, 7, 443-451. [16] Panse V.G. and Sukhatme, P.V. (1984) Statistical methods for agricultural workers. Third Edition, Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi. [17] Ritenour, M., Schrader, L., Kammereck, R., Donahue, R. and Edwards, G. (1997) Bag and liner color greatly affect apple temperature under full sunlight. HortScience, 32, 272-276. [18] Ju, Z. (1998) Fruit bagging, a useful method for studying anthocyanin synthesis and gene expression in apples. Scientia Horticulturae, 77, 155-164. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(98)00161-7 [19] Ju, Z.G., Yuan, Y., Liu, C. and Xin, S. (1995) Relation- ships among phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity, sim- ple phenol concentrations and anthocyanin accumulation in apple. Scientia Horticulturae, 61, 215-266. doi:10.1016/0304-4238(94)00739-3 [20] Kim, Y.K., Kang, S.S., Cho, K.S. and Jeong. S.B. (2010) Effects of bagging with different pear paper bags on the color of fruit skin and qualities in “Manpungbae”. Korean Journal of Horticultural Science and Technology, 28, 36- 40. [21] Bentley, W.J. and Viveros, M. (1992) Brown-bagging “Granny Smith” apples on trees stops codling moth dam- age. California Agriculture, 46, 30-32. [22] Lin, C.F. (2008) Effects of bagging on quality and nutri- ent content of “Jinfeng” pear. Journal Gansu Agricultural University, 2, 2-19. [23] Wang, Y.J., Yang, C.X. , Liu, C.Y., Xu, M., Li, S.H., Yang, L. and Wang, Y.N. (2010) Effects of bagging on volatiles and polyphenols in “Wanmi” peaches during endocarp hardening and final fruit rapid growth stages. Journal of Food Science, 75, 455-460. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01817.x [24] Wang, Y.T., Li, X., Li, Y., Li, L.L. and Zhang, S.L. (2011) Effects of bagging on browning spot incidence and con- tent of different forms of calcium in “Huangguan” pear fruits. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 38, 1507-1514. [25] Hudina, M. and Stampar, F. (2011) Effect of fruit bagging on quality of “Conference” pear (Pyrus communis L.). European Journal of Horticultural Science, 76, 410-414. [26] Zhou, X.B. and Guo, X.W. (2005) Effects of bagging on the fruit sugar metabolism and invertase activities in “Red Globe” grape during fruit development. Journal of Fruit Science, 26, 30-33. [27] Kim, Y.H., Kim, H.H., Youn, C.K. Kweon, S.J., Jung, H.J. and Lee, C.H. (2008) Effects of bagging material on fruit coloration and quality of “Janghowon Hwangdo” peach. Acta Horticulturae, 772, 81-86. [28] Singh, B.P., Singh. R. A., Singh, G. and Killadi, B. (2007) Response of bagging on maturity, ripening and storage behaviour of winter guava. Acta Horticulturae, 735, 597- 601. [29] Lin, J., Wang, J.H., Li, X.J. and Chang, Y.H. (2012) Ef- fects of bagging twice and room temperature storage on quality of “Cuiguan” pear fruit. Acta Horticulturae, 934, 837-840. [30] Watanawan, A., Watanawan, C. and Jarunate, J. (2008) Bagging “Nam Dok Mai #4” mango during development affects color and fruit quality. Acta Horticulturae, 787, 325-328. [31] Debnath, S. and Mitra, S.K. (2008) Panicle bagging for maturity regulation, quality improvement and fruit borer management in litchi (Litchi chinensis). Acta Horticul- turae, 773, 201-208.

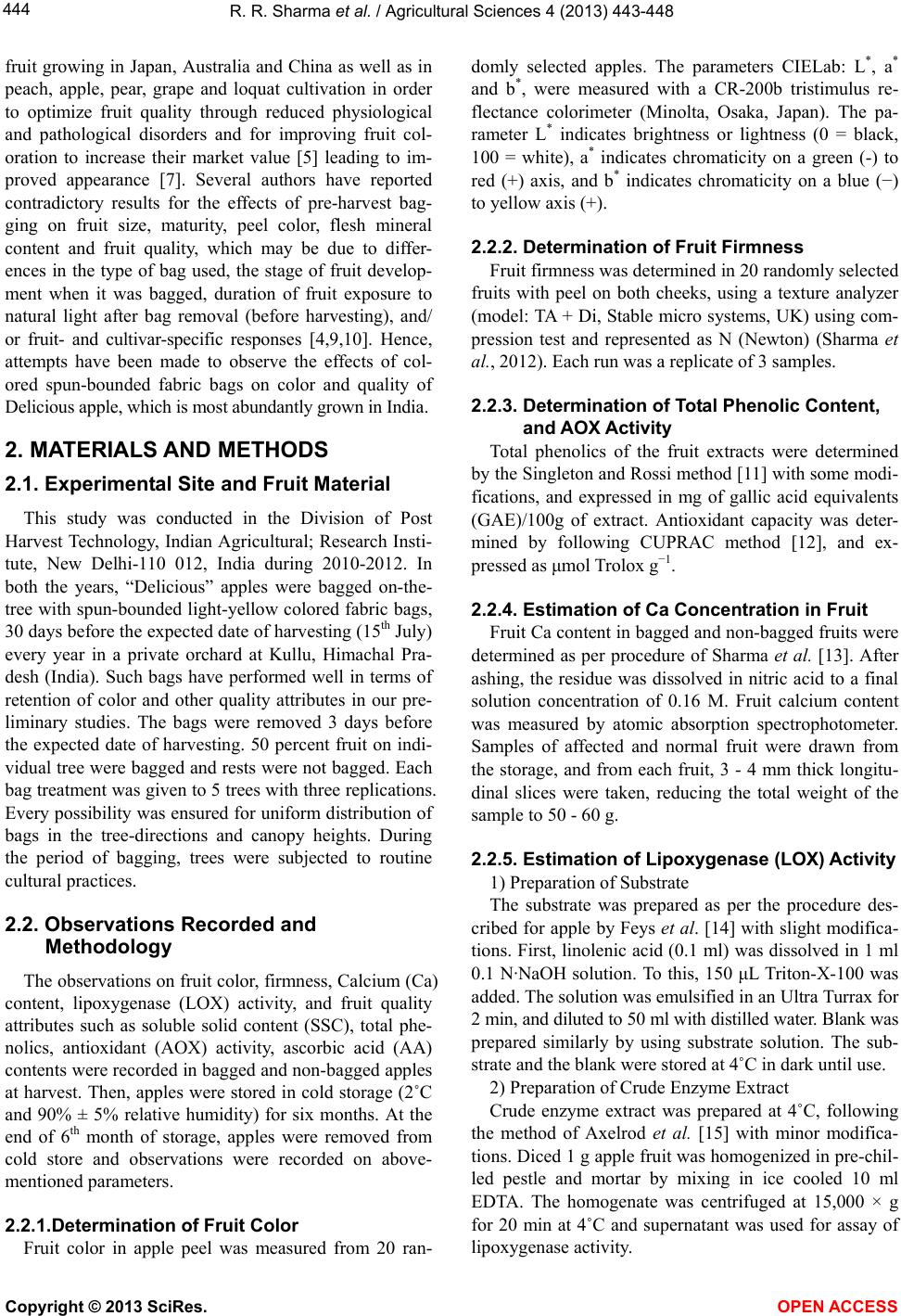

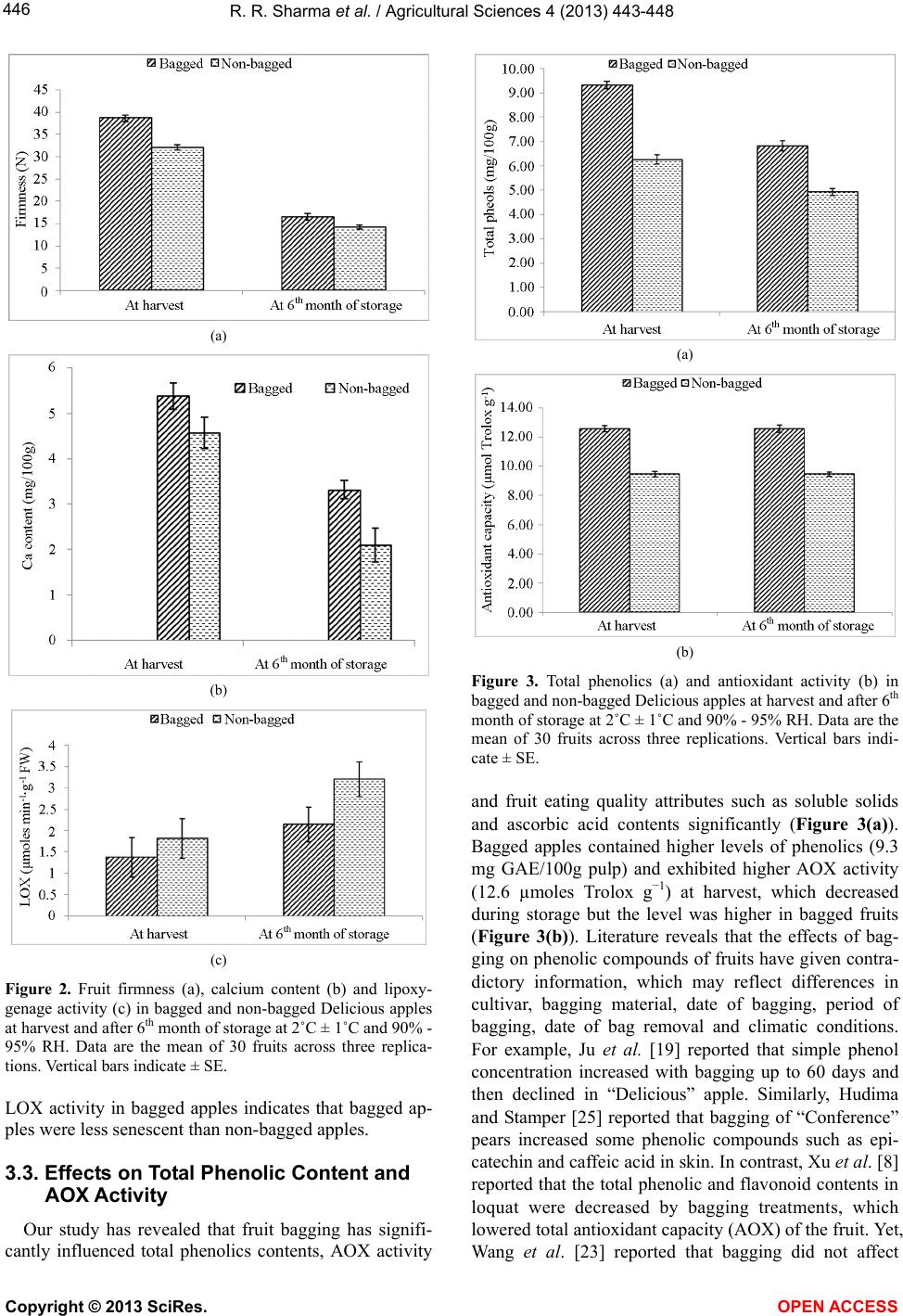

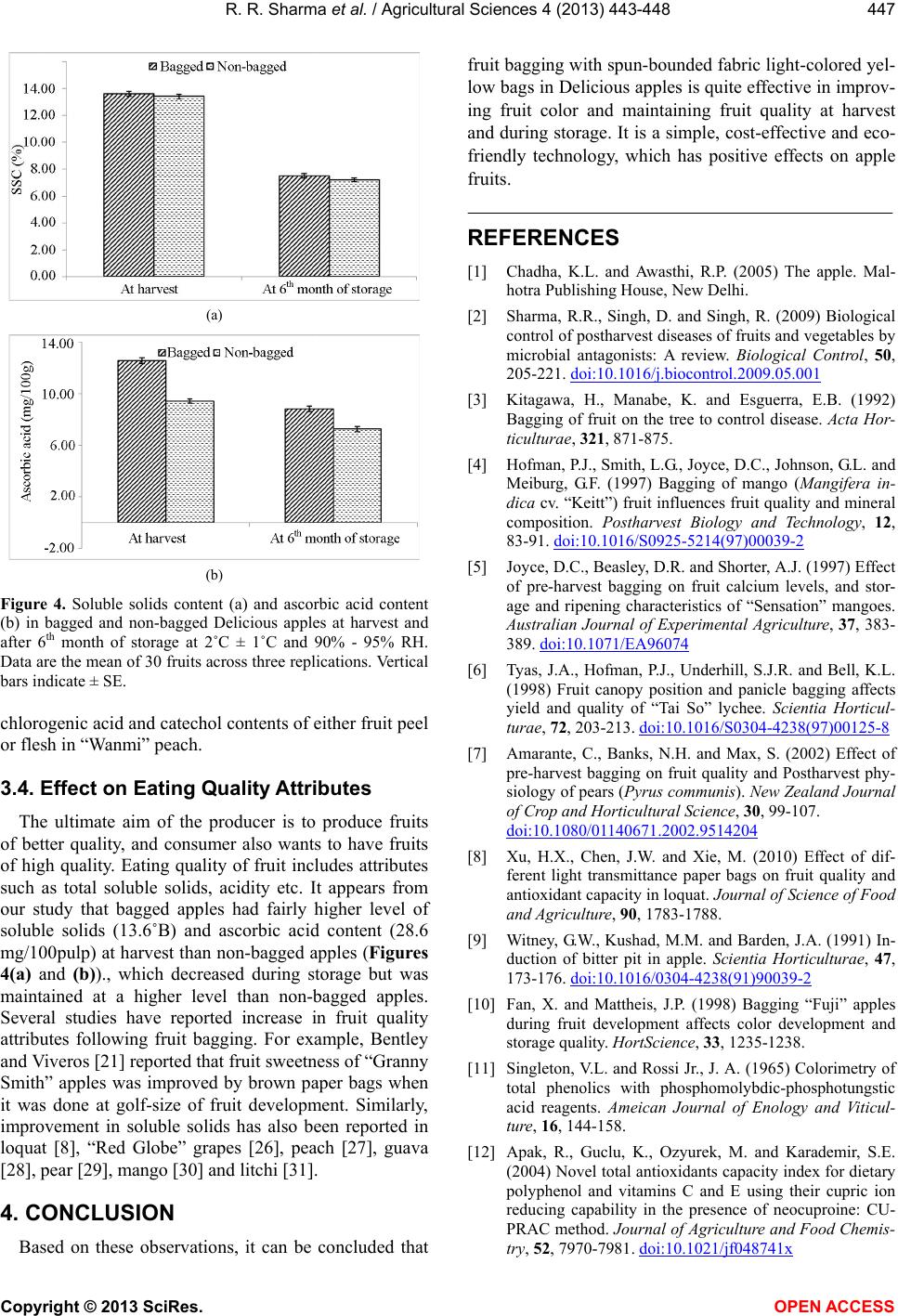

|