Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

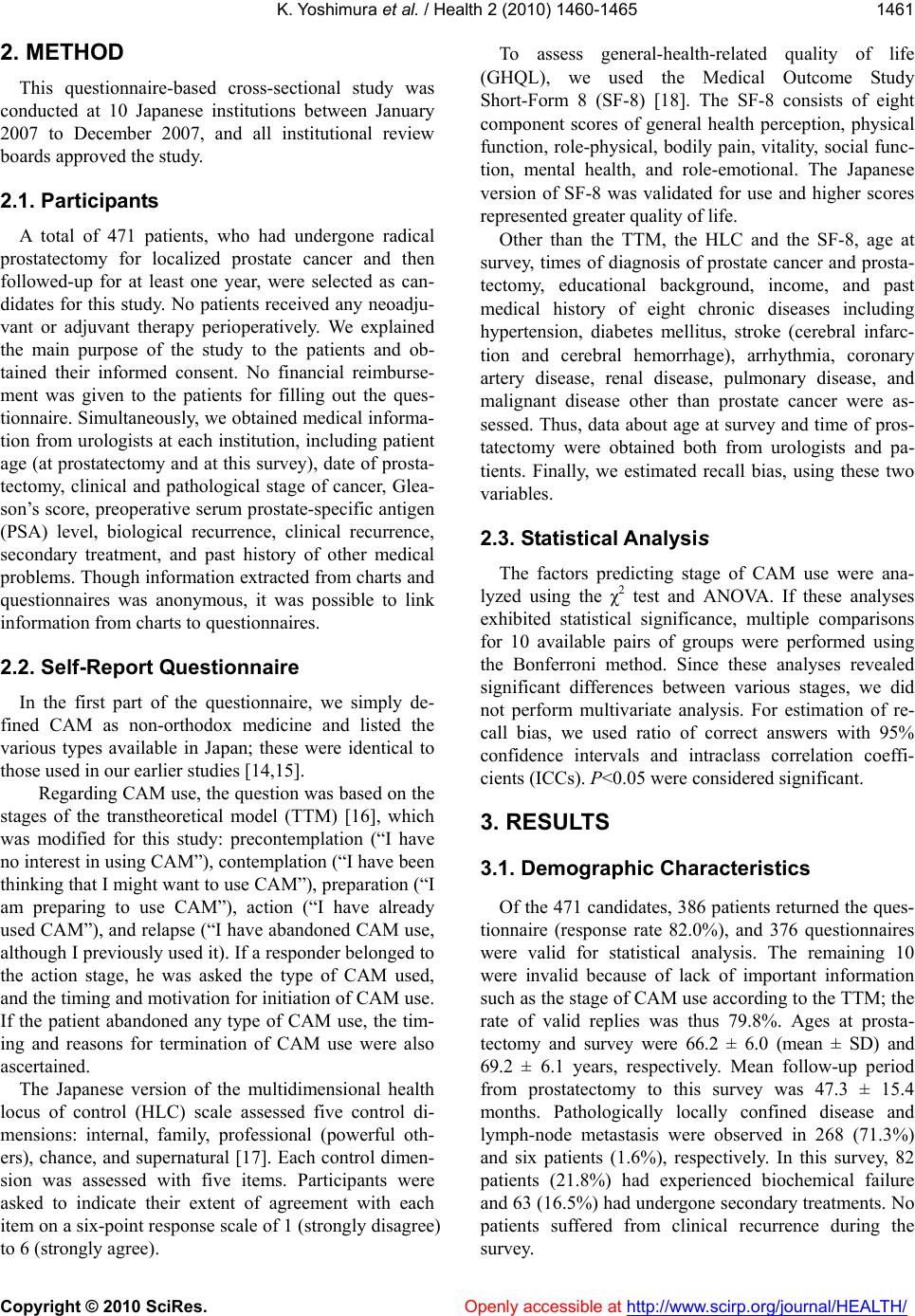

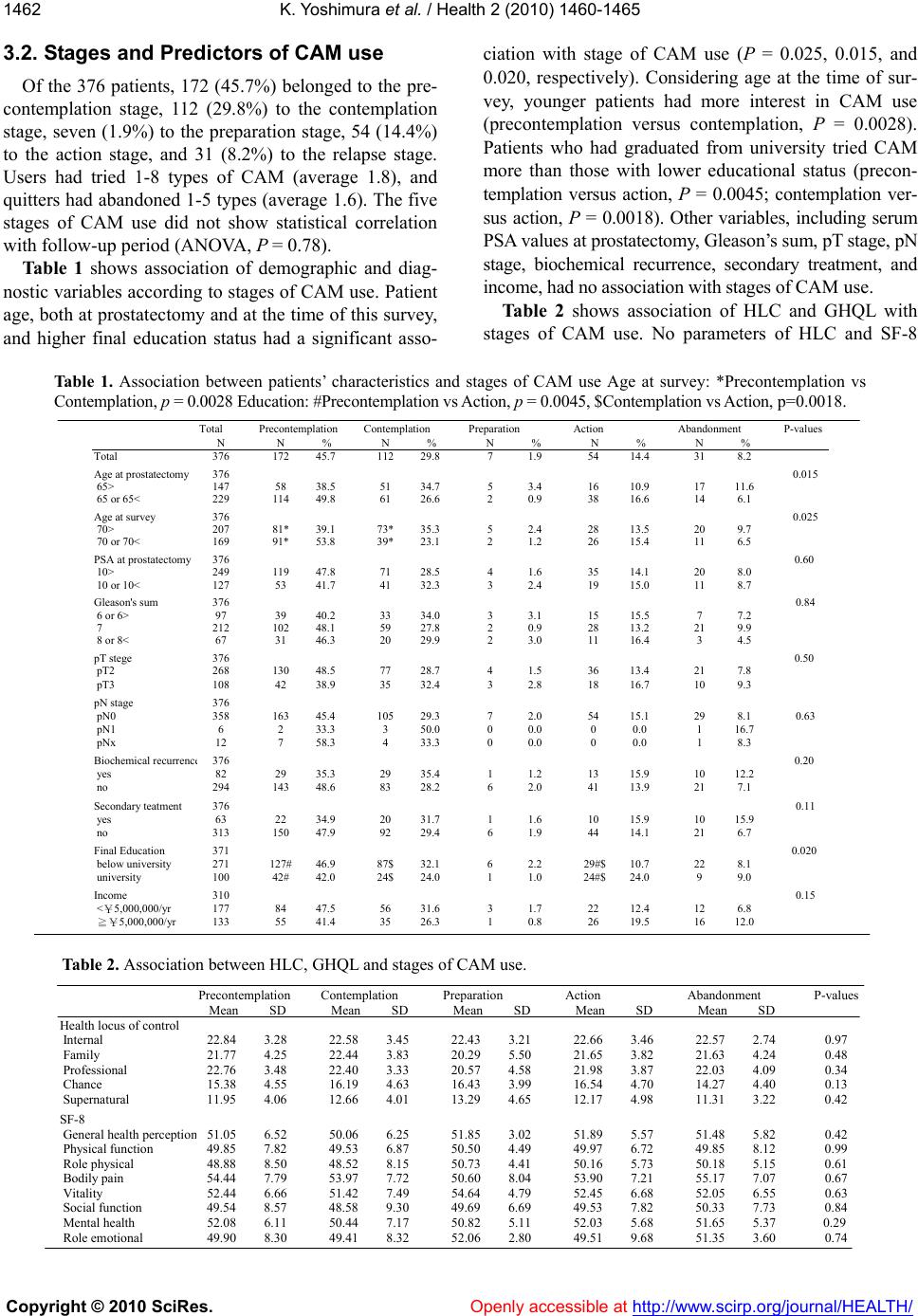

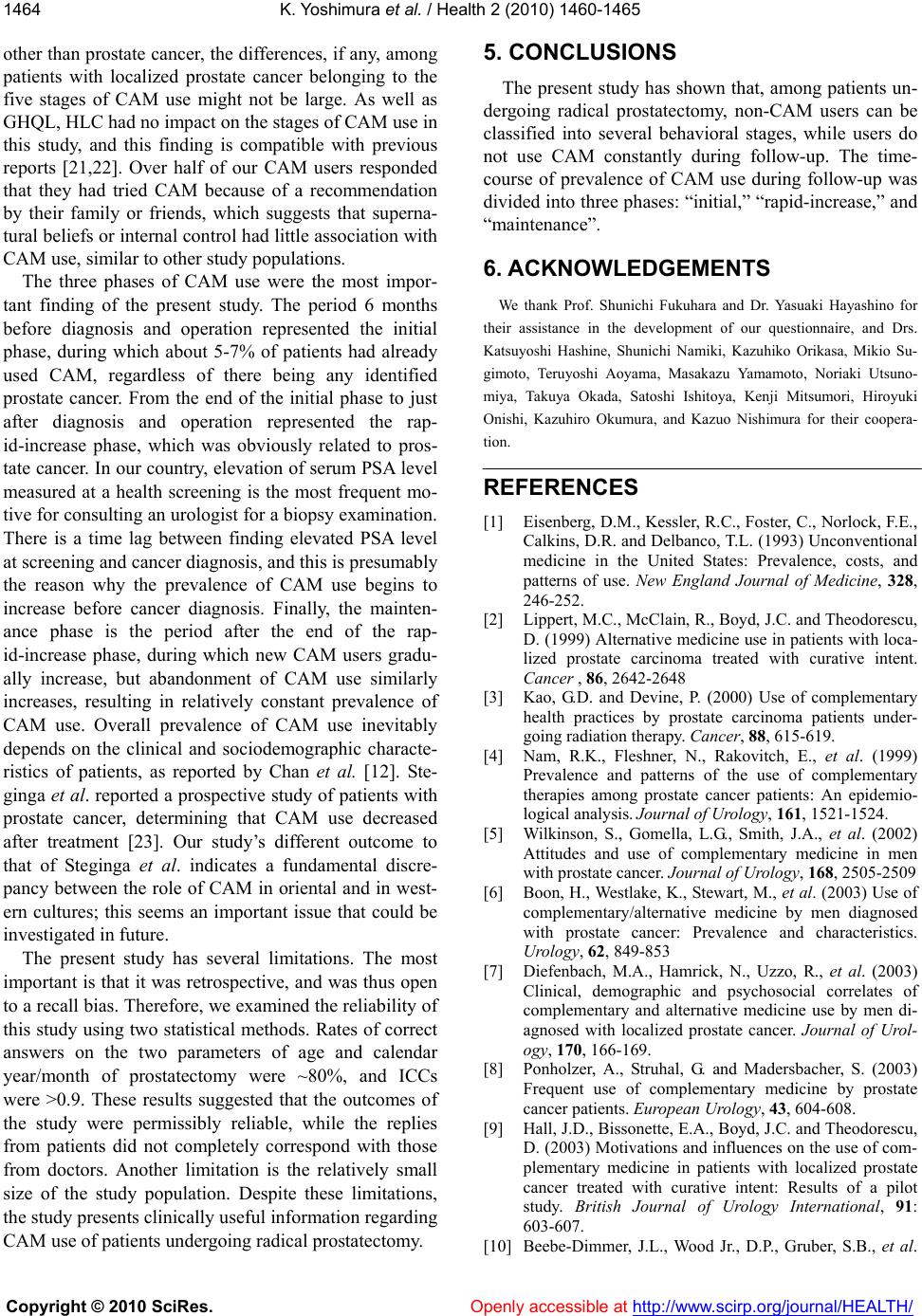

Vol.2, No.12, 1460-1465 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.212217 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Transition behavior in the use of complementary and alternative medicine during follow-up after radical prostatectomy: a multicente r su rv ey i n Ja pan Koji Yoshimura1*, Yoshiteru Sumiyoshi2, Toshiyuki Kamoto1, Osamu Ogawa1, Yoichi Arai3, Yoshiyuki Kakehi4, Akito Terai5, Hiroshi Kanamaru6, Mutsushi Kawakita7, Naoko Kinukawa8 1Department of Urology, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan; *Corresponding Author: ky7527@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp; 2Department of Urology, Shikoku Cancer Center, Matsuyama, Japan; 3Department of Urology, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan; 4Department of Urology, Kagawa University of Medicine, Takamatsu, Japan; 5Department of Urology, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Kurashiki, Japan; 6Department of Urology, Kitano Hospital, Ohgimachi, Japan; 7Department of Urology, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Kobe, Japan; 8Department of Medical Information Science, Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan. Received 25 August 2010; revised 12 October 2010; accepted 29 October 2010 ABSTRACT Objectives: We evaluated the prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), as well as the transitional nature of its use, before and after radical prostatectomy in Japa- nese patients with localized prostate cancer. Methods: We enrolled 376 patients, who ans- wered a self-administered questionnaire on CAM use, psychological health locus of control (HLC), and general-health-related quality of life (GHQL). Detailed information regarding CAM use according to the transtheoretical model, and the time at initiation and abandonment of CAM use were assessed. Medical information was also extracted from patient charts. Results: 45.7% of patients belonged to the “precontemplation” stage, 29.8% to the “contemplation” stage, 1.9% to the “preparation” stage, 14.4% to the “action” st age, and 8.2% to the “relapse” stage. Although patient age and educational status had a signif- icant impact on stage of CAM use, HLC and GHQL were not associated with them. The time-course of prevalence of CAM use during follow-up was divided into three phases: “ini- tial,” “rapid-increase,” and “maintenance”. Con- clusions: Among patients undergoing radical prostatectomy, non-users can be classified into several behavioral stages, while users do not use CAM constantly during follow-up. Keywords: Prostate Cancer; Alternative Medicine; Health Survey; Health Locus of Control; Epidemiology 1. INTRODUCTION Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has gradually gained in popularity worldwide since the study of Eisenberg et al. in 1993 [1]. In urology, many studies have been conducted to elucidate the prevalence and associated background of CAM use in patients with prostate cancer [2-14]. Most of these have been cross- sectional studies, and the question about CAM use was all-or-nothing, i.e., yes or no. However, patients with cancer initiate CAM use at various times during fol- low-up involving conventional treatments. They also occasionally abandon CAM for various reasons. Non- CAM users can be divided into several behavioral stages according to their degree of interest in CAM use. We conducted a multicenter cross-sectional survey to explore the detailed behavioral stages for CAM use in patients with localized prostate cancer undergoing radi- cal prostatectomy. We focused our study on patients who had undergone radical prostatectomy without any peri- operative treatment, which ensured the homogeneity of the population. First, we explored the behavioral transi- tion involved with CAM use hoping to better understand the background associated with this. Second, we inves- tigated the timing of the initiation and termination of CAM use in patients in the action/maintenance or re- lapse stages. Finally, we estimated the reliability of the study outcomes, namely, the recall bias suffered in this retrospective study.  K. Yoshimura et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1460-14 65 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1461 2. METHOD This questionnaire-based cross-sectional study was conducted at 10 Japanese institutions between January 2007 to December 2007, and all institutional review boards approved the study. 2.1. Participants A total of 471 patients, who had undergone radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer and then followed-up for at least one year, were selected as can- didates for this study. No patients received any neoadju- vant or adjuvant therapy perioperatively. We explained the main purpose of the study to the patients and ob- tained their informed consent. No financial reimburse- ment was given to the patients for filling out the ques- tionnaire. Simultaneously, we obtained medical informa- tion from urologists at each institution, including patient age (at prostatectomy and at this survey), date of prosta- tectomy, clinical and pathological stage of cancer, Glea- son’s score, preoperative serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, biological recurrence, clinical recurrence, secondary treatment, and past history of other medical problems. Though information extracted from charts and questionnaires was anonymous, it was possible to link information from charts to questionnaires. 2.2. Self-Report Questionnaire In the first part of the questionnaire, we simply de- fined CAM as non-orthodox medicine and listed the various types available in Japan; these were identical to those used in our earlier studies [14,15]. Regarding CAM use, the question was based on the stages of the transtheoretical model (TTM) [16], which was modified for this study: precontemplation (“I have no interest in using CAM”), contemplation (“I have been thinking that I might want to use CAM”), preparation (“I am preparing to use CAM”), action (“I have already used CAM”), and relapse (“I have abandoned CAM use, although I previously used it). If a responder belonged to the action stage, he was asked the type of CAM used, and the timing and motivation for initiation of CAM use. If the patient abandoned any type of CAM use, the tim- ing and reasons for termination of CAM use were also ascertained. The Japanese version of the multidimensional health locus of control (HLC) scale assessed five control di- mensions: internal, family, professional (powerful oth- ers), chance, and supernatural [17]. Each control dimen- sion was assessed with five items. Participants were asked to indicate their extent of agreement with each item on a six-point response scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). To assess general-health-related quality of life (GHQL), we used the Medical Outcome Study Short-Form 8 (SF-8) [18]. The SF-8 consists of eight component scores of general health perception, physical function, role-physical, bodily pain, vitality, social func- tion, mental health, and role-emotional. The Japanese version of SF-8 was validated for use and higher scores represented greater quality of life. Other than the TTM, the HLC and the SF-8, age at survey, times of diagnosis of prostate cancer and prosta- tectomy, educational background, income, and past medical history of eight chronic diseases including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke (cerebral infarc- tion and cerebral hemorrhage), arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, renal disease, pulmonary disease, and malignant disease other than prostate cancer were as- sessed. Thus, data about age at survey and time of pros- tatectomy were obtained both from urologists and pa- tients. Finally, we estimated recall bias, using these two variables. 2.3. Statistical Analysis The factors predicting stage of CAM use were ana- lyzed using the χ2 test and ANOVA. If these analyses exhibited statistical significance, multiple comparisons for 10 available pairs of groups were performed using the Bonferroni method. Since these analyses revealed significant differences between various stages, we did not perform multivariate analysis. For estimation of re- call bias, we used ratio of correct answers with 95% confidence intervals and intraclass correlation coeffi- cients (ICCs). P<0.05 were considered significant. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographic Characteristics Of the 471 candidates, 386 patients returned the ques- tionnaire (response rate 82.0%), and 376 questionnaires were valid for statistical analysis. The remaining 10 were invalid because of lack of important information such as the stage of CAM use according to the TTM; the rate of valid replies was thus 79.8%. Ages at prosta- tectomy and survey were 66.2 ± 6.0 (mean ± SD) and 69.2 ± 6.1 years, respectively. Mean follow-up period from prostatectomy to this survey was 47.3 ± 15.4 months. Pathologically locally confined disease and lymph-node metastasis were observed in 268 (71.3%) and six patients (1.6%), respectively. In this survey, 82 patients (21.8%) had experienced biochemical failure and 63 (16.5%) had undergone secondary treatments. No patients suffered from clinical recurrence during the survey.  K. Yoshimura et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1460-14 65 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1462 3.2. Stages and Predictors of CAM use Of the 376 patients, 172 (45.7%) belonged to the pre- contemplation stage, 112 (29.8%) to the contemplation stage, seven (1.9%) to the preparation stage, 54 (14.4%) to the action stage, and 31 (8.2%) to the relapse stage. Users had tried 1-8 types of CAM (average 1.8), and quitters had abandoned 1-5 types (average 1.6). The five stages of CAM use did not show statistical correlation with follow-up period (ANOVA, P = 0.78). Ta bl e 1 shows association of demographic and diag- nostic variables according to stages of CAM use. Patient age, both at prostatectomy and at the time of this survey, and higher final education status had a significant asso- ciation with stage of CAM use (P = 0.025, 0.015, and 0.020, respectively). Considering age at the time of sur- vey, younger patients had more interest in CAM use (precontemplation versus contemplation, P = 0.0028). Patients who had graduated from university tried CAM more than those with lower educational status (precon- templation versus action, P = 0.0045; contemplation ver- sus action, P = 0.0018). Other variables, including serum PSA values at prostatectomy, Gleason’s sum, pT stage, pN stage, biochemical recurrence, secondary treatment, and income, had no association with stages of CAM use. Table 2 shows association of HLC and GHQL with stages of CAM use. No parameters of HLC and SF-8 Table 1. Association between patients’ characteristics and stages of CAM use Age at survey: *Precontemplation vs Contemplation, p = 0.0028 Education: #Precontemplation vs Action, p = 0.0045, $Contemplation vs Action, p=0.0018. TotalPrecontemplation ContemplationPreparationActionAbandonmentP-values N N%N%N%N%N% Total376172 45.711229.871.95414.4318.2 Age at prostatectomy3760.015 65>1475838.55134.753.41610.91711.6 65 or 65<22911449.86126.620.93816.6146.1 A g e at surve y 376 0.025 70>20781*39.173*35.352.42813.5209.7 70 or 70<16991*53.839*23.121.22615.4116.5 PSA at prostatectomy3760.60 10>24911947.87128.541.63514.1208.0 10 or 10<1275341.74132.332.41915.0118.7 Gleason's sum3760.84 6 or 6>973940.23334.033.11515.577.2 721210248.15927.820.92813.2219.9 8 or 8<673146.32029.923.01116.434.5 pT stege3760.50 pT226813048.57728.741.53613.4217.8 pT31084238.93532.432.81816.7109.3 pN stage376 pN035816345.410529.372.05415.1298.10.63 pN16233.3350.000.000.0116.7 pNx12758.3433.300.000.018.3 Biochemical recurrenc e 376 0.20 yes822935.32935.411.21315.91012.2 no29414348.68328.262.04113.9217.1 Secondary teatment3760.11 yes632234.92031.711.61015.91015.9 no31315047.99229.461.94414.1216.7 Final Education3710.020 below university271127#46.987$32.162.229#$10.7228.1 university10042#42.024$24.011.024#$24.099.0 Income 3100.15 <¥5,000,000/ yr 1778447.5 5631.631.72212.4 126.8 ≧¥5,000,000/ y r13355 41.435 26.310.82619.516 12.0 Table 2. Association between HLC, GHQL and stages of CAM use. Precontemplation ContemplationPreparationActionAbandonmentP-values Mean SDMean SDMean SDMean SDMean SD Health locus of control Internal22.843.2822.583.4522.433.2122.663.4622.572.740.97 Family21.774.2522.443.8320.295.5021.653.8221.634.240.48 Professional22.763.4822.403.3320.574.5821.983.8722.034.090.34 Chance15.384.5516.194.6316.433.9916.544.7014.274.400.13 Supernatural11.954.0612.664.0113.294.6512.174.9811.313.220.42 SF-8 General health p erce p tio n 51.05 6.5250.06 6.2551.85 3.0251.89 5.5751.48 5.820.42 Physical function49.857.8249.536.8750.504.4949.976.7249.858.120.99 Role physical48.888.5048.528.1550.734.4150.165.7350.185.150.61 Bodily pain54.447.7953.977.7250.608.0453.907.2155.177.070.67 Vitality52.446.6651.427.4954.644.7952.456.6852.056.550.63 Social function49.548.5748.589.3049.696.6949.537.8250.337.730.84 Mental health52.086.1150.447.1750.825.1152.035.6851.655.370.29 Role emotional49.908.3049.418.3252.062.8049.519.6851.353.600.74  K. Yoshimura et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1460-14 65 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1463 had a significant association with stages of CAM use. 3.3. Initiation and Termination of CAM use Figure 1 depicts transition of CAM use in all study patients, based on diagnosis of prostate cancer and pros- tatectomy. Approximately 5% of patients had used some form of CAM, regardless of cancer diagnosis or surgery. From 6 months before diagnosis or a year before prosta- tectomy, the rate of CAM use rapidly increased; though some patients abandoned CAM during these periods. From a year after diagnosis or 6 months after prosta- tectomy, the number of new CAM users gradually in- creased, but nearly the same number of patients aban- doned CAM use. Thus, the overall prevalence of CAM use appeared steady during this period. Although 85 (22.6%) of the 376 patients tried CAM during the fol- low-up period, the highest prevalence of CAM use was observed at 29-30 months after diagnosis (17.5%) and 24-25 months after prostatectomy (16.9%). The most common reason for the initiation of CAM was “recommendation by family or friends” (75 res- ponses, 52.9%), followed by “research by themselves” (21.4%), “information by chance” (15.0%), and others (10.0%). The most prevalent reason for abandonment of CAM use was “expense” (15 responses, 29.4%), fol- lowed by “lack of expected efficacy” (23.5%), “lack of interest” (13.7%), and others (33.3%). No patient gave “adverse effects” as a reason for abandonment. Figure 1. Transition of CAM use among all patients, based on cancer diagnosis and prostatectomy. Asterisks indicate the timings of the highest percentage of CAM users. ● accumu- lated rate of initiation of CAM use; ◆ prevalence of CAM use by month; ▲ accumulated rate of termination of CAM use. 3.4. Estimation of Recall Bias Regarding age at time of survey, the difference be- tween that obtained from charts and that from question- naires was a mean 0.195 years. In the questionnaires, 19 patients gave a younger age and 72 an older one than their actual age, while 285 patients (75.8%: 95% confi- dence interval, 71.2-79.8%) gave an accurate age. ICC was 0.940. Regarding date of prostatectomy (calendar year and month), the mean difference between that ob- tained from charts and that from questionnaire was 0.186 months. Three hundred and thirteen patients (83.2%: 95% confidence interval, 79.1-86.7%) gave accurate date. Based on the period from prostatectomy to this survey, ICC was 0.919. 4. DISCUSSION Generally, 18-43% of prostate cancer patients are re- ported to be using some type of CAM [2-14,19]. In the current study, which focused on patients undergoing radical prostatectomy, 22.6% of patients had experience of some type of CAM during the follow-up period; this observation was compatible with previous studies in our country [14,19]. This study also revealed that these pa- tients did not use CAM consistently throughout the fol- low-up period, and about one-third of users had already abandoned some type of CAM at the time of this survey. As well as CAM users, non-CAM users could be classi- fied into several behavioral stages. Namely, half of pa- tients had no interest in CAM (precontemplation stage), and ~30% of patients had been interested in CAM use but did not actually use it (contemplation and prepara- tion stages). These percentages were considerably dif- ferent from those recently reported by Hirai et al. [20], which suggested that patients with non-metastatic pros- tate cancer treated radically were less interested in CAM than those with other active cancers, as we have reported previously [14]. While several predictors of CAM use among prostate cancer patients have been reported so far [2-5,14], in- cluding younger age, no recurrence after prostatectomy, higher income, and higher education, our study pre- sented more detailed information. Patient age had an impact on transition from precontemplation to contem- plation, with higher aged patients tending to have no interest in CAM. On the other hand, educational status had an impact on actual CAM use. Although several previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between CAM use and GHQL in prostate cancer patients [8,14], one study exhibited no such cor- relation [7]. While many studies, since that of Cassileth [21], have reported that GHQL has a significant associa- tion with CAM use in patients with malignant disease  K. Yoshimura et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1460-14 65 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1464 other than prostate cancer, the differences, if any, among patients with localized prostate cancer belonging to the five stages of CAM use might not be large. As well as GHQL, HLC had no impact on the stages of CAM use in this study, and this finding is compatible with previous reports [21,22]. Over half of our CAM users responded that they had tried CAM because of a recommendation by their family or friends, which suggests that superna- tural beliefs or internal control had little association with CAM use, similar to other study populations. The three phases of CAM use were the most impor- tant finding of the present study. The period 6 months before diagnosis and operation represented the initial phase, during which about 5-7% of patients had already used CAM, regardless of there being any identified prostate cancer. From the end of the initial phase to just after diagnosis and operation represented the rap- id-increase phase, which was obviously related to pros- tate cancer. In our country, elevation of serum PSA level measured at a health screening is the most frequent mo- tive for consulting an urologist for a biopsy examination. There is a time lag between finding elevated PSA level at screening and cancer diagnosis, and this is presumably the reason why the prevalence of CAM use begins to increase before cancer diagnosis. Finally, the mainten- ance phase is the period after the end of the rap- id-increase phase, during which new CAM users gradu- ally increase, but abandonment of CAM use similarly increases, resulting in relatively constant prevalence of CAM use. Overall prevalence of CAM use inevitably depends on the clinical and sociodemographic characte- ristics of patients, as reported by Chan et al. [12]. Ste- ginga et al. reported a prospective study of patients with prostate cancer, determining that CAM use decreased after treatment [23]. Our study’s different outcome to that of Steginga et al. indicates a fundamental discre- pancy between the role of CAM in oriental and in west- ern cultures; this seems an important issue that could be investigated in future. The present study has several limitations. The most important is that it was retrospective, and was thus open to a recall bias. Therefore, we examined the reliability of this study using two statistical methods. Rates of correct answers on the two parameters of age and calendar year/month of prostatectomy were ~80%, and ICCs were >0.9. These results suggested that the outcomes of the study were permissibly reliable, while the replies from patients did not completely correspond with those from doctors. Another limitation is the relatively small size of the study population. Despite these limitations, the study presents clinically useful information regarding CAM use of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. 5. CONCLUSIONS The present study has shown that, among patients un- dergoing radical prostatectomy, non-CAM users can be classified into several behavioral stages, while users do not use CAM constantly during follow-up. The time- course of prevalence of CAM use during follow-up was divided into three phases: “initial,” “rapid-increase,” and “maintenance”. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Prof. Shunichi Fukuhara and Dr. Yasuaki Hayashino for their assistance in the development of our questionnaire, and Drs. Katsuyoshi Hashine, Shunichi Namiki, Kazuhiko Orikasa, Mikio Su- gimoto, Teruyoshi Aoyama, Masakazu Yamamoto, Noriaki Utsuno- miya, Takuya Okada, Satoshi Ishitoya, Kenji Mitsumori, Hiroyuki Onishi, Kazuhiro Okumura, and Kazuo Nishimura for their coopera- tion. REFERENCES [1] Eisenberg, D.M., Kessler, R.C., Foster, C., Norlock, F.E., Calkins, D.R. and Delbanco, T.L. (1993) Unconventional medicine in the United States: Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. New England Journal of Medicine, 328, 246-252. [2] Lippert, M.C., McClain, R., Boyd, J.C. and Theodorescu, D. (1999) Alternative medicine use in patients with loca- lized prostate carcinoma treated with curative intent. Cancer , 86, 2642-2648 [3] Kao, G.D. and Devine, P. (2000) Use of complementary health practices by prostate carcinoma patients under- going radiation therapy. Cancer, 88, 615-619. [4] Nam, R.K., Fleshner, N., Rakovitch, E., et al. (1999) Prevalence and patterns of the use of complementary therapies among prostate cancer patients: An epidemio- logical analysis. Journal of Urology, 161, 1521-1524. [5] Wilkinson, S., Gomella, L.G., Smith, J.A., et al. (2002) Attitudes and use of complementary medicine in men with prostate cancer. Journal of Urology, 168, 2505-2509 [6] Boon, H., Westlake, K., Stewart, M., et al. (2003) Use of complementary/alternative medicine by men diagnosed with prostate cancer: Prevalence and characteristics. Urology, 62, 849-853 [7] Diefenbach, M.A., Hamrick, N., Uzzo, R., et al. (2003) Clinical, demographic and psychosocial correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use by men di- agnosed with localized prostate cancer. Journal of Urol- ogy, 170, 166-169. [8] Ponholzer, A., Struhal, G. and Madersbacher, S. (2003) Frequent use of complementary medicine by prostate cancer patients. European Urology, 43, 604-608. [9] Hall, J.D., Bissonette, E.A., Boyd, J.C. and Theodorescu, D. (2003) Motivations and influences on the use of com- plementary medicine in patients with localized prostate cancer treated with curative intent: Results of a pilot study. British Journal of Urology International, 91: 603-607. [10] Beebe-Dimmer, J.L., Wood Jr., D.P., Gruber, S.B., et al.  K. Yoshimura et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1460-14 65 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1465 (2004) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in men with family history of prostate cancer: A pilot study. Urology, 63, 282-287. [11] Eng, J., Ramsum, D., Verfoef, M., Guns, E., Davison, J, and Gallagher, R. (2003) A population-based survey of complementary and alternative medicine use in men re- cently diagnosed with prostate cancer. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 2, 212-216. [12] Chan, J.M., Elkin, E.P., Silva, S.J., Broering, J.M., Latini, D.M. and Carroll, P.R. (2005) Total and specific com- plementary and alternative medicine use in a large cohort of men with prostate cancer. Urology, 66, 1223-1228. [13] Jones, R.A., Taylor, A.G., Bourguignon C., et al. (2007) Complementary and alternative medicine modality use and beliefs among African American prostate cancer sur- vivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34, 359-364 [14] Yoshimura, K., Ichioka, K., Terada, N., Terai, A. and Arai, Y. (2003) Use of complementary and alternative medi- cine by patients with localized prostate carcinoma: study at a single institute in Japan. International Journal of Clinical Oncology, 8, 26-30. [15] Yoshimura, K., Ueda, N., Ichioka, K., Matsui, Y., Terai, A. and Arai, Y. (2005) Use of complementary and alter- native medicine by patients with urologic cancer: A prospective study at a single Japanese institution. Sup- port Care Cancer , 13, 685-690 [16] Prochaska, J.O. and DiClemente, C.C. (1983) Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integral model of change. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psy- chology, 51, 390-395. [17] Horige, Y. (1991) Development of Japanese version of health locus of control. Kenkoshinrigakukenkyu, 4, 1-7 (in Japanese). [18] Fukuhara, S. and Suzukamo, Y. (2004) Manual of the SF-8 Japanese version. Institute for Health Outcomes & Process Evaluation Research, Kyoto. [19] Sumiyoshi, Y., Hashine, K., Koizumi, T., Azuma, K. and Hyodo, K. (2003) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in prostate cancer patients. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkaishi, 94, 328 (in Japanese). [20] Hirai, K., Komura, K., Tokoro, A., et al. (2008) Psycho- logical and behavioral mechanisms influencing the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in can- cer patients. Annals of Oncology, 19, 45-55. [21] Cassileth, B.R., Lusk, E.J., Guerry, D., et al. (1991) Sur- vival and quality of life among patients receiving unpro- ven as compared with conventional cancer therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 324, 1180-1185. [22] Boon, H., Westlake, K., Deber, R. and Moineddin, R. (2005) Problem-solving and decision-making preferences: no difference between complementary and alternative medicine users and non-users. Complementary Therapies in Medici ne, 13, 213-216. [23] Steginga, S.K., Occhipinti, S., Gardiner, R.A.F., Yaxley, J. and Heathcote, P. (2004) A prospective study of the use of alternative therapies by men with localized prostate cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 55, 70-77. |