Paper Menu >>

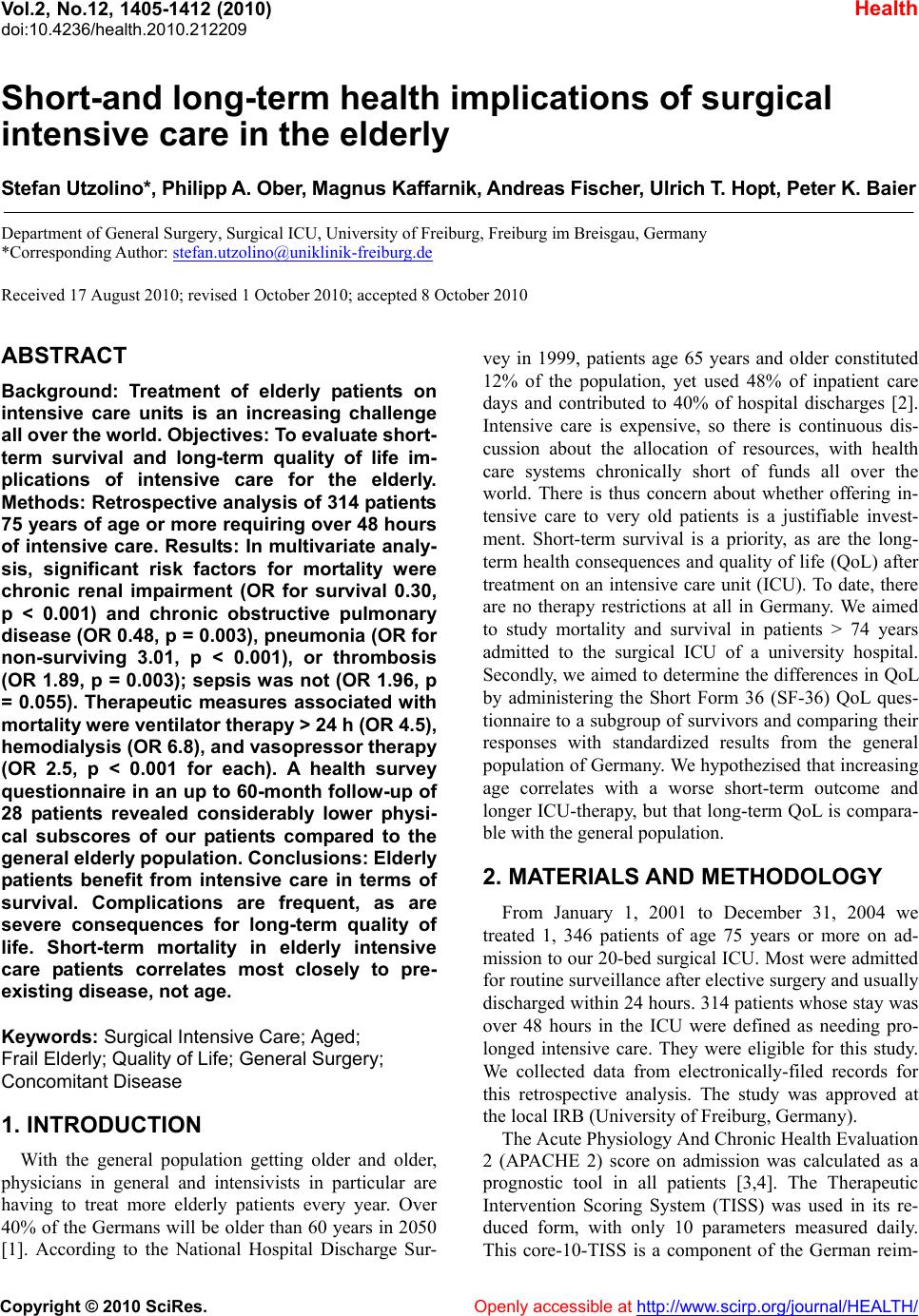

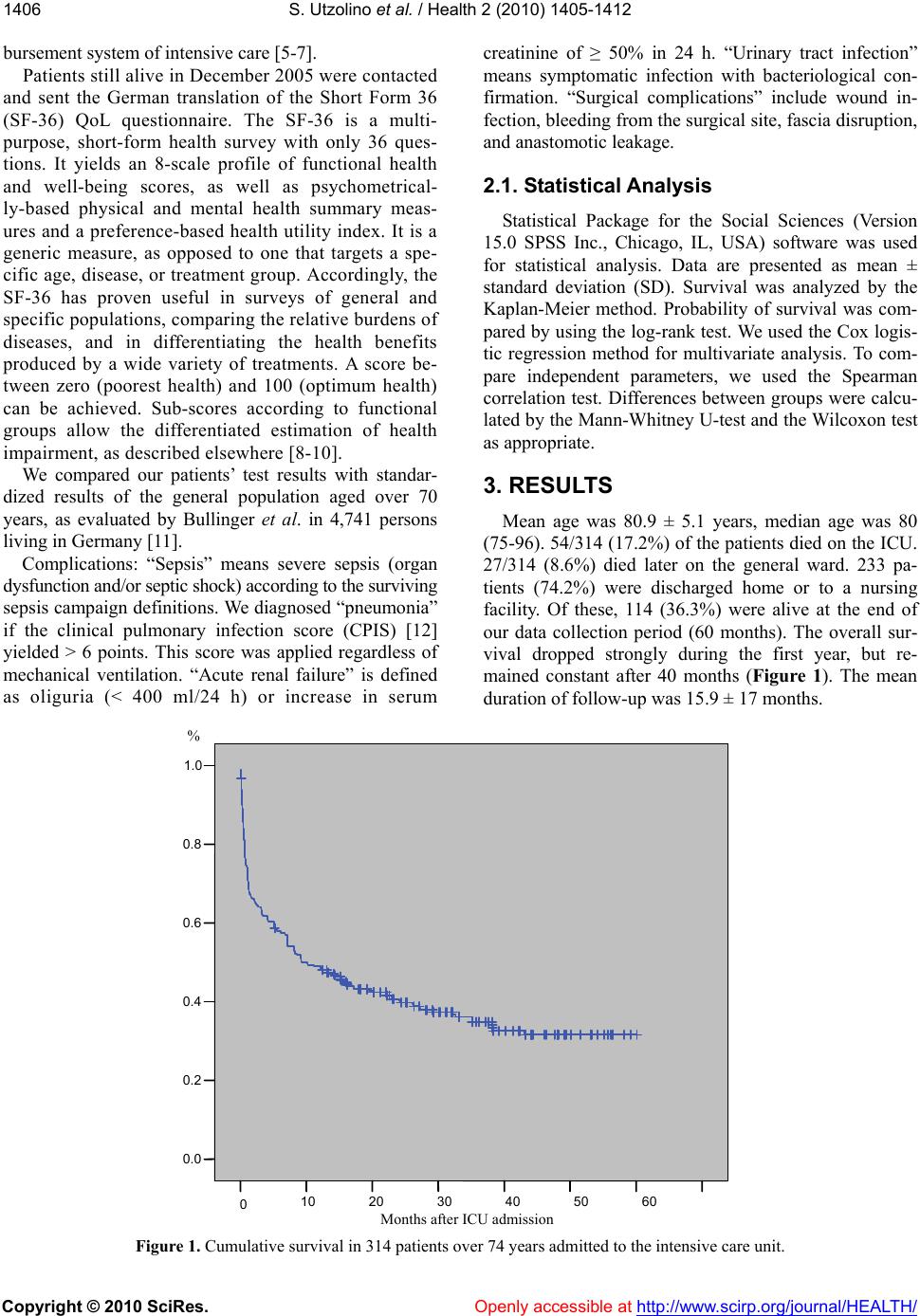

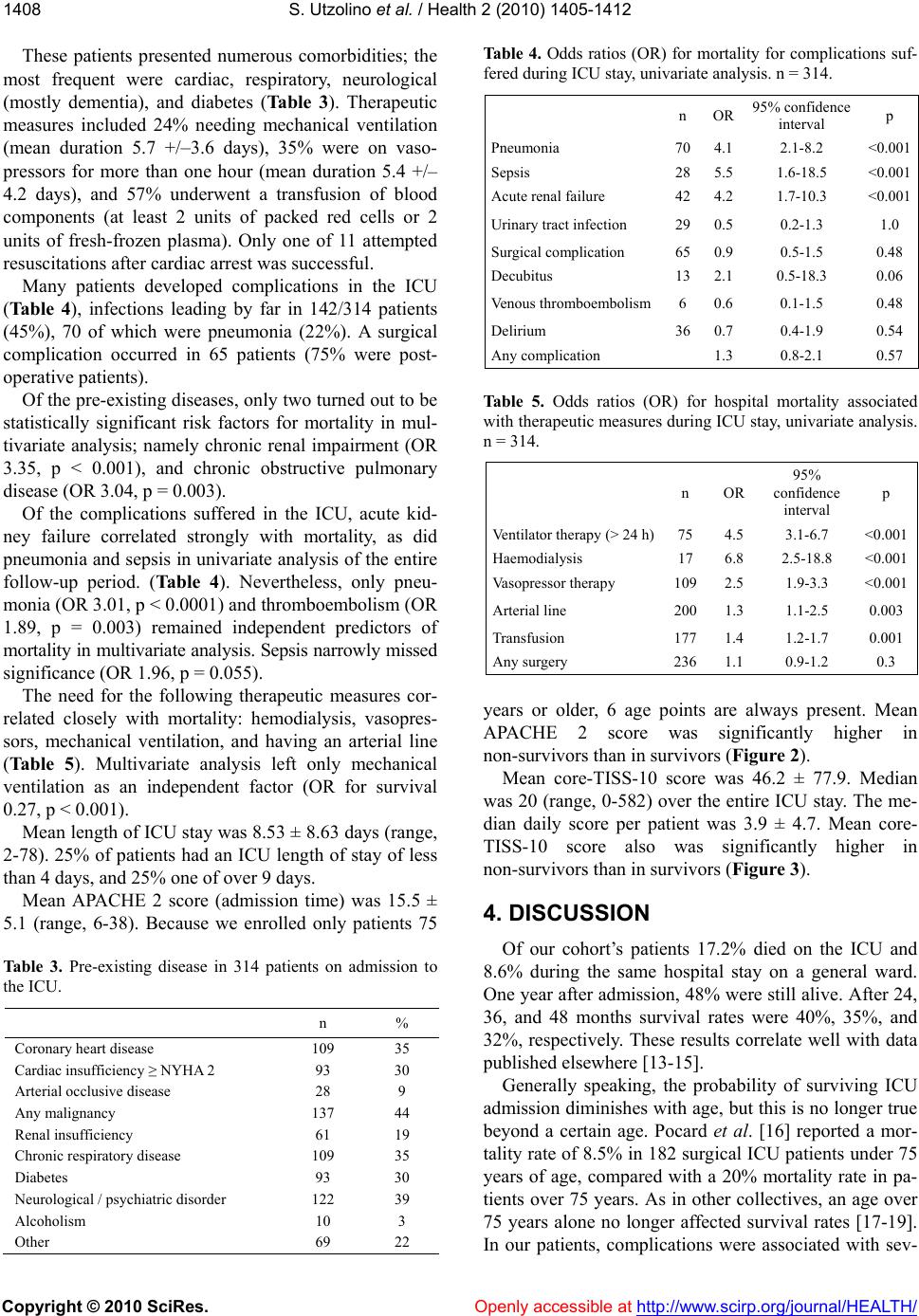

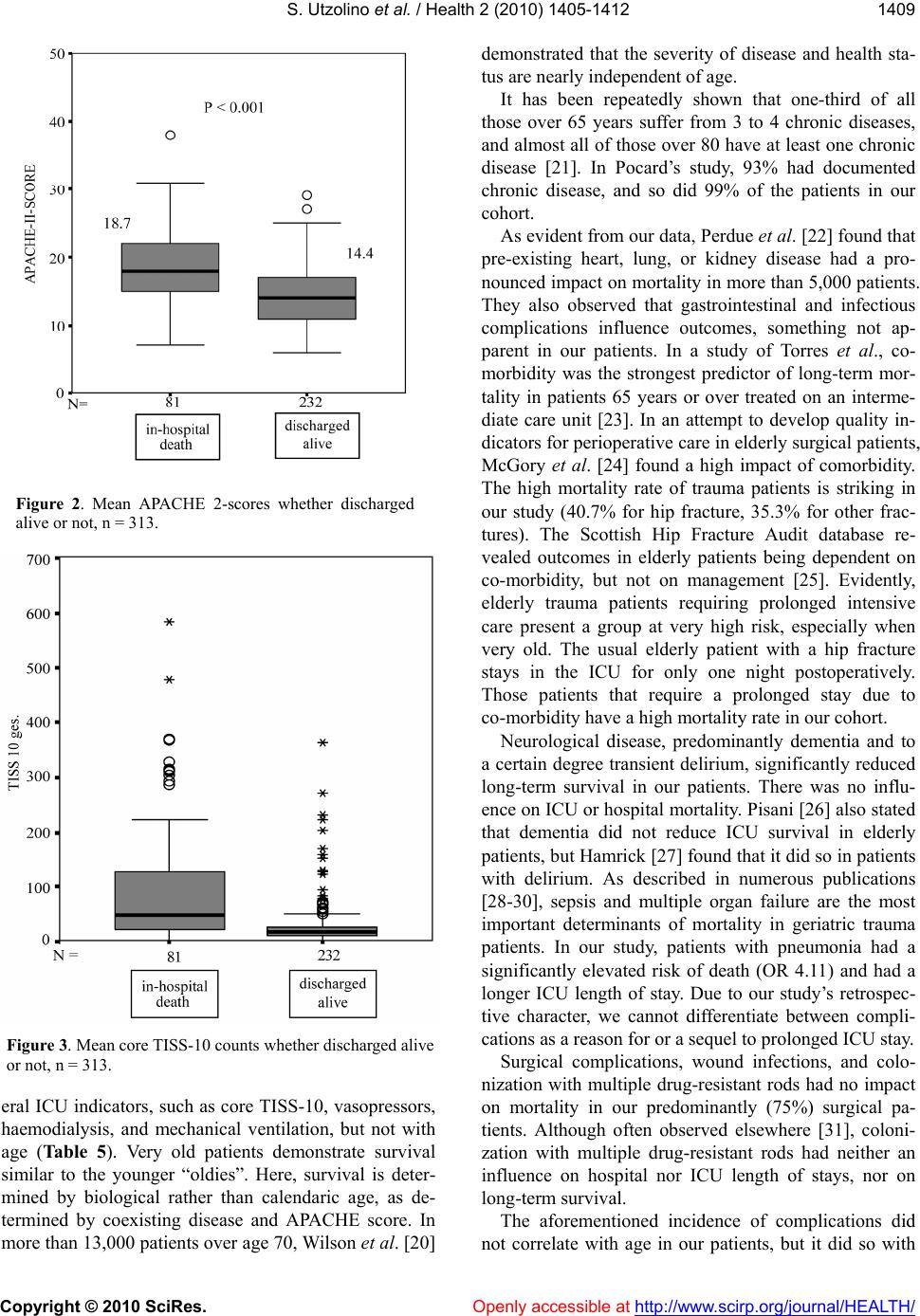

Journal Menu >>

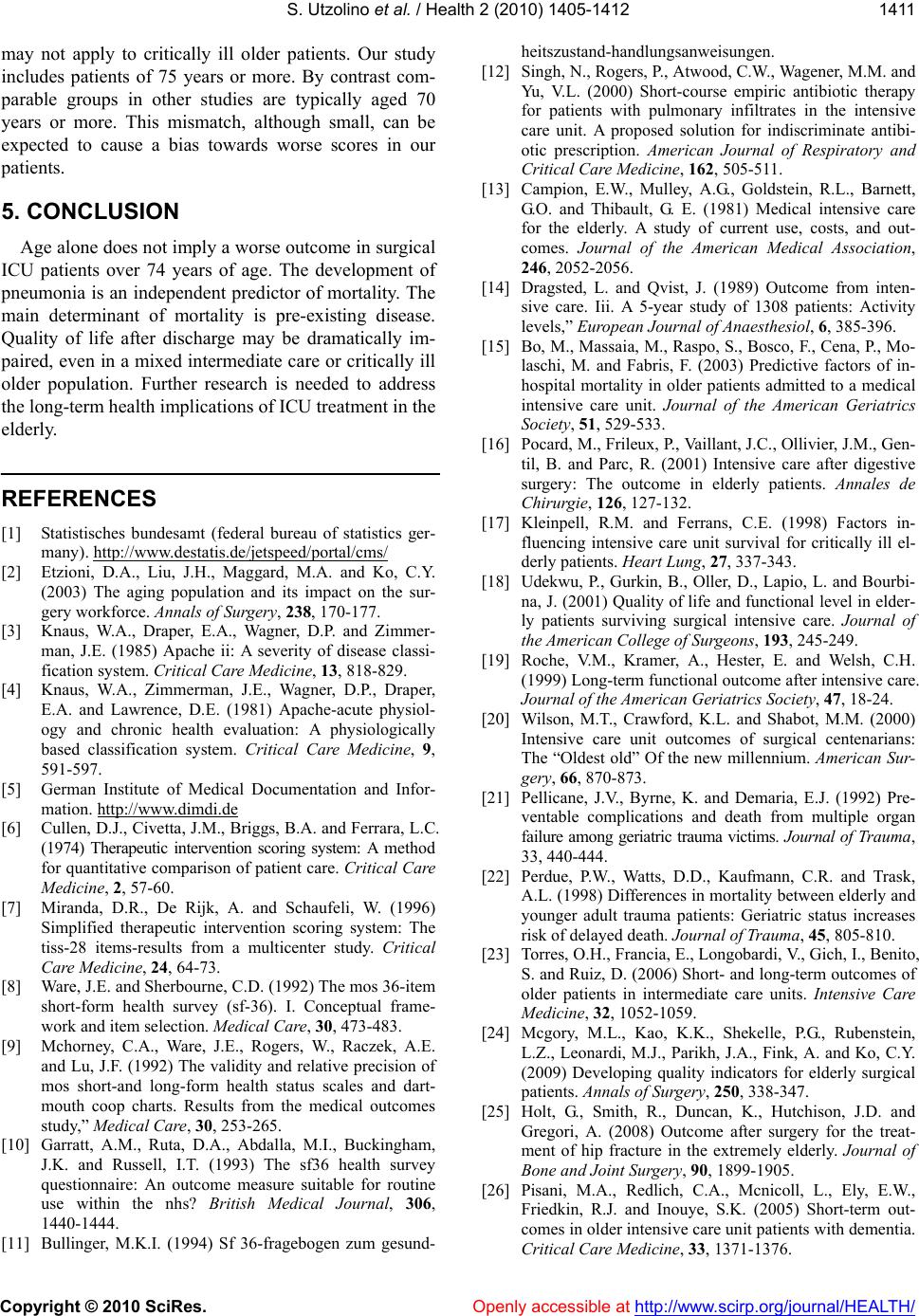

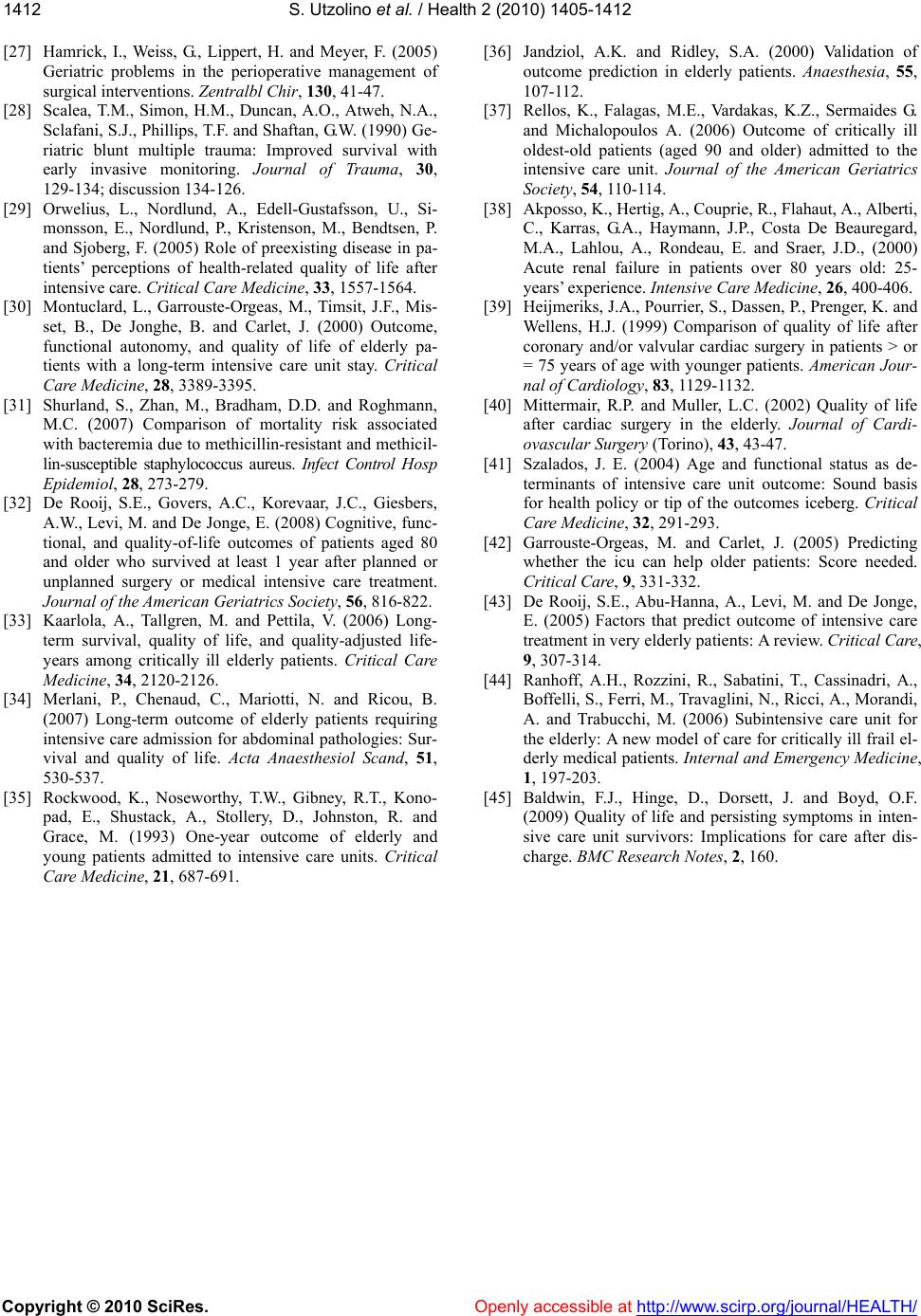

Vol.2, No.12, 1405-1412 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.212209 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Short-and long-term health implications of surgical intensive care in the elderly Stefan Utzolino*, Philipp A. Ober, Magnus Kaffarnik, Andreas Fischer, Ulrich T. Hopt, Peter K. Baier Department of General Surgery, Surgical ICU, University of Freiburg, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany *Corresponding Author: stefan.utzolino@uniklinik-freiburg.de Received 17 August 2010; revised 1 October 2010; accepted 8 October 2010 ABSTRACT Background: Treatment of elderly patients on intensive care units is an increasing challenge all over the world. Objectives: To ev aluate short- term survival and long-term quality of life im- plications of intensive care for the elderly. Methods: Retrospective analysis of 314 patients 75 years of age or more requiring over 48 hours of intensive care. Results: In multivariate analy- sis, significant risk factors for mortality were chronic renal impairment (OR for survival 0.30, p < 0.001) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR 0.48, p = 0.003), pneumonia (OR for non-surviving 3.01, p < 0.001), or thrombosis (OR 1.89, p = 0.003); sepsis was not (OR 1.96, p = 0.055). Therapeutic measures associated with mort ality were ventilator therapy > 24 h (OR 4.5), hemodialysis (O R 6.8), and vasopressor therapy (OR 2.5, p < 0.001 for each). A health survey questionnaire in an up to 60-month follow-up of 28 patients revealed considerably lower physi- cal subscores of our patients compared to the general elderly population. Conclu sions: Elderly patients benefit from intensive care in terms of survival. Complications are frequent, as are severe consequences for long-term quality of life. Short-term mortality in elderly intensive care patients correlates most closely to pre- existing disease, not age. Keywords: Surgical Intensive Care; Aged; Frail Elderly; Quality of Life; General Surgery; Concomitant Disease 1. INTRODUCTION With the general population getting older and older, physicians in general and intensivists in particular are having to treat more elderly patients every year. Over 40% of the Germans will be older than 60 years in 2050 [1]. According to the National Hospital Discharge Sur- vey in 1999, patients age 65 years and older constituted 12% of the population, yet used 48% of inpatient care days and contributed to 40% of hospital discharges [2]. Intensive care is expensive, so there is continuous dis- cussion about the allocation of resources, with health care systems chronically short of funds all over the world. There is thus concern about whether offering in- tensive care to very old patients is a justifiable invest- ment. Short-term survival is a priority, as are the long- term health consequences and quality of life (QoL) after treatment on an intensive care unit (ICU). To date, there are no therapy restrictions at all in Germany. We aimed to study mortality and survival in patients > 74 years admitted to the surgical ICU of a university hospital. Secondly, we aimed to determine the differences in QoL by administering the Short Form 36 (SF-36) QoL ques- tionnaire to a subgroup of survivors and comparing their responses with standardized results from the general population of Germany. We hypothezised that increasing age correlates with a worse short-term outcome and longer ICU-therapy, but that long-term QoL is compara- ble with the general population. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY From January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2004 we treated 1, 346 patients of age 75 years or more on ad- mission to our 20-bed surgical ICU. Most were admitted for routine surveillance after elective surgery and usually discharged within 24 hours. 314 patients whose stay was over 48 hours in the ICU were defined as needing pro- longed intensive care. They were eligible for this study. We collected data from electronically-filed records for this retrospective analysis. The study was approved at the local IRB (University of Freiburg, Germany). The Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation 2 (APACHE 2) score on admission was calculated as a prognostic tool in all patients [3,4]. The Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System (TISS) was used in its re- duced form, with only 10 parameters measured daily. This core-10-TISS is a component of the German reim-  S. Utzolino et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1405-1412 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1406 bursement system of intensive care [5-7]. Patients still alive in December 2005 were contacted and sent the German translation of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) QoL questionnaire. The SF-36 is a multi- purpose, short-form health survey with only 36 ques- tions. It yields an 8-scale profile of functional health and well-being scores, as well as psychometrical- ly-based physical and mental health summary meas- ures and a preference-based health utility index. It is a generic measure, as opposed to one that targets a spe- cific age, disease, or treatment group. Accordingly, the SF-36 has proven useful in surveys of general and specific populations, comparing the relative burdens of diseases, and in differentiating the health benefits produced by a wide variety of treatments. A score be- tween zero (poorest health) and 100 (optimum health) can be achieved. Sub-scores according to functional groups allow the differentiated estimation of health impairment, as described elsewhere [8-10]. We compared our patients’ test results with standar- dized results of the general population aged over 70 years, as evaluated by Bullinger et al. in 4,741 persons living in Germany [11]. Complications: “Sepsis” means severe sepsis (organ dysfunction and/or septic shock) according to the surviving sepsis campaign definitions. We diagnosed “pneumonia” if the clinical pulmonary infection score (CPIS) [12] yielded > 6 points. This score was applied regardless of mechanical ventilation. “Acute renal failure” is defined as oliguria (< 400 ml/24 h) or increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 50% in 24 h. “Urinary tract infection” means symptomatic infection with bacteriological con- firmation. “Surgical complications” include wound in- fection, bleeding from the surgical site, fascia disruption, and anastomotic leakage. 2.1. Statistical Analysis Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Version 15.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Probability of survival was com- pared by using the log-rank test. We used the Cox logis- tic regression method for multivariate analysis. To com- pare independent parameters, we used the Spearman correlation test. Differences between groups were calcu- lated by the Mann-Whitney U-test and the Wilcoxon test as appropriate. 3. RESULTS Mean age was 80.9 ± 5.1 years, median age was 80 (75-96). 54/314 (17.2%) of the patients died on the ICU. 27/314 (8.6%) died later on the general ward. 233 pa- tients (74.2%) were discharged home or to a nursing facility. Of these, 114 (36.3%) were alive at the end of our data collection period (60 months). The overall sur- vival dropped strongly during the first year, but re- mained constant after 40 months (Figure 1). The mean duration of follow-up was 15.9 ± 17 months. Figure 1. Cumulative survival in 314 patients over 74 years admitted to the intensive care unit. 605040302010 0 Months after ICU admission 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 %  S. Utzolino et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1405-1412 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1407 All 114 patients alive in December 2005 could be contacted. They were sent the SF36 QoL questionnaire. We received 73 questionnaires back. In another 9 cases, relatives telephoned, informing us that the former patient could not complete the questionnaire because of demen- tia. 13 returned with no identification, and 32 were in- complete. Thus only 28 forms remained for analysis. The 28 patients eligible for analysis did not differ from the rest of the survivors in any category: not in age, nor in length of hospital stay, ICU length of stay, APACHE 2 score, or core-10-TISS score (p > 0.15 for all parameters). None of the diagnoses, no complication and no procedure demonstrated an influence on the re- turn of our questionnaire. The questionnaire revealed profound impairment in our patients’ physical scores (Ta ble 1) compared to the general aged population. Less pronounced, but also present were lower estimations of general health and mental scores. Suffering from any complication was correlated with a significantly lower score in emotional role (75 vs. 31 points, p = 0.009), but in no other SF-36 sub-score. Seven out of eight SF-36 sub-scores were significantly higher in those patients who had had an arterial line. Former vasopressor therapy was associated with slightly lower physical sub-scores, but better self-assessment in mental sub-scores and the general health score (data not shown). Pre-existing cardiac disease was significantly associated with lower scores for physical functioning (29 vs. 40, p = 0.017), and the physical role (15 vs. 54, p = 0.041). The main indications for admission in all 314 patients were surgery for gastrointestinal malignancies, or emer- gencies (Table 2). 16% were trauma patients. Ta b le 1 . Results of the short-form 36 questionnaire of the evaluable study patients (n = 28) compared with data from the general population over 70 years of age [10]. maximum value is 100 for each parameter. percentiles: e.g. 25% of the study patients had a physical functioning value under 5, 50% under 30, 75% under 50, and so on. Study patients Physical func- tioning Physical role Bodily pain General health Vitality Social function- ing Emotional role Mental health Mean 33.03 25.89 45.00 43.75 43.21 66.96 51.19 64.00 Percentiles 25 5 .00 14 25 26 37 .00 48 50 30 .00 41 45 40 68 50 70 75 50 25 71 65 58 100 100 83 General population Physical functioning Physical role Bodily pain General health Vitality Social func- tioning Emotional role Mental health Mean 58.59 62.16 64.2 55.3 53.91 83.94 83.04 71.41 Percentiles 25 35 25 41 35 35 75 100 56 50 55 75 62 52 50 87.5 100 72 75 80 100 100 72 70 100 100 84 Table 2. Indication for admission to the ICU in 314 patients. n % Gastrointestinal malignancy 92 29 Ileus or bowel ischaemia 31 10 Visceral perforation 28 9 Gastrointestinal bleeding 26 8 Visceral inflammation 21 7 Surgical complication 16 5 Hip fracture 27 9 Polytrauma 22 7 Other 25 8  S. Utzolino et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1405-1412 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1408 These patients presented numerous comorbidities; the most frequent were cardiac, respiratory, neurological (mostly dementia), and diabetes (Tab le 3). Therapeutic measures included 24% needing mechanical ventilation (mean duration 5.7 +/–3.6 days), 35% were on vaso- pressors for more than one hour (mean duration 5.4 +/– 4.2 days), and 57% underwent a transfusion of blood components (at least 2 units of packed red cells or 2 units of fresh-frozen plasma). Only one of 11 attempted resuscitations after cardiac arrest was successful. Many patients developed complications in the ICU (Tab le 4), infections leading by far in 142/314 patients (45%), 70 of which were pneumonia (22%). A surgical complication occurred in 65 patients (75% were post- operative patients). Of the pre-existing diseases, only two turned out to be statistically significant risk factors for mortality in mul- tivariate analysis; namely chronic renal impairment (OR 3.35, p < 0.001), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR 3.04, p = 0.003). Of the complications suffered in the ICU, acute kid- ney failure correlated strongly with mortality, as did pneumonia and sepsis in univariate analysis of the entire follow-up period. (Table 4). Nevertheless, only pneu- monia (OR 3.01, p < 0.0001) and thromboembolism (OR 1.89, p = 0.003) remained independent predictors of mortality in multivariate analysis. Sepsis narrowly missed significance (OR 1.96, p = 0.055). The need for the following therapeutic measures cor- related closely with mortality: hemodialysis, vasopres- sors, mechanical ventilation, and having an arterial line (Table 5). Multivariate analysis left only mechanical ventilation as an independent factor (OR for survival 0.27, p < 0.001). Mean length of ICU stay was 8.53 ± 8.63 days (range, 2-78). 25% of patients had an ICU length of stay of less than 4 days, and 25% one of over 9 days. Mean APACHE 2 score (admission time) was 15.5 ± 5.1 (range, 6-38). Because we enrolled only patients 75 Tab le 3 . Pre-existing disease in 314 patients on admission to the ICU. n % Coronary heart disease 109 35 Cardiac insufficiency ≥ NYHA 2 93 30 Arterial occlusive disease 28 9 Any malignancy 137 44 Renal insufficiency 61 19 Chronic respiratory disease 109 35 Diabetes 93 30 Neurological / psychiatric disorder 122 39 Alcoholism 10 3 Other 69 22 Tabl e 4 . Odds ratios (OR) for mortality for complications suf- fered during ICU stay, univariate analysis. n = 314. n OR 95% confidence interval p Pneumonia 704.1 2.1-8.2 <0.001 Sepsis 285.5 1.6-18.5 <0.001 Acute renal failure 424.2 1.7-10.3 <0.001 Urinary tract infection 290.5 0.2-1.3 1.0 Surgical complication 650.9 0.5-1.5 0.48 Decubitus 132.1 0.5-18.3 0.06 Venous thromboembolism6 0.6 0.1-1.5 0.48 Delirium 360.7 0.4-1.9 0.54 Any complication 1.3 0.8-2.1 0.57 Table 5. Odds ratios (OR) for hospital mortality associated with therapeutic measures during ICU stay, univariate analysis. n = 314. n OR 95% confidence interval p Ventilator therapy (> 24 h)75 4.5 3.1-6.7 <0.001 Haemodialysis 17 6.8 2.5-18.8 <0.001 Vasopressor therapy 109 2.5 1.9-3.3 <0.001 Arterial line 200 1.3 1.1-2.5 0.003 Transfusion 177 1.4 1.2-1.7 0.001 Any surgery 236 1.1 0.9-1.2 0.3 years or older, 6 age points are always present. Mean APACHE 2 score was significantly higher in non-survivors than in survivors (Figur e 2). Mean core-TISS-10 score was 46.2 ± 77.9. Median was 20 (range, 0-582) over the entire ICU stay. The me- dian daily score per patient was 3.9 ± 4.7. Mean core- TISS-10 score also was significantly higher in non-survivors than in survivors (Figur e 3). 4. DISCUSSION Of our cohort’s patients 17.2% died on the ICU and 8.6% during the same hospital stay on a general ward. One year after admission, 48% were still alive. After 24, 36, and 48 months survival rates were 40%, 35%, and 32%, respectively. These results correlate well with data published elsewhere [13-15]. Generally speaking, the probability of surviving ICU admission diminishes with age, but this is no longer true beyond a certain age. Pocard et al. [16] reported a mor- tality rate of 8.5% in 182 surgical ICU patients under 75 years of age, compared with a 20% mortality rate in pa- tients over 75 years. As in other collectives, an age over 75 years alone no longer affected survival rates [17-19]. In our patients, complications were associated with sev-  S. Utzolino et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1405-1412 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1409 Figure 2. Mean APACHE 2-scores whether discharged alive or not, n = 313. Figure 3. Mean core TISS-10 counts whether discharged alive or not, n = 313. eral ICU indicators, such as core TISS-10, vasopressors, haemodialysis, and mechanical ventilation, but not with age (Table 5). Very old patients demonstrate survival similar to the younger “oldies”. Here, survival is deter- mined by biological rather than calendaric age, as de- termined by coexisting disease and APACHE score. In more than 13,000 patients over age 70, Wilson et al. [20] demonstrated that the severity of disease and health sta- tus are nearly independent of age. It has been repeatedly shown that one-third of all those over 65 years suffer from 3 to 4 chronic diseases, and almost all of those over 80 have at least one chronic disease [21]. In Pocard’s study, 93% had documented chronic disease, and so did 99% of the patients in our cohort. As evident from our data, Perdue et al. [22] found that pre-existing heart, lung, or kidney disease had a pro- nounced impact on mortality in more than 5,000 patients. They also observed that gastrointestinal and infectious complications influence outcomes, something not ap- parent in our patients. In a study of Torres et al., co- morbidity was the strongest predictor of long-term mor- tality in patients 65 years or over treated on an interme- diate care unit [23]. In an attempt to develop quality in- dicators for perioperative care in elderly surgical patients, McGory et al. [24] found a high impact of comorbidity. The high mortality rate of trauma patients is striking in our study (40.7% for hip fracture, 35.3% for other frac- tures). The Scottish Hip Fracture Audit database re- vealed outcomes in elderly patients being dependent on co-morbidity, but not on management [25]. Evidently, elderly trauma patients requiring prolonged intensive care present a group at very high risk, especially when very old. The usual elderly patient with a hip fracture stays in the ICU for only one night postoperatively. Those patients that require a prolonged stay due to co-morbidity have a high mortality rate in our cohort. Neurological disease, predominantly dementia and to a certain degree transient delirium, significantly reduced long-term survival in our patients. There was no influ- ence on ICU or hospital mortality. Pisani [26] also stated that dementia did not reduce ICU survival in elderly patients, but Hamrick [27] found that it did so in patients with delirium. As described in numerous publications [28-30], sepsis and multiple organ failure are the most important determinants of mortality in geriatric trauma patients. In our study, patients with pneumonia had a significantly elevated risk of death (OR 4.11) and had a longer ICU length of stay. Due to our study’s retrospec- tive character, we cannot differentiate between compli- cations as a reason for or a sequel to prolonged ICU stay. Surgical complications, wound infections, and colo- nization with multiple drug-resistant rods had no impact on mortality in our predominantly (75%) surgical pa- tients. Although often observed elsewhere [31], coloni- zation with multiple drug-resistant rods had neither an influence on hospital nor ICU length of stays, nor on long-term survival. The aforementioned incidence of complications did not correlate with age in our patients, but it did so with  S. Utzolino et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1405-1412 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1410 Table 6. Mean values of intensive care parameters whether suffering from a distinct complication or not. Age (y) Hospital LOS APACHE TISS 10 total TISS median Ventilator days Dialysis days Va so - presssor days Pneumonia no 80.9 6.4 14.5 28.0 3.4 0.6 0.1 0.9 yes 80.8 16.3* 18.9* 110.3* 5.8* 4.2* 1.0* 5.3* Decubitus no 80.9 8.1 15.3 43.0 3.9 1.3 0.2 1.6 yes 80.3 18.0 19.5* 110.2* 3.8 2.8 2.4* 7.9* Surgical complication no 81.0 7.3 15.5 39.2 3.9 1.2 0.2 1.5 yes 80.2 13.4* 15.4 74.3* 4.0 2.1 0.7* 3.4* Delirium no 80.9 8.6 15.4 46.9 4.1 1.4 0.3 1.9 yes 80.8 8.6 16.3 44.8 3.1 1.2 0.2 1.8 Sepsis no 81.0 7.2 14.9 34.8 3.4 0.9 0.1 1.2 yes 79.2 22.3* 21.8* 165.4* 9.2* 5.9* 1.7* 8.8* Acute renal failure no 81.0 7.0 14.7 30.7 3.2 0.8 0.0 1.0 yes 77.6 19.0* 20.2* 148.1* 8.7* 5.3* 1.7* 7.6* Any complication no 80.9 5.7 14.3 23.3 3.2 0.5 0.1 0.7 yes 80.8 11.0* 16.6* 66.4* 4.6 2.2* 0.4 2.9* * denotes p < .05 for the difference as calculated by the Mann-Whitney U-test; APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation 2 score; TISS = Therapeutic Intervention and Scoring System; LOS = Length of Stay (days). the APACHE 2 score on admission and with pre-existing disease. We found a significant correlation between COPD and wound infection, and between COPD and sepsis. These observations accommodate easily the hy- pothesis of co-morbidities as important determinants of outcome. Hospital discharge alive correlated with the APACHE 2 score, core-TISS-10 score, ventilator days, vasopressor days and days with haemodialysis (Table 6), but not with age. The results of our questionnaire show a remarkably reduced quality of life in our post-ICU elderly patients compared with an average matched population. This is true above all for the physical or bodily items of the SF36. 75% of our patients have a physical functioning score below 50 points, whereas the mean score in the general population in elderly patients is 58. Only 25% of the general population has a score under 35, compared with our patients’ average score of 33. We obtained sim- ilar results for physical role and bodily pain. Indeed, our patients’ results lie consistently within the range of the 25-percentile in the general elderly population. Other investigators, however, reported fair to good cognitive and physical functioning in survivors of surgical ICU treatment at the age of 80 or more [32]. Kaarlola et al. observed high mortality and substantially worse out- comes as measured in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in ICU patients over 65 compared to younger ICU patients [33]. On the other hand, the higher scores for mental health and emotional role may indicate that our patients adapt well to physical disabilities. Merlani et al. reported a decrease in quality of life in their study including 141 elderly surgical ICU patients, and 81% of the survivors lived at home 2 years after discharge [34]. The phenomenon of subjectively-reported better health than measured by objective criteria in the elderly was described in 1993 by Rockwood et al. [35]. There are conflicting results about long-term inten- sive-care outcomes in the elderly [36-40], and the deli- very of ICU treatment in these patients is under intense debate [41-44]. The main drawbacks of our study are its retrospective character, which only permits hypotheses about causality, and the disappointingly low number of returned questionnaires. The latter, however, is certainly due to the numerous deceased or disabled patients, re- flecting the burden of the post-ICU course in the elderly. Baldwin et al. [45] assessed the quality of life of general adult ICU survivors using the SF-36 at only 4 months post ICU. After this short period in a non-geriatric cohort only 65 of 175 questionnaires had sufficient data for analysis. It is possible that those able or willing to send back the questionnaire present a positive selection, so that overall outcome results might be even worse. Fur- ther, most of our patients were intermediate care patients, as reflected by the low APACHE 2 scores. Our results  S. Utzolino et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1405-1412 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1411 may not apply to critically ill older patients. Our study includes patients of 75 years or more. By contrast com- parable groups in other studies are typically aged 70 years or more. This mismatch, although small, can be expected to cause a bias towards worse scores in our patients. 5. CONCLUSION Age alone does not imply a worse outcome in surgical ICU patients over 74 years of age. The development of pneumonia is an independent predictor of mortality. The main determinant of mortality is pre-existing disease. Quality of life after discharge may be dramatically im- paired, even in a mixed intermediate care or critically ill older population. Further research is needed to address the long-term health implications of ICU treatment in the elderly. REFERENCES [1] Statistisches bundesamt (federal bureau of statistics ger- many). http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/ [2] Etzioni, D.A., Liu, J.H., Maggard, M.A. and Ko, C.Y. (2003) The aging population and its impact on the sur- gery workforce. Annals of Surgery, 238, 170-177. [3] Knaus, W.A., Draper, E.A., Wagner, D.P. and Zimmer- man, J.E. (1985) Apache ii: A severity of disease classi- fication system. Critical Care Medicine, 13, 818-829. [4] Knaus, W.A., Zimmerman, J.E., Wagner, D.P., Draper, E.A. and Lawrence, D.E. (1981) Apache-acute physiol- ogy and chronic health evaluation: A physiologically based classification system. Critical Care Medicine, 9, 591-597. [5] German Institute of Medical Documentation and Infor- mation. http://www.dimdi.de [6] Cullen, D.J., Civetta, J.M., Briggs, B.A. and Ferrara, L.C. (1974) Therapeutic intervention scoring system: A method for quantitative comparison of patient care. Critical Care Medicine, 2, 57-60. [7] Miranda, D.R., De Rijk, A. and Schaufeli, W. (1996) Simplified therapeutic intervention scoring system: The tiss-28 items-results from a multicenter study. Critical Care Medicine, 24, 64-73. [8] Ware, J.E. and Sherbourne, C.D. (1992) The mos 36-item short-form health survey (sf-36). I. Conceptual frame- work and item selection. Medical Care, 30, 473-483. [9] Mchorney, C.A., Ware, J.E., Rogers, W., Raczek, A.E. and Lu, J.F. (1992) The validity and relative precision of mos short-and long-form health status scales and dart- mouth coop charts. Results from the medical outcomes study,” Medical Care, 30, 253-265. [10] Garratt, A.M., Ruta, D.A., Abdalla, M.I., Buckingham, J.K. and Russell, I.T. (1993) The sf36 health survey questionnaire: An outcome measure suitable for routine use within the nhs? British Medical Journal, 306, 1440-1444. [11] Bullinger, M.K.I. (1994) Sf 36-fragebogen zum gesund- heitszustand-handlungsanweisungen. [12] Singh, N., Rogers, P., Atwood, C.W., Wagener, M.M. and Yu, V.L. (2000) Short-course empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with pulmonary infiltrates in the intensive care unit. A proposed solution for indiscriminate antibi- otic prescription. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 162, 505-511. [13] Campion, E.W., Mulley, A.G., Goldstein, R.L., Barnett, G.O. and Thibault, G. E. (1981) Medical intensive care for the elderly. A study of current use, costs, and out- comes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 246, 2052-2056. [14] Dragsted, L. and Qvist, J. (1989) Outcome from inten- sive care. Iii. A 5-year study of 1308 patients: Activity levels,” European Journal of Anaesthesiol, 6, 385-396. [15] Bo, M., Massaia, M., Raspo, S., Bosco, F., Cena, P., Mo- laschi, M. and Fabris, F. (2003) Predictive factors of in- hospital mortality in older patients admitted to a medical intensive care unit. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 529-533. [16] Pocard, M., Frileux, P., Vaillant, J.C., Ollivier, J.M., Gen- til, B. and Parc, R. (2001) Intensive care after digestive surgery: The outcome in elderly patients. Annales de Chirurgie, 126, 127-132. [17] Kleinpell, R.M. and Ferrans, C.E. (1998) Factors in- fluencing intensive care unit survival for critically ill el- derly patients. Heart Lung, 27, 337-343. [18] Udekwu, P., Gurkin, B., Oller, D., Lapio, L. and Bourbi- na, J. (2001) Quality of life and functional level in elder- ly patients surviving surgical intensive care. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 193, 245-249. [19] Roche, V.M., Kramer, A., Hester, E. and Welsh, C.H. (1999) Long-term functional outcome after intensive care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47, 18-24. [20] Wilson, M.T., Crawford, K.L. and Shabot, M.M. (2000) Intensive care unit outcomes of surgical centenarians: The “Oldest old” Of the new millennium. American Sur- gery, 66, 870-873. [21] Pellicane, J.V., Byrne, K. and Demaria, E.J. (1992) Pre- ventable complications and death from multiple organ failure among geriatric trauma victims. Journal of Tr aum a, 33, 440-444. [22] Perdue, P.W., Watts, D.D., Kaufmann, C.R. and Trask, A.L. (1998) Differences in mortality between elderly and younger adult trauma patients: Geriatric status increases risk of delayed death. Journal of Trauma, 45, 805-810. [23] Torres, O.H., Francia, E., Longobardi, V., Gich, I., Benito, S. and Ruiz, D. (2006) Short- and long-term outcomes of older patients in intermediate care units. Intensive Care Medicine, 32, 1052-1059. [24] Mcgory, M.L., Kao, K.K., Shekelle, P.G., Rubenstein, L.Z., Leonardi, M.J., Parikh, J.A., Fink, A. and Ko, C.Y. (2009) Developing quality indicators for elderly surgical patients. Annals of Surgery, 250, 338-347. [25] Holt, G., Smith, R., Duncan, K., Hutchison, J.D. and Gregori, A. (2008) Outcome after surgery for the treat- ment of hip fracture in the extremely elderly. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 90, 1899-1905. [26] Pisani, M.A., Redlich, C.A., Mcnicoll, L., Ely, E.W., Friedkin, R.J. and Inouye, S.K. (2005) Short-term out- comes in older intensive care unit patients with dementia. Critical Care Medicine, 33, 1371-1376.  S. Utzolino et al. / Health 2 (2010) 1405-1412 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 1412 [27] Hamrick, I., Weiss, G., Lippert, H. and Meyer, F. (2005) Geriatric problems in the perioperative management of surgical interventions. Zentralbl Chir , 130, 41-47. [28] Scalea, T.M., Simon, H.M., Duncan, A.O., Atweh, N.A., Sclafani, S.J., Phillips, T.F. and Shaftan, G.W. (1990) Ge- riatric blunt multiple trauma: Improved survival with early invasive monitoring. Journal of Trauma, 30, 129-134; discussion 134-126. [29] Orwelius, L., Nordlund, A., Edell-Gustafsson, U., Si- monsson, E., Nordlund, P., Kristenson, M., Bendtsen, P. and Sjoberg, F. (2005) Role of preexisting disease in pa- tients’ perceptions of health-related quality of life after intensive care. Critical Care Medicine, 33, 1557-1564. [30] Montuclard, L., Garrouste-Orgeas, M., Timsit, J.F., Mis- set, B., De Jonghe, B. and Carlet, J. (2000) Outcome, functional autonomy, and quality of life of elderly pa- tients with a long-term intensive care unit stay. Critical Care Medicine, 28, 3389-3395. [31] Shurland, S., Zhan, M., Bradham, D.D. and Roghmann, M.C. (2007) Comparison of mortality risk associated with bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant and methicil- lin-susceptible staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 28, 273-279. [32] De Rooij, S.E., Govers, A.C., Korevaar, J.C., Giesbers, A.W., Levi, M. and De Jonge, E. (2008) Cognitive, func- tional, and quality-of-life outcomes of patients aged 80 and older who survived at least 1 year after planned or unplanned surgery or medical intensive care treatment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56, 816-822. [33] Kaarlola, A., Tallgren, M. and Pettila, V. (2006) Long- term survival, quality of life, and quality-adjusted life- years among critically ill elderly patients. Critical Care Medicine, 34, 2120-2126. [34] Merlani, P., Chenaud, C., Mariotti, N. and Ricou, B. (2007) Long-term outcome of elderly patients requiring intensive care admission for abdominal pathologies: Sur- vival and quality of life. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 51, 530-537. [35] Rockwood, K., Noseworthy, T.W., Gibney, R.T., Kono- pad, E., Shustack, A., Stollery, D., Johnston, R. and Grace, M. (1993) One-year outcome of elderly and young patients admitted to intensive care units. Critical Care Medicine, 21, 687-691. [36] Jandziol, A.K. and Ridley, S.A. (2000) Validation of outcome prediction in elderly patients. Anaest hesia, 55, 107-112. [37] Rellos, K., Falagas, M.E., Vardakas, K.Z., Sermaides G. and Michalopoulos A. (2006) Outcome of critically ill oldest-old patients (aged 90 and older) admitted to the intensive care unit. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54, 110-114. [38] Akposso, K., Hertig, A., Couprie, R., Flahaut, A., Alberti, C., Karras, G.A., Haymann, J.P., Costa De Beauregard, M.A., Lahlou, A., Rondeau, E. and Sraer, J.D., (2000) Acute renal failure in patients over 80 years old: 25- years’ experience. Intensive Care Medicine, 26, 400-406. [39] Heijmeriks, J.A., Pourrier, S., Dassen, P., Prenger, K. and Wellens, H.J. (1999) Comparison of quality of life after coronary and/or valvular cardiac surgery in patients > or = 75 years of age with younger patients. American Jour- nal of Cardiology, 83, 1129-1132. [40] Mittermair, R.P. and Muller, L.C. (2002) Quality of life after cardiac surgery in the elderly. Journal of Cardi- ovascular Surgery (Torino), 43, 43-47. [41] Szalados, J. E. (2004) Age and functional status as de- terminants of intensive care unit outcome: Sound basis for health policy or tip of the outcomes iceberg. Critical Care Medicine, 32, 291-293. [42] Garrouste-Orgeas, M. and Carlet, J. (2005) Predicting whether the icu can help older patients: Score needed. Critical Care, 9, 331-332. [43] De Rooij, S.E., Abu-Hanna, A., Levi, M. and De Jonge, E. (2005) Factors that predict outcome of intensive care treatment in very elderly patients: A review. Critical Care, 9, 307-314. [44] Ranhoff, A.H., Rozzini, R., Sabatini, T., Cassinadri, A., Boffelli, S., Ferri, M., Travaglini, N., Ricci, A., Morandi, A. and Trabucchi, M. (2006) Subintensive care unit for the elderly: A new model of care for critically ill frail el- derly medical patients. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 1, 197-203. [45] Baldwin, F.J., Hinge, D., Dorsett, J. and Boyd, O.F. (2009) Quality of life and persisting symptoms in inten- sive care unit survivors: Implications for care after dis- charge. BMC Research Notes, 2, 160. |