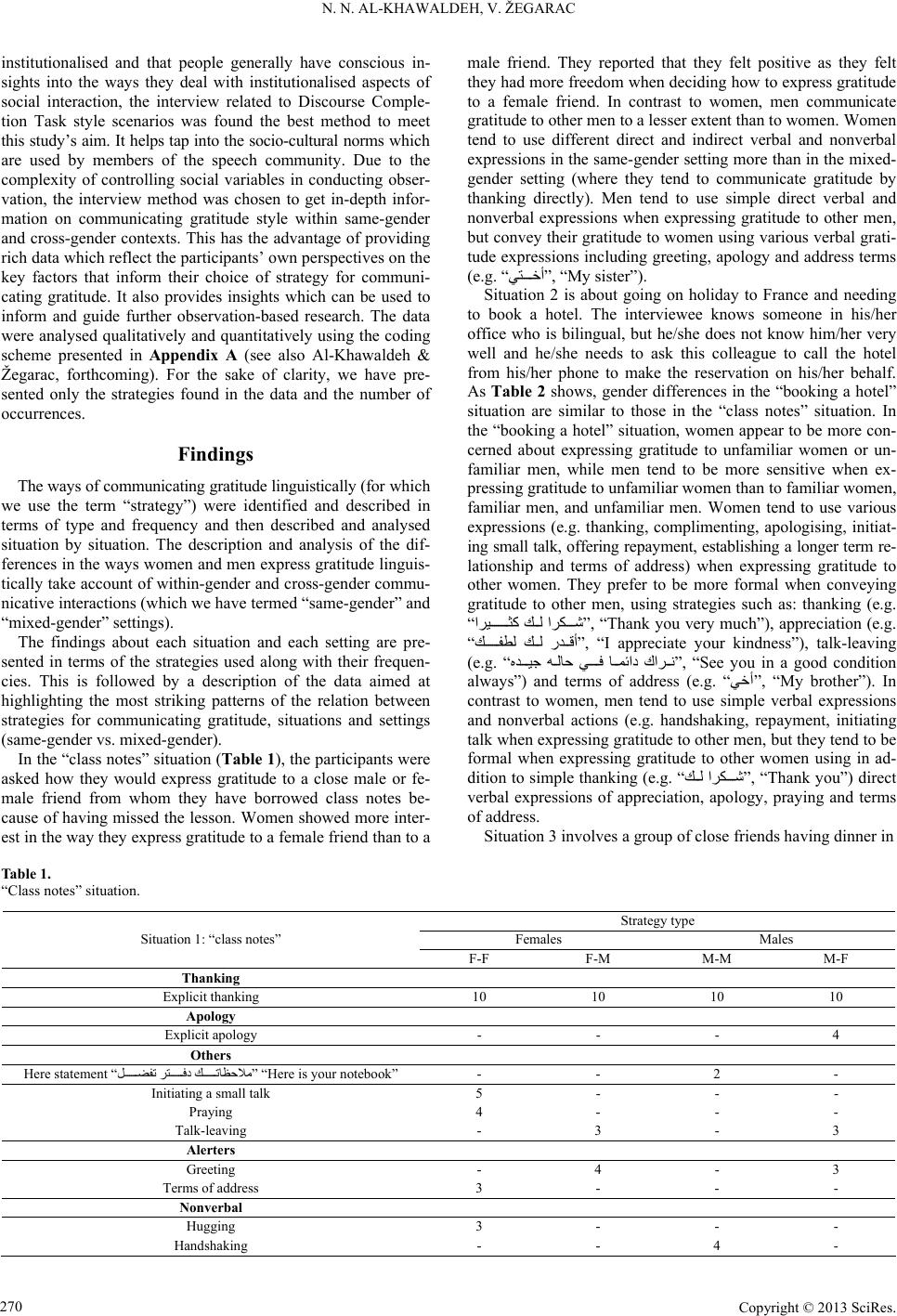

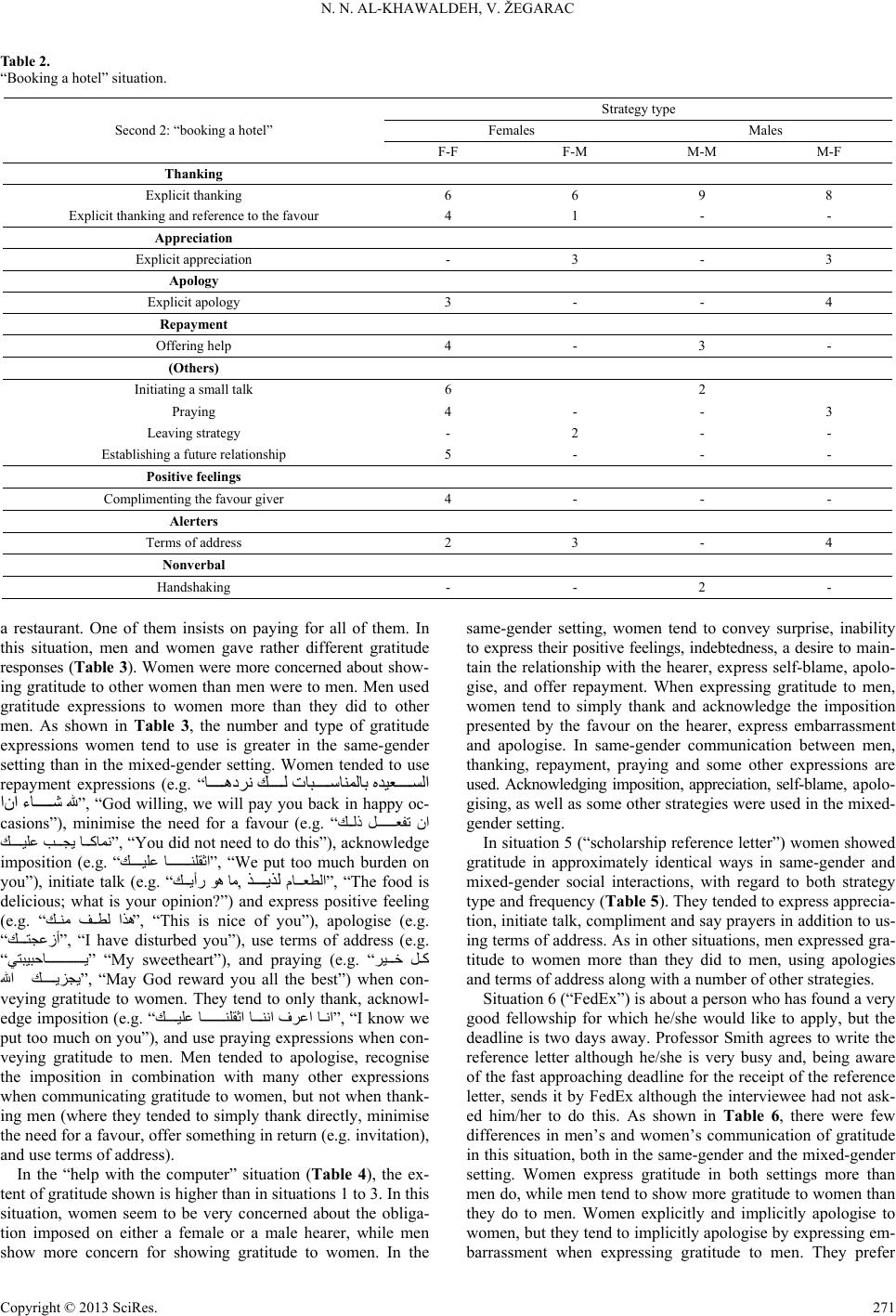

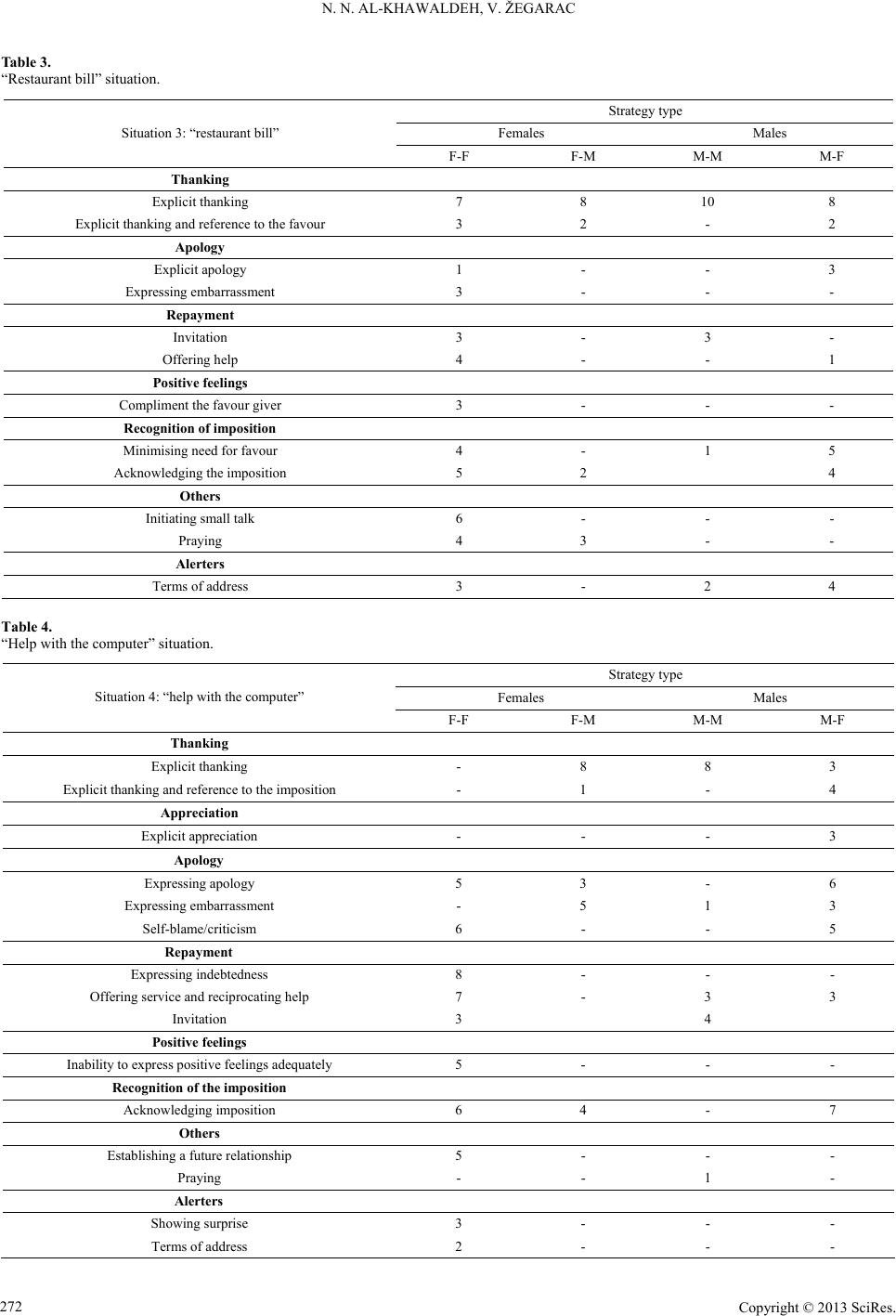

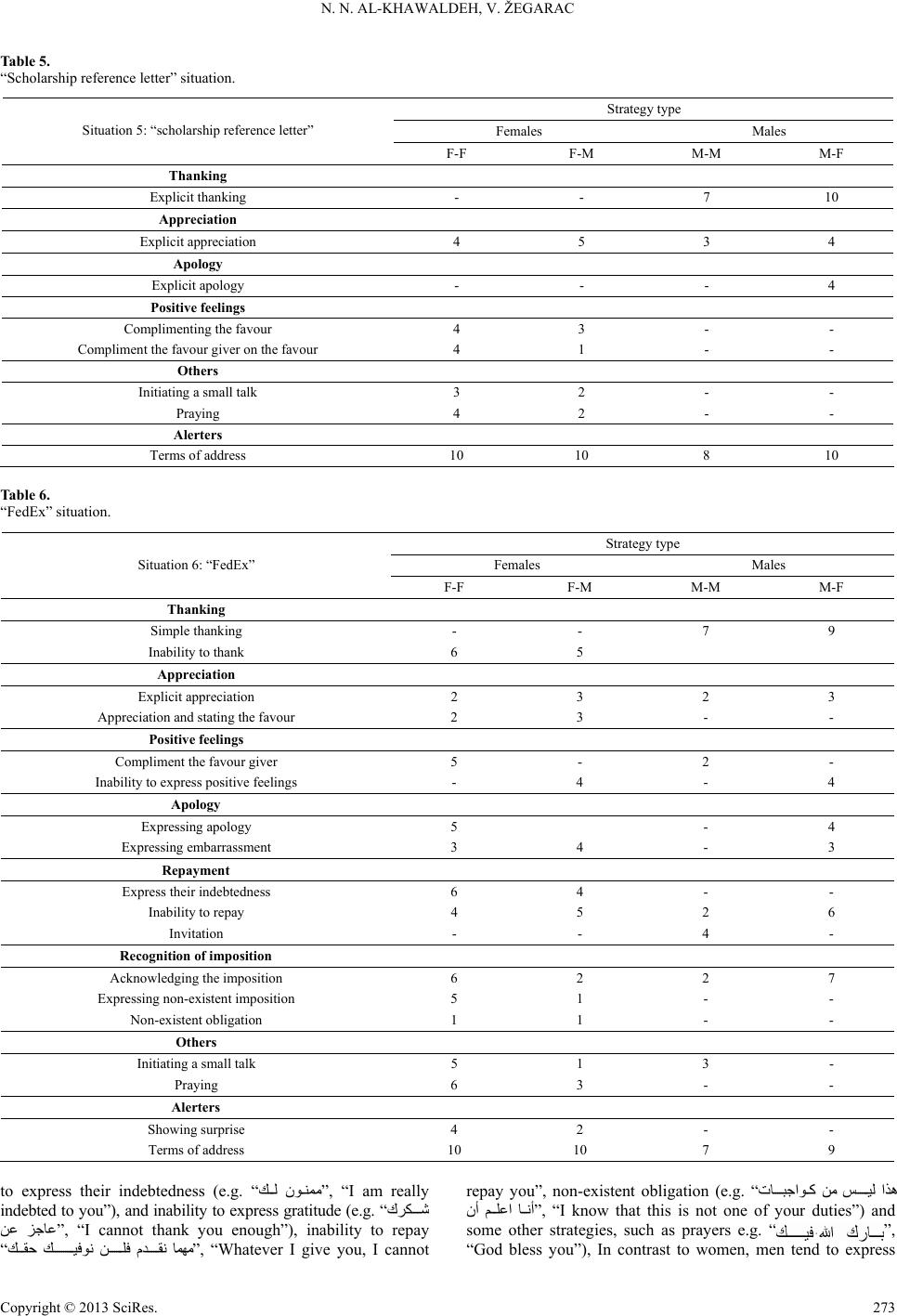

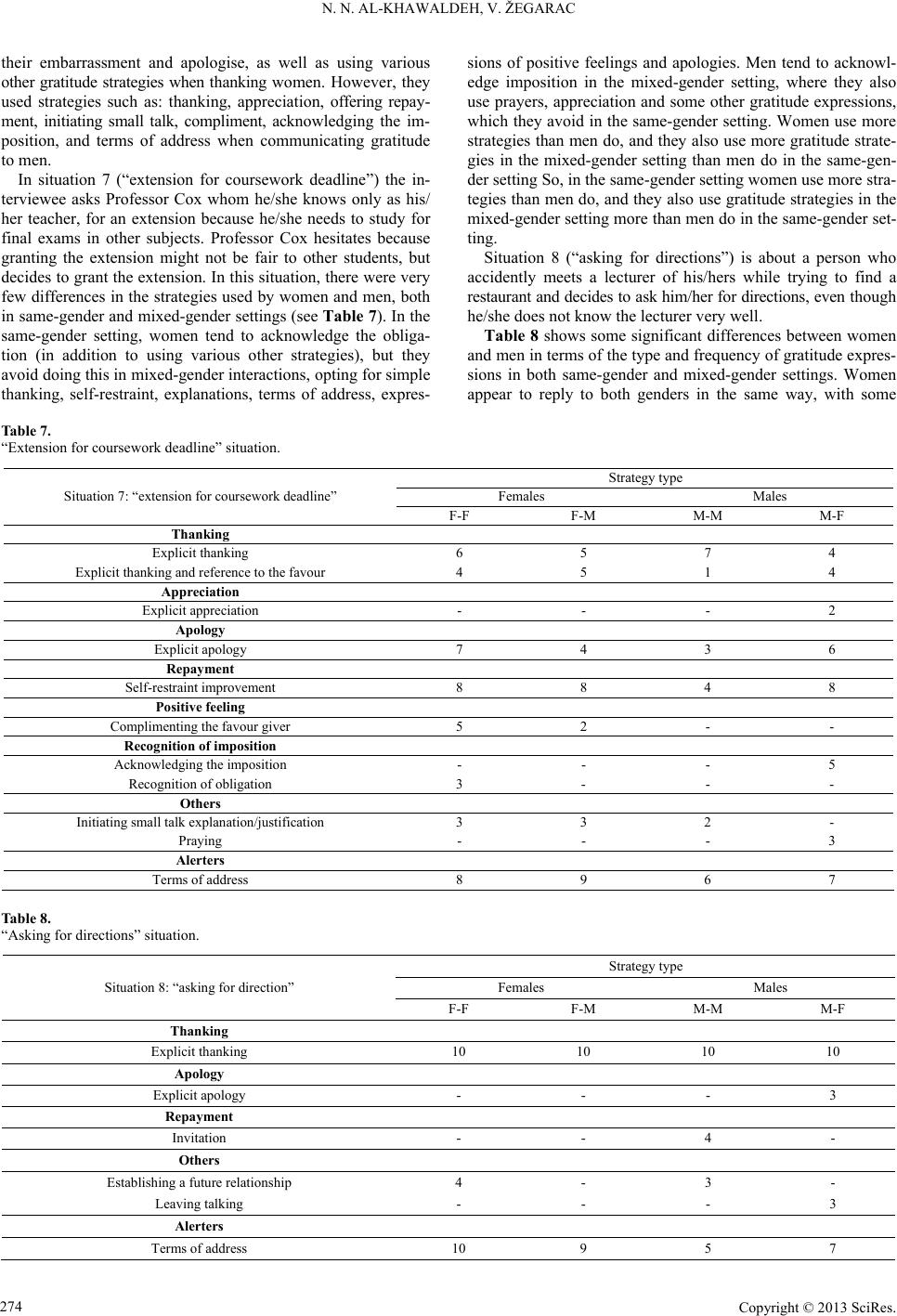

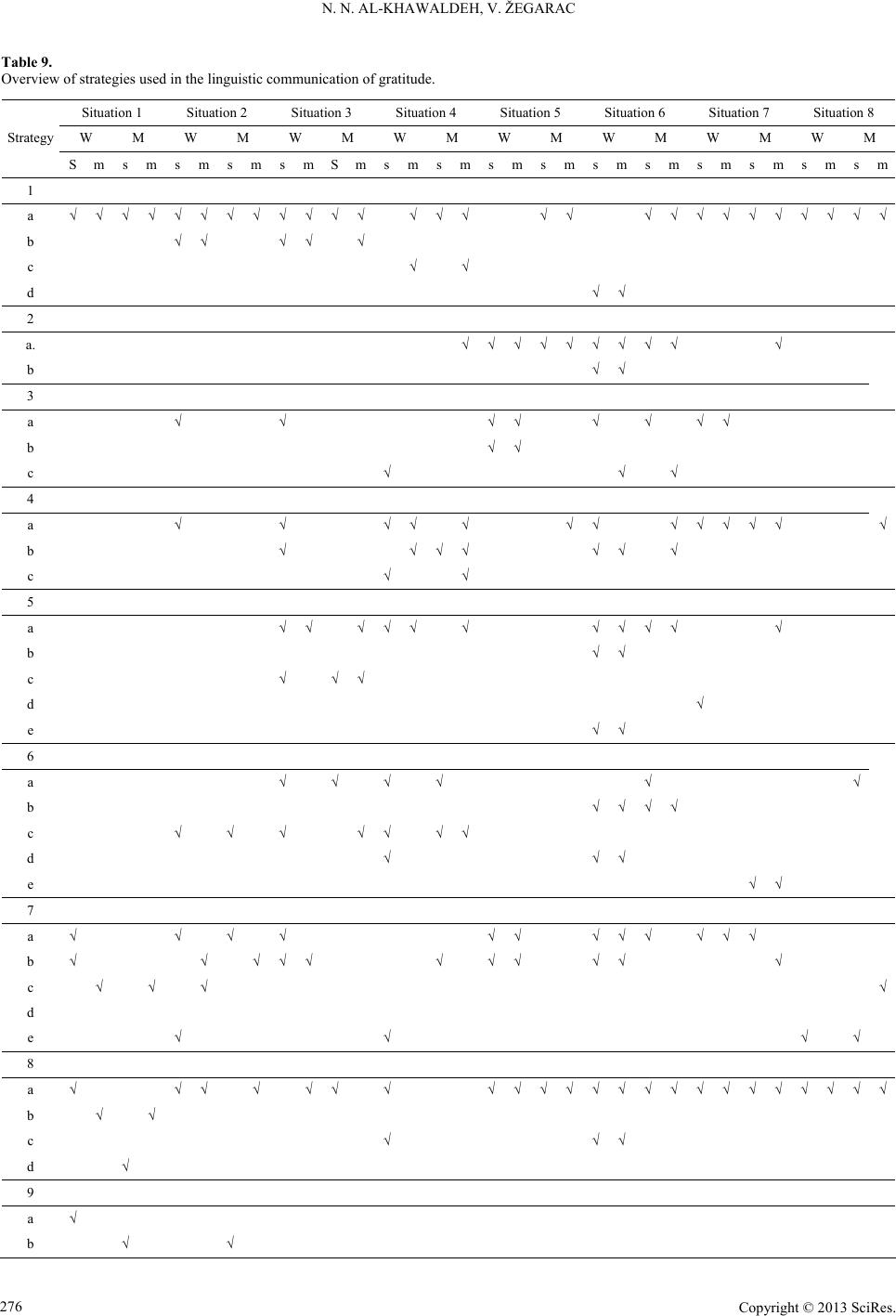

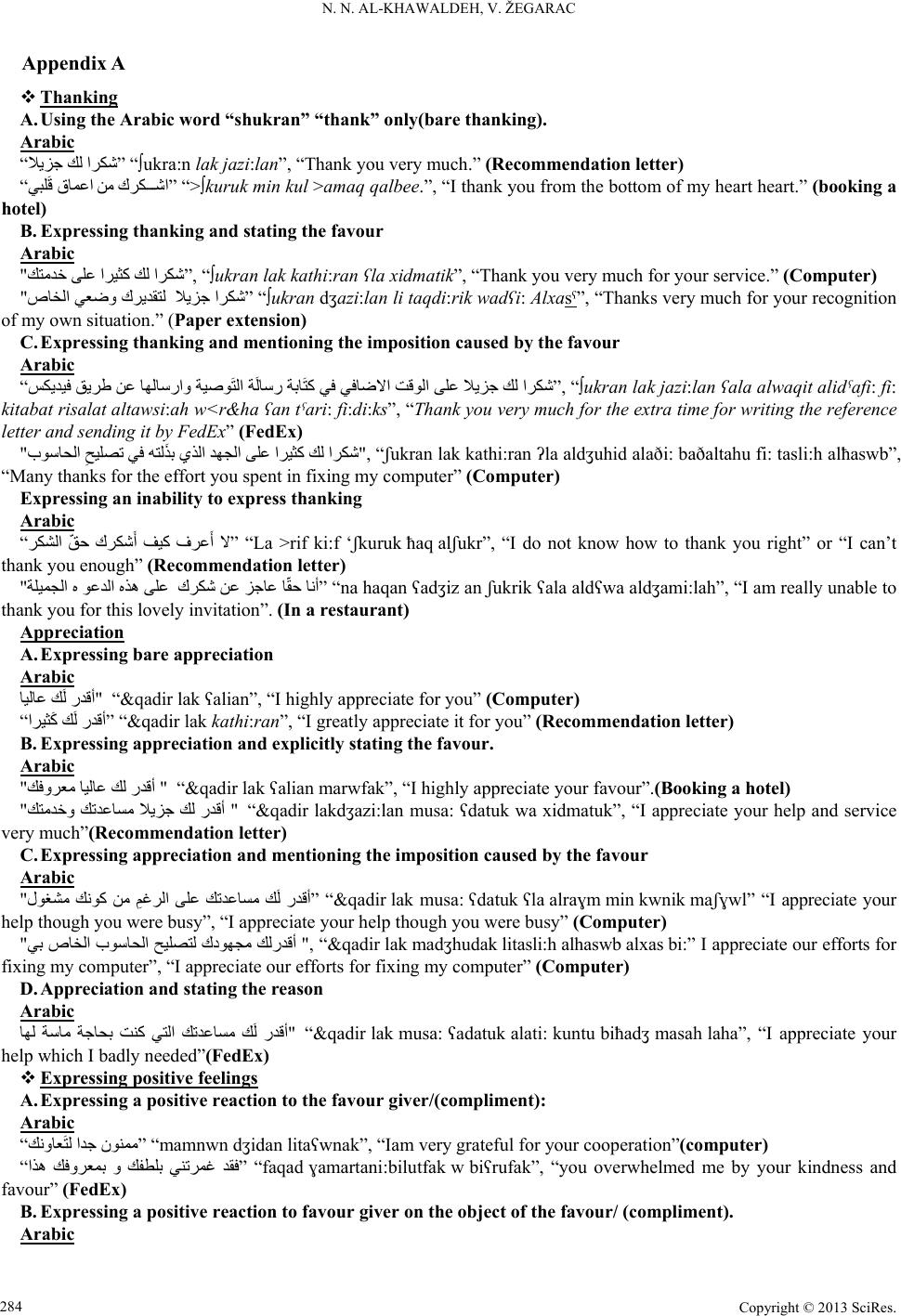

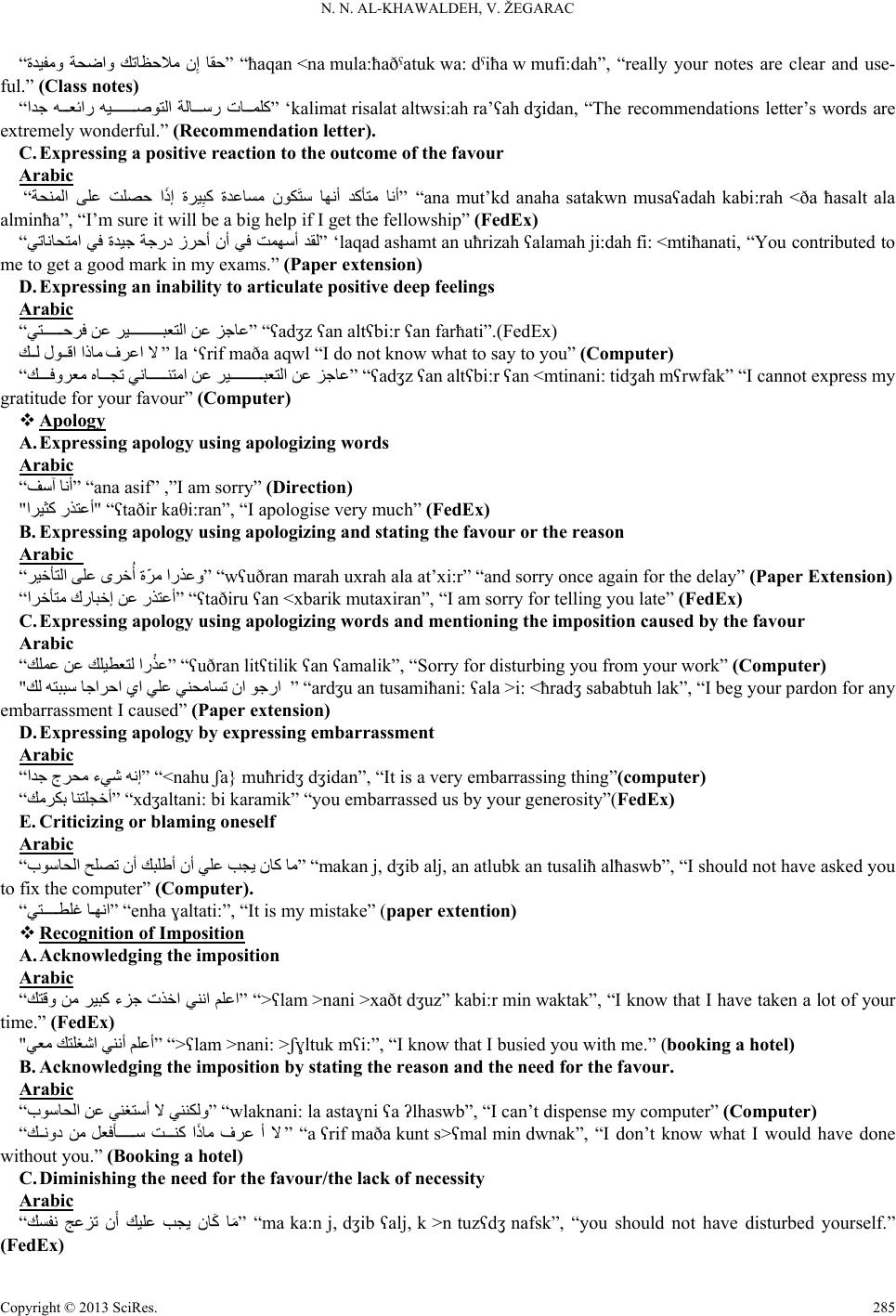

Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.3, 268-287 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.33035 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 268 Gender and the Communication of Gratitude in Jordan Nisreen Naji Al-Khawaldeh*, Vladimir Žegarac University of Bedfordshire, Luton, UK Email: *nisreen.al-khawaldeh@beds.ac.uk, vladimir.zegarac@beds.ac.uk Received July 15th, 2013; revised August 22nd, 2013; accepted September 1st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Nisreen Naji Al-Khawaldeh, Vladimir Žegarac. This is an open access article distributed un- der the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This paper examines Jordanians’ perceptions of the ways and the extent to which gender influences the communication of gratitude in some everyday situations. The qualitative analysis of 20 interviews reveals a considerable influence of gender on the performance and reception of this communicative act. Differ- ences between women and men were found in both same-gender and mixed-gender interactions in respect of the mandatoriness and the ways of communicating gratitude. The data show that Jordanian women ap- pear to value expressing gratitude more than Jordanian men do. There is no clear-cut answer to the ques- tion of who conveys gratitude more: women or men. However, it is clear that several factors affect the production and the reception of the linguistic expression of gratitude, including: the status differential between the speaker and the hearer, the degree of familiarity between them and the weight of obligation on the speaker. Women tend to communicate gratitude to women more than men do to men, whereas men are particularly aware of the need to be polite when relating to women (especially in unfamiliar and high imposition contexts). The findings strongly support the view that generalisations about the role of gender in conversation should take account of context in the production and interpretation of communicative be- haviour and point to some directions for further gender-focused investigation of the linguistic communi- cation of gratitude within and across cultures. Keywords: Gratitude Expression; Cross-Gender Interaction; Socio-Cultural Pragmatics; Politeness Introduction The relation between language use and gender has been much explored in the field of socio-linguistics over the past forty years or so. Nevertheless, some important questions remain wide open. One of these is the issue of whether women’s and men’s speech reflect the power differential in social situations (see Tannen, 1999; Mills, 2003). Systematic differences in wo- men’s and men’s speech have been explained in two main ways. Spolsky (1998) argues that differences in access to education are responsible for differences in speech and explains this in terms of the difference in educational opportunities for girls and boys. However, it seems equally plausible to assume that these differences reflect different patterns of socialization of girls and boys throughout childhood. In other words, girls are taught to think and behave like girls and boys to think and behave like boys. A number of influential studies show that differences in the linguistic behaviour of men and women are rooted in dif- ferences in the social construction of gender (Trudgill, 1974; Crawford, 1995). Men and women are social beings with dif- ferent social roles. As Ochs (1992) argues, particular linguistic forms should not be labelled as “masculine” or “feminine” be- cause they typically do not appear only in the speech of men or women. Brown (1998) also maintains that situations of social interaction are very important for analysing language use as they provide evidence of the social motivations which inform linguistic choices. In other words, a person’s knowledge of the relation between language and gender includes a tacit under- standing of the ways’ particular linguistic forms can be used to meet specific pragmatic norms and participant expectations in particular types of communication situation, and these norms and expectations are related to the social identities of the par- ticipants. Johnson and Roen (1992) have also highlighted the significant role contextual variables play in shaping gender- language differences. In view of these observations, it is some- what surprising that most politeness research which focuses on gender differences does not investigate them in relation to com- munication situations, but focuses on gender differences and patterns of language use per se. For this reason, it falls short of addressing the issue of whether and how the observed speech patterns reflect particular activities in which the participants are engaged or different degrees of men’s and women’s involve- ment in these activities and the contextual assumptions associ- ated with them. The study presented in this article investigates socio-cultural constraints that influence the ways men and women linguisti- cally communicate gratitude in the culture of Jordan. Jordan is a conservative tribal society which places some (largely cul- ture-specific) restrictions on male-female social interactions. When Jordanians interact with each other, they attach great sig- nificance to socio-cultural and religious norms of communica- tion. This is hardly surprising, as both the production of and the response to a linguistic expression of gratitude are sensitive to, and are largely shaped by, face concerns (see Brown & Levin- son, 1987; Al Khawaldeh & Žegarac, 2013a) and some other variables, such as power, distance and formality, which are uni- versals with different cultural realisations. *Corresponding author.  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 269 The study is important in three main respects. First, it makes a contribution to the investigation of gender differences in a particular culture—that of Jordan—where gender differences in linguistic communication have not been investigated exten- sively so far. Second, the study provides evidence for the view that generalisations about gender differences in communication need to take account of the situational context and identifies some important aspects of the socio-situational setting which systematically influence the context (where the term “context” refers to the set of assumptions used in the production and the comprehension of a communicative act). Third, the findings highlight the relation between the production of linguistic be- haviour which communicates gratitude and the socio-cultural expectations of the hearers in a way which brings us closer to a better understanding of the complex interplay between cogni- tive and socio-pragmatic factors in the production and the in- terpretation of the linguistic expression of gratitude. From the cognitive-psychological perspective on face, positive politeness is related to expressing inclusion and social approval, while ne- gative politeness calls for expressing restraint (Pan, 2000). From the socio-pragmatic perspective, polite behaviour is regulated by social norms. However, neither the cognitive-psychological nor the socio-pragmatic approach provides the basis for predicting how people behave in actual social situations. The present study identifies the linguistic strategies used for expressing gratitude in relation to the degree of imposition presented by the action being thanked for, the status and power differential between the participants and cultural norms and values. In this way, our re- search paves the way for further studies which will bring us closer to integrating the cognitive-psychological perspective on face and the socio-pragmatic norms of communication into a realistic predictive model of the linguistic communication of gratitude. Methodology Research Aim The main empirical aim of this paper is to provide a better insight into the relation between situations, strategies and gen- der in the culture of Jordan. This study focuses on the relation between participants’ gender, the linguistic communication of gratitude and the values and attitudes attached to the linguistic communication of gratitude. It examines the ways Jordanian women and men express gratitude and whether they exhibit differences in terms of the frequency and the types of strategy used. Research Participants The participants were 10 female and 10 male postgraduate Jordanian students aged between 28 and 33 from southern and northern tribal rural parts of Jordan (Al-Mafraq, Al-Tafilah, Al- Karak and others) as representative of the national culture. Research Methods The participants were interviewed about their perceptions and opinions about gender-related behavioural differences in eight social situations, focusing on the ways they would express grati- tude to same and opposite gender interlocutors in each of the eight situation and why they would choose some ways of ex- pressing gratitude in preference to others. This was done so that the participants’ gratitude behaviour can be described not only in light of the thanker’s and the thankee’s gender, but also by taking account of the gratitude expression context as a gateway to exploring other factors, namely social status, social distance, the type of imposition and the weightings placed on these fac- tors. This gives us a better insight into gender related variation in the use and intensity of gratitude expression. The participants were presented with the following situations: Situation 1 (“class notes”): expressing gratitude to a friend for having lent class notes to the interviewee who had missed a lecture. Situation 2 (“booking a hotel”): the interviewee is going on a holiday to France and needs to book a hotel. The interviewee knows someone in his/her office who is bilingual but he/she does not know him/her very well and he/she needs to ask this colleague to call the hotel from his/her phone to make the res- ervation on the interviewee’s behalf. Situation 3 (“restaurant bill”): the interviewee is with a group of close friends. They are having dinner in a restaurant. One of the group insists on paying for all of them. The interviewee knows that the person who insists on paying the bill can easily afford it, but insists that the bill should be split. His/her friend is adamant, puts her/his credit card down on the plate with the bill and pays. Situation 4 (“help with the computer”): the interviewee is having trouble with his/her computer, which keeps crashing. He/she knows someone at school who knows a lot about com- puters and the interviewee asks the person to help him/her even though he/she is not a close friend. The person hesitates be- cause he/she is very busy, but then agrees to help, and ends up spending the whole afternoon fixing the interviewee’s computer for free. Situation 5 (“scholarship reference letter”): the interviewee is applying for a scholarship. A letter of reference is required from three lecturers. The interviewee knows Doctor Barwick well (having taken two courses which he/she teaches) and de- cides to ask him/her to write a letter of reference for him/her. Doctor Barwick agrees to write the letter. Situation 6 (“FedEx”): the interviewee has found information about a very good fellowship for which he/she would like to apply, but the deadline is two days away. He/she asks Professor Smith, whom she knows very well, to write a letter of reference for him/her. Professor Smith hesitates because he/she is very busy, but he/she agrees to write the letter. The following day, the interviewee meets Professor Smith, who tells him/her that he/she has sent the letter by FedEx. Situation 7 (“extension for coursework deadline”): the inter- viewee is asking Professor Cox whom he/she knows only as his/her teacher, for an extension because he/she needs to study for final exams in other courses. Professor Cox hesitates be- cause it won’t be fair to other students in class, but then he/she agrees to give the interviewee the extension. Situation 8 (“asking for directions”): the interviewee has ar- ranged to meet a friend at a restaurant in a town where he/she has never been before. He/she arrives at a little late and since he/she has never been there before, he/she can’t find the res- taurant. Desperate to find it, he/she decides to ask anyone he/ she meets. Accidently, he/she meets a lecturer who is working in his/her university but you don’t know him/her very well. Hav- ing understood the directions, the interviewee expresses his/her gratitude by saying: Bearing in mind that ways of communicating gratitude are  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 270 institutionalised and that people generally have conscious in- sights into the ways they deal with institutionalised aspects of social interaction, the interview related to Discourse Comple- tion Task style scenarios was found the best method to meet this study’s aim. It helps tap into the socio-cultural norms which are used by members of the speech community. Due to the complexity of controlling social variables in conducting obser- vation, the interview method was chosen to get in-depth infor- mation on communicating gratitude style within same-gender and cross-gender contexts. This has the advantage of providing rich data which reflect the participants’ own perspectives on the key factors that inform their choice of strategy for communi- cating gratitude. It also provides insights which can be used to inform and guide further observation-based research. The data were analysed qualitatively and quantitatively using the coding scheme presented in Appendix A (see also Al-Khawaldeh & Žegarac, forthcoming). For the sake of clarity, we have pre- sented only the strategies found in the data and the number of occurrences. Findings The ways of communicating gratitude linguistically (for which we use the term “strategy”) were identified and described in terms of type and frequency and then described and analysed situation by situation. The description and analysis of the dif- ferences in the ways women and men express gratitude linguis- tically take account of within-gender and cross-gender commu- nicative interactions (which we have termed “same-gender” and “mixed-gender” settings). The findings about each situation and each setting are pre- sented in terms of the strategies used along with their frequen- cies. This is followed by a description of the data aimed at highlighting the most striking patterns of the relation between strategies for communicating gratitude, situations and settings (same-gender vs. mixed-gender). In the “class notes” situation (Table 1), the participants were asked how they would express gratitude to a close male or fe- male friend from whom they have borrowed class notes be- cause of having missed the lesson. Women showed more inter- est in the way they express gratitude to a female friend than to a male friend. They reported that they felt positive as they felt they had more freedom when deciding how to express gratitude to a female friend. In contrast to women, men communicate gratitude to other men to a lesser extent than to women. Women tend to use different direct and indirect verbal and nonverbal expressions in the same-gender setting more than in the mixed- gender setting (where they tend to communicate gratitude by thanking directly). Men tend to use simple direct verbal and nonverbal expressions when expressing gratitude to other men, but convey their gratitude to women using various verbal grati- tude expressions including greeting, apology and address terms (e.g. “”, “My sister”). Situation 2 is about going on holiday to France and needing to book a hotel. The interviewee knows someone in his/her office who is bilingual, but he/she does not know him/her very well and he/she needs to ask this colleague to call the hotel from his/her phone to make the reservation on his/her behalf. As Table 2 shows, gender differences in the “booking a hotel” situation are similar to those in the “class notes” situation. In the “booking a hotel” situation, women appear to be more con- cerned about expressing gratitude to unfamiliar women or un- familiar men, while men tend to be more sensitive when ex- pressing gratitude to unfamiliar women than to familiar women, familiar men, and unfamiliar men. Women tend to use various expressions (e.g. thanking, complimenting, apologising, initiat- ing small talk, offering repayment, establishing a longer term re- lationship and terms of address) when expressing gratitude to other women. They prefer to be more formal when conveying gratitude to other men, using strategies such as: thanking (e.g. “ ”, “Thank you very much”), appreciation (e.g. “ ”, “I appreciate your kindness”), talk-leaving (e.g. “ ”, “See you in a good condition always”) and terms of address (e.g. “”, “My brother”). In contrast to women, men tend to use simple verbal expressions and nonverbal actions (e.g. handshaking, repayment, initiating talk when expressing gratitude to other men, but they tend to be formal when expressing gratitude to other women using in ad- dition to simple thanking (e.g. “ ”, “Thank you”) direct verbal expressions of appreciation, apology, praying and terms of address. Situation 3 involves a group of close friends having dinner in Table 1. “Class notes” situation. Strategy type Females Males Situation 1: “class notes” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Explicit thanking 10 10 10 10 Apology Explicit apology - - - 4 Others Here statement “ ” “Here is your notebook” - - 2 - Initiating a small talk 5 - - - Praying 4 - - - Talk-leaving - 3 - 3 Alerters Greeting - 4 - 3 Terms of address 3 - - - Nonverbal Hugging 3 - - - Handshaking - - 4 -  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 271 Table 2. “Booking a hotel” situation. Strategy type Females Males Second 2: “booking a hotel” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Explicit thanking 6 6 9 8 Explicit thanking and reference to the favour 4 1 - - Appreciation Explicit appreciation - 3 - 3 Apology Explicit apology 3 - - 4 Repayment Offering help 4 - 3 - (Others) Initiating a small talk 6 2 Praying 4 - - 3 Leaving strategy - 2 - - Establishing a future relationship 5 - - - Positive feelings Complimenting the favour giver 4 - - - Alerters Terms of address 2 3 - 4 Nonverbal Handshaking - - 2 - a restaurant. One of them insists on paying for all of them. In this situation, men and women gave rather different gratitude responses (Table 3). Women were more concerned about show- ing gratitude to other women than men were to men. Men used gratitude expressions to women more than they did to other men. As shown in Table 3, the number and type of gratitude expressions women tend to use is greater in the same-gender setting than in the mixed-gender setting. Women tended to use repayment expressions (e.g. “ ”, “God willing, we will pay you back in happy oc- casions”), minimise the need for a favour (e.g. “ ”, “You did not need to do this”), acknowledge imposition (e.g. “ ”, “We put too much burden on you”), initiate talk (e.g. “ , ”, “The food is delicious; what is your opinion?”) and express positive feeling (e.g. “ ”, “This is nice of you”), apologise (e.g. “”, “I have disturbed you”), use terms of address (e.g. “” “My sweetheart”), and praying (e.g. “ ”, “May God reward you all the best”) when con- veying gratitude to women. They tend to only thank, acknowl- edge imposition (e.g. “ ”, “I know we put too much on you”), and use praying expressions when con- veying gratitude to men. Men tended to apologise, recognise the imposition in combination with many other expressions when communicating gratitude to women, but not when thank- ing men (where they tended to simply thank directly, minimise the need for a favour, offer something in return (e.g. invitation), and use terms of address). In the “help with the computer” situation (Table 4), the ex- tent of gratitude shown is higher than in situations 1 to 3. In this situation, women seem to be very concerned about the obliga- tion imposed on either a female or a male hearer, while men show more concern for showing gratitude to women. In the same-gender setting, women tend to convey surprise, inability to express their positive feelings, indebtedness, a desire to main- tain the relationship with the hearer, express self-blame, apolo- gise, and offer repayment. When expressing gratitude to men, women tend to simply thank and acknowledge the imposition presented by the favour on the hearer, express embarrassment and apologise. In same-gender communication between men, thanking, repayment, praying and some other expressions are used. Acknowledging imposition, appreciation, self-blame, apolo- gising, as well as some other strategies were used in the mixed- gender setting. In situation 5 (“scholarship reference letter”) women showed gratitude in approximately identical ways in same-gender and mixed-gender social interactions, with regard to both strategy type and frequency (Table 5). They tended to express apprecia- tion, initiate talk, compliment and say prayers in addition to us- ing terms of address. As in other situations, men expressed gra- titude to women more than they did to men, using apologies and terms of address along with a number of other strategies. Situation 6 (“FedEx”) is about a person who has found a very good fellowship for which he/she would like to apply, but the deadline is two days away. Professor Smith agrees to write the reference letter although he/she is very busy and, being aware of the fast approaching deadline for the receipt of the reference letter, sends it by FedEx although the interviewee had not ask- ed him/her to do this. As shown in Table 6, there were few differences in men’s and women’s communication of gratitude in this situation, both in the same-gender and the mixed-gender setting. Women express gratitude in both settings more than men do, while men tend to show more gratitude to women than they do to men. Women explicitly and implicitly apologise to women, but they tend to implicitly apologise by expressing em- barrassment when expressing gratitude to men. They prefer  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 272 Table 3. “Restaurant bill” situation. Strategy type Females Males Situation 3: “restaurant bill” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Explicit thanking 7 8 10 8 Explicit thanking and reference to the favour 3 2 - 2 Apology Explicit apology 1 - - 3 Expressing embarrassment 3 - - - Repayment Invitation 3 - 3 - Offering help 4 - - 1 Positive feelings Compliment the favour giver 3 - - - Recognition of imposition Minimising need for favour 4 - 1 5 Acknowledging the imposition 5 2 4 Others Initiating small talk 6 - - - Praying 4 3 - - Alerters Terms of address 3 - 2 4 Table 4. “Help with the computer” situation. Strategy type Females Males Situation 4: “help with the computer” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Explicit thanking - 8 8 3 Explicit thanking and reference to the imposition - 1 - 4 Appreciation Explicit appreciation - - - 3 Apology Expressing apology 5 3 - 6 Expressing embarrassment - 5 1 3 Self-blame/criticism 6 - - 5 Repayment Expressing indebtedness 8 - - - Offering service and reciprocating help 7 - 3 3 Invitation 3 4 Positive feelings Inability to express positive feelings adequately 5 - - - Recognition of the imposition Acknowledging imposition 6 4 - 7 Others Establishing a future relationship 5 - - - Praying - - 1 - Alerters Showing surprise 3 - - - Terms of address 2 - - -  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 273 Table 5. “Scholarship reference letter” situation. Strategy type Females Males Situation 5: “scholarship reference letter” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Explicit thanking - - 7 10 Appreciation Explicit appreciation 4 5 3 4 Apology Explicit apology - - - 4 Positive feelings Complimenting the favour 4 3 - - Compliment the favour giver on the favour 4 1 - - Others Initiating a small talk 3 2 - - Praying 4 2 - - Alerters Terms of address 10 10 8 10 Table 6. “FedEx” situation. Strategy type Females Males Situation 6: “FedEx” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Simple thanking - - 7 9 Inability to thank 6 5 Appreciation Explicit appreciation 2 3 2 3 Appreciation and stating the favour 2 3 - - Positive feelings Compliment the favour giver 5 - 2 - Inability to express positive feelings - 4 - 4 Apology Expressing apology 5 - 4 Expressing embarrassment 3 4 - 3 Repayment Express their indebtedness 6 4 - - Inability to repay 4 5 2 6 Invitation - - 4 - Recognition of imposition Acknowledging the imposition 6 2 2 7 Expressing non-existent imposition 5 1 - - Non-existent obligation 1 1 - - Others Initiating a small talk 5 1 3 - Praying 6 3 - - Alerters Showing surprise 4 2 - - Terms of address 10 10 7 9 to express their indebtedness (e.g. “ ”, “I am really indebted to you”), and inability to express gratitude (e.g. “ ”, “I cannot thank you enough”), inability to repay “ ”, “Whatever I give you, I cannot repay you”, non-existent obligation (e.g. “ ”, “I know that this is not one of your duties”) and some other strategies, such as prayers e.g. “”, “God bless you”), In contrast to women, men tend to express  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 274 their embarrassment and apologise, as well as using various other gratitude strategies when thanking women. However, they used strategies such as: thanking, appreciation, offering repay- ment, initiating small talk, compliment, acknowledging the im- position, and terms of address when communicating gratitude to men. In situation 7 (“extension for coursework deadline”) the in- terviewee asks Professor Cox whom he/she knows only as his/ her teacher, for an extension because he/she needs to study for final exams in other subjects. Professor Cox hesitates because granting the extension might not be fair to other students, but decides to grant the extension. In this situation, there were very few differences in the strategies used by women and men, both in same-gender and mixed-gender settings (see Table 7). In the same-gender setting, women tend to acknowledge the obliga- tion (in addition to using various other strategies), but they avoid doing this in mixed-gender interactions, opting for simple thanking, self-restraint, explanations, terms of address, expres- sions of positive feelings and apologies. Men tend to acknowl- edge imposition in the mixed-gender setting, where they also use prayers, appreciation and some other gratitude expressions, which they avoid in the same-gender setting. Women use more strategies than men do, and they also use more gratitude strate- gies in the mixed-gender setting than men do in the same-gen- der setting So, in the same-gender setting women use more stra- tegies than men do, and they also use gratitude strategies in the mixed-gender setting more than men do in the same-gender set- ting. Situation 8 (“asking for directions”) is about a person who accidently meets a lecturer of his/hers while trying to find a restaurant and decides to ask him/her for directions, even though he/she does not know the lecturer very well. Table 8 shows some significant differences between women and men in terms of the type and frequency of gratitude expres- sions in both same-gender and mixed-gender settings. Women appear to reply to both genders in the same way, with some Table 7. “Extension for coursework deadline” situation. Strategy type Females Males Situation 7: “extension for coursework deadline” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Explicit thanking 6 5 7 4 Explicit thanking and reference to the favour 4 5 1 4 Appreciation Explicit appreciation - - - 2 Apology Explicit apology 7 4 3 6 Repayment Self-restraint improvement 8 8 4 8 Positive feeling Complimenting the favour giver 5 2 - - Recognition of imposition Acknowledging the imposition - - - 5 Recognition of obligation 3 - - - Others Initiating small talk explanation/justification 3 3 2 - Praying - - - 3 Alerters Terms of address 8 9 6 7 Table 8. “Asking for directions” situation. Strategy type Females Males Situation 8: “asking for direction” F-F F-M M-M M-F Thanking Explicit thanking 10 10 10 10 Apology Explicit apology - - - 3 Repayment Invitation - - 4 - Others Establishing a future relationship 4 - 3 - Leaving talking - - - 3 Alerters Terms of address 10 9 5 7  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 275 elaboration when the lecturer is a woman. Though women showed interest in establishing longer-term relationships, in addi- tion to using other gratitude expressions in the same-gender setting, they avoid establishing future relationships when thank- ing men and use only simple thanking and the hearer’s title. In contrast to situations 1 to 7, in situation 8 the frequency of stra- tegies for conveying gratitude is approximately the same in same-gender settings between men and in mixed-gender set- tings. However, there is a difference in the strategies men tend to use in same-gender and mixed gender settings. When con- veying gratitude to men, they tend to try to establish a longer- term relationship and offer invitations, but, when expressing grati- tude to women, they avoid these strategies, preferring to apolo- gise. The analysis of the data according to the type of strategy used reveals some distinctive features of the relation between socio-situational factors and gender. In total, the participants used 32 strategies: (1) thanking: (1.a) explicit thanking, (1.b) explicit thanking and reference to the favour, (1.c) expressing thanks and acknowledging the imposition, (1.d) inability to thank; (2) appreciation: (2a.) explicit appreciation, (2.b) appreciation and reference to the favour; (3) expressing positive feeling: (3.a) complimenting the hearer (i.e. the favour giver), (3.b) compli- menting the favour giver on the favour, (3.c)express inability to express positive feeling adequately; (4) apology: (4.a) explicit apology, (4.b) expressing embarrassment, (4.c) self-blame/criti- cism: (5) acknowledging the imposition: (5.a) acknowledging actual imposition, (5.b) acknowledging non-existent imposition, (5.c) minimising the need for a favour, (5.d) acknowledging ac- tual obligation(s), (5.e) acknowledging non-existent obligation(s); (6) repayment: (6.a) invitation, (6.b) inability to repay, (6.c) offering to return the favour (i.e. to reciprocateby helping the hearer), (6.d) expressing indebtedness, (6.e) expressing self- restrain/improvement; (7) Others: (7.a) initiating small talk (e.g. explanation/justification), (7.b) praying, (7.c.) engaging in leave-talk, (7.d) here statement (e.g. “”, “Here you are”), (7.e) expressing a desire to establishing/maintaining a relation- ship; (8) alerters: (8.a) terms of address, (8b) greeting, (8.c) show- ing surprise and astonishment; (9) nonverbal thanking strategies which accompany linguistic ones: (9.a) hugging, (9b) handshak- ing (included here because they often accompany the linguistic expression of gratitude). An overview of the use of these strate- gies in the eight situations and the two settings (same-gender and mixed-gender) is presented in Table 9. Discussion This section examines the main findings in the context of the existing literature. The findings reveal a significant impact of both the socio-cultural and the cognitive-biological aspects of culture on Jordanians’ communicative behaviour. The data show that the interaction among gender and these factors exerts a significant influence on the type and frequency of strategies for communicating gratitude and provides the basis for the follow- ing conclusions: 1) Women perceive the communication of appreciation and gratitude as more important than men do. 2) Although both men and women have access to the same resources for expressing gratitude, the strategies that they use differ systematically. 3) The gratitude style of women and men varies, depending on the gender of the addressee and some features of the socio- situational context, in particular: the social formality of the si- tuation, social status and the amount of imposition presented by the favour on the favour giver. Women Perceive the Communication of Appreciation and Gratitude as More Important than Men Do Based on the analysis of the strategies and their frequencies in all eight situations, women appear to express gratitude more than men do. They appear to use more polite strategies, repeti- tive forms and intensifiers (really, very, too) and they express gratitude in more elaborate ways than men do, which suggests that women feel comparatively strongly the need to appear polite to others. This finding is in line with those of other researchers who observe that women are more sensitive to being polite than men, utilizing more politeness strategies (Gudonog & Jing, 2005; Froh et al., 2009). This is consistent with Lakoff’s (1975) assumption that women are more polite and conscious of (the need to avoid) hurting others, soft-spoken and nonaggressive, while men tend to be direct and assertive, due to power ine- quality in their linguistic and cultural worlds. The frequency of men’s use of gratitude expressions is com- paratively low, which could be explained by biological and cultural differences between men and women, with dominance being more important to men, so any act of expressing gratitude could threaten their masculinity and power (Baron-Cohen, 2003). This could be related to the claim that the communication of gratitude is not intrinsically face-threatening, but is likely to be perceived as face-threatening if it matters to the person to be dominant and assert power over the interlocutor, especially in non-egalitarian contexts (as argued in Al-Khawaldeh & Žegarac, 2013a). According to Baron-Cohen (2003), dominance hierarchy reflects men’s lower orientation towards empathy and higher orientation towards systemising skills and practices. Our find- ings support previous results which show that men are less like- ly to feel and express gratitude, tending to make more critical evaluations. This tendency supports Kashdan et al.’s (2009) ob- servation that men appear to view appreciation as challenging and onerous, preferring to evade feelings of indebtedness. This also suggests that, while most women enjoy talking in order to establish and manage social relationships, men are more ori- ented towards communication aimed at conveying information (i.e. propositional conceptual representations). In other words, women tend to value more the relational and men tend to value more the transactional function of social interaction. Our find- ings are also consistent with the views of Tannen (1990), Basow and Rubenfeld (2003), and Wood (2002) that women and men have different assumptions about talk and friendly conversa- tion. Although Both Men and Women Have Access to the Same Resources for Communicating Gratitude, the Strategies They Use Differ Systematically The strategies men and women use to convey gratitude differ systematically. This might be a consequence of gender related differences in perceptions of the degree of politeness, the weighti- ness of social familiarly, the weightiness of status and the sig- nificance of the favour. People choose to use certain strategies to show how much effort they to put into face redress, and in this way communicate (more or less indirectly) how much im- portance they attach to face in the immediate situation.  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 276 Table 9. Overview of strategies used in the linguistic communication of gratitude. Situation 1 Situation 2 Situation 3 Situation 4 Situation 5 Situation 6 Situation 7 Situation 8 W M W M W M W M W M W M W M W M Strategy S m s m s m s m s m S m s m s m s m s m sm s m s m s m s m sm 1 a b c d 2 a. b 3 a b c 4 a b c 5 a b c d e 6 a b c d e 7 a b c d e 8 a b c d 9 a b  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 277 Some interesting insights into the relation between gender and situation can be gained by considering the use of the ob- served strategies for communicating gratitude in relation to the participants’ gender (same-gender vs. mixed-gender talk) and the socio-situational settings described in the scenarios. The distinctive characteristics of gender-related gratitude behaviour are easier to identify for those strategies which are specific to particular situations. Types of Strategies for Communicating Gratitude Used Exclusively by Women/Men in Same-Gender Settings It seems remarkable that both genders show exclusive pref- erence for using certain gratitude strategies in same-gender set- tings. The number of gratitude strategies used by women is greater than that of men, especially in same-gender interaction. Three such strategies were found in same-gender talk: hugging (situation 1), establishing a relationship for the future (situation 2, situation 4 and situation 8) and self-criticism (situation 4). The sole use of hugging (a strategy which is not strictly speak- ing linguistic, but accompanies linguistic acts of communicat- ing gratitude) and maintaining a relationship in communication between women is readily explained in terms of cultural norms of appropriate social interaction between women and men. Four strategies in our data are used exclusively by men: here statement (situation 1), handshaking (situations 1 and 2), mak- ing an invitation (situation 8) and small talk (situations 6 and 7). Each of these strategies was used in same gender interactions between men. This indicates men’s directness when dealing with men. This is also easily explained in terms of cultural norms where, due to religious and other socio-cultural norms, handshaking, invitation and initiating talk are avoided in mixed- gender interaction, as they are not socially acceptable. Men’s tendency to use small talk in same-gender settings is explained also by the hearer having gone beyond what might be described as his duty towards the speaker, so the small talk strategy is a means of acknowledging this by engaging in a more personal type of conversation and in this way showing gratitude implic- itly. Types of Gratitude Expression. Strategies Used Exclusively by Women and Men in Certain Gender-Based Settings The following eleven strategies used for expressing gratitude are observed across situations: thanking, expression of positive feelings, apology, acknowledging imposition, commenting on obligations, repayment, self-criticism, prayers, appreciation, and terms of address. Thanking The most striking of these strategies is (direct or simple) thanking. This strategy is used in all situations and settings ex- cept: situation 4 (women in same-gender setting), situation 5 (women in same-gender and mixed-gender settings) and situa- tion 6 (women in same-gender and mixed-gender settings). In situation 4 (“help with the computer situation”) women seem to prefer to express gratitude indirectly (though very strongly) to other women who have helped them by saying their gratitude is so great that they are not able to express it in words. The “in- ability to thank” strategy is also used by women in situation 6 (letter of reference sent by FedEx). This is consistent with the observation that situations 4 and 6 present the greatest degree of imposition on the thankee. So, these are the only situations where the thanker feels that any thanking expression is not sufficient. In situation 5 (“scholarship reference letter”) women do not thank directly in either same-gender or mixed-gender settings. The strategies they use in this situation are: small talk, terms of address, praying expressions, expressing appreciation, and expressing positive feeling(s). The use of these strategies may reflect women’s preference for relational rather than trans- actional talk in situations which are not very formal, but where the power-distance between the speaker and the hearer is suffi- cient to allow for more personal/relational talk without the risk of misinterpretation. In this situation, men use direct thanking, but they also use terms of address, expressing appreciation and [only in the same gender setting] apologies. In situation 5, men do not use “small talk”, and “praying expressions”. Expression of positive feelings Women’s high preference for using this strategy (including complimenting) was observed in six situations, whereas it was used by men only in situation 6 (“FedEx”). It seems reasonable to assume that complimenting is used to express a positive emotional response to the hearer for his/her valued favour, mi- nimise the degree of imposition, and reduce the social distance between the speaker and the hearer, which can be seen as a way to consolidate solidarity between the speaker and the hearer and, in this way, ease communication. Women use this strategy exclusively in the same-gender set- tings in three situations: “booking a holiday” (2), “restaurant bill” (3) and “help with the computer” (4). They also use it in same- gender and mixed-gender settings in three situations: “letter of reference” (5), “FedEx” (6) and “coursework extension” (7). This is probably best explained in terms of the relationship between the speaker and the hearer, which is informal in situations (2, 3 and 4) and very formal in situations (5, 6 and 7). While the ex- pression of positive feeling(s) towards the hearer in an informal situation allows for a range of interpretations (some of which the speaker would want to avoid conveying), in more formal situations the expression of positive feelings towards the hearer is less liable to misinterpretation and need not be avoided. This could also be explained on the assumption that there is a greater degree of expected help/assistance from men to women and between men; perhaps also a sense of mutual solidarity which presupposes positive feelings. This finding is in line with Her- bert (1989), Johnson and Roen (1992) and Coates (1998) whose findings show that women compliment more than men do and Migdadi (2003) who found that compliments were compara- tively frequent in same-gender social interaction in the Jordanian culture. The only situation where complimenting is found in all set- tings is the fellowship reference letter sent by FedEx (6). It seems reasonable to conclude that the expression of positive feelings is considered appropriate in this situation because the hearer’s help goes beyond what the speaker has asked for and shows a personal concern for the speaker’s best interests. The low frequency of men’s use of this strategy could indicate men’s unwillingness to express emotions which could be attributed to the vulnerability they may feel, and could also affect their per- ceptions of their social autonomy. Men tend to avoid making exaggerated compliments, especially to women, probably be- cause these would be perceived as insincere, and therefore, as flattery, which is generally not accepted in the Jordanian culture, as it transgresses social norms of behaviour and might be per- ceived as rude. Exaggerated compliments are likely to make the complimentee feel uneasy or embarrassed. Politeness is a mat- ter of degree, and determining the appropriate degree of polite-  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 278 ness by choosing the appropriate linguistic expression depends on the speaker’s and the hearer’s assessment of (mutual) obli- gations, and costs. As Hasnaa Alsurihi (personal communica- tion) has impressed on us, in Arabic cultures (including that of Jordan), these assessments are based mainly on the personal relationship between the interlocutors, rather than on their in- stitutionalised social roles, such as: colleague, student, teacher, service provider, which are more important in Western cultures. If this generalisation, which cannot be explored here in more detail, is broadly correct, it points to a promising direction for further research. The “small talk” strategy is also observed in particular set- tings. In situations 1 (“borrowing class notes”) and 3 (“restau- rant bill”) it is used only by women in same-gender interaction; in situation 2 (“booking a hotel”) it is used by women and men in same-gender interactions; in situation 5 (“scholarship refer- ence letter”) by women in both same-gender and mixed-gender interaction and in situation 6 (“FedEx”) in all settings except men in mixed-gender interaction. Small talk is used for estab- lishing and maintaining positive social rapport between people. But why is engaging in small talk appropriate in the situations where it has been observed? Why is small talk initiated by wo- men in more situations than it is by men? A person who has borrowed some class notes may engage in small talk to convey the impression that she is not merely a user, that she asked the hearer to lend her the notes because she considers her a friend, so small talk appears to be a positive politeness strategy (“we en- gage in small talk, therefore we are friends”). It may well be that in some situations (such as 1 and 3) women would not initiate small talk with men, because this could easily be misin- terpreted due to particular cultural norms about the appropriate psychological and physical distance between women and men, which cannot be discussed here. Men do not initiate small talk with women in these situations possibly for the same reasons, while they do not engage in small talk with other men because the favour is not particularly big and mutual solidarity between men is strongly expected. Holiday is a good small talk topic, so men engage in it in same-gender interactions. In situation 5 (“letter of reference”) the social distance between the speaker and the hearer is considerable, but the hearer has evidently done far more for the speaker than the speaker was entitled to expect. In this situation, small talk affirms the speaker’s implicit ac- ceptance of the hearer’s friendly action. Essentially the same explanation for small talk could be given for its use in situation 6 (“FedEx”). Apology Apology is also found to serve the pragmatic function of ex- pressing gratitude. The two expressions are similar in that they imply indebtedness, as gratitude is expressed to show the speaker’s indebtedness for benefiting from the hearer’s actions, and apol- ogy is expressed to show the speaker’s indebtedness for the im- position incurred by the hearer. That is why apologies and ex- pressions of gratitude involve recognition of imposition. Our data shows that apologies are more frequent for conveying grati- tude indirectly in same-gender conversations between women than in same-gender conversations between men. However, this strategy is mainly used by men in the mixed-gender setting. Women use it in the mixed-gender setting only in the highest degree of imposition situation and mainly when dealing with high status individuals (situation 7, “asking the lecturer for as- signment extension”). This could be explained by the fact that male-male apologies could be attributed to men’s perception of apologizing as likely to make their relationship more formal. This could also indicate that they view it as a face threatening act. Men’s use of apology in mixed-gender settings could also be related to the socio-cultural perception and representation of women as more vulnerable than men. Through intensifying apologies in conversation with women, men aim to behave formally, trying to show that the imposition was unintentional. They communicate indirectly the sincere intention to mitigate the imposition. This could imply covertly that they regard women as less powerful. In situation 1 (borrowing class notes) men’s apologies in mixed-gender conversation could be explained in terms of the cultural expectation that men should not depend on women for help. It could also be explained as due to social restrictions on mixed-gender interaction. Apologising could serve to show that they are aware of and abide by generally accepted social rules. It is also interesting that in situation 5 (“scholarship reference letter”) only men used apology and they did so only in the mixed-gender setting. Again, this could be due to the sense of face loss at depending on a woman for assistance in a situation where the position of competence, power and authority is tradi- tionally reserved for men. As a way to convey an apology, the strategy “expressing em- barrassment” is found in same-gender settings, as well as in mixed-gender settings in situation 6. In the mixed-ender setting this strategy is used by men to emphasise that the imposition on the hearer caused by the favour was not intended. This may be due to the expectation that men are self-sufficient and that by going out of her way to help a man the female lecturer exposed the man’s lack of self-sufficiency. In other words, by helping a man a woman threatens his positive face. Women showed a disposition to present well-organised apolo- gies to their female counterparts. In situation 2 (“booking a ho- tel”) women apologise in the same-gender setting. In this situa- tion, they would not apologise to a man, presumably because a male colleague would be expected to (offer to) help in this situation. A man would not apologise in either the same-gender or the mixed-gender setting. Men are generally expected to provide comparatively big support to each other and women are expected to provide comparatively generous assistance to col- leagues working in the same office. In situation 3 (“restaurant bill”) women apologise in the same-gender setting, presumably because it is not socially accepted that a woman should pay the bill for the mixed group. In this situation, men apologise in the mixed-gender setting because it is socially expected that a man would pay for the dinner. Woman to woman apologies could be interpreted as communicating indirectly that the imposition caused by doing the favour was not intended, and could help establish and/or maintain positive rapport between the speaker and the hearer. This shows that, on the whole, women are more in- debted and sensitive to possibly face-threatening speech and use negative politeness in conversation with other women to mitigate the face threat. The prevalence of negative politeness in talk between women is surprising, as initial research indi- cates that they use mainly positive politeness strategies in this setting. For example, women tend to apologise and recognise the imposition put on other women, in addition to expressing their appreciation and positive feelings. This shows that there is no sharp dividing line between women’s world and men’s world, where the former receive positive politeness and the latter re- ceive negative politeness. Rather, the ways women and men communicate gratitude reflect their assessments of the weighti-  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 279 ness of several social and contextual variables (such as: social status, social familiarity and degree of imposition) in the con- text of the socio-cultural norms relevant to particular socio-si- tuational settings. In Situation 4 (help with the computer given by a person the speaker does not know very well) women apologise in both same-gender and mixed-gender settings, whereas men do so explicitly only in mixed-gender settings. This seems to point to a greater degree of socio-culturally expected mutual support be- tween men, who, if they assess the received favour as very major, offer some sort of repayment. This is not surprising if, as we are inclined to assume, women are generally more sensitive to imposing on others, while men expect other men to help. Men are expected to be more self-sufficient and competent in IT than women, so might lose face when depending on women in this situation. Women’s apologies to men in this situation could also be attributed to their perception that it is highly un- usual and impolite for a woman to intrude (and greatly impose) on a strange man. In situation 6 (“FedEx”) apology is used by men only in mixed-gender interaction. This is what we would expect if women tend to feel more indebted to men for acts of kindness which go beyond their duties (as men are perceived as less altruistic than women), whereas men would apologise to women in this situation, for reasons of face loss: the situation makes it evident that the man is very dependent on the woman’s support, which threatens his positive face. Situation 7 (“exten- sion for coursework deadline”) is interesting in that apology is not used by women only in all settings. This could be because women and men were predisposed to exaggerate their apologies particularly with a high degree of obligation and, in the case of men, even when the person deserving gratitude was of the op- posite gender. Women’s use of apologies in situation 7 may be due to their sensitivity to imposing on a higher status person. This might be further explained in terms of the culture-specific assumption that women have lesser rights to impose (by mak- ing requests) on individuals who are in a position of power. However, imposition on women was recognised and apolo- gised significantly more often than imposition on men. This finding also suggests that men and women perceive the kind of imposition that should trigger the communication of gratitude somewhat differently, which is reflected in their linguistic be- haviour. What is seen as a great favour by a woman, does not essentially count as a great favour for a man, as in situation 2(“booking a hotel”) and situation 5 (“scholarship reference letter”). Jordanian women seem to be more concerned about time, effort and money, while Jordanian men are more inclined to acknowledge impositions relatively elaborately only if they are incurred by women. The low frequency of female-male use of apology for any imposition caused could be linked to men’s unwillingness to hear women’s apologies as a part of men’s politeness and re- spect for women. This was also pointed out by several female participants who said that in general, they could not greatly apologise to male friends, as their apologies would not be ac- cepted. It is also out of politeness and respect for women that men are generally expected to downgrade the significance of women’s apologies even if these are deserved. This is consis- tent with the assumption that men do not consider women to be in a position to affect them in such a way that they might need to apologise to them. In other words, by not accepting that the apology of a woman is deserved a man implies (covertly) that his position of strength and dominance is such that it could not be challenged by the actions of a woman. This supports Al- Adaileh’s (2007) observation that it is impolite and uncommon for Jordanian men to allow women to apologise to them. Acknowledging imposition The “acknowledging imposition” strategy is found in many settings. In situation 4 (“help with the computer”) it is not ob- served only in same-gender conversation between women. The use of this strategy by women, also in both settings, supports the observation made earlier that women are generally more sensitive to imposing on others than men, who strongly expect other men to offer and give help. A man might lose face when depending on a woman in this situation. Women’s recognition of imposition on men could also be attributed to their percep- tion that it is impolite for a woman to intrude and make an im- position on a strange man. This could help them draw formal boundaries in their relationships. In situation 3 (“restaurant bill”) this strategy is used by women in same-gender and mixed-gender conversations. This can easily be explained in terms of a social convention that men, rather than women, should pay the res- taurant bill in the situation described. (An interesting question raised by this strategy is why it occurred once in same-gender conversation between men?) It seems plausible to argue that men have a stronger sense of their personal autonomy and are less likely to negotiate from a position of personal obligation. The use of this strategy by men exclusively in mixed-gender interaction is likely to help them keep their social relation- ships appropriately formal. This could also indicate that they view it as a face threatening act when it is addressed to men by men, presumably because it suggests that by accepting the im- position the hearer has lost his personal autonomy, possibly also because the speaker may be seen as relinquishing his own autonomy by acknowledging indirectly his obligation to return the favour to the hearer. Equally important is the use of the “minimising the need for a favour” strategy, observed in situations 5 (“scholarship refer- ence letter”), 6 (“FedEx”) and 7 (“extension for coursework deadline”). This strategy is used by women in both same-gen- der and mixed-gender conversations. In situation 4 (“help with the computer”) it is used by women in same-gender interaction only. The speaker who opts for this strategy may seem to be trying to avoid taking responsibility for the imposition on the hearer (i.e. the favour giver) by communicating both that the favour is needed but not to the point that the hearer should put himself or herself out for the speaker. However, it should be understood as an expression used to mitigate the severity of the imposition, as well as implicating that the imposition is not de- liberate and could not have been avoided as it was beyond the speaker’s control. This could lead the favour giver to accept the imposition and feel positive about the favour. It may also indi- cate that women generally feel more indebted for received fa- vours than men and are more sensitive to possibly face-threat- ening speech, using this strategy even in same-gender settings where they feel generally more relaxed with their interlocutors. The situations in which this strategy is used suggest that it could be perceived as socially acceptable and preferred only in formal situations involving a high degree of imposition. Commenting on obligations In situation 7 (“extension for coursework deadline”), the “com- menting on obligations” strategy is used by women only in the same-gender setting. However, the strategy “non-existent obli- gation” is used by women in both same-gender and mixed-gen- der settings in situation 6 (“FedEx”). It seems plausible to as-  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 280 sume that in the “extension for coursework deadline” situation asking a favour from a female lecturer leads the female student feeling more comfortable about commenting in personal terms on her obligations than when the lecturer is a man, whereas sending a reference letter for a scholarship via FedEx is so far outside a lecturer’s normal duties that a student would not expect it at all. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that in this situation com- menting on a sense of personal obligation is equally appropriate in both same-gender and mixed-gender settings. In situation 7 (“extension for coursework deadline”), the context in which ob- servations about personal obligation are made includes assump- tions about the speaker asking for compassionate treatment, whereas in situation 5 (“scholarship reference letter”) the spea- ker’s obligations are talked about in the context of assumptions about his/her personal aspirations. In this context, assumptions about the greater disposition of the lecturer for showing empa- thy with the speaker are less relevant, so evidence of such em- pathy (presented by the lecturer’s decision to personally send the letter by FedEx) is more relevant (as it is comparatively unexpected). Repayment In situations 2 (“booking a holiday”) and 3 (“restaurant bill”), this strategy is used only in same-gender interactions (both be- tween women and between men). In situations 4 (“help with the computer”) and 6 (“FedEx”) the only setting in which repay- ment is not offered by women is mixed-gender interaction. In situation 6 (“FedEx”), men use the “repayment” strategy in the same-gender setting, which they do not do in situation 5 (“scholarship reference letter”). This might be explained on the assumption that that men are expected to put themselves out more to help women in such situations, so repayment is not owed. This suggests that in these situations repayments would not be appropriate in mixed-gen- der interactions. The infrequency of this strategy in mixed-gen- der interaction could be due to socio-cultural restrictions. Mas- culinity is socially constructed as involving a position of power in relation to women, while femininity is socially constructed as involving dependence on men. It follows from this that a woman should not owe repayment to the more powerful man on whom she depends. By offering to repay a man she would be putting herself implicitly in a relatively equal position. The offer of repayment by a woman in mixed-gender interaction could also be interpreted as an intention to establish and main- tain close social relationships which could be considered as socially inappropriate. It is considered polite for a man to offer repayment to a woman and to minimise the need for repayment when it is offered by a woman. There is some evidence that men and women view gratitude differently. While men tend to y offer mostly material repay- ment (e.g. “. ”, “I would be happier if you share a meal with us at home today.”), women tend to offer incorporeal repayment (e.g. “. ”, “I hope I will be able to serve you in happy occasions.”) espe- cially with men. Self-criticism The high frequency of the expression of “self-criticism” strat- egy (used exclusively when talking to women by both women and men) could be accounted for by the fact that it helps the speaker to communicate strongly her or his sympathy with the favour giver in a high imposition situation, such as “help with the computer” (situation 4). Self-blame and self-criticism also make it possible to communicate strongly, though indirectly, the importance the speaker places on a harmonious relationship with the hearer. The exclusive use of self-reprimanding by wo- men only in same-gender settings is best explained in terms of “face-threat”. In a situation in which the need for help may have been due to the speaker’s lack of technical knowledge of computing, an admission of lack of competence could be seen as a threat to the speaker’s positive face. However, contextual assumptions about the expected level of technical competence of men and women vary across cultures. In a traditional culture like Jordan women are not expected to be competent in the technical sphere, whereas men are. It follows from this that a man who admits to being less technically competent than is so- cially desirable threatens his positive face, whereas a woman does not (because she is not expected to be competent in the technical sphere). Prayers In situation 1 (“class notes”), this strategy is used only by women in the same-gender setting. In situation 2 (“booking a holiday”) it is used by women in same-gender settings, but also by men in mixed-gender settings. In situations 3 (“restaurant bill”), 5 (“scholarship reference letter”) and 6 (“FedEx”), it is used by women in same-gender and mixed-gender settings. However, in situation 4 (“help with the computer”) this strategy is used only by men in same-gender settings. In situation 7 (“extension for coursework deadline”) it is used only by men in the mixed-gender setting. Bearing in mind that prayers are never perceived as improper, their use or non-use is mainly driven by how much affection the speaker has for the hearer and how showing affection is socially perceived. Women may use prayers more than men because they are more emotional, but the display of emotions by a man could be interpreted as a sign of weakness, because strength and self-control are central to the socially constructed ideal of masculinity. Appreciation The “appreciation” strategy is observed in 12 settings. It is used in a mixed-setting in situations (2) (“booking a hotel’),4 (“help with the computer’), (7) (“extension for coursework deadline’) and in all settings in situations 5 (“scholarship refer- ence letter’) and 6 (“FedEx”). In these situations the degree of formality between the participants is high. The data suggests that appreciation is usually communicated explicitly when ex- pressing gratitude for actions which go beyond what could have been reasonably expected of the hearer to do for the speaker. In situation 2 (“booking a hotel”) appreciation is expressed explic- itly by men and women in mixed-gender settings. A possible explanation for this is that women are generally more apprecia- tive, while men are prompted to express gratitude to women be- cause by accepting their help, they find their positive face (the need for self-sufficiency) under threat. Appreciation is expressed in mixed-gender settings in situations 2 (“booking a holiday”) and 4 (“help with the computer”). In mixed gender settings this strategy is used alongside other strategies which express grati- tude more strongly. As showing appreciation is more relevant when the favour given was not expected or was not even asked for, the use of this strategy in these socio-situational settings suggests that the speaker, by expressing appreciation, intends to communicate that the favour given was all the more valued because it was not expected. In case the favour was not asked for, the speaker, by showing appreciation, reassures the hearer that the speaker recognises the hearer’s actions as desirable to the speaker.  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 281 Terms of address This strategy is observed in quite a few situational settings. In situation 1 (where the speaker is expressing gratitude to a close friend for lending him/her his/her class notes) this strat- egy is used by women in the same-gender interaction and men in mixed-gender interaction. The use of this strategy by women in same-gender setting means more intimacy such as “my eyes”, whereas its use by men in mixed-gender interaction indicates respect and helps the hearer make the interaction more formal and show respect (e.g. “” “my sister”). In situation 2 (ex- pressing gratitude to a colleague the speaker does not know very well for helping with booking a hotel) the “terms of ad- dress” strategy is used in all situational settings except in same- gender conversation between men. This could be explained on the assumption that social expectations about mutual help be- tween male colleagues are very high due to a comparatively high degree of solidarity between men. The use of this strategy in all other settings in situation 2 seems to point to the role of dis- tance between the participants (who are colleagues, but who do not know each other well). This conclusion is supported by the data relating to situations 6 (letter of reference from a profes- sional person that the speaker knows very well) and 8 (help in the street from a person the speaker does not know very well). Our findings show clearly that the “terms of address” strategy signifies intimacy in more familiar same-gender settings and deference in more formal and mixed-gender settings. The Gratitude Style of Women and Men Varies, Depending on the Gender of the Addressee and Some Features of the Socio-Situational Context, in Particular: The Social Formality of the Situation, Social Status and the Amount of Imposition Presented by the Favour on the Favour Giver It appears that women, rather than men, give considerable weight to the level of familiarity with the hearer when express- ing gratitude. Women prefer not to express gratitude to men who are strangers. In general, they use various strategies to con- vey gratitude to men. They find making decisions on the best way to express gratitude in the same-gender setting much easier than in the mixed-gender setting. For women, the most impor- tant aspect of making strategic decisions on how to communi- cate gratitude seems to be the degree of familiarity with the hearer. For example, in the “booking a hotel” situation they do not readily initiate small talk, because they are not familiar with the hearer and also because the formality of the situation is rather high. Showing interest in establishing a future relation- ship in the “giving directions” situation (situation 8) is definite- ly regarded as impolite and considered ill-mannered. In view of these observations, it is not surprising that Jordanian women tend to employ different politeness strategies when expressing gratitude to relatively close friends who are members of their “in-group” and when conveying gratitude to comparative strang- ers, who are categorised as “out-group” individuals. Both genders showed significant awareness of using appro- priate politeness strategies, especially when addressing higher status individuals. Compared to men, women appear to be more sensitive to the social status differential between the interlocu- tors than to gender differences, especially in communication with higher status persons. Our informants explained the use of similar strategies for expressing gratitude in situations 5 (“school- arship reference letter”), 6 (“FedEx”) and 7 (“extension for coursework deadline”) as motivated by the formality of the situation and their personal relationship with the hearer, stating that they viewed their teachers as parent figures. Men placed greater emphasis on the need to express gratitude to women than to men. They reported that male university lecturers tend to be more formal with them than with women, so they tend to use direct polite formal ways of expressing their gratitude to male lecturers. Moreover, men appeared to be less concerned about social status and less self-expressive than women in such situations. For example, women reported using more strategies than men, such as the title “Professor” and replacing the second person pronoun singular “you” “ ” with the honorific second person plural “you” “ ” when talking with a person of significantly higher status. This is consistent with Liao and Brenahan’s (1996: p. 709) observation that “women are more status sensitive than men”. Another explanation might be that in some socio-cultural set- tings women are expected to acknowledge explicitly their lower status, if the status differential between the participants is high. A prediction which follows from both explanations is that women of lower status will employ more politeness strategies than men of lower status in situations where the status different- tial between the participants is high. The degree of imposition presented by the favour being thanked for seems to be an overriding factor in the choice of strategy for conveying gratitude. This could explain two findings. First, people seem to express gratitude using different strategies de- pending on whether the imposition presented by doing the fa- vour is low or high. Second, the degree of imposition might be the cause of variation in the appropriate degree of politeness. Women are expected to be more polite than men. In general, they also seem to acknowledge the high degree of imposition on the hearer who has done the favour by employing a variety of strategies. This suggests that the socially-accepted attitude is that the same favour presents a greater imposition if it has been done for the benefit of a woman than for the benefit of a man. Women’s high sensitivity toward any imposition caused to others could be an additional reason for their tendency to express ap- preciation often. It seems that in the same type of situation the distance between the participants in the same-gender setting is lower if they are men than in the mixed-gender setting. For this reason women tend to use more linguistic politeness in ex- pressing gratitude to men than men do in the same situation when talking to other men. Men also tend to perceive situations as less formal and the status differential as smaller than women do in the same situation. These observations lead to the general conclusion that women and men assign different values to the variables which play a causal role in the choice of strategy for communicating gratitude and the ways in which these strategies are used. The hearer’s gender also seems to have a considerable influ- ence on the communication of gratitude. Women tend to ex- press gratitude to women more than they do to men, while men are inclined to express gratitude to women more than to men. While women seem to be comparatively highly deferential and less communicative when conveying gratitude to men, they are very supportive, empathic and warm when conveying gratitude to women. The various expressions of gratitude used by women outnumber those used by men in same-gender interactions by a bigger margin than in mixed-gender interaction. The findings also show that women vary their gratitude strategies according  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 282 to the gender of the addressee to a greater extent than men do. They are more responsive than men to subtle differences in the social relationship between the interlocutors which affect the communication of gratitude. This could be a reflection of gen- der-inequality as an intrinsic feature of the Jordanian culture (which used to be even greater than it is today), which is hardly surprising as talk is reflexively associated with the socio-cul- tural and contextual environment in which it occurs (Ochs & Schieffelin, 1979; Ochs, 1988; Duranti & Goodwin, 1992; Potter, 1996). In the past, women were expected to act according to very strict rules as they had lower social status. This tradition lives on in patterns of communication. Women are still expect- ed not to engage in conversation with men to whom they are not related, especially with strangers. Although traditional cul- ture has changed in many ways, the old Jordanian ideology and stereotypes still permeate every socio-situational setting (the street, the workplace) and exert some influence on cross-gender communication. A significant factor in perpetuating the differ- ences in the communication of gratitude by men and women in Jordan is education, which plays an important role in the trans- mission of traditional cultural values and norms from one gen- eration to the next. Boys and girls are taught to behave like boys and girls. What Cameron (1995) calls “verbal hygiene” is different for men and women.While Jordanian men have some considerable freedom when selecting gratitude strategies, Jor- danian women are taught rather strictly prescribed socially ap- propriate ways of talking (see Cameron (2007) for a more de- tailed discussion of this point in relation to other cultures). Conclusion The investigation of the relation between language and gen- der in the linguistic communication of gratitude in a particular culture can be thought of as faced with three major tasks: col- lecting the data, describing the data and explaining the data. The study presented in this paper has addressed each of these tasks in ways which, despite some serious limitations, lead to interesting insights and suggest directions for further research. The collection of the data was systematic as it involved re- sponding to a set of scenarios. The main shortcoming of this approach is that the data is not naturally occurring. However, the description of the data led to conclusions about the strate- gies used to express gratitude and about the ways these are re- lated to gender. These conclusions could (and, we believe, should) inform the design of further studies based on observa- tions of naturally occurring linguistic behaviour. For example, it would be possible to check whether the strategies we have identified are actually used by people in the culture of Jordan and whether there are systematic differences between the cul- ture of Jordan and other cultures in the ways gratitude is ex- pressed. At the more explanatory level, it would be worth ob- serving the communication of gratitude across a range of situa- tions which vary in subtle respects and in this way check the tentative and sketchy explanations that we have proposed. In particular, we have argued that the relation between gender and the communication of gratitude could be explained in terms of the interaction between a handful of variables: face concerns, degree of imposition, and the socio-cultural values and attitudes which underlie power, distance and status differential. Clearly, this claim could be tested as it gives rise to various predictions which could inform the collection of naturally occurring data. Another interesting challenge might be to contrast the culture of Jordan with other proximate and more distant cultures. REFERENCES Al-Adaileh, B. A. M. (2007). The speech act of apology: A linguistic exploration of politeness orientation in British and Jordanian cul- ture. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Leeds: University of Leeds. Al-Khawaldeh, N., & Žegarac, V. (2013a). Cross-cultural variation of politeness orientation & speech act perception. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 2, 231-239. Al-Khawaldeh, N., & Žegarac, V. (2013b). A linguistic exploration of politeness orientation in Jordanian and English culture: A compara- tive cross-cultural pragmatic study. 46th Annual Meeting of the Brit- ish Association of Applied Linguistics (BAAL), Edinburgh. Baron-Cohen, S. (2003). The essential difference: The truth about the male and female brain. Basic books. Basow, S. A., & Rubenfeld, K. (2003). Troubles talk: Effects of gender and gender-typing. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 48, 183-187. Brown, P. (1998). How and why are women more polite: Some evi- dence from a Mayan community. In: C. Jennifer (Ed.), Language and gender: A reader (pp. 144-162). Oxford, England: Blackwell. Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in lan- guage usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cameron, D. (2007). The myth of mars and venus: Do men and women really speak different languages? Oxford: OUP. Coates, J. (1998). Women, men, and language: A sociolinguistic ac- count of gender differences in language. Blackwell Publishing. Crawford, M. (1995). Talking difference: On gender and language. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Duranti, A., & Goodwin, C. (1992). Rethinking context: Language as an interactive phenomenon. In E. Ochs (Ed.), Culture and language development: Language acquisition and language socialization in a Samoan village. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and sub- jective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differenc- es. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 633-650. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006 Gray, J. (2004). Men are from mars, women are from Venus: The clas- sic guide to understanding the opposite sex. Harper Paperbacks. Guodong, L., & Jing, H. (2005). A contrastive study on disagreement strategies for politeness between American English and Mandarin Chinese. Asian EFL Journal, 7, 1-12. Herbert, K. (1989). Sex-based differences in compliment behaviour. Language in Society, 19, 201-224. Johnson, M., & Roen, J. (1992). Complimenting and involvement in peer review: Gender variation. Language in Society, 21, 27-57. doi:10.1017/S0047404500015025 Kashdan, T. B., Mishra, A., Breen, W. E., & Froh, J. J. (2009). Gender differences in gratitude: Examining appraisals, narratives, the will- ingness to express emotions, and changes in psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 77, 691-730. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00562.x Lakoff, R. (1973). The logic of politeness: Or, minding your p’s and q’s. In C. Corum, T. Cedric Smith-Stark, & A. Weiser (Eds.), Papers from the 9th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Chicago Linguistic Society, 292-305. Lakoff, R. (1975). Language and women’s place. New York, NY: Har- per and Row. Levant, R. F., & Kopecky, G. (1995). Masculinity, reconstructed. New York: Dutton. Liao, C. C., & Bresnahan, M. I. (1996). A contrastive pragmatics study on American English and Mandarin refusal strategies. Language Sciences, 18, 703-727. doi:10.1016/S0388-0001(96)00043-5 Migdadi, F. H. (2003). Complimenting in Jordanian Arabic: A socio- pragmatic analysis. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Muncie, IN: Ball State University. Ochs, E. (1988). Culture and language development: Language acqui- sition and language socialization in a Samoan village. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ochs, E., & Schieffelin, B. (1979). Developmental pragmatics. New  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 283 York: Academic Press. Pan, Y. (2000). Politeness in Chinese face-to-face interaction. New York City, NY: Ablex Publishing Corporation. Pilkington, J. (1998). “Don’t try and make out that I’m nice!” The dif- ferent strategies women and men use when gossiping. In: C. Jennifer (Ed.), Language and gender: A reader (pp. 254-269). Blackwell, Ox- ford. Potter, J. (1996). Representing reality: Discourse, rhetoric and social construction. London: Sage. Solomon, R. C. (1995). The cross-cultural comparison of emotion. In J. Marks, & R. T. Ames (Eds.), Emotions in Asian thought (pp. 253- 294). Albany: State University of New York Press. Spolsky, B. (1998). Sociolinguistics. Oxford introductions to language study. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand. London: Virago. Tannen, D. (1994). Talking from 9 to 5. Women and men in the work- place: Language, sex and power. New York: Avon Books. Trudgill, P. (1974). The social differentiation of English in Norwich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wood, J. (2002). A critical response to John Gray’s Mars and Venus portrayals of men and women. Southern Communication Journal, 67, 201-210. doi:10.1080/10417940209373229  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 284 Appendix A Thanking A. Using the Arabic word “shukran” “thank” only(bare thanking). Arabic “ ” “ukra:n lak jazi:lan”, “Thank you very much.” (Recommendation letter) “ ” “>∫kuruk min kul >amaq qalbee.”, “I thank you from the bottom of my heart heart.” (booking a hotel) B. Expressing thanking and stating the favour Arabic "”, “∫ukran lak kathi:ran ʕla xidmatik”, “Thank you very much for your service.” (Computer) " ” “∫ukran dazi:lan li taqdi:rik wadʕi: Alxas”, “Thanks very much for your recognition of my own situation.” (Paper extension) C. Expressing thanking and mentioning the imposition caused by the favour Arabic “ ”, “∫ukran lak jazi:lan ʕala alwaqit alidˤafi: fi: kitabat risalat altawsi:ah w<r&ha ʕan tˤari: fi:di:ks”, “Thank you very much for the extra time for writing the reference letter and sending it by FedEx” (FedEx) " ", “ukran lak kathi:ran la alduhid alaði: baðaltahu fi: tasli:h alaswb”, “Many thanks for the effort you spent in fixing my computer” (Computer) Expressing an inability to express thanking Arabic “ ” “La >rif ki:f ‘kuruk aq alukr”, “I do not know how to thank you right” or “I can’t thank you enough” (Recommendation letter) " ” “na haqan adiz an ukrik ala aldwa aldami:lah”, “I am really unable to thank you for this lovely invitation”. (In a restaurant) Appreciation A. Expressing bare appreciation Arabic " “&qadir lak alian”, “I highly appreciate for you” (Computer) “ ” “&qadir lak kathi:ran”, “I greatly appreciate it for you” (Recommendation letter) B. Expressing appreciation and explicitly stating the favour. Arabic " " “&qadir lak alian marwfak”, “I highly appreciate your favour”.(Booking a hotel) " " “&qadir lakdazi:lan musa: datuk wa xidmatuk”, “I appreciate your help and service very much”(Recommendation letter) C. Expressing appreciation and mentioning the imposition caused by the favour Arabic "” “&qadir lak musa: datuk la alram min kwnik mawl” “I appreciate your help though you were busy”, “I appreciate your help though you were busy” (Computer) " ", “&qadir lak madhudak litasli:h alhaswb alxas bi:” I appreciate our efforts for fixing my computer”, “I appreciate our efforts for fixing my computer” (Computer) D. Appreciation and stating the reason Arabic " “&qadir lak musa: adatuk alati: kuntu biad masah laha”, “I appreciate your help which I badly needed”(FedEx) Expressing positive feelings A. Expressing a positive reaction to the favour giver/(compliment): Arabic “ ” “mamnwn didan litawnak”, “Iam very grateful for your cooperation”(computer) “ ” “faqad amartani:bilutfak w birufak”, “you overwhelmed me by your kindness and favour” (FedEx) B. Expressing a positive reaction to favour giver on the object of the favour/ (compliment). Arabic  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 285 “ ” “aqan <na mula:aðatuk wa: dia w mufi:dah”, “really your notes are clear and use- ful.” (Class notes) “ ” ‘kalimat risalat altwsi:ah ra’ah didan, “The recommendations letter’s words are extremely wonderful.” (Recommendation letter). C. Expressing a positive reaction to the outcome of the favour Arabic “ ” “ana mut’kd anaha satakwn musaadah kabi:rah <ða asalt ala almina”, “I’m sure it will be a big help if I get the fellowship” (FedEx) “ ” ‘laqad ashamt an urizah alamah ji:dah fi: <mtianati, “You contributed to me to get a good mark in my exams.” (Paper extension) D. Expressing an inability to articulate positive deep feelings Arabic “ ” “adz an altbi:r an farati”.(FedEx) ” la ‘rif maða aqwl “I do not know what to say to you” (Computer) “ ” “adz an altbi:r an <mtinani: tidah mrwfak” “I cannot express my gratitude for your favour” (Computer) Apology A. Expressing apology using apologizing words Arabic “ ” “ana asif” ,”I am sorry” (Direction) " " “taðir kai:ran”, “I apologise very much” (FedEx) B. Expressing apology using apologizing and stating the favour or the reason Arabic “ ” “wuðran marah uxrah ala at’xi:r” “and sorry once again for the delay” (Paper Extension) “ ” “taðiru an <xbarik mutaxiran”, “I am sorry for telling you late” (FedEx) C. Expressing apology using apologizing words and mentioning the imposition caused by the favour Arabic “ ” “uðran littilik an amalik”, “Sorry for disturbing you from your work” (Computer) " ” “ardu an tusamiani: ala >i: <rad sababtuh lak”, “I beg your pardon for any embarrassment I caused” (Paper extension) D. Expressing apology by expressing embarrassment Arabic “ ” “<nahu a} murid didan”, “It is a very embarrassing thing”(computer) “ ” “xdaltani: bi karamik” “you embarrassed us by your generosity”(FedEx) E. Criticizing or blaming oneself Arabic “ ” “makan j, dib alj, an atlubk an tusali alaswb”, “I should not have asked you to fix the computer” (Computer). “ ” “enha altati:”, “It is my mistake” (paper extention) Recognition of Imposition A. Acknowledging the imposition Arabic “ ” “>lam >nani >xaðt duz” kabi:r min waktak”, “I know that I have taken a lot of your time.” (FedEx) "” “>lam >nani: >ltuk mi:”, “I know that I busied you with me.” (booking a hotel) B. Acknowledging the imposition by stating the reason and the need for the favour. Arabic “ ” “wlaknani: la astani a lhaswb”, “I can’t dispense my computer” (Computer) “ ” “a rif maða kunt s>mal min dwnak”, “I don’t know what I would have done without you.” (Booking a hotel) C. Diminishing the need for the favour/the lack of necessity Arabic “ ” “ma ka:n j, dib alj, k >n tuzd nafsk”, “you should not have disturbed yourself.” (FedEx)  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 286 “, ” “lam j, akun liðalik >j, dai:”, “There was no need for that” (In a Restaurant) D. Stating interlocutor’s non-existent imposition Arabic “ ” “lam >kun >nwi: <zdk”, “Thank you but I did not intend to disturb you.”(FedEx) “ ” “lam >kun >lam nha satstriq zamanan tawi:lan”, “I did not know it would take a long time.”(Computer). E. Recognition of obligation “ ” “Kan jdjib an ugadim waragt alba fi: almawid almuadad”, “I should have submitted the course work on time.”(Paper extension) Arabic Recongtion f non existent obligation ” ” “Ana aalam an hatha lysa min wadebatik”, “I know that this is none of your your duties”.(FedEx) Offering repayment A. Offering or promising to reciprocate help, service, money, food Arabic “ ” “>dwk ala wali:mah”, “I am inviting you to a feast.” (FedEx) "” “<ða >radt >j, saj, min hunak f>na mustdun li dalbihi laki mahma kan”, “if you ever need anything from there, I am ready to bring it whatever it is.” (Booking a hotel) B. Indicating indebtedness Arabic “ ” “>na madi:nun lak biaj, ti”, “I owe you my life.” (FedEx) “ ” “>na madi:nun lak limusadatuk, “I am really indebted to you for your help.” (Computer) C. Promising future self-restraint or self-improvement and confirming interlocutor’s commitment Arabic “ ” “>widuk >n lan j, takrar ðalik >badn”, “I promise you this will not happen ever again.” (Paper Extension) “ ” “lan >nsa sani:uk haða ma aj,i:t”, “I will never ever forget your favor all my life”( FedEx). D. Indicating inability to repay enough Arabic “ ” “mahma nuqadim lak flan nufi:k haqk”, “What ever we do, we can not repay you enough” (FedEx) Others A. Here Statement Arabic “” “taffadal”, “Here you are!” (Class notes) “ ” “tafadal daftir mul‘Here is your notebook” B. Initiating a small talk Arabic “ ” “kai:ran ma >rak Dr. fi: ldamah”, “Many time I saw you doctor in the univer- sity.”(Direction) “ ” “>tmana >n >sul la lmnha”, “I wish I will get the scholarship.” (FexEx) C. Leave-taking Arabic “ ” “masawk si:d”, “good evening”(Booking a hotel) “ ”, “fi: >man llah “In God’s safety” (Direction) D. Expressing a desire (an intent to maintain a relationship) Arabic “ .” “j, arifuna >n natraf alj, k”, “I will be honoured to know you.”(Direction) “ ” “wlj, kun haða lmawqf bidaj, h li sadaqa mi:mah bj, nana” “Let this occasion be the beginning of warm friendship between us.” (Booking a hotel) E. Joking Arabic  N. N. AL-KHAWALDEH, V. ŽEGARAC Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 287 “ ” “haðih dari:bat alsuah”, “This is a tax for having friendship”. (In a restaurant) F. Prayers/Benediction Arabic “ ” “barak ,lah fi:k”, “May God bless you and give you a thousand of health” (Recommendation letter, FedEx) “ ” “j, dzi:k ,llah kul xj, r”, “May God reward you (well)” (In a restaurant)/ (FedEx) Alerters A. Attention getter Arabic “ا ” “salam alj, kum” “Hello” (Paper extension) “ ” ‘ma ’a:’ llah’, “God wills” (Computer) B. Stating the person’s name Arabic “” (kwks) (Cox) ” (smi) (smith) C. Stating terms of address/title Arabic “” “duktwr”, “Doctor” (Recommendation letter) “ “ustaði: l fadil”, “my moralist teacher” (FedEx) Nonverbal strategies A. Hugging Handshaking