Open Journal of Ophthalmology, 2013, 3, 76-86 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojoph.2013.33019 Published Online August 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojoph) Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa Joella Eldie Soatiana1, Marce-Amara Kpoghoumou2, Fatch W. Kalembo3, Huyi Zhen1 1Department of Ophthalmology, Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China; 2Depart- ment of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China; 3Department of Maternal and Child Health, Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Email: joellaeldie@yahoo.fr; kpogmarce@yahoo.fr; kalembofatch@yahoo.com;1012646376@qq.com Received April 13th, 2013; revised May 14th, 2013; accepted June 20th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Joella Eldie Soatiana et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Li- cense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Purpose: To determine the outcome of trabeculectomy in African countries. Design: This is a review of literature for trabeculectomy conducted in Africa from 2000 to December 2012. Methods: We conducted an electronic search from the following databases: PubMed, Science Direct, Google, and Google scholar websites for the articles of original stud- ies on trabeculectomy conducted in Africa. Results: A total of 109 articles, published from 2000 to December 2012 were retrieved. Only 12 articles met our inclusion criteria and were included in the study. The follow-up duration ranged from 6 months to 60 months. The post-trabeculectomy IOP range was 10 mmHg to 22 mmHg with rates varying from 61.8% to 90%. The visual acuity was unchanged among 19% to 30% of the participants in the last follow-up, and the improvement rate was 36% to 81.5% while those whose condition worsened ranged from 8.9% to 30.8%. The cup-disc ratio was ≤0.5 in 13% and ≥0.8 in 83% of the participants. The failure rate of the c/d ratio was 0.9 and it in- creased by 0.027 units. There was a follow-up of only one study on the visual field. Conclusion: Trabeculectomy with or without application of antimetabolite appears to be a good way to lowering the IOP in Africa. In addition, the com- bined effect of trabeculectomy and cataract surgery produces visual benefits for the patients. Keywords: Trabeculectomy; Glaucoma; Africa 1. Introduction Glaucoma is one of the most common causes of blind- ness in the world [1] and it causes irreversible visual loss [2]. This aspect is well known for the developed countries, however in Africa blindness mainly occurs due to cataract, trachoma and onchocercosis. Glaucoma is not mentioned enough. Patients present with severe findings after a long-lasting history of disease [1]. Data available from the United States and Barbados suggest that blacks (mostly of West African origin) are 4 - 8 times more like- ly to have glaucoma than whites and more likely to be blind due to glaucoma compared with the white popula- tion [3,4]. Treatment is difficult due to the unavailability and expensiveness of glaucoma medication [5]. This ma- kes surgery for glaucoma an attractive option. Trabecu- lectomy is also a well recognized treatment option for the surgical management of raised intraocular pressure (IOP) [6]. It has been reported to be more beneficial in Africans in terms of IOP lowering effect and slowing down of field loss [7,8] and has been reported to have some benefit in black people in Africa and the Caribbean area [9,10]. Wound healing modulating agents, usually anti- metabolites like 5-Fluorouracil and Mitomycin C which inhibit the natural healing response and scar formation are used to reduce trabeculectomy failure [11]. Primary trabeculectomy with MMC using a fornix-based conjun- ctival flap technique is an effective treatment for Thai glaucoma patients. Mean IOP was significantly decrea- sed from 26.1 + 11.7 mmHg to 11.7 + 4.4 mmHg (p < 0.001) at the last visit. At the last follow up period, 67 eyes (97.1%) were considered as success [12]. Wilkins and Wormald and their respective colleagues reported that the addition of antimetabolites to trabeculectomy reduced IOP among participants enrolled in their studies [13]. We decided to perform a systematic review in order to determine the outcome of trabeculectomy in African countries. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Search Strategy A search strategy was designed to identify publications Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa 77 which described trabeculectomy in Africa. The search was conducted from November to December 2012. We conducted an electronic search from the following databases: PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google, and Google scholar websites. The following search terms were used “trabeculectomy in Africa”, “treatment of glaucoma in Africa”, “follow-up of trabeculectomy in Africa”. 2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria Articles were included in the review if they met the following criteria: 1) they were conducted in Africa and covered trabeculectomy in Africa; 2) they covered our objective; 3) they were published in English; 4) they were published from 2000 to December 2012. Articles were excluded from the review if: 1) they were conducted outside African countries; 2) the trabeculec- tomy conducted in Africa was associated with another surgery other than cataract surgery; 3) the articles were conducted in Africa and covered trabeculectomy in Africa but we did not have access to the full text. Types of outcome measures: The main outcome measures of the study were intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction, visual acuity (VA), visual field (VF) and cup-disc (c/d) ratio. 2.3. Data Extraction Two authors independently viewed the titles and abstra- cts of all the studies identified in the electronic searches. All methodological steps followed the guide- lines set by QUOROM statement criteria [14]. The full copies of all possibly relevant studies were obtained and indepen- dently inspected by two authors to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. When a difference in opinion occurred, a third reviewer was consulted, as an arbiter. The authors of the selected studies were con- tacted to elucidate any doubts, when necessary. Included articles were studied for relevance and content. Data was extracted under the following areas: first author, year of publication, country of study, study population, study objectives, research methods and interventions. The main findings of each study were summarized. 2.4. Data Analysis The data for analysis and synthesis were the study me- thods, findings, and conclusion. 3. Results 3.1. Eligible Studies For trabulectomy outcomes in Africa, articles were re- trieved based on the search criteria above. Study selec- tion process is shown in Figure 1. The electronic sear- ches retrieved 109 citations, all citations were screened and 30 full text articles were retrieved for further as- sessment. A total of 18 articles were excluded because they were not conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, some of them were not about trabeculectomy in Africa and a number of them were not published in English. Finally, a total of 12 studies including 947 patients were eligible for the review. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. 3.2. Main Outcomes Articles reviewed were drawn from 5 sub-Saharan coun- tries (Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Ghana, and Kenya). There were 2 articles which used 5 FU during surgery [15,20], 2 articles used mitomycin C during the surgery [17,23], 3 articles did not use the antimetabolite during the surgery [11,18,21], 5 articles were on com- parative study, of those 4 compared between using 5FU and non antimetabolites surgeries [16,19,22,24] and 1 was on comparison between using these 2 antimetabo- lites (5FU and MMC)[25]. Among the articles, 4 were on trabeculectomy combined with cataract surgery [15,20, 23,24]. The duration of the last follow-up was 6 months to 60 months. The outcomes of the study were: 1) out- come of IOP post-trabeculectomy; 2) outcome of VA post-trabeculectomy; 3) outcome of the cup-disc ratio and the visual field post-operative. Outcome of IOP post-trabeculectomy. There was a success during the control of IOP for all the studies with a range of 10mmHg to 22 mmHg and the rates varied from 61.8% to 90%. Outcome of VA post-trabeculectomy. The VA was unchanged among 19% to 30% of the participants in the last follow-up, VA improvement rate was between 36% to 81.5% and worsened in 8.9% to 30.8% of the Figures 1. Flow chart of study selection based on the inclu- sion and exclusion criteria. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph 78 Table 1. Summary of studies of the outcome of trabeculectomy in Africa. First author, area, year Study population Study design and methodology Interventions Outcomes A.Lawan, Nigeria, 2007 [15] 71 eyes, 63 patients POAG Retrospective Trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite. 21% of them associated with cataract surgery VA as measured with Snellen`s or,Illiterate “C” c/d ratio was assessed with direct ophthalmoscope. IOP was measured with the applanation tonometer Perimetry was done with the 2 m Tangent screen using a 5 mm white target Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite Good intraocular pressure contro 82% of participants had IOP of 10 to 15mmHg, 15% had 16 to 20 mmHg. 19% of the patients had VA of 6/6 - 6/18 before and after surgery, 51% had visually impaired after surgery, 29% had severe visual impairement and 1% was blind. 13% had c/d ratio ≤ 0.5, 54% had c/d ratio = 0.6 - 0.8 and 33% had c/d ratio = 0.9. The perimetry result showed that 7% of the participants had peripheral field constriction of 10 - 20˚, 27% had both peripheral field constriction and arcuate scotoma, 48% had visual field of 30˚ and less (≤30˚) and 18% had ability to fixate on target. Adegbehingbe B.O, Nigeria, 2007 [16] 53 patients with 87.5%: primary glaucoma and 12.5% secondary glaucoma Retrospective IOP was measured and followed-up from day 1 to 12 months. 26.4% of the patients had trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite, 73.59% had trabeculectomy without application of antimetabolite. The outcome of the surgery was classified as complete success if post operative IOP at one year was 20 mmHg or less without anti-glaucoma medication Measuring of VA and IOP Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite Complete success was obtained in 61.8% of the participants at 12 months. High success rate for the both. The mean post-operative IOP in the 5FU-augmented cases was significantly lower compared with the non augmented cases (P = 0.005). There were no significant changes in the VA during the follow-up period. Manners T, South Africa, 2001 [17] 43 eyes 41 patients Traumatic angle recession glaucoma Retrospective Trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite. The last follow-up was at 60 months postoperative with a mean of 25 months. The outcome of the surgery was classified as “complete success” when the IOP was <21 mm Hg without glaucoma medication Measuring of VA and IOP Administration of MMC as antimetabolite At last follow-up, there was 76.7% of complete success for the IOP. For the VA, at last follow-up ranged from 6/9 to no light perception, the visual outcome was the same or better in 81.5%. Joy Kabiru, Tanzania, 2005 [18] - Retrospective 36% of the participant had trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite. Mean follow-up was 8 months. Measuring of VA and IOP Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite 73% had IOP of 15 mm Hg or less at latest follow-up (mean follow-up was 8.7 months) and 90% had IOP of 21 mm Hg or less (mean follow-up was 8.8 months). 25% patients lost VA at least 2 lines of Snellen acuity or equivalent between preoperative measurement and latest follow-up.  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa 79 Continued Gyasi M.E., Ghana, 2006 [11] 191 eyes 164 patients 96.8% POAG 3.2% normal tension glaucoma (NTG) Retrospective Trabeculectomy without application of antimetabolite Follow-up period was grouped into 4 categories: the first post-operative month, between the second and third months, fourth to fifth month and the sixth month and beyond Control IOP was only made in POAG patient. Successful IOP control defined as IOP less than 22 mmHg or a reduction of 30% if pre-operative pressure was already less than 22 mmHg. IOP was measured with standard Goldman applanation tonometer Statistically significant difference between the mean pre-op and post-op IOP (p = 0.001) with success of 88.46% of the eyes which had post-operative IOP < 22 mmHg at the last examination at six months. In eyes with NTG only 16.7% achieved a successful 30% target pressure reduction with post-op IOP of 8 mmHg. Yorston D, Kenya, 2001 [19] 68 eyes 68 patients Chronic open angle glaucoma Prospective Some patients had trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite. Major outcome measures were IOP at 6 months and probability of failure at 2 years. Failure was defined as a pressure of more than 26 mm Hg on one occasion, or a pressure of between 22 and 26 mm Hg on two occasions at least 2 months apart. Measuring of IOP and VA Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite The mean IOP was 17.4 mm Hg in the placebo group and 16.9 mmHg in the 5-FU group after 180 days of surgery. By 2 years after trabeculectomy, the probability of successful IOP control was 70.6% in the placebo group, and 88.8% in the 5-FU group. Among patients followed for 2 years, 30% lost 0.3 logMAR units of visual acuity. Bowman RJC, Tanzania, 2010 [20] 163 eyes 163 patients with Advanced glaucoma Retrospective 80% Trabeculectomy combined with cataract surgery with application of antimetabolite. IOP outcomes were analysed using two success criteria: follow-up IOP ranges of 6 - 15 and 6 - 20 mmHg. Measuring VA and IOP Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite Of those with at least a 6-month follow-up, 58% patients and 84% patients had IOPs of 6 - 15 and 6 - 20mmHg, respectively. Mean follow-up IOP was 15 mmHg. There was no significant difference in mean final follow-up IOP between those with and without 3 or 6 months of follow-up. 70% patients had improved their acuity compared with pre-operation by at least one line; 40 (37%) achieved 6/18 or better, and 71 66% achieved 6/60 or better. Of those with at least 3- and 6-month follow-up, 42 of 51 (82%) patients and 17 of 20 (85%) improved their acuity Anand N, Nigeria, 2001 [21] 142 eyes 100 patients POAG (84% advanced glaucoma) Retrospective Trabeculectomy without application of antimetabolite. Subsequent surgery for glaucoma and cataract was noted. Follow-up more than 6 months Criteria for success were an lOP reduction of more than 30% from pre-operative levels, a permanent decrease in visual acuity of 2 Snellen chart lines or less from pre-operative levels and lOP of less than either 22 mmHg (criterion 1) or 16 mmHg (criterion 2) with or without medication. Measuring of VA and IOP The cumulative success rates by the first criterion were 85% at the end of 1 year, falling to 71% in 5 years. By the second criterion success rates were much lower, being 65% at 1 year and 46% at 5 years. Failure of surgery was most frequently in the first 6 months after surgery but continued at a steady rate throughout the follow-up period. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa 80 Continued Gyasi M.E., Ghana, 2006 [11] 191 eyes 164 patients 96.8% POAG 3.2% normal tension glaucoma (NTG) Retrospective Trabeculectomy without application of antimetabolite Follow-up period was grouped into 4 categories: the first post-operative month, between the second and third months, fourth to fifth month and the sixth month and beyond Control IOP was only made in POAG patient. Successful IOP control defined as IOP less than 22 mmHg or a reduction of 30% if pre-operative pressure was already less than 22 mmHg. IOP was measured with standard Goldman applanation tonometer Statistically significant difference between the mean pre-op and post-op IOP (p = 0.001) with success of 88.46% of the eyes which had post-operative IOP < 22 mmHg at the last examination at six months. In eyes with NTG only 16.7% achieved a successful 30% target pressure reduction with post-op IOP of 8 mmHg. Yorston D, Kenya, 2001 [19] 68 eyes 68 patients Chronic open angle glaucoma Prospective Some patients had trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite. Major outcome measures were IOP at 6 months and probability of failure at 2 years. Failure was defined as a pressure of more than 26 mm Hg on one occasion, or a pressure of between 22 and 26 mm Hg on two occasions at least 2 months apart. Measuring of IOP and VA Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite The mean IOP was 17.4 mm Hg in the placebo group and 16.9 mmHg in the 5-FU group after 180 days of surgery. By 2 years after trabeculectomy, the probability of successful IOP control was 70.6% in the placebo group, and 88.8% in the 5-FU group. Among patients followed for 2 years, 30% lost 0.3 logMAR units of visual acuity. Bowman RJC, Tanzania, 2010 [20] 163 eyes 163 patients with Advanced glaucoma Retrospective 80% Trabeculectomy combined with cataract surgery with application of antimetabolite. IOP outcomes were analysed using two success criteria: follow-up IOP ranges of 6 - 15 and 6 - 20 mmHg. Measuring VA and IOP Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite Of those with at least a 6-month follow-up, 58% patients and 84% patients had IOPs of 6 - 15 and 6 - 20mmHg, respectively. Mean follow-up IOP was 15 mmHg. There was no significant difference in mean final follow-up IOP between those with and without 3 or 6 months of follow-up. 70% patients had improved their acuity compared with pre-operation by at least one line; 40 (37%) achieved 6/18 or better, and 71. 66% achieved 6/60 or better. Of those with at least 3- and 6-month follow-up, 42 of 51 (82%) patients and 17 of 20 (85%) improved their acuity. Anand N, Nigeria, 2001 [21] 142 eyes 100 patients POAG (84% advanced glaucoma) Retrospective Trabeculectomy without application of antimetabolite. Subsequent surgery for glaucoma and cataract was noted. Follow-up more than 6 months Criteria for success were an lOP reduction of more than 30% from pre-operative levels, a permanent decrease in visual acuity of 2 Snellen chart lines or less from pre-operative levels and lOP of less than either 22 mmHg (criterion 1) or 16 mmHg (criterion 2) with or without medication. Measuring of VA and IOP The cumulative success rates by the first criterion were 85% at the end of 1 year, falling to 71% in 5 years. By the second criterion success rates were much lower, being 65% at 1 year and 46% at 5 years. Failure of surgery was most frequently in the first 6 months after surgery but continued at a steady rate throughout the follow-up period. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa 81 Continued Ashaye AO, Nigeria, 2009 [22] 76 eyes 44 patients 92,1% POAG 7.9% chronic angle closure glaucoma Retrospective 32.9% had trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite and 67.1% had trabeculectomy without antimetabolite Follow-up for minimum of 12 month after surgery Measuring of IOP Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite The percentage of maintaining IOP of 21 mmHg or less at 1 year of follow-up was 79.4%. (80.6% for the non-5-FU group and 76.7% for the 5-FU group.) Comparison of the curve by the log-rank test showed no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.136). Harry A Quigley, Tanzania, 2000 [23] 21 patients - Prospective Visual acuity was measured at 4 metres using a tumbling E ETDRS chart. Visual field was measured using the Dicon LD400 automated instrument IOP was measured with calibrated TonoPen Optic disc area examined with a hand held, 78 dioptre lens and 10 x eye piece of the slit lamp. 80% of the patients had trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite 25% combined with cataract surgery 45% had iridectomy Follow-up of participants was till 3years after surgery Measuring of VA, IOP Examination of optic disc Administration of MMC as antimetabolite 88% of eyes were examined at 3 years. IOP declined from 29.9 mm Hg to 14.7 mm Hg at 3 years, with 89% achieving a reduction of 25% or more. The mean c/d ratio increased by only 0.027 units (0.66 (0.25) to 0.69 (0.22), p = 0.8, n = 13 eyes). The c/d ratio worsened by 0.05 units or more in four eyes, improved by 0.05 or more in three eyes, and was unchanged in the remainder. Among the yes with trabeculectomy alone, visual acuity was essentially unchanged in five eyes, improved by one or more line in four eyes, and was worse in eight eyes Mielke C, Nigeria, 2003 [24] 154 eyes 101 patients - Retrospective Trabculectomy with 2 groups of patients: group that received intraoperative antimetabolite and control group. Subsequent surgery for glaucoma and cataract was noted. Average follow-up was 17 ± 2.18 months. Major outcome measures were an IOP reduction of more than 30% from preoperative levels, a permanent decrease in visual acuity of two or less Snellen-chart lines from preoperative levels and: 1. IOP 20 mm Hg or less with or without medication. 2. IOP less than 14 mmHg with or without medication. Measuring VA and IOP Administration of 5FU as antimetabolite When an IOP of 20mmHg or less was defined as success, 76% of the 5-FU group and 79% of the control group were successful at 18 months. Comparison of survival curves did not show any significant difference by the log-rank test (p = 0.55). When success was defined as an IOP of 14 mmHg, the probability of success was 64% for the 5-FU group and 39% for the control group at 18 months. This difference was significant by the log-rank test (p = 0 .018). 5.1% of the control group and 8.9% for the 5FU group lost more than two lines of Snellen-chart visual acuity and the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.49). Nitin Anand, Nigeria, 2012 [25] 132 eyes 129 patients Primary trabeculect- omy Retrospective 73 eyes had trabeculectomy with application of antimetabolite. Two criteria for success were used for survival analyses. IOP of less than 19 and 15 mmHg, a decrease of 20% from preoperative IOP were used for Kaplan–Meier survival analyses. Measuring of VA, IOP Administration of 5FU and MMC as antimetabolite The 5-FU group had longer mean follow-up of 53 ± 26 months than the MMC group (38 ± 18 months, p < 0.001). The MMC group had significantly lower pressures at all postoperative visit except between 30 and 35 months (p = 0.07). The probability of maintaining an IOP less than 19 mmHg and 15 mmHg without additional medication or needle revisions at 2 and 3 years postoperatively was 71% and 64% respectively for the 5FU group and 81% and 79% respectively for the MMC group. The MMC group had significantly better survival times, both for IOP less than 19 mm Hg (p = 0.03) and IOP less than 15 mm Hg (p = 0.006). At last follow up, 40 eyes (30.3%) had lost more than 2 lines of Snellen visual acuity, 24 from 5-FU and 16 from the MMC group (p = 0.8). c/d ratio = cup-disc ratio; IOP = intraocular pressure; VA = visual acuity; 5FU = 5 fluorouracil; MMC = mitomycin C; POAG = primary open angle glaucoma; NTG = normal tension glaucoma. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph 82 participants. Outcome of the cup-disc (c/d) ratio and the visual fie- ld post-operative. The follow-up of the c/d was only found in 3 studies. In these cases, the c/d ratio was ≤0.5 in 13% and ≥0.8 in 83%. There was a failure on the c/d ratio of 0.9 and this increased by 0.027 units [23]. And for the visual field, there was a follow-up for only one study. 4. Discussion Trabeculectomy is the most common operative procedure for the treatment of medically uncontrolled glaucoma. It remains the mainstay of treatment for black glaucoma patients especially those of African origin due to the un- availability and high cost of topical therapy [26,27]. The findings of our review revealed that rates of IOP between 10 mmHg - 22 mmHg ranged from 61.8% to 90% in the reviewed articles. The criteria of the complete success of IOP were different for each study but all of them had significant complete success of more than 50%. Depending on the trabeculectomy with augmentation or not, all of them had a success result despite some authors suggesting that in African patients, a successful outcome of trabeculectomy may be compromised by an aggressive healing response [28,29]. Therefore, antimetabolites such as 5-FU or MMC can be used [30] as found by Adeg- behingbe in Nigeria in which the mean post-operative IOP in the 5FU-augmented cases was significantly lower compared with the non augmented cases (p = 0.005) [16]. A study conducted by Yorston in Kenya found that the placebo group was 2.18 times (95% CI 0.67 to 7.15) more likely to require additional IOP lowering proce- dures than the 5-FU group [19]. In another study con- ducted by Anand et al. in Nigeria trabeculectomy without antimetabolite use appeared to be an effective way to lower the IOP of advanced glaucoma to less than 22 mmHg but not to less than 16 mmHg [21]. From these results, regardless of the trabeculectomy being with or without augmentation of antimetabolite, combined or not with cataract surgery, it appears to be a good way to lowering the IOP in Africans. The results of this study are consistent with findings from elsewhere, for instance, Ioannis Kyprianou et al. found that with the longest fol- low-up period, trabeculectomy augmented with MMC under the scleral flap in difficult cases can achieve good long-term IOP control [31]. Leyland M et al. found that the effect of 5FU has been reported with conflicting re- sults such as showing no significant effect in other popu- lations [32]. Wang Mei et al. showed that phacotrabe- culectomy and trabeculectomy treatments exhibit similar IOP reduction, successful rates, and complications when it comes to treating PACG patients with coexisting cata- ract [33]. In addition, Vizzeri G and Weinreb RN showed that surgical alternatives combined with cataract extrac- tion may be utilized to achieve a more significant IOP reduction [34]. The results of ROTCHFORD A showed that the success rates of trabeculectomy were lower than those reported in developed countries, the difference may be attributed to differences in surgical technique and postoperative in- terventions such as suture removal/lysis, manipulation of the bleb, and tailored steroid dosage [35]. Argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) may have lower long term IOP lowering effect in blacks than whites [36]. Blacks have higher risk of ALT failure than whites [37]. In any case lasers are hard to come by in African setting. The VA was unchanged among 19% to 30% of the participants in the last follow-up, VA improvement rate was between 36% to 81.5% and worsened in 8.9% to 30.8% of the participants. Combined surgery produce visual benefit for most patients with similar pressure control to pure trabeculectomy [20]. The large prospec- tive studies such as Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) [38], Collaborative Normal Tension Glau- coma Study (CNTGS)[39] and Early Manifest Glaucoma Treatment Study (EMGTS) [40] have demonstrated that lower IOPs are associated with reduced risk for progress- sion of visual field damage and visual loss [41]. Ioannis Kyprianou et al. found the main reason for reduced vi- sion was pre-existing co-morbidity and development of lenticular opacities [31]. In a study conducted by Stal- mans et al., no change in visual acuity was noted: visual acuity before and at 1 month postoperatively was 0.67 (0.3) (range 0.01 - 1) and 0.61 (0.3) (range 0.02 - 1.0; p = 0.25) on average [42]. Visual loss of more than two Snellen-chart lines was observed in a significant propor- tion of patients who had primary trabeculectomy in a Nigerian population [43]. Bekibele found a statistically significant decrease in visual acuity post-operatively [27]. Brian A. et al., Law SK found snuff-out (or severe long- term unexplained vision loss after trabeculectomy with mitomycin C treatment [44-46] and the risk factor for long-term vision loss was preoperative split fixation on VF. Transient vision loss is common and may take up to 2 years for recovery [44]. The results of the review also indicate that the fol- low-up of the c/d was found in 3 studies. In these cases, the c/d ratio was ≤0.5 in 13% and ≥0.8 in 83%. There was a failure on the c/d result from 0.9 or worse and in- creasing by 0.027 units [23]. Mielke C et al showed 70% of eyes had advanced glaucomatous optic disc cupping or visual field loss affecting central vision [24]. Kotecha and coworkers identified “significant” increases in rim volume at 2 years following surgical operations which produced a fall in pressure of around 30%. The reversal of disc cupping following trabeculectomy can be present up to 2 years after pressure reduction [47]. Reversal of  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa 83 optic disc cupping following intraocular pressure reduc- tion is a well known phenomenon [48] and changes seen in juvenile glaucomas are more pronounced than those found in adult patients [49,50]. The clinical significance of these disc changes appears to be unclear, although reports have suggested that there may be an associated improvement of visual function that corresponds to this improvement in disc appearance [39,51-54]. But a study by Park et al. described short-term (follow-up of two months) reversal of optic disc cupping documented by Heidelberg Retina Tomograph (HRT) in adult glaucoma patients (mean age of 59.3 ± 9.1 years) after IOP reduc- tion following trabeculectomy [55]. And Swinnen et al. documented two young-adult patients (33-year-old and 14-year-old) with reversal of optic disc cupping after trabeculectomy lasted for 6 and 36 months respectively and showed an improvement of cup to disc area ratio on HRT [56]. There was a follow-up for only one study on visual field in our review. Blacks of all ages had worst visual fields than whites when 60˚ Humphrey’s visual field was tested [57]. The progression of visual field loss is higher in blacks than whites [58]. Visual fields remained stable in 73.3% of cases during the follow-up period [59]. In any case diagnosis of visual field progression remains difficult, particularly in eyes with advanced field loss, due to long-term fluctuation of fields [60]. A study of Swinnen S et al. documented two young-adult patients (33-year-old and 14-year-old) who showed an improve- ment in visual field for at least 3 months after trabe- culectomy for the first patient and the second patient for 3 years [56]. The facts that mean IOPs of 14 mmHg can result in stable visual field has been concluded from several major clinical studies [61,62]. Moreover, IOP fluctuations are a known risk factor for visual field progression [63]. Any- way careful postoperative follow-up observation of the visual field remains necessary even after successful sur- gical pressure reduction [64]. The study has the following limitations; the review only included articles of studies conducted in only five African countries as such the findings of the study cannot be generalized to the entire African population. Poor ac- ceptance of the surgery and late presentation of patients to the hospital also affected the outcomes trabeculectomy among the studies included in this review. The IOP at presentation was high in most of the patients [65]. One third of the patients had c: d ratio of 0.9 at presentation [66]. Even those who presented earlier and despite in- tense effort at health education on the nature of the dis- ease, it was difficult to convince some patients that the eye that could see far well had a potentially sight threat- ening disease [66]. Peter R Egbert found that patients are often put off or refuse surgery until they have severe vi- sion loss [67]. A Tanzanian study, found that only 46% of patients accepted trabeculectomy even though they were offered free surgery, hospitalization, and food [2]. In interactions and discussions made by Peter R Egbert with West African ophthalmologists showed that one finds an understandable reluctance to do trabeculecto- mies because of poor patient acceptance, the difficulty of postoperative care, and uncertain results. In fact, most ophthalmologists do no glaucoma surgery [67]. Another limitation of the study was that only studies published in English language were included in the study. We might have left out some studies conducted in other languages which might have contributed significantly to our study. Furthermore, the duration of follow-up was short and differed across the studies included in the review. The follow-up period was short and drop-out rate was sig- nificantly high but these were beyond our control [68]. The problem of loss to follow-up in Africa seems to have started long time ago. In 1979 and 1990, Thommy CP et al. and Verry JD already concluded that “One of the big- gest problems in most studies is the lack of adequate fol- low-up” [69,70]. 5. Conclusion Trabeculectomy with or without application of antime- tabolite appears to be a good way of lowering the IOP in Africa. In addition, combining trabeculectomy with cata- ract surgery produces visual benefit for the patients. There is a need for African countries to adopt ways of improving and expanding the duration of follow-up of post-operative patients. More longitudinal studies are also needed on outcomes of trabeculectomy in most of the African countries in order to have enough evidence on the effectiveness of the procedure. Educating the popula- tion on the severity of glaucoma is also warranted. Prac- titioners should also be motivated to do fundoscopy and identify optic disc cupping and refer in time the sus- pected cases to the ophthalmologists. Furthermore, the practitioners and opthalmologists should be offered con- tinuous training on trabeculectomy. REFERENCES [1] C. Werschnik, C. Schäferhoff, F. W. Wilhelm, et al., “The Problem of Glaucoma in Africa—Progress Report from CAMEROON,” Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augen- heilkunde, Vol. 222, No. 10, 2005, pp. 832-834. doi:10.1055/s-2005-858462 [2] H. A. Quigley, R. R. Buhrmann, S. K. West, et al., “Long Term Results of Glaucoma Surgery among Participants in an East African Population Survey,” British Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 84, No. 8, 2000, pp. 860-864. doi:10.1136/bjo.84.8.860 [3] A. Sommer, J. M. Tielsch, J. Katz, et al., “Relationship between Intraocular Pressure and Primary Open Angle Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa 84 Glaucoma among White and Black Americans,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 109, No. 8, 1991, pp. 1090-1095. doi:10.1001/archopht.1991.01080080050026 [4] M. C. Leske, A. M. Connell, A. P. Schachat, et al., “The Barbados Eye Study: Prevalence of Open Angle Glau- coma,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 112, No. 6, 1994, pp. 821-829. doi:10.1001/archopht.1994.01090180121046 [5] J. D. Verry, A. Foster, R. Wormald, et al., “Chronic Glau- coma in Northern Ghana: A Retrospective Study of 397 Patients,” Eye, Vol. 4, Pt. 1, 1990, pp. 115-120. doi:10.1038/eye.1990.14 [6] K. Nouri-Mahdavi, L. Brigatti, M. Weitzman, et al., “Outcomes of Trabeculectomy for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma,” Ophthalmology, Vol. 102, No. 12, 1995, pp. 1760-1769. [7] R. David, J. Freedman and M. H. Luntz, “Comparative Study of Watsons and Cairns Trabeculectomies in a Black Population with Open Angle Glaucoma,” British Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 61, No. 2, 1977, pp. 117-119. doi:10.1136/bjo.61.2.117 [8] C. P. Thommy and I. S. Bhar, “Trabeculectomy in Nige- rian Patients with Open-Angle Glaucoma,” British Jour- nal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 63, No. 9, 1979, pp. 636-642. doi:10.1136/bjo.63.9.636 [9] R. David, J. Freedman and M. H. Luntz, “Comparative Study of Watson’s and Cairn’s Trabeculectomies in a Black Population with Open Angle Glaucoma,” British Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 61, No. 2, 1977, pp. 117- 119. doi:10.1136/bjo.61.2.117 [10] M. R. Wilson, “Posterior Lip Sclerectomy vs Trabeculec- tomy in West Indian Blacks,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 107, No. 11, 1989, pp. 1604-1608. doi:10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020682027 [11] M. E. Gyasi, W. M. K. Amoaku, O. A. Debrah, et al., “Outcome of Trabeculectomies without Adjunctive An- timetabolites,” Ghana Medical Journal, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2006, pp. 39-44. [12] L.-A. Lim, P. Chindasub and N. Kitnarong, “The Surgical Outcome of Primary Trabeculectomy with Mitomycin C and A Fornix-Based Conjunctival Flap Technique in Thailand,” Journal of the Medical Association of Thai- land, Vol. 91, No. 10, 2008, pp. 1551-1557. [13] M. V. Boland, A.-M. Ervin, D. S. Friedman, et al., “Com- parative Effectiveness of Treatments for Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 158, No. 4, 2013, pp. 271-279. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00008 [14] D. Moher, D. J. Cook, S. Eastwood, et al., “Improving the Quality of Reports of Meta-Analyses of Randomised Controlled Trials: the QUOROM Statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyses,” Lancet, Vol. 354, No. 9193, 1999; pp. 1896-1900. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04149-5 [15] A. Lawan, “Pattern of Presentation and Outcome of Sur- gical Management of Primary Open Angle Glaucoma in Kano, Northern Nigeria,” Annals of African Medicine, Vol. 6, No. 4, 2007, pp. 180-185. doi:10.4103/1596-3519.55700 [16] B. O. Adegbehingbe and T. Majemgbasan, “A Review of Trabeculectomies at a Nigerian Teaching Hospital,” Ghana Medical Journal, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2007, pp. 176-180. [17] T. Manners, J. F. Salmon and A. Barron, “Trabeculectomy with Mitomycin C in the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Angle Recession Glaucoma,” British Journal of Oph- thalmology, Vol. 85, No. 2, 2001, pp. 159-163. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.2.159 [18] J. Kabiru, R. Bowman, M. Wood, et al., “Audit of Tra- beculectomy at a Tertiary Referral Hospital in East Af- rica,” Journal of Glaucoma, Vol. 14, No. 6, 2005, pp. 432-434. doi:10.1097/01.ijg.0000185617.98915.36 [19] D. Yorston and P. T. Khaw, “A Randomised Trial of the Effect of Intraoperative 5-FU on the Outcome of Trabe- culectomy in East Africa,” British Journal of Ophthal- mology, Vol. 85, No. 9, 2001, pp. 1028-1030. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.9.1028 [20] R. J. C. Bowman, A. Hay, M. L. Wood, et al., “Combined Cataract and Trabeculectomy Surgery for Advanced Glaucoma in East Africa: Visual and Intra-Ocular Pres- sure Outcomes,” Eye, Vol. 24, 2010, pp. 573-577. doi:10.1038/eye.2009.132 [21] N. Anand, C. Mielke and V. K. Dawda, “Trabeculectomy Outcomes in Advanced Glaucoma in Nigeria,” Eye, Vol. 15, 2001, pp. 274-278. doi:10.1038/eye.2001.93 [22] A. O. Ashaye and O. O. Komolafe, “Post-Operative Com- plication of Trabeculectomy in Ibadan, Nigeria: Outcome of 1-Year Follow-Up,” Eye, Vol. 23, 2009, pp. 448-452. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702979 [23] H. A. Quigley, R. R. Buhrmann and S. K. West, “Long Term Results of Glaucoma Surgery among Participants in an East African Population Survey,” British Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 84, No. 8, 2000, pp. 860-864. doi:10.1136/bjo.84.8.860 [24] C. Mielke, V. K. Dawda and N. Anand, “Intraoperative 5-Fluorouracil Application during Primary Trabeculecto- my in Nigeria: A Comparative Study,” Eye, Vol. 17, 2003, pp. 829-834. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700492 [25] N. Anand and V. K. Dawda, “A Comparative Study of Mitomycin C and 5-Fluorouracil Trabeculectomy in West Africa,” Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2012, pp. 147-152. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.92132 [26] A. M. Agbeja-Bayeroju, M. Omoruyi and E. T. Owoaje, “Effectiveness of Trabeculectomy on Glaucoma Patients in Ibadan,” African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 30, No. 1-2, 2001, pp. 39-42. [27] C. O. Bekibele, “Evaluation of 56 Trabeculectomy Oper- ations at Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State, Nigeria,” West African Journal of Medicine, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2001, pp. 223-226. [28] D. Broadway, I. Grierson and R. Hitchings, “Racial Differences in the Results of Glaucoma Filtration Surgery: Are Racial Differences in the Conjunctival Cell Profile Important?” British Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 78, No. 6, 1994, pp. 466-475. doi:10.1136/bjo.78.6.466 [29] F. Ederer, D. A. Gaasterland, L. G. Dally, J. Kim, P. C. Van Veldhuisen, B. Blackwell, et al., “The Advanced Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa 85 Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 13. Comparison of Treatment Outcomes within Race: 10-Year Results,” Ophthalmology, Vol. 111, No. 4, 2004, pp. 651-664. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.025 [30] C. Akarsu, M. Onol and B. Hasanreisoglu, “Postoperative 5-Fluorouracil versus Intraoperative Mitomycin C in High-Risk Glaucoma Filtering Surgery: Extended Follow up,” Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2003, pp. 199-205. doi:10.1046/j.1442-9071.2003.00645.x [31] I. Kyprianou, M. Nessim, V. Kumar, et al., “Long-Term Results of Trabeculectomy with Mitomycin C Applied under the Scleral Flap,” International Ophthalmology, Vol. 27, No. 6, 2007, pp. 351-355. doi:10.1007/s10792-007-9092-3 [32] M. Leyland, P. Bloom, E. Zinicola, et al., “Single Intra- operative Application of 5-Fluorouracil versus Placebo in Low-Risk Trabeculectomy Surgery: A Randomized Trial,” Journal of Glaucoma, Vol. 10, No. 6, 2001, pp. 452-457. doi:10.1097/00061198-200112000-00003 [33] M. Wang, M. Fang, Y.-J. Bai, et al., “Comparison of Combined Phacotrabeculectomy with Trabeculectomy Only in the Treatment of Primary Angle-Closure Glau- coma,” Chinese Medical Journal, Vol. 125, No. 8, 2012, pp. 1429-1433. [34] G. Vizzeri and R. N. Weinreb, “Cataract Surgery and Glaucoma,” Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2010, pp. 20-24. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e328332f562 [35] A. Rotchford, “What Is Practical in Glaucoma Manage- ment?” Eye, Vol. 19, 2005, pp. 1125-1132. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6701972 [36] A. L. Schwartz, D. C. Love and M. A. Schwartz, “Long Term Follow up of Argon Laser Trabeculoplasty for Uncontrolled Open Angle Glaucoma,” Archives of Oph- thalmology, Vol. 103, No. 10, 1985, pp. 1482-1484. doi:10.1001/archopht.1985.01050100058018 [37] AGIS, “The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 9. Comparison of Glaucoma Outcomes in Black and White Patients within Treatment Groups,” American Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 132, No. 3, 2001, pp. 311-320. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(01)01028-5 [38] M. A. Kass, D. K. Heuer, E. J. Higginbotham, et al., “The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: A Randomized Trial Determines that Topical Ocular Hypotensive Medi- cation Delays or Prevents the Onset of Primary Open- Angle Glaucoma,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 120, No. 6, 2002, pp. 701-713. doi:10.1001/archopht.120.6.701 [39] Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group, “Comparison of Glaucomatous Progression between Un- treated Patients with Normal-Tension Glaucoma and Pa- tients with Therapeutically Reduced Intra Ocular Pre- ssures,” American Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 126, No. 4, 1998, pp. 487-497. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(98)00223-2 [40] A. Heijl, M. C. Leske, B. Bengtsson, et al., “Reduction of Intraocular Pressure and Glaucoma Progression: Results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 120, No. 10, 2002, pp. 1268-1279. doi:10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268 [41] P. S. Mahar and A. D. Laghari, “Intraocular Pressure Control and Post Operative Complications with Mito- mycin-C Augmented Trabeculectomy in Primary Open Angle and Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma,” Pakistan Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2011, pp. 35- 39. [42] I. Stalmans, A. Gillis, A.-S. Lafaut, et al., “Safe Trabe- culectomy Technique: Long Term Outcome,” British Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 90, No. 1, 2006, pp. 44- 47. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.072884 [43] B. J. Gonzalez, M. I. Gonzalez, G. M. Gonzalez, R. Marin, A. Varas and T. M. Montesinos, “Non-Penetrating Deep Trabeculectomy Treated with Mitomycin C without Im- plant. A Prospective Evaluation of 55 Cases,” French Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 27, No. 8, 2004, pp. 907- 911. [44] A. B. Francis, B. Hong and J. Winarko, “Vision Loss and Recovery after Trabeculectomy Risk and Associated Risk Factors,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 129, No. 8, 2011, pp. 1011-1017. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.182 [45] S. P. Aggarwal and S. Hendeles, “Risk of Sudden Visual Loss Following Trabeculectomy in Advanced Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma,” British Journal of Ophthalmo- logy, Vol. 70, No. 2, 1986, pp. 97-99. doi:10.1136/bjo.70.2.97 [46] S. K. Law, A. M. Nguyen, A. L. Coleman and J Caprioli, “Severe Loss of Central Vision in Patients with Advanced Glaucoma Undergoing Trabeculectomy,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 125, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1044-1050. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.8.1044 [47] A. Kotecha, D. Siriwardena and F. W. Fitzke, “Optic Disc Changes Following Trabeculectomy: Longitudinal and Localisation of Change,” British Journal of Ophthal- mology, Vol. 85, No. 8, 2001, pp. 956-961. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.8.956 [48] M. R. Lesk, G. L. Spaeth, A. Azuaro-Blanco, et al., “Reversal of Optic Disc Cupping after Glaucoma Surgery Analyzed with a Scanning Laser Tomograph,” Ophthal- mology, Vol. 106, No. 5, 1999, pp. 1013-1018. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00526-6 [49] R. N. Shaffer and J. Hetherington Jr., “The Glaucomatous Disc in Infants. A Suggested Hypothesis for Disc Cup- ping,” Transactions of the American Academy of Oph- thalmology, Vol. 73, No. 5, 1969, pp. 923-935. [50] A. L. Robin and H. A. Quigley, “Transient Reversible Cupping in Juvenile-Onset Glaucoma,” American Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 88, No. 3, 1979, pp. 580-584. [51] L. J. Katz, G. L. Spaeth, L. B. Cantor, et al., “Reversible Optic Disk Cupping and Visual Field Improvement in Adults with Glaucoma,” American Journal of Ophthal- mology, Vol. 107, No. 5, 1989, pp. 485-492. [52] C. S. Tsai, D. H. Shin, J. Y. Wan, et al., “Visual Field Global Indices in Patients with Reversal of Glaucomatous Cupping after Intraocular Pressure Reduction,” Ophthal- mology, Vol. 98, No. 9, 1991, pp. 1412-1419. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Outcomes of Trabeculectomy in Africa Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph 86 [53] G. L. Spaeth, “The Effect of Change in Intraocular Pressure on the Natural History of Glaucoma: Lowering Intraocular Pressure in Glaucoma can Result in Im- provement of Visual Fields,” Transactions of the Oph- thalmological Societies of the United Kingdom, Vol. 104, No. 3, 1985, pp. 256-264. [54] E. Yildirim, A. H. Bilge and S. Ilker, “Improvement of Visual Field Following Trabeculectomy for Open Angle Glaucoma,” Eye, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1990, pp. 103-106. doi:10.1038/eye.1990.12 [55] K. H. Park, D. M. Kim and D. H. Youn, “Short-Term Change of Optic Nerve Head Topography after Trabecul- ectomy in Adult Glaucoma Patients as Measured by Heidelberg Retina Tomography,” Korean Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1997, pp. 1-6. [56] S. Swinnen, I. Stalmans and T. Zeyen, “Reversal of Optic Disc Cupping with Improvement of Visual Field and Stereometric Parameters after Trabeculectomy in Young Adult Patients. (Two Case Reports),” Bulletin de la Société Belge d’Ophtalmologie, Vol. 316, 2010, pp. 49- 57. [57] G. S. Rubin, S. K. West, B. Munoz, et al., “A Com- prehensive Assessment of Visual Impairment in a Popu- lation of Older Americans. The SEE Study. Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project,” Investigative Ophthalmology & Vi- sual Science, Vol. 38, No. 3, 1997, pp. 557-568. [58] R. Wilson, T. M. Richardson, E. Hertzmark, et al., “Race as a Risk Factor for Progressive Glaucomatous Damage,” Annals of Ophthalmology, Vol. 17, No. 10, 1985, pp. 653-659. [59] H. J. Beckers, K. C. Kinders and C. A. Webers, “Five Year Results of Trabeculectomy with Mitomycine C,” Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthal- mology, Vol. 241, No. 2, 2003, pp. 106-110. doi:10.1007/s00417-002-0621-5 [60] R. J. Boeglin, J. Caprioli and M. Zuluaf, “Long-Term Fluctuation of Visual Field in Glaucoma,” American Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 113, No. 4, 1992, pp. 396-400. [61] C. Migdal, W. Gregory and R. Hitchings, “Long-Term Functional Outcome after Early Surgery Compared with Laser and Medicine in Open-Angle Glaucoma,” Ophthal- mology, Vol. 101, No. 10, 1994, pp. 1651-1656. [62] AGIS Investigators, “The Advanced Glaucoma Interven- tion Study (AGIS): 7. The Relationship between Control of Intraocular Pressure and Visual Field Deterioration. The AGIS Investigators,” American Journal of Ophthal- mology, Vol. 130, No. 4, 2000, pp. 429-440. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00538-9 [63] K. Nouri-Mahdavi, D. Hoffman, A. L. Coleman, et al., “Predictive Factors for Glaucomatous Visual Field Pro- gression in the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study,” Ophthalmology, Vol. 111, No. 9, 2004, pp. 1627-1635. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.017 [64] E. B. Werner, S. M. Drance and M. Schulzer, “Trabe- culectomy and the Progression of Glaucomatous Visual Field Loss,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 95, No. 8, 1977, pp. 1374-1377. doi:10.1001/archopht.1977.04450080084008 [65] A. Sommer, J. M. Tielsch, J. Katz, et al., “Relationship between Intraocular Pressure and Primary Angle Glau- coma among White and Black Americans,” The Balti- more Eye Survey,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 109, No. 8, 1991, pp. 1090-1095. [66] H. A. Quigley, E. M. Addicks, W. R. Green and A. E. Maumenee, “Optic Nerve Damage in Human Glaucoma. II. The Site of Injury and Susceptibility to Damage,” Archives of Ophthalmology, Vol. 99, No. 4, 1981, pp. 635-649. doi:10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010635009 [67] P. R. Egbert, “Glaucoma in West Africa: A Neglected Problem,” British Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 86, No. 2, 2002, pp. 131-132. doi:10.1136/bjo.86.2.131 [68] M. E. Gyasi, W. M. K. Amoaku, O. A. Debrah, et al., “Outcome of Trabeculectomies without Adjunctive Anti- metabolites,” Ghana Medical Journal, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2006, pp. 39-44. [69] C. P. Thommy and I. S. Bhar, “Trabeculectomy in Nige- rian Patients with Open-Angle Glaucoma,” British Jour- nal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 63, No. 9, 1979, pp. 636-642. doi:10.1136/bjo.63.9.636 [70] J. D. Verry, A. Foster, R. Wormald, et al., “Chronic Glau- coma in Northern Ghana: A Retrospective Study of 397 Patients,” Eye, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1990, pp. 115-120. doi:10.1038/eye.1990.14

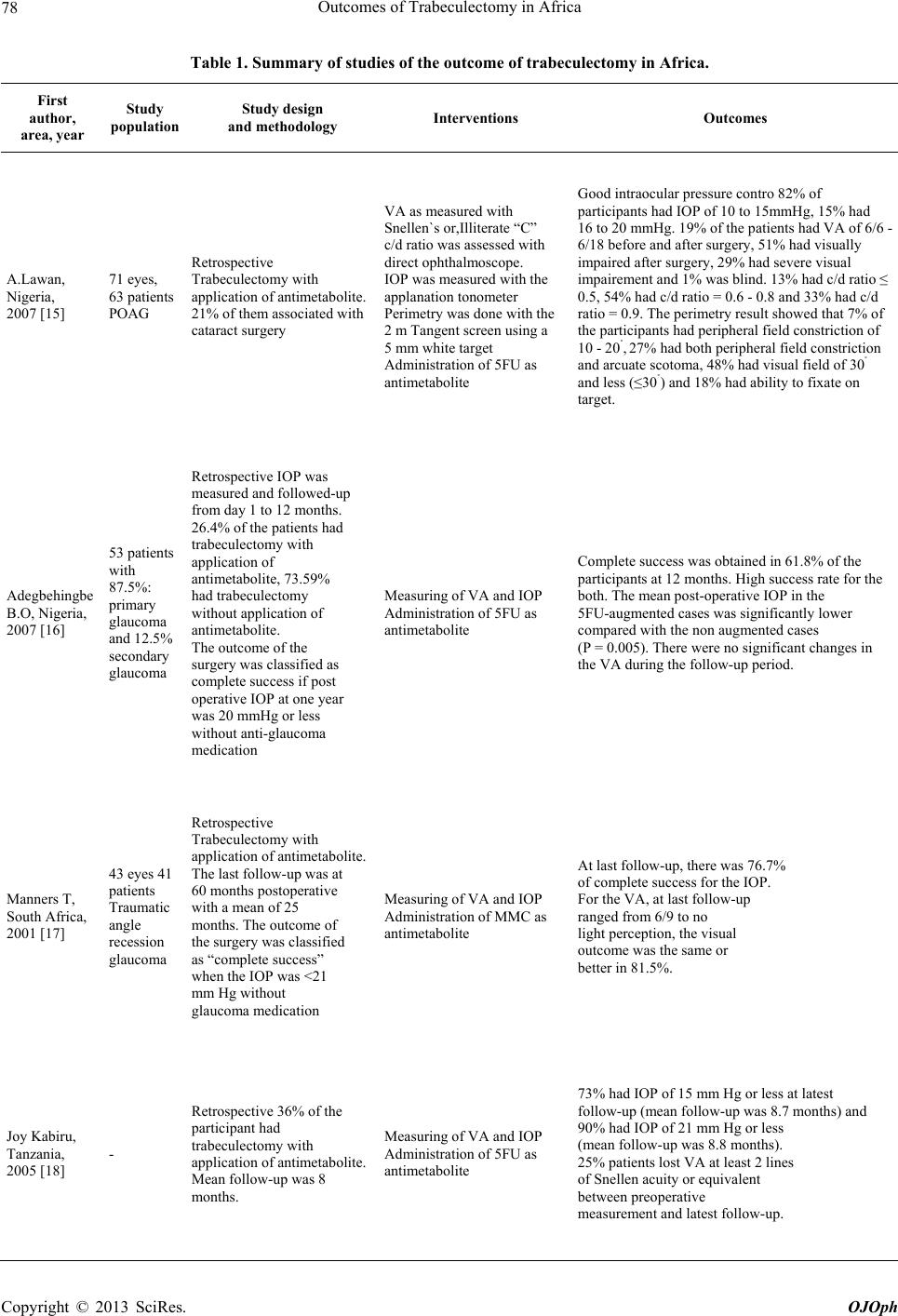

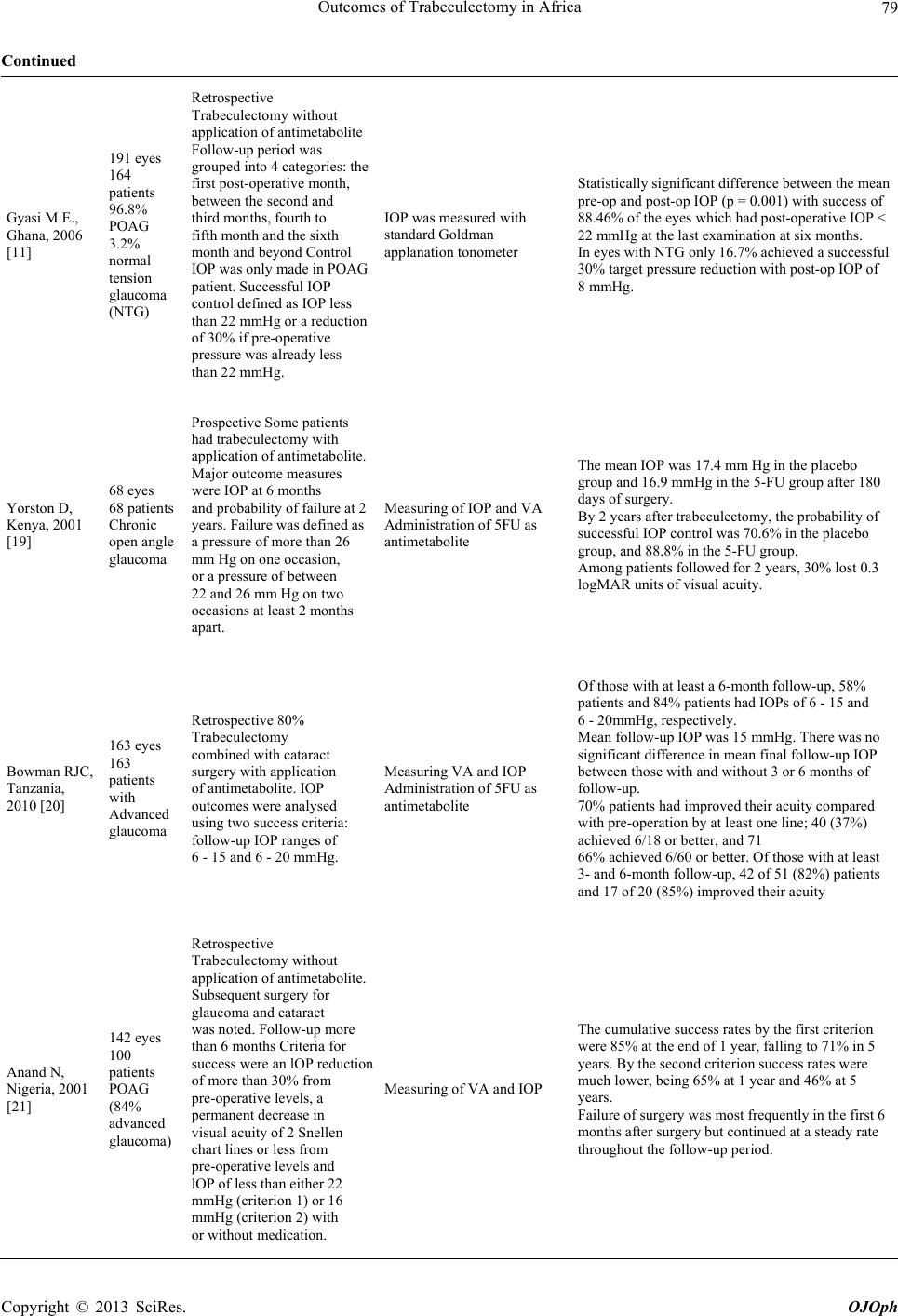

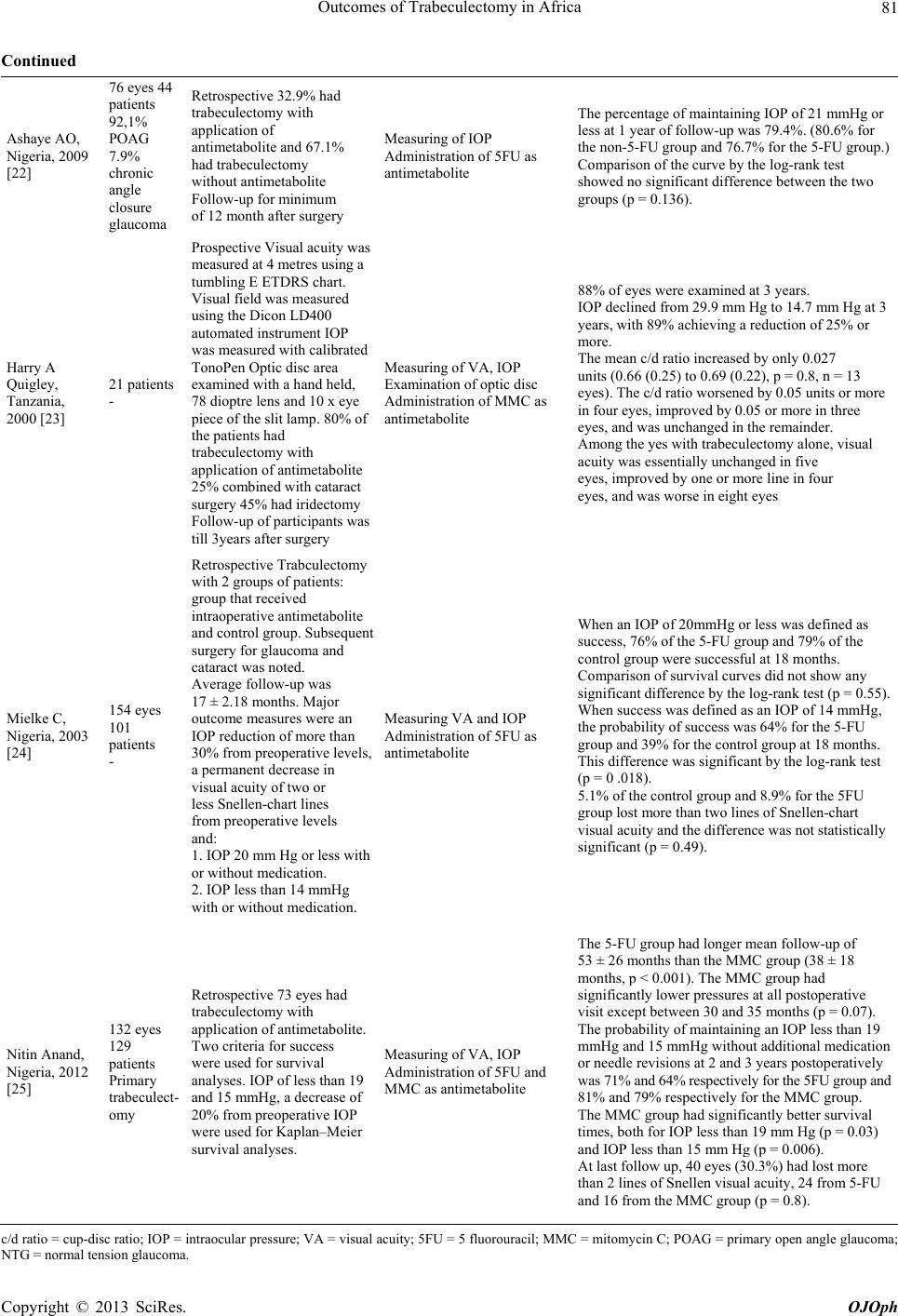

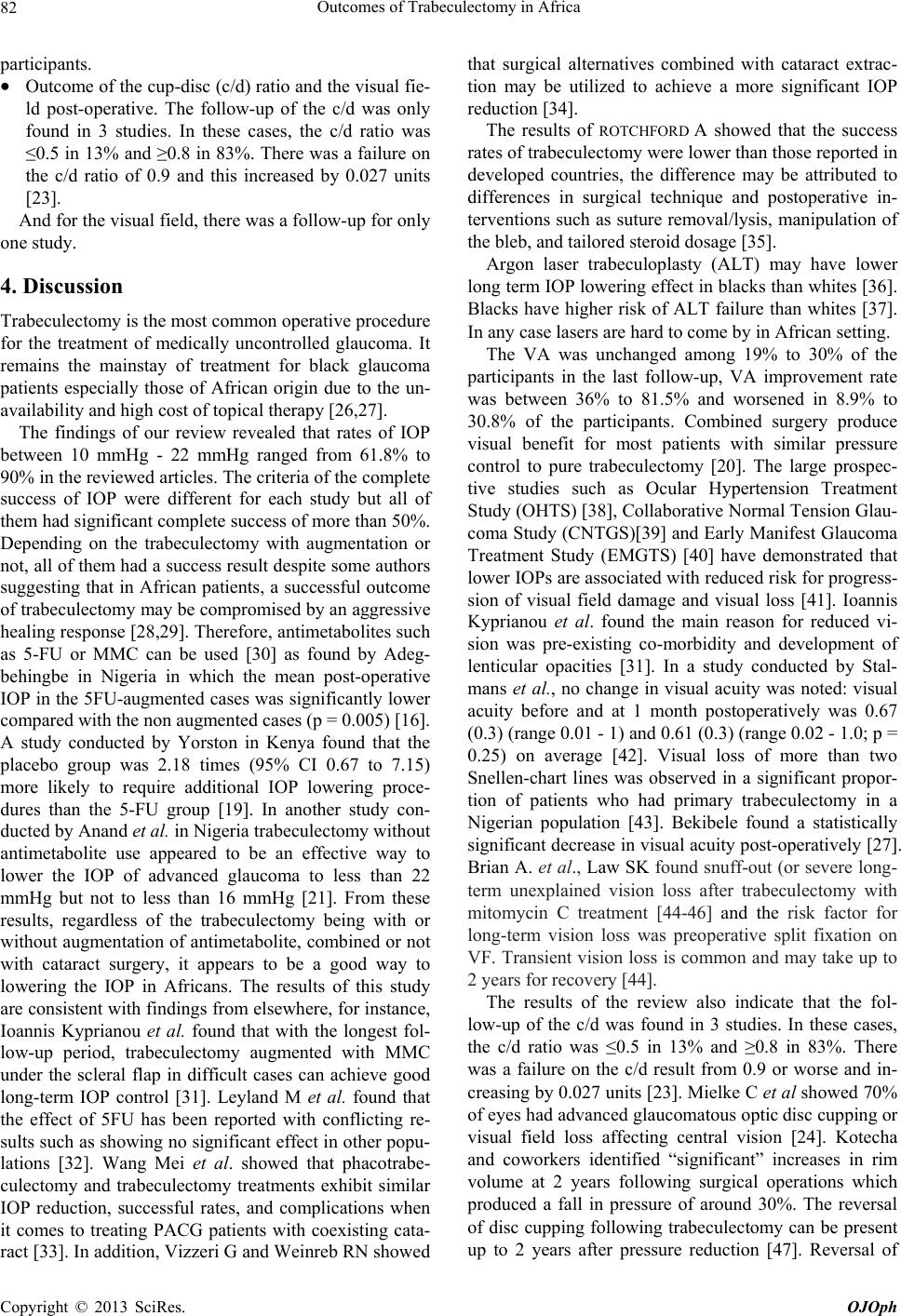

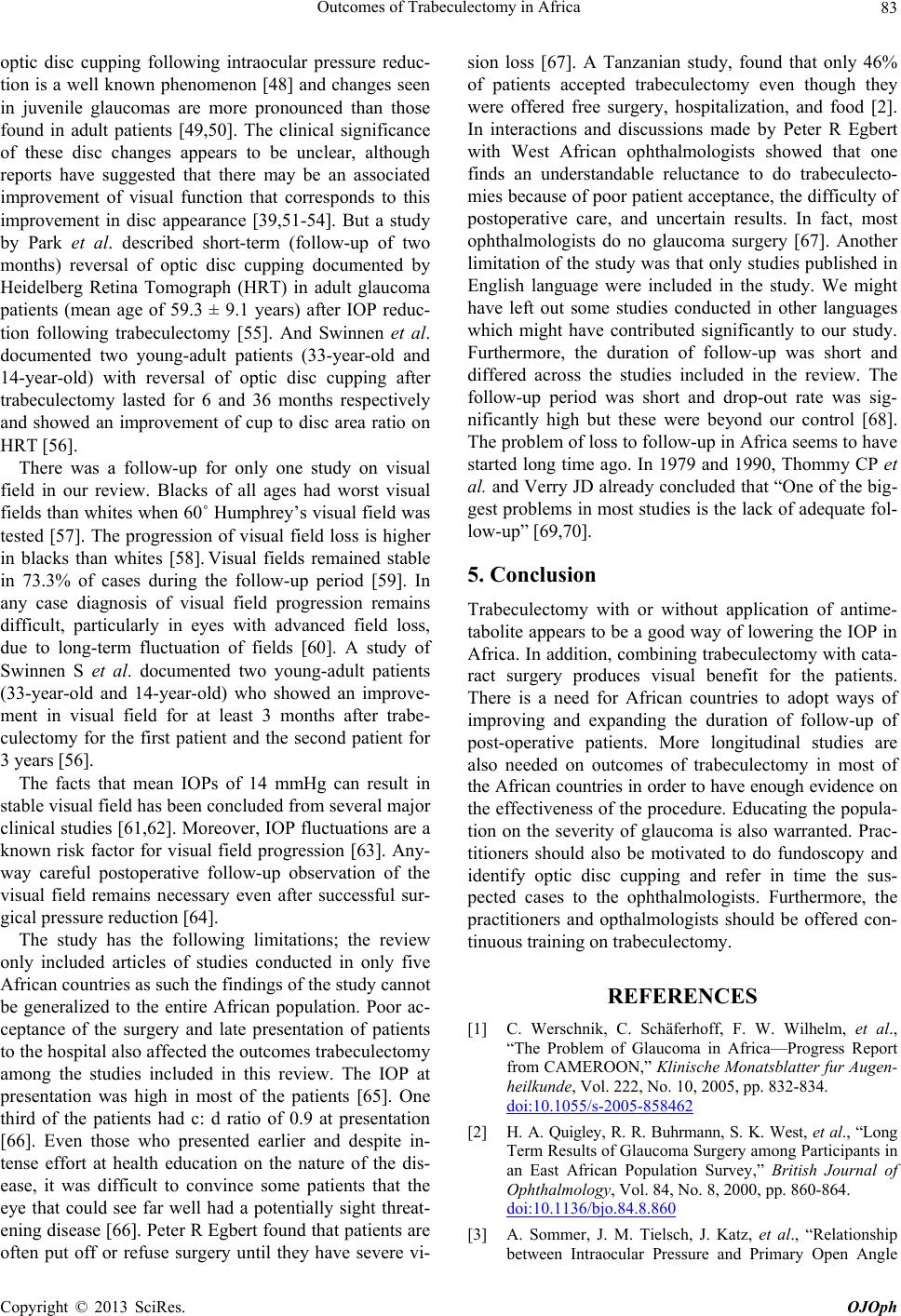

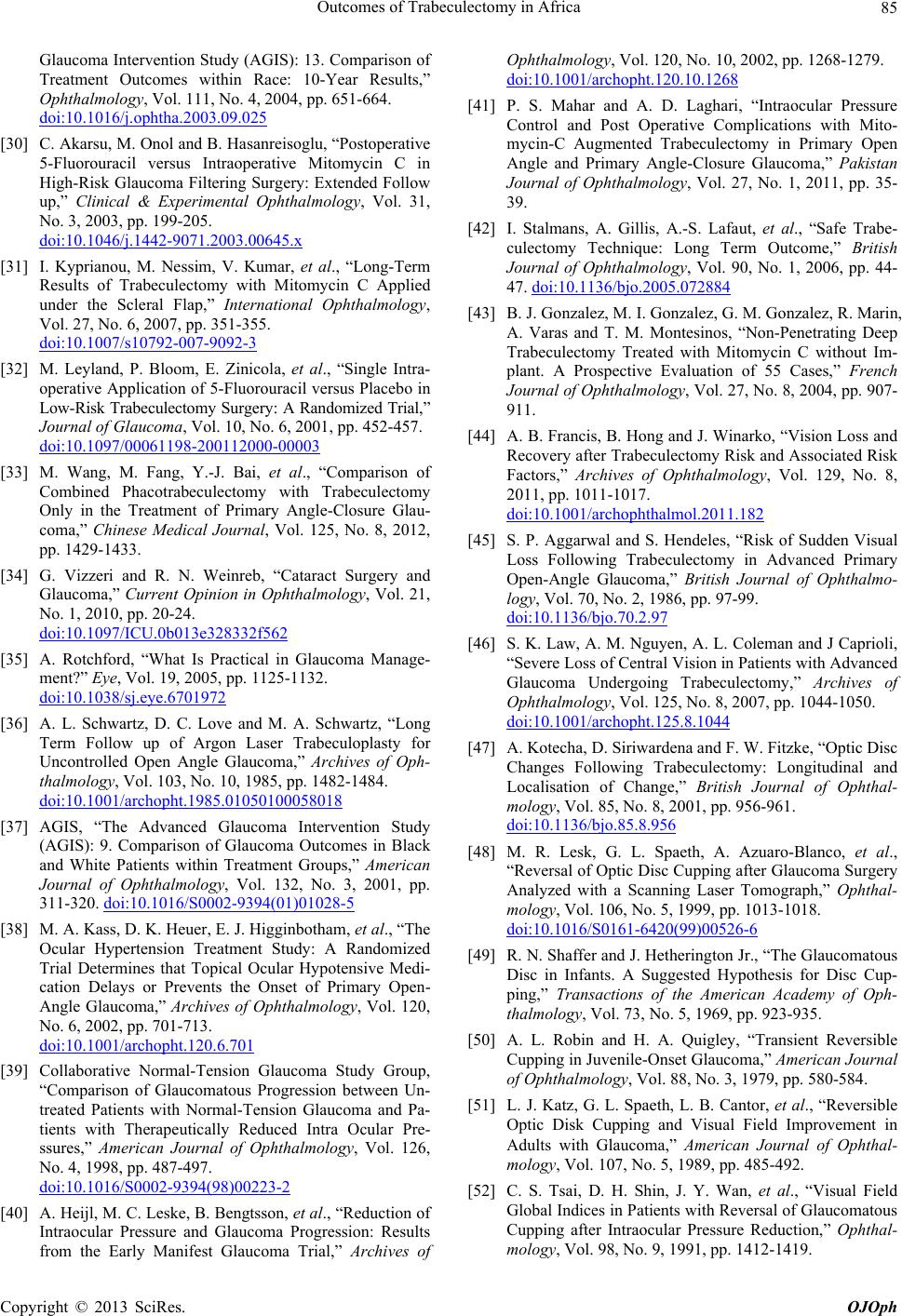

|