Open Journal of Ophthalmology, 2013, 3, 61-67 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojoph.2013.33015 Published Online August 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojoph) 61 Application of Pedagogical Perspectives in the Teaching and Training of New Cataract Surgeons—A Literature-Based Essay Björn Johansson Department of Ophthalmology, Linköping University Hospital, Linköping, Sweden. Email: bjorn.johansson@lio.se Received May 14th, 2013; revised June 15th, 2013; accepted July 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Björn Johansson. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Cataract is the most common cause of visual impairment that can be effectively treated by surgery and cataract surgery is the most commonly performed surgical procedure in the world. With modern cataract operation techniques, patients expect excellent results. Teaching and training of new surgeons involve both pedagogical and ethical challenges for teachers and trainees, and also may pose a potential risk to patients. This literature-based essay aims to describe how behavioristic, cognitiv e and con ceptu al learning perspectives can be recogn ized during the trainee surg eon’s progress. It also describes how teacher-pupil relationships may vary during the training process. Finally it presents the concept of situational tutorship, where the teacher adapts to the stages that the trainee passes through with increasing experience. Teaching and trainee surgeons who are aware of pedagogical concepts such as teacher-pupil relationships and tutoring strategies may use this knowledge to optimize the learning process. Further research is needed to clarify how using this knowledge may affect the training of new cataract surgeons. Keywords: Cataract Surgery; Teaching; Training; Learning 1. Introduction Modern cataract surgery is carried out through a micro- scope with 7 - 10× magnification. Dexterity is necessary as the surgeon’s hands and feet are constantly active during surgery (Figure 1). Developments in surgical technology and techniques have improved outcomes in terms of quality of vision and life, and increased safety has led to widened indica- tions and more operations performed [1]. Hence, in de- veloped societies patients expect their cataract operation to be painless and quick, with excellent outcome after a short period of recovery. Patients and health care systems also demand good accessibility. Surgeons therefore need to be trained in order to meet continuously growing de- mands and expectations. However, when an operation is performed by a trainee surgeon or a less experienced independent surgeon, there is a greater risk of surgical complications [2]. Complex ethical issues thus arise when teaching new surgeons, as Bernstein & Knifed point out regarding neurosurgery [3]. These issues are further emphasized by the fact that cataract surgery in almost 100% of cases is carried out nowadays under lo- cal anesthesia with ligh t or no sedation , allowing patien ts to be aware of surrounding activities and conversations during their operation. An ethical dilemma arises when, in order to make cataract surgery accessible to future (and larger numbers of) patients, and with present meth- ods for education of new surgeons, certain patients will undergo surgery under conditions that in many ways must be considered to be “high-risk environments”. For example, when the operation is performed by a surgeon with limited or no experience, assisted by a teaching surgeon who will try to communicate this to the trainee surgeon and staff in a way that causes as little alarm as possible is judged to be necessary. Several authors have discussed how to optimize training of surgeons in order to address these ethical issues and decrease the risk of complications [4-9]. As Henderson and Ali summarize, the trainees must master cognitive knowledge at the same time as they need to develop a spatial familiarity with the three-di- mensional surgical anatomy of the eye, coupled with sufficient technical dexterity to execute surgical ma- ne u v ers within a small space limited by sensitive structu r e s Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Application of Pedagogical Perspectives in the Teaching and Training of New Cataract Surgeons—A Literature-Based Essay 62 Figure 1. Surgeon’s position during modern cataract sur- gery is shown with one instrument in each hand, manipu- lating the intraocular tissues through incisions < 1 mm - 2.5 mm (inset top left). Left foot pedal controls the microscope zoom, focus and position in three dimensions; right foot pedal controls the phacoemulsification machine. [7]. Most literature on training cataract surgeons deals with the structural framework of training. Tests, surgical training facilities such as simulators and wet labs, and methods such as the delivery of graded responsibility and modular surgery have been described [4,5,7]. The peda- gogical perspectives that can be applied by the teaching surgeon during the various phases are not discussed to the same extent. The aim of this paper is to problematize the process of education and training of new surgeons, and by means of a literature search explore how awareness of different learning perspectives, teacher-student relationship mod- els, and possible pedagogical approaches can be of value in this process. 2. Materials and Methods Apart from own experience, personal communication and basic literature and papers within the field of pedagogical science and learning this essay is based upon a literature search performed using the National Library of Medicine PubMed (www.pubmed.gov) and the Education Re- sources Information Center (ERIC) databases. Search terms were “cataract surgery, microsurgery, surgery, lea- rning, teaching, training, learning perspectives”. Search results were reviewed and articles not relevant to the topic “surgical teaching” were excluded. 3. Learning Perspectives and Cataract Surgery Training Different learning perspectives can readily be identified within the process of training cataract surgeons. The be- havioristic persp ective is ev ident as regard s the surgeon’s ability to memorize and perform a predefined set of sur- gical maneuvers, which are repeated under supervision and refined by immediate negativ e and positive feedback from the supervisor [10]. Internal feedback is also im- portant: It is not difficult to imagine the frustration, dis- appointment or even dread that the trainee surgeon ex- periences when realizing—either by own observation or information from the teaching surgeon—that a complica- tion is imminent or has occurred. On the other hand, a surgical step successfully completed evokes a positive feeling. A cognitive perspective is also important. For example, the inner process of reflecting upon how surgical maneuvering must adjust to the anatomical relations in each specific case enables the surgeon, as experience increases during training, to anticipate and prevent com- plications [11]. During later stages of training, when the trainee surgeon operates on conscious patients and inter- acts with them as part of a surgical team, the contextual learning perspective is evident as well [12]. A schematic outline of the various steps in a training program for cataract surgery is shown in Table 1. 4. Teacher-Student Relationships and Cataract Surgery Training Selecting who is to enter the training program (Table 1) is sometimes the responsibility of the teaching surgeon, but trainee surgeons can also be chosen by clinic executives upon request (or without it) by an individual wishing to be trained as a surgeon. In some—but not all—countries, training in cataract surgery is a part of a general curricu- lum for specialist training. The risk of nepotism should not be ove rlooked if the teach ing surgeo n has infl uence on the selection. On the other hand, Gagliardi et al. found that an existing relationship appeared to be a key enabler of mentorship [13]. Selection mechanisms where the teach- ing surgeon has less influence might increase the risk of enrolling less determined or even less suitable candidates. When researching relationships between students pro- ducing scientific texts and their supervisors, Dysthe iden- tified three basic models [14]. 1) In the teaching model, a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Application of Pedagogical Perspectives in the Teaching and Training of New Cataract Surgeons—A Literature-Based Essay Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph 63 Table 1. Contents of the various stages of a cataract surgeon’s training program. Stage of training program Content Evaluation/Selection of trainees Acquisition of theoretical knowledge Clinical knowledge Complicating factors Patient selection criteria Surgical techniques Handling of equipment and instruments Motor skill training without patient presence “Dry” use of equipment (microscope, instruments, and machinery) Wet lab training Simulator training Clinical training with patient presence Observation of tutor performing surgery Step-wise execution of different surgical elements Selection of patients Complete surgery performed by trainee, tutor present Complete surgery performed by t rainee, tutor present only wh e n requested by trainee Independent surgery Stepwise increasing numbers of operations performed per working period Stepwi se increasing expected deg ree of surgical difficulty Continuing but decre as i n g need for consultation in difficult situations traditional teacher-pupil relationship with obvious hier- archical construction, the teacher has knowledge of the requirements for a successful project and the methods to attain the set goal, and conveys this knowledge to the student in a one-way communication. Being instrumental in the selection process puts the teaching surgeon in a higher hierarchical position and can lead to accentuation of the teacher-pupil relationship, at least at the beginning of the training program. 2) In the partnership model, tutor and student approach their task (e.g. trai ning of the st udent in gene ral, o r a specifi c su rgical case) as a joi nt project. 3) The apprenticeship model has been well-known in the surgical field since William Halsted refined the concept of how surgeons are trained through first observing how the tutor performs a task and then performing the task in the presence of the supervising tutor [15]. As in the teaching model, a strict hierarchy between the tutor and the trainee surgeon is obvious in the training situation, although in other aspects there ma y be a collegial, peer relati onship. In the medical field, the Halstedian approach is sometimes referred to as “see one, do one, teach one”. Not only does this expression mirror the fact that resource limitations force teaching to be done within a limited time frame, but it also reflects the accepted view that learning is achieved on a deeper level when performing a task instead of ob- serving, and even m ore so when the student in turn teaches others how to perform the task. The complex effect of taking a role as supervisor vis-à-vis a colleague or a peer (who in some aspects or fields m ay have a sup erior pos ition) has been discusse d by Denicolo [16]. As the specific relations above, as outlined by Dyst he, can be rather diffe rent fr om oth er rela tions a nd context between training and t eaching surgeon, power and responsibilities need to be balanced properly with regard to the surgical training situation. One of Denicolo’s in- formants points out the potential difficulty in delivering critical feedback accurately to a peer. The influence on the learning process exerted by the roles and relationships between teaching and trainee sur- geons is not a common topic in literature. Memon & Memon made a distinction between the roles of trainer and mentor, respectively, and identified a lack of formal mentorship programs and learner-support in surgical training [17]. A mentor should not only act as a surgical teacher, but according to Kay and Hinds also be “prepared to think about the broader aspects of people development and the factors that influence them in their daily work and choice of careers” [18]. Gagliardi et al. [13] investigated how mentorship format, delivery, and content influenced participation in and the impact of two programs for training specific surgical measures for breast cancer and rectal cancer. Their qualitative approach identified barri- ers, such as scheduling and financing, but also found that a key enabler was a pre-existing relation ship between men- tor and mentee. Learning perspectives and tutor-trainee relationship change and overlap as the trainee surgeon progresses through the different phases towards independence in surgery, as outlined in Table 1. These changes can be ins- tant, e.g. due to how an operation is prog ressing, or more long-term as the trainee acquires deeper knowledge and develops increased professional independence. It is im- portant to realize that these changes are not a one-way continuous develop ment, but instead th ere is commonly a mix, or a back-and-forth movement, between different perspectives and relationships. The teaching surgeon needs to be aware of when the trainee surgeon’s situation changes, and adapt the pedagogical framework accord- ingly in order to opt imize the learning . The next paragraph discusses how vari ous pers pectives com e into play in di ff- erent phases and situations during the training program. Initially the teacher-pupil relationship as described by  Application of Pedagogical Perspectives in the Teaching and Training of New Cataract Surgeons—A Literature-Based Essay 64 Dysthe is readily recognized, especially if the teaching surgeon is involv ed in the selection of new trainees [14]. This relationship can easily co ntinue into the next phase, the acquisition of theoretical knowledge, when the tea- ching surgeon gives advice about suitable sources of knowledge—books, clinical guidelines and preferred prac- tice pattern documents, user manuals, web-based sources, or courses. Although strategies and protoc ols for assessing that the trainee surgeon attains the learning objectives of this second phase have been described, systematic ap- proaches for this purpose are not generally implemented [5]. Instead, the training and teaching surgeon may commonly come to an agreement about when the learning goals have been achieved. This is also applicable to the third phase, when the trainee surgeon practices technical skills without patients present. Depending on the trainee surgeon’s progress, the relationship with the teaching surgeon may take the form of partnership but a teaching model may also be necessary depending on how much guidance the trainee surgeon needs during these earlier phases. Duri ng the fourt h phase, the app renticeship model for supervising comes into play, as the trainee surgeon first observes how the teaching surgeon performs the different parts of the operation, and with time progres- sively applies acquired theoretical and practical knowl- edge by performing increasingly complete, complex and competent surgical maneuvers on patients’ eyes [14]. 5. Merging of Motor Skills Training and Contextual Learning As the surgical training program progresses (Table 1), the teaching surgeon’s role becomes increasingly impor- tant for the final result. When, in the fourth phase, the surgical maneuvers are executed by the trainee surgeon on the eyes of real patients, the teacher needs to be alert and clear when instructing or correcting the trainee. The patient should be informed of the progress of the surgery without being worried by the teacher-trainee communi- cation. A common approach is modular training, where the trainee surgeon in the first cases only performs the simpler steps while the teacher carries out the more com- plicated parts [4]. As the trainee becomes comfortable with the easier steps, the more difficult parts are succes- sively introduced. Here it is easy to recognize the three major stages of the motor skill theory suggested by Fitts et al., with an initial cognitive phase, where the trainee surgeon reads, listens, watches images, video recordings, and live surgery and forms a mental picture of the per- formance of the procedure before starting to execute un- der close supervision—with more or less difficulty— more and more of the full procedure [19]. With practice and feedback from the supervisor the trainee surgeon enters the second stage of the motor skill theory, where the discrete components of the procedure are connected into a smooth chain of su rgical events th at constitu tes the complete operation, with fewer and fewer interruptions. In the autonomous third phase, the surgery is performed more and more automatically without the need for the surgeon to consciously focus on every movement in de- tail. The motor skills increase by repeating movements and evaluating their outcomes according to Schmidt’s schema theory of discrete motor skill learning, in which specific muscle commands aimed to produce a specified response from a defined starting point give sensory con- sequences (in cataract surgery mainly through visual and , to some extent, proprioceptive feedback), and a response outcome that is recognized and compared with the in- tended response [20]. In this process, structured feedback from the supervisor has been found to be important [21]. This should be kept in mind when implementing virtual reality methods for surgical training of motor skills, as has been suggested in the field of cataract surgery as well as other surgical specialities [22,23]. As mentioned ear- lier, structured forms for staging the training cataract surgeon’s technical skills have been described [5]. Such forms do not appear to be commonly implemented amo- ng Swedish teaching cataract surgeons (personal com- munication). When the surgical skills acquired by the trainee surgeon during the first three training phases (Table 1) are to be applied on a real patient, a whole new set of contextual capabilities and skills will be necessary. The trainee surgeon must focus not only on the specific surgical maneuvers, but also monitor and respond ade- quately to input from the patient as well as the teaching surgeon and operation room staff (Figure 2). The teach- ing surgeon must not only assess the surgical movements and their outcomes but also pay attention to the contex- tual learning perspective. Care must be taken to provide feedback and information in a manner that does not make the patient worried. A British teaching cataract surgeon anecdotally instructed a trainee surgeon to immediately stop the surgery at the moment the teacher uttered the word “Excellent!” Coded messages, or silent communi- cation with signs, are probably commonly used by teaching surgeons with the aim to minimize untoward anxiety and tension in the patient. The learning process is inhibited if the tension level of the trainee surgeon in- creases too much so also from a learning perspective it is important that the teaching surgeon’s feedback be con- veyed in a constructive, calm, and neutral manner [24]. 6. Adapting to Stages and Situations as the Trainee Surgeon Develops After stating the importance of effective mentoring in the development of surgeons at various levels, Memon & Memon highlighted the absence of true structure and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Application of Pedagogical Perspectives in the Teaching and Training of New Cataract Surgeons—A Literature-Based Essay 65 Figure 2. Schematic drawing of the contextual situation in the operation room, at the stage where trainee surgeon is performing the operation with teaching surgeon present. Assistant nurse, trainee surgeon and teaching surgeon are sterile. Scrub nurse is not sterile and may leave/enter the room upon request or stay during the whole procedure. Patient is awake and aware. Black single-lined arrows de- note communication with information and instructions, double-lined arrows denote orders. Continuous arrows in- dicate communication open (not necessarily understandable) to the patient. Dotted arrows indicate that the communica- tion is constructed, or “censored”, aimed at providing pa- tient information on a “need to know basis” and at the same time concealing information that would cause patient con- cern or anxiety. incentives for mentorship in training of surgeons [17]. How the teaching surgeon can optimize mentorship by navigating through the various learning perspectives and types of teacher-student relationship while the trainee surgeon gathers increased knowledge, skill and experi- ence has indeed not been a common topic in the medical literature. This lack of attention to developmental stages in higher education has also been addressed by Gardner [25]. In the field of organizational management, Hersey & Blanchard coined and explored the term “situational leadership” [26]. According to their theory, a leader’s behavior can be optimized by adapting to the task-relevant maturity of the person(s) subordinate to the leader. Al- though the validity of their theory has been challenged both theoretically and empirically, it has gained wide- spread popul arity and a pplication i n various e nvironm ents [27,28]. When applied to a surgical teaching paradigm (Figure 3), the task-relevant maturity of the student/ Figure 3. Schematic illustration of teaching concepts adapt- ed from the situational leadership model. The developmen- tal stages of the trainee surgeon (D1-D4, single line arrows and frames) are put into context with the matrix of the in- structive-directive and supportive teaching concepts (T1-T4, double line arrows and frames, italics). The beginner trainee surgeon has a high motivation but a low compe- tence level (D1). There is no need for the teacher to further motivate/support at this stage, but the emphasis is instead on instructive/directive teaching (T1). As difficulties are encountered, the self-confidence and motivation of the trainee surgeon decreases (D2), and the teacher needs to use a more motivating/supportive manner of teaching, while maintaining the instructive/directive emphasis (S2). Teach- ing concepts are adjusted analogously through development stages D3 and D4 (Adapted from Hershey & Blanchard [26]). learner can be divided into two factors—task maturity (capability of performing the operation) and psychologi- cal maturity (motivation level and confidence level). In the first maturity or development phase, D1, the learner has just entered the program, with a low level of compe- tence but a high de gree of m otivati on and c onfidence . The next phase, D2, is entered when initial difficulties and failures may cause severely decreased motivation and confidence in the learner. Task maturity is still low. As further exper ienced is gathered, com petence increases, but in the third stage, D3, motivation and co nfidence are still on a low level, slowing the further development of the learner who is reluctant to take on more advanced tasks. With correct support from the teacher, the learner’s mo- tivation and confidence may increase, which leads to the final stage of develo pment, D4, where t he learne r now h as high competence, motivation and confidence. The various stages are not passed in a one -way - o nly manner, but there may be discontinuous leaps and back-and-forth move- ments. The teacher needs to assess the trainee surgeon’s level of development through phases D1-D4 according to the matrix described above, and be flexible in order to tutor optimally. As outlined in Figure 3, two fundamental teaching concepts are applied: instructional/directive and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph  Application of Pedagogical Perspectives in the Teaching and Training of New Cataract Surgeons—A Literature-Based Essay Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph 66 Table 2. Learning perspectives, Teacher-learner relationships and situational leadership theory applications through the different phases of surgical training. Step in training program Learning perspective(s) Teacher-learner relationship(s) Stage(s) according to situational leadership theory Teacher’s approach(es) according to situational leadership theory Evaluation/Selection of trainees Not applicable Teaching model Not applicable Not applicable Acquisition of theoretical knowledge Cognitive Teaching model D1 T1 Practical training without patient presence Behavioristic, cognitive Master-apprentice model D1-D4 (modular ) T1-T4 (modular) Clinical training with patient presence Behavioristic, cognitive, contextual Master-apprentice model, partnership model D1-D4 T1-T4 Independent surgery Contextual, cognitive, behavioristic Partnership model D4 (D2-D3) T4 (T2-T3) supportive/contextual. Initially the learner has low com- petence but high motivation and therefore needs instruc- tion more than support (T1). In stage D2, there is a need for both instructive an d supportive tutoring (T2), while as competence is gained the supportive tutoring is much more important than instructio ns in stage D3. In the final stage, D4, the teacher offers less support and fewer in- structions as the trainee surgeon gains increasing inde- pendence based on sufficie nt com petence a nd c onfi dence. In the surgical teaching paradigm, the task of the teacher/ mentor now changes to more organizational supportive measures, that is, assist in providing suitable working schedules and finding a new role in the organization (Figure 3). 7. Summary The task of educating new cataract surgeons is necessary but also both ethically and pedagogically challenging. It is performed under increasingly demanding circum- stances. In Table 2, the complexity of the learning proc- ess for a trainee surgeon is evident, culminating as the training takes place in the operation room with actual patients. In order to make optimal use of available struc- tures for education such as literature, on-line resources, wet-lab facilities, simulators and patient-related activities, it can be beneficial for the teaching surgeon, the trainee surgeon and the patients as well that the teaching surgeon is aware of existing theories and concepts regarding learning and tutoring. This can improve the teaching surgeon’s ability to recognize how the situation changes for the trainee surgeon during the various phases, and adapt the teaching approach accordingly in order to op- timize the learning process. Studies concerning how teaching surgeons make use of various strategies during the phases that a trainee surgeon passes, and how these strategies work out, are warranted. REFERENCES [1] M. Lundström, U. Stenevi, P. Montan, A. Behndig and M. Kugelberg, “Swedish Cataract Surgery. Annual Report 2009 Based on Data From Swedish National Cataract Register,” 2013. http://www.cataractreg.com/Cataract_Sve/%C3%85rsrap port09.pdf [2] D. Artzen, M. Lundström, A. Behndig, U. Stenevi, E. Lydahl and P. Montan, “Capsule Complication during Cataract Surgery: Case-Control Study of Preoperative and Intraoperative Risk Factors. Swedish Capsule Rupture Study Group Report 2,” Journal of Cataract and Refrac- tive Surgery, Vol. 35, No. 10, 2009, pp. 1688-1693. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.05.026 [3] M. Bernstein and E. Knifed, “Ethical Challenges of In- the-Field Training: A Surgical Perspective,” Learning Inquiry, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2007, pp. 169-174. doi:10.1007/s11519-007-0010-4 [4] J. H. Smith, “Teaching Phacoemulsification in US Oph- thalmology Residencies: Can the Quality Be Main- tained?” Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2005, pp. 27-32. doi:10.1097/00055735-200502000-00005 [5] A. G. Lee, E. Greenlee, T. A. Oetting, H. A. Beaver, A. T. Johnson, et al., “The Iowa Ophthalmology Wet Labora- tory Curriculum for Teaching and Assessing Cataract Surgical Competency,” Ophthalmology, Vol. 114, No. 7, 2007, pp. e21-e26. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.051 [6] I. J. Dooley and P. D. O’Brien, “Subjective Difficulty of Each Stage of Phacoemulsification Cataract Surgery Per- formed By Basic Surgical Trainees,” Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2006, pp. 604- 608. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.045 [7] B. A. Henderson and R. Ali, “Teaching and Assessing Competence in Cataract Surgery,” Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2007, pp. 27-31.  Application of Pedagogical Perspectives in the Teaching and Training of New Cataract Surgeons—A Literature-Based Essay 67 doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e328010430e [8] G. Prakash, V. Jhanji, N. Sharma, K. Gupta, J. S. Titiyal and R. B. Vajpayee, “Assessment of Perceived Difficul- ties by Residents in Performing Routine Steps in Pha- coemulsification Surgery and in Managing Complica- tions,” Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 44, No. 3, 2009, pp. 284-287. doi:10.3129/i09-051 [9] E. S. Niemiec, K. L. Anderson, I. U. Scott and P. B. Greenberg, “Evidence-Based Management of Resident- Performed Cataract Surgery: An Investigation of Com- pliance with a Preferred Practice Pattern,” Ophthalmology, Vol. 116, No. 4, 2009, pp. 678-684. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.11.014 [10] B. F. Skinner, “Science and Human Behaviour,” Mac- Millan, New York, 1953. [11] J. Piaget, “Development and Learning,” Journal of Re- search in Science Teaching, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1964, pp. 176- 186. doi:10.1002/tea.3660020306 [12] J. Dewey, “Experience and Education,” Kappa Delta Pi, New York, 1938. [13] A. R. Gagliardi and F. C. Wright, “Exploratory Evalua- tion of Surgical Skills Mentorship Program Design and Outcomes,” Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2010, pp. 51-56. doi:10.1002/chp.20056 [14] O. Dysthe, “Professors as Mediators of Academic Text Cultures: An Interview Study With Advisors and Master’s Degree Students in Three Disciplines in a Norwegian University,” Written Communication, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2002, pp. 493-544. doi:10.1177/074108802238010 [15] J. L. Cameron, “William Stewart Halsted. Our Surgical Heritage,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 225, No. 5, 1997, pp. 445-458. doi:10.1097/00000658-199705000-00002 [16] P. Denicolo, “Doctoral Supervision of Colleagues: Peel- ing off the Veneer of Satisfaction and Competence,” Studies in Higher Education, Vol. 29, No. 6, 2004, pp. 694-707. doi:10.1080/0307507042000287203 [17] B. Memon and M. A. Memon, “Mentoring and Surgical Training: A Time for Reflection!” Advances in Health Sciences Education, Vol. 15, No. 5, 2010, pp. 749-754. doi:10.1007/s10459-009-9157-3 [18] D. Kay and R. Hinds, “A Practical Guide to Mentoring,” Howtobooks, Oxford, 2009. [19] P. M. Fitts and M. I. Posner, “Learning and Skilled Per- formance in Human Performance,” Brock-Cole, Belmont, 1967. [20] R. A. Schmidt, “Schema Theory of Discrete Motor Skill Learning,” Psychological Review, Vol. 82, No. 4, 1975, pp. 225-260. doi:10.1037/h0076770 [21] G. Ahlberg, O. Kruuna, C. E. Leijonmarck, J. Ovaska, A. Rosseland, et al., “Is the Learning Curve For Laparo- scopic Fundoplication Determined by the Teacher or the Pupil?” American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 189, No. 2, 2005, pp. 184-189. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.043 [22] D. L. Diesen, L. Erhunmwunsee, K. M. Bennett, K. Ben-David, B. Yurcisin, et al., “Effectiveness of Laparo- scopic Computer Simulator Versus Usage of Box Trainer For Endoscopic Surgery Training of Novices,” Journal of Surgical Education, Vol. 68, No. 4, 2011, pp. 282-289. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.02.007 [23] R. Källström, “Construction, Validation and Application of a Virtual Reality Simulator for the Training of Tran- surethral Resection of the Prostate,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Linköping University, Linköping, 2010. [24] H. H. Kaufman, R. L. Wiegand and R. H. Tunick, “Teaching Surgeons to Operate—Principles of Psycho- motor Skills Training,” Acta Neurochirurgica (Wien), Vol. 87, No. 1-2, 1987, pp. 1-7. doi:10.1007/BF02076007 [25] S. K. Gardner, “The Development of Doctoral Students: Phases of Challenge and Support: ASHE Higher Educa- tion Report,” Jossey Bass, San Francisco, 2009. [26] P. Hersey and K. Blanchard, “Managing Organizational Behavior,” Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1982. [27] C. L. Graeff, “The Situational Leadership Theory: A Critical Review,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1983, pp. 285-291. doi:10.5465/AMR.1983.4284738 [28] R. P. Vecchio, “Situational Leadership Theory: An Ex- amination of a Prescriptive Theory,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 72, No. 3, 1987, pp. 444-451. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.72.3.444 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJOph

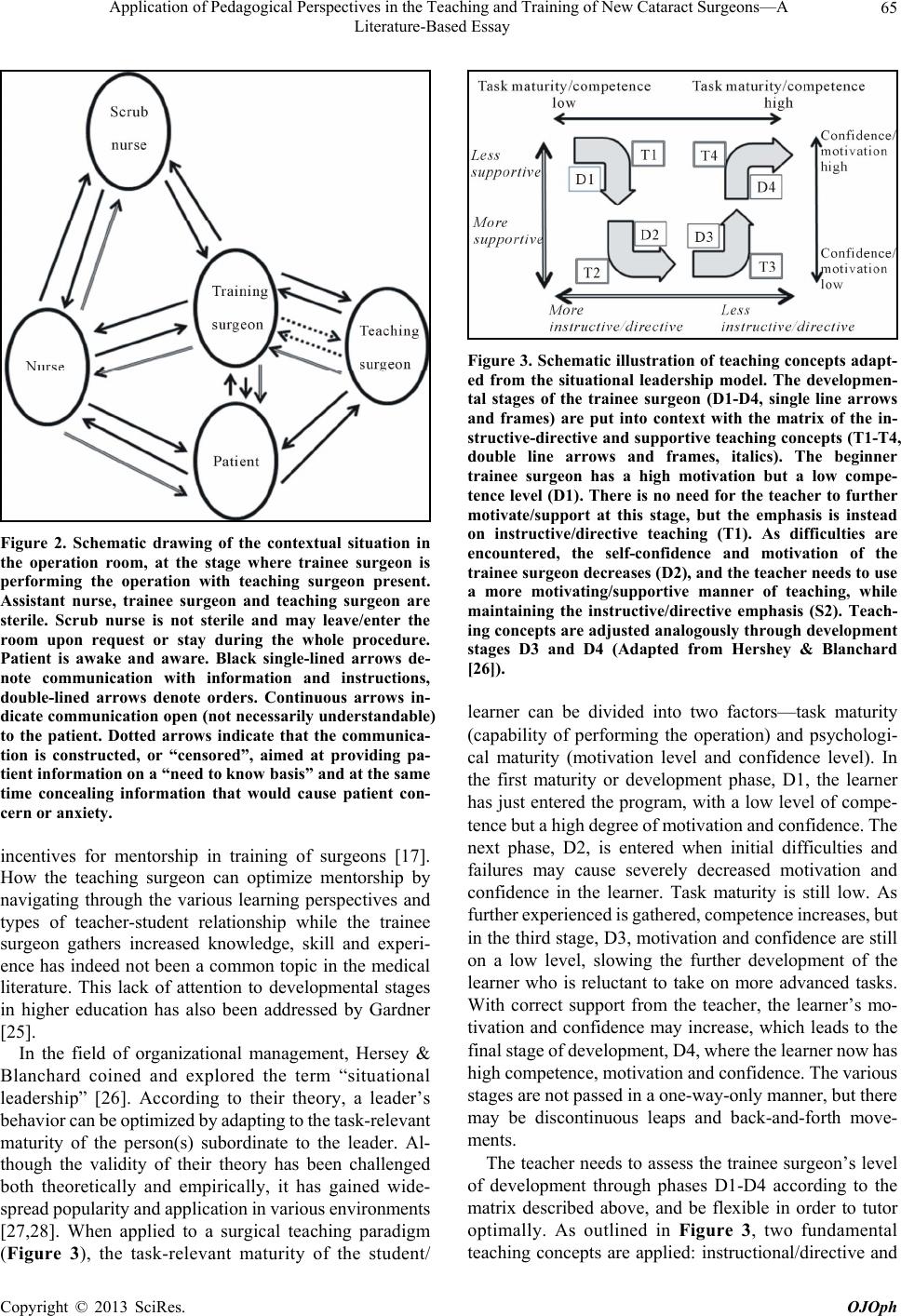

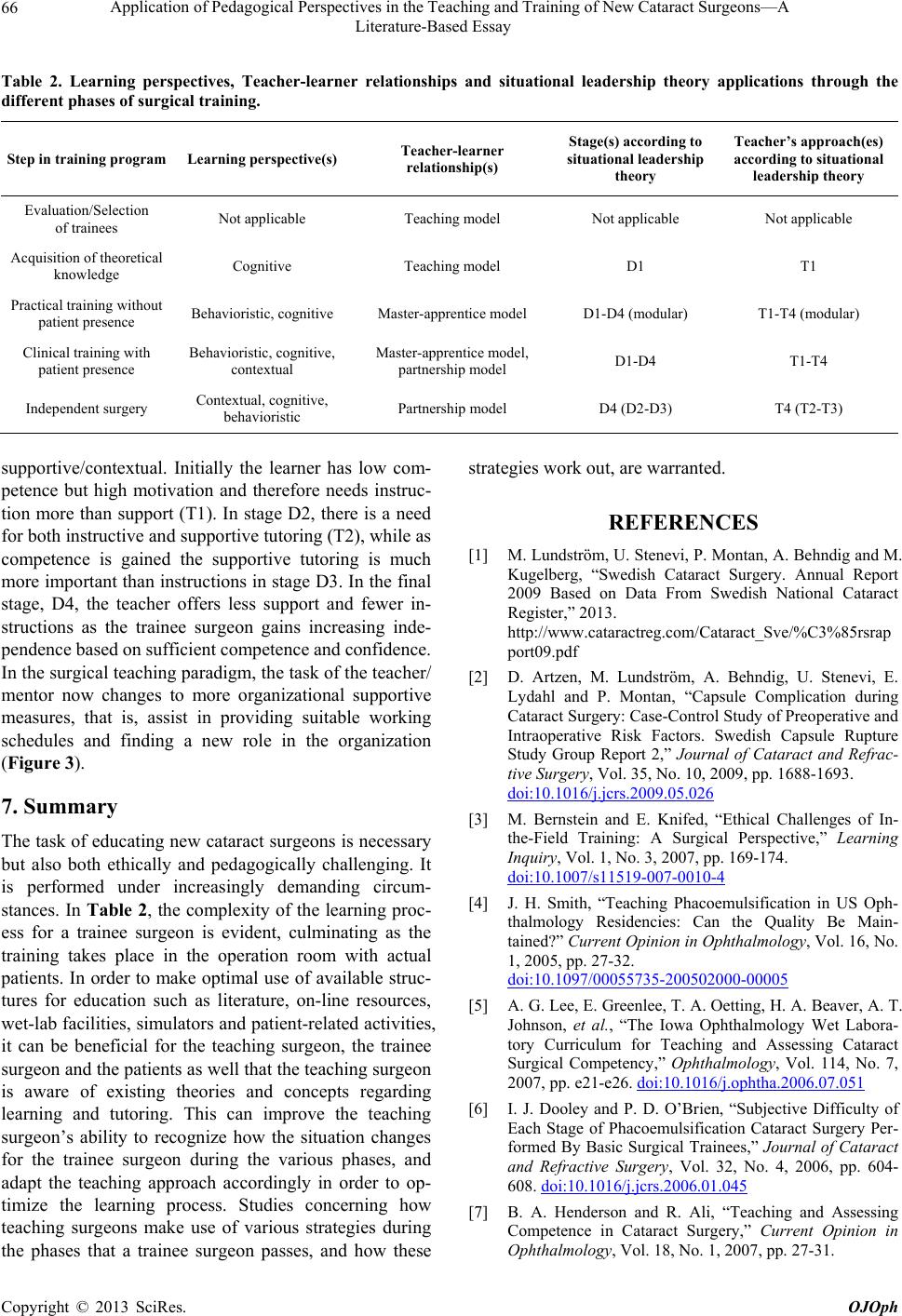

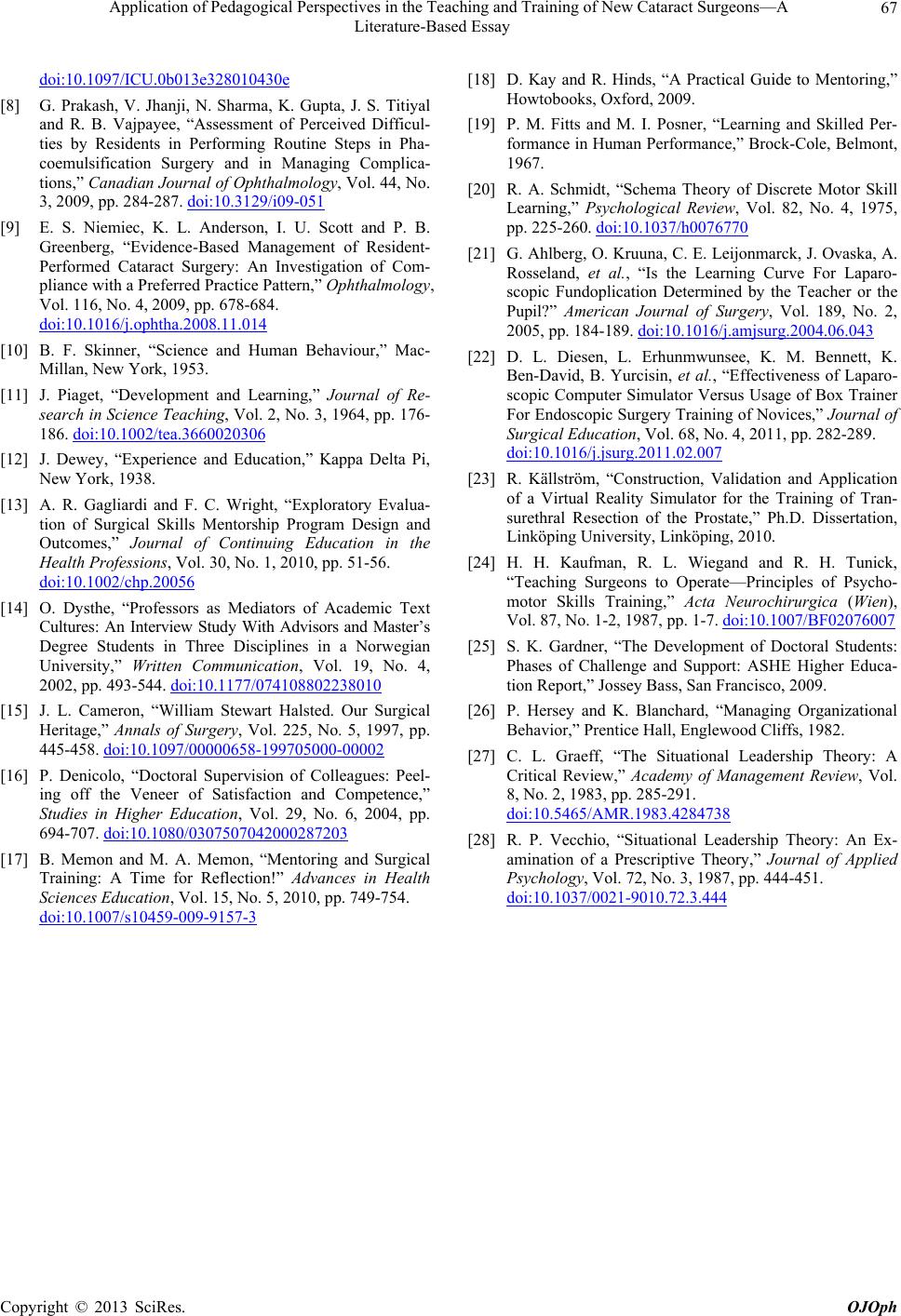

|