Paper Menu >>

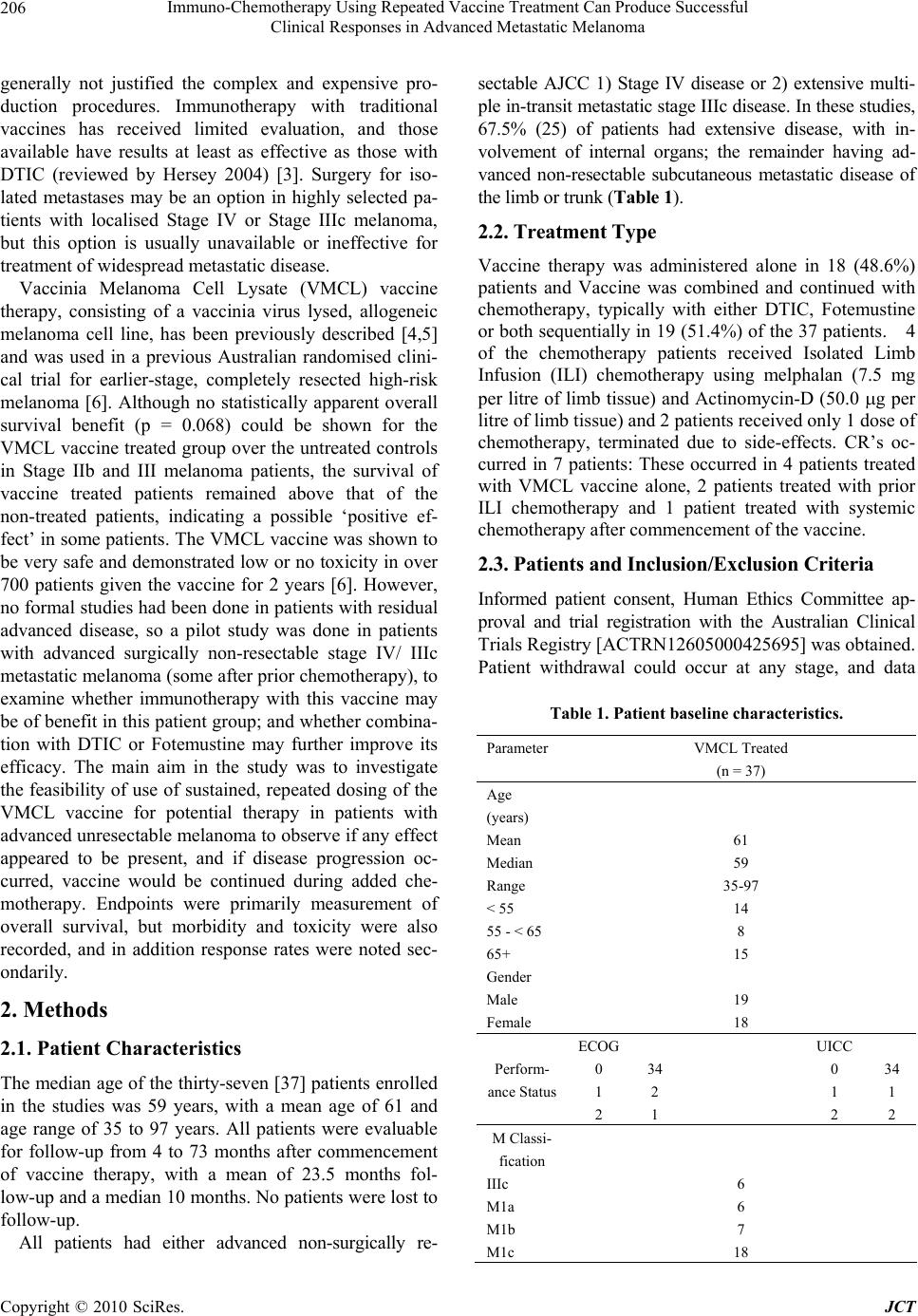

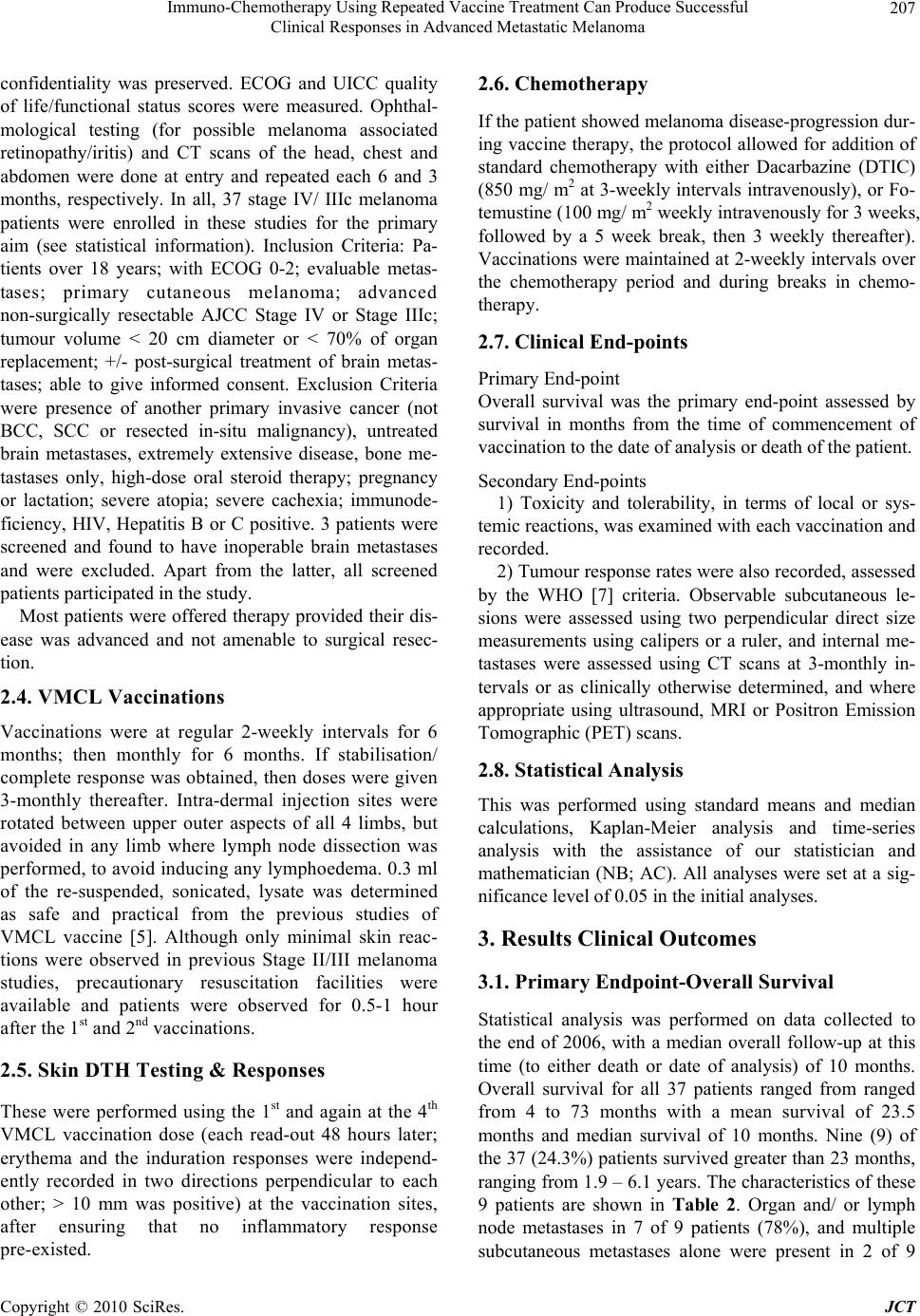

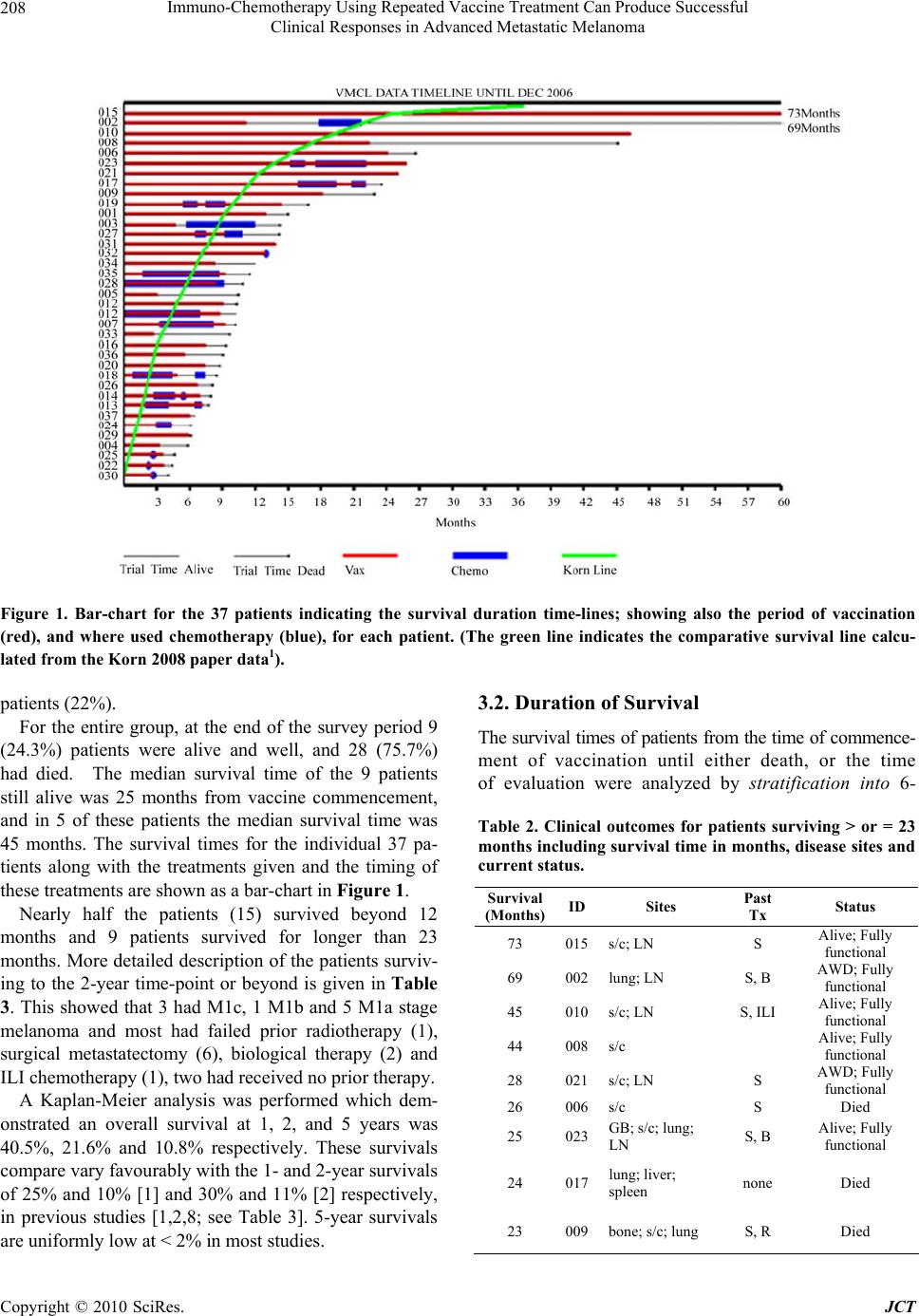

Journal Menu >>

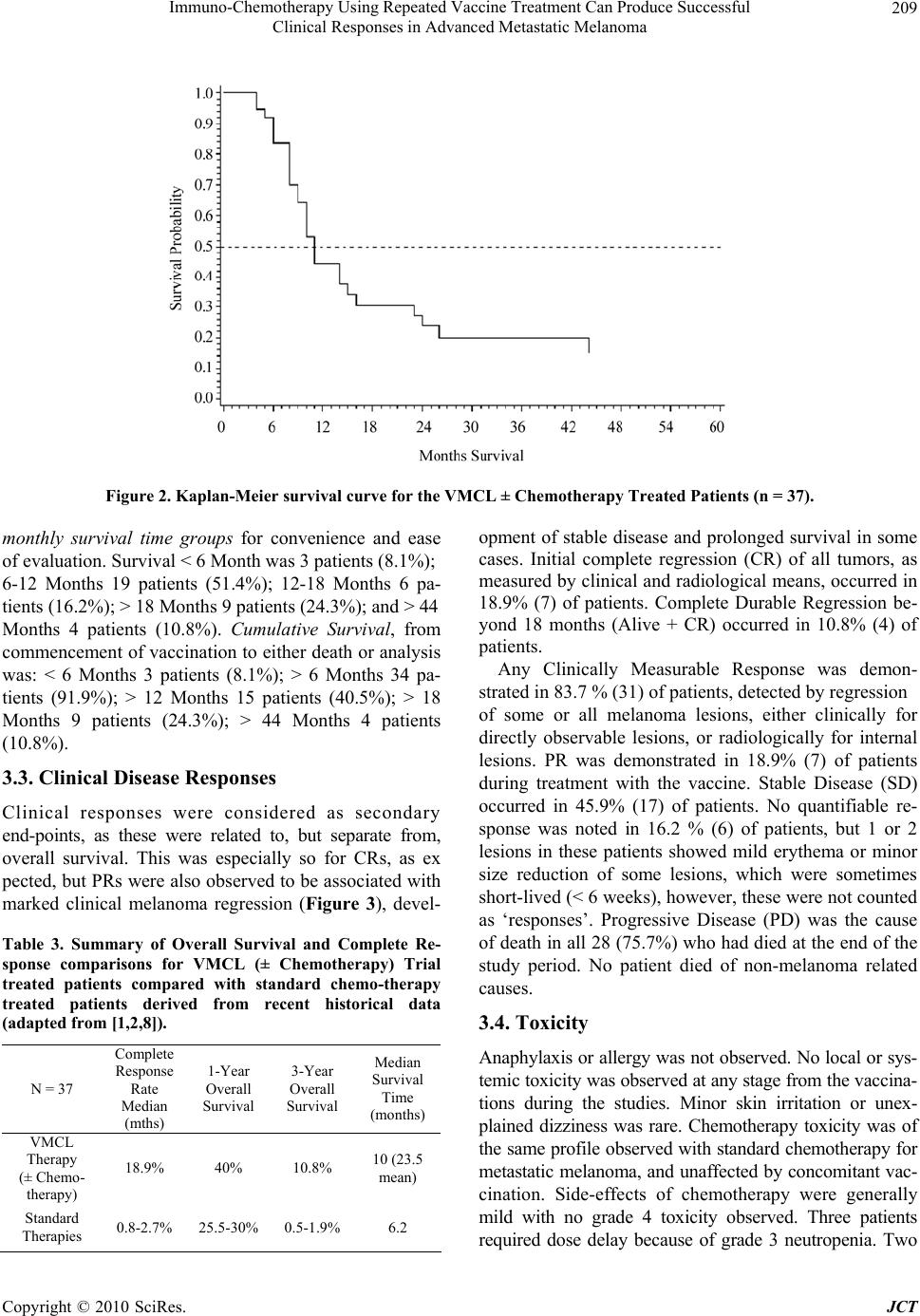

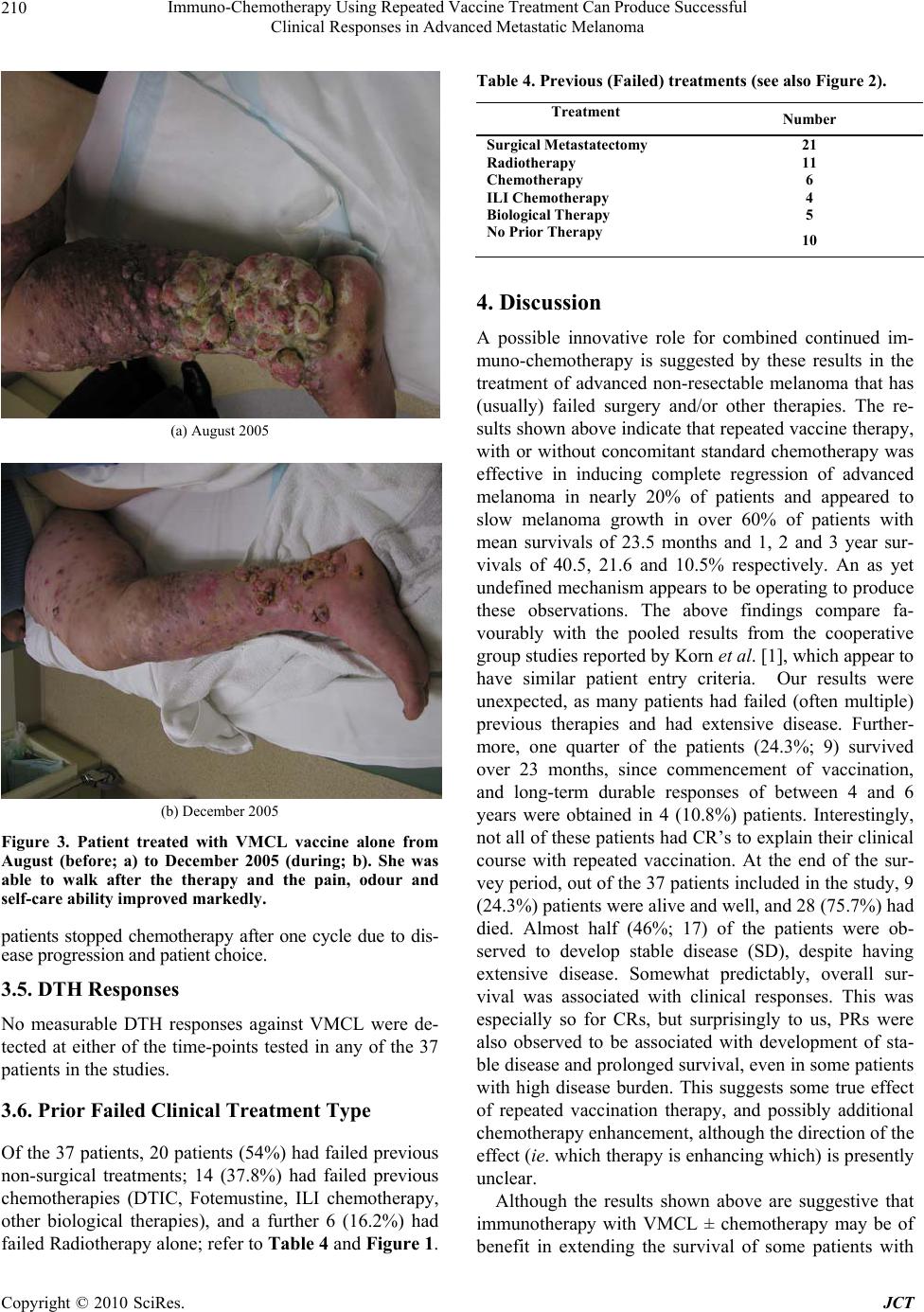

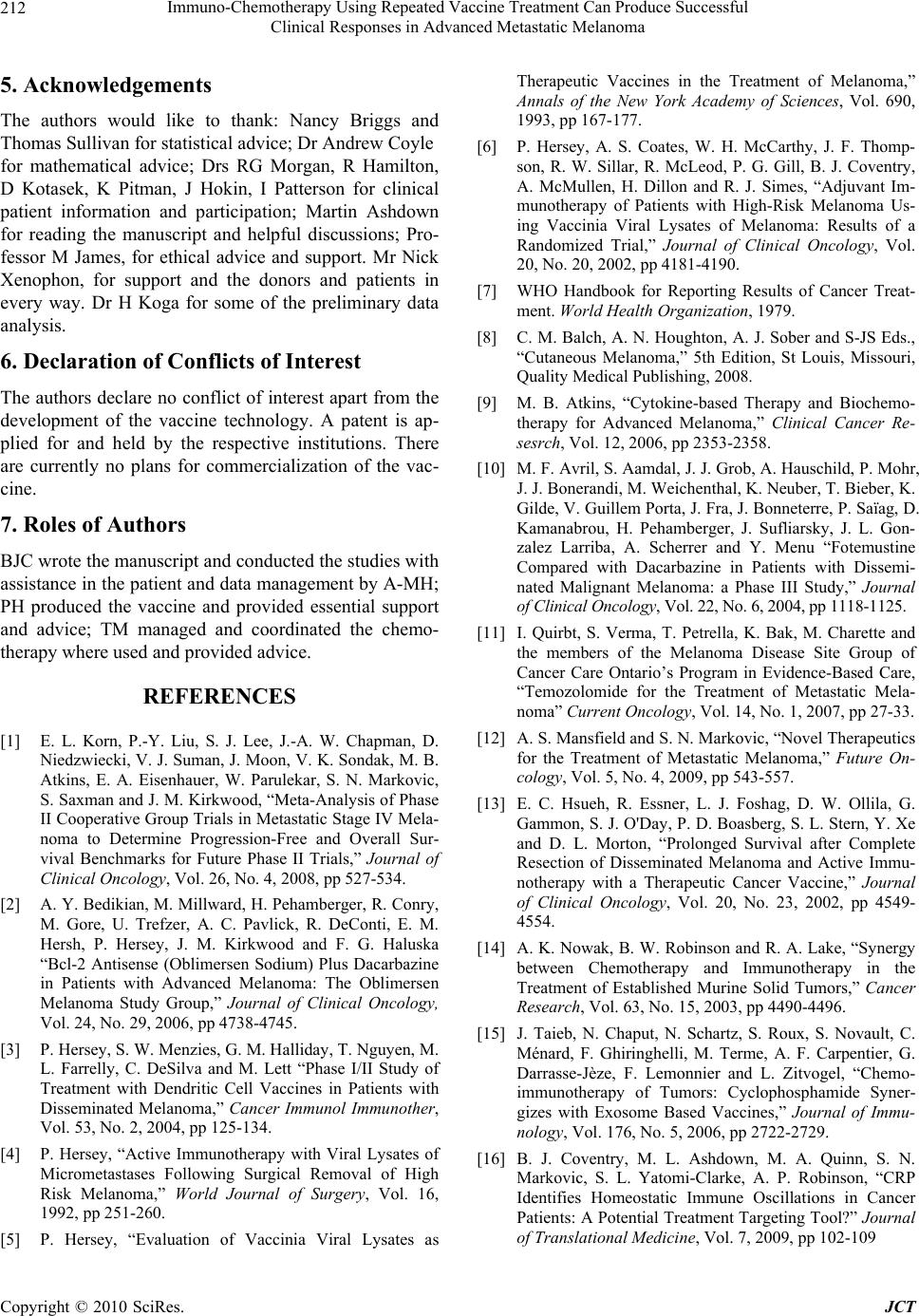

Journal of Cancer Therapy, 2010, 1, 205-213 doi:10.4236/jct.2010.14032 Published Online December 2010 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jct) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 205 Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Brendon J. Coventry1, Peter Hersey2, Anne-Marie Halligan1, Antonio Michele3 1Discipline of Surgery, University of Adelaide, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, Australia; 2Newcastle Melanoma Unit, Calvary Mater Newcastle and Medical Oncology and Immunology Unit, University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia; 3Medical Oncology, North Adelaide Oncology, Calvary Hospital, North Adelaide, Australia. Email: brendon.coventry@adelaide.edu.au, Peter.Hersey@newcastle.edu.au, T.michele@naonc.com.au, Anne-Marie.Halligan @health.sa.gov.au Received August 16th, 2010; revised September 10th, 2010; accepted 17th, 2010. ABSTRACT Advanced Stage IV and IIIc melanoma has a dismal survival, with or without, standard chemotherapy. New therapies are required to improve surviva l and redu ce mo rbid ity. Rep e ated va ccine do sing does not app ear to ha ve been explored, so Vaccinia Melanoma Cell Lysate (VMCL) vaccine repetitive therapy was tested, either alone, or combined with che- motherapy. 37 patients (31 Stage IV [M1a(6), b(7), c(18)] and 6 Stage IIIc) were studied using intra-dermal VMCL vaccine therapy. If disease progressed, vaccine was continued with standard chemotherapy (DTIC and/or Fotemustine). Overall survival was assessed and clinical responses were also recorded. From vaccine commencement, median overall follow-up was 10 months. Survivals ranged from 4 to 73 months. Median (mean) overall survival was 10 (23.5) months; overall survival at 1, 2 and 3 years was 40.5%, 21.6% and 10.8% respectively. CR and PR occurred in 18.9% (7) and 18.9% (7) of patients; these were durable for up to 6.1 years in 4 patients. Stable disease was noted in a further 17 pa- tients (45.9%). In 6 patients (16.2%) no response to therap y was apparent. Repeated vaccinatio ns with or without che- motherapy produced strong, durable clinical responses with overall survival > 23 months occurring in nearly 25% of advanced melanoma patients. The overall disease control rate (CR, PR and SD) was 83.7%, including CR in very ad- vanced cases. These results, in a largely unselected population of advanced metastatic melanoma patients, compare very favourably with other regimens, and notably were associated with minimal, if any, toxicity. Further analysis of this approach appears warranted. Keywords: Vaccine Therapy, Combined Immuno-Chemotherapy, Repetitive Do sing, Advanced Melanoma, Clinical Re sponses, Prolonged Survival 1. Introduction Current therapies for advanced disseminated melanoma or locally advanced disease remain seriously inadequate with typically poor clinical responses, high failure rates even when responses do occur, and options for any sub- sequent therapy are severely limited. Immunotherapy using vaccines has been used previously, but most stud- ies have not persisted with continued vaccinations when disease progression has occurred, and especially when chemotherapy is administered, typically using either Dacarbazine (DTIC) or Fotemustine, which are consid- ered as the standard treatment agents. These standard chemotherapy agents are often regarded as essentially palliative for ameliorating symptoms from metastases, but to our knowledge have seldom been tested with con- current vaccine or other immunotherapies, apart from the interferons. Despite trials and comparisons with a variety of other chemotherapeutic and biologic agents and com- binations of agents, little i mprovement has been possible upon standard agents. However, progression free surviv- als are usually less than 2 months with median overall survival from 6-9 months, with any form of systemic therapy. Percent survivals at 1-year in response to DTIC and a variety of agents is approximately 25% [1], how- ever this reduces substantially to < 2% at 2-5 years [2]. Immunotherapy with dendritic cell vaccines has been effective in a number of small studies, but results have  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 206 generally not justified the complex and expensive pro- duction procedures. Immunotherapy with traditional vaccines has received limited evaluation, and those available have results at least as effective as those with DTIC (reviewed by Hersey 2004) [3]. Surgery for iso- lated metastases may be an option in highly selected pa- tients with localised Stage IV or Stage IIIc melanoma, but this option is usually unavailable or ineffective for treatment of widespread metastatic disease. Vaccinia Melanoma Cell Lysate (VMCL) vaccine therapy, consisting of a vaccinia virus lysed, allogeneic melanoma cell line, has been previously described [4,5] and was used in a previous Australian randomised clini- cal trial for earlier-stage, completely resected high-risk melanoma [6]. Although no statistically apparent overall survival benefit (p = 0.068) could be shown for the VMCL vaccine treated group over the untreated controls in Stage IIb and III melanoma patients, the survival of vaccine treated patients remained above that of the non-treated patients, indicating a possible ‘positive ef- fect’ in some patients. The VMCL vaccine was shown to be very safe and demonstrated low or no toxicity in over 700 patients given the vaccine for 2 years [6]. However, no formal studies had been done in patients with residual advanced disease, so a pilot study was done in patients with advanced surgically non-resectable stage IV/ IIIc metastatic melanoma (some after prior chemotherapy), to examine whether immunotherapy with this vaccine may be of benefit in this patien t group; and whether combina- tion with DTIC or Fotemustine may further improve its efficacy. The main aim in the study was to investigate the feasibility of use of sustained, repeated dosing of the VMCL vaccine for potential therapy in patients with advanced unresectable melanoma to observe if any effect appeared to be present, and if disease progression oc- curred, vaccine would be continued during added che- motherapy. Endpoints were primarily measurement of overall survival, but morbidity and toxicity were also recorded, and in addition response rates were noted sec- ondarily. 2. Methods 2.1. Patient Characteristics The median age of the thirty-seven [37] patients enrolled in the studies was 59 years, with a mean age of 61 and age range of 35 to 97 years. All patients were evaluable for follow-up from 4 to 73 months after commencement of vaccine therapy, with a mean of 23.5 months fol- low-up and a median 10 months. No patients were lost to follow-up. All patients had either advanced non-surgically re- sectable AJCC 1) Stage IV disease or 2) extensive multi- ple in-transit metastatic stage IIIc disease. In these studies, 67.5% (25) of patients had extensive disease, with in- volvement of internal organs; the remainder having ad- vanced non-resectable subcutaneous metastatic disease of the limb or trunk (Table 1). 2.2. Treatment Type Vaccine therapy was administered alone in 18 (48.6%) patients and Vaccine was combined and continued with chemotherapy, typically with either DTIC, Fotemustine or both sequentially in 19 (51.4%) of the 37 patients. 4 of the chemotherapy patients received Isolated Limb Infusion (ILI) chemotherapy using melphalan (7.5 mg per litre of limb tissue) and Actinomycin-D (50.0 g per litre of limb tissue) and 2 patients received only 1 dose of chemotherapy, terminated due to side-effects. CR’s oc- curred in 7 patients: These occurred in 4 patients treated with VMCL vaccine alone, 2 patients treated with prior ILI chemotherapy and 1 patient treated with systemic chemotherapy after commencement of the vaccine. 2.3. Patients and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria Informed patient consent, Human Ethics Committee ap- proval and trial registration with the Australian Clinical Trials Registry [ACTRN126 05000425695] was obtained. Patient withdrawal could occur at any stage, and data Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics. Parameter VMCL Treated (n = 37) Age (years) Mean 61 Median 59 Range 35-97 < 55 14 55 - < 65 8 65+ 15 Gender Male 19 Female 18 ECOG UICC 0 34 0 34 1 2 1 1 Perform- ance Status 2 1 2 2 M Classi- fication IIIc 6 M1a 6 M1b 7 M1c 18  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 207 confidentiality was preserved. ECOG and UICC quality of life/functional status scores were measured. Ophthal- mological testing (for possible melanoma associated retinopathy/iritis) and CT scans of the head, chest and abdomen were done at entry and repeated each 6 and 3 months, respectively. In all, 37 stage IV/ IIIc melanoma patients were enrolled in these studies for the primary aim (see statistical information). Inclusion Criteria: Pa- tients over 18 years; with ECOG 0-2; evaluable metas- tases; primary cutaneous melanoma; advanced non-surgically resectable AJCC Stage IV or Stage IIIc; tumour volume < 20 cm diameter or < 70% of organ replacement; +/- post-surgical treatment of brain metas- tases; able to give informed consent. Exclusion Criteria were presence of another primary invasive cancer (not BCC, SCC or resected in-situ malignancy), untreated brain metastases, extremely extensive disease, bone me- tastases only, high-dose oral steroid therapy; pregnancy or lactation; severe atopia; severe cachexia; immunode- ficiency, HIV, Hepatitis B or C positive. 3 patients were screened and found to have inoperable brain metastases and were excluded. Apart from the latter, all screened patients participated in the study. Most patients were offered therapy provided their dis- ease was advanced and not amenable to surgical resec- tion. 2.4. VMCL Vaccinations Vaccinations were at regular 2-weekly intervals for 6 months; then monthly for 6 months. If stabilisation/ complete response was obtained, then doses were given 3-monthly thereafter. Intra-dermal injection sites were rotated between upper outer aspects of all 4 limbs, but avoided in any limb where lymph node dissection was performed, to avoid inducing any lymphoedema. 0.3 ml of the re-suspended, sonicated, lysate was determined as safe and practical from the previous studies of VMCL vaccine [5]. Although only minimal skin reac- tions were observed in previous Stage II/III melanoma studies, precautionary resuscitation facilities were available and patients were observed for 0.5-1 hour after th e 1st and 2nd vacc in a t ions. 2.5. Skin DTH Testing & Responses These were performed using the 1st and again at the 4th VMCL vaccination dose (each read-out 48 hours later; erythema and the induration responses were independ- ently recorded in two directions perpendicular to each other; > 10 mm was positive) at the vaccination sites, after ensuring that no inflammatory response pre-existed. 2.6. Chemotherapy If the patien t showed melanoma d isease-progression dur- ing vaccine therapy, the protocol allowed for addition of standard chemotherapy with either Dacarbazine (DTIC) (850 mg/ m2 at 3-weekly intervals intravenously), or Fo- temustine (100 mg/ m2 weekly intravenously for 3 weeks, followed by a 5 week break, then 3 weekly thereafter). Vaccinations were maintained at 2-weekly intervals over the chemotherapy period and during breaks in chemo- therapy. 2.7. Clinical End-points Primary End-point Overall survival was the primary end-point assessed by survival in months from the time of commencement of vaccination to the date of analysis or death of the patient. Secondary End-points 1) Toxicity and tolerability, in terms of local or sys- temic reactions, was examined with each vaccination and recorded. 2) Tumour response rates were also recorded, assessed by the WHO [7] criteria. Observable subcutaneous le- sions were assessed using two perpendicular direct size measurements using calipers or a ruler, and internal me- tastases were assessed using CT scans at 3-monthly in- tervals or as clinically otherwise determined, and where appropriate using ultrasound, MRI or Positron Emission Tomographic (PET) scans. 2.8. Statistical Analysis This was performed using standard means and median calculations, Kaplan-Meier analysis and time-series analysis with the assistance of our statistician and mathematician (NB; AC). All analyses were set at a sig- nificance level of 0.05 in the initial analyses. 3. Results Clinical Outcomes 3.1. Primary Endpoint-Overall Survival Statistical analysis was performed on data collected to the end of 2006, with a median overall follow-up at this time (to either death or date of analysis) of 10 months. Overall survival for all 37 patients ranged from ranged from 4 to 73 months with a mean survival of 23.5 months and median survival of 10 months. Nine (9) of the 37 (24.3%) patients survived greater than 23 months, ranging from 1.9 – 6.1 years. The characteristics of these 9 patients are shown in Table 2. Organ and/ or lymph node metastases in 7 of 9 patients (78%), and multiple subcutaneous metastases alone were present in 2 of 9  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 208 Figure 1. Bar-chart for the 37 patients indicating the survival duration time-lines; showing also the period of vaccination (red), and where used chemotherapy (blue), for each patient. (The green line indicates the comparative survival line calcu- lated from the Korn 2008 paper data1). patients (22%). For the entire group, at the end of the survey period 9 (24.3%) patients were alive and well, and 28 (75.7%) had died. The median survival time of the 9 patients still alive was 25 months from vaccine commencement, and in 5 of these patients the median survival time was 45 months. The survival times for the individual 37 pa- tients along with the treatments given and the timing of these treatments are shown as a bar-chart in Figure 1. Nearly half the patients (15) survived beyond 12 months and 9 patients survived for longer than 23 months. More detailed description of the patients surviv- ing to the 2-year time-point or beyond is given in Table 3. This showed that 3 had M1c, 1 M1b and 5 M1a stage melanoma and most had failed prior radiotherapy (1), surgical metastatectomy (6), biological therapy (2) and ILI chemotherapy (1), two had received no prior therapy. A Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed which dem- onstrated an overall survival at 1, 2, and 5 years was 40.5%, 21.6% and 10.8% respectively. These survivals compare vary favourably with the 1- and 2-year survivals of 25% and 10% [1] and 30% and 11% [2] respectively, in previous studies [1,2,8; see Table 3]. 5-year survivals are uniformly low at < 2% in most studies. 3.2. Duration of Survival The survival times of patients from the time of commence- ment of vaccination until either death, or the time of evaluation were analyzed by stratification into 6- Table 2. Clinical outcomes for patients surviving > or = 23 months including survival time in months, disease sites and current status. Survival (Months) ID Sites Past Tx Status 73 015s/c; LN S Alive; Fully functional 69 002lung; LN S, B AWD; Fully functional 45 010s/c; LN S, ILI Alive; Fully functional 44 008s/c Alive; Fully functional 28 021s/c; LN S AWD; Fully functional 26 006s/c S Died 25 023GB; s/c; lung; LN S, B Alive; Fully functional 24 017lung; liver; spleen none Died 23 009bone; s/c; lung S, R Died  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 209 Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the VMCL ± Chemotherapy Treated Patients (n = 37). monthly survival time groups for convenience and ease of evaluation. Survival < 6 Month was 3 pati ent s (8. 1% ); 6-12 Months 19 patients (51.4%); 12-18 Months 6 pa- tients (16.2%); > 18 Months 9 patients (24.3%); and > 44 Months 4 patients (10.8%). Cumulative Survival, from commencement of vaccination to either death or analysis was: < 6 Months 3 patients (8.1%); > 6 Months 34 pa- tients (91.9%); > 12 Months 15 patients (40.5%); > 18 Months 9 patients (24.3%); > 44 Months 4 patients (10.8%). 3.3. Clinical Disease Responses Clinical responses were considered as secondary end-points, as these were related to, but separate from, overall survival. This was especially so for CRs, as ex pected, but PRs were also observed to be associated with marked clinical melanoma regression (Figure 3), devel- Table 3. Summary of Overall Survival and Complete Re- sponse comparisons for VMCL (± Chemotherapy) Trial treated patients compared with standard chemo-therapy treated patients derived from recent historical data (adapted from [1,2,8]). N = 37 Complete Response Rate Median (mths) 1-Year Overall Survival 3-Year Overall Survival Median Survival Time (months) VMCL Therapy (± Chemo- therapy) 18.9% 40% 10.8% 10 (23.5 mean) Standard Therapies 0.8-2.7% 25.5-30% 0.5-1.9% 6.2 opment of stable disease and prolonged survival in some cases. Initial complete regression (CR) of all tumors, as measured by clinical and radiological means, occurred in 18.9% (7) of patients. Complete Durable Regression be- yond 18 months (Alive + CR) occurred in 10.8% (4) of patients. Any Clinically Measurable Response was demon- strated in 83.7 % (31) of patients, detected by regression of some or all melanoma lesions, either clinically for directly observable lesions, or radiologically for internal lesions. PR was demonstrated in 18.9% (7) of patients during treatment with the vaccine. Stable Disease (SD) occurred in 45.9% (17) of patients. No quantifiable re- sponse was noted in 16.2 % (6) of patients, but 1 or 2 lesions in these patients showed mild erythema or minor size reduction of some lesions, which were sometimes short-lived (< 6 weeks), ho wever, th ese were not counted as ‘responses’. Progressive Disease (PD) was the cause of death in all 28 (75.7%) who had died at the end of the study period. No patient died of non-melanoma related causes. 3.4. Toxicity Anaphylaxis or allergy was not observed. No local or sys- temic toxicity was observed at any stage from the vaccina- tions during the studies. Minor skin irritation or unex- plained dizziness was rare. Chemotherapy toxicity was of the same profile observed with standard chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma, and unaffected by concomitant vac- cination. Side-effects of chemotherapy were generally mild with no grade 4 toxicity observed. Three patients required dose delay because of grade 3 neutropenia. Two  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 210 (a) August 2005 (b) December 2005 Figure 3. Patient treated with VMCL vaccine alone from August (before; a) to December 2005 (during; b). She was able to walk after the therapy and the pain, odour and self-care ability improved markedly. patients stopped chemotherapy after one cycle due to dis- ease progression and patient choice. 3.5. DTH Responses No measurable DTH responses against VMCL were de- tected at either of the time-points tested in any of the 37 patients in the studies. 3.6. Prior Failed Clinical Treatment Type Of the 37 patients, 20 patients (54%) had failed previous non-surgical treatments; 14 (37.8%) had failed previous chemotherapies (DTIC, Fotemustine, ILI chemotherapy, other biological therapies), and a further 6 (16.2%) had failed Radiotherapy alone; refer to Table 4 and Figure 1. Table 4. Previous (Failed) treatments (see also Figure 2). Treatment Number Surgical Metastatectomy 21 Radiotherapy 11 Chemotherapy 6 ILI Chemotherapy 4 Biological Therapy 5 No Prior Therapy 10 4. Discussion A possible innovative role for combined continued im- muno-chemotherapy is suggested by these results in the treatment of advanced non-resectable melanoma that has (usually) failed surgery and/or other therapies. The re- sults shown above indicate that repeated vaccine therapy, with or without concomitant standard chemotherapy was effective in inducing complete regression of advanced melanoma in nearly 20% of patients and appeared to slow melanoma growth in over 60% of patients with mean survivals of 23.5 months and 1, 2 and 3 year sur- vivals of 40.5, 21.6 and 10.5% respectively. An as yet undefined mechanism appears to be operating to produce these observations. The above findings compare fa- vourably with the pooled results from the cooperative group studies reported by Korn et al. [1], which appear to have similar patient entry criteria. Our results were unexpected, as many patients had failed (often multiple) previous therapies and had extensive disease. Further- more, one quarter of the patients (24.3%; 9) survived over 23 months, since commencement of vaccination, and long-term durable responses of between 4 and 6 years were obtained in 4 (10.8%) patients. Interestingly, not all of these patients h ad CR’s to explain their clinical course with repeated vaccination. At the end of the sur- vey period, out of the 37 patients included in the study, 9 (24.3%) patients were alive and well, and 28 (75.7%) had died. Almost half (46%; 17) of the patients were ob- served to develop stable disease (SD), despite having extensive disease. Somewhat predictably, overall sur- vival was associated with clinical responses. This was especially so for CRs, but surprisingly to us, PRs were also observed to be associated with development of sta- ble disease and prolonged survival, even in some patients with high disease burden. This suggests some true effect of repeated vaccination therapy, and possibly additional chemotherapy enhancement, although the direction of the effect (ie. which therapy is enhan cing which) is pr esently unclear. Although the results shown above are suggestive that immunotherapy with VMCL ± chemotherapy may be of benefit in extending the survival of some patients with  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 211 melanoma, it is of course appreciated that interpreta- tion in smaller uncontrolled studies may be con- founded. However, the very fact that any patients could demonstrate prolonged survivals was remarkable, and that disease progression appeared to be halted, at least for some considerable time in some patients. Al- though inadvertent patient selection is difficult to completely exclude, nevertheless, over 2/3 of patients in the present study had much less favourable stage IV M1b/c disease and included a spectrum of patients with advanced disease. The importance of stage of disease on metastatic melanoma is well reported, for example in large patient groups, 1 and 2 year survivals for M1a disease were 54% and 36% respectively compared to 35% and 18% respectively for patients with M1c disease [8]. In addition, some patients had failed/ relapsed prior to entry and some had received two or more forms of prior therapy as shown in Table 4, where surgical metastatectomy included local and organ metastatic disease resections; prior chemotherapy was standard systemic therapy and/or ILI chemotherapy; biological trial therapies included IL-18; Canvaxin; NY-ESO-1; Interferon; and P-188 therapy. The standard use of dacarbazine (DTIC) and Fote- mustine, and in some countries multi-dose regimens, have not been able to substantially alter the survival of advanced metastatic melanoma, and are regarded as essentially ‘palliative’. Despite hope that interleukins, interferons and other bio-therapeutic agents would improve outcome, this has not proved to be the case, and are often limited by significant toxicity [9]. Prior studies with both DTIC and Fotemustine alone have reported response rates of 5-15%, and complete re- sponse rates of 0.8-2.7% with median survival times of 5-8 months in patients with advanced melanoma. No benefit was observed with multi-agent over single agent chemotherapy [10-12]. Korn [1] in a me ta-an alysis of 42 phase 2 trials involving 2027 patients reported a me- dian survival time of 6.2 months (95% CI; 5.9-6.5 months). Percent survival at 1-year was 25.5%. Be- dikian [2] reported that DTIC induced a median sur- vival of 7.8 months and approximately a 30% 1-year survival. Overall response was 7.5% and a 0.8% com- plete response rate in 395 patients. In the present studies we observed that 15 patients (40.5%) survived 12 months or more. Our observed initial complete re- sponse rate (CR) of all clinical and radiological tu- mour was 18.9% (7) of patients. This remained durable beyond 18 months (Alive + CR) in 10.8% (4) of pa- tients. Any Clinically Measurable Response was demonstrated in 83.7% (31) of patients despite many of these patients had already failed standard (multiple) therapies before entry to our study. A potentially significant point of difference between this and previous studies is that we chose to continue regular vaccine administration for a long time period irrespective of continued tumor growth [13]. Furthermore, we also continued repeated VMCL vaccination during any chemotherapy delivery, rather than stopping vacci- nation entirely or even temporarily, as others have done in the past. Whether DTIC (or f ot emust ine) added subs t a nt ially to the benefit of immunotherapy, or the reverse was true, is not clear from this limited study, but it is our impres- sion that combined vaccine and chemotherapy in pa- tients with progressive disease enhanced the clinical effectiveness and importantly was capable of producing either CR or stable disease, with the net effect of pro- longing overall survival. The combined additive effect of vaccine and chemotherapy might be explained by either increased antigen release due to chemotherapy, or ablation of T-regulatory cells by chemotherapy or both [14,15]. The timing of the administration of the VMCL Vaccine and/ or chemotherapy may be of importance in determining the clinical outcome and is the subject of on-going studies [16,17]. Previous work has shown that intra-tumoural dendritic cell (DC) numbers or poor DC activation/ presentation may play a significant role in directing the anti-tumor response and outcome [18-24], perhaps through T-cell immunosuppression [25-28]. The T-effector cells and T-regulatory cell balance in the tumour microenvironment is of likely critical impor- tance in determining outcome in a variety of cancers [29-34] and further studies are needed to examine these aspects. In summary, treatment with the VMCL Vaccine has proven to be safe, with no or very low toxicity, and appears to induce significant improvement in overall survival in some 40% of patients with advanced mela- noma. It is capable of inducing complete regression of melanoma, and some of these are durable for long pe- riods, extending to over 6 years. Stable disease can be induced with or without partial responses in some le- sions. If disease progresses, the VMCL vaccine can be safely combined and continued with standard chemo- therapy using DTIC or fotemusine, and this has added to its effectiveness in a number of patients. The tu- mour growth modulation producing resolution, regres- sion, and stabilization of melanoma deposits in pa- tients, is likely due to immunomodulation due to re- peated dosing of vaccine continuously with or without concurrent chemotherapy. Further evaluation of com- bined vaccine and chemotherapy in a randomized trial appears warranted.  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 212 5. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank: Nancy Briggs and Thomas Sullivan for statistical advice; Dr Andrew Coyle for mathematical advice; Drs RG Morgan, R Hamilton, D Kotasek, K Pitman, J Hokin, I Patterson for clinical patient information and participation; Martin Ashdown for reading the manuscript and helpful discussions; Pro- fessor M James, for ethical advice and support. Mr Nick Xenophon, for support and the donors and patients in every way. Dr H Koga for some of the preliminary data analysis. 6. Declaration of Conflicts of Interest The authors declare no conflict of interest apart from the development of the vaccine technology. A patent is ap- plied for and held by the respective institutions. There are currently no plans for commercialization of the vac- cine. 7. Roles of Authors BJC wrote the manuscript and conducted the studies with assistance in the patient and data management by A-MH; PH produced the vaccine and provided essential support and advice; TM managed and coordinated the chemo- therapy where used and provided advice. REFERENCES [1] E. L. Korn, P.-Y. Liu, S. J. Lee, J.-A. W. Chapman, D. Niedzwiecki, V. J. Suman, J. Moon, V. K. Sondak, M. B. Atkins, E. A. Eisenhauer, W. Parulekar, S. N. Markovic, S. Saxman and J. M. Kirkwood, “Meta-Analysis of Phase II Cooperative Group Trials in Metastatic Stage IV Mela- noma to Determine Progression-Free and Overall Sur- vival Benchmarks for Future Phase II Trials,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2008, pp 527-534. [2] A. Y. Bedikian, M. Millward, H. Pehamberger, R. Conry, M. Gore, U. Trefzer, A. C. Pavlick, R. DeConti, E. M. Hersh, P. Hersey, J. M. Kirkwood and F. G. Haluska “Bcl-2 Antisense (Oblimersen Sodium) Plus Dacarbazine in Patients with Advanced Melanoma: The Oblimersen Melanoma Study Group,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 24, No. 29, 2006, pp 4738-4745. [3] P. Hersey, S. W. Menzies, G. M. Halliday, T. Nguyen, M. L. Farrelly, C. DeSilva and M. Lett “Phase I/II Study of Treatment with Dendritic Cell Vaccines in Patients with Disseminated Melanoma,” Cancer Immunol Immunother, Vol. 53, No. 2, 2004, pp 125-134. [4] P. Hersey, “Active Immunotherapy with Viral Lysates of Micrometastases Following Surgical Removal of High Risk Melanoma,” World Journal of Surgery, Vol. 16, 1992, pp 251-260. [5] P. Hersey, “Evaluation of Vaccinia Viral Lysates as Therapeutic Vaccines in the Treatment of Melanoma,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 690, 1993, pp 167-177. [6] P. Hersey, A. S. Coates, W. H. McCarthy, J. F. Thomp- son, R. W. Sillar, R. McLeod, P. G. Gill, B. J. Coventry, A. McMullen, H. Dillon and R. J. Simes, “Adjuvant Im- munotherapy of Patients with High-Risk Melanoma Us- ing Vaccinia Viral Lysates of Melanoma: Results of a Randomized Trial,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 20, No. 20, 2002, pp 4181-4190. [7] WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treat- ment. World Health Organization, 1979. [8] C. M. Balch, A. N. Houghton, A. J. Sober and S-JS Eds., “Cutaneous Melanoma,” 5th Edition, St Louis, Missouri, Quality Medical Publishing, 2008. [9] M. B. Atkins, “Cytokine-based Therapy and Biochemo- therapy for Advanced Melanoma,” Clinical Cancer Re- sesrch, Vol. 12, 2006, pp 2353-2358. [10] M. F. Avril, S. Aamdal , J. J. Grob, A. Hauschild, P. Mohr, J. J. Bonerandi, M. Weichenthal, K. Neuber, T. Bieber, K. Gilde, V. Guillem Porta, J. Fra, J. Bonneterre, P. Saïag, D. Kamanabrou, H. Pehamberger, J. Sufliarsky, J. L. Gon- zalez Larriba, A. Scherrer and Y. Menu “Fotemustine Compared with Dacarbazine in Patients with Dissemi- nated Malignant Melanoma: a Phase III Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2004, pp 1118-1125. [11] I. Quirbt, S. Verma, T. Petrella, K. Bak, M. Charette and the members of the Melanoma Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-Based Care, “Temozolomide for the Treatment of Metastatic Mela- noma” Current Oncology, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2007, pp 27-33. [12] A. S. Mansfield and S. N. Markovic, “Novel Therapeutics for the Treatment of Metastatic Melanoma,” Future On- cology, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2009, pp 543-557. [13] E. C. Hsueh, R. Essner, L. J. Foshag, D. W. Ollila, G. Gammon, S. J. O'Day, P. D. Boasberg, S. L. Stern, Y. Xe and D. L. Morton, “Prolonged Survival after Complete Resection of Disseminated Melanoma and Active Immu- notherapy with a Therapeutic Cancer Vaccine,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 20, No. 23, 2002, pp 4549- 4554. [14] A. K. Nowak, B. W. Robinson and R. A. Lake, “Synergy between Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Established Murine Solid Tumors,” Cancer Research, Vol. 63, No. 15, 2003, pp 4490-4496. [15] J. Taieb, N. Chaput, N. Schartz, S. Roux, S. Novault, C. Ménard, F. Ghiringhelli, M. Terme, A. F. Carpentier, G. Darrasse-Jèze, F. Lemonnier and L. Zitvogel, “Chemo- immunotherapy of Tumors: Cyclophosphamide Syner- gizes with Exosome Based Vaccines,” Journal of Immu- nology, Vol. 176, No. 5, 2006, pp 2722-2729. [16] B. J. Coventry, M. L. Ashdown, M. A. Quinn, S. N. Markovic, S. L. Yatomi-Clarke, A. P. Robinson, “CRP Identifies Homeostatic Immune Oscillations in Cancer Patients: A Potential Treatment Targeting Tool?” Journal of Translational Medicine, Vol. 7, 2009, pp 102-109  Immuno-Chemotherapy Using Repeated Vaccine Treatment Can Produce Successful Clinical Responses in Advanced Metastatic Melanoma Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 213 [17] M. L. Ashdown and B. J. Coventry “A Matter of Time,” Australasian Science, Vol. 5, 2010, pp 18-20. [18] B. J. Coventry, J. M. Austyn, S. Chryssidis, D. Hankins and A. Harris, “Identification and Isolation of CD1a Posi- tive Putative Tumour Infiltrating Dendritic Cells in Hu- man Breast Cancer,” Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Vol. 417, 1997, pp 571-577. [19] B. J. Coventry, “CD1a-Positive Putative Tumour Infil- trating Dendritic Cells in Human Breast Cancer” Anti- cancer Research, Vol. 19(4B), 1999, pp 3183-3187. [20] E. E. Hillenbrand, A. M. Neville and B. J. Coventry, “Immunohistochemical Localization of CD1a-positive Putative Dendritic Cells in Human Breast Tumours,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 79 No. 5-6, 1999, pp 940-944. [21] B. J. Coventry, P. L. Lee, D. Gibbs and D. N. Hart, “Den- dritic Cell Density and Activation Status in Human Breast Cancer — CD1a, CMRF-44, CMRF-56 and CD-83 Ex- pression,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 86, No. 4, 2002, pp 546-551. [22] A. H. Barbour and B. J. Coventry, “Dendritic Cell Den- sity and Activation Status of Tumour Infiltrating Lym- phocytes in Metastatic Human Melanoma: Possible Im- plications for Sentinel Node Metastases,” Melanoma Re- search, Vol. 13, No.3, 2003, pp 263-269. [23] B. J. Coventry and J. Morton, “CD1a-positive Infiltrat- ing-dendritic Cell Density and 5-year Survival from Hu- man Breast Cancer,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 89, No. 3, 2003, pp 533-538. [24] N. Chaput, G. Darrasse-Jèze, A. S. Bergot, C. Cordier, S. Ngo-Abdalla, D. Klatzmann, “Azogui O Regulatory T cells prevent CD8 T Cell Maturation by Inhibiting CD4 Th cells at Tumor Sites,” Journal of Immunology, Vol. 179, No. 8, 2007, pp 4969-4978. [25] S. Nizar, J. Copier, B. Meyer, M. Bodman-Smith, C.Galustian, D. Kumar and A. Dalgleish, “T-regulatory Cell Modulation: The Future of Cancer Immunotherapy?” Minireview British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 100, 2009, pp 1697-1703. [26] H. Y. Wang and R. F. Wang, “Regulatory T cells and Cancer," Current Opinion in Immunology, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2007, pp. 217-223. [27] B. J. Coventry, S. C. Weeks, S. E. Heckford, P. J. Sykes, J. Bradley a nd J. M. Skinner, “Lack of IL-2 Cytokine Ex- pression despite Il-2 Messenger RNA Transcription in Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Primary Human Breast Carcinoma: Selective Expression of Early Activa- tion Markers,” Journal of Immunology, Vol. 156, No. 9, 1996, pp 3486-3492. [28] B. Coventry and S. Heinzel, “CD1a in Human Cancers: A New Role for an Old Molecule,” Trends in Immunology. Vol. 25, No. 5, 2004, pp 242-248. [29] N. G. Chakraborty, S. Chattopadhyay, S. Mehrotra, A. Chhabra and B. Mukherji, “Regulatory T-cell Response and Tumor Vaccine-Induced Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes in Human Melanoma,” Human Immunology, Vol. 65, No. 8, 2004, pp 794-802. [30] M. Ahamadzadeh and S. A. Rosenberg, “IL-2 Increases CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells in Cancer Pa- tients,” Blood, Vol. 107, No. 6, 2006, pp 2409-2414. [31] D. K. Sojka, Y. H. Huang and D. J. Fowell “Mechanisms of Regulatory T-cell Suppression - a Diverse Arsenal for a Moving Target,” Review Immunology, Vol. 124, No. 1, 2008, pp. 13-22. [32] G. Darrasse-Jèze, A. S. Bergot, A. Durgeau, F. Billiard, B. L. Salomon, J. L. Cohen, B. Bellier, K. Podsypanina and D. Klatzmann, “Tumor Emergence is Sensed by Self-specific CD44hi Memory Tregs that Create a Domi- nant Tolerogenic Environment for Tumors in Mice,” Journal of Clinical Investigation, Vol. 119, No. 9, 2009, pp 2648-2662. [33] G. Darrasse-Jèze, S. Deroubaix, H. Mouquet, D. Victora, T. Eisenreich, K. H. Yao, R. F. Masilamani, M. L. Dustin, A. Rudensky, K. Liu and M. C. Nussenzweig, “Feedback Control of Regulatory T Cell Homeostasis by Dendritic Cells in Vivo,” Journal of Experimental Medicine, Vol. 206, No. 9, 2009, pp 1853-1862. [34] L. Zitvogel and G. Kroemer, “Anticancer Immuno- chemotherapy Using Adjuvants with Direct Cytotoxic Effects,” Journal of Clinical Investigation, Vol. 119, No. 8, 2009, pp 2127-2130. |