Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.8, 514-520 Published Online August 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.48075 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 514 Autism Spectrum, Attachment Styles, and Social Skills in University Student Junichi Takahashi1, Koju Tamaki2, Nozomi Yamawaki3 1Department of Developmental Disorders, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, Japan 2Department Graduate School of Human Development and Culture, Fukushima University, Fukushima-Shi, Fukushima, Japan 3Graduate School of Psychology and Human Development, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan Email: j_taka@ncnp.go.jp Received June 6th, 2013; revised July 6th, 2013; accepted July 13th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Junichi Takahashi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Com- mons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, pro- vided the original work is properly cited. We investigated the relationships between Autism-spectrum Quotient (AQ) scores, adult attachment style (as assessed by the Internal Working Model [IWM] scale) scores, and social skills (as assessed by Kiku- chi’s Scale of Social Skills [KiSS-18]) in university students who had no diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (N = 468). The AQ consists of five subscales: social skills, local details, attention switching, communication, and imagination. The IWM is composed of three subscales: secure, anxious, and avoidant attachment styles. The KiSS-18 is a single-factor model. First, we calculated the correlations between AQ, IWM, and KiSS-18 scores. Next, we examined the differences in each subscale score of the IWM be- tween two groups defined by their AQ scores (High and Low AQ groups). We found that the High AQ had higher scores on the IWM secure subscale than did the Low AQ group. In addition, the High AQ group had lower scores on the IWM anxious and avoidant subscales than did the Low AQ group. More- over, in the High AQ group, the secure style, but not the anxious and avoidant styles, modulated the KiSS-18 scores. The results of the present study add to existing knowledge of the relationships between autism spectrum tendency, adult attachment style, and social skills, and suggested that adult attachment styles (particularly the secure style) may play the role of mediator of social skill ability. Keywords: Autism-Spectrum Quotient; Adult Attachment Style; Social Skill Introduction According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision; DSM-IV-TR, 2000), autism spectrum disorders are developmental disorders charac- terized by deficits of social interaction, communication, and a restricted range of interests. Those with an autism spectrum dis- order frequently exhibit deficits of social skills or social inter- action (Laushey & Heflin, 2000). In order to examine the deficits of social skills in autism, an approach focusing on attachment problems has been used (Mu- kaddes, Kaynak, Kinali, Besikci, & Issever, 2004). Attachment is an affective connection that is typically developed through interactions between children and a mother figure (Bowlby, 1969). Attachment relationships provide an internal representa- tion (internal working model [IWM]) that shows how others in- teract with the individual. People often derive their sense of self-efficacy from their IWM. Accordingly, positive and nega- tive representations contribute to high and low self-efficacy, re- spectively. The magnitude of child attachment has been meas- ured by the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP: Ainsworth, Ble- har, Waters, & Wall, 1978). The SSP is an experimental design in which researchers observe children’s behavior toward their parent after a short separation. The children are classified into one of three attachment styles: secure, anxious, or avoi- dant. Children with a secure attachment style do not show re- sistant behaviors toward their parent, whereas children with an anxious style desire proximity to their parent but simultaneous- ly resist their parent’s attempts at affection. Children with an avoidant style display avoidant behaviors and do not seek the proximity of their parent. A previous study (Van IJzendoorn, Goldberg, Kroonenberg, & Frenkl, 1992) indicated that 65%, 15%, and 20% of children are generally classified as having a secure, anxious, and avoidant attachment style, respectively. As for research on the attachment styles of children with au- tism spectrum disorders, a meta-analysis (Rutgers, Bakermans- Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, & Van Berckelaer-Onnes, 2004) showed that children with autism spectrum disorders exhibit a secure attachment style to the same degree as normally devel- oping children who had no diagnosis of autism spectrum disor- der according to the SSP method; specifically, 53% (range = 40% - 63%) of children with autism were classified having a secure attachment style. According to these results, children with an autism spectrum disorder may show the same development as those without an autism spectrum disorder, at least in terms of attachment formation (Dissanayake & Crossley, 1997). In contrast, although some studies might propose that the attach- ment of children with autism spectrum disorder would be  J. TAKAHASHI ET AL. different from the control children, their results could poten- tially be due to between-group differences in cognitive ability (e.g., intelligence quotient). Importantly, there were no differ- ences in the attachment styles between these groups of children when the level of cognitive ability was controlled (Rogers, Ozonoff, & Maslin-Cole, 1991). A recent study has shown that child attachment theory can be applied to adults throughout the life span (Ainsworth, 1989). In order to measure the magnitude of adult attachment, a previous study (DiTommaso, Brannen-McNulty, Ross, & Burgess, 2003) developed the Attachment Style Questionnaire. This question- naire is composed of three short paragraphs that correspond to the three attachment styles from the SSP method (i.e., secure, anxious, and avoidant). Previous studies have examined the re- lationships between the Attachment Style Questionnaire scores and various psychological adjustments (DiTommaso et al., 2003; Hori & Kobayashi, 2010; Kanemasa, 2005, 2007; Kanemasa & Daibo, 2003). This questionnaire has been frequently used to investigate adult attachment and processes good validity and re- liability. The purpose of the current study was to examine the rela- tionships between autism spectrum disorder, attachment style, and social skills in university students who had no formal di- agnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Recent studies of autism spectrum disorder have pointed out that there are behavioral and cognitive continuums among people with typical develop- ment, Asperger’s syndrome, and autism. Moreover, the behav- ioral and cognitive properties of individuals with autism extend to the general population, as shown by differences in Autism- spectrum Quotient (AQ: Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin, & Clubley, 2001) scores. Thus, by investigating the re- lationship between AQ scores and Attachment Style Question- naire scores, we can determine whether the adult attachment styles of people with higher AQ scores (High AQ group) are different from people with lower AQ scores (Low AQ group) in terms of individuals in the general population who had no di- agnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Moreover, we aimed to investigate the differences in social skills between the High AQ and Low AQ groups and how adult attachment style influenced this relationship. Method Participants The participants were 468 university students (183 men and 285 women). Their ages ranged from 18 to 23 years (M = 19.0; SD = 1.01). They all provided their informed consent before participating. The ethics committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Letters, Tohoku University, approved the study pro- tocol. Instruments We measured autism spectrum tendency (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001) by using the Japanese version of the AQ (Wakabayashi, Baron-Cohen, & Ashwin, 2012; Wakabayashi, Baron-Cohen, Uchiyama, Yoshida, Tojo, Kuroda, & Wheelwright, 2007; Wa- kabayashi, Tojo, Baron-Cohen, & Wheelwright, 2004; Waka- bayashi, Baron-Cohen, & Wheelwright, 2006). The AQ con- sists of 50 items referring to various situations. The participants rated each of these items on a 4-point scale. Example items included: “I prefer to do things with others rather than on my own,” “I prefer to do things the same way over and over again,” and “If I try to imagine something, I find it very easy to create a picture in my mind” (for additional details, see Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). The AQ is composed of five subscales: social skills, local details, attention switching, communication, and imagina- tion. The test-retest reliability and internal consistency of the AQ have been shown to be good (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). The differences in scores between people with and without an autism diagnosis were similar in the UK and Japan (Wakaba- yashi et al., 2007). Thus, the results obtained in the UK (Baron- Cohen et al., 2001) regarding reliability and validity generalizes to the Japanese version of the AQ (Wakabayashi et al., 2006). A high score on the AQ indicates a high degree of autism spec- trum traits. Attachment style was measured using the IWM scale (Ta- kuma & Toda, 1988). The IWM scale measures adult attach- ment style in the same way as the Attachment Style Question- naire (Hazan & Shaver, 1987) developed by Toda in Japanese. The IWM scale is printed in Japanese, and it consists of 18 items. The participants were asked to rate each of these items on a 5-point scale. Example items on the IWM scale included: “I am easier to get to know than most people,” “I have more self-doubts than most people,” and “I am more independent and self-sufficient than most people” (for additional details, see the English version Yukawa, Tokuda, & Sato, 2007). The test-re- test reliability and internal consistency of the IWM scale have been shown to be good. Social skills were measured by Kikuchi’s Social Skills Scale (KiSS-18) (Kikuchi, 2004). This questionnaire, printed in Japa- nese, measures people’s skills in receiving a positive reply from others. The KiSS-18 consists of 18 items on various situations involving social interaction. The participants rated these on a 5-point scale. For example, items on the KiSS-18 included the following: “Do you tend to halt a conversation while talking with someone,” “Can you explain well what you want someone to do,” and “Can you give practical help to others” (for additio- nal details, see the English version Katagami, Ohmura, & Nitta, 2010). The KiSS-18 is a single-factor model. The test-retest re- liability and internal consistency of the KiSS-18 have been shown to be good. Procedure All 468 participants completed the AQ, IWM, and KiSS-18 questionnaires in group settings. Results Psychometric Properties of the AQ, IWM, and KiSS-18 in This Study Table 1 shows correlations between scores on the AQ, IWM, and KiSS-18. The mean AQ score was 21.38 (SD = 6.20). The reliability coefficients for social skills, local details, attention switching, communication, and imagination were .69, .56, .37, .50, and .41, respectively. We examined the differences be- tween males and females in the total AQ scores. The t test re- vealed that men had higher AQ scores than women did [t(466) = 2.65, p < .01]. The mean IWM score was 63.36 (SD = 7.89). The reliability coefficients for the secure, anxious, and avoidant types were .86, .79, and .72, respectively. There was no significant differ- ence between men and women in the total IWM scores [t(466) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 515  J. TAKAHASHI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 516 Table 1. Correlations between scores on the AQ, IWM, and KiSS-18. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 AQ total 1 .73** .29** .64** .70** .61** .10 −.44** .34** .28** −.53** 2 AQ (social skill) 1 −.14** .37** .47** .39** −.02 −.63** .27** .36** −.57** 3 AQ (Local details) 1 .04 −.10 −.10 .11 .19** −.004 −.02 .20** 4 AQ (Attention switching) 1 .34** .24** .10 −.26** .26** .17** −.40** 5 AQ (Communication) 1 .34** .10 −.33** .35** .16** −.46** 6 AQ (Imagination) 1 .004 −.23** .14** .11 −.35** 7 IWM total 1 .35** .60** .63** .10 8 IWM (Secure) 1 −.27** −.24** .66** 9 IWM (Anxious) 1 .26** −.37** 10 IWM (Avoidant) 1 −.18** 11 KiSS-18 total 1 Note: **p < .01. = 1.23, p = .22]. The mean KiSS-18 score was 56.95 (SD = 10.98). The reli- ability coefficient for the KiSS-18 was .89. There was no sig- nificant difference between males and females in the total KiSS-18 scores [t(466) = 0.40, p = .69]. Correlation Analysis The AQ (5 subscales: social skill, local details, attention switching, communication, and imagination), the IWM (3 sub- scales: secure, anxious, and avoidant), and the KiSS-18 (a single- factor model) were subjected to a correlation analysis. We found significant correlations (r > .03, p < .01) between the total AQ scores and two IWM subscale scores (secure: r = −.44, p < .01; anxious: r = .34, p < .01), and between the total AQ scores and KiSS-18 scores (r = −.53, p < .01). We found sig- nificant correlations between the social skills subscale scores of the AQ and two IWM subscales scores (secure: r = −.63, p < .01; avoidant: r = .36, p < .01) and between social skills sub- scale scores and the KiSS-18 scores (r = −.57, p < .01). A sig- nificant correlation between attention switching subscale scores of the AQ and the KiSS-18 scores was found (r = −.40, p < .01). There were significant correlations between the communication subscale scores of the AQ and KiSS-18 scores (r = −.35, p < .01). Moreover, we found significant correlations between secure and anxious subscale scores of the IWM and KiSS-18 scores (r = .66, p < .01; r = −.37, p < .01, respectively). Differences in Adult Atta chment Style In order to examine the characteristics of adult attachment in people with higher AQ score, the participants were divided into groups with high and low AQ scores by adopting a cutoff point proposed by a previous study (Woodbury-Smith, Robinson, Wheelwright, Baron-Cohen, 2005). According to their criterion, people who had an AQ score of greater than or equal to 26 points were classified as having High AQ; those who had AQ scores less than 25 points were classified as Low AQ (High AQ group: n = 121; 58 men and 63 women, M AQ total score = 29.30, SD = 2.81; Low AQ group: n = 347; 125 men and 222 women, M AQ total score = 18.62, SD = 4.42]. We examined the differences in each IWM subscale (secure, anxious, and avoidant attachment styles) score between the High and Low AQ groups. Regarding the secure attachment style, the High AQ group had lower scores than the Low AQ group [t(466) = 7.74, p < .001]. For the anxious style, the High AQ group had higher scores than the Low AQ group [t(466) = 5.24, p < .001]. Finally, for the avoidant style, the High AQ group had higher scores than the Low AQ group [t(466) = 6.30, p < .001]. Differences in Social Skills First, we examined the differences in KiSS-18 scores be- tween the High AQ and Low AQ groups; results showed that the High AQ group had a higher mean score than did the Low AQ group [t(466) = 9.35, p < .001]. In order to examine the effects of individual differences, in AQ and IWM results on KiSS-18 scores, participants were divided into groups with high and low IWM secure subscale scores using the median score as a cutoff point. The 32 partici- pants who had a score of exactly 21 points (i.e., the median) were excluded [High IWM secure group: n = 233; 78 men and 155 women, M score = 25.48, SD = 2.91; Low IWM secure group: n = 203; 92 men and 111 women, M score = 16.63, SD = 3.33]. For the anxious subscale, participants were classified into groups with high and low scores based using the median score as a cutoff point. Eleven participants with a score of exactly 23 points (i.e., the median) were excluded [High IWM anxious subscale group: n = 222; 90 men and 132 women, M score = 27.17, SD = 2.71; Low IWM anxious subscale group: n = 210; 81 men and 129 women, M score = 18.83, SD = 2.97]. Regard- ing the avoidant subscale, the participants were classified into groups with high and low scores using the median score as a cutoff point. The 14 participants who had a score of exactly 19 points (i.e., the median) were excluded [High IWM avoidant group: n = 209; 84 men and 125 women, M score = 23.22, SD = 3.32; Low IWM avoidant group: n = 226; 91 men and 135 women, M score = 14.93, SD = 2.75]. Next, on the basis of  J. TAKAHASHI ET AL. these classifications, we created four groups for each of the three IWM subscales: (1) High or Low AQ groups and High or Low IWM secure groups; (2) High or Low AQ groups and High or Low IWM anxious groups; and (3) High or Low AQ groups and High or Low IWM avoidant groups. Regarding the AQ/IWM secure subscale [High AQ/High IWM: n = 31; High AQ/Low IWM: n = 87; Low AQ/High IWM: n = 202; Low AQ/Low IWM: n = 116], we conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with KiSS-18 score as the between-participants factor of AQ/IWM secure (4 groups; High AQ/High IWM, High AQ/Low IWM, Low AQ/High IWM, Low AQ/Low IWM). We found a significant main effect of the AQ/IWM secure [F(3, 432) = 86.194, p < .001] (Figure 1(a)). Post-hoc tests (Tukey’s HSD method) revealed that the KiSS-18 scores were the highest in Low AQ/High IWM and lowest in the High AQ/Low IWM group [Low AQ/High IWM vs. High AQ/High IWM: t(432) = 3.96, p < .05; Low AQ/High IWM vs. High AQ/Low IWM: t(432) = 15.10, p < .05; Low AQ/High IWM vs. Low AQ/Low IWM: t(432) = 10.41, p < .05; High AQ/Low IWM vs. High AQ/High IWM: t(432) = 5.61, p < .05; High AQ/Low IWM vs. Low AQ/Low IWM: t(432) = 5.11, p < .05]. However, there was no difference between the groups of High AQ/High IWM and Low AQ/Low IWM [t(432) = 2.22, p > .05]. Regarding the AQ/IWM anxious subscale [High AQ/High IWM: n = 79, High AQ/Low IWM: n = 35, Low AQ/High IWM: n = 143, Low AQ/Low IWM: n = 175], we conducted a one-way ANOVA with KiSS-18 score as the between-partici- pants factor of AQ/IWM anxious (4 groups; High AQ/High IWM, High AQ/Low IWM, Low AQ/High IWM, Low AQ/ Low IWM). The results showed a significant main effect of the AQ/IWM anxious [F(3, 428) = 36.01, p < .001] (Figure 1(b)). Post-hoc test revealed that the KiSS-18 scores for the Low AQ/Low IWM was the highest compared with other groups [Low AQ/Low IWM vs. High AQ/High IWM: t(428) = 10.03, p < .05; Low AQ/Low IWM vs. High AQ/Low IWM: t(428) = 4.94, p < .05; Low AQ/Low IWM vs. High AQ/Low IWM: t(428) = 4.13, p < .05]. In addition, the Low AQ/High IWM group had higher KiSS-18 scores than the High AQ/Low IWM group [t(428) = 2.38, p < .05]. However, there was no differ- ence between the High AQ/High IWM and High AQ/Low IWM groups [t(428) = 2.19, p > .05]. Regarding the AQ/IWM avoidant subscale [High AQ/High IWM: n = 74, High AQ/Low IWM: n = 40, Low AQ/High IWM: n = 135, Low AQ/Low IWM: n = 186], we conducted a one-way ANOVA with KiSS-18 as the between-participants factor of the AQ/IWM anxious subscale (4 groups; High AQ/ High IWM, High AQ/Low IWM, Low AQ/High IWM, Low AQ/Low IWM). The results showed a significant main effect of the AQ/IWM avoidant subscale [F(3, 431) = 30.00, p < .001] (Figure 1(c)). Post-hoc test revealed that the KiSS-18 score for the Low AQ/Low IWM group was higher than that of the High AQ/High IWM and High AQ/Low IWM [Low AQ/Low IWM vs. High AQ/High IWM: t(431) = 8.27, p < .05; Low AQ/Low IWM vs. High AQ/Low IWM: t(428) = 5.08, p < .05]. In addi- tion, the Low AQ/High IWM group had higher KiSS-18 scores than both the High AQ/High IWM and High AQ/Low IWM groups [Low AQ/High IWM vs. High AQ/High IWM: t(431) = 6.65, p < .05; Low AQ/High IWM vs. High AQ/Low IWM: t(428) = 3.94, p < .05]. Figure 1. Comparisons of the KiSS-18 score on the AQ/IWM. (a) Individual differences in the KiSS-18 scores for the AQ/IWM secure group [High AQ/High IWM: n = 31; High AQ/Low IWM: n = 87; Low AQ/High IWM: n = 202; Low AQ/Low IWM: n = 116]. (b) Individual differ- ences in the KiSS-18 scores for the AQ/IWM anxious group [High AQ/High IWM: n = 79; High AQ/Low IWM: n = 35; Low AQ/High IWM: n = 143; Low AQ/Low IWM: n = 175]. (c) Individual differ- ences in the KiSS-18 scores for the AQ/IWM secure groups [High AQ/High IWM: n = 74; High AQ/Low IWM: n = 40; Low AQ/High IWM: n = 135; Low AQ/Low IWM: n = 186]. The error bars denote the standard error of the mean. Discussion Our present study investigated the relationships between the tendency for autism spectrum disorder (indexed by the AQ), adult attachment styles (indexed by the IWM), and social skills (indexed by the KiSS-18) of university students with typical development by using a questionnaire method. First, we calculated correlations between the total AQ, IWM, and KiSS-18 scores. Specifically, there were significant corre- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 517  J. TAKAHASHI ET AL. lations between total AQ scores and scores of the IWM secure and anxious subscales. Also, there were small but significant correlations between AQ scores and IWM avoidant subscale scores. These results indicated that the higher the AQ score, the lower the IWM secure subscale score. Moreover, the higher the AQ score, the higher the IWM anxious and avoidant subscales score. In addition, the AQ scores were significantly correlated with the KiSS-18 scores, indicating that the higher the AQ score, the lower the KiSS-18 score. Furthermore, we studied the characteristics of adult attach- ment in people with higher AQ scores (High AQ group). The High AQ group had higher IWM secure subscale scores than did the Low AQ group, but lower anxious and avoidant sub- scale scores. These results indicated that people with High AQ scores might less of a tendency to exhibit secure attachment and a greater tendency to exhibit anxious and avoidant attachment styles. Moreover, we examined the effects of the interaction of the AQ and IWM on KiSS-18 scores by composing the following 4 groups for each of the three attachment subscale scores: (1) the High AQ/High IWM group, (2) the High AQ/Low IWM group, (3) the Low AQ/High IWM group, and (4) the Low AQ/Low IWM group. Regarding the secure subscale of the IWM, KiSS- 18 scores for each group were ordered as follows: Low AQ/ High IWM secure > High AQ/High IWM secure = Low AQ/ Low IWM secure > High AQ/Low IWM secure. For the anx- ious subscale, KiSS-18 scores for each group were ordered as follows: Low AQ/Low IWM anxious > Low AQ/High IWM anxious > High AQ/High IWM anxious = High AQ/Low IWM anxious. Finally, for the avoidant subscale of the IWM, KiSS- 18 scores for each group were Low AQ/High IWM avoidant = Low AQ/Low IWM avoidant > High AQ/High IWM avoidant = the High AQ/Low IWM avoidant. These results indicated that people with High AQ scores generally had low KiSS-18 scores. In this regard, when participants had a High IWM secure score, they tended to have a similarly KiSS-18 score compared with people with a Low AQ score or a Low IWM secure score. In contrast, for the anxious attachment style, people with a High AQ score tended to score the lowest on the KiSS-18 compared with other group, regardless of whether they had a High or a Low IWM anxious subscale score. The same tendencies were observed for the avoidant attachment style. Previous studies have examined the attachment style charac- teristics of children with autism using the SSP (Ainsworth et al., 1978). The results (Rutgers et al., 2004) showed that 53% (range = 40% - 63%) of children with autism were classified as having a secure attachment style. Recent studies have shown that child attachment theory can be extended to adults (Ains- worth, 1989) and assessed using questionnaires. In addition, in studying autism spectrum disorder, the behavioral and cognitive characteristics of individuals with autism can extend to indi- viduals with typical development who had no diagnosis by differing on the AQ score (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). In view of this background, the present study, using a questionnaire survey, showed how adult attachment styles interact with au- tism spectrum traits for those with no formal diagnosis of au- tism spectrum disorders. We found that people with higher AQ scores showed a reduced tendency for a secure attachment style and a greater tendency for anxious and avoidant attachment styles. These results are consistent with a previous study (Rut- gers, Van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Swinkels, Van Daalen, Dietz, Naber, Buitelaar, & Van Engeland, 2007), which compared Brief Attachment Screening Questionnaire scores among children with autism spectrum, typically developing children, and children with other clinical disorders. They show- ed that autistic children were far less likely to have a secure style than typically developing children. However, previous studies (Rutgers et al., 2004; Dissanayake & Crossley, 1997) have also indicated that children with autism spectrum disor- ders may show normal development in attachment formation, just as in typically developing children. Regarding this point, as in the previous study (Rutgers et al., 2007), we used the ques- tionnaire method and quantitatively analyzed attachment style, as opposed to the qualitative classification of the SSP (Rutgers et al., 2004). Nevertheless, many previous studies have used SSP. We may need to re-examine our results by using other ex- perimental methods such as interview method (Adult Attach- ment Interview: Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). The present study also examined the effects of autism spec- trum disorder and adult attachment style on social skills. First, the High AQ group showed lower social skills compared with the Low AQ group. This result is the same as was found in previous findings (American Psychiatric Association, DSM-IV- TR, 2000; Laushey & Heflin, 2000). Accordingly, we examined the characteristics of social skills by considering both adult attachment and AQ scores, dividing participants according to their scores on the AQ (High or Low) and their scores for each of the subscales of the IWM (High or Low), creating a total of 12 groups. For the secure subscale, the Low AQ and High IWM group had the highest KiSS-18 score. This result was consistent with the previous studies, indicating that the higher the ten- dency of autism spectrum disorder, the lower the social skills (Laushey & Heflin, 2000), while the higher the secure score, the higher the social skills (DiTommaso et al., 2003). For the High AQ groups, the KiSS-18 scores were higher when people had a higher secure tendency than when people had a lower secure tendency. Moreover, there was no significant difference between people with high AQ and high secure scores, and peo- ple with low AQ and high secure scores. These results indicated that even if people had a higher tendency of autism spectrum, they had a higher social skill ability when they had a higher tendency of secure style than when they had a lower tendency of secure style, showing a similar level of social skill ability compared to people with lower tendency for AQ and IWM secure when they had a higher tendency for a secure attachment style. For the anxious subscale of the IWM, the Low AQ and Low IWM group had the highest KiSS-18 score. These results were the same as those reported in a previous study (DiTom- maso et al., 2003; Laushey & Heflin, 2000). For the High AQ groups, there was no significant difference in social skills be- tween the High AQ and High IWM anxious group and the High AQ and Low IWM anxious group, indicating that the tendency for autism spectrum disorder mainly affects social skills, re- gardless of their anxious attachment style tendency. Similar re- sults were observed for the IWM avoidant subscale. Specifi- cally, there was no significant difference in social skills be- tween the High AQ and High IWM avoidant group and the High AQ and Low IWM avoidant group. Considering these results, we speculate that for people with high autism spectrum traits, anxious and avoidant scores did not affect social skills. This is in contrast to the secure style, which could modulate social skill ability. We found that the IWM secure subscale scores were strongly correlated with KiSS-18 scores (r = .663, p < .01), whereas he anxious and avoidant subscales were Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 518  J. TAKAHASHI ET AL. weakly correlated with KiSS-18 scores (anxious: r = −.370, p < .01; avoidant: r = −.178, p < .01). We assumed that this find- ing was due to the weaker correlations between the anxious and avoidant attachment styles and KiSS-18 scores. These attach- ment styles might not affect the social skill ability of people with a high tendency for AQ. One might argue that our present results may not be able to be generalized to those with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder because our sample was composed of university stu- dents who did not have a diagnosis. However, we conducted the present investigation because of the recent suggestion that au- tistic characteristics of people with a diagnosis may be ex- tended to people that experienced a typical development (Ba- ron-Cohen et al., 2001). In addition, the questionnaire method is useful for investigating the characteristics of adult attachment style (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). To provide additional support for our present results, future research may need to confirm the present results in people with a diagnosis by using another re- search method to measure adult attachment such as the inter- view method or the questionnaire method. Conclusion In conclusion, our present investigation examined the rela- tionships between autism spectrum traits, using a questionnaire method. People with higher autism traits had a higher tendency for a secure attachment style and a lower tendency for anxious and avoidant attachment styles. In addition, we found that in people with a high tendency for autism spectrum disorder, the secure style affected to the social skill ability, whereas the anx- ious and avoidant styles did not. Our present results provide additional knowledge about the relationships between autism spectrum tendency, adult attachment style, and social skills. Adult attachment style (particularly the secure attachment style) may serve as a mediator in the relationship between autism spectrum traits and social skills. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Dr. Masako Tsurumaki and Dr. Aki- ko Harano for their valuable support. This work was support- ed by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant- in-Aid for Scientific Research to J. T. (Grant No. 25-9251). REFERENCES Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44, 709-716. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709 Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The Autism-spectrumQuotient (AQ): Evidence from As- perger Syndrome/high-functioning Autism, males and females, sci- entists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 5-17. doi:10.1023/A:1005653411471 Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. London: Hogarth Press. Dissanayake, C., & Crossley, S. A. (1997). Autistic children’s respons- es to separation and reunion with their mothers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 27, 295-312. doi:10.1023/A:1025802515241 DiTommaso, E., Brannen-McNulty, C., Ross, L., & Burgess, M. (2003). Attachment styles, social skills and loneliness in young adults. Per- sonality and Individual Differences, 35, 303-312. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00190-3 Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Conceptualizing romantic love as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 Hori, M., & Kobayashi, T. (2010). Association among adult attachment, social skills, and psychological adjustment for university students. Journal of School M e ntal Health, 13, 41-48. Kanemasa, Y. (2005). Early adult attachment styles, emotional regula- tion and sensitivity, and interpersonal stress coping: An examination of conceptual consistency in infant and early adult attachment styles. The Japanese Journal of Personality, 14, 1-16. doi:10.2132/personality.14.1 Kanemasa, Y. (2007). The relationships between early adult attachment styles and adjustment in friendships. The Japanese Journal of Social Psychology, 22, 274-284. Kanemasa, Y., & Daibo, I. (2003). Early adult attachment styles and social adjustment. The Japanese Journal of Psyc h o l og y , 74, 466-473. doi:10.4992/jjpsy.74.466 Katagami, D., Ohmura, H., & Nitta, K. (2010). Investigation of social adaptive skills by cross-cultural simulation game and KiSS-18. FUZZ-IEEE, 981-986. Kikuchi, A. (2004). Notes on the researchers using KiSS-18. Bulletin of the Faculty of Social Welfare, Iwate Prefectural University, 6, 41-51. Laushey, K. M., & Heflin, J. (2000). Enhancing social skills of kinder- garten children with autism through the training of multiple peers as tutors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disord ers, 30, 183-193. doi:10.1023/A:1005558101038 Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, child- hood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Mono- graphs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 66-104. doi:10.2307/3333827 Mukaddes, N. M., Kaynak, F. N., Kinali, G., Besikci, H., & Issever, H. (2004). Psychoeducational treatment of children with autism and re- active attachment disorder. Autism, 8, 101-109. doi:10.1177/1362361304040642 Rogers, S. J., Ozonoff, S., & Maslin-Cole, C. (1991). A comparative study of attachment behavior in young children with autism or other psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 483-488. doi:10.1097/00004583-199105000-00021 Rutgers, A. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A. (2004). Autism and attachment: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1123-1134. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00305.x Rutgers, A. H., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Swinkels, S. H. N., Van Daalen, E., Dietz, C., Naber, F. B. A., Bui- telaar, J. K., & Van Engeland, H. (2007). Autism, Attachment and parenting: A comparison of children with autism spectrum disorder, mental retardation, language disorder, and non-clinical children. Jour- nal of Abnormal Psychology, 35, 859-870. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9139-y Takuma, T., & Toda, K. (1988). Adolescent interpersonal attitudes in perspectives of attachment theory: Attempt to create adulthood at- tachment scales. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 196, 1- 16. Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Goldberg, S., Kroonenberg, P. M., & Frenkl, O. J. (1992). The relative effects of maternal and child problems on the quality of attachment: A meta-analysis of attachment in clinical sam- ples. Child Development, 63, 840-858. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01665.x Wakabayashi, A., Baron-Cohen, S., & Ashwin, C. (2012). Do the traits of autism-spectrum overlap with those of schizophrenia or obses- sive-compulsive disorder in the general population? Research in Au- tism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 717-725. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.008 Wakabayashi, A., Baron-Cohen, S., Uchiyama, T., Yoshida, Y., Tojo, Y., Kuroda, M., & Wheelwright, S. (2007). The Autism-spectrum Quotient (AQ) children’s version in Japan: A cross-cultural compa- rison. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 491-500. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0181-3 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 519  J. TAKAHASHI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 520 Wakabayashi, A., Tojo, Y., Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ) Japanese version: Evi- dence from high-functioning clinical group and normal adults. The Japanese Journal of Ps yc ho lo g y, 75, 78-84. doi:10.4992/jjpsy.75.78 Wakabayashi, A., Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2006). Are au- tistic traits an independent personality dimension? A study of the au- tism-spectrum quotient (AQ) and the NEO-PI-R. Personality and In- dividual Differences, 41, 873-883. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.003 Woodbury-Smith, M. R., Robinson, J., Wheelwright, S., & Baron-Co- hen, S. (2005). Screening adults for Asperger’s syndrome using the AQ: A preliminary study of its diagnostic validity in clinical practice. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 331-335. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-3300-7 Yukawa, S., Tokuda, H., & Sato, J. (2007). Attachment style, self-con- cealment, and interpersonal distance among Japanese undergraduates. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 104, 1255-1261.

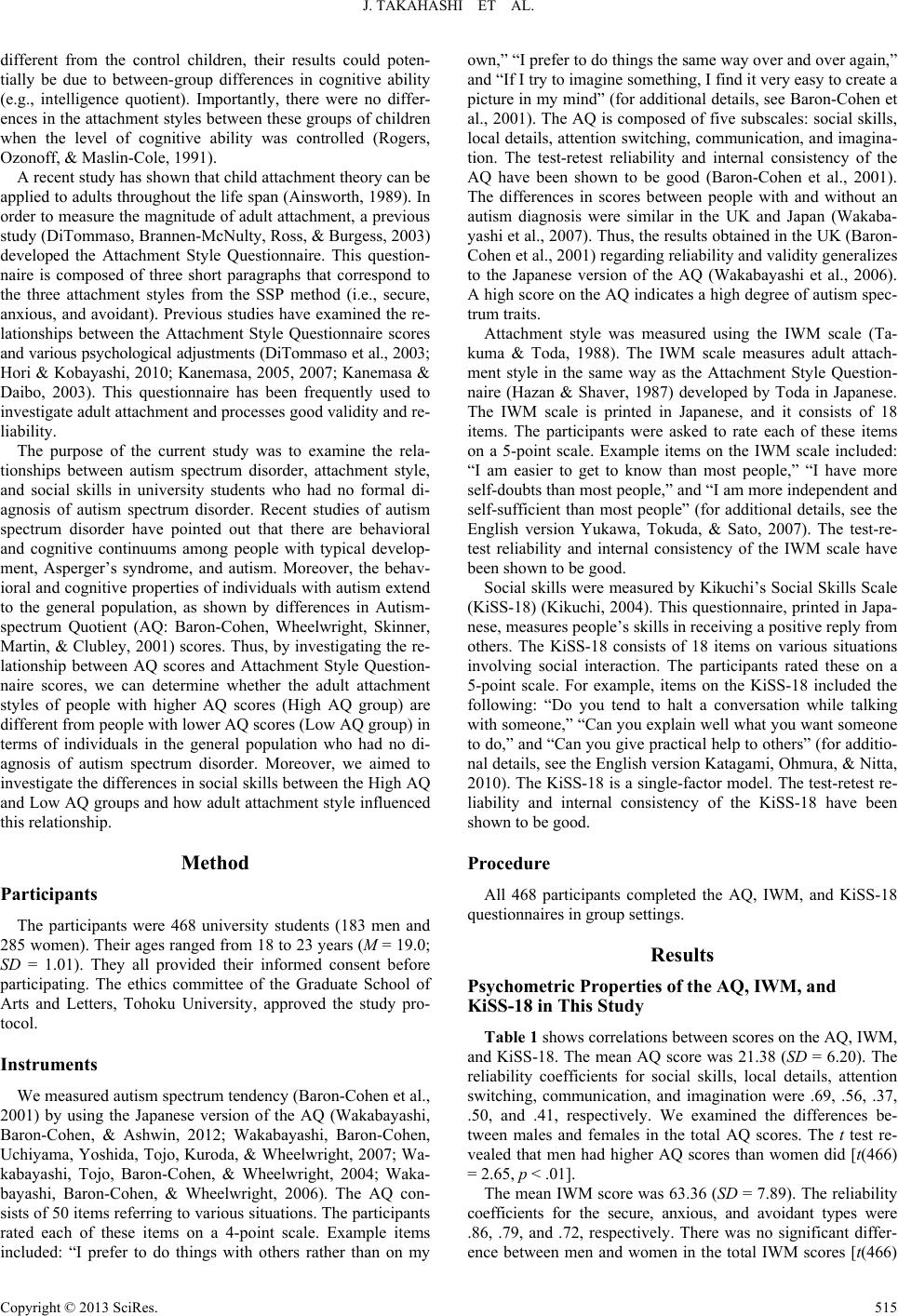

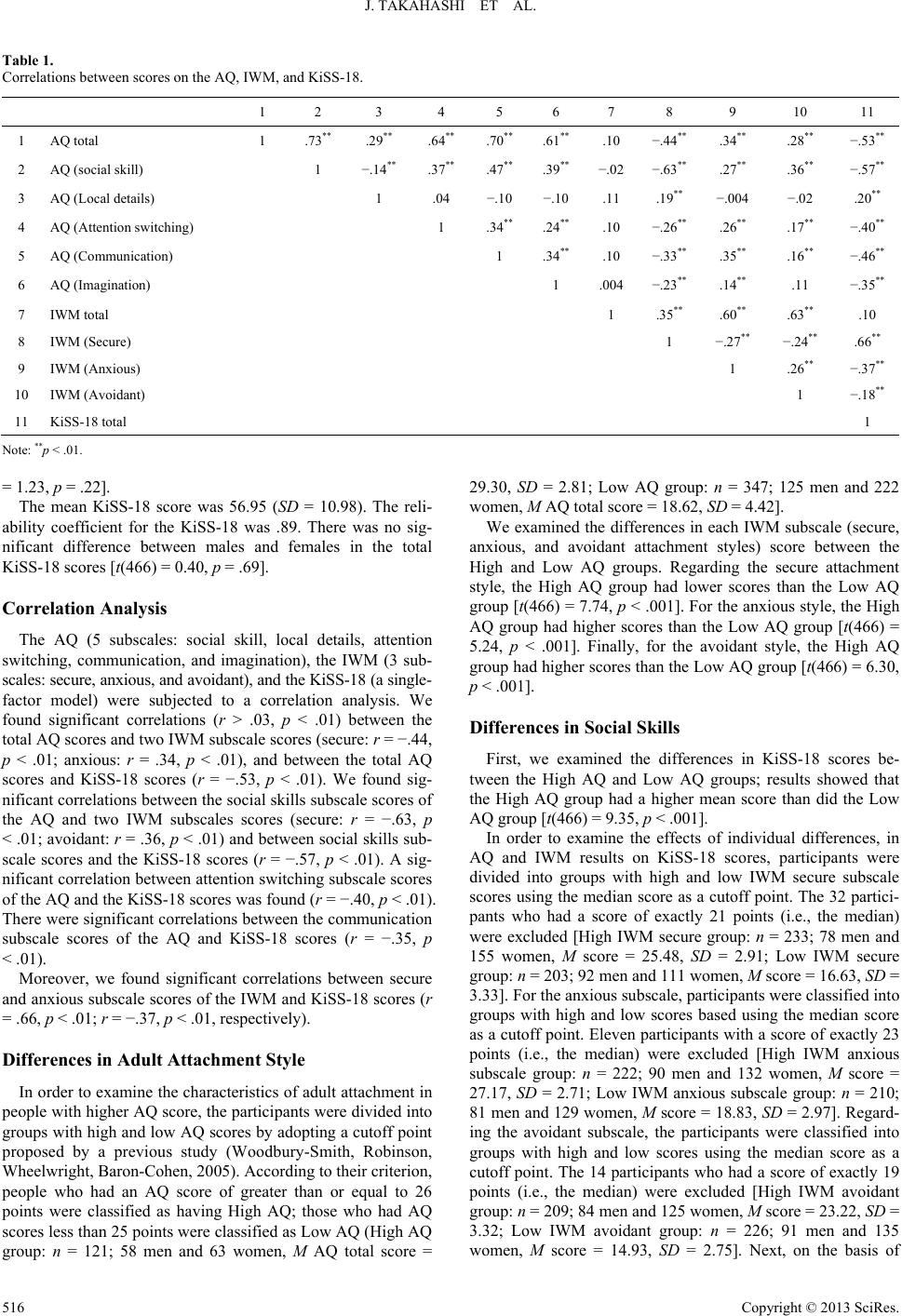

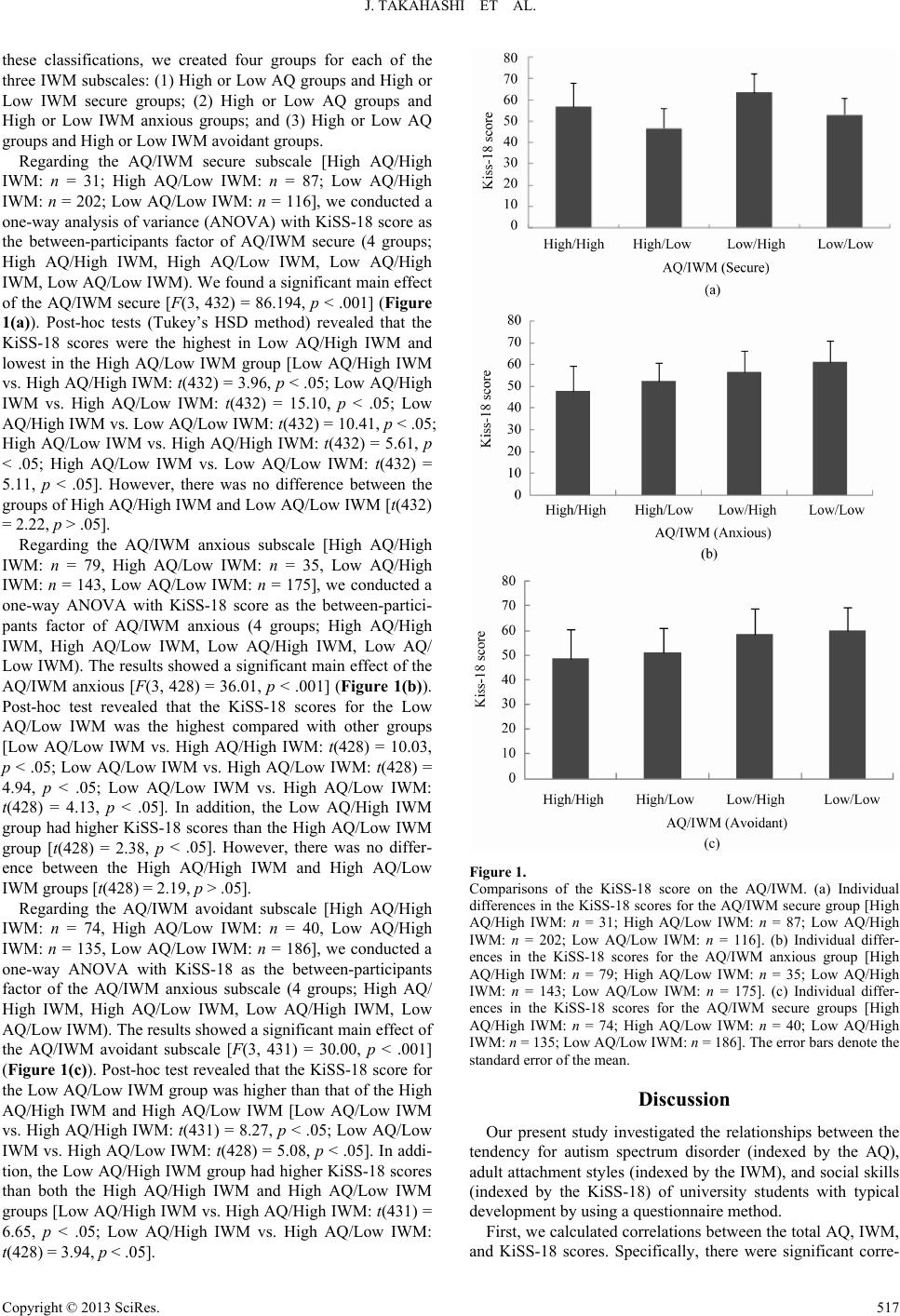

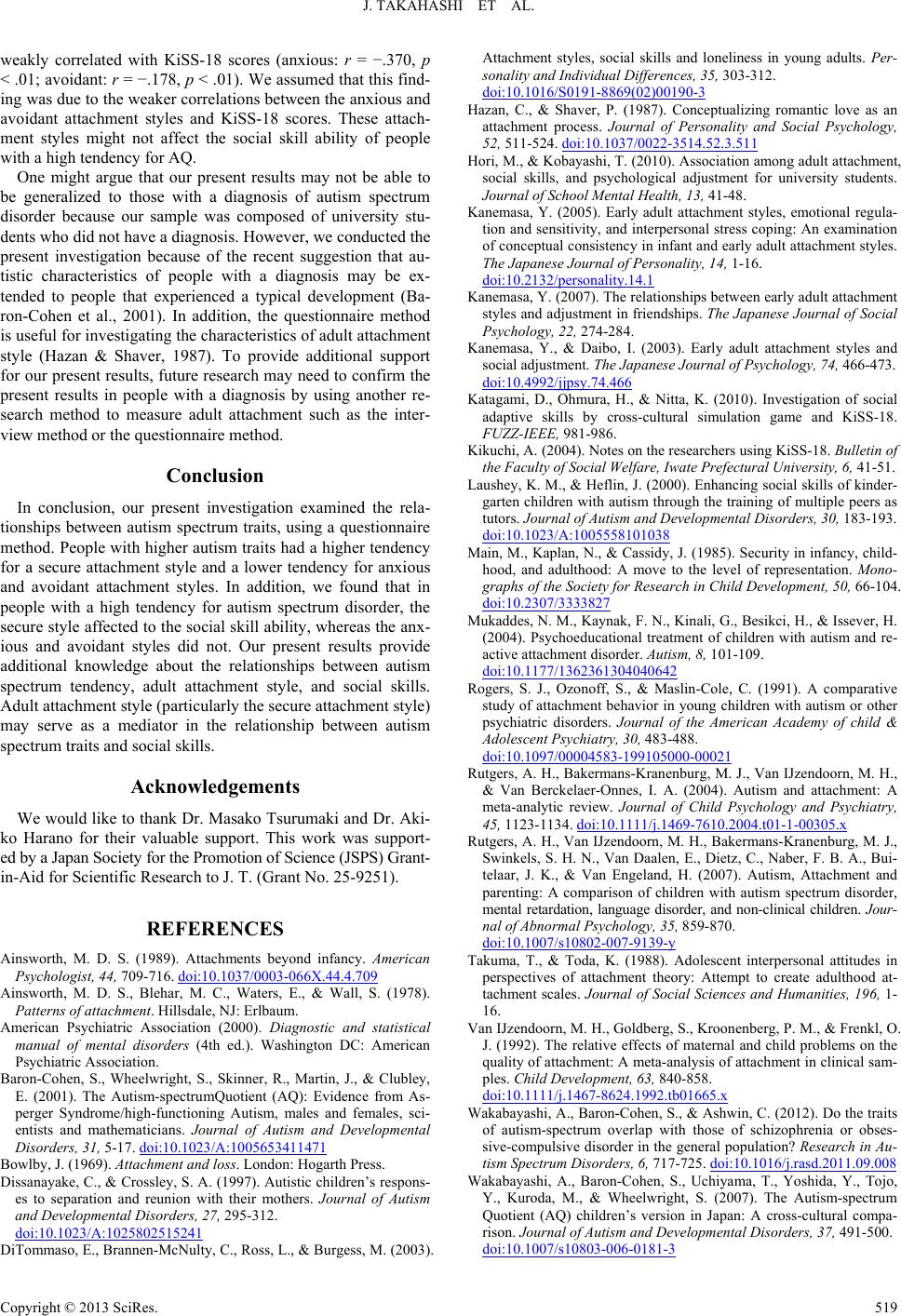

|