Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.8, 484-491 Published Online August 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.48070 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 484 Impact of Students’ Reading Preferences on Reading Achievement Yamina Bouchamma1, Vincent Poulin1, Marc Basque2, Catherine Ruel1 1Department of Foundations and Practices in Education, Laval University, Quebec, Canada 2Department of Kinesiology and Recreation, Moncton University, Moncton, Canada Email: yamina.bouchamma@fse.ulaval.ca Received April 19th, 2013; revised May 19th, 2013; accepted May 26th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Yamina Bouchamma et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Com- mons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, pro- vided the original work is properly cited. The reading preferences of 13-year-old boys and girls were examined to identify the factors determining reading achievement. Students from each Canadian province and one territory (N = 20,094) completed a questionnaire on, among others, the types of in-class reading activities. T-test results indicate that the boys spent more time reading textbooks, magazines, newspapers, Internet articles and electronic encyclo- pedias, while the girls read more novels, fiction, informative or non-fiction texts, and books from the school or local libraries. Logistical regression shows that reading achievement for both sexes was deter- mined by identical reading preferences: reading novels, informative texts, and books from the school li- brary, as well as level of interest in the class reading material and participation in the discussions on what was read in class. Keywords: Academic Achievement; Reading; Reading Preferences; Gender; Teaching Methods Introduction Learning to read is considered to be one of the most impor- tant skills in children as it enables them to achieve their goals, develop their knowledge, and reach their potential so as to take their rightful place in society (Statistique Canada, 2010). In 2009, Canadian 15-year-olds ranked above average in reading performance compared to other countries (Statistique Canada, 2010). On the national level, nine Canadian provinces obtained a score that was equal or superior to the OECD aver- age, with only Prince-Edward Island obtaining a lower than average rating. Students in Ontario and Alberta ranked the highest among all of the Canadian provinces, followed by those in British Columbia and Québec with average scores, and fi- nally those in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince-Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, Saskatchewan (Statistique Canada, 2010). Among these data, girls continued to far better than their male counterparts in reading achievement. This variance was in fact present in every Canadian province and in each country who participated in the PISA assessments (Statistique Canada, 2010). We thus felt it of importance to investigate the causes or factors influencing this difference between boys and girls in reading achievement. Learning to read is essential early on so as to enable children to perform well academically throughout their education but also to come into their own in society. It is for this reason that many scientific and education communities are looking closely at the gap between reading achievement levels, where girls ex- cel and boys do not (Bozack, 2011; Logan & Johnston, 2009, 2010; Watson et al., 2010; Lai, 2010; Below et al., 2010). Literature Review Generally speaking, girls are better readers and consequently are more likely to score higher on reading tests compared to their male peers (Bozack, 2011; Logan & Johnston, 2009, 2010; Lai, 2010; Watson et al., 2010; Below et al., 2010; Statistique Canada, 2010). This difference may be explained, among others, by gender developmental differences, both physiologically and psychologically (Below et al., 2010; Logan & Johnston, 2010). Environmental and cultural factors such as family support and socioeconomic status also appear to influence gender differ- ences in regards to reading achievement (Below et al., 2010). Furthermore, girls use the various reading strategies differ- ently and more effectively than do boys (Logan & Johnston, 2009, 2010). Not only are their cognitive abilities different (Lo- gan & Johnston, 2009, 2010), but girls are also more motivated and have a more positive attitude toward reading, compared to the opposite sex (Logan & Johnston, 2009, 2010; Below et al., 2010; Coddington & Guthrie, 2009). The reading interests of girls also differ from those of boys. In fact, it appears that certain types of reading material corre- spond better to interests specific to each sex (Moeller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Below et al., 2010). Allowing children to read according to their likes and interests motivates them to learn to read, have a more positive attitude (Logan & Medford, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010), and consequently, be more like- ly to perform better in reading (Bozack, 2011). Research Objectives We thus examined these gender differences pertaining to reading interests and determined their respective reading pref-  Y. BOUCHAMMA ET AL. erences, and in view of the results and the various teaching practices, we investigated whether the respect of these gender preferences influenced reading achievement. Reading preferences are presented according to gender but also depending on the importance of personal book choice, type of reading material involved, ICT use, and use of library re- sources. A discussion of the results follows, presenting the si- milarities, differences, and possible advantages between the ac- tual preferences of boys and girls and teaching practices. Reading Preferences Personal book choice. Several studies affirm that book choice should come from the student rather than be imposed by the teacher (Bozack, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Jenkins, 2009; Nichols & Cormack, 2009). Choosing books according to personal interests raises students’ level of motivation, encour- ages them to adopt a positive attitude, and perform better in this regard (Bozack, 2011; Gibson, 2010; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Jenkins, 2009; Nichols & Cormack, 2009; Merisuo-Storm, 2006). Boys experience this need for freedom to choose which books to read more than girls do and feel more motivated to read than in an imposed reading activity (Bozack, 2011; Jenkins, 2009; Nichols & Cormack, 2009). Boys also appreciate a vari- ety of books, articles, or texts on one same subject so as to bet- ter grasp what this reading may have to offer (Jenkins, 2009). The same holds true for girls who also think being allowed to choose their reading material is important; however, contrary to boys, this is less likely to negatively affect their level of achie- vement in reading (Bozack, 2011). Reading Genre Informative texts. Boys generally prefer informative texts such as newspaper articles, magazines, and texts pertaining to sports, video games, or cars, to name a few (Moeller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Watson et al., 2010; Farris et al., 2009; Williams, 2008; Chapman et al., 2007). They also enjoy read- ing comic strips, joke books, and more simple reading such as statistics on sports cards and the information on cereal boxes (Davila & Patrick, 2010). Boys see the point of reading when it is fact-based and en- ables them to learn something concrete by the end of the activ- ity (Farris et al., 2009). The informative text thus corresponds far better to their preferences in terms of learning to read. In- terestingly, this type of reading material is not often used in educational practices and is even frowned upon in today’s edu- cation curriculum (Moeller, 2011; Farris et al., 2009). Teachers prefer to use predominantly narrative or fictional reading mate- rial that generally corresponds much more to the values pro- moted in the curriculum (Below et al., 2010). Unfortunately, it appears that this literary genre rarely succeeds in satisfying the reading interests of boys (Moeller, 2011; Watson et al., 2010; Farris et al., 2009; Below et al., 2010). Girls regularly read catalogues, song lyrics, poetry, and cook-books, and also books in a series or ones involving the same characters (Davila & Patrick, 2010). Some girls also have reading preferences that are closer to the informative style. Moreover, magazines for adolescent girls dealing with various topics and interests of a more feminine nature are also part of their preferred reading. Generally, horoscopes and comic strips are what most girls find interesting above the other sections (Wilson & Casey, 2007). Predominantly fictional texts. Despite this, certain texts in the fiction genre may interest boys (Davila & Patrick, 2010; Koss & Teale, 2009). For this to occur, these texts must con- tain themes that gravitate around action or science-fiction (Mo- eller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010) or fall into the category of crime novel or thriller (Burgess & Jones, 2010; Davila & Pat- rick, 2010; Wilson & Casey, 2007). To fully interest boys, the focus of these texts should involve their characters in a timeline, in action, and in various adventures (Moeller, 2011). Not only are they more interested in the story but it is also easier for them to follow and to understand than when the focus is on the relationships and emotions between the characters, for example (Moeller, 2011). Girls, on the other hand, tend to prefer fiction (Moeller, 2011; Koss & Teale, 2009) in the form of thrillers, romance (Davila & Patrick, 2010; Wilson & Casey, 2007), or mystery novels (Burgess & Jones, 2010). In contrast to their male counter- parts who prefer to read concrete facts in informative texts, girls enjoy using their imagination when reading (Moeller, 2011) and view this exercise of developing creativity, while reading predominantly fictional texts, as both fun and useful. Moreover, both boys and girls enjoy horror stories, comedies, and books related to movies or a television show, and both show interest in reading the novel that inspired a movie they recently watched at a movie theatre or at home or a popular television show (Davila & Patrick, 2010). Information and Communications Techno logi es (ICTs) Several factors are not necessarily directly related to boys’ and girls’ reading preferences yet they provide insight on the use of educational reading material and the respective interests of each sex. For boys, the fact of using various information and communications technologies to help them learn to read is a highly significant factor in sustaining a positive level of interest and motivation (Jenkins, 2009; Sokal & Katz, 2008; Farris et al., 2009). Reading the teacher’s scanned texts directly on the com- puter screen enables boys to go on the Internet to find texts or articles corresponding to their interests and to exchange or dis- cuss them online through various forums with peers or the tea- cher (Jenkins, 2009; Sokal & Katz, 2008; Farris et al., 2009). As for girls, using technology has also been shown to stimulate their interest and motivation with regard to reading, although this support is less considerable than what is observed in boys (Sokal & Katz, 2008). Access to a Libr ary Regardless of gender, it is crucial that boys and girls have easy access to both the school and the public library, as this en- vironment provides an interesting support for students as they learn to read and contributes to making reading an integral part of regular student activities (Sanacore & Palumbo, 2010). On the same subject, Small et al. (2009) found that school libraries that provide appropriate access to computers and to qualified support staff have a positive effect on student achievement. In light of the literature, there apparently are no studies on the preferences of boys and girls and the use of the library as a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 485  Y. BOUCHAMMA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 486 viable resource, and gender is also not a variable or factor in the various studies pertaining to the use of libraries in regards to student achievement. Methodology Participants and Materi als Our study used data collected from the Pan-Canadian As- sessment Program (PCAP-13 Reading Assessment 2007) de- veloped by the Council of Ministers of Education of Canada (CMEC). This program collected information on 30,022 13- year-old Canadian students representing each Canadian prov- ince and one territory (Yukon) on three school subjects (reading, mathematics, and science). The sample used for this study rep- resented all of the participants who completed the reading seg- ment of the assessment (N = 20,094; 49.1% male). Most of these students were Native-born Canadian (93.4%) and were in the 8th grade (70.8%) when the data was collected. Seventy- five percent of the students in this sample identified English as their home-spoken and first language. Among the students who were aware of their mother’s education (N = 14,861; students who answered “I do not know” were excluded from this statis- tic), 69.4% revealed that their mother had at least obtained a high school diploma. Measures Reading preferences. Literary preferences were measured using questions one and three of the fifth section of the student questionnaire. The first question: How often do the following activities take place in your English Language Arts class? lists nine items on a 3-point frequency scale labelled rarely or never, sometimes, and often, while the second question: How do the following statements apply to the reading that you do in your English Language Arts class? houses six items on a 4-point frequency scale (1 = not at all, 4 = a lot). Academic achievement. This factor was determined by mea- suring the students’ reading achievement level. This achieve- ment level was measured by a reading task administrated to all of the students assigned to the reading booklet test segment. This segment focused on three reading sub-domains: compre- hension, interpretation, and response to text. Students were as- sessed on each of the three scales with a raw score awarded by the scoring administration team, table leaders, and scorers (tea- chers). These scores were then converted into a standard score ranging from 0 to 1000. An average score was subsequently calculated to appropriately assign each student to one of the three reading performance levels established by the reading pa- nel of educators across Canada. Students with a score of 379 or lower were assigned to level 1, designating a performance level below that expected of same-age students; students who obtain- ed a score between 380 and 575 were assigned to level 2 as ha- ving an acceptable level of performance; and students with a score of 576 or higher were assigned to level 3, designating an overall higher achievement reading level than that expected from same-age students. For the purpose of this study, students from levels 2 and 3 were combined to form the “success” group, while level 1 was used to designate the “failure” group. Results Table 1 presents the results of an independent sample t-test used to compare the reading preferences in 13-year-old male and female students. The t-test results show significant gender Table 1. Reading preferences by gender. Boys Girls Section 5, question 1: How often do the following activities take place in your French/or English class? M SD M SD t DL a) Reading the course textbook 1.83 0.71 1.81 0.72 2.088* 19,432.446 b) Reading newspapers or magazines 1.53 0.64 1.50 0.63 3.271** 19,311.655 c) Reading novels or fiction 2.35 0.65 2.48 0.60 −14.302*** 19,130.005 d) Reading informative or non-fiction texts 2.10 0.63 2.17 0.63 −8.541*** 19,354.869 e) Reading documents found on the Internet 1.68 0.65 1.64 0.65 4.446*** 19,402.334 f) Using on-line encyclopedias or other electronic documents accessed by signing up 1.41 0.59 1.36 0.57 5.967*** 19,260.496 g) Viewing videos, DVDs, or going to the movies 1.61 0.64 1.56 0.63 5.196*** 19,409 h) Reading books or other texts from the school library 1.93 0.68 2.03 0.70 −10.052*** 19,400 i) Reading books or other texts from the local library 1.39 0.60 1.41 0.69 −2.068* 19,404.313 Boys Girls Section 5, question 3: How do the following statements apply to the reading that you do in your Eng li sh class? M SD M SD t DL a) What we read in class is more for girls than it is for boys 1.48 0.78 1.31 0.62 16.977*** 18,053.788 b) What we read in class is more for boys than it is for girls 1.38 0.67 1.28 0.58 11.513*** 18,651.380 c) What we read in class interests me 2.09 0.84 2.28 0.80 −16.252*** 19,178.647 d) What we read in the other classes is harder than what we read in French class 1.68 0.85 1.70 0.83 −1.931 19,186.206 e) I participate in the discussions in my English class 2.63 0.92 2.67 0.91 −2.887** 19,294 f) I am behind in my reading assignments 1.71 0.90 1.51 0.79 16.488*** 18,761.693  Y. BOUCHAMMA ET AL. differences in all of the activities. Compared to their male peers, the female students reported lower self-exposure to reading ac- tivities such as reading a textbook (t (19,432.446) = 2.088, p < 0.05), magazines or newspapers (t (19,311.655) = 3.271, p < 0.01), and material found on the Internet (t (19,402.334) = 4.446, p < 0.001), using on-line encyclopaedias or other elec- tronic subscriptions (t (19,260.496) = 5.967, p < 0.001), and watching videos or DVDs or going to the movies (t (19,409) = 5.196, p < 0.001). Again, compared to the male students, the female students revealed being much more interested in reading in school (t (19,178.647) = −16.488, p < 0.001) and participated more in English Language Arts class discussions (t (19,294) = −2.887, p < 0.01). In contrast, the male students revealed lower self-exposure to such reading activities as reading novels or short stories (fiction) (t (19,130.005) = −14.302, p < 0.001), informative or non-fic- tion texts (t (19,354.869) = −8.541, p < 0.001), books or other reading material from the school library (t (19,400) = −10.052, p < 0.001), or public library (t (19,404.313) = −2.068, p < 0.05). Furthermore, despite feeling that what they read in class was much more appropriate for girls than for them (t (18,053.788) = 16.977, p < 0.001), some boys stated the opposite (t (18,651.380) = 11.513, p < 0.001). They also reported a higher score over the girls, considering that the texts they read in other classes were harder than those in the English Language Arts class (t (18,761.693) = 16.488, p < 0.001). Tables 2 and 3 present the determinant factors of reading achievement by gender. Variables were simultaneously inserted into the logistic regression model to identify the best indicators of boys’ and girls’ academic achievement. Although each sex was analyzed individually, the results were the same. Of all of the predictors, five were present as significant determinant factors of academic achievement for both groups. Read novels or short stories (fiction) (Boys: β = 0.43; p < .001; C. I. = 1.40 - 1.67; OR = 1.529; Girls: β = 0.32; p < .001; C. I. = 1.24 - 1.54; OR = 1.381), read information or non-fiction material (Boys: β = 0.25; p < .001; C. I. = 1.16 - 1.42; OR = 1.284; Girls: β = 0.40; p < .001; C. I. = 1.34 - 1.67; OR = 1.493), and read books or other material from the school library (Boys: β = 0.15; p < .001; C. I. = 1.06 - 1.28; OR = 1.167; Girls: β = 0.16; p < .01; C. I. = 1.07 - 1.30; OR = 1.177) had a favorable effect on performance for both sexes. The results of these analyses revealed that achievement was positively predicted by the interest both groups showed in the reading activities done in school (boys: β = 0.24; p < .001; C. I. = 1.18 - 1.36; OR = 1.264; girls: β = 0.23; p < .001; C. I. = 1.16 - 1.37; OR = 1.261) and by the level of participation in class discussions in English class (Boys: β = 0.33; p < .001; C. I. = 1.31 - 1.49; OR = 1.397; Girls: β = 0.18; p < .001; C. I. = 1.11 - 1.29; OR = 1.193). Discussion Reading Interests by Gender Our results indicate that the girls showed less interest in reading textbooks, magazines, newspapers, or articles found on the Internet, while the boys were more inclined to read elec- tronic encyclopedias and to watch movies. These findings con- cur with those of several recent studies on the subject (Moeller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Watson et al., 2010; Farris et al., 2009; Williams, 2008; Chapman et al., 2007). We also found that the girls were more likely to read novels or fictional stories and material from either a public or a school library. That girls outnumbered boys in reading novels and fiction is in agreement with the findings of Moeller (2011) and Koss and Teale (2009). Table 2. Determinant factors of boys’ reading achievement. Predictive variables B (SE) Wald OR 95% C. I. Constant 1.50 (0.15) 95.172*** 4.495 3.32 - 6.08 Read a textbook −0.01 (0.04) 0.013 0.995 0.92 - 1.08 Read magazines or newspapers −0.26 (0.05) 31.436*** 0.775 0.71 - 0.85 Read novels or short stories (fiction) 0.43 (0.05) 83.730*** 1.529 1.40 - 1.67 Read informational or non-fiction texts 0.25 (0.05) 24.561*** 1.284 1.16 - 1.42 Read material found on the Internet 0.04 (0.05) 0.762 1.045 0.95 - 1.15 Use on-line encyclopedias or other electronic subscriptions −0.35 (0.05) 46.053*** 0.702 0.63 - 0.78 Watch videos or DVDs or go to the movies −0.28 (0.04) 39.674*** 0.757 0.69 - 0.83 Read books or other material from the school library 0.15 (0.05) 10.724*** 1.167 1.06 - 1.28 Read books or other material from the public library −0.29 (0.05) 34.919*** 0.746 0.68 - 0.82 Constant 1.94 (0.12) 248.595*** 6.962 5.47 - 8.86 The reading we do in school is more for girls than it is for boys −0.15 (0.04) 14.506*** 0.861 0.80 - 0.93 The reading we do in school is more for boys than it is for girls −0.44 (0.05) 97.851*** 0.643 0.59 - 0.70 The reading we do in school interests me 0.24 (0.04) 40.441*** 1.264 1.18 - 1.36 The reading we do in other classes is harder than in English Language Arts −0.16 (0.03) 23.923*** 0.850 0.80 - 0.91 I participate in class discussions in English Language Arts 0.33 (0.03) 104.342*** 1.397 1.31 - 1.49 I am behind in homework that involves reading −0.30 (0.03) 103.073*** 0.739 0.70 - 0.78 Note: N = 9695. ***p < 0.001. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 487  Y. BOUCHAMMA ET AL. Table 3. Determinant factors of girls’ reading achievement. Predictive variables B (SE) Wald OR 95% C. I. Constant 2.20 (0.19) 130.012*** 9.049 6.20 - 13.21 Read a textbook −0.13 (0.05) 8.431** 0.876 0.80 - 0.96 Read magazines or newspapers −0.20 (0.05) 15.433*** 0.815 0.74 - 0.90 Read novels or short stories (fiction) 0.32 (0.06) 34.057*** 1.381 1.24 - 1.54 Read informational or non-fiction texts 0.40 (0.06) 50.910*** 1.493 1.34 - 1.67 Read material found on the Internet −0.21 (0.06) 14.614*** 0.808 0.72 - 0.90 Use on-line encyclopedias or other electronic subscriptions −0.33 (0.06) 31.746*** 0.721 0.64 - 0.81 Watch videos or DVDs or go to the movies −0.21 (0.05) 17.466*** 0.808 0.73 - 0.89 Read books or other material from the school library 0.16 (0.05) 10.047** 1.177 1.07 - 1.30 Read books or other material from the public library −0.27 (0.05) 24.937*** 0.766 0.69 - 0.85 Constant 2.579 (0.16) 271.634*** 13.181 9.71 - 17.90 The reading we do in school is more for girls than it is for boys −0.30 (0.05) 32.494*** 0.738 0.67 - 0.82 The reading we do in school is more for boys than it is for girls −0.20 (0.06) 12.881*** 0.816 0.73 - 0.91 The reading we do in school interests me 0.23 (0.04) 28.884*** 1.261 1.16 - 1.37 The reading we do in other classes is harder than in English Language Arts −0.12 (0.04) 10.119*** 0.884 0.82 - 0.96 I participate in class discussions in English Language Arts 0.18 (0.04) 22.125*** 1.193 1.11 - 1.29 I am behind in homework that involves reading −0.36 (0.04) 101.361*** 0.695 0.65 - 0.75 Note: N = 10,048. ***p < 0.001. The boys stated that they enjoyed reading magazines, news- papers, articles found on the Internet, and encyclopedias, and did not enjoy reading informative or non-fiction material. This represents a contradiction in the boys’ answers with regard to their reading preferences in the informative text category. When asked directly whether they liked this type of reading (in- formative), the answer was generally no, and yet they claimed enjoying magazines, newspapers, and encyclopedias, all of which are informative in nature. Future research should exam- ine this contradiction in the boys’ responses to the question- naire. The Impact on Reading Achievement Our results show that the achievement indicators related to reading preferences were the same for both sexes. The most significant indicators were reading novels or fictional texts, informative reading or non-fiction, and reading books or other texts from the school library. In-class reading and participation in discussions pertaining to school-related reading were also shown to enhance reading achievement. These results are somewhat surprising in that research docu- menting this subject mainly emphasizes the use of pedagogical material corresponding to the interests/needs of students to foster achievement in reading (Moeller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Koss & Teale, 2009; Farris et al., 2009). With identical determinants for both sexes, differentiation by gender thus ap- pears to have no significant impact on reading achievement. It would therefore be of interest to examine variables other than gender, such as socioeconomic origin or language spoken in the home, to better identify gender differences in reading abilities. Teaching Practices and Reading Achievement Having identified the various reading preferences of boys and girls and their association with reading achievement, we took a closer look at current educational practices in this regard. How we teach reading is particularly important because it is directly associated with student outcomes (Hairrell et al., 2011; Clanet, 2010; Palumbo & Sanacore, 2009). Our analysis hope- fully sheds light on the similarities and differences between existing practices and the actual reading interests of boys and girls which may help to improve teaching methods in this re- gard. In-Class Reading Material The choice of texts read in class is one of several teaching methods associated with reading achievement. Our analysis of the Pan-Canadian Assessment Program (PCAP) data involving 4446 teachers shows that at least one out of three teachers used narrative texts (M = 2.78), followed by informative texts (M = 2.46), poetry (M = 2.30), persuasive texts (M = 2.24), dramatic texts (M = 2.09), and finally, procedural texts (M = 1.78). Our review of the literature shows that reading outcomes differ greatly between the two sexes (Bozack, 2011; Logan & Johnston, 2009, 2010; Watson et al., 2010; Lai, 2010; Below et al., 2010), as do their reading preferences (Moeller, 2011; Da- vila & Patrick, 2010; Below et al., 2010). The choices teachers make with regard to what is read in class thus have an enor- mous impact on the success of their students; teachers must therefore address the reading needs and interests of both sexes. We found that narrative reading material (first choice among Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 488  Y. BOUCHAMMA ET AL. teachers) rarely appeal to boys (Moeller, 2011; Watson et al., 2010; Below et al., 2010), although they have been shown to somewhat enjoy certain fictional texts (Davila & Patrick, 2010; Koss & Teale, 2009). Teachers who wish to continue using narrative reading material may consider providing books that contain more adventures or science-fiction content, or that fall into the category of thrillers or crime novels (Moeller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Burgess & Jones, 2010). To find the informative text in second place is interesting, as many boys particularly enjoy this type of reading material (Mo- eller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Watson et al., 2010; Farris et al., 2009). To help boys improve their reading skills, it is thus critical that this category, including encyclopedias, news- papers, and magazines, be both preserved and encouraged in class. Teachers too easily dismiss this genre as not correspond- ing to the values promoted in the school curriculum (Below et al., 2010). And yet, it is precisely this type of reading which boys find both concrete and appealing (Farris et al., 2009). Finally, the fact that poetic texts were ranked as the third most preferred reading material among boys does not signifi- cantly influence their outcomes in reading. In fact, this genre does not correspond to their reading preferences (Davila & Patrick, 2010). A judicious use of poetry is thus recommended and should be combined with other types of text so as to ensure variety, as well as to help boys maintain a positive attitude to- ward their reading abilities and remain motivated in this regard. For the girls, the popularity of the narrative text is excellent news, as this is the literary genre most preferred by the majority of girls, according to several authors (Moeller, 2011; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Burgess & Jones, 2010; Koss & Teale, 2009). By proposing narrative texts such as thrillers, romance, or mystery novels, teachers will provide girls with what they enjoy reading the most (Davila & Patrick, 2010; Burgess & Jones, 2010; Wil- son & Casey, 2007). Some girls enjoy informative texts by reading magazines, newspaper articles and song lyrics on a re- gular basis (Davila & Patrick, 2010). Here again, the fact that this type of reading material ranked second among those most used in the classroom also favors the reading outcomes of girls. The same goes for poetry, as girls enjoy this genre more than boys do (Davila & Patrick, 2010). Differentiated Teaching Practices The PCAP data analyzed also favored boys in the type of reading material provided in class (average of 2.31), followed by texts specifically for boys (2.26), texts specifically for girls (2.20), and texts for the entire class but adapted more for girls (2.07). Lastly, teachers differentiated their practices to meet the needs and interests of both sexes (1.86). These data highlight the importance of choosing the appro- priate strategies when teaching children how to read. Our lit- erature review shows that girls perform better than do their male counterparts when reading is proposed (Bozack, 2011) and that respecting the reading preferences and interests of boys has a more positive impact on their motivation and attitude (Bo- zack, 2011; Jenkins, 2009; Nichols & Cormack, 2009). The fact that Canadian teachers appear to respect boys’ reading prefer- ences shows a certain acknowledgement of the problem and the desire to encourage reading achievement for both sexes. How- ever, in doing so, achievement in girls is not maximized. Stud- ies on the subject have shown that respecting the reading pref- erences of girls also has a positive impact on their outcomes in reading (Bozack, 2011). It thus appears that the ideal teach- ing method is the one that allows students to choose the reading material, as both sexes ultimately choose texts that better suit their individual interests. Interestingly, as indicated in Table 1, differentiating teaching practices for reading according to each gender’s preferences is far from unanimous among Canadian teachers, despite the fact that this solution appears to be among those that satisfy the needs and interests of each sex the most in terms of reading achievement. Several studies tend to show that this individual- ized practice is critical when achievement by gender is con- cerned (Lai, 2010; Calvin et al., 2010; Logan & Johnston, 2010; Haworth et al., 2010). Library Resources as a Teaching Strategy According to the literature, to improve their reading skills, students must have access to a library (Sanacore & Palumbo, 2009; Small et al., 2009). But are library resources truly an in- tegral part of teaching practices? In a study on teaching practices, Al-Barakat and Bataineh (2011) found that the fact of having a library in the classroom has a positive influence on the level of interest and reading achievement, as does the school library or public library. A solid professional collaboration between teachers and librarians appears to be another significant factor, as it enables students to fully exercise their knowledge in terms of reading skills (Roux, 2008). This relationship, however, does not always exist be- tween teachers and school professionals. Some schools may lack personnel in charge of library resources, or it may be that teachers are simply not inclined to collaborate with the other professionals in the school (Roux, 2008), even if, thanks to these school members, students are able to greatly benefit from the different documentary, media, and technological resources provided by the school and public libraries (Roux, 2008). Tea- chers should thus strongly encourage library use during school hours and invite their students to visit their neighbourhood li- brary to seek out new documentary sources for their school assignments, or simply to find books and other reading material suited to their interests. Integrating ICTs within the Pedagogical Content In the realm of reading acquisition, information and commu- nications technologies (ICTs) have been shown to be highly useful in helping students learn to read (Chen et al., 2011; Al- Barakat & Bataineh; 2011; Means, 2010; Lopez, 2010). What remains now is whether teachers make full use of these avail- able resources, such as reading on the computer screen, re- search on the Internet, discussion forums on specific topics, etc. It appears that an increasing number of teachers use these re- sources for the benefit of their students and the latter’s achi- evement in reading (Chen et al., 2011; Means, 2010; Lopez, 2010). Lopez (2010) discovered a strong correlation between student outcomes and the use of the interactive whiteboard in the classroom, while Means (2010) revealed the positive reper- cussions of using software when teaching mathematics and reading. In other studies, highly promising results have been obtained by using discussion forums, where the topics concerned both at-home and in-class reading activities, as well as the Internet to have students read directly on the computer rather than by con- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 489  Y. BOUCHAMMA ET AL. ventional means. Also emerging in the classroom are laptops which are increasingly used for reading activities (Jenkins, 2009; Sokal & Katz, 2008; Farris et al., 2009). In other words, today’s educators are looking to integrate new technologies within their teaching practices pertaining to literacy. In light of what we learned from the literature review, these are very sig- nificant results, as boys and girls are both very open to the pre- sence of different media in the classroom setting (Jenkins, 2009; Sokal & Katz, 2008; Farris et al., 2009). On the other hand, these findings do not agree with those of Slavin et al. (2011), who found no conclusive impact by the practice of using computers to enhance reading performance. Chen et al. (2011) also found no positive association between the use of new technologies and academic achievement but ra- ther an increased interest and motivation to learn (Chen et al., 2011; Jenkins, 2009; Farris et al., 2009). While it remains un- clear whether ICTs have a direct influence on student outcomes, they nevertheless do stimulate the students’ interest and moti- vation. Letting Students Choos e (Independent Reading) Our review of the literature highlights the importance of let- ting students choose certain texts to be studied in class, re- searched, or used in a test. Students also appreciate reading pe- riods during which they are free to read what they like (Bo- zack, 2011; Gibson, 2010; Davila & Patrick, 2010; Jenkins, 2009; Nichols & Cormack, 2009; Merisuo-Storm, 2006). We now know that boys are not only more motivated to read when they are allowed to choose their own books or texts but they ultimately perform better (Bozack, 2011; Gibson, 2010; Davila & Patrick, 2010), and that girls also like to choose their read- ing material and are less likely to be negatively affected than their male counterparts when the reading material is imposed by the teacher (Bozack, 2011; Jenkins, 2009; Nichols & Cor- mack, 2009). Many teachers allow their students to choose their books or texts. Giordano (2011) and Meyer (2010) reported that various reading activities regularly take place in the form of workshops, where the students are asked to choose books that interest them and that correspond to their specific needs during predeter- mined study periods and according to a prearranged system established by the teacher. Both of these authors emphasize that the book collection must be varied to include books that appeal to the reading preferences of each student (Giordano, 2011; Meyer, 2010). Individual and Group Tutoring According to Slavin (2011), individual tutoring is particu- larly effective in improving reading performance. The models that obtain the best results are phonetics-based methods, despite the fact that this approach is costly. One solution often used by schools to help students is group tutoring (student sub-groups), although this practice has not obtained the same positive results as the individual approach has. The Process-Based Approach Cooperative learning appears to be effective with students who have difficulty reading. In this approach, students learn from each other by explaining their understanding of what they have read, with the teacher serving as guide throughout the process (Slavin et al., 2011). Conclusion In this study, we identified the reading preferences of boys and girls. Our results show that boys are more interested in reading classroom textbooks, magazines, newspaper articles, and articles found on the Internet, and are more inclined to read electronic encyclopedias and to watch movies, while girls pre- fer reading novels, fiction, and books from the school or local library. Among these preferences, we also identified those that de- termine reading achievement, which in fact are the same for both boys and girls: reading novels or fiction, informative or non-fiction texts, and books or other reading material from the school library. Reading activities performed in class and the students’ participation in discussions pertaining to these reading activities are also significant in improving outcomes in reading. It must be noted that our analysis of the respective achieve- ment of boys and girls considered neither their personal, socio- economic, and cultural characteristics, nor those of the schools. Further studies should address certain control variables to in- terpret the results according to social or language groups (Fran- cophones, Anglophones, Allophones, & Native), socioecono- mic and cultural status, student history, etc. We also empha- size that these data were taken from a questionnaire and are representative of Canadian students, their reading preferences, and their respective outcomes. The questions focused on the frequency of use of the various texts read in class without delv- ing into their contents, which may be the subject of future qua- litative research. Our conclusions may have significant practical implications for teachers and other education professionals who strive to help students improve their reading skills. To address these needs and to fully stimulate their students’ interest in reading, teach- ers must provide them with a greater variety of reading material that better corresponds to their preferences. Teachers must also connect their in-class activities with the proposed assignments/homework. Our results show for exam- ple that using library resources is something both boys and girls generally enjoy, thus students may be asked to visit the school or local library to do research or to borrow relevant documents for an assignment. Finally, it is in the interest of educators to know that they do not necessarily have to use differentiation by literary genre when choosing reading material for their class. Our findings indicate that this method shows no indication of improving reading achievement in boys and girls. It is rather by individualized learning that teachers will come to maximize their students’ outcomes in reading. REFERENCES Al-Barakat, A. A., & Bataineh, R. F. (2011). Preservice childhood edu- cation teachers’ perceptions of instructional practices for developing young children’s interest in reading. Journal of Research in Child- hood Education, 25, 177-193. doi:10.1080/02568543.2011.556520 Below, J. L., Skinner, C. H., Fearrington, J. Y., & Sorell, C. A. (2010). Gender differences in early literacy: Analysis of kindergarten through fifth-grade dynamic indicators of basic early literacy skills probes. School Psychology Review, 39, 240-257. Bozack, A. (2011). Reading between the lines: Motives, beliefs and achievement in adolescent boys. Th e High Sch o o l J o u rnal, 94, 58-76. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 490  Y. BOUCHAMMA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 491 doi:10.1353/hsj.2011.0001 Burgess, S. R., & Jones K. K. (2010). Reading and media habits of college students varying by sex and remedial status. College Student Journal, 44, 492-508. Calvin, C. M., Fernandes, C., Smith, P., Visscher, P. M., & Deary, I. J. (2010). Sex, intelligence and educational achievement in a national cohort of over 175,000 11-year-old schoolchildren in England. Intel- ligence, 38, 424-432. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2010.04.005 Chapman, M., Filipenko, M., McTavish, M., & Shapiro, J. (2007). First graders’ preferences for narrative and/or information books and per- ceptions of other boys’ and girls’ book preferences. Canadian Jour- nal of Education, 30, 531-553. doi:10.2307/20466649 Chen, N.-S., Teng, D.-C., Lee, C.-H., & Kinshuk, N. (2011). Aug- menting paper-based reading activity with direct access to digital materials and scaffolded questioning. Computers & Education, 57, 1705-1715. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.03.013 Clanet, J. (2010). The relationship between teaching practices and stu- dent achievement in first year classes: A comparative study of small size and standard size classes. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 25, 192-206. doi:10.1007/s10212-010-0012-y Coddington, C. S., & Guthrie, J. T. (2009). Teacher and student percep- tions of boys’ and girls’ reading motivation. Reading Psychology, 30, 225-249. doi:10.1080/02702710802275371 Davila, D., & Patrick, L. (2010). Asking the experts: What children have to say about their reading preferences. Language Arts, 87, 199- 210. Farris, P. J., Werderich, D. E., Nelson, P. A., & Fuhler, C. J. (2009). Male call: Fifth-grade boys’ reading preferences. The Reading Tea- cher, 63, 180-188. doi:10.1598/RT.63.3.1 Gibson, S. (2010). Critical readings: African American girls and urban fiction. Journ al of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53, 565-574. doi:10.1598/JAAL.53.7.4 Giordano, L. (2011). Making sure our reading clicks. Reading Teacher, 64, 612-619. doi:10.1598/RT.64.8.7 Hairrell, A., Rupley, W. H., Edmonds, M., Larsen, R., Simmons, D., Will- son, V., Byrns, G., & Vaughn, S. (2011). Examining the impact of teacher quality on fourth-grade students’ comprehension and content- area achievement. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 27, 239-260. doi:10.1080/10573569.2011.560486 Haworth, C., Dale, S., & Plomin, R. (2010). Sex differences in school science performance from middle childhood to early adolescence. International Jour n a l f o r Educational Research, 49, 92-101. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2010.09.003 Jenkins, S. (2009). How to maintain school reading success: Five rec- ommendations from a struggling male reader. The Reading Teacher, 63, 159-162. doi:10.1598/RT.63.2.7 Koss, M. D., & Teale, W. H. (2009). What’s happening in young adult literature? Trends in books for adolescents, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52, 563-572. doi:10.1598/JAAL.52.7.2 Lai, F. (2010). Are boys left behind? The evolution of the gender achievement gap in Beijing’s middle schools. Economics of Educa- tion Review, 29, 383-399. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.07.009 Logan, S., & Johnston, R. (2009). Gender differences in reading ability and attitudes: Examining where these differences lie. Journal of Re- search in Reading, 32, 199-214. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9817.2008.01389.x Logan, S., & Johnston, R. (2010). Investigating gender differences in reading. Educational Review, 6 2 , 175-187. doi:10.1080/00131911003637006 Lopez, O. S. (2010). The digital learning classroom: Improving English language learners’ academic success in mathematics and reading us- ing interactive whiteboard technology. Computers & Education, 54, 901-915. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.09.019 Means, B. (2010). Technology and education change: Focus on student learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42, 285- 307. Meller, W. B., Richardson, D., & Hatch, J. A. (2009). Using read-alouds with critical literature in K-3 classrooms. Young Children, 64, 76-78. Meyer, K. E. (2010). A collaborative approach to reading workshop in the middle years. Reading Teacher, 63, 501-507. doi:10.1598/RT.63.6.7 Moeller, R. A. (2011). Aren’t these boy books? High school students’ readings of gender in graphic novels. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54, 476-484. doi:10.1598/JAAL.54.7.1 Logan, S., & Medford, E. (2011). Gender differences in the strength of association between motivation, competency beliefs and reading skill. Educational Research , 53, 85-94. doi:10.1080/00131881.2011.552242 Merisuo-Storm, T. (2006). Girls and boys like to read and write differ- ent texts. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50, 111- 125. doi:10.1080/00313830600576039 Nichols, S., & Cormack, P. (2009). Making boys at home in school? Theorising and researching literacy (dis)connections. English in Aus- tralia, 44, 47-59. Palumbo, A., & Sanacore, J. (2009). Helping struggling middle school literacy learners achieve success. Clearing House: A Journal of Edu- cational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 82, 275-280. doi:10.3200/TCHS.82.6.275-280 Roux, Y. R. (2008). Interview with a vampire, I mean, a librarian: When pre-service teachers meet practicing school librarians. Knowledge Quest, 37, 58-62. Sanacore, J., & Palumbo, A. (2010). Middle school students need more opportunities to read across the curriculum. Clearing House: A Jour- nal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83, 180-185. doi:10.1080/00098650903583735 Slavin, R. E., Lake, C., Davis, S., & Madden, N. A. (2011). Effective programs for struggling readers: A best-evidence synthesis. Educa- tional Research Review, 6, 1-26. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2010.07.002 Small, R. V., Snyder, J., & Parker, K. (2009). The impact of New York’s school libraries on student achievement and motivation: Phase I. School Library Media Research, 12, 23. Sokal, L., & Katz, H. (2008). Effects of technology and male teachers on boys’ reading. Australian Journal of Education, 52, 81-94. doi:10.1177/000494410805200106 Statistics Canada (2010). À la hauteur: Résultats canadiens de l’étude PISA de l’OCDE—La performance des jeunes du Canada en lecture, en mathématiques et en sciences—Premiers résultats de 2009 pour les Canadiens de 15 ans. 81-590-XPF, 1-84. Watson, A., Kehler, M., & Martino, W. (2010). The problem of boys’ literacy underachievement: Raising some questions. Journal of Ado- lescent & Adult Literacy, 53, 356-361. doi:10.1598/JAAL.53.5.1 Williams, L. M. (2008). Book selections of economically disadvantag- ed black elementary students. The Journal of Educational Research, 102, 51-63. doi:10.3200/JOER.102.1.51-64 Wilson, J. D., & Casey, L. H. (2007). Understanding the recreational reading patterns of secondary students. Reading Improvement, 44, 40- 49.

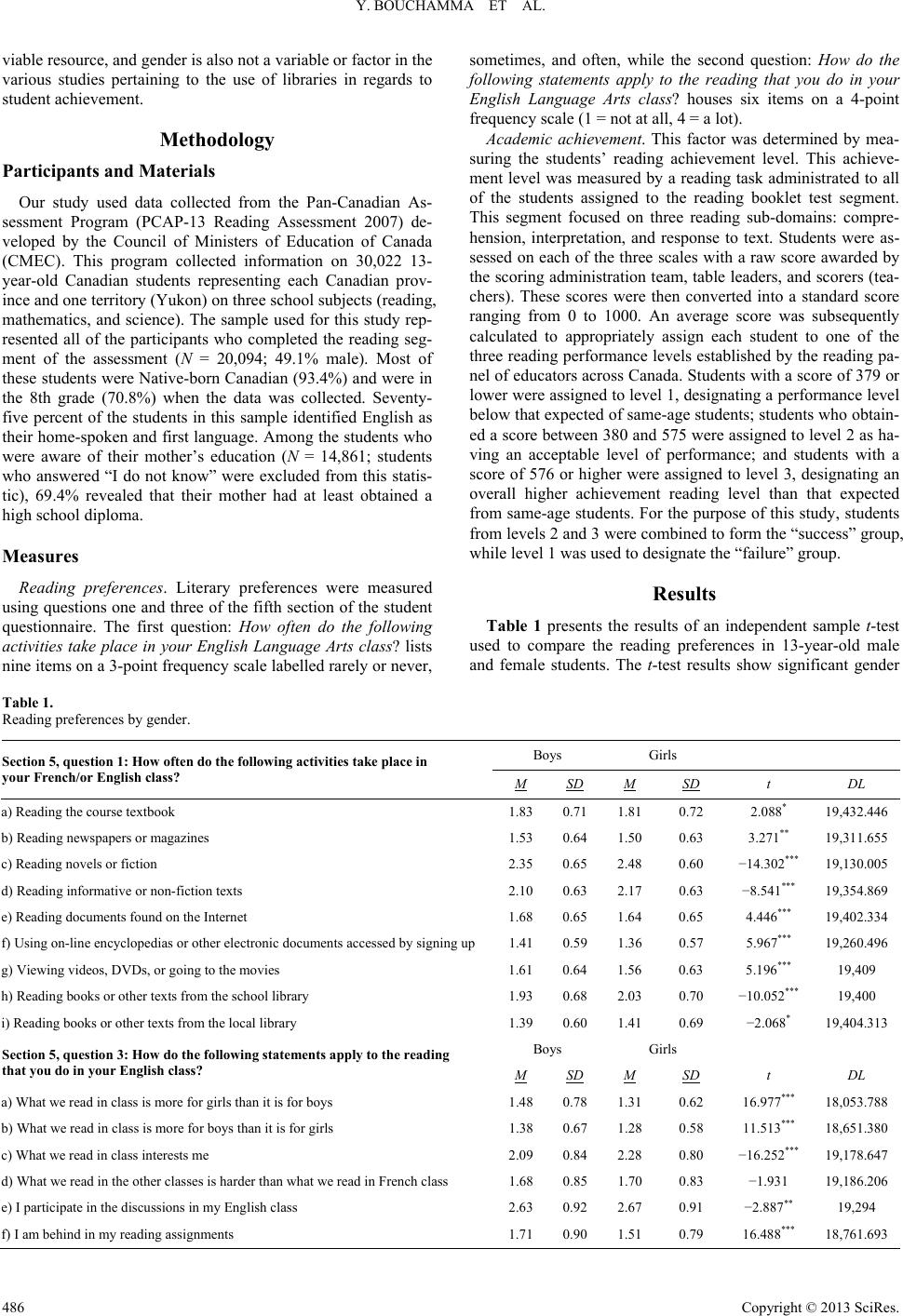

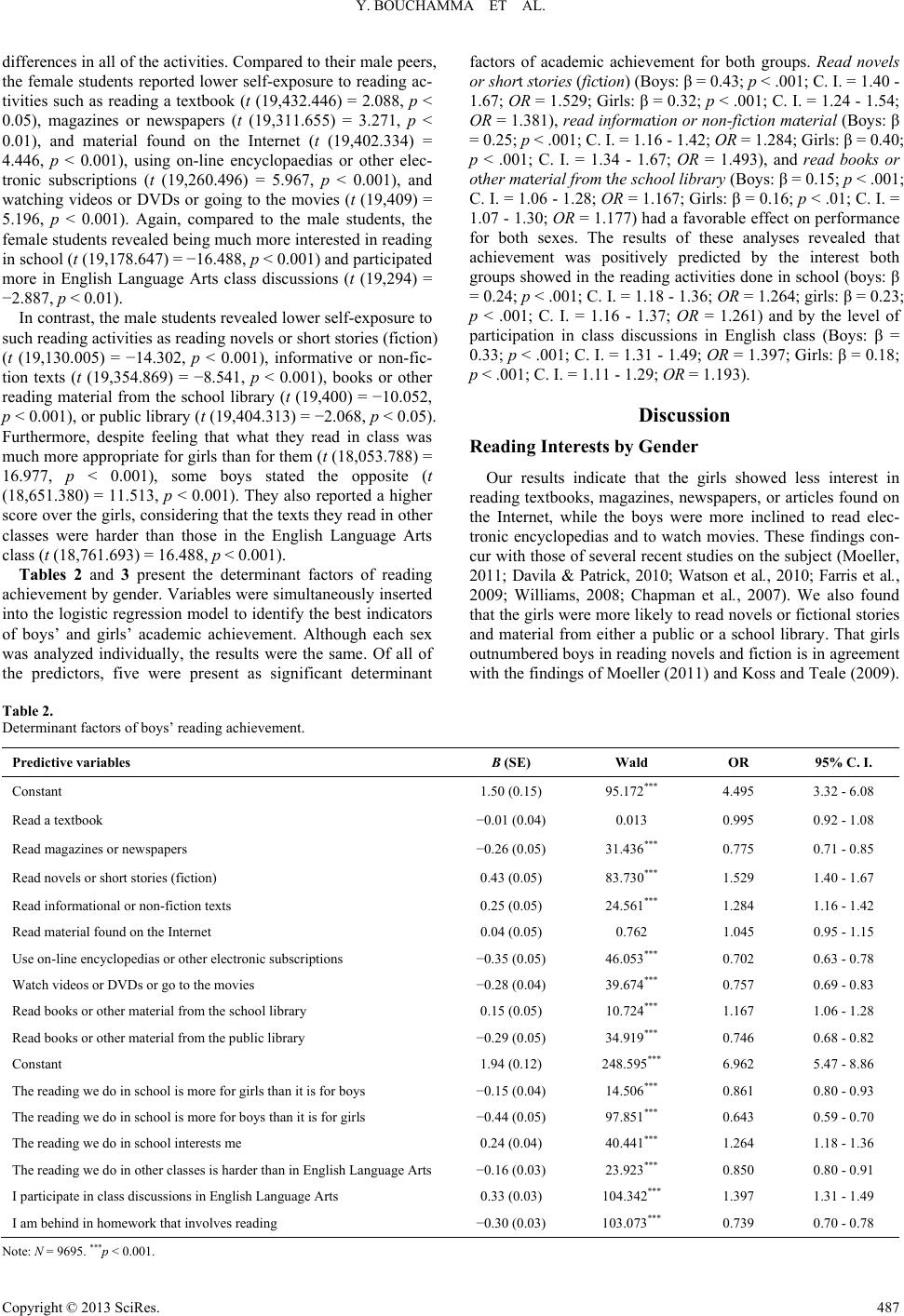

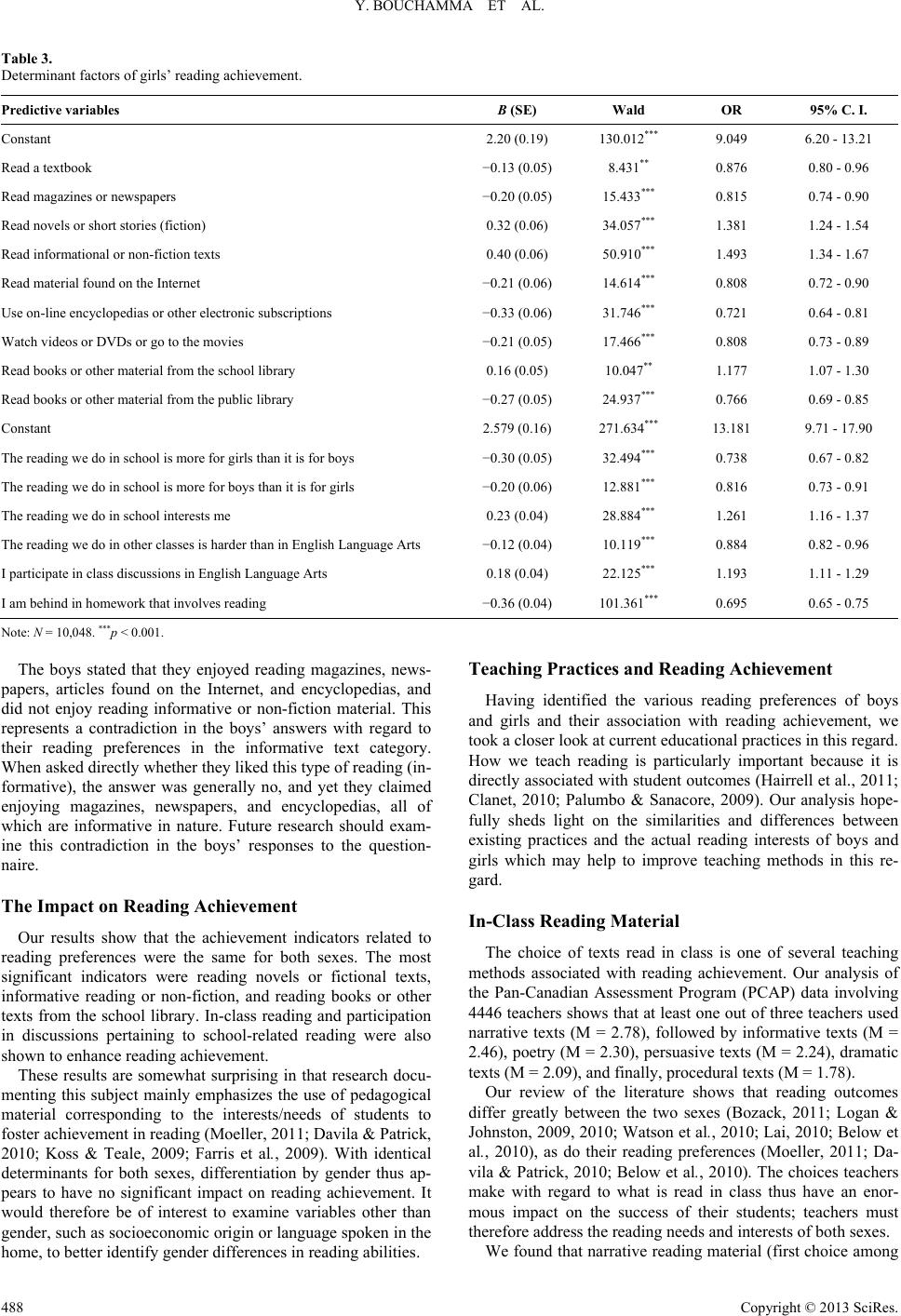

|