Paper Menu >>

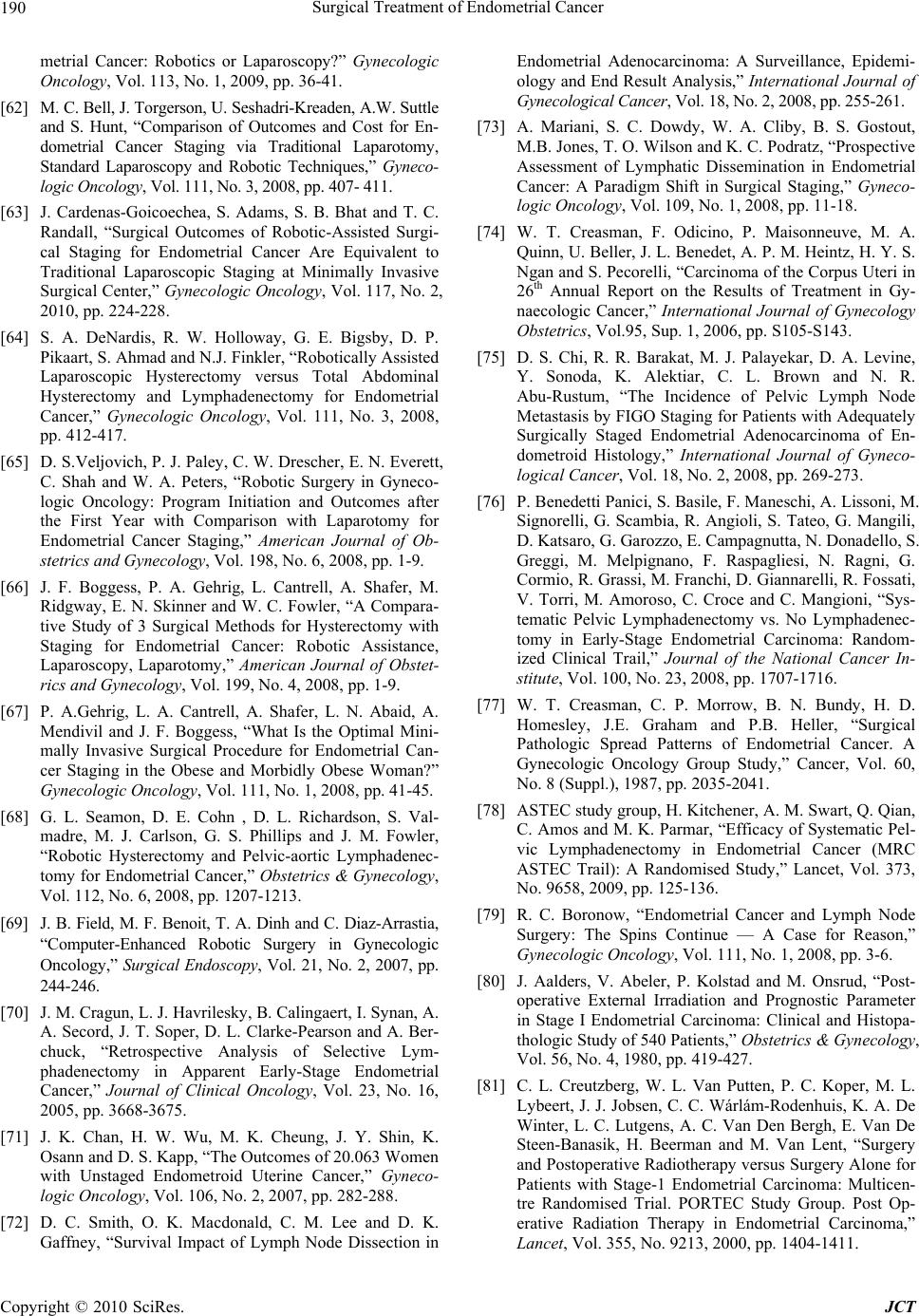

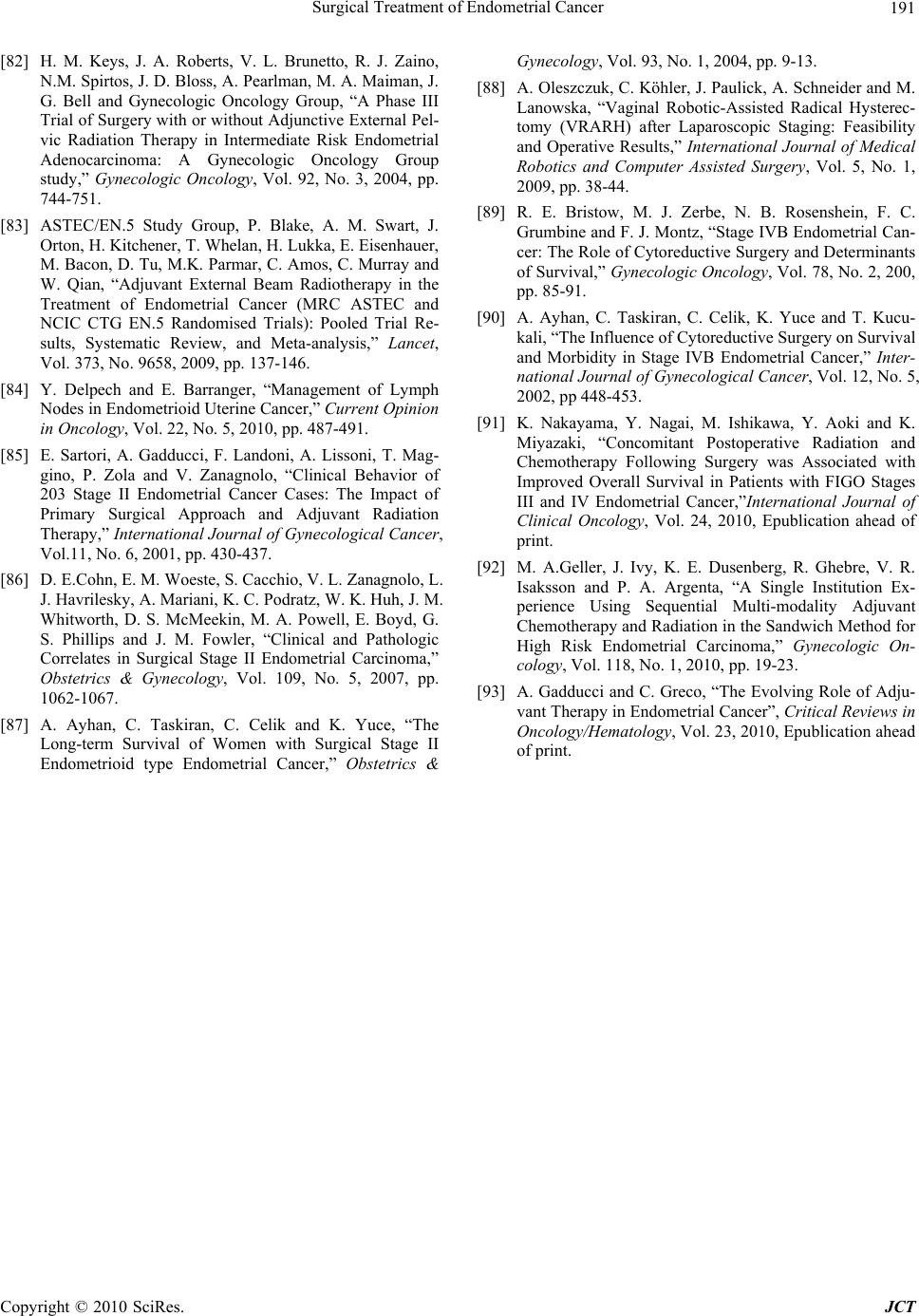

Journal Menu >>

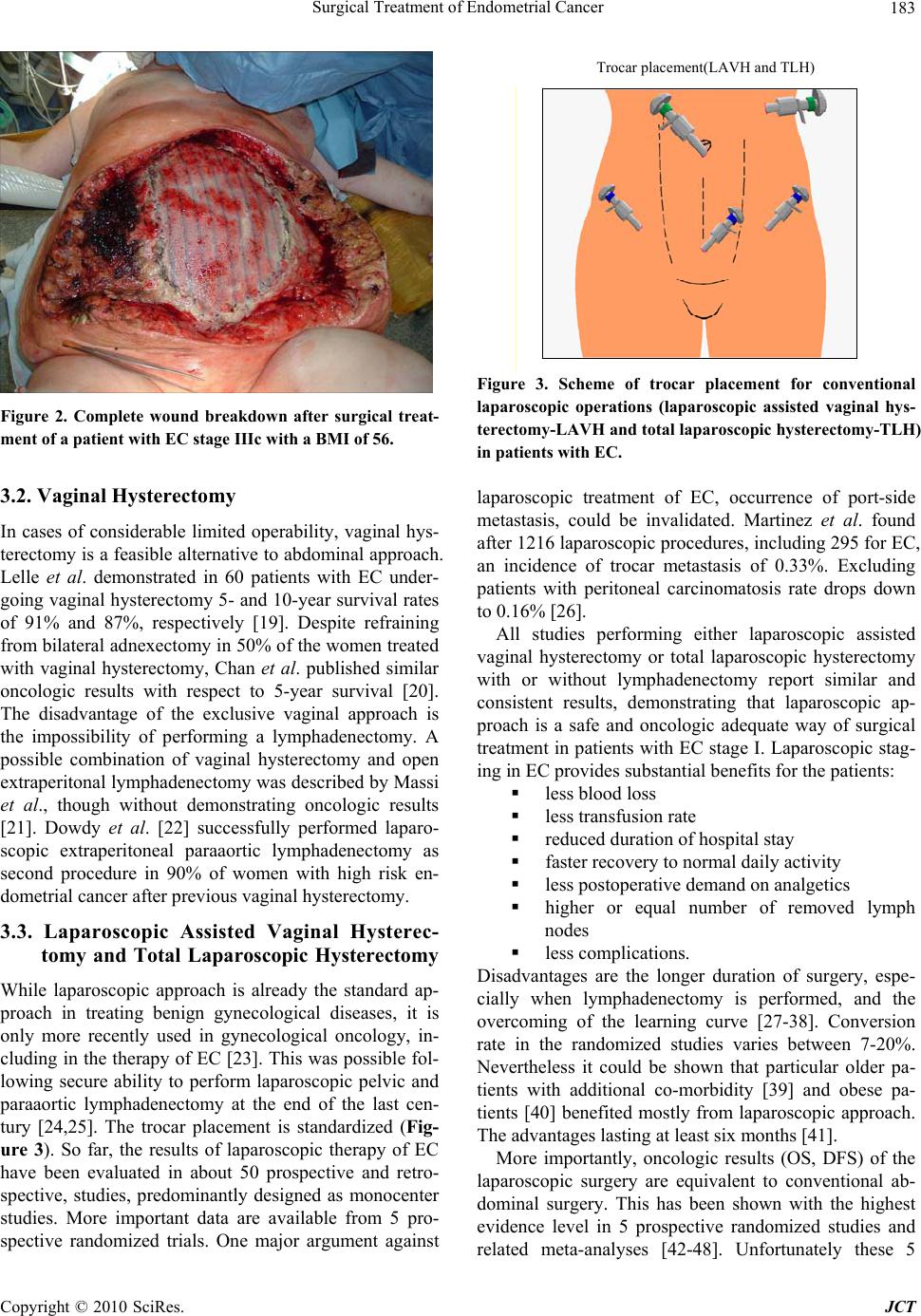

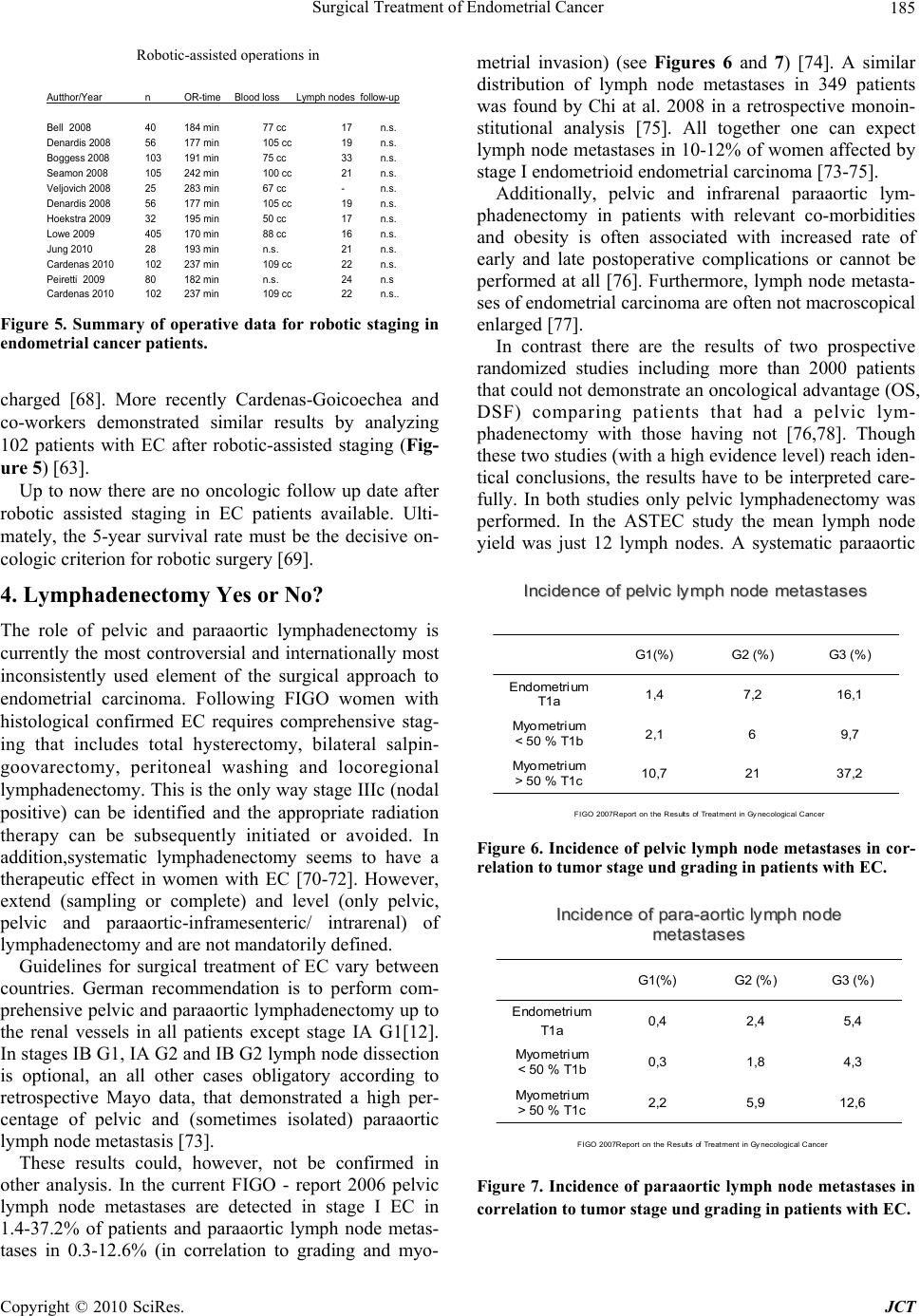

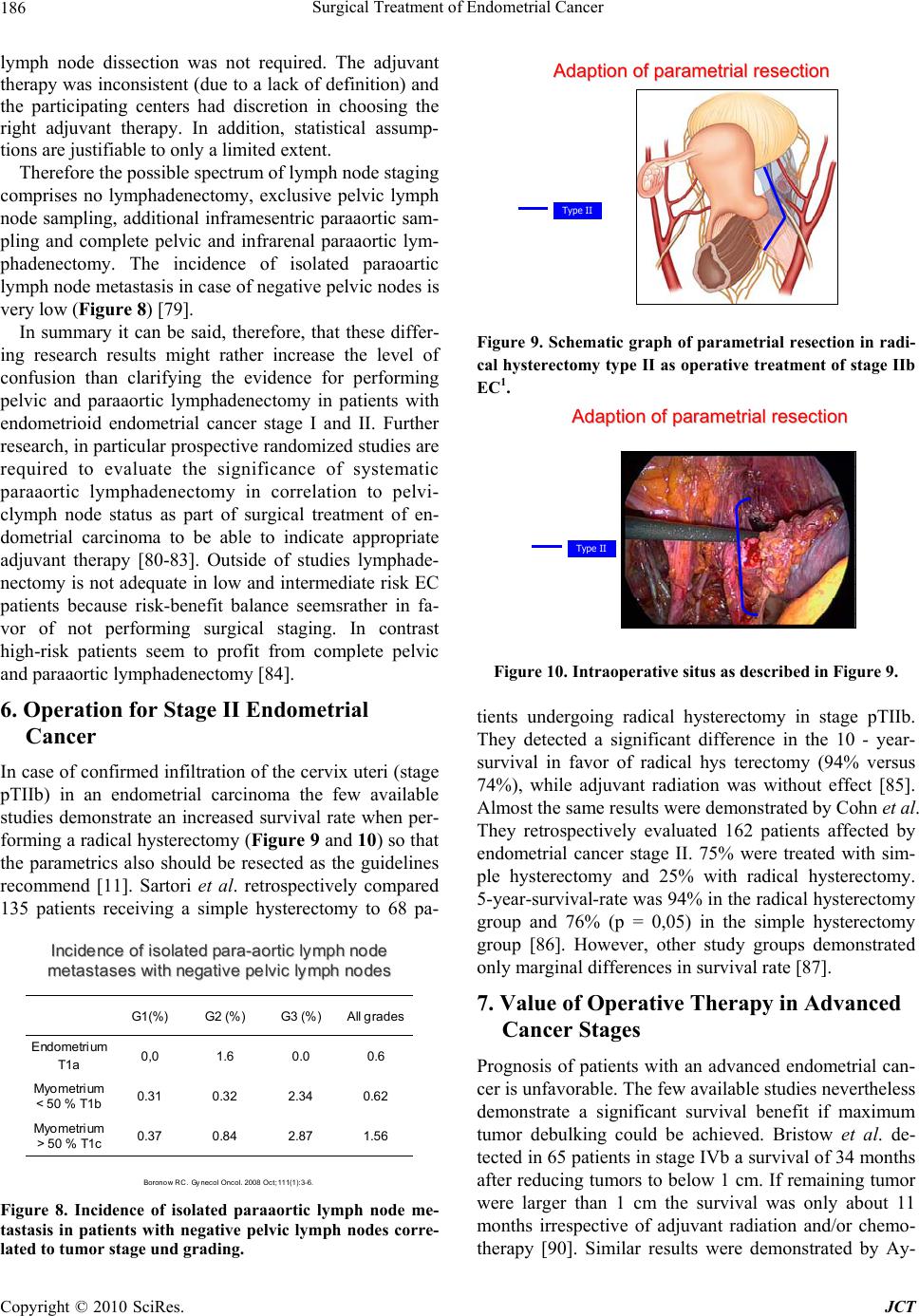

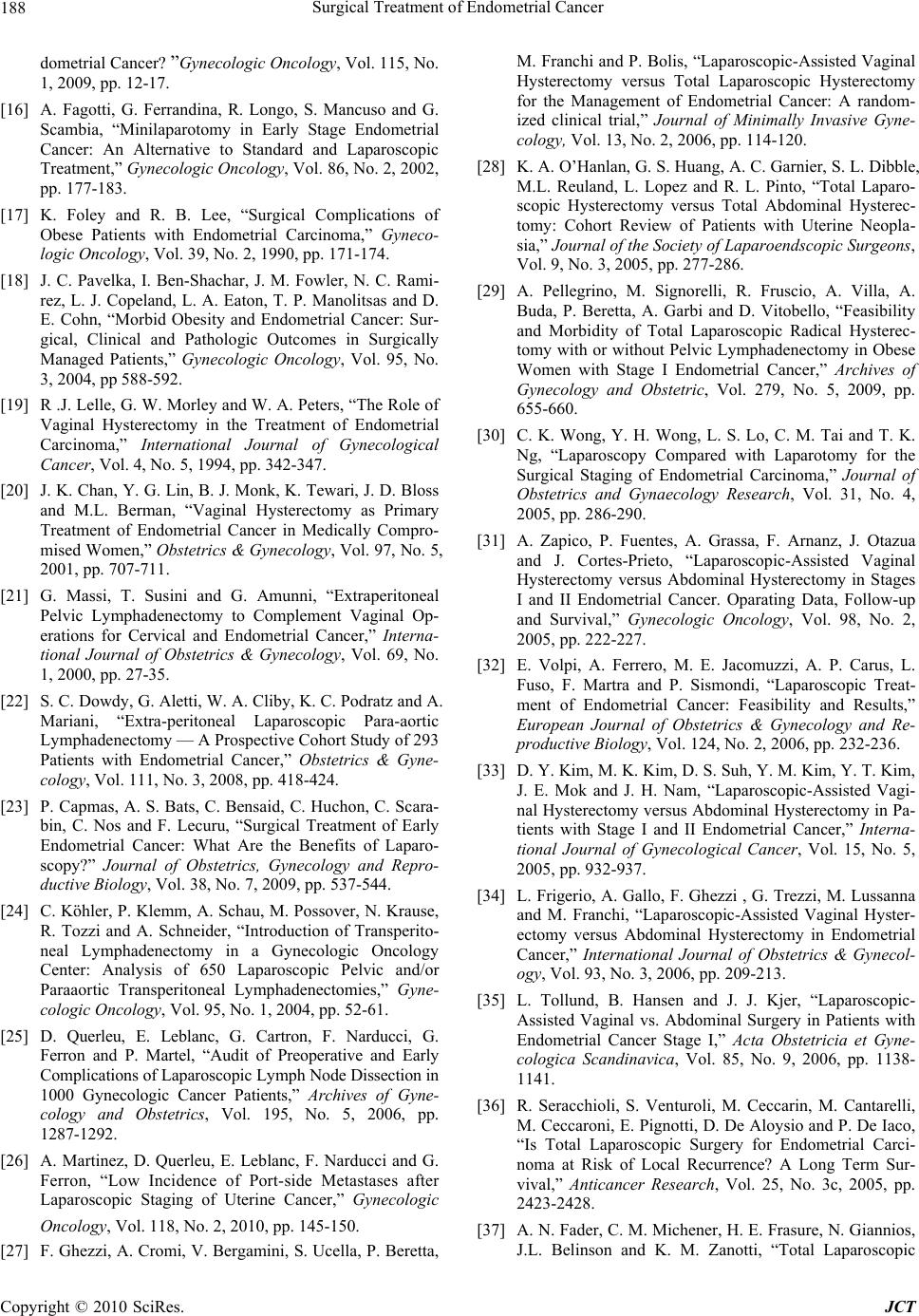

Journal of Cancer Therapy, 2010, 1, 181-191 doi:10.4236/jct.2010.14028 Published Online December 2010 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jct) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 181 Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Malgorzata Lanowska1, Verena Brink-Spalink1, Kati Hasenbein1, Achim Schneider1, Simone Marnitz 2, Christhardt Köhler 1 1Department of Gynecology, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Campus Mitte; 2Department of Radiooncology, Charité University Medicine Berlin. Email: christhardt.koehler@ch arite.de Received July 23rd, 2010; revised July 26th, 2010; accepted August 3rd, 2010. ABSTRACT Each year endometrial cancer is diagnosed in approximately 11.700 women in Germany. Operation is the therapy of choice in the primary treatment of patients with endometrial cancer. The traditional abdominal approach, vaginal, laparoscopic and ro botic-assisted methods are available for the surgical treatment of EC today. Th is article compares and evaluates these different treatment options. With rising incidence of obesity, number of patients with endometrial cancer will also increase. However, operations in obese patients are more challenging. Laparotomy as standard ther- apy in endometrial cancer patients stage I and II should be replaced by laparoscopic approaches. Laparoscopy is on- cologically adequate to open procedures and offers many advantages to patients. Robotic surgery in the treatment of endometrial cancer is still under eva luation. Most controversial po ints of treatment today are indication and extention of lymphadenectomy in different stages. In advanced tumor stages, optimal debulking should be performed in order to improve effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapeutic and/or radiation therapy. Keywords: Endometrial Cancer, Operative Therapy, Laparoscopic Treatment, Robotic–assisted Hysterectomy, Fertil- ity-preserving Therapy 1. Introduction Each year endometrial cancer (EC) is diagnosed in ap- proximately 11. 700 women in Germany. More than 80% are, fortunately, detected in the prognostic favourable stages I and II [1]. In comparison 41.200 women were diagnosed with EC in the United States in 2006, a sub- stantial increased from 35.000 in 1987 [2]. The most important risk factors for the development of EC are obesity, postmenopausal status and unopposed estrogen use (Type I EC). Despite the lack of systematic data for the steady rise of overweight patients in Germany there seems to be a similar trend for the incidence of adipos ity comparable to America (Figure 1). Fewer patients with EC are rather thin, have no history of exogenous estro- gen exposure (Type II EC), are perimenopausal (20-25%) or younger than 40 year s. The average age of women with EC is 68 years. Therefore many patients are affected by additional rele- vant co-morbidities [3]. Combination of uterine corpus cancer with adiposity, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease and/or other internal diseases increases sur- gical-anesthesiological risk is the major gynaecologic oncologic challenge in the current century. However, chronological age by itself is not a reason for higher pe- rioperative morbidity and mortality [4]. In addition to the traditional abdominal approach, vaginal, laparoscopic and robotic-assisted methods are also available for the surgical treatment of EC today. Obesity Trends* Among U.S. Adults BRFSS, 2008 (*BMI ≥30, or ~ 30 lbs. overweight for 5’4”person) No Data <10% 10%–14%15%–19% 20%–24% 25%–29% ≥30% Germany: BMI >30 2005 14% Increase of 2% compared to 1999 Figure 1. Obesity trend US 2008.  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 182 This article compares and evaluates these different treatment options. 2. Fertility Preserving Operat ion Approximately 5% of the patients affected by EC are younger than 40 years. Some of them wish to preserve fertility. The decision for uterus conservation is compli- cated by the fact that in patients with EC stage IA grad- ing 1 one can find in 10%-45% synchronous ovarian tu- mors. Additionally, in up to 10% of cases myometrial infiltration is histologically confirmed in spite of a nega- tive MRI and a higher grading than in the D&C is de- tected in nearly 20% of cases. The accuracy of MRI to detect myometrial invasion is 70% [5]. Until today there are only a few case series or case reports available. All patients described in these publications were staged by imaging systems, even though PET-CT has been shown (in a small study) to have a sensitivity for detection of pelvic lymph node metastasis of only 67% [6]. The range of described conservative therapy modali- ties is broad and comprises gestagen therapy, intrauterin e insertion of MIRENA®, oral application of aromatase inhibitors, GnRH analoga or hysteroscopic resection of EC in combination with hormon al treatment. It is impor- tant to advise these patients carefully about individual treatment, thus high compliance and understanding are paramount. After informed consent has been obtained, following criteria must be fulfilled: gradin g 1 carcinoma no myometrial infiltration in MRI or sonogra- phy no detection of suspicious pelvic or paraaortic lymph nodes no evidence of adnexal tumos no contraindica tion for ho r monal treat ment agreement for close follow-up (curettage every 3 month) stage adjusted therapy after finishing desire for childbearing Chiva et al. summarized data of 133 women with fer- tility preserving therapy in EC. 76% of patients re- sponded to hormonally therapy. However, 34% of women developed recurrence after a mean of 20 months. In 24% of patients there was no response to hormonal therapy. 53 pregnancies occurred but also 4 treatment- related deaths [7] . It is advisable, that young patients with clinical stage IA G1 EC should undergo staging laparoscopy after in- formed counselling to exclude secondary ovarian neop la- sia and lymph node metastases before starting hormonal therapy. After finishing family planning stage-adjusted operative (and radiation) therapy has to be initiated, fre- quently resulting in the discovery of higher tumor stages than initially diagnosed [8]. Ovarian preservation during surgical management of early stage endometrial cancer is still under debate and should be done only individually after extensive discussion and informed consent with the patient [9-11]. 3. Operative Therapy Stage I Endometrial Cancer The German Gynecologic Oncology Group’s (AGO) guideline for surgical treatment of endometroid EC, in line with many international guidelines, includes an in- traperitoneal cytology sample, total hysterectomy, bilat- eral adnexectomy and pelvic (at least 15 lymph nodes) and paraaortic (at least 10 lymph nodes) lymphadenec- tomy up to the renal vessels. In case of uterine papil- lary-serous carcinoma or clear cell carcinoma it is man- datory to extract multiple perito n eal samples as well as to perform omentectomy [12]. In clinical stages IA G1 and G2 and IB G1 and G2 lymphadenectomy is optional. In patients with relevant co-morbidities it is acceptable to omit lymphadenectomy, even in higher clinical stages. Systematic surgical staging, including simple hysterec- tomy with bilateral adnexectomy and p elvic and paraaor- tic lymphonodectomy is for most of the women affected by EC the baseline therapy and allows clear decision for stage-related adjuvant therapy. More extensive pa- rametrial resection (radical hysterectomy) does not im- prove oncologic outcome in patients with stage I endo- metrial cancer [13]. However, definitive histologic grad- ing, myometrial invasion and lymph node involvement differ in a substantial rate from intraoperative gross as- sessment (up to 15%) and frozen section result (up to 25%) [14,15]. Therefore decision on comprehensiveness of surgical treatment is challenging. 3.1. Abdominal Hysterectomy with Bilateral Salpingoophorectomy (BSO) Most patients affected by histological proven EC today still undergo surgical treatment by abdominal approach. In most cases a midline longitudinal laparotomy is per- formed that starts above the pubic symphysis and (de- pending on the extension of the lymphadenectomy) ex- pands until the x iph oid. Alternativ e ways of lap aroto mies are a wide Pfannenstiel incision (optionally with trans- section of the Mm. recti) or laparotomy including a pan- niculectomy [16]. With increasing BMI rate of successful lymphadenectomies is however significantly decreasing. The estimated blood loss rises and duration of surgery extends [17]. In morbidly obese patients noninfectious wound breakdown occurs in up to 10% (Figure 2) [18].  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 183 Figure 2. Complete wound breakdown after surgical treat- ment of a patient with EC stage IIIc wi th a BM I of 56. 3.2. Vaginal Hysterectomy In cases of considerable limited operability, vaginal hys- terectomy is a feasible alternative to abdominal appro ach. Lelle et al. demonstrated in 60 patients with EC under- going vaginal hysterectomy 5- and 10-year survival rates of 91% and 87%, respectively [19]. Despite refraining from bilateral adnexectomy in 50% of the women treated with vaginal hysterectomy, Chan et al. published similar oncologic results with respect to 5-year survival [20]. The disadvantage of the exclusive vaginal approach is the impossibility of performing a lymphadenectomy. A possible combination of vaginal hysterectomy and open extraperitonal lymphadenectomy was described by Massi et al., though without demonstrating oncologic results [21]. Dowdy et al. [22] successfully performed laparo- scopic extraperitoneal paraaortic lymphadenectomy as second procedure in 90% of women with high risk en- dometrial cancer after previous vaginal hysterectomy. 3.3. Laparoscopic Assisted Vaginal Hysterec- tomy and Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy While laparoscopic approach is already the standard ap- proach in treating benign gynecological diseases, it is only more recently used in gynecological oncology, in- cluding in the therapy of EC [23]. This was possible fol- lowing secure ability to perform laparoscopic pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy at the end of the last cen- tury [24,25]. The trocar placement is standardized (Fig- ure 3). So far, the results of laparoscopic therapy of EC have been evaluated in about 50 prospective and retro- spective, studies, predominantly designed as monocenter studies. More important data are available from 5 pro- spective randomized trials. One major argument against Figure 3. Scheme of trocar placement for conventional laparoscopic operations (laparoscopic assisted vaginal hys- terectomy-LAVH and total laparoscopic hysterectomy-TLH) in patients with EC. laparoscopic treatment of EC, occurrence of port-side metastasis, could be invalidated. Martinez et al. found after 1216 laparoscopic procedures, including 295 for EC, an incidence of trocar metastasis of 0.33%. Excluding patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis rate drops down to 0.16% [26]. All studies performing either laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy with or without lymphadenectomy report similar and consistent results, demonstrating that laparoscopic ap- proach is a safe and oncologic adequate way of surgical treatment in patients with EC stage I. Laparoscopic stag- ing in EC provides substantial benefits for the patients: less blood loss less transfusion rate reduced duration of hospital stay faster recovery to normal daily activity less postoperative demand on analgetics higher or equal number of removed lymph nodes less complications. Disadvantages are the longer duration of surgery, espe- cially when lymphadenectomy is performed, and the overcoming of the learning curve [27-38]. Conversion rate in the randomized studies varies between 7-20%. Nevertheless it could be shown that particular older pa- tients with additional co-morbidity [39] and obese pa- tients [40] benefited mostly from laparoscopic approach. The advantages lasting at least six months [41]. More importantly, oncologic results (OS, DFS) of the laparoscopic surgery are equivalent to conventional ab- dominal surgery. This has been shown with the highest evidence level in 5 prospective randomized studies and related meta-analyses [42-48]. Unfortunately these 5 Trocar placement(LAVH and TLH)  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 184 studies include only 238 patients in the groups that un- derwent laparoscopic surgery. If the results of further randomized studies like the Dutch multicenter trial NTR 821 and GOG LAP II should confirm these results, every patient affected by EC stage I should be offered a laparoscopic surgical therapy, and abdominal approach should only be chosen and accepted in cases of severe contraindication s [ 49,50]. 3.4. Robotic-assisted Hysterectomy With approval of the DaVinci® Surgical System by the FDA in 2005, a new era of laparoscopic technique in gynecology began. This technique will potentially be able to overcome prejudices and resistances against laparoscopic oncological surgery. Robotic-assisted laparoscopy offers substantial advan- tages such as a three-dimensional vision system, im- proved precision of instruments combined with poten- tially more degrees of freedom, tremor-free manipulation, an advanced ergonomic positioning of the surgeon and a faster learning curve, which is helpful in particular in complex gynecological procedures. The disadvantages of robotic-assisted surgery are the absence of tactile feed- back, the large size of robotic equipment, the lack of vaginal access and larger skin incisions for inserting tro- cars [51-55]. Moreover, costs for robotic staging of EC patients are significant higher, approximately 1300$ per operation, due to longer operating room time and dis- posable instruments compared to traditional laparoscopy [56]. After passing the learning curve of about 20 opera- tions [57] many authors consider robotic-assisted surgery to be an ideal combination of the advantages of abdomi- nal and laparoscopic approach [58-60]. This new method of surgery is advantageous in comparison to the conven- tional abdominal approach and might even perform better than the conventional-laparoscopic surgery in relation to operative times, blood loss and postoperative hospital stay [61-63] which has however still to be confirmed by further studies. De Nardis et al. compared 2008 the sur- gical morbidity of 56 patients affected by EC clinical stage I after undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy with a group of 106 patients who underwent abdominal approach. Three (5.4%) originally planned robotic-assisted operations needed to be converted to abdominal approach. Intraop- erative blood loss, rate of perioperative complications (3.6% vs. 20.8%) and duration of hospital stay were sig- nificantly favorable in the DaVinci-group, but operative times were substantially longer. The lymph node yields were comparable. These results have to be interpreted cautiously because of differences in the characteristics of the groups of patients, with the group achieving ro- botic-assisted surgery containing younger and slimmer women with less co-morbidities and earlier clinical stages of EC [64]. Veljovich et al. performed a similar study and com- pared 118 patients after robotic operations with 131 women undergoing an open abdominal surgery and could demonstrate longer operative times for robotic surgery but also a significantly lower blood loss and a considera- bly shorter hospital stay. The lymph node yields were as well comparable [65]. Boggess et al. compared three possible ways to performing an extensive EC staging: abdominal approach (n = 138), conventional laparoscopic (n = 81) und robotic-assisted (n = 103). The blood loss was lowest in the DaVinci-group, the lymph node yields were significantly higher and the hospital stays shortest. The operative times were comparable in the robotic-assisted and conventional laparoscopy, but longer than by laparotomy. Boggess inserted five trocars for his operation (Figure 4); a placement, that is now used by many other centres. The complication rates of the robotic-assisted opera- tions were significantly lower than in the laparotomy group (5.9% vs. 29.7%). There was no difference in the conversion rates between conventional and robotic- as- sisted laparoscopy [66]. Analyzing the subgroup of obese and morbid obese patients, there is an considerable ad- vantage in using the robot compared to conventional laparoscopy, including shorter operative times, less blood loss and higher lymph node yields [67]. Comparable fa- vorable results were demonstrated by Seamon et al. 2008. Only 12.4% of the o riginally planned 105 rbotic-assisted operations had to be converted, especially in morbid obese patients. The mean operative time was 242 minutes, the blood loss 99 cc, the lymph node yields 29. 24 hours later most of the patients were in the condition to get dis- Port placement robotic staging endometrial cancer Endoscop12 mm Additional trocar12 mm DaVinci trocars8 mm 8-10 cm 23 –25 cm up to symphysis Figure 4. Schematic demonstration of the port-placement in robotic-assisted operation for endometrial carcinoma.  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 185 Autthor/YearnOR-timeBlood lossLymph nodesfollow-up Bell200840184 min77 cc17n.s. Denardis 200856177 min105 cc19n.s. Boggess 2008103191 min75 cc33n.s. Seamon 2008105242 min100 cc21n.s. Veljovich 200825283 min67 cc-n.s. Denardis 200856177 min105 cc19n.s. Hoekstra 200932195 min50 cc17n.s. Lowe 2009405170 min88 cc16n.s. Jung 201028193 minn.s.21n.s. Cardenas 2010102237 min109 cc22n.s. Peiretti200980182 minn.s.24n.s Cardenas 2010102237 min109 cc22n.s.. Figure 5. Summary of operative data for robotic staging in endometrial cancer patients. charged [68]. More recently Cardenas-Goicoechea and co-workers demonstrated similar results by analyzing 102 patients with EC after robotic-assisted staging (Fig- ure 5) [63]. Up to now there are no oncologic follow up date after robotic assisted staging in EC patients available. Ulti- mately, the 5-year survival rate must be the decisive on- cologic criterion for robotic surgery [69]. 4. Lymphadenectomy Yes or No? The role of pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy is currently the most controversial and internationally most inconsistently used element of the surgical approach to endometrial carcinoma. Following FIGO women with histological confirmed EC requires comprehensive stag- ing that includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpin- goovarectomy, peritoneal washing and locoregional lymphadenectomy. This is the on ly way stage IIIc (nodal positive) can be identified and the appropriate radiation therapy can be subsequently initiated or avoided. In addition,systematic lymphadenectomy seems to have a therapeutic effect in women with EC [70-72]. However, extend (sampling or complete) and level (only pelvic, pelvic and paraaortic-inframesenteric/ intrarenal) of lymphadenectomy and are not mandatorily defined. Guidelines for surgical treatment of EC vary between countries. German recommendation is to perform com- prehensive pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy up to the renal vessels in all patients except stage IA G1[12]. In stages IB G1, IA G2 and IB G2 lymph node dissection is optional, an all other cases obligatory according to retrospective Mayo data, that demonstrated a high per- centage of pelvic and (sometimes isolated) paraaortic lymph node metastasis [73]. These results could, however, not be confirmed in other analysis. In the current FIGO - report 2006 pelvic lymph node metastases are detected in stage I EC in 1.4-37.2% of patients and paraaortic lymph node metas- tases in 0.3-12.6% (in correlation to grading and myo- metrial invasion) (see Figures 6 and 7) [74]. A similar distribution of lymph node metastases in 349 patients was found by Chi at al. 2008 in a retrospective monoin- stitutional analysis [75]. All together one can expect lymph node metastases in 10-12% of women affected by stage I endometrioid endometrial carcinoma [73-75]. Additionally, pelvic and infrarenal paraaortic lym- phadenectomy in patients with relevant co-morbidities and obesity is often associated with increased rate of early and late postoperative complications or cannot be performed at all [76]. Furthermore, lymph node metasta- ses of endometrial carcinoma are often not macroscopical enlarged [77]. In contrast there are the results of two prospective randomized studies including more than 2000 patients that could not demonstrate an oncological advantage (OS, DSF) comparing patients that had a pelvic lym- phadenectomy with those having not [76,78]. Though these two studies (with a high eviden ce level) reach id en- tical conclusions, the results have to be interpreted care- fully. In both studies only pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed. In the ASTEC study the mean lymph node yield was just 12 lymph nodes. A systematic paraaortic G1(%) G2 (%)G3 (%) Endometri um T1a 1,47,2 16,1 Myometrium < 50 % T1b2,1 69,7 Myometrium > 50 % T1c10,721 37,2 FIGO 2007Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer I n ci dence Incidence of of pelvic pelvic lymph lymph no de node metastases metastases Figure 6. Incidence of pelvic lymph node metastases in cor- relation to tumor stage und grading in patients wi th EC. FIGO 2007Report on the Resultsof Treatment in Gynecological Cancer Incidence I nc id ence of o f para pa r a- -aortic aort i clymp h l ymp h node no d e metastases metastases G1(%) G2 (%)G3 (%) Endometrium T1a 0,42,4 5,4 Myometrium < 50 % T1b0,3 1,8 4,3 Myometrium > 50 % T1c2,25,9 12,6 Figure 7. Incidence of paraaortic lymph node metastases in correlation to tumor stage und grading in patients wi th EC. Robotic-assisted o p erations in  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 186 lymph node dissection was not required. The adjuvant therapy was inconsistent (due to a lack of definition) and the participating centers had discretion in choosing the right adjuvant therapy. In addition, statistical assump- tions are justifiable to only a limited extent. Therefore the possible spectrum of lymph node staging comprises no lymphadenectomy, exclusive pelvic lymph node sampling, additional inframesentric paraaortic sam- pling and complete pelvic and infrarenal paraaortic lym- phadenectomy. The incidence of isolated paraoartic lymph node metastasis in case of negative pelvic nodes is very low (Figure 8) [79]. In summary it can be said, therefore, that these differ- ing research results might rather increase the level of confusion than clarifying the evidence for performing pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer stage I and II. Further research, in particular prospective randomized studies are required to evaluate the significance of systematic paraaortic lymphadenectomy in correlation to pelvi- clymph node status as part of surgical treatment of en- dometrial carcinoma to be able to indicate appropriate adjuvant therapy [80-83]. Outside of studies lymphade- nectomy is not adequate in low and intermediate risk EC patients because risk-benefit balance seemsrather in fa- vor of not performing surgical staging. In contrast high-risk patients seem to profit from complete pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy [84]. 6. Operation for Stage II Endometrial Cancer In case of confirmed infiltration of the cervix uteri (stage pTIIb) in an endometrial carcinoma the few available studies demonstrate an increased survival rate when per- forming a radical hysterectomy (Figure 9 and 10) so that the parametrics also should be resected as the guidelines recommend [11]. Sartori et al. retrospectively compared 135 patients receiving a simple hysterectomy to 68 pa- I ncidence Incidence of of isolated isolated pa r a pa ra- -aortic aorticlym ph lymphnode node metastases metastases with with negative negative pelv ic pelviclymph lymph node s node s G1(%) G2 (%)G3 (%)All grades Endometrium T1a 0,0 1.6 0.0 0.6 Myometri um < 50 % T1b0.31 0.322.340.62 Myometri um > 50 % T1c0.37 0.842.87 1.56 BoronowRC. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Oct;111(1):3-6. Figure 8. Incidence of isolated paraaortic lymph node me- tastasis in patients with negative pelvic lymph nodes corre- lated to tumor stage und grading. Adaption of Adaption of parametrial parametrial resection resection Type II Figure 9. Schematic graph of parametrial resection in radi- cal hysterectomy type II as operative treatment of stage IIb EC1. Adaption of Adaption of parametrial parametrialres ection resection Type II Figure 10. Intraoperative situs as described in Figure 9. tients undergoing radical hysterectomy in stage pTIIb. They detected a significant difference in the 10 - year- survival in favor of radical hys terectomy (94% versus 74%), while adjuvant radiation was without effect [85]. Almost the same results were demonstrated by Cohn et al. They retrospectively evaluated 162 patients affected by endometrial cancer stage II. 75% were treated with sim- ple hysterectomy and 25% with radical hysterectomy. 5-year-survival-rate was 94% in the radical hysterectomy group and 76% (p = 0,05) in the simple hysterectomy group [86]. However, other study groups demonstrated only marginal differences in survival rate [87]. 7. Value of Operative Therapy in Advanced Cancer Stages Prognosis of patients with an advanced endometrial can- cer is unfavorable. The few availab le studies n evertheless demonstrate a significant survival benefit if maximum tumor debulking could be achieved. Bristow et al. de- tected in 65 patients in stage IVb a survival of 34 months after reducing tumors to below 1 cm. If remaining tumor were larger than 1 cm the survival was only about 11 months irrespective of adjuvant radiation and/or chemo- therapy [90]. Similar results were demonstrated by Ay-  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 187 han et al. in 37 patients in stage IVb. If tumor could be reduced below 1 cm survival was 25 months. In case of no macroscopic residual tumor survival was even 48 months. In contrast women who did achieve only subop- timal tumor reduction survived only 13 months [90]. In advanced stages maximum tumor debulking should thus be performed in order to improve effectiveness of adju- vant chemotherapeutic and/or radiation therapy [12]. Combination of maximum cytoreductive surgery and adjuvant use of radiation and chemotherapy sequentially or concomitant seems to be the most potential treatment in patients with advanced endometrial cancer [91-93]. 8. Conclusion Operation is the therapy of choice in the primary treat- ment of patients with endometrial cancer. With rising incidence of obesity number of patients with endometrial cancer will also increase. However, operations in obese patients are more challenging. Laparotomy as standard therapy in endometrial cancer patients stage I and II could be replaced by laparoscopic approaches. Laparo- scopy is oncologic adequate to open procedures and of- fers many advantages to patients–less blood loss, lower complication rate, shorter hospital stay and better quality of life, especially those with relevant co-morbidity. Ro- botic surgery in the treatment of endometrial cancer is still under evaluation. Most controversial points of treatment today are indication and extend of lym- phadenectomy in different stages. In advanced tumor stages, optimal debulking should be performed in order to improve effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapeutic and/or radiation therapy. REFERENCES [1] Krebs in Deutschland 2003-2004. “Häufigkeiten und Trends,” 6. überarbeitete Auflage. Robert-Koch-Institut (Hrsg.) und die Gesellschaft der epidemiologschen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. (Hrsg.). Berlin, 2008. [2] J. N. Bakkum-Gamez, J. Gonzales-Bosquet, N. N. Laack, A. Mariani and S. Dowdy, “Current Issues in the Man- agement of Endometrial Cancer,” Mayo Clinic Proceed- ings, Vol. 83, No.2, 2008, pp. 97-112. [3] A. W. Kennedy, J. M. Austin, K .Y. Look and C. B. Munger, “The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists Task Force Study of Endometrial Cancer Initial Experience,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 79, No.3, 2000, pp. 379-388. [4] Z. Vaknin, I. Ben-Ami, D. Schneider, M. Pansky and R. Halperin, “A Comparison of Perioperative Morbidity, Pe- rioperative Mortality, and Disease-specific Survival in Elderly Women (≧70 years) Versus Younger Women (<70 years) with Endometriod Endometrial Can- cer,”International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol. 19, No. 5, 2009, pp. 879-883. [5] S. Sato, H. Itamochi, M. Shima da, S. Fujii, J. Naniwa, K. Uegaki, S. Sato, M. Nonaka, T. Ogawa and J. Kigawa, “Preoperative and Intraoperative Assessment of Depth of Myometrial Invasion in Endometrial Cancer,” Interna- tional Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol.19, No. 5, 2009, pp. 884-887. [6] M. Signorelli, L. Guerra, A. Buda, M. Picchio, G. Mangili, T. Dell’Anna, S. Sironi and C. Messa, “Role of the Integrated FDG PET/CT in the Surgical Management of Patients with High Risk Clinical Early Stage Endo- Metrial Cancer: Detection of Pelvic Nodal Metastasis,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 115, No. 2, 2009, pp. 231- 235. [7] L. Chiva, F. Lapuente, L. Gonzales-Cortijo, N. Carballo, J.F. Garcia, A. Rojo and A. Gonzales-Martin, “Sparing Fertility in Young Patients With Endometrial Cancer,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 111, 2008, pp. 101-104. [8] M. Signorelli, G. Caspani, C. Bonazzi, V. Chiappa, P. Perego and C. Mangioni, “Fertility-sparing Treatment in Young Women with Endometrial Cancer or Atypical Complex Hyperplasia: A prospective Single-institution Experience of 21 Cases,” International Journal of Ob- stetrics & Gynaecology, Vol. 116, No. 1, 2009, pp. 114-118. [9] C. E. Richter, B. Qian, M. Martel, H. Yu, M. Azodi, T. J. Rutherford and P. E. Schwartz, “Ovarian Preservation and Staging in Reproductive-age Endometrial Cancer Pa- tients,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 114, No. 1, 2009, pp. 99-104. [10] O. Zivanovic, J. Carter, N. D. Kauff and R. R. Barakat, “A Review of the Challenges Faced in the Conservative Treatment of Young Women with Endometrial Carci- noma and Risk of Ovarian Cancer,” Gynecologic Oncol- ogy, Vol. 115, No. 3, 2009, pp. 504-509. [11] T. S. Lee, J. W. Kim, T. J. Kim, C. H. Cho, S. Y. Ryu, H. S. Ryu, B. G. Kim, K. H. Lee, Y. M. Kim, S. B. Kang and the Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group, “Ovarian Preservation during the Surgical Treatment of Early Stage Endometrial Adenocarcinoma: Unraveling a Mystery,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 115, No. 1, 2009, pp. 26-31. [12] Leitlinien zum Zervixkarzinom, zum Endometrium- karzinom und zu den Trophoblasttumoren, Kommission Uterus der AGO e.V. (Hrsg.), 1. Auflage 2008, Zuckschwerdt Verlag München-Wien-New York. [13] C. H. Han, K. H. Lee, H. N. Lee, C.J. Kim, T. C. Park and J. S. Park, “ Does the Type of Hysterectomy Affect the Prognosis in Clinical Stage I Endometrial Cancer?” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2010, pp. 581-587. [14] N. Furukawa, M. Takekuma, N. Takahashi and Y. Hirashima, “Intraoperative Evaluation of Myometrial In- vasion and Histological Type and Grade in Endometrial Cancer: Diagnostic Value of Frozen Section,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 281, No. 5, 2010, pp. 913-917. [15] G. Pristauz, A. A. Bader, P. Regitnig, J. Haas, R. Winter and K. Tamussino, “How Accurate is Frozen Section Histology of Pelvic Lymph Nodes in Patients with En-  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 188 dometrial Cancer? ”Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 115, No. 1, 2009, pp. 12-17. [16] A. Fagotti, G. Ferrandina, R. Longo, S. Mancuso and G. Scambia, “Minilaparotomy in Early Stage Endometrial Cancer: An Alternative to Standard and Laparoscopic Treatment,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 86, No. 2, 2002, pp. 177-183. [17] K. Foley and R. B. Lee, “Surgical Complications of Obese Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma,” Gyneco- logic Oncology, Vol. 39, No. 2, 1990, pp. 171-174. [18] J. C. Pavelka, I. Ben-Shachar, J. M. Fowler, N. C. Rami- rez, L. J. Copeland, L. A. Eaton, T. P. Manolitsas and D. E. Cohn, “Morbid Obesity and Endometrial Cancer: Sur- gical, Clinical and Pathologic Outcomes in Surgically Managed Patients,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 95, No. 3, 2004, pp 588-592. [19] R .J. Lelle, G. W. Morley and W. A. Peters, “The Role of Vaginal Hysterectomy in the Treatment of Endometrial Carcinoma,” International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol. 4, No. 5, 1994, pp. 342-347. [20] J. K. Chan, Y. G. Lin, B. J. Monk, K. Tewari, J. D. Bloss and M.L. Berman, “Vaginal Hysterectomy as Primary Treatment of Endometrial Cancer in Medically Compro- mised Women,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 97, No. 5, 2001, pp. 707-711. [21] G. Massi, T. Susini and G. Amunni, “Extraperitoneal Pelvic Lymphadenectomy to Complement Vaginal Op- erations for Cervical and Endometrial Cancer,” Interna- tional Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 69, No. 1, 2000, pp. 27-35. [22] S. C. Dowdy, G. Aletti, W. A. Cliby, K. C. Podratz and A. Mariani, “Extra-peritoneal Laparoscopic Para-aortic Lymphadenectomy — A Prospective Cohort Study of 293 Patients with Endometrial Cancer,” Obstetrics & Gyne- cology, Vol. 111, No. 3, 2008, pp. 418-424. [23] P. Capmas, A. S. Bats, C. Bensaid, C. Huchon, C. Scara- bin, C. Nos and F. Lecuru, “Surgical Treatment of Early Endometrial Cancer: What Are the Benefits of Laparo- scopy?” Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Repro- ductive Biology, Vol. 38, No. 7, 2009, pp. 537-544. [24] C. Köhler, P. Klemm, A. Schau, M. Possover, N. Krause, R. Tozzi and A. Schneider, “Introduction of Transperito- neal Lymphadenectomy in a Gynecologic Oncology Center: Analysis of 650 Laparoscopic Pelvic and/or Paraaortic Transperitoneal Lymphadenectomies,” Gyne- cologic Oncology, Vol. 95, No. 1, 2004, pp. 52-61. [25] D. Querleu, E. Leblanc, G. Cartron, F. Narducci, G. Ferron and P. Martel, “Audit of Preoperative and Early Complications of Laparoscopic Lymph Node Dissection in 1000 Gynecologic Cancer Patients,” Archives of Gyne- cology and Obstetrics, Vol. 195, No. 5, 2006, pp. 1287-1292. [26] A. Martinez, D. Querleu, E. Leblanc, F. Narducci and G. Ferron, “Low Incidence of Port-side Metastases after Laparoscopic Staging of Uterine Cancer,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 118, No. 2, 2010, pp. 145-150. [27] F. Ghezzi, A. Cromi, V. Bergamini, S. Uc ella, P. Beretta, M. Franchi and P. Bolis, “Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy versus Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy for the Management of Endometrial Cancer: A random- ized clinical trial,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Gyne- cology, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2006, pp. 114-120. [28] K. A. O’Hanlan, G. S. Huang, A. C. Garnier, S. L. Dibble, M.L. Reuland, L. Lopez and R. L. Pinto, “Total Laparo- scopic Hysterectomy versus Total Abdominal Hysterec- tomy: Cohort Review of Patients with Uterine Neopla- sia,” Journal of the Society of Laparoendscopic Surgeons, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2005, pp. 277-286. [29] A. Pellegrino, M. Signorelli, R. Fruscio, A. Villa, A. Buda, P. Beretta, A. Garbi and D. Vitobello, “Feasibility and Morbidity of Total Laparoscopic Radical Hysterec- tomy with or without Pelvic Lymphadenectomy in Obese Women with Stage I Endometrial Cancer,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetric, Vol. 279, No. 5, 2009, pp. 655-660. [30] C. K. Wong, Y. H. Wong, L. S. Lo, C. M. Tai and T. K. Ng, “Laparoscopy Compared with Laparotomy for the Surgical Staging of Endometrial Carcinoma,” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, Vol. 31, No. 4, 2005, pp. 286-290. [31] A. Zapico, P. Fuentes, A. Grassa, F. Arnanz, J. Otazua and J. Cortes-Prieto, “Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy versus Abdominal Hysterectomy in Stages I and II Endometrial Cancer. Oparating Data, Follow-up and Survival,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 98, No. 2, 2005, pp. 222-227. [32] E. Volpi, A. Ferrero, M. E. Jacomuzzi, A. P. Carus, L. Fuso, F. Martra and P. Sismondi, “Laparoscopic Treat- ment of Endometrial Cancer: Feasibility and Results,” European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Re- productive Biology, Vol. 124, No. 2, 2006, pp. 232-236. [33] D. Y. Kim, M. K. Kim, D. S. Suh, Y. M. Kim, Y. T. Kim, J. E. Mok and J. H. Nam, “Laparoscopic-Assisted Vagi- nal Hysterectomy versus Abdominal Hysterectomy in Pa- tients with Stage I and II Endometrial Cancer,” Interna- tional Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol. 15, No. 5, 2005, pp. 932-937. [34] L. Frigerio, A. Gallo, F. Ghezzi , G. Trezzi, M. Lussanna and M. Franchi, “Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Hyster- ectomy versus Abdominal Hysterectomy in Endometrial Cancer,” International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecol- ogy, Vol. 93, No. 3, 2006, pp. 209-213. [35] L. Tollund, B. Hansen and J. J. Kjer, “Laparoscopic- Assisted Vaginal vs. Abdominal Surgery in Patients with Endometrial Cancer Stage I,” Acta Obstetricia et Gyne- cologica Scandinavica, Vol. 85, No. 9, 2006, pp. 1138- 1141. [36] R. Seracchioli, S. Venturoli, M. Ceccarin, M. Cantarelli, M. Ceccaroni, E. Pignotti, D. De Aloysio and P. De Iaco, “Is Total Laparoscopic Surgery for Endometrial Carci- noma at Risk of Local Recurrence? A Long Term Sur- vival,” Anticancer Research, Vol. 25, No. 3c, 2005, pp. 2423-2428. [37] A. N. Fader, C. M. Michener, H. E. Frasure, N. Giannios, J.L. Belinson and K. M. Zanotti, “Total Laparoscopic  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 189 Hysterectomy versus Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy in Endometrial Cancer: Surgical and Sur- vival Outcomes,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Gyne- cology, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2009, pp. 333-339. [38] S. M. Eisenkop,“Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy with Pelvic/aortic Lymph Node Dissection for Endometrial Cancer – a Consecutive Series without Case Selection and Comparison to Laparotomy,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 117, No.2, 2010, pp. 216-223. [39] R. Tozzi, S. Malur, C. Köhler and A. Schneider, “Analy- sis of Morbidity in Patients with Endometrial Cancer: Is There a Commitment to Offer Laparoscopy,” Gyneco- logic Oncology, Vol. 97, 2005, pp. 4-9. [40] A. Obermair, T. P. Manolitsas, Y. Leung, I.G. Hammond and A. J. McCartney, “Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Versus Total Abdominal Hysterectomy for Obese Women with Endometrial Cancer,” International Journal of Gy- necological Cancer, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2005, pp. 319-324. [41] F. Zullo, S. Palomba, T. Russo, A. Falbo, M. Costantino, A. Tolino, E. Zupi, P. Tagliaferri and S. Venuta, “A Pro- spective Randomized Comparison between Laparoscopic and Laparotomic Approaches in Women with Early Stage Endometrial Cancer: A Focus on the Quality of Live,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 193, No. 4, 2005, pp. 1344-1352. [42] C. G. Zorlu, T. Simsek and E. S. Ari, “Laparoscopy or Laparotomy for the Management of Endometrial Cancer,” Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2005, pp. 442-446. [43] R. Tozzi, S. Malur, C. Koehler and A. Schneider, “Laparoscopy versus Laparotomy in Endometrial Cancer: First Analysis of Survival of a Randomized Prospective Study,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2005, pp. 130-136. [44] K. M. Fram, “Laparoscopically Assisted Vaginal Hyster- ectomy versus Abdominal Hysterectomy in Stage I En- dometrial Cancer,” International Journal of Gynecologi- cal Cancer, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2002, pp. 57-61. [45] M. Malzoni, R. Tinelli, F. Cosentino, C. Perone, M. Ra- sile, D. Iuzzolino, C. Malzoni and H. Reich, “Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy versus Abdominal Hysterec- tomy with Lymphadenectomy for Early-Stage Endo- metrial Cancer: A Prospective Randomized Study,” Gy- necologic Oncology, Vol. 112, No. 1, 2009, pp. 126-133. [46] F. Nezhat F, J. Yadav, J. Rahaman, H. Gretz and C. Cohen, “Analysis of Survival after Laparoscopic Man- agement of Endometrial Cancer,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2008, pp. 181-187. [47] S. Palomba, A. Falbo, R. Mocciaro, T. Russo and F. Zullo, “Laparoscopic Treatment for Endometrial Cancer: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs),” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 112, No. 2, 2009, pp. 415-421. [48] F. Lin, Q.J. Zhang, F.Y. Zheng, H. Q. Zhao, Q. Q. Zeng, M. H. Zheng and H.Y.Zhu, “Laparoscopically Assited versus Open Surgery for Endometrial Cancer — A Metaanalysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Interna- tional Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol. 18, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1315-1325. [49] C. B. Bijen, J. M. Briet, G. H. de Bock, H .J. Arts, J. A. Bergsma-Kadijk and M. J. Mourits, “Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy versus Abdominal Hysterectomy in the Treatment of Patients with Early Stage Endometrial Can- cer: A Randomized Multi Center Study,” British Medical Council, Cancer, Vol. 15, 2009, pp. 9-23. [50] J. Walker, R. Mannel, M. Piedmonte, J. Schlaerth, N. Spirtos and G. Spiegel, “Phase III Trial of Laparoscopy versus Laparotomy for Surgical Resection and Compre- hensive Surgical Staging of Uterine Cancer: A GOG Study Founded by the National Cancer Institute,” Gyne- cologic Oncology, Vol. 101, Sup. 2, 2006, p.177. [51] A. G. Visco and A. P. Advincula, “Robotic Gynecologic Surgery,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 112, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1369-1384. [52] J. F. Magrina, “Robotic Surgery in Gynecology,” Euro- pean Journal of Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2007, pp. 77-82. [53] A. P. Advincula and A. Song, “The Role of Robotic Sur- gery in Gynecology,” Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 19, No. 14, 2007, pp. 331-336. [54] C. Nezhat, N. S. Saberi, B. Shahmohamady and F. Nezhat, “Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy in Gynecological Sur- gery,” Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Sur- geons, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2006, pp. 317-320. [55] Nezhat F., “Minimally Invasive Surgery in Gynecologic Oncology: Laparoscopy versus Robotics.” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 111, Sup. 2, 2008 , pp. 29-32. [56] D. O. Holtz, G. Miroshnichenko, M. O. Finnegan, M. Chernick and C. J. Dunton, “Endometrial Cancer Surgery Costs: Robot versus Laparoscopy,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2010, pp. 500-503. [57] L. G. Seamon, J. M. Fowler, D. L. Richardson, M. J. Carlson, S. Valmadre, G. S. Phillips and D. E. Cohn, “A Detailed Analysis of the Learning Curve: Robotic Hys- terectomy and Pelvic-aortic Lymphadenectomy for En- dometrial cancer,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 8, May 2009, Epublication ahead of print. [58] R. Pareja and P. T. Ramirez, “Robotic Radical Hysterec- tomy in the Management of Gynecologic Malignancies,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Vol. 15, No. 6, 2008, pp. 673-676. [59] L. Mettler, T. Schollmeye r, J. Boggess, J. F. Magrina and A. Oleszczuk, “Robotic Assistance in Gynecological On- cology,” Current Opinion in Oncology, Vol. 20, No. 5, 2008, pp. 581-589. [60] M. Peiretti, V. Zanagnolo, L. Bocciolone, F. Landoni, N. Colombo, L. Minig, F. Sanguineti and A. Maggioni, “Ro- botic Surgery: Changing the Surgical Approach for En- dometrial Cancer in a Referral Cancer Center,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2009, pp.427-431. [61] L. G. Seamon, D. E. Cohn, M. S. Henretta, S. H. Kim, M. J. Carlson, G. S. Phillips and J. M. Fowler, “Minimally Invasive Comprehensive Surgical Staging for Endo-  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 190 metrial Cancer: Robotics or Laparoscopy?” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 113, No. 1, 2009, pp. 36-41. [62] M. C. Bell, J. Torgerson, U. Seshadri-Kreaden, A.W. Suttle and S. Hunt, “Comparison of Outcomes and Cost for En- dometrial Cancer Staging via Traditional Laparotomy, Standard Laparoscopy and Robotic Techniques,” Gyneco- logic Oncology, Vol. 111, No. 3, 2008, pp. 407- 411. [63] J. Cardenas-Goicoechea, S. Adams, S. B. Bhat and T. C. Randall, “Surgical Outcomes of Robotic-Assisted Surgi- cal Staging for Endometrial Cancer Are Equivalent to Traditional Laparoscopic Staging at Minimally Invasive Surgical Center,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 117, No. 2, 2010, pp. 224-228. [64] S. A. DeNardis, R. W. Holloway, G. E. Bigsby, D. P. Pikaart, S. Ahmad and N.J. Finkler, “Robotically Assisted Laparoscopic Hysterectomy versus Total Abdominal Hysterectomy and Lymphadenectomy for Endometrial Cancer,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 111, No. 3, 2008, pp. 412-417. [65] D. S.Veljovich, P. J. Paley, C. W. Drescher, E. N. Everett, C. Shah and W. A. Peters, “Robotic Surgery in Gyneco- logic Oncology: Program Initiation and Outcomes after the First Year with Comparison with Laparotomy for Endometrial Cancer Staging,” American Journal of Ob- stetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 198, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1-9. [66] J. F. Boggess, P. A. Gehrig, L. Cantrell, A. Shafer, M. Ridgway, E. N. Skinner and W. C. Fowler, “A Compara- tive Study of 3 Surgical Methods for Hysterectomy with Staging for Endometrial Cancer: Robotic Assistance, Laparoscopy, Laparotomy,” American Journal of Obstet- rics and Gynecology, Vol. 199, No. 4, 2008, pp. 1-9. [67] P. A.Gehrig, L. A. Cantrell, A. Shafer, L. N. Abaid, A. Mendivil and J. F. Boggess, “What Is the Optimal Mini- mally Invasive Surgical Procedure for Endometrial Can- cer Staging in the Obese and Morbidly Obese Woman?” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 111, No. 1, 2008, pp. 41-45. [68] G. L. Seamon, D. E. Cohn , D. L. Richardson, S. Val- madre, M. J. Carlson, G. S. Phillips and J. M. Fowler, “Robotic Hysterectomy and Pelvic-aortic Lymphadenec- tomy for Endometrial Cancer,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 112, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1207-1213. [69] J. B. Field, M. F. Benoit, T. A. Dinh and C. Diaz-Arrastia, “Computer-Enhanced Robotic Surgery in Gynecologic Oncology,” Surgical Endoscopy, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2007, pp. 244-246. [70] J. M. Cragun, L. J. Ha vrilesky, B. Calingaert, I. Synan, A. A. Secord, J. T. Soper, D. L. Clarke-Pearson and A. Ber- chuck, “Retrospective Analysis of Selective Lym- phadenectomy in Apparent Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 23, No. 16, 2005, pp. 3668-3675. [71] J. K. Chan, H. W. Wu, M. K. Cheung, J. Y. Shin, K. Osann and D. S. Kapp, “The Outcomes of 20.063 Women with Unstaged Endometroid Uterine Cancer,” Gyneco- logic Oncology, Vol. 106, No. 2, 2007, pp. 282-288. [72] D. C. Smith, O. K. Macdonald, C. M. Lee and D. K. Gaffney, “Survival Impact of Lymph Node Dissection in Endometrial Adenocarcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemi- ology and End Result Analysis,” International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2008, pp. 255-261. [73] A. Mariani, S. C. Dowdy, W. A. Cliby, B. S. Gostout, M.B. Jones, T. O. Wilson and K. C. Podratz, “Prospective Assessment of Lymphatic Dissemination in Endometrial Cancer: A Paradigm Shift in Surgical Staging,” Gyneco- logic Oncology, Vol. 109, No. 1, 2008, pp. 11-18. [74] W. T. Creasman, F. Odicino, P. Maisonneuve, M. A. Quinn, U. Beller, J. L. Benedet, A. P. M. Heintz, H. Y. S. Ngan and S. Pecorelli, “Carcinoma of the Corpus Uteri in 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gy- naecologic Cancer,” International Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics, Vol.95, Sup. 1, 2006, pp. S105-S143. [75] D. S. Chi, R. R. Barakat, M. J. Palayekar, D. A. Levine, Y. Sonoda, K. Alektiar, C. L. Brown and N. R. Abu-Rustum, “The Incidence of Pelvic Lymph Node Metastasis by FIGO Staging for Patients with Adequately Surgically Staged Endometrial Adenocarcinoma of En- dometroid Histology,” International Journal of Gyneco- logical Cancer, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2008, pp. 269-273. [76] P. Benedetti Panici, S. Basile, F. Maneschi, A. Lissoni, M. Signorelli, G. Scambia, R. Angioli, S. Tateo, G. Mangili, D. Katsaro, G. Garozzo, E. Campagnutta, N. Donadello, S. Greggi, M. Melpignano, F. Raspagliesi, N. Ragni, G. Cormio, R. Grassi, M. Franchi, D. Giannarelli, R. Fossati, V. Torri, M. Amoroso, C. Croce and C. Mangioni, “Sys- tematic Pelvic Lymphadenectomy vs. No Lymphadenec- tomy in Early-Stage Endometrial Carcinoma: Random- ized Clinical Trail,” Journal of the National Cancer In- stitute, Vol. 100, No. 23, 2008, pp. 1707-1716. [77] W. T. Creasman, C. P. Morrow, B. N. Bundy, H. D. Homesley, J.E. Graham and P.B. Heller, “Surgical Pathologic Spread Patterns of Endometrial Cancer. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study,” Cancer, Vol. 60, No. 8 (Suppl.), 1987, pp. 2035-2041. [78] ASTEC study group, H. Kitchener, A. M. Swart, Q. Qian, C. Amos and M. K. Parmar, “Efficacy of Syste matic Pel- vic Lymphadenectomy in Endometrial Cancer (MRC ASTEC Trail): A Randomised Study,” Lancet, Vol. 373, No. 9658, 2009, pp. 125-136. [79] R. C. Boronow, “Endometrial Cancer and Lymph Node Surgery: The Spins Continue — A Case for Reason,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 111, No. 1, 2008, pp. 3-6. [80] J. Aalders, V. Abeler, P. Kolstad and M. Onsrud, “Post- operative External Irradiation and Prognostic Parameter in Stage I Endometrial Carcinoma: Clinical and Histopa- thologic Study of 540 Patients,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 56, No. 4, 1980, pp. 419-427. [81] C. L. Creutzberg, W. L. Van Putten, P. C. Koper, M. L. Lybeert, J. J. Jobsen, C. C. Wárlám-Rodenhuis, K. A. De Winter, L. C. Lutgens, A. C. Van Den Bergh, E. Van De Steen-Banasik, H. Beerman and M. Van Lent, “Surgery and Postoperative Radiotherapy versus Surgery Alone for Patients with Stage-1 Endometrial Carcinoma: Multicen- tre Randomised Trial. PORTEC Study Group. Post Op- erative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Carcinoma,” Lancet, Vol. 355, No. 9213, 2000, pp. 1404-1411.  Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JCT 191 [82] H. M. Keys, J. A. Roberts, V. L. Brunetto, R. J. Zaino, N.M. Spirtos, J. D. Bloss, A. Pearlma n, M. A. Maiman, J. G. Bell and Gynecologic Oncology Group, “A Phase III Trial of Surgery with or without Adjunctive External Pel- vic Radiation Therapy in Intermediate Risk Endometrial Adenocarcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 92, No. 3, 2004, pp. 744-751. [83] ASTEC/EN.5 Study Group, P. Blake, A. M. Swart, J. Orton, H. Kitchener, T. Whelan, H. Lukka, E. Eisenhauer, M. Bacon, D. Tu, M.K. Parmar, C. Amos, C. Murray and W. Qian, “Adjuvant External Beam Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Endometrial Cancer (MRC ASTEC and NCIC CTG EN.5 Randomised Trials): Pooled Trial Re- sults, Systematic Review, and Meta-analysis,” Lancet, Vol. 373, No. 9658, 2009, pp. 137-146. [84] Y. Delpech and E. Barranger, “Management of Lymph Nodes in Endometrioid Uterine Cancer,” Current Opinion in Oncology, Vol. 22, No. 5, 2010, pp. 487-491. [85] E. Sartori, A. Gadducci, F. Landoni, A. Lissoni, T. Mag- gino, P. Zola and V. Zanagnolo, “Clinical Behavior of 203 Stage II Endometrial Cancer Cases: The Impact of Primary Surgical Approach and Adjuvant Radiation Therapy,” International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol.11, No. 6, 2001, pp. 430-437. [86] D. E.Cohn, E. M. Woeste, S. Cacchio, V. L. Zanagnolo, L. J. Havrilesky, A. Mariani, K. C. Podratz, W. K. Huh, J. M. Whitworth, D. S. McMeekin, M. A. Powell, E. Boyd, G. S. Phillips and J. M. Fowler, “Clinical and Pathologic Correlates in Surgical Stage II Endometrial Carcinoma,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 109, No. 5, 2007, pp. 1062-1067. [87] A. Ayhan, C. Taskiran, C. Celik and K. Yuce, “The Long-term Survival of Women with Surgical Stage II Endometrioid type Endometrial Cancer,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 93, No. 1, 2004, pp. 9-13. [88] A. Oleszczuk, C. Köhler, J. Paulick, A. Schneider and M. Lanowska, “Vaginal Robotic-Assisted Radical Hysterec- tomy (VRARH) after Laparoscopic Staging: Feasibility and Operative Results,” International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2009, pp. 38-44. [89] R. E. Bristow, M. J. Zerbe, N. B. Rosenshein, F. C. Grumbine and F. J. Montz, “Stage IVB Endometrial Can- cer: The Role of Cytoreductive Surgery and Determinants of Survival,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol. 78, No. 2, 200, pp. 85-91. [90] A. Ayhan, C. Taskiran, C. Celik, K. Yuce and T. Kucu- kali, “The Influence of Cytoreductive Surgery on Survival and Morbidity in Stage IVB Endometrial Cancer,” Inter- national Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Vol. 12, No. 5, 2002, pp 448-453. [91] K. Nakayama, Y. Nagai, M. Ishikawa, Y. Aoki and K. Miyazaki, “Concomitant Postoperative Radiation and Chemotherapy Following Surgery was Associated with Improved Overall Survival in Patients with FIGO Stages III and IV Endometrial Cancer,”International Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 24, 2010, Epublication ahead of print. [92] M. A.Geller, J. Ivy, K. E. Dusenberg, R. Ghebre, V. R. Isaksson and P. A. Argenta, “A Single Institution Ex- perience Using Sequential Multi-modality Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Radiation in the Sandwich Method for High Risk Endometrial Carcinoma,” Gynecologic On- cology, Vol. 118, No. 1, 2010, pp. 19-23. [93] A. Gadducci and C. Greco, “The Evolving Role of Adju- vant Therapy in Endometrial Cancer”, Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, Vol. 23, 2010, Epublication ahead of print. |