American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2013, 3, 435-443 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.34050 Published Online August 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajibm) 435 Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy Rong Wang Antai College of Economics & Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China. Email: rwang@sjtu.edu.cn Received June 23rd, 2013; revised July 20th, 2013; accepted July 27th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Rong Wang. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Taking advantage of online shopping affecting major parameters of corporate business including customer experience, customer word-of-mouth diffusion and customer complaints sharing, price elastic of consumer demand, and consumer brand loyalty, this paper focuses on the role of brand franchise supply chain partnership in the online and offline inte- grating environment. The findings suggest that the transfer payment shall be the critical contract clause to coordinate the brand franchise supply chain partnership to implement Pareto optimal strategy on VMI policy. Moreover, the opti- mal transfer payment has a strong positive relativity with the complementary of the online-offline shopping and VMI scale economic effect, whereas negative relativity with the substitutability of the online-offline shopping and VMI holding cost. The more VMI scale economic effect enhances, the larger online-offline integrating shopping market shares and the more system revenue shall be obtained in the brand franchise supply chain whereas taking advantage of the less transfer payment. The more VMI holding cost decreases, the larger online-offline integrating shopping market shares and the more system revenue shall be obtained in the brand franchise supply chain whereas taking advantage of the less transfer payment. Keywords: Brand Franchise Supply Chain; Transfer Payment Contract; Online-Offline Integrating Strategy; VMI Policy; Scale Economic Effect 1. Introduction Since the Internet-based e-commerce (electronic com- merce or Internet commerce) emerging with the creation of Amazon.com and Yahoo.com in 1995, the incredibly rapid evolution of the Internet from 1995 till the present time makes the worldwide internet users hit 2.749 bil- lion from 16 million of 1995 and the global Internet penetration rate rises to 38.8% from 0.4% of 1995 while the Internet penetration rate in the developed countries such as the United States, Japan, South Korea and Ger- many has reached over 78%, 79.5%, 82.5% and 83% for June 30 of 2012, respectively [1]. Alba et al. (1997) and some relevant literatures have been conducted exploring the consumer behaviors online which are different from traditional offline shopping en- vironment, and the differences ultimately impact brand image, customer loyalty, corporate profitability and the overall corporate value in turn [2-5]. According to the annual statistical reports released by China Internet Network Information Center, the present Internet penetration rate of 42.1% from 8.5% of 2005 in China has surpassed the global average level 38.8%, with along the utilization ratio of online shopping rising over 42.9% from 22.1% of 2007 in China [6]. The emergence and growth of a series of e-commerce services in China promote significantly the rapid growth of the consump- tion scale and have a huge impact on the future of China’s economy. By the end of December 2012, China has had a total of 564 million Internet users and more than 242 million online shoppers as exhibited in Table 1. The customers no matter whether they are online or offline are unshackled and empowered to find, rate, re- view and comment products and services easily facili- tated by social network websites, e-mails, discussion groups, blogs, tweets, mobile applications and so forth. The annual customer surveys reveal that today’s custom- ers regardless of online or offline shopping are increase- ingly sophisticated and less tolerant of poor customer experience, with 89 percent of consumers saying they will never go back to an organization after a bad cus- tomer experience, up from 68 percent in 2006. And 86 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy 436 Table 1. Growth of internet users and online shopping users in China from 2007 to 2012. Year Internet Users (Million) Internet Penetration Rate Online Shopping Users (Million) Utilization Ratio of Online Shopping 2005 111.00 8.5% - - 2006 137.00 10.5% - - 2007 210.00 16.0% 46.41 22.1% 2008 298.00 22.6% 74.00 24.8% 2009 384.00 28.9% 108.00 28.1% 2010 457.30 34.3% 160.51 35.1% 2011 513.10 38.3% 193.95 37.8% 2012 564.00 42.1% 242.02 42.9% Source: Adapted from The 17th-31st Statistical Report on Internet Develop- ment in China, CNNIC, January 2006-January 2013. percent of consumers will pay more for a better customer experience while 79 percent of consumers who shared complaints about poor customer experience online had their complaints ignored [7]. Today’s powerful brand is everything customers ex- periences about the product or service and the magical difference beyond their competing products and services. It can be seen that the new marketing era embedded in online and offline integrating strategy, long overdue, is heralded in. All online-offline business processes of the brand enterprise famous for this strategy such as sports retailer Nike and fast retailing UNIQLO, need to be inte- grated to deliver a consistent and holistic experience that stretches beyond the physical and rational experience. Rothery (2008) thinks of 4Es instead of 4Ps from the traditional offline marketing mix strategy comprised of product, price, place and promotion. In the new market- ing mix strategy of 4Es, where the product has evolved into the customer experience (integrating online and off- line), the place ranges over everyplace (including online and offline), the price becomes exchange, and the pro- motion has turned into evangelism. Alternatively, the promotion is morphing with product as communications seek to engage customers with experiences [8]. This new online and offline integrating environment allows brand enterprises to listen to customers everyplace while all the time engaging customers, developing brand image and nurturing customer loyalty along with inherently en- hancing brand power, ensuring preferred purchasing and encouraging repeat purchasing. As to the brand enterprises, the powerful brand is the strategic intellectual asset which is embedded in the ho- listic experience online and offline that stretches beyond the physical and rational experience into the psychology- cal and emotional experience about the brand product and service. The holistic experience including excellent product quality, on-time delivery and superior customer service, will be able to deliver and reflect the uncon- scious desires and aspirations from their customers. And then the truth is that their customers are simply exchang- ing some of their own aspirations and perceiving the magical difference beyond their competing products and services. The focus of this paper is the role of supply chain part- nerships in the online and offline integrating environment. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we will firstly overview the relevant literatures on comparisons of consumer behaviors in online-offline environment and supply chain partnership coordinated with contracts. The third section will explore the basic models and assumptions of brand franchise supply chain partnership based-on the online-offline in- tegrating strategy. Then, the fourth and fifth sections will analyze and present the key finds and managerial insights of the study on brand franchise supply chain coordination strategy on VMI Policy, followed by the concluding re- marks in the last section. 2. Relevant Literature 2.1. Comparisons of Consumer Behaviors in Online and Offline Environment Brynjolfsson and Smith (2000) find that the average prices for books and CDs were lower online in 1999, implying more price competition online than offline. However, they also find the price dispersion is lower in Internet channels than in conventional channels, reflect- ing the dominance of certain heavily branded retailers and branding, awareness, and trust remain important sources of heterogeneity among Internet retailers [9]. Shankar et al. (2001) study how the online medium af- fects the importance of price and the value of price search in the hospitality industry. Comparing online and offline shopper groups, they find that the online medium does not have a main effect on the importance of price, but it does increase the perceived value of price search and thus increases price sensitivity [10]. Degeratu et al. (2001) investigate how brand name, price, and other search attributes affect consumer choice behavior in online and conventional supermarkets. They find that the importance of brand name varies across category, price sensitivity is higher online because of the stronger sig- naling effect of online price cuts, and the combined ef- fect of price and promotion is lower online than offline environment [11]. Danaher et al. (2003) compare online and offline con- sumer brand loyalty and find that high market share brands, and therefore are better-known brands, enjoy a loyalty advantage in the online store, with the reverse result for small market share brands. In all these studies, the online and offline customers come from two separate Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy 437 samples; therefore, observed differences in shopping behavior might not be caused by the shopping media, but might be inherent in these two groups of consumers [12]. Chu et al. (2008) observe households that shop inter- changeably at the online and the offline stores in the same grocery chain and investigate their purchase be- havior in specific product categories. Although nearly 90% of households in the sample shop both at online and offline stores, they find that, across 12 vastly different product categories, these households exhibit lower price sensitivities when they shop online than when they shop offline [13]. Granados et al. (2012) analyze the impact of the Internet on demand, by comparing the demand func- tions in the Internet and traditional air travel channels. The results suggest that consumer demand in the Internet channel is more price elastic for both transparent and opaque online travel agencies [14]. Li et al. (2013) de- velop a theoretical model to analyze the pricing strategies of competing retailers with asymmetric cross-selling ca- pabilities when product demand changes and suggest that retailers with better opportunities for cross-selling have higher incentives to adopt loss-leader pricing on high- demand products than retailers with low cross-selling capabilities [15]. Taking advantage of online shopping affecting major parameters of corporate business including customer experience, customer word-of-mouth diffusion and cus- tomer complaints sharing, price elastic of consumer de- mand, and consumer brand loyalty, this paper focuses on the role of brand franchise supply chain partnership in the online and offline integrating environment. 2.2. Supply Chain Partnership Coordinated with Contracts The supply chain parties are primarily concerned with optimizing their own profitable objectives, and that self serving focus often results in poor performance, however, Pareto optimal performance is achievable if the supply chain parties coordinate by contracts so that each party’s objective becomes aligned with the supply chain’s objec- tive. In other words, no party has a profitable unilateral deviation from the supply chain contract because each party’s profit is no worse off and at least one member is strictly better off with the coordinating contract. The sup- ply chain contracting literatures have been widely re- searched and analyzed to coordinate the supply chain partnership [16,17]. Pasternack (1985), Donohue (2000), Taylor (2002) and Krishnan et al. (2004) have studied the return poli- cies and buyback agreements for perishable commodities such as consumer electronics, computers, software, books, magazines, newspapers, cosmetics, and so forth, which the manufacturer offers retailers a partial credit for all unsold goods with the agreed-upon price clause can achieve the supply chain coordination [18-21]. Bassok and Anupindi (1997), Moinzadeh and Nahmias (2000), Cachon and Lariviere (2001) have analyzed the quantity commitment contract for a single product that specifies that the cumulative orders by a buyer, over a finite horizon, be at least as large as the given total mini- mum quantity commitment [22-24]. Eppen and Iyer (1997), Cachon and Swinney (2008) have researched on the backup agreements in fashion supply chain [25,26], Tsay (1999), Milner and Kouvelis (2005) have studied quantity flexibility contracts in elec- tronics industry such as Sun Microsystems, IBM, con- tract manufacturers such as Solectron, and etc. [27,28]. Furthermore, Wang (2007) has analyzed systemically supply chain contract clauses on supplier flexibility and consequently put forward a supplier selection approach for downstream buyer based on supplier flexibility from the perspective of risk sharing in supply chain [29]. Barnes-Schuster (2002) have developed option con- tracts in the apparel industry, Cachon and Lariviere (2005) have demonstrated that revenue-sharing contracts to coordinate the supply chain partnership in the video- cassette rental industry, and Wang (2006) have given the analysis of revenue sharing contracts with uncertain de- mand in supply chain [30-32]. Wang and Benaroch (2004) discuss supply chain co- ordination to analyze the decision of suppliers and buyers to do or not do business in electronic markets while sell- ing perishable products with random demand and find that their decisions depend on the revenue structure of the power of electronic markets, and then Netessine and Rudi (2006) take the viewpoint of supply chain choice on the internet [33,34]. Wang (2010) extends the R&D part- nership contract coordination of information goods sup- ply chain in government subsidy and finds that the per- fect sharing contract may achieve greater effective coor- dination than non-linear transfer payment contract, along with the strengthening of the innovation basis and the extent to which partners absorb and transform techno- logical innovation knowledge, and the improvement of intellectual property protection environment and the de- gree of intellectual property protection [35]. Chen (2013) examines the dynamic supply chain co- ordination for deteriorating goods under consignment and vendor-managed inventory contracts with revenue sharing from retailer-centric business-to-business trans- actions in both traditional markets and electronic markets, and shows that, in a cooperative setting, the electronic markets with a consigned revenue-sharing VMI contract tends to achieve lower retail prices, larger stock quantity, improved channel efficiency, and increases in both re- tailer and supplier profits through an additional one-part tariff. Additionally, consumers benefit from lower retail prices and society benefits from increased overall chan- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy 438 nel profits in the cooperative channel and electronic markets [36]. On the basis of the fore research literatures, this paper proposes the brand franchise supply chain coordination model on VMI policy for modeling and analysis of the brand rand franchise supply chain partnership based on online-offline integrating strategy. 3. Basic Models and Assumptions Consider a brand franchise supply chain consists of two members: one brand enterprise and one upstream VMI partner-supplier with vendor managed inventory i.e. VMI policy. Firstly, the notations and assumptions in the models developed will be stated in details as follows. Based on the online-offline integrating strategy, brand franchise supply chain members listen to customers ev- eryplace while all the time engaging customers, devel- oping brand image and nurturing customer loyalty along with inherently enhancing brand power, ensuring pre- ferred purchasing and encouraging repeat purchasing. And then we may suppose the brand enterprise expected market demand with the price-sensitive consumers in the online and offline integrating environment is , , nnfn f nff n pd dadd pdda dd (1) where, pn and pf are the online shopping price and offline shopping price, dn and df are the online shopping quantity and offline shopping quantity, respectively. The shop- ping differentiation parameter, denoted by (−1 < < 1), represents the degree of substitutability of the online shopping and offline shopping as (0 < < 1) is positive, and the online shopping and offline shopping are perfect substitutes for consumers if = 1; whereas, represents the degree of complementary of the online shopping and offline shopping as (−1 < < 0) is negative, and the online shopping and offline shopping are perfect com- plements for consumers if = −1. For simplifying the analysis further, under the whole- sale contract, the linear transfer payments the down- stream brand enterprise purchasing the online shopping goods and offline shopping goods from the upstream VMI partner-supplier shall be expressed with the whole- sale price w as , nfn f Tddw dd (2) Similarly, as to the upstream VMI partner-supplier, for simplifying the analysis, the production costs with unit production cost c, and especially annual inventory hold- ing costs with scale economic effect α (0 < α 1, note that no scale economic effect if α = 1) for the online- offline shopping can be mathematically expressed as , nfn f Cddc dd (3) ,, 0; nfn f Hd dKddK 01 (4) where, the annual-inventory-holding-cost parameter K (K > 0) given in the above expression depends upon three main factors, including the annual cost-to-hold-inventory rate, the average product value, the relationship between the average inventory level and the annual demand throughput at the upstream VMI partner-supplier. Accordingly, we define that the brand enterprise’s and the upstream VMI partner-supplier’s expected revenue function in the online-offline integrating environment is as shown by express (5) and (6), respectively: ,, , , , rnfnnfnf nff nfnf n nf nf dd pdddpddd Td daddd adddwdd (5) ,,, , nfnf nfnf nf nf ddTdd CddHdd wcd dKd d (6) 4. Brand Franchise Supply Chain Coordination on VMI Policy without SEE Now, start with the case of brand franchise supply chain coordination on VMI policy without scale economic ef- fect (SEE) that is the parameter α = 1, and we analyze the optimal strategy of the brand enterprise in choice of the linear transfer payment contract clause. So we have the following: ,, .. 11, rnfn ww fnf nf MaxMax addd adddwdd stw c (7) From differentiation using the first order condition for dn and df, and then the optimal online shopping quantity and optimal offline shopping quantity may be obtained, respectively. 20 20 r nf f n r fn n f ad ddw d ad ddw d (8a) ** ,11, 1 21 nf aw dd (8b) Next, we move the optimal strategy of the upstream VMI partner-supplier focusing the wholesale contract Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy 439 clause, substituting the optimal shopping quantities dn * and df *, into Equation (6), , , 11 .. 11,,0,1 s w w aw aw MaxMaxw cK stwc K (9) Then, from the first-order and second-order conditions, the optimal linear transfer payment can be determined as 2 2 * 11 0; 20; 1 ,11,0, 1 2 s s aw aw wc K ww w acK wK (10) Correspondently, the optimal profiles of linear transfer payment contract coordination on VMI policy without scale economic effect in the online-offline integrating environment are solved as follows: ** ,11,0,1 41 nf acK dd K (11) 2 * 2 * ,11,0, 1 81 ,11,0,1 41 r s acK K acK K (12) Now, observe the above Expressions (11) and (12) that the optimal online-offline integrating strategy including online-offline shopping optimal quantities (i.e. d n * and df *), and the brand enterprise’s and the upstream VMI partner-supplier’s optimal expected revenues (i.e. πr * and πs *), are negative relevant with the degree of substitute- ability of the online shopping and offline shopping as (0 < < 1), whereas positive relevant with the degree of complementary of the online shopping and offline shop- ping as (−1 < < 0), shown as Figure 1. Thus, it is easy to see that [Proposition 1] The upstream VMI partner-supplier has more incentive to implement Pareto optimal strategy in choice of the linear transfer payment contract clause for brand franchise supply chain coordination on VMI policy without scale economic effect. 5. Brand Franchise Supply Chain Coordination on VMI Policy with SEE In this section, we focus on the analysis of brand fran- chise supply chain coordination on VMI policy with scale economic effect. In virtue of backwards induction, 1.0 0.50.5 1.0 4 6 8 10 d on* = d off* (a) 1.0 0.50.5 1.0 10 20 30 40 50 π s π r (b) Figure 1. The numerical results in the optimal online-offline integrating strategy as a = 10, c = 2, K = 1, α = 1. (a) Opti- mal online and offline integrating shopping quantities with ; (b) Brand franchise supply chain partners’ expected revenue with . firstly, find the brand enterprise’s optimal online-offline integrating strategy to maximize its own profit as a re- sponse to the wholesale contract clause, that is ,, .. 11, rnfn ww fnf nf MaxMax addd adddwdd stw c (13) As a result, the optimal online shopping quantity and optimal offline shopping quantity generated is expressed as following ** **,1 1, 21 nf aw dd w c (14) Secondly, find the optimal strategy of the upstream VMI partner-supplier focusing the wholesale contract clause, substituting the optimal shopping quantities dn * and df *, into Equation (6), Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy 440 ,, 11 .. 11,,0,01 s ww aw aw MaxMaxw cK stwc K (15) Differentiating this expression with respect to πs and w yields, 11 0 s aw aw wc K ww (16) Thus, 1 ** ** ** 2, 1 0, 01;11 aw Gwa cwK K (17) Ultimately, we have the following Stackelberg equi- librium policies in online-offline integrating environment are solved as following, ** ** **,0,0 1;1 21 nf aGw dd K 1 (18) 2 ** ** ** ** ** ** ,0,01;11 21 , 11 0,01;11 r s aGw K aGw aGw Gw cK K (19) 5.1. Numerical Analysis on Substitutability and Complementary of the Online-Offline Shopping and Managerial Insights In the meantime, letting a = 10, c = 2, K = 1 and α = 0.5 while is variable, for −1 < < 1, the respective nu- merical simulation results of Equations (10) and (12) comparing to Equations (17) and (19) are illustrated in Figure 2. As the Stackelberg leader, the upstream VMI part- ner-supplier shall make the effective contract clause “transfer payment w” for the brand enterprise to promote the optimal online-offline integrating strategy. In this way, the brand franchise supply chain coordination on VMI policy with scale economic effect shall gain the more system revenue than VMI policy without scale economic effect whereas taking advantage of the less transfer payment w. Hence, we can further summarize, [Proposition 2] The brand franchise supply chain part- ners have more incentive to implement Pareto optimal strategy in choice of the transfer payment contract clause for brand franchise supply chain coordination on VMI w w (a) П =π r +π s П * =π r* +π s* (b) Figure 2. The numerical results in substitutability and com- plementary of the online-offline shopping as a = 10, c = 2, K = 1, α = 0.5. (a) Brand franchise supply chain contract clause with ; (b) Brand franchise supply chain system ex- pected revenue with . policy with scale economic effect than the case of VMI policy without scale economic effect. Furthermore, the more incentive increases as the lower degree of substi- tutability of the online-offline shopping; whereas the more incentive increases as the higher the degree of com- plementary of the online-offline shopping. 5.2. Numerical Analysis on VMI Scale Economic Effect and Managerial Insights Simultaneously, letting a = 10, c = 2, K = 1 while α is given different levels and is variable, for −1 < < 1, the respective numerical simulation results from the Equation (17) to the Equation (19) are illustrated in Fig- ure 3. Therefore, the key managerial insight concluded from this analysis is as below. [Proposition 3] As the VMI scale economic effect en- hances (0 < α 1, especially note that no scale economic effect if α = 1), the brand franchise supply chain partners have more incentive to implement Pareto optimal Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy 441 0.6 0.4 0.20.2 0.4 6.10 6.15 6.20 6.25 6.30 α=0.75 α=0.25 (a) 0.6 0.4 0.20.2 0.4 0.6 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5 5.0 α=0.75 α=0. 25 (b) 0.6 0.4 0.20.2 0.40 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 α=0.75 α=0.25 (c) Figure 3. The numerical results in VMI scale economic ef- fect as a = 10, c = 2, K = 1, α = 0.25 vs. α = 0.75. (a) Brand franchise supply chain contract clause impacted by α; (b) The optimal online-offline integrating shopping quantities impacted by α; (c) Brand franchise supply chain system expected revenue impacted by α. strategy in choice of the wholesale contract clause “transfer payment w” for brand franchise supply chain coordination on VMI policy. Furthermore, the more VMI scale economic effect enhances (that means the lower level of α), the larger online-offline integrating shopping market share and the more system revenue shall be ob- tained in the brand franchise supply chain whereas taking advantage of the less transfer payment w. 5.3. Numerical Analysis on VMI Holding Cost and Managerial Insights Finally, letting a = 10, c = 2, α = 0.5 while K is given different levels and is variable, for −1 < < 1, the re- spective numerical simulation results from the Expres- sion (17) to Expression (19) are illustrated as Figure 4. In particular, the level of VMI holding cost parameter K depends upon the annual cost-to-hold-inventory rate, the average product value, the relationship between the av- erage inventory level and the annual demand throughput at the upstream VMI partner-supplier. As a result, the key managerial insight derived from this study can be seen in the following proposition. [Proposition 4] As the VMI holding cost decreases, the brand franchise supply chain partners have more incen- tive to implement Pareto optimal strategy in choice of the wholesale contract clause “transfer payment w” for brand franchise supply chain coordination on VMI policy. Fur- thermore, the more VMI holding cost decreases, the lar- ger online-offline integrating shopping market share and the more system revenue shall be obtained in the brand franchise supply chain whereas taking advantage of the less transfer payment w. 6. Concluding Remarks The purpose of this paper is to focus on the role of brand franchise supply chain partnership in the online and off- line integrating environment. The key managerial in- sights derived from this study are that the “transfer pay- ment w” shall be the critical contract clause to coordinate the brand franchise supply chain partnership to imple- ment Pareto optimal strategy on VMI policy. Moreover, the “transfer payment w” has a strong positive relativity with the complementary of the online-offline shopping and VMI scale economic effect, whereas negative rela- tivity with the substitutability of the online-offline shop- ping and VMI holding cost. The brand franchise supply chain partners have more incentive to implement Pareto optimal strategy in choice of the wholesale contract clause “transfer pay- ment w” for brand franchise supply chain coordina- tion on VMI policy, as the lower degree of substitute- ability of the online-offline shopping; whereas as the higher the degree of complementary of the online- offline shopping. The more VMI scale economic effect enhances, the larger online-offline integrating shopping market share and the more system revenue shall be obtained in the brand franchise supply chain whereas taking Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy 442 1.0 0.50.5 1.0 6.5 7.0 7.5 8.0 8.5 K=10 K=1 (a) 1.0 0.5 0.51.0 50 100 150 200 K=10 K=1 (b) 1.0 0.50.5 1.0 2 4 6 8 10 12 K=10 K=1 (c) Figure 4. The numerical results in VMI holding cost as a = 10, c = 2, α = 0.5, K = 1 vs. K = 10. (a) Brand franchise sup- ply chain contract clause impacted by K; (b) The optimal online-offline integrating shopping quantities impacted by K; (c) Brand franchise supply chain system expected reve- nue impacted by K. advantage of the less transfer payment. The more VMI holding cost decreases, the larger online-offline integrating shopping market share and the more system revenue shall be obtained in the brand franchise supply chain whereas taking advan- tage of the less transfer payment. REFERENCES [1] ITU, “History and Growth of the Internet from 1995 till Today,” International Telecommunications Unions, Ge- neva, 2013. [2] J. Alba, J. Lynch, B. Weitz, C. Janiszewski, R. Lutz, A. Sawyer and S. Wood, “Interactive Home Shopping: Consumer, Retailer, and Manufacturer Incentives to Par- ticipate in Electronic Marketplaces,” Journal of Market- ing, Vol. 61, No. 3, 1997, pp. 35-53. doi:10.2307/1251788 [3] E. Brynjolfsson and M. D. Smith, “Frictionless Com- merce? A Comparison of Internet and Conventional Re- tailers,” Management Science, Vol. 46, No. 4, 2000, pp. 563-585. doi:10.1287/mnsc.46.4.563.12061 [4] A. Chaudhuri and M. B. Holbrook, “The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 65, No. 4, 2001, pp. 81-93. doi:10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255 [5] A. M. Degeratu, A. Rangaswamy and J. Wu, “Consumer Choice Behavior in Online and Traditional Supermarkets: The effects of Brand Name, Price and Other Search At- tributes,” International Journal Research in Marketing, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2001, pp. 55-78. doi:10.1016/S0167-8116(00)00005-7 [6] CNNIC, “The 31st Statistical Report on Internet Devel- opment in China,” China Internet Network Information Center, Beijing, 2013. [7] M. L. Roberts and D. Zahay, “Internet Marketing,” Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc., Belmon, 2012. [8] Harris Interactive, “The Annual Customer Experience Impact Report,” RightNow, 2012, pp. 1-6. [9] C.-C. Chang and Y.-C. Chin, “Comparing Consumer Complaint Responses to Online and Offline Environ- ment,” Internet Research, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2011, pp. 124- 137. doi:10.1108/10662241111123720 [10] P. J. Danaher, I. W. Wilson and R. A. Davis, “A Com- parison of Online and Offline Consumer Brand Loyalty,” Marketing Science, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2003, pp. 461-476. doi:10.1287/mksc.22.4.461.24907 [11] P. K. Chintagunta, J. Chu and J. Cebollada, “Quantifying Transaction Costs in Online/Offline Grocery Channel Choice,” Marketing Science, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2012, pp. 96-114. doi:10.1287/mksc.1110.0678 [12] G. Rothery, “The Matchmaker,” Marketing Age, 2008. [13] J. Chu, P. Chintagunta and J. Cebollada, “A Comparison of Within-Household Price Sensitivity across Online and Offline Channels,” Marketing Science, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2008, pp. 283-299. doi:10.1287/mksc.1070.0288 [14] N. Granados, A. Gupta and R. J. Kauffman, “Online and Offline Demand and Price Elasticities: Evidence from the Air Travel Industry,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2012, pp. 164-181. doi:10.1287/isre.1100.0312 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Brand Franchise Supply Chain Partnership Based on Online and Offline Integrating Strategy Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM 443 [15] X. Li, B. Gu and H. Liu, “Price Dispersion and Loss- Leader Pricing: Evidence from the Online Book Indus- try,” Management Science, Vol. 59, No. 6, 2013, pp. 1290-1308. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1120.1642 [16] Gérard P. Cachon, “Supply Chain Coordination with Contracts,” In: S. Graves and T. de Kok, Eds., Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science: Supply Chain Management, Chapter 6, North-Holland, Amster- dam, 2003. [17] Y. Wang, “Overview of Supply Chain Contract Problem Driven by Customer Demand,” Journal of Management Sciences in China, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2005, pp. 68-76. [18] B. A. Pasternack, “Optimal Pricing and Return Policies for Perishable Commodities,” Marketing Science, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1985, pp. 166-176. doi:10.1287/mksc.4.2.166 [19] K. L. Donohue, “Efficient Supply Contracts for Fashion Goods with Forecast Updating and Two Production Modes,” Management Science, Vol. 46, No. 11, 2000, pp. 1397-1411. doi:10.1287/mnsc.46.11.1397.12088 [20] T. Taylor, “Supply Chain Coordination under Channel Rebates with Sales Effort Effects,” Management Science, Vol. 48, No. 8, 2002, pp. 992-1007. doi:10.1287/mnsc.48.8.992.168 [21] H. Krishnan and R. Kapuscinski and D. A. Butz, “Coor- dinating Contracts for Decentralized Supply Chains with Retailer Promotional Effort,” Management Science, Vol. 50, No. 1, 2004, pp. 48-63. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1030.0154 [22] Y. Bassok and R. Anupindi, “Analysis of Supply Con- tracts with Total Minimum Commitment,” IIE Transac- tions, Vol. 29, No. 5, 1997, pp. 373-381. doi:10.1080/07408179708966342 [23] K. Moinzadeh and S. Nahmias, “Adjustment Strategies for a Fixed Delivery Contract,” Operations Research, Vol. 48, No. 3, 2000, pp. 408-423. [24] Gérard P. Cachon and Martin A. Lariviere, “Contracting to Assure Supply: How to Share Demand Forecasts in a Supply Chain” Management Science, Vol. 47, No. 5, 2001, pp. 629-646. doi:10.1287/mnsc.47.5.629.10486 [25] G. D. Eppen and A. V. Iyer, “Backup Agreements in Fashion Buying: The Value of Upstream Flexibility,” Management Science, Vol. 43, No. 11, 1997, pp. 1469- 1484. [26] G. P. Cachon and R. Swinney, “The Impact of Strategic Consumer Behavior on the Value of Operational Flexibil- ity,” In: S. Netessine and C. Tang, Eds., Operations Man- agement Models with Consumer-Driven Demand, Chap- ter 14, Springer-Verlag, New York, 2009. [27] A. A. Tsay, “The Quantity Flexibility Contract and Sup- plier-Customer Incentives,” Vol. 45, No. 1, Manage- ment Science, 1999, pp. 1339-1358. doi:10.1287/mnsc.45.10.1339 [28] J. M. Milner and Panos Kouvelis, “Order Quantity and Timing Flexibility in Supply Chains: The Role of De- mand Characteristics,” Management Science, Vol. 51, No. 6, 2005, pp. 970-985. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1050.0359 [29] R. Wang, “Analysis of Supply Chain Contract Clauses on Supplier Flexibility,” Proceedings of 14th International Conference on Management Science & Engineering, ICMSE’07, 20-22 August 2007, Harbin, pp. 627-632. [30] D. Barnes-Schuster, Y. Bassok and R. Anupindi, “Coor- dination and Flexibility in Supply Contracts with Op- tions,” Manufacturing & Service Operations Manage- ment, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2002, pp. 171-207. doi:10.1287/msom.4.3.171.7754 [31] G. P. Cachon and M. A. Lariviere, “Supply Chain Coor- dination with Revenue-Sharing Contracts: Strengths and Limitations,” Marketing Science, Vol. 51, No. 1, 2005, pp. 30-45. [32] R. Wang, “Analysis of Revenue Sharing Contracts with Uncertain Demand in Supply Chain,” Proceedings of 13th International Conference on Management Science & Engineering, ICMSE’06, 5-7 October 2006, Lille, pp. 522-525. [33] C. X. Wang and M. Benaroch, “Supply Chain Coordina- tion in Buyer Centric B2B Electronic Markets,” Interna- tional Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 92, No. 4, 2004, pp. 113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2003.09.016 [34] S. Netessine and N. Rudi, “Supply Chain Choice on the Internet,” Management Science, Vol. 52, No. 6, 2006, pp. 844-864. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0512 [35] R. Wang, J. Ji and X. G. Ming, “R&D Partnership Con- tract Coordination of Information Goods Supply Chain in Government Subsidy,” International Journal of Com- puter Applications in Technology, Vol. 37, No. 3-4, 2010, pp. 297-306. doi:10.1504/IJCAT.2010.031945 [36] L. Chen, “Dynamic Supply Chain Coordination under Consignment and Vendor-Managed Inventory in Retailer- Centric B2B Electronic Markets,” Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 42, No. 4, 2013, pp. 518-531. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.03.004

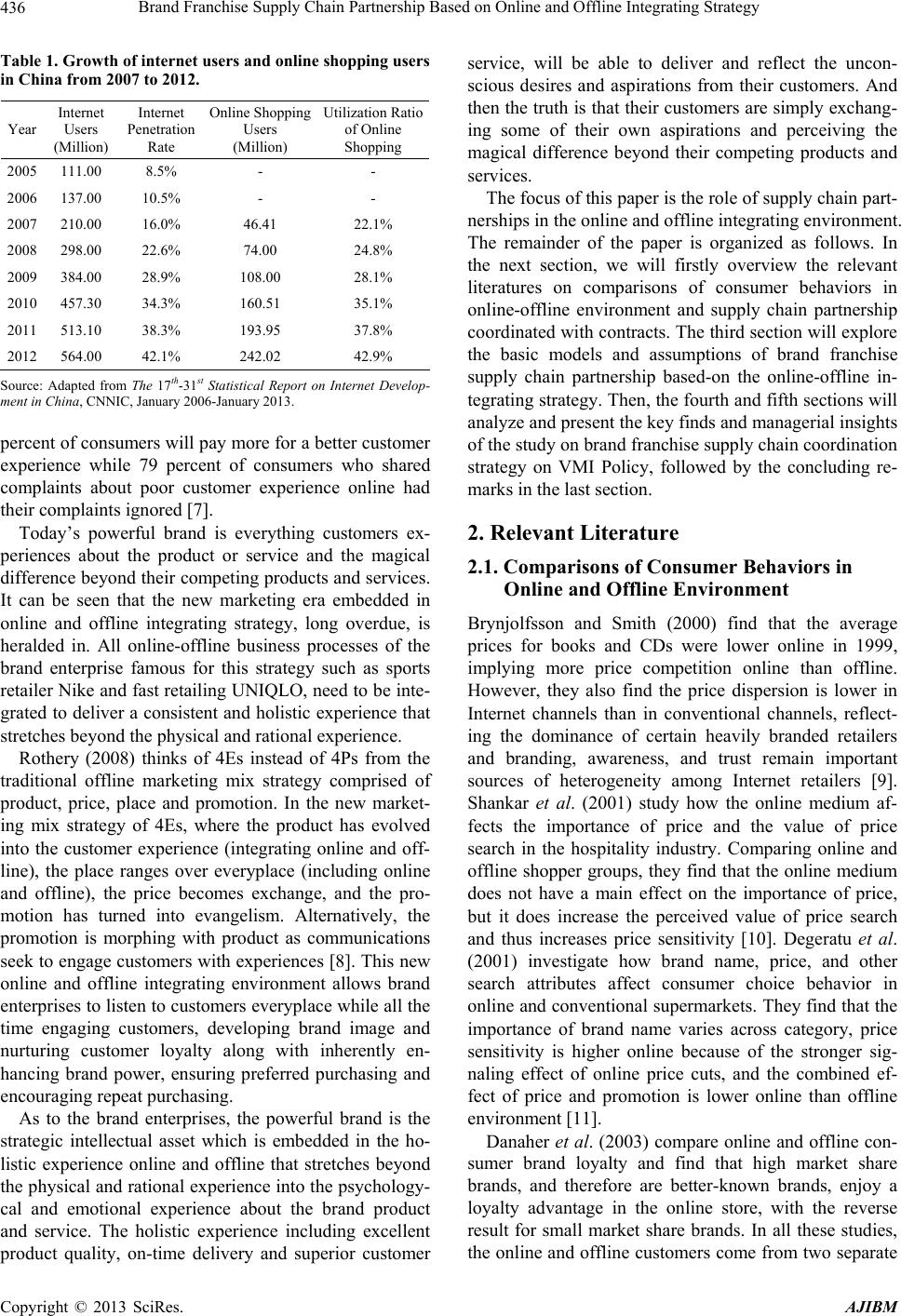

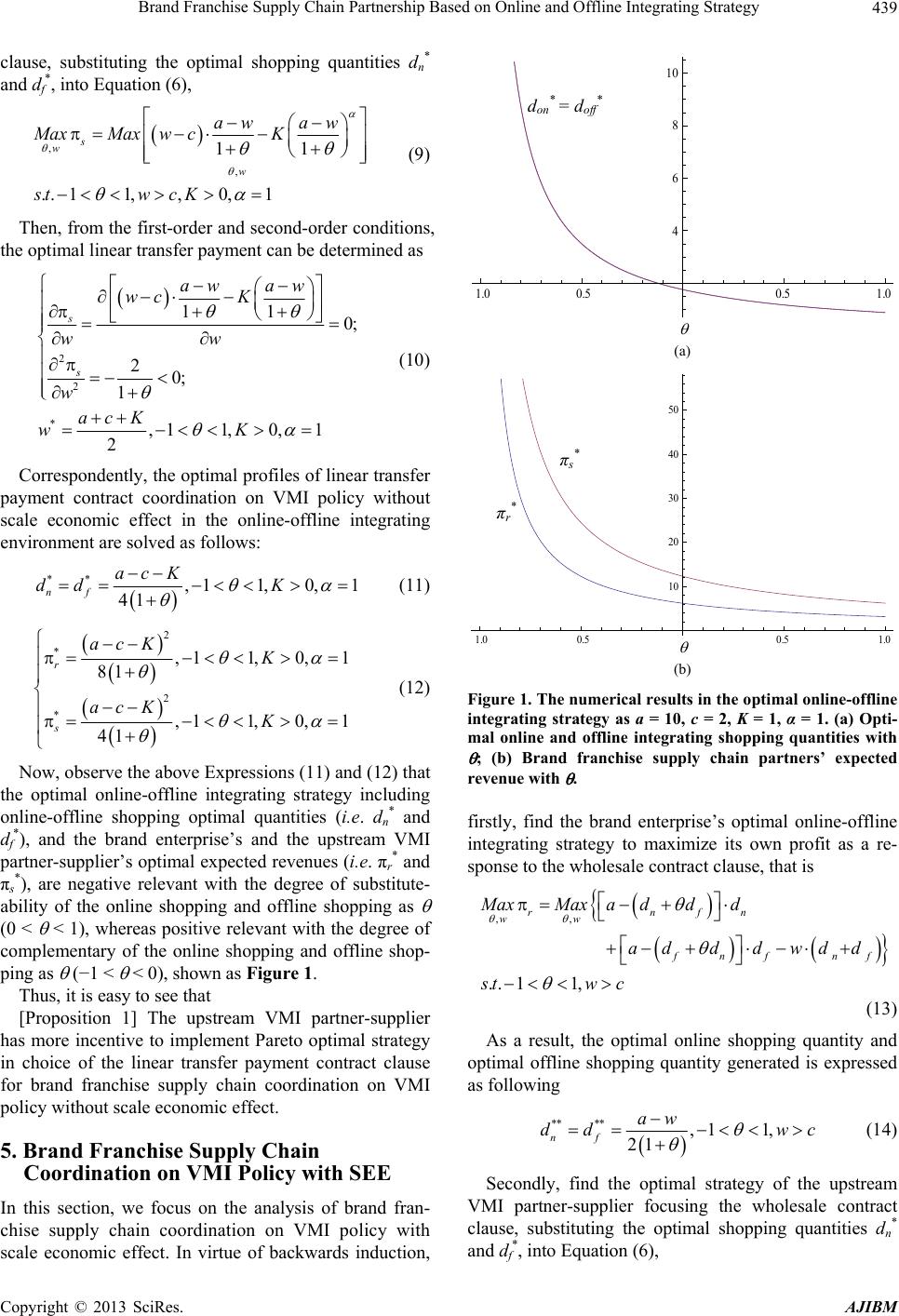

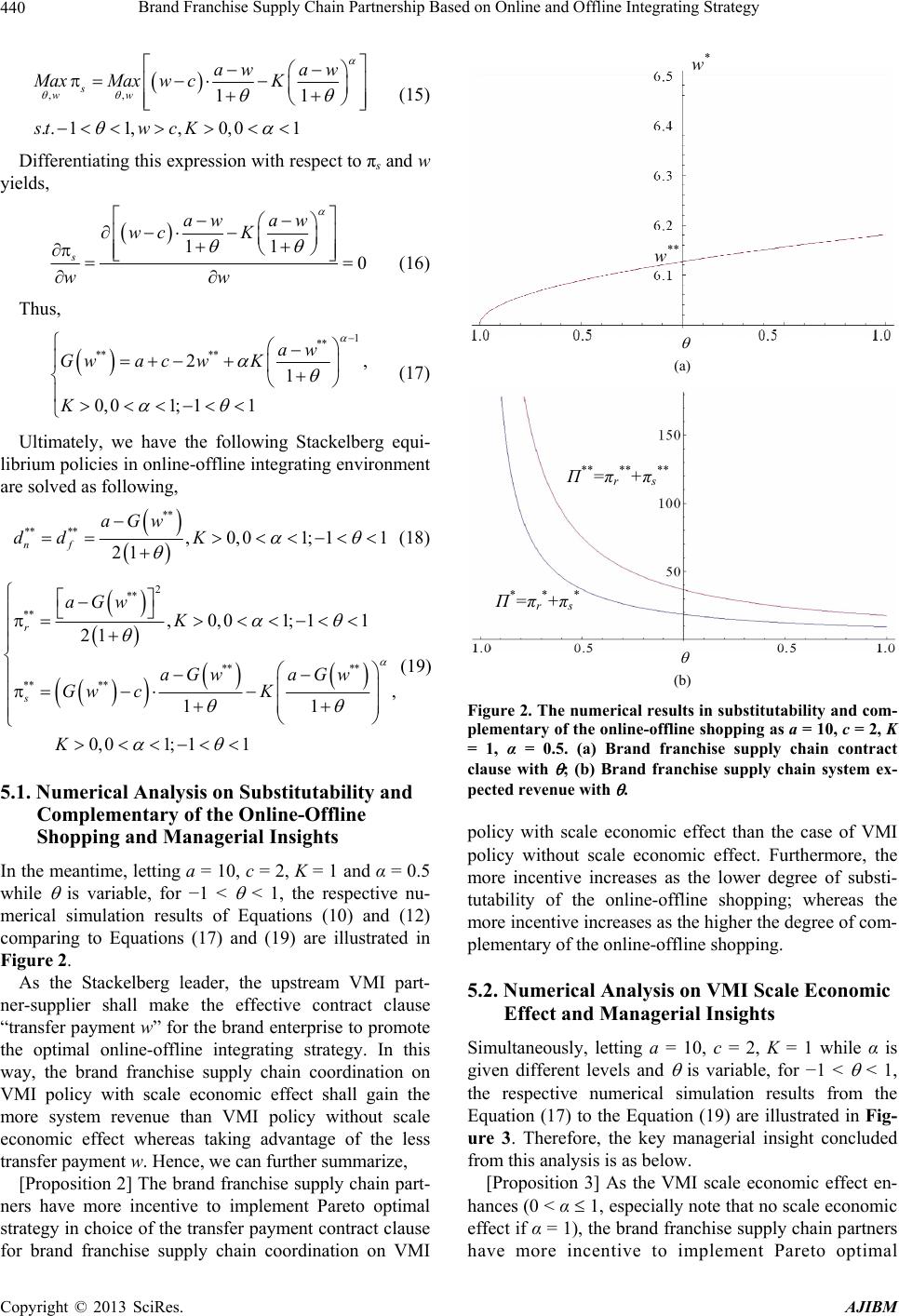

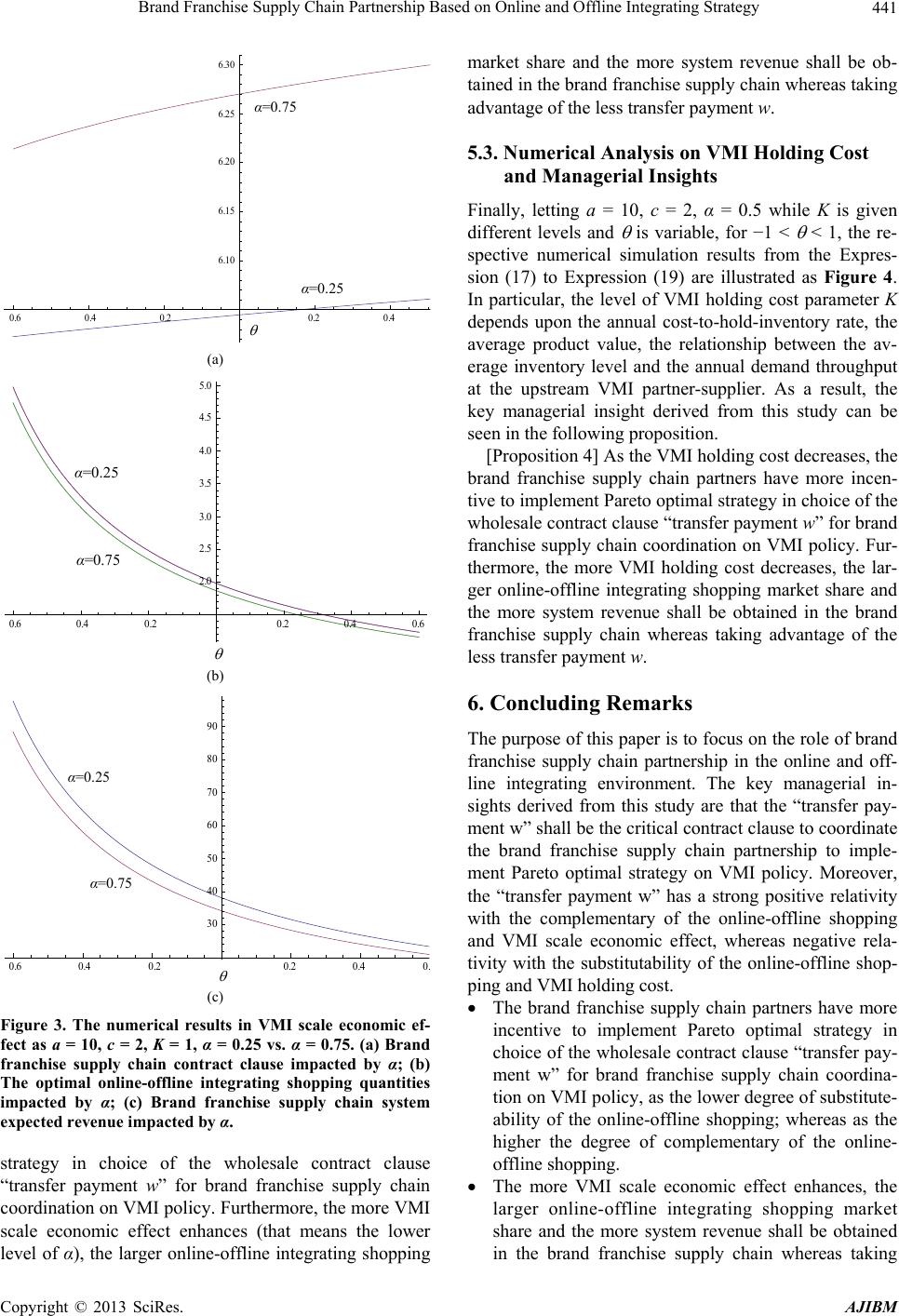

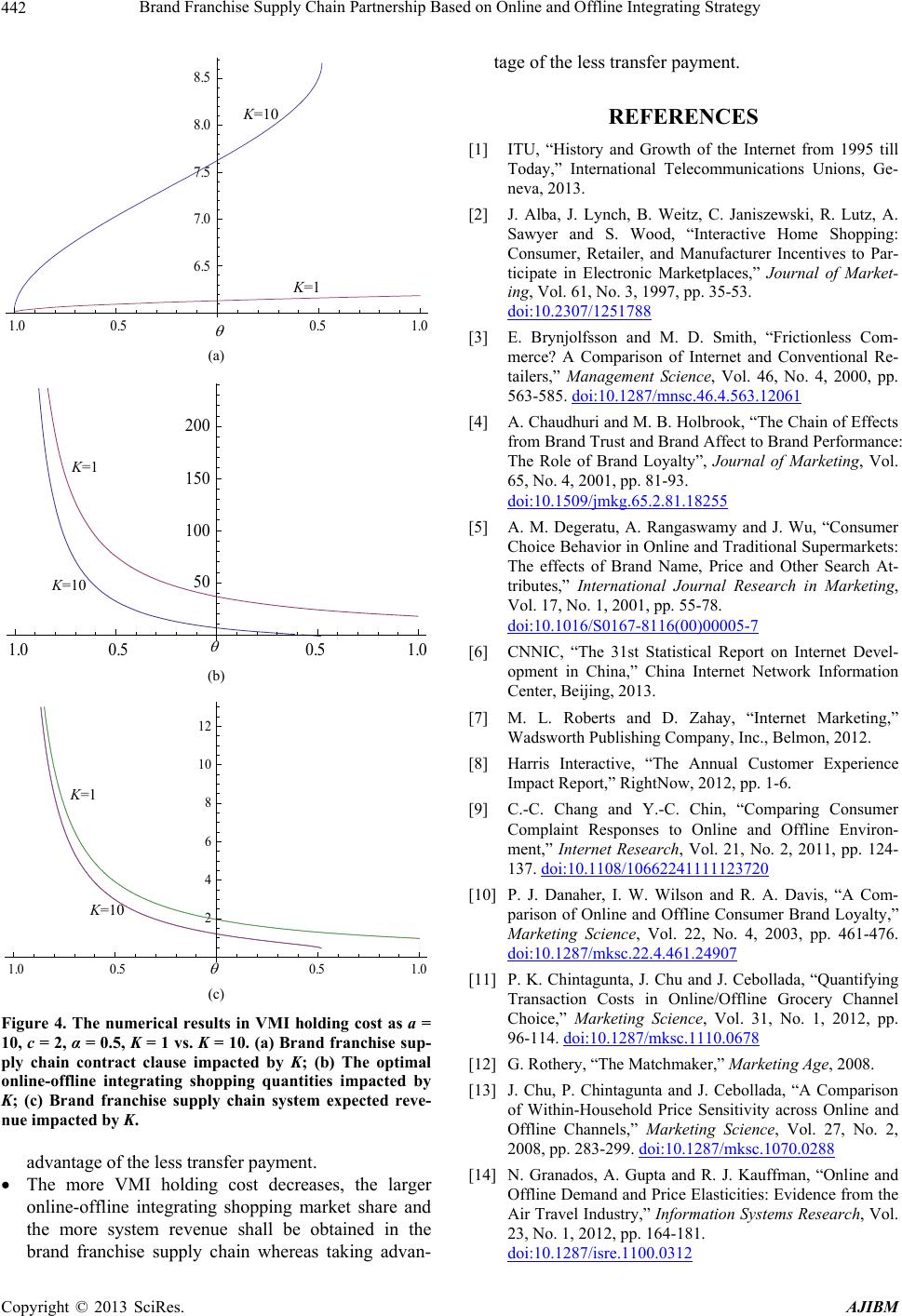

|