Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.8, 622-628 Published Online August 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.48089 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 622 Religious Practice and Attitudes towards Offenders Lucas Marcelo Rodriguez1,2, José Eduardo Moreno1,2 1“Teresa de Ávila” Faculty, Catholic University of Argentina, Paraná, Argentina 2Mathematical and Experimental Psychology Interdisciplinary Research Center, National Research Council, Buenos Aires, Argentina Email: lucasmarcelorodriguez@gmail.com, jemoreno1@yahoo.com Received May 18th, 2013; revised June 28th, 2013; accepted July 9th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Lucas Marcelo Rodriguez, José Eduardo Moreno. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This ex post facto study aims to investigate the influence of religious practice on the types of reaction to situations of offence. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to evaluate the relation- ship between religious practice and the attitudes towards offenders. The study was carried out with ado- lescents and young people of both sexes. The sample comprised 673 male and female, with an average age of 18.28 and standard desviation of 1.21. As regards the religion that they practiced: 555 were catho- lic (82.5%) 39 were evangelical (5.8%) and others 79 (11.7%). To assess the level of religious practice, a grid with items containing the frequency of religious practice was prepared, taking into account the per- son’s self perception. The second instrument used was the Attitudes Towards Offenders Questionnaire (ATOQ). This instrument consists of seven scales, grouped into three factors: passive, aggressive and prosocial behavior, corresponding to the different responses to situations of offence: submission, denial, vengeance, resentment, hostility, claim for an explanation and forgiveness. The result of MANOVA of the tree factors of ATOQ, according to religious practice (practitioner, occasional practitioner and not practitioner), stated a significant difference. When analyzing the contrasts we can see that practitioners are less aggressive with respect to occasional practitioners and non practitioners. As regards the prosocial factor, the only significant contrast is shown in practitioners, who have a higher average of prosocial atti- tudes compared to non-practitioners. Keywords: Religious Practice; Forgiveness; Adolescence; Prosocial Attitudes Introduction The study of values in adolescents and young people is ex- tremely important for the society in which we live and the cur- rent education, as well as reactions and attitudes in situations of violence and grievance experienced in interpersonal relation- ships and bonds. This is when the study of attitudes and reac- tions involving teenagers and young people with this kind of hostile and offensive situations is utterly important in order to identify the variables that influence the types of response; since late adolescence and, mostly youth, are stages of special sig- nificance for the development of moral and religious conscious- ness because people adopt definite moral and religious posi- tions and many reach the highest level of moral development (Kohlberg, 1975). The value system, in particular religious values, is of funda- mental importance in the type of reaction to hostile situations. According to Bock (2002) and Cjeka and Bamat (2003) the role of religion in situations of conflict, and specially what religious leaders and the congregation can do to promote peace and rec- onciliation, are areas about which we still do not know much, although some progress is being made to reach a better under- standing. Religion is generally a source of reconciliation and commit- ment in favor of peace and justice, and it also offers us pros- pects for forgiveness. Therefore, this work has the purpose of investigating which the influence of religious practice is on the types of reaction to situations of offence, so as to determine if religious practice fosters prosocial actions and if it diminishs other types of more undesirable reactions such as the aggressive one. Framework Religious Practice Religion comes from re-ligare, which refers to linking a con- gregation on a divinity, serving as a bond of union and commu- nity belonging; religion has a binding character, since the peo- ple are linked not only to a particular God or divinity, but end up linked horizontally between them (Carretero, 2010). Religion allows people to put themselves in the reality of the divine, recognizing its otherness to others, being the “Other” with respect to the human universe. That religiosity is an en- counter with the divine, also allowing an answer through prac- tice and everyday action (Vergote, 1969). Being religion an environment where to discover the mean- ing of life and where we acquire a worldview that is based on the relationship with the world, the people and the dimension of the sacred. It is an area where a personalized image of God who impregnates and saturates all reality is acquired. You can make a distinction between belief and religious practice, being religious belief part of the spiritual dimension of  L. M. RODRIGUEZ, J. E. MORENO the human being, which leads him to have faith in a specific religious system, unlike religious practice with consists of put- ting into practice activities prescribed by the religious system to which one belongs (Murphy et al., 2000), these practices in- clude going to mass, cult or service, personal prayer, etc. The conception that the person has of the transcendence varies from a personal God to something impersonal that may be associated with the idea of something superior, a strength, a destination, or the intentions of life itself (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000). Prosociality Antisocial attitudes are transmitted from generation to gen- eration. These attitudes far from promoting communication between people, distorts and even sometimes makes it impossi- ble. Many times we educate about acts of violence, of not accep- tance of the differences in others, lack of respect or tolerance of discrimination, in which the person who is “different” is ex- cluded, is rejected and not only from the material aspect, but radically from the symbolic one. The other side of the cited reality is represented by prosocial attitudes which are according the scientific community those attitudes that promote actions that end to benefit other people, groups and social organizations without an external reward (Moreno & Fernández, 2011). The term “prosocial” (prosocial behaviour) in the current meaning of the scientific work of psy- chological discipline, was coined by Wispé (1972) as an anto- nym of “anti-social” behavior. This term consolidated in later works such as those of Staub (1975), Mussen and Eisenberg- Berg (1977). The study of prosociality has made a great progress in recent years, taking into account has been given in the development of a healthy personality orientated to a positive interpersonal and social relationship. One of the objectives is to foster prosocial behaviours in such a way that individuals have some alternative healthy behaviour to live in a society in which every time there are more frequent, aggressive and competitive models. In this way, prosociality researchers believe that lays the foundations of a more harmonious society that favours the psychohygiene of individuals. For the positive consequences that prosociality experts on a social system as a powerful reducer of violence and aggression, as well as the effective construction of recip- rocity, is emerging from the contexts of social and develop- mental psychology reaching an important development. One of the premises of the Prosocial Applied Research Labo- ratory team, headed by Roche Olivar (1998, 1999), is that it is necessary a voluntary and active esteem towards the other for the prosocial behavior that leads to the eradication of violence and the improvement of human communication. A broader definition than the one commonly accepted by the scientific community, is that of the team of the Autonomous University of Barcelona which covers not only the simplicity of the one-way approach, as it is considered in early research, but also the complexity of human actions in its systemic and rela- tional aspect and, on the other hand, gathers more cultural di- mensions and susceptible of application in the social and po- litical field (Roche Olivar, 1998). It is defined in the following way: “That behavior that, without the search for external, ex- trinsic or material rewards, favour other people or groups, ac- cording to their criteria or social and objectively positive goals and increase the likelihood of generation a positive reciprocity of quality and supportive in consistent social or interpersonal relationships, safeguarding identity, creativity and initiative of individuals or groups involved” (Roche Olivar, 1998: p. 16). Generally speaking, in the research of prosocial behavior, the study of the behavior that tends to repair or reconstruction of the damaged bonds has not been included. Investigations have been focused on the elements involved in a good relationship and how to preserve it, but not on how to reconstruct it once it has been altered. Two basic types of positive responses to situa- tions of offence or discord are suggested; these are: the claim of explanation and the search of reconciliation (Moreno & Per- eyra, 2000). Responses to the Situation of Offence Frequently relationships are damaged, due to offence from one of the parts or even mutual offence, to the point breaking the relationship up. When having the experience of feeling our dignity hurt, the aggrieved part can respond with acts of vengeance or a perma- nent feeling of hostility, rancor and resentment. Or he can, without being aggressive, claim justice or repair or passively satisfy himself only by denying the existence of the offence or submitting to the offender. One of the most satisfactory ways to restrain aggressive behaviour or responses towards offence, according to the psychology of moral development, is to equip people with alternative types of positive and prosocial behav- iors that enable a more supportive and peaceful social coexis- tence. Given this, forgiveness becomes essential to recover the harmony of the bond, leaving both the victim and the offender free from the annoying situation and allowing reconciliation. Passive R e s ponses towards Offen de r s In a situation of offence the individual performs passive or inhibited behavior, characteristic of a conformist attitude or acceptance of the offence. Psychodynamic and cognitive sch- ools have described these individuals as people that instead of putting the interest in the offence and the offender, try to con- trol their aggressiveness to preserve internal stability. We focus on the intrapsychic processes that balance their own aggressive instincts in order to cope with and overcome the offensive be- havior, triggering a kind of hypercontrol that would make the individual reach a social overadaptation of a passive and con- formist social type. There are two types of passive response: Submission. It is “the conduct of subordination of the judgment, decision or the affections that belong to the of- fender, in general, by humiliating justifications, probably motivated in the suppression of the aggressive instinct or the disqualification of the aggressive act to safeguard the bond” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 21). By submissive atti- tudes the individual submitted passively accepts the conflict and tends to avoid it. With strong personalities, it abides all the rules coming from it without any criticism, finding a certain sense of security which he really lacks since he has little confidence in himself. The main factors of submission are usually: aggressive parental models, excessive feelings of guilt, extreme strictness and instilling a strong sense of duty (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000). The submissive person does not react, waiting others to do so and does not express any aggression at all. They generally have introverted, reserved, elusive, surly or timid personalities; different from adapted Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 623  L. M. RODRIGUEZ, J. E. MORENO people who maintain a flexible attitude in search of social approval, and who are affable, non-aggressive and permis- sive. The fact that submission does not hamper the rela- tionship with each other, it doesn’t mean that it is a proso- cial attitude, since it requires above all a free decision to do something for others, and the attitude of submission is not performed on freedom but, on the other hand, it is the sacri- fice of our own volition, just to obey. Submission, accord- ing to the psychodynamic perspective, would be “the be- havioral expression corresponding to the defense mecha- nism of repression” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 20). It strengthens their own control in relation to aggressive reac- tions, under the aid of the sense of reality. Denial. It is “the exclusion of the factual awareness and the concomitant feelings related to the offensive act” (Moreno, & Pereyra, 2000: p. 22). The individual that uses an attitude of denial does not recognize or accept reality, he rather re- jects it, although still being unquestionable; it relegates the disturbing object of the field of consciousness. From psy- chology, this attitude has been given the name of opposi- tional, referring to that individual who always says “no” to everything, without presenting his own position as regards a certain fact or situation. For psychoanalysts those people who use this type of defense are constantly alert in a silent, internal work that generates them energy loss and even de- pression (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Denial differs from submission in that the latter wants an internal control of the impulse, instead, denial attempts to exert control over ex- ternal stimuli in such a way that it can keep personal bal- ance. Aggressive Responses t owards Of fe nders The word aggression is defined by the Royal Spanish Acade- my (RAE, 2012) as the tendency to behave or respond violently. There are three attitudes or ways to respond to a situation of offence aggressively: Hostile Reaction. It is “the impulsive, immediate and reac- tive behavior.” “It refers to the fact of reacting immediately by attacking or damaging/injuring the aggressor” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 24). Hostílitas is the Latin word that gave rise to the term hostility; derived from hostilis adjec- tive that refers to everything that has to do with the enemy (hostis), hostility, harassment and war. Hostility or anger is defined as the emotional state consisting of feelings that vary in intensity, either from mild annoyance to anger or rage (Spielberger et al., 1985). Hostility differs from ag- gression in the fact that the latter implies a destructive be- havior, either towards objects or people, however the first one, only refers to feelings and attitudes that can provoke an aggressive response. Spielberger makes a difference between manifested cholera/anger and contained cholera. Manifested anger is expressed through physical and/or verbal actions such as insults, threats, or criticism; whereas contained cho- lera is when all forms of anger, which is considered as an expression of resentment, are omitted (Spielberger et al., 1985). Hostility has three components: the cognitive component that refers to negative beliefs that the individual has towards others, attributing them immoral or threatening or unreliable features; the affective component comprises everything re- lated to cognitive emotions in different levels; and the be- havioral component that includes different verbal and/or physical forms of aggression (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000). Resentment. It is the fact of saving internally feelings of anger and hatred that predispose enmity or cruelty with the offender. Resentment is defined as the entrenched and bitter memory of a particular insult, from which one wants to get satisfaction. Its synonym is bitterness, which comes from the Latin term rancor (complaint, grievance, claim) (Kan- cyper, 2006). The resentful person is the one that when of- fended feels so hurt that he does not want to or cannot for- get the offence. Deep inside he feels an aggressive desire which he fails to carry out and therefore acts as a thorn stuck in his interior. It is said that resentment is born of ha- tred inhibited in its purpose, which binds the person with the hated object or individual leaving him locked in the past. Max Scheler described resentment as mental poisoning/ psychic intoxication, as extremely contagious poison, or a state of poisoning and internal toxicity (Scheler, 1998). The resentful person shows himself particularly offended to- wards everything that can hurt him in his worth or honour, and requires immediate compensation for the damages suf- fered. Vengeance. “It is a premeditated behavior of intentional search of vengeance by means of a similar or superior pun- ishment to the one suffered” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 25). Erich Fromm relates revenge to reactive and vengeful violence. Reactive violence aims to eliminate the damage that threatens which is a survival behavior; instead vengeful violence tends to magically undo the damage already done, it is completely irrational, typical of people who have felt their self-esteem hurt and want to recover it by doing ex- actly the same, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” (Fromm, 1973). Neurotic people, according to Erich Fromm, have a greater desire for revenge than mature people. There are very pathological cases, indeed, in which revenge is part of the end of the person’s life which is something very se- rious since when the person does not take revenge the esti- mation of himself and especially the sense of self and the identity get threatened (Fromm, 1973). Prosocial Responses to Situati ons of Offence Explanation Request. It is “the attitude of asking the of- fender for justifications and reasons that explain his pro- ceeding, demanding to recover or repair, completely or partly, the harm done, as a necessary condition to repair the bond” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 27). In Psychology, this attitude is given the name assertive social behavior, because it does not focus on emotion but on the problem itself, on the bond. It is considered a social competition ability, since through this assertive behavior both positive rights and feelings as well as negative or hostile ones can be expressed in a socially acceptable way. It privileges interrelational values rather than emotional impulses achieving through this ability that the individual can make use of his emo- tional freedom, expressing intelligence, responsibility, ef- fort and sincerity. One of the definitions of assertiveness is the one provided by Alberti who refers to it as the set of behaviors, issued by a person in an interpersonal context, which expresses the person’s feelings, attitudes, desires, opinions or rights, in a direct, firm and severe way, and also respects the other people’s feelings, attitudes, desires, opin- ions and rights (Alberti, 1977). Although the request for Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 624  L. M. RODRIGUEZ, J. E. MORENO explanation works as a prosocial attitude that contributes to meeting each other and the clarification of the conflict situation, it cannot be compared to the attitude of forgive- ness since this happens while safeguarding the other and the bond with him over the offence itself and its explanations; instead, the fact of asking for explanation is urged by the desire to repair the damage received or the offence, and it is based on the intention to seek justice, and the rights and honour involved. The fact of preserving the bond moves to a second level, being subject to the satisfaction that the of- fender’s answer can provide” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000). Forgiveness. It is “the attitude of taking care of the bond of affection or love towards each other genuinely motorizing prosocial behaviors aimed at overcoming discord and also fostering dialogue.” “When the relationship is broken, for- giveness keeps the possibility of reconciliation open, shut- ting down the doors to vengeance and favoring the restora- tion of the damaged bond” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 28). The word forgiveness comes from the Latin words per (a preposition that reinforces the meaning of the word to which it is attached) and donare (verb which means “to give”). Therefore, to forgive is a maximum expression of giving, of love, of charity. However, the word reconcilia- tion comes from the Latin reconciliatio—the action that means to restore broken relationships—that translates the Greek word katallage, meaning to change completely (Nel- son, 1978). It refers to the fact of making up the damaged relationship, leaving out disagreement and retrieving under- standing and harmony. When facing the other’s offensive attitude, forgiveness aims to suspend or cancel all punish- ment deserved waiting for the offender’s repentance and change of conduct. This purpose relies on the love and dig- nity that “everyone” deserves for the mere fact of being a person, regardless of the intensity level of the offence; it means to recognize his intrinsic value as a person. This love, which is considered as a life principle, radically eliminates all hatred, enmity or revenge. It is love in its highest ex- pression, therefore it is about loving our own enemies, whom we have insulted, dishonored, or denigrated (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000). The forgiveness is a time consuming process as evidenced by numerous studies (Worthington et al., 2000). Robert Enright (2004) defined the interpersonal forgiveness: “Forgiveness is a willingness to abandon one’s right to resentment, negative judgment, and indifferent be- havior toward one who unjustly injured us, while fostering the undeserved qualities of compassion, generosity and even love toward him or her” (Enright & Rique, 2004: p. 1). The objective of this study aims to investigate the influence of religious practice on the types of reactions to situations of offence. The authors considered forgiveness and explanation request as prosocial attitudes, and vengeance, resentment and hostility as antisocial attitudes. The hypothesis is that the higher level of Christian religious practice the higher prosocial atti- tudes and the lower aggressive attitudes. Methodology This is a descriptive-correlational study which includes an ex post facto design, as the independent variable has already acted on the subjects and, therefore, it is not manipulated. The MANOVA is used to see how religious practice (independent variable) affects attitudes towards offenders (dependent vari- ables). Subjects The study was carried out in the city of Paraná, Entre Ríos, and in the city of Buenos Aires with teenagers and young peo- ple of both sexes. The non-probabilistic sample, comprised 673 adolescents and young people, 179 males (26.6%) and 494 females (73.4%) being 18.28 the average age of subjects with a deviation of 1.21. The high percentage of females in the sample is because both high school and college students were studying social and hu- man sciences. At Technical High School and College we can observe in Argentina that there are more male students. Regarding the religion practice: 555 are catholic (82.5%) 39 are evangelical (5.8%) and other religion or non-religion 79 (11.7%). Instruments To assess the individuals’ degree of religious practice we de- signed a grid with items containing different levels of religious practice frequency, considering the individuals’ self-perception of their religious practice. The categories were: non-practitioner, occasional practitioner, practitioner and usual practitioner. The second instrument used was the complete Attitudes To- wards Offenders Questionnaire (ATOQ). This tool, created by Moreno and Pereyra (2000) consists of seven scales, corre- sponding to different responses to situations of offence: sub- mission, denial, vengeance or retaliation, rancor and resentment, hostility, explanation or claim and forgiveness and reconcilia- tion. These scales are analyzed in different relational fields such as: workplace, friendship, parents, couple and God and the creative order. The questionnaire consists of ten short situations of injustice or violence which the person has to respond as if he were the person aggrieved. Each story has seven possible responses to the situation which the person must answer as to whether he would never, seldom, often or always do it. Below we briefly describe the key concepts of the question- naire of attitudes towards offenders: 1) Passive responses: “Passive or inhibited behaviors, com- patible with a conformist or offence acceptance attitude” (Mo- reno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 19). a) Submission “Emotional control prevails, thus leaving the individual inhibited without the necessary strength for an active response” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 19). b) Denial: “Perceptive control prevails, distorting the repre- sentation of reality, in a way that the individual ignores the disturbing situation” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 22). 2) Aggressive responses: c) Hostile reaction: “Impulsive, immediate and reactive be- havior. It is the willingness to react immediately attacking or damaging the aggressor” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 24). d) Resentment: “To keep feelings of anger and hatred in- wardly that predispose to enmity or malice towards the of- fender” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 24). e) Vengeance: “Premeditated behavior of intentional search for vengeance by means of a similar or higher punishment to the one suffered” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 25). 3) Prosocial behavior: f) Claim for an explanation: “Attitude to ask the offender for Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 625  L. M. RODRIGUEZ, J. E. MORENO justifications and reasons that account for his actions, demand- ing to recover or repair, in part or completely, the damage caused as a necessary condition to repair the bond” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 26). g) Forgiveness: “attitude of taking care of the bond of affec- tion or love towards each other genuinely motorizing prosocial behaviors aimed at overcoming discord and also fostering dia- logue. When the relationship is broken, forgiveness keeps the possibility of reconciliation open, shutting down the doors to vengeance and favoring the restoration of the damaged bond” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 28). Areas (relational spheres): 1) The workplace is a common source of grievance and con- flict in daily life, due to high exposure to contacts and interrex- changes in everyday activities and for other reasons that make labor or institutional variables involved (competition, power struggle, hierarchy, etc.) (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000). 2) The relation with friends is “of the utmost importance in the emotional sphere and the effect it has on personality devel- opment throughout the life cycle” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 29). 3) “The relationship with Parents, because of their influence on the early stages of life, on the formation of behavior patterns and due to the peculiar alliance that is built with the ones that have given us life” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 29). 4) “The couple, due to being the deepest bond, with intense interrelational values in which sexuality plays a decisive role” (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 30). 5) “The relationship with God and the created order (G) en- vironment, which takes into account the damage received by heredity or external phenomena not attributable to human be- ings, often awarded to God, the world, fate or life as a su- prapersonal order “(Moreno & Pereyra, 2000: p. 30). Offense always happens within specific situation. It is only understood in that peculiar context, which gives it meaning. Considering that reactions toward offense may vary according to the closeness of the relationship, we distinguish the above five different relational spheres (areas): the work place, friend- ship, parent/child relationship, the couple, and God. Validation studies provided satisfactory results. Internal con- sistency analysis (reliability) of the seven scales were calcu- lated with Cronbach alpha ranging from .70 to .81. This result should be considered acceptable due to the fact that every scale has five different relational spheres (Moreno & Pereyra, 2000). Factor analysis reported three factors (Passive, Aggressive and Prosocial Attitudes), which explain a relatively high proportion of the variance (55%). To establish convergent validation sev- eral scales were correlated with ATOQ Scales. The Social Re- sponsibility Scale of the Emotional Quotient Inventory (Bar-On, 1994), which correlated positively with Request for Explana- tion (r = .45, p < .000) and Forgiveness (r = .43, p < .000). The NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1995) Neuroticism Scale corre- lated with Resentment (r = .37, p < .000), Vengeance (r = .27, p < .01) and Forgiveness (r = −.29, p < .01), and Kindness Scale, which correlated negatively with Vengeance (r = −.48, p < .000), Resentment (r = −.37, p < .000), and Hostility (r = −.24, p < .000). On the Hope-Hopelessness Scale (Pereyra, 1995, 1996), Hopelessness correlated positively with Resentment (r = .43, p < .000), Vengeance (r = .28, p < .01), and Hostility (r = .25, p < .01), and Hope correlated positively with Forgive- ness (r = .18, p < .05). The SCL-90 (Derogatis, 1977) correlated positively with Vengeance (r = .28, p < .01), Resentment (r = .32, p < .000) and negatively with Forgiveness (r = −.27, p < .01). In summary, factorial analysis and convergent validation studies provided results consistent with the theory. Besides, the power of discrimination of each item is good. Thus, ATOQ presents adequate psychometric properties for assessing atti- tudes towards offence. Procedure The self administrable questionnaires were answered in groups. In the case of university students, there were between 8 and 10 people in each group. For high school students, they were administered to larger groups between 20 and 40 students. The sample was divided into two groups, consisting of 386 college students and 287 secondary students. At the same time, the entire sample was divided into three subgroups taking into account the level of religious practice, namely: non-practitio- ners, occasional practitioners and practitioners. The category of practitioners both groups the ones who chose the practitioner and the high practitioner categories. To assess differences in attitudes toward offenders between both groups, we decided to conduct a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), using the program SPSS. Results The result of the multivariate analysis of variance (MA- NOVA) of the three factors of the Attitudes Towards Offenders Questionnaire (ATOQ) namely: aggression, passivity, proso- ciality, according to religious practice (practitioner, occasional practitioner and non-practitioner), shows a significant overall difference (F Hotelling (6, 1334) = 9.91, p = 0.0001). Analyz- ing the univariate F, we note that the differences in aggressive attitudes towards offenders are significant (F = 22.44 p = 0.0001) in relation to religious practice, as well as prosocial attitudes (F = 8.203 p = .0001) (see Table 1). Analyzing the contrasts among the three subsamples we found that as for the aggressive factor it is significant that: practitioners are less aggressive than occasional practitioners (p = 0.0001) and also non-practitioners (p = 0.0001). Regarding the prosocial factor, the only significant contrast is the one of practitioners, who have a higher average of prosocial attitudes in relation to non-practitioners (p = 0.0001). As expected, no significant contrasts are observed in the passive factor. The above mentioned shows aggressive and prosocial factor significant differences between practitioners and non practitio- ners and occasional practitioners. The result of the multivariate analysis of variance (MA- NOVA) taking into account each attitude towards offenders, namely: submission, denial, vengeance, resentment, hostility, understanding and forgiveness, according to religious practice shows significant overall difference (F Hotelling (14, 1326) = 5.58, p = 0.0001). Analyzing the univariate F of each attitude, we note that the differences are significant in the attitudes of vengeance, resentment and hostility towards offenders (in the three cases p = 0.0001) in relation to religious practice, as well as in forgiveness attitudes (p = 0.0001) and to a lesser extent in explanation request (p = .016). Analyzing the contrasts among the three subsamples, consid- ering the seven analyzed attitudes towards offenders, the fol- lowing conclusions are significant: practitioners are less venge- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 626  L. M. RODRIGUEZ, J. E. MORENO Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 627 Table 1. Multivariate analysis of variance. Mean differences and deviations in ATOQ factors according to religious practice. Non-practitioners Ocassional practitioners Practitioners ATOQ factors M DS M DS M DS F p Passive 22.42 3.52 23.07 3.48 22.92 3.34 1.67 .18 Aggressive 21.06 4.40 21.02 4.02 18.88 4.03 22.44 .0001 Prosocial 30.30 4.47 31.16 3.86 31.87 3.35 8.20 .0001 Sample n = 139 n = 250 n = 284 n total = 673 Table 2. Multivariate analysis of variance. Mean differences and deviations in ATOQ scales according to religious practice. Non-practitioners Ocassional practitioners Practitioners ATOQ scales M DS M DS M DS F p Submission 23.42 4.21 24.20 3.77 24.18 3.94 2.11 .12 Denial 21.41 3.94 21.94 4.03 21.67 3.72 .87 .41 Vengeance 17.43 5.43 16.97 4.82 14.35 3.88 30.47 .0001 Resentment 22.30 4.95 22.67 4.85 20.57 4.85 13.64 .0001 Hostility 23.45 5.07 23.42 4.58 21.73 5.01 9.96 .0001 Explanation 30.40 4.76 31.55 4.30 31.56 3.85 4.14 .01 Forgiveness 30.20 4.99 30.77 4.35 32.18 3.94 12.21 .0001 Sample n = 139 n = 250 n = 284 n total = 673 ful than non practitioners and occasional practitioners (in both cases p = 0.0001), practitioners are less rancorous than non practitioners (p = .003) and occasional practitioners (p = 0.0001) as regards hostile attitudes practitioners are less hostile than occasional practitioners (p = 0.0001) and non-practitioners (p = 0.003) as for prosocial attitudes, non-practitioners ask for less explanation than occasional practitioners and practitioners (in both cases p = 0.03), with respect to forgiveness, practitioners have this attitude in a higher level than non-practitioners (p = 0.001) and occasional practitioners (p = 0.0001) (Table 2). The above results express the significant difference in practi- tioners’ attitudes of vengeance, resentment, hostility and for- giveness, compared to occasional practitioners and non practi- tioners. Discussion and Conclusion In the present research we have observed significant differ- ences in the attitudes towards offenders among adolescents who practice a religion, those who do not, and the ones who do not perform any kind of religious practice. In adolescent practitioners, we could see a less aggressive presence of aggressive factors, in its three dimensions of ven- geance, resentment and hostility, as well as a higher level in prosocial factors, mainly in the aspect of forgiveness, and to a lesser extent in explanation request, in comparison to adoles- cent non-practitioners. Religious practice increases levels of social participation, it is a source of emotional support (Scholte et al., 2004; Taylor, Nailatikau, & Walkey, 2002), and can provide a sense of be- longing (Lepore & Revenson, 2006). Within it, the concept of forgiveness gets highly relevant in adolescence (Enright, Maria, & Radhi, 1989). This has been shown in recent studies by Laufer, Raz-Hamama, Levine and Solomon (2009), who found out that religious youngsters were more likely to forgive than those who were not; a conclusion that agrees with our research. On the other hand, we observed a significant influence of re- ligious practice on situations and themes of conflict and recon- ciliation. These findings are consistent with the views express- ed by the authors Bock (2002) and Cjeka and Bamat (2003), as regards the role of religion in conflict situations, and especially the role of religious leaders and the congregation, in promoting peace and reconciliation. The results obtained become more relevant due to being an understudied area. Recent investigations have argued that religious attitudes and the promotion of non-violence, would be associated with fa- cilitating apology and forgiveness in conflict resolution (Ashy, Mercury, & Malley-Morrison, 2010). This is consistent with the results of this study, confirming that religious practice influ- ences positively on forgiveness in situations of offence. This study highlights the importance of religion, Christian in this case, in the development of prosocial attitudes and control of aggressive attitudes against the offender. It is recommended for future research to match the size of the sub-samples in relation to the sex of the participants, as in the present investigation, the sub-sample of female is higher than male. The inquiry into religious practice should also be deep- ened, taking into account rituals, days of the week assigned for religious practice, amount of time devoted to it, etc. The most important limitations of this paper are: 1) the sam- ple is focused on people of a specific area, 2) it comprises only subjects from 16 to 22 years old, and 3) it doesn’t investigated the religious practice of non-Christian believers. REFERENCES Alberti, R. E. (1977). Assertiveness: Innovations, applications, issues.  L. M. RODRIGUEZ, J. E. MORENO San Luis Obispo, CA: Impact. Ashy, M., Mercurio, A. E., & Malley-Morrison, K. (2010). Apology, forgiveness, and reconciliation: An ecological world view framework. Individual Differences Research, 8, 17-26. Bar-On, R. (1994). EQI: The emotional quotient inventory. Doctoral Dissertation, Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University. Bock, J. G. (2002). Sharpening conflict management: Religious lead- ership and the two-edged sword. Westwood, Connecticut: Praeger. Carretero, A. (2010). En torno a las fórmulas alternativas de religio- sidad. La re-elaboración de nuevas modalidades de vínculo comuni- tario. Athenea Digital, 17, 119-136. http://psicologiasocial.uab.es/athenea/index.php/atheneaDigital/articl e/view/663 Cjeka, M. A., & Bamat, T. (2003). Artisans of peace: Grassroots peace- making among Christian communities. New York: Orbis, Maryknoll. Costa, P., & McCrae R. (1995). The revised NEO personality inventory. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources. Derogatis, L. R. (1977). SCL-90 (revised) version manual-1. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Universty. Enright, R. D., Maria, J. D. S., & Radhi, A. L. (1989). The adolescent as forgiver. Journal of Adolescence, 12, 95-110. doi:10.1016/0140-1971(89)90092-4 Enright, R. D., & Rique, J. (2004). The enright forgiveness inventory sampler set manual, instrument, and scoring guide. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden. Fromm, E. (1973). The anatomy of human destructiveness. New York: Henry Holt. Kancyper, L. (2006). Resentimiento y remordimiento. Buenos Aires: Lumen. Kohlberg, L. (1975). Collected papers on moral development and moral education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Laufer, A., Raz-Hamama, Y., Levine, S., & Solomon, Z. (2009). Post- traumatic growth in adolescence: The role of religiosity, distress, and forgiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 862-880. doi:10.1521/jscp.2009.28.7.862 Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. Lepore, S. J., & Revenson, T. A. (2006). Resilience and posttraumatic growth: Recovery, resistance, and reconfiguration. In L. G. Calhoun, & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth, re- search and practice (pp. 24-46). Mahwah, NJ: Routledge. Moreno, J. E., & Fernández, C. (2011). Empatía y flexibilidad yoica, su relación con la agresividad y la prosocialidad. Límite. Revista de Filosofía y Psicología, 23, 41-55. Moreno, J. E., & Pereyra, M. (2000). Cuestionario de Actitudes ante Situaciones de Agravio. Manual. Libertador San Martín, Entre, Ríos: Universidad Adventista del Plata. Murphy, P., Ciarrochi, J. W., Piedmont, R. L., Cheston, S., Peyrot, M., & Fitchett, G. (2000). The relation of religious belief and practices, depression, and hopelessness in persons with clinical depression. Journal of Consulting and Clin ic al Psychology, 68, 1102-1106. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1102 Mussen, P., & Eisenberg, N. (1977). Caring, sharing, and helping: The roots of prosocial behavior in children. San Francisco: Freeman. Nelson, W. M. (1978). Diccionario Ilustrado de la Biblia. Miami: Edi- torial Caribe. Pereyra, M. (1995). Hope-hopelessness as a diagnostic and predictive variable in the health-illness process. Doctoral Dissertation, Córdoba (Argentina): Universidad Católica de Córdoba. Pereyra, M. (1996). Development and validation of an instrument to mesure hope-hopelessness. Acta Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de Amé- rica Latina, 42, 247-259. Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) (2012). Diccionario de la Lengua Es- pañola. http://www.rae.es/rae.html Roche Olivar, R. (1998). Psicología y educación para la prosocialidad. Bs. As.: Ciudad Nueva. Roche Olivar, R. (1999). Desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional y social desde los valores y actitudes prosociales en la escuela. Bs. As.: Ciudad Nueva. Scheler, M. (1998). El resentimi ento en la moral. Madrid: Caparrós. Scholter, W. F., Olff, M., Ventevogel, P., De Vries, G. J., Jansveld, E., Lopes Cardozo, B., & Gotway Crawford, C. A. (2004). Mental health symptoms following war and repression in eastern Afghanistan. The Journal of the American Medicine Association, 292, 585-593. doi:10.1001/jama.292.5.585 Spielberger, C. D., Johnson, E. H., Russell, S. F., Crane, R. J., Jacobs, G. A., & Warden, T. J. (1985). The experience and expression of anger: Construction and validation of an anger expression scale. In M. A. Chesney, & R. H. Rosenman (Eds), Anger and hostility in car- diovascular and behavioral disorders (pp. 5-30). Washington DC: Hemisphere. Staub, E. (1975). To rear a prosocial child: Reasoning, learning by do- ing and learning by teaching others. In D. J. De Palma, & J. M. Foley (Eds.), Moral development: Current theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Taylor, A. J. W., Nailatikau, E., & Walkey, F. H. (2002). A hostage trauma in Fiji. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 6, 1174-4707. Vergote, A. (1969). Psicología religiosa. Madrid: Taurus. Wispé, L. G. (1972). Positive forms of social behavior: An overview. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 1-19. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1972.tb00029.x Worthington, E. L., Kurusu, T. A., Collins, W., Berry, J. W., Ripley, J. S., & Baier, S. N. (2000). Forgiving usually takes time: A lesson learned by studying interventions to promote forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 28, 3-20. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 628

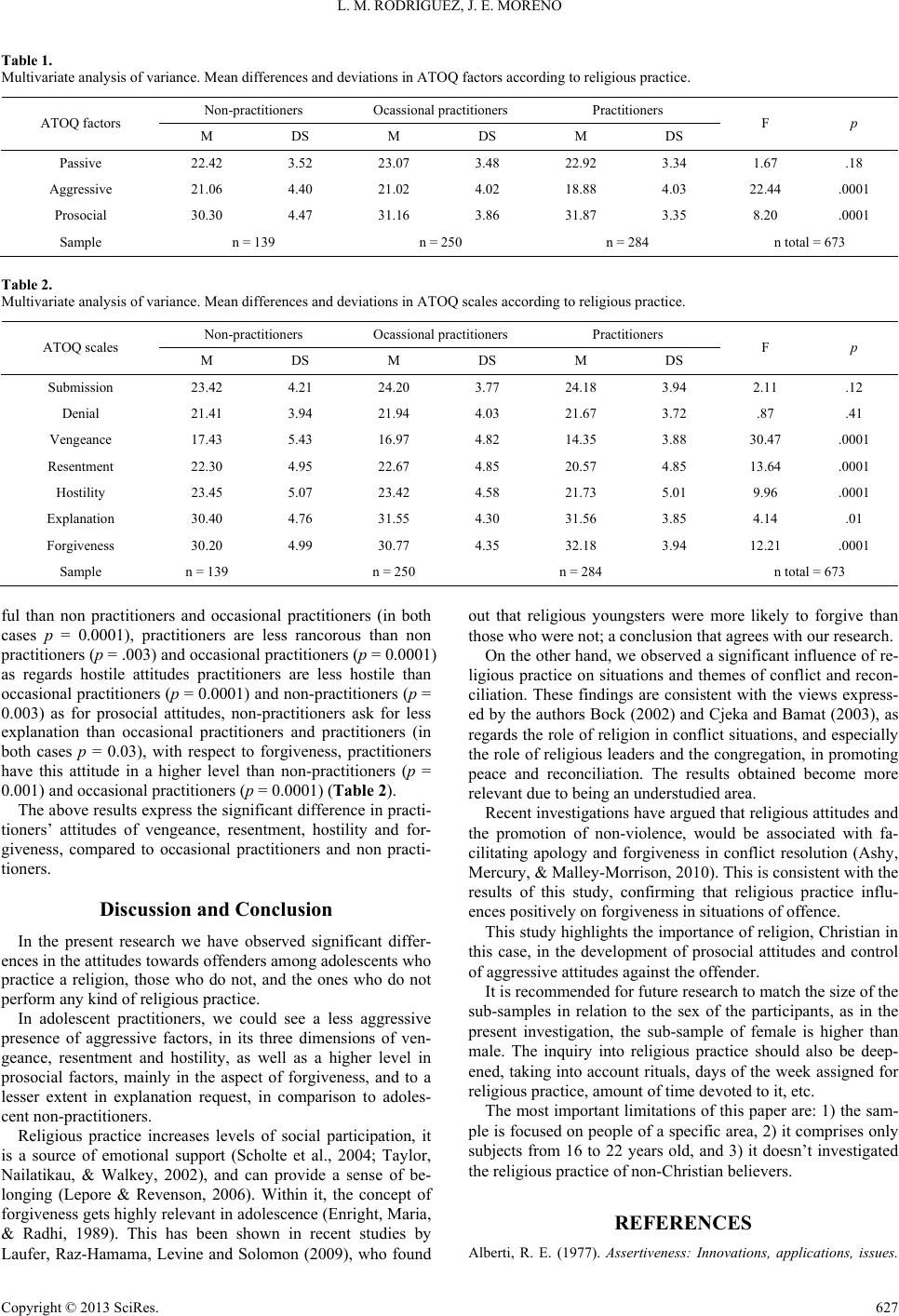

|