American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2013, 3, 367-377 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.34043 Published Online August 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajibm) 367 Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management Thomas Scannell1, Sime Curkovic2, Bret Wagner2 1Department of Management, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, USA; 2Department of Management, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, USA. Email: thomas.scannell@wmich.edu, sime.curkovic@wmich.edu, bret.wagner@wmich.edu Received January 12th, 2013; revised February 12th, 2013; accepted March 12th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Thomas Scannell et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Supply chain risk management (SCRM) can provide companies with a long-term competitive advantage, particularly if it is integrated with enterprise risk management (ERM). Current SCRM research frameworks do not explicitly examine this integration, potentially hindering a deeper understanding of SCRM. This research uses survey data and follow-up interviews to suggest that ISO 31000:2009 provides a foundation for advancing future SCRM research, and to more successfully execute SCRM. It is also determined that ISO 31000:2009 encompasses existing SCRM frameworks, but is more exhaustive. It includes two critical steps generally omitted from SCRM frameworks: 1) developing a strategic context for SCRM, and 2) performance monitoring. Finally, it was found that firms recognize the importance of SCRM, but SCRM integration and skills are lacking. Keywords: IS0 31000:2009; Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM); Enterprise Risk Management (ERM); Survey 1. Introduction Enterprise risk management (ERM) is a critical compo- nent of business strategy [1]. Despite ERM’s importance, ERM implementation is limited [2]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) released ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management Principles to provide ERM implementation guidance [3]. A key component of ERM is supply chain risk man- agement (SCRM) [4,5]. A well designed, risk-oriented supply chain provides a strong competitive position and reliable long-term benefits to all stakeholders [6]. For SCRM to be most effective, it should be integrated with ERM. However, SCRM is often implemented in an ad-hoc manner. SCRM research is in its infancy stage [7]. SCRM research might advance more readily if research is linked to practitioner needs, and if a standard SCRM framework is developed [8]. This research has two primary goals: 1) determine whether ISO 31000 provides the framework to reach consensus on SCRM scope and definition, which in turn could accelerate SCRM research, and 2) determine whether ISO 31000 provides the foundation for planning and executing SCRM. To pursue these goals, survey data and follow-up in- terviews were used. Findings suggest that ISO 31000 provides researchers a framework for developing a con- sensus on SCRM terms and scope, and provides practi- tioners with a foundation for linking ERM and SCRM, and then planning and executing SCRM. The findings also suggest that though companies recognize the impor- tance of SCRM, SCRM is not generally linked to ERM and that key SCRM skills are lacking. 2. Literature Review SCRM research gaps include a lack of agreement re- garding SCRM scope and definition, and a lack of em- pirical research focused on current practices [8]. This research accepts the perspective that empirical research focused on developing frameworks may advance re- search [8]. The total quality management (TQM) disci- pline provides an example. TQM research advancements were supported by operational definitions and standard- ized frameworks, which provided a foundation for theory building and testing [9-13]. While TQM research has reached a “mature” stage, SCRM research is in an “early” stage. For example, [7] suggested that SCRM research regarding crisis situations was in its “infancy” stage, then examined the literature and conducted interviews to develop a theoretically grounded framework for examining supply crisis man- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 368 agement [7]. Driven by the suggestions that SCRM re- search is in an early stage, that a standard SCRM frame- work may advance research, and that SCRM is a subset of ERM, this exploratory research examines SCRM rela- tive to the ISO 31000 framework. 2.1. ISO 31000:2009 ERM has received attention as a way to gain competitive advantage, yet has not gained much traction [14]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) published ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management Principles and Guidelines [3] to provide a foundation for ERM im- plementation. It is anticipated that ISO 31000 will be- come an international norm for ERM [15]. This research focuses on ISO 31000, Clause 5 Risk Management Proc- ess, which consists of five integrated segments [16] (Figure 1). Communication and consultation (5.2) requires en- gagement of stakeholders to determine objectives, secure involvement, and to disseminate risk information. Estab- lishing the context (5.3) sets objectives, identifies factors that influence success, appraises stakeholder relation- ships, and identifies the risk management environment. This essential step precedes risk assessment. Risk assessment (5.4) consists of three interrelated steps. “Risk identification” defines risks, and identifies risk drivers and risk categories. “Risk analysis” evaluates risk, including potential business consequences and oc- currence likelihood. “Risk evaluation” prioritizes risks from acceptable to unacceptable, and identifies which risks require treatment. Risk treatment (5.5) identifies options for treating risks, including: accepting risk to achieve competitive advan- tage; avoiding risk; reducing or removing the likelihood or consequence of risk; and sharing or transferring risk. Monitoring and review (5.6) analyzes changes in risks and the emergence of new risks that result from changes in the external environment, risk treatment, or corporate objectives. It also assesses the success of risk treatments. 2.2. SCRM Frameworks SCRM frameworks [17-19] share common elements with each other and with ISO 31000. However, Table 1 iden- tifies a lack of consensus regarding what constitutes SCRM, and indicates that ISO 31000 is more compre- hensive than SCRM frameworks. ISO 31000 emphasizes that the first critical step for enabling holistic risk man- agement is establishing the context. It also explicitly recognizes the need for stakeholder engagement and communication, and emphasizes continuous monitoring, review, and improvement. 2.3. Supply Risks and Responses The research identifies many supply risks, including but not limited to order fulfillment problems, information delays, labor tensions, natural disasters, capacity fluctua- tions, bankruptcy, exchange rates, government regula- tions, security, and opportunism [19-23]. Risk treatments might include dual-sourcing [24], credit analysis [25], use of capable suppliers [19], building structural flexibil- ity into supply chain designs [26], supply chain modeling [27], inventory buffers [23], trust development [27], or contingency planning [28,29], for example. 3. Research Method This exploratory research selected a purposeful sample to pursue the research objectives [30]. Targeted participants were known to support supply research and education, and were active in professional supply associations. The survey was sent to 58 firms. A 66% response rate was achieved. Early-to-late respondent survey comparisons were made to analyze potential nonresponse bias [31]. No statistically significant differences were found. The Figure 1. ISO 31000:2009 clause 5 process for managing risk. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 369 Table 1. ISO 31000:2009 and SCRM frameworks. ISO 31000:2009 5.2 Communication and Consultation 5.3 Establishing the context 5.4.2 Risk identification 5.4.3 Risk analysis 5.4.4 Risk evaluation 5.5 Risk treatment 5.6 Monitoring and review Hallikasa et al., 2004 Risk identification Risk assessment Decision and implementation of risk management actions Risk monitoring Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005 Specifying sources of risks and vulnerabilities Assessment Mitigation Selection of appropriate risk management strategies Implementation of supply chain risk management strategies Manuj & Mentzer, 2008 Risk Identification Risk assessment and evaluation Mitigation of supply chain risks Tummala & Schoenherr, 2011 Risk measurement Risk Identification Risk assessment Risk evaluation Risk mitigation & contingency plans Risk control & monitoring majority of responses were from manufacturing firms (Table 2). Sales volume, number of employees and re- spondent titles are shown in Tables 3-5 respectively. 4. Data Analysis Results are categorized relative to the segments of ISO 31000:2009. In all tables, the “agree/disagree” questions are scaled from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”, and the “extent of use” questions are scaled from “1 = not used” to “7 = extensively used”. 4.1. Communication and Consultation Table 6 suggests that firms attempt to create communi- cation channels supported by extensive information gath- ering. Though information visibility was relatively high, there are concerns regarding information reliability and timeliness. 4.2. Establishing the Context Contextual factors were categorized as needed, approach, budget, and organization (Table 7). Although SCRM is strategic, there is a challenge to implement SCRM, be- cause no single set of tools exists for managing all risks. SCRM personnel lack insights into ERM efforts and may lack critical skills for managing global risk. Organiza- tional structures and capabilities, as well as the allocation of resources and budgets, appear to be misaligned with strategic objectives. Table 2. Industry profile. Industry Count Manufacturing 11 Automotive 10 Aerospace/Defense 4 Consumer Products 3 Health Care 2 Construction 2 Other 6 Table 3. Sales. Sales Count $10M - $49M 1 $50M - $99M 3 $100M - $499M 2 $500M - $999M 4 $1B - $9B 7 $10B - $49B 15 $50B - $99B 3 Over $100B 3 Table 4. Employment. Employees Count 50 - 99 1 100 - 499 3 500 - 999 2 1000 - 4999 6 5000 - 9999 3 Over 10,000 23 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 370 Table 5. Respondent titles. Titles Percent Supply Chain Leader/Manager/Buyer 54% Production/Operations/Materials Manager 29% Analyst 17% Table 6. Communication and consultation. Item Mean Std. Dev. Establishing good communications with suppliers 5.81 1.05 Information gathering 5.51 1.54 Forecasting techniques (e.g., to pre-build & carry additional inventory of critical items) 4.79 1.56 Our company uses real-time inventory information and analytics in managing the supply chain. 4.61 1.66 Data warehousing 4.59 1.54 Visibility (detailed knowledge of what goes on in other parts of the supply chain—e.g., finished goods inventory, material inventory, WIP, pipeline inventory, actual demands and forecasts, production plans, capacity, yields, and order status) 4.24 1.46 Demand signal repositories 3.95 1.68 Supply chain risk information is accurate and readily available to key-decision makers. 3.81 1.68 Network design analysis programs 3.41 1.40 4.3. Risk Assessment Risk assessment consists of the interrelated steps of iden- tification, analysis, and evaluation. Specific risk factors (e.g., supplier reliability) are carefully evaluated (Table 8). However, few firms extensively document the likely- hood and impact of risks, and SCRM tends to focus on “negative risks” rather than exploiting “positive risks”. Firms face a wide range of supply risks (Table 9). Supplier failure/reliability was the top risk, followed by supplier bankruptcies, natural disasters, commodity cost volatility, and logistics failure. Table 10 summarizes responses regarding whether supply risks would increase, stay the same, or decrease in the next 1 - 2 years. Many of the risk factors identified as increasing (e.g., currency exchange, government regulations) highlight that many risks are outside of supply’s direct control, suggesting that successful treatment of such risks will require inte- grated SCRM and ERM. 4.4. Risk Treatment Risk treatment options include acceptance, reduction, and sharing (Table 11). Inventory buffering remains a key acceptance option. Qualifying suppliers to reduce risk and partnering with suppliers to share risk are also extensively used. Table 7. Establishing the context. NEED Mean Std. Dev. Without a systematic analysis technique to assess risk, much can go wrong in a supply chain. 6.19 0.97 Managing supply chain risk is an increasingly important initiative for our operations. 5.92 1.19 It is critical for us to have an easily understood method to identify & manage supply chain risk. 5.27 1.52 My workplace plans on evaluating or implementing supply chain risk tools and technologies. 5.08 1.91 We are very concerned about our supply chain resiliency, and the failure implications. 4.81 1.65 APPROACH There is no single set of tools or technologies on the market for managing supply chain risks. 5.50 1.34 We are currently using some form of supply chain risk management tools and services. 5.03 1.83 Managing supply chain risks is driven by reactions to failures rather being proactively driven. 4.19 1.67 Proactive risk mitigation efforts applied to the supply chain is common practice for us. 4.19 1.76 Supply chain risk initiatives are driven from the bottom up rather than top down. 3.70 1.75 BUDGET We do plan on investing nontrivial amounts in managing supply chain risks. 4.17 1.46 We have a dedicated budget for activities associated with managing supply chain risks. 3.89 2.27 Funding for managing supply chain risks will come from a general operations budget. 3.81 2.03 Our spending intentions for managing sup- ply chain risks are very high. 3.08 1.54 ORGANIZATION Supply chain employees understand government legislation & geopolitical is- sues. 3.73 1.61 I fully understand the activities being performed by our risk management group. 3.70 1.54 My workplace uses supply chain risk man- agers who work closely with corporate risk mgmt. 2.64 1.81 We are planning to outsource all or some of our risk management functions. 2.14 1.22 4.5. Monitoring and Review Firms use a range of processes to monitor outcomes (Ta- ble 12). However, few firms benchmark SCRM relative Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 371 Table 8. Clause 5.4: Risk assessment. Item Mean Std. Dev. Supplier reliability and continuous supply is the top risk factor for our supply chain. 5.68 1.43 Risks of moving manufacturing facilities overseas are carefully evaluated. 5.30 1.63 Risks of not being able to fulfill a spike in consumer demand are carefully evaluated. 5.11 1.49 Key metrics are in place to measure the risk associated with key suppliers. 4.68 1.60 We apply high levels of analytical rigor to assess our supply chain practices. 4.38 1.78 A key part of our supply chain management is documenting the likelihood & impact of risks. 4.19 1.60 Taxes such as excise and VAT impact our supply chain decisions. 4.05 1.73 We can actually exploit risk to an advantage by taking calculated risks in the supply chain. 3.97 1.64 to best practices, or use training and design optimization tools to monitor and review SCRM processes. Firms are generally satisfied with key supply performance out- comes (Table 13), though there is room for improvement, particularly in terms of managing commodity and mate- rial price volatility. 5. Discussion 5.1. Communication and Consultation Communication and consultation provide visibility so that supply chain members may access reliable informa- tion. Specific operations information, such as inventory and quality, was generally available. However, data cen- tralization seemed lacking, causing visibility and accu- racy problems. One manager stated that inadequate in- formation flow was a significant supply risk: “Demand variation, extending supply chains, and information speed that is too reactive, will all continue to be major failure modes”. Perhaps limited information visibility and timeliness reinforces the practice of mitigating nega- tive risks, rather than enabling proactive exploitation of positive risk opportunities. For some firms, there was a lack of information tech- nology (IT) integration throughout the value chain. One manager commented that the most significant failure mode he faced was “companies failing to use up-to-date MRP systems, and not accepting change. By relying on old procedures, companies are missing a lot of informa- tion that can be accurate and readily available”. As com- panies continue to use new and global suppliers, IT inte- gration can become a significant challenge. 5.2. Establishing the Context Respondents use many of the individual processes sug- gested by ISO 31000, but it appears that integration is limited and that SCRM approaches are ad-hoc rather than systematic. One manager commented, “We currently do not possess or utilize any tools to identify and analyze risk within the supply chain. All activities currently prac- ticed are from the working knowledge of the buyers”. This was not universally true, as one manager indicated: “Top management at my company recognizes supply risk by investing capital into our systems, training, and peo- ple. Our stock price is a direct correlation to our supply chain success, thus it has a very high level of visibility”. Leaders have responsibility for establishing the con- text from which supply risk will be managed and for de- fining the responsibilities and scope of risk management processes. Despite recognizing a need for integrated SCRM, many firms did not establish a supportive organ- izational context for SCRM. One manager stated: “What is lacking is clear ownership of the supply chain at an executive level. The supply chain group of 200 employ- ees has belonged to the CEO, the head of operations, and the head of purchasing at different times”. Supply chain managers need to present a business case in order to “get a seat at the table” and to secure requisite SCRM resources. Another manager stated: “As managers, you are the voice for your associates and those who may not get the face time with the people who can affect change. The metrics speak for themselves, so managers need to be able to relate the needed resources to areas in the supply chain that need improvement”. If persuasion does not work, it may take a catastrophe for firms to realize SCRM’s importance. One manager commented: “We did not have anyone devoted to risk management in the past, but due to the Japan earthquake, tsunamis, Thailand floods, and other large-scale issues, risk management has now become very important. We now have someone dedicated to mitigate risk on all fronts for purchasing due to risks globally”. Despite evidence that supply personnel lack some of the necessary risk management skills, and that supply managers have limited linkage to corporate risk manag- ers, few firms intend to outsource SCRM (though com- ponents of SCRM may be outsourced). One manager commented: “Most of our risk management resources are from within. We rely on the supply chain professionals at a working level to meet with the global supply chain group, as well as plant management. We do outsource some of our financial analysis of our suppliers, where they do an in-depth financial analysis and come back with a letter grade and summary”. 5.3. Risk Assessment Respondents agreed that many things can go wrong in a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM 372 Table 9. Current supply chain risks. Rank Risk Factor 1 2 3 4 5 Count Weighted Points Average Weight Supplier failure/reliability 14 10 6 2 1 33 133 4.03 Bankruptcy, ruin, or default of suppliers, shippers, etc. 8 2 6 2 1 19 71 3.74 Commodity cost volatility 3 3 4 3 2 15 47 3.13 Natural disasters or accidents (tsunamis, hurricanes, fires, etc.) 4 3 4 2 1 14 49 3.50 Logistics failure 2 4 1 5 12 34 2.83 Geopolitical event (terrorism, war, etc.) 1 2 6 1 10 23 2.30 Contract Failure 1 2 1 4 8 20 2.50 Strikes—labor, buyers and suppliers 2 3 1 2 8 21 2.63 Customer-related (demand change, system failure, payment delay) 1 3 1 2 1 8 25 3.13 Energy/raw material shortages and power outages 2 1 4 1 8 20 2.50 Information delays, scarcity, sharing, & infrastructure breakdown 1 1 2 2 6 13 2.17 Government regulations (SOX, SEC, Clean Air Act, OSHA, EU) 1 2 2 5 15 3.00 Intellectual property infringement 1 1 1 2 5 13 2.60 Lack of trust with partners 2 3 5 7 1.40 Diminishing capacities (financial, production, structural, etc.) 1 2 2 5 11 2.20 Contamination exposures—food, germs, infections 2 1 2 5 18 3.60 Legal liabilities and issues 3 1 4 10 2.50 Return policy and product recall requirements 2 2 4 6 1.50 Attracting and retaining skilled labor 1 2 1 4 8 2.00 Currency exchange, interest, and/or inflation rate fluctuations 3 1 4 13 3.25 supply chain without a systematic process for assessing risk, and that they lack a comprehensive supply risk as- sessment process. One manager commented: “The big- gest challenge is that most of the risk assessment relates to financial performance and standing. It does not take into account really the key operational risk issues at the supplier, which impact supplier performance. That really then falls on the supply chain team as part of their vendor selection and ongoing performance evaluations.” Most companies reported a high level of activity devoted to supplier measurement, visiting supplier operations, and consistent monitoring of a supplier’s processes. Only a few firms used dashboards or scorecards to predict risk trends in advance. Most firms prioritize risks, and then allocate resources to manage the most significant risks. Though a Pareto approach is common, one manager cautioned that firms may lose sight of seemingly “minor” risks and the inter- action of those risks: “We need additional sustained al- location of resources to address individual items further down the Pareto that have a lower amount of impact as an individual issue, but can have significant impact when all individual items are combined.” Increasing government regulations were a concern across many industries. Companies recognize the value of complying with regulations, though there is concern that compliance with so many regulations consumes re- sources that might be better allocated to risk efforts. One manager noted: “Compliance risk management activity is taking precedence over an overall supplier risk approach. This challenge is created by regulatory agencies and pushing resources towards certain areas of risk mitigation such as FDA, DOJ, AdvaMED, Sarbanes Oxley, etc. Without some of these distractions, we would be able to free up additional resources to develop and deploy up- dated supplier risk processes that would allow for future risk mitigation and support further growth.” 5.4. Risk Treatment Many of the highest-rated current and future risk factors e.g., natural disasters) are not directly controlled by the (  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 373 Table 10. Projected change in supply chain risks. Risk Decrease Same Increase Currency exchange, interest, and/or inflation rate fluctuations 1 3 34 Commodity cost volatility 4 6 28 Banking regulations and tighter financing conditions 2 9 27 Government regulations (SOX, SEC, Clean Air Act, OSHA, EU) 0 14 24 Supplier failure/reliability 7 14 17 Geopolitical event (e.g., terrorism, war) 0 22 16 Energy/raw material shortages and power outages 1 21 16 Customs acts/Trade restrictions and protectionism 3 19 16 Logistics failure 5 17 16 Bankruptcy, ruin, or default of suppliers, shippers, etc. 6 16 16 Customer related (demand change, system failure, payment delay) 2 21 15 Diminishing capacities (financial, production, structural, etc.) 5 18 15 Return policy and product recall requirements 1 23 14 Port/cargo security (information, freight, vandalism, sabotage, etc.) 1 24 13 Legal liabilities and issues 1 24 13 Insurance coverage 0 26 12 Tax issues (VAT, transfer pricing, excise, etc.) 0 27 11 Natural disasters or accidents (tsunamis, hurricanes, fires, etc.) 1 26 11 Intellectual property infringement 1 28 9 Attracting and retaining skilled labor 7 22 9 Language and educational barriers 11 18 9 Strikes (labor, buyers, or suppliers) 4 26 8 Property development (local codes and requirements) 1 30 7 Unfamiliar business and property laws 2 29 7 Weaknesses in the local infrastructures 5 26 7 Contract failure 6 25 7 Contamination exposures (food, germs, infections) 3 29 6 Ethical issues (working practices, health, safety, etc.) 5 27 6 supply organization, so reacting quickly through contin- gency planning is required. One manager commented: “I believe there is no clear solution for every situation. Having thorough contingency plans for each part is a must, and based from that assessment, a decision needs to be made by management. Having a budget for supply security is a must even though you may never use it.” One respondent indicated that his firm now requires key suppliers to develop contingency plans for their own supply chains as well. Inventory buffering was a commonly used treatment when companies accepted supply risks. Inventory carry- ing costs must be assessed relative to the benefits, as one manager stated: “Pursuit of a long-distance supply chain to leverage low-cost country suppliers necessarily results in higher localized inventory storage near production sites to buffer long lead time demand variation risk. This creates higher inventories, and longer overall supply chain lead times, but achieves overriding delivered mate- rial cost savings to the organization.” Risk reduction efforts emphasized qualification of pre- ferred suppliers. However, one manager pointed out that many of the supplier assessment measures are generic and are not linked with a specific sourcing situation or risk condition. Thus, though a supplier may be approved, the specific needs and risks of each sourcing project should be assessed prior to defaulting to an approved supplier. Development of strong buyer/supplier relationships was a common way to share risk. Some managers ex- pressed concerns that developing relationships on a “personal” basis is increasingly difficult. Challenges to developing “personal” ties included physical distance, imited budget for travel, and the constant switching to l Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 374 Table 11. Risk treatment. ACCEPTANCE Mean Std. Dev. Inventory management (buffers, safety stock levels, optimal order & production qty.) 5.42 1.08 Contingency Planning (jointly with suppliers) 4.63 1.50 We have placed an increased focus on inventory management to deal with supply risks. 4.56 1.46 Our suppliers are required to have secure sourcing, business continuity, & contingency plans. 4.54 1.86 We are prepared to minimize the effects of disruptions (terrorism, weather, theft, etc.) 3.86 1.87 REDUCTION Using an approved list of suppliers 6.11 1.11 Multiple sourcing (rather than sole sourcing) 4.47 1.72 Increasing product differentiation 4.24 1.46 Postponement (delaying the actual commitment of resources to maintain flexibility) 3.97 1.30 SHARING Partnership formation and long-term agreements 5.24 1.15 Supplier development initiatives 5.18 1.41 Speculation (forward placement of inventory, forward buying of raw material, etc.) 4.08 1.38 Hedging strategies (to protect against commodity price swings) 3.92 1.62 We are hedging our raw materials exposure to reduce input cost volatility. 3.65 1.69 Joint technology development initiatives 3.47 1.89 Table 12. Monitoring and review. Item Mean Std. Dev. Supplier performance measurement systems 5.71 1.64 Credit and financial data analysis 5.37 1.34 Visiting supplier operations 5.34 1.24 Business process management 5.11 1.27 Consistent monitoring and auditing of a supplier’s processes 5.03 1.68 Spend management and analysis 5.03 1.70 Contract management (e.g., leverage tools to monitor performance against commitments) 5.00 1.52 Benchmarking (internal, external, industry-wide, etc.) 4.68 1.51 We have placed an emphasis on incident reporting to decrease the effects of disruptions. 4.49 1.76 Inventory optimization tools 4.49 1.68 Training programs 3.79 1.66 We use network design and optimization tools to cope with uncertainty in the supply chain. 3.67 1.64 We actively benchmark our supply chain risk processes against competitors. 3.39 2.02 lowest cost suppliers for example. Few firms extensively used joint technology develop- ment to share risk, which is surprising given that lifecy- cle risks are most effectively addressed at early stage design. One manager suggested why early supplier in- Table 13. Performance satisfaction. Outcome Mean Std. Dev Logistics and delivery reliability 5.32 1.25 Meeting customer service levels 5.19 1.17 Supplier reliability and continuous supply 5.03 1.12 Damage-free and defect-free delivery 5.00 0.94 Order completeness and correctness 4.86 1.29 After sales service performance 4.86 1.09 Inventory management 4.84 1.32 Reduced disruptions in the supply chain 4.54 1.07 Reduced material price volatility 4.32 1.06 Lower commodity prices 4.05 1.20 volvement may be limited: “The supply chain group is taking too long in the analysis of the supply chain deci- sions, thus risking product development/sourcing lead- time. This is created when supply chain cannot finalize supplier analysis in the 3 - 4 weeks that are provided. Eventually the company will move without supply chain because product development needs to continue. This can be resolved by hiring efficient people and also measuring supply chain employees on turning around analysis in less than two weeks.” 5.5. Monitoring and Review Many firms were satisfied with specific supply chain performance outcomes, though such positive outcomes are not universal and there is room for improvement. It is Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 375 not clear if these outcomes are achieved more directly through proactive risk management processes or through reactively battling problems. One manager suggested it was the latter: “Results are achieved through daily fire- fighting instead of continuous improvement due to shortage of resources, inaccurate focus of efforts, and inadequate long-term planning.” It is difficult to directly assess risk management’s im- pacts through anything other than final supply perform- ance, as one manager commented: “In the end, you only know if you made the right decision if you are maintain- ing the level of supply you need to service your custom- ers.” Regardless, firms monitor supply chain perform- ance and risks through supplier visits and assessment systems, ongoing supplier scorecards, and financial risk analysis for example. Few firms benchmark risk man- agement processes relative to external competitive levels. One respondent suggested that being able to specifically measure “risk management success” was not critical: “Our only measure is whether or not our assembly lines were impacted. If not, our contingency plans were suc- cessful. I believe that measuring the success of the plan isn't as important as the thought and ideas generated by having a plan.” 5.6. Managerial Implications Managerial implications were suggested throughout the discussion section above. Supply managers are putting effort into SCRM, yet few managers integrate SCRM with ERM. ISO 31000 provides a foundation for supply managers to make the business case for linking SCRM and ERM, and to secure the resources needed to imple- ment SCRM. Companies often focus on frequently occurring risks or the rare but catastrophic risks. Managers should not lose sight of less frequently occurring risks that perhaps in combination drive significant supply problems. Multi- ple respondents suggested that complex sourcing systems require advanced SCRM approaches, such as process failure mode effects analysis and design of experiments for risk. Supply personnel would require training to ef- fectively use such tools. Information technology (IT) continues to advance and become ubiquitous. Companies should proactively de- velop strategies and plans for using IT to identify and manage supply risks. They should also consider how IT usage impacts the development of “personal” supply re- lationships. Perhaps new methods of developing supply “relationships” will be required, and the skill set of sup- ply personnel will need to expand. As companies expand their global reach, supply per- sonnel will need to develop a better understanding of corporate strategy, ERM practices, and financial tech- niques to manage risks. Such understanding and skills are currently lacking. Supply risks might be most effectively addressed at early-stage product design. However, compressed de- velopment times limit the time allowed for supply risk assessment. Supply managers may consider adopting rapid risk assessment techniques to provide support dur- ing early stage design. Companies should also examine the extent to which supplier qualification processes ex- plicitly examine a supplier’s SCRM capabilities. Stan- dard qualification measures provide some indication of risk management, but fail to explicitly explore if risk management or contingency plans are in place. 5.7. Future Research Questions The following future research questions were developed based on the interviews and survey data: 1) Over the long term, does a formal integrated strategy and structure for SCRM and/or ERM provide appropriate returns? Perhaps SCRM programs that only use contingency budgets pro- vide better returns, even when in the short term they might recover more slowly from rare major disruptions. Situational factors have already been proposed that in- fluence the level of investment in risk management sys- tems [32]. 2) Should SCRM adopt a standard ERM framework in future SCRM research? This research identified that ISO 31000:2009 provides a comprehensive framework for examining SCRM. Has it reached the point that re- searchers should agree to a common framework such as ISO 31000:2009? Will practitioners also find adoption of ISO 31000 useful? 3) How can IT better support SCRM? Though respon- dents used IT to support risk management, there was limited use of IT to model and manage supply risks. IT applications, such as internet-based systems, cloud com- puting, and mobile devices are becoming more secure and ubiquitous. Research questions might include: What are the most effective tools and how can they most effi- ciently be adopted in a value chain? What are the barriers to adoption and how can firms overcome the barriers? 4) What is the most effective SCRM organizational structure? Six Sigma requires that quality is everybody’s business, yet establishes different levels of expertise. Lean systems also establish a hierarchy of responsibility. Would it be more effective to have people manage risk as part of their everyday responsibility, or would a hierar- chy of “risk experts” prove more effective? Further, would it be more effective for firms to focus on their core competencies and to outsource SCRM? 5) Should companies include “design for supply risk management” in product design processes? Most new product development processes already assess risk, though it is not clear if longer-term supply risks are con- sidered. Research suggests that addressing supply risk Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management 376 during new product development has a positive impact [33]. Perhaps “rapid supply risk assessment” techniques similar to “rapid plant assessment” [34] techniques will prove effective. REFERENCES [1] R. Hoyt and A. Liebenberg, “The Value of Enterprise Risk Management,” Journal of Risk and Insurance, Vol. 78, No. 4, 2011, pp. 795-822. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6975.2011.01413.x [2] M. Beasley, R. Clune and D. Hermanson, “ERM: A Sta- tus Report,” The Internal Auditor, Vol. 62, No. 1, 2005, pp. 67-72. [3] ISO, “ISO 31000:2009, Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines,” International Standards Organization, Geneva, 2009 [4] L. Hauser, “Risk Adjusted Supply Chain Management,” Supply Chain Management Review, Vol. 7, No. 6, 2003, pp. 64-71. [5] R. VanderBok, J. Sauter, C. Bryan and J. Horan, “Man- age Your Supply Chain Risk,” Manufacturing Engineer- ing, Vol. 138, No. 3, 2007, pp. 153-161. [6] P. Teuscher, B. Gruninger and N. Ferdinand, “Risk Man- agement in Sustainable Supply Chain Management (Sscm): Lessons Learnt from the Case of GMO-Free Soybeans,” Corporate Social Responsibility and Envi- ronmental Management, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2006, pp. 1-10. doi:10.1002/csr.81 [7] R. G. Richey, “The Supply Chain Crisis and Disaster Pyramid: A Theoretical Framework for Understanding Preparedness and Recovery,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 39, No. 7, 2009, pp. 619-628. doi:10.1108/09600030910996288. [8] M. S. Sodhi, B. G. Son and C. S. Tang, “Researcher’s Perspective on Supply Risk Management,” Productions and Operations Management, Vol. 21, No. 1. 2012, pp. 1-13. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2011.01251.x. [9] S. Black and L. Porter, “Identification of the Critical Factors of TQM,” Decision Sciences Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1, 1996, pp. 1-21. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5915.1996.tb00841.x [10] N. Capon, M. Kaye and M. Wood, “Measuring the Suc- cess of a TQM Programme,” International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, Vol. 12, No. 8, 1994, pp. 8-22. doi:10.1108/02656719510097471 [11] S. Curkovic, S. Melnyk, R. Calantone and R. Handfield, “Validating the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Framework through Structural Equation Modeling,” In- ternational Journal of Production Research, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2000, pp. 765-791. doi:10.1080/002075400189149. [12] J. Dean and D. Bowen, “Management Theory and Total Quality: Improving Research and Practice through Theory Development,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1994, pp. 392-418. [13] B. Flynn, R. Schroeder and S. Sakakibara, “A Framework for Quality Management Research and an Associated In- strument,” Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1994, pp. 339-366. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(97)90004-8. [14] M. Moody, “ERM & ISO 31000,” Rough Notes, Vol. 153, No. 3, 2010, pp. 80-81. [15] D. Gjerdrum and W. Salen, “The New ERM Gold Stan- dard: ISO 31000:2009,” Professional Safety, Vol. 55, No. 8, 2010, pp. 43-44. [16] G. Purdy, “ISO 31000:2009—Setting a New Standard for Risk Management,” Risk Analysis, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2010, pp. 881-886. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01442.x [17] J. Hallikas, I. Karvonen, U. Pulkkinen, V. M. Virolainen and M. Tuominem, “Risk Management Processes in Sup- plier Networks,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 90, No. 1, 2004, pp. 47-58. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2004.02.007 [18] P. R. Kleindorfer and G. H. Saad, “Managing Disruptions in Supply Chains,” Production and Operations Manage- ment, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2005, pp. 53-68. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2005.tb00009.x [19] I. Manuj and J. T. Mentzer, “Global Supply Chain Risk Management,” Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2008, pp. 133-156. doi:10.1002/j.2158-1592.2008.tb00072.x [20] J. Blackhurst, T. Wu and P. O’Grady, “PDCM: A Deci- sion Support Modeling Methodology for Supply Chain, Product and Process Design Decisions,” Journal of Op- erations Management, Vol. 23, No. 3-4, 2005, pp. 325- 343. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2004.05.009. [21] R. Spekman and E. Davis, “Risky Business: Expanding the Discussion on Risk and Extended Enterprise,” Inter- national Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 34, No. 5, 2004, pp. 414-433. doi:10.1108/09600030410545454. [22] R. Tummala and T. Schoenherr, “Assessing and Manag- ing Risks Using the Supply Chain Risk Management Process (SCRMP),” Supply Chain Management, Vol. 16, No. 6, 2011, pp. 474-483. doi:10.1108/13598541111171165. [23] G. Zsidisin and J. Hartley, “A Strategy for Managing Commodity Price Risk,” Supply Chain Management Re- view, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2012, pp. 46-53. [24] O. Khan and B. Burnes, “Risk and Supply Chain Man- agement: A Research Agenda,” The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2007, pp. 197-216. doi:10.1108/09574090710816931 [25] D. Kern, R. Moser, E. Hartmann and M. Moder, “Supply Risk Management: Model Development and Empirical Analysis,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2012, pp. 60-82. doi:10.1108/09600031211202472. [26] M. Christopher and M. Holweg, “Supply Chain 2.0: Man- aging Supply Chains in the Era of Turbulence,” Interna- tional Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Man- agement, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2011, pp. 63-82. doi:10.1108/09600031111101439. [27] M. Giannakis and M. Louis, “A Multi-Agen Based Framework for Supply Chain Risk Management,” Jour- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Integration of ISO 31000:2009 and Supply Chain Risk Management Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM 377 nal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2001, pp. 23-31. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2010.05.001. [28] C. S. Tang, “Perspectives in Supply Chain Risk Man- agement,” International Journal of Production Econom- ics, Vol. 103, No. 2, 2006, pp. 451-488. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2005.12.006. [29] J. Skipper and J. Hanna, “Minimizing Supply Chain Dis- ruption Risk through Enhanced Flexibility,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Manage- ment, Vol. 39, No. 5, 2009, pp. 404-427. doi:10.1108/09600030910973742. [30] M. Miles and A. Huberman, “Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods,” Sage Publications, Newbury Park, 1982. [31] J. S. Armstrong and T. S. Overton, “Estimating Nonre- sponse Bias in Mail Surveys,” Journal of Marketing Re- search, Vol. 14, No. 3, 1977, pp. 396-402. doi:10.2307/3150783. [32] L. Giunipero and R. Eltantawy, “Securing the Upstream Supply Chain: A Risk Management Approach,” Interna- tional Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Man- agement, Vol. 34, No. 9, 2004, pp. 698-713. doi:10.1108/09600030410567478. [33] O. Khan, M. Christopher and B. Burnes, “The Impact of Product Design on Supply Chain Risk: A Case Study,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logis- tics Management, Vol. 38, No. 5, 2008, pp. 412-432. doi:10.1108/09600030810882834. [34] R. E. Goodson, “Read a Plant—Fast,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 80, No. 5, 2002, pp. 105-113.

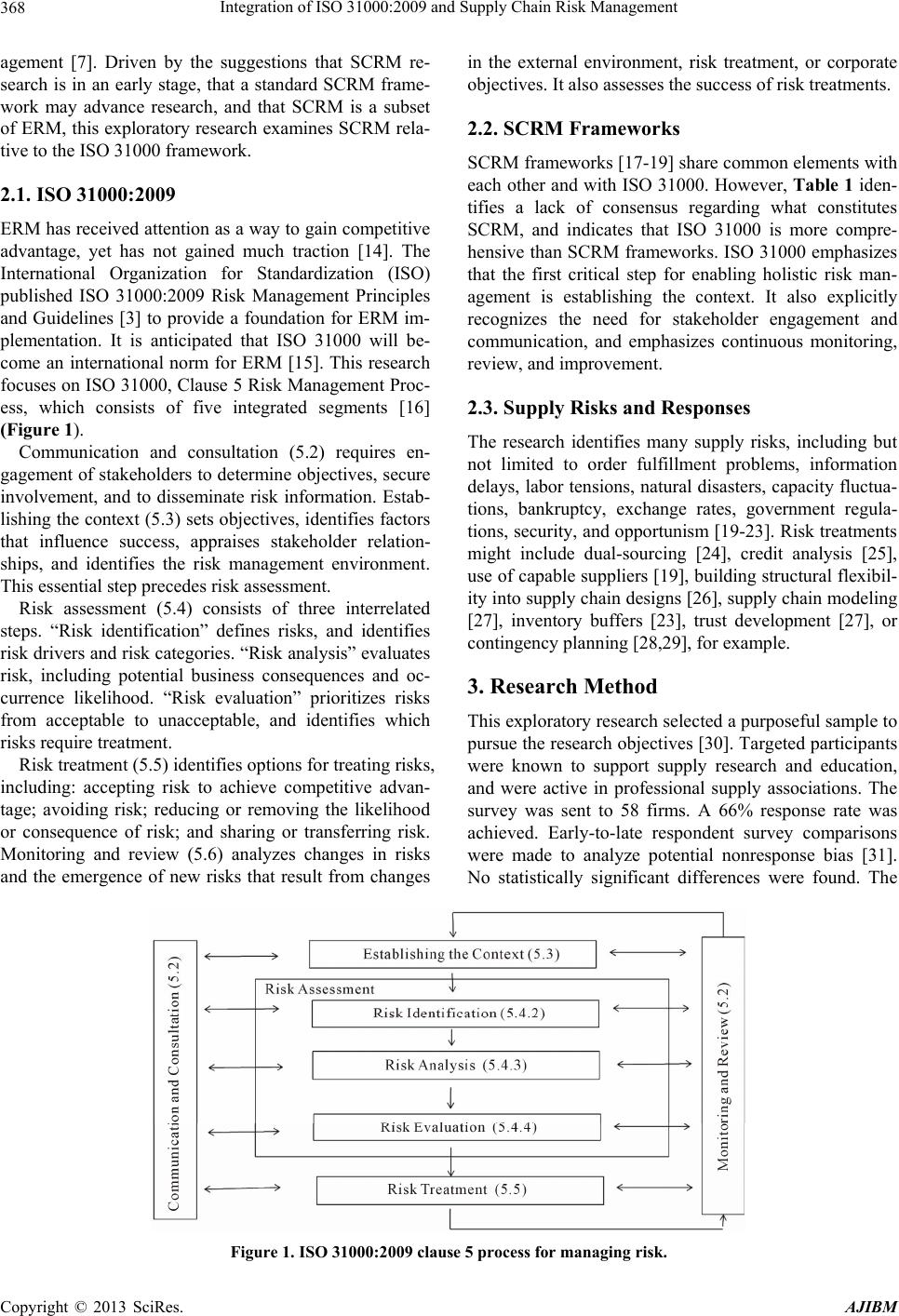

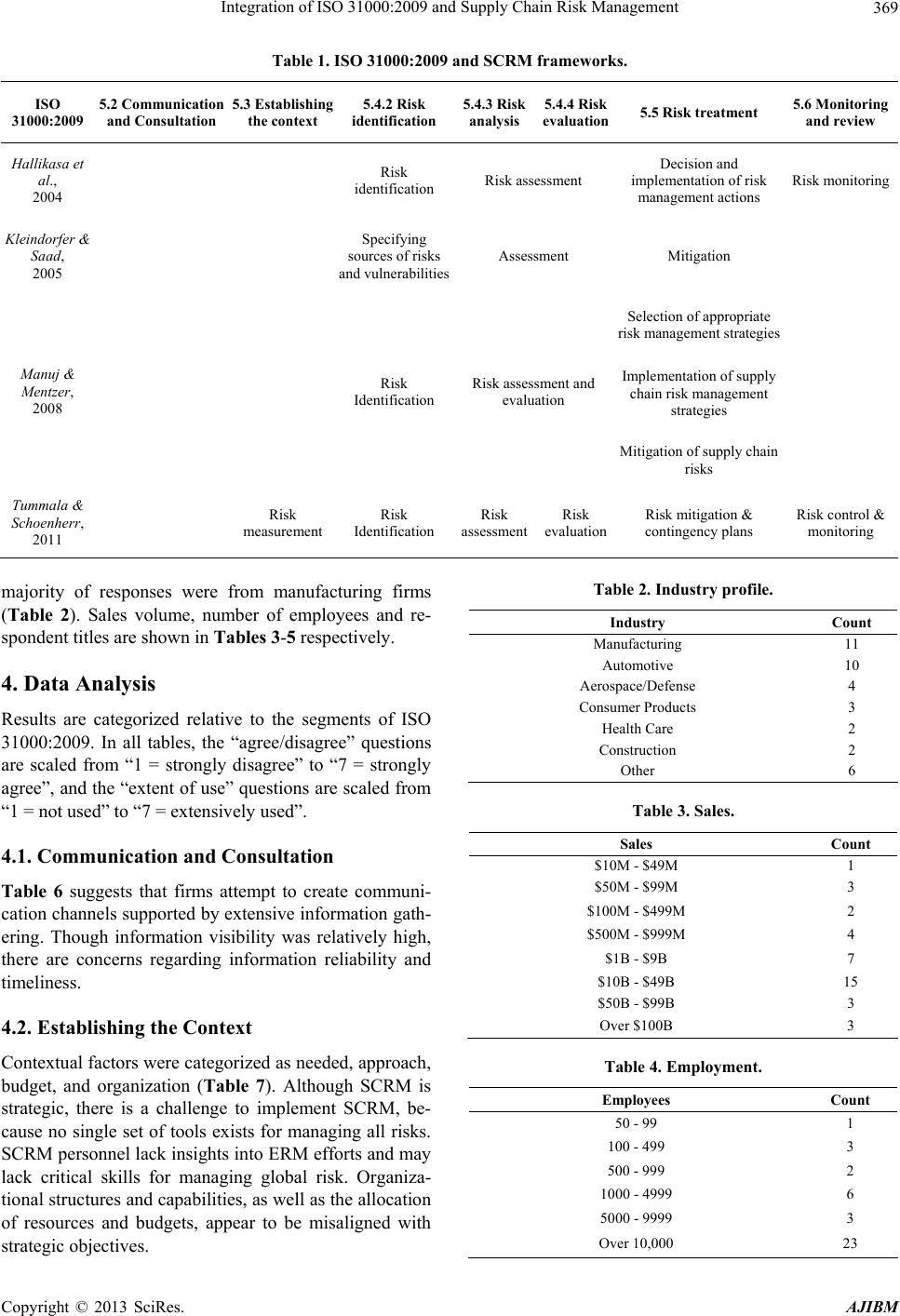

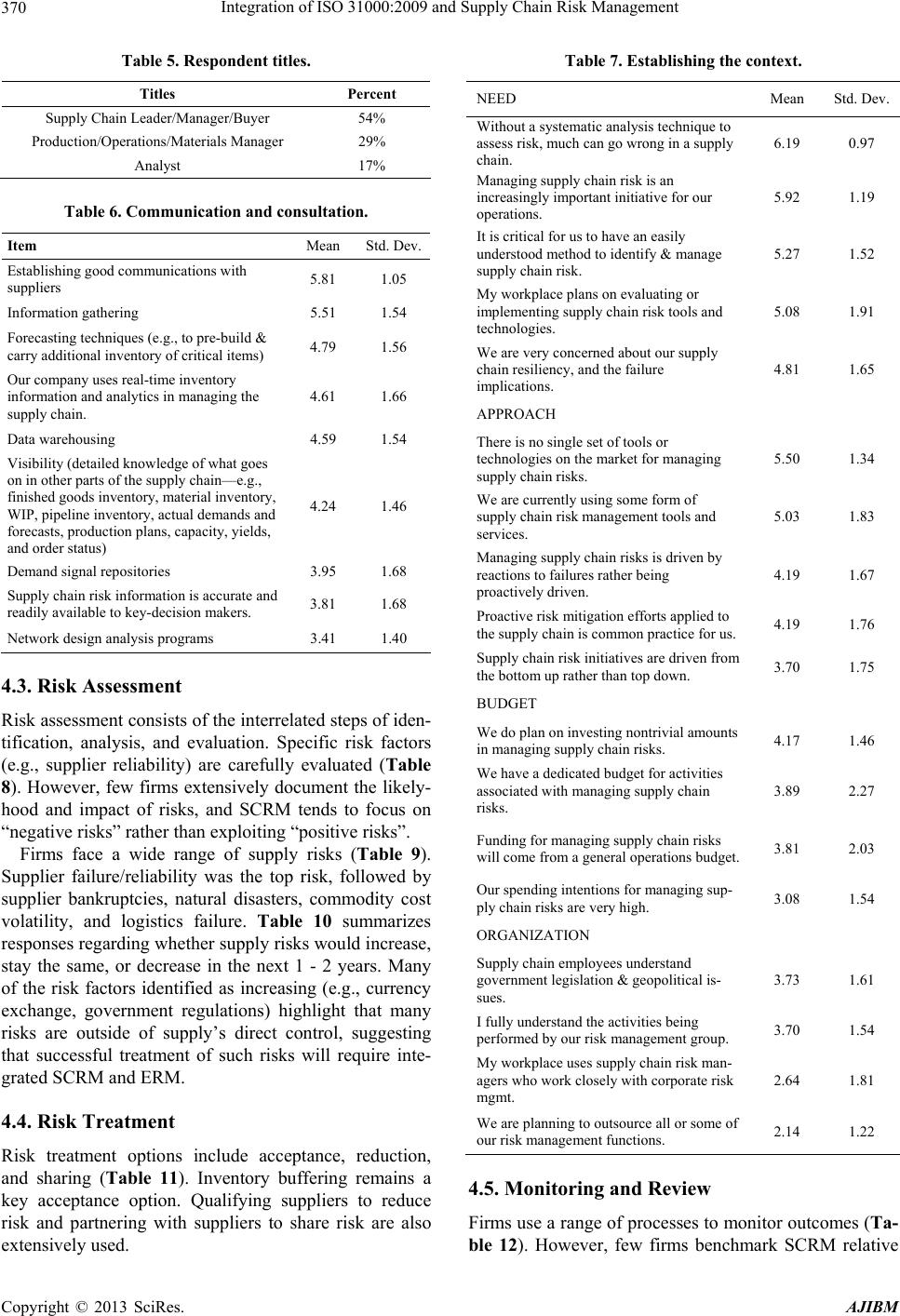

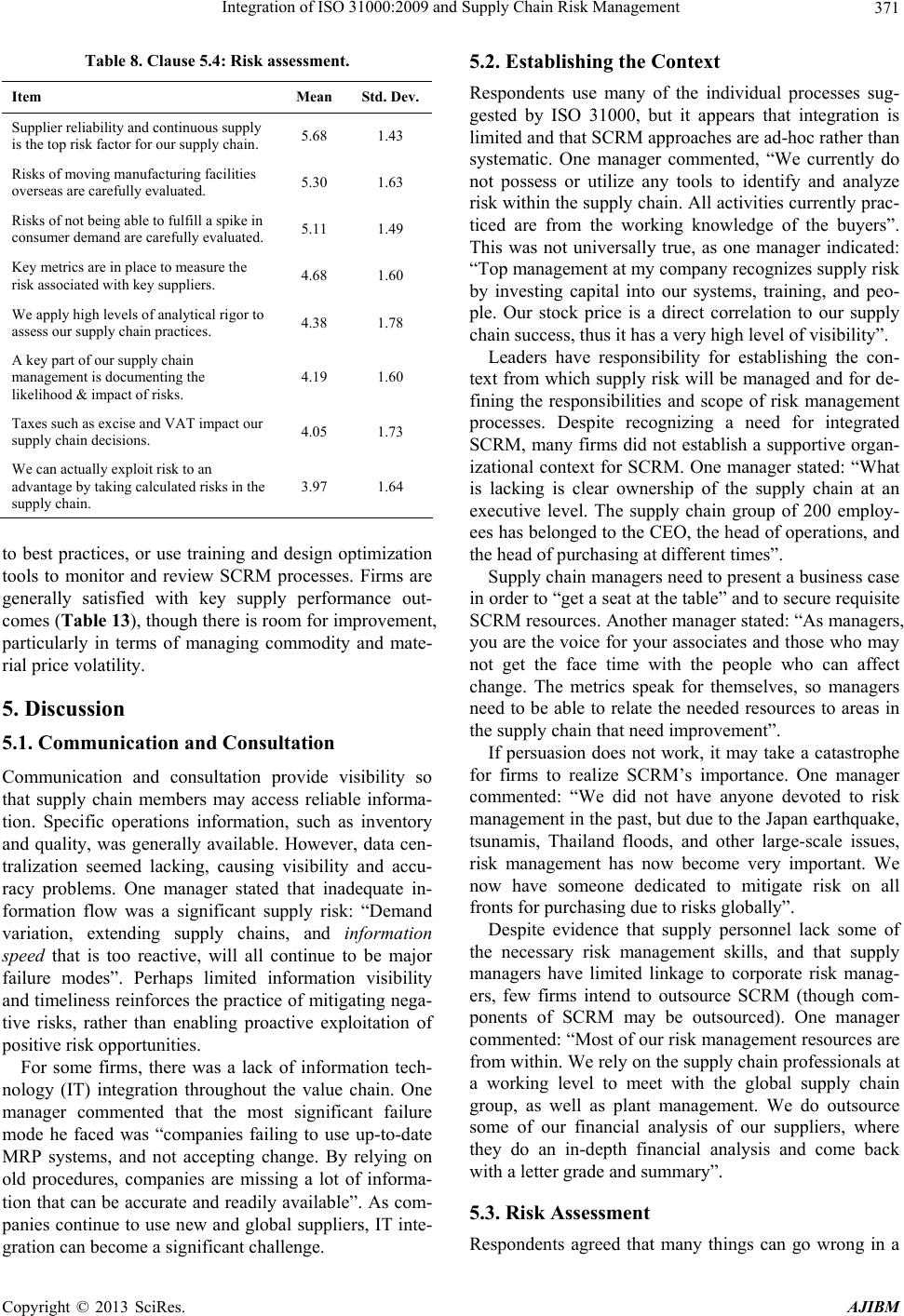

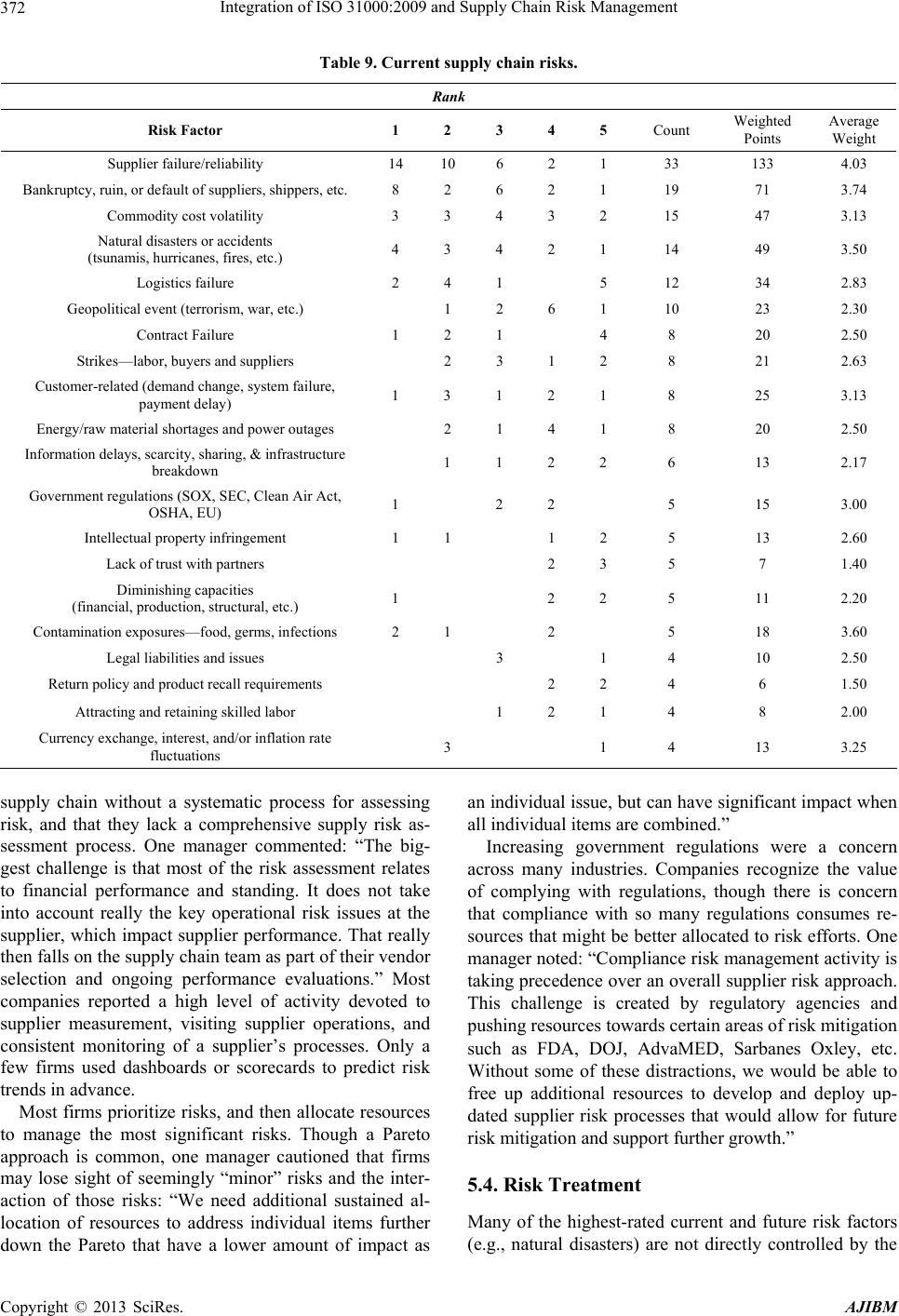

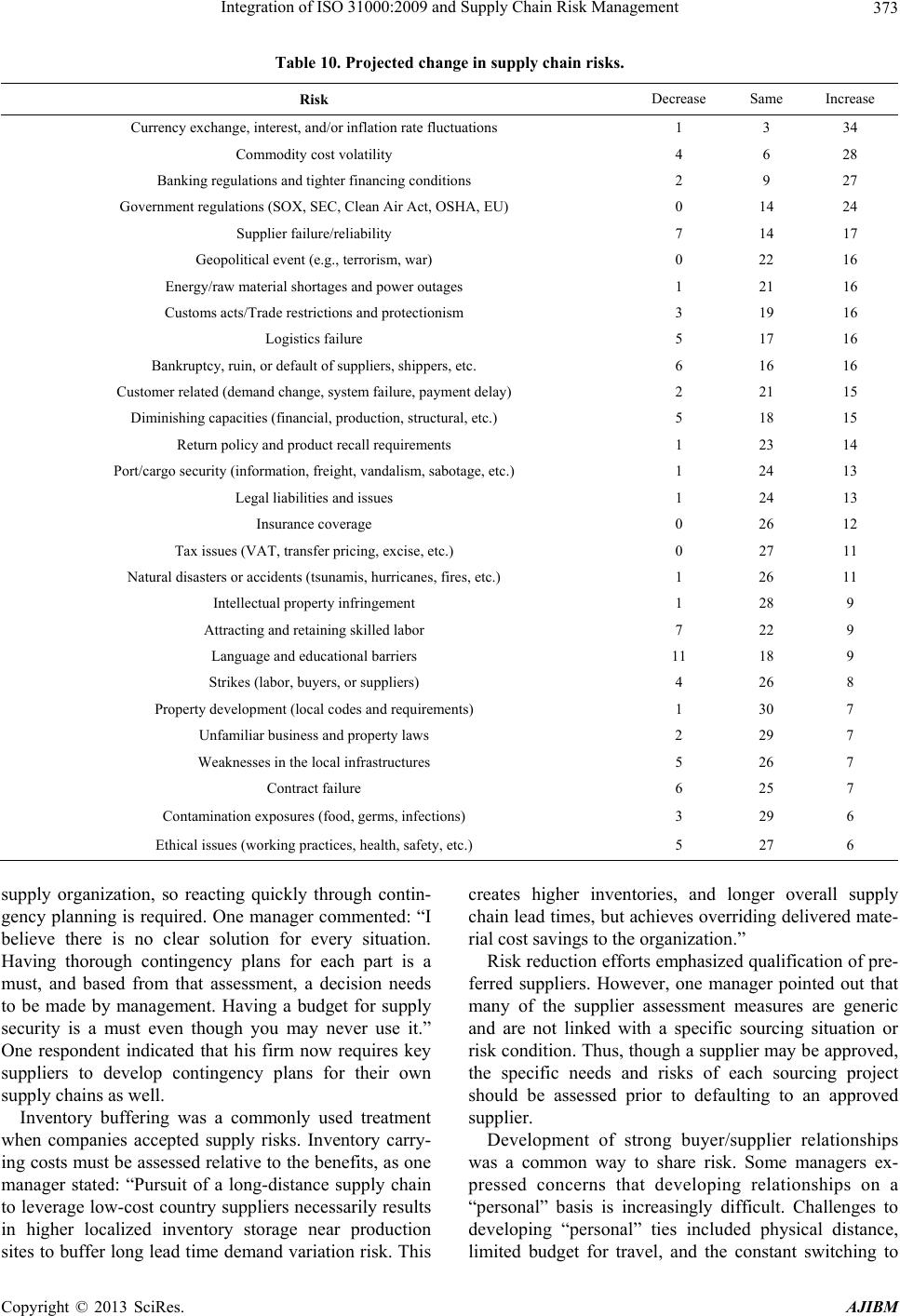

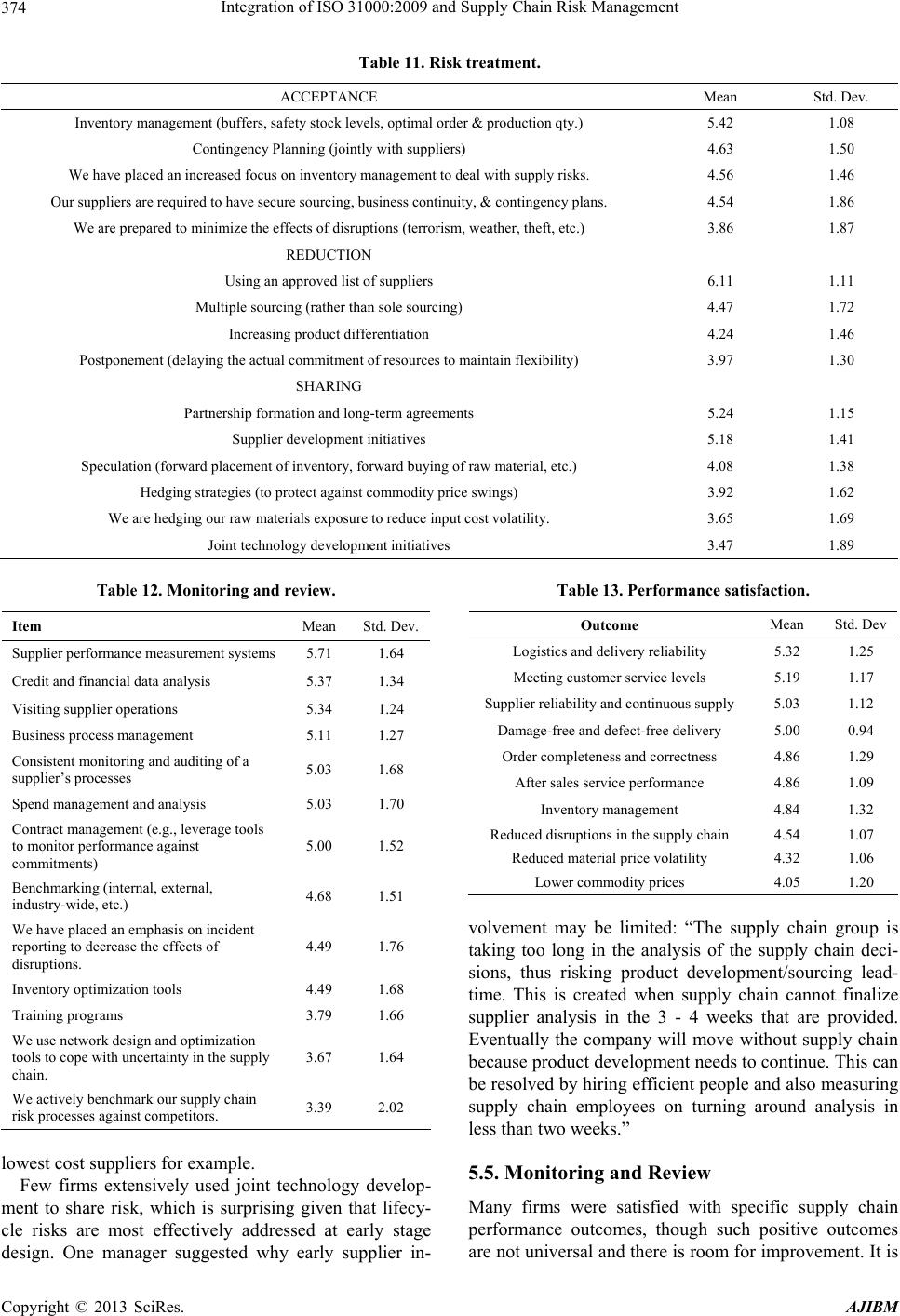

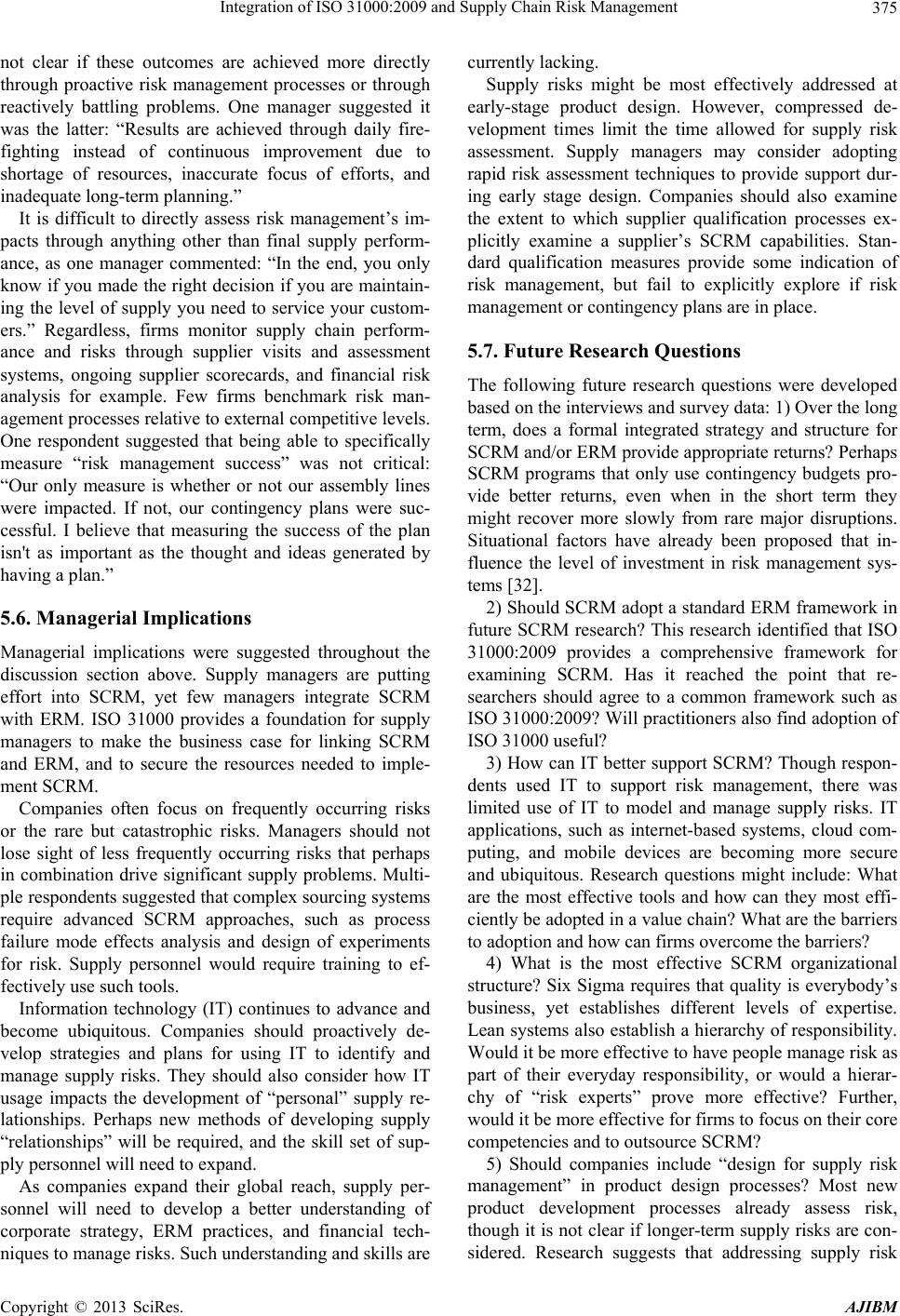

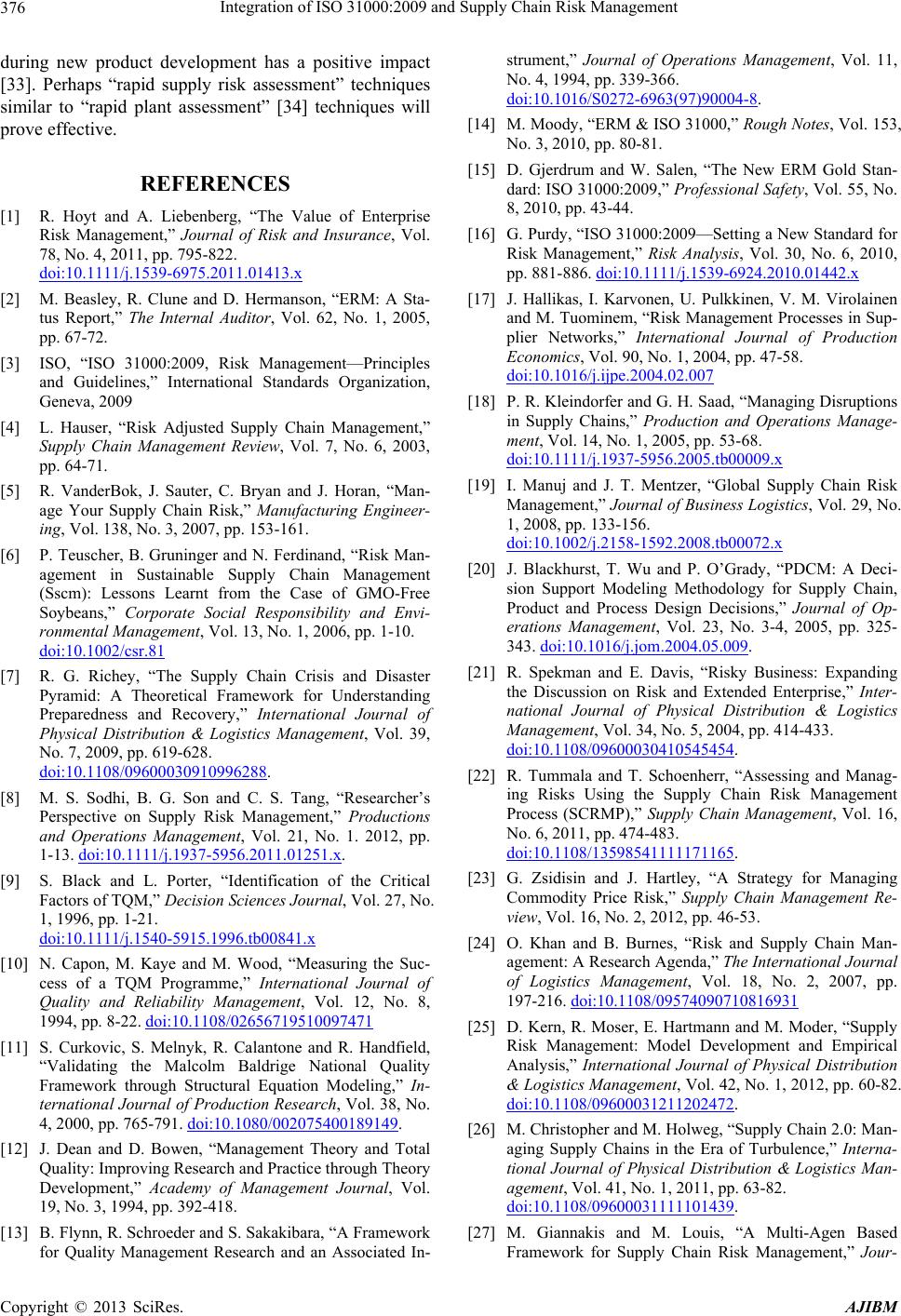

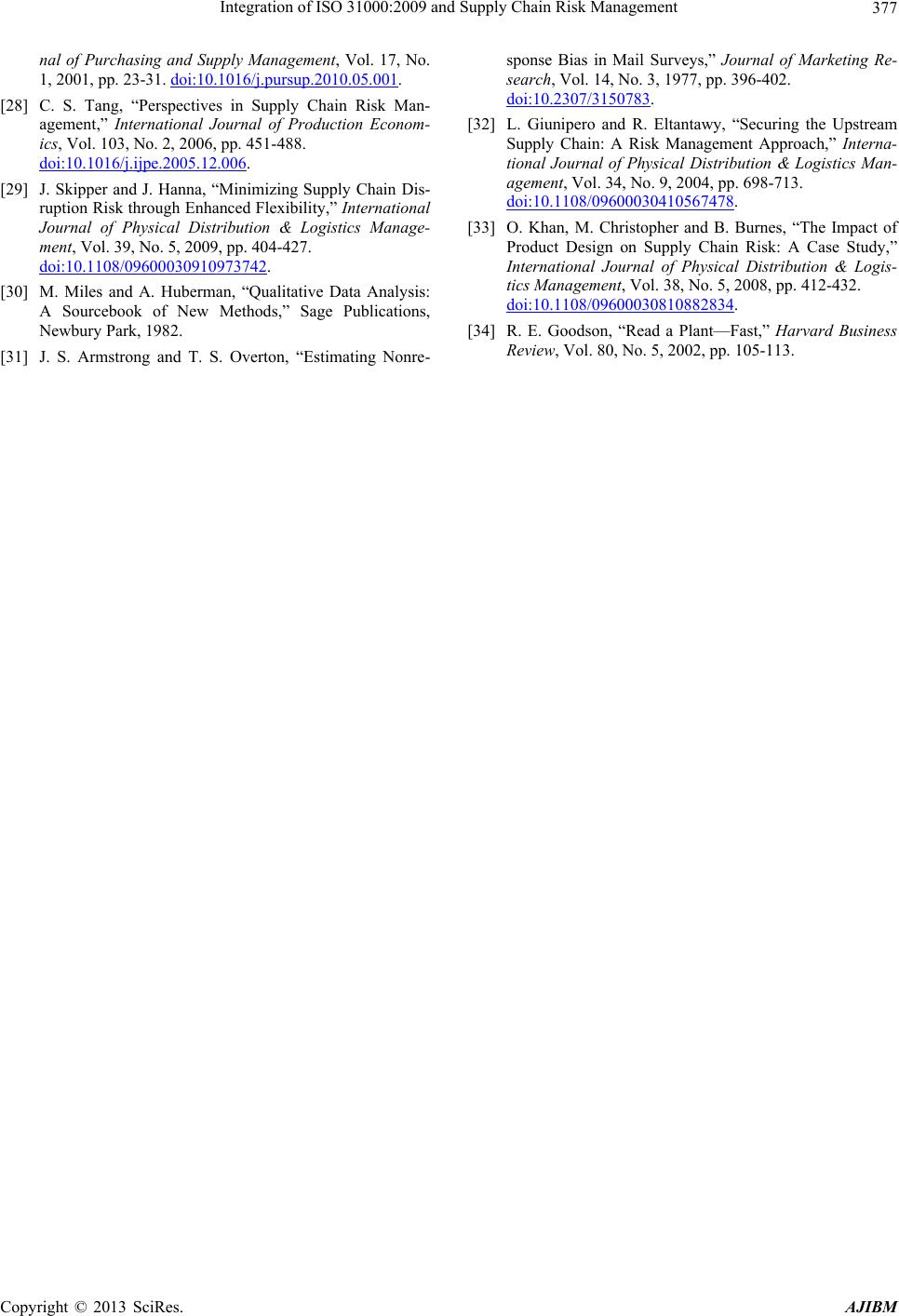

|