Applied Mathematics

Vol.3 No.10A(2012), Article ID:24126,10 pages DOI:10.4236/am.2012.330211

Optimization of Extrusion Process for Producing High Antioxidant Instant Amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.) Flour Using Response Surface Methodology

1Maestria en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos, Facultad de Ciencias Químico-Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, Sinaloa, México

2Programa Regional del Noroeste para el Doctorado en Biotecnología, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, Sinaloa, México

Email: *creyes@uas.uasnet.mx

Received July 11, 2012; revised August 20, 2012; accepted August 27, 2012

Keywords: Optimization; Amaranth Flour; Antioxidant Activity; Extrusion; Nutraceutical Beverage)

ABSTRACT

The objective of this research was to determine the best combination of extrusion process variables for the production of a high antioxidant extruded amaranth flour (EAF) suitable to elaborate a nutraceutical beverage. Extrusion operation conditions were obtained from a factorial combination of process variables: Extrusion temperature (ET, 70˚C - 130˚C) and screw speed (SS, 100 - 220 rpm). Response surface methodology was employed as optimization technique; both the numeric and graphical methods were applied to obtain maximum values for response variables [Antioxidant capacity (AoxC) and water solubility index (WSI)]. The best combination of extrusion process variables was: Extrusion temperature (ET) = 130˚C/Screw speed (SS) = 124 rpm. The raw amaranth flour (RAF) and optimized extruded amaranth flour (EAF) had an antioxidant activity of 3475 and 3903 µmol Trolox equivalents/100 g sample (dw), respectively. A 200 mL portion of the beverage prepared with 22 g of optimized EAF contained 3.16 g proteins, 1.09 g lipids, 17.39 g carbohydrates and 92 kcal. This portion covers 25.3% and 16.9% of the daily protein requirements for children 1-3 and 4 - 8 years old, respectively. A 200 mL portion of the beverage from optimized EAF contributes with 15.5% - 25.5% of the recommended daily intake for antioxidants, respectively. The nutraceutical beverage was evaluated with an average acceptability of 8.4 (level of satisfaction between “I like it” and “I like it extremely”) and could be used for health promotion and disease prevention as an alternative to beverages with low nutritional/nutraceutical value.

1. Introduction

Amaranth is an herbaceous annual plant belonging to the Amaranthaceae family, originally from the Tehuacán region (Mexico) and parts of South America. In pre-Colombian times amaranth seeds were such an essential product for the local diet that they became an integral part of pagan rituals and legends. With the decline of local cultures after Spanish colonization, amaranth fell into disuse or was even prohibited. Nonetheless, some small communities continued to cultivate it and enabled it to survive and spread around the world. At present amaranth is grown for commercial purposes in Mexico, South America, the United States, China, Poland and Austria. The genus Amaranthus includes about 60 species, but only 3 are considered good seed producers: A. hypochondriacus, A. cruentus and A. caudatus. Interest in its widespread consumption for human nutrition has grown in the two last decades due to favorable reports of amaranth nutritive value and health benefits. From a nutritional standpoint, the seeds of A. hypochondriacus L. (the main variety grown in Mexico) contain 15% - 20% of lysine-rich protein (3.2 - 6.4 g/100g protein compared to 2.8 - 3.0 g/100g protein for wheat), 58% - 66% of starch, 6% - 9% of raw fiber and 6% - 8% of highly unsaturated lipids. There are particularly high concentrations of calcium (250 mg/100g) and iron (15 mg/100 g)—10 and 4 times higher, respectively, than those found in wheat [1-5]. Polyphenolic compounds, such as phenolic acids and flavonoids, have been characterized in amaranth grains [6]. In addition to its promising nutritional qualities, amaranth grains are considered to be an important source of food for celiac patients, since they are gluten-free [7], diabetic [8], hypercholesterolemic subjects [9,10] and coronary heart disease and hypertension patients [11].

Amaranth has many uses: it is consumed in seed form, after cooking or as puffed cereal; it is ground and used as flour; it can be puffed and ground to obtain pregelatinized flour. In Mexico in particular, the seed is used as a puffed cereal and mixed with honey or molasses to produce a traditional sweet product (Alegría). Amaranth does not contain gluten and is therefore a raw material of interest for those suffering from celiac disease [12]. Furthermore, the popping process of the amaranth grain improves its rheological properties [13,14] as it happens by extrusion of other grains [15], because the similarity in processing.

Extrusion is a high temperature/short time technology that offer numerous advantages including versatility, high productivity, low operating costs, energy efficiency, high quality of resulting products and an improvement in digestibility and biological value of proteins [16]. Suspensions of flours precooked by extrusion are able to increase their viscosity rapidly, with a low tendency to form lumps, since starch granules have been modified showing high swelling capacity under both cold and hot conditions, which makes extruded flours highly recommended for preparation of instant food products [17] such as beverages.

In Mexico, instant flours from nixtamalized maize, as well as flours from raw, roasted, germinated, and fermented maize are used to elaborate beverages traditionally consumed as atole, pinole, tesgüino and pozol [18]. A dish known as “Atole” and “Pinole” is prepared with “toasted” amaranth seeds, or ground or whole grains [19]. Nutraceutical beverages represents one of the fastest annual growing markets worldwide, reaching a compound annual growth rate of 13.6% between 2002 and 2007 [20].

Response surface methodology (RSM) is a compendium of mathematical and statistical techniques that are useful for the modeling and analysis of problems in which a response variable of interest is influenced by several input variables. It is an effective method for establishing models evaluating the relative significance of variables and determining optimal conditions of desirable responses [21]. Most applications of RSM in process and product improvement involve more than one response variables. For optimize several responses have suggested the use of the optimization methods including conventional graphic method, improved graphic method, extended response surface procedure and desirability function [22]. The utility of RSM for extrusion cooking optimization has been previously demonstrated [23-25]. However, optimizing extrusion conditions for the production of instant amaranth flour with high antioxidant activity and/or nutraceutical properties have not been reported.

The objective of this research was to determine the best combination of extrusion process variables for the production of a high antioxidant extruded amaranth flour (EAF) suitable to elaborate a nutraceutical beverage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, hydrochloric acid, dichlorofluorescin diacetate, 2,2’-Azobis (2-amidinopropane), trifluoroacetic acid, catechina and gallic acid were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO). Sodium hydroxide, hexane, methanol, ethanol and ethyl acetate were purchased from DEQ (Mexico). All reagents used were of analytical grade.

2.2. Materials

The amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) grain was purchased at a local market in Temoac, Morelos, Mexico.

2.3. Proximate Composition

The following AOAC [26] methods were used to determine proximate composition: Drying at 105˚C for 24 h, for moisture (method 925.09B); incineration at 550˚C, for ashes (method 923.03); defatting in a Soxhlet apparatus with petroleum ether, for lipids (method 920.39 C); microKjeldahl for protein (Nx6.25) (method 960.52); and enzymatic-gravimetric methods for total dietary fiber (method 985.29). All determinations were made by triplicate.

2.4. Preparation of Extruded Amaranth Flours

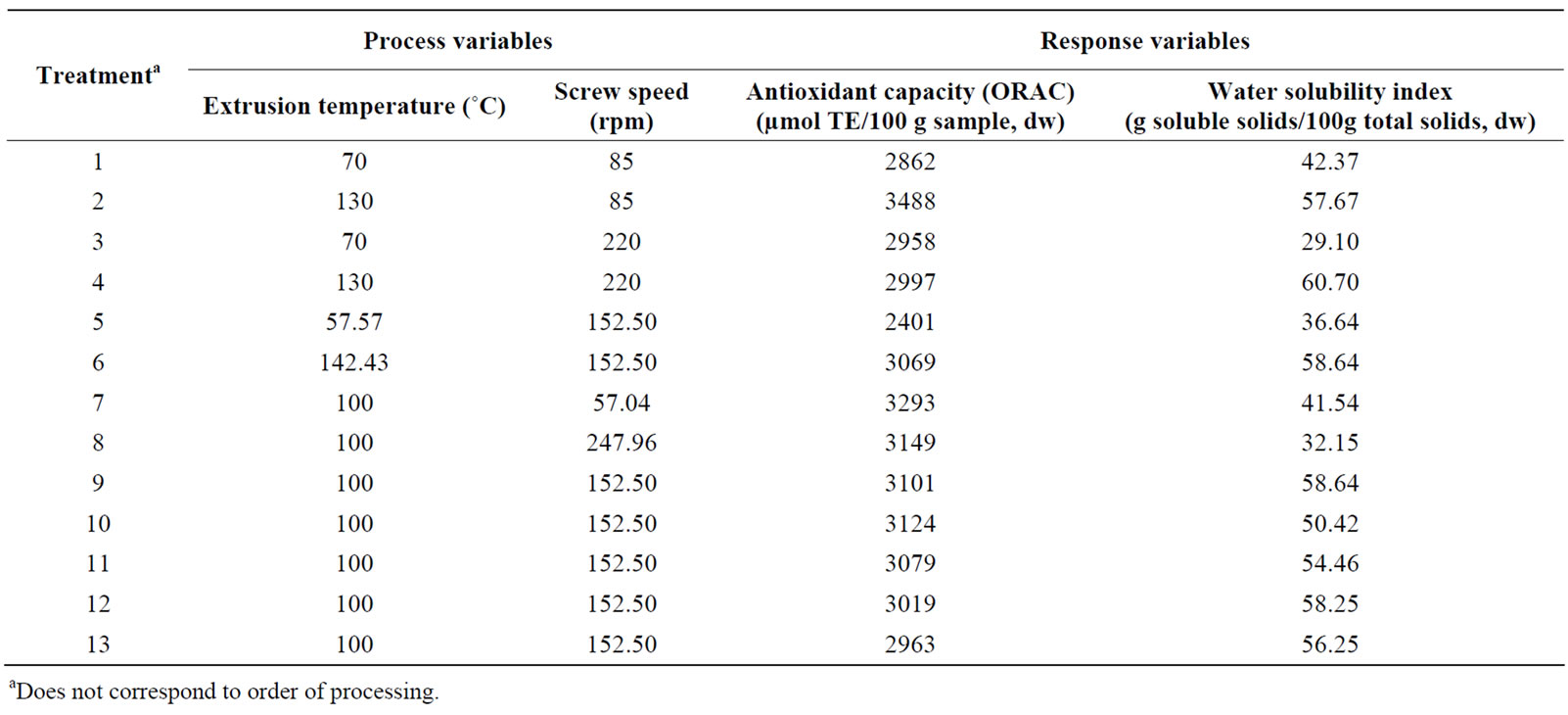

The extruded amaranth flours were obtained according to procedure recommended by Vargas-Lopez [27] and Queiroz et al. [28]. The amaranth grains (1 kg lots) were mixed with lime [0.21 Ca(OH)2/100g amaranth] and conditioned with purified water to reach a moisture content of 28%. Each lot was packed in a polyethylene bag and stored at 4˚C for 8 h. Before extrusion, the grits were tempered at 25˚C for 4 h. A single screw laboratory extruder Model 20 DN (CW Brabender Instruments, Inc., NJ, USA) with a 19 mm screw-diameter; length-to-diameter 20:1; nominal compression ratio 2:1; and die opening of 3 mm was used. The inner barrel was grooved to ensure zero slip at the wall. The temperature in the barrel was the same for the three zones and the end zone was cooled by air. A third zone, at the die barrel, was also electrically heated but not cooled by air. The feed rate was 30 rpm. ET was defined as temperature at the die end of the barrel. Extrusion operation conditions were obtained from a factorial combination of independent process variables: Extrusion temperature (ET, 70˚C - 130˚C) and screw speed (SS, 100 - 220 rpm). Table 1 presents different combinations of ET and SS used for producing extruded amaranth flours. After extrusion the extrudates were cooled, equilibrated at environmental conditions (25˚C, RH = 65%), milled (UD Cyclone Sample Mill, UD Corp, Boulder, CO, USA) to pass through an 80-US mesh (0.180 mm) screen, packed in plastic bags, and stored at 4˚C. The resulting extruded amaranth flours were analyzed for antioxidant capacity (AoxC), and water solubility index (WSI).

2.5. Antioxidant Capacity (AoxC)

Free phytochemicals in amaranth samples were extracted as previously reported by Dewanto et al. [29] with minor changes. A dry ground of 0.5 g was mixed with 10 mL chilled ethanol-water (80:20, v/v) for 10 min in a shaker at 50 rpm. The blends were centrifuged (3000 xg, 10 min) (Sorvall RC5C, Sorvall Instruments, Dupont, Wilmington, DE, USA) in order to recover the supernatant. The extracts were concentrated to 2 mL at 45˚C using a vacuum evaporator (Savant SC250 DDA Speed Vac Plus Centrifugal, Holbrook, NY, USA) and stored at −20˚C.

Bound phytochemicals in amaranth samples were extracted according to the method recommended by Adom & Liu [30] and Adom et al. [31]. After extraction of free phytochemicals, the pellet was suspended in 10 mL of 2M NaOH at room temperature and nitrogen was flushed to displace air present in the tube headspace before digestion. The samples were hydrolyzed at 95˚C and 25˚C in a shaking water bath oscillating at 60 rpm for 30 and 60 min, respectively. The hydrolyzed was neutralized with an appropriate amount of HCl before removing lipids with hexane. The final solution was extracted five times with 10 mL ethyl acetate and the pool was evaporated to dryness. Bound phytochemicals were reconstituted in 2 mL of 50% methanol and stored at −20˚C until use.

Free and bound hydrophilic antioxidant capacities were determined using the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay; extracts were evaluated against Trolox as standard, with fluorescein as probe as described Out et al. [32]. Peroxyl radicals were generated by 2,2’-azobis (2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride, and fluorescent loss was monitored in a Synergy microplate reader (Dynergy TM HT Multidetection, BioTek, Inc, Winoosgki, VT, USA). The absorbance of excitation and emission was set at 485 and 538 nm, respectively. The antioxidant capacities were expressed as micromoles of Trolox equivalents (TE) per 100 g of dry weight sample.

2.6. Total Phenolic Content

The phenolic content of free and bound extract ground samples was determined using the colorimetric method described by Singleton et al. [33]. Briefly, 20 µL of appropiate dilutions of extracts were oxidized with 180 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. After 20 min, absorbance of the resulting blue color was measured at 750 nm using a Microplate Reader (SynergyTM HT Multi-Detection, BioTek Inc, Winooski, VT, USA). A calibration curve was prepared using gallic acid as standard and total phenolics were expressed as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE)/100 g sample (dw).

Table 1. Combination of extrusion process variables used to produce extruded amaranth flours and experimental results for response variables (AoxC, WSI).

2.7. Water Solubility Index (WSI)

The WSI was assessed as described by Anderson et al. [34]. Each flour sample (2.5 g) was suspended in 30 mL of distilled water in a tared 60 mL centrifuge tube. The slurry was shaken with a glass rod for 1 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 3000 xg and 25˚C for 10 min. The supernatant was poured carefully into a tared evaporating dish. The WSI, expressed as g of solids/100 g of original solids (2.5 g), was calculated from the weight of dry solids recovered by evaporating the supernatant overnight at 110˚C.

2.8. RSM Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis for Extrusion Process

Response surface methodology (RSM) was applied to determine the optimum conditions of process variables for the manufacture of extruded amaranth flour with high antioxidant capacity (AoxC) and water solubility index (WSI) suitable to elaborate a nutraceutical beverage. Data from a previous report [23] and preliminary trials were taken into account to select the number and range of process variables in the experimental design. The process variables considered in this studies were extrusion temperature (X1 = ET, 70˚C - 130˚C), and screw speed (X2 = SS, 100 - 200 rpm), while the dependent response variables chosen were AoxC and WSI. A Central Composite Rotatable Design (CCRD) including 13 experiments formed by 5 central points and 4 (λ = 1.414) axial points to 22 full factorial design. Coded values corresponding to actual values of each variable and CCRD are shown in Table 1. Individual experiments were carried out in random order. The quadratic polynomial regression model was assumed for predicting (Y) response variables. Models of the following form were developed to describe the two response (Y) surfaces:

(1)

(1)

where, Y is the value of the considered experimental predicted response variable (AoxC, or WSI), X1 and X2 are the values of ET and SS, respectively, β0 is the constant value, β1 and β2 are linear coefficients, β12 is the interacttion coefficient, β11 and β22 are quadratic coefficients. Applying the stepwise regression procedure, non-significant terms (p ≤ 0.05) were deleted from the second order polynomial and a new polynomial was recalculated to obtain a predictive model for each variable [21,35]. All statistical analyses were performed using Design Expert software Ver. 7.0.0. [36].

2.9. Optimization of Extrusion Process

During the optimization of food processes, usually several response variables describing the quality characteristics and performance measures of the systems are to be optimized. Some of these variables are to be maximized and some are to be minimized. In many cases, these responses are competing, i.e. improving one response may have an opposite effect on another one, which further complicates the situation [37]. Several approaches have been used to tackle this problem. One of the most common is the conventional graphical method that superimposes the contour diagrams of the different response variables, while a second approach solving the problem of multiple responses uses a desirability function that combines all the responses into one measurement.

The conventional graphical method (CGM) is a relatively straightforward approach for optimizing several responses and it works well when there are only a few process variables. CGM was used as optimization technique to obtain maximum AoxC and WSI. Predictive models were used to represent graphically the system. Contour plots for each of the response variables were used applying superimposed surface methodology, to obtain a contour plot for observation and selection the zone of optimization of ET and SS for the production of optimized extruded amaranth flour. To perform this operation the Design Expert software version 7.0.0. was employed [36].

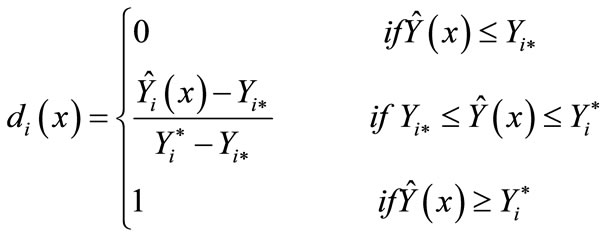

The desirability method described by De la Vara and Domínguez [38] was applied to find the best combination of extrusion process variables [extrusion temperature (ET)/ screw speed (SS)] that will result in a extruded amaranth flour with optimum values for the two dependent variables (AoxC, WSI). The two fitted models can be evaluated at any point X = (X1, X2) of the experimental zone and as a result two values were predicted for each model, namely Ŷ1(X) and Ŷ2(X). Then each Ŷi(X) is transformed into a value di (X), which falls in the range (0, 1) and measures the desirability degree of the response in reference to the optimum value intended to be reached. In this research, we wanted all response variables to be as high as possible. Thus, the transformation is:

(2)

(2)

where: di(X) = Value of the desirability of the ith response variable, Ŷi (X) = Estimated response variable,  = Maximum acceptable value of the ith response variable,

= Maximum acceptable value of the ith response variable,  = Minimum acceptable value of the ith response variable.

= Minimum acceptable value of the ith response variable.

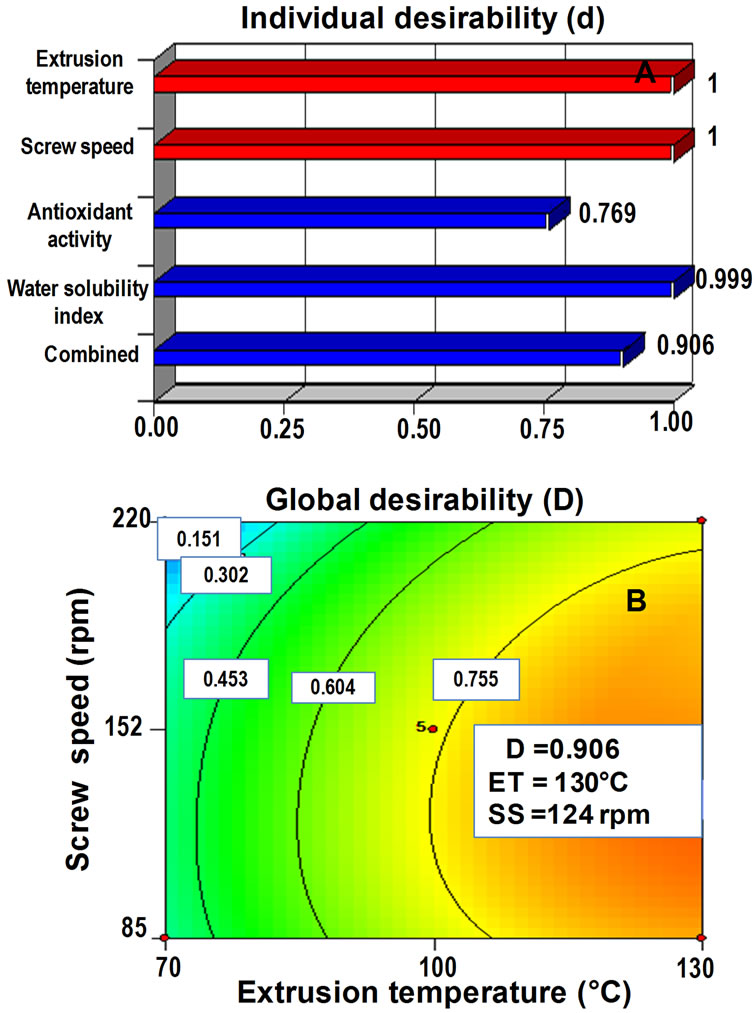

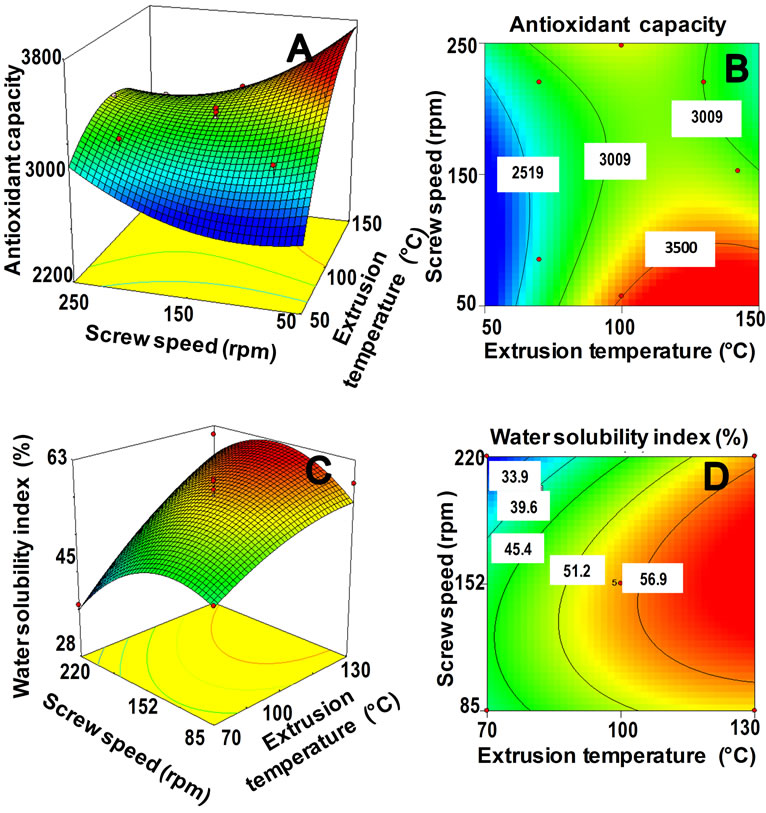

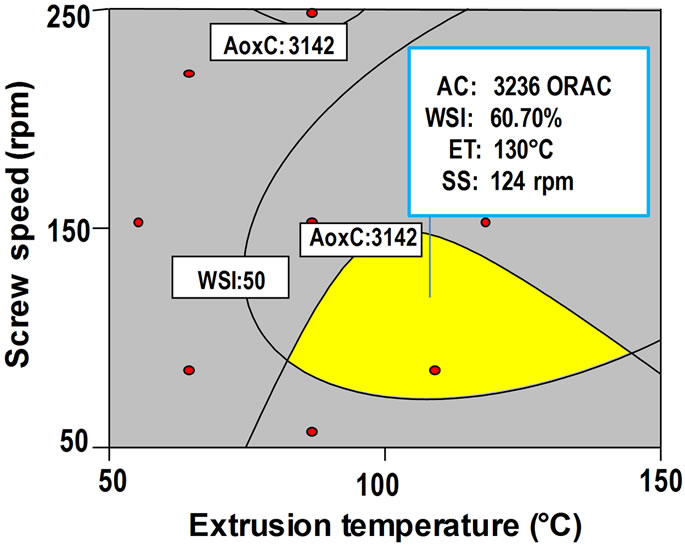

Once the two individual desirabilities were calculatedthe next step was to obtain the global desirability for the two response variables, using the mathematical function of transformation D = (d1d2)1/2, where the ideal optimum value is D = 1; an acceptable value for D can be between 0.6 and 0.8 (0.6 < D < 0.8). This acceptable value was found by using the Design Expert program version 7.0.0 [36]. The AoxC and WSI predictive models (Table 2) were used to obtain individual desirabilities (Figure 1A); which were employed to calculate a global desirability (D) (Figure 1B) for observation and selection of superior (optimum) combination of ET and SS for producing optimized extruded amaranth flour with high antioxidant capacity (AoxC) and water solubility index (WSI).

2.10. Beverage Preparation

Optimized extruded amaranth flour was used to prepare a nutraceutical beverage: Extruded amaranth flour (110 g) was added with fructose (13 g), powder cinnamon (3 g), powder vanillin (7 g) into purified water (1 L); the suspension was stirred in a domestic shaker (medium velocity), refrigerated (8˚C - 10˚C) and sensory evaluated for acceptability (A). All determinations were made by triplicate.

2.11. Sensory Evaluation

The nutraceutical beverage prepared with optimized extruded amaranth flour was made and evaluated the same day. The beverage was evaluated after 30 min of preparation, at room temperature. Sensory evaluation of the beverage was done using a panel of 80 judges (semitrained panellists). The judges were seated in individual

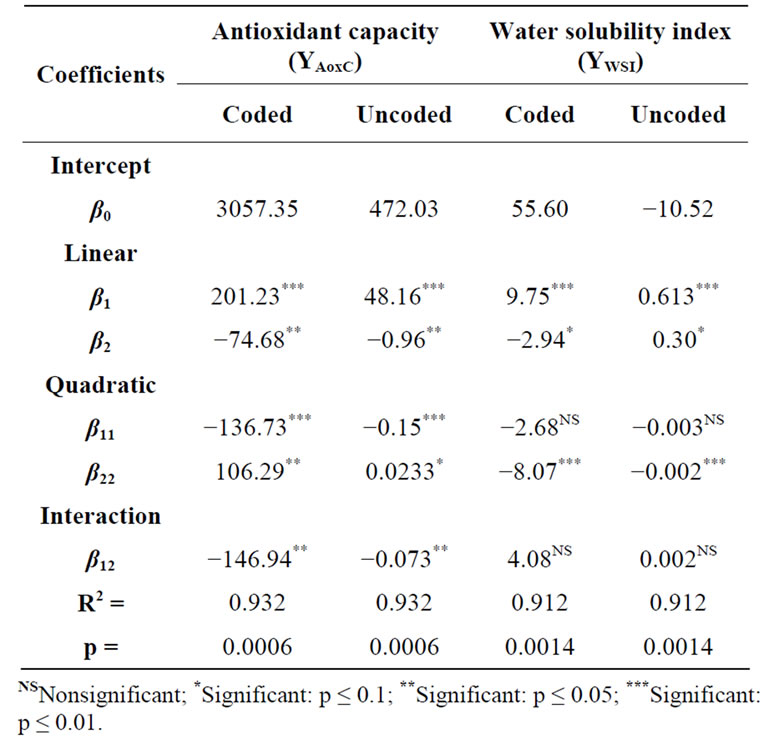

Table 2. Regression coefficients and analyses of variance of the second order polynomial models showing the relationships among response variables (Yk) and process variables (X).

Figure 1. (A) Individual desirability (di) for response variables (antioxidant capacity/water solubility index) and (B) global desirability (D = 0.906) for the optimized extruded amaranth flour for preparing a nutraceutical beverage.

booths in a laboratory with controlled temperature (25˚C) and humidity (50% - 60%), and day-light fluorescent lights. Samples were evaluated for acceptability using a hedonic scale of 9 points, where 9 means like extremely, and 1 means dislike extremely [39].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Predictive Model for Response Variables

Two predictive models were obtained as a result of fitting the second order polynomial of Equation (1) to experimental data of the effects of different combinations of extrusion process variables on the two response functions (AoxC and WSI) shown in Table 1. These predicttive models were tested for adequacy and fitness by analyses of variance (ANOVA, Table 2). According to [40], a good predictive model should have an adjusted R2 (coefficient of determination) ≥ 0.80, a significance level of p < 0.05, coefficients of variance (CV) values ≤ 10%, and lack of fit test > 0.1; all these parameters could be used to decide the satisfaction of the modeling. The AoxC of the extruded amaranth flours (EAF) varied from 2401 to 3488 µmol Trolox equivalents (TE)/100 g sample, dw (Table 1).

Analysis of variance showed that AoxC was significantly dependent on linear terms of extrusion temperature [ET, p < 0.01], and screw speed [SS, p < 0.05)], quadratic terms of ET and SS [(ET)2, p < 0.01; (SS)2, p < 0.05], and ET-SS interaction [ET-SS, p < 0.05]. Predictive models for the AoxC of EAF were:

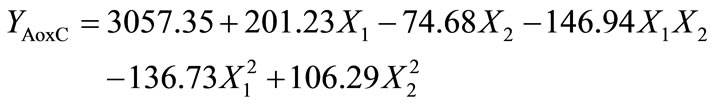

Using coded variables:

Using original variables:

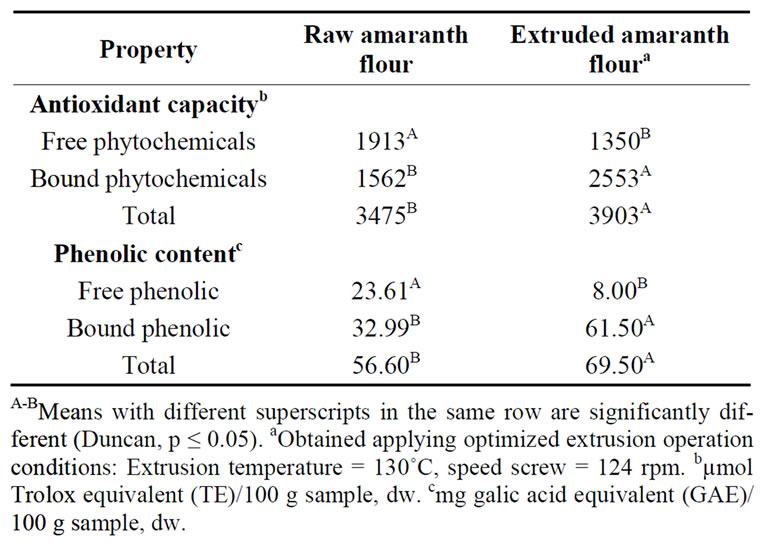

The predictive model explained 93.16% of the total variation (p < 0.05) in AoxC values (Table 2), and the lack of fit was not significant (p > 0.05). Furthermore, the relative dispersion of the experimental points from the predictions of the models (CV) was found to be 2.81%. These values indicated that the experimental model was adequate and reproducible. The raw amaranth flour had an AoxC of 3475 µmol TE/100g sample, dw (Table 3). Maximum values of AoxC were observed at ET = 100˚C - 142˚C, SS = 58 - 100 rpm (Figures 2A and B). Queiroz et al. [28] studied the effect of the extrusion process on antioxidant capacity of amaranth; they applied a combination of ET = 90˚C, SS = 404 rpm and did not observe changes in AoxC of extruded amaranth flour when compared with raw amaranth flour.

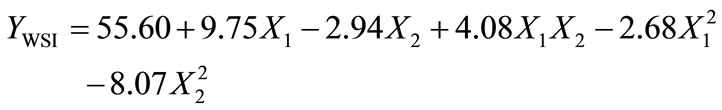

WSI is often used as an indicator of the degradation of molecular components. The WSI of the extruded amaranth flours varied from 29.10 to 60.70 g solids/100 g original solids (Table 1). Analysis of variance showed that WSI was significantly dependent on linear terms of extrusion temperature [ET, p < 0.05], and screw speed [SS, p< 0.05], and quadratic term of SS [(SS)2, p < 0.01]. Predictive models for the WSI of EAF were:

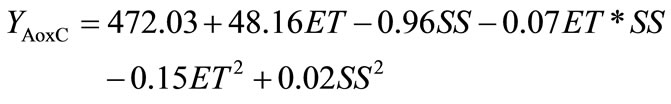

Table 3. Antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content in raw and optimized extruded amaranth flours.

Figure 2. Response surface and contour plots for the effect of extrusion temperature (˚C) and screw speed (rpm) on antioxidant capacity (A, B) and water solubility index (C,D) of extruded flours from amaranth grain.

Using original variables:

ANOVA for the model of WSI as fitted (Table 2) shows high significance (p < 0.01) and non-significant lack of fit (p > 0.05). The response regression model explained 91.2% of the total variability in WSI of the extruded amaranth flours. Additionally, the CV was 8.85%. Based on this analysis, the selected model represented adequately the data for WSI. Maximum values of WSI were observed at ET = 110˚C - 142˚C, SS = 120 - 180 rpm (Figures 2C and D). The increase WSI found in extruded products can be related to the lower molecular weight, which separated quite easily from each other when the processing conditions are more severe [41].

3.2. Optimization

Numerical method (desirability): Predictive models of each one of the response variables were employed to obtain individual desirabilities (Figure 1A) which were utilized for calculating a global desirability (D) (Figure 1B). The common maximum values for the two response variables were obtained at a D = 0.906, as a result of the best combination of extrusion process variables for the production of extruded amaranth flour: ET = 130˚C, SS = 124 rpm. The D value obtained was higher than the values that considered to be acceptable (0.6 < D < 0.8) according to De la Vara & Domínguez [38].

Graphical method: Figures 2B and D present the effect of extrusion temperature (ET) and screw speed (SS) on antioxidant capacity (AoxC) and water solubility index (WSI) of extruded amaranth flours, respectively. Superposition of these contour plots was carried out to obtain a new contour plot (Figure 3) which was utilized for observation and selection of the best combination of extrusion process variables for producing optimized amaranth flour with high AoxC and WSI, suitable to elaborate a nutraceutical beverage. Central point of the optimization region in Figure 3 correspond to a combination process variables of ET = 130˚C, SS = 124 rpm.

3.3. Antioxidant Capacity (AoxC) and Total Phenolic Content (TPC) of the Optimized Extruded Amaranth Flour

Table 3 shows the total hydrophilic antioxidant capacity (sum of antioxidant capacities of free and bound phytochemicals), or ORAC values, and total phenolic content (TPC, calculated as the sum of free and bound phenolic) of raw and optimized extruded amaranth flours.

Processing of the whole raw amaranth grains using extrusion cooking increased (p < 0.05) the total ORAC value and the TPC of the optimized extruded amaranth flour when compared with the raw flour [3903 vs 3475 µmol Trolox equivalent (TE)/100 g sample (dw), and 69.50 vs 56.60 mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/100 g sample, dw, respectively] (Table 3). It was also observed that the ORAC value of free phytochemicals significantly decreased (p < 0.05) and ORAC value of bound phytochemicals increased (p < 0.05) in optimized

Figure 3. Region of the best combination of process variables (extrusion temperature/screw speed) for producing of optimized extruded amaranth flour with high antioxidant capacity and water solubility index.

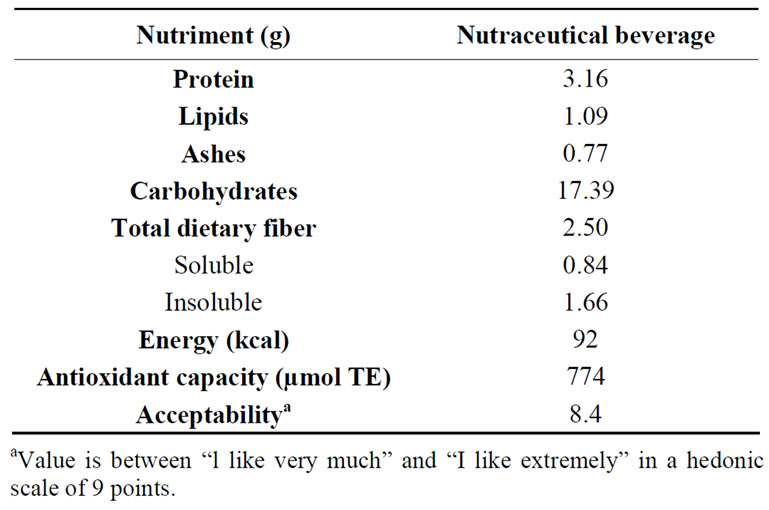

Table 4. Nutrimental content, antioxidant capacity and acceptability of a 200 mL portion of the nutraceutical beverage from optimized extruded amaranth flour.

extruded amaranth flour (Table 3). This behavior could be attributed to 1) Prevention of enzymatic oxidation and; 2) Darker colors of the extruded optimized mixture indicating formation of Maillard reaction products having antioxidant properties [42]. Our results show that the bound phytochemicals were the primary contributors (65.41%) to ORAC value and that the most of the phenolic (88.5%) in optimized amaranth flour occurred in the bound or attached to cell wall form (Table 3). Bioactive phytochemicals exist in free, soluble-conjugated, and bound forms; bound phytochemicals, mostly in cell wall materials, are difficult to digest in the upper gastrointestine and may be digested by bacteria in the colon to provide health benefits and reduce the risk of colon cancer [30,43].

The ORAC method is usually employed to estimate antioxidant activity of foods and to evaluate in vivo responses to dietary antioxidant manipulation. The ORAC is the only method so far that combines both inhibition time and degree of inhibition into a single quantity [44]. The United States Department of Agriculture, and the food and nutraceutical industries have accepted the method to the point that some manufactures now include ORAC values on product labels [45-47].

3.4. Nutrimental Content, Antioxidant Capacity and Acceptability of the Nutraceutical Beverage

Raw and optimized extruded amaranth flours had similar (p > 0.05) protein content (16.60% - 15.96%, dw) (data not show). Other researchers [48,49] have reported similar protein content for extruded amaranth flour. The raw amaranth flour showed the highest lipid content (7.86%, dw) (data not show); these results are in agreement with those reported by other authors [48-50]. The amaranth grains contain high starch content (60% - 70%) which is able to create complexes with lipids during extrusion processes. The total dietary fiber (TDF) contents of raw and optimized extruded amaranth flours were 14.62 and 13.91%, dw, respectively (data not show). ReynosoCamacho et al. [51] observed that the pattern of reduced colon cancer in Sprage-Dawley rats was influenced by the presence of dietary fiber; extruded amaranth flour by the TDF content could be considered as functional foods. The extruded amaranth flour had higher (p < 0.05) ashes content than raw amaranth flour (3.84% vs 3.17%, dw) (data not show); this behavior is related with the addition of lime during extrusion processes.

The formulation of a 200 mL portion of the beverage prepared from optimized extruded amaranth flour was based on those of traditional beverages widely consumed in Mexico, which are produced from different grain flours (for example, rice, barley), as well as sensorial tests to define the proper amounts for each ingredient (data not shown). The Mexican norm NMX-F-439-1983 for foods and non-alcoholic beverages was also considered. This norm defines a nutritious beverage when it contains at least 1.5% protein or protein hidrolyzates with a quality equivalent to that of Casein; it also establishes that the beverage must contain 10% to 25% of the main ingredient used to prepare it; these beverages can also contain up to 2% ethanol, edulcorants, flavouring agents, carbon dioxide, juices, fruit pulp, vegetables or legumes and other additives authorized by the Health and Assistance Secretary of Mexico. The formulations used in this research contained 11% of the extruded amaranth flours and 1.58% proteins of good quality. Besides, these beverages contained fructose to satisfy the recommendations of the Health and Assistance Secretary of Mexico, regarding the fact that a 200 mL portion of a beverage (food) must contain no more than 100 kcal.

The 200 mL portion of the nutraceutical beverage prepared with 22 g of optimized extruded amaranth flour contained 3.16 g proteins, 1.09 g lipids, 17.39 g carbohydrates and 92 kcal (Table 4). This portion covers 25.13% and 16.86% of the daily protein requirements for children 1 - 3 and 4 - 8 years old, respectively. The nutraceutical beverages (200 mL) from optimized extruded amaranth flour showed a total antioxidant capacity of 774 µmol TE (Table 4); which contributes with 15.5% - 25.5% of the recommended (3000 to 5000 µmol TE) daily intake for antioxidants [47]. The semi-trained panelists assigned an average value of 8.4 in acceptability to the beverage from optimized extruded amaranth flour (level of satisfaction between “I like it” and “I like it extremely”) (Table 4). It is expected that this acceptability allows an adequate consumption to provide health benefits.

4. Conclusion

Extrusion of amaranth grains produces extruded flour with acceptable good nutritional and antioxidant properties. Response surface methodology is a useful tool for optimization of processes involving several processing conditions and several response variables. The best combination of extrusion process variables for the production of extruded amaranth flour to elaborate a beverage with high antioxidant capacity and acceptability were: Extrusion temperature = 130˚C, Screw speed = 124 rpm. The optimized extruded amaranth flour had an antioxidant capacity of 3903 µmol Trolox equivalents/100 g sample (dw). A 200 mL portion of the beverage from optimized extruded amaranth flour contributes with 15.5% - 25.5% of the recommended daily intake for antioxidants. The nutraceutical beverage was evaluated with an average acceptability of 8.4 (level of satisfaction between “I like it” and “I like it extremely”). The high nutritional, antioxidant and sensory value of the amaranth beverage can be attributed at least partially to the application of the optimum extrusion processing conditions. The nutraceutical beverage could be used for health promotion and disease prevention as an alternative to beverages with low nutritional/nutraceutical value.

5. Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Fundación Produce Sinaloa (Convocatoria 2011) and PROFAPI-UAS (Programa de Fortalecimiento y Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, México) 2012. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- B. Salcedo-Chávez, J. A. Osuna-Castro, F. Guevara-Lara, J. Domínguez-Domínguez and O. Paredes-López, “Optimization of the Isoelectric Precipitation Method to Obtain Protein Isolates from Amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus) Seeds,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 50, No. 22, 2002, pp. 6515-6520. doi:10.1021/jf020522t

- M. Bodroza-Solarov, B. Filipcev, Z. Kevresan, A. Mandic and O. Simurina, “Quality of Bread Supplemented with Popped Amaranthus cruentus Grain,” Journal of Food Processing Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2007, pp. 602- 618. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4530.2007.00177.x

- B. E. Berganza, A. W. Morán, G. Rodríguez, N. M. Coto, M. Santamaría and R. Bressani, “Effect of Variety and Location on the Total Fat, Fatty Acids and Squalene Content of Amaranth,” Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, Vol. 58, No. 3, 2003, pp. 1-6. doi:10.1023/B:QUAL.0000041143.24454.0a

- B. Pedersen, K. E. B. Knudsen and B. O. Eggum, “The Nutritional Value of Amaranth Grain (Amaranthus caudatus) Energy and Fibre of Raw and Processed Grain,” Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1990, pp. 61-71. doi:10.1007/BF02193780

- P. Whittaker and M. O. Ologunde, “Study of Iron BioaVailability in a Native Nigerian Grain Amaranth Cereal for Young Children, Using a Rat Model,” Cereal Chemistry, Vol. 67, No. 5, 1990, pp. 505-508.

- H. A. Pedersen, “Synthesis and Quantitation of Six Phenolic Amides in Amaranthus spp,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 58, No. 10, 2010, pp. 6306-6311. doi:10.1021/jf100002v

- L. Alvarez-Jubete, E. K. Arendt and E. Gallagher, “Nutritive Value of Pseudocereals and Their Increasing Use as Functional Gluten Free Ingredients,” International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition, Vol. 60, No. 4, 2009, pp. 240-257. doi:10.1080/09637480902950597

- A. Chaturvedi, G. Sarojini, N. Nirmalammay and D. Satyanarayana, “Glycemic Index of Grain Amaranth, Wheat and Rice in NIDDM Subjects,” Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, Vol. 50, No. 2, 1997, pp. 171-178. doi:10.1007/BF02436036

- J. Burri, F. Dionisi, M. Allan and P. Lambelet, “Choles-Terol-Lowering Properties of Amaranth Grain and Oil in Hamsters,” International Journal of Vitamins and Nutrition Research, Vol. 73, 2003, pp. 39-47. doi:10.1024/0300-9831.73.1.39

- D. H. Shin, H. J. Heo, Y. J. Lee and H. K. Kim, “Amaranth Squalene Reduces Serum and Liver Lipid Levels in Rats Fed a Cholesterol Diet,” British Biomedicine Science, Vol. 61, No. 1, 2004, pp. 11-14.

- D. M. Martirosyan, L. D. Miroshnichenko, S. N. Kulakova, A. V. Pogojeva and V. I. Zoloedov, “Amaranth Oil Application for Coronary Heart Disease and Hypertension,” Lipids in Health and Disease, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2007, pp. 1-12. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-6-1

- H. Gambus, F. Gambus, D. Pastuszka, P. Wrona, R. Ziobro, R. Sabat, B. Mickowska, A. Nowotna and M. Sikora, “Quality of Gluten Free Supplemented Cakes and Biscuits,” International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition, Vol. 60, No. 4, 2009, pp. 31-50. doi:10.1080/09637480802375523

- M. Markowski, A. Ratajski, H. Konopko, P. Zapotoczny and K. Majewska, “Rheological Behavior of Hot-AirPuffed Amaranth Seeds,” International Journal of Food Properties, Vol. 9, 2006, pp. 195-203. doi:10.1080/10942910600596076

- P. Zapotoczny, M. Markowski, K. Majewska, A. Ratajski and H. Konopko, “Effect of Temperature on the Physical, Functional, and Mechanical Characteristics of Hot-AirPuffed Amaranth Seeds,” Journal of Food Engineering, Vol. 76, No. 4, 2006, pp. 469-476. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.05.045

- H. D. Sánchez, R. J. González, C. A. Osella, R. L. Torres and M. A. G. de la Torre, “Elaboración de Pan Sin Gluten Con Harinas de Arroz Extrudidas,” Ciencia y Tecnología Alimentaria, Vol. 6, 2008, pp. 109-116.

- R. Gutiérrez-Dorado, A. E. Ayala-Rodríguez, J. Mi-lánCarrillo, J. López-Cervantes, J. A. Garzón-Tiznado, J. A. López-Valenzuela, O. Paredes-López and C. Re-yesMoreno, “Technological and Nutritional Properties of Flours and Tortillas from Nixtamalized and Extruded Quality Protein Maize (Zea mays L.),” Cereal Chemistry, Vol. 85, No. 6, 2008, pp. 808-816. doi:10.1094/CCHEM-85-6-0808

- T. Vasanthan, J. Yeung and R. Hoover, “Dextrinization of Starch in Barley Flours with Thermostable Alpha-Amylase by Extrusion Cooking,” Starch/Stârke, Vol. 53, No. 12, 2001, pp. 616-622. doi:10.1002/1521-379X(200112)53:12<616::AID-STAR616>3.0.CO;2-M

- O. Paredes-López, F. Guevara-Lara and L. A. Bello-Pérez, “Los Alimentos Mágicos de las Culturas Indígenas Mesoamericanas,” Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, 2006, pp. 32-34, 81-88.

- E. L. Contreras, J. O. Jaimez, J. C. R. Soto, A. O. Castañeda and J. M. Añorve, “Aumento del Contenido Proteico de una Bebida a Base de Amaranto (Amaranthus Hypochon-Driacus),” Revista Chilena de Nutrición, Vol. 38, No. 3, 2011, pp. 322-330. doi:10.4067/S0717-75182011000300008

- M. A. Heckman, K. Sherry and E. G. de Mejía, “Energy Drinks: An Assessment of Their Market Size, Consumer Demographics, Ingredient Profile, Funcionality, and Regulations in the United States,” Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2010, pp. 303-331. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00111.x

- A. A. Khuri and J. A. Cornell, “Response Surfaces: Designs and Analyses,” Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, 1987, pp. 1-17, 254.

- J. Fichtali, F. R. Van De Voort and A. I. Khuri, “MulTiresponse Optimization of Acid Casein Production,” Journal of Food Process Engineering, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1990, pp. 247-258. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4530.1990.tb00053.x

- J. M. Vargas-Lopez, O. Paredes-Lopez and E. Espitia, “Evaluation of Lime Heat Treatment on Physicochemical Properties of Amaranth by Response Surface Methodology,” Cereal Chemistry, Vol. 67, No. 5, 1990, pp. 417- 421.

- J. Milán-Carrillo, R. Gutierrez-Dorado, J. X. K. Perales-Sánchez, E. O. Cuevas-Rodrıguez, B. Ramirez-Wong and C. Reyes-Moreno, “The Optimization of the Extrusion Process When Using Maize Flour with a Modified Amino Acid Profile for Making Tortillas,” International Journal of Food Science and Technology, Vol. 41, No. 7, 2006, pp. 727-736. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.00997.x

- J. Milán-Carrillo, C. Reyes-Moreno, I. L. Camacho-Hernandez and O. Rouzaud-Sandez, “Optimisation of Extrusion Process to Transform Hardened Chick-Peas (Cicer arietinum L.) into a Useful Product,” Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, Vol. 82, No. 14, 2002, pp. 1718-1728. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1242

- AOAC, “Official Methods of Analysis,” 16th Edition, Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington DC, 1999.

- J. M. Vargas-López, O. Paredes-López and B. Ramí-rezWong, “Physicochemical Properties of Extrusion-Cooked Amaranth under Alkaline Conditions,” Cereal Chemistry, Vol. 68, No. 6, 1991, pp. 610-613.

- Y. S. Queiroz, R. A. M. Soares, V. D. Capriles, E. A. F. S. Torres and J. A. G. Areas, “Efeito DO Processamento na Atividade Antioxidante DO Grão de Amaranto (Amaranthus cruentus L. BRS-Alegria),” Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición, Vol. 59, No. 4, 2009, pp. 419- 424.

- V. Dewanto, X. Wu and R. H. Liu, “Processed Sweet Corn Has Higher Antioxidant Activity,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 50, No. 17, 2002, pp. 4959-4964. doi:10.1021/jf0255937

- K. F. Adom and R. H. Liu, “Antioxidant Activity of Grains,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 50, No. 21, 2002, pp. 6182-6187. doi:10.1021/jf0205099

- K. K. Adom, M. E. Sorrells and R. H. Liu, “Phytochemical Profiles and Antioxidant Activity of Wheat Varieties,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 51, No. 26, 2003, pp. 7825-7834. doi:10.1021/jf030404l

- B. Ou, M. Hampsch-Woodill and R. L. Prior “Development and Validation of an Improved Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity Assay Using Fluorescein as the Fluo-Rescent Probe,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 49, No. 10, 2001, pp. 4619-4626. doi:10.1021/jf010586o

- V. L. Singleton, R. Orthofer and R. M. Lamuela-Raventos, “Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent,” Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 299, 1999, pp. 152-178. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1

- R. A. Anderson, H. F. Conway, V. F. Pfeifer and E. L. Griffin, “Gelatinizacion of Corn Grits by Rool and Extrusion Cooking,” Cereal Science Today, Vol. 14, No. 11, 1969, pp. 4-12.

- R. H. Myers, “Response Surfaces Methodology,” Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 1971, pp. 26-106.

- Design Expert, “Version 7.0.0. Stat-Ease,” Design Expert Inc., Minneapolis, 2005.

- M. Jahani, M. Alizadeh, M. Pirozifard and A. Qudsevali, “Optimization of Enzymatic Degumming Process for RBO Using Response Surface Methodology,” LWT— Food Science and Technology, Vol. 41, No. 10, 2008, pp. 1892-1898.

- S. R. De la Vara and D. J. Domínguez, “Métodos de Superficie De Respuesta; Un Estudio Comparativo,” Revista de Matemáticas Teoríay Aplicaciones, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2002, pp. 47-65.

- E. Larmond, “Laboratory Methods for Sensory Evaluation of Foods,” Department of Agriculture, Ottawa, Vol. 74, 1977.

- R. H. Myers and D. C. Montgomery, “Response Surface Methodology: Product and Process Optimization Using Designed Experiments,” 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2002.

- P. Colonna, J. Tayeb and C. Mercier, “Extrusion Cooking of Starch and Starchy Products,” In: C. Mercier, P. Linko and J. M. Harper, Eds., Extrusion Cooking, American Association of Cereal Chemists, St. Paul, 1989, pp. 247- 319.

- C. Fares and V. Menga, “Effects of Toasting on the Carbohydrate Profile and Antioxidant Properties of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Flour Added to Durum Wheat,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 131, No. 4, 2012, pp. 1140-1148. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.080

- R. H. Liu, “Whole Grain Phytochemicals and Health,” Journal of Cereal Science, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2007, pp. 207-219. doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2007.06.010

- G. H. Cao and R. L. Prior, “Measurement of Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity in Biological Samples,” Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 299, 1999, pp. 50-62. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99008-0

- G. Bank and A. Schauss, “Antioxidant Testing: An ORAC Update,” Nutraceuticals World, 2004. http://www.nutraceuticalsworld.com/march042.htm

- USDA, “Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) of Selected Foods,” United States Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, 2007, pp. 1-34.

- USDA, “Antioxidants and Health,” ACES Publications, Beltsville, 2010, p. 4.

- T. A. D. C. Ferreira and J. A. G. Areas, “Protein Biological Value of Extruded, Raw and Toasted Amaranth Grain,” Pesquisa Agropecuaria Tropical, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2004, pp. 53-59.

- R. N. Chávez-Jáuregui, M. E. M. Silvia and J. A. G. Areas, “Extrusion Cooking Process for Amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus),” Journal of Cereal Science, Vol. 65, No. 6, 2000, pp. 1009-1015.

- C. R. Tacora, M. G. Luna, P. R. Brao, H. J. Mayta, Y. M. Choque and Q. V. Ibañez. “Efecto de la PRESIÓN de Ex-pansion por Explosion Temperatura de Tostado en Algunas Características Funcionales Fisicoquímicas de Dos Variedades de Cañihua (Chenopodium pallidicaule Aellen),” Journal de Ciencia Tecnología Agraria, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2010, pp. 188-198.

- R. Reynoso-Camacho, M. C. Ríos-Ugalde, I. TorresPacheco, J. A. Acosta-Gallegos, A. C. Palo-mino-Salinas, M. Ramos-Gómez, E. González-Jasso and S. H. GuzmánMaldonado, “El Consumo de Frijol Común (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) su Efecto Sobre el Cáncer de Colon en Ratas Sprague-Dauley,” Agricultura Técnica de México, Vol. 33, No. 1, 2007, pp. 43-52.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.