Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

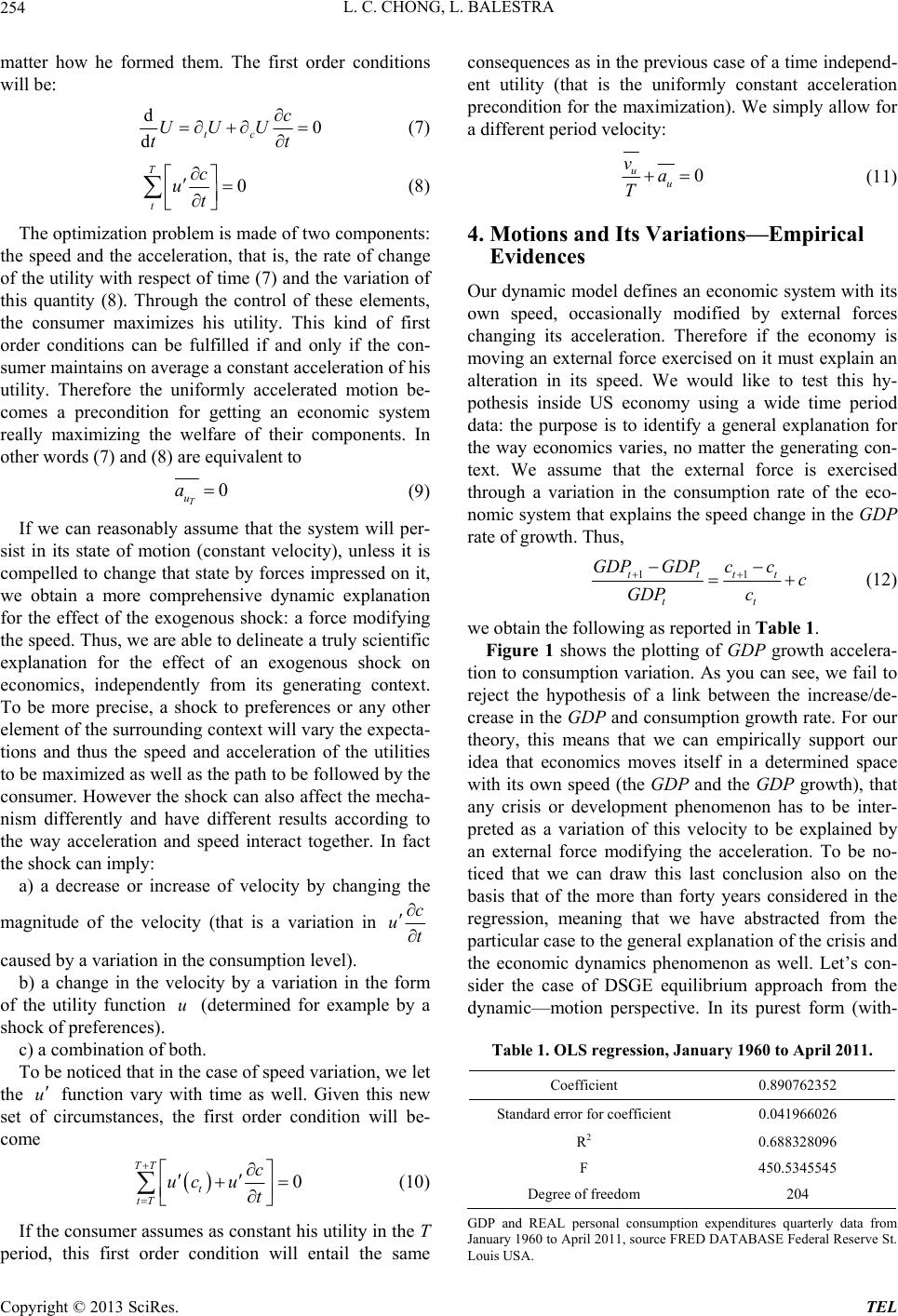

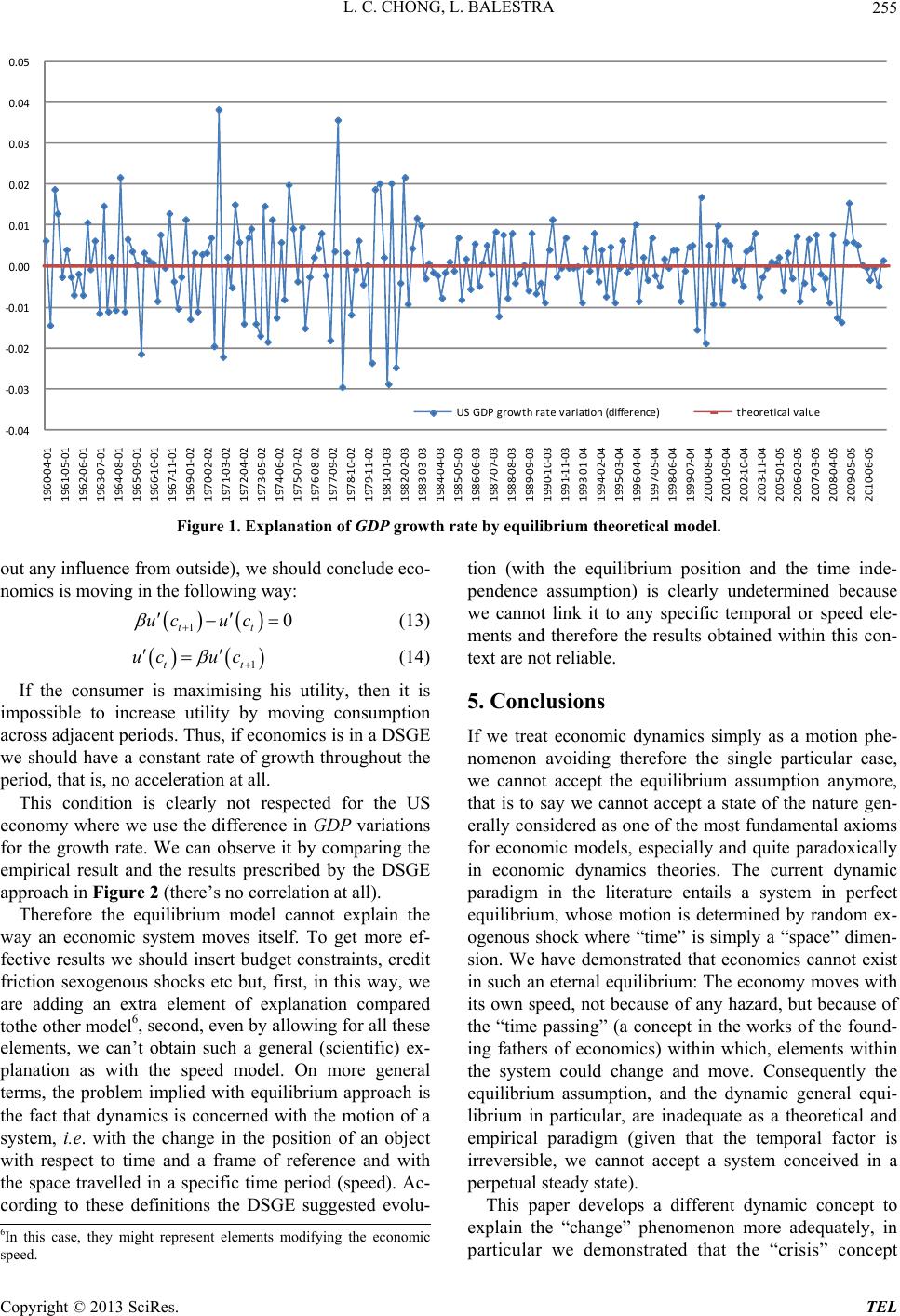

Theoretical Economics Letters, 2013, 3, 251-256 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/tel.2013.34042 Published Online August 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/tel) The Economic Motion Li Choy Chong, Luisella Balestra Asia Research Centre, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland Email: Li-Choy.Chong@unisg.ch Received June 6, 2013; revised July 6, 2013; accepted July 16, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Li Choy Chong, Luisella Balestra. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribu- tion License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT This paper investigates the way economics moves, in other words we study the characteristics of economic dynamics by itself that is by abstracting from the single generating context, whatever this might be. We would like to concentrate on the fundamental mechanism “moving” the economic system and determining its business cycle, its crisis, its develop- ment and so on. In this way we are offering an extremely new perspective about economic dynamics, as we do not con- sider its elements as separate but we hold them as part of a single phenomenon, the evolution of an economic system. We argue that by considering this point of view, economic dynamics cannot be determined by a system in eternal equi- librium only occasionally disturbed by some exogenous shock. We demonstrate that economics is evolving continu- ously and economic phenomena (such as economic crisis) have to be interpreted as a variation in its velocity. Keywords: Economic Dynamics; Equilibrium; Economic Fluctuations 1. Introduction—The Fundamental Problem The globalization phase of world economy and the new century seem increasingly characterized by a long string of financial/economic crises, whose characteristics, causes and implications have been extensively researched in the past and are still yet to be defined for the current one. Therefore the crisis phenomenon seems to be one of the defining marks for this period, leaving us with the need to understand its structure as well as the existence of possible remedies. Despite these practical evidences the economic crisis has been one of the most investigated and debated topics as well as one of the most controver- sial, together with its associated concept of economic cycles. For example, in his review of the academic in- quiry into the subject through the centuries (the debate is in fact one of the oldest), Meghad Desai [1] identifies at least 5 different positions in relation to the two topics, although the distinction might be sharper than that in the literature: 1) Cycles are natural, endemic, endogenous response to the capitalist system—Marx. 2) Cycles are signs of overindulgence in an otherwise healthy cycle free economy (cycle free system)—Hayek. 3) Cycles are healthy as they recharge the batteries of the economy—Schumpeter. 4) Cycles are pathological and need a drastic cure— Keynes. 5) Cycles are the result of random shocks on an other- wise stable system (the most common position today)— Walras/Keynesian ISLM model/Real business cycles. Through the years, the crisis/cyclical phenomenon has generally been considered deviation from an ideal cycle (crisis free situation), but the interpretation of such varia- tions has dramatically differed. The most relevant aspect of these divergent positions is the fact that, all these kinds of studies do not provide us with a sufficient under- standing of the phenomenon so that we may explain the different crisis and cycles arising from different contexts with the same theoretical framework. In [1], Desai wrote “Despite decades of theorizing we cannot say with any confidence that we have a theory that generates sus- tained (non-damp ed), endogenous (or if not endogenous with reliably regular exogenous shocks), transnational or global cycles linking financial and real variables, which has a credible empirical record. Like in the story of the blind men and the elephan t, each proponen t of a solution can point to one aspect and generalize from that. What we need is some theory that can encompass the varied experience of local damped or undamped cycles or glo- bal cycles, cycles of various lengths and amplitudes with financial and real variables properly articulated with systematic influences overlaid with stochastic shocks.” C opyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  L. C. CHONG, L. BALESTRA 252 In other words, current theories are unable to offer a scientific explanation about the fact that “economics changes” (and sometimes sodramatically as in these years), since all of them are too restricted by the limits determined by the particular situations they are trying to explain and therefore for them it’s impossible to give insights that we can better adopt in different contexts than the generating one. We think that the main problem is the fact that a more comprehensive perspective in eco- nomic theory is missing: all the economic dynamics phe- nomena, such as crisis, are considered as separated events and therefore we cannot get a “truly” scientific explana- tion for them as we are limited by each generating context. Aim of this paper is to overcome this problem; we want to explain the way economics moves by consider- ing each economic dynamics elements as particular ex- pressions of a more general phenomenon, that is the evolution of an economic system. In this way, we show first the impossibility of an equilibrium position and therefore of an ideal crisis free situation (=the eternal steady state), second we develop a new scientific para- digm based upon the speed concept, then, through the empirical observations about the US economy from 1960 to 2010, we subsequently show and prove that economic crisis as well as growth episodes can in effect be inter- preted as variations in the velocity of the system. Thus, no matter the originating cause of the particular situation (we analyse 50 years), a general explanation for eco- nomic dynamics is empirically tested and confirmed, being therefore able to move over from the limits implied by the usual exogenous shock scheme. It’s a very inno- vative work due to our approach: we treat economic dy- namics as a motion phenomenon by itself, therefore try- ing to abstract from any generating context and deriving from this some general (=scientific) insight about the evolution of an economic system. 2. Economic Dynamics as the Motion of an Economic System The fundamental element characterizing our approach to the problem is the fact that economic crisis, equilibrium, shocks, growth, cycles and the like, are all movements of a system [2,3]. In fact, we can always observe asystem, which could be defined as a configuration of variables within a specific space and at a specific point in time and such a correlated structure of variables specified and changing with the time element would provide a frame of reference to compare with, as it moves from one con- figuration to another and thereby expressing the fact that it is changing its position. A consequent aspect of interest would have us understand that if it’s moving, the system must be expressed per definition by the elements of time, space (s, the length of path travelled until time t) and speed1, the time derivative of s that is: d d s vt (1) Despite these general evidences, the traditional ap- proach about economic dynamics is quite paradoxically characterized by the lack of awareness about the fact that economic phenomena are in effect motions in a specific space. In fact the fundamental tool used for expressing economic motion has so far been the equilibrium that is the motionlessness of the economic system. Equilibrium represents a very common scientific paradigm for eco- nomictheory, since this state of nature is usually treated as the best solution to be achieved by economics and it offers the basis for three kinds of “movements”: Base—unit movement of the system defined by the achievement of a position of equilibrium(e.g. the sin- gle market or general market equilibrium, as the tran- sition to a different position in the temporal evolution for economics)2; motion obtained through the temporal repetition of an equilibrium position. It is determined by the repetition of a base unit movement (usually a goal equilibrium) over a (infinite) time horizon after having specified a law of transition for the system. We usually end up with a condition describing a path made by a fixed sequence of equilibrium position, which is supposed to remain unchanged for the time being (such as Euler condition); exogenous shocks. Together with the expected value operator, represents the uncertainty inside economics, making it impossible to predict outcomes. The ex- ogenous shock gives the impulse for the economic surrounding context to vary and its main effect is a displacement of the system’s path in the economic space or in its structure. In any case it has to be con- sidered as a temporally limited event that becomes eventually absorbed by the system through the defini- tion of new characteristics of the model (or for the path), that is supposed to remain again “eternally” un- altered thereafter, unless some other exogenous shock will come around another time. According to the definition of Fritz Machlup [4] equi- librium is a “constellation of selected interrelated vari- ables so adjusted to one another that no inherent ten- dency to change prevail in the model which they consti- tute”. As Chiang [5] pointed out, this explanation implies a relation among selected variables such that they are in a 1We can also consider acceleration 0 limt v t a . 2The maximization assumption also expresses this kind of motion (it’s a goal equilibrium) and in this perspective the comparative static analysis and the existence of rigidities in the relationship b etween variables have to be interpreted as the definition of different paths and outputs toward (or not toward) this state for the economic system. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  L. C. CHONG, L. BALESTRA 253 correlated state of rest with the surrounding context to- tally fixed (otherwise a change in some of them will be causing a change reaction and no more equilibrium at all). Moreover, equilibrium has the tendency to perpetuate itself uninterruptedly, barring any change in the external context. In other words, the crucial element characteriz- ing this position is the idea of economic equilibrium as a condition independent from the passage of time that be- comes therefore a mere space dimension. We disagree with this position. To prove it, consider the typical case [6] of a consumer maximizing its utility by eat- ing a cake uc t W: 1 1 s.t max T t t tt uc WW t c the economic system evolved until time T ‒ 1 according to this condition 1t uc uc t 11T (2) Then, after the exogenous shock at T, to this other con- dition 1T uc uc (3) If time past without affecting economics, that is if time was a mere space dimension, it would have been possible to find a unique integral expressing both conditions (2) and (3) which is clearly not the case. Economics is not changing “over time” but is evolving “with time”, this means that in an economic system something called No- vember 2, 1961 is not just a name but a proper element in relation with other elements. Therefore, time is a variable and not a mere space dimension and economics cannot be fixed in an eternal atemporal equilibrium position, only ocasionally disturbed by external shocks, as gener- ally conceived by economic theory until now. In effect if we consider dynamics in that way, we are misunder- standing its fundamental structure (the relation with time). Three very important consequences derive from the impossibility of the equilibrium position. First, we cannot assume stationarity and therefore we cannot use the usual dynamic programming techniques (such as dynamic op- timization) to maximise the economic system. All these methods are based upon the concept that economics is independent from time and remains fixed in the future as well in the past3. Thus, we cannot put every element that varies with time on a state vector and maximise a control variable to get the effective optimum for the economic system, it can’t be reached in such a way. There’s no perfect steady state toward which the eco- nomic system is tending and therefore we cannot think of an economic crisis as an external shock to a system other wise unperturbatedly still, since there’s no such perfect state of nature. Third consequence from the impossibility of economic equilibrium is about the nature of uncertainty. Whereas before uncertainty was the changing volatility for a proc- ess evolving over time, now uncertainty is part of the process itself determined by the fact that time is now an independent variable and not a space dimension inside the economic mechanism with no variance at all since there’s no expected value for a distribution to move around. Next paradigm will be devoted to develop both theo- retically and empirically these conclusions. 3. A New Dynamic Paradigm From the previous discussion, the main point is the fact that we cannot accept the idea of a system in an absolute steady state, randomly disturbed by stochastic variations and totally independent of the contemporary contextual conditions. The consumer will not maximise an “eternal” variable by itself but its time varying flow, i.e. he will maximise the speed of this variable. The consumer’s function will be 1 max , T t Uct (4) and , t Uctuc oct (5) The two parts of the composed function contain the elements of the utility function that varies with time or that remains unchanged: u(.) is the utility function (inde- pendent of time), whereas c(t) is the consumption func- tion considering the surrounding context and depending on time. Since economic dynamics is a motion pheno- menon we must apply (1) and the consumer’s fundamen- tal problem (4) therefore becomes max ,1 Ttt tt uc uc Uct Tt T (6) Time is now a variable interacting with other variable inside the economic mechanism not an independent space dimension anymore, implying that the consumer cannot know which variables will be effectively affecting him4 in the whole future nor maximise economics over the entire period, since the individual understands that things can change and he has to take count of it (we call them temporally rational expectations).What he can do is to have his own expectations about his utility over a time that cannot be infinite5 and act according to his belief, no 4He ignores also the magnitude of their impact. 5In our example, we suppose that the consumer is making his own p rediction about his utility function over a T period. 3See for example Kamien Schwarz [7] ppgg 14, 114. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  L. C. CHONG, L. BALESTRA 254 matter how he formed them. The first order conditions will be: d0 dtc c UUU tt (7) 0 T t c ut (8) The optimization problem is made of two components: the speed and the acceleration, that is, the rate of change of the utility with respect of time (7) and the variation of this quantity (8). Through the control of these elements, the consumer maximizes his utility. This kind of first order conditions can be fulfilled if and only if the con- sumer maintains on average a constant acceleration of his utility. Therefore the uniformly accelerated motion be- comes a precondition for getting an economic system really maximizing the welfare of their components. In other words (7) and (8) are equivalent to 0 T u a (9) If we can reasonably assume that the system will per- sist in its state of motion (constant velocity), unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed on it, we obtain a more comprehensive dynamic explanation for the effect of the exogenous shock: a force modifying the speed. Thus, we are able to delineate a truly scientific explanation for the effect of an exogenous shock on economics, independently from its generating context. To be more precise, a shock to preferences or any other element of the surrounding context will vary the expecta- tions and thus the speed and acceleration of the utilities to be maximized as well as the path to be followed by the consumer. However the shock can also affect the mecha- nism differently and have different results according to the way acceleration and speed interact together. In fact the shock can imply: a) a decrease or increase of velocity by changing the magnitude of the velocity (that is a variation in c ut caused by a variation in the consumption level). b) a change in the velocity by a variation in the form of the utility function (determined for example by a shock of preferences). u c) a combination of both. To be noticed that in the case of speed variation, we let the function vary with time as well. Given this new set of circumstances, the first order condition will be- come u 0 TT t tT c ucu t (10) If the consumer assumes as constant his utility in the T period, this first order condition will entail the same consequences as in the previous case of a time independ- ent utility (that is the uniformly constant acceleration precondition for the maximization). We simply allow for a different period velocity: 0 uu va T (11) 4. Motions and Its Variations—Empirical Evidences Our dynamic model defines an economic system with its own speed, occasionally modified by external forces changing its acceleration. Therefore if the economy is moving an external force exercised on it must explain an alteration in its speed. We would like to test this hy- pothesis inside US economy using a wide time period data: the purpose is to identify a general explanation for the way economics varies, no matter the generating con- text. We assume that the external force is exercised through a variation in the consumption rate of the eco- nomic system that explains the speed change in the GDP rate of growth. Thus, 11tttt tt GDPGDPcc c GDP c (12) we obtain the following as reported in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the plotting of GDP growth accelera- tion to consumption variation. As you can see, we fail to reject the hypothesis of a link between the increase/de- crease in the GDP and consumption growth rate. For our theory, this means that we can empirically support our idea that economics moves itself in a determined space with its own speed (the GDP and the GDP growth), that any crisis or development phenomenon has to be inter- preted as a variation of this velocity to be explained by an external force modifying the acceleration. To be no- ticed that we can draw this last conclusion also on the basis that of the more than forty years considered in the regression, meaning that we have abstracted from the particular case to the general explanation of the crisis and the economic dynamics phenomenon as well. Let’s con- sider the case of DSGE equilibrium approach from the dynamic—motion perspective. In its purest form (with- Table 1. OLS regression, January 1960 to April 2011. Coefficient 0.890762352 Standard error for coefficient 0.041966026 R2 0.688328096 F 450.5345545 Degree of freedom 204 GDP and REAL personal consumption expenditures quarterly data from January 1960 to April 2011, source FRED DATABASE Federal Reserve St. Louis USA. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  L. C. CHONG, L. BALESTRA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL 255 ‐0.04 ‐0.03 ‐0.02 ‐0.01 0.00 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 1960‐04‐01 1961‐05‐01 1962‐06‐01 1963‐07‐01 1964‐08‐01 1965‐09‐01 1966‐10‐01 1967‐11‐01 1969‐01‐02 1970‐02‐02 1971‐03‐02 1972‐04‐02 1973‐05‐02 1974‐06‐02 1975‐07‐02 1976‐08‐02 1977‐09‐02 1978‐10‐02 1979‐11‐02 1981‐01‐03 1982‐02‐03 1983‐03‐03 1984‐04‐03 1985‐05‐03 1986‐06‐03 1987‐07‐03 1988‐08‐03 1989‐09‐03 1990‐10‐03 1991‐11‐03 1993‐01‐04 1994‐02‐04 1995‐03‐04 1996‐04‐04 1997‐05‐04 1998‐06‐04 1999‐07‐04 2000‐08‐04 2001‐09‐04 2002‐10‐04 2003‐11‐04 2005‐01‐05 2006‐02‐05 2007‐03‐05 2008‐04‐05 2009‐05‐05 2010‐06‐05 US GDPgrowthratevariation(difference) theoreticalvalue Figure 1. Explanation of GDP growth rate by equilibrium theoretical model. out any influence from outside), we should conclude eco- nomics is moving in the following way: 10 tt uc uc (13) 1t uc uc t (14) If the consumer is maximising his utility, then it is impossible to increase utility by moving consumption across adjacent periods. Thus, if economics is in a DSGE we should have a constant rate of growth throughout the period, that is, no acceleration at all. This condition is clearly not respected for the US economy where we use the difference in GDP variations for the growth rate. We can observe it by comparing the empirical result and the results prescribed by the DSGE approach in Figure 2 (there’s no correlation at all). Therefore the equilibrium model cannot explain the way an economic system moves itself. To get more ef- fective results we should insert budget constraints, credit friction sexogenous shocks etc but, first, in this way, we are adding an extra element of explanation compared tothe other model6, second, even by allowing for all these elements, we can’t obtain such a general (scientific) ex- planation as with the speed model. On more general terms, the problem implied with equilibrium approach is the fact that dynamics is concerned with the motion of a system, i.e. with the change in the position of an object with respect to time and a frame of reference and with the space travelled in a specific time period (speed). Ac- cording to these definitions the DSGE suggested evolu- tion (with the equilibrium position and the time inde- pendence assumption) is clearly undetermined because we cannot link it to any specific temporal or speed ele- ments and therefore the results obtained within this con- text are not reliable. 5. Conclusions If we treat economic dynamics simply as a motion phe- nomenon avoiding therefore the single particular case, we cannot accept the equilibrium assumption anymore, that is to say we cannot accept a state of the nature gen- erally considered as one of the most fundamental axioms for economic models, especially and quite paradoxically in economic dynamics theories. The current dynamic paradigm in the literature entails a system in perfect equilibrium, whose motion is determined by random ex- ogenous shock where “time” is simply a “space” dimen- sion. We have demonstrated that economics cannot exist in such an eternal equilibrium: The economy moves with its own speed, not because of any hazard, but because of the “time passing” (a concept in the works of the found- ing fathers of economics) within which, elements within the system could change and move. Consequently the equilibrium assumption, and the dynamic general equi- librium in particular, are inadequate as a theoretical and empirical paradigm (given that the temporal factor is irreversible, we cannot accept a system conceived in a perpetual steady state). This paper develops a different dynamic concept to explain the “change” phenomenon more adequately, in particular we demonstrated that the “crisis” concept 6In this case, they might represent elements modifying the economic speed.  L. C. CHONG, L. BALESTRA 256 -0.06 -0.04 -0.02 0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 1960-04-01 1961-04-01 1962-04-01 1963-04-01 1964-04-01 1965-04-01 1966-04-01 1967-04-01 1968-04-01 1969-04-01 1970-04-01 1971-04-01 1972-04-01 1973-04-01 1974-04-01 1975-04-01 1976-04-01 1977-04-01 1978-04-01 1979-04-01 1980-04-01 1981-04-01 1982-04-01 1983-04-01 1984-04-01 1985-04-01 1986-04-01 1987-04-01 1988-04-01 1989-04-01 1990-04-01 1991-04-01 1992-04-01 1993-04-01 1994-04-01 1995-04-01 1996-04-01 1997-04-01 1998-04-01 1999-04-01 2000-04-01 2001-04-01 2002-04-01 2003-04-01 2004-04-01 2005-04-01 2006-04-01 2007-04-01 2008-04-01 2009-04-01 2010-04-01 2011-04-01 Consumption growth rate variation (accelleration)US GDP growth rate variation ( acceleration) Figure 2. Explanation of GDP growth rate dynamics by equilibrium theoretical model. could be explained by our proposed model of economic dynamics. The economic crisis results from a loss of ve- locity of the system, which otherwise (ceteris paribus) should have moved with a constant and uniform motion. From the empirical observations, we have also demon- strated that the same theoretical paradigm holds true the “other way round” as well, because economic growth can also be interpreted as a positive acceleration within the system. In this way, we have a more adequate theoretical explanation for understanding “change” in economics. Moreover, with this new dynamic model, we can also do away with the unrealistic ideas of the current economic dynamics models, such as “reversibility” of “time” and the unexplained and hence mysterious “exogenous shock”. Clearly, the theoretical implications of the new- proposed model are many (besides, we have demon- strated our position in its simplest form here), given that the “equilibrium” assumption is at the heart of so many economic models and theories, and the need for govern- mental policy interventions to avoid economic collapse with its adverse implications on human suffering. REFERENCES [1] M. Desai, “Financial Crises and Global Governance,” In: M. Desai and Y. Said, Eds., Global Governance and Fi- nancial Crises, Routledge, London, 2004, pp. 6-17. [2] “Motion (Physics): The Free Encyclopedia,” Wikipedia, 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Motion_(physic s)&oldid=508415312 [3] “Dynamics (Mechanics): The Free Encyclopedia,” Wiki- pedia, 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Dynamics_(me chanics)&oldid=5075521 [4] F. Machlup, “Equilibrium and Disequilibrium: Misplaced Concreteness and Disguised Politics,” Economic Journal, Vol. 68, 1958, pp. 9-42. [5] A. C. Chiang, “Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics,” Mc Graw-Hill, New York, 1984. [6] J. Adda and R. Cooper, “Dynamic Economics—Quantita- tive Methods and Applications,” MIT Press, Cambridge, 2003. [7] M. I. Kamien and N. Schwarz, “Dynamic Optimization— The Calculus of Variations and Optimal Control in Eco- nomics and Management,” Elsevier, New York, 1981. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL |