C. COHEN, M. SCHWARTZ

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL

200

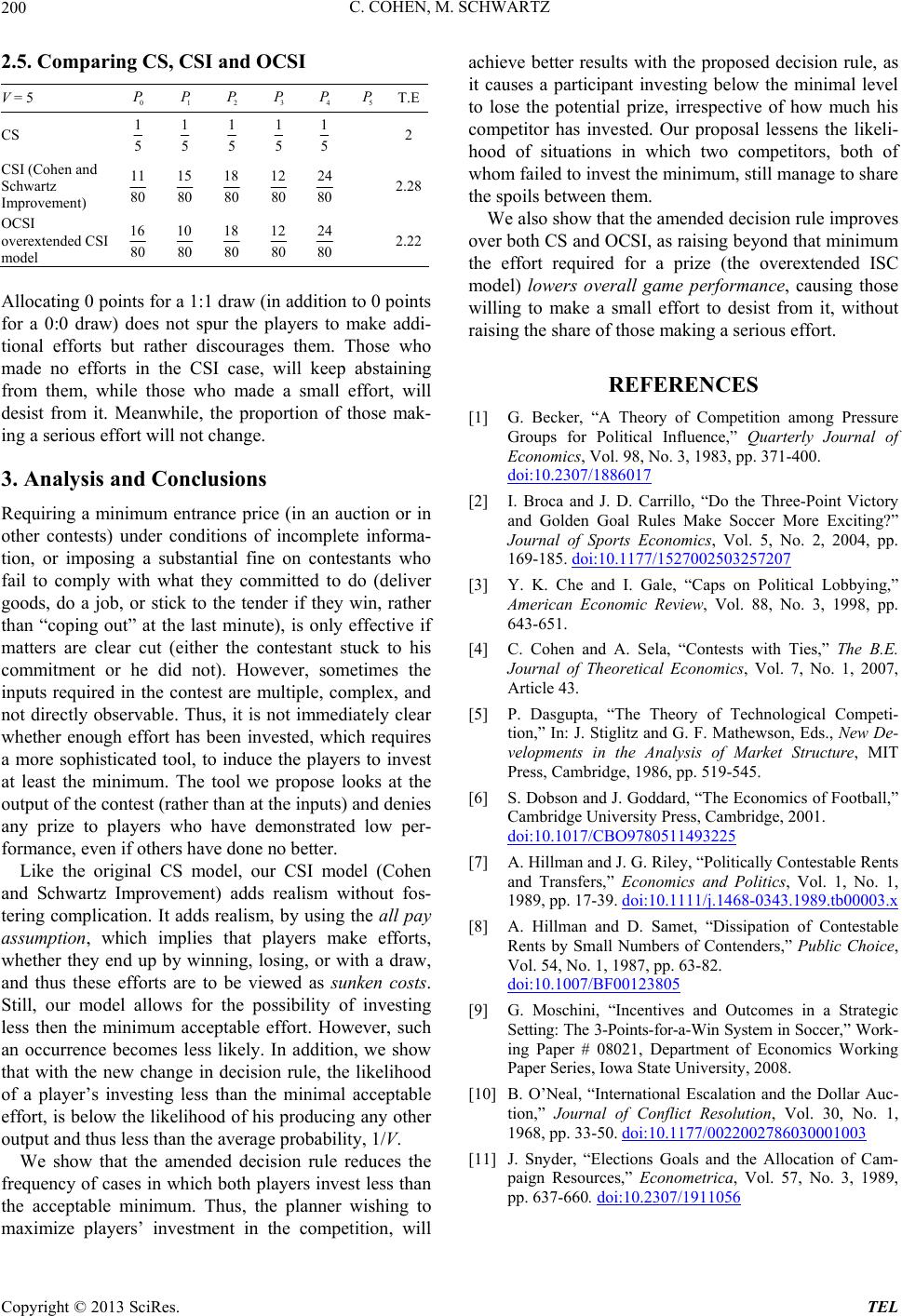

2.5. Comparing CS, CSI and OCSI

V = 5 0

P 1

P 2

P 3

P 4

P 5

PT.E

CS 1

5 1

5 1

5 1

5 1

5 2

CSI (Cohen and

Schwartz

Improvement)

11

80 15

80 18

80 12

80 24

80 2.28

OCSI

overextended CSI

model

16

80 10

80 18

80 12

80 24

80 2.22

Allocating 0 poin ts for a 1 :1 draw (in add ition to 0 po ints

for a 0:0 draw) does not spur the players to make addi-

tional efforts but rather discourages them. Those who

made no efforts in the CSI case, will keep abstaining

from them, while those who made a small effort, will

desist from it. Meanwhile, the proportion of those mak-

ing a serious effort will not change.

3. Analysis and Conclusions

Requiring a minimum entrance price (in an auction or in

other contests) under conditions of incomplete informa-

tion, or imposing a substantial fine on contestants who

fail to comply with what they committed to do (deliver

goods, do a job, or stick to the tender if they win, rather

than “coping out” at the last minute), is only effective if

matters are clear cut (either the contestant stuck to his

commitment or he did not). However, sometimes the

inputs required in the contest are multiple, complex, and

not directly observable. Thus, it is not immediately clear

whether enough effort has been invested, which requires

a more sophisticated tool, to induce the players to invest

at least the minimum. The tool we propose looks at the

output of the contest (rather than at the inputs) and denies

any prize to players who have demonstrated low per-

formance, even if others have done no better.

Like the original CS model, our CSI model (Cohen

and Schwartz Improvement) adds realism without fos-

tering complication. It adds realism, by using the all pay

assump tion, which implies that players make efforts,

whether they end up by winning, losing, or with a draw,

and thus these efforts are to be viewed as sunken costs.

Still, our model allows for the possibility of investing

less then the minimum acceptable effort. However, such

an occurrence becomes less likely. In addition, we show

that with the new change in decision rule, the likelihood

of a player’s investing less than the minimal acceptable

effort, is below the likelihood of his producing any other

output and thus less than the average probability, 1/V.

We show that the amended decision rule reduces the

frequency of cases in which both players invest less than

the acceptable minimum. Thus, the planner wishing to

maximize players’ investment in the competition, will

achieve better results with the proposed decision rule, as

it causes a participant investing below the minimal level

to lose the potential prize, irrespective of how much his

competitor has invested. Our proposal lessens the likeli-

hood of situations in which two competitors, both of

whom failed to invest the minimum, still manag e to share

the spoils between them.

We also show that the amended decision rule improves

over both CS and OCSI, as r aising beyond that minimu m

the effort required for a prize (the overextended ISC

model) lowers overall game performance, causing those

willing to make a small effort to desist from it, without

raising the share of those making a serious effort.

REFERENCES

[1] G. Becker, “A Theory of Competition among Pressure

Groups for Political Influence,” Quarterly Journal of

Economics, Vol. 98, No. 3, 1983, pp. 371-400.

doi:10.2307/1886017

[2] I. Broca and J. D. Carrillo, “Do the Three-Point Victory

and Golden Goal Rules Make Soccer More Exciting?”

Journal of Sports Economics, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2004, pp.

169-185. doi:10.1177/1527002503257207

[3] Y. K. Che and I. Gale, “Caps on Political Lobbying,”

American Economic Review, Vol. 88, No. 3, 1998, pp.

643-651.

[4] C. Cohen and A. Sela, “Contests with Ties,” The B.E.

Journal of Theoretical Economics, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2007,

Article 43.

[5] P. Dasgupta, “The Theory of Technological Competi-

tion,” In: J. Stiglitz and G. F. Mathewson, Eds., New De-

velopments in the Analysis of Market Structure, MIT

Press, Cambridge, 1986, pp. 519-545.

[6] S. Dobson and J. Goddard, “The Economics of Football,”

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001.

doi:10.1017/CBO9780511493225

[7] A. Hillman and J. G. Riley, “Politically Contestable Rents

and Transfers,” Economics and Politics, Vol. 1, No. 1,

1989, pp. 17-39. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0343.1989.tb00003.x

[8] A. Hillman and D. Samet, “Dissipation of Contestable

Rents by Small Numbers of Contenders,” Public Choice,

Vol. 54, No. 1, 1987, pp. 63-82.

doi:10.1007/BF00123805

[9] G. Moschini, “Incentives and Outcomes in a Strategic

Setting: The 3-Points-for-a-Win System in Soccer,” Work-

ing Paper # 08021, Department of Economics Working

Paper Series, Iowa State University, 2008.

[10] B. O’Neal, “International Escalation and the Dollar Auc-

tion,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 30, No. 1,

1968, pp. 33-50. doi:10.1177/0022002786030001003

[11] J. Snyder, “Elections Goals and the Allocation of Cam-

paign Resources,” Econometrica, Vol. 57, No. 3, 1989,

pp. 637-660. doi:10.2307/1911056