Vol.4, No.5B, 116-121 (2013) Agricultural Sciences doi:10.4236/as.2013.45B022 The development of soy sauce from organic soy bean Shoupeng Wan, Yanxiang Wu, Cong Wang, Chunling Wang, Lihua Hou* Key Laboratory of Food Nutrition and Safety(Tianjin University of Science & Technology), Ministry of Education, Tianjin, China; *Corresponding Author: lhhou@tju.edu.cn Received 2013 ABSTRACT Soy sauce with a high salt liquid-state fermenta- tion process was prepared by using organic soy beans as raw material. Beidahuang organic soy bean was selected among different raw materi- als. Here, the best technique was determined. Firstly, the organic soy beans were soaked for 7 hours under 121℃, steamed for 15 min and mixed with the fried wheat (5:5, w/w). After in- oculated with Aspergillus oryzae 3.042 (0.3%, w/w) and cultured for 36 hours, the koji was ob- tained. When the brine (2:1, w/w) was added, fermentation started. At the end of the fermenta- tion, is of lavone content of organic soy sauce was 0.22 mg·g-1 higher than those in the non- organic soy beans. In addition, compared to the control there were a higher unsaturated fatty acids content, the linoleic acid content in crude fat of 51.61% and γ-linolenic acid content in crude fat of 0.55%. Keywords: Organic Soy Bean; Soy Sauce; Fermentation; Fatty Acid; Isoflavone 1. INTRODUCTION Soy sauce is a necessary seasoning in many Asian countries. As a condiment and coloring agent, it almost appears in every meal on the table. The annual produc- tion of soy sauce in China is more than 5,000,000 tons, accounting for over 55% of the world production [1]. The raw material of the soy sauce plays a very important role to the quality of the soy sauce including the flavor, the safety, the nutrition et al [2]. As the development of society and the economy, more and more people pay attention to food nutrition and health problems. There- fore, organic foods are more and more popular. Soy sauce is produced by fermentation of steamed soybean and raw wheat with Aspergillus oryzae [3]. Or- ganic soybean contains more high quality protein, higher unsaturated fatty acid content and more balanced nutri- tion collocation, belongs to the high-end soybean prod- ucts, can meet the high consumption demand with high food quality [4]. Soybean isoflavone is an important or- ganic soybean functional component. Soybean isofla- vone is the best natural anti-cancer substances [5], and soybean isoflavone can significantly reduce blood cho- lesterol level, estrogen acting synergistically [6]. Besides, for rich in biological active substance, organic soybean fermentation food had many unique functions, such as anti-cancer, dissolve thrombus, antioxidant, fall blood pressure and antibacterial, etc [7]. Organic soy bean had not been large-scale developed for the valuable resources, resulting in the decrease of the economic value of the organic soy beans and the enthusiasm of planting organic soy beans. To meet the needs of health, organic soy bean was used as materials to produce the soy sauce in this study. Using high-salt diluted state fermentation process, a high-quality organic soy bean soy sauce was obtained. 2. EXPERIMENTAL PREPARATION 2.1. Preparation of Materials and Chemicals Organic soybean (origin, the northeast China) and the non-organic soybean (origin, the northeast China) pro- vided from the marked. Fatty acid standards, include methyl stearate, methyl oleate, methyl palmitate, methyl γ-linoleate, methyl linolenate, were purchased from Sigama-Aldrich (Shanghai) trading Co. Ltd. Isolavone standard (Genistein), were purchased from Beijing Dingguo biological Technology Co., Ltd (China). All other chemicals used were of analytical grade. 2.2. Preparation of Seed Koji To prepare seed koji, wheat bran was first blend with 100% hot water (w/w) and cooked at 121℃ for 30 min. The cooked wheat bran was inoculated with A. oryzae spores and incubated at 30℃ for 3 days, then dried in a drying cabinet at 60℃and was grounded into powders. The germination rate and the spore count were deter- mined according to the Chinese National Standard. 2.3. Preparation of Koji Cooked Organic soy beans were mixed with fried Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/as/  S. P. Wan et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 116-121 117 wheat which had been soaked in water (1:1, w/w) for 30 min previously, quickly blend and cooled to a tempera- ture of about 35℃, then inoculated with a certain amount of A. oryzae seed koji. The initial culture temperature was 30℃ ± 2℃. After a period of time, the culture tem- perature was adjusted to 25℃. 2.4. Fermentation Process and Preparation of the Samples The resulting koji was fermented in 18% to 20% brine solution at a ratio of 2:1 (Brine: Raw material, w/w) to yield soy sauce mash (brine fermentation or soy sauce mash fermentation process) [8]. At first, the cultivate temperature was controlled at 15℃, and then increased 1℃ per day until to the temperature of 30℃. After fer- mentation of 6 month, the ripened soy sauce mash was pressed to yield soy sauce. At various time intervals of the fermentation process, samples of 100 g soy sauce mash were taken from each of the mash tanks containing the same type of koji. They were stirred individually and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were filtrated through Whitman no.3 paper. The filtrate, regarded as raw soy sauce, was placed in brown bottles and kept at 4℃ [9]. For each analysis, tests were per- formed three times and all results presented are the av- erage. As the control, the soy sauce derived from soy- bean was produced under the same conditions. 2.5. Parameters Analysis Determination of the quality parameters of soy sauces total nitrogen and total solids were determined by AOAC methods 991.20 and 990.2 (AOAC, 2000), respectively. Salt-free soluble solids were calculated as TS minus SC (GB18186-2000, 2001). Amino nitrogen content was measured as described by the Chinese National Standard. Determination of the fatty acids contents were by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. The fatty acids were detected by Gas chromatograph [10]. 1.0000 g sample, 100 mL mixed solution of chlo- roform and methanol (V/V) was added, putted in the water bath shaker (New Brunswick Scientifics C24, jin- tan, China) at 38℃ for 14h, filtered by the chronic filter paper. After the rotary evaporation (55℃), add 10 ml 0.5 mol/L NaOH : ethanol, kept in the water bath at 60℃ for 40 min. Remove the unsaponifiable matter with a sepa- rating funnel by adding 10 mL aether twice. Then adjust the pH to 2-3 with 10% solution of hydrochloric acid, add 5 ml normal saline, extracted by 10 ml hexane, take the upper, using ammonia stripping method remove the solvent hexane, so we get the fatty acid. the GC2010 (Shimadzu Co.), FID detector, chromatographic column: CBP - 20 capillary column (50 m, 0.25 mm, 0.25 um), Initial temperature: 180℃, temperature rising to 240℃ at a speed of 6 ℃/min and keep 40 min, Injection port temperature: 280℃, Detector temperature: 280℃. Car- rier gas: high purity nitrogen, Velocity 30 ml/min, and the air velocity: 400 ml/min, Hydrogen flow rate: 47 ml/min, sample size: 1 μl [11]. 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The production processes of fermented soy sauce con- sisted of four major steps, including raw material selec- tion, koji production, brine fermentation and refining [12]. 3.1. Selection of Raw Materials In this study, organic soy bean and non-organic soy beans were compared: organic soy bean (HO) and non- organic soy bean (HN). By comparing protein, crude fat, crude starch, moisture, ash content and fatty acid compo- sition, the differences of the basic components between organic soy beans and non-organic soy bean were got. Figure 1 showed that the higher protein content of or- ganic soy beans varieties was HO; the higher ash content of organic soy beans varieties was non-organic soy beans; the higher crude starch content of organic soy beans va- rieties was HO. Figure 2 indicated the content of un- saturated fatty acid of HO was more than HN. In fer- mentation process of the soy sauce, the level of the pro- tein content was very important. In addition, the fatty acids components in the organic soy beans exhibited a higher unsaturated fatty acids content, the linoleic acid content in crude fat of 51.61%, γ-linolenic acid content in crude fat of 0.55%. Linoleic acid, α-Linolenic andγ- Linolenic acid were the essential fatty acids of the human body. Thereby, HO had adventages to be the raw materi- als of fermented soy sauce. 3.2. Determination of the Cooking Process The purpose of cooking was to make moderately de- naturing of the raw materials, for the reason that easy to Figure 1. Comparison of the various components of or- ganic soy bean and non-organic soy bean. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/as/  S. P. Wan et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 116-121 118 be used by A. oryzae and provide a basis for the later enzymatic decomposition [13]. The moderate cooking were needed due to effect obviously on the utilization of raw material and quality of soy sauce. Whether the cooking was appropriate depend on the soaking time, cooking time and cooking temperature. As seen from Figure 3(a), with the extension of cooking time, the digestibility showed a rising trend, but over 8 hours, digestibility declined. The reason may be the water-soluble protein dissolution. Therefore, 7 hours was selected as soaking time (a little different with the seasons change). Figure 3(b) and Figures 3-7 indicated that during the initial stage, digestibility was signifi- cantly increased with the extension of the cooking time and temperature. However, more than 25 minutes and 123℃ the digestibility began to decrease, which may be due to excessive degeneration of the protein. Finally, 25 minutes and 123℃ was selected as cooking time and cooking temperature. Figure 2. Comparison of the fatty acids of the four kinds of or- ganic soy beans, Peak No.1 respects Palmitic acid; Peak No.3 respects Stearic acid; Peak No.6 respects Linoleic acid; Peak No.7 respects γ-Linolenic acid. 50 60 70 80 90 100 46810 Soak ing t ime (h) Digestibilit y (%) (a) 50 60 70 80 90 100 15 20 25 30 Cook ing t ime (min) Digestibility (%) (b) 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 115121 126 Cooking t emperatu r e (℃) Digestibility (%) (c) Figure 3. The different soaking beans time (a), cook- ing beans time (b) and cooking beans temperature (c), Data presented are the average of duplicate ex- periments. 3.3. Determination of the Koji Process The koji production process was the most important in the fermentation of the soy sauce. At this stage, the A. oryzae grew to a large number, and produced a complex enzyme system. The proportion of raw materials, koji duration, the amount of seed koji, moisture, humidity and temperature were the main factors that affected the pro- duction of enzymes. This study investigated the rela- tionship between the enzyme activity and the amount of seed koji, proportion of raw materials and the duration time of koji, respectively, in order to determine the best process [14]. Standard of high-quality of seed koji was germination rate > 90%, spore count >109 (A·g-1) [15]. The results of the amount of the seed koji were observed from Figure 4(a). With the increase of the amount of the seed koji, the protease activity was significantly increased but once more than a certain numerical, protease activity declined. This may be because the seed koji was excessively added to the raw material, resulted in inadequate nutrition and lack of space. The growth and reproduction of the A. oryzae was affected, leading to the decline of protease activity. Therefore, the added amount of the koji was 0.3% (w·w-1). Figure 4(b) demonstrated that when the ratio of raw material was 5:5, the protease activity reached a maximum. Meanwhile, the protease activity attained the highest at 36 hours. Once more than 36 hours, A.oryzae began to pick spores and affect the gen- eration of the protease. 3.4. Fermentation Process and Chemical Indicators During the fermentation of soy sauce, proteins in the raw materials were hydrolyzed into small molecular in- cluding peptides and amino acids by the proteases pro- duced from A.oryzae. The total nitrogen content was an important indicator to measure soy sauce grade [16]. As can be seen from Figure 5(a), the total nitrogen content showed some fluctuations in the soy sauce fermentation Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/as/  S. P. Wan et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 116-121 119 process. Its content had been slow to improve as time progresses. The total nitrogen content in the organic soy bean sauce was higher than that in the non-organic soy sauce. In addition, amino acid nitrogen can increase the flavor of soy sauce and was an important quality indica- tor of the soy sauce. Figure 5(b) indicated that the amino acid nitrogen content increased dramatically and then increased little. This may be because Maillard reaction need amino and carboxyl [17]. Amino nitrogen content was higher in the organic soy sauce than that in the non- organic soy sauce. Salt-free solids refer to various decomposition produc- tions of soluble protein, such as amino acids, peptone, peptides, dextrin, low molecular weight sugars, organic acids, alcohols, esters, pigments and other substances. It was one of the major nutrition matters in soy sauce. There was a direct relationship between salt-free solids content and quality of soy sauce. Figure 5(c) revealed that organic soy sauce had a higher content. 3.5. Isoflavone Results Isoflavone was a functional ingredient in soy beans. The isoflavone was a water soluble organic substance (a) Annotation: 1 for the 5:5, 2 for the 4.5:5.5, 3 for the 6:4. (b) Figure 4. The relationship of the different inoculation amount (a), the different ratio and different time of raw materials (Or- ganic soy bean: wheat) and protease activity (b). Data presented were the average of duplicate experiment. with small molecule, have effectively anti-cancer func- tion, anti-tumor function and prevent the cardiovascular disease and the osteoporosis disease. Therefore, dietary intake of soybeans can keep the body health and decrease the risk of some disease and a number of cancers includ- ing those of breast, colon and prostate. Figure 6(a) showed the liquid chromatogram of standards, Peak No.1 respects the Daidzin, Peak No. 2 respects the Genistin and Peak No.1 respects the Genistein, Figures 6(b)-(e) showed the liquid chromatogram of different samples. Figure 7 demonstrated the isoflavone content of the organic soy beans was higher than that in the non-organic soy beans, followed with the higher content in the or- ganic soy sauce. The isoflavone content of organic soy- bean group in the raw material was 3.81 mg﹒g-1, con- tent (a) (b) 14.0 14.4 14.8 15.2 15.6 16.0 0 15 30 45 60 75 90 105 120 135 150 165 180 Aging time ( d ) sa lt -free so lid mass content (g/100mL) Organic Non-organic (c) Figure 5. Total nitrogen content (a), amino nitrogen con- tent (b) and salt-free solids content (c). Data presented are Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/as/  S. P. Wan et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 116-121 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/as/ 120 the average of duplicate experiments. (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) Figure 6. Liquid chromatogram of the isoflavone standards (a), isoflavone in the organic soy beans (b), isoflavone in the non-organic soy beans (c), isoflavone in the organic soy sauce (d), isoflavone in the non-organic soy sauce (e). (a) (b) Figure 7. Isoflavone content in the organic soy bean and non-organic soy bean(a), isoflavone content in the organic soy sauce and non-organic soy sauce (b). Data presented are the average of duplicate experiments. of the organic group soy sauce at the end of the fermen- tation was 0.22 mg﹒g-1. Openly accessible at 4. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by these projects in China (2012AA022108, 31000768, 2012BAD33B04, 2012GB2A100016, 2013AA102106, IRT1166, 10ZCZDSY07000 and 31171731). REFERENCES [1] Wanakhachornkrai, P. and Lertsiri, S. (2003) Comparison of determination method for volatile compounds in Thai soy sauce. Food Chem, 83, 619-629. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00256-5 [2] Zhang, Y.F. and Tang, W.Y. (2001) Flavor and taste com- pounds analysis in Chinese solid fermented soy sauce. Afr J Biotechnol, 8, 673-681.. [3] Qin, L.K. and Ding, X.L. (2007) Formation of taste and odor compounds during preparation of douchiba, a Chi- nese traditional soy-fermented apperizer. J Food Biochem, 2, 230-251. d oi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2007.00105.x [4] Williams, C.M.(2002) Nutritional quality of organic food:shades of grey or shades of green.P Nutr Soci , 61, 19-24. doi:10.1079/PNS2001126 [5] Lee, I.H. and Chou, C.C. (2006). Distribution profiles of  S. P. Wan et al. / Agricultural Sciences 4 (2013) 116-121 121 isoflavone isomers in organic soy bean kojis prepared with various filamentous fungi. J Agr Food Chemy, 54, 1309-1314. doi:10.1021/jf058139m [6] Setchell K.D.R., Brown, N.M., Desai, P.D., Zimmer-Nechemias Zimmer-Nechemias, L., Wolfe, B.E., Brashear, W.T., Kirschner, A.S., Cassidy, A. and Heubi, J.E. (2001) Bioavailability of pure isoflavone in healthy humans and analysis of commercial soy isoflavone sup- plements. The American Society for Nutritional Sciences, 4, 13625-13755. [7] Kyung, K., Jose, M. and Mauro, A. (2002) Benefits of soy isoflavone therapeutic Regimen on Menopausal symptoms. Obstetric & Gynecology, 99, 389-394. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01744-6 [8] Minamino, T., Kitakaze, M., Asanuma, H., Tomiyama, Y., Shiraga, M. and Sato, H. (1998). Endogenous adenosine inhibits P-selectin-dependent formation of coronary thromboemboli during hypoperfusion in dogs. The Jour- nal of Clinical Investigation, 101, 1643-1653. doi:10.1172/JCI635 [9] Ling, M.Y. and Chou, C.C. (1996) Biochemical changes during the preparation of soy sauce koji with extruded and traditional raw materials. International Journal Food Science & Technology, 31, 511-517. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2621.1996.00358.x [10] Seppänen-Laakso, T. and Laakso, I.R. (2002) Seppeane- nAnalysis of fatty acids by gas chromatography, and its relevance to research on health and nutrition. Analytical Chimica Acta, 465, 39-62. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(02)00397-5 [11] Collomb, M., Butikofer, U., Sieber, R., Jeangros, B. and Bosset, J.O. (2002) Composition of fatty acids in cow's milk fat produced in the lowlands, mountains and high- lands of Switzerland using high-resolution gas chroma- tography. International Dairy Journal, 12, 649-659. [12] Zhang, Y.F. (2010). Biochemical changes in low-salt solid-state fermented soy sauce. J Biotechnol, 9, 15-21. [13] Yan, L.J, Zhang, Y.F., Tao, W.Y., Wang, L. and Wu, S. (2008) Rapid determination of volatile flavor components in soy sauce using head space solid phase micro extrac- tion and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Chi- nese Journal of Chromatography, 26, 285-291. doi:10.1016/S1872-2059(08)60017-6 [14] Su, Y.C. (1980) Traditional fermented foods in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the Oriental Fermented Foods, Food In- dustry Research and Development Institute, Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China, 15-30. [15] Su, N.W., Wang, M.L., Kwok, K.F. and Lee, M.H. (2005). Effects of temperature and sodium chloride concentration on the activities of proteases and amylases in soy sauce koji. Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53, 1521-1525. doi:10.1021/jf0486390 [16] Wanakhachornkrai, P. and Lertsiri, S. (2003) Comparison of determination method for volatile compounds in Thai soy sauce. Food Chemistry, 83, 619-629. doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00256-5 [17] Shahidi, F. and Ho, C.T. (1999) Role of the Maillard re- action in browning during moromi process of Thai soy sauce. Flavor and Chemistry of Ethnic Foods, Hertford- shire, HRT, United Kingdom, 5-14. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/as/

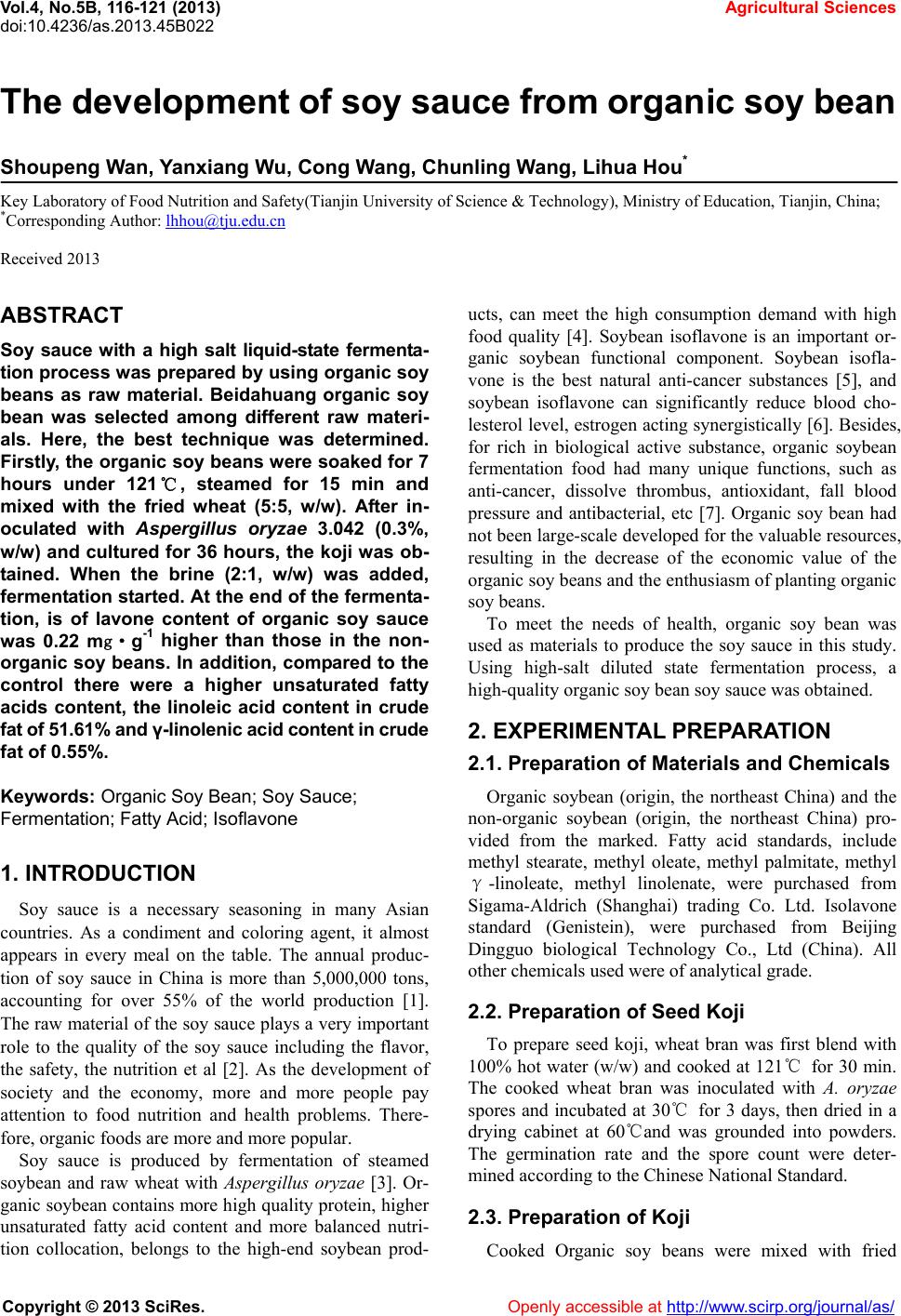

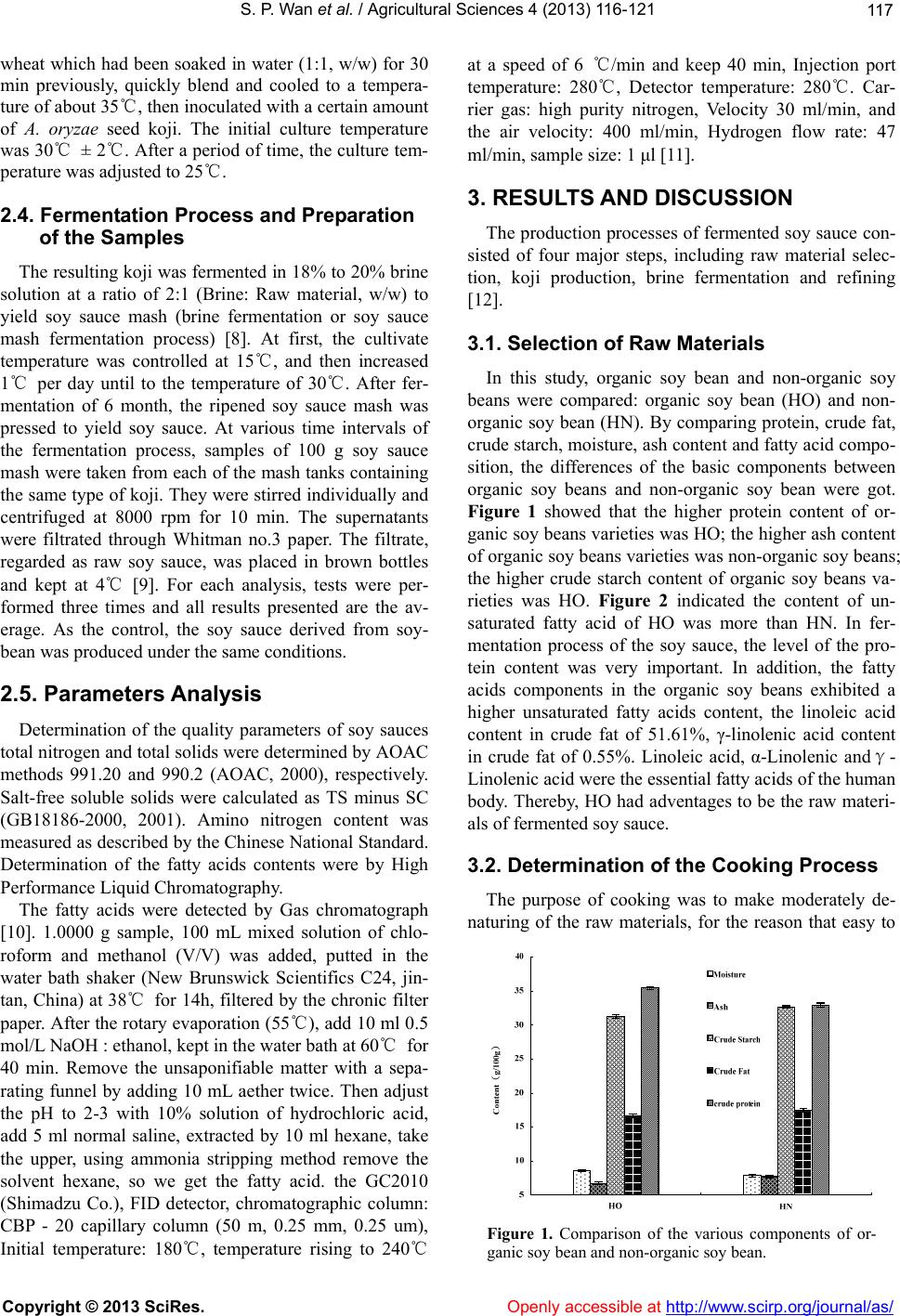

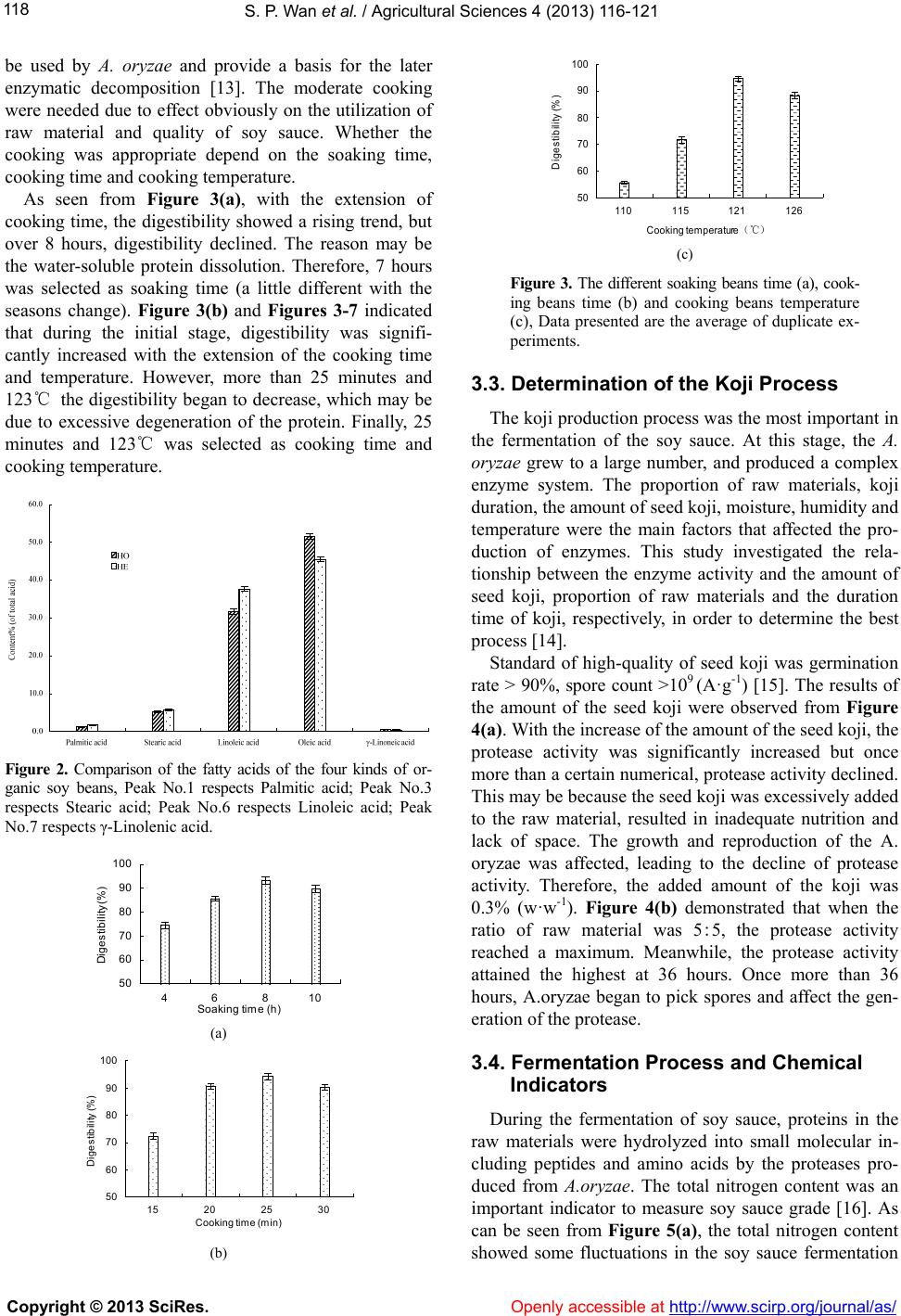

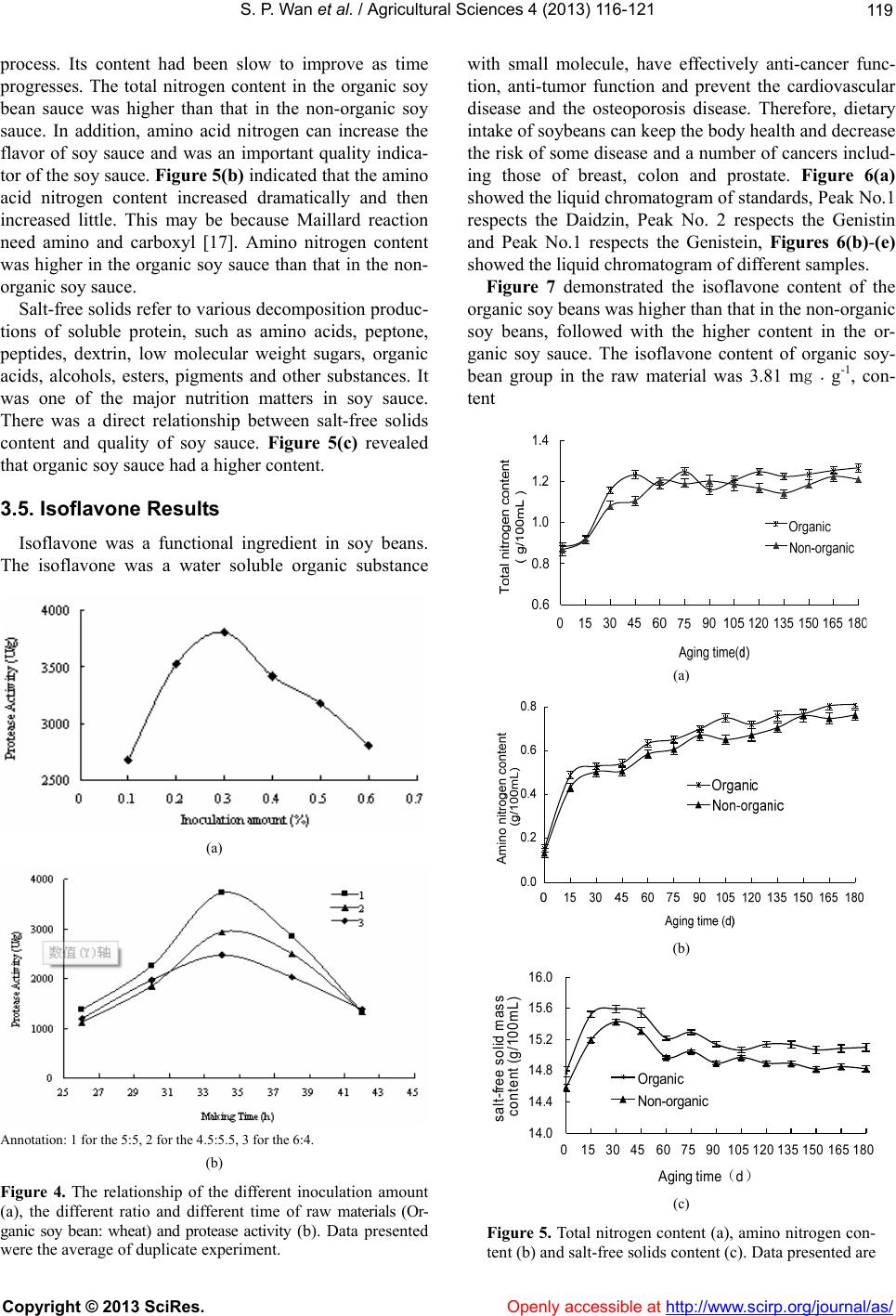

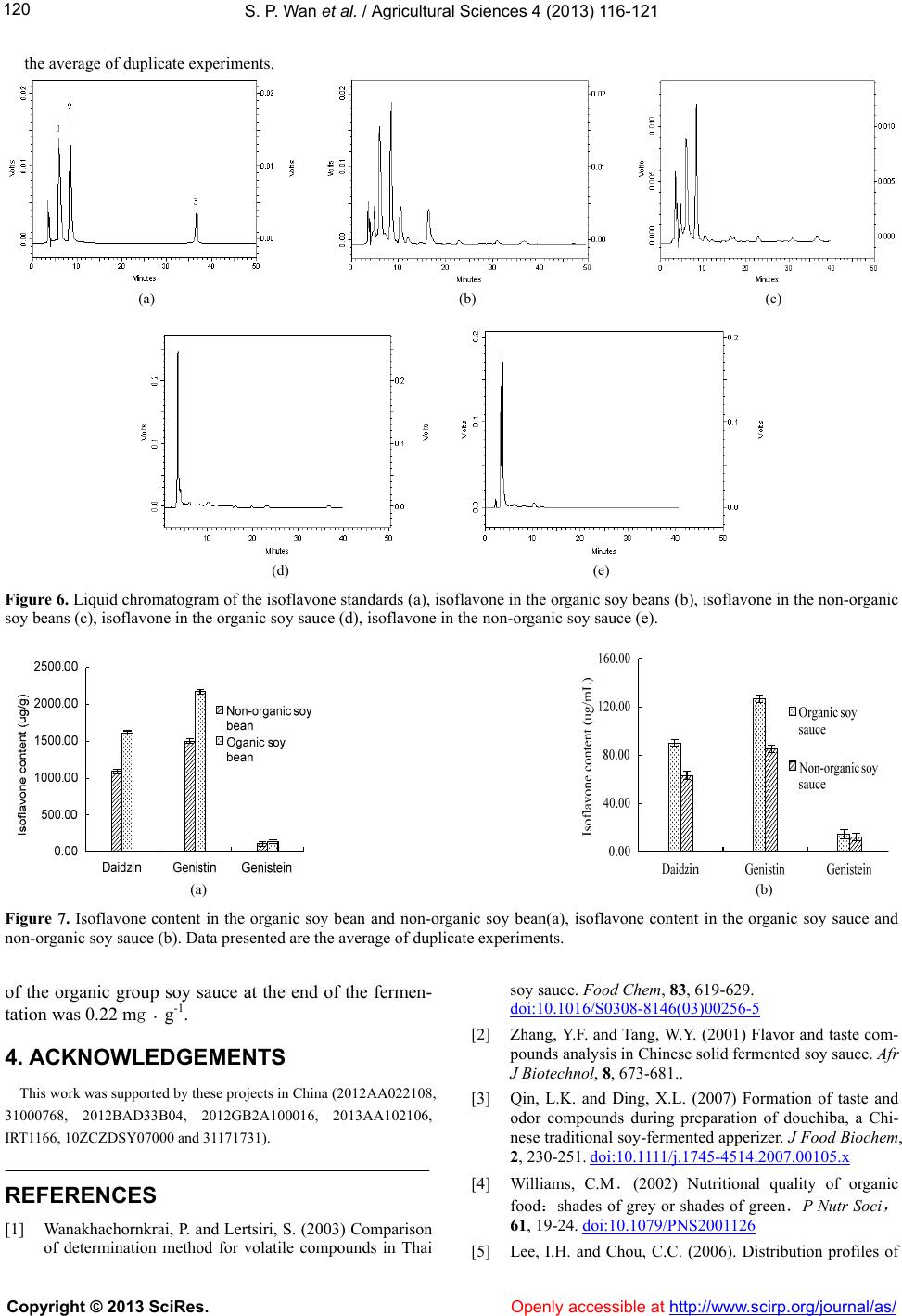

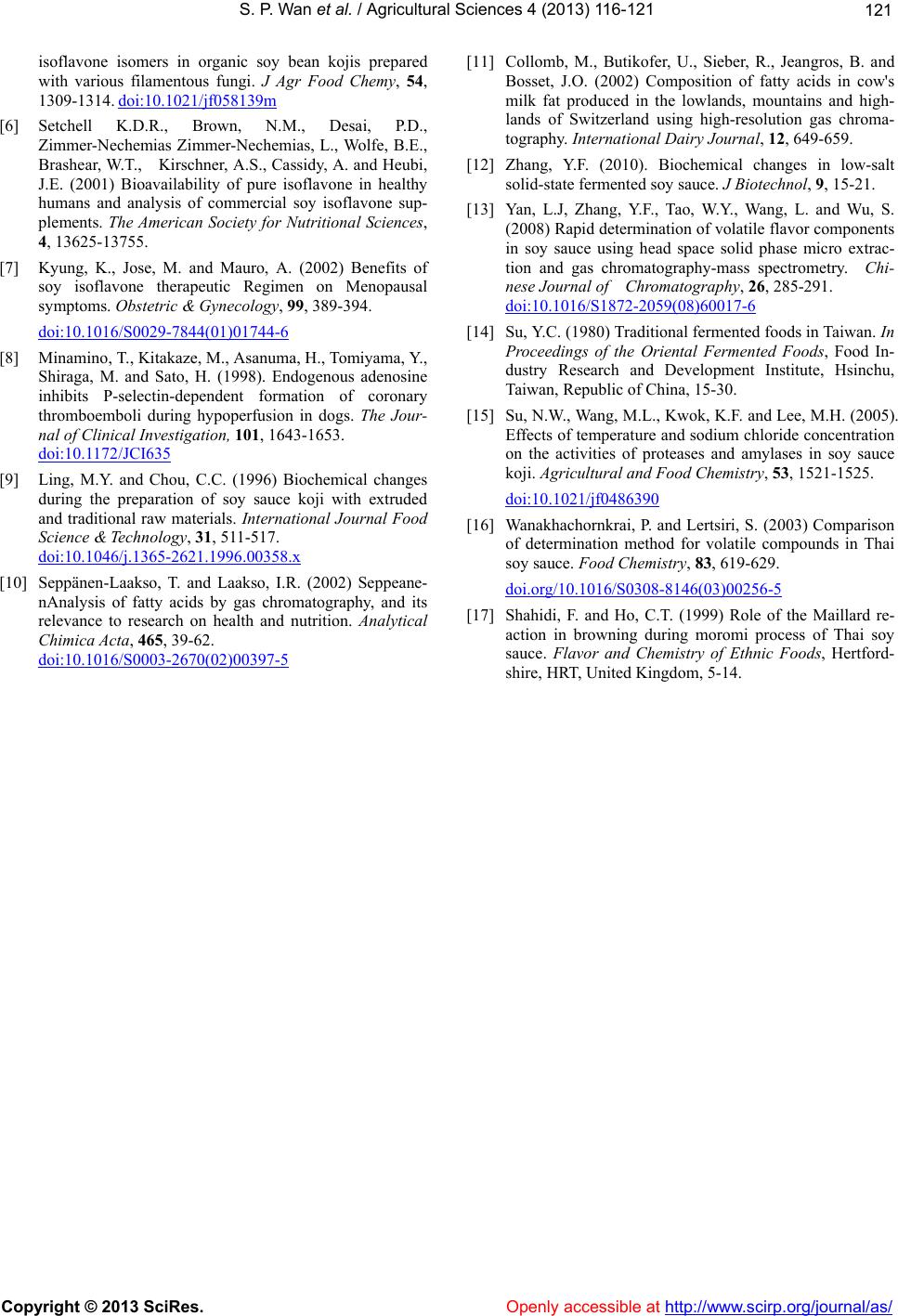

|