Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

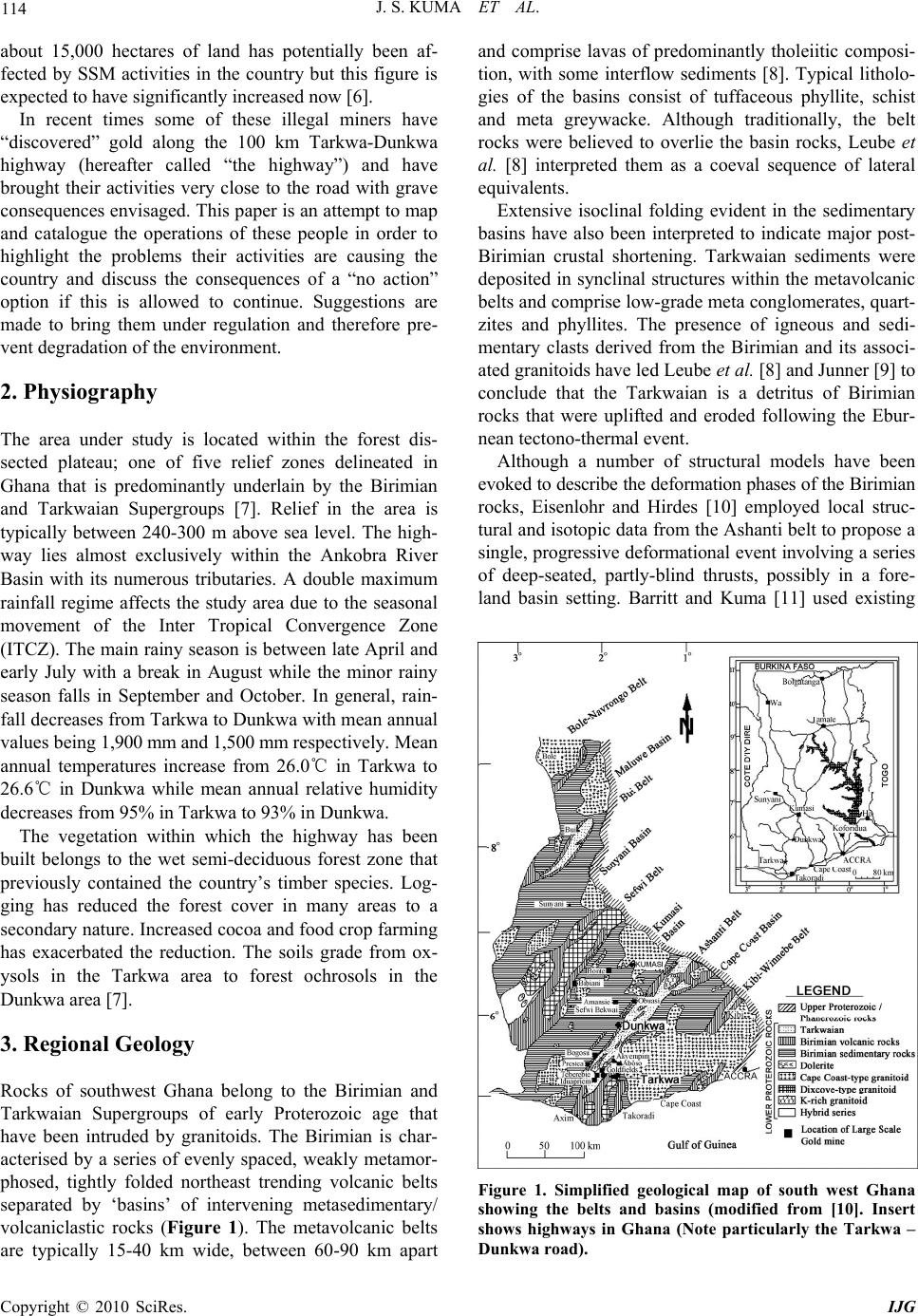

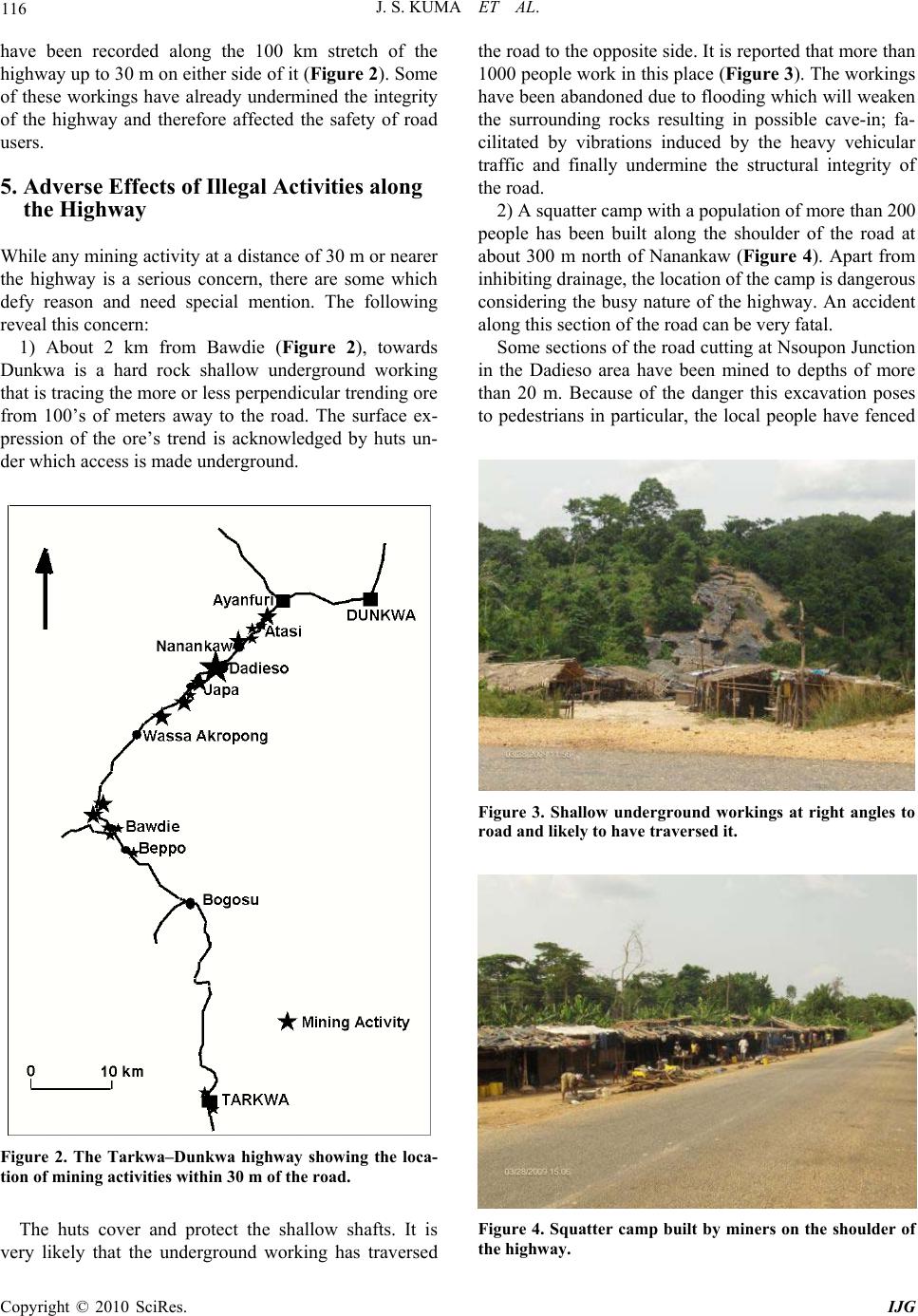

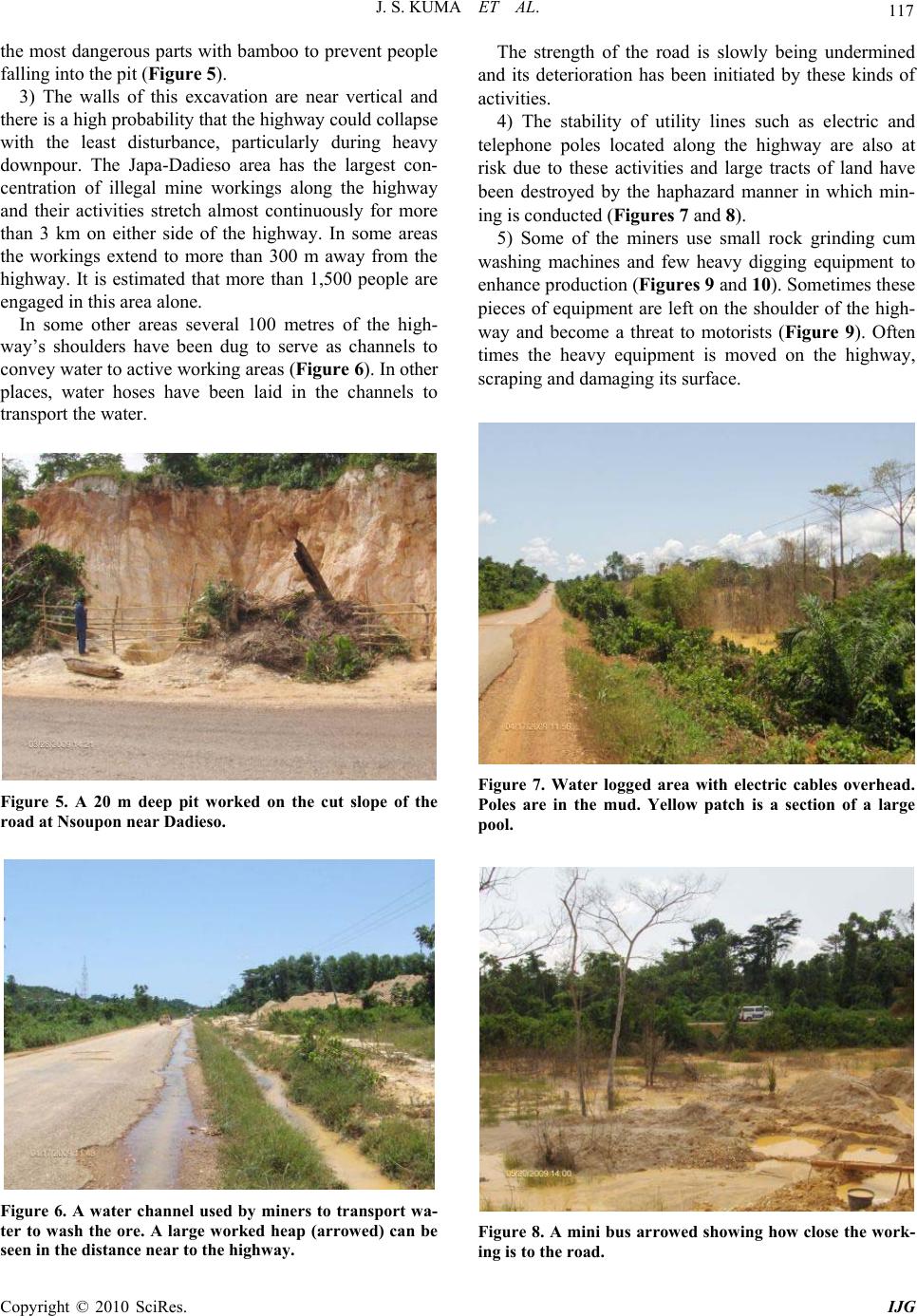

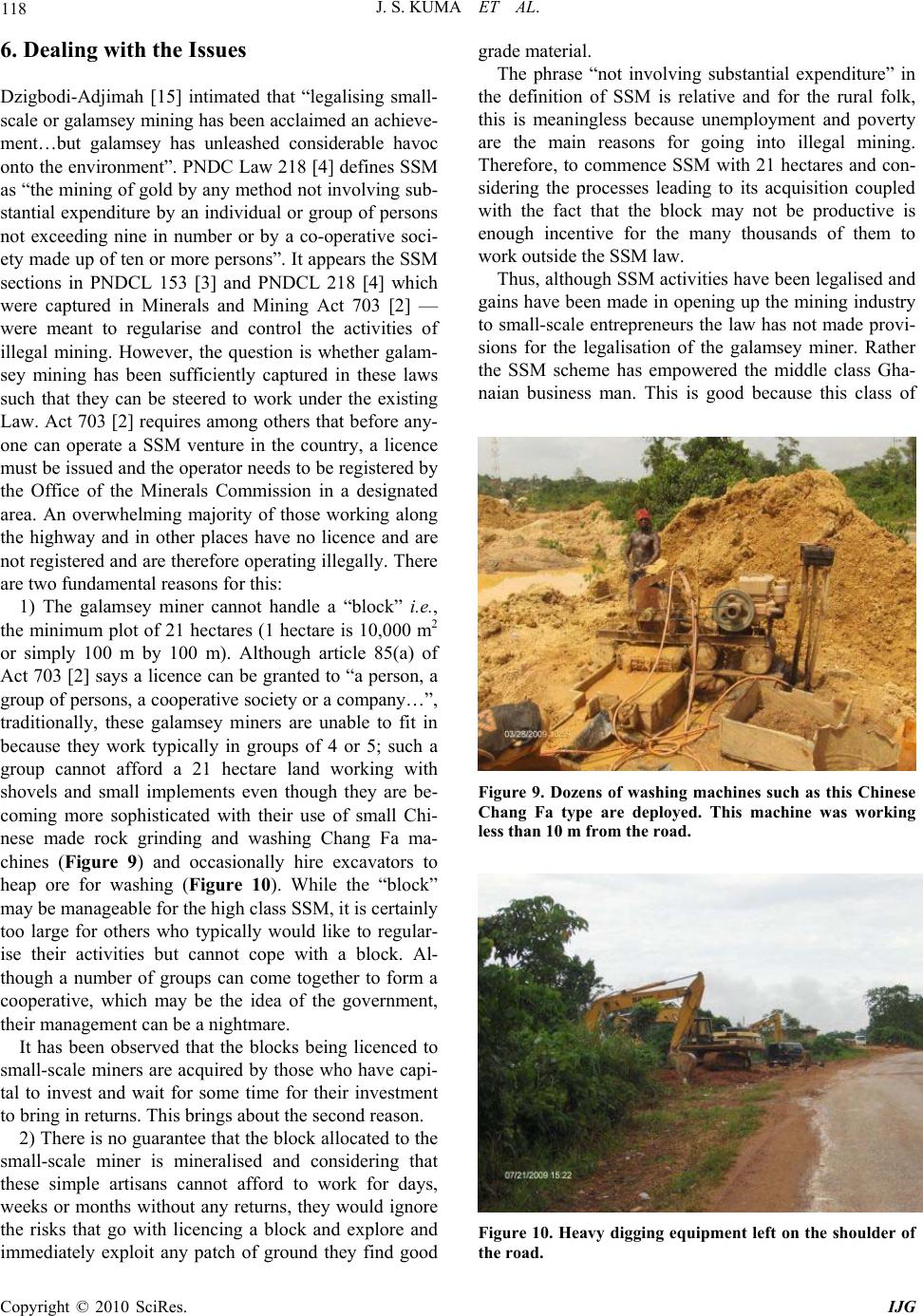

International Journal of Geosciences, 2010, 1, 113-120 doi:10.4236/ijg.2010.13015 Published Online November 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ijg) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG The Need to Regularise Activities of Illegal Small-Scale Mining in Ghana: A Focus on the Tarkwa-Dunkwa Highway* Jerry S. Kuma, Jerome A. Yendaw University of Mines an d Technology, Dep a r t ment of Geological Engineering , Tarkwa, Ghana E-mail: js.kuma@umat.edu.gh Received September 3, 2010; revised Septem b er 30, 2010; accepted October 10, 2010 Abstract Southwest Ghana is a major gold producing region. The current high gold price has attracted hundreds of unemployed youth to undertake small-scale mining (SSM). Most of these miners operate illegally even though the SSM law (PNDCL) 218 of 1989 and Act 703 of 2006 define the procedures required for their op- eration. Some miners have brought their activities to a segment of the western highway that links southwest to central Ghana with serious environmental consequences envisaged. This paper argues that the laws that regulate SSM do not consider the fundamental set-up and concerns of the small-scale miner, hence its inabil- ity to be effective. It is therefore proposed that the present requirement that a minimum of 21 hectares is necessary before land can be registered needs re-examination. Secondly, government needs to explore par- cels of land and designate the workable areas to miners under a well structured scheme that will also educate these miners about safe and healthy mining methods. Keywords: Law, Small-Scale Mining, Regularise, Ghana 1. Introduction Ghana aboun ds in a number of minerals especially in the south-west of the country and the most developed and sought after mineral is gold. Gold mining has been asso- ciated with Ghana since time immemorial but documen- tation of this activity was captured by the Portuguese around the 1470’s [1]. Traditional Small-Scale Mining (SSM) undertaken within weathered formations has therefore been going on well before this time. Recovery of gold from these formations involved the simple tech- nology of digging, washing and recovery of the metal. Brisk trading in gold since the Portuguese set foot on Ghana earned it the name “Gold Coast” until 1957. It was reported that between 1493 and 1850, Africa pro- duced about 22 million fine ounces of gold out of which Ghana contributed approximately 60 % of the total [1]. Mechanised gold mining was first reported by the Frenchman Pierre Bonnat in 1874 in the Tarkwa ar ea and 1890 in the Obuasi area [1]. However, SSM continued to be practiced and is sometimes operated in “competition” with and within the conc essions of th e large-scale min in g companies bringing about conflicts between the two p ar- ties. The Government of Ghana, realising the importance of SSM to the economy captured how they should oper- ate in Minerals and Mining Law Act 703 [2]. Hitherto, the Minerals and Mining Law (PNDCL 153) [3] and Small-Scale Gold Mining Law (PNDCL 218) [4] were used to regulate and legalise this industry. Part of Act 703 defines the exact set-up and operational areas of the SSM but not all the operations of small-scale miners have come under the Laws. This is because the needs, concerns and activities of the group of illegal miners called “galamsey operators” who necessitated the Small- Scale Mining Laws to be enacted somehow did not ap- pear to be sufficiently captured. These illegal groups are uncontrolled and they move from one area to another digging and washing for gold and diamonds with sig- nificant impacts particularly on the land and water envi- ronments. Different estimates of the number of people involved in SSM in Ghana have been mentioned and range between 100,000 and 500,000. It has also been estimated that SSM produce about 15% or 425,000 ounces of the countr y’s gold [5 ]. I t has been reported th at *The Ghana Chamber of Mines funded this work. The authors are grate- ful.  114 J. S. KUMA ET AL. about 15,000 hectares of land has potentially been af- fected by SSM activities in the country but this figure is expected to have significantly increased now [6]. In recent times some of these illegal miners have “discovered” gold along the 100 km Tarkwa-Dunkwa highway (hereafter called “the highway”) and have brought their activities very close to the road with grave consequences envisaged. This paper is an attempt to map and catalogue the operations of these people in order to highlight the problems their activities are causing the country and discuss the consequences of a “no action” option if this is allowed to continue. Suggestions are made to bring them under regulation and therefore pre- vent degradation of the environment. 2. Physiography The area under study is located within the forest dis- sected plateau; one of five relief zones delineated in Ghana that is predominantly underlain by the Birimian and Tarkwaian Supergroups [7]. Relief in the area is typically between 240-300 m above sea level. The high- way lies almost exclusively within the Ankobra River Basin with its numerous tributaries. A double maximum rainfall regime affects the study area due to the seasonal movement of the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The main rainy season is between late April and early July with a break in August while the minor rainy season falls in September and October. In general, rain- fall decreases from Tarkwa to Dunkwa with mean annual values being 1,900 mm and 1,500 mm respectively. Mean annual temperatures increase from 26.0℃ in Tarkwa to 26.6℃ in Dunkwa while mean annual relative humidity decreases from 95% in Tarkwa to 93% in Dunkwa. The vegetation within which the highway has been built belongs to the wet semi-deciduous forest zone that previously contained the country’s timber species. Log- ging has reduced the forest cover in many areas to a secondary nature. Increased cocoa and food crop farming has exacerbated the reduction. The soils grade from ox- ysols in the Tarkwa area to forest ochrosols in the Dunkwa area [7]. 3. Regional Geology Rocks of southwest Ghana belong to the Birimian and Tarkwaian Supergroups of early Proterozoic age that have been intruded by granitoids. The Birimian is char- acterised by a series of evenly spaced, weakly metamor- phosed, tightly folded northeast trending volcanic belts separated by ‘basins’ of intervening metasedimentary/ volcaniclastic rocks (Figure 1). The metavolcanic belts are typically 15-40 km wide, between 60-90 km apart and comprise lavas of predominantly tholeiitic composi- tion, with some interflow sediments [8]. Typical litholo- gies of the basins consist of tuffaceous phyllite, schist and meta greywacke. Although traditionally, the belt rocks were believed to overlie the basin rocks, Leube et al. [8] interpreted them as a coeval sequence of lateral equivalents. Extensive isoclinal folding evident in the sedimentary basins have also been interpreted to indicate major post- Birimian crustal shortening. Tarkwaian sediments were deposited in synclinal structures within the metavolcanic belts and comprise low-grad e meta conglomerates, quart- zites and phyllites. The presence of igneous and sedi- mentary clasts derived from the Birimian and its associ- ated granitoids have led Leube et al. [8] and Junner [9] to conclude that the Tarkwaian is a detritus of Birimian rocks that were uplifted and eroded following the Ebur- nean tectono-thermal event. Although a number of structural models have been evoked to describe the deformation phases of the Birimian rocks, Eisenlohr and Hirdes [10] employed local struc- tural and isotopic data fro m the Ashanti belt to prop ose a single, progressive deformational event involving a series of deep-seated, partly-blind thrusts, possibly in a fore- land basin setting. Barritt and Kuma [11] used existing Figure 1. Simplified geological map of south west Ghana showing the belts and basins (modified from [10]. Insert shows highways in Ghana (Note particularly the Tarkwa – Dunkwa road). Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  J. S. KUMA ET AL. 115 gravity data constrained by mapped geology over the Ashanti belt to construct cross-sectional models which are consistent with the concept of a single continuous deformational event. 3.1. Geology of the Ashanti Belt The Tarkwa-Dunkwa area falls within the most impor- tant gold belt in Ghana: the Ashanti belt. All major his- toric and currently, most producing mines are located within the belt or along its highly tectonised northwest margin. Structures in the Tarkwaian rocks located in the centre of the Ashanti belt consist of a series of open, northeast plunging antiforms and synforms. Towards the western margin of the belt these folds pass into a zone of overturned strata with reverse faulting where the Tark- waian is locally overthrust by Birimian rocks. Consider- ing the gravity models generated, Barritt and Kuma [11] suggest that structures in the northwest margin are com- plex and possibly involve multiple thrust slices which control the mesothermal gold deposits in the Ashanti belt. Gold in the Ashanti belt is found in both the Birimian and Tarkwaian rocks as reef, vein or lode type deposits and as auriferous quartz-pebble conglomerates respec- tively [12]. Specifically, the veins are located near or at the contact between the metavolcanics and metasedi- ments, or as reefs of sheared and shattered smoky grey quartz within the tuffaceous phyllites in the Birimian. Weathering profiles within the Birimian and Tarkwaian rocks average 100 m and 20 m respectively and alluvial deposits derived from the two auriferous rock units are also widespread within the belt [13]. 4. Economic Activities along the Highway 4.1. Importance of the Highway This single lane road forms part of the western highway that links the Western Region to the northern part of Ghana (Figure 1, inset). Traditionally, the highway is used to transp ort people and good s: the goods are mainly timber, cocoa, shear nut, food stuffs etc., from the hin- terland to the port in Sekondi and other coastal towns. With the demise of the railway system in Ghana, the sig- nificance of the highway as the main route for transport- ing people and goods such as bauxite to and fro has be- come even more important. Heavy duty trucks; some weighing more than 60 tonnes regularly transport the goods on the highway. The civil conflict in Cote d’Ivoire has bestowed fur- ther importance on the highway as people and all manner of goods (from fuel to cattle), which were previously conveyed to and from Cote d’Ivoire to Burkina Faso and Mali through Bouake (in Cote d’Ivoire) are now diverted to pass through this highway to th eir destinations. 4.2. Agricultural Activities Farming and trading in food crops and other petty stuff are the main occupations of communities living around the highway. Cocoa is the main cash crop cultivated while the main food crops are plantain, coco yam, cas- sava and maize. The food crops are cultivated according to the seasons: that is during the rainy seasons. During the dry seasons between November and April, some of the people harvest their cocoa while others turn to allu- vial mining of gold because there is little to do by way of farming. This combination of farming and mining has been in practice for several centuries. Temeng and Abew [14] corroborates this in a recent study by stating that the major economic activities of men before large-scale mining commenced near communities in Tarkwa, Bo- gosu, Prestea and Ayanfuri are farming and SSM. 4.3. Illegal Mining Activities In the past, mining was undertaken at low levels and therefore, not overly obtrusive. However, since the eco- nomic reform programme was launched in the mid 1980’s, and massive investment in the minerals sector was undertaken, a very large part of southwest Ghana has been explored for minerals, especially gold. This has led to an awakening of rural communities to the fact that their land is potentially highly mineralised. This aware- ness, coupled with the gold boom of the nineties and the current global high gold price has influenced a number of people, especially the youth, to turn away from seasonal food crop farming and focus solely on mining gold. Secondly, the clo sure of the u ndergr ound min e in Prestea, has stressed the town and its surrounding communities. These factors, coupled with the already large youth un- employment in the country have influenced some of the youth to resort to illegal gold mining. Since anyone able to dig and wash can start mining, education is not a pre- requisite for the work. The intensity with which illegal mining is undertaken needs special attention. This is because large tracts of land, including forest reserves and other fertile farmlands have been and continue to be degraded creating water logged areas with pits serving as death traps. Addition- ally, streams and rivers are silted and contaminated with various chemicals. A very worrying recent development is that these illegal small scale miners have brought their activities to the corridor of the Tarkwa– Dun kwa highway with severe consequences envisaged. Eighteen workings Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  116 J. S. KUMA ET AL. have been recorded along the 100 km stretch of the highway up to 30 m on either side of it (Figure 2). Some of these workings have already undermined the integrity of the highway and therefore affected the safety of road users. 5. Adverse Effects of Illegal Activities along the Highway While any mining activity at a distance of 30 m or nearer the highway is a serious concern, there are some which defy reason and need special mention. The following reveal this concern: 1) About 2 km from Bawdie (Figure 2), towards Dunkwa is a hard rock shallow underground working that is tracing the more or less perp endicu lar trending ore from 100’s of meters away to the road. The surface ex- pression of the ore’s trend is acknowledged by huts un- der which access is made underground. Figure 2. The Tarkwa–Dunkwa highway showing the loca- tion of mining activities within 30 m of the road. The huts cover and protect the shallow shafts. It is very likely that the underground working has traversed the road to the opposite sid e. It is reported that more than 1000 people work in this place (Figure 3). The workings have been abandoned due to flooding which will weaken the surrounding rocks resulting in possible cave-in; fa- cilitated by vibrations induced by the heavy vehicular traffic and finally undermine the structural integrity of the road. 2) A squatter camp with a population of more than 200 people has been built along the shoulder of the road at about 300 m north of Nanankaw (Figure 4). Apart from inhibiting drainag e, the location of the camp is dangerous considering the busy nature of the highway. An accident along this section of the road can be very fatal. Some sections of the road cutting at Nsoupon Junction in the Dadieso area have been mined to depths of more than 20 m. Because of the danger this excavation poses to pedestrians in particular, the local people have fenced Figure 3. Shallow underground workings at right angles to road and likely to have traversed it. Figure 4. Squatter camp built by miners on the shoulder of the highway. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  J. S. KUMA ET AL. 117 the most dangerous parts with bamboo to prevent people falling into the pit (Figure 5). 3) The walls of this excavation are near vertical and there is a high probability th at the h ighway co uld collap se with the least disturbance, particularly during heavy downpour. The Japa-Dadieso area has the largest con- centration of illegal mine workings along the highway and their activities stretch almost continuously for more than 3 km on either side of the highway. In some areas the workings extend to more than 300 m away from the highway. It is estimated that more than 1,500 people are engaged in this area alone. In some other areas several 100 metres of the high- way’s shoulders have been dug to serve as channels to convey water to active working areas (Figure 6). In other places, water hoses have been laid in the channels to transport the water. Figure 5. A 20 m deep pit worked on the cut slope of the road at Nsoupon near Dadieso. Figure 6. A water channel used by miners to transport wa- ter to wash the ore. A large worked heap (arrowed) can be seen in the distance near to the highway. The strength of the road is slowly being undermined and its deterioration has been initiated by these kinds of activities. 4) The stability of utility lines such as electric and telephone poles located along the highway are also at risk due to these activities and large tracts of land have been destroyed by the haphazard manner in which min- ing is conducted (Figures 7 and 8). 5) Some of the miners use small rock grinding cum washing machines and few heavy digging equipment to enhance production (Figures 9 and 10). Sometimes these pieces of equipment are left on the shoulder of the high- way and become a threat to motorists (Figure 9). Often times the heavy equipment is moved on the highway, scraping and damaging its surface. Figure 7. Water logged area with electric cables overhead. Poles are in the mud. Yellow patch is a section of a large pool. Figure 8. A mini bus arrowed showing how close the work- ing is to the road. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  118 J. S. KUMA ET AL. 6. Dealing with the Issues Dzigbodi-Adjimah [15] intimated that “legalising small- scale or galamsey mining has been acclaimed an achieve- ment…but galamsey has unleashed considerable havoc onto the environment”. PNDC Law 218 [4] defines SSM as “the mining of gold by any method not involving sub- stantial expenditure by an individual or group of persons not exceeding nine in number or by a co-operative soci- ety made up of ten or more persons”. It appears the SSM sections in PNDCL 153 [3] and PNDCL 218 [4] which were captured in Minerals and Mining Act 703 [2] — were meant to regularise and control the activities of illegal mining. However, the question is whether galam- sey mining has been sufficiently captured in these laws such that they can be steered to work under the existing Law. Act 703 [2] requires among others that before any- one can operate a SSM venture in the country, a licence must be issued and the operator needs to be registered by the Office of the Minerals Commission in a designated area. An overwhelming majority of those working along the highway and in other places have no licence and are not registered and are therefore operating illegally. Th ere are two fundamental reasons for this: 1) The galamsey miner cannot handle a “block” i.e., the minimum plot of 21 hectares (1 hectare is 10,000 m2 or simply 100 m by 100 m). Although article 85(a) of Act 703 [2] says a licence can be granted to “a person, a group of persons, a cooperative society or a company…”, traditionally, these galamsey miners are unable to fit in because they work typically in groups of 4 or 5; such a group cannot afford a 21 hectare land working with shovels and small implements even though they are be- coming more sophisticated with their use of small Chi- nese made rock grinding and washing Chang Fa ma- chines (Figure 9) and occasionally hire excavators to heap ore for washing (Figure 10). While the “block” may be manageable for the high class SSM, it is certainly too large for others who typically would like to regular- ise their activities but cannot cope with a block. Al- though a number of groups can come together to form a cooperative, which may be the idea of the government, their management can be a nightmare. It has been observed that the blocks being licenced to small-scale miners are acquired by those who have capi- tal to invest and wait for some time for their investment to bring in returns. This brings about the seco nd reason. 2) There is no guarantee that the block allocated to the small-scale miner is mineralised and considering that these simple artisans cannot afford to work for days, weeks or months without any returns, they would ignore the risks that go with licencing a block and explore and immediately exploit any patch of ground they find good grade material. The phrase “not involving substantial expenditure” in the definition of SSM is relative and for the rural folk, this is meaningless because unemployment and poverty are the main reasons for going into illegal mining. Therefore, to commence SSM with 21 hectares and con- sidering the processes leading to its acquisition coupled with the fact that the block may not be productive is enough incentive for the many thousands of them to work outside the SSM law. Thus, although SSM activities have been legalised and gains have been made in opening up the mining industry to small-scale entrepreneurs the law has not made provi- sions for the legalisation of the galamsey miner. Rather the SSM scheme has empowered the middle class Gha- naian business man. This is good because this class of Figure 9. Dozens of washing machines such as this Chinese Chang Fa type are deployed. This machine was working less than 10 m from the road. Figure 10. Heavy digging equipment left on the shoulder of the road. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  J. S. KUMA ET AL. 119 entrepreneurs gives employment to some locals and con- tributes to the development of the economy. It is worth noting that most of these business men are funded by external sources that sponso r the mining activity with th e Ghanaian being a front for the operation. It must be acknowledged that youth unemployment has become a big headache for successive governments. Most of the people engaged in this type of mining con- sider it as their only source of employment and a profes- sion they have decided to engage in. It is possible to regularise their operations just as SSM has been legalised (or what the small-scale mining law was meant to achieve). Secondly, this business has become a highly lucrative enterprise. Government needs to preempt and prevent the situation of remediating destroyed lands by designing innovative schemes such as what one would call “the youth in mining initiative”. The prevention is better than cure adage needs to be applied here because the cost of remediation can be very expensive. This ini- tiative should commence on a pilot basis in a chosen community with prevalence of galamsey activities to evaluate its effectiveness and if successful replicated across the country. The initiative may be viewed in the following way: 1) Government is interested in the welfare of all youth and has taken cognisance of the desire of some to be gainfully employed and contribute to the economic growth of the country through the minerals sector. 2) Government develops to an advanced state, parcels of land with good gold grades and passes these on to people under structured supervision and education to demonstrate sequential mining of the land and its reha- bilitation to minimise all the negative outcomes associ- ated with the industry. Dzigbodi-Adjimah and Bansah [16] have estimated that the total cost for locating and evaluating an 8 km2 alluvial gold deposit on a 64 km2 concession in Ghana under 1994 conditions excluding bulk sampling and feasibility studies is US$284,013.63. Using an inflation rate of 3.5% gives a current estimate of US$475,821.90. 3) Just as parcels of land are sold or leased out for housing projects or farming, land that can be surveyed and a site plan of it made should be enough for its li- cence provided one qualifies under the law to operate. Since tens of thousands are already working illeg ally the law should permit those who have carried out “prospect- ing” in permissible areas and found the land worth ex- ploiting to be encouraged to regularise their operations. This is possible if there is no restriction on how small the land has to be. Certainly, such individuals will not have the capacity to prospect up to a block before they report their find to the appropriate authorities for registration. A provision must be made in the law for government to aid in the exploration of the area where the find is made so that the long-term viability o f the ind ividual or group can be ascertained and sustained. In this way it is also possi- ble that others can also be “given” part of the expanded and viable prospect for mining. 4) Government has shown proof of its goodwill by being interested in the health and safety of this group which may be called “Artisanal Small-Scale Miners” (ASSM). Government sets up mobile clinics with Medi- cal Assistants or Senior Nurses in charge with personnel to register ASSMs into the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in order to deal with their health needs. Registered ASSMs will be transferred to the district scheme in which they engage their operations later on. Their registration via the NHIS scheme would also en- able their actual numbers and biodata to be known. En- vironmental Officers of Government are posted to sites to educate on safe mining and environmental practices. Government also attaches personnel of Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) to the educational team to educate and register them so that they contribute towards their pension and the NHIS. 5) The period between when a registration request has been received to the time a licence is issued is carefully considered so that delays leading to frustration is pre- vented. The success of the youth in mining initiative should then lead to the promulgation of a law which specifically targets the ASSM. As this is replicated throughout min- ing areas in the country, environmental impacts fro m this activity can be minimised. As noted by Anon [6] the pri- ority issues associated with SSM are safety and welfare of those engaged in the profession, water quality degra- dation, competing land use and its rehabilitation, effi- cient resource utilisation and maximising socio-eco- nomic benefits of the local people. Drawing the ASSM towards regulating bodies through government officers so that they can be educated is adjudged the most poten- tially effective way that their activities can be controlled. This is achieved through an appropriate incentive scheme to facilitate their pull towards government. This incen- tive is the interest that gov ernment will show in the wel- fare, health and safety of the ASSM. Indeed Temeng and Abew [14] stated that 70% of a group of people inter- viewed in mining communities with in the study area said SSM is their major economic activity and this has posi- tively impacted their lives because their income levels had improved, enabling them to educate their kids, and build or renovate their houses. This is an indication of the importance these communities attach to SSM and therefore one can infer that illegal mining cannot be eradicated but at best regulated. Investigations also show that there is a general willingness among groups like Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  J. S. KUMA ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 120 sponsors, rock buyers and grinders and washers to regu- larise their activities so that they can work in peace without harassment from law enforcers. Enforcement of the law is required. The Po lice Service should be empowered to patrol and enforce the law espe- cially around national assets such as forest reserves, roads, railway lines, bridges and other structures. In the case of the highway, the cost of constructing one kilo- meter single lane, 7.5 m wide asphalt and bituminous roads is estimated at US$387,000.00 and US$50,000.00 respectively [17]. Now that the Tarkwa to Dunkwa sec- tion of the double bitumen tarred highway is under threat, and in other parts of the country similar threats are being observed due to illegal mining activities, a decisive ac- tion to at least significantly reduce their activities will cost less. Reconstruction of this highway is expected to cost more because access to the sides of the highway would have to be created for traffic to continue to flow while the road is under construction and some of these pits and water logged areas will first have to be filled and made safe . If this sector is managed properly so that the small- scale miners are educated to work in an environmentally friendly way, better methods of mining would result in better recovery and their total share of the national pro- duce could increase significantly. Taxes obtained from the ASSM could also help develop their communities. More mining and related geo-environmental scientists and engineers would also be employed by government to train and monitor the ASSM further reducing unem- ployment. The no action condition is a much more ex- pensive alternative to comprehend because illegality is tacitly endorsed in addition to the costs of replacing de- stroyed structures and remediating the environment, which certainly will far exceed the implementation of this scheme. 7. References [1] N. R. Junner, “Gold in the Gold Coast. Gold Coast Geo- logical Survey,” Memoir, Vol. 4, 1935, p. 67. [2] Anon, “Minerals and Mining Law,” Act 703 of Parlia- ment of Ghana, 2006, p. 59. [3] Anon, “Minerals and Mining Law,” PNDCL, Vol. 153, 1986, pp. 1-36. [4] Anon, “Small-Scale Gold Mining Law,” PNDCL, Vol. 218, 1989, pp. 1-5. [5] T. Aubynn, Personal communications, 2009. [6] Anon, “Environmental Impact Assessment of Small- Scale Mining in Ghana,” Final Report by NSR Environ- mental Consultants, Victoria, Australia for Minerals Commission of Ghana, 1993, p. 101 [7] K. B. Dickson and G. Benneh, “A New Geography of Ghana,” Longman, England, 1995, p. 170 [8] A. Leube, W. Hirdes, R. Mauer and G. O. Kesse, “The Early Proterozoic Birimian Supergroup of Ghana and Some Aspects of Its Associated Gold Mineralisation,” Precambrian Research, Vol. 46, No. 1-2, January 1990, pp. 139-165. [9] N. R. Junner, “Geology of the Gold Coast and Western Togoland,” Gold Coast Geological Survey Bulletin, Vol. 16, 1940, p. 40 [10] B. N. Eisenlohr and W. Hirdes, “The Structural Devel- opment of the Early Proterozoic Birimian and Tarkwaian Rocks in Southwest Ghana, West Africa,” Journal of Af- rican Earth Sciences, Vol. 14, No. 3, April 1992, pp. 313-325. [11] S. D. Barritt and J. S. Kuma, “Constrained Gravity Mod- els and Structural Evolution of the Ashanti Belt, SW, Ghana,” Journal of African Earth Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 4, May 1998, pp. 539-550. [12] G. O. Kesse, “The Mineral and Rock Resources of Ghana,” Balkema, Rotterdam, 1985, p. 615 [13] N. R. Junner, T. Hirst and H. Service, “The Tarkwa Goldfield,” Gold Coast Geological Survey Memoir, Vol. 6, 1942, pp. 48-55. [14] V. A. Temeng and J. K. Abew, “A Review of Alternative Livelihood Projects in Some Mining Communities in Ghana,” European Journal of Scientific Research, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2009, pp. 217-228. [15] K. Dzigbodi-Adzimah, “Environmental Concerns of Ghana’s Gold Booms: Past Present and Future,” Ghana Mining Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1996, pp. 21-26. [16] K. Dzigbodi-Adzimah and S. Bansah, “Current Devel- opments in Placer Gold Exploration in Ghana: Time and Financial Considerations,” Exploration and Mining Ge- ology, Vol. 4, No. 3, 1995, pp. 297-306. [17] Anon, “Cost Estimates for Asphaltic Overlay on Lagos Avenue Road,” Department of Urban Roads and High- ways, Accra, 2009, p. 4. |