Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

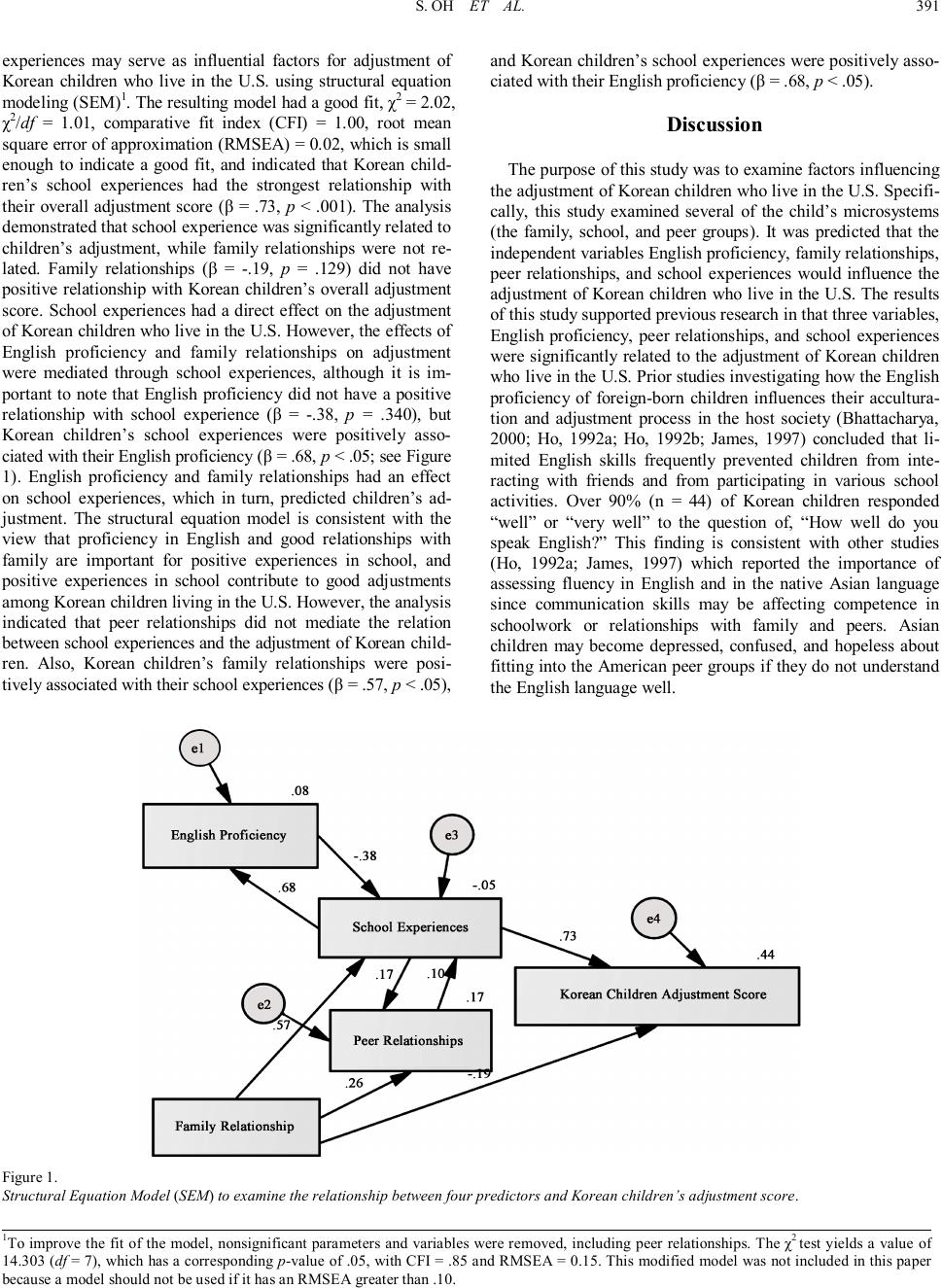

Psychology 2010. Vol.1, No.5, 386-393 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2010.15048 Structural Analysis of Factors Influencing the Adjustment Behaviors of Korean Children in the U.S Sunjin Oh1, Mack C. Shelley2 1Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Iowa State University, Ames, IA USA; 2Department of Political Science and Department of Statistics, Iowa State University, Ames, IA USA. Email: {sunjin, mshelley}@ iast ate. edu Received Sep tember 27th, 2010; revised Oct ober 2nd, 2010; accepted O ctober 9th, 2010 The purpose of this study was to identify factors influencing the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. Specifically, this study examined the following predictor variables: English proficiency, peer relationships, family relationships, and school experiences. Forty seven Korean children who were attending the Korean Lan- guage School and their parents participated in this study. Pearson product moment correlations indicated that there was a statistically significant relationship between the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. and their English proficiency, peer relationships, and school experiences. There was no statistically significant relationship between the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. and their family relationships. Ad- ditionally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was examined to explore how English proficiency, family rela- tionships, peer relationships, and school experiences may serve as influential factors for adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. The resulting model had a good fit, χ2 = 2.02, χ2/df = 1.01, comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.00, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.02, which is small enough to indicate a good fit, and indicated that Korean children’s school experiences had the strongest relationship with their overall adjustment score (β = .73, p < .001). However, the effects of English proficiency and family relationships on adjustment were mediated through school experiences, although it is important to note that English proficiency did not have a positive relationship with school experience (β = -.38, p = .340), but Korean children’s school experiences were positively associated with their English proficiency (β = .68, p < .05). Keywords: Korean Children in the U.S., Cultural Adjust ment, School Experiences, English Pr oficiency, Peer Relationships, Family Relationships Introduction Culture in a very powerful force in young children’s lives; it shapes representations of childhood, values, customs, child- rearing attitudes and practices, and family relationships and interactions. It is a pervasive force. Children’s development can be fully understood only when it is viewed in the larger cultural context (Rodd, 1996). When individuals move from their native culture to another culture, they invariably experience environ- mental and psychological stresses. Children living in the U.S. after living in another culture and society not only face the initial stress and expected adjustment problems of all children, but also face an entirely different cultural environment. These problems, including language barriers and difficulties growing out of differences related to social connections and networks such as peer relationships and interactions, can discourage children’s efforts to adapt to the new social environment and culture. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2001), approximately 1.1 million Korean Americans live in the United States. Of this number, about one-third are children and adolescents. These children may suffer from adjustment stresses in school and inadequate communication between school and parents, in ad- dition to other losses they experienced in leaving their friends, extended family, and all the familiar surroundings of their ho- meland (Kim, Kim, & Rue, 1997). Stresses faced by Korean children in an alien culture would be even greater because of their lack of English proficiency and the cultural differences between Korea and the United States (Ho, 1992a). However, many minority children are able to cope with these problems, achieve competence, and find satisfactory ways to adjust to a new cultural environment. Therefore, the concern of this study is to examine factors that are associated with the positive or negative adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. Because Chinese and Japanese have represented the largest Asian populations in the U.S., most studies of Asians in the U.S. are based on these two larger groups. There is a paucity of re- search on Koreans in general, but even scarcer is research on Korean children who live in the U.S. This study explores a topic about which very little is known. Literature Review Children’s Adjustment in the U.S. Taft (1973 as reported in Taft and Steinkalk’s 1985 study) defined adjustment as a function of the degree to which the environment fulfills a person’s needs and goals; it is reflected in feelings of satisfaction with various areas of life. When a per- son is generally satisfied with life one might expect a feeling of well-being, reflected in emotional stability, competence in dealing with the environment, and a positive self-concept. Adolescents who successfully integrate and accept their past culture with their current culture and who successfully own  S. OH ET AL. 387 their cultural roots are considered adjusted in the host society (Eshel, 2000; James, 1997). If children and adolescents can be helped to accept both cultures, they can develop an integrated sense of self (James, 1997). Vergne (1982) studied the positive adjustment of 45 for- e ign-born children ages 6 to 10 to a new school and culture. He pointed out that the child’s attitude towards school, friends and peers, and to the U.S.; maintenance of ethnic/national origin identity; and length of stay in the U.S. were all related to cul- tural adaptation. Particularly, the child’s attitudes towards friends and peers were significantly correlated with self-esteem, child’s attitude towards the U.S., and the length of stay in the U.S. Moreover, length of stay in the U.S. was correlated with the child’s school adjustment, self-esteem, attitude toward school, and home adjustment. English Proficiency When studying adjustment, it is important to assess the de- gree of English fluency because it may affect competence in schoolwork or relationships with family and peers. Lack of English proficiency exacerbates virtually every problem area of Asian Americans (Ho, 1992a). Children who are not fluent in the language of the host country may experience degrees of culture shock in the school setting; they may become depressed, confused, and hopeless about fitting into the American peer groups. James (1997) noted that even when a child has learned conversational aspects of the second language, it might take more than five years to learn those aspects of language involv- ing cognitive functioning and academic achievement. According to Canino and Spurlock (2000), lack of English proficiency is rarely considered as a cause for achievement difficulties in school, and frequently a child learning English as a second language is diagnosed incorrectly as a learning-dis- abled child; children become alienated from school when the classroom teacher points out that their linguistic style is inferior to Standard English. Cheng and Kuo (2000) said “families which cherish cultural heritage and ethnic cultural values seem more likely to require that their children preserve ethnicity by learning the family language and thus put greater pressure on minority children” (p. 465). They noted, citing Portes’s 1994b study, that first generation immigrants are usually quite loyal to their ancestral languages. However, second generation immi- grant children are often asked to speak their mother tongue at home and communicate in English outside of the family. Second generation children seem to experience more problems in family relationships and in social connections and networks. Yu and Kim (1983) suggested that social reinforcement and parental encouragement are necessary for bilingual and bicul- tural children to develop both languages in verbal and written form without apparent loss of proficiency in either language. Bi lingual children have the advantage of being able to establish a more positive ethnic self-identity and self-acceptance as well as being able to appreciate bicultural enrichment in later years. Peer Relationships Some Korean children may perceive their physical appear- ance as short and small, with black hair and black eyes, and may recognize their skin color as ugly, inferior, or shameful. This negative perception may be reinforced by peers who tease them and may have an effect on their personality and adjust- ment in an unfamiliar environment (Yu & Kim, 1983). Peer association is a common experience of children and adolescents across cultures. Social networks that children establish and maintain with peers may play a significant role in social support for children to cope with emotional stress and adjustment diffi- culties. According to Chen, Chen, and Kaspar (2001), peer sociability makes positive contributions to children’s social and emotional development and school adjustment. In contrast, peer aggression contributes to children’s learning problems and is negatively related to children’s school competence. The con- tributions of peer social functioning to children’s adjustment might be due to the direct contact and mutual influence among group members. Constant peer evaluations and reactions, based on culturally prescribed group norms and values, may serve to regulate and direct children’s behaviors, and thus affect normal developmental processes. Children who lack meaningful interactions with peers will not have the information necessary to make accurate judgments about themselves. Therefore, to acquire and refine adaptive behavior, especially in the school setting, children’s interac- tions with others are necessary (Cillessen & Bellmore, 1999). They found that children with poor peer relations (rejected and controversial children) had low self-other agreement scores. Namely, self-understanding may depend on the quality of inte- ractions and relationships with significant others. Family Relationships Korean parents tend to get involved positively in many activ- ities with their children, especially in academic areas, and will sacrifice everything to provide a good educational environment for their children. Many Korean children in the U.S. live with both biological parents, and this stable family life positively influences the children in developing growth-promoting values and emotional stability (Yu & Kim, 1983). Parental warmth and control are positively related to children’s self-image, social competence, self-regulatory abilities, and the family’s level of acculturation (Fagen, Cowen, Wyman, & Work, 1996; Gon- zales, Hiraga, & Cauce, 1995). Children who perceived their parents as warm have better social skills and more meaningful interpersonal relationships (Fagen et al., 1996). Sun (1992a), studying 83 Korean American adolescents, measured adolescents’ perceived parental control, conflict with their parents, level of adolescent’s acculturation, and many other variables. She found that the Korean adolescent’s accul- turational variables had a significant relationship with maternal control and conflict. The author assumed that the Korean- American mothers who were less acculturated than their child- ren could pressure their children to maintain aspects of the Ko- rean culture, even though Korean American fathers may em- phasize bicultural ability because most fathers were employed in American society. Kim (2002) reported that parental expectation, parents’ Eng- lish proficiency, frequency of child-parent communication, and level of home supervision was positively associated with Ko- rean children’s educational achievement and success. Interes- tingly, Korean American children who had been raised with strict home supervision, the authoritarian Korean parenting style, had higher levels of educational performance at school. Jung (2000) found that Korean American children scored  S. OH ET AL. 388 themselves higher on anxiety than Korean children and Cauca- sian American children due to a cultural “double bind” caused by the Korean cultural heritage and Americanization. This wi- dened gap and intergenerational culture clash in the values of parents and children are a psychologically painful wound among the members in immigrant families (Kibria, 2002; Sandhu et al., 1999). Immigrant Korean families are more likely to be charged wit h physical abuse in comparison with all other groups by examining child maltreatment cases reported to CPS (the child protective services) in Los Angeles County because for- e ign-born immigrant Korean parents and their American-born children may experience conflicts and misunderstandings in values and behavioral norms that can contribute to the potential risk for child maltreatment (Chang, Rhee, & Weaver, 2006). Thus, Cho and Bae (2005) suggest that it would be necessary to help Korean American parents to increase effective discip- line and monitoring practices in view of the changes in cultural values and attitudes that occur as their children acculturate into the dominant culture both expressing warmth and setting limits. School Experiences Children’s beliefs and behaviors are also influenced by school experiences. The importance of school as an institution for the socialization of children is considered by some to be second only to the family. School is “an arena where minority children first experience cultural conflict and behavioral ad- justment problems” (Ho, 1992b). The U.S. school system and teachers influence the academic achievement and behavioral adjustment of an Asian child in the new classroom environment (Ho, 1992a; James, 1997; Ryu, 2004). The impact of social change as part of the acculturation process is most likely to be experienced by foreign-born children in the school setting. Lack of acceptance by peers and teachers may foster a sense of being different (James, 1997). The teaching format designed to provide a better education for White U.S. American children was based on the American mainstream curriculum with little awareness of cultural diver- sity (Canino & Spurlock, 2000; Chiang, 2000). These authors note that teachers and parents tend to differ on specific values, such as self-direction or conformity in children’s education and guidance. Such value disparities between parents and school staff may affect the quality of their relationship and may in- crease the likelihood of interpersonal conflicts between teachers and children who come from other cultures. These conflicts, in turn, may result in lower school achievement, lower self-con- cept, and higher school dropout rates among foreign-born children (Canino & Spurlock, 2000; Ho, 1992a; Kim et al., 1997; Ryu, 2004). Ryu (2004) found that while adjusting to American schools, three Korean-English bilingual gifted children were frustrated and confused by both Korean parents and American classroom in social roles, self-concepts, and academic and social expecta- tions, and development. Korean American children are ex- pected to follow parents’ advice and guidance rather than ex- press their opinion and desire at home while U.S. classroom teachers encourage Korean American children to manage and control their behavior and feelings by themselves. Also, most Korean parents focus on their children’s academic skills such as reading and writing Korean and basic counting even before entering elementary school, rather than social and emotional development, emphasized by U.S. kindergarten teachers. There- fore, it is recommended that the classroom teachers should acknowledge and appreciate children’s home cultures as well as learn basic foreign words, offering opportunities for children to express individual and cultural differences (Canino & Spurlock, 2000; Ryu, 2004). To summarize, prior research provides sup- port for the view that the adjustment of Korean children living in the U.S. is likely to be influenced by several factors. The factors include: English language proficiency, family relation- ships, peer relationships, and school experiences. Met ho d Participants The subjects for this study were 47 Korean children from first to sixth grade and their Korean parents who lived in a midwestern university community; 43% (n = 20) were male and 57% (n = 27) were female. The children ranged from 61 to 156 months old, with mean age of 96 months; 72% (n = 34) were born in Korea and 28% (n = 13) were born in the U.S. The mean length of time in the United States was 57 months, rang- ing from 1 to 156 months; 47% (n = 22) of the children spoke Korean as their primary language at home, 38% (n = 18) spoke mostly English, and 15% (n = 7) spoke Korean and English equally at home. Also, 89% (n = 48) of the Korean children primarily spoke Korean with their parents at home and 11% (n = 5) spoke English with their parents. A summary of sample characteristics is presented in Table 1. Surveys were adminis- tered to Korean children at the Korean Language School, which they attended on Sunday (in addition to attending public schools during the week), and were sent to their parents at home via the children. All children had two Korean biological parents living at home and were collectively referred to as “Korean children,” whether they were American-born or Ko- rean-born. Measures The Adjustment Scale. The Perceived Cross-Cultural Ad- justment Scale, compiled by the investigator, incorporated items selected from four measures: (a) Desire to Reside in the Host Culture (Eshel & Rosenthal-Sokolov, 2000), (b) Child’s Self-Esteem (Simpson & McBride, 1992), (c) Depression Scale (Rumbaut, 1994), and (d) Self-Confidence (Hightower et al., 1987). The Desire to Reside in the Host Culture Scale was de- signed to investigate Russians’ subjective perceptions of ad- justment in Israel (e.g., “I feel at home in Israel”). For this study, children responded to five items (e.g., I wish to live in the U.S.) using a Likert-types scale ranging from strongly dis- agree to strongly agree in which high scores indicated that children wanted to reside in the U.S. Child’s self-esteem was derived from the Family, Friends, and Self (FFS) Assessment Scales for Mexican American Youth (Simpson & McBride, 1992). The response scale ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always) where high scores indicated high self-esteem. Depres- sion symptoms were measured with a four-item subscale from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale (Rumbaut, 1994). High scores indicated that the Korean  S. OH ET AL. 389 Table 1. Family Demographic Characteristics (N = 47) Variable % n Mean SD Range Child Characteristic Age 96 25.1 61-156 Length of stay in the U.S. 57 37.5 1-156 Gender Male 43% 20 Female 57% 27 Birth place Korea 72% 34 U.S. 28% 13 Primary language at home English 38% 18 Korean 47% 22 Bilingual 15% 7 Mothers' education Less than bachelor's degree 2% 1 Bachelor's degree 66% 31 More than bachelor's degree 32% 15 Fathers' education Less than bachelor's degree 0% 0 Bachelor's degree 9% 4 More than bachelor's degree 91% 43 Mothers' employment status Unemployed 77% 36 Employed 23% 11 children were experiencing many depression symptoms. Self- confidence, designed by Hightower et al. (1987), measured perceptions of sureness about one’s school abilities. The scale contained eight items (e.g., I like to do schoolwork) and each item in the scale was scored from usually no to usually yes. For the purposes of the current study, the perceived cross-cultural adjustment scale was revised to make it suitable for Korean children. An English Language Proficiency Index. An English lan- guage proficiency index (Rumbaut, 1994) used four items to measure the respondent’s self-reported ability to speak, under- stand, read, and write English. Each item was scored from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very well), with an overall index score calcu- lated as the mean of the four items. Peer Relationships Scale. Interpersonal Social Skills is one factor from the Child Rating Scale (CRS) (Hightower et al., 1987), which in its entirety is composed of four factors (Interpersonal Social Skills, Rule Compliance/Acting Out, Anxiety/Withdrawal, and Self-confi- dence). The Interpersonal Social Skills scale is utilized to assess perceptions of interpersonal functioning and relationships with peers. Possible responses range from strongly agree to strongly disagree with high scores indicating that children had good interpersonal social skills (α = .52). Family Relationships Scale. The Parent-Child Conflict Scale (Rumbaut, 1994) consists of 3 items, with responses ranging from 1 (very true) to 4 (not true at all). Family Warmth is a modified version of the Child’s Attitude towards Family Scale (Vergne, 1982). The seven items from the Family Warmth and Parent-child Conflict scales were combined to create an overall indicator of the children’s Per- ceptions of Family Relationships. School Experiences Scale. The School Experiences Scale (α = .79), adapted by the inves- tigator from the Family, Friends, and Self (FFS) Assessment Scales for Mexican American Youth (Simpson & McBride, 1992) contains five items with a response format ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, with high scores indicating that children had good school experiences. Additionally, a Family Demographic Data questionnaire, designed by the in- vestigator, was completed by the parents and measured the length of stay in the U.S., the primary language spoken at home, and primary speaking language with the parents at home, oc- cupation, and education. Parents were also asked to complete an 8-item questionnaire regarding their perceptions of their child’s adjustment to life in the U.S., including peer relation- ships, teacher relationships, school experiences, and language proficiency (e.g., “He /She is satisfied with his/her life in the U.S.”). Data Collecting Procedures and Anal yses This study was designed to investigate factors influencing the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. In order to carry out the objectives of this research most effectively, a non-experimental survey research design was used. It was a cross-sectional and local study in nature. The unit of analysis in this study was the Korean children from the first grade to the sixth grade in elementary school and their Korean parents. Surveys were administered to Korean children who are attend- ing the Korean Language School and were sent to their parents in the greater Lansing, MI area. Data collection began on February 9, 2003 and ended on February 23, 2003. The Adjustment scale was administered to Korean children who were attending the Korean Language School on Sunday. The investigator presented versions in two different languages (Korean and English) to aid the under- standing of the young children. The survey questions were ad- ministered individually to first and second grade students by the primary investigator. The Parent Survey Questionnaire and Family Demographic Survey were sent home to parents. De- s cri ptive statistics were used to analyze the family demographic data, such as the length of stay in U.S., parents’ educational level, and occupational status. Pearson product moment corre- lation coefficients were computed to analyze the relationship between adjustment as reported by Korean children and English proficiency, peer relationships, family relationships, and school experiences. Additionally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine how English proficiency, family relation- ships, peer relationships, and school experiences serve as in- fluential factors for adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S.  S. OH ET AL. 390 Results Relationship between Korean Children’s Adjus tment and the Predictor Variables A Pearson product moment correlation indicated a statisti- cally significant correlation between adjustment and the child- ren’s English proficiency (r = .34, p = .021). Over 90% (n = 44) of Korean children responded that they speak and understand English “well” or “very well”. Over 50% (n = 26) of Korean children scored higher than the mean score on an English Profi- ciency Index. Korean children were asked to respond to ques- tions on the Family Relationships Scale. The scale was divided into two sub-scales: Family Warmth (e.g., My parents love me a lot) and Parent-Child Conflict (e.g., I’m often in trouble with my parents because of our different ways of doing things). Even though over 50% (n = 25) of Korean children scored higher than the mean score on Family Warmth Scale, there were no significant relations between Korean children’s ad- justment score and the family relationship scores (r = .16, p = .285) and two sub-scales which were Family Warmth (r = .14, p = .344) and Parent-Child Conflict (r = .13, p = .398). Korean children who were in the upper grades (fifth and sixth grade) tended to acknowledge conflict and dissatisfaction about their family relationships. Specifically, 47% of Korean children in the upper grades had a score above the mean on the Par- ent-child Conflict scale, while 25% of Korean children in the first grade had scores above the mean on the Parent-Child Con- flict Scale. There was also a positive relationship between ad- justment and Korean children’s peer relationships (r = .30, p = .041). Korean children strongly agreed or agreed that they have a lot of American (n = 42) as well as Korean friends (n = 36). Also, they strongly agreed (28%) or agreed (55%) that they make friends easily. Surprisingly, most children in this study responded “strongly agree (49%) or “agree (40%)” to the item, “I have a lot of American friends.” Adjustment was signifi- cantly correlated with the children’s reports of school expe- riences (r = .64, p = .000). Children who reported positive school experiences tended to be well-adjusted. Of the total sample, 96% (n = 45) of Korean children in this study re- sponded “strongly agree” or “agree” to the item, “I have posi- tive relationships with teachers,” 87% and (n = 41) were satis- fied with their school achievement. Among four sub-scales in Korean children’s Adjustment scale, “Desire to reside in the U.S. (r = .37, p = .010),” “Children’s Self-Esteem (r = .54, p = .000),” and “Children’s Self-Confidence (r = .50, p = .000)” were strongly correlated with Korean children’s school expe- riences except “Children’s Depression.” School experience was positively related to English proficiency (r = .40, p = .006), peer relationships (r = .37, p = .011), and family relationships (r = 48, p = .001). Relationship between Parents’ Ratings about Their Children Adjustment and Children’s Ratings about their Adjustment Pearson correlations showed no significant relations between the parents’ ratings of the children’s adjustment and children’s adjustment completed by the children. Also, the predictor va- riables (English proficiency, peer relations, family relations, and school experiences) which were reported by the children did not have positive relations with parents’ ratings about their children adjustment. Bivariate correlations identified that the total score of the parents’ perceptions about their child’s ad- justment to the U.S. was positively and significantly related to child’s length of stay in the U.S. Parents responded that the longer children have lived in the U.S., the better they have ad- justed and acculturated in the U.S. (r = .51, p = .001). In this study, 72% of Korean children were born in Korea and 28% were born in the U.S. A t-test showed that there was a significant difference in parents’ perceptions about their child- ren’s adjustment between children who were born in Korea and children who were born in the U.S. (t = 4.1, p < .01). Parents reported that children who were born in the U.S. were better adjusted than Korea-born children. Also, a t-test identified that there was a significant difference in parents’ perceptions of their child’s adjustment to life in the U.S. between children who spoke English and children who spoke Korean with their par- ents at home. Of the total sample, 89% (n=42) of the Korean children used Korean as their primary language with their par- ents at home, and 11% (n = 5) used English as their primary language with their parents (t = 3.3, p < .01). Parents reported that children who used English as their primary language with their parents at home tended to be better adjusted in the U.S. A one-way ANOVA was used to test the differences in adjust- ment among three groups of children: those speaking primarily Korean, primarily English, or both languages at home. There was a difference among the three language groups in the par- ents’ perceptions of adjustment. Parents reported that children who were primarily speaking English tended to be better ad- justed in the U.S. this finding is presented in Table 2. Structural Equation Model of the Adjustment of Korean Children who Live in the U.S. Using Amos 18, first of all I tested a structural equation model examining the relationship between four predictor va- riables (English proficiency, family relationships, peer rela- tionships, and school experiences) and Korean children’s over- all adjustment score, depicted in Figure 1 which is a proposed model after exploring any kinds of positive relationships be- tween all of the proposed predictor factors and Korean child- ren’s overall adjustment score. I examined how English profi- ciency, family relationships, peer relationships, and school Table 2. One-way ANOVA results for parents’ perceptions about their children’s adjustment. Language Mean adjustments scores on the parents survey SD English (n = 18) 33.22 a, b 3 .1 Korean (n = 22) 30.64 3 .2 Both language (n = 7) 30.43 1.5 Groups Mean Squares df f-value Prob. Between 39 2 4.4 .02* Within 8.8 44 Note. Results of post-hoc test: a. English language group had higher adjustments scores than Korean language group; b. English language group had higher ad- justments scores than bilingual group  S. OH ET AL. 391 experiences may serve as influential factors for adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. using structural equation modeling (SEM)1. The resulting model had a good fit, χ2 = 2.02, χ2/df = 1.01, comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.00, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.02, which is small enough to indicate a good fit, and indicated that Korean child- ren’s school experiences had the strongest relationship with their overall adjustment score (β = .73, p < .001). The analysis demonstrated that school experience was significantly related to children’s adjustment, while family relationships were not re- lated. Family relationships (β = -.19, p = .129) did not have positive relationship with Korean children’s overall adjustment score. School experiences had a direct effect on the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. However, the effects of English proficiency and family relationships on adjustment were mediated through school experiences, although it is im- portant to note that English proficiency did not have a positive relationship with school experience (β = -.38, p = .340), but Korean children’s school experiences were positively asso- ciated with their English proficiency (β = .68, p < .05; see Figure 1). English proficiency and family relationships had an effect on school experiences, which in turn, predicted children’s ad- justment. The structural equation model is consistent with the view that proficiency in English and good relationships with family are important for positive experiences in school, and positive experiences in school contribute to good adjustments among Korean children living in the U.S. However, the analysis indicated that peer relationships did not mediate the relation between school experiences and the adjustment of Korean child- ren. Also, Korean children’s family relationships were posi- tively associated with their school experiences (β = .57, p < .05), and Korean children’s school experiences were positively asso- ciated with their English proficiency (β = .68, p < .05). Dis cussion The purpose of this study was to examine factors influencing the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. Specifi- cally, this study examined several of the child’s microsystems (the family, school, and peer groups). It was predicted that the independent variables English proficiency, family relationships, peer relationships, and school experiences would influence the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. The results of this study supported previous research in that three variables, English proficiency, peer relationships, and school experiences were significantly related to the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S. Prior studies investigating how the English proficiency of foreign-born children influences their accultura- tion and adjustment process in the host society (Bhattacharya, 2000; Ho, 1992a; Ho, 1992b; James, 1997) concluded that li- mited English skills frequently prevented children from inte- racting with friends and from participating in various school activities. Over 90% (n = 44) of Korean children responded “well” or “very well” to the question of, “How well do you speak English?” This finding is consistent with other studies (Ho, 1992a; James, 1997) which reported the importance of assessing fluency in English and in the native Asian language since communication skills may be affecting competence in schoolwork or relationships with family and peers. Asian children may become depressed, confused, and hopeless about fitting into the American peer groups if they do not understand the English language well. Figure 1. Structural Equation Model (SEM) to examine the relationship between four predictors and Korean children’s adjustment score. 1To improve the fit of the model, nonsignificant parameters and variables were removed, including peer relationships. The χ2 test yields a value of 14.303 (df = 7), which has a corresponding p-value of .05, with CFI = .85 and RMSEA = 0.15. This modified model was not included in this paper because a model should not be used if it has an RMSEA greater than .10.  S. OH ET AL. 392 School experiences, such as teacher relationships, school achievement and grades, was significantly related to Korean children’s adjustment in the U.S. Korean children who had good school experiences have adjusted well to their new envi- ronments. School-aged children are spending much time bond- ing with their peers and teachers at school. School adjustment is a very important factor because it may enhance their life skills and make the acculturation process easier and faster. Asian children tend to respect teachers as highly as their parents, viewing teachers as role models, as evidenced by 96% (n = 45) of Korean children responding “strongly agree” or “agree” to the item, “I have positive relationships with teachers,” while only 17% (n = 8) agreed with the item, “Some of my teachers are not very nice to me.” This finding is consistent with pre- vious studies (Bhattacharya, 2000; Ho, 1992a; James, 1997) suggesting that the impact of social change as part of the accul- turation process is most likely to be experienced by for- e ign-born children in the school setting and a lack of acceptance by peers and teachers may foster a sense of being different. In regards to peer relationships, Korean children in this study were asked to respond to items on the Interpersonal Social Skills scale, such as “I make friends easily.” There was also significant relation between adjustment and the peer relation- ships of these Korean children. Particularly, a Pearson product moment correlations showed a significant relation between adjustment and having many American friends. Having Ameri- can friends also was positively related to English proficiency and school experiences. The result indicated that making American friends was an important factor in the adjustment of Korean children. Positive peer relationships with American friends may play a pivotal role in children’s social and emo- tional development and school adjustment. Additionally, the study examined how English proficiency, family relationships, peer relationships, and school experiences may serve as influential factors for adjustment of Korean child- ren who live in the U.S. using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results of SEM showed that school experiences had a direct effect on the adjustment of these Korean children in the U.S., and that the effects of English proficiency and family relationships on adjustment were mediated through the school experiences. Children with better English skills and good fami- ly relationships tended to have better school experiences. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Kim, 2002; Okagaki & Frensch, 1995) suggesting that parental help in understand- ing school tasks, parents’ English proficiency, frequency of child-parent communication, and level of home supervision were positively associated with minority children’s educational achievement and success in school. Korean children who had better school experiences tended to be better adjusted in the U.S. That is a key finding from this study and is supported by Cani- no and Spurlock (2000), Ho (1992b), and James (1997) who found that children who are not fluent in English may expe- rience culture shock in the school setting and may be diagnosed incorrectly as learning-disabled children. Ho (1992b) noted that many Asian children’s school problems were related to lan- guage problems and emphasized that school is an arena where Asian children first experience cultural conflict and behavioral adjustment problems. L i mit ations Although this research seemed to produce significant results that could be useful when studying Korean children as well as Asia n-born children who live in the U.S., this study has some limitations which need to be taken into consideration when studying or applying the results. Because of the sampling pro- cedure, the sample is not likely to be representative of the Ko- rean children who live in the U.S. The study concentrated on the adjustment of Korean children attending a Korean language school in East Lansing, MI in the U.S. Thus, generalizations to the population of Korean children outside this environment should be limited. To obtain the most accurate information about the adjustment of Korean children who live in the U.S., a sample that reflects the heterogeneity of the Korean children in the U.S. is needed. If Korean children had been selected at random throughout the area, the results would have given a more accurate depiction of the population of Korean children who live in the U.S. The sample size of 47 subjects was rela- tively small. If the sample size were larger, there would be more power available to detect relationships among the va- riables of interest. Also, caution must be exercised in the i nter- pretation of the SEM (structural equation modeling) results based on this sma ll sample from only one Korean language school in East Lansing, MI. in generalizing. Although, the in- vestigator assessed each of the young children individually, Korean children in the lower grades (first, second, and third grades) might not have understood the meanings of some items, especially items in the Self-esteem and Self-confidence Scales. Re ferences Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. Bhattacharya, G. (2000). The school adjustment of South Asian immi- grant children in the United States. Adolescence, 35, 77-85. Canino, I. A., & Spurlock, J. (2000). The influence of culture and mul- tiple social stressors on the culturally diverse child. In I. A. Canino & J. Spurlock (Eds.), Culturally diverse children and adolescents (PP. 7-44). New York: Guilford. Chang, J., Rhee, S., & Weaver, D. (2006). Characteristics of child abuse in immigrant Korean families and correlates of placement de- cisions. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 881-891. Cheng, S. H., & Kuo, W. H. (2000). Family socialization of ethnic identity among Chinese American pre-adolescents. Journal of Com- parative Family Studies, 31, 463-484. Chen, X., Chen, H., & Kaspar, V. (2001). Group social func tioning and individual socioemotional and school adjustment in Chinese children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 47, 264-299. Chiang, L. H. (2000). Teaching Asian American students. The Teacher Educator, 36, 58-69. Cho, S. M., & Bae, S. W. (2005). Demography, psychosocial factors, and emotional problems of Korean American adolescents. Adole s- cence, 40, 533-550. Cillessen, A. H. N., & Bellmore, A. D. (1999). Accuracy of social self-perceptions and peer competence in middle childhood. Mer- rill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 650-676. Eshel, Y., & Rosenthal-Sokolov, M. (2000). Acculturation attitudes and sociocultural adjustment of sojourner youth in Israel. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140, 677-691. Fagen, D. B., Cowen, E. L., Wyman, P. A., & Work, W. C. (1996). Relationships between parent-child relational variables and child test variables in highly stressed urban families. Child Study Journal, 26, 87-108. Gonzales, N. A., Hiraga, Y., & Cauce, A. M. (1995). Observing moth- er-daughter interaction in African-American and Asian-American fam-  S. OH ET AL. 393 ilies. In H. I. McCubbin, E. A. Thompson, A. I. Thompson, & J. E. Fromer (Eds.), Resiliency in African-American families (Vol. 3, pp. 259-285). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Hightower, A. D., Cowen, E. L., Spinell, A. P., Lotyczewski, B. S., Guare, J. C., Rohrbeck, C. A., & Brown, L. P. (1987). The Child Rating Scale: The development of a socioemotional self-rating scale for elementary school children. School Psychology Review, 16, 239-255. Ho, M. K. (1992a). Asian American Children and Adolescents. In Man Keung, Ho (Ed.), Minority children and adolescents in therapy (pp. 33-54). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. Ho, M. K. (1992b). A transcultural framework for assessment and therapy with ethnic minority children and youth. In Man Keung, Ho (Ed.), Minority children and adolescents in therapy (pp. 7-29). New- bury Park, CA: SAGE. James, D. C. S. (1997). Coping with a new society: The unique psy- chosocial problems of immigrant youth. Journal of School Health, 67, 98-102. Jung, W. S. (2000, February 21-26). Cultural influences on ratings of behavioral and emotional problems, and school adjustment for Ko- rean, Korean American, and Caucasian American children. Paper presented at the National Association of African American Studies & National Association of Hispanic and Latino Studies. Houston, TX. Kim, E. J. (2002). The relationship between parental involve ment and children’s educational achievement in the Korean immigrant family. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 33, 529-540. Kim, W. J., Kim, L. I., & Rue, D. S. (1997). Korean American children. In G. Johnson-Powell & J. Yamamoto (Eds.), Transcultural child development: Psychological assessment and treatment (pp. 183-207). New York: Wiley. Kibria, N. (2002). Becoming Asian American: Second-generation Chi- nese and Korean American identities. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Okagaki, L., & Frensch, P. A. (1995). Parental support for Mex- ican-American children’s school achievement. In H. I. McCubbin, E. A. Thompson, A. I. Thompson, & J. E. Fromer (Eds.), Resiliency in Native American and immigrant families (Vol. 2, pp. 325-342). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Rodd, J. (1996). Children, culture and education. Childhood Education, 72, 325-329. Rumbaut, R. G. (1994). The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-es- teem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. In- ternational Migration Review, 28, 748-794. Ryu, J. Y. (2004). The social adjustment of three, young, high-achiev- ing Korean-English bilingual students in kindergarten. Early Child- hood Education Journal, 32, 165-171. Sandhu, D. S., Kaur, K. P., & Tewari, N. (1999). Acculturative expe- rien ces of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans: Considerations for counseling and psychotherapy. In D. S. Sandhu (Ed.). Asian and Pa- cific Islander Americans: Issues and concerns for counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 3-19). Commack, NY: Nova Science. Sun, C. K. (1992a). Korean-American adolescents: Parent-child rela- tion s hip. Long Beach, CA: California State University. Simpson, D. D., & McBride, A. A. (1992). Family, friends, and self (FFS) assessment scales for Mexican American youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 14, 327-340. Taft, R., & Steinkalk, E. (1985). The adaptation of recent soviet immi- grants in Australia. In I. R. Lagunes & Y. H. Poortinga (Eds.), From a different perspective: Studies of behavior across cultures (pp. 19-28). Acapulco, Mexico: Swets & Zeitlainger B.V. U.S. Bureau of the Census. (2001). Statistical abstract of the United Sta tes. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Vergne, A. R. (1982). A study of the positive adjustment of foreign born children to a new school and culture. Unpublished doctoral disserta- tion, Michigan State University, East Lansing. Yu, K. H., & Kim, L. I. C. (1983). The growth and development of Korean-American children. In G. J. Powell (Ed.), The psychosocial development of minority group children (pp. 147-158). New York: Brunner/Mazel. |