Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

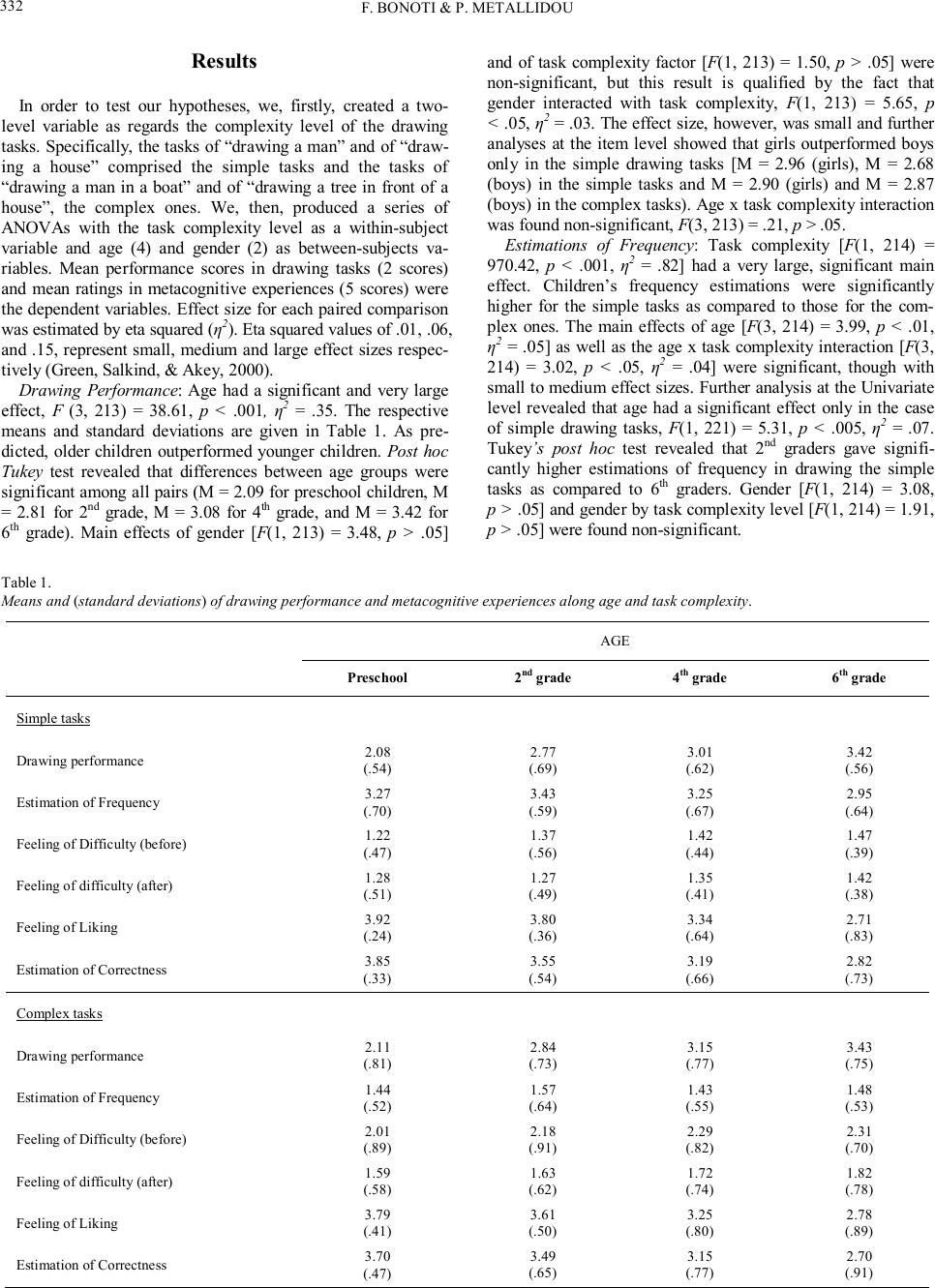

Psychology 2010. Vol.1, No.5, 329-336 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2010.15042 Children’s Judgments and Feelings about Their Own Drawings Fotini Bonoti1, Panayiota Metallidou2 1Department of Preschool Education, University of Thessaly, Thessaly, Greece; 2Shcool of Psychology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessalon ik i, Greece. Email: fbonoti@uth.gr Received September 30th, 2010; revised November 18th, 2010; accepted No vember 19th, 2010. The aim of the present study was to investigate possible age differences in drawing performance of preschool and primary school children, as well as in metacognitive experiences that are activated before and after the drawing process. The study is comprised of 222 children of both genders, aged from 4 to 12. They were tested individually in their schools. They were asked to produce four drawings, which vary on their level of complexity, and to rate before each drawing on a four-point scale the frequency of drawing similar themes and their feeling of difficulty. After the drawing they were asked to estimate again the difficulty they felt as well as the feeling of liking the drawing they produced and the correctness of the drawing. The results of a series of analyses of va- riance confirmed the expected improvement of drawing performance with age. There wasn’t found, however, the same developmental course in the case of metacognitive experiences. On the contrary, there was found a signif- icant decrease in the feeling of liking and the estimation of correctness of the drawings, especially after the second grade. Keywords: Children’s Drawing, Metacogn itive Experiences Introduction In general, children’s drawings have been investigated from an adult’s perspective (Thomas & Silk, 1990). Little is known about children’s evaluation of their own pictorial productions and that of others. Children's subjective experiences regarding their own drawings is a topic largely neglected in the research literature. While it is considered difficult from a methodologi- cal point of view to study children's verbal reactions to draw- ings (Freeman, 1980), such an investigation may be promising. Only a limited body of research has attempted to investigate children’s understanding of the developmental changes that emerge in their drawings (Cox & Hodsoll, 2000; Thyphon & Montagnero, 1992). In this research tradition emphasis was placed on children’s ‘diachronic thinking’, that is children’s understanding about the way their drawings change as the drawer gets older. Another body of research attempted to investigate children’s judgments about drawings (Hart & Goldin-Meadow, 1984; Itskowitz, Glaubman, & Hoffman, 1988; Taylor & Bacharach, 1981). These attempts can be characterized more as studies involving selection tasks in which children were asked to choose the ‘best’ drawing, rather than studies examining child- ren's actual thoughts or preferences about drawings. Therefore, they do not provide sufficient evidence about the relationship between children’s own efforts and their subjective experiences. For example, the data concerning whether children are satisfied with their own drawings are controversial. Some researchers claim that children are satisfied with their own drawings (Brooks, Glenn, & Crozier, 1988; Moore, 1986; Taylor & Ba- charach, 1981), while others suggest that children prefer draw- ings that they fail to produce; that is, depictions which are de- velopmentally advanced (Goodnow, Wilkins, & Dawes, 1986; Hart & Goldin-Meadow, 1984; Itskowitz et al., 1988). In addi- tion, contradictory evidence comes from past studies based on observation. Some studies report that children are satisfied with their own drawings (Hurlock & Thomson, 1934) while others report that they are not (Mann & Lehman, 1976). In a more recent study, Jolley, Knox and Foster (2000) used a selection task in order to investigate the relationship between children’s production and comprehension of realism in draw- ings. They argued that the controversial findings of previous studies were probably due to the ambiguous instructions given to children (to choose the “best” drawing of an array of draw- ings). In order to avoid the possible confusion of emotional and cognitive components that such an instruction implies, they attempted to give more precise instructions. More specifically, they attempted to investigate children’s comprehension of real- ism (‘which drawing looks most like a real object’), preference (‘which do you like the most’) and estimation of their own drawing ability (‘which looks most like your drawings’). Mo- reover, they used as selection stimuli children’s actual drawings and not the adult versions of children’s pictorial representations that previous researchers have incorporated in their studies. They found that children preferred more advanced drawings than the ones they could produce themselves and that young drawers overestimated their skills in contrast to older subjects who gave more accurate self-evaluations. A similar finding is also reported by Golomb and Helmund (1987) who attempted to explore preschoolers’ attitudes toward their drawings, through the investigation of their thoughts and feelings about the activity, the medium and the mode of repre- sentation. They found that regardless of the medium (paints or crayons) used, children were satisfied with their own produc- tions. For example, most children seemed surprised when asked about altering something in their drawing. Further, when asked if there was anything they could do to make it better, only a few children accepted that they could improve it. Similar results  F. BONOTI & P. METALLIDOU 330 were obtained by Sullivan’s study as cited in Golomb (1992) with six- and seven year olds, who claimed that they would not make alterations in their drawings. Attempting to interpret young children’s unwillingness to re- vise their drawing, Golomb (1992) suggested that there is a relative stability in a child’s drawing style. She argued that young children tend to repeat the satisfying graphic schemas and to perfect them gradually. This interpretation reminds van Sommers’ (1983) ‘graphic conservatism’, a term proposed to describe children’s tendency to repeat established visual for- mulas: once a drawing strategy has been acquired, further de- velopment most usually takes the form of adding detail and embellishing the drawing rather than revising its basic form. The above mentioned gradual improvement of drawings led to explanations of drawing development which imply the in- volvement of subjective experience during the drawing process. For example, it has been suggested that “something inside the child induces change” (Cox, 1992. p. 47). In other words, changes in drawing can be regarded as positive, self-motivated actions in an attempt to produce better pictorial representations. Moreover, Willats (1995) suggested that the process of drawing development could be seen as a result of a series of interactions between production and the child’s perception of his/her own depictions. According to him, children change their drawings in order to get them to look better. One stage persists until the child becomes displeased with the drawing system he currently uses, considering it as an insufficiently good representation. Consequently, he adopts a new denotation system, which again results in a drawing that does not look correct. The whole de- velopmental process goes on, following the same pattern. This child-task interaction has recently gained a lot of inter- est among researchers in the research tradition of metacognition. There is a growing body of empirical evidence as regards children’s subjective experience when they are confronted with the demands of specific tasks. In this tradition subjective expe- rience has been studied through metacognitive experiences (Efklides, 2001, 2006; Efklides & Vauras, 1999; Flavell, 1979). Following Flavell’s influential distinction between metacogni- tive knowledge and metacognitive experiences, metacognitive experiences consist of online metacognitive knowledge, ideas, and feelings the child experiences as the task processing goes on. They emerge before, during, and/or after a cognitive enter- prise and have a dual character, both cognitive and affective. Metacognitive feelings are affectively charged and vary along the scale of pleasant-unpleasant (Efklides, 2001, 2006). Exam- ples are the feeling of liking (Asghar, 1987), of familiarity (Whittlesea, 1993), of difficulty (Efklides, Papadaki, Papanto- niou, & Kiosseoglou, 1997, 1998; Touroutoglou & Efklides, 2010), and of satisfaction with the solution produced (Efklides & Petkaki, 2005; Metallidou & Efklides, 1998). Metacognitive judgments are cognitive in nature. They serve the monitoring function during the cognitive processing, such as the estimate of correctness of the solution and of frequency of previous en- counters with similar problems. They can also serve the control function, such as the estimate of the amount of effort needed in order to cope with the demands of the task (Koriat & Levy-Sadot, 1999; Nelson, 1993). Metacognitive experiences, thus, are a kind of an intrinsic feedback for the system (Efklides & Dina, 2004). Their relation with cognitive performance is small and in most cases indirect, since they are influenced not only by task features (e.g., task difficulty or previous expe- riences with the task) (Akama, 2007) but by cognitive ability and motivational factors (e.g., test-anxiety, need to achieve, and self-concept) as well. They reflect, thus, a personal interpreta- tion of the current task or the achievement situation, since they are the products of a dynamic interplay between the task de- mands and the person’s cognitive and motivational resources to meet these demands (Akama, 2006). Despite the increasing interest in investigating the nature and formation of metacognitive experiences as well as their relation to cognitive performance, the extant evidence is limited in do- mains of thought that are clearly related to problem-solving and school performance, such as performance in mathematics, physics, and language (Dermitzaki & Efklides, 2001; Efklides, et al., 1997, 1998; Gonida, Kiosseoglou, & Psillos, 2003). Moreover, the sample in most studies is mainly young adoles- cents (students in the first grades of secondary school) and few studies examine the formation of metacognitive experiences in primary school children (Metallidou, 2003) and preschool children (Gonida, Efklides, & Kiosseoglou, 2003). As regards the development of metacognitive experiences, they do not follow the same developmental pattern with cogni- tive abilities. As mentioned above, they constitute complex, subjective constructs (Dermitzaki & Efklides, 2001; Efklides, Samara, & Pertopoulou, 1999; Metallidou & Efklides, 1998) and the strength of the effect of age on metacognitive expe- riences depends on the type of the task and its objective diffi- culty (Gonida, Efklides, & Kiosseoglou, 2003). In general, young children tend to overestimate the correctness of their perfor mance and they usually refer low feelings of difficulty and high feelings of confidence (Gonida, Efklides, & Kios- seoglou, 2003; Metallidou, 2003). As children get older, their self-evaluations become more accurate since they are familia- rized with the demands of various tasks and receive feedback from their own performance and from the evaluations of signif- icant others (Eccles, Wigfield, Harold, & Blumenfeld, 1993; Newman & Wick, 1987; Phillips & Zimmerman, 1990; Stipek & MacIver, 1989). The Present Study Research on metacognitive experiences is still a growing re- search area (Efklides, 2001, 2002b, 2006), while evidence re- garding children’s own reports on their drawing ability is lim- ited (Golomb & Helmund, 1987; Jolley et al., 2000). The focus of the present study was to provide empirical evidence for the development of metacognitive experiences in the domain of drawing. We believe that such research could extend our knowledge about the formation of subjective experience and the mechanism that gives rise to it. As far as we know, the domain of drawing has not been studied yet within the research tradi- tion of metacognition. Further, current approaches in this do- main emphasize the importance of the drawing process, imply- ing thus the significant role of subjective experience. We ex- amined preschool and primary school children, that is, children aged 4 to 12 years. During this period children produce repre- sentational drawings and present an increasing drawing ability as their age increases (Cox, 1992; Jolley, 2010; Luquet, 1913; Piaget & Inhelder, 1956). We used drawing tasks that varied in their level of complexity; that is, tasks requiring the depiction of (a) a familiar object and (b) the spatial arrangement of two  F. BONOTI & P. METALLIDOU 331 objects in a scene. As regards metacognitive experiences, we included feelings and estimates which were evoked before and after the produc- tion of each drawing. Specifically, children were asked to esti- mate before each drawing (a) the frequency of drawing similar tasks and (b) their feeling of difficulty of the task, while after the drawing (c) again their feeling of difficulty, (d) the estimate of correctness of each drawing, and finally, (e) their feeling of liking the drawing they had produced. Feeling of difficulty was included in both phases since ac- cording to previous empirical data (Efklides, 2002b; Efklides et al., 1999) is a very dynamic feeling, the intensity of which changes in a micro-level during cognitive processing. Also, it is a very crucial aspect of subjective experience during self-regu- lation in achievement settings since it stands at the junction of monitoring and control processes. On the one hand, it monitors the lack of processing fluency and informs the person about the interruption of cognitive processing. On the other hand, when this processing is interrupted, it triggers control decisions, such as increasing effort expenditure or the application of the proper strategies (Alter, Oppenheimer, Epley, & Eyre, 2007; Tourou- toglou & Efklides, 2010). In accordance with the existing research evidence, we hy- pothesized that children’s drawing performance would improve with age (Hypothesis 1). Metacognitive experiences, however, would not be expected to follow the same developmental pat- tern, since they were found to be affected by the type of the tasks and their level of complexity (Hypothesis 2). Specifically, the respective age differences were not expected to be as large as in the case of performance, since, according to previous evi- dence, very young children tend to overestimate the correctness of their performance and to report high feelings of satisfaction and low feelings of difficulty in achieving the task (Gonida, Efklides, & Kiosseoglou, 2003). The improvement of perfor- mance, however, as the age increases, is accompanied with more positive estimates of correctness and feelings of satisfac- tion as well as with lower feelings of difficulty in completing the task (Metallidou & Efklides, 1998). It was expected, then, whenever there was an age-related difference, for older children to report lower feelings of difficulty and higher feelings of lik- ing and estimates of frequency and correctness as compared to younger ones. Further, the feeling of difficulty was expected to differentiate between the two phases (before and after the drawing) (Hypothesis 3). Finally, it was expected that the level of task complexity would affect children’s metacognitive expe- riences, (Hypothesis 4). Specifically, they would report higher estimates of frequency and of correctness as well as higher feelings of liking and lower feelings of difficulty regarding the simple tasks as compared to their reports for the complex tasks. Met ho d Participants 222 preschool and primary school children participated in the study aged from 4 to 12 years. 40 preschool children, 69 second grade, 65 fourth grade, and 48 sixth grade students. Gender was about equally represented in the sample (Girls = 100 and Boys = 122). Schools were located at the city of Volos in Greece. Task and Procedure Drawing Tasks All children were tested individually in their school. They were asked to complete four different drawing tasks. Precisely, they were asked to depict two simple favorite topics (“a man” and “a house”) and two scenes in which one of the objects was partially occluded by another (“a man inside a boat” and “a tree in front of a house”). For each drawing task the child was given a white sheet of paper and a pencil. Metacognitive Experiences They were measured before and after each drawing task. Be- fore each drawing children were asked to rate on a four-point scale (1: not at all, 2: a little, 3: some, 4: very) first, the fre- quency of drawing similar themes (e.g., how often do you draw people?) and, second, their feeling of difficulty (e.g., how diffi- cult do you think it is to draw a man?). After the drawing they were asked to estimate again the difficulty they had felt (e.g., how difficult was it to draw the man?) as well as the feeling of liking the drawing they had produced (e.g., how much do you like the drawing you did?) and the correctness of this drawing (e.g., how correct do you think you have drawn the man?). Scoring Criteria of Drawings Each drawing task was assessed using a 1-4 scale of assess- ment. The scoring criteria used in the present study were de- rived from previous empirical data which propose a concrete developmental pattern in the depiction of the topics under ex- amination (Cox, 1992; DiLeo, 1983; Freeman, 1980; Moore, 1986). More explicitly, in the “man” task a score of 1 was ad- ministered when a tadpole figure – that depicts a circle to which the limbs are attached – or the stick-figure was drawn, a score of 2 was given when a conventional figure in which the limbs were represented with single lines was drawn, a score of 3 when the conventional figure was drawn with limbs depicted with double lines and a score of 4 was given when the man was drawn with a continuous outline. In the “house” task a score of 1 was administered when the main schema of the house was drawn, a score of 2 when the defining features of the house were depicted inappropriately (that is the windows attached to the sides or the chimney perpendicular to the roof), a score of 3 when the above mentioned features were depicted correctly and a score of 4 was given for the three-dimensional depiction of the house. In the “man inside a boat” task a score of 1 was administered when the whole body of the man was depicted inside the boat, a score of 2 was given for a transparency draw- ing that is when the body or/and the legs of the man could be seen through the boat, a score of 3 when the man was depicted standing on the boat and a score of 4 when the man was drawn inside the boat in a visually realistic way. In the “tree in front of a house” task a score of 1 was administered when the tree and the house were arranged side by side, a score of 2 when the two objects were depicted vertically on the scene, a score of 3 when a transparency was produced (i.e. the house could be seen through the tree) and a score of 4 was given when the partial occlusion drawn scene was visually realistic. All of the drawings produced were scored independently by two judges, using the above mentioned scoring criteria. Agree- ment between the two raters ranged from 90 to 96 percent.  F. BONOTI & P. METALLIDOU 332 Results In order to test our hypotheses, we, firstly, created a two- level variable as regards the complexity level of the dra wing tasks. Specifically, the tasks of “drawing a man” and of “draw- ing a house” comprised the simple tasks and the tasks of “drawing a man in a boat” and of “drawing a tree in front of a house”, the complex ones. We, then, produced a series of ANOVAs with the task complexity level as a within-subject variable and age (4) and gender (2) as between-subjects va- riables. Mean performance scores in drawing tasks (2 scores) and mean ratings in metacognitive experiences (5 scores) were the dependent variables. Effect size for each paired comparison was estimated by eta squared (η2). Eta squared values of .01, .06, and .15, represent small, medi um and large effect sizes respec- tively (Green, Salkind, & Akey, 2000). Drawing Performance: Age had a significant and very large effect, F (3, 213) = 38.61, p < .001, η2 = .35. The respective means and standard deviations are given in Table 1. As pre- dicted, older children outperformed younger children. Post hoc Tukey test revealed that differences between age groups were significant among all pairs (M = 2.09 for preschool children, M = 2.81 for 2nd grade, M = 3.08 for 4th grade, and M = 3.42 for 6th grade). Main effects of gender [F(1, 213) = 3.48, p > .05] and of task complexity factor [F(1, 213) = 1.50, p > .05] were non-significant, but this result is qualified by the fact that gender interacted with task complexity, F(1, 213) = 5.65, p < .05, η2 = .03. The effect size, however, was small and further analyses at the item level showed that girls outperformed boys only in the simple drawing tasks [M = 2.96 (girls), M = 2.68 (boys) in the simple tasks and M = 2.90 (girls) and M = 2.87 (boys) in the complex tasks). Age x task complexity interaction was found non-significant, F(3, 213) = .21, p > .05. Estimations of Frequency: Task complexity [F(1, 214) = 970.42, p < .001, η2 = .82] had a very large, significant main effect. Children’s frequency estimations were significantly higher for the simple tasks as compared to those for the com- plex ones. The main effects of age [F(3, 214) = 3.99, p < .01, η2 = .05] as well as the age x task complexity interaction [F(3, 214) = 3.02, p < .05, η2 = .04] were significant, though with small to medium effect sizes. Further analysis at the Univariate level revealed that age had a significant effect only in the case of simple drawing tasks, F(1, 221) = 5.31, p < .005, η2 = .07. Tukey’s post hoc test revealed that 2nd gr aders gave signifi- cantly higher estimations of frequency in drawing the simple tasks as compared to 6th graders. Gender [F(1, 214) = 3.08, p > .05] and gender by task complexity level [F(1, 214) = 1.91, p > .05] were found non-significant. Table 1. Means and (standard deviations) of drawing performance and metacognitive experiences along age and task complexity . AGE Preschool 2nd grade 4th grade 6th grade Simple tasks Drawing performance 2.08 (.54) 2.77 (.69) 3.01 (.62) 3.42 (.56) Estimation of Frequency 3.27 (.70) 3.43 (.59) 3.25 (.67) 2.95 (.64) Feeling of Difficulty (before) 1.22 (.47) 1.37 (.56) 1.42 (.44) 1.47 (.39) Feeling of difficulty (after) 1.28 (.51) 1.27 (.49) 1.35 (.41) 1.42 (.38) Feeling of Liking 3.92 (.24) 3.80 (.36) 3.34 (.64) 2.71 (.83) Estimation of Correctness 3.85 (.33) 3.55 (.54) 3.19 (.66) 2.82 (.73) Complex tasks Drawing performance 2.11 (.81) 2.84 (.73) 3.15 (.77) 3.43 (.75) Estimation of Frequency 1.44 (.52) 1.57 (.64) 1.43 (.55) 1.48 (.53) Feeling of Difficulty (before) 2.01 (.89) 2.18 (.91) 2.29 (.82) 2.31 (.70) Feeling of difficulty (after) 1.59 (.58) 1.63 (.62) 1.72 (.74) 1.82 (.78) Feeling of Liking 3.79 (.41) 3.61 (.50) 3.25 (.80) 2.78 (.89) Estimation of Correctness 3.70 (.47) 3.49 (.65) 3.15 (.77) 2.70 (.91)  F. BONOTI & P. METALLIDOU 333 Feelings of Difficulty before drawing: Only task complexity factor had a significant and large main effect [F(1, 214) = 187.67, p < .001, η2 = .47]. The main effect of age, gender and the interactions between these factors and task complexity fac- tor were found non-significant. All the participants reported higher feelings of difficulty in completing the complex drawing tasks, irrespective of their age and/or gender. Feelings of Difficulty after drawing: Task complexity factor had again a significant and large main effect [F(1, 213) = 53.23, p < .001, η2 = .20]. All the participants reported higher feelings of difficulty for the complex drawing tasks, irrespective of their age. Again no other main effects or interactions between factors were found significant. A series of repeated measures ANOVAs with the drawing phase (before and after the production of the drawing) as a within-subject variable and age (4) and gender (2) as be- tween-subjects variables revealed a significant, large effect of the drawing phase only in the case of the complex tasks, F(1, 213) = 74.86, p < .001, η2 = .26. Feelings of difficulty were decreased after the drawing of the complex themes in all four age groups (M = 2.17 and M = 1.68 the mean ratings before and after the drawing, see also Table 1). The effect of drawing phase was non-significant in the case of the simple tasks, F(1, 213) = 1.42, p > .05 [M = 1.36 and M = 1.33 the respective mean ratings]. Feeling of Liking: Age had a significant and very large effect, F(3, 212) = 40.73, p < .001, η2 = .36. The older the children the lower feelings of liking their drawings they reported. Applica- tion of Tukey’s post hoc comparison test showed that the dif- ferences among ages groups were significant in all but one case, that of between preschoolers and second grade school children. These two age groups gave significantly higher estimations of liking the drawings they produced as compared to 4th grade children and those from the 6th grade children. No other main effects or interactions were found significant. Estimation of correctness: The same pattern in the ratings was found. The main effect of age was significant and very large, F(3, 213) = 27.12, p < .001, η2 = .27. Following the same pattern, the older children judged their drawings as less correct (again the difference wasn’t significant between preschoolers and second graders). There was also a significant small effect of task complexity factor F(1, 213) = 4.82, p < .05, η2 = .02. As expected, correctness estimations were lower in the case of complex tasks. Dis cussion The aim of the present study was to investigate possible age differences in drawing performance of preschool and primary school children, as well as in metacognitive experiences that are activated before and after the drawing process. To summarize, all the findings mentioned above could be considered complementary to previous research evidence. Spe- cifically, as regards drawing performance, the results verified our first hypothesis about the improvement of drawing perfor- mance with age, which is rather common evidence (Cox, 1992; Freeman, 1980; Moore, 1986). A similar developmental pattern did not appear in the case of metacognitive exper i ences, as expected (Hypothesis 2), repeating, thus, previous findings, which suggest that the metacognitive experiences seem to form their own “system”, with close interrelations between them, and to have a different developmental course as compared to that of cognition (Efklides et al., 1997, 1998, 1999; Johnson, Sacuzzo & Larson, 1995; Metallidou, 2003). The differential contribu- tion of age to the metacognitive experiences tested in this study is another indication that subjective experiences seem to “func- tion according to different laws and express the personal trans- formation of information and personal sense of things” (Ef- klides, 1997. p. 113). Starting from the feeling of difficulty, it was not found to vary significantly among the four age groups. The finding that even young children (e.g., preschoolers) do not judge the com- pletion of the tasks as difficult, contradicts those researchers who suggest that even the drawing of a man presents a number of problems - related to planning and sequencing – which the child encounters and must overcome (Freeman, 1980; Thomas & Silk, 1990). However, it might be possible that the child confronts these problems in his/her first efforts to depict the man, while familiarization with the task helps him to acquire a well-practiced graphic schema, which does not present any particular difficulties, at least at the subjective level. It is noticeable, though, that children differentiated the feel- ings of difficulty in accordance to the task’s level of complexity, reporting higher feelings of difficulty for the complex drawing tasks than for the simple ones, irrespective of age (see Hypo- thesis 4). This finding implies that even very young children are aware of the demands of various tasks, that is, they are sensitive to task features, which contribute to the cognitive load of the task. It is also in accordance with the view that every drawing task presents difficulties, which the child must confront. These difficulties are related to the child’s planning and organizing skills (Freeman, 1980; Goodnow, 1977; Thomas & Silk, 1980) or memory capacity (Dennis, 1992; Freeman, 1980; Morra, 1995). Moreover, these difficulties are greater in tasks includ- ing the spatial arrangement of two objects in the scene – as in the partial occlusion tasks used in the present study – which require that the child revises and modifies an adequate well-practiced schema (Bonoti, 1993; Karmilof f -Smith, 1990) in order to produce a successful representation (the case of the complex tasks in our study). In this case an increased feeling of difficulty could arise due to the cognitive interruption which occurs when the available schema fails to confront task re- quirements (Touroutoglou & Efklides, 2010). The feeling of difficulty was also found to be a dynamic feeling, which intensity changes in a micro-level during the cognitive processing, a finding in accordance with previous empirical data (Efklides, 2002b; Efklides et al., 1999) (Hypo- thesis 3). In the present study, children changed their feelings of difficulty of the task only after drawing the complex themes. It seems that they based their initial feeling of difficulty on their frequency estimates of previous encounters with the task. From a metacognitive point of view, “illusions of feeling of difficul- ty”, that is judging an objectively difficult task as easy and the opposite, could occur because of a strong feeling of familiarity the person may have for a task. This feeling of familiarity usually leads to an expectation of fluency in processing (Ef- klides, 2002a) and is interrelated with frequency estimates of previous encounters with the task. The lack of significant differentiation in the feeling of diffi- culty among different ages in the present study may be due to  F. BONOTI & P. METALLIDOU 334 the scale used to measure these feelings. Inspection of the mean reports in Table 1 shows that children gave low reports by us- ing only the two first points of the scale (1: not at all and 2: a little). Moreover, given that the feeling of difficulty depends on the objective task difficulty and the intensity of effort expendi- ture (Johnson et al., 1995) we are not in a position to know the way children handle specific obstacles in the drawing process as well as the amount of effort they invest and the strategies they activate to overcome these obstacles along with develop- ment. We believe that future research on the effort expenditure during the drawing process will shed more light to the forma- tion of the feeling of difficulty. A similar pattern is observed in the results concerning the es- timations of frequency. In this case, children irrespective of age give higher frequency estimations for the simple tasks as com- pared to the complex ones. These reports also support the view that the “man” and the “house” constitute children’s most pop- ular drawing choices (Cox, 1992; Thomas & Silk, 1980). One of the most interesting findings of the present study was that of gradual decrease of the feeling of liking and the estima- tion of correctness of the drawn product with age, contrary to our expectations (Hypothesis 2). This finding could partly sup- port the claim that occupation and enjoyment in drawing de- clines with age (Rose, Jolley, & Burkitt, 2006). Further, it is complementary to previous empirical data for young children’s tendency to overestimate the correctness of their performance (Gonida, Efklides, & Kiosseoglou, 2003; Metallidou, 2003). As children get older, they judge their drawings as less correct and therefore they feel less satisfied with their drawings. As their age increases their self-evaluations may become more accurate since they are familiarize with the demands of various tasks and receive feedback on their own performance and from the evalu- ations of significant others (Eccles et al., 1993; Newman & Wick, 1987; Phillips & Zimmerman, 1990; Stipek & MacIver, 1989). This finding is also reported by Jolley et al. (2000) who found that young drawers overestimated their drawing skills while the older ones tended to give more accurate s elf-evaluations. According to the authors, “the decline of overestimation with age is not owning to children becoming more negative, as claimed by previous literature, but more realistic” (Jolley et al., 2000. p. 576). In our study, the results suggest that the less positive attitude towards the drawing begins after the 2nd grade. The developmental course of these subjective experiences provide empirical evidence which verify Willat’s (1995) ac- count of drawing development, which suggests an interaction during the drawing process between child’s performance and judgment of the emerging drawing. Young children having already acquired a well-practiced (Karmiloff-Smith, 1990) and satisfactory (Golomb, 1992; Golomb & Helmund, 1987) gra- phic schema for the depicted object judge their depiction as correct and, thus, feel satisfied. On the other hand, by the age of 8 (students of 2nd grade) children start to be more demanding and seem to perceive that their drawing does not consist a rea- listic representation of the world. In other words, it seems that as perceptions become more discriminating, confidence in the ability to draw decreases (Hurlock and & Thomson, 1934). Ac- cording to the traditional theories of drawing development (Luquet, 1913; Piaget & Inhelder, 1956), children of eight years and older go through the stage of ‘visual realism’ in which they attempt to draw taking into account perspective, proportion and distance, that is drawing from a particular point of view. How- ever, drawing is not considered to have a crucial role in the school curriculum in most Western societies (Anning, 2002; Thomas & Silk, 1990) and therefore older children fail to achieve the effects they desire in their drawings and to produce visually realistic representations. As a result, older children abandon drawing activity and replace it by the use of language as a medium of self-expression (Arnheim, 1969). A possible question for future research is whether children’s feelings and estimates about the quality of their own perfor- mance reflects their real subjective experience or the preference for the norm or the ideal in a particular culture. For instance it has been reported (Goodnow et al., 1986) that the evaluative comments adults make about children’s drawings may influ- ence children to prefer conventional forms of depiction. In oth- er words, children’s estimation that adults consider some draw- ings as ‘good’ or as ‘better’ than others, may affect their prefe- rences and their subjective evaluations. Moreover, Itskowitz et al. (1988) suggested that the preference for realism among older children might have its origins in learned social norms. In their study older children frequently asked for clarifications as to whether they should choose the pictures they liked or the pic- tures that other people would like. Many studies in the late 60s about pedagogical methods in schools have mentioned the so- cial emphasis on realism in drawing (Arnheim, 1969; Kellogg, 1970), while Anning (2002) based on some case studies stressed the role that significant others might play in children’s drawing. In a more recent study (Rose et al., 2006) while teachers and parents reported their unconditional encourage- ment to children’s drawing efforts, children seemed to interpret this encouragement as an indirect urge to produce visually rea- listic drawings. Overall, the present study seems to support that drawing de- velopment does not simply consist of obtaining greater profi- ciency in making realistic representations, but also of changes in a child’s evaluation about its own depictions. Taking into account that there is always the possibility that the interpreta- tion of children’s drawings may mirror the adults’ way of thinking, it seems important to explore children’s self-reports about their own drawings in order to investigate whether their drawing strategies reflect those reported in experimental re- search (Freeman, 1980; Thomas & Silk, 1990). In other words, the investigation of children’s subjective experiences of their own drawings might prove a very rewarding line of research, since children’s self-concept of their own drawing ability could be a valuable alternative way to investigate children’s draw- ings. Finally, from a metacognitive point of view, further research on the formation and development of metacognitive experiences in the area of drawing could provide new insights in the inves- tigation of the mechanism that triggers various cognitive and affective subjective states that are related to control decisions during the processing of cognitive tasks. Drawing tasks could be considered as tasks with high ecological validity, the com- pletion of which at the same time requires a certain amount of strategic processing, such as planning and organizing. Re ferences Akama, K. (2006). Relations among self-efficacy, goal setting, and me-  F. BONOTI & P. METALLIDOU 335 tacognitive experience in problem solving. Psychological Reports, 98, 895-907. Akama, K. (2007). Previous task experience in metacognitive expe- rience. Psychological Reports, 100, 1083-90. Alter, A. L., Oppenheimer, D. M., Epley, N., & Eyre, R. N. (2007). Overcoming intuition: Metacognitive difficulty activates analytic reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136, 569-576. Anning, A. (2002). Conversations around young children’s drawing: The impact of the beliefs of significant others at home and school. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 21, 197-208. Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual thinking. London: Faber & Faber. Asghar, I-N. (1987). Cognitive and affective causes of interest and liking. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 120-130. Bonoti, F. (2003). Factors facilitating children’s drawing: The paradigm of partial object occlusion [in Greek]. Psychology: The Journal of Hellenic Psychological Society, 10, 119-135. Brooks, M. R., Glenn, S. M., & Crozier, W. R. (1988). Pre-school children's preference for drawings of a similar complexity to their own. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 57, 165-171. Cox. M. V. (1992). Children’s drawings. London: Penguin. Cox, M. V., & Hodsoll, J. (2000). Children’s diachronic thinking in relation to developmental changes in their drawings of the human figure. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18, 13-24. Dennis, S. (1992). Stage and structure in the development of children's spatial representations. In R. Case (Ed.), The mind’s staircase: Ex- ploring the conceptual underpinnings of children’s thought and knowledge (pp. 229-245). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Dermitzaki, I., & Efklides, A. (2001). Age and gender effects on stu- dents’ evaluations regarding the self and task-related experiences in mathematics. In S. Volet & S. Jarvela (Eds.), Motivation in learning contexts: Theoretical advances and methodological implications (pp. 271-293). Amsterdam: Elsevier. DiLeo, J. H. (1983). Interpreting children’s drawings. New York: Bru- nner/Mazel. Eccles, J., Wigfield, A., Harold, R., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self and task perceptions during ele- mentary school. Child Development, 64, 830-847. Efklides, A. (1997). Brain and mind: The case of subjective experience. Psychology:The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 4, 106-117. Efklides, A. (2001). Metacognitive experiences in problem solving: Metacognition, Motivation, and Self-Regulation. In A. Efklides, J. Kuhl, & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Trends and prospects in motivation research (pp. 297-323). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer. Efklides, A. (2002a). Feelings as subjective evaluations of cognitive processing: How reliable they are? Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 9, 163-184. Efklides, A. (2002b). The systematic nature of metacognitive expe- riences : Feelings, judgments, and their interrelations. In M. Izaute, P. Chambres, & P-J. Marescaux (Eds.), Metacognition: Process, func- tion and us (pp. 19-34). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer. Efklides, A. (2006). Metacognition and affect: What can metacognitive experiences tell us about the learning process. Educational Research Review, 1, 3-14. Efklides, A., & Dina, F. (2004). Feedback from one’s self and others: Their effect on affect. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 1, 179-202. Efklides, A., Papadaki, M., Papantoniou, G., & Kiosseoglou, G. (1997). The effects of cognitive ability and affect on school mathematics performance and feelings of difficulty. American Journal of Psy- chology, 110, 225-258. Efklides, A., Papadaki, M., Papantoniou, G., & Kiosseoglou, G. (1998). Individual differences in feelings of difficulty: The case of school mathematics. European Journal of Psychology of Education, XIII, 207-226. Efklides, Α., & Petkaki, C. (2005). Effects of mood on students’ meta- cognitive experiences. Learning and Instruction, 15, 415-431. Efklides, A., Samara, A., & Petropoulou, M. (1999). Feeling of diffi- culty: An aspect of monitoring that influences control. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 14, 461-476. Efklides, A., & Vauras, M. (Guest eds.) (1999). Metacognitive expe- riences and their role in cognition (Special issue). European Journal of Psychology of Education, XIV (4). Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 906-911. Freeman, N. H. (1980). Strategies of representation in young children. London: Academic Press. Gardner, H. (1980). Artful scribbles: The significance of children's drawings. New York: Basic Books. Golomb, C. (1992). The child’s creation of the pictorial world. Berke- ley, CA: University of California Press. Golomb, C., & Helmund, J. (1987). A study of young children’s aes- thetic sensitivity to drawing and painting. Paper presented at the symposium on Facets or Artistic Development, Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Baltimore. Gonida, E., Efklides, A., & Kiosseoglou, G. (2003). Feelings of diffi- culty and confidence during preschool and early school age: Their relations with performance and image of cognitive self [in Greek]. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 10, 515-537. Gonida, E., Kiosseoglou, G., & Psillos, D. (2003). Metacognitive ex- periences in the domain of physics: Developmental and educational aspects. In D. Psillos, P. Kariotoglou, V. Tselfes, E. Hatzikraniotis, G. Fassoulopoulos, & M. Kallery (Eds.), Science education research in the knowledge-based society (pp. 107-115). Dordrecht, The Nether- lands: Kluwer. Goodnow, J. J. (1977). Children's drawings. London: Fontana. Goodnow, J. J., Wilkins, P., & Dawes, L. (1986). Acquiring cultural forms: Cognitive aspects of socialization illustrated by children's drawings and judgments of drawings. International Journal of Beha- vioral Development, 9, 485-505. Green, S. B., Salkind, N. J., & Akey, T. M. (2000). Using SPSS for Windows: Analyzing and Understanding Data (2nd ed.). Upper Sad- dle River: Prentice-Hall. Johnson, N. E., Saccuzzo, D. P., & Larson, G. E. (1995). Self-reported effort versus actual performance in information processing para- digms. The Journal of General Psychology, 122, 195-210. Jolley, R. P. (2010). Children and pictures: Drawing and understand- ing. West Sussex, U.K.: Wiley – Blackwell. Jolley, R. P., Knox, E. L., & Foster, S. G. (2000). The relationship between children’s production and comprehension of realism in drawing. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18, 557-582. Hart, L. M., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (1984). The child as a nonegocen- tric art critic. Child Development, 55, 2122-2129. Hurlock, E. B., & Thomson, J. L. (1934). Children’s drawings: An experimental study of perception. Child Development, 5, 127-138. Itskowitz, R., Glaubman, H., & Hoffman, M. (1988). The impact of age and artistic inclination on the use of articulation and line quality in similarity and preference judgments. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 46, 21-34. Ka rm iloff-Smith, A. (1990). Constraints on representational change: Evidence from children’s drawing. Cognition, 34, 57-83. Kellogg, R. (1970). Analyzing children’s art. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing. Koriat, A., & Levy-Sadot, R. (1999). Processes underlying metacogni- tive judgements. Information-based and experience-based monitoring of one’s own knowledge. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual Process Theories in Social Psychology (pp. 483-502). New York: Guilford. Luquet, G. H. (1913). Les dessins d’ un enfant. Paris: Alcan. Mann, B.S., & Lehman, E.B. (1976). Transparencies in children's hu- man figure drawings: A developmental approach. Studies in Art Education, 18, 41-48. Metallidou, P. (2003). Motives, language performance, and metacogni- tive experiences in a text-comprehension task [in Greek]. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 10, 538-555. Metallidou, P., & Efklides, A. (1998). Affective, cognitive, and me-  F. BONOTI & P. METALLIDOU 336 tamnemonic effects on correctness estimation and feeling of satisfac- tion during problem solving [in Greek]. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 5, 53-70. Moore, V. (1986). The relationship between children's drawings and preferences for depictions of a familiar object. Journal of Experi- mental Child Psychology, 42, 187-198. Morra, S. (1995). A neo-Piagetian approach to children's drawings. In C. Lange-Kuttner & G. V. Thomas (Eds.), Drawing and looking: Theoretical approaches to pictorial representation in children (pp.93-106). Hemel Hemstead, UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Nelson, T. O. (1993). Judgments of learning and the allocation of study time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 122, 269-273. Newman, R. S., & Wick, P. L. (1987). Effect of age, skill, and perfor- mance feedback on children’s adjustment of confidence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 115-119. Phillips, D. A., & Zimmerman, M. (1990). The developmental course of perceived competence and incompetence among competent chil- dren. In R. Sternberg & J. Kolligian, (Eds.), Competence considered (pp. 41-66). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1956). The child’s conception of space. Lon- don: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Rose, S. E., Jolley, R. P., & Burkitt, E. (2006). A review of children’s, teachers’ and parents’ influences on children’s drawing experience. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 25, 341-349. Stipek, D., & Maclver, D. (1989). Developmental change in children’s assessment of intellectual competence. Child Development, 60, 521- -538. Taylor, M., & Bacharach, V. R. (1981). Constraints on the visual accu- racy of drawings produced by young children. Journal of Experi- mental Child Psychology, 34, 311-329. Thomas, G. V., & Silk, A. Μ. J. (1990). An introduction to the psy- chology of children’s drawings. Hemel Hemstead, UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Touroutoglou, A., & Efklides, A. (2010). Cognitive interruption as an object of metacognitive monitoring: Felling of difficulty and surprise. In A. Efklides & P. Misailidi (Eds.), Trends and prospects in meta- cognition research (pp. 171-208). New York: Springer. Tryphon, A., & Montangero, J. (1992). The development of diachronic thinking on children: Children’s ideas about changes in drawing skills . International Journal of Behavioural Development, 14, 411- 424. Van Sommers, P. (1983). The conservatism of children's drawing stra- tegies: At what level does stability persist? In D. Rogers & J.A. Slo- boda (Eds.), The acquisition of symbolic skills (pp. 65-70). New York: Plenum Press Willats, J. (1995). An information-processing approach to drawing de- velopment. In C. Lange-Kuttner & G. V. Thomas (Eds.), Drawing and looking: Theoretical approaches to pictorial representation in ch ildren (pp. 27- 43). Hemel Hemstead, UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Whittlesea, B. W. A. (1993). Illusions of familiarity. Journal of Ex- perimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19, 1235-1253. |