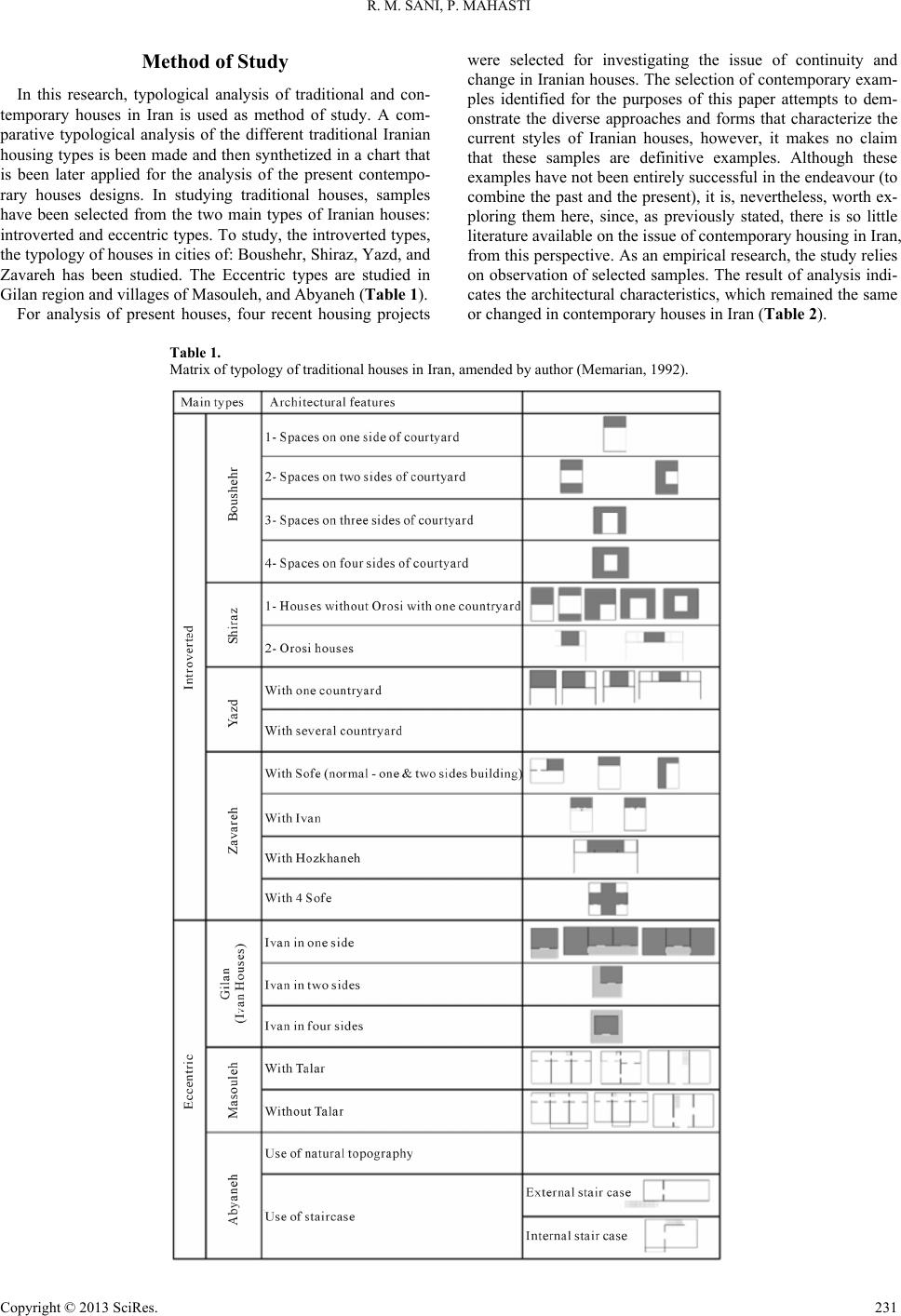

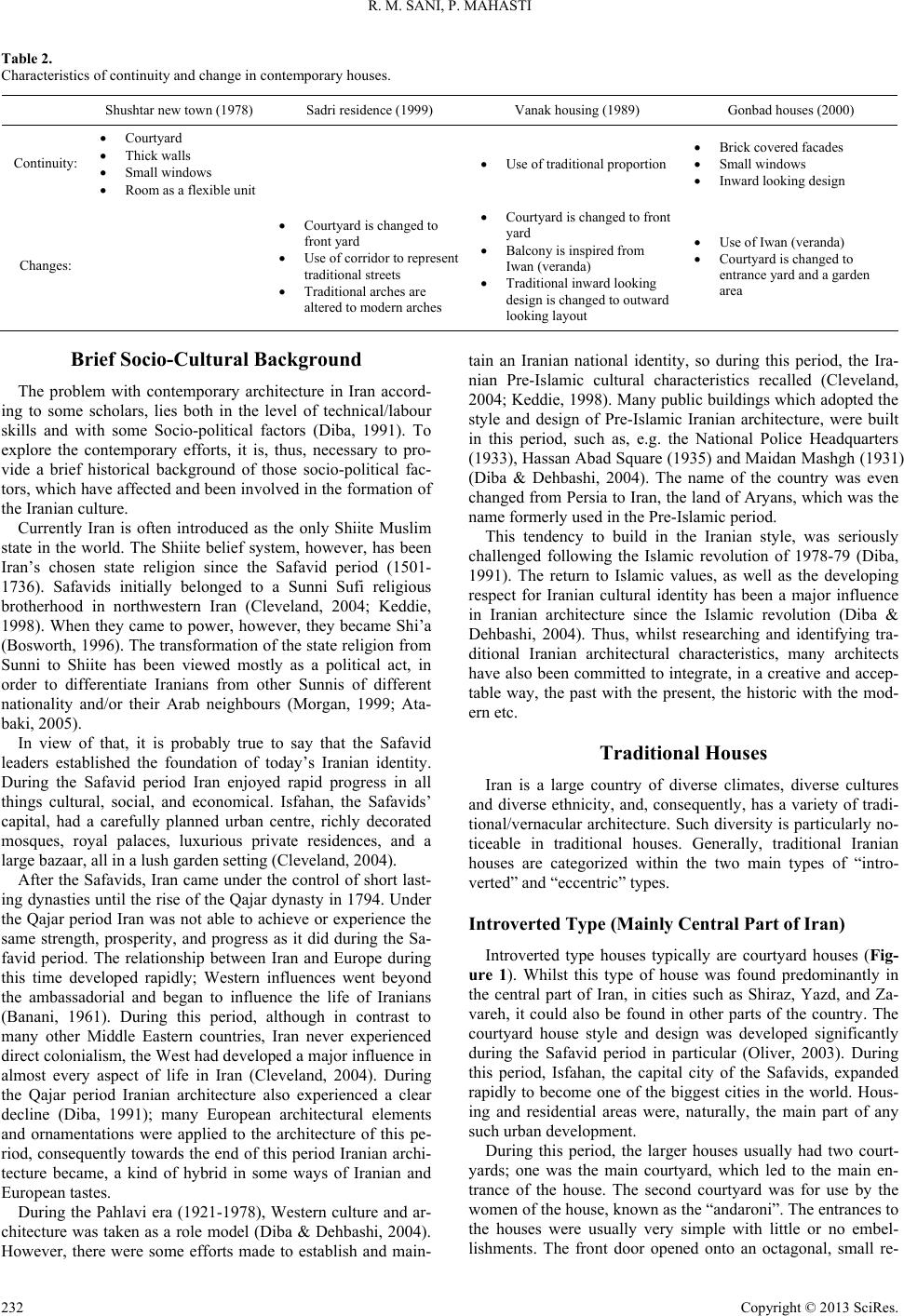

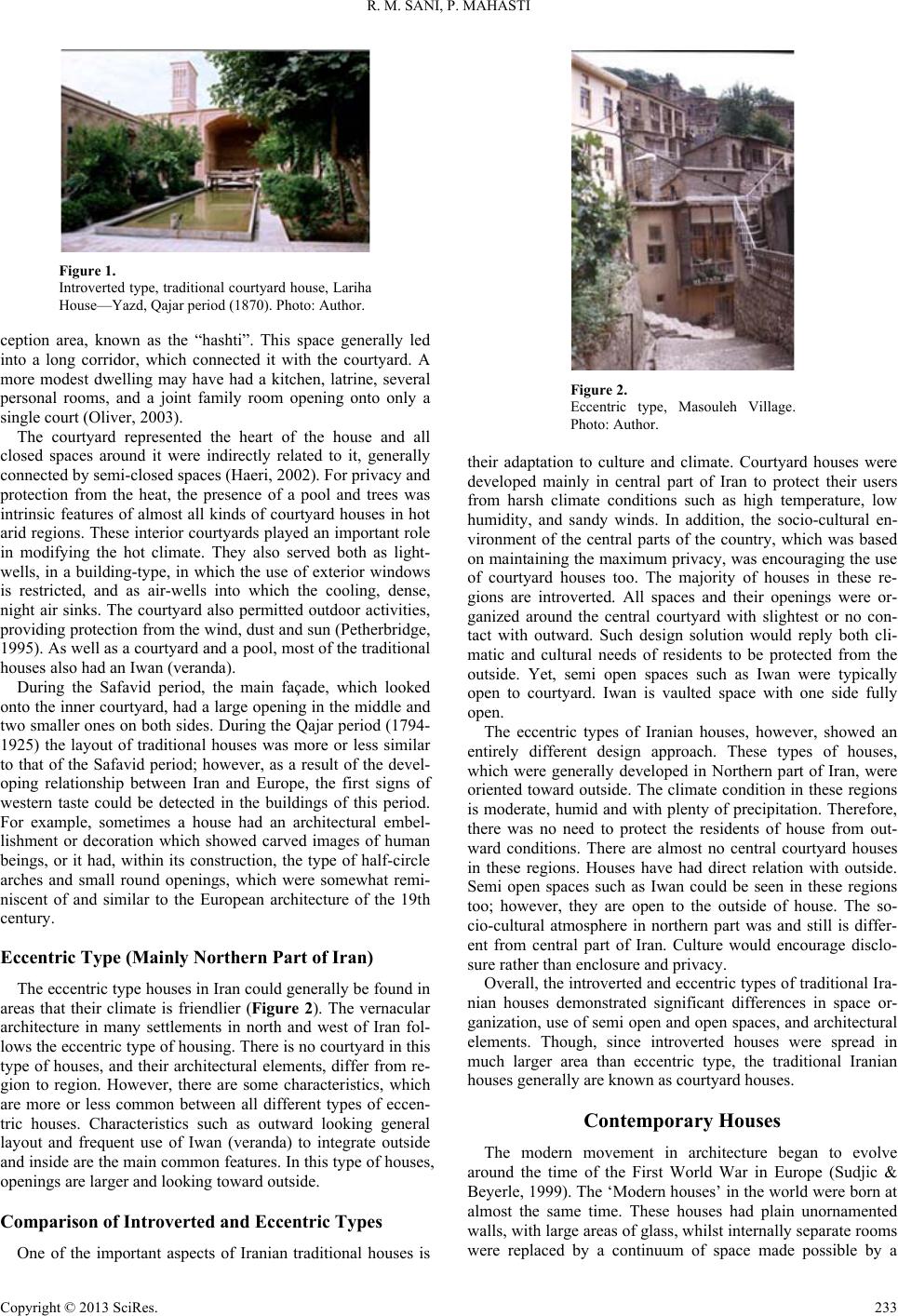

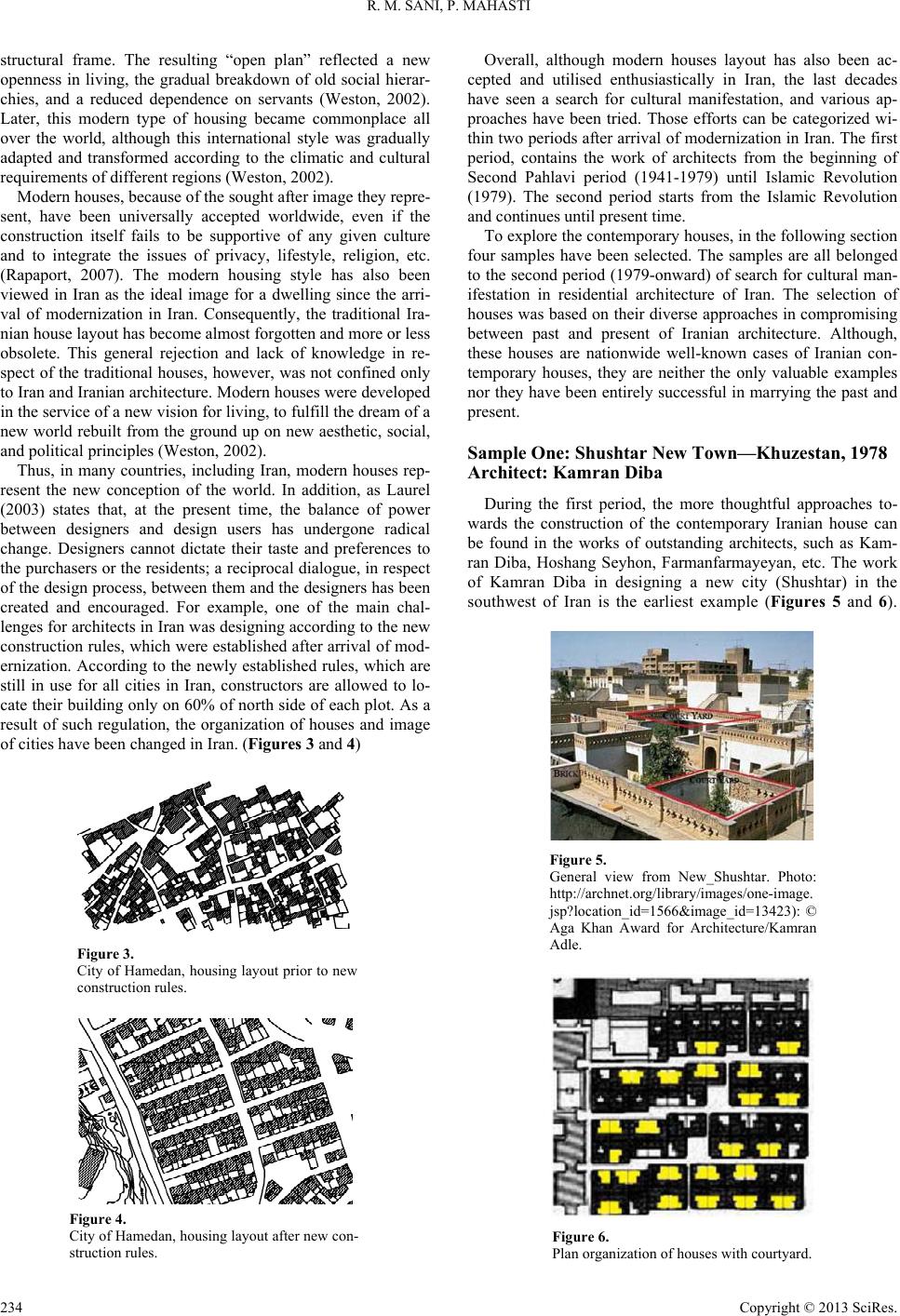

Sociology Mind 2013. Vol.3, No.3, 230-237 Published Online July 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/:10.4236/sm.2013.33031 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 230 An Inquiry into Cultural Continuity and Change in Housing: An Iranian Perspective Rafooneh Mokhtarshahi Sani, Payam Mahasti Department of Archite ct u re, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, North Cyprus Email: r.mokhtar shahi@emu.edu.tr Received March 3rd, 2013; revised April 26th, 2013; accepted May 11th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Rafooneh Mokhtarshahi Sani, Payam Mahasti. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is pr operly cited. The arrival of modernization has had an adverse effect on current Iranian housing architecture; as such, that it is now finds itself in a difficult predicament. Therefore, various national architectural conferences, in addition to individual investigations, have been focused on the renewal of Iranian housing architecture over recent decades. Whilst these examples have not culminated or resulted in defining a clear Iranian trend and style in housing with recognizable characteristics, it would be useful to explore some of the more successful examples in order to obtain an overview of what has been done in Iran in this respect during recent years. Accordingly, the study has focused on identifying the architectural characteristics of Iranian houses, which have been modified and used in the present designs. In this study, through a com- parative typological analysis of the different traditional Iranian housing types, their main characteristics have been categorized. The categorization later applied for the analysis of the contemporary houses de- signs. The results of this investigation have shown that, in contemporary samples, although the idea of Iranian traditional houses has remained; the concept of traditional houses has been altered and changed. Keywords: Housing Typology; Identity; Cultural Continuity; Iran Introduction In the field of architecture, housing has always played an important role in respect of defining cultural values, providing a sense of belonging and in the issue of self-esteem. In the con- temporary architecture of developing countries, however, these significant considerations have often been neglected. The ad- vent of modernization, the accompanying rapid changes, the ever increasing migration from the villages to the cities, and the urgent need for more housing to accommodate the migrant population left little time and/or opportunity to give sufficient thought to the aesthetic issue of ensuring that new buildings were built in such a way as to include and demonstrate aspects or features of the traditional architecture. Thus, invariably, not only have the new building materials and technology been adopted from modern Western architecture, but the architec- tural design has also been imported As a result of these practices, most new buildings, including housing, demonstrate almost no sense of connection to or of be- longing to the Iranian culture. During recent years, however, as a result of the gradual awareness and recognition of the prob- lem of detachment from traditional values and the resultant consequences, of this strenuous efforts have been made towards the revival of some cultural and architectural concepts. Such tendencies, however, have not been limited to Iran. In fact, as Lin (2002) states, the shift of the intellectual emphasis from modernity (homogenizing processes of cultural imperialism and Westernization) to post-modernism (fragmented global cultural transformation processes) has been important in developing countries. In addition, the concept of regional identity has al- ways had positive implications, partly because of the implicit assumption that it connects and brings people and places to- gether, and provides people with shared “regional values” and improved “self-confidence” (Passi, 2002). Those considerations are especially important in the current housing arena since, as Rapaport (2007) states, identity, social relations, status and the like, have become more varied, flexible, and dynamic. Consequently, researching and examining traditional regional values and identifying cultural manifestations in the country’s architecture has been one of the major aims of Iranian architects during recent decades. Such an investigation is especially help- ful in the field of housing studies, since there is a general lack of literature and/or academic interest or research being carried out in the field of contemporary housing in Iranian architecture. According to Lawrence (2005), residential buildings are con- structed in order to meet a wide range of requirements. Thus, the monitoring of the characteristics of housing objectives and preferences over time is one of the most important aspects in the construction of housing. The aim, therefore, of this study is to analyze how the design of the general house type has changed in Iran over recent years. In attempting to establish the common ground required to marry the traditional values with contemporary needs, it is nec- essary to research, identify, and describe those architectural productions, which demonstrate the combined regional, tradi- tional, and contemporary needs and values. At the same time, it is necessary to outline some general definitions that apply to traditional Iranian houses. Then through a comparative analysis, the architectural characteristics, which have changed or contin- ued to live in present designs, will be addressed.  R. M. SANI, P. MAHASTI Method of Study In this research, typological analysis of traditional and con- temporary houses in Iran is used as method of study. A com- parative typological analysis of the different traditional Iranian housing types is been made and then synthetized in a chart that is been later applied for the analysis of the present contempo- rary houses designs. In studying traditional houses, samples have been selected from the two main types of Iranian houses: introverted and eccentric types. To study, the introverted types, the typology of houses in cities of: Boushehr, Shiraz, Yazd, and Zavareh has been studied. The Eccentric types are studied in Gilan region and villages of Masouleh, and Abyaneh (Table 1). For analysis of present houses, four recent housing projects were selected for investigating the issue of continuity and change in Iranian houses. The selection of contemporary exam- ples identified for the purposes of this paper attempts to dem- onstrate the diverse approaches and forms that characterize the current styles of Iranian houses, however, it makes no claim that these samples are definitive examples. Although these examples have not been entirely successful in the endeavour (to combine the past and the present), it is, nevertheless, worth ex- ploring them here, since, as previously stated, there is so little literature available on the issue of contemporary housing in Iran, from this perspective. As an empirical research, the study relies on observation of selected samples. The result of analysis indi- cates the architectural characteristics, which remained the same or changed in contemporary houses in Iran (Table 2). Table 1. Matrix of typology of tr a d itional houses in Iran, amended by author (Memarian, 1992). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 231  R. M. SANI, P. MAHASTI Table 2. Characteristics of continuity and change in contemporary houses. Shushtar new town (1978) Sadri residence (1999) Vanak hous ing (1989) Gonbad hou ses (2000) Continuity: Courtyard Thick walls Small windows Room as a flexible unit Use of traditional proportion Brick covered facades Small windows Inward looking desi g n Changes: Courtyard is change d to front yard Use of corridor to represent traditional streets Traditional arche s are altered to modern arches Courtyard is changed to front yard Balcony is inspired from Iwan (veranda) Traditional inward looking design is changed to outward looking layout Use of Iwan (veranda) Courtyard is change d to entrance yard and a garden area Brief Socio-Cultural Background The problem with contemporary architecture in Iran accord- ing to some scholars, lies both in the level of technical/labour skills and with some Socio-political factors (Diba, 1991). To explore the contemporary efforts, it is, thus, necessary to pro- vide a brief historical background of those socio-political fac- tors, which have affected and been involved in the formation of the Iranian culture. Currently Iran is often introduced as the only Shiite Muslim state in the world. The Shiite belief system, however, has been Iran’s chosen state religion since the Safavid period (1501- 1736). Safavids initially belonged to a Sunni Sufi religious brotherhood in northwestern Iran (Cleveland, 2004; Keddie, 1998). When they came to power, however, they became Shi’a (Bosworth, 1996). The transformation of the state religion from Sunni to Shiite has been viewed mostly as a political act, in order to differentiate Iranians from other Sunnis of different nationality and/or their Arab neighbours (Morgan, 1999; Ata- baki, 2005). In view of that, it is probably true to say that the Safavid leaders established the foundation of today’s Iranian identity. During the Safavid period Iran enjoyed rapid progress in all things cultural, social, and economical. Isfahan, the Safavids’ capital, had a carefully planned urban centre, richly decorated mosques, royal palaces, luxurious private residences, and a large bazaar, all in a lush garden setting (Cleveland, 2004). After the Safavids, Iran came under the control of short last- ing dynasties until the rise of the Qajar dynasty in 1794. Under the Qajar period Iran was not able to achieve or experience the same strength, prosperity, and progress as it did during the Sa- favid period. The relationship between Iran and Europe during this time developed rapidly; Western influences went beyond the ambassadorial and began to influence the life of Iranians (Banani, 1961). During this period, although in contrast to many other Middle Eastern countries, Iran never experienced direct colonialism, the West had developed a major influence in almost every aspect of life in Iran (Cleveland, 2004). During the Qajar period Iranian architecture also experienced a clear decline (Diba, 1991); many European architectural elements and ornamentations were applied to the architecture of this pe- riod, consequently towards the end of this period Iranian archi- tecture became, a kind of hybrid in some ways of Iranian and European tastes. During the Pahlavi era (1921-1978), Western culture and ar- chitecture was taken as a role model (Diba & Dehbashi, 2004). However, there were some efforts made to establish and main- tain an Iranian national identity, so during this period, the Ira- nian Pre-Islamic cultural characteristics recalled (Cleveland, 2004; Keddie, 1998). Many public buildings which adopted the style and design of Pre-Islamic Iranian architecture, were built in this period, such as, e.g. the National Police Headquarters (1933), Hassan Abad Square (1935) and Maidan Mashgh (1931) (Diba & Dehbashi, 2004). The name of the country was even changed from Persia to Iran, the land of Aryans, which was the name formerly used in the Pre-Islamic pe riod. This tendency to build in the Iranian style, was seriously challenged following the Islamic revolution of 1978-79 (Diba, 1991). The return to Islamic values, as well as the developing respect for Iranian cultural identity has been a major influence in Iranian architecture since the Islamic revolution (Diba & Dehbashi, 2004). Thus, whilst researching and identifying tra- ditional Iranian architectural characteristics, many architects have also been committed to integrate, in a creative and accep- table way, the past with the present, the historic with the mod- ern etc. Traditional Houses Iran is a large country of diverse climates, diverse cultures and diverse ethnicity, and, consequently, has a variety of tradi- tional/vernacular architecture. Such diversity is particularly no- ticeable in traditional houses. Generally, traditional Iranian houses are categorized within the two main types of “intro- verted” and “ecc e ntric” types. Introverted Type (Mainly C e ntral Part of Iran) Introverted type houses typically are courtyard houses (Fig- ure 1). Whilst this type of house was found predominantly in the central part of Iran, in cities such as Shiraz, Yazd, and Za- vareh, it could also be found in other parts of the country. The courtyard house style and design was developed significantly during the Safavid period in particular (Oliver, 2003). During this period, Isfahan, the capital city of the Safavids, expanded rapidly to become one of the biggest cities in the world. Hous- ing and residential areas were, naturally, the main part of any such urban development. During this period, the larger houses usually had two court- yards; one was the main courtyard, which led to the main en- trance of the house. The second courtyard was for use by the women of the house, known as the “andaroni”. The entrances to the houses were usually very simple with little or no embel- lishments. The front door opened onto an octagonal, small re- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 232  R. M. SANI, P. MAHASTI Figure 1. Introverted type, traditional courtyard house, Lariha House—Yazd, Qajar perio d (1870). Photo: Author. ception area, known as the “hashti”. This space generally led into a long corridor, which connected it with the courtyard. A more modest dwelling may have had a kitchen, latrine, several personal rooms, and a joint family room opening onto only a single court (Oliver, 2003). The courtyard represented the heart of the house and all closed spaces around it were indirectly related to it, generally connected by semi-closed spaces (Haeri, 2002). For privacy and protection from the heat, the presence of a pool and trees was intrinsic features of almost all kinds of courtyard houses in hot arid regions. These interior courtyards played an important role in modifying the hot climate. They also served both as light- wells, in a building-type, in which the use of exterior windows is restricted, and as air-wells into which the cooling, dense, night air sinks. The courtyard also permitted outdoor activities, providing protection from the wind, dust and sun (Petherbridge, 1995). As well as a courtyard and a pool, most of the traditional houses also had an Iwan (veranda). During the Safavid period, the main façade, which looked onto the inner courtyard, had a large opening in the middle and two smaller ones on both sides. During the Qajar period (1794- 1925) the layout of traditional houses was more or less similar to that of the Safavid period; however, as a result of the devel- oping relationship between Iran and Europe, the first signs of western taste could be detected in the buildings of this period. For example, sometimes a house had an architectural embel- lishment or decoration which showed carved images of human beings, or it had, within its construction, the type of half-circle arches and small round openings, which were somewhat remi- niscent of and similar to the European architecture of the 19th century. Eccentric Type (Mainly Nor thern Part of Iran) The eccentric type houses in Iran could generally be found in areas that their climate is friendlier (Figure 2). The vernacular architecture in many settlements in north and west of Iran fol- lows the eccentric type of housing. There is no courtyard in this type of houses, and their architectural elements, differ from re- gion to region. However, there are some characteristics, which are more or less common between all different types of eccen- tric houses. Characteristics such as outward looking general layout and frequent use of Iwan (veranda) to integrate outside and inside are the main common features. In this type of houses, openings are larger and looking toward outside. Comparison of Introverted and Eccentric Types One of the important aspects of Iranian traditional houses is Figure 2. Eccentric type, Masouleh Village. Photo: Author. their adaptation to culture and climate. Courtyard houses were developed mainly in central part of Iran to protect their users from harsh climate conditions such as high temperature, low humidity, and sandy winds. In addition, the socio-cultural en- vironment of the central parts of the country, which was based on maintain ing the maximum privacy, wa s encouraging th e use of courtyard houses too. The majority of houses in these re- gions are introverted. All spaces and their openings were or- ganized around the central courtyard with slightest or no con- tact with outward. Such design solution would reply both cli- matic and cultural needs of residents to be protected from the outside. Yet, semi open spaces such as Iwan were typically open to courtyard. Iwan is vaulted space with one side fully open. The eccentric types of Iranian houses, however, showed an entirely different design approach. These types of houses, which were generally developed in Northern part of Iran, were oriented toward outside. The climate condition in these regions is moderate, humid and with plenty of precipitation. Therefore, there was no need to protect the residents of house from out- ward conditions. There are almost no central courtyard houses in these regions. Houses have had direct relation with outside. Semi open spaces such as Iwan could be seen in these regions too; however, they are open to the outside of house. The so- cio-cultural atmosphere in northern part was and still is differ- ent from central part of Iran. Culture would encourage disclo- sure rather than enclosure and privacy. Overall, the introverted and eccentric types of traditional Ira- nian houses demonstrated significant differences in space or- ganization, use of semi open and open spaces, and architectural elements. Though, since introverted houses were spread in much larger area than eccentric type, the traditional Iranian houses generally are known as courtyard houses. Contemporary Houses The modern movement in architecture began to evolve around the time of the First World War in Europe (Sudjic & Beyerle, 1999). The ‘Modern houses’ in the world were born at almost the same time. These houses had plain unornamented walls, with large areas of glass, whilst internally separate rooms were replaced by a continuum of space made possible by a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 233  R. M. SANI, P. MAHASTI structural frame. The resulting “open plan” reflected a new openness in living, the gradual breakdown of old social hierar- chies, and a reduced dependence on servants (Weston, 2002). Later, this modern type of housing became commonplace all over the world, although this international style was gradually adapted and transformed according to the climatic and cultural requirements of d ifferent regions (Weston, 2002). Modern houses, because of the sought after image they repre- sent, have been universally accepted worldwide, even if the construction itself fails to be supportive of any given culture and to integrate the issues of privacy, lifestyle, religion, etc. (Rapaport, 2007). The modern housing style has also been viewed in Iran as the ideal image for a dwelling since the arri- val of modernization in Iran. Consequently, the traditional Ira- nian house layout has become almost forgotten and more or less obsolete. This general rejection and lack of knowledge in re- spect of the traditional houses, however, was not confined only to Iran and Iranian architecture. Modern houses were developed in the service of a new vision for living, to fulfill the dream of a new world rebuilt from the ground up on new aesthetic, social, and political principles (Weston, 2002). Thus, in many countries, including Iran, modern houses rep- resent the new conception of the world. In addition, as Laurel (2003) states that, at the present time, the balance of power between designers and design users has undergone radical change. Designers cannot dictate their taste and preferences to the purchasers or the residents; a reciprocal dialogue, in respect of the design process, between them and the designers has been created and encouraged. For example, one of the main chal- lenges for architects in Iran was designing according to the new construction rules, which were established after arrival of mod- ernization. According to the newly established rules, which are still in use for all cities in Iran, constructors are allowed to lo- cate their building only on 60% of north side of each plot. As a result of such regulation, the organization of houses and image of cities have been changed in Iran. (Figures 3 and 4) Figure 3. City of Hamedan, housing layout prior to new construction rules. Figure 4. City of Hamedan, housing layout after new con- struction rules. Overall, although modern houses layout has also been ac- cepted and utilised enthusiastically in Iran, the last decades have seen a search for cultural manifestation, and various ap- proaches have been tried. Those efforts can be categorized wi- thin two periods after arrival of modernization in Iran. The first period, contains the work of architects from the beginning of Second Pahlavi period (1941-1979) until Islamic Revolution (1979). The second period starts from the Islamic Revolution and continues until present time. To explore the contemporary houses, in the following section four samples have been selected. The samples are all belonged to the second period (1979-onward) of search for cultural man- ifestation in residential architecture of Iran. The selection of houses was based on their diverse approaches in compromising between past and present of Iranian architecture. Although, these houses are nationwide well-known cases of Iranian con- temporary houses, they are neither the only valuable examples nor they have been entirely successful in marrying the past and present. Sample One: Shushtar New Town—Khuzestan, 1978 Architect: Kamran Diba During the first period, the more thoughtful approaches to- wards the construction of the contemporary Iranian house can be found in the works of outstanding architects, such as Kam- ran Diba, Hoshang Seyhon, Farmanfarmayeyan, etc. The work of Kamran Diba in designing a new city (Shushtar) in the southwest of Iran is the earliest example (Figures 5 and 6). Figure 5. General view from New_Shushtar. Photo: http://archnet.org/library/images/one-image. jsp?location_id=1566&image_id=13423): © Aga Khan Award for Architecture/Kamran Adle. Figure 6. Plan organization of houses with courtyard. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 234  R. M. SANI, P. MAHASTI According to the “technical review of Shushtar New Town” to the Aga Khan Award for architecture (1986), New-Shushtar is a residential community for 25 - 3 0,000 people. The new town has had to integrate different income groups, although it was de- signed primarily for company employees. The design of the whole town and its residential districts has attempted to rede- fine the traditional approach. Diba (1980) explains the tradi- tional houses of this region based on the arrangement of four rooms separated by the cross formed vaulted Iwans. He explains that the central intersection was a courtyard, which in desert areas could provide more pleasant cooling effect (Diba, 1980). Diba (1980) then goes on to explain that the design of New- Shushtar follows the general pattern of traditional Iranian ar- chitecture, which assumes its form in relation to the local cli- matic constraints and conditions, available local technology, and the customs and culture of the region. Individual houses have thick walls, small windows on the shady side of the house, usually facing a small inner courtyard. Diba (1980) describes the courtyard as a place for water, plants, blue sky, stars, cool- ness and as: “a room with the sky for a roof”, “an oasis that becomes the image of paradise”. Houses have box-forms with variations in height and relief. Facades are simple and rectilin- ear. In the designing of these houses, the focus was to preserve the traditional concept of the room as a flexible unit, by pro- viding large spaces which are multi-purpose and potentially divisible (Diba, 1980). The first phase of the project was completed in 1978, and in 1986 it attracted the third Aga Khan Award Master Jury’s ap- preciation. Over the last twenty years, the design of this project has also inspired a number of other new-town projects in Iran. The housing of New-Shushtar was internationally acclaimed and recognized as offering an alternative approach in respect of the issue of mass housing (Derakhshani, 2004). During the second period, after the Islamic revolution, vari- ous approaches have been tried to marry the traditional charac- teristics with contemporary needs in housing design. The most popular approach to linking the past with the present, however, has focused on the exterior image of house. As Diba explains: “The most fashionable cladding material is pale (light beige) brick, which gives buildings a link with traditional architecture” (Diba, 1991). Following samples are some of the more suc- cessful efforts after the Islamic revolution in Iran. Sample Two: Sadri Residence—Isfahan, 1999 Architect: Mohamad Reza Ghanei In the design of this house, the familiar Iranian traditional house characteristics of courtyard and pool have been used again. The building is divided into two parts, a public, and a private area. According to the designer, a narrow corridor, which could be seen as resembling the tiny twisting, traditional streets, connects these two parts (Figure 7). The house, how- ever, has large exterior glass windows (Figure 8). The essence of the courtyard has been preserved in this house, although the identity of the courtyard has been altered to that of a front yard (Figure 8). Whilst the house has an acceptable modern appear- ance, the main characteristics of Iranian traditional houses have been retained in its design. Sample Three: Vanak Housing—Tehran, 1989 Architect: Kamran Safamanesh This housing complex contains five apartments with com- Figure 7. Schematic plan with passage at the middle, front and back yard and pool. Figure 8. Yard view, Sadri residence, Isfahan. Photo: http: //archnet.org/library/images/one-image.jsp?locat ion_id=11857&image_id=164130 © Aga Khan Award for Architecture/Mohamad Reza Ghanei. mon facilities such as swimming pool, courtyard, and play room. The apartments have different designs. This complex is used as a reference and teaching model for architectural students in Iran (Diba, 1991). The presences of the yard and pool as well as the proportions of the openings (doorways and windows) are remi- niscent of traditional Iranian houses, although in this complex the courtyard is, in fact, designed as a front yard. The design of the frontal façade makes a reasonable link with the past, with the presence of the Iwan, (balcony) in addition to use of a large opening in the middle with two smaller ones on both sides (Figure 9). The style of the windows and an elevated skyline is reminiscent of the traditional house design. The inward looking construction and design layout of traditional courtyard houses has, however, been altered to a somewhat outward looking contemporary house (Figure 10). Sample Four: Gonbad Houses—Gonbade Kavus, 2000 Architect: Firouz Firouz These two houses have a common entrance yard and a gar- den area with the swimming pool at the front. The concept of the traditional courtyard in these houses has been altered to present and include an entrance court and a garden area (Figure 11). Brick has been used as a familiar traditional building mate- rial, except in the construction of the yard and the pool. The size of the windows and openings are small and look onto the garden. They are protected by a deep Iwan (veranda) which also overlooks the garden (Figure 12). The cubic form of these Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 235  R. M. SANI, P. MAHASTI Figure 9. Façade organization with Iwan and large openings at the middle, and small openings in both sides. Figure 10. Yard facade, Vanak housing. Photo: http://archnet.org/library/images/one-i mage.jsp?image_id=24810&location_i d=2461) © Aga Khan Award for Ar- chitecture/Kamran Safamanesh. houses resembles that of the traditional houses (Figure 13). Conclusion People envision the environment in which they wish to live. One expectation of people in respect of contemporary housing in Iran as well as any other developing country is that it should be related to the modern image of life. At the present time, this is one of the main reasons for people abandoning the traditional house style for house forms that communicate modern identity and status. On the other hand, since the modern identity for Iranian houses is not defined yet, many existing contemporary houses are demonstrating an eclectic type of architecture, which is not satisfying even the taste and expectations of their users to Figure 11. Front and entrance yards. Figure 12. Use of veranda. Figure 13. Gonbad houses, Gonbade Kavus. Photo: h ttp://archnet. org/library/images/one-image.jsp?image_id= 166612 &location_id=11887 © Aga Khan Award for Archi- tecture/Firouz Firouz. be the “home”. Thus, the appropriate response to the construction of con- temporary housing should respect both the contemporary needs and the cultural requests. Through combining essential charac- teristics of the traditional houses with the new elements of mo- dern houses, it would be possible to offer solutions in contem- porary housing construction. In this study, the contemporary sample houses reflect some of the characteristics of traditional houses, although the idea of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 236  R. M. SANI, P. MAHASTI Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 237 traditional house has been altered and changed into modern image of house. In the examples, the western notion of house and the contemporary Iranian way of life has been integrated with traditional architectural characteristics. The earlier exam- ples of contemporary Iranian housing style such as the design of the city of New Shushtar were primarily based on traditional characteristics, whilst the latter examples were altered and transformed to follow the design of the modern contemporary house type. There are some certain traditional features, which have been transformed and used again in contemporary houses. For instance, although the essence of courtyards is used in many contemporary examples, they have been changed to front yards, entrance yards, and back yards. Use of Iwan (veranda) and arrangement of opening in the façade of housing are the other main traditional features which through alteration, are still used in contemporary designs. However, in order to understand the full effect of modernity and change on the contemporary Iranian houses, further studies, which examine and assess samples of other traditional housing types, will be required to follow this one. This study aimed to set the scene and point the way for further research on housing, especially in developing countries, which, inevitably, experi- ence the rupture from their traditional architecture. REFERENCES Atabaki, T. (2005). Ethnic diversity and territorial integrity of Iran: Domestic harmony and regional challenges. Iranian Studies, 38, 23- 44. doi:10.1080/0021086042000336528 Banani, A. (1961). The modernization of Iran (1921-1941). Stanford: Stanford University Press. Bosworth, C. E. (1996). The safawids, the new Islamic dynasties, a chronological and genealogical manual. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Uni- versity. Cleveland, W. (2004). A history of the modern Middle East (3rd ed.). Boulder: Westview. Derakhshani, F. (2004). Iran and Aga Khan Award for architecture, Iran: Architecture for changing societies. http://www.archnet.org/library Diba, D. (1980). Technical review of Shushtar New Town, the Agha Khan Award for architecture. http://www.archnet.org Diba, D. (1991). Regional report: Iran and contemporary architecture, MIMAR 38: Architecture in development. London: Concept Media Ltd. http://www.archnet.org Diba, K. (1980). The recent housing boom in Iran—Lessons to remem- ber. In L. Safran (Ed.), Housing: Process and physical form. Phila- delphia: Aga Khan Award for Architecture. http://www.archnet.org Haeri, M. (2002). Dream house—Kashan’s Persian houses, ME’MAR. Iranian Quarterly on Archi te ct ure a nd U rb an De si gn , 88-98. Keddie, N. (1998). Iran: Understanding the enigma: A historian’s view. MERIA Journal (Middle East Review o f International Affairs), 2, 3. http://meria.idc.ac.il/journal/1998/issue3/keddie.pdf Laurel, B. (2003). Muscular design, design research-methods and pers- pectives, do you need this in again? Los Angeles: Massachusetts In- stitute of Technolo gy. Lawrence, R. (2005). Methodologies in contemporary housing research: A critical review. In D. U. Vestbro, Y. Hurol, & N. Wilkinson (Eds.), Methodologies in housing research. Gateshead: The Urban Interna- tional Press. Lin, G. (2002). Hong Kong and the globalisation of the Chinese dias- pora: A geographical pers pect ive. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 43, 63-91. doi:10.1111/1467-8373.00158 Morgan, D. (1999). Rethinking Safavid Shiism, the heritage of Sufism. Oxford: Oneworld. Oliver, P. (2003). Dwellings—The vernacular houses world wide. Lon- don: Phaidon. Passi, A. (2002). Bounded spaces in the mobile world: Deconstructing “regional identity”. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-9663.0019 0 Petherbridge, G. (1995). The house and society. In G. Michell (Ed.), Architecture of the Islamic world—Its history and social meaning. London: Thames and Hudson. Rapaport, A. (2007). The nature of the courtyard house: A conceptual analysis. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, XVIII, 57- 71. Sudjic, D., & Beyerle, T. (1999). Home, the twentieth-century house. London: Laurence King. Weston, R. (2002). The house in the twentieth century. London: Laur- ence King.

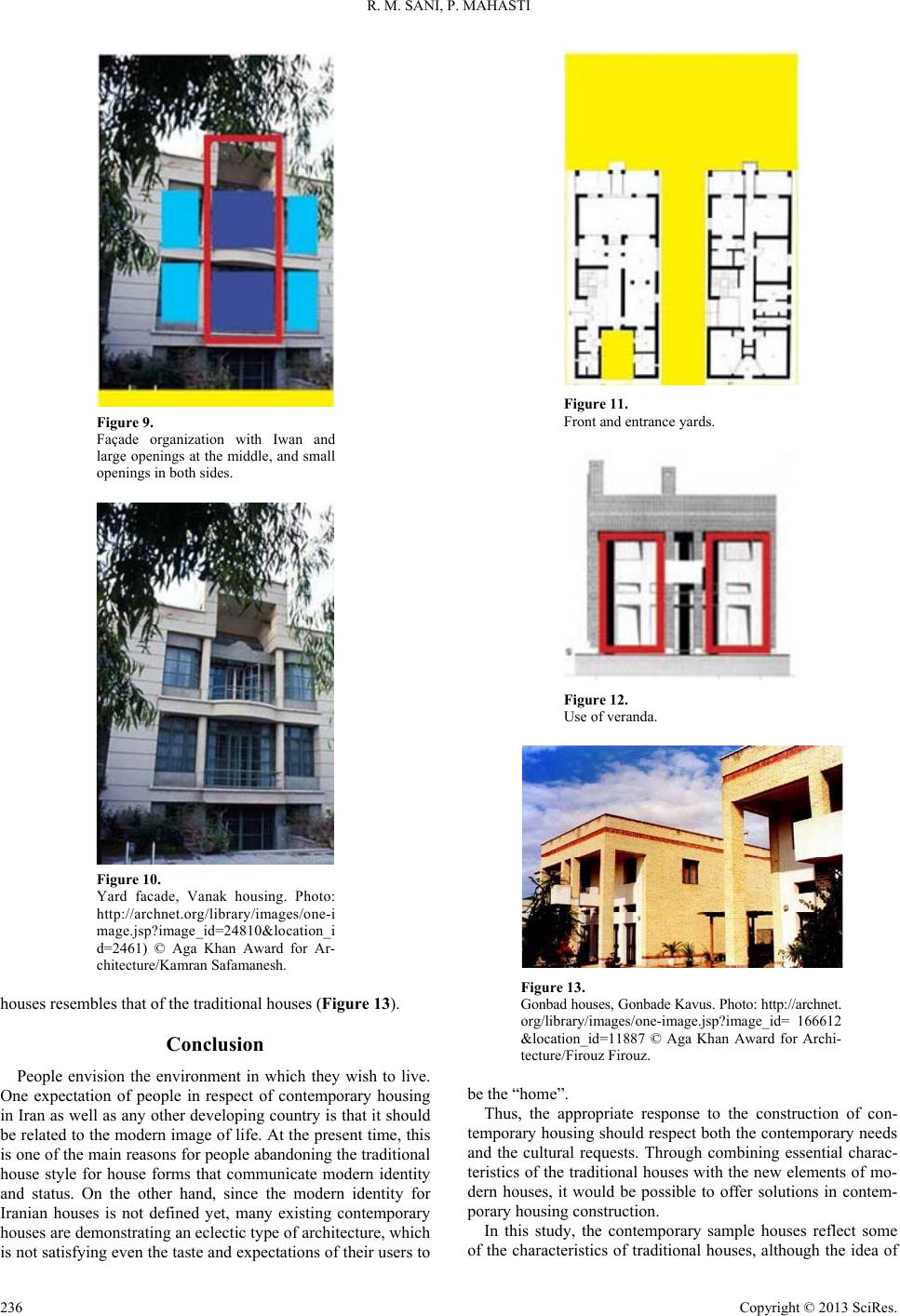

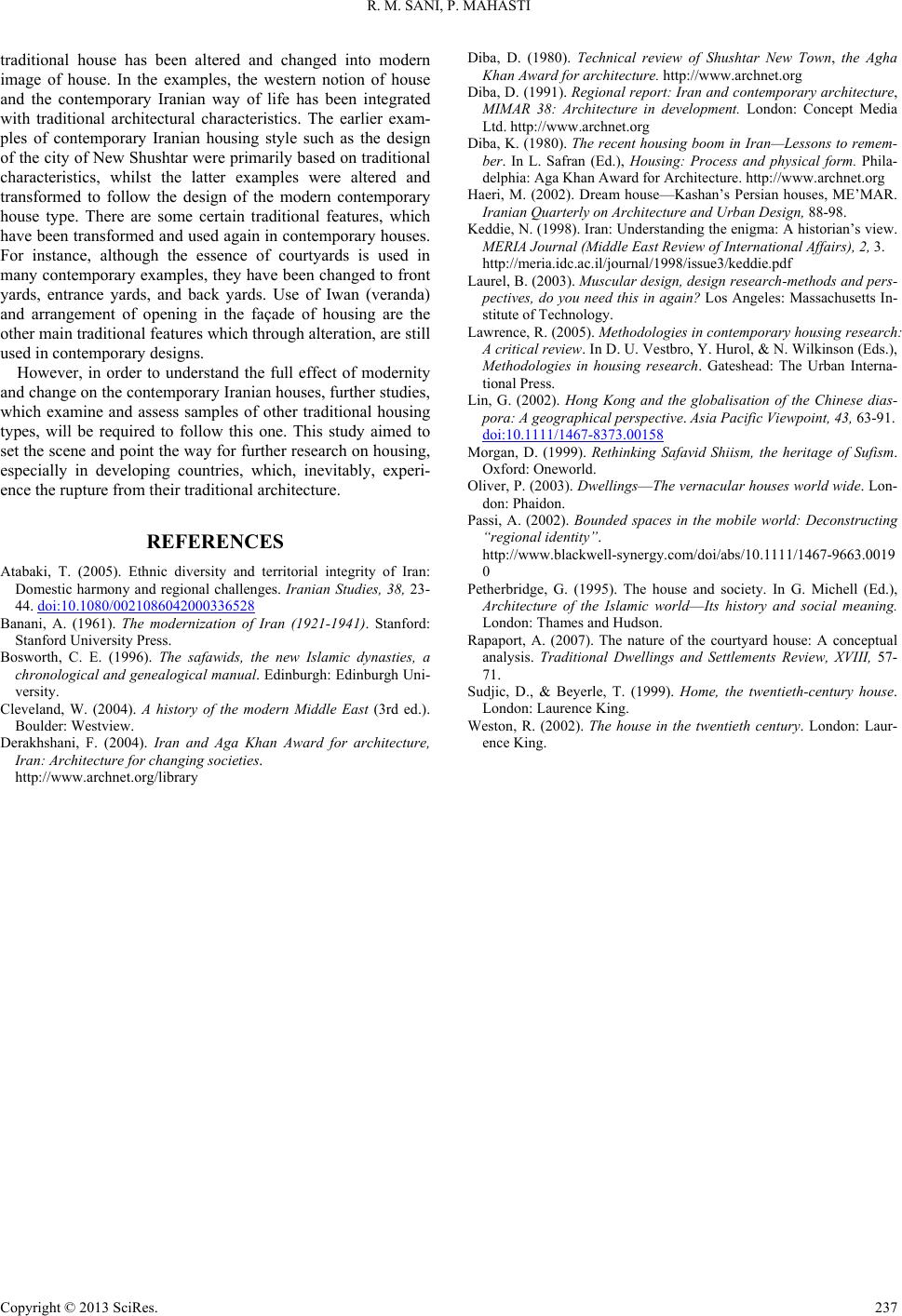

|