Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.6, 526-534 Published Online June 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.46075 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 526 Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Persian Disgust Scale-Revised: Examination of Specificity to Symptoms of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Giti Shams1*, Elham Foroughi2, Melanie W. Moretz3, Bunmi O. Olatunji4 1Roozbeh Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Psychology, School of Behavioral Science, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia 3Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, Yeshiva University, New York, USA 4Department of Psychology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA Email: *shamsgit@tums.ac.ir Received March 9th, 2013; revised April 13th, 2013; accepted May 11th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Giti Shams et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Although a growing body of research has implicated disgust in the etiology of a variety of anxiety disor- ders, there remains a paucity of research examining this phenomenon across different cultures. The pre- sent study examined the factor structure and psychometric properties of a newly adapted Persian Disgust Scale-Revised (PDS-R). A large sample (n = 374) of Iranian students completed the PDS-R and other symptom measures of psychopathology including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Results showed good internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the PDS-R. Confirmatory factor analysis found support for two- and three-factor models of the PDS-R. However, examination of internal consistency es- timates suggests that a two-factor model of contagion disgust and animal-reminder disgust may be more parsimonious. The PDS-R total and subscale scores displayed theoretically consistent patterns of correla- tions with symptom measures of psychopathology. Structural equation modeling also revealed that latent disgust sensitivity, defined by the contagion disgust and animal-reminder disgust subscales of the PDS-R, was significantly associated with latent symptoms of contamination and non-contamination-based OCD when controlling for latent negative affect. The implications of these findings for the cross-cultural as- sessment of disgust in the context of anxiety related pathology are discussed. Keywords: Persian Disgust; Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; Contagion Introduction The traditional definition of disgust is linked with food rejec- tion (e.g. Angyal, 1941; Darwin, 1872/1965; Ekman & Friesen, 1975; Tomkins, 1963), revulsion at the prospect of oral incur- poration of an offensive object (Rozin & Fallon, 1987). How- ever, stimuli that elicit disgust varies widely (Rozin, Haidt, & McCauley, 2000). Accordingly, it is of central importance that measures of individual differences in disgust capture the di- verse range of disgust elicitors. However, the first self-report measure of disgust, the Disgust Questionnaire (DQ, Rozin, Fallon, & Mandell, 1984), was developed to measure only con- cerns about food contamination. Appreciation of the diverse range of disgust led to the development of the Disgust Scale (Haidt et al., 1994), a more comprehensive measure of the wide range of disgust elicitors. The DS consists of 32 items and as- sesses eight domains of disgust: 1) food that has spoiled; 2) animals that are slimy or live in dirty conditions; 3) body prod- ucts including body odors, feces, mucus, etc.; 4) body envelope violations, or mutilation of the body; 5) death and dead bodies, 6) culturally deviant sexual behavior; 7) hygiene violations, and 8) sympathetic magic (improbable contamination). Although the DS has been instrumental in furthering current understanding on the nature and function of disgust, the scale is not without limitations, particularly considering the poor inter- nal consistency of the individual subscales (Haidt et al., 1994; Tolin et al., 2006). More recently, Olatunji and colleagues (2007) refined the DS by removing items that displayed poor psychometric properties. This re-analysis revealed that the DS assesses 3 dimensions of disgust: Core Disgust, Animal Re- minder Disgust, and Contamination-Based Disgust. Importantly, the reliability of the three theoretically driven subscales were much higher than that of the original eight subscales. Structural modeling of this Disgust Scale-Revised (DS-R) also provided support for the specificity of the 3-factor model, as Core Dis- gust and Contamination-Based Disgust were significantly pre- dictive of obsessive-compulsive disorder OCD) concerns, whereas Animal Reminder Disgust was not. Furthermore, re- sults from a clinical sample indicated that patients with OCD washing concerns scored significantly higher than patients with OCD without washing concerns on both Core Disgust and Contamination-Based Disgust, but not on Animal Reminder Disgust. *Corresponding author.  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 527 The comprehensive refinement by Olatunji and colleagues (2007) has addressed many of the psychometric limitations of the DS. Although disgust has been conceptualized as a basic emotion that is observed across different cultures (Haidt, Rozin, MacCauley, & Imada, 1997) however, the extent to which these findings extend across cultures remains unclear. Recently, Ola- tunji and colleagues (2009) evaluated the factor structure of the DS-R in Australia, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Nether- lands, Sweden, and the United States. Support was found for the three-factor solution consisting of core disgust, animal- reminder disgust, and contamination disgusts all countries ex- cept the Netherlands. The present study extends research on the cross-cultural assessment of disgust by examining the factor structure and psychometric properties of a newly developed Persian DS-R (PDS-R). It was predicted that the PDS-R would yield three replicable factors consisting of core disgust, con- tamination disgust, and animal-reminder disgust. This study also examined the reliability and validity of the PDS-R in rela- tion to OCD symptoms Research has also shown that high disgust propensity (i.e., the frequency or ease with which one generally responds with disgust) is associated with various psychopathological condi- tions (Olatunji & Sawchuk, 2005). There has been a surge of research interest on the role of disgust in the etiology of various anxiety disorders (Olatunji & Sawchuck, 2005; Woody & Teachman, 2000), including contamination-based obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD). Fear of contamination is one of the most common themes associated with OCD (Stekette, Grayson, Foa, 1985; Rasmussen & Tsuang, 1992). Studies have reported significant associations between dis- gust proneness and a range of OCD symptoms such as hoarding, neutralizing, ordering and religious obsessions. However, re- search has consistently demonstrated a stronger positive asso- ciation between self-report measures of disgust propensity and the contamination subtype (Mancini et al., 2001; Moretz & McKay, 2008; Olatunji et al., 2004). For example, Olatunji et al (2004) found that scores on self-report measures of disgust propensity accounted for 43% of the variance in scores on the contamination subscale of the Padua Inventory (Burns et al., 1996). Moreover, studies have found that the relationship be- tween disgust and contamination fear remains when controlling for negative affect and depression (e.g., Moretz & McKay, 2008; Olatunji et al., 2007; Tolin, Woods, & Abramowitz, 2006). In a more recent study, Olatunji (2010) found that changes in disgust sensitivity levels (the perceived negative impact of experiencing disgust) over a 12-week period pre- dicted change in symptoms of contamination-based OCD, even after controlling for age, gender, and change in negative affect. Behavioral research has also implicated disgust in contamina- tion-based OCD. For example, Deacon and Olatunji (2007) found that disgust levels significantly predicted behavioral avoidance of sources of contamination even when controlling for negative Affect. Hence, evidence from both self-report and behavioral tasks suggests that the tendency to experience dis- gust may be a risk factor for the development of contamina- tion-based OCD (Olatunji, Cisler, McKay, & Phillips, 2010). The present study also investigated the association between DS and OCD symptoms as measured by self-report instruments, based on previous findings it was predicted that disgust prone- ness would remain significantly associated with OCD symp- toms after controlling for negative Affect. Methods Participants Participants were 374 students with a mean age of 20.54 years (SD = 2.61). The majority of the sample consisted of women (77%), and all participants were Muslim. Participation was voluntarily and no payment or course credits were offered. One hundred and ninety six (124 women) of the Participants completed the self-report measures described below approxi- mately 1 month after their initial administration. Measures All participants completed the Farsi version of the following measures. The measures in this study (with the exception of the Disgust Scale-Revised) were already translated into Persian and were reported to show sound psychometric properties compara- ble to those obtained in Western samples. The Disgust Scale-Revised (DS-R; Haidt,., 1994; modified by Olatunji et al., 2007) is a 25-item self-report measure of disgust sensitivity. Respondents answer each item along a 5-point Likert-type scale. Lexical anchors range from 0 = (Strongly disagree) to 4 = (Strongly agree). Olatunji et al. (2007) found evidence for three factors of core, animal-reminder, and contamination disgust. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002) is an 18-item questionnaire based on the earlier 84-item OCI (Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles, & Amir, 1998). Participants rate the extent to which they are bothered or dis- tressed by OCD symptoms in the past month on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The OCI-R assesses symptoms of OCD across six domains including: washing, checking/doubting, obsessing, mental neu- tralizing, ordering, and hoarding. The Padua Inventory-revised (PI; Burns et al., 1996) con- tamination subscale is a 10-item self report instrument that measures as individual’s aversion towards contamination (e.g., I feel my hands are dirty when I touch money”. Individuals respond to each item on a 5-point Likert scale indicating the degree to which they would be disturbed by the situation de- scribed in the items (0 = “not at all”, 4 = “very much”). The total score is computed by summing the 10 items. The complete PI has adequate psychometric properties and the contamination subscale has high internal consistency (alpha = .085; Burns et al., 1996). The PI contamination subscale correlates highly with other measures of contamination fear (Burns et al., 1996; Thor- darson et al., 2004). The Vancouver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory (VOCI; Thordarson, Radomsky, Rachman, Shafran, Sawchuk, & Hak- stian, 2004). The VOCI-Contamination Subscale is a 12-item subscale of the VOCI questionnaire that assesses fear of physic- cal contamination. Items involve direct physical contact with a contaminant, (e.g., I feel very dirty after touching money), amount of time spent removing physical contaminants (e.g., I spend far too much time washing my hands), and concerns about germs and disease (e.g., I am afraid to use even well kept public toilets because I am so concerned about germs). Excel- lent internal consistency and convergent and divergent validity have been demonstrated for the overall VOCI scale. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S; Speilberger et al., 1983) is a 20- item measure of state anxiety or how anxious the participant feels “right now”. State-Trait Anxiety Inven-  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 528 tory—Trait Scale (STAI-T): The STAI-T has high reliability and validity. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Garbin, M.G. 1988) is a 21-item, self-report measure of depres- sive symptoms that was developed to adjust for alterations in the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Participants indicate how fre- quently they have experienced each of the 21 symptoms over the past two weeks on a 4-point Likert scale from “never” to 4 = “all the time.” The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ;Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990) is a 16-item self-report inventory that assesses the individual’s tendency to experience worry. The items focus on the excessiveness, duration and uncontrol- lability of worry and its related distress. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale 1 = “not at all typical of me” to 5 = “very typical of me”. Development of the PDS-R The English version of the DS-R was translated to Persian by the first author in Iran (forward translation, Step 1). The Persian version of the DS-R was compared to the original English ver- sion of the DS-R by two clinical psychologists and one psy- chiatrist (Step 2). Based on feedback received from compari- sons of the Persian and English version, minor changes were made. A small group of volunteers (n = 20) were given a copy the Persian translation of the DS-R; the volunteers were asked to comment on how well they understood its content. Addi- tional minor changes were made based on their suggestions. The modified version of the Persian DS-R was then back trans- lated to English. In order to make the scale culturally relevant to the Iranian population, the following changes were implemented. The original item 5: “I would go out of my way to avoid walking through a graveyard” was not appropriate for this population in Iran, graveyards are located outside of the city and inhabited areas and one would have to make special effort to get there. Thus, this item was changed to “I feel nauseated being in a graveyard, therefore I avoid going there” in accordance to Ira- nian domestic culture. The original item 26, “As part of a sex education class, you are required to inflate a new unlubricated condom, using your mouth”, was also inconsistent with cultural norms, as sex classes are not common practice and are rarely held in Iran. Therefore this item was replaced with “While eat- ing at a restaurant, you find a strand of hair in your food”. The original item 24”, you accidentally touch the ashes of a person who has been cremated” was slightly modified to reference only a “dead body” as cremation of the body is forbidden in Islam. “Monkey” in item 1 was also replaced with “‘cat” given that monkeys are not a domestic animal in Iran. “Science class” in item 2 was also replaced with “laboratory”, which is not specific to students only. Data Analysis Overview LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006) was used to ana- lyze the data. The factor structure of the Persian DS-R was determined using LISREL confirmatory factor analytic (CFA) techniques. To determine the best fitting model for the sample, three competing models of interest were estimated. A LISREL system file containing the polychoric correlation matrix served as the input data. The models were tested with the asymptotic covariance matrix (ACM) as a weight using the Weighted Least Squares (WLS) method of estimation. The WLS estimation is the only method of estimation that produces an asymptotically correct chi-square test of model fit with ordinal indicators (Byrne, 1998). The first indicator for each latent variable was constrained to a factor loading of 1 to serve as a reference variable and to set the metric. The following criteria were used to test the models’ fit: the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values less than .08 indicating reasonable errors of ap- proximation in the population and values less than .05 indica- tive of a good fit (Byrne, 1998; McDonald & Ho, 2002); the 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA, with a wide confi- dence interval indicating an imprecise estimate of the degree of fit in the population (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996); the comparative fit index (CFI), with values greater than .90 indicative of an acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999); and the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), with values greater than .95 indicative of a good fit (Byrne, 1998). The fit of com- peting models was tested by the chi-square difference test (CSDT) and comparison of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987). A no significant difference in χ2 between two competing models suggests the model has not lost its goodness of fit with additional imposed parameters .The AIC criterion is frequently used in model selection. When compar- ing two competing models, the model with the lowest AIC is considered the preferred model (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). This study compared two different structural equation mod- els to examine the relationship between Disgust Sensitivity, Negative Affect, and OCD Symptoms. SEM offers the advan- tage of estimating and removing measurement error in the models, leaving only common variance among factors (Ullman, 2006). Competing models of interest were examined to test whether adding Negative Affect to the model linking Disgust Sensitivity and OCD Symptoms would improve the fit, as compared to a model that did not include Negative Affect. The specificity of this relationship was tested by comparing separate models that included either measures of Contamination-Based OCD or Non-Contamination-Based OCD. In both cases, a structural meditational model was examined to evaluate the degree to which the relation between Disgust Sensitivity and Contamination-Based OCD is accounted for by Negative Af- fect. The full LISREL model consists of two components, the measurement model and the structural equation model. The measurement model shows how the measured variables, called indicators, are associated with the latent constructs of interest via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The structural equation model specifies and tests the proposed relationships among the indicators and latent variables. The PRELIS system file containing the raw data served as the input data. The Maximum Likelihood (ML) method was used to determine the fit of the proposed models to the data. The first indicator for each latent variable was constrained to a factor loading of 1 to serve as a reference variable and set the metric (Byrne, 1998). The following criteria were used to test the models’ fit: the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values greater than .10 indicating poor fit (MacCallum, et al., 1996; McDonald & Ho, 2002); the com- parative fit index (CFI) with values in the mid-.90 s indicating a good fit of the data to the model (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2000), and the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), with  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 529 values greater than .95 indicative of a good fit (Byrne, 1998). The fit of competing models was tested with the chi-square difference test (Δχ2) and using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987). In the chi-square difference test, the chi-square statistic and the degrees of freedom for the baseline (parent) model were subtracted from those of the nested (i.e., more restricted) model. The resulting chi-square value was evaluated for the difference of the degrees of freedom from the two models to determine if there has been loss of fit given the new constraints. A non-significant difference in 2 between two competing models suggests the model has not lost its goodness of fit with additional imposed parameters. The AIC criterion is used in model selection only and cannot be interpreted for a single model. When comparing two competing models, the model with the lowest AIC is considered the preferred model (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). Results Validity of the PDS-R Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations of all study variables were first examined .The means, standard deviations, and ranges for each variable are shown in Table 1. Table 1 also presents Pearson correlation coefficients between the PDS-R and various measures of psychopathology. Consistent with our predictions, the PDS-R was generally highly correlated with various measures of psychopathology, with the exception of depression. The PDS-R was most highly correlated with meas- ures of OCD symptoms. Table 1 also shows that the PDS-R total score demonstrated adequate internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .87. Table 1. Pearson correlations between study variables. Study Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1. PDS-R - .95 .86 .35 .47 .46 .14 .1.26 2. CD - .67 .32 .49 .47 .1 .06.22 3. ARD - .32 .35 .35 .17 .15.26 4. OCI-R - .64 .57 .37 .32.52 5. PI - .85 .25 .22.42 6.VOCI - .25 .22.43 7. STAI-S - .67.52 8.BDI - .52 9. PSWQ - M 50.65 36.06 14.58 20.838.25 9.45 42.12 10.5321.45 SD 15.52 10.48 6.43 10.8 6.33 7.15 11.52 9.499.21 Range 7 - 90 6 - 63 1 - 28 0 - 560 - 40 0 - 38 20 - 790 - 84 0 - 48 Alpha .87 .8 .8 .85 .86 .84 .93 .88.79 Note: CD = Contagion Disgust, ARD = Animal-Reminder Disgust, M = Mean, SD = standard deviation. PDS-R = Persian Disgust Scale-Revised; OCI-R = Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised; PI = Padua Inventory; VOCI = Van- couver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety, Inven- tory-State; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory-II; PSWQ = Penn State Worry, Questionnaire. All correlations > .14 significant at the p < .01 level. Test-Retest Reliability of the PDS-R Scores on the PDS-R were also highly consistent across time. The unbiased estimate of the Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) for the total score across the two time points (approxi- mately 1 month apart) in a subsample of participants was .85. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Three competing models of the factor structure of the PDS-R were tested. The first was a unidimensional (i.e., one-factor) model, in which all 25 items were loaded onto a single Disgust factor. The second model tested was a three-factor model com- prised of Core Disgust (12 items), Animal-Reminder Disgust (8 items), and Contamination Disgust (5 items) reported by Ola- tunji et al., 2007. Finally, a two-factor model comprised of Contagion Disgust (i.e., a combination of Core and Contamina- tion Disgust and made up of those 17 items) and “Animal-Re- minder Disgust” (8 items) was also fit to the data. This two- factor model was derived from prior research suggesting that Core and Contamination Disgust may both be mediated by a common pathogen prevention mechanism (Olatunji et al., 2007). As shown in Table 2, the one-factor, two-factor, and three- factor models of the PDS-R all provided a poor fit to the data because the RMSEA values were equal to or exceeded .10 (MacCallum et al., 1996). Therefore, the items of the PDS-R were examined. Because items 5 (Animal-Reminder Disgust) and 26 (Contamination and Contagion Disgust) were replaced in their entirety during the translation process to be culturally consistent with Persian practices, these items were removed, and the CFA was repeated. As shown in Table 3, the three- factor model of the PDS-R without items 5 and 26 provided an acceptable fit to the data with χ2 (227) = 879.08, p < .001, RMSEA = .09 The two-factor and one-factor models also pro- vided an acceptable fit to the data. Direct comparison revealed that the two-factor [Δχ2 (1) = 52.07, p < .001] and three factor [Δχ2 (3) = 59.25, p < .001] solutions fit the data significantly better than the one-factor model. The fit of the two- and three-factor models did not significantly differ from each other [Δχ2 (2) = 1.01, p = .60]. However, examination of the internal consistency of the separate factors (see Table 4) revealed that the two-factor solution appears to provide a more parsimonious and stable factor structure for the PDS-R. That is, the internal consistency for the combination of core and contamination disgust (Contagion Disgust) was higher than the internal con- sistency of either factor alone. Thus, a two-factor structure, with items 5 and 26 removed, was retained for structural equa- tion model analysis. Table 2. Summary statistics of confirmatory factor analyses of the Persian DS-R (N = 374). Model 2 df RMSE A RMSEA 90% CI CFI AGFIAIC 3-factor1340.79272.10 .098 - .11 .93 .93 1446.79 2-factor1345.16274.10 .098 - .11 .93 .93 1447.16 1-factor1400.04275.11 .10 - .11 .92 .93 1500.04 Note: df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approxima- tion; RMSEA 90% CI = 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA; χ2diff = nested χ2 difference.  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 530 Table 3. Summary statistics of confirmatory factor analyses of the Persian DS-R with items 5 and 26 removed (N = 374). Model 2 df RMSEA RMSEA 90% CICFI AGFI AIC 2diff Δdf p 3-factor 879.08 227 .089 .083 - .095 .91 .93 977.08 2-factor 880.09 229 .088 .082 - .095 .91 .93 974.09 1.01 2 .60 1-factor 932.16 230 .092 .085 - .098 .91 .93 1024.16 52.07 1 <.001 Note: df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; RMSEA; 90% CI = 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA; χ2diff = nested χ2 differ- ence. Table 4. Internal reliability of Persian DS-R factors and corrected item-total correlations. Factor Cronbach’s α Item Corrected Item-Total Correlation Core .730 1 .23 (Food) 3 .47 6 .16 (Animals) 8 .31 11 .41 13 .29 (Sym. Magic/Food) 15 .48 17 .47 20 .37 22 .37 25 .27 (Food) 27 .52 Contamination .560 4 .31 9 .32 18 .35 23 .41 Contagion .797 1 .25 (Food) 3 .48 4 .44 6 .18 (Animals) 8 .32 9 .35 11 .43 13 .30 15 .48 17 .50 18 .44 20 .39 22 .42 23 .52 25 .29 (Food) 27 .54 Animal Reminder .795 2 .52 7 .61 10 .39 14 .49 19 .41 21 .61 24 .67 Structural Equation Models Measurement Model 1. The first tested specified the two factors of the Persian DS-R (i.e., Animal-Reminder Disgust measurement model that was and Contagion Disgust) as indi- cators for a Disgust Sensitivity latent variable. The STAI, BDI-II, and PSWQ total scores were selected as indicators for the Negative Affect latent variable. Finally, the Padua Inven- tory Contamination Fear Subscale, The VOCI Contamination Fear Subscale, and the Washing subscale of the OCI-R were selected as indicators for the Contamination-Based OCD latent variable. The results indicated that the measurement model was a good fit to the data with χ2 (17) = 66.99, RMSEA = .09, RMSEA 90% CI = .066 - .11, CFI = .7, AGFI = .91. Measurement Model 2: The second measurement model that was tested specified that the two factors of the Persian DS-R (i.e., Animal Reminder Disgust and Contagion Disgust) were indicators for the Disgust Sensitivity latent variable. The STAI, BDI-II, and PSWQ total scores were again used as indicators for the Negative Affect latent variable. Finally, all subscales of OCI-R, excluding Washing, (i.e., Checking, Hoarding, Neu- tralizing, Obsessing, and Ordering) were selected as indicators for the Non-Contamination-Based OCD latent variable. The results indicated that the measurement model was a good fit to the data with χ2 (32) = 97.76, RMSEA = .076, RMSEA 90% CI = .059 - .93, CFI = .96, AGFI = .91. Structural Model 1: Competing models of interest were ex- amined to test whether adding Negative Affect to the model linking Disgust Sensitivity and Contamination-Based OCD Symptoms would improve the fit, as compared to a model that did not include Negative Affect. The first model (i.e., Model 1) specified direct effects only between Disgust Sensitivity and Contamination-Based OCD symptoms. The paths from Disgust Sensitivity to Negative Affect and from Negative Affect to Contamination-Based OCD symptoms were fixed to 0 in this baseline model. Table 5 shows that the fit of this model was poor, χ2 (19) = 108.50, RMSEA = .11. The next model tested (i.e., Model 2) specified direct and indirect effects between Disgust Sensitivity and Contamination-Based OCD symptoms. All paths were freely estimated in this model. This model pro- vided an adequate fit to the data: χ2 (17) = 65.42, RMSEA = .09, and it was a better fit to the data than the baseline model, Δχ2 (2) = 43.08, p < .001. Thus, adding the indirect effects of Negative Affect to the model resulted in an improvement in fit. The final model (i.e., Model 3) included indirect effects only between Disgust Sensitivity and Contamination-Based OCD symptoms. Thus, the path from Disgust Sensitivity and Con- tamination-Based OCD symptoms was fixed to 0 in this model, while the paths between Disgust Sensitivity and Negative Af- fect and Negative Affect and Contamination-Based OCD symptoms were freely estimated. This model was a poor fit to  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 531 Table 5. Summary statistics of structural equation models: Model 1 contamina- tion-based OCD. Model 2 df RMSEA RMSEA 90% CI CFI AGFIAIC 1 108.50 19 .11 .086 - .13 .95 .88 131.37 2 65.42 17 .088 .066 - .11 .97 .91 103.42 3 144.30 18 .14 .12 - .16 .93 .91 183.95 Note. Model 1: direct effects only; Model 2: direct and indirect effects; Model 3: indirect effects only; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; RMSEA 90% CI = 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA; CFI = comparative fit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness of fit index; AIC = Akaike information criterion. the data, with χ2 (18) = 144.30, RMSEA = .14, and the model lost its goodness of fit compared to Model 2, Δχ2 (1) = 78.88, p < .001. All the paths estimated in Model 2 were significant, and the standardized regression estimates are shown in Figure 1. These results indicate that that when controlling for latent Negative Affect, latent Disgust Sensitivity remains significant in the relationship between Disgust Sensitivity and Contamina- tion-Based OCD. Structural Model 2: Competing models of interest were ex- amined to test whether adding Negative Affect to the model linking Disgust Sensitivity and Non-Contamination-Based OCD Symptoms would improve the fit, as compared to a model that did not include Negative Affect. The first model (i.e., Model 1) specified direct effects only between Disgust Sensi- tivity and Non-Contamination-Based OCD symptoms. The paths from Disgust Sensitivity to Negative Affect and from Negative Affect to Non-Contamination Based OCD symptoms were fixed to 0 in this baseline model. Table 6 shows that the fit of this model was poor, χ2 (34) = 198.89, RMSEA = .11. The next model tested (i.e., Model 2) specified direct and indirect effects between Disgust Sensitivity and Non-Contamination Based OCD symptoms. All paths were freely estimated in this model. This model provided an adequate fit to the data: χ2 (32) = 99.71, RMSEA = .076, and was a better fit to the data than the baseline model, Δχ2 (2) = 99.18, p < .001. Thus, adding the indirect effects of Negative Affect to the model resulted in an improvement in fit. The final model (i.e., Model 3) included indirect effects only between Disgust Sensitivity and Non-Contamination-Based OCD symptoms. Thus, the path from Disgust Sensitivity and Non-Contamination-Based OCD symptoms was fixed to 0 in this model, while the paths between Disgust Sensitivity and Negative Affect and Negative Affect and Non-Contamina- tion-Based OCD symptoms were freely estimated. This model was an acceptable fit to the data, with χ2 (33) = 113.40, RMSEA = .085, but the model lost its goodness of fit compared to Model 2, Δχ2 (1) = 13.69, p < .001. All the paths estimated in Model 2 were significant, and the standardized regression esti- mates are shown in Figure 2. These results indicate that that when controlling for latent Negative Affect, latent Disgust Sen- sitivity remains significant in the relationship between Disgust Sensitivity and Non-Contamination-Based OCD. Discussion The present study examined the factor structure and psycho- metric properties of the PDS-R in a non-clinical student sample in Iran. CFA provided initial support for two- and three-factor models of the PDS-R. This finding is largely consistent with the notion that disgust does not represent a unitary construct (Ola- tunji et al., 2004). However, analysis of internal consistency suggested that the two-factor model of contagion disgust (a combination of core and contamination disgust with 17 items) and animal reminder disgust (8 items) may be a more parsimo- nious fit to the data. This finding appears to be inconsistent with that of Olatunji and colleagues (2009), who found that the three-factor solution of core disgust, animal-reminder disgust, and contamination disgust provided a better fit to the data than a one-factor model in Australia, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Japan, Sweden, and the United States. However, Olatunji et al. (2009) did not examine the relative fit of a two-factor model. The two-factor model appears to be consistent with the notion that domains of core and contamination disgust may share a com- mon pathogen-prevention mechanism (Olatunji et al., 2007). The PDS-R was also found to be stable over time, suggesting that disgust sensitivity is a relatively stable construct. Although item 5 (“I feel nauseated being in a graveyard, therefore I avoid going there”) and item 26 (“While eating at a restaurant, you find a stand of hair in your food”) were changed entirely in order to establish consistency with the cultural experiences of the participants, model fit was achieved after removal of these items. The degree to which disgust is experienced in response to various stimuli may differ as a function of culturally specific variables. The content of disgust can be idiosyncratic and may be shaped by personal experiences, as well as socio-cultural and religious influences. According to Islamic rules (Holy Koran), certain things are documented as being Najes (dirty, nasty im- pure) and they are thus strictly prohibited to Muslims. Najes include urine, feces, sperm, dogs, pigs, carrion, blood, pagans, and wine. In the current study, structural equation modeling revealed that latent disgust sensitivity, defined by the contagion disgust and animal reminder disgust subscales of the PDS-R, is sig- nificantly associated with latent symptoms of contamination and non-contamination based OCD. Some disgust domains (core and contamination) might share a “common factor” (dis- ease) that motivates specific behavioral tendencies (avoidance). In addition, consistent with previous findings, the PDS-R was positively correlated with contamination-based OCD symptoms however, this association was not specific to contamination based OCD. Table 6. Summary statistics of structural equation models: Model 2 non-con- tamination-based OCD. Model 2 df RMSEA RMSEA 90% CI CFI AGFIAIC 1 198.8934 .11 .090 - .12 .91 .86 214.00 2 99.7132 .076 .059 - .093 .96 .91 145.71 3 113.4033 .085 .069 - .10 .95 .90 164.86 Note: Model 1: direct effects only; Model 2: direct and indirect effects; Model 3: indirect effect only; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; RMSEA 90% CI = 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA; CFI = comparative fit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness of fit index; AIC = Akaike information criterion.  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 532 Error Padua Inventory VOCI OCI-R Washing .73 .88 .97 Animal Reminder Disgust Contagion Disgust .96 .69 Negative Affect .16 .30 .81 .80 .66 STAI Total BDI Total PSWQ Total .47 Disgust Sensitivity Contamination-B ased OCD Figure 1. Structural association between latent negative affect, disgust sensitivity, and contamination-based OCD. .80 .45 .46 .80 .49 Error OCI-R Ordering OCI-R Obsessing OCI-R Neutralizing OCI-R Hoarding OCI-R Checking Error Animal Reminder Disgust Contagion Disgust .77 .86 Negative Affect .25 .56 .81 .79 .68 STAI Total BDI Total PSWQ Total .24 Disgust Sensitivity on-C onta mi na tion-Based OCD Figure 2. Structural association between latent negative affect, disgust sensitivity, and non-contamination-based OCD. Clinical and anecdotal evidence from Iran suggests that con- tamination fears in patients with OCD are largely related to feelings of spiritual impurity rather than distress about germs, dirt or any other contamination which may cause disease or harm. For example, Dadfar and colleagues reported that the most common obsessive symptoms in their clinical sample was found to be concern or disgust with bodily waste or secretions, which according to the authors is described as a feeling of “Ne- jasat” or “spiritual impurity” in the Iranian culture (Dadfar, Bolhari, Malakouti, & Bayan Zadeh, 2001 ). In addition, Ghas- semzadeh et al. (2002) reported a high frequency of obsessions with themes of fear of impurity (62%) in their sample of 135 individuals with OCD in Iran. Therefore, while the rituals re- volve around contamination and cleaning themes, they are tan- gled with issues of religious contamination and purity, which usually manifest as a fear of spiritual impurity. The role of dis- gust in these religious-based contamination fears need to be further investigated in the non-western and Islamic culture of Iran. This is of particular interest as new research evidence emerging suggests that the experience of disgust increases the severity of moral judgment such that those high in DS tend to make harsher moral judgments (e.g., Inbar, Pizarro, Knobe, & Bloom, 2009, Olatunji, 2008). In this context, disgust has been conceptualized as an evaluative sentiment that may regulate moral behavior by identifying the objects, behaviors, or persons which are to be avoided in order to maintain “purity” (Schnall, Haidt et al., 2008). Therefore both the experience of disgust and OCD symptoms may be shaped by the broader cultural factors such as religiosity. Overall, the present findings offer initial data on the factor structure and psychometric properties of the PDS-R in a large sample of Iranian college students. Although further research is needed, it seems that the PDS-R is an excellent instrument for the assessment of disgust phenomena and can be used in the cultural context of Iran. However, as the participants were ho- mogenous in age, education, and ethnicity, it is premature at this stage to make a definite statement about the PDS-R factors within the Iranian context. A question for future investigations is whether the confirmatory factor structure of the present study can be replicated with other Iranian samples, including both clinical and non-clinical community populations. Although the validity and reliability of the PDS-R in this study were quite satisfactory, further studies are needed to investigate the PDS-R in more diverse samples. There is also a need for more work on the role of disgust in the genesis and maintenance of OCD in different Iran and on whether it is possible to differentiate  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 533 between different OCD sub-types based on disgust perceptions. While there is growing interest in exploring the role of dis- gust in psychopathology particularly in relation to OCD, there is a big gap in the literature on cross-cultural studies in both clinical and non-clinical samples. The current study needs to be extended a clinical sample of OCD patients in Iran. In addition, the overwhelming majority of research including the current study, implicating disgust in contamination-based OCD, is based on cross-sectional data and therefore it is diffi- cult to draw any inferences about the possible causal directions. Hence it would be important for future research to employ pro- spective longitudinal design to explore whether disgust sensi- tivity precedes the onset of OCD symptoms. Moreover, there is new emerging evidence to suggest that cognitive processes, specifically obsessive beliefs, may also mediate the relationship between disgust and contamination fear (Cisler, Brady, Olatunji, & Lohr, 2010). This is particularly relevant as new research findings from Iran provide support for the relevance of the ob- sessive beliefs and cognitive biases in the development and maintenance of OCD in Iran (e.g., Ghassemzadeh, Bolhari, Birashk, & Salavati, 2005; Mohammadi, Fata, & Yazdandoost, 2009; Shams, Karamghadiri, Esmaili Torkanbori, Rahiminejad, & Ebrahimkhani, 2006). REFERENCES Akaike,H.(1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrica, 25, 317-320. doi:10.1007/BF02294359 Angyal, A. (1941). Disgust and related aversions. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 36, 393-412. doi:10.1037/h0058254 Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Gabrin, M. G. (1988). The psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77-100. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5 Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and mul- timodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. Burns, G. L., Keortge, S. G., Formea, G. M., & Sternberger, L. G. (1996). Revision of the Padua Inventory of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms: Distinctiveness between worry, obsessions, and compulsions. Behavior Research and Therapy, 324, 163-173. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(95)00035-6 Byrne, B. M. (1908). A primer of LISREL: Basic applications and pro- gramming for confirmatory factor analytic models. New York: Springer-Verlag. Cisler, J. M., Brady, R. E., Olatunji, B. O., & Lohr, J. M. (2010). Dis- gust and obsessive beliefs in contamination related OCD. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 439-448. doi:10.1007/s10608-009-9253-y Dadfar, M., Bolhari, J., Malakouti, K., & Bayan Zadeh, A. (2001). An examination of the phenomenology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Quarterly Journal of Andees h e h Va Raftar, 7, 27-32. Darwin, C. (1872/1965). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Davey, G. C. L. (2004). Disgust and eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 6, 201-211. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0968(199809)6:3<201::AID-ERV224>3.0. CO;2-E Deacon, B., & Olatunji, B. O. (2007) Specificity of disgust sensitivity in the prediction of behavioral avoidance in contamination fear. Be- havior, Research and Therapy, 45, 2110-2120. Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1975). Unmasking the face. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Foa, E. B., Huppert, J. D., Leiberg, S., Langner, R., Kichic, R., Hajcak, G. O., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2002). The obsessive-compulsive inven- tory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment, 14, 485-496. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485 Foa, E. B., Kazak, M. J., Salkovskis, P. M., Coles, M. E., & Amir, N. (1998). The validation of a new obsessive compulsive disorder scale: The obsessive-compulsive inventory. Psychological Assessment, 10, 206-214. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.10.3.206 Ghassemzadeh, H., Bolhari, J., Birashk, B., & Salavati, M. (2005). Responsibility attitude in a sample of Iranian obsessive-compulsive patients. Internati o n a l J o ur nal of Social Psychi a t r y , 51, 13-22. doi:10.1177/0020764005053266 Ghassemzadeh, H., Mojtabai, R., Khamseh, A., Ebrahimkhani, N., Issazadegan, A., & Saif-Nobakht, Z. (2002). Symptoms of obsessive- compulsive disorder in a sample of Iranian patients. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 48, 220-228. doi:10.1177/002076402128783055 Haidt, J., Rozin, P., McCauley, C., & Imada, S. (1997). Body, psyche, and culture: The relationship between disgust and morality. Psy- chology and Developing Societies, 9, 107-131. doi:10.1177/097133369700900105 Haidt, J., McCauley, C., & Rozin, P. (1994). Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Persona lity and Individual Differences, 16, 701-713. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7 Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new al- ternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 Inbar, Y., Pizarro, D. A., Knobe, J., & Bloom, P. (2009). Disgust sensi- tivity predicts intuitive disapproval of gays. Emotion, 9, 435-439. doi:10.1037/a0015960 Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. A. (2006). LISREL 8.54 and PRELIS 2.54. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software. MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychologica l Me th o ds , 1, 130-149. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 Mancini, F., Gragnani, A., & D’Olimpio, F. (2001). The connection between disgust and obsessions and compulsions in a non-clinical sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 1173-1180. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00215-4 McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M.-H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7, 64- 82. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behavior Research and Therapy, 28, 487-495. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 Moretz, M. W., & McKay, D. (2008). Disgust sensitivity as a predictor of obsessive-compulsive contamination symptoms and associated cognitions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 707-715. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.004 Olatunji, B. O. (2008). Disgust, scrupulosity and conservative attitudes about sex: Evidence for a mediational model of homophobia. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1364-1369. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.04.001 Olatunji, B. O., Lohr, J. M., Sawchuk, C. N., & Tolin, D. F. (2007). Multimodal assessment of disgust in contamination-related obsessive- compulsive disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 45, 263-276. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.004 Olatunji, B. O., Moretz, M. W., McKay. D., Bjorklund, F., De Jong, P. J., Haidt, J., Hursti, T. J., Imada, S., Koller, S., Mancini, F., Page, A. C., & Schienle, A. (2009). Confirming the three-factor structure of the Disgust Scale-Revised in eight countries. Journal of Cross-Cul- tural Psychology, 40, 234-255. doi:10.1177/0022022108328918 Olatunji, B. O., & Sawchuk, C. N. (2005). Disgust: Characteristic fea- tures, social manifestations, and clinical implications. Journal of So- cial and Clinical Psychology, 27, 932-962. doi:10.1521/jscp.2005.24.7.932 Olatunji, B. O., Sawchuk, C. N., Lohr, J. M., & De Jong, P. J. (2004). Disgust domains in the prediction of contamination fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 93-104. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00102-5  G. SHAMS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 534 Olatunji, B. O. (2010). Changes in disgust correspond with changes in symptoms of contamination-based OCD: A prospective examination of specificity. Jou r n a l o f Anxiety Disorders, 24, 313-317. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.003 Olatunji, B. O., Williams, N., Lohr, J. M., Connolly, K., Cisler, J., & Meunier, S. (2007). Structural differentiation of disgust from trait anxiety in the prediction of specific anxiety disorder symptoms. Be- haviour Research and Therapy, 45, 3002-3017. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.011 Olatunji, B. O., Cisler, J. M., McKay, D., & Phillips, M. (2010). Is disgust associated with psychopathology? Emerging research in the anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Research, 175, 1-10. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.007 Rasmussen, S. A., & Tsuang, J. L. (1992). The epidemiology and clini- cal features of obsessive compulsive disorder. The Psychiatric Clin- ics of North America, 15, 743-758. Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. R. (2000). Disgust. In M. Lewise, & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions. New York: Guilford Publications. Rozin, P., & Fallon, A. E. (1987) A perspective on disgust. Psycho- logical Review, 94, 32-41. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.94.1.23 Rozin, P., Fallon, A. E., & Mandell, R. (1984). Family resemblances in attitudes to food. Developmental Psychology, 20, 309-314. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.20.2.309 Shams, G., Karamghadiri, N., Esmaili Torkanbori, Y., Rahiminejad, F., & Ebrahimkhani, N. (2006). Obsessional beliefs in patients with ob- sessive-compulsive disorder and other anxiety disorders as compared to the control group. Advances in Cognitive Science, 2, 83-90. Speilberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Simos, G. (1983). Manual for the state trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychology Press. Steketee, G. S., Grayson, J. B., & Foa, E. B. (1985). Obsessive-com- pulsive disorder: Differences between washers and checkers. Behav- ior, Research and Therapy, 23, 197-201. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(85)90028-2 Thordarson, D. S., Radomsky, A. S., Rachman, S., Shafran, R., Saw- chuk, C. N., & Hakstian, A. R. (2004). The Vancouver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory (VOCI). Behavior Research and Therapy, 42, 1289-1314. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.007 Tolin, D. F., Woods, C. M., & Abramowitz, J. S. (2006). Disgust sensi- tivity and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37, 30- 40. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.09.003 Tomkins, S. (1963). Affect, imagery, consciousness: Vol. 2. The nega- tive effects. New York: Springer. Ullman, M. T. (2006). Is Broca’s area part of a basal ganglia thalamo- cortical Circuit? Cortex, 42, 480-485. Woody, S. R., & Teachman, B. A. (2000). Intersection of disgust and fear: Normative and pathological views. Clinical Psychology: Sci- ence and Practice, 7, 291-311. doi:10.1093/clipsy.7.3.291

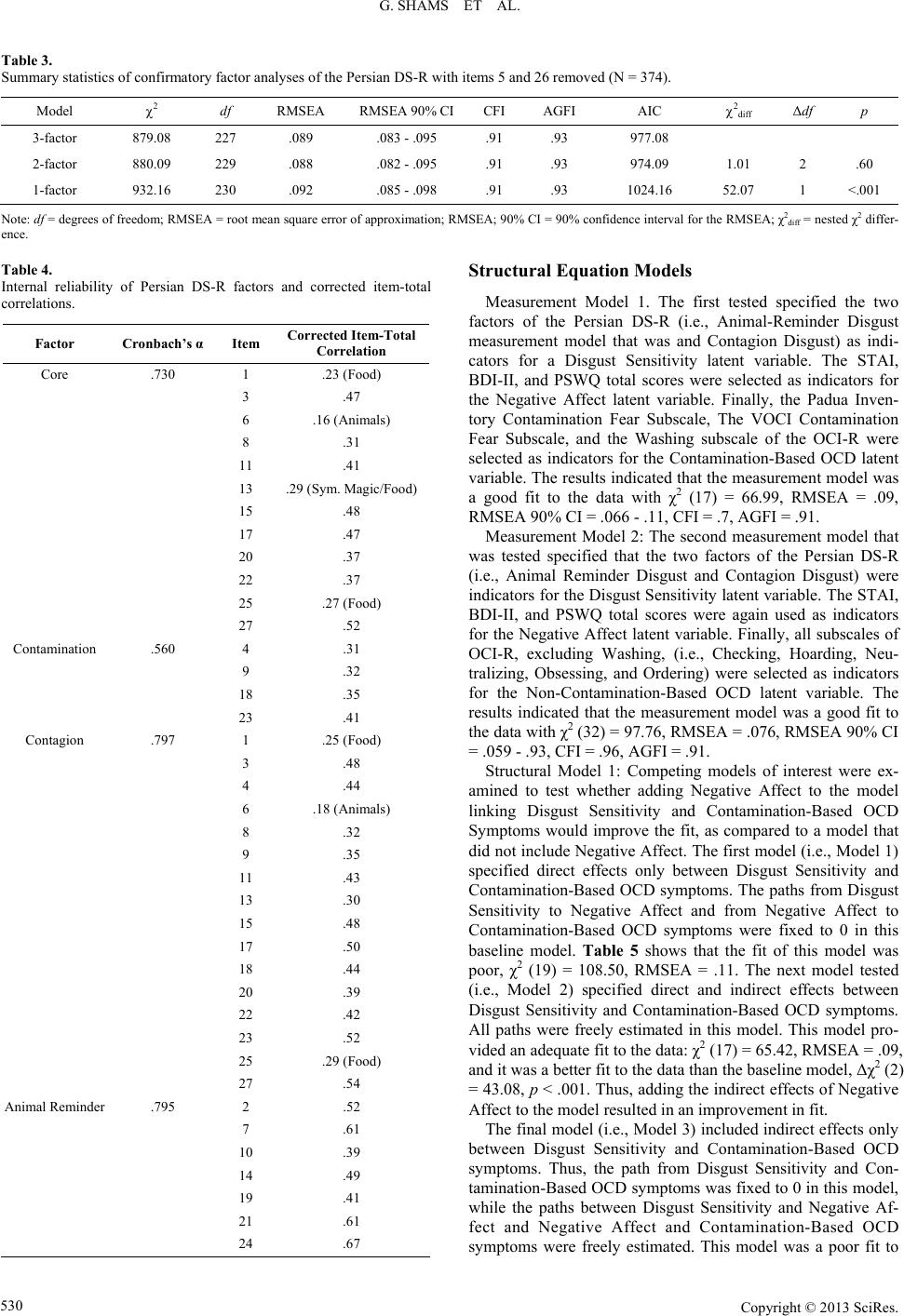

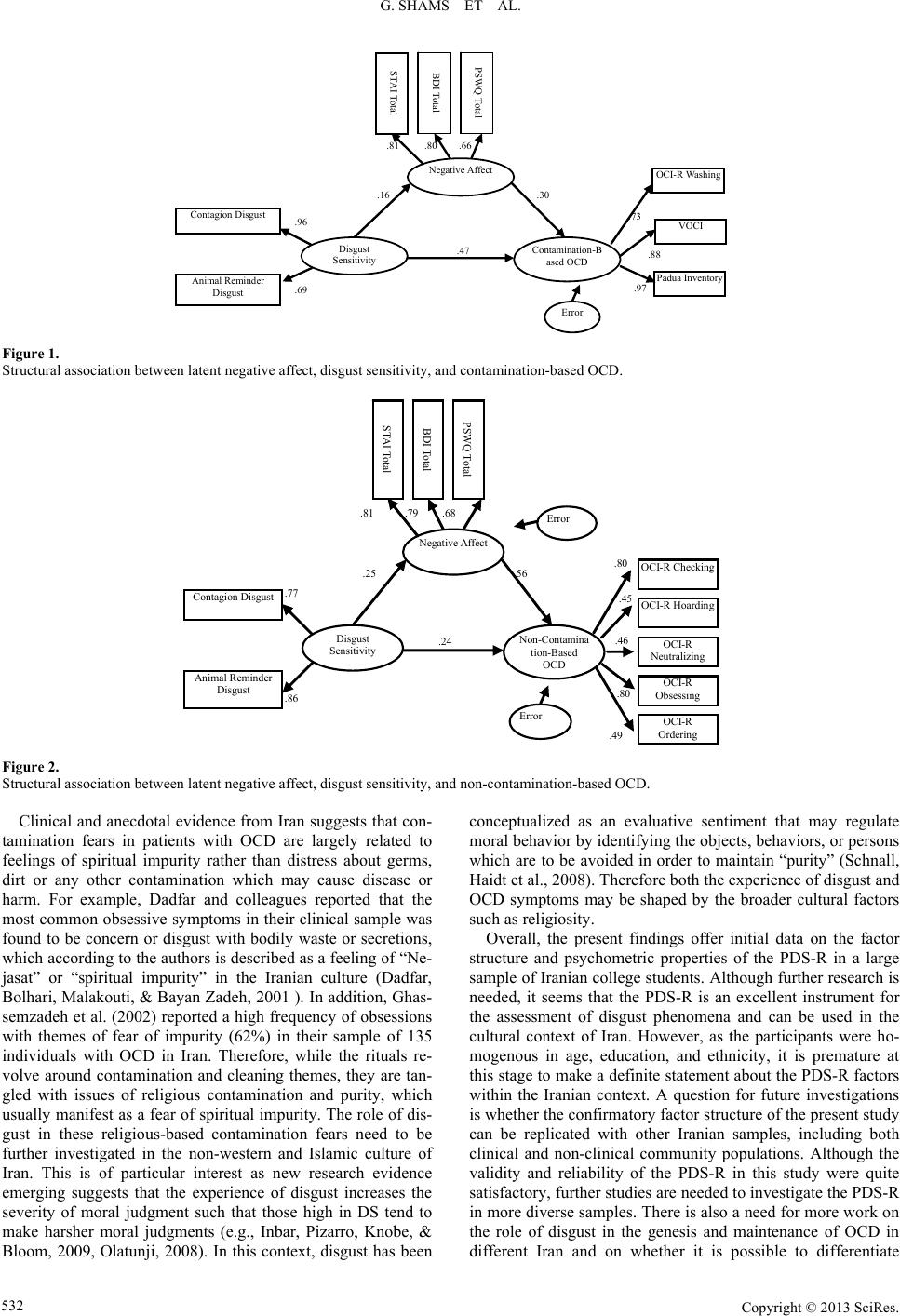

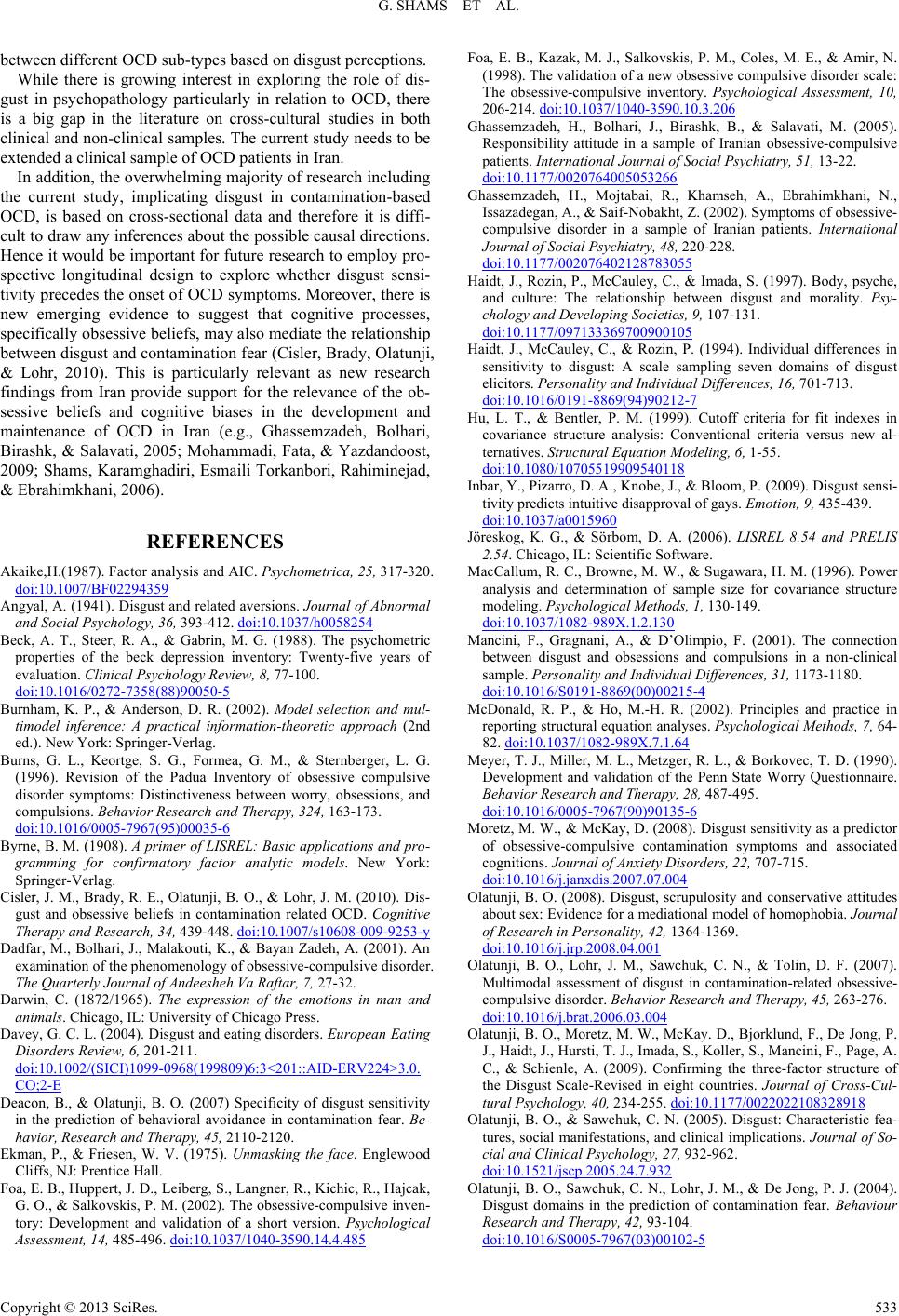

|