Advances in Applied Sociology 2013. Vol.3, No.2, 124-130 Published Online June 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2013.32016 Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 124 Dying with Meaning: Social Identity and Cultural Scripts for a Good Death in Spain Fernando Aguiar, José A. Cerrillo, Rafael Serrano-del-Rosal Institute for Advanced Social Studies (IESA-CSIC), Cordoba, Spain Email: faguiar@iesa.csic.es Received February 8th, 2013; revised Mar ch 12th, 2013; accepted March 20th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Fernando Aguiar et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In this article we examine, through six focus groups, the various arguments put forth by social actors to defend or reject the right to choose how to die, including palliative sedation, euthanasia and even assisted suicide. This qualitative technique allows us to establish the relative weight of traditional, modern and neo-modern models of coping with death in the discourses of the Spanish subjects sampled within the study, how these models are reflected in specific cultural scripts and to what extent these scripts for a good death are the product of a reflexive project of identity. Keywords: Assisted Suicide; Cultural Scripts; Euthanasia; Reflexive Identity; Spain Introduction Spain is one of the countries of the European Union (EU) that has experienced the greatest and most rapid social, political and economic changes in the last three decades (Pérez-Yruela & Serrano-del-Rosal, 1998; Harrison & Corkill, 2004). The country ceased to be a dictatorship in 1975 to become a de- mocracy whose model of transition has been emulated by other countries. Spain underwent a transformation from a rural coun- try with 23.4 percent of its active population engaging in agri- culture (Spanish National Statistics Institute, 1975) to become, in less than three decades, a post-industrial society with just 4.5 percent of its workforce in the farming sector (Spanish Ministry of Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs, 2011). It is, therefore, a society, such as those of its neighboring countries, characterized by high levels of technology and consumption. These changes, among other effects, have led to a mortality reduction in Spain, as it is shown both by the infant mortality rate, that lowered from 18.89 per thousand in 1975 to 3.2 per thousand in 1990, and the life expectancy, that increased from 77.08 years of life to 81.58. Moreover, 17.07 per cent of the population today is over 65 years of age compared to 10.45 in 1975. Not surprisingly, such far-reaching changes have affected the way in which the Spanish conceive of themselves. Spanish society now sees itself as a more egalitarian and more modern society than thirty years ago (Royo & Manuel, 2003). An im- portant indicator of these changes is undoubtedly the way the Spanish conceives of death today in general, and palliative sedation, euthanasia and assisted suicide in particular. In light of the profound social changes occurring in the last two decades, a new culture of the good death has emerged in Spain which is similar to that of other countries of the EU. In these countries a good death means, on average, being free from avoidable dis- tress and suffering, on the one hand, and choosing as far as possible how to die in a way consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards, on the other (IOM, 1997; DeSpelder & Strickland, 2005). As we shall see, however, this does not mean that this conception is uniform across the Spanish population or does not coexist with other more traditional conceptions typical of the previous decades. In that regard, Spain is not different from its neighboring countries or any other post-industrial na- tion either (Cohen, Marcoux, Bilsen, Deboosere, Van der Val, & Deliens, 2006a; Cohen et al., 2006b). Indeed, new experiences related to death that are characteris- tic of a medicalized, post-industrial society (oblivion of death, dyin g in hospitals) , and more pr ogressive legislation in relation to these issues have changed the image of Spain as a Catholic country unable to accept individual rights associated with death (Simón-Lorda, 2008). The social debate arising from dramatic cases such as the quadriplegic Ramón Sampedro who received illegal assistance to commit suicide (Guerra, 1999) or that of Inmaculada Echevarría, who after an arduous legal battle against public health authorities was disconnected from the artificial respirator that kept her alive (Simón-Lorda & Bar- rio-Cantalejo, 2008), have no doubt contributed to these changes. A study conducted by the Center for Sociological Research (CIS; Spanish acronym) as early as 1992 revealed that 78 per- cent of Spanish citizens was in favor of palliative sedation and 66 percent agreed that laws should allow doctors to end the life of a terminally ill patient who so requests it (CIS, 1992). These figures, which remained stable throughout the nineties, have experienced a notable increase in the last decade. While 62 percent of respondents supported “physicians providing the [terminally ill] a product to end their life without pain” in 1995 (CIS, 1995), this percentage rose to 70 percent in the next dec- ade (CIS, 2008, 2009). Unlike other European countries, Spain —alongside Belgium, Sweden and Italy—has experienced a remarkable increase in the acceptance of euthanasia (Cohen et al., 2006b: p. 666; Council of Europe, 2004) not only among  F. AGUIAR ET AL. the population as a whole, as we have seen, but also among health professionals (CIS, 2002). The survey data clearly point to the emergence of a new cul- ture of the good death in which palliative sedation, euthanasia, and even assisted suicide are not only put to debate, but widely supported by the population. Yet what are the central elements of this new culture? Is this changing perception of death and dying in Spain related to the development of a modern, reflex- ive notion of identity (Giddens, 1991; Mellor & Shilling, 1993; Stets & Burke, 2003)? Do elements of a pre-modern identity survive in Spanish culture, which is presumably influenced strongly by the Catholic religion? Do the perceptions of the Spanish people about the end of life fit in the models of coping with death (traditional, modern and neo-modern) proposed by Walter (1994: pp. 47-65)? Are these models reflected in specific cultural scripts, that is, socially determined representations of death that can guide individual decisions (Seale, 1998)? The perceptions and attitudes towards the notion of death are complex and therefore not readily available through survey data alone (Cohen et al., 2006a: p. 753). As Stanley and Wise (2011) have pointed out, each social configuration tries to “domesti- cate” death in its own way. Survey data indicate a clear change in Spain, but do not tell us enough about the inner nature of this change, that is, how it is perceived by the actors themselves. In this paper we aim to shed some light on the perception of death and the good death debate in Spanish society. Specifically, the objectives of this article are to: 1) Explore and sort out the discourses circulating in Spanish society concerning good death in general and palliative sedation and euthanasia in particular to establish the relationship be- tween these discourses and traditional, modern and neo-modern models of death and dying (Walter, 1994). 2) Examine in depth the justifications and arguments that arise from such discourses by means of different cultural scripts that defend or reject the right to choose how to die, including palliative sedation and euthanasia, and the notion of dignity and autonomy in the process of dying. Methods In line with the proposed research objectives and the advan- tages of qualitative methodology to address them, we chose the focus group technique. This technique is most suitable for re- constructing social discourses, understood as broad, shared representations which, in relation to our topic, are reflected in diverse narratives (scripts) grounded on cultural models about death and dying process on the one hand, and in expressions of identity (reflexive or not) of the participants on the other. Hence the focus groups are more appropriate than interviews to recon- struct cultural scripts (Martín Criado, 1997). Specifically, we took into account the place of residence (ru- ral or urban), age, educational level and gender to design our sample. Previous quantitative studies have shown that these variables bear statistically significant relationships with the defense or rejection of the right to die (Sesma, Ranchal, & Serrano-del-Rosal, 2009; Cohen et al., 2006a, 2006b). Although we did not select religion and moral attitudes as variables, they appear in the discourses as explanatory narrative elements. Regarding gender, most of the groups were mixed, with half of the participants of each gender, with the exception of group 1 (composed of advanced age, urban resident males only) and group 2 ( of advanced age, low schooling rural resident women), since we found it interesting to explore their specific percep- tions. Bearing in mind the above, we formed six focus groups as described in the Table 1. Eight participants were convened for each group, with only three absences, one in group 4 and two in group 6. However, these absences did not weaken the meetings, since the debates in both groups did not differ in their richness and duration from those registered in the other groups. The participants were re- cruited with the help of a company specialized on qualitative field work services, and each one received fifty Euros for their efforts. The discussion groups were held from 17 November to 3 December 2009: The groups were led by a moderator (one of the researchers), who ensured that the discussion progressed in as orderly a manner as possible, asked the participants questions from time to time, brought up previously debated issues to be discussed in greater depth, and raised some issues in the final leg of the discussions that had either not been dealt with or on which agreement or disagreement had not been reached. Thus, unlike other studies (Underwood, Mair, Bartlett, Partridge, Lucke, & Hall, 2009), no data were obtained by means of in-depth or semi-structured interviews. To obtain cultural scripts for a good death it is important that the process be conducted by the par- ticipants themselves without the moderator guiding the out- come. To do so, we decided to convene the groups to discuss a direct and general question that encouraged the participants to discuss the main objective of the study but did not anticipate subsequent responses: “What does a good death mean to you?” The discussions were transcribed verbatim and the transcripts analyzed with the aid of Atlas.ti version 5.2 software to relate what was said literally (textual analysis) and the process through which it was said (contextual analysis, in this case the group dynamics) to the structural dimensions of reference (dis- course analysis) (Ruiz, 2009). The original recordings as well as the literal transcription are available (in Spanish) to re- searchers upon request. Data were gathered and presented here with permission of the persons that took part in the focus groups, following the Code of Good Scientific Practices of the Spanish Council for Scientific Research (CSIC, Spanish acro- nym). Results In the following, we present a selection of the discourses Table 1. Focus groups. GroupGenderAge Educational level Habitat Approx. duration 11 Men60 - 7 5Intermediate (secondary education or similar) Urban (Granada) 96 min. 22 Women50 - 60Low (no education or primary schooling Rural (Cazorla) 94 min. 33 Mixed36 - 50High (university education) Urban (Seville) 97 mi n. 44 Mixed36 - 50Low (no education or primary s chooling) Rural (Adamuz) 106 min. 55 Mixed22 - 3 5Intermediate Urban (Malaga) 116 min. 66 Mixed18 - 25Low (no education or primary s chooling) Rural (El Rocío)97 min. Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 125  F. AGUIAR ET AL. which are grouped into two main sections: in section A we pre- sent the discourses against a good death understood as the right to choose how to die; in section B the discourses in favor of that right (including euthanasia) are showed. Section A is not divided into subsections, because the discourse is homogene- ously against the right to decide how to die. However, we em- phasize some key terms upon which the discourse focuses (de- shumanization, my life is not my own, where there is live there is hope, the denial of death). The discourses in favor are not homogeneous and we divide them into three subsections de- pending on the nature of the argument: the emotional discourse, the negative freedom discourse and the autonomy and positive rights discourse. For each discourse we indicate the group from which it proceeded and if the person being quoted is a man (M) or a woman (W). The Discourse against the Right to Choose How to Die DehumAnization The most outstanding feature of the opposing discourse is its emphasis on the dehumanization of today’s world and nostalgia for the past. The present is viewed as a progressive degradation of an idealized past, which is considered a model of a good society, or at least one that is better than today’s. According to this discourse, society in the past was better because it attached greater importance to concern and respect for others. In relation to death, this means that common values regarding the obliga- tion to care for (“deal with”) the sick and dying prevailed: M: Today, the thing is that we have become, truthfully … less responsible ... for centuries and centuries there have always been sick people, right? And because before …, in the old days, people put up with the sick ..., that is, people with few means dealt with the situation, and today, now that we can do it ... we can do it because we are more prepared, we live better. Why do we think ... that we have to get them out of the way or take them to a facility [Group 1]? In the discourse opposing the right to decide how to die, death has turned into just another way of doing business. This is manifested in the clear opposition to legalizing the right to choose because it is thought that the ultimate objective of any process that speeds up death such as euthanasia or assisted sui- cide is not to relieve the suffering of the dying, but due to some kind of economic interest that either benefits the family (in- heritances), funeral homes (revenue from burials) or the state (savings on health expenditure): M: What [euthanasia] can’t be is a trick to deceive others. I mean, a guy has a lot of money and is alone ... so, the family, when he gets sick and has been in the hospital for two months ... requests euthanasia [Group 1]. M: It is a failure of society, right? They don’t know how to give the person [the sick or dying person] a quality of life that provides even the slightest ray of hope [Group 3]. My Life Is Not My Own Most of the participants who supported the opposing dis- course had little power over their life circumstances. These were elderly people living in rural settings with a low educa- tional level who alternated between precarious jobs with long periods of unemployment, earned low wages and pensions, and lived on a day to day basis. They lived far from the centers of power and decision making, which are completely alien to them. They did not fully understand the world they lived in; either because it is very different from the world they grew up in or because they lacked the education or information to understand it, or both. These are people whose reality is unstable and pre- carious and cannot anticipate their future. The precondition of an action oriented towards the future is to have minimal control over present circumstances, or at least believe that that is so (Bourdieu, 2002; Sennett, 1998). W: But they don’t let you live they way you want to either. You live within your means, right? Or as best as you can. At least I ... I try to live within my means, I don’t live the way I want, or how I would like to live. Or how they let me live, or ... Exactly. No ... I would like to live ... to die within my means. No ... I’m not going to ask for a death ... You know? (Pause) I ... I would try to do that. For me it would be like that. I don’t know. I don’t know. You don’t live the way you want, [you live] the way you can. [...]. I would try to die within my means ... like I live. W: Dying, you’re going to die when the time comes. Really. And then … [Interrupting.] W: That’s right, if it comes … the moment … unexpectedly, then it’s time. M: Well ... That’s right. The time comes and that’s it, right [Group 6]? Where There Is Life There Is Hope According to the discourse of opposition and rejection, when the person has a chance of surviving, however small that chance may be, life must be pre served at all costs, regardless of the will of the person involved, be yourself or someone else: M: Because when the re is a ray …, a ray of …, of light, you have to grab onto it. That much we agree on [Group 1]. These narratives reveal religious faith in a miraculous recov- ery. In the discourse against the individual right to decide, the positions are Christian. Such positions are an outright denial of the sovereignty of the individual over their own lives because only God has the power to give or take life. M: I am of the opinion that God has given us life and God has to take it away. For me, life ... death must be a death with great respect and dignity. A human being can’t take a life away [Group 1]. The Denial of Death Almost all the groups attempted to avoid the discussion at all costs. To do so, the participants would at times mention the unsuitable nature of the topic being discussed: death is not an appealing subject because it is unpleasant, ugly, sad, distressful, and is therefore best not to talk about it. On other occasions, the participants stated that death is a strictly private affair and must be dealt with as such. When one is not involved, it is best to just show respect and keep quiet about it, but never express atti- tudes to death in public: W: It isn’t a pleasant topic. W: It’s a sad topic. W: […] Yeah, I think a lot…but don’t talk about it. W: Talk, people talk little about these things. W: No, no about that I don’t usually … not with my closest family or … W: Since it’s something that’s sure to happen, we don’t need to discuss it much. W: Right, and in a meeting like today, even less [Group 2]. Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 126  F. AGUIAR ET AL. Discourses in Favor of the Right to Choose How to Die In line with the results of surveys, pro-right to die discourses were more frequent than anti-right to die discourses among the participants of the focus groups. Nevertheless, as already men- tioned, a wide range of views and concerns arise from these discourses that provide the opportunity to gain insight into what drives 70% of Spanish citizens who, in 2008, stated that they were in favor of euthanasia (CIS, 2008). As we shall see, the reasons for defending such a right differ enormously. Emotional Discourse We call an emotional discourse one which supports the right to euthanasia based more on the suffering of the dying than on the individual’s autonomy to decide for him or herself. It is a discourse grounded in a subjective and emotional conception of morality (Bauman, 2000; Bauman, 1989) that is defined as an innate impulse in human beings which arises from proximity to others and that moves us to be concerned about them and to take responsibility for their welfare and happiness. Morality understood in this way belongs to the realm of emotion (Bauman, 2000). W: My father died of lung cancer ... and I asked him to be sedated, I asked him to be sedated, to have a dignified death and to sedate him because I didn’t want to see him suffer. He was sedated and died very peacefully [Group 2]. The emotional discourse is more intense among individuals with an intermediate and mid-to-low education, who are mature adults or nearing old age and live in the rural setting. This pro- file is very similar to those who sustain the discourse of rejec- tion and opposition. Although both discourses share in common the fact that they are based more on emotionality than rational- ity, the anti-right to choose how to die discourse is conditioned by negative emotions such as fear and insecurity, while the emotional discourse reflects positive emotions such as compas- sion and love: M: I was taking care of my father, and already in the last months I entered the room and asked ... I looked up and asked the Lord to remember him. I tell to you with my heart in my hand. And I think I loved my father as a son can love his father. Do you understand what I mean? And I asked it to God, day after day, and he doesn’t answer. Why? What was he doing lying there? I spoke and spoke to him, he couldn’t answer me and I burst into tears ... What was that man doing there, God of my soul? And I said, my God, what can I do [Group 1]? W: Because I remember when my grandfather was ill ... I would say ... please, let him die... the thing is that you have a hard time seeing him like that [Group 5]. Discourse Based on Negative Freedom Contrary to the previous discourse, in this one the partici- pants state that every person has the right to decide about their life and their death, and that others should respect their decision. It is therefore a discourse in which freedom is understood as negative freedom, that is, as the absence of restrictions as to the action itself, with the exception of actions that may interfere with the freedom of others (Berlin, Hardy, & Harris, 2002). M: Of course, that ... if you live the way you want, without bothering anyone, then no one should bother you when you are going to die [Group 1]. W: I agree ... everyone should do what they want [Group 3]. W: I think they should let people who can’t ... move or any- thing, and if they want to die let them do it. Because they can’t live like that [Group 6]. This is the discourse of self-ownership (Brenkert, 1998) which holds that we are the owners of our bodies and therefore of our lives. In today’s society, however, the rights related to death and dying (particularly euthanasia and assisted suicide) are an unmet social demand. W: Let everyone decide about their body. Whatever they want. Whatever they wish. Whatever … they think is best [Group 3]. W: Who should decide for me if I’m living? Why don’t they listen to me if it’s about me [Group 4]? The notion of self-ownership enters into conflict with estab- lished religious ideas, especially those of the Catholic Church, which not only negates the notion that one is master of oneself, but is also opposed to discussing euthanasia or assisted suicide. M: Yeah, I mean, that’s the way it should be. Sure. A Catho- lic who follows that ..., that religion, well ... he can do whatever he wants, but ... religion shouldn’t intervene to tell the rest of us what the morally right thing to do is. W: No, religion. The thing is that religion in this country, it’s that it is ... restrictive and to me that doesn’t seem right, be- cause I ... I agree that everyone can be Catholic and I think that’s fine, but ... everyone should be able to do what they want to do and that’s all there i s to it. W: The Catholics want to be respected about everything but they don’t respect others or how others think. They don’t re- spect us. Come on, I’m Catholic ... I’m [Catholic] too, but they don’t respect those things [Group 3]. Citizens’ Discourse: Autonomy and Positive Rights Finally, this discourse is very similar to the former one, al- though it has nuances of some importance that set it apart. The discourse of citizens encompasses all the tenets of the discourse that advocates negative freedom, but takes it further to its ulti- mate consequences, proposing what we could call with caution a “social project”. In the citizens’ discourse, freedom of choice is more than a right, it is a way of life, or at least a way of life that is characteristic of contemporary societies; something which truly shapes citizenship: W: In this life we must continually choose one path or an- other, one path or another, one path or another, you have to know that. W: We have to continually decide and that [how to die] is one of the decisions we must make ... It’s hard, horrible, but we have to do it [Group 3]. W: The thing is that euthanasia ... You decide for yourself: “I don’t want medication, I don’t want surgery”. Nature takes its victim ... and someone has to help [Group 3]. The citizens’ discourse shares the basic tenet of freedom of choice and the need to eliminate obstacles to permitting citizens to decide, but it elevates the discourse to the level of public concern in an almost civilizing way: in the life that we live, we have to choose our path. In this sense, choosing is not only a right but a duty. In the discourse that emphasizes negative freedom, individu- als often speak from the viewpoint of the singular “I”, or at the very most from an impersonal perspective when the argument moves from the expressive to the denotative (“death is not to be spoken about”, “if legislation needs to be made, let it be made”). Citizens’ discourse is also expressed in these terms, but at times, Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 127  F. AGUIAR ET AL. as in the above example s, the “I” gives way to “we”: “We have to continually decide and that is one of the decisions we must make”; a “we” that clearly refers to all citizens; to society as a whole. For this reason we say that the citizens’ discourse ex- presses a social and not just an individual project; the notion of a good society, a common good and, therefore, a good death as a common good. M: I know a lady who was diagnosed with cancer ... that is, a brain tumor and she decided not to have surgery and not to take ... medication or chemo, no radio, no nothing and she died when she had to die, period [...]. That’s euthanasia that she practiced on herself [Group 3]. It should come as no surprise that this discourse chiefly arises among those who have most control or believe that they have control over their lives. For this reason, it is found almost exclusively among the young or middle-aged; those who are building or are in the process of building their life project. It is a discourse that is more frequent among urban dwellers—not to mention city dwellers—than those living in villages, where pressure by the community is stronger and individual initiatives fall under greater pressure (Sennett, 2008). Moreover, cities provide better and broader opportunities where life is perceived as an open menu with multiple options. In particular, the citi- zens’ discourse is more common among individuals with a high educational level and, more rarely, high income. This is so not only because such an elaborate discourse requires good linguis- tic proficiency, but because understanding the complex world in which we live and die (to adapt and even take advantage of it) requires having a significant amount of knowledge and infor- mation. Not surprisingly, people who adhere to the citizens’ discourse are those who hold more stable and better paying jobs and report more satisfaction. Discussion Depending on their age, beliefs, educational level, perception of themselves as people who make crucial and independent decisions concerning their lives or not, and place of residence, the participants in the focus groups expressed a variety of posi- tions regarding their notion of a good death and the individual rights that ensure such a death. At the very beginning we found the logical idealization of what one would hope death to be— painless, surrounded by loved ones at home and at a late age after having lived a full life—which coincides with the findings of other studies both in Spain (Marí-Klose & de Miguel, 2000) and elsewhere (Long, 2004: p. 925; Lee, Jo, Chee, & Lee, 2008). However, once the participants realized that this ideal cannot be chosen at will, two different accounts emerged: one which was more homogeneous and opposed to the view that a good death involves an individual’s right to decide about his or her own death (and body); and a more heterogeneous one that supported free, individual choice for various reasons. These discourses could be organized by means of cultural models of dying according to age, social class, education, and the habitat of individuals that took part in the focus groups (gender, however, did not make any difference in our groups at all). As it is well-known, these cultural models on death in post-industrial societies can be divided into three ideal types: traditional, modern and neo-modern (Walter, 1994: pp. 47-48). Traditional model develop in community-based social contexts, and continue to survive in developed societies where death has a large social presence (death is not hidden) and in which relig- ion is the central authority. In the modern model, however, death is medicalized, kept at a distance, hidden away from eve- ryday life. Here medicine is the authority and death is consid- ered a private matter which must not be talked about. Finally, the neo-modern model is a “revival” of death, which is consid- ered another channel by which to develop oneself—a reflexive self (Giddens, 1991)—and control one’s own death: the when, how and where one wants to die. In this case, death is no longer a purely private affair, but becomes a public issue that must be discussed and in which the self has full authority. These models, which are “ideal types”, may be reflected or embodied differently in cultural scripts that determine the dis- courses about death depending on the cultural traditions of each country. Indeed, one of the central features in post-industrial societies is the existence of multiple cultural scripts (Seale, 1998; Long, 2004). Thus, in Britain and other English-speaking countries Seale (1998) found four cultural scripts: modern medicine, revivalism, anti-revivalism and the religious script. The traditional elements of Walter’s ideal type are related to anti-revivalist and religious scripts that oppose the notion of a self that takes charge of one’s own death, either because they prefer “a closed awareness” of dying (anti-revivalism) or be- cause they believe that the decision to die is in the hands of God (religious scripts). In British culture, these scripts are relics of the past and associated with low-income individuals with little education. As Seale notes, religious and anti-revivalist scripts are related to “those who are not well-schooled in the kind of reflexivity self-aware projects of identity that Giddens describes” (quoted by Long, 2004: p. 916). The scripts that appeal to modern medicine are in conso- nance with the modern ideal type, in which the project of per- sonal identity, although reflexive, does not consider decisions about death as an option for personal development and are therefore left up to physicians (i.e. medical technology). In contrast, revivalist scripts are a reflection of the neo-modern ideal type in which the patients’ reflexive self “colonizes” medicine, transforming it into patient-centered medical care and making the process of dying—the how, when and where—an inalienable right (Seale, 1998: p. 94). Although the traditional, neo-modern and modern ideal types are present in post-industrial countries, they are reflected in each country differently through the four scripts proposed by Seale (Seale, 2000). For example, two countries as different as Japan and the USA, but which share common elements, also reveal traditional scripts determined by religion, albeit they are expressed differently due to the specific religious traditions of each. In Japan, the religious and anti-revivalist scripts are not a relic of the past: the Japanese combine a religious sense of life after death (Shinto, Buddhist or Confucian) in a vague way with cultural elements of a society in which science plays a very important role (Long, 2004: p. 917). In the USA, however, this synthesis between religious and modern views is not as clear. While the revivalists claim the right to decide how, when and where they want to die, people with strong Christian, Mus- lim or Jewish beliefs fully reject the notion that human beings should determine issues related to life and death: “They found unacceptable to stop aggressive treatment, since death is some- thing only God decides” (Long, 2004: p. 921). In the case of our study the discourses on death can also be identified as traditional, modern and neo-modern models. The perception of death and its relationship or not to a reflexive identity has its own characteristics in the individuals sampled Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 128  F. AGUIAR ET AL. within the study. In general, however, their discourse is closer to the discourses found in anglophone countries than to those present in a country as developed and yet as religious as Japan. The influence of religion has dropped sharply in Spain since it again became a democratic country four decades ago (CIS, 2008, 2009; Brañas, García-Muñoz, & Neuman, 2011). Quanti- tavie studies have shown that in Spain the traditional beliefs on death are no longer predominant, although it is widely present and remains the most homogeneous in our groups. Traditional model is reflected in a script that is clearly more religious than anti-revivalist. Indeed, we have not found an anti-revivalist discourse that is not also religious. The traditional ideal type of Walter, which is present in our groups in its purest form, is manifested in the religious traditions of the country; traditions which provide subjects with the intellectual tools they need to oppose the right to choose how to die. The notion that one’s life belongs to God and that people’s bodies are not their own, the absence of a reflexive project of identity, the conviction that while there is life there is hope, the rejection of the patient’s autonomy to decide when, how and where to die are all charac- teristic of a religious script, which in our study is not a relic of the past even if it is a minority view. However, it is a fairly sizeable minority that has been estimated at about 25 percent of the population in quantitative studies (CIS, 2008); a much smaller percentage than those who declare themselves to be Catholic. As we have seen in the discourses, this indicates that many of the individuals sampled who declare themselves to be Catholics are, at the same time, revivalists. Indeed, the majority of discourses support the right to choose how to die, but they are also more heterogeneous than those based on the traditional model. We have found a clear transi- tional revivalist script: those who support the right to decide the way to die either by euthanasia or assisted suicide out of com- passion. From the standpoint of their social composition, these individuals are very similar to those who defend traditional positions in that they have low incomes and educational levels, live in rural environments, their identity is not reflexive and they do not conceive of the decision to die as part of their per- sonal process of development. However, when faced with a long and painful illness, they support euthanasia out of com- passion for the patient and their families when the patient has lost consciousness. They do not appeal to rights or freedoms, but to the emotional aspects of the end of life. Given their lack of education and conceptual references to justify their position such as freedom, rights, or autonomy, these people often resort to films (especially The Sea Inside by Alejandro Amenábar), examples appearing in the media or their immediate environ- ment to strengthen their position. As in the case of religious scripts, in this transitional script from the traditional to the modern we also encounter individuals who are not well- schooled in reflexivity self-aware projects, but who take part in a modern conception of death through the emotions that arise from a near death process rather than a rational and reflexive justification. The other discourses support the right to die fit well into the modern and neo-modern ideal types. In both cases we find a similar social profile, but with differences with regard to educa- tional level. These are people who live in an urban environment, and are usually young or, at best, mature adults (there are few elderly people) and who advocate a conception of the body based on self-ownership and, therefore, the sovereignty of the patient, thus suggesting that they have a clearly reflexive pro- ject of identity, that is, they are citizens who are aware of their rights. However, those we include in the modern model have a lower educational level than that of the neo-moderns—in the first group we find discourses by those who have a secondary education, while those in the second group have a univer- sity-level education. This is clearly reflected in both their pro- jects of identity and the scripts that guide their discourses. As we have seen, the modern ideal type is manifested in discourses in which negative freedom forms the core of their argument. These are disc ourses guide d by a revivalist script, but in which there is no opposition to the medicalization of patients if the patient agrees to delegate authority to doctors. Although the identity is reflexive, it is only partial as it does not dwell much on aspects related to personal development that involve deci- sions about death. Rather, it is a discourse that revolves around the notion of “live and let live”, including the end of life in this freedom. The neo-modern model is also embodied in a revivalist script, but with interesting nuances that differentiate it from the above model. This discourse does not revolve around the notion of negative freedom, but is instead rather a question of building a self who has a constant need to decide and choose; a multiple and diverse self. These subjects have—or believe they have— full control over a life that is purely choice and in which one day they must face the ultimate choice of how and when to die; a decision that must be taken autonomously. It is not only a question of live and let live, but of defending a positive free- dom to do with one’s life what one wishes (even it means tak- ing one’s own life) for we are own masters. The private and the public merge in these cases (Walter, 1994: p. 48) and the self becomes a “we” that is not the “we” of traditional communities, but of citizens’ rights. Conclusion Most European Union countries support the notion of a good death as being free from avoidable distress and suffering and having the right to choose how to die, especially with regard to palliative sedation and euthanasia. As some quantitative studies have shown (CIS, 2008; Cohen et al., 2006a, 2006b) Spain is no exception. Although a large majority of Spaniards continue to define themselves as Catholics, religion is no longer the chief determinant for defending the notion of a good death that re- spects the right to choose how to die (CIS, 2009). In spite of the similarities, however, there are many differences across Euro- pean countries given that “each country will have its own de- bate, influenced by its cultural backgrounds” (Cohen et al., 2006a: p. 754). For this reason, more country-specific, qualita- tive research is needed. This has been the objective of this arti- cle as there is ample evidence from Spanish and European sur- veys that the Spanish support respecting the right to choose one’s own death, but there are few qualitative studies on the subject. The qualitative study presented here reveals that the social changes occurring in Spain in recent decades are reflected in the discourses of the individuals within our study. The tradi- tional, modern and neo-modern ideal types are presented in the discourses, but reflected in sometimes confusing cultural scripts. Firstly, it is clear that the traditional ideal type, which is em- bodied in a religious script, is by no means a relic of the past. But it is also true that on occasion this script clearly reveals elements of the modern medicine script. On the other hand, Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 129  F. AGUIAR ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 130 there is no anti-revivalist script, suggesting that the scripts that emerge from the discourses are clearly polarized into religious and revivalist scripts. The anti-revivalist and modern medicine scripts that Seale finds in Britain are divided the individual sampled within the study into religious and revivalist scripts. In turn, the revivalist script reveals a confusing mix of justifica- tions depending on the sociodemographic characteristics of the individuals who participated in the focus groups (particularly age, habitat and educational level seem to explain these differ- ences to a larger degree). This polarization can be explained by the rapid social changes that Spain has witnessed in just a few years; changes that have also affected the notion of death, but which have left little time for their discussion and assimilation. For this reason, we have also found in this study that a clear, reflexive project of identity which considers the right to die as part of one’s personal development occurs only among more highly educated individuals (university graduates). On the other hand, it should be noted that in regard to identity, the gender variable has had no influence on the discourses of the various focus groups. We are aware of the limitations of the present study due to both its exploratory character and to the fact there are not many qualitative data on good death in Spain that permit us to con- trast our own findings. Further qualitative research would be needed then to explore these findings as qualitative studies on social identity and cultural scripts for a good death in Spain having not reached theoretical saturation. In this respect, it would be especially important to look further into the question of gender and a good death, because the present study does not allow us to firmly claim that there are no real gender differ- ences regarding good death conceptions in Spain. That will be one of our main research targets in the future. REFERENCES Bauman, Z. (1989). Modernity and the holocaust. Cambridge: Polity Press. Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press Berlin, I., Hardy, H., & Harris, I. (2002). Liberty: Incorporating four essays on liberty. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bourdieu, P. (2002). Counterfire: Against the tyranny of the market. London: Verso. Brañas, P., García-Muñoz, T., & Neuman, Sh. (2011). Intergenerational transmission of religious capital. Evidence from Spain. Revista In- ternacional de Sociología, 69, 649-677. doi:10.3989/ris.2010.06.28 Brenkert, G. (1998). Self-ownership, freedom, and autonomy. The Journal of Ethics, 2, 27-55. doi:10.1023/A:1009786331882 CIS (1992). Barómetro de opin i ón . Estudio n 1.996. Madrid: CIS. CIS (1995). Perfiles actitudinales de la población española. Estudio nº 2.203. Madrid: CIS CIS (2002). Actitudes y opiniones de los médicos ante la eutanasia. Estudio nº 2.451. Madrid: CIS CIS. (2008). Religiosidad. Estudio nº 2752. Madrid: CIS CIS. (2009). Atención a pacientes con enfermedades en fase terminal Estudio nº 2803. Madrid: CIS Cohen, J., Marcoux, I., Bilsen J., Deboosere, P., Van der Wal, G., & Deliens, L. (2006a). European public acceptance of euthanasia: Socio-demographic and cultural factors associated with the accep- tance of euthanasia in 33 European countries. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 743-756. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.026 Cohen, J., Marcoux, I., Bilsen J., Deboosere, P., Van der Wal, G., & Deliens, L. (2006b). Trends in acceptance of euthanasia among the general public in 12 European countries (1981-1999). The European Journal of Public Health, 16, 663-669. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckl042 Council of Europe (2004). Euthanasia: National and European per- spectives. France: Council of E urope. DeSpelder, L. A., & Strickland, A. L. (2005). The last dance: Encoun- tering death and dying (6th ed.) New York: McGraw Hill. Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Guerra, M. J. (1999). Euthanasia in Spain: The public debate after Ramon Sampedro’s case. Bioethics, 13, 426-432. doi:10.1111/1467-8519.00170 Harrison, J., & David C. (2004). Spain: A modern European economy. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. IOM, Institute of Medicine (1997). Approaching death: Improving care at the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Lee, H. J., Jo, K. H., Chee, K. H., & Lee, Y. J. (2008). The perception of good death among human service students in South Korea: A Q-methodological appro ach. Death Studies, 32, 870-890. doi:10.1080/07481180802359797 Long, S. O. (2004). Cultural scripts for a good death in Japan and the United States: Similarities and differences. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 913-928. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.037 Marí-Klose, M., & de Miguel, J. (2000). El canon de la muerte. Política y Sociedad, 35, 11 5-143. doi:10.1177/0038038593027003005 Martín Criado, E. (1997). El grupo de discusión como situación social. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológi cas, 79, 81-112. Mellor, P. A., & Shilling, C. (1993). Modernity, self-identity and the secuestration of death. Sociology, 27, 411-431. Pérez-Yruela, M., & Serrano-del-Rosal, R. (1998). Contemporary Spanish society: Social, institutional and cultural change. In T. Law- lor, & M. Rigby ( Eds.), Contemporary Spain. London & New York: Longman Royo, S., & Manuel, P. C. (2003). Spain and Portugal in the European Union: The first fifteen years. London: R ou tle dg e. Ruiz, J. (2009). Sociological discourse analysis: Methods and logic. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum Qualitative Social Re- search, 10, 26. Seale, C. (1998). Constructing death: The sociology of dying and be- reavement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511583421 Seale, C. (2000). Changing patterns of death and dying. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 917-930. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00071-X Sennett, R. (1998). The corrosion of character: The personal conse- quences of work in the new capitalism. New York: Norton. Sennett, R. (2008). The uses of disorder: personal identity and city life. New Haven: Yale University Press. Sesma, D., Ranchal, J., & Serrano-del-Rosal, R. (2009) Opiniones de la ciudadanía andaluza ante la legalización de la eutanasia. In A. M. Jaime-Castillo (Ed.), La sociedad andaluza del siglo XXI. Diversidad y Cambio (pp. 185-204). Sevilla: Ce ntro de Es t u dios Andaluces. Simón-Lorda, P. (2008). Muerte digna en España. Derecho y Salud, 16, 75-94. Simón-Lorda, P., & Barrio-Cantalejo, I. M. (2008). El caso de Inmaculada Echevarría: Implicaciones éticas y jurídicas. Medicina Intensiva, 32, 444-451. doi:10.1016/S0210-5691(08)75721-8 Spanish Ministry of Environment, and Rural and Marine Affairs (2001). Anuario de Estadística del Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Rural y Marino 2009. Madrid: MARM. Spanish National Statistics Institute (1975). Encuesta de población activa. Madrid: INE. Stanley, L., & Wise, S. (2011). The domestication of death: The do- mestication thesis and domestic figuration. Sociology, 45, 947-62. Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. (2003). A sociological approach to self and identity. In M. R. Leary, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 12 8-152). New York: The Guilf o rd Press. Underwood, M., Bartlett, H. P., Partridge, B., Lucke, J., & Hall, W. D. (2009). Community perceptions on the significant extension of life: An exploratory study among urban adults in Brisbane, Australia. So- cial Science & Medicine, 68, 496-503. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.002 Walter, T. (1994). The Revival of Death. London: Routledge.

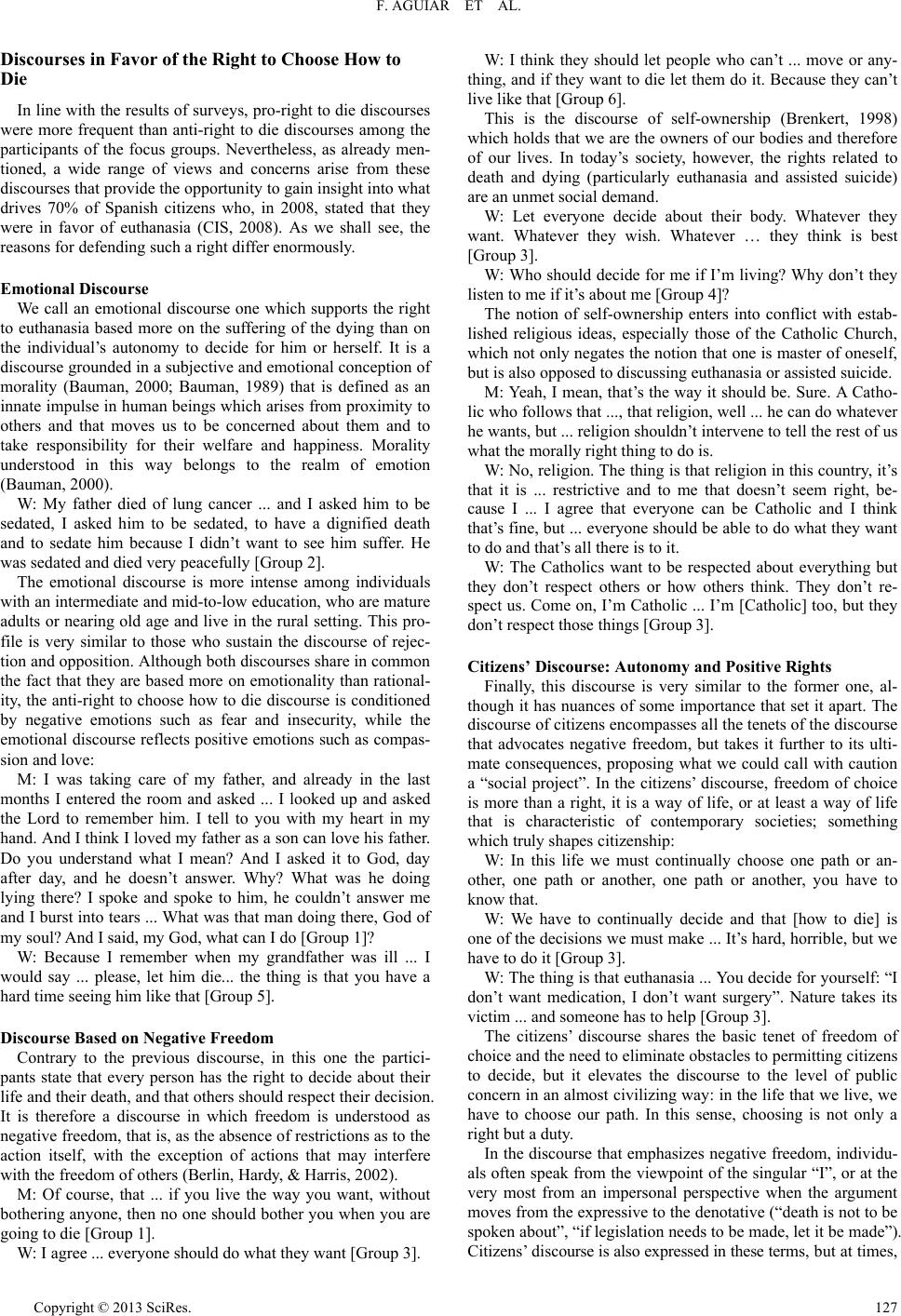

|