Advances in Physical Education 2013. Vol.3, No.2, 103-110 Published Online May 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ape) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2013.32018 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 103 Underserved Adolescent Girls’ Physical Activity Intentions and Behaviors: Relationships with the Motivational Climate and Perceived Competence in Physical Education Alex C. Garn1, Nate McCaughtry2, Bo Shen2, Jeffrey Martin2, Mariane Fahlman2 1School of Kinesiology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, USA 2Division of Kinesiology, Health, and Sports Studies, Wayne State University, Detroit, USA Email: agarn@lsu.edu Received February 23rd, 2013; revised March 25th, 2013; accepted April 8th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Alex C. Garn et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This study investigated underserved adolescent girls’ perceptions of the motivational climate in relation- ship to their perceptions of competence in urban physical education, self-reported physical activity, and future physical activity intentions. A total of two-hundred-seventy-six underserved (i.e., minority, urban, high poverty) adolescent girls completed questionnaires and a multi-step approach was used to test these relationships. First, a trichotomous model of the perceived motivational climate was tested using confir- matory factor analysis and results suggested a good fit of the data. Structural equation modeling analyses were then used to test both direct and indirect relationships between the perceived motivational climates in physical education, perceived competence in physical education, and physical activity outcomes. Find- ings revealed that the relationship between the perceived motivational climates and physical activity out- comes were best understood when perceived competence in physical education was accounted for as an intermediary factor. Keywords: Perceived Competence; Urban Physical Education; Motivational Climate Introduction The social environment in physical education (PE), espe- cially at the secondary level, has often been criticized for fa- voring males to the detriment of females (Larsson, Fagrell, & Redelius, 2009). Reinforcing physical activity stereotypes, curricular choices and class structures geared toward male ag- gression, and lowering performance expectations based on gender are all examples of how the social environment in PE can potentially reduce girls’ feelings of physical competence and engagement in PE (Domangue & Solmon, 2010; McCaughtry, 2004). This type of PE environment can also make physical activity less appealing to girls (Kirk & Tinning, 2005). The authors of both empirical studies (e.g., McKenzie, Marshall, Sallis, & Conway, 2000) and systematic reviews (e.g., Fair- clough & Stratton, 2005) suggest that adolescent boys are more apt to be physically active than girls in and out of PE. Some researchers suggest that only about a quarter of girls in high school meet recommended physical activity guidelines (Butcher, Sallis, Mayer, & Woodruff, 2008). Underserved populations (i.e., ethnic minority, inner-city, low socio-economic status) are at an even greater risk for low levels of physical activity (Gomez, Johnson, Selva, & Sallis, 2004; Gordon-Larsen, McMurray, & Popkin, 2000; Martin & McCaughtry, 2008). These authors suggest that living in pov- erty, limited access to physical activity space, and neighbor- hood safety concerns are formidable barriers to physical activ- ity for many underserved adolescents. The physical activity challenges that many underserved adolescents face outside of school places urban PE in a unique position. Specifically, urban PE is frequently one of the primary settings for underserved adolescents to obtain physical activity (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2000; Martin & McCaughtry, 2008). Because the social envi- ronment in PE is often male-centered, underserved adolescent girls may be exposed to an especially high risk of physical in- activity. Motivationa l Climate Achievement goal theory is a framework that can potentially help explain and predict relationships between social structures in PE and physical activity outcomes in underserved adolescent girls (Ames, 1992; Nicholls, 1989; Roberts, 2001). In achieve- ment goal theory, the motivational climate represents situ- ational factors associated with achievement cognitions, feelings, and behaviors (Solmon, 1996). Specifically, students can view the learning environment as emphasizing mastery, performance, or performance avoidance goal structures (Ames, 1992; Midg- ley, 2002; Roberts, 2001). A mastery climate focuses on class structures that stress personal competence, self-improvement, effort/persistence, understanding, and learning. Making mis- takes is considered a normal aspect of learning in a mastery climate. In other words, a mastery climate creates an environ- ment that supports individuals when they make mistakes by using the process to guide improvement and learning. Mastery climates are considered to be the most adaptive environments  A. C. GARN ET AL. for obtaining achievement outcomes (Braithwaite, Spray, & Warburton, 2011; Roberts, 2001). A performance climate features class structures that empha- size showing high ability, competition, winning, and positive social comparison (Ames, 1992). Duda and Ntoumanis (2003) describe a performance climate in PE as a proving environment of physical competence and ability. In a performance climate, high ability is often demonstrated by winning with minimized effort (Nicholls, 1989). A performance avoidance climate em- phasizes class structures that focus on the avoidance of showing low ability, losing, or receiving poor social comparisons. Mis- takes are often equated to low ability and failure in a perform- ance avoidance climate. In other words, a performance avoid- ance climate stresses a culture of protecting physical compe- tence. Thus, motivational climates focus on improving (i.e., mastery), proving (i.e., performance), and/or protecting (i.e., performance avoidance) ability. A majority of the research focusing on the motivational cli- mate in PE has not made the performance climate and per- formance avoidance climate distinction (e.g., Wallhead & Ntoumanis, 2004; Wang, Liu, Chatzisarantis, & Lim, 2010). Achievement goal theorists have made convincing arguments for the need to capture the approach-avoidance distinction in personal achievement goal orientations (Elliot, 1999). Midgley (2002) has extended this argument to the investigation of moti- vational climates. In a series of studies in classroom settings, Midgley and colleagues demonstrated the construct validity and reliability of measuring a trichotomous model of the perceived motivational climate that includes mastery, performance, and performance avoidance goal structures as well as the discrimi- nate validity between goal structures and psychological goal orientations (see Midgley et al., 2000). The need to make the distinction between performance and performance avoidance climates is based on theoretical and measurement issues. Tradi- tionally, achievement goal theorists have used a dichotomous model (i.e., mastery and performance) and outline the maladap- tive nature of performance climates in relation to achievement outcomes (Ames, 1992). Both Elliot (1999) and Midgley et al. (2000) have argued that: 1) aiming/supporting normative com- petence can be adaptive in some cases; 2) goal structures that support normative competence are different than goal structures that stress the avoidance of normative incompetence; and 3) performance goals/climates are generally related to negative outcomes when they are measured with items that tap the avoidance of normative incompetence. There is clearly a need to examine different models of the motivational climate more closely. Motivati on al Climate and P h ysi cal Activity The emphasis on improvement, effort/persistence, and intrin- sic motivation within a mastery climate is theorized to regulate physical activity behavior in PE (Parish & Treasure, 2003) and trigger plans for future physical activity (Biddle et al., 1999; Braithwaite et al., 2011; Ntoumanis & Biddle, 1999). Multiple researchers have reported a positive relationship between per- ceptions of a mastery climate and students’ intentions to be physically active outside of PE (Biddle et al., 1999; Ntoumanis & Biddle, 1999) or engagement in future fitness activities in PE (Domangue & Solmon, 2010). Parish and Treasure (2003) re- ported a direct relationship between perceptions of a mastery climate and physical activity in PE: however, only a small per- cent of the variance (i.e., 3%) was accounted for. In a meta- analysis study of motivational climate intervention studies in PE, Braithwaite et al. (2011) reported a moderate effect size (g = .49) in the relationship between mastery climate interventions and health/fitness outcomes (e.g., exercise frequency, cardio- vascular fitness). Parish and Treasure (2003) did not find a relationship be- tween perceptions of a performance climate in PE and physical activity with a sample of adolescent students. However, an argument can be made that because most researchers in the physical domain have measured perceptions of performance climates with a combination of approach and avoidance items/ subscales, the relationship between a performance climate and physical activity outcomes is clouded. More investigation is needed to explore how perceptions of performance climates, when approach and avoidance distinctions are made, relate to physical activity outcomes. When students believe they are physically competent in PE, they are more likely to develop positive attitudes toward physi- cal activity (Silverman, 2005), have intentions to be physically active (Sproule, Wang, Morgan, McNeil, & McNorris, 2007), and participate in physical activity (Sebiston & Crocker, 2008). Girls appear to be especially cognizant of perceived compe- tence when making their physical activity choices in and out of PE (Ennis, 2011). Kavussanu and Roberts (1996) report that the focus on self-improvement in mastery climates create realistic expectations that allows students to develop and maintain higher levels of perceived competence. More recent research has provided support for the link between perceptions of the motivational climate and perceived competence in PE (Do- mangue & Solmon, 2010; Ntoumanis, 2001). There has been limited work to date that has investigated the motivational climate in urban PE settings (Wright, Li, & Ding, 2007). Diverging from traditional achievement goal theory assumptions, Wright and colleagues reported that both percep- tions of a mastery climate and performance climate in urban PE had positive relationships with a sense of belonging in PE. Examining perceptions of the motivational climate in urban PE in relationship to perceived competence and physical activity outcomes is especially warranted with underserved adolescent girls because PE often represents a crucial physical activity opportunity. The Present Study Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate un- derserved adolescent girls’ perceptions of the motivational climate in relationship to their perceptions of competence in PE, self-reported physical activity behaviors, and future intentions for physical activity. A multi-step approach was used to test these relationships. The first step was to examine the construct validity and reliability of the trichotomous (i.e., mastery; per- formance approach; performance avoidance) model of the per- ceived motivational climate. The second step was to test the direct relationships between the perceived motivational climate and physical activity outcomes without accounting for per- ceived competence in PE. We hypothesized that direct rela- tionship between the perceived motivational climate and physical activity outcomes would produce a limited model, especially in highlighting the relationship between perceptions of the two performance climates and physical activity outcomes and overall explained variance. The third step was to test the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 104  A. C. GARN ET AL. direct and indirect relationships among the perceived motivi- tional climate, perceived competence in PE, and physical ac- tiveity outcomes. We hypothesized that adding perceived com- petence in PE would produce a more robust understanding of the relationships between the motivational climate in urban PE and physical activity outcomes in underserved adolescent girls. It should be noted that achievement goal orientations were not measured. The goal of this paper was to examine PE related factors associated with physical activity outcomes. Achieve- ment goal orientations are considered more general psycho- logical constructs that are established across a number of dif- ferent contexts (Duda, 2005). In other words, achievement goal orientations develop from an array of social contexts (e.g., classroom, family, peers) whereas motivational climates and perceived competence in PE are more closely linked to the PE environment. Duda (2005) also reports that while there is likely interactive play between climates and achievement goal orien- tations, there is not strong evidence for this interaction in the current literature. Similarly, she notes that correlations between motivational climates and achievement goal orientations are typically low. On the other hand, there is strong evidence for the relationship between motivational climates and perceived competence (Domangue & Solmon, 2010; Kavussanu & Rob- erts, 1996; Ntoumanis, 2001) as well as perceived competence and physical activity outcomes (Sebiston & Crocker, 2008). Method Participants an d Se tti n g Participants were two-hundred seventy six (N = 276) under- served adolescent girls from five different inner-city high schools in a large urban school district in the Midwest. Students in the sample were in grades 9-12 and had a mean age of 15.76 (SD = 1.34). The ethnic/racial breakdown of the sample was 72% African American, 19% Hispanic American/Latina Ame- rican, 2% Asian American, 1% American Indian/Pacific Is- lander, and 6% Other. The large urban school district faced numerous barriers including arguably the high dropout rate in the US and severe economic challenges (Swanson, 2008). All students were enrolled in PE. PE classes met three times per week for 55 minutes per class at all five schools. The Exemplary Physical Education Curricu- lum (EPEC; Michigan Fitness Foundation, 2005) was the man- dated district-wide curriculum used in all PE classes. EPEC focuses on personal conditioning, wellness, lifelong physical activities, and social development. The curriculum was aligned with the NASPE (2004) content standards for quality physical education. The physical educators (n = 5) had an average of 21.49 (SD = 3.16) years of teaching experience and received professional development training for EPEC. Measures Motivational climate. Perceptions of the motivational cli- mates in PE were measured with the classroom structures in- ventory of the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales (PALS; Midgley et al., 2000). The classroom structures inventory con- sists of three subscales: mastery goal structures (6 items), per- formance goal structures (3 items), and performance avoidance goal structures (5 items). Minor adaptations were made to the PALS to better represent PE goal structures. Sample items of the mastery goal structures subscale include “In PE class, it is really important to improve” and “In PE class, it is really im- portant to understand the activities, not just perform them”. Sample items of the performance goal structures subscale in- clude “In PE class, doing better than others is the main goal” and “In PE class, being the best player is really important”. Sample items of the performance avoidance goal structures subscale include “In PE class, it is really important not to make mistakes in front of other students” and “In PE class, it is really important to avoid losing to other students”. Items were meas- ured on a five point scale (1 = not at all true; 5 = very true). Perceived competence in PE. Four items were used to measure students’ perceived competence in PE (Xiang & Lee, 1998). “How good are you in PE” and “How good are you compared to others in your PE class” are sample items. A five point scale (1 = poor; 5 = very good) was used to measure each item. Xiang and Lee reported appropriate levels of reliability with PE students. Physical activity intentions. Intentions for physical activity were measured with the following two items: “I intend to be physically active everyday next week” and “I am planning on being physically active everyday next week”. The two items were measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). These two items have been used in previous school-based studies examining physical activity intentions (e.g., Rhodes, Macdonald, & McKey, 2006). Physical activity. The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A) was used to measure physical activity (Kowalski, Crocker, & Kowalski, 1997). The eight items of the PAQ-A use a seven day recall format (e.g., “In the last seven days, on how many days right after school did you do sports, dance, or play games in which you were very active”). For each item, adolescents are asked to identify how many days in the past week they were physically active (i.e., 0, 1 - 2, 3 - 4, 5 - 6, 7 or more). The first item consists of a physical activity check- list containing approximately 20 different physical activities. The mean of all eight items for each individual student was used as a total physical activity score. The PAQ-A has demon- strated sound reliability, construct validity, and concurrent va- lidity (Kowalski et al., 1997). Procedures First, permission was granted by the University Institutional Review Board, school district, and teachers to conduct the cur- rent study. Next, parents provided informed consent and stu- dents provided ascent. A trained research assistant who was familiar with the PE teachers and had prior experience admin- istering data collection with the students involved in the study directed the data collection. The research assistant visited PE classes, explained the study and questionnaires to the students, and supervised/answered students questions until all partici- pants completed the questionnaires. The students completed the questionnaires during one class period of PE. Data Analysis Data were initially screened for outliers and distribution characteristics. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to evaluate internal consistency of all subscales. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to examine the construct valid- ity of the motivational climate subscales of the PALS. Descrip- tive statistics and simple correlations were then calculated. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 105  A. C. GARN ET AL. Finally, structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation procedures was used to investigate the fit of the data to the proposed models and simultaneously examine relationships among variables. Specifically, two separate mod- els were tested. In model one, we investigated the direct rela- tionships between perceptions of the motivational climate and physical activity outcomes. In model two, perceived compe- tence in PE was added as an intermediary variable in the rela- tionship between perceptions of the motivational climate and physical activity outcomes. In the measurement model, partially aggregated indicators (i.e., parcels) were created for the per- ceived mastery climate and physical activity latent variables (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Parcels pro- vide advantages to obtaining a parsimonious model by stabiliz- ing parameter estimates and increasing the reliability of indica- tors (Coffman & MacCallum, 2005). Specifically, a random assignment technique was used to create three parceled indica- tors for perceptions of the mastery climate (six items) and self- reported physical activity (eight items) latent variables. Evaluation criteria outlined by Hu and Bentler (1999) and Kline (2006) were used to determine how well the proposed measurement models fit the data in the CFA and SEM. The specific indexes/cutoffs to determine the fit of the measurement model to the data were: χ²/df ratio (<3), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; <.06 = good fit; <.08 = acceptable); Comparative Fit Index (CFI; >.95 = good fit; >.90 = accept- able); and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; >.95; >.90 = accept- able). A minimum standardized factor loading of >.40 for indi- cators was also used to evaluate the measurement model (Kline, 2006). A preliminary Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to examine the possibility of between-school variance for the study variables. School was used as the independent variable while all six study variables were entered as dependent variables. Results from the MANOVA were not significant (Wilks’ λ = .91; p = .22) suggesting between-school variance was not significantly different among schools. Results Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results from the CFA that examined the construct validity of the trichotomous perceived motivational climate model are presented in Figure 1. Findings yielded a good fit of the data to the proposed trichotomous model (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2006). Standardized factor loadings ranged from .53 - .89 sug- gesting that each indicator loaded on its intended latent variable. Fit indices also highlighted a good fit of the data to the model. Specifically, the χ²/df ratio was under two, both the CFI and TLI were equal to or above .95, and the RMSEA was below six. Descriptive Statistics Descriptive statistics, internal consistency estimates, and simple correlations are presented in Table 1. The internal con- sistency estimates ranged from .75 - .89. All variables except self-reported physical activity had mean scores above the mid-point of its respective scale. The mean scores ranged from a high of 4.02 (i.e., perceptions of a mastery climate) to a low of 2.60 (i.e., self-reported physical activity). Therefore, on average, Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis results of the perceived mo- tivation climate trichotomous model. Mastery = percep- tions of a mastery climate; PerfApp = perceptions of a performance approach motivational climate; PerfAvoid = perceptions of a performance avoidance motivational cli- mate. Fit indices suggest good fit of the proposed model: χ²/df ratio = 134.15/74 = 1.81; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .054 [.039 - .069]. Table 1. Descriptive statistics, cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and simple correla- tions of all variables. Variable M (SD) α 1 2 3 4 5 6 1.Mastery 4.02 (.63) .83 - 2.PerfApp 2.65 (1.14).89 .14* - 3.PerfAvoid 2.64 (0.98).86 .12* .63** - 4.Perceived Comp 3.49 (0.83).85 .25** .15* .08 - 5.Future Intentions 3.61 (0.80).75 .35** .12 .05 .47** - 6.Physical Activity 2.60 (0.67).75 .15* .13* .05 .47** .41** - Note: M = mean; SD = standard deviation; α = Cronbach alpha; Mastery = per- ceived mastery motivational climate; PerfApp = perceived performance approach motivational climate; PerfAvoid = perceived performance avoidance climate Perceived Comp = perceived competence in PE; Future Intentions = future inten- tions for physical activity. *p < .05; **p < .01. the girls reported being physically active approximately 2 - 3 times per week. The strongest correlations were between per- ceptions of a performance approach motivation climate and perceptions of a performance avoidance motivation climate (r = .63), perceived competence in PE and physical activity (r Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 106  A. C. GARN ET AL. = .47) and perceived competence in PE and physical activity intentions (r = .47). Structural Equation Modeling The main purpose of the current study was to investigate re- lationships among perceived motivational climates in PE, per- ceived competence in PE, and physical activity outcomes for underserved adolescent girls. We tested two separate SEM models in order to accomplish this task. In the first model, the direct relationships between the girls’ perceptions of the moti- vational climates and physical activity outcomes were exam- ined. Results for this direct model are presented in Figure 2. Examination of the measurement model revealed a good fit of the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2006). Standardized factor loadings ranged from .57 - .89, the χ²/df ratio was less than two. Furthermore, CFI and TLI estimates were close to .95 and the RMSEA was just below .06. Findings from the structural model revealed that perceptions of a mastery climate were related to both future intentions for physical activity (β = .44, p < .01) and self-reported physical activity (β = .17, p < .05). Percep- tions of a performance approach climate were related to physi- cal activity (β = .21, p < .05) while perceptions of a perform- ance avoidance climate were negatively associated with self- reported physical activity. There was no significant relationship between perceptions of performance approach or performance avoidance motivational climates and future intentions for physical activity. Perceptions of the three different motivitional climates accounted for 21% of the variance in future intentions for physical activity and 5% of the variance in self-reported physical activity. In the second model, perceived competence in PE was added to the model (see Figure 3). Results again yielded support for the measurement model. Standardized factor loadings ranged from .60 - .89 and the χ²/df was well below two. The CFI and .44** .17* .14 .21* -.12 -.18* Figure 2. Standarized path coefficients from structural equation model of direct relationships among perceptions of the motivational cliamte in physical education, self-re- ported phsyical activity, and future intentions of physical activity. Fit indices suggest good fit of the proposed model: χ²/df ratio = 131.50/68 = 1.93; CFI = .96; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .058 [.043 - .073]. The R² values for future intentions for physical activity = .21; R² values for self-reported physical activity = .05. .29** .27** .55** .52** .36** -.20* Figure 3. Standarized path coefficients from structural equation model of relationships among perceptions of the motivational cliamte in physical education, percieved competence in phsyical education, self-reported phsyical activity, and future intentions of physical activity. Fit indices suggest good fit of the proposed model: χ²/df ratio = 179.66/126 = 1.43; CFI = .98; TLI = .97; RMSEA = .039 [.025 - .052]. The R² values for perceived competence in physical education = .15; R² values for future intentions for physical activity = .44; R² values for self-reported physical activity = .31. TLI estimates were well above .95 and the RMSEA was .039. Examination of the pattern of relationships revealed that per- ceptions of a mastery climate had positive direct relationships with perceived competence (β = .27, p < .01) and future inten- tions for physical activity (β = .29, p < .01). The standardized indirect effect between perceptions of a mastery climate and self-reported physical activity was β = .15. Perceptions of a performance approach climate had a direct relationship with perceived competence in PE (β = .36, p < .01) and indirect relationships with future intentions (β = .18) and physical activ- ity (β = .20). Perceptions of a performance avoidance climate had a negative relationship with perceived competence in PE (β = −.20, p < .01) and limited indirect relationships with future intentions (β = −.11) and self-reported physical activity (β = −.10). Perceived competence in PE had robust relation- ships with both future intentions (β = .55, p < .01) and physical ac- tivity (β= .52, p < .01). In this model, 15% of the variance was accounted for in perceived competence in PE, 44% of the vari- ance in future intentions, and 31% of the variance in self-re- ported physical activity. Discussion The findings of this study provide both theoretical and prac- tical insights about relationships between urban PE and physi- cal activity outcomes in underserved adolescent girls. One con- tribution of this study was the testing of a trichotomous model of the perceived motivational climate in PE. In the physical domain, use of the approach/avoidance framework has focused on achievement goal orientations. As Duda and Ntoumanis (2003) note: Insight into motivational processes in PE will always be re- stricted if we only examine students’ goal orientations. There is Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 107  A. C. GARN ET AL. a dynamic system going on here that we need to come to grips with in our research designs. More insight is necessary regard- ing how PE teachers convey the “messages” about achieve- ment goal focus to students and how, when, and in which cases students start to internalize these messages and think, feel, and act accordingly (p. 431). Midgley and colleagues (2000) created an instrument to dis- tinguish between perceptions of performance and performance avoidance classroom structures, but to date its application in PE has been missing. Results from the CFA supported the con- struct validity of the trichotomous model. Furthermore, clear divergences in the pattern of relationships between perceptions of a performance climate and perceptions of a performance avoidance climate and outcome variables were present. Our results supported Elliot’s (1999) theorizing that more often than not, maladaptive outcomes are associated with perceptions of performance avoidance structures. The high mean score for perceptions of a mastery climate was a pleasant surprise. It is possible that the teachers’ imple- mentation of the EPEC curriculum contributed to this finding, although we do not have direct evidence. The teachers of this study were experienced and had sustained professional devel- opment experiences with EPEC. The EPEC curriculum empha- sizes personal development, lifelong sports, and aligns to NASPE (2004) content standards. The EPEC focus on the indi- vidual appears to match key ingredients of a mastery climate (e.g., focus on improvement and process of learning). On the other hand, the low amount of physical activity reported by these underserved girls was in line with previous research find- ings (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2000). The participants of this study were clearly not meeting recommended guidelines for physical activity (USDHHS, 2008). Other researchers have also targeted underserved girls because they are at-risk for physical inactivity, obesity, and morbidity (Robinson et al., 2008; Wilson et al., 2008). Although this was not an intervention-based study like Robinson et al. (2008) or Wilson et al. (2008), both sets of re- searchers reported the severe need for more physical activity research targeting underserved adolescent girls. Relationship s am ong Variables Examination of the relationships among the perceived moti- vational climates in PE, perceived competence in PE, and physical activity outcomes provides some interesting topics of discussion. First, comparison of the two SEM models high- lights the importance of perceived competence in PE, when examining the relationship between perceptions of motivational climates in PE and physical activity outcomes. For example, only a minimal amount of the physical activity variance (5%) was explained by the direct relationships between the perceived motivational climate and physical activity, mirroring past re- search (Parish & Treasure, 2003). The fact that 26% more variance was explained in self-reported physical activity when perceived competence in PE was included suggests that it is a key intermediary factor when considering how perceptions of the motivational climates in PE are related to physical activity in underserved adolescent girls. Interestingly, in the direct model perceptions of a perform- ance climate and perceptions of a mastery climate had similar positive relationships with self-reported physical activity. The major difference between the two types of approach-oriented perceptions of the motivational climate was the relationship with intentions for future physical activity. Interpretation of the standardized beta coefficient revealed that perceptions of a mastery climate increased the likelihood for self-reported physical activity by almost half of a standard deviation. Percep- tions of a mastery climate still appeared to be more advanta- geous than perceptions of a performance climate in relation to the physical activity outcomes: however; physical educators who are able to create approach-oriented motivational climates with goal structures that support both personal and normative success would likely also see an increase in underserved ado- lescent future intentions for physical activity and to a limited degree, self-reported physical activity. More investigations are needed to determine the optimal balance between mastery and performance class structures to promote physical activity out- comes in PE. The negative relationship between perceptions of a perform- ance avoidance motivational climate and self-reported physical activity in the direct model was aligned to the assumptions of approach/avoidance achievement goal theory (Elliot, 1999; Midgley, 2002). Avoidance mentalities have a long association with negative achievement outcomes (McClelland, 1973). PE climates that are viewed as performance avoidance contexts where explicit or implicit structures punish students for show- ing low ability or making mistakes appears to be detrimental to underserved girls’ physical activity. Specifically, with this type of perception PE may actually represent another barrier to un- derserved girls’ physical activity. As hypothesized, results from the indirect model provided a more comprehensive picture of the associations between the perceived motivational climate in PE and physical activity out- comes for these underserved adolescent girls. All three percep- tions of the motivational climate in PE had relationships with the girls’ perceived competence in PE. Perceptions of a per- formance climate and mastery climate were positively related to perceived competence. While it was expected for an “improve- ing outlook” (i.e., mastery) of goals structures in PE to be asso- ciated with increased perceived competence (Roberts, 2001; Wallhead & Ntoumanis, 2004), it was somewhat surprising that a “proving outlook” (i.e., performance) was, too. It is possible that perceptions of a performance climate in PE may provide opportunities for underserved girls to obtain social recognition and positive feedback for their physical competence. A “protec- tive outlook” was negatively related to perceived competence in PE. There appears to be a fine line between perceptions of a performance climate and performance avoidance climate (r = .63) that results in quite distinct outcomes. It should be noted that our results represent a “snapshot” of the perceived motivational climate in PE. It is unclear how promoting performance climates or performance avoidance climates over time would be related to perceived competence in PE and physical activity in underserved adolescent girls. It is possible that perceived competence could and likely would decrease for girls who consistently perceive failure in meeting normative goal structures (Roberts, 2001). Similarly, the per- ceptions of a performance climate—perceived competence rela- tionship in PE could potentially erode if minimal skill devel- opment or learning was taking place for low skilled students. Having trained and experienced teachers implement the ac- countability-based EPEC curriculum may help explain the posi- tive link between perceptions of a performance climate and perceived competence in this study. Perceptions of a mastery climate had both direct and indirect Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 108  A. C. GARN ET AL. relationships with future intentions for physical activity across the two models. From an achievement goal theory perceptive, this may be due to the mastery climate focus on the process and personal improvement (Solmon, 1996). In other words, when PE goal structures stress the importance of the process over the outcome, there appears to be a greater association with making plans to be active in the future. Making immediate plans to be physically active could potentially help many underserved ado- lescent girls seek out opportunities that minimize physical ac- tivity barriers (Gomez et al., 2004). High school physical edu- cators teaching in the urban context should be especially aware of the benefits that implementing motivational climate per- ceived as mastery-oriented can have for adolescent girls be- cause the social environment in PE often places them at a dis- advantage for obtaining physical activity outcomes (Cheypa- tor-Thompson, You, & Hardin, 2000; Domangue & Solmon, 2010). The girls’ perceived competence in PE had robust effects on their intentions to be physically active and physical activity behavior. Perceptions of a mastery climate may be especially effective at providing girls with more equitable physical activ- ity opportunities in PE that produce feelings of physical com- petence in that domain. In fact, the development of achieve- ment goal theory was closely tied to understanding how to cre- ate more equitable experiences for students and athletes (Nicholls, 1989; Roberts, 2001). Based on our findings and theorizing from Ennis (2011), investigating the motivational climate in conjunction with the domain specific characteristics of the PE context (e.g., instruction, curriculum) may provide a clearer picture on how to increase the perceived competence of a wider variety of students in PE including underserved ado- lescent girls. In conclusion, this study is not without limitations. The cross-sectional design and reliance on self-report data are clear limitations. Future research would benefit from including sys- tematic observations of the PE learning environment, prospec- tive and longitudinal research designs, as well as more objec- tive measures of physical activity (e.g., accelerometers). How- ever, results from this study do provide meaningful information about how school-based settings can positively contribute to the physical activity patterns and future intentions of underserved adolescent girls. Support for the achievement goal theoretical model tested in this study highlights practical strategies for urban PE teachers to increase important cognitive mediators of physical activity. Future researchers should continue to inves- tigate theoretical models that provide structure to expanding the current knowledge-base about enhancing the levels of physical activity for underserved adolescent girls. REFERENCES Ames, C. (1992). Achievement goals, motivational climate, and moti- vational processes. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Motivation in sport and exercise (pp. 161-176). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychology research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 51, 1173-1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 Biddle, S. J. H., Soos, I., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (1999). Predicting physical activity intentions using goal perspectives and self- determination theory approaches. European Psychologis t , 4, 83-89. Braithwaite, R., Spray, C. M., & Warburton, V. E. (2011). Motivational climate interventions in physical education: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport an d Exercise, 12, 628-638. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.06.005 Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The Guilford Press. Butcher, K., Sallis, J. F., Mayer, J. A., & Woodruff, S. I. (2008). Cor- relates of physical activity guideline compliance for adolescents in 100 US cities. Journal of Adolescent H ealth, 42, 360-368. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.025 Cheypator-Thompson, J. R., You, J., & Hardin, B. (2000). Issues and perspectives on gender in physical education. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journa l , 9, 99-114. Coffman, D. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Be- havioral Research, 40, 235-259. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr4002_4 Domangue, E. A., & Solmon, M. A. (2010). Motivational responses to fitness testing by award status and gender. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 81, 310-318. Duda, J. L. (2005). Motivation in sport: The relevance of competence and achievement goals. In A. J. Elliot, & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Hand- book of competence and motivation. New York: Guilford Press. Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2003). Correlates of achievement goal orientations in physical education. International Journal of Educa- tional Research, 39, 415-436. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2004.06.007 Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achieve- ment goals. Edu cational P sychologist, 34, 169-189. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3403_3 Ennis, C. D. (2011). Physical education curriculum priorities: Evidence for education and skillfulness. Quest, 63, 5-18. doi:10.1080/00336297.2011.10483659 Fairclough, S. J., & Stratton, G. (2005). Physical activity levels in mid- dle school and high school physical education: A review. Pediatric Exercise Science, 17, 217-236. Gomez, J. E., Johnson, B. A., Selva, M., & Sallis, J. F. (2004). Violent crime and outdoor physical activity among inner city youth. Preven- tative Medicine, 39, 876-881. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.019 Gordon-Larsen, P., McMurray, R. G., & Popkin, B. M. (2000). Deter- minants of adolescent physical activity and inactivity patterns. Pedi- atric Exercise Science, 105, e83. doi:10.1542/peds.105.6.e83 Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in co- variance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alterna- tives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 Kavussanu, M., & Roberts, G. C. (1996). Motivation in physical activ- ity contexts: The relationship of perceived motivational climate to in- trinsic motivation and self-efficacy. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18, 264-280. Kirk, D. & Tinning, R. (2005). Introduction: Physical education, cur- riculum, and culture. In D. Kirk & R. Tinning (Ed.), Physical educa- tion, curriculum, and culture: Critical issues in the contemporary crisis (pp. 1-18). Bristol, PA: Taylor & Francis. Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. Kowalski, K. C., Crocker, P. R. E., & Kowalski, R. M. (1997). Con- vergent validity of the physical activity questionnaire for adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science, 9, 342-352. Larsson, H., Fagrell, B., & Redelius, K. (2009.) Queering physical education. Between benevolence towards girls and a tribute to mas- culinity. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 14, 1-17. doi:10.1080/17408980701345832 Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structu ra l Equation Modeling, 9, 151-173. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1 Martin, J., & McCaughtry, N. (2008). Using social cognitive theory to predict physical activity in inner-city African American school chil- dren. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30, 378-391. Martin, J., McCaughtry, N., Flory, S., Murphy, A., & Wisdom, K. (2011). Using social cognitive theory to predict physical activity and fitness in underserved middle school children. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82 , 247-255. McCaughtry, N. (2004). Learning to read gender relations in schooling: Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 109  A. C. GARN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 110 Implications of personal history and teaching context on identifying disempowerment for girls. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 75, 400-412. doi:10.1080/02701367.2004.10609173 McClelland, D. C. (1973). Sounds of n achievement. In D. McClelland & R. Steele (Eds.), Human Motivation: A book of readings (pp. 252-276). Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press. McKenzie, T. L., Marshall, S. J., Sallis, J. F., & Conway, T. L. (2000). Student activity levels, lesson context, and teacher behavior during middle school physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71, 249-259. doi:10.1080/02701367.2000.10608905 Michigan Fitness Foundation (2005). Michigan’s exemplary physical education curriculum project: User’s guide. Lansing, MI: Michigan Fitness Foundation. Midgley, C. (2002). Goals, goals structures, and patterns of adaptive living. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hruda, L. Z., Anderman, E., Anderman, L. H., Freeman, K. E., Urdan, T. et al. (2000). Manual for the patterns for adaptive learning scales. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. National Association for Sport and Physical Education (2004). Moving into the future. National standards for physical education (2nd ed.). Reston, VI: NASPE Publications. Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press. Ntoumanis, N. (2001). A self-determination approach to the under- standing of motivation in physical education. The British Journal of Educational Psycholo g y , 71, 225-242. doi:10.1348/000709901158497 Ntoumanis, N., & Biddle, S. J. H. (1999). A review of motivational climate in physical activity. Journal of S p o r t Sciences, 17, 643-665. doi:10.1080/026404199365678 Parish, L. E. & Treasure, D. C. (2003). Physical activity and situational motivation in physical education: Influence of the motivational cli- mate and perceived ability. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74, 173-182. doi:10.1080/02701367.2003.10609079 Rhodes, R. E., Macdonald, H. M., & McKay, H. A. (2006). Predicting physical activity intentions and behavior among children in a longi- tudinal sample. Social Science and Medi cine, 62, 3146-3156. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.051 Roberts, G. C. (2001). Understanding the dynamics of motivation in physical activity: The influence of achievement goals on the motiva- tional processes. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Advances in motivation in sport and exercise (pp. 1-50). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Robinson, T. N., Kraemer, H., Matheson, D., Obarzanek, E., Wilson, D., Haskell, W., Killen, J. et al. (2008). Stanford GEMS phase 2 obesity prevention trial for low-income African-American girls: Design and sample baseline characteristics. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 29, 56-69. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2007.04.007 Sabiston, C. M. & Crocker, P. R. (2008). Exploring a model of self-perceptions and social influences in the prediction of adolescent leisure-time physical activity. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30, 3-22. Silverman, S. (2005). Thinking long term: Physical education’s role in movement and mobility. Quest, 57, 138-147. doi:10.1080/00336297.2005.10491847 Solmon, M. A. (1996). Influences of motivational climate on students behaviors and perceptions in a physical education setting. Journal of Educational Psycholo g y, 88, 731-738. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.88.4.731 Sproule, J., Wang, C. K. J., Morgan, K., McNeill, M., & McMorris, T. (2007). Effects of motivational climate in Singaporean physical edu- cation lessons on intrinsic motivation and physical activity intention. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1037-1049. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.017 Swanson, C. B. (2008). Crisis in cities: A special analytic report on high school graduation. http://www.edweek.org/media/citiesincrisis040108.pdf United States Department of Health and Human Services (2008) Physical activity guidelines for Americans: Be active, healthy, and happy. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services. Wallhead, T. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2004). Effects of a sport education intervention on students’ motivational responses in physical educa- tion. Journal of Teaching i n Physical Education, 23, 4-18. Wang, J. C. K., Liu, W., Chatzisarantis, N., & Lim, C. (2010). Influ- ence of perceived motivational climate on achievement goals in physical education: A structural equation mixture modeling analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 32, 324-338. Wilson, D. K., Kitzman-Ulrich, H., Williams, J., Saunders, R., Griffin, S., Pate, R., Sisson, S. et al. (2008). An overview of “The Active by Choice” (ACT) trial for increasing physical activity. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 29, 21-31. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2007.07.001 Wright, P. W., Li, W., & Ding, S. (2007). Relations of perceived moti- vational climate and feelings of belonging in physical education in urban schools. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 105, 386-390. Xiang, P., & Lee, A. (1998). The development of self-perceptions of ability and achievement goals and their relations in physical educa- tion. Research Q uarterly for Exercise and Sport, 69, 231-241. doi:10.1080/02701367.1998.10607690

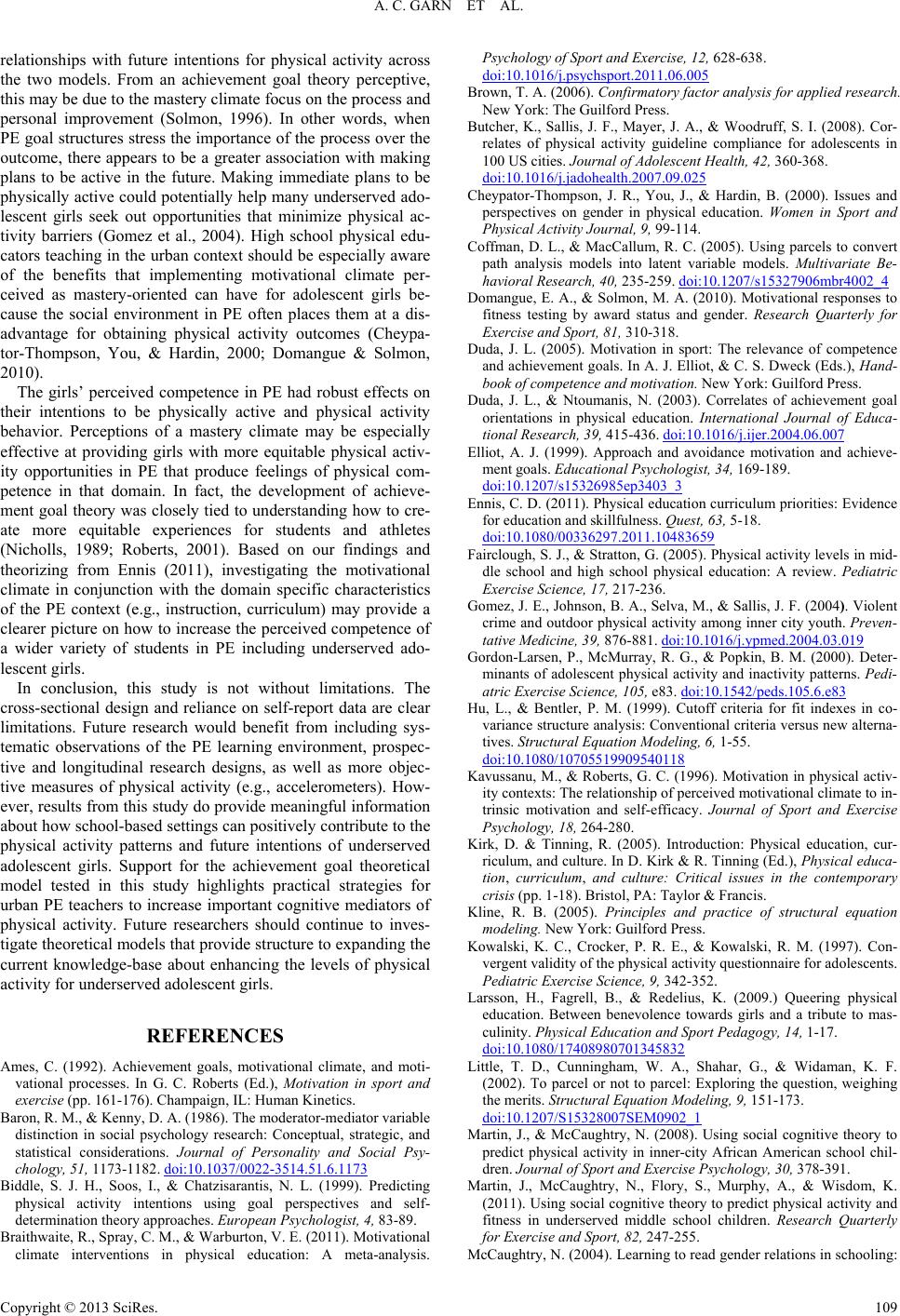

|