Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

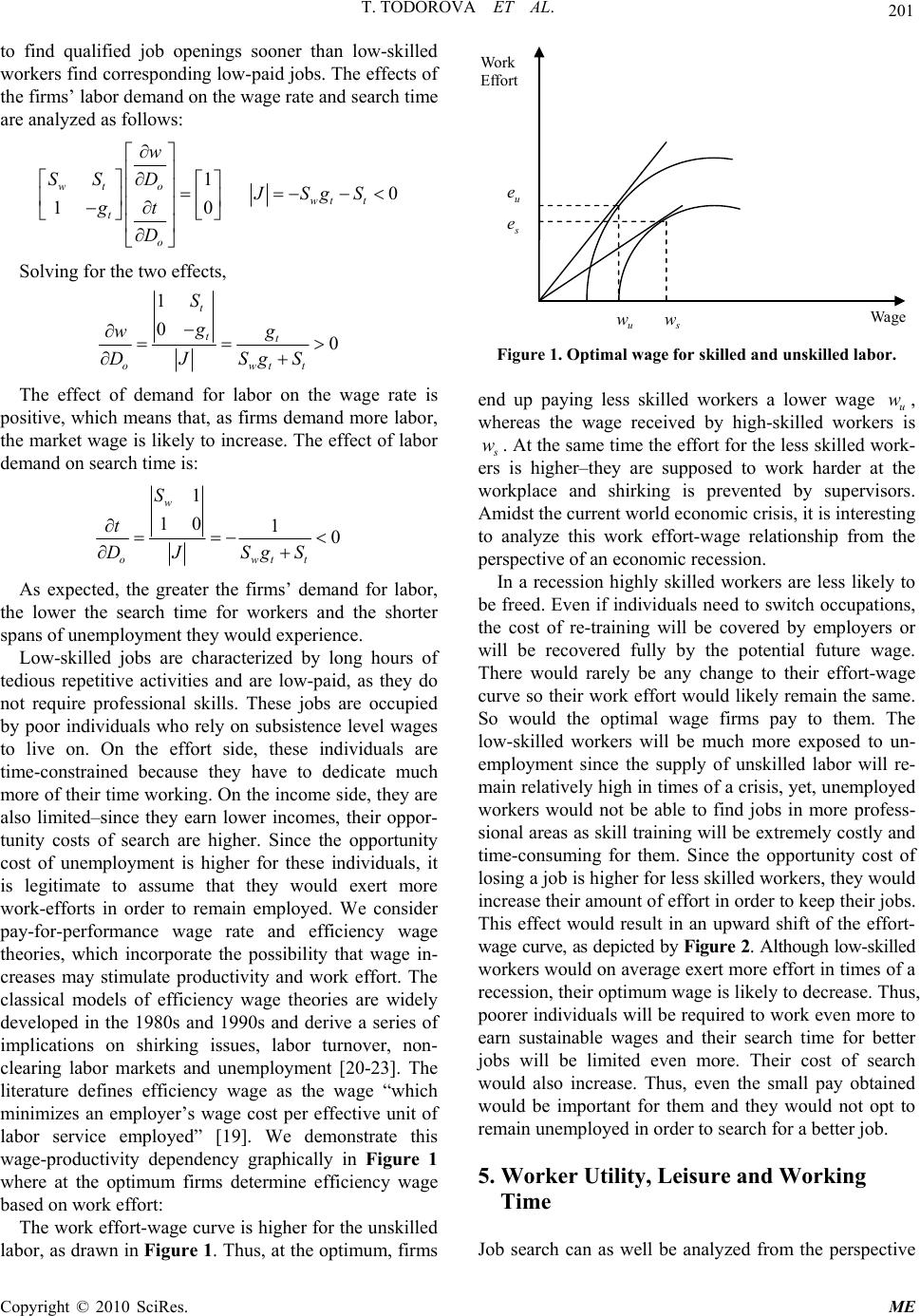

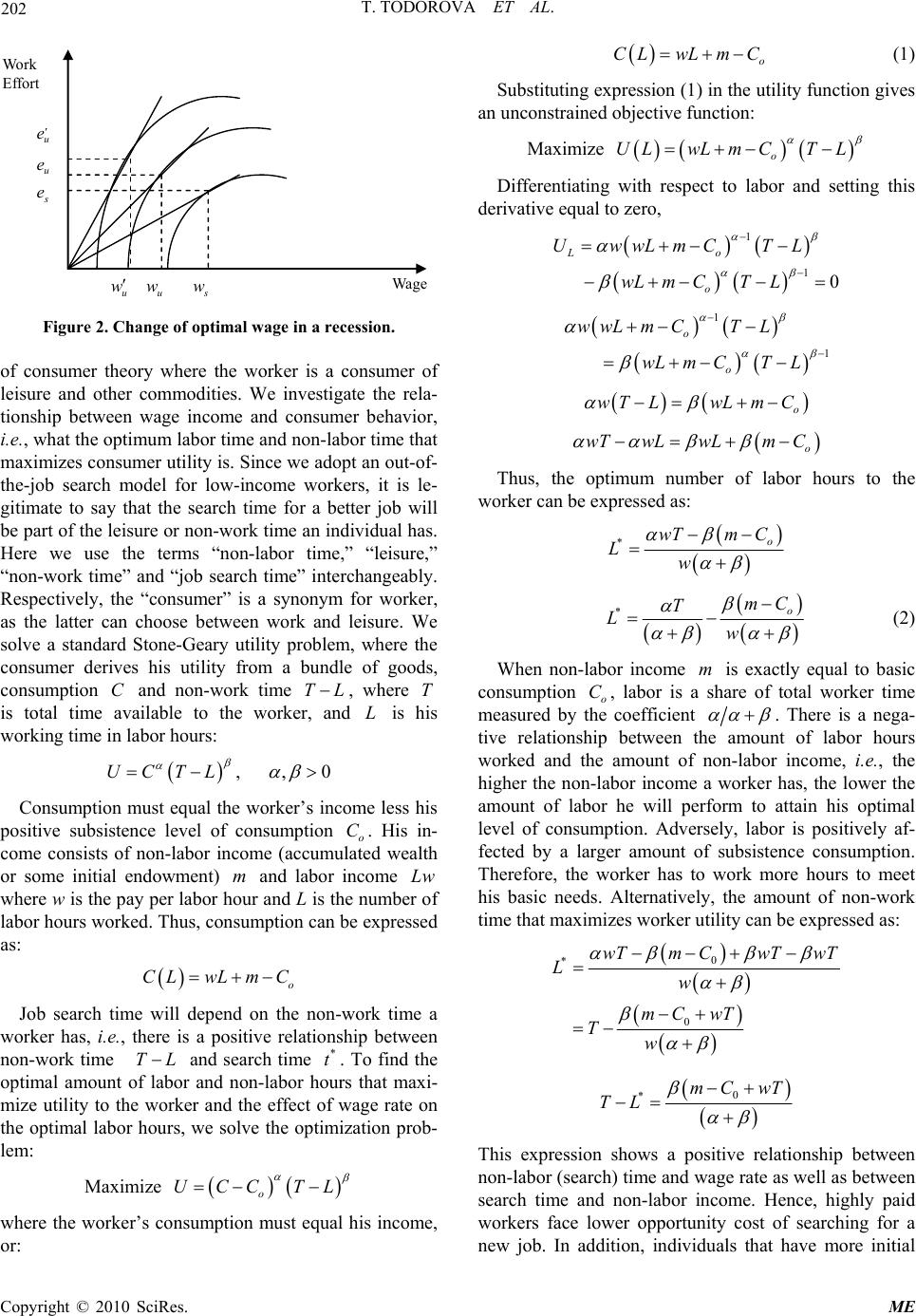

Modern Economy, 2010, 1, 195-205 doi:10.4236/me.2010.13022 Published Online November 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME Optimal Time and Opportunity Cost of Job Search in Low-Income Groups: An Out-of-the-Job Search Model Tamara Todorova, Veselina Dzharova American University in Bulgaria, Department of Economic s , Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria E-mail: ttodorova@aubg.bg, vdzharova@ g mail.com Received September 3, 2010; revised October 4, 2010; accepted October 8, 2010 Abstract Our paper studies the causes of poverty from the perspective of job search. We show that poor people remain poor because they have less time and initial endowment to search for a better job. Initial endowment is key to successful job search, as one can afford not to work and search longer for a better job. Having an initial en- dowment, a worker is able to educate or re-qualify himself. Working long hours and obtaining low pay, poor people have little time to look for a better job. Low-paid, low-skilled jobs rarely allow on-the-job search like high-paid positions where with the help of contacts and a lot of idle time professionals seek better jobs. Quit- ting in order to find a better job increases the opportunity cost of search for poorer people. Since they do not have any accumulated income, they can only live off their salary. With less income and time, poorer people are less likely to get educated since education requires both wealth and free time. But being less educated, they are likely to remain poor as education is a promise for success in contemporary society. Thus, they re- main in the vicious circle of poverty. In order to prove this hypothesis we investigate optimal search time for a better job as dependent on factors such as wage rate, individual’s income, education, and skills. Keywords: Job Search, Optimal Search Time, Initial Endowment, Employment, Educational Level, Povert y, Low-Skilled Jobs 1. Introduction Poor, uneducated people are often said to remain in the vicious circle of poverty and it is a trap for many in the world economy on the eve of a new century. There are various ways in which poverty plagues workers around the globe–in our paper we study just two mechanisms. More specifically, those are the lack of time to search for a better job, while overwhelmed by a low-paid one, and the lack of initial endowment or wealth. Our paper has, to some extent, been inspired by Barbara Ehrenreich’s book “Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in Amer- ica” [1], although we have previously been familiarized with Günter Wallraff’s “Ganz Unten” [2]. Ehrenreich’s idea is that poor people create much greater value than what they are paid for, thus, letting others live off their generosity, opposite to the common belief. The famous journalist takes low-paid jobs in order to experience the hardships of poverty. She finds that ordinary low-wage workers are paid much less than they deserve and than the subsistence level, barely provid ing for themselves, let alone a family. Because one job is not enough, a worker has to take at least two in order to live indoors. Low- prestige, low-level occupations at th e same time require a lot of mental and physical efforts. Ehrenreich writes: “When someone works for less pay than she can live on ... she has made a great sacrifice for you ... The ‘working poor’ ... ar e in fact the major philanthropists of our society. They neglect their own children so that the children of others will be cared for; they live in substandard housing so that other homes will be shiny and perfect; they endure privation so that inflation will be low and stock prices high. To be a member of the working poor is to be an anonymous donor, a nameless benefactor, t o everyone.” [1, p. 221] Intrigued by Ehrenreich’s description of the poor lay- ers of the American labor force with their struggle for survival and better life, we study how low pay and hard labor prevent workers from obtaining wealth and social status. More specifically, we show that, having less search time and initial endowment, poor people remain trapped in a low-level, low-paid po sition with no chance of escaping the whirlpool of poverty. Working long hours for low pay, poor people have little time to look  196 T. TODOROVA ET AL. for a better job. Low-paid, low-skilled jobs do not allow on-the-job search whereas with the help of professional contacts and availab le time people in high -paid positions seek better jobs. In their search for a better job peop le in low-paid, less prestigious jobs have to quit but quitting increases the opportunity cost of search for them. Since they do not have any accumulated income, they can only live on their salary. With less income and time, poor people remain less educated and poor. We study optimal search time for a better job as dependent on factors such as wage rate, individual’s income, education, and skills. More specifically, setting to be optimal search time, we express the comparative static effect of the number of years to search the minimum wage level the educational level o, etc., on the optimal search time. Some of the main findings of our paper can be summa- rized, as follows: * t ,ye, o w 1) The higher the initial minimum wage, the smaller the search time would be and the greater the prospects of the individual to find a better-paid job. The longer the time to be at an ideal, better-paid job, the longer one would search for this job. The greater the total number of years to work, the longer the job search time. 2) The higher the initial income of an individual, the greater his prospects of obtaining a better paid job are and the greater the free time of the job searcher is. Thus, rich individuals have more time to search for a better job and are more likely to find it. 3) As common sense dictates, a higher educational level promises a higher wage. More educated people need less time to search for a better job and are less likely to experience long periods of unemployment. 4) As expected, the optimal number of labor hours depends negatively on the wage rate and non-labor in- come and positively on the price of free time. Thus, poor agents, whose labor income should satisfy the subsis- tence level of consumption, will face higher price of free time and would work more labor hours to attain their optimum utility level of co nsumption. There is extensive economic literature dedicated to job search. Search theory generally is a branch of microeco- nomics that studies optimal decision-making of rational individuals with regard to potential opportunities of dif- ferent quality, accounting for both the external and in- ternal costs of search. External costs include those of acquiring information and the opportunity cost of search time. External costs are exogenously determined and the individual may choose only whether to incur them or not. Internal costs include the mental effort to undertake the search, sort the incoming information, and integrate it with what the consumer already knows. Internal costs are determined by the consumer's ability to undertake the search, which depends on intelligence, prior knowledge, education and training [3]. In labor economics, search theory is related to job- seeking models where a worker searches for a job that pays a high wage or offers desirable benefits, safe and desirable working conditions. The search process is re- lated to the optimization proble m of how much time and effort to spend searching, and which offers to accept or reject. In the 1960s Stigler [4,5] and Alchian and Allen [6] were among the first economists to study the problem of search for employment in an economy where informa- tion is costly and uncertainty prevails. McCall [7] put this economically important problem in a mathematical framework. His search model obtains an optimal search policy, where the worker knows the distribution of wages for his particular skills, the cost of search is a known constant, and the value of money is constant. Holding fixed job characteristics, the searcher makes a job search decision with respect to his reservation wage, i.e., the lowest wage he is willing to accept. Job offers arrive periodically and the searcher accepts or rejects them as they arise. The worker’s optimal strategy is simply to reject any wage offer lower than his reservation wage, and accept any wage offer higher than his reservation wage. The reservation wage may change over time if some of the conditions assumed are not met. For example, if the worker is risk averse, the reservation wage will decline over time if the worker gradu ally runs out of time and income while searching. The reservation wage will also differ for two jobs of different characteristics; that is, there will be compensating wage differentials between different types of jobs. McCall’s basic model serves as a basis for later works among which those of Mortensen [8], Burdett [9], Pis- sarides [10], Jovanovich [11], and Van den Berg [12]. These authors analyze important issues connected to job search and the behavior of unemployment [10], wage determination [9,11,13], job duration, job turnover [12], quit rates [9], and unemployment insurance and em- ployment protection [10]. These seminal economic mod- els have given birth to extensive research in the context of search theories, and the empirical studies serve to in- vestigate the stylized facts of the classical theory. Search theories have discussed optimal search time in the con- text of other issues–Kahn [14] estimates the relationship between search time and resulting wage and further the duration span of unemployment is investigated. Yoon [15] includes search time as endogenous factor deter- mining unemployment duration and pays attention spe- cifically to intensity of the search effort in determining search costs. Optimal search time is also discussed as the marginal benefit of not being employed or the value of unemployment benefits during the unemployment dura- tion [16]. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  T. TODOROVA ET AL. 197 Our purpose is to study an individual’s optimal strat- egy when searching for a job in light of the trade-off in- volved: the cost of remaining unemployed while search- ing versus the added value of the option to find a better job. We are specifically interested in partial search mod- els, where the focus is on the behavior of the unem- ployed individuals looking for better jobs rather than the firms’ behavior in the labor market. We develop a basic out-of-the job search model that focuses on how optimal time and opportunity cost differ among low-income and high-income individuals, ceteris paribus, that is, given they have the same initial tastes, talen ts, an d ability ren ts. Low-income searchers who have low or no accumulated wealth to devote to job-seeking cannot afford to remain unemployed for a long time and tend to lower their res- ervation wages below what co rresponds to their skills. In contrast, more wealthy seekers have more free time and disposable income to engage in search for a better job. Given their higher probability to find a better job, the value of their choice is likely to be high er. Income inequalities have further implications for job searchers. Human capital theories study the opportunity cost of purchased inputs in human capital production. The basic model formulated on optimal human capital investment is Becker’s model [17]. This model generates general description of how ability and family wealth in- teract to determine the distribution of lifetime earnings. The opportunity cost of human capital investment de- pends on family incomes because families should pay for the post-secondary schooling required to gain additional skills. In this sense, wealthy agents can finance their education on better terms and in general can invest more and boost future earnings. Becker defines this difference in financing opportunities as “unequal opportunity,” since poor agents face higher opportunity cost of funds even when they have the same personal abilities. Following Becker’s model, we assume that wealthy individuals are more educated since they face lower costs of financing and would invest more in developing their skills. As a result, they would have more specialized skills to per- form highly-skilled professional labor. Further, we in- vestigate how the opportunity cost of job search adds to the opportunity cost of human capital in defining wage differentials. Poor agents face higher opportunity cost of delay and tend to choose from a limited range of oppor- tunities, while rich individu als can afford to reject multi- ple job opportunities that do not correspond with their skills. Therefore, wealthy individuals find better jobs (including higher wage, more benefits, and safer working conditions) than their lower-income counterparts. The analysis can further be extended to include impli- cations for individual careers. Learning models in the theory of earnings distributions [11,18] state that without information about their relative talents for different types of jobs, workers cannot make choices that maximize earnings. Thus, workers gain from work experience in two ways: first, they are paid the current wage, and sec- ond, they receive information about their skills that can boost future earnings. Since low-income agents accept low-paid jobs which require low-skilled labor, these agents would tend to gain less valuable experience at the workplace. This would decrease the quality of their sort- ing process and ultimately would lower their lifetime earnings. On the other hand, high-income agents would be employed in highly-skilled positions and work ex- perience would improve their opportunities of finding even better jobs. We do not elaborate further on theories of learning, sortin g and matchin g but concentrate on how the different opportunity costs of search for different income groups lead to “unequal opportunity” for the low-income searchers versus the high-income searchers. The paper is organized as follows: part 1 is a discus- sion of the rationale for the paper and literature review. Part 2 represents a simple mathematical model of job search accounting for the number of years spent at a well-paid job. In Part 3 we modify this simple out-of-th e- job search model introducing the total nu mber of years to work. Part 4 gives a job market equilibrium model, in- troducing initial income and the level of education as determinants of job search time. In the last Part 5 of the paper we turn to consumer theory and investigate the relationship between optimal job search time and the maximum utility of a worker who derives his satisfactio n from two sources, consumption of goods and utilization of free, non-work time. The paper ends with conclusions. 2. A Simple Out-of-the-Job Search Model Our partial search model is focused on the behavior of the unemployed individuals looking for better jobs and not on firm behavior. We assume that a better job is one that pays a wage rate beyond the minimal one o be- cause in the labor market higher wage is associated with higher labor productivity, i.e., the job is of greater value both for the individual and for the firm. Another assump- tion is that searching individuals are unemployed during the search. This constraint is set by the fact that low- skilled and low-income individuals have labor-intensive, exploitative jobs, which leaves them minimal leisure time to devote to job search. Ours is an out-of-the-job search model that excludes the possibility of on-the-job search. Furthermore, the worker decides on an optimal search policy, given that he knows the distribution of wages for his particular skills. We also assume constant value of money, i.e., inflationary effects and time value of money are ignored for the sake of simplicity. This w Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  198 T. TODOROVA ET AL. assumption would not change the major implications of the mathematical results. The worker’s total gain from the job search can be expressed as: o wtw y where the worker is expected to work number of years at the well-paid job. The worker spends time searching for a well-paid job. The wage he would receive increases with search time, hence, . At the same time, the job search process is less productive with time and has diminishing returns, i.e., y ()wt t 0 () 0 ()wt wt . Without search the worker would receive a lowest pay to the amount of minimum wage o but with search there is a differential . Thus, the net benefit from search to the unemployed individual will be of the form: w () o wt w oo twtwyw t where from the total gain from search for a well-paid job we subtract the cost of searching o. This is what the worker sacrifices by not working for minimum wage during the search period. Maximizing net gain by the first-order condition, wt 0 o twtyw o wty w Using the second-order condition, 0twty proves a maximum for the net gain from search. The result of the optimization is that the worker will con tinue his job search until the marginal gain of the search equa ls his current wage o which represents his marginal cost of search. To find the effect of minimum wage on opti- mal search time we write the implicit fu nction and apply the implicit-function rule: w ,, 0 o Ftwytwtyw o By the implicit-func tion rule, *10 o w ot F t wFwty There is a negative relationship between and o, that is, the higher the initial minimum wage, the smaller the search time would be. In the context of unsk illed and skilled, qualified labor the higher initial payment is con- nected with qualified labor. Thus, the result shows that highly skilled workers are likely to find better jobs sooner than those that hold less qualified jobs and re- ceive low pay. Since firm demand for qualified labor is generally higher, these are the two effects of the higher demand–on the one hand, initial pay is higher and, on the other, it takes less time for professional labor to search for a job. This result adds up to the theory of wage dif- ferentials by which a major factor that contributes to wage differentials is the fact that the labor market con- sists of heterogeneous workers and firms. On the supply side of the market the move from low-paid jobs to high-paid ones depends on various factors such as skill differentials, differentials resulting from efficiency wage payments, as well as non-wage job differentials [19]. We find one more cause for wage differentials–the unequal opportunities for job search faced by skilled and un- skilled workers. Given the cost of information and job search, some labor market segments are privileged in the process of finding better jobs, all other things equal, simply because they can afford the cost of search and have the time for it. For the effect of the number of years to work on the optimal search time we obtain: * t w y* t *0 y y t Fwt t yFwt The greater the number of years to be at an ideal, bet- ter-paid job, the longer one would search for this job. 3. A Modified Job Search Model We then modify the model by specifying to be the total number of years the worker is expected to work throughout his lifetime. Hence, the number of years that he is expected to work at his better-paid job is y yt . We again assume that the worker is not employed while searching for an ideal job that pays and there are positive but diminishing returns to job search, i.e., ()wt ()wt 0 , and () 0wt . Without search the worker would receive a lowest pay to the amount of . The net gain of search is: o w o twtyt wt We find the optimal search time by maximizing the obtained f unction: 0twtytw o tw 0 o wty wtt wtw *oo wty wtww ty wt wt wt By the second-order condition the net gain of job search is maximized: 20 twtytwtwt wt ytwt We obtain that the optimal time to search for a job is a discretionary part of the total working-age years. From analyzing this optimum we see that the faster the * t Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  T. TODOROVA ET AL. 199 wage grows with search time, the long er the search goes. Thus when is infinitely large and the worker has the chance to infinitely increase h is income by searching more, he will continue searching throughout his entire life, or . However, if search time has little effect on the wage level, i.e., tends to zero, the worker’s optimal search time would also tend to zero and the worker would not be likely to search at all. To find the effect of minimum wage on optimal search time we use the implicit-function rule where the implic it function is: ()wt y * t()wt 0F tytwtw ,,wy o tw o t and by the implicit-function rule, *10 2 o w ot t wtytwt F wF * t This relationship again shows that the higher th e initial minimum wage, the shorter the search would be. Thus, again the segment of low-skilled workers will incur higher job search costs, as they will need more time for job search. Their opportunities for a better-paid job de- crease. For jobs that have higher initial payment o search time is smaller. The more slowly the ideal wage grows with search, that is, the smaller w ()wt is, the greater the effect of the initial wage is. For the effect of the total number of years to work on optimal search time we again obtain a positive value: y *0 2 y t F yF wt t wtytwt Our simple job search model shows that the greater the total number of years to work, the longer the job search time. Thus, younger individuals will have more incen- tives to search than elderly people, as simple logic dic- tates. 4. A Job Market Equilibrium Model To study the effect of initial endowment and education on wage rate we formulate a job market equilibrium model that accounts both for demand and supply on the labor market. We assume that the market is in equilib- rium, i.e., worker supply of labor is equal to firm demand for it. We also assume demand for labor to be exoge- nously determined, since we study worker behavior on the market. Hence, our analysis is focused on the supply side of the labor market rather than the demand side and firm behavior. Furthermore, we presume that the supply of labor depends on the wage rate w, the time available to workers t and their initial income , such that: o m ,, oo SwtmD The supply of labor is positively related to the wage level since a higher wage would stimulate people to sup- ply more labor, hence, . Another assumption is that the substitution effect prevails, i.e., the worker would likely substitute his leisure with work when he is stimulated by a higher wage. This assumption stems from the fact that for poor, low-paid individuals the sub- stitution effect prevails over the income effect. Being highly paid and having substantial accumulated wealth, professionals in prestigious jobs are less likely to substi- tute their free time with work for more money. They are more prone to the income effect. Being less paid and with few savings, poor peop le are more expressly su bject to the substitution effect. Thus, the greater the free time available to the individu al, the greater his supply of labor and the longer the hours he would be willing to work, i.e., . At the same time, supply of labor is negatively related to the initial endowment or income o that a worker has. Thus, a richer individual would be less likely to work and would have more leisure time. As opposed to him, a poorer person would be willing to supply more of his labor, therefore, . Furthermore, the wage rate depends on the minimum wage rate o, the educa- tional level o e, and the total free time available to workers . The function for the wage rate will be of the form: 0 w S 0 m S 0 t Sm w t , oo ww get A higher educational level would affect the wage rate positively, as more educated individuals will be em- ployed in highly paid professional jobs, i.e., . If the worker ha s a lot of leisure time then he is able to search longer for a better paid job and wage rate is posi- tively related to the free time which in this case becomes job-search time and, therefore, . Thus, we can formulate the model as: 0 e g ,t 0 tg ,,00 00 oowtm Swtm DSSS ,0 0 ooe t ww getgg0 Assuming the derivatives to be continuous, we can use the implicit-function theorem where the wage rate and time t are endogenous. The other variables are as- sumed to be exogen ous. Solving by the implicit-function theorem, we analyze the effect of initial wealth or non-labor income , as follows: w o m , 10 o wt m t o w m SS S gt m where the Jacobian is nonzero: 0 wt t JSgS Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  200 T. TODOROVA ET AL. The effect of the initial endowment on wage rate will be: 00 mt tmt ow SS gSg w mJ SgS tt The relationship is positive which means that the higher the initial income of an individual, the greater his prospects of obtaining a better paid job. This result stresses the role of heterogeneous endowments on wage differentials, which has widely been discussed in classi- cal economic literature. The positive relationship between initial endowments and wage rates can be analyzed one step further if we consider that the initial wealth in the form of accumulated capital can be readily available for human capital investment in training and education. Education and training deserve special attention here because they are major determinants of personal produc- tivity. Having in mind that the opportunity cost of human capital investment depends on the initial income of indi- viduals (usually in the form of family wealth), rich indi- viduals can finance th eir schooling and training on better terms and in general can invest more and boost future earnings. On the other hand, poor individuals face higher opportunity cost of funds even when they have the same personal abilities and talents. This inequality of opportu- nity among poor and rich individuals translates into cor- responding wage differentials no matter that their initial ability rents and productive capacities are equal. Our equilibrium labor market model implies that rich people, having an initial endowment or accumulated wealth, have more leisure time and hence more time for search: 10 0 wm m owt SS S t mJ SgS t The higher the initial inco me, the greater the free time is. Thus, rich individuals have more time to search for a better job. To trace the effects of the educational level on wage rate and search time we solve: 00 1 o wt wt t te o w e SS JSgS gg t e 0 0 t et te owt S gg Sg w eJSgS t As expected, the relationship between educational level and wage rate is positive, which confirms our ex- pectation that a higher educational level promises a higher wage. Thus, rich people with good prospects of getting better education actually have the opportunity to occupy well-paid jobs. 0 t S 10 w ewe owt gSg t eJ SgS This derivation shows that more educated people need less time to search for a better job and are less likely to experience long periods of unemployment. At the same time, the search time for the less educated and less quail- fied workers increases and they are less likely to be em- ployed at well-paid jobs. For the effect of minimum wage we solve analogously: 00 11 o wt wtt t o w SS JS gS gt w w 0t t S 10 tt ow t gS w wJ SgS As can be expected, the higher the initial wage, the greater the prospects of the individual to find a better- paid job. Poor people who start at a very low wage level have less chance of getting a higher salary later. This result has implications about the growing inequality of opportunity as different groups of workers advance in their careers. Put in a specific context, if one is employed as a janitor, he would always be perceived as a janitor and would rarely be able to jump up the professional ladder into a better paid and more prestigious job. It is as if the very perception of the job a person is taking and the wage rate he accepts determine his future career and income. By the same token, a secretary may be quite knowledgeable ab out her boss’s business, be able to per- form multiple, complex tasks, speak a number of lan- guages and be computer literate. Yet, a secretary is often perceived as “the girl who makes the coffee” or as “the typist” at best and is likely to remain a low-paid staff member. With regard to the time devoted to search we find: 0 t S 11 0 w w owt S t wJ SgS The effect of the minimum wage on the search time is negative, i.e., the higher the initial wage, the less the time dedicated to search. Thus, high-sk illed workers are likely Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  T. TODOROVA ET AL. 201 to find qualified job openings sooner than low-skilled workers f ind correspond ing low-paid jobs. The effects of the firms’ labor demand on the wage rate and search time are analyzed as follows: 10 10 o wt wtt t o D SS JS gS gt D w Solving for the two effects, 1 t S 00 t tt owt gg w DJ SgS The effect of demand for labor on the wage rate is positive, which means that, as firms demand more labor, the market wage is likely to increase. The effect of labor demand on search time is: 1 t S 10 10 w owt t DJ SgS As expected, the greater the firms’ demand for labor, the lower the search time for workers and the shorter spans of unemployment they would experience. Low-skilled jobs are characterized by long hours of tedious repetitive activities and are low-paid, as they do not require professional skills. These jobs are occupied by poor individuals who rely on subsistence level wages to live on. On the effort side, these individuals are time-constrained because they have to dedicate much more of their time working. On the in come side, they are also limited–since they earn lower incomes, their oppor- tunity costs of search are higher. Since the opportunity cost of unemployment is higher for these individuals, it is legitimate to assume that they would exert more work-efforts in order to remain employed. We consider pay-for-performance wage rate and efficiency wage theories, which incorporate the possibility that wage in- creases may stimulate productivity and work effort. The classical models of efficiency wage theories are widely developed in the 1980s and 1990s and derive a series of implications on shirking issues, labor turnover, non- clearing labor markets and unemployment [20-23]. The literature defines efficiency wage as the wage “which minimizes an employer’s wage cost per effective unit of labor service employed” [19]. We demonstrate this wage-productivity dependency graphically in Figure 1 where at the optimum firms determine efficiency wage based on work effort: The work effort-wage curve is higher for the unskilled labor, as drawn in Figure 1. Thus, at the optimum, firms s e u e s w u w Work Effort Wage Figure 1. Optimal wage for skilled and unskilled labor. end up paying less skilled workers a lower wage u, whereas the wage received by high-skilled workers is w s w. At the same time the effort for the less skilled work- ers is higher–they are supposed to work harder at the workplace and shirking is prevented by supervisors. Amidst the current world economic crisis, it is interesting to analyze this work effort-wage relationship from the perspective o f a n economic rece ss i on . In a recession highly skilled workers are less likely to be freed. Even if individuals need to switch occupations, the cost of re-training will be covered by employers or will be recovered fully by the potential future wage. There would rarely be any change to their effort-wage curve so their work effort would likely remain the same. So would the optimal wage firms pay to them. The low-skilled workers will be much more exposed to un- employment since the supply of unskilled labor will re- main relatively high in times of a crisis, yet, unemployed workers would not be able to find jobs in more profess- sional areas as skill training will be extremely costly and time-consuming for them. Since the opportunity cost of losing a job is higher for less skilled workers, th ey would increase their amount of effort in order to keep their jobs. This effect would result in an upward shift of the effort- wage curve, as depict ed by Figure 2. Although low-skilled workers would on average exert more effort in times of a recession, their opti mum wage is likely to decrease. Thus, poorer individuals will be required to work even more to earn sustainable wages and their search time for better jobs will be limited even more. Their cost of search would also increase. Thus, even the small pay obtained would be important for them and they would not opt to remain unemployed in order to search for a better job. 5. Worker Utility, Leisure and Working Time Job search can as well be analyzed from the perspective Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  202 T. TODOROVA ET AL. o CLwLm C u e u w s e u e s w u w Work Effort Wag e Figure 2. Change of optimal wage in a recession. of consumer theory where the worker is a consumer of leisure and other commodities. We investigate the rela- tionship between wage income and consumer behavior, i.e., what the optimum labor time and non-labor time that maximizes consumer utility is. Since we adopt an out-of- the-job search model for low-income workers, it is le- gitimate to say that the search time for a better job will be part of the leisure or non-work time an individual has. Here we use the terms “non-labor time,” “leisure,” “non-work time” and “job search time” interchangeably. Respectively, the “consumer” is a synonym for worker, as the latter can choose between work and leisure. We solve a standard Stone-Geary utility problem, where the consumer derives his utility from a bundle of goods, consumption and non-work time T, where is total time available to the worker, and is his working time in labor hours: CLT L 0 C mLw CLwLm C TL* t ,,UCTL Consumption must equal the worker’s income less his positive subsistence level of consumption o. His in- come consists of non-labor income (accumulated wealth or some initial endowment) and labor income where w is the pay p er labor hour and L is the number of labor hours worked. Thus, consumption can be expressed as: o Job search time will depend on the non-work time a worker has, i.e., there is a positive relationship between non-work time and search time . To find the optimal amount of labor and non-labor hours that maxi- mize utility to the worker and the effect of wage rate on the optimal labor hours, we solve the optimization prob- lem: Maximize o UCC TL where the worker’s consumption must equal his income, or: ULwL m CTL (1) Substituting exp ression (1) in the utility fun ction gives an unconstrained objective fu nct i on: Maximize o 1 UwwLmCTL Differentiating with respect to labor and setting this derivative equal to zero, 10 Lo o wL m CTL 1 o wwL m CTL 1 o wL m CTL o wTLwLm C o wTwLwLm C Thus, the optimum number of labor hours to the worker can be e xp re ss ed as: *o Lw wTm C *o mC T Lw m C (2) When non-labor income is exactly equal to basic consumption o, labor is a share of total worker time measured by the coefficient . There is a nega- tive relationship between the amount of labor hours worked and the amount of non-labor income, i.e., the higher the non-labor income a worker has, the lower the amount of labor he will perform to attain his optimal level of consumption. Adversely, labor is positively af- fected by a larger amount of subsistence consumption. Therefore, the worker has to work more hours to meet his basic needs. Alternatively, the amount of non-work time that maximizes worker utility can be expressed as: 0 * 0 Lw mC wT Tw wTm CwTwT 0 *mC wT TL This expression shows a positive relationship between non-labor (search) time and wage rate as well as between search time and non-labor income. Hence, highly paid workers face lower opportunity cost of searching for a new job. In addition, individuals that have more initial Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  T. TODOROVA ET AL. 203 accumulated wealth will tend to enjoy more free time and will have more time to search for a new better job. To see the exact effect of wage rate on optimal amount of labor hours we differentiate: 2 o mC L ww mC mC C pCp TLwL m pwL The derivative shows a positive effect of wage on the amount of labor when non-labor income exceeds basic consumption. In other words, when o, the worker has some excess income so he needs to work less and would be willing to substitute labor with leisure. How- ever, if subsistence consumption exceeds non-labor in- come, i.e., o, the income effect prevails and the worker needs to work more to reach his subsistence level. The sign of this derivative is indicative of the shape of the labor supply curve. When non-labor income exceeds minimum consumption the derivative is positive, which determines a positively sloped labor sup ply curv e, that is, labor increases with the wage level. This would be the case with a strong substitution effect when the consumer (worker) substitutes his free time with labor due to the wage incentive. Adversely, the supply curve is nega- tively sloped, if o m or the increase in the wage reduces the amount of labor. This would be the effect with a backward-bending labor supply curve when the income effect prevails over the substitution effect. The Stone-Geary utility optimization problem can have fur- ther implications if we introduce a budget constraint for the worker such th at: CT p where C is the price of consumption, T is the price of non-labor time, is wage income and m is nonwage income. The worker will have a logarithmic utility function of the fo rm: ln1 lnUCCTL CT L 1 o C where is the worker’s consumption, o is a mini- mum level of consumption, is total time and is his working time with 0 L ln1 lnUCCTL . Thus, is the worker’s non-labor time, which he uses to search for a better job. To find the optimum number of labor hours, we solve the following constrained optimization prob- lem: T Maximize o Subject to CT pCp TLwL m Introducing a Lagrange multiplier, ln1 ln o CT Z CC TL wLmp CpTL and setting the three first-order derivatives equal to zero, 0 CT ZwLmpCpTL 0Zp CC o CC (3) 1 L Zw TL 0 T p (4) From the last two equations (3) and (4) we derive: 1 CoT pCCp wTL 1 TC pwTL pC o C (5) From the budget constraint we have: CT pCwL mp TL Substituting back in (5), pwTL 1 T TCo wL mpTLp C 1 1 TC TT pTLwTLmpC wL pT LpT L o 1 1 Co T wT Lm pC wLp TL 1Co TT wTwLmp C wLwLp TpL 1Co T wTmpCwLp Tp T L 1 TT pwp Tmp Co LwC 1 1 TCo Co T Co T wwwpT mpC L Twp wTmp C Twp 11 T wp wT mpC *1Co T wTmp C LT wp As expected, the optimal number of labor hours de- pends negatively on the wage rate and non-labor income and positively on the price of free time, which is propo r- tionate to the opportunity cost of working. Thus, poor agents, whose labor income should satisfy the subsis- tence level of consumption, will face higher price of free Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  T. TODOROVA ET AL. 204 time and would work more labor hours to attain their optimum utility level of consumption. We then analyze the effects that wage rate, non-labor income and the price of free time have on the amount of free time, as well as on job search time: 1Co T wTmp C TL wp wp Free time depends positively on income from labor and non-labor sources, once basic consumption o C is satisfied. The opportunity cost of leisure is the total amount of wage lost and the price to be paid for leisure, or T. Since the individual searches for a job while not working, search time will be a fraction of non-work time. 6. Conclusions Some jobs are more dangerous and onerous than others, some offer more earning stability than others, some offer more perks in addition to the wage rate. All these differ- ences result in inequalities and wage differentials. Our results show one more cause for wage differentials–the unequal opportunities for better j obs that low-skilled and high-skilled workers face. Taking into account the costs of information and job search, we find that some seg- ments of the labor market are privileged in the job search process, ceteris paribus, simply because they can afford the time to search for these opportunities. We conclude that initial endowments cause d ifferences in the opportu- nity cost of job search and result in wage differentials- the higher the initial income of an individual, th e greater his prospects to obtain a better paid job. There is a nega- tive relationship between optimal search time for a b etter job and the potential minimum wage on that job, i.e., the higher the initial minimum wage, the smaller the search time would be. Wealthy individuals, having higher initial endowment or accumulated wealth, have more leisure time and hence more time for search which increases the value-added of their optimization problem. Wealthy individuals face lower opportunity cost of investment in education and professional training. On average, wealthy individuals are more educated and thus qualified for higher-paid jobs. More educated people need less time to search for a bet- ter job and are less likely to experience long periods of unemployment. Low-income individuals who start at low-paid jobs have smaller chance of getting high-paid jobs later. This result h as implications about the growing inequality of opportunity as different groups of workers advance in their careers. At the time of a recession low-income individuals are more prone to unemploy- ment and their search costs, work effort and income loss will increase relative to those of wealthy individuals. 7. References [1] B. Ehrenreich, “Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in America,” Metropolitan Books, May 2001. [2] G. Wallraff, “Ganz Unten,” Kiepenheuer & Witsch; Au- flage: Auflage unbekannt, 1985. [3] G. Smith, M. Venkatraman and R. R. Dholakia, “Diagnosing the Search Cost Effect: Waiting Time and the Moderating Impact of Prior Category Knowledge,” Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 20, No. 3, June 1999, pp. 285-314. [4] G. J. Stigler, “The Economics of Information,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 69, No. 3, June 1961, pp 213- 225. [5] G. J. Stigler, “Information in the Labor Market,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 70, No. 5, October 1962, pp. 94-104. [6] A. A. Alchian and W. R. Allen, “University Economics,” Wadsworth Publishing Company, Belmont, California, 1964. [7] J. J. McCall, “Economics of Information and Job Search,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 84, No. 1, February 1970, pp. 113-126. [8] D. T. Mortensen, “Unemployment Insurance and Job Search Decisions,” Industrial and Labor Relations Re- view, Vol. 30, No. 4, July 1977, pp. 505-517. [9] K. Burdett, “A Theory of Employee Job Search and Quit Rates,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 68, No. 1, March 1978, pp. 212-220. [10] C. A. Pissarides, “Search Unemployment with on-the-Job Search,” The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 61, No. 3, 1994, pp. 457-475. [11] B. Jovanovic, “Matching, Turnover, and Unemploy- ment,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 92, No. 1, 1979, pp. 108-122. [12] G. J. Van den Berg, “A Structural Dynamic Analysis of Job Turnover and the Costs Associated with Moving to another Job,” The Economic Journal, Vol. 102, No. 414, September 1992, pp. 1116-1133. [13] D. T. Mortensen, “Job Search and Labor Market Analy- sis,” In: O. C. Ashenfelter and R. Layard, Eds., Hand- book of Labor Economics, Vol. 2, 1986, pp. 849-919. [14] L. M. Kahn, “The Returns to Job Search: A Test of Two Models,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 60, No. 4, November 1978, pp. 496-503. [15] B. J. Yoon, “A Model of Unemployment Duration with Variable Search Intensity,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 63, No. 4, November 1981, pp. 599-609. [16] G. J. Van Den Berg, “Nonstationarity in job search the- ory,” The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 57, No. 2, April 1990, pp. 255-277. [17] G. S. Becker, “Human Capital and the Personal Distribu- tion of Income,” W. S. Woytinsky Lecture, No. 1, Uni- versity of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1967. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  T. TODOROVA ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME 205 [18] H. S. Faber and R. Gibbons, “Learning and Wage Dy- namics,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 111, No. 4, November 1996, pp. 1007-1048. [19] C. R. McConnell, “Contemporary Labor Economics,” McGraw-Hill, New York, January 1995, pp. 225-235. [20] G. A. Akerlof and J. L. Yellen, “Efficiency Wage Models of the Labor Market,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986. [21] L. F. Katz, “Efficiency Wage Theories: A Partial Evalua- tion,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1986, Cambridge, The MIT Press, Massachusetts, 1986, pp. 235-276. [22] J. Stiglitz, “The Causes and Consequences of the De- pendency of Quality on Price,” Journal of Economic Lit- erature, March 1987, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 1-48. [23] A. Weiss, “Efficie ncy Wages: Models of Unemployment, Layoffs, and Wage Dispersion,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1991. |