Advances in Physical Education 2013. Vol.3, No.2, 62-70 Published Online May 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ape) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2013.32010 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62 Factors Associated with Teachers’ Recruitment and Continuous Engagement of External Coaches in School-Based Extracurricular Sports Activities: A Qualitative Study Kenryu Aoyagi1, Kaori Ishii2, Ai Shibata2, Hirokazu Arai3, Chisato Hibi1, Koichiro Oka2 1Graduate School of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, Saitama, Japan 2Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, Saitama, Japan 3Faculty of Letters, Hosei University, Tokyo, Japan Email: ken-ryu.ao-yagi@ruri.waseda.jp Received January 18th, 2013; revised February 20th, 2013; accepted March 4th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Kenryu Aoyagi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. School-based extracurricular sports activity (SBECSA) has developed as an opportunity that adolescents play sports in Japan. However, there are some issues to maintain active SBECSA such as lack of teacher who can coach SBECSA expertly, and large imposition of teachers to manage SBECSA. For resolving these issues, promoting engagement of external coach is favorable. Nevertheless, the number of external coach has not been enough. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to explain facilitators and barriers related with teacher’s action for recruitment and handling with external coach, and expected qualification for external coach. Personal semi-structured interview was performed toward 22 teachers who worked in a public junior high school or a public high school. In the analysis of the present study, the KJ method―a type of qualitative analyses―was used. All transcribed data were divided into individual content and grouped together into small, middle and large categories. For facilitators, four large categories such as benefits to SBECSA, benefits to teachers, system and support were emerged. For barriers, four large categories such as negative influences on SBECSA, negative influences on teachers, system and support were grouped. For expected qualifications, five large categories such as humanity, ability, co- operativeness, attributions and trust were categorized. In conclusion, the present study identified various facilitators, barriers and expected qualifications. External coach would increase by enhancing facilitators, reducing barriers, and targeting human resource who meets expected qualifications. Keywords: Adolescent; KJ Method; Facilitator; Barrier; Expected Qualification Introduction Sports are regarded as necessary activities for people to lead a healthy and cultural life (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan: MEXT, 2011). School-based extracurricular sports activity (SBECSA) has been developed to provide an opportunity for adolescents to play sports. In Japan, SBECSA is performed after school and on weekends. Generally, teachers coach team members and manage the SBECSA. In 2009, 64.9% of junior high school students (75.5% boys and 53.8% girls) and 40.7% of high school students (54.5% boys and 26.6% girls) participated in SBECSA (MEXT, 2009b). Because of large numbers of par- ticipants, SBECSA is considered to have an enormous influ- ence on adolescents’ lives. Furthermore, MEXT has empha- sized that SBECSA should be closely associated with education in the Course of Study for junior high and high schools (cur- riculum guide for defining basic standards for education) (MEXT, 2008, 2009a). SBECSA is a very valuable activity for healthy development of adolescents. A Japanese national-wide survey for physical fitness revealed not only a cross-sectional positive relationship between participation in SBECSA and physical fitness, but also a long-term effect of SBECSA on adult physical fitness (MEXT, 2012). Farb and Matjasko (2012) reviewed previous studies for school-based extracurricular activities and adolescent develop- ment. Some positive effects of extracurricular sports activities for academic performance, educational attainment, and psy- chological adjustment are revealed in the review. Thus, it is crucial for adolescents to stay active in SBECSA to gain short-term and long-term benefits. However, there are some issues with SBECSA staying active at schools. First, some teachers are not technically able to coach the sport involved in the SBECSA at their school, even though full-time teachers generally coach SBECSA (MEXT, 1997, 2010b). According to research performed in Japan, more than half of SBECSA teachers did not have expertise to coach the sport offered at their schools (Yamagata Prefecture Board of Education, 2010). Second, SBECSA teachers are often faced with physical, monetary, and mental impositions to manage SBECSA (MEXT, 1997; Japan Senior High School Teachers and Staff Union, 2008). Third, when SBECSA teachers transfer to other schools, the SBECSA sometimes becomes inactive  K. AOYAGI ET AL. (School-based Extracurricular Sport Activity in Junior High School “Nagano Model” Exploratory Committee, 2004; Naka- zawa, 2011). Generally, Japanese teachers of public school are required to transfer to another school once every several years. Given that expert coaching relates with positive youth devel- opment (e.g., improving performance skill, confidence, positive social relationship, and morality) (Cote & Gilbert, 2009; Stew- art, Lindsay, & Trevor, 2011), expert coaches are essential in SBECSA. To resolve these issues, there has been a growing interest from schools and government in promoting engagement of external coaches in SBECSA. An external coach is defined as a person who coaches school-based extracurricular activity in- stead of or support for teacher (Sasakawa Sports Foundation, 2011). For example, human resources of external coach are a part-time teacher, sport club coach, leader of a social physical education program, graduate of the school in question, and parent of the students (All Japan High School Athletic Federa- tion, 2012). In 2010, MEXT also recommended that schools should emphasize engagement of external coaches in SBECSA (MEXT, 2010b). Actually in many cases, sports activities have been outsourced in some countries, especially extracurricular activities in Australia (Macdonald, 2011; Williams, Hay, & Macdonald, 2011). However, engagement of external coaches in SBECSA is currently inadequate in Japan. A lack of external coaches has been reported for certain sports (e.g., wrestling and archery) (Nippon Junior High School Physical Culture Asso- ciation, 2010). In addition, the number of external coaches var- ies greatly depending on prefectural area (Nishijima, Yano, & Nakazawa, 2007). In such situations, teachers also reported insufficient or limited coaching frequency and difficulty secur- ing human resources as important issues associated with re- cruitment and continuous engagement of external coaches (Mi- yagi Prefecture Board of Education, 2008; Yamagata Prefecture Board of Education, 2010). To promote engagement of external coaches, enhancement of facilitatory factors and reduction of barriers associated with teachers’ recruitment and support of external coaches would be valid strategies. In addition, to clarify how external coaches are required by teachers is important to target human resources as external coaches. However, only few Japanese and other coun- tries’ studies have examined facilitators, barriers to promoting engagement of external coaches, and qualifications expected of external coaches among full-time teachers (Miyagi Prefecture Board of Education, 2008; Yamagata Prefecture Board of Edu- cation, 2010; Williams, Hay, & Macdonald, 2011). Addition- ally, most studies were conducted by quantitative methods us- ing only few question items. Thus, previous researches may not comprehensively clarify facilitators, barriers, and expected qualifications. To identify factors associated with recruitment and continuous engagement of external coaches, qualitative research such as that involving interview is necessary. There- fore, the purposes of the present study were to clarify facilita- tors and barriers associated with recruitment and continuous engagement of external coaches as well as expected qualifica- tions of external coaches among full-time school teachers. Methods Participants The participants in the present study were 22 teachers who worked in either a public junior high school or a public high school. Participants were selected to vary demographic and occupational characteristics of the teachers, including type of school, prefecture, extracurricular activity type, and teaching subject. They were recruited from 13 prefectural areas, and managed 10 sports (i.e., basketball, judo, kendo, rowing, rub- ber-ball baseball, soccer, swimming, table tennis, tennis, and volleyball). Participants were offered a gift card worth 1000 yen for participating in the research. Participants were informed of the purpose and design of the research and written informed consent obtained from each of them. The research proposal was approved by the ethics board of Waseda University. Interview Procedure Before the interview, each participant’s demographic and occupational characteristics were obtained in writing. A per- sonal semi-structured interview was then performed. A pilot study was conducted with two teachers to modify the question items of the interview. The interview contained the following predetermined open-ended questions: 1) What are the facilita- tory factors involved in recruiting and handling external coaches? 2) What are the barriers to recruiting and handling external coaches? 3) What qualifications do you expect of ex- ternal coaches? Participants were asked to respond freely to the questions. Interview length ranged between 20 and 60 minutes. All interviews were performed at a convenient place for each participant, such as a community center or school, between June and August 2011. All interviews were audiotaped with agreement from the participants. Analysis The KJ method (Kawakita, 1970) was selected for analysis of the present study. The KJ method is one of qualitative analysis and it is erected by Jiro Kawakita in Japan. Adaptive possibility of this method in foreign countries has been indicated (Scupin, 1997). Before the analysis, each recorded interview was tran- scribed verbatim. All transcribed data were then divided into individual content by three researchers who were experts in sports education or psychology. Nearly identical contents were grouped together and corded as “small categories” in each area (i.e., facilitator, barrier, and expected qualification). For each small category, three researchers discussed and defined title of category. Next, similar small categories were further grouped into “middle categories”. Finally, the similarities and differ- ences among the middle categories produced “large categories”. In a way similar to small category, each middle and large cate- gory was entitled. Then, initial of facilitator, barrier, and ex- pected qualification with identical number was added to make discussion easier. Results Characteristics of Participants Twenty-two teachers participated in the interview (Table 1). Fourteen teachers were male, and the age of the participants ranged from 24 to 58 years with an average of 41.3 years (standard deviation = 11.7). Eleven teachers worked in a junior high school. Only three of six SBECSA teachers who recruited external coaches provided some compensation. Teachers spe- cialized not only in physical education, but also in other subjects Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63  K. AOYAGI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64 Table 1. Demographic and occupational characteristics of participants. No. Gender Age School Prefecture Extracurricular activity type Teaching subject Status External coach for the SBECSA Compensation 1 M 27 Junior high Shiga Soccer Health and physical education - No - 2 M 29 Junior high Tokyo Rubber-ball baseballMath - No - 3 M 33 Junior high Okinawa Rubber-ball baseballJapanese - Yes No 4 M 35 High Saitama Soccer Math - Yes Yes 5 M 38 Junior high Okinawa Soccer Math - No - 6 M 42 High Akita Kendo Math and information - No - 7 M 48 High Niigata Volleyball Math - Yes No 8 M 49 Junior high Fukuoka Brass band Society - Yes Yes 9 M 49 High Niigata Swimming Health and physical education - No - 10 M 52 High Akita Judo Health and physical education - No - 11 M 55 High Kanagawa Rowing Health and physical education - No - 12 M 56 Junior high Hokkaido - English Principal - - 13 M 57 Junior high Aichi - Art Principal - - 14 M 58 High Hyogo - Health and physical education Assistant principal - - 15 F 24 High Chiba Tennis Math - No - 16 F 26 Junior high Hokkaido Volleyball Health and physical education - No - 17 F 26 Junior high Nagano Table tennis English - Yes Yes 18 F 31 Junior high Aichi Basketball Math - Yes Yes 19 F 31 High Chiba Soccer Health and physical education - No - 20 F 41 High Akita Cooking Home economics - - - 21 F 48 High Kanagawa Volleyball Health and physical education - Yes No 22 F 54 Junior high Fukuoka - Technology and home economicsPrincipal - - such as math, Japanese, art, and English. Three principals and one assistant principal were also included among the partici- pants. Facilitators Four large categories of facilitators emerged (Table 2). The large categories were 1) benefits to SBECSA (e.g., growth of team members, enhancement of connection with local commu- nity, prevention of decline in coaching level by changes of SBECSA teachers); 2) benefits to teachers (e.g., reduced bur- den on SBECSA teachers, lack of teachers who can technically coach, growth of SBECSA teachers); 3) system (e.g., compen- sation, mediation of external coaches); and 4) support (e.g., introduction from acquaintances, understanding from the school). There were 17 middle categories and 50 small catego- ries for more detail in Table 2. Barriers Four large categories of barriers emerged (Table 3). The large categories were 1) negative influences on SBECSA (e.g., disregard of educational aspect, problem behavior, conflict of coaching policy); 2) negative influences on teachers (e.g., in- creased burden on SBECSA teachers, inverted status, declina- tion of teacher’s leadership ability); 3) system (e.g., lack of compensation, limitations of system, lack of cognition about system); and 4) support (e.g., opposition from others, lack of knowledge). There were 17 middle categories and 45 small categories for more detail in Table 3. Expected Qualifications Five large categories of expected qualifications emerged (Table 4). The large categories were 1) humanity (e.g., charac- ter, abidance by rules, educational thinking); 2) ability (e.g., credentials, technical coaching, experience); 3) cooperativeness (e.g., communication skill, support of SBECSA teachers); 4) attributions (e.g., age, occupation); 5) trust (e.g., acquaintances, selection by SBECSA teacher). There were 14 middle catego- ries and 52 small categories for more detail in Table 4. Discussion To explain the facilitators and barriers of recruiting and han- dling relationships with external coaches and the qualifications of external coaches expected by teachers, the personal semi- structured interview was administered to 22 teachers. As a re- sult, many novel categories were extracted and categorized in the present study. In middle category level, growth of team members, inspiring morale of team members, improvement of practice quality, enhancement of connection with local community, growth of SBECSA teachers as facilitators, and poor relationship, conflict  K. AOYAGI ET AL. Table 2. Facilitators of recruitment and handling of external coaches. Large category (4) Middle category (17) Small category (50) f1. Improving technic of team members f2. Team member contact with adults other than teacher f3. Learning about manners f4. Positive effect on mental phase f5. Showing communication with SBECSA teacher and external coach to team members f6. Desire to let team members more skillful Growth of team members f7. Ease of teaching team members courtesy toward external coach f8. Increasing motivation of team members f9. Increasing confidence of team members f10. Providing stimulation for team members f11. Having freshness for daily SBECSA f12. Bracing climate of the SBECSA f13. Conveying enthusiasm about the sport Inspiring morale of team members f14. Conveying expectations of SBECSA teacher to team members f15. Growing in practice efficiency f16. Having a diverse coaching method f17. Being able to show examples of play Improvement of practice quality f18. Increasing practice method f19. Utilizing a human network of external coaches f20. Connection with local community Enhancement of connection with local community f21. Utilizing human resources of local community f22. Improvement of safety Improvement of safety f23. Dealing with members’ injuries f24. Maintaining coaching level when SBECSA teacher changes schools Prevention of decline in coaching level by changes of SBECSA teachers f25. Ease of fit the SBECSA which has external coach when teacher changes schools Improvement of cogency f26. Having cogency Benefits to SBECSA Coordination between SBECSA teacher and parentsf27. Becoming a bridge between SBECSA teacher and parents f28. Reduced burden on SBECSA teacher f29. Help for SBECSA teacher f30. Being able to use time other than that spent on technical coaching f31. Increasing number of coaches f32. No need for SBECSA teacher to learn about the sport Reduced burden on SBECSA teachers f33. Being able to allow the SBECSA teacher to rest f34. Inability of SBECSA teacher to coach technically f35. No teachers available to become an SBECSA teacher f36. Worry for team members because of no technical coaching Lack of teachers who can technically coach f37. Complaints from team members regarding SBECSA teacher who cannot coach technically f38. Having other viewpoints f39. Closeness of external coach with team members Coaching from various perspectives f40. Seeing growth of team members in terms of the SBECSA f41. Promoting SBECSA teacher’s learning about coaching methods Growth of SBECSA teachers f42. Promoting SBECSA teacher’s learning about attitude toward team members Benefits to teachers Busyness of teacher f43. Teachers’ busyness of their work f44. System that supplies external coach with compensation f45. Increasing adoptable number of external coaches in system Compensation f46. Ease of prescribing to external coach because of supplied compensation System Mediation of external coaches f47. System that mediates external coaches f48. Availability of person to introduce external coach Introduction from acquaintances f49. Strong connection with relatives Support Understanding from the school f50. Positive attitude of school regarding engagement of external coach Note: “f” placed in front of small category means “facilitator”. Additionally, each small category was given identical number for discussion. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  K. AOYAGI ET AL. Table 3. Barriers to recruitment and handling of external coaches. Large category (4) Middle category (17) Small category (45) b1. Past failure to engage external coach b2. Having trouble with parents b3. Development of a complex human relationship b4. Break up of relationship between external coach and team members Poor relationship b5. Mismatch of SBECSA teacher and external coach b6. External coach who cannot give pupils guidance b7. Lack of understanding of external coach about school policy b8. Lack of knowledge about team member’s life in school Disregard of educational aspect b9. Too much value placed on winning b10. Physical punishment b11. Sexual harassment b12. Ranting Problem behavior b13. Misappropriating b14. Conflicting opinions with external coach Conflict of coaching policy b15. Becoming practice of SBECSA harder Negative influences on SBECSA Insufficient technical coaching b16. Developing a way to resolve immobilization of the external coach b17. Increased burden on SBECSA teacher b18. Attentiveness to external coach b19. Feeling sorry for external coach because the SBECSA was not managed well b20. Burden of only seeing external coach’s coaching Increased burden on SBECSA teachers b21. The need to try hard if external coach engages in SBECSA b22. Availability of teacher who can technically coach the sport b23. Feeling of not having to depend on external coach Decreased coaching opportunity for teacher b24. Loss of enjoyment of coaching b25. Inconvenient practice time Difficulty adjusting to external coach b26. No time for meetings Inverted status b27. Stronger influence of external coach than SBECSA teacher on team members Negative influences on teachers Declination of teacher’s leadership ability b28. Declination of teacher’s leadership ability b29. Difficulty to cancel the engagement of external coach once engaged in SBECSA b30. Cumbersome procedure to enroll external coach b31. Unclear system of introduction of external coaches b32. Uncertain system Rudimentary system b33. Large burden on external coach b34. Little compensation b35. Difficulty prescribing to external coach because of a lack of compensation (volunteer) Lack of compensation b36. Burden of compensation b37. Institutional limitation on number of external coaches Limitations of system b38. Institutional limitation on coaching frequency b39. Little knowledge of system Lack of cognition about system b40. Lack of dissemination of system System Difficulty finding external coaches b41. Difficulty finding external coaches b42. Negative attitude of school regarding engagement of external coach Opposition from others b43. Opposition to accepting external coaches who live outside of the local area b44. Having had no ideas to promote engagement of external coach Support Lack of knowledge b45. Ignorance about engagement of external coach in the school Note: “b” placed in front of small category means “barrier”. Additionally, each small category was given identical number for discussion. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66  K. AOYAGI ET AL. Table 4. Expected qualifications of external coaches by teachers. Large category (5) Middle category (14) Small category (52) e1. A person of integrity e2. Being trusted by team members e3. Having passion e4. Having general intelligence e5. A person who likes children e6. Cheerful disposition e7. A person who does not hide anything Character e8. A person who likes sports e9. No physical punishment e10. Staying on time e11. No sexual harassment e12. Having clear boundaries with team members Abidance by rules e13. Abiding by a duty of secrecy e14. Thinking of the personal progress of team members e15. Understanding that SBECSA is a school activity e16. Not only engaging in technical coaching Educational thinking e17. Not only valuing winning Humanity No business use e18. Not using status of external coach in other business e19. Expert in physical training e20. Expert with a high level technique and coach in the short-term e21. Ability to perform acupuncture or massage e22. Expert in mental training e23. A person who can engage more than one SBECSA Expert e24. Expert in nutritional guidance e25. Taken a course in coaching e26. Having credentials for coaching Credentials e27. Having teaching credentials e28. Being able to coach technically Technical coaching e29. Having knowledge about technical coaching theory e30. Having experience in coaching Ability Experience e31. Having experience in teaching e32. Being able to communicate with others e33. Fit of coaching policy with SBECSA teacher e34. Not coaching only by the external coach’s opinion Communication skill e35. Ability to communicate opinions to SBECSA teacher e36. Being an adjunct of SBECSA teacher e37. Coaching regularly e38. Becoming a bridge between SBECSA teacher and team members Cooperativeness Support of SBECSA teachers e39. Giving main position to SBECSA teacher e40. Young e41. Age from 30s to 40s e42. Elderly Age e43. Younger than SBECSA teacher e44. Civil servant e45. A person whose job is coaching SBECSA Attributions Occupation e46. Sport store staff e47. Pupil the teacher once taught e48. Introduction from acquaintance e49. Understanding the character of the person e50. Graduate student of the school Acquaintances e51. Parent of the team members Trust Selection by SBECSA teacher e52. Selection by SBECSA teacher Note: “e” placed in front of small category means “expected qualification”. Additionally, each small category was given identical number for discussion. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67  K. AOYAGI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68 of coaching policy, difficulty adjusting to external coach, lack of compensation, difficulty finding external coaches as barriers were consist with previous researches (Ibaraki Prefecture Sports Promotion Council, 2007; Yamagata Prefecture Board of Education, 2010; Williams, Hay, & Macdonald, 2011). In the facilitator for benefits to SBECSA, growth of team mem- bers was categorized (for example, “f1. improving technic of team members”, “f2. team member contact with adults other than teacher”, and “f3. learning about manners”). Especially for “f2. team member contact with adults other than teacher”, pupil guidance recommendations published by MEXT indicated that communication with local adults or coaches improves sociality and norm consciousness of children (MEXT, 2010a). Therefore, external coaches have positive effect for socialization of chil- dren. Additionally, activity with peers and adults cause higher intrinsic motivation of children than activity with peers only (Shernoff & Vandell, 2007). The result of the present study (i.e., “f8. Increasing motivation of team members” in benefits to SBECSA) also demonstrated that there are some cases which recruitment of external coach increases motivation of team members. However, disregard of educational aspects (e.g., “b6. external coach who cannot give pupils guidance” and “b9. too much value placed on winning”) and problem behavior (e.g., “b10. physical punishment” and “b12. ranting”) that could have nega- tive influences on SBECSA were categorized as barriers. In addition, educational thinking by the external coach (e.g., “e14. thinking of the personal progress of team members”, “e16. not only engaging in technical coaching”, and “e17. not only valu- ing winning”) was reported in humanity as an expected qualifi- cation. It is suggested that selecting or providing an external coach who has an educational attitude helps teachers to accept external coaches and reduce future trouble with the coaching policy between teachers and external coaches. For system among both facilitators and barriers, factors re- lated to understanding from the school were observed (e.g., “f50. positive attitude of school regarding engagement of ex- ternal coach” was a facilitator, and “b42. negative attitude of school regarding engagement of external coach” was a barrier). In most situations, school principals have the authority to de- termine the school’s management policy. Therefore, if the school principal opposes the recruitment of an external coach, it is very difficult for a teacher to recruit the external coach. En- couraging cognition of school principal for the benefits of re- cruiting external coaches clarified in the present study would facilitate engagement of external coaches. In the system of barrier, “b31. unclear system of introduction of external coaches” was revealed. A previous case study, aimed to develop a mediation system of external coach, simi- larly indicated that insufficient disclosure of information dis- turbed promotion of engagement of external coaches (Kana- gawa Prefectural Center of Physical Education, 2007; Okatsu, 2011). Disclosing information about external coaches is impor- tant to enhance teachers’ accessibility to the mediation system. Insufficient disclosure of information could relate to trust of external coaches categorized as a large category of expected qualifications. Teachers required acquaintances such as “e47. pupil the teacher once taught”, “e50. graduate student of the school”, and “e51. parent of the team members”. Previous studies also reported that most SBECSA teachers selected ex- ternal coaches from acquaintances of the teacher or former students of the school because it was easier to obtain their in- formation and they could trust these individuals more than an unknown person (Kanagawa Prefectural Center of Physical Education, 2007; Okatsu, 2011). To increase trust of external coaches, obtaining their personal information is necessary. Thus, promoting transparency of information (e.g., coaching policy or how external coaches are introduced) is crucial when organizations that manage mediation systems of external coaches, such as prefectural boards of education, modify the mediation system. Among the other barriers in system, lack of cognition about system (for details, “b39. little knowledge of system” and “b40. lack of dissemination of system”) were notable. Research in Kanagawa prefecture explained that most external coaches, teachers, and principals did not know about the coach media- tion system of Kanagawa prefecture (Kanagawa Prefectural Center of Physical Education, 2007; Kanagawa Prefecture Board of Education, 2008). Thus, it is important that the local government which manages the coach mediation system de- velops effective strategies with which to advertise the system to the school and to each teacher to promote engagement of the external coach. As negative influences on teachers, inverted status (i.e., “b27. stronger influence of external coach than SBECSA teacher on team members”) was identified. In SBECSA management guide of Ehime prefecture, disrespect for the SBECSA teacher by team members was reported as an issue arising from exces- sive dependence of the SBECSA teacher on the external coach (Ehime Prefecture Board of Education, 2011). To avoid disre- spect for SBECSA teachers by team members, cooperativeness such as “e34. not coaching only by the external coach’s opin- ion”, “e36. being an adjunct of SBECSA teacher”, and “e39. giving main position to SBECSA teacher” were interpreted as expected qualifications. As a way, clearly defining the position and roles of the external coach would enhance teachers’ actions in recruiting external coaches. In terms of expected qualifications, there were various opin- ions regarding the age group of external coaches in attributions. The study for Slovene coaches mentioned that younger coaches were more accurate, open to novelties, conscious, agreeable, and able to manage their own emotions compared with older coaches. Whereas, older coaches behaved in a more democratic manner than did younger coaches (Dimec & Kajtna, 2009). Because characteristics of each coaching method differ de- pending on the age of the coach, the teachers examined in the present study explained their preferred coaching method char- acteristics of external coaches in terms of age group. In addition, there were different opinions regarding teachers’ burdens, such as “f28. reduced burden on SBECSA teacher” in benefits to teachers versus “b17. increased burden on SBECSA teacher” in negative influences on teachers. Recognition of teachers by providing compensation in system, both of facilita- tor and barrier, also differed (e.g., “f46. ease of prescribing to external coach because of supplied compensation” as a facilita- tor versus “b35. difficulty prescribing to external coach because of a lack of compensation (volunteer)” as a barrier). Some local governments have established a system of supplying compen- sation, although many local governments do not have a media- tion and compensation supply system (Setagaya Ward Board of Education, 2009). This explains the regional difference and teachers’ personal differences in the factors associated with recruitment and handling of external coaches. A limitation of the present study is that SBECSA or  K. AOYAGI ET AL. SBECSA teacher characteristics and regional characteristics are not differentiated. Future studies must specify the relationship between the characteristics of SBECSA and teacher and the categories of facilitator, barrier, and expected qualification. While there are limitations, the present study extracted and categorized many novel facilitators, barriers, and expected qualifications related to the behavior of teachers in recruiting and handling external coaches. The participants in the present study had rich characteristic variation (e.g., type of school, prefectures located in urban and rural areas, extracurricular activity type, and teaching subject). The diversity of partici- pants helped to collect exhaustive opinions from teachers, and expand adoptive possibility for other prefectures in Japan or other countries faced similar problems such as lack of coach. Conclusion The present study identified various and detailed facilitators and barriers associated with the recruitment and continuous engagement of external coaches, as well as the expectation of their qualifications. According to the result of the present study, it is suggested that the local government which manages the coach mediation system should promote transparency of exter- nal coaches’ information and develop strategies with which to advertise the system to the school and teachers. Similarly, en- couraging cognition of school principal for the benefits of re- cruiting external coaches clarified in the present study would be valuable. As a further suggestion, selecting or providing exter- nal coaches who have an educational attitude and defining the positions and roles of external coaches clearly helps teachers to accept them and reduce future trouble with coaching policies between teachers and external coaches. Promoting engagement of external coaches would be made easier by enhancing facili- tators and ridding barriers associated with recruitment and han- dling of external coaches as well as targeting human resources who meet expected qualifications. The findings of the present study may contribute to promote engagement of appropriate external coaches, and could provide one of clues to resolve issues of SBECSA commencing with lack of coach, and achieves further youth development. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all participating teachers and the peers who introduced participants. The present study was supported by the Sasakawa Sports Research Grant (No. 120B3-010) from Sasakawa Sports Foundation, and Global COE Program “Sport Sciences for the Promotion of Active Life” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan. REFERENCES All Japan High School Athletic Federation (2012). News from head office. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.zen-koutairen.com/f_publish.html Cote, J., & Gilbert, W. (2009). An integrative definition of coaching effectiveness and expertise. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 4, 307-322. doi:10.1260/174795409789623892 Dimec, T., & Kajtna, T. (2009). Psychological characteristics of younger and older coaches. Kinesiology, 41, 172-180. Ehime Prefecture Board of Education (2011). Management guide of school-based extracurricular sport activity. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://ehime-c.esnet.ed.jp/hosupo/undoubukatudou/index.html Farb, F. A., & Matjasko, L. J. (2012). Recent advances in research on school-based extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Developmental Review, 32, 1-48. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2011.10.001 Ibaraki Prefecture Sports Promotion Council (2007). The way of future school-based extracurricular sport activity. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.edu.pref.ibaraki.jp/board/bunspo/sports/setti/toushin.pdf Japan Senior High School Teachers and Staff Union (2008). Final re- port of actual condition survey for issues of school-based extracur- ricular sport activity in 2006. Kanagawa Prefectural Center of Physical Education (2007). As regards a way of future system of registration and mediation of coach. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.pref.kanagawa.jp/uploaded/attachment/2426.pdf Kanagawa Prefecture Board of Education (2008). Research report for sport activity of secondary school student. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.pref.kanagawa.jp/uploaded/attachment/176796.pdf Kawakita, J. (1970). Zoku hassouhou. Tokyo: Chuokoron-shinsha, Inc. Macdonald, D. (2011). Like a fish in water: Physical education policy and practice in the era of neoliberal globalization. Quest, 6 3 , 36-45. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (1997). Report of investigative research for way of school- based extracurricular sport activity. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chousa/sports/001/toushin/971 201.htm Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (2008). The course of study in junior high school. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/new-cs/youryou/1304424.htm Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (2009a). The course of study in higher school. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/new-cs/youryou/1304427.htm Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (2009b). White paper on education, culture, sports, science and technology. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/hakusho/html/hpab200901/1295623. htm Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (2010a). Outline of pupil guidance. Tokyo: Kyoiku-tosho, Co., Ltd. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (2010b). Sport-oriented nation strategy: Sport community Ja- pan. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/sports/rikkoku/1297182.htm Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (2011). Basic law of sports. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/sports/kihonhou/attach/1307658.htm Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (2012). National survey result of physical and athletic capacity. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/toukei/chousa04/tairyoku/kekka/k_d etail/1326589.htm Miyagi Prefecture Board of Education (2008). Research for school- based extracurricular sport activity of secondary school. Nakazawa, A. (2011). A postwar history of extracurricular sport activi- ties in Japan (1): Focusing on the transition of the actual situation and policy. Hitotsubashi Bulletin of Social Sciences, 3, 25-46. Nippon Junior High School Physical Culture Association (2010). Spread sheet of research for number of member school and student. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www18.ocn.ne.jp/~njpa/pdf/h22gaibu2_mf.pdf Nishijima, H., Yano, H., & Nakazawa, A. (2007). A sociological study of coaching and management of club activities in junior high schools: Based on a questionnaire survey to teachers of sports club activities in two prefectures and Tokyo metropolitan. Bulletin of Faculty of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 69  K. AOYAGI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 70 Education in the Univer sity of Tokyo, 47, 101-130. Okatsu, S. (2011). Way of utilizing local human resource in SBECSA: Challenge of SBECSA external coach in Nagoya. Toho Gakushi, 40, 35-46. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.aichi-toho.ac.jp/outline/files/201106004001_03.pdf Sasakawa Sports Foundation (2011). Installation of sports leader bank in each prefecture. Sports White Paper: Future that Sports Should to Aspire, 86-88. School-Based Extracurricular Sport Activity in Junior High School “Nagano Model” Exploratory Committee (2004). Proposal of school- based extracurricular sport activity in junior high school “Nagano model”. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.pref.nagano.lg.jp/kyouiku/taiiku/bukatu/teigen/teigen.pdf Scupin, R. (1997). The KJ method: A technique for analyzing data derived from Japanese ethnology. Human Organization, 56, 233-237. Setagaya Ward Board of Education (2009). “Support of SBECSA, detachment of school councilor” in Setagaya ward. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chukyo/chukyo3/042/siryo/__i csFiles/afieldfile/2009/03/19/1247451_4 Shernoff, J. D., & Vandell, L. D. (2007). Engagement in after-school program activities: Quality of experience from the perspective of participants. Journal of Yout h an d Adolescence, 36, 891-903. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9183-5 Stewart, V., Lindsay, O., & Trevor, C. (2011). The role of the coach in facilitating positive youth development: Moving from theory to prac- tice. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23, 33-48. doi:10.1080/10413200.2010.511423 Tokyo Metropolitan Board of Education (2008). Companion of coach- ing school-based extracurricular activity for external coach. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.kyoiku.metro.tokyo.jp/press/bukatsu_tebiki.pdf Williams, J. B., Hay, J. P., & Macdonald, D. (2011). The outsourcing of health, sport and physical educational work: A state of play. Physical Education and Spor t Pedagogy, 16, 399-415. doi:10.1080/17408989.2011.582492 Yamagata Prefecture Board of Education (2010). As regards a way of future school-based extracurricular sport activity. URL (last checked 17 January 2013). http://www.pref.yamagata.jp/ou/kyoiku/700021/21unndoubukatudou arikata.pdf

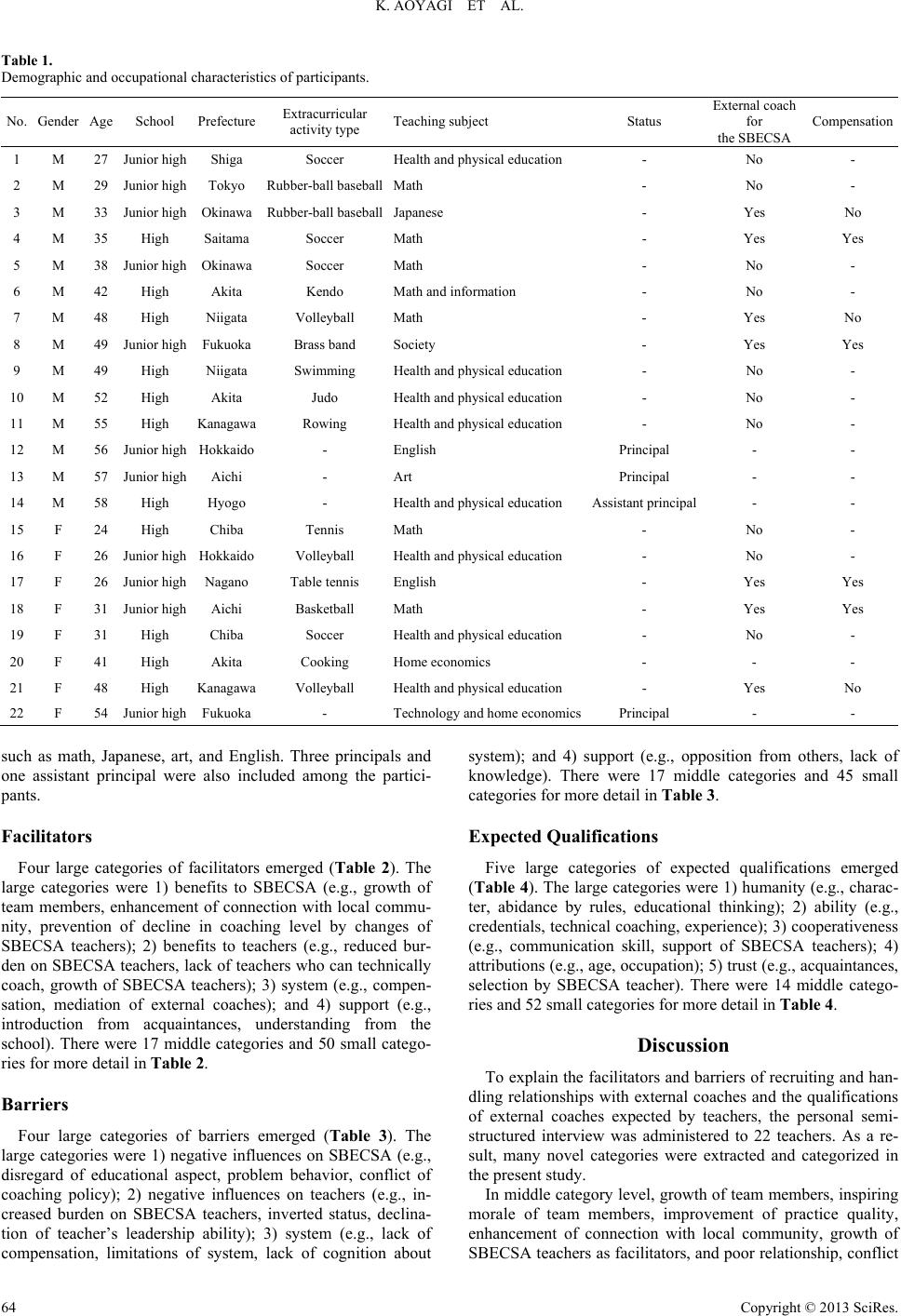

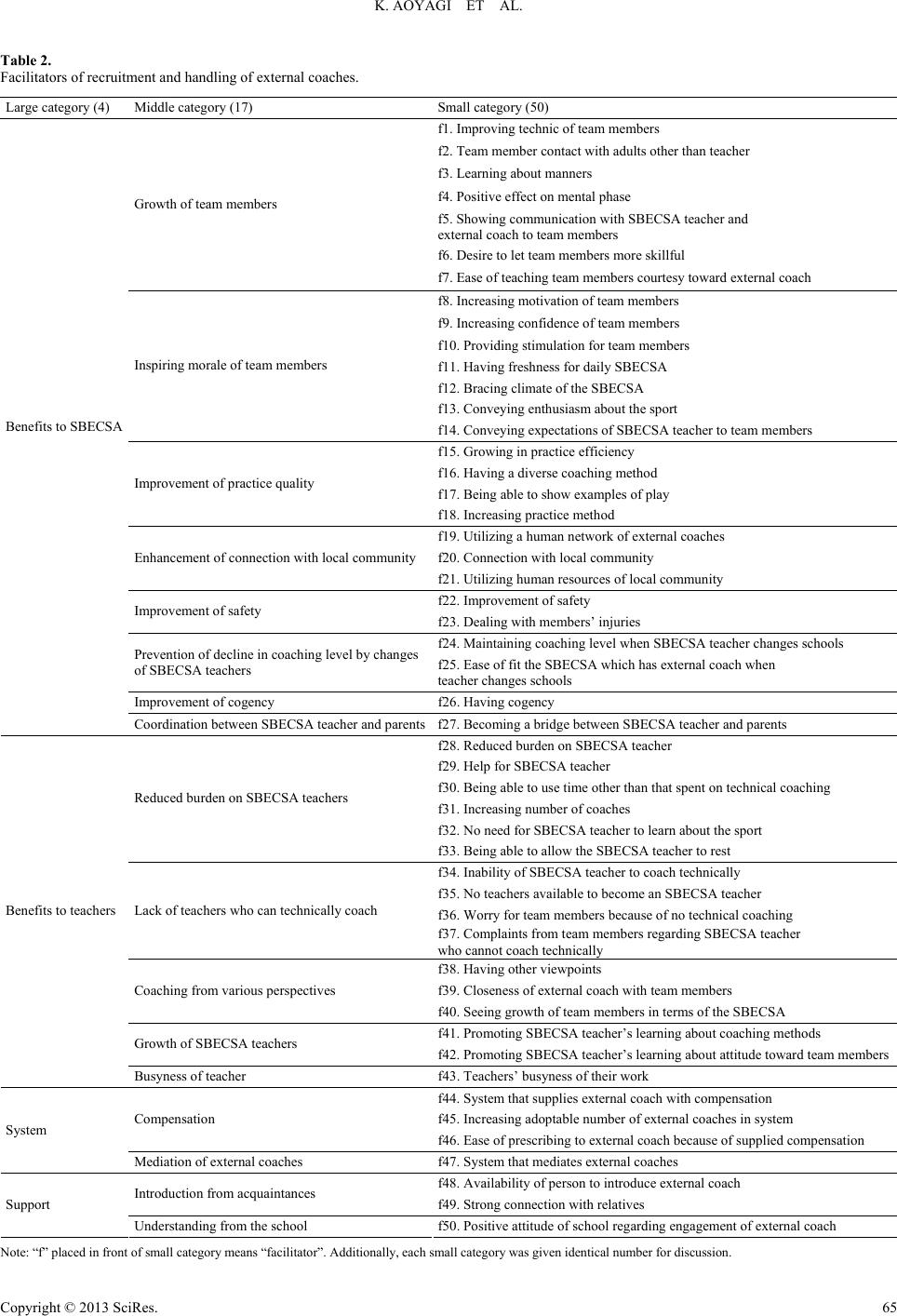

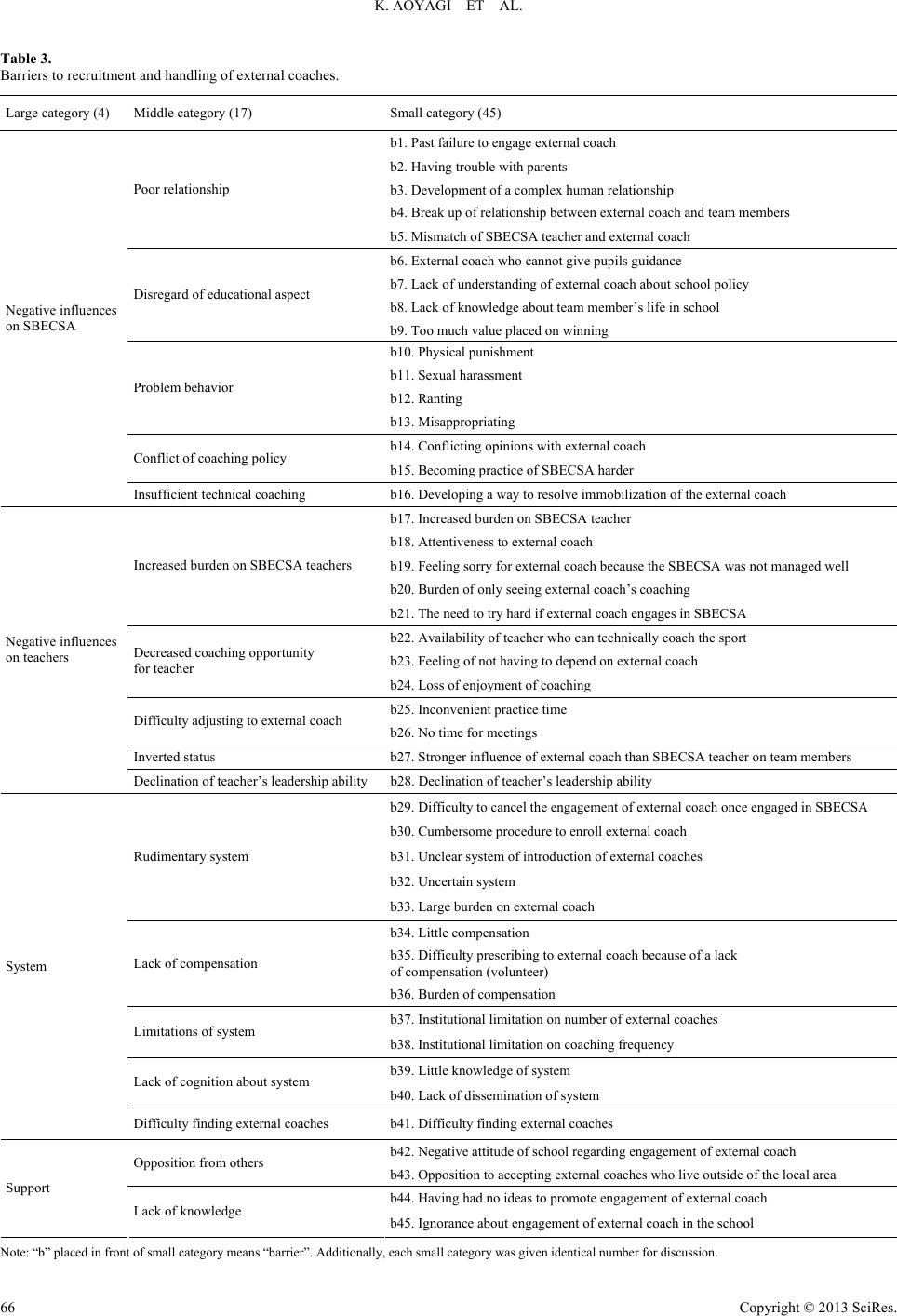

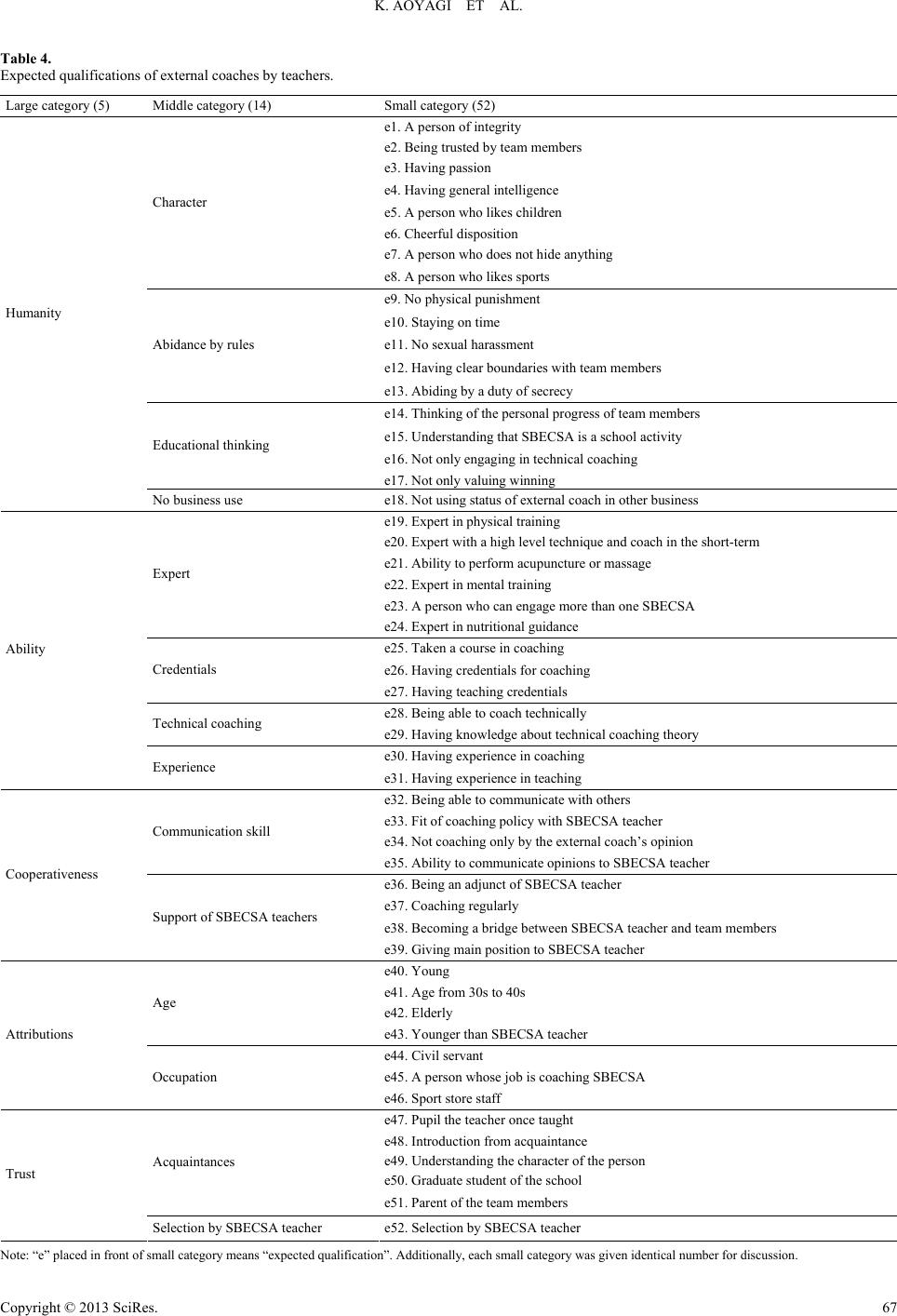

|