Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

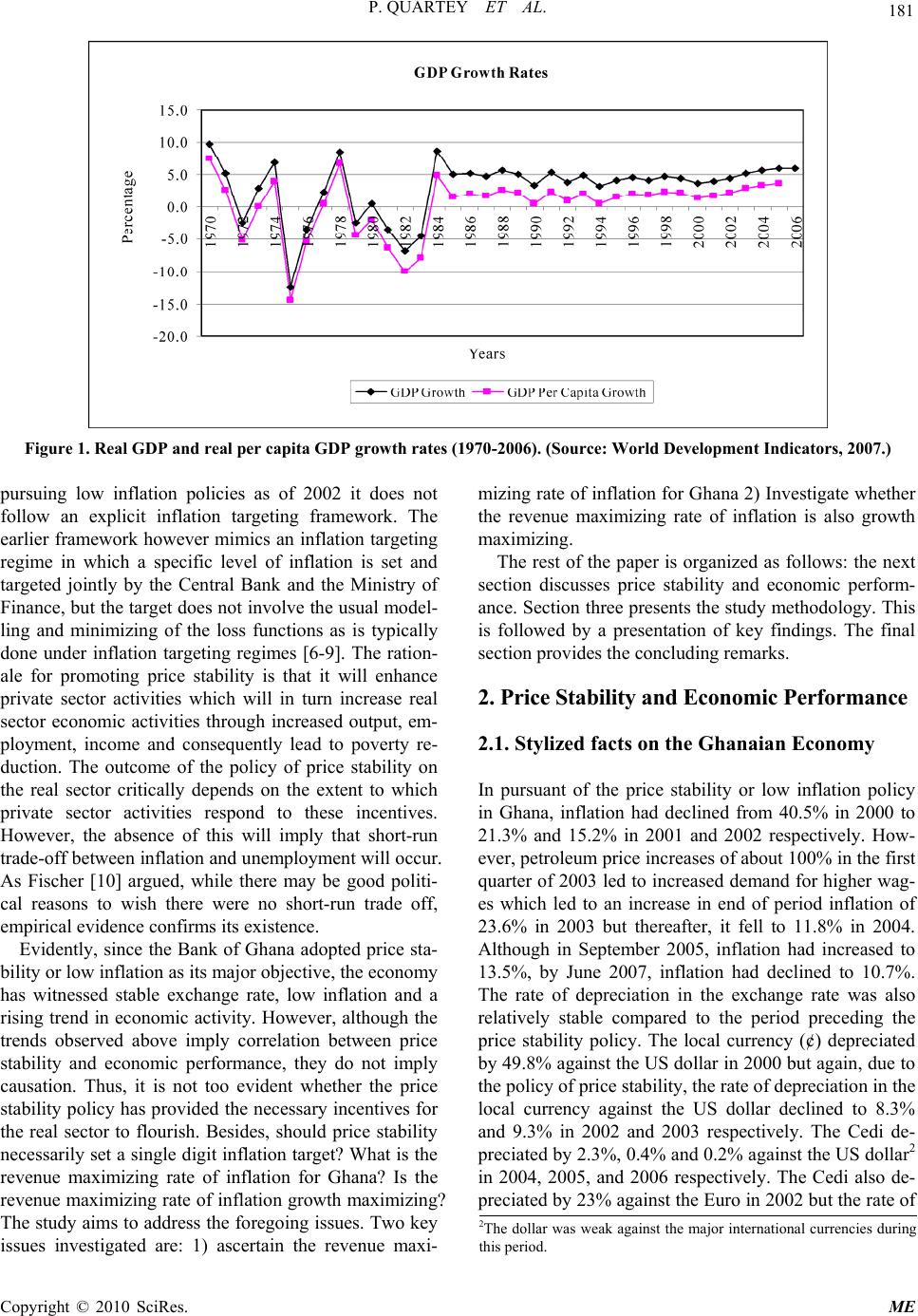

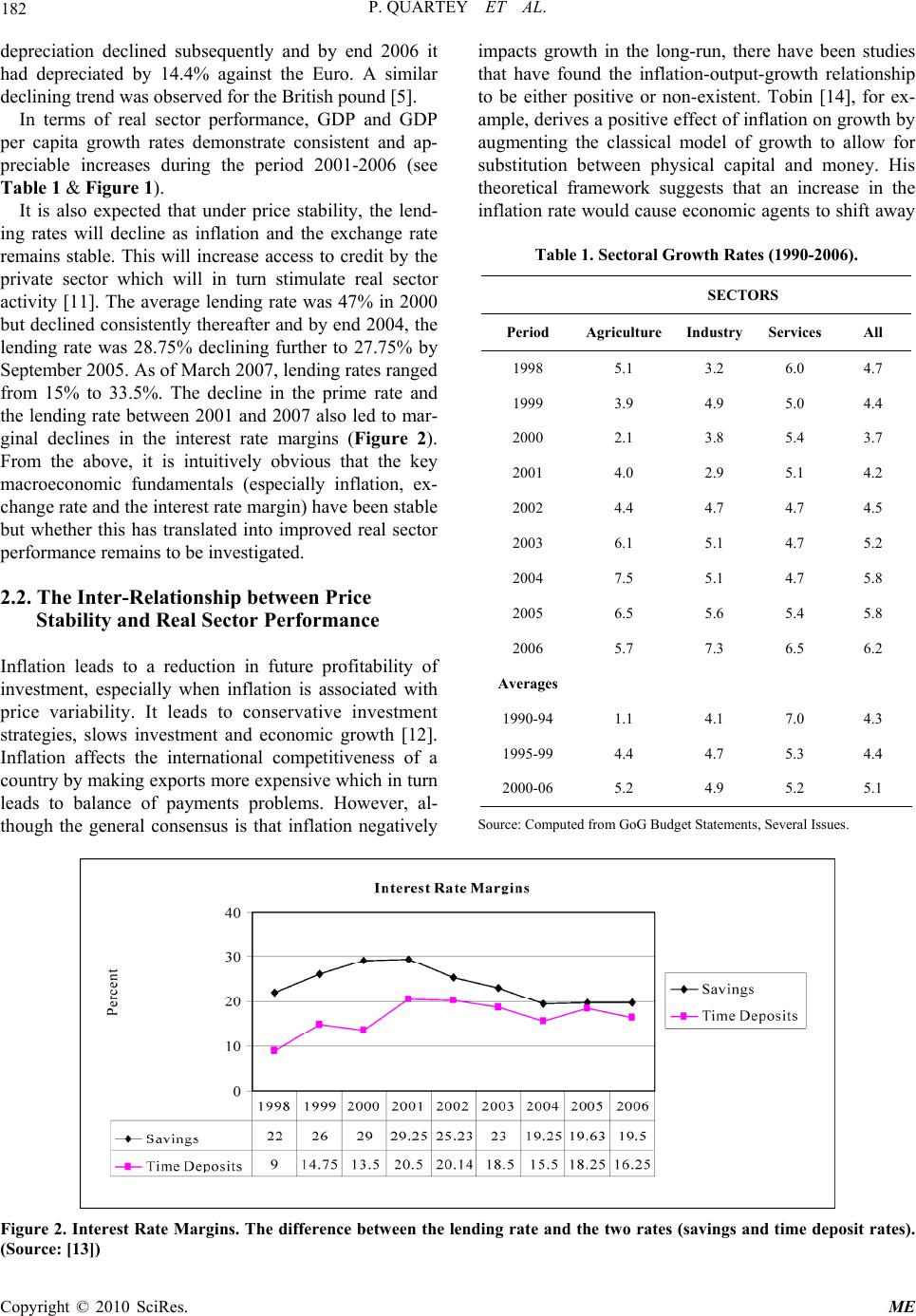

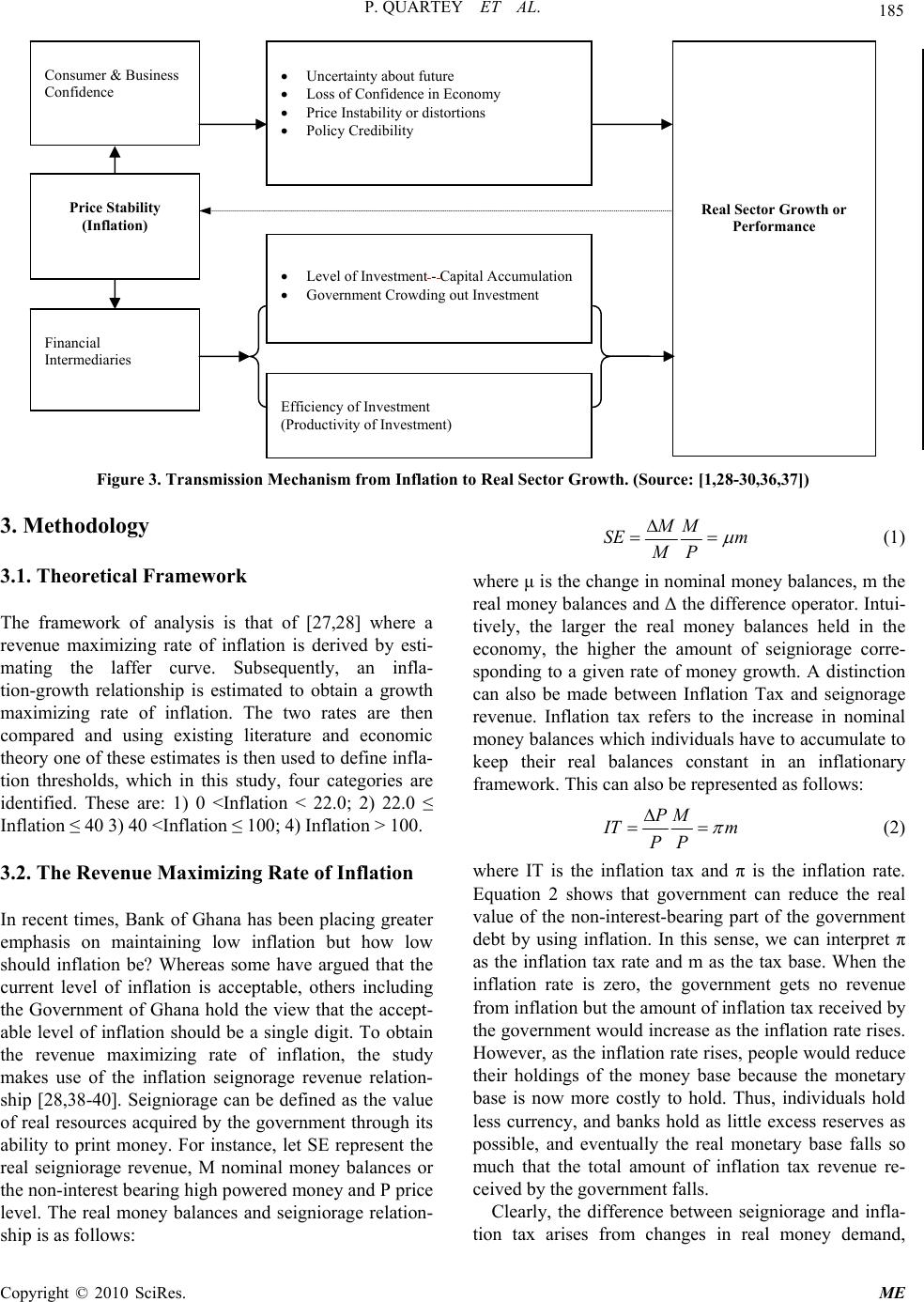

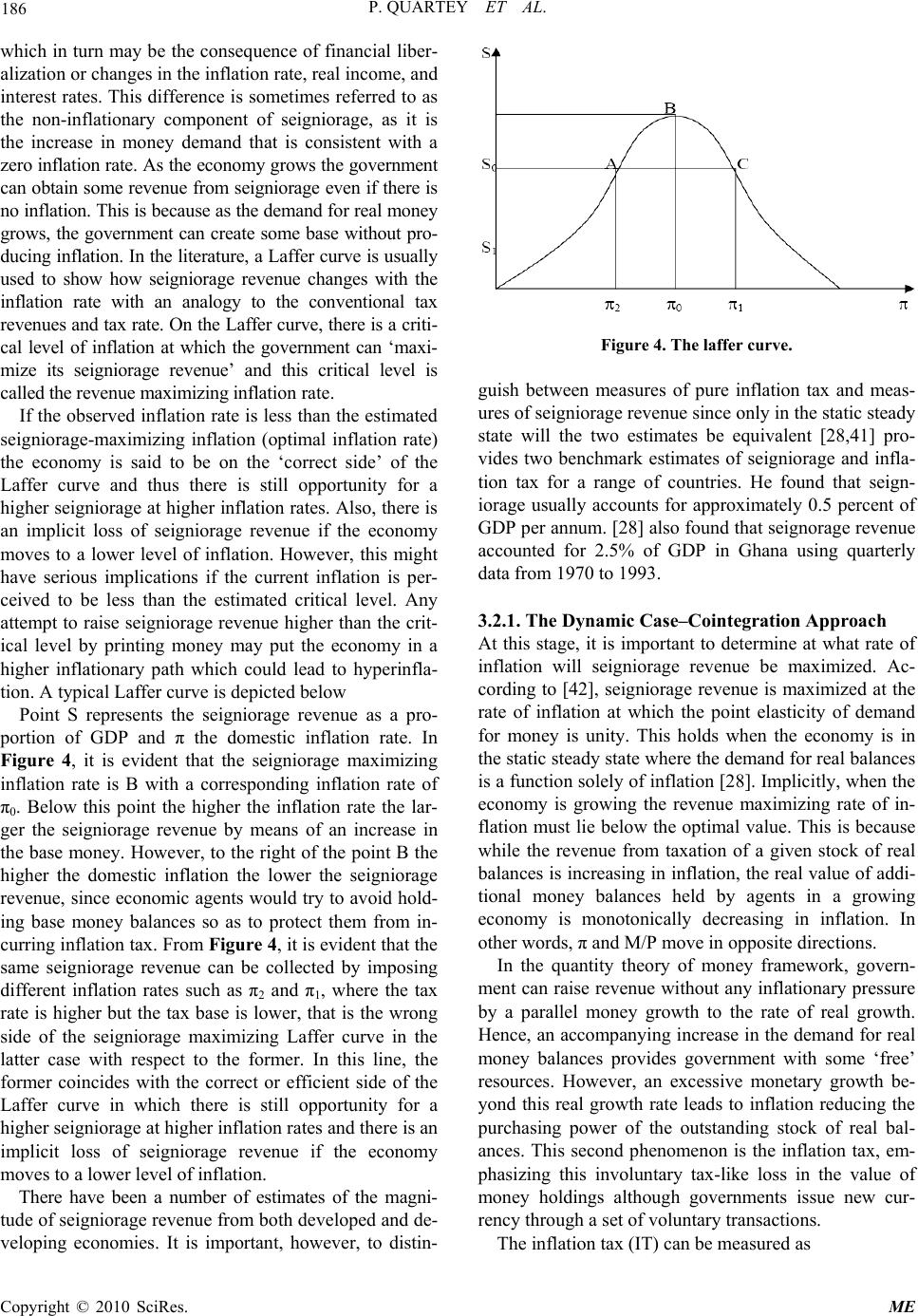

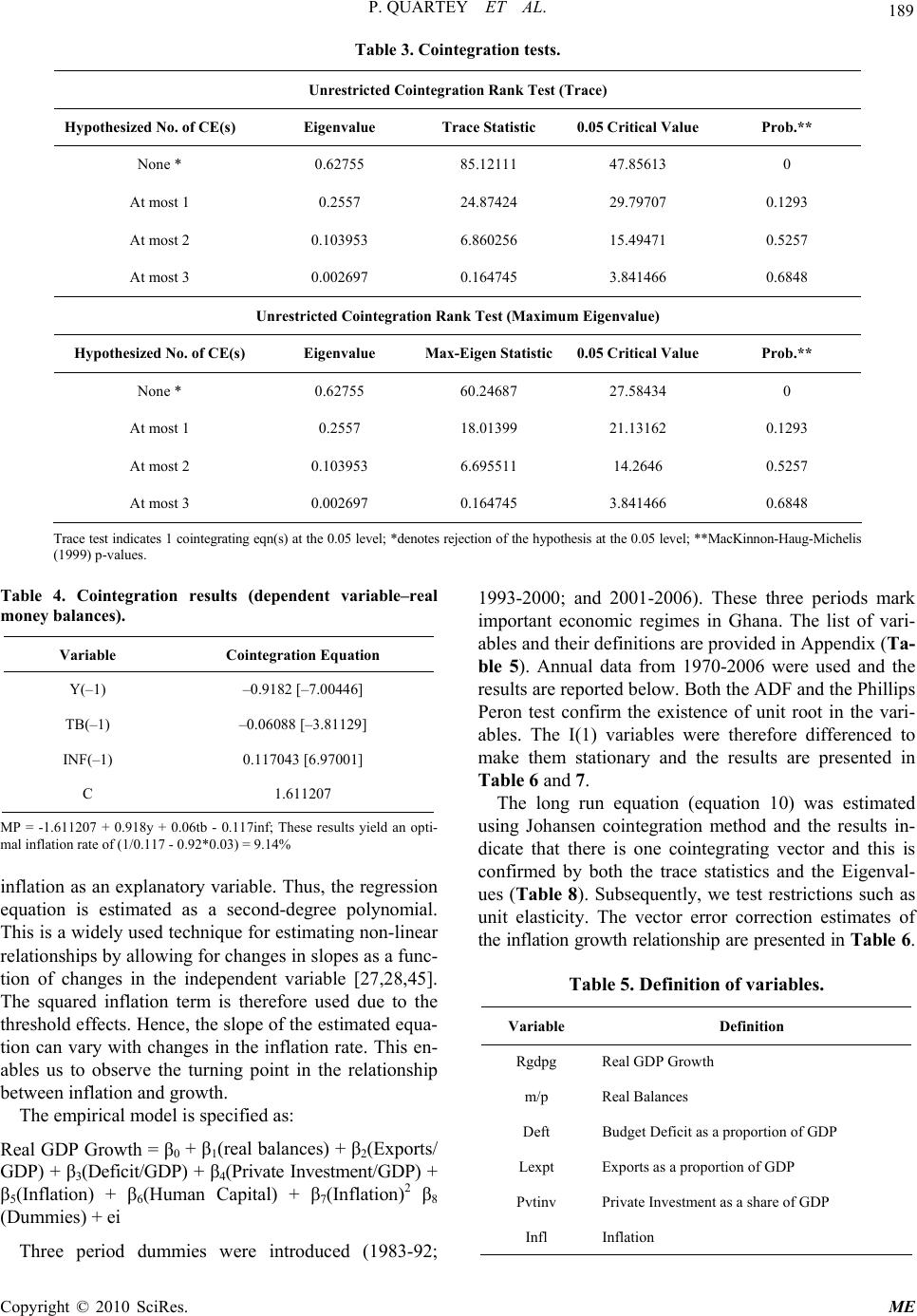

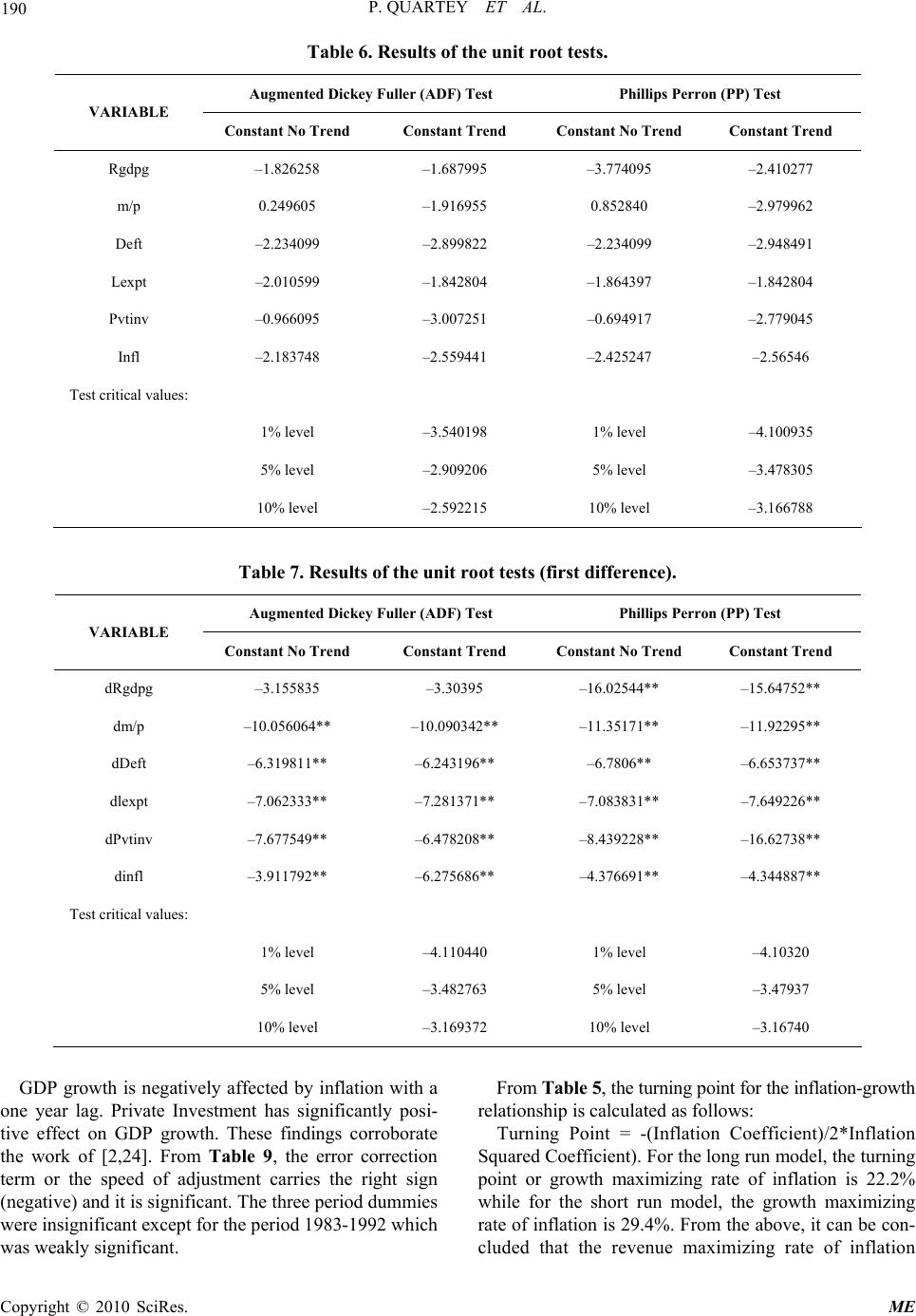

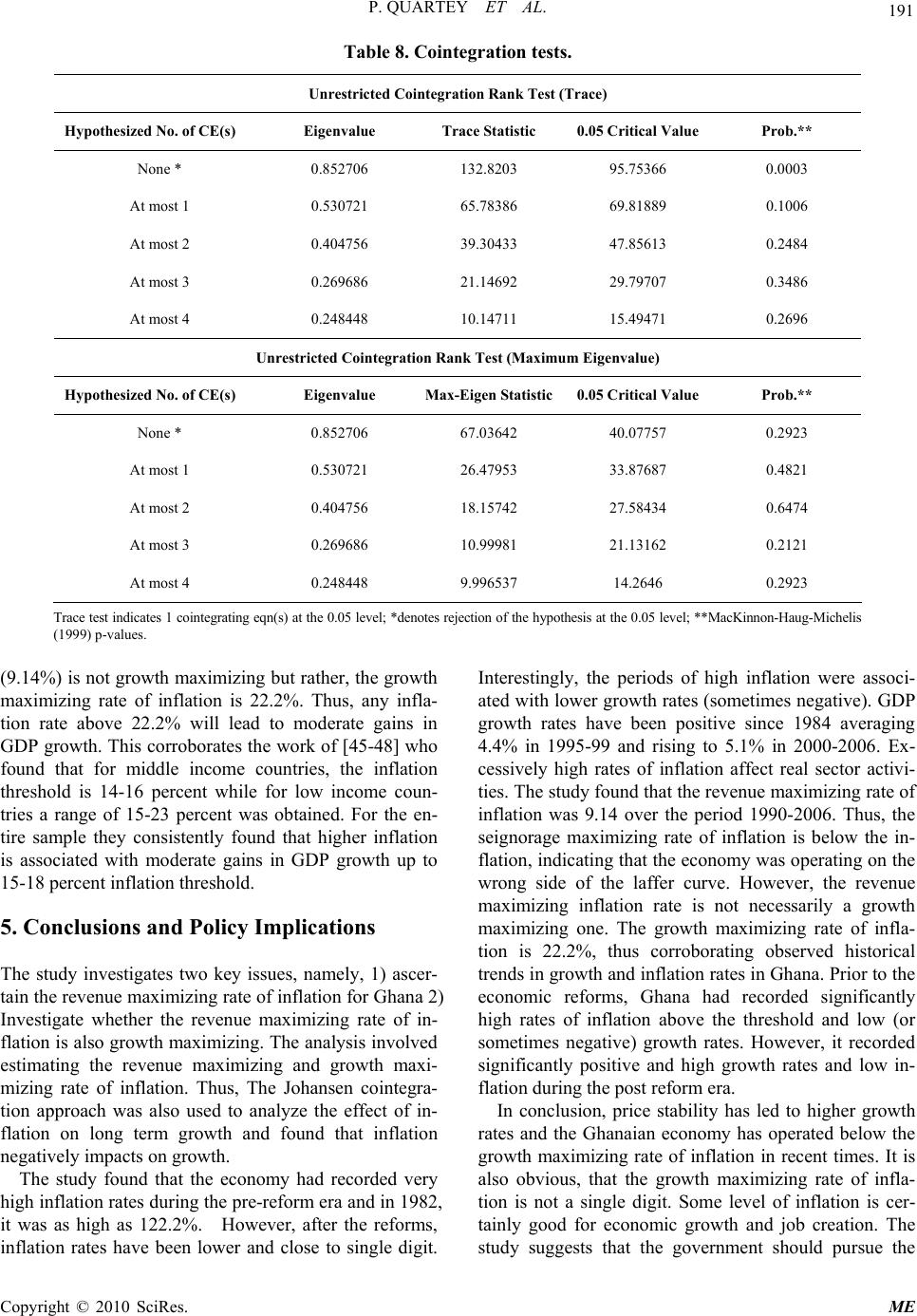

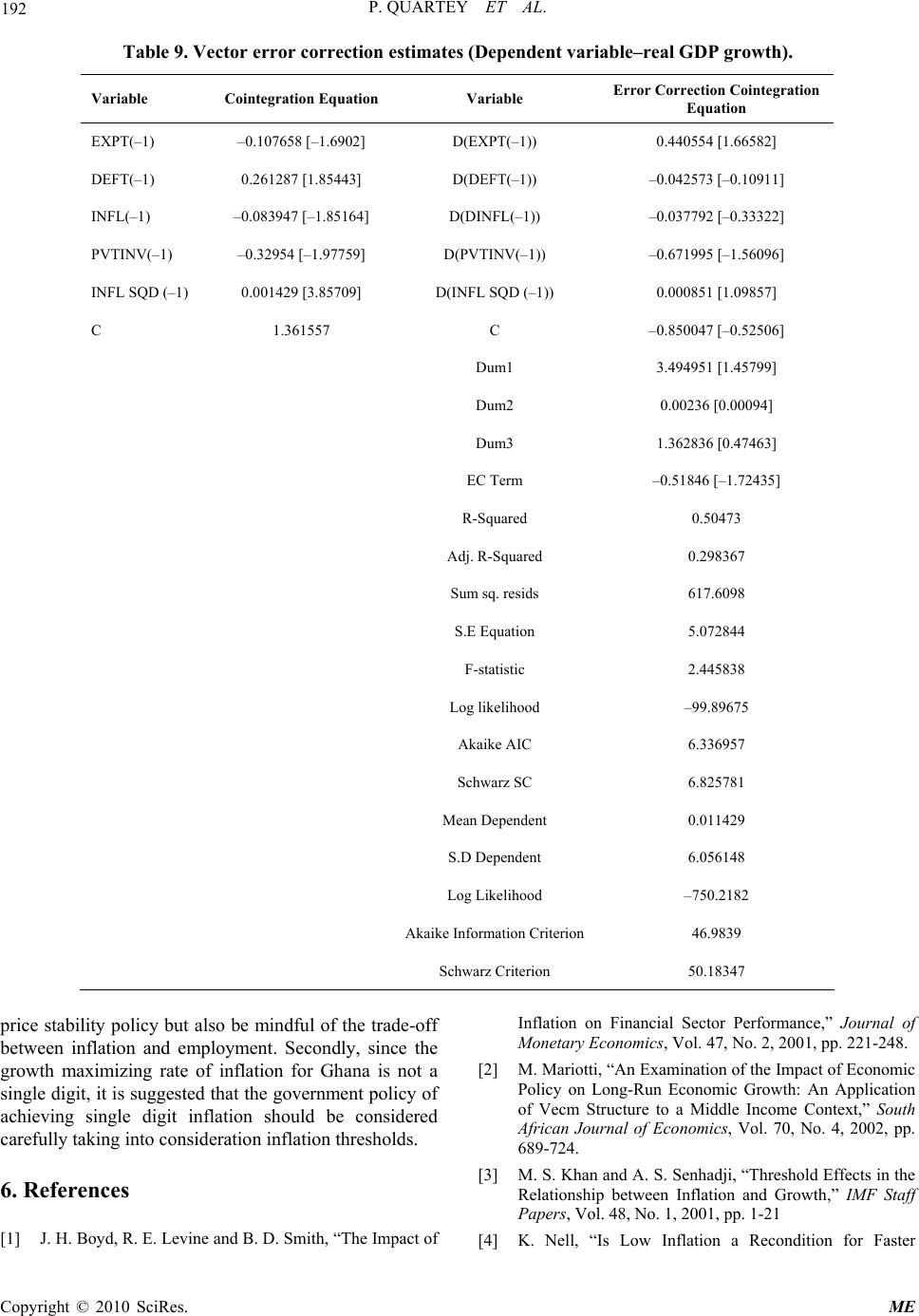

Modern Economy, 2010, 1, 180-194 doi:10.4236/me.2010.13021 Published Online November 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME Price Stability and the Growth Maximizing Rate of Inflation for Ghana* Peter Quartey ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon, C hana E-mail: pquartey@ug.edu.gh Received August 10, 2010; revised September 15, 2010; accept ed September 18, 2010 Abstract Monetary policy in Ghana, which is typical of many central banks, over the years, has focused on ensuring price stability or low inflation. The aim of the policy of price stability is to provide a stable environment for real sector activities to flourish. However, the outcome of the policy on real sector activities has not been subjected to any empirical investigation and this forms the focus of the study. For instance, the Central Bank has focused on single digit inflation and whether such a low rate is growth maximizing is yet to be ascer- tained. The study therefore investigates the revenue maximizing and the ‘growth maximizing’ rate of infla- tion for Ghana using data from Bank of Ghana and WDI. The study finds that economic performance is higher under low inflation era than when inflation is high. It also established the revenue maximizing rate of inflation using the Laffer curve approach is lower than the growth maximizing rate of inflation. Also, from the results, it can be deduced that the single digit inflation target set by the Central bank is not growth maxi- mizing. Keywords: Economic Development, Fiscal and Monetary Policy 1. Introduction The maintenance of low inflation and or price stability has been the focus of many countries since evidence abound that sustained and predictable high rates of infla- tion can have adverse effects on economic growth or real sector activities [1]. Although there is no general con- sensus on the effect of inflation on growth, several em- pirical studies have found that inflation negatively affect the real sector [2]. Of particular interest is a study on both industrialized and developing countries on the infla- tion growth nexus which found the existence of a thresh- old level of inflation beyond which the inflation growth relationship is negative [3,4]. Many developing countries have historically recorded persistently high rates of inflation particularly from early 1970 to the 1990s. Similarly, Ghana has had a long his- tory of very high rates of inflation over the same period. In 1971, inflation measured as the change in the consumer price index was 9.6% but rose consistently and by 1977 it had reached 116.4% [5]. Although the rate of inflation declined thereafter, it was short-lived and by 1983 it had reached 122.9%. The introduction of the Economic Re- covery programme (ERP) saw inflation declining to 40% in 1984. Subsequently, the rate of inflation has been within 10% to 40% except in 1995 when the rate of in- flation increased to 59.5% but declined consistently to 12.4% in 1999. The year 2000 was an election year and many of the macroeconomic fundamentals including inflation were unstable. It is not surprising that the high inflationary era also coincided with low real sector per- formance in Ghana (see Figure 1). In view of the inverse relationship between inflation and economic performance, the Bank of Ghana has con- sistently pursued low inflation policies in order to accel- erate real sector performance. Since 2002, consistent with its mission statement, the Bank of Ghana has fol- lowed the policy of price stability1, particularly; low in- flation and a fairly stable exchange rate [6] It must be emphasized that although the Central Bank has been *Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, University of Ghana & Deputy Head, Centre for Migration Studies, University of Ghana. Dr. Samuel Donyina-Ameyaw, Bank o f Ghana, made useful contributions to this report. I acknowledge suppor t from the African Economic Research Consortium. 1The Bank of Ghana’s mission statement states ‘Our mission is to pur- sue sound monetary and financial policies aimed at price stability and create an enabling environment for sustainable economic growth’. See www.bog.gov.gh/  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME 181 Figure 1. Real GDP and real per capita GDP growth rates (1970-2006). (Source: World Development Indicators, 2007.) pursuing low inflation policies as of 2002 it does not follow an explicit inflation targeting framework. The earlier framework however mimics an inflation targeting regime in which a specific level of inflation is set and targeted jointly by the Central Bank and the Ministry of Finance, but the target does not involve the usual model- ling and minimizing of the loss functions as is typically done under inflation targeting regimes [6-9]. The ration- ale for promoting price stability is that it will enhance private sector activities which will in turn increase real sector economic activities through increased output, em- ployment, income and consequently lead to poverty re- duction. The outcome of the policy of price stability on the real sector critically depends on the extent to which private sector activities respond to these incentives. However, the absence of this will imply that short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment will occur. As Fischer [10] argued, while there may be good politi- cal reasons to wish there were no short-run trade off, empirical evidence confirms its existence. Evidently, since the Bank of Ghana adopted price sta- bility or low inflation as its major objective, the economy has witnessed stable exchange rate, low inflation and a rising trend in economic activity. However, although the trends observed above imply correlation between price stability and economic performance, they do not imply causation. Thus, it is not too evident whether the price stability policy has provided the necessary incentives for the real sector to flourish. Besides, should price stability necessarily set a single digit inflation target? What is the revenue maximizing rate of inflation for Ghana? Is the revenue maximizing rate of inflation growth maximizing? The study aims to address the foregoing issues. Two key issues investigated are: 1) ascertain the revenue maxi- mizing rate of inflation for Ghana 2) Investigate whether the revenue maximizing rate of inflation is also growth maximizing. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: the next section discusses price stability and economic perform- ance. Section three presents the study methodology. This is followed by a presentation of key findings. The final section provides the concluding remarks. 2. Price Stability and Economic Performance 2.1. Stylized facts on the Ghanaian Economy In pursuant of the price stability or low inflation policy in Ghana, inflation had declined from 40.5% in 2000 to 21.3% and 15.2% in 2001 and 2002 respectively. How- ever, petroleum price increases of about 100% in the first quarter of 2003 led to increased demand for higher wag- es which led to an increase in end of period inflation of 23.6% in 2003 but thereafter, it fell to 11.8% in 2004. Although in September 2005, inflation had increased to 13.5%, by June 2007, inflation had declined to 10.7%. The rate of depreciation in the exchange rate was also relatively stable compared to the period preceding the price stability policy. The local currency (¢) depreciated by 49.8% against the US dollar in 2000 but again, due to the policy of price stability, the rate of depreciation in the local currency against the US dollar declined to 8.3% and 9.3% in 2002 and 2003 respectively. The Cedi de- preciated by 2.3%, 0.4% and 0.2% against the US dollar2 in 2004, 2005, and 2006 respectively. The Cedi also de- preciated by 23% against the Euro in 2002 but the rate of 2The dollar was weak against the major international currencies during this period.  182 P. QUARTEY ET AL. depreciation declined subsequently and by end 2006 it had depreciated by 14.4% against the Euro. A similar declining trend was observed for the British pound [5]. In terms of real sector performance, GDP and GDP per capita growth rates demonstrate consistent and ap- preciable increases during the period 2001-2006 (see Table 1 & Figure 1). It is also expected that under price stability, the lend- ing rates will decline as inflation and the exchange rate remains stable. This will increase access to credit by the private sector which will in turn stimulate real sector activity [11]. The average lending rate was 47% in 2000 but declined consistently thereafter and by end 2004, the lending rate was 28.75% declining further to 27.75% by September 2005. As of March 2007, lending rates ranged from 15% to 33.5%. The decline in the prime rate and the lending rate between 2001 and 2007 also led to mar- ginal declines in the interest rate margins (Figure 2). From the above, it is intuitively obvious that the key macroeconomic fundamentals (especially inflation, ex- change rate and the interest rate margin) have been stable but whether this has translated into improved real sector performance remains to be investigated. 2.2. The Inter-Relationship between Price Stability and Real Sector Performance Inflation leads to a reduction in future profitability of investment, especially when inflation is associated with price variability. It leads to conservative investment strategies, slows investment and economic growth [12]. Inflation affects the international competitiveness of a country by making exports more expensive which in turn leads to balance of payments problems. However, al- though the general consensus is that inflation negatively impacts growth in the long-run, there have been studies that have found the inflation-output-growth relationship to be either positive or non-existent. Tobin [14], for ex- ample, derives a positive effect of inflation on growth by augmenting the classical model of growth to allow for substitution between physical capital and money. His theoretical framework suggests that an increase in the inflation rate would cause economic agents to shift away Table 1. Sectoral Growth Rates (1990-2006). SECTORS Period AgricultureIndustry Services All 1998 5.1 3.2 6.0 4.7 1999 3.9 4.9 5.0 4.4 2000 2.1 3.8 5.4 3.7 2001 4.0 2.9 5.1 4.2 2002 4.4 4.7 4.7 4.5 2003 6.1 5.1 4.7 5.2 2004 7.5 5.1 4.7 5.8 2005 6.5 5.6 5.4 5.8 2006 5.7 7.3 6.5 6.2 Averages 1990-94 1.1 4.1 7.0 4.3 1995-99 4.4 4.7 5.3 4.4 2000-06 5.2 4.9 5.2 5.1 Source: Computed from GoG Budget Statements, Several Issues. Figure 2. Interest Rate Margins. The difference between the lending rate and the two rates (savings and time deposit rates). Source: [13]) ( Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME 183 from holding money and to move towards more capital investments, thereby increasing output. The money-in- utility function model developed by Sidrauski [15], on the other hand, finds that in the long run money is neutral such that a rise in the rate of monetary expansion would raise prices but leave the capital stock and output level unaffected. One of the early works that established a negative long-run association between inflation and growth is that of Stockman [16] who presented a cash-in-advance mod- el of an economy in which money complemented capital. Later work by Fischer [17] reinforced this negative rela- tionship by stressing the role of macroeconomic uncer- tainty in reducing the level of productivity and the rate of investment. Rousseau and Wachtel [18] empirically ex- plored the indirect role of financial sector development in explaining the negative relationship between inflation and growth. They argue that, a well developed and active financial sector encourages a higher level of capital for- mation and most importantly leads to improved alloca- tion of capital. In an inflationary environment, however, financial in- termediaries would be reluctant to offer long-term fi- nancing for capital formation and growth, and the vari- ous measures (e.g. interest rate ceilings and credit alloca- tion) instituted by government to protect certain sectors of the economy would lead to inefficient allocations of capital that inhibit growth. Other studies have also found a negative link between inflation and growth. For in- stance, Gillman et al. [19] studied 29 OECD and 18 APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) countries from 1961 to 1997 and found a negative relationship between inflation and economic performance. Similarly, Barro [20] examined over 100 countries between the years 1960 and 1990 and found a negative relationship between inflation and growth. Recent literature on the inflation-growth relationship has been focused on the threshold effects of inflation on growth. The possibility of this nonlinear effect of infla- tion on growth was first examined by Fischer [17] who found that the association between inflation and growth weakens as inflation rises. The general view now, how- ever, is that there exists a threshold level of inflation be- low which the effect of inflation on growth is either posi- tive or zero, and above which inflation has a negative impact on growth. Bruno and Easterly [21-23], for ex- ample, have cited evidence of a negative, short-to-me- dium term relationship between high inflation (i.e. an inflation rate of 40 percent or more) and growth, and no evidence of a relationship between inflation and growth at annual inflation rates less than 40 percent. Khan and Senhadji [3] using a sample of 140 devel- oping and industrial countries between 1960 and 1998 and also find evidence of the existence of a threshold level of inflation beyond which the inflation-growth rela- tionship is negative. Their findings also indicated that this threshold level of inflation is higher for developing countries (at 7-11 percent) than for industrialized ones (1-3 percent). Similarly, Nell [4] study on the inflation- ary episodes in South Africa (over the period 1960-1999) also finds that single digit inflation may be beneficial to growth while double digit inflation rates may be growth retarding. Mariotti [2] using the Johansen Cointegration approach found an inverse relationship between inflation and economic growth. Similarly, Hodge [24] in examin- ing the inflation-growth nexus for South Africa over the period 1950-2002 confirmed the negative relationship between inflation and growth over the medium to long-run using the OLS method. He also adds that coun- tries that maintain low inflation enjoy higher rates of economic growth than countries with high rates of infla- tion. It is important to add that ‘a certain amount of infla- tion may help grease the wheels of the economy’ [25,26]. Thus, the evidence abounds from the above literature that inflation negatively affects economic performance and goes to confirm the existence of the threshold effect. Unfortunately, these studies are mostly cross-country, used simple OLS and have not been applied to Ghana except in the case of [27,28] where the optimal rate of inflation from 1970 to 1993 were estimated. It must be noted that a lot has happened after this period and the optimal rate of inflation as well as the inflation growth nexus may have change and it is this gap in our knowl- edge that this study intends to fill. 2.3 The Transmission Mechanism from Inflation to Real Variables The process through which changes in the monetary pol- icy get transmitted to the ultimate objectives like infla- tion or growth has come to be known as “monetary transmission mechanism”. Interestingly, economists of- ten refer to the channels of “monetary transmission” as a black box–implying that we know that monetary policy does influence output and inflation but we do not know for certain how precisely it does so. Moreover, the im- pact of inflation on real variables is not certain. Nevertheless, in the literature, a number of transmis- sion channels have been identified: (a) the quantum channel (e.g., relating to money supply and credit); (b) the interest rate channel; (c) the exchange rate channel; and (d) the asset price channel. How these channels function in a given economy depends on the stage of development of the economy and its underlying financial structure. Illustratively, in an open economy, one would expect the exchange rate channel to be important; simi-  184 P. QUARTEY ET AL. larly, in an economy where banks are the major source of finance (as against the capital market), credit channel seems to be a major conduit for monetary transmission. Besides, it needs to be noted that these channels are not mutually exclusive – in fact, there could be considerable feedbacks and interactions among them. Although the channels explain how inflation or price stability affects the real sector there is lack of consensus on the adverse effect of inflation on real sector variables. Studies have shown that at lower rates of inflation, the relationship is not significant and can be positive; but at higher rates, inflation has a significantly negative effect on growth. For instance, [21] demonstrated that a num- ber of economies have experienced sustained inflation between 20-30% with no major adverse consequences on the real sector but once the rate of inflation exceeds a critical level estimated at 40% inflation, significant de- clines in the level of real sector activity is recorded. In a later study [3] estimated the inflation threshold level to be 1-3% for industrial countries and 11-12% for devel- oping countries. Thus, there is some kind of consensus that excessively high rates of inflation adversely affect real sector activities. However, the main channel through which this occurs is yet to be established. Empirical studies have suggested that the financial market might be an important channel through which inflation affects growth. Under this hypothesis, there is a critical rate be- yond which inflation has a significantly negative effect on financial markets, but below which inflation has no significant effect on financial markets [1,29,30]. If the inflation-finance nexus is true, then one would expect that the effect of inflation on growth shows a sim- ilar pattern to that of inflation on financial market per- formance. The general transmission mechanism is as follows: inflation reduces the real return on savings and therefore exacerbates an informational friction afflicting the financial system [1,31]. This financial market friction can cause credit rationing which will affect the level of investment, reduce the efficiency of investment and con- sequently affect real sector performance. Reference [32] argue that inflation exacerbates the frictions in the credit markets. However, in a well functioning credit market, banks can easily adjust nominal interest rates when they need to but frictions create obstacles that impede this adjustment. Ceilings on interest rates imposed by gov- ernments are typical examples of such obstacles. However, Choi et al. [31] suggest that credit market friction is less harmful at low rates of inflation, that is, at low inflationary environments, credit rationing might not occur at all and the adverse effect of inflation on capital accumulation is no more. In such a case, higher inflation reduces the rate of return on savings and consequently increases capital accumulation; a Mundell-Tobin-effect that makes higher inflation lead to higher long run levels of real activity. However, once inflation exceeds a criti- cal level, credit rationing occurs and higher rates of in- flation can have adverse consequence on the real sector. The transmission from low inflation to real sector per- formance is described in Figure 3. Inflation can affect the real sector through financial intermediaries and subsequently directly affect growth. Empirical studies have shown that different measures of financial sector development are strongly and positively correlated with the level of investment, the efficiency of investment and real economic growth [34-35]. A major channel through which inflation affects the real sector through the banking system is by reducing the overall amount of credit available to businesses. Higher inflation can decrease the real rate of return on assets which will in turn discourage saving but encourage borrowing. New borrowers who enter the market are likely to be of lesser quality and are more likely to default on their loans. Banks may respond to the low real rates coupled with the influx of riskier borrowers by rationing credit. When financial intermediaries ration credit in this way, the re- sult is lower investment in the economy. Lower invest- ments tend to reduce the present and future productivity of the economy which in turn lowers real economic ac- tivity [32]. It must be emphasized that the effect of infla- tion on the financial sector occurs at a certain threshold of inflation. Credit rationing occurs when inflation rises above some critical level but beneath a certain threshold, higher inflation might actually lead to increased real economic activity. Inflation can also affect the real sector by reducing busi- ness or consumer confidence through future price uncer- tainties, general loss of confidence in the economy, or through price distortions (Figure 3). Inflation confuses price signals and makes it difficult for firms to ascertain whether an increase in their price reflects a general in- crease in the overall price level (shared by all goods) or an increase in their price relative to all other prices–this increases uncertainty and reduces economic activity. Inflation also increases the effective tax to firms and in- dividuals. For firms, inflation reduces the value of de- preciation allowance thereby increasing the effective tax rate. For individuals, inflation increases the effective tax rate on capital income and it discourages capital forma- tion and long term growth. From the discussions so far, evidence strongly support the view that high inflation above a certain threshold negatively affect real sector performance and low infla- tion spurs real sector activity. The next section adopts the above transmission mechanism or framework in Figure 3 to ascertain the effect of low inflation policy or price stability on the real sector in Ghana. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME 185 Consumer & Business Confidence Figure 3. Transmission Mechanism from Inflation to Real Sector Growth. (Source: [1,28-30,36,37]) 3. Methodology 3.1. Theoretical Framework The framework of analysis is that of [27,28] where a revenue maximizing rate of inflation is derived by esti- mating the laffer curve. Subsequently, an infla- tion-growth relationship is estimated to obtain a growth maximizing rate of inflation. The two rates are then compared and using existing literature and economic theory one of these estimates is then used to define infla- tion thresholds, which in this study, four categories are identified. These are: 1) 0 <Inflation < 22.0; 2) 22.0 ≤ Inflation ≤ 40 3) 40 <Inflation ≤ 100; 4) Inflation > 100. 3.2. The Revenue Maximizing Rate of Inflation In recent times, Bank of Ghana has been placing greater emphasis on maintaining low inflation but how low should inflation be? Whereas some have argued that the current level of inflation is acceptable, others including the Government of Ghana hold the view that the accept- able level of inflation should be a single digit. To obtain the revenue maximizing rate of inflation, the study makes use of the inflation seignorage revenue relation- ship [28,38-40]. Seigniorage can be defined as the value of real resources acquired by the government through its ability to print money. For instance, let SE represent the real seigniorage revenue, M nominal money balances or the non-interest bearing high powered money and P price level. The real money balances and seigniorage relation- ship is as follows: MM SE m M P (1) where μ is the change in nominal money balances, m the real money balances and Δ the difference operator. Intui- tively, the larger the real money balances held in the economy, the higher the amount of seigniorage corre- sponding to a given rate of money growth. A distinction can also be made between Inflation Tax and seignorage revenue. Inflation tax refers to the increase in nominal money balances which individuals have to accumulate to keep their real balances constant in an inflationary framework. This can also be represented as follows: PM I T PP m (2) where IT is the inflation tax and π is the inflation rate. Equation 2 shows that government can reduce the real value of the non-interest-bearing part of the government debt by using inflation. In this sense, we can interpret π as the inflation tax rate and m as the tax base. When the inflation rate is zero, the government gets no revenue from inflation but the amount of inflation tax received by the government would increase as the inflation rate rises. However, as the inflation rate rises, people would reduce their holdings of the money base because the monetary base is now more costly to hold. Thus, individuals hold less currency, and banks hold as little excess reserves as possible, and eventually the real monetary base falls so much that the total amount of inflation tax revenue re- ceived by the government falls. Clearly, the difference between seigniorage and infla- tion tax arises from changes in real money demand, Financial Intermediaries Level of Investment - Capital Accumulation Government Crowding out Investment Efficiency of Investment (Productivity of Investment) Real Sector Growth or Performance Uncertainty about future Loss of Confidence in Economy Price Instability or distortions Policy Credibility Price Stability (Inflation)  186 P. QUARTEY ET AL. which in turn may be the consequence of financial liber- alization or changes in the inflation rate, real income, and interest rates. This difference is sometimes referred to as the non-inflationary component of seigniorage, as it is the increase in money demand that is consistent with a zero inflation rate. As the economy grows the government can obtain some revenue from seigniorage even if there is no inflation. This is because as the demand for real money grows, the government can create some base without pro- ducing inflation. In the literature, a Laffer curve is usually used to show how seigniorage revenue changes with the inflation rate with an analogy to the conventional tax revenues and tax rate. On the Laffer curve, there is a criti- cal level of inflation at which the government can ‘maxi- mize its seigniorage revenue’ and this critical level is called the revenue maximizing inflation rate. If the observed inflation rate is less than the estimated seigniorage-maximizing inflation (optimal inflation rate) the economy is said to be on the ‘correct side’ of the Laffer curve and thus there is still opportunity for a higher seigniorage at higher inflation rates. Also, there is an implicit loss of seigniorage revenue if the economy moves to a lower level of inflation. However, this might have serious implications if the current inflation is per- ceived to be less than the estimated critical level. Any attempt to raise seigniorage revenue higher than the crit- ical level by printing money may put the economy in a higher inflationary path which could lead to hyperinfla- tion. A typical Laffer curve is depicted below Point S represents the seigniorage revenue as a pro- portion of GDP and π the domestic inflation rate. In Figure 4, it is evident that the seigniorage maximizing inflation rate is B with a corresponding inflation rate of π0. Below this point the higher the inflation rate the lar- ger the seigniorage revenue by means of an increase in the base money. However, to the right of the point B the higher the domestic inflation the lower the seigniorage revenue, since economic agents would try to avoid hold- ing base money balances so as to protect them from in- curring inflation tax. From Figure 4, it is evident that the same seigniorage revenue can be collected by imposing different inflation rates such as π2 and π1, where the tax rate is higher but the tax base is lower, that is the wrong side of the seigniorage maximizing Laffer curve in the latter case with respect to the former. In this line, the former coincides with the correct or efficient side of the Laffer curve in which there is still opportunity for a higher seigniorage at higher inflation rates and there is an implicit loss of seigniorage revenue if the economy moves to a lower level of inflation. There have been a number of estimates of the magni- tude of seigniorage revenue from both developed and de- veloping economies. It is important, however, to distin- Figure 4. The laffer curve. guish between measures of pure inflation tax and meas- ures of seigniorage revenue since only in the static steady state will the two estimates be equivalent [28,41] pro- vides two benchmark estimates of seigniorage and infla- tion tax for a range of countries. He found that seign- iorage usually accounts for approximately 0.5 percent of GDP per annum. [28] also found that seignorage revenue accounted for 2.5% of GDP in Ghana using quarterly data from 1970 to 1993. 3.2.1. The Dynami c C ase–C oi ntegration Appr oach At this stage, it is important to determine at what rate of inflation will seigniorage revenue be maximized. Ac- cording to [42], seigniorage revenue is maximized at the rate of inflation at which the point elasticity of demand for money is unity. This holds when the economy is in the static steady state where the demand for real balances is a function solely of inflation [28]. Implicitly, when the economy is growing the revenue maximizing rate of in- flation must lie below the optimal value. This is because while the revenue from taxation of a given stock of real balances is increasing in inflation, the real value of addi- tional money balances held by agents in a growing economy is monotonically decreasing in inflation. In other words, π and M/P move in opposite directions. In the quantity theory of money framework, govern- ment can raise revenue without any inflationary pressure by a parallel money growth to the rate of real growth. Hence, an accompanying increase in the demand for real money balances provides government with some ‘free’ resources. However, an excessive monetary growth be- yond this real growth rate leads to inflation reducing the purchasing power of the outstanding stock of real bal- ances. This second phenomenon is the inflation tax, em- phasizing this involuntary tax-like loss in the value of money holdings although governments issue new cur- rency through a set of voluntary transactions. The inflation tax (IT) can be measured as Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  P. QUARTEY ET AL. 187 1. PP M IT PP (3) The demand for real money balances takes a central place in the study of seigniorage. However, other factors apart from inflation explain the demand for money. In the standard analysis the money demand is mainly a function of inflation, and real income: , D M P . (4) Domestic and foreign assets substitution effects affect the demand for money. Thus, the demand for money function can be expressed in a homogenous logarithmic form as mymmb mr Myb P r (5) where M and P are the log of nominal money and prices respectively, y is real income, П is the rate of inflation, b is the rate of return on foreign assets (expected deprecia- tion in the parallel exchange rate) and r is the domestic interest rate (opportunity cost of domestic base money). b and r have been expressed in the form of log (1 + x). Re-arranging (5) and taking its time derivative gives the growth in nominal money demand as g ggg mymmbmr g M yb r g (6) where, g denotes the growth rate (approximated by dlog x/dt) of the variables. Substituting the above into (1), the long run seignorage revenue expression is derived as . gggg mymmb mr SmM mybr (7) Assuming a money market equilibrium where Пg = 0 so that maximizing S with respect to П and rearranging the first order conditions, a revenue maximizing value of inflation rate is obtained as * g g mymb mr mybr m g t (8) The first term on the right represents the inverse of the semi-elasticity of the demand for money with respect to inflation since the demand for money function is the semi-logarithm form in inflation. Cagan’s unit-elasticity results is arrived at by imposing the restrictions yg = bg + rg = 0. However, unit-elasticity only holds in the static steady state. However, in general, the overall tax rate on real balances is the sum of the inflation tax component and the real money balances component. The revenue maximizing rate of inflation will be affected by the rate of income growth. Thus when income is growing, all other things constant, the overall tax rate is above the inflation rate. This occurs when inflation elasticity is monotonically increasing in the inflation rate then the rate at which revenue remains the same on the margin must be less than the value which will yield unit elastic- ity. Thus, once asset market effects are incorporated in the demand for money function it becomes impossible to ascertain analytically where it will lie but it is possible to examine a number of stylized facts such as periods of stagnation or stabilization and liberalization [28]. Using an econometric approach, the money demand function above is estimated. Two key issues worth noting are that the results are derived from the long run equilib- rium demand for money function. Also, the possibility of implicit weak exogeneity of the regressors of the condi- tional model derived above is violated if inflation is en- dogenous. To address these two issues, the [43,44] coin- tegration method is employed. The long-run money demand function can be refor- mulated in a cointegrating system as follows: 11ttktk t XXXD (9) where X is a p x 1 non-stationary vector of variables, namely, real money balances, real income, the domestic interest rate, the premium on the parallel market rate and the rate of inflation. Whereas μ contains the constants of the system, D is a vector of centred seasonal dummies while ε1 … εT are error terms which are assumed to be independently normally distributed. The variables are integrated of Order one and therefore a first difference operator (∆) is applied. Subsequently, the equation in first difference can be written as 11tt ktkkt ktkt t XXX X XD 1k (10) where Г1 = -(I-Пi - Пi) (i = 1…k-1), and П = -(I-Пi - Пi) The above equation shows the stationary error-correction first difference Vector Autogressive (VAR) framework where the Г i∆Xt-k terms measure the short run dynamic behaviour of the system while the ПiXt-k terms is the long-run information (in levels) between the variables in the VAR. ПiXt-k will be consistent with the stationary VAR as long as it is also stationary and also the elements of X are cointegrated. Thus, the number of cointegrated vectors v between the elements of X will therefore de- termine the rank of the vector П. П= -αβ’ where α and β are v x p, with β containing the cointegrating vectors while α measures the speed of adjustment from disequi- librium or the feedback mechanism. The next section will estimated the revenue maximiz- ing rate of Inflation for Ghana from 1970 to 2006 using the following data sources: 1) Domestic Money Bank Credit (1970-2006)-obtained from WDI and ISSER SGER 2) GDP (1970-2006)–available from the World De- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME 188 velopment Indicators 2007 3) Lending and Deposit Rates (from 1970-2006)-ob- tained from Bank of Ghana 4) Inflation (both monthly, quarterly and annual from 1970-2006) obtained from World Development Indica- tors and/or Bank of Ghana 5) Business Confident Index (Available from June 2003 to June 2007). This is a bi-monthly data collected by the Central on Business Perceptions about economic progress 6) World Development Indicators (investment, popu- lation growth, income per capita, secondary enrolment) 4. Findings 4.1. The Optimal Rate of Inflation The evidence from the early 1990s to date is particularly interesting; although inflation has declined, seigniorage revenues have fallen further. Seigniorage revenues aver- aged 0.9 per cent of GDP from 2001 to end 2006 with inflation tax revenues averaging approximately 2.3 per cent of GDP over the same period (i.e. 2001-2006). The results are particularly striking because the liberalization pursued to date has lowered transactions cost and in- creased the opportunities for substitution between do- mestic base money and foreign currency holding. Tables 3 and 4 present the estimates of the unit root test and the cointegrating system. The VAR is estimated with a constant, seasonal dummy and six lags on each variable (real income, real money balances, rate of infla- tion, rate of return on foreign assets proxied by the ex- pected depreciation of the parallel exchange rate and the domestic interest rate) over the period 1990:1 to 2006:4. The lag length was selected based on the SBC and the Akaike Criteria. Unit root test were carried out on the variables and those found to be non-stationary were dif- ferenced (Table 2 and 3). The VAR was estimated em- ploying the modified Cagan framework and the revenue maximizing rate of inflation for Ghana is computed (See Table 4). The results are robust and show that the reve- nue maximizing rate of inflation for Ghana is 9.14 per cent using quarterly data over the period 1990-2006. The results also compares favourably with those of other studies [28] where the revenue maximizing rate of infla- tion between 1973 and 1990 was estimated to be around 15 per cent for Ghana. The study shows that the seign- iorage maximising inflation rate for Ghana is below the actual inflation rate, thus making the economy to lie on the ‘wrong side’ of the Laffer curve. The current infla- tion of 12.8 per cent is above the optimum level of 9.14 per cent. Another key issue yet to be addressed is whether the revenue maximizing rate of inflation is also the growth maximizing rate. This forms the focus of the next section. 4.2. The Growth Maximizing Rate of Inflation–Cointegrati on Appr oac h To address the issue of whether the revenue maximizing rate of inflation is also growth maximizing, a cointegra- tion framework is used to analyze the inter-relationships between growth and inflation. The approach is to build a non-linear model which includes the squared term on Table 2. Results of the unit root tests. Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) Test Phillips Perron (PP) Test VARIABLE Constant No Trend Constant Trend Constant No Trend Constant Trend Rgdpg –1.826258 –1.687995 –3.774095 –2.410277 m/p 0.249605 –1.916955 0.852840 –2.979962 Deft –2.234099 –2.899822 –2.234099 –2.948491 Lexpt –2.010599 –1.842804 –1.864397 –.842804 Pvtinv –0.966095 –3.007251 –0.694917 –2.779045 Infl –2.183748 –2.559441 –2.425247 –2.56546 Test critical values: 1% level –3.540198 1% level –4.100935 5% level –2.909206 5% level –3.478305 10% level –2.592215 10% level –3.166788  P. QUARTEY ET AL. 189 Table 3. Cointegration tests. Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test (Trace) Hypothesized No. of CE( s) Eigenvalue Trace Statistic 0.05 Critical Value Prob.** None * 0.62755 85.12111 47.85613 0 At most 1 0.2557 24.87424 29.79707 0.1293 At most 2 0.103953 6.860256 15.49471 0.5257 At most 3 0.002697 0.164745 3.841466 0.6848 Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test (Maximum Eigenvalue) Hypothesized No. of CE(s) Eigenvalue Max-Eigen Statistic0.05 Critical Value Prob.** None * 0.62755 60.24687 27.58434 0 At most 1 0.2557 18.01399 21.13162 0.1293 At most 2 0.103953 6.695511 14.2646 0.5257 At most 3 0.002697 0.164745 3.841466 0.6848 Trace test indicates 1 cointegrating eqn(s) at the 0.05 level; *denotes rejection of the hypothesis at the 0.05 level; **MacKinnon-Haug-Michelis (1999) p-values. Table 4. Cointegration results (dependent variable–real money balances). Variable Cointegration Equation Y(–1) –0.9182 [–7.00446] TB(–1) –0.06088 [–3.81129] INF(–1) 0.117043 [6.97001] C 1.611207 MP = -1.611207 + 0.918y + 0.06tb - 0.117inf; These results yield an opti- mal inflation rate of (1/0.117 - 0.92*0.03) = 9.14% inflation as an explanatory variable. Thus, the regression equation is estimated as a second-degree polynomial. This is a widely used technique for estimating non-linear relationships by allowing for changes in slopes as a func- tion of changes in the independent variable [27,28,45]. The squared inflation term is therefore used due to the threshold effects. Hence, the slope of the estimated equa- tion can vary with changes in the inflation rate. This en- ables us to observe the turning point in the relationship between inflation and growth. The empirical model is specified as: Real GDP Growth = β0 + β1(real balances) + β2(Exports/ GDP) + β3(Deficit/GDP) + β4(Private Investment/GDP) + β5(Inflation) + β6(Human Capital) + β7(Inflation)2 β8 (Dummies) + ei Three period dummies were introduced (1983-92; 1993-2000; and 2001-2006). These three periods mark important economic regimes in Ghana. The list of vari- ables and their definitions are provided in Appendix (Ta- ble 5). Annual data from 1970-2006 were used and the results are reported below. Both the ADF and the Phillips Peron test confirm the existence of unit root in the vari- ables. The I(1) variables were therefore differenced to make them stationary and the results are presented in Table 6 and 7. The long run equation (equation 10) was estimated using Johansen cointegration method and the results in- dicate that there is one cointegrating vector and this is confirmed by both the trace statistics and the Eigenval- ues (Table 8). Subsequently, we test restrictions such as unit elasticity. The vector error correction estimates of the inflation growth relationship are presented in Table 6. T abl e 5. Definition of vari ables. Variable Definition Rgdpg Real GDP Growth m/p Real Balances Deft Budget Deficit as a proportion of GDP Lexpt Exports as a proportion of GDP Pvtinv Private Investment as a share of GDP Infl Inflation Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME 190 Table 6. Results of the unit root tests. Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) Test Phillips Perron (PP) Test VARIABLE Constant No Trend Constant Trend Constant No Trend Constant Trend Rgdpg –1.826258 –1.687995 –3.774095 –2.410277 m/p 0.249605 –1.916955 0.852840 –2.979962 Deft –2.234099 –2.899822 –2.234099 –2.948491 Lexpt –2.010599 –1.842804 –1.864397 –1.842804 Pvtinv –0.966095 –3.007251 –0.694917 –2.779045 Infl –2.183748 –2.559441 –2.425247 –2.56546 Test critical values: 1% level –3.540198 1% level –4.100935 5% level –2.909206 5% level –3.478305 10% level –2.592215 10% level –3.166788 Table 7. Results of the unit root tests (first difference). Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) Test Phillips Perron (PP) Test VARIABLE Constant No Trend Constant Trend Constant No Trend Constant Trend dRgdpg –3.155835 –3.30395 –16.02544** –15.64752** dm/p –10.056064** –10.090342** –11.35171** –11.92295** dDeft –6.319811** –6.243196** –6.7806** –6.653737** dlexpt –7.062333** –7.281371** –7.083831** –7.649226** dPvtinv –7.677549** –6.478208** –8.439228** –16.62738** dinfl –3.911792** –6.275686** –4.376691** –4.344887** Test critical values: 1% level –4.110440 1% level –4.10320 5% level –3.482763 5% level –3.47937 10% level –3.169372 10% level –3.16740 GDP growth is negatively affected by inflation with a one year lag. Private Investment has significantly posi- tive effect on GDP growth. These findings corroborate the work of [2,24]. From Table 9, the error correction term or the speed of adjustment carries the right sign (negative) and it is significant. The three period dummies were insignificant except for the period 1983-1992 which was weakly significant. From Table 5, the turning point for the inflation-growth relationship is calculated as follows: Turning Point = -(Inflation Coefficient)/2*Inflation Squared Coefficient). For the long run model, the turning point or growth maximizing rate of inflation is 22.2% while for the short run model, the growth maximizing rate of inflation is 29.4%. From the above, it can be con- cluded that the revenue ma imizing rate of inflation x  P. QUARTEY ET AL. 191 Table 8. Cointegrati o n tests. Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test (Trace) Hypothesized No. of CE( s) Eigenvalue Trace Statistic 0.05 Critical Value Prob.** None * 0.852706 132.8203 95.75366 0.0003 At most 1 0.530721 65.78386 69.81889 0.1006 At most 2 0.404756 39.30433 47.85613 0.2484 At most 3 0.269686 21.14692 29.79707 0.3486 At most 4 0.248448 10.14711 15.49471 0.2696 Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test (Maximum Eigenvalue) Hypothesized No. of CE(s) Eigenvalue Max-Eigen Statistic0.05 Cri tical Value Prob.** None * 0.852706 67.03642 40.07757 0.2923 At most 1 0.530721 26.47953 33.87687 0.4821 At most 2 0.404756 18.15742 27.58434 0.6474 At most 3 0.269686 10.99981 21.13162 0.2121 At most 4 0.248448 9.996537 14.2646 0.2923 Trace test indicates 1 cointegrating eqn(s) at the 0.05 level; *denotes rejection of the hypothesis at the 0.05 level; **MacKinnon-Haug-Michelis (1999) p-values. (9.14%) is not growth maximizing but rather, the growth maximizing rate of inflation is 22.2%. Thus, any infla- tion rate above 22.2% will lead to moderate gains in GDP growth. This corroborates the work of [45-48] who found that for middle income countries, the inflation threshold is 14-16 percent while for low income coun- tries a range of 15-23 percent was obtained. For the en- tire sample they consistently found that higher inflation is associated with moderate gains in GDP growth up to 15-18 percent inflation threshold. 5. Conclusions and Policy Implications The study investigates two key issues, namely, 1) ascer- tain the revenue maximizing rate of inflation for Ghana 2) Investigate whether the revenue maximizing rate of in- flation is also growth maximizing. The analysis involved estimating the revenue maximizing and growth maxi- mizing rate of inflation. Thus, The Johansen cointegra- tion approach was also used to analyze the effect of in- flation on long term growth and found that inflation negatively impacts on growth. The study found that the economy had recorded very high inflation rates during the pre-reform era and in 1982, it was as high as 122.2%. However, after the reforms, inflation rates have been lower and close to single digit. Interestingly, the periods of high inflation were associ- ated with lower growth rates (sometimes negative). GDP growth rates have been positive since 1984 averaging 4.4% in 1995-99 and rising to 5.1% in 2000-2006. Ex- cessively high rates of inflation affect real sector activi- ties. The study found that the revenue maximizing rate of inflation was 9.14 over the period 1990-2006. Thus, the seignorage maximizing rate of inflation is below the in- flation, indicating that the economy was operating on the wrong side of the laffer curve. However, the revenue maximizing inflation rate is not necessarily a growth maximizing one. The growth maximizing rate of infla- tion is 22.2%, thus corroborating observed historical trends in growth and inflation rates in Ghana. Prior to the economic reforms, Ghana had recorded significantly high rates of inflation above the threshold and low (or sometimes negative) growth rates. However, it recorded significantly positive and high growth rates and low in- flation during the post reform era. In conclusion, price stability has led to higher growth rates and the Ghanaian economy has operated below the growth maximizing rate of inflation in recent times. It is also obvious, that the growth maximizing rate of infla- tion is not a single digit. Some level of inflation is cer- tainly good for economic growth and job creation. The study suggests that the government should pursue the Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  192 P. QUARTEY ET AL. Table 9. Vector error correction estimates (Dependent variable–real GDP growth). Variable Cointegration EquationVariable Error Correction Cointegration Equation EXPT(–1) –0.107658 [–1.6902] D(EXPT(–1)) 0.440554 [1.66582] DEFT(–1) 0.261287 [1.85443] D(DEFT(–1)) –0.042573 [–0.10911] INFL(–1) –0.083947 [–1.85164] D(DINFL(–1)) –0.037792 [–0.33322] PVTINV(–1) –0.32954 [–1.97759] D(PVTINV(–1)) –0.671995 [–1.56096] INFL SQD (–1) 0.001429 [3.85709] D(INFL SQD (–1)) 0.000851 [1.09857] C 1.361557 C –0.850047 [–0.52506] Dum1 3.494951 [1.45799] Dum2 0.00236 [0.00094] Dum3 1.362836 [0.47463] EC Term –0.51846 [–1.72435] R-Squared 0.50473 Adj. R-Squared 0.298367 Sum sq. resids 617.6098 S.E Equation 5.072844 F-statistic 2.445838 Log likelihood –99.89675 Akaike AIC 6.336957 Schwarz SC 6.825781 Mean Dependent 0.011429 S.D Dependent 6.056148 Log Likelihood –750.2182 Akaike Information Criterion46.9839 Schwarz Criterion 50.18347 price stability policy but also be mindful of the trade-off between inflation and employment. Secondly, since the growth maximizing rate of inflation for Ghana is not a single digit, it is suggested that the government policy of achieving single digit inflation should be considered carefully taking into consideration inflation thresholds. 6. References [1] J. H. Boyd, R. E. Levine and B. D. Smith, “The Impact of Inflation on Financial Sector Performance,” Journal of Monetary Econo m i cs, Vol. 47, No. 2, 2001, pp. 221-248. [2] M. Mariotti, “An Examination of the Impact of Economic Policy on Long-Run Economic Growth: An Application of Vecm Structure to a Middle Income Context,” South African Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, No. 4, 2002, pp. 689-724. [3] M. S. Khan and A. S. Senhadji, “Threshold Effects in the Relationship between Inflation and Growth,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 48, No. 1, 2001, pp. 1-21 [4] K. Nell, “Is Low Inflation a Recondition for Faster Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  P. QUARTEY ET AL. 193 Growth? The Case of South Africa,” Working Paper No. 0011. Studies in Economics, University of Kent, Kent, UK, 2000. [5] Bank of Ghana, Statistical Bulletin, 2007. [6] N. K. Sowa and P. Abradu-Otoo, “Inflation Management in Ghana—The Output Factor,” Paper presented at the Bank of England/Cornell University Workshop on New Developments in Monetary Policy in Emerging Econo- mies, London, 17-18 July 2007. [7] J. Ammer and R. T. Freeman, “Inflation Targeting in the 1990s: The Experience of New Zealand, Canada and the UK,” Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 47, 1995, pp. 165-192. [8] N. Apergis, S. Miller, A. Panethimitakis and A. Vamva- kidis, “Inflation Targeting and Output Growth: Evidence from the European Union,” IMF Working Paper WP/05/89, Washington DC, 2005. [9] P. Arestis, G. M. Corporale and A. Cipollini, “Does In- flation Targeting Affect the Trade-Off Between Output Gap and Inflation Variability,” Manchester School, Vol. 70, No. 4, 2002, pp. 528-545. [10] S. Fischer, “Maintaining Price Stability,” Finance and Development, Vol. 33, No. 4. 1996, pp. 34-37. [11] P. Quartey, “Finance and SME Development in Ghana,” Journal of African Business, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2003, pp. 37-55. [12] V. Gockal and S. Hanif, “Relationship between Inflation and Economic Growth,” Working Paper No. WP2004/04. Reserve Bank of Fiji, Fiji, 2004. [13] ISSER State of Ghanaian Economy Report 2006, Univer- sity of Ghana. [14] J. Tobin, “Money and Economic Growth,” Econometrica, Vol. 33, No. 4, 1965, pp. 671-684 [15] M. Sidrauski, “Rational Choice and Patterns of Growth in a Monetary Economy,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 57, No. 2, 1967, pp. 534-544. [16] A. C. Stockman, “Anticipated Inflation and the Capital Stock in a Cash-in-Advance Economy,” Journal of Mon- etary Economics , Vol. 8, No. 3, 1981, pp. 387-393. [17] S. Fischer, “The Role of Macroeconomic Factors in Growth,” NBER Working Paper No. 4565, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 1993. [18] P. L. Rousseau and P. Wachtel, “Inflation, Financial De- velopment and Growth,” 2000. http://www.ssrn.com/ab- stract=251589 [19] M. Gillman and K. Michal, “Modelling the Effect of In- flation: Growth, Levels, and Tobin,” In: D. K. Levine, W. Zame, L. Ausubel, P.-A Chiappori, B. Ellickson, A. Ru- binstein and L. Samuelson, Eds., Proceedings of the 2002 North American Summer Meetings of the Econometric Society: Money, 2002. http://www.dklevine.Com/ pro- ceedings/money.htm [20] R. J. Barro, “Inflation and Economic Growth,” NBER Working Paper No. 5326, Cambridge, USA, 1995. [21] M. Bruno and W. Easterly, “Inflation Crisis and Long-Run Growth,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 41, No. 1, 1998, pp. 3-26. [22] F. Breuss, “Was ECB’s Monetary Policy Optimal?” At- lantic Economic Journal, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2002, pp. 298-321. [23] S. Cocchetti and M. Ehrmann, “Does inflation increase output volatility? An international comparison of policy- makers’ preferences and outcomes,” Working Paper No. 69, Central Bank of Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2000. [24] D. Hodge, “Inflation and Growth in South Africa,” Cam- bridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2006, pp. 163-180. [25] G. A. Akerlof, W. Dickens and G. Perry, “The Macro- economics of Low Inflation,” Brookings Papers on Eco- nomic Activity, 1996, Vol. 1, pp. 1-59. [26] G. A. Akerlof, W. Dickens and G. Perry, “Near-Rational Wage and Price Setting and the Long-Run Phillips Curve,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2000, Vol. 1, pp. 1-60. [27] N. K. Sowa, “Fiscal Deficits, Output and Inflation Tar- gets in Ghana,” World Development, Vol. 22, No. 8, 1994, pp. 1105-1117. [28] C. Adam, B. Ndulu and N. K. Sowa, “Liberalization, Seignorage Revenue in Kenya, Ghana and Tanzania,” Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 34, No. 4, 1996, pp. 531-553. [29] J. H. Boyd, R. E. Levine and B. D. Smith, “Capital Mar- ket Imperfections in a Monetary Growth Model,” Eco- nomic Theory, Vol. 11, No. 2, 1998, pp. 241-273 [30] E. Huybens and B. Smith, “Inflation, Financial Markets and Long-Run Real Activity,” Journal of Monetary Eco- nomics, Vol. 43, No. 2, 1998, pp. 283-315. [31] S. Choi, B. Smith and J. H. Boyd, “Inflation, Financial Markets and Capital Formation,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Vol. 78, 1996, pp. 41-58. [32] J. H. Boyd and B. Champ, “Inflation, Banking and Eco- nomic Growth,” Economic Commentary, Ohio, USA: Federal Bank of Cleveland, 2006. [33] R. G. King and R. Levine, “Finance, Entrepreneurship and Growth: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 32, No. 3, 1993, pp. 513-542. [34] R. Levine and S. Zervos, “Stock Markets, Banks and Economic Growth,” American Economic Review, Vol. 88, No. 3, 1998, pp. 537-558. [35] Z. Xu, “Financial Development, Investment and Eco- nomic Growth,” Economic Inquiry, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2000, pp. 331-344. [36] M. Li, “Inflation and Economic Growth: Threshold Ef- fects and Transmission Mechanisms,” CEA Working Pa- per 0176, Department of Economics, University of Al- berta, Canada, 2006. [37] E. Huybens and B. Smith, “Financial Market Frictions, Monetary Policy and Capital Accumulation in a Small Open Economy,” Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 81, No. 2, 1999, pp. 353-400. [38] G. Khan and K. Parish, “Conducting Monetary Policy with Inflation Targets,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ME 194 City Economic Review, Vol. 83, 1998, pp. 5-32. [39] M. King, 1997. “Changes in UK Monetary Policy: Rules and Discretion in Practice,” Journal of Monetary Eco- nomics, Vol. 39, No. 1, 1997, pp. 81-97. [40] F. S. Mishkin and A. S. Posen, “Inflation Targeting: Les- sons from Four African Countries,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, Vol. 3, No. 3, 1997, pp. 9-11 [41] S. Fischer, “Relative Price Variability and Inflation in the United States and Germany,” European Economic Re- view, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1982, pp. 171-196. [42] P. Cagan, “The Monetary Dynamics of Hyper Inflation,” In: M. Freedman, Ed., Studies in Quantity Theory of Money, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1956, pp. 25-117. [43] S. Johansen, “Statistical Analysis of Cointegrating Vec- tors”. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 12, No. 2-3, 1988, pp. 231-254. [44] S. Johansen,“Domestic and Foreign Effects on Prices in an Open Economy: The Case of Denmark,” Journal of Policy Modelling, Vol. 14, No. 4, 1992, pp. 401-428. [45] R. Pollin and A. Zhu 2005. “Inflation and economic growth: A cross-country non-linear analysis,” Working Paper Number 109, Political Economy Research Institute Massachusetts, USA. [46] L. E. O. Svensson, “Optimal Inflation Targets, Conserva- tive Central Banks and Linear Inflation Contracts,” American Economic Review, Vol. 87, No. 1, 1997, pp. 98-114. [47] L. E. O. Svensson, “How Should Monetary Policy Be Conducted in an Era of Price Stability? A Symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,” New Challenges for Monetary Policy, 1999a, pp. 195-259. [48] L. E. O. Svensson, “Inflation Targeting as a Monetary Policy Rule,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 43, No. 3, 1999b, pp. 607-654. |