Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

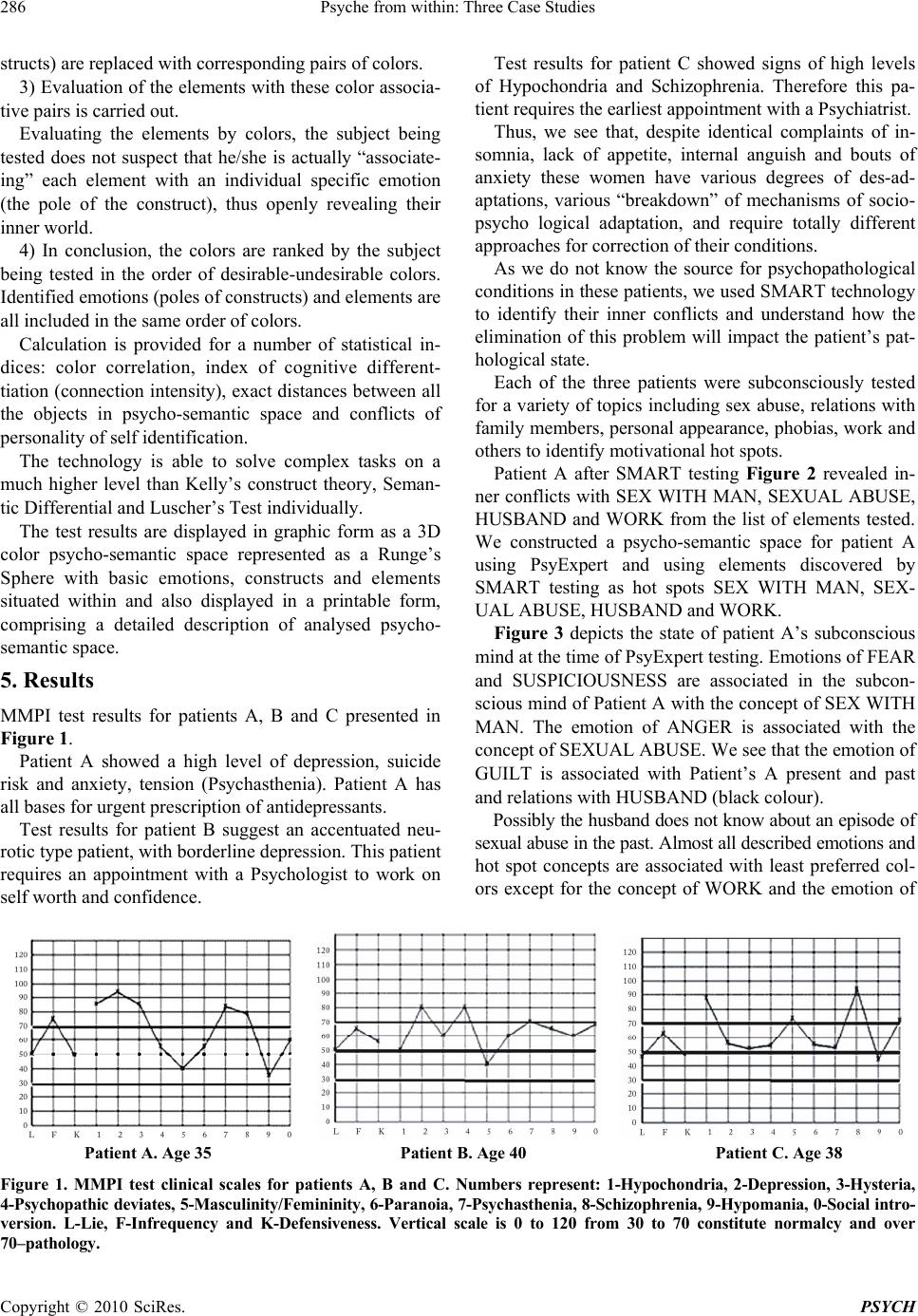

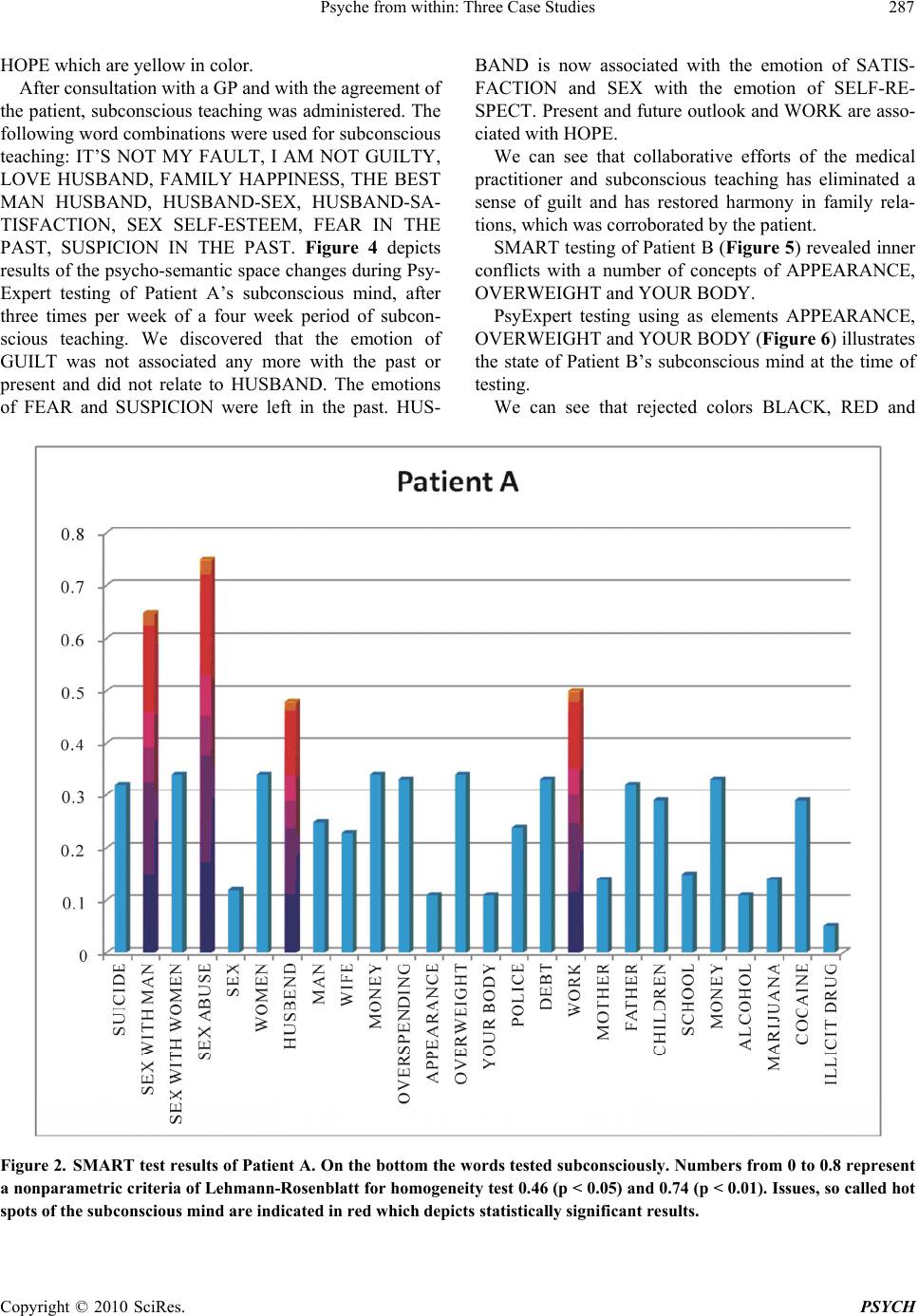

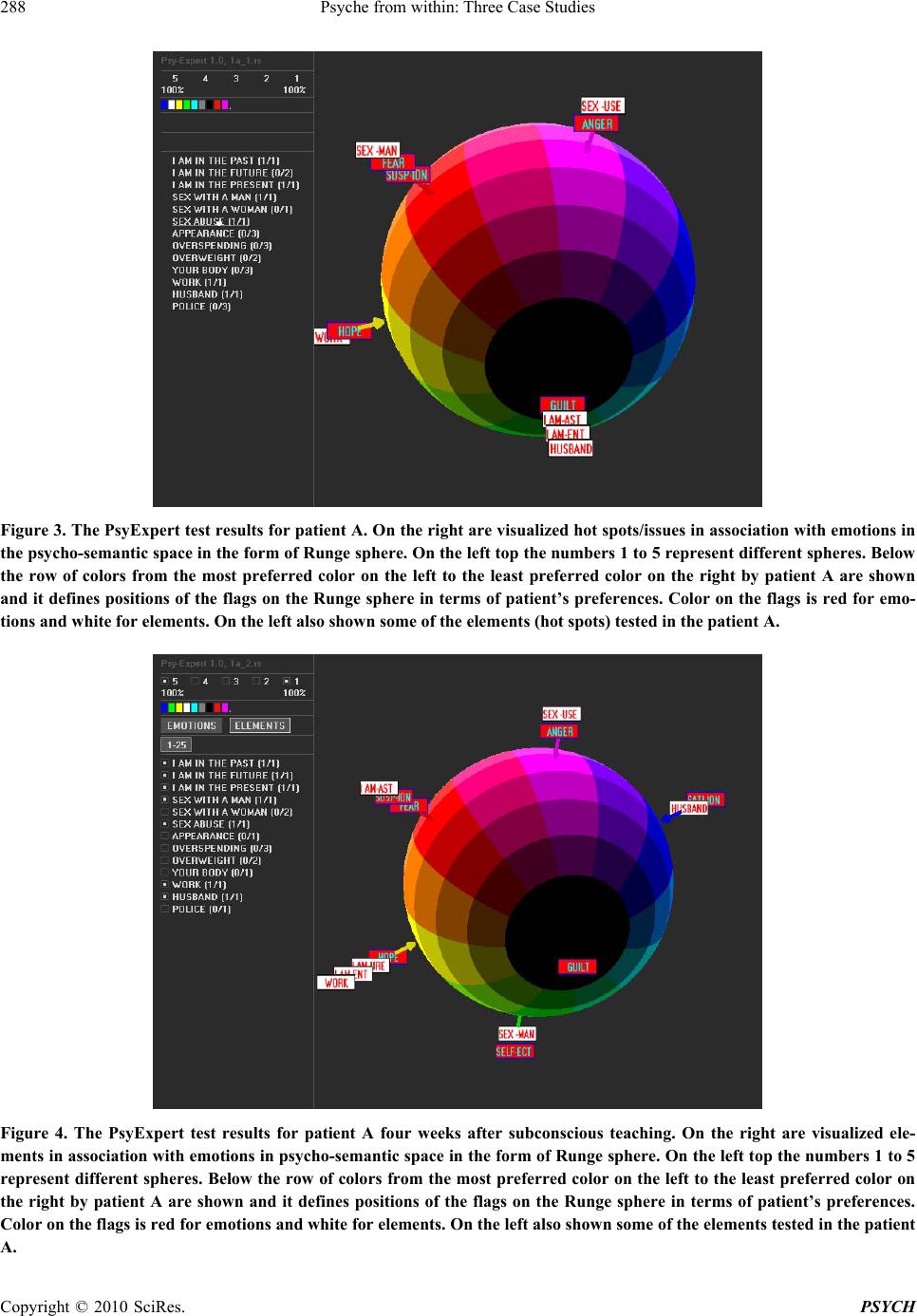

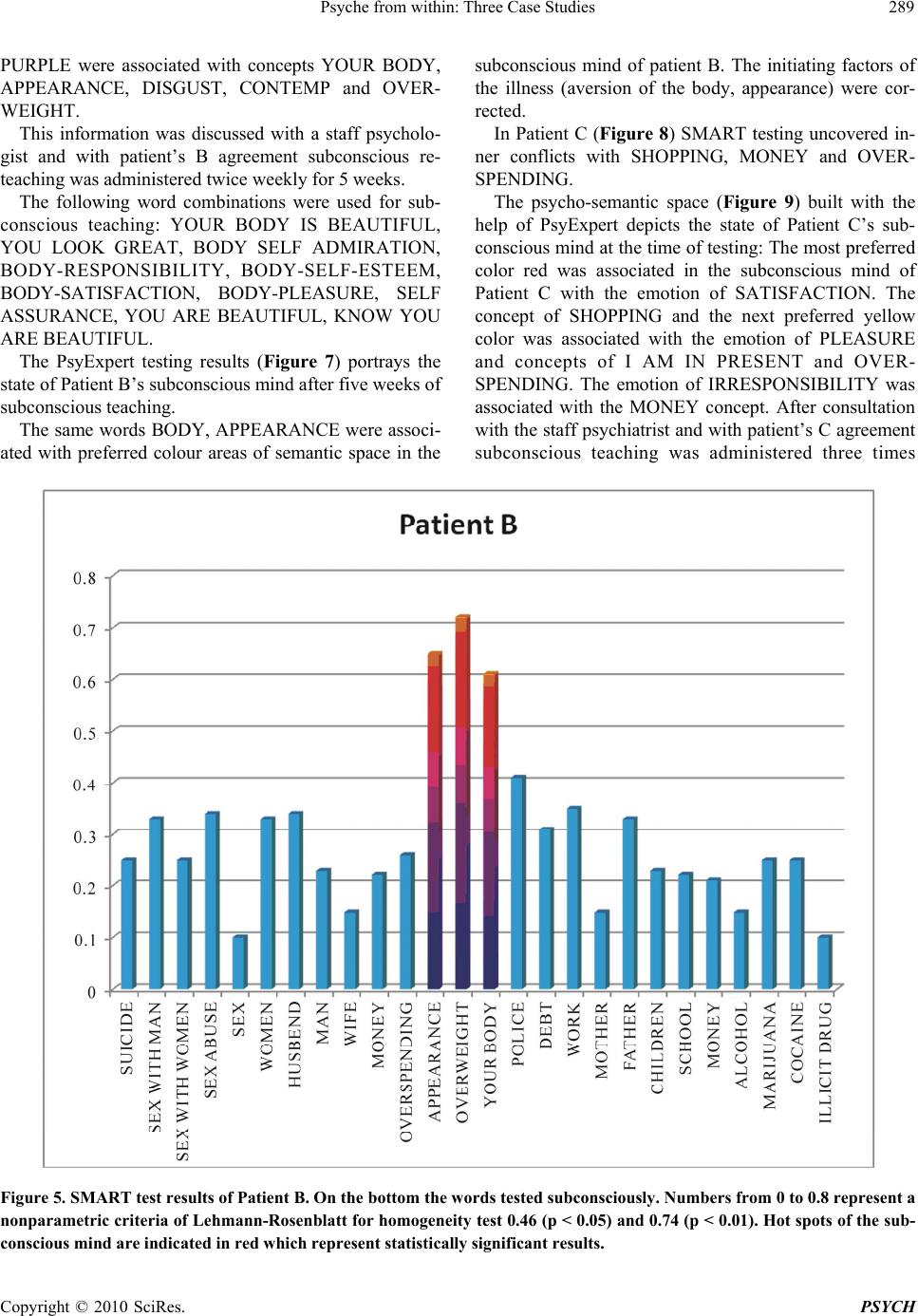

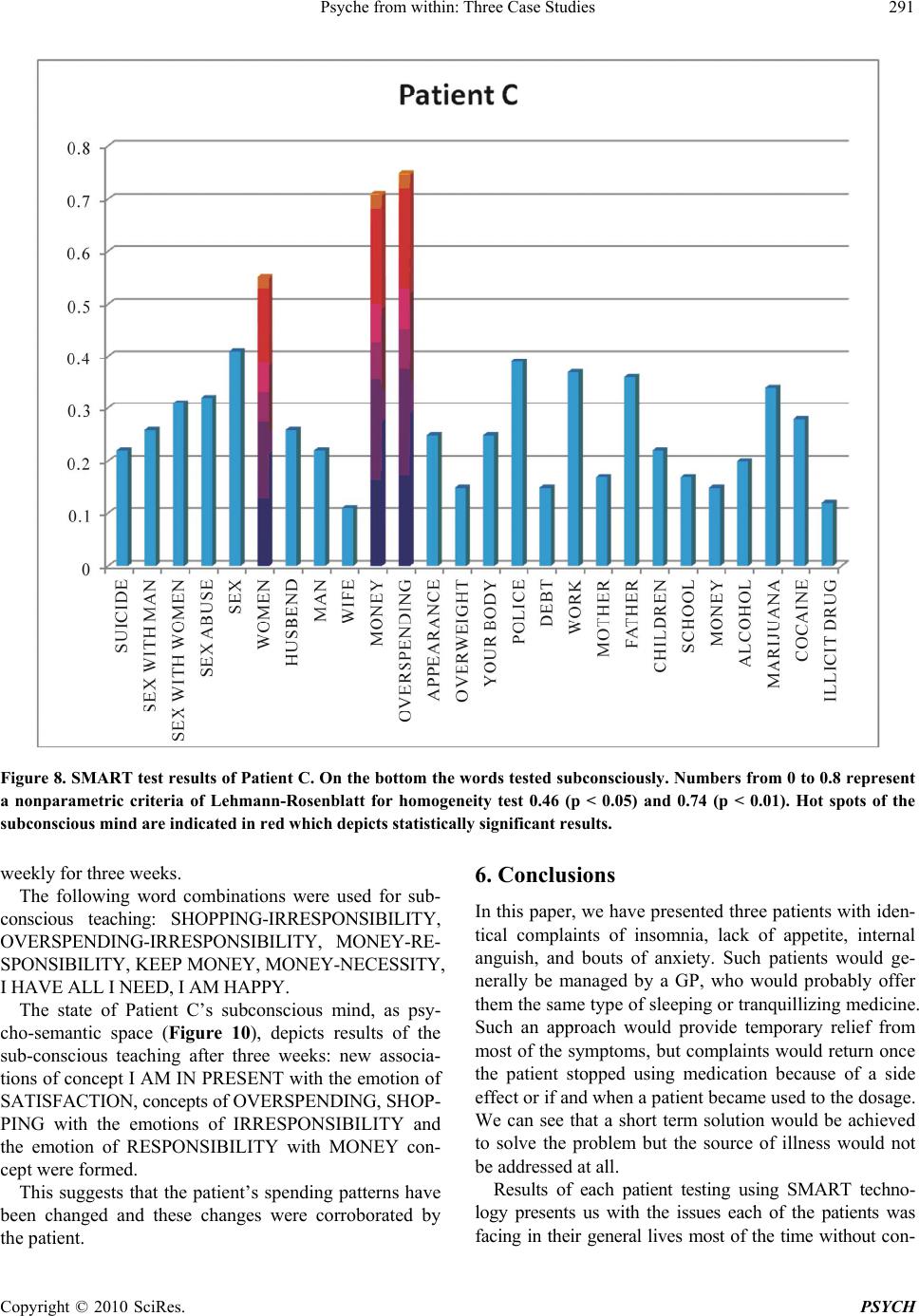

Psychology, 2010, 1, 282-294 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.14037 Published Online October 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Semyon Ioffe, Sergey Yesin Northam Psychotechnologies, 2446 Bank St. Suite 632Ottawa ON K1V 1A8, Canada. Email: sioffe@primus.ca Received February 26th, 2010; revised April 12th, 2010; accepted August 4th, 2010. ABSTRACT A comparative look at the psychological health and the physical health industries uncovers the need for measurable quantitative testing in order to bring the psychological health field into the 21st century. We are using a proven set of subconscious mind testing technologies which revolutionize the quality of services and results in the field of psycho- logical health. These technologies decrease the cost and increa se the accurac y and effectiveness of psychological help. We look at three patient case stu dies to demonstrate the effectiveness o f this new approach and familiarize psychologi- cal health practitioners and their patients with these technologies. Keywords: Quantitative Analysis, Human Behaviour, Psycho-Semantics, Subconscious Teaching 1. Introduction 1.1.Health Issues We all can agree that when we go for a yearly check up to the family doctor we expect some tests to be done de- pending on our age and health history, which might in- clude blood pressure measurements, blood tests, possibly a cardiogram and others. But, when we have some parti- cular health issues, there are numerous tests which can pinpoint specific areas of concern to help a doctor make a correct diagnosis and follow up with successful treat- ment. Would you be surprised if your doctor, without per- forming any tests in spite of your symptoms, made a con- clusion that you are healthy? Or, what if the doctor, without any complaint from you, made a conclusion that you are gravely ill and started prescribing some medicine or schedule of treatment for urgent intervention. You probably would be shocked and you would look for a second opinion before starting the treatment prescribed. What about psychological problems and issues? Shouldn’t we expect the same approach when we have psychologi- cal problems, even such as poor appetite, bad sleeping patterns, continuous worries etc? Shouldn’t we expect to have a number of psychological tests to help medical and psychological practitioners to pinpoint or qualify psy- chological health issues and allow for follow up of suc- cessful treatment? Of course we should, but unfortunately such a unifying approach in psychological health is not in existence yet. The bottom line is the health industry has ways of test- ing patients to determine an accurate course of treat- ment and has the tools to measure the effectiveness of treatment along the way. These tests also help the patient see their progress and keep them committed to the pro- cess. Until today, the field of psychology did not have such testing. Both patients and doctors rely on a patient’s personal opinion and communication and due to the com- plex nature of the disorders, we continue to have high rates of inaccurate diagnosis, treatment, prescription and disillusioned patients dropping out of treatment. Statistics for patients’ dropout rates from treatments varies greatly in literature, from as low as 16% to as high as 70% (http://www.gopubmed.org/web/gopubmed/statistics/mes h/10352). Psychological problems indirectly affect all people through issues with a family member, friend or colleague. Twenty percent of people will personally experience a psychological problem during their lifetime. Psychologi- cal problems affect people of all ages, educational and income levels and cultures. The onset of most psycho- logical problems occurs during adolescence and young adulthood. A complex interplay of genetic, biological, personality and environmental factors cause psychologi- cal problems. Making the correct diagnosis and tailoring effective treatment to the individual's needs are essential compo- nents of an overall psychological management plan.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 283 For most people in the world, the primary care physi- cian is their first and often only contact with the psycho- logical care system. Under-diagnosis, misdiagnosis and under-treatment of psychological problems can result in poor outcomes. The waiting time for appointments with a psychiatrist is between 3 to 12 months. Most of the psychologists are working outside the primary public health system and statistical data are mostly unavailable. As the current primary health gatekeepers to the public system, physic- cians deal with a host of psychological conditions. According to some estimates, 60% of the conditions presented to primary care physicians are psychological, have a psychological component, or are highly influenced by psychological factors. In addition, although about 40% of high-end primary care users suffer from some form of depression, well over half of these individuals receive no treatment for their condition. As a society, we should invest more in front-end psy- chological health services aimed at reducing the demand for psychological illness care services at the back end. As the first line of contact, primary psychological care units with the testing expertise and coordinating capacity to refer individuals quickly and effectively, rather than GP or acute care hospitals, should be the central focus of the psychological health care system. 2.Methods of Testing in Psychology Psychological measurements of personality are often de- scribed as objective tests, projective tests and psycho- semantic tests. 2.1. Objective Tests Objective tests have a restricted response format, such as allowing for true or false answers or rating using an or- dinal scale. Prominent examples of objective personality tests include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality In- ventory, Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III [1], Child Behavior Checklist [2] and the Beck Depression Inventory [3]. Objective personality tests for recruiting potential busi- ness employees, such as the NEO-PI, the 16PF, and the Occupational Personality questionnaire are all based on the Big Five taxonomy. The Big Five, or Five Factor Model of normal personality, has gained acceptance since the early 1990s when some influential meta-analyses e.g., Barrick & Mount [4] found consistent relationships be- tween the Big Five personality factors and important cri- terion variables. 2.2. Projective Tests Projective tests allow for a freer type of response. An example of this would be the Rorschach test, in which a person states what each of ten ink blots might be. As improved sampling and statistical methods deve- loped, much controversy regarding the utility and validity of projective testing has occurred. The use of clinical judgement rather than norms and statistics to evaluate people’s characteristics has convinced many that project- tive tests are deficient and unreliable (results are too dis- similar each time a test is given to the same person). However, many practitioners continue to rely on project- tive testing, and some testing experts e.g., Cohen [5] sug- gest that these measures can be useful in developing therapeutic rapport. They may also be useful in creating inferences to follow-up with other methods. Possibly they have lingered in usage because they have a mystical and fascinating reputation, and are more attractive to unin- formed people than answering objective tests, e.g., true/false questionnaires. The most widely used scoring system for the Rorschach is the Exner system of scoring [6]. Another common projective test is the Thematic Ap- perception Test (TAT) [7], which is often scored with Western’s Social Cognition and Object Relations Scales [8]. Both “rating scale” and “free response” measures are used in contemporary clinical practice, with a trend to- ward the former. Other projective tests include the House-Tree-Person Test, Robert’s Apperception Test, and the Attachment Projective. In a national survey in the U.S., the Rorschach was ranked eighth among psychological tests used in outpa- tient mental health facilities Meloy, J. Reid, Gacano [9]. Psycho-diagnostic methods described above, objective and projective, have a number of serious deficiencies. For example, objective, direct methods of psycho-diagnostics based on the self-report, reveal only consciously realised and not actually operating motives. Even adequately re- alised motives can be distorted during testing because of their various social desirabilities and therefore socially undesirable motives are masked and socially desirable motives are demonstrated. Other groups of tests—pro- jective, do not allow evaluation of precise quantitative changes during the course of treatment. The quality of the conclusion under the projective test highly depends on the level of preparation and professionalism of the psy- chologist who is carrying out the test. These traditional investigational methods of observing the human psyche, including the active methods of pres- entation of various test problems, the analysis of the dy- namics of learning, and questioner data collection are insufficient because between the researcher and the psy- che of the subject being tested is the conscious mind, which mediates all actions and processing of information and modifies all reactions.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 284 3. Psycho-semantic Tests Psycho-semantic methods are free of the above described defects. The psycho-semantic approach allows the re- searcher to gain access to knowledge of how people think which is not always available to the people themselves. In psycho-semantics, the task for the individual is to pro- vide some classification about a topic. The response could be a judgment of similarity, an indication of the extent to which she or he agrees or disagrees with a state- ment, or some other association. There are many different types of responses that are possible with this technique. On the basis of numerous responses to a range of stimuli, a matrix of data is obtained from each subject. The matrix can then be used with any analytic technique that is based on matrix algebra. These include a variety of well-known multidimensional procedures such as factor analysis, cluster analysis, latent variable modeling, and many oth- ers. As a result, the researcher can find “bundles” of in- terconnected meaning that form the coordinate axes of semantic space. The number of independent factors that emerge from an analysis defines the number of dimen- sions that are used to locate meanings in semantic space. According to these geometric models of the mind, the greater the number of independent factors that emerge from an analysis, the greater the cognitive complexity of the individual, group or social consciousness Osgood, Succi, & Tannenbaum [10], Osgood [11-13], Kelly [14], Leontiev [15]. Psycho-semantics, in a very simplistic way, is a link between words and feelings. The psycho-semantic approach uses a hypothesis that human psyche and a person’s previous experiences are organized by semantic principle and the humans are the product of information of their surrounding environment. Any traits, influences, abilities, etc. are described and ex- perienced through words, pictures, sounds etc. Informa- tion is categorized and prioritized by emotions through- out one’s life. The major content of the human’s informa- tional being is not accessible to his/her conscious mind, it belongs to the subconscious mind [16]. Defining the re- quirements and developing the stimuli for the practical part of this article requires us to address the analysis of the psychological structure of a word-stimulus in forms that comprise an element of psycho-semantic spheres and its logical or semantic structure as organization that repre- sents meaning. 3.1. Different Psycho-semantic Approaches Is it possible to have a detailed and scientifically proven approach to the psychological research of psychoseman- tic spheres that will show which real connections were stimulated by a word and, if possible, to analyze the de- gree of probability of occurrence of these connections and degrees of affinity in which the separate components of this semantic system exists? In addition, are there any methods of objectively studying these semantic fields and their various incoming components? Attempts to solve these problems have been repeatedly undertaken in psychology by Deese [17-20], Dixon [21, 22], Kelly [14], Noble [23], Osgood [10-13,24-28], Shevrin [29,30], Kostandov [31-33], Luriya [34], Smir- nov, Beznosjuk, Zhuravlyov [16]. There have been some experimental attempts to define subjective semantic fields and connections (inside of them) using methods of associative experiment by Deese [17] and a conditional reflex Luriya & Vinogradova [35]. Initial premises were developed to study psyche processes that presumed to obtain the information of its semantic elements without traditional division into motivational, will and cognitive spheres. The foundation of such an approach was origi- nated by Vygotsky [36]. The overwhelming majority of the methods of studying the psyche have not represented physical measurements. They neither maintained metrological requirements nor applied them consistently in experiments. We require psychological methods which allow us to use not only theoretical but also practical applications to learn mental functions without the influence of the con- scious mind of the participant being tested. The work of Shevrin [29], Shevrin, Bond, Brakel, Hertel and Williams [30], Kostandov [31] and Dixon [22] include methods of subconscious presentation of the testing information. On the basis of these works, the conceptual models were constructed that are competing with traditional psycho- analytic postulates in their efficiency of the practical ap- plications by Beznosjuk & Smirnov [37] and Smirnov, Beznosjuk & Zhuravlyov [16]. Applied on a subconscious level, psycho-semantic methods provide diagnostically significant structurally quantitative information for the organization of individ- ual systems of values and attitudes [16,38,39]. In sub- consciously applied psycho-semantic procedures, the statistics are collected not within the limits of groups of examinees but within the limits of repeating probes dur- ing testing procedures in a single examinee. The subconsciously applied psycho-semantic method appears indirectly, presented to the examinee in the form of a “verbal game,” appealing, seemingly, only to lin- guistic competence. These methods actually open the subjective content of language symbols that is embodied in the structural formation work of real motives and goals of the subject [16,38-40]. 4. Materials and Methods Out of a wide variety of patients coming into the outpa-  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 285 tient clinic of the Vishnevsky Central Military Clinical Hospital, we have chosen three women (A, B and C) ages 35, 40 and 38 with identical complaints of insomnia, lack of appetite, internal anguish, bouts of anxiety. They were subjected to the following testing procedures: 1) MMPI—to identify if the patients have psycho- pathological conditions, 2) SMART—to identify motivational hot spots, 3) PsyExpert—to uncover how motivational hot spots associate with patients’ emotions in their subconscious mind and 4) SMART—to propose how subconscious teaching can help the patient to restore the harmony of the patients inner world. MMPI—Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory is one of the most widely used personality tests in mental health, based on the questionnaire performed on the computer screen. MMPI is an objective test and in our case studies used to identify normalcy or psychopatho- logical conditions. SMART—Semantically Mediated Analysis of Re- sponses and Teaching technology is based on the univer- sal principles of human behaviour and scientific experi- mentation. Humans are the product of information of their surrounding environment. Any traits, influences, abilities, etc are described and experienced through words, pictures, sounds etc. Information is categorized and pri- oritized by emotions throughout one’s life. The major content of the human’s informational being is not acces- sible to his/her conscious mind. It belongs to the subcon- scious mind. SMART technology uses the universal principles of scientific experimentation. Each experiment consists of: Controls, Probes, Repers (Reference point) and Regis- tered responses [16,38,39]. Each person is his own control, since every person’s psyche is different. It is important to understand that every individual test is a complete scientific experiment since it contains all the above-mentioned components. Controls represent stimuli which have no meaning to the subject. They are in the form of a row of randomly- chosen 15 numbers that flash across the screen at a frac- tion of a second, registering through the retina into the brain. This control is then masked by a different row of randomly-chosen 15 numbers. The first row, the control, is seen subconsciously. The second row, the masker, is seen consciously. The probes are semantically meaningful stimuli in the form of a word that moves across the screen at a fraction of a second, registering through the retina into the brain. This probe/word is then masked by a row of ran- domly-chosen 15 numbers. The probe/word is seen sub- consciously and the masker row of numbers is seen con- sciously. Reper is a different kind of control. It is a measurement developed to gauge defence reaction (the subject’s reac- tion to the “punishment” they receive during the test). This reaction is then measured to understand how the subject’s subconscious mind responds defensively. Registered Response is the subject being asked to press a mouse button each time they see a row of numbers. The combined visual and motor reaction to the controls, probe and reper are measured by the response time between a stimuli and the subject pressing the mouse button. Rigid requirements are placed on the respondent en- suring that they are unable to alter the test results in any way. The speed at which they react is measured. Statisti- cal analysis of the relationship between the control, probe and reper is performed using the criteria of Lehmann- Rosenblatt. The Universal Color-Associative Complex PSY-EX- PERT is a unique psycho-diagnostic tool for creating an individual psycho-semantic space, its visualization and detailed examination. It uncovers how motivetional hot spots associate with a patient’s emotions in their subcon- scious mind, defines an individual’s psycho-semantic space for follow up of subsequent subconscious reteach- ing and other psychological treatment. PSY-EXPERT technology, used in the study, encom- passes in itself all the best features of well known tests, such as the semantic differential [10,27], construct theory [14], “Max Luscher’s Test,” theory of the emotions [15] and others. The very heart of PSY-EXPERT is a concept of innate relations of human emotions and feelings with color. PSY-EXPERT uses classification of emotions by Leontiev [15]. The corner stone of this classification are eight basic emotions representing human personal needs. http://emoatlas.narod.ru/book1.html. The PSY-EXPERT test incorporates an equal number of basic emotions, connected with individual needs of the personality (posi- tive and negative, directed on itself or on the object, an- ticipating or ascertaining). 4.1. The PSY-EXPERT Test is Comprised of a Number of Steps 1) The subject being tested looks through a number of pictures illustrating various life situations, recognizes some as opposite pairs of emotions, names them and un- dersigns. It is natural that the emotions especially relevant to the subject being tested are “recognized” with ease. 2) The colors of a visible spectrum are shown one by one and the subject being tested is asked to select for each of the emotions (poles of the constructs) revealed in the previous step, the most “desirable” colors and evalu- ate their strength using a scale from 1 to 10 [10]. Consequently, pairs of opposite emotions (the con-  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 286 structs) are replaced with corresponding pairs of colors. 3) Evaluation of the elements with these color associa- tive pairs is carried out. Evaluating the elements by colors, the subject being tested does not suspect that he/she is actually “associate- ing” each element with an individual specific emotion (the pole of the construct), thus openly revealing their inner world. 4) In conclusion, the colors are ranked by the subject being tested in the order of desirable-undesirable colors. Identified emotions (poles of constructs) and elements are all included in the same order of colors. Calculation is provided for a number of statistical in- dices: color correlation, index of cognitive different- tiation (connection intensity), exact distances between all the objects in psycho-semantic space and conflicts of personality of self identification. The technology is able to solve complex tasks on a much higher level than Kelly’s construct theory, Seman- tic Differential and Luscher’s Test individually. The test results are displayed in graphic form as a 3D color psycho-semantic space represented as a Runge’s Sphere with basic emotions, constructs and elements situated within and also displayed in a printable form, comprising a detailed description of analysed psycho- semantic space. 5. Results MMPI test results for patients A, B and C presented in Figure 1. Patient A showed a high level of depression, suicide risk and anxiety, tension (Psychasthenia). Patient A has all bases for urgent prescription of antidepressants. Test results for patient B suggest an accentuated neu- rotic type patient, with borderline depression. This patient requires an appointment with a Psychologist to work on self worth and confidence. Test results for patient C showed signs of high levels of Hypochondria and Schizophrenia. Therefore this pa- tient requires the earliest appointment with a Psychiatrist. Thus, we see that, despite identical complaints of in- somnia, lack of appetite, internal anguish and bouts of anxiety these women have various degrees of des-ad- aptations, various “breakdown” of mechanisms of socio- psycho logical adaptation, and require totally different approaches for correction of their conditions. As we do not know the source for psychopathological conditions in these patients, we used SMART technology to identify their inner conflicts and understand how the elimination of this problem will impact the patient’s pat- hological state. Each of the three patients were subconsciously tested for a variety of topics including sex abuse, relations with family members, personal appearance, phobias, work and others to identify motivational hot spots. Patient A after SMART testing Figure 2 revealed in- ner conflicts with SEX WITH MAN, SEXUAL ABUSE, HUSBAND and WORK from the list of elements tested. We constructed a psycho-semantic space for patient A using PsyExpert and using elements discovered by SMART testing as hot spots SEX WITH MAN, SEX- UAL ABUSE, HUSBAND and WORK. Figure 3 depicts the state of patient A’s subconscious mind at the time of PsyExpert testing. Emotions of FEAR and SUSPICIOUSNESS are associated in the subcon- scious mind of Patient A with the concept of SEX WITH MAN. The emotion of ANGER is associated with the concept of SEXUAL ABUSE. We see that the emotion of GUILT is associated with Patient’s A present and past and relations with HUSBAND (black colour). Possibly the husband does not know about an episode of sexual abuse in the past. Almost all described emotions and hot spot concepts are associated with least preferred col- ors except for the concept of WORK and the emotion of Patient A. Age 35 Patient B. Age 40 Patient C. Age 38 Figure 1. MMPI test clinical scales for patients A, B and C. Numbers represent: 1-Hypochondria, 2-Depression, 3-Hysteria, 4-Psychopathic deviates, 5-Masculinity/Femininity, 6-Paranoia, 7-Psychastheni a, 8-Schizo phrenia, 9-Hypom ania, 0-Social intro- version. L-Lie, F-Infrequency and K-Defensiveness. Vertical scale is 0 to 120 from 30 to 70 constitute normalcy and over 70–pathology.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 287 HOPE which are yellow in color. After consultation with a GP and with the agreement of the patient, subconscious teaching was administered. The following word combinations were used for subconscious teaching: IT’S NOT MY FAULT, I AM NOT GUILTY, LOVE HUSBAND, FAMILY HAPPINESS, THE BEST MAN HUSBAND, HUSBAND-SEX, HUSBAND-SA- TISFACTION, SEX SELF-ESTEEM, FEAR IN THE PAST, SUSPICION IN THE PAST. Figure 4 depicts results of the psycho-semantic space changes during Psy- Expert testing of Patient A’s subconscious mind, after three times per week of a four week period of subcon- scious teaching. We discovered that the emotion of GUILT was not associated any more with the past or present and did not relate to HUSBAND. The emotions of FEAR and SUSPICION were left in the past. HUS- BAND is now associated with the emotion of SATIS- FACTION and SEX with the emotion of SELF-RE- SPECT. Present and future outlook and WORK are asso- ciated with HOPE. We can see that collaborative efforts of the medical practitioner and subconscious teaching has eliminated a sense of guilt and has restored harmony in family rela- tions, which was corroborated by the patient. SMART testing of Patient B (Figure 5) revealed inner conflicts with a number of concepts of APPEARANCE, OVERWEIGHT and YOUR BODY. PsyExpert testing using as elements APPEARANCE, OVERWEIGHT and YOUR BODY (Figure 6) illustrates the state of Patient B’s subconscious mind at the time of testing. We can see that rejected colors BLACK, RED and Figure 2.SMART test results of Patient A. On the bottom the words tested subconsciously. Numbers from 0 to 0.8 represent a nonparametric cri teria of Lehmann-Rosenbl att for homogeneity test 0.46 (p < 0.05) and 0.74 (p < 0.01). Issues, so called hot spots of the subconscious mind are indicated in red which depicts statistically significant results.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 288 Figure 3. The PsyExpert test results for patient A. On the right are visualized hot spots/issues in association with emotions in the psycho-semantic space in the form of Runge sphere. On the left top the numbers 1 to 5 represent different spheres. Below the row of colors from the most preferred color on the left to the least preferred color on the right by patient A are shown and it defines positions of the flags on the Runge sphere in terms of patient’s preferences. Color on the flags is red for emo- tions and white for elements. On the left also shown some of the elements (hot spots) tested in the patient A. Figure 4.The PsyExpert test results for patient A four weeks after subconscious teaching. On the right are visualized ele- ments in association with emotions in psycho-semantic space in the form of Runge sphere. On the left top the numbers 1 to 5 represent different spheres. Below the row of colors from the most preferred color on the left to the least preferred color on the right by patient A are shown and it defines positions of the flags on the Runge sphere in terms of patient’s preferences. Color on the flags is red for emotions and white for elements. On the left also shown some of the elements tested in the patient A.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 289 PURPLE were associated with concepts YOUR BODY, APPEARANCE, DISGUST, CONTEMP and OVER- WEIGHT. This information was discussed with a staff psycholo- gist and with patient’s B agreement subconscious re- teaching was administered twice weekly for 5 weeks. The following word combinations were used for sub- conscious teaching: YOUR BODY IS BEAUTIFUL, YOU LOOK GREAT, BODY SELF ADMIRATION, BODY-RESPONSIBILITY, BODY-SELF-ESTEEM, BODY-SATISFACTION, BODY-PLEASURE, SELF ASSURANCE, YOU ARE BEAUTIFUL, KNOW YOU ARE BEAUTIFUL. The PsyExpert testing results (Figure 7) portrays the state of Patient B’s subconscious mind after five weeks of subconscious teaching. The same words BODY, APPEARANCE were associ- ated with preferred colour areas of semantic space in the subconscious mind of patient B. The initiating factors of the illness (aversion of the body, appearance) were cor- rected. In Patient C (Figure 8) SMART testing uncovered in- ner conflicts with SHOPPING, MONEY and OVER- SPENDING. The psycho-semantic space (Figure 9) built with the help of PsyExpert depicts the state of Patient C’s sub- conscious mind at the time of testing: The most preferred color red was associated in the subconscious mind of Patient C with the emotion of SATISFACTION. The concept of SHOPPING and the next preferred yellow color was associated with the emotion of PLEASURE and concepts of I AM IN PRESENT and OVER- SPENDING. The emotion of IRRESPONSIBILITY was associated with the MONEY concept. After consultation with the staff psychiatrist and with patient’s C agreement subconscious teaching was administered three times Figure 5. SMART test results of Patient B. On the bottom the words tested subconsciously. Numbers from 0 to 0.8 represent a nonparametric crite ria of Lehmann-Rosenblatt for homogene ity test 0.46 (p < 0.05) and 0.74 (p < 0.01). Hot spots of the sub- conscious mind are indicated in red which represent statistically significant results.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 290 Figure 6. The PsyExpert test results for patient B. On the right are visualized hot spots in association with emotions in the psycho-semantic space in the form of Runge sphere. On the left top the numbers 1 to 5 represent different spheres. Below the row of colors from the most preferred color on the left to the least preferred color on the right by patient B are shown and it defines positions of the flags on the Runge sphere in terms of patient’s preferences. Color on the flags is red for emotions and white for elements. On the left are shown some of the basic patient B’s emotions. Figure 7. The PsyExpert test results for patient B five weeks after subconscious teaching. On the right are visualized elements in association with emotions in psycho-semantic space in the form of Runge sphere. On the left top the numbers 1 to 5 repre- sent different spheres. Below the row of colors from the most preferred color on the left to the least preferred color on the right by patient B are shown and it defines positions of the flags on the Runge sphere in terms of patient’s preferences. Color on the flags is red for emotions and white for elements. On the left are shown some of the basic patient B’s emotions.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 291 Figure 8. SMART test results of Patient C. On the bottom the words tested subconsciously. Numbers from 0 to 0.8 represent a nonparametric criteria of Lehmann-Rosenblatt for homogeneity test 0.46 (p < 0.05) and 0.74 (p < 0.01). Hot spots of the subconscious mind are indicated in red whic h depicts statistically significant results. weekly for three weeks. The following word combinations were used for sub- conscious teaching: SHOPPING-IRRESPONSIBILITY, OVERSPENDING-IRRESPONSIBILITY, MONEY-RE- SPONSIBILITY, KEEP MONEY, MONEY-NECESSITY, I HAVE ALL I NEED, I AM HAPPY. The state of Patient C’s subconscious mind, as psy- cho-semantic space (Figure 10), depicts results of the sub-conscious teaching after three weeks: new associa- tions of concept I AM IN PRESENT with the emotion of SATISFACTION, concepts of OVERSPENDING, SHOP- PING with the emotions of IRRESPONSIBILITY and the emotion of RESPONSIBILITY with MONEY con- cept were formed. This suggests that the patient’s spending patterns have been changed and these changes were corroborated by the patient. 6. Conclusions In this paper, we have presented three patients with iden- tical complaints of insomnia, lack of appetite, internal anguish, and bouts of anxiety. Such patients would ge- nerally be managed by a GP, who would probably offer them the same type of sleeping or tranquillizing medicine. Such an approach would provide temporary relief from most of the symptoms, but complaints would return once the patient stopped using medication because of a side effect or if and when a patient became used to the dosage. We can see that a short term solution would be achieved to solve the problem but the source of illness would not be addressed at all. Results of each patient testing using SMART techno- logy presents us with the issues each of the patients was facing in their general lives most of the time without con-  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 292 Figure 9. The PsyExpert test results for patient C. On the right are visualized hot spots in association with emotions in the psycho-semantic space in the form of Runge sphere. On the left top the numbers 1 to 5 represent different spheres. Below the row of colors from the most preferred color on the left to the least preferred color on the right by patient C are shown and it defines positions of the flags on the Runge sphere in terms of patient’s preferences. Color on the flags is red for emotions and white for elements. On the left also shown some of the elements (hot spots) tested in the patient C. Figure 10. The PsyExpert test results for patient C three weeks after subconscious teaching. On the right are visualized elements in association with emotions in psycho-semantic space in the form of Runge sphere. On the left top the numbers 1 to 5 represent different spheres. Below the row of colors from the most preferred color on the left to the least preferred color on the right by patient C are shown and it defines positions of the flags on the Runge sphere in terms of patient’s preferences. Color on the flags is red for emotions and white for elements . On the left also shown some of th e elements tested in the patient C.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 293 scious realisation of the issues. Each of the patients presented in this study were bene- ficiaries of the combined treatment of the primary physi- cian and subconscious teaching procedures. These mea- sures returned all patients to good health and normalcy, which was corroborated by the observation of the changes in the patient’s subconscious mind using PsyExpert technology, the patients and primary physician. The above described technologies represent standard- ized quantitative psychological measurements and will help us to decrease the cost and increase the accuracy and effectiveness of psychological help. For most people in the world, the primary care physi- cian is their first and often only contact with the psycho- logical care system. Under-diagnosis, misdiagnosis and under-treatment of psychological problems can result in poor outcomes. As a society, we should invest more in front-end psy- chological health services aimed at reducing the demand for psychological illness care services at the back end. As the first line of contact, primary psychological care units with the testing expertise and coordinating capacity to refer individuals quickly and effectively, rather than GP or acute care hospitals, should be the central focus of the psychological health care system. REFERENCES [1] T. Millon, “Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III,” National Computer Systems, Minneapolis, 1994. [2] T. M. Achenbach and L. A. Rescorla, “Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles,” University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, Burlington, 2001. [3] A. T. Beck, R. A. Steer and G. K. Brown, “Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory,” 2nd Edition, The Psycho- logical Corporation, San Antonio, 1996. [4] M. R. Barrick and M. K. Mount, “The Big Five Personal- ity Dimensions and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis,” Personnel Psychology, Vol. 44, No. 1, 1991, pp. 1-26. [5] J. Cohen and P. Cohen, “Applied Multiple Regression/ Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences,” 3rd Edition, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, 1988. [6] J. E. Exner and P. Erdberg, “The Rorschach: A Compre- hensive System: Advanced Interpretation, Vol. 2,” 3rd Edition, Hoboken, Wiley and Sons, 2005. [7] H. A. Murray, “Thematic Apperception Test manual,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1943. [8] D. Westen, “Social Cognition and Object Relations,” Psy- chological Bulletin, Vol. 109, No. 3, 1991, pp. 429-455. [9] J. R. Meloy and C. B. Gacano, “Rorschach Assessment of Aggressive and Psychopathic Personalities,” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, 1994 [10] C. E. Osgood, G. J. Suci and P. H. Tannenbaum, “The Measurement of Meaning,” Illinois Press, Urbana, 1957. [11] C. E. Osgood, “Representational Model and Relevant Research Methods,” In: I. Pool, Ed., Trends in Content Analysis, Illinois Press, Urbana, 1959, pp. 33-88. [12] C. E. Osgood, “Psycholinguistics, Relativity and Univer- sality,” Proceedings of the International Congress of Psychiatrists, Amsterdam, 1962. [13] C. E. Osgood, “Psycholinguistics,” In: S. Koch, Ed., Psy- chology: A Study of Sciences, McGraw-Hills, New York, 1963. [14] G. A. Kelly, “Behaviour is an Experiment. Perspectives in Personal Construct Theory,” Academic Press, London, 1970. [15] V. O. Leontiev, “Classification of the Emotions,” in Rus- sian, Innovation Centre, Odessa, 2002. [16] I. Smirnov, E. Beznosjuk and A. Zhuravlyov, “Psycho- technologies: Computer Psychosemantic Analysis and Psychocorrection at Subconscious Level,” in Russian, M. “Culture”, 1995. pp. 98-103. [17] J. Deese, “On the Structure of Associative Meaning,” Psychology Review, Vol. 69, 1962, pp. 161-175. [18] J. Deese, “The Associative Structure of Some Common English Adjectives,” Journal of Verbal Learning & Ver- bal Behavior, Vol. 3, No. 5, 1964, pp. 347-357. [19] J. Deese, “Thought into Speech,” American Scientist, Vol. 66, No. 3, 1978, pp. 314-321. [20] J. Deese, “Human Abilities versus Intelligence,” Intelli- gence, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1993, pp. 107-116. [21] N. Dixon, “Subliminal Perception: The Nature of Con- troversy,” McGraw-Hill, London, 1971. [22] N. Dixon, “Preconscious Processing,” John Wiley, New York, 1981. [23] С. Е. Noble, “The Role of Stimulus Meaning in Serial Verbal Learning,” Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 43, No. 6, June 1952, pp. 437-446. [24] C. E. A. Osgood, “Behavioristic Analysis of Perception and Language as Cognitive Phenomena,” In: J. S. Bruner, et al., Eds., Contemporary Approach to Cognition, Har- vard University Press, 1952, pp. 75-118. [25] C. E. Osgood, “Hierarchies in Psycholinguistic Units,” Psycholinguistics, Bloomington, 1965. [26] C. E. Osgood, “Language Universals and Psycholinguis- tics,” Language Universals, Cambridge, 1966. [27] C. E. Osgood, “Semantic Differential Technique in the Comparative Study of Cultures,” In: L. A. Jakobovite and M. S. Miron, Eds., Readings in the Psychology of Lan- guage, Prentic-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1967, pp. 171-200. [28] C. E. Osgood, “Focus of Meaning,” Mouton, 1976. [29] H. Shevrin, “Brain Wave Correlates of Subliminal Stimu- lation, Unconscious Attention, Primary-And Second- Dary-Process Thinking and Repressiveness,” In: M. My- man, Ed., Psychoanalytic Research: Three Approaches to the Study of Subliminal Processes, Psychological Issues Monograph No. 30, International Universities Press, New York, 1973. [30] H. Shevrin, J. A. Bond, A. W. Brakel, R. K. Hertel and W.  Psyche from within: Three Case Studies Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 294 J. Williams, “Conscious and Unconscious Processes: Psychodynamic, Cognitive and Neuropsychological Con- vergences,” Guilford Press, New York, 1996. [31] E. A. Kostandov, “Perceptions and Emotions,” in Russian, Meditsina, Moscow, 1977. [32] E. A. Kostandov, “Functional Asymmetry of Cerebral Hemispheres and Unconscious Perception,” in Russian, Nauka Press, Moscow, 1983. [33] E. A. Kostandov, “Consciousness and Subconscious as a Physiology of Higher Neural Activity in Human,” in Russian, Journal of Higher Neural Activity, 1984, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 401-411. [34] A. R. Luriya, “Язык и сознание,” Ростов н/Д., 319 с, [Language and Consciousness] Rostov n/D. 319, 1998. [35] A. R. Luriya and O. S. Vinogradova, “Objective Research of the Dynamics of the Semantic Systems,” Semantic Structure of the Word, M. Science, 1971, pp. 27-63. [36] L. S. Vygotsky, “Selected Psychological Work,” in Rus- sian, Pedagogika, Moscow, 1959. [37] E. V. Beznosjuk and I. V. Smirnov, “Psycho-Correction, Psycho-Prophylactic, Psychotherapy,” in Russian, Medi- cal Psychology and Psycho-Hygiene, M.1, MMI, 1990, p. 21. [38] S. Ioffe, S. V. Yesin, B. G. Afanasjev and I. K. Nezhda- nov, “Psychosemantic Diagnosis of Alcoholic Dependen- cies Tested at the Subconscious Level in Military Person- nel with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD),” Poly- graph Journal, APA, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2007, pp. 57-69. [39] S. Ioffe, S. V. Yesin, B. G. Afanasjev and I. K. Nezhda- nov, “The Role of Subconscious Effects During the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder With Alcohol Dependencies in Military Personnel,” Polygraph Journal, APA, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2007, pp. 133-148. [40] S. Ioffe and M. Konobeevsky, “Psycho-Semantic Spheres of the Personality among Correctional Facility Employ- ees,” Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2008, pp. 23-34. |