Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.4, 445-453 Published Online April 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.44063 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 445 Marital Patterns among Parents to Autistic Children Hadas Doron, Adi Sharabany Department of Social Work, Tel-Hai Academic College, Tel-Hai, Israel Email: hadasdoron@012.net.il Received January 8th, 2013; revised February 8th, 2013; accepted March 4th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Hadas Doron, Adi Sharabany. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The present research aims to examine the mental welfare of parents to autistic children, the degree of so- cial support they receive and their perceived satisfaction with it, and how these variables affect their cou- plehood. The research population included parents of children between the ages of 4 and 17 diagnosed within the autistic spectrum. Each parent (within 33 couples) received a personal questionnaire, which was completed by 32 women and 23 men. The research questionnaire was composed of four measures: demographics; degree of child’s autism; social support; and mental wellbeing and closeness/distance in the marital relationship. We found that social and familial support is statistically related to positive mari- tal relationships and that the older the child, the less emotional wellbeing is felt by the parents and the more distant their relationship. Keywords: Autistic Children; Marital Relations; Well Being; Social Support Introduction Marital Patterns of Parents of Autistic Children Various factors were found to influence the couple relation- ship of parents to autistic children. In families in which a child was diagnosed with autism and when another disability was discovered, some changes occur that may affect the relation- ships within the family as well as its daily routine. Daily activi- ties become more cumbersome and demand planning, early preparation, and investment of many resources. Some studies that examined such couple relationships discovered that parents encounter difficulties in their marital relations and in reciprocal interactions between family members (Margalit & Heiman, 1986; Benson & Gross, 1989; Baxter et al., 2000). The disa- bility of a child may influence the weave of a marital relation- ship in several ways; it redesigns the organization of the family life and creates a fertile soil for conflicts. The disability has re- percussions on most of the things parents do together: it af- fects sleeping arrangements, work, meals, time spent away from the child, and more (Pazerstone, 1987). The present research aims to examine the mental welfare of parents to autistic children, the social support they receive and their perceived satisfaction with it, and how these variables af- fect their couplehood. The Effect of the Diagnosis of Disability on the Parental System Many studies have found that a child with special needs evokes increased stress and anxiety in his or her family, as well as defensiveness and need for control among family members (Margalit & Heiman, 1986; Baxter et al., 2000; Benson & Gross, 1989). The psychological influences that parents to such children experience are usually weariness and the tendency to become reserved and disengaged from social life. Another ex- pression of parental behavior is impatience towards family members. Heiman (2002) measured the attitudes and feelings of parents to children with special needs in order to determine family resilience and the parents’ coping ability. She found that parents of children with special needs tend to react to the diag- nosis process with emotional outbursts, anger, frustration, guilt, confusion, and sometimes even physical sensations and physi- cal reactions (Heiman, 2002). Kubler-Ross (1978) claimed that reactions of denial and anger prevent parents from taking part in the early intervention process with their developmentally de- layed children. The assumption is that the procreation of a child with a developmental disability causes deep disappointment to parents and results in personal and functional crises accompa- nied by psychological stress, strong feelings of loss, and decline in self-esteem (Rimerman & Portwictz, 1985). Guilt may be the most common reaction among parents following diagnosis. They tend to search for a rational explanation to the diagnosis and often feel responsible for the disability. When a child is di- agnosed as disabled, the family as a whole experiences a crisis, meaning that the demands of the new situation ascend the fam- ily’s ability to reorganize (Baum, 1962; Duvdevani, 2000). Mental Wellbeing among Parents to Autistic Children Mental wellbeing among parents to autistic children is de- scribed in the literature and measured through the following feelings: 1) Stress—Raising autistic children constitutes a powerful and continual stress factor for their parents regarding the diffi- culties in caring for them and the emotional load experienced by the family. Parents undergo a cumulative effect of stress and the weakening of defense mechanisms that enabled fostering of hope when the children were younger. As they grow up, their parents mature and concern for their future increases. This  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY finding is in line with Hollroyd, Brown, Wilker and Simmons’ (1975) research that found that the more mature the child, the more the families were assessed as stressful. Tobing and Glenwick (2001) found a relationship between level of autism and parental stress. When deficits in language; cognition; and sociality were high, so was the degree of stress experienced by the parents. Additionally, they found a positive relationship between the severity of functioning deficiency of the children and the stress reactions among the mothers. Although many studies point to psychological difficulties among families of children diagnosed with functional deficien- cies (such as autism), there are studies that show the ability of some families to display appropriate adaptation (Leyser, 1994; Abbott & Meredith, 1986; Salisbury, 1987). 2) Fear of uncertainty—One of the characteristics of autism is the difficulty in conducting an assessment. The diagnosis process may take a long time and doubts and differences of opinion may arise that negatively affect both parents and chil- dren during his period (Wikler, Wason, & Hatfield, 1983; Paz- erstone, 1987). This situation may give rise to anticipation and hope, from which the fall is harsh and discouraging (Hertz, 2003). 3) Anger—Cohen (1962) and Kennedy (1970) discuss typi- cal stages of a crisis following the diagnosis of a disabled child. One of the phases that follows a period of grief entails rage, anger, frustration, and difficulty in restraining these feelings. It was found that among some of the parents the anger they feel towards their disabled children badly affects their couple rela- tionship (Pazerstone, 1987; Heiman, 2002). 4) Weariness—Coping with raising disabled children and with its psychological effects results in feelings of weariness and mental burnout. Mental burnout is defined as a sense of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by a con- stant and continual mental load; one of its characteristics is the feeling of chronic weariness (Levy-Shiff & Shulman, 1997). Like fear and the anger, weariness brings about a series of pro- blems. It is nerve-racking, and most exhausted parents act out their rage on one another or on their children. It aggravates existing tensions and creates new ones. Stressful relations, loathsome routines, and disappointments leech the energy of the parents and wear them out. Sometimes the weariness is so deep it is hard to identify and struggle against (Pazerstone, 1987). Social Support 1) Friends and extended family—when parents are told that their child is disabled or handicapped, they face the problem of how to tell relatives and friends (McCormack, 1989). Despite their stress, studies show that many parents actively engage in searching for personal and professional sources of support. Many parents reported often discussing the child’s issue with the family (Heiman, 2002), which assists in moderating the stress. Relations with grandparents who tend to grant their chil- dren mental support and practical help in caring for the child also provide a sense of normality (Lazer, 1995). Sometimes a family may modify its structure and bring a relative into the nuclear family’s home in order to alleviate strain and assist the parents in taking care of the disabled child and his or her healthy siblings. Such a change may give rise to new strains and disturb the balance of the family. Social support and reac- tions from the social environment depend greatly on the parents and the way they deal with the situation (Kumpfer & Alva- rado, 2003; Joronen & Astedt-Kurki, 2005). Encountering the public may be a completely different story. When one goes out in public with a disabled, exceptional child, people may exag- geratedly stare or be deterred, which is difficult for many par- ents. Support groups are offered in many areas to help parents recognize their feelings and reconcile with their child’s condi- tion (McCormack, 1989). Additional help from the community may gain expression in external placements and special educa- tion settings that may also alleviate the pressure on parents (Duv- devani, 2000). The key to the constitution of family life is ex- tending alliances and adapting a support system at all levels— family-practitioners community. “Society must provide the person and his family with possibilities and support that will satisfy their needs” (Joronen & Astedt-Kurki, 2005: p. 85). Ac- cording to Turnbull and Turnbull (2002), most parents define quality of life as their children having more support, more friends. Additional studies (Rimmerman & Portwicz, 1987; Dunn et al., 2001) indicate that one of the factors found to most mod- erate the strain and hardships experienced by parents is social support. 2) Receiving help—The disability of a child requires the fa- mily, in most cases, maintain contact with various practitioners and experts. The essence of these contacts and their scope is very different between families. Often families of low socio- economic status fail to provide appropriate medical treatment (Sameroff, 2006; Bal, Van-Oost, & Debourdeaudhuij, 2003; Carbonell et al., 2002). Certain children receive limited techni- cal assistance in hospitals, clinics, or at home. Parents who can afford to retain professionals enjoy their assistance at home as well (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, doctors, nurses etc.). These efforts advance the child and may reduce the fam- ily’s sense of solitude. In contrast, they may impede the fam- ily’s autonomy and independence. Most families need extra assistance, but being exposed to too much advice may bring about infantilism and limit the parents’ freedom to choose their own way of solving problems (Pazerstone, 1987). How the medical and developmental data is communicated to the parents is very significant (Hertz, 2003). Kazak (1984) stated that par- ents require the heavy involvement of health and welfare ser- vices and that place of residence and living conditions are ex- tremely important. How people accept help may stem from cultural differences. Women tend to seek help and accept it more willingly than men. A husband may be jealous of his wife’s ability to seek psycho- logical assistance from professionals and display mixed emo- tions regarding this matter (Baker-Ericzen, Brookman-Frazee, & Stahmer, 2005; Bayat, 2007; Beck, Daley, Hastings, & Ste- venson, 2004; Benzies & Mychasiuk, 2009; Black & Lobo, 2008; Boyd, 2002). One way to bring parents closer is to equal- ize the opportunities they receive. Among many families this means offering extra support to men (on the part of friends, relatives and practitioners) as well as additional opportunities to be constructively involved with the child; while mothers should be granted more opportunities to be away from the family so they can achieve personal fulfillment. Such modifications bring couples closer and assist them in coping with the problems they face in complementary ways (Pazerstone, 1987). Leyser (1994) stresses the need for professionals to be more sensitive to fa- milial characteristics (socio-economic, cultural, and lifestyle) and to adjust adequate interventions. A support program is es- pecially important for mothers who bear the lion’s share of childrearing. Cohen and Cohen (1962) also mentioned possi- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 446  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY bilities of financial aid. Changes in Marital Life among Parents to Autistic Children 1) Communication between partners—as mentioned above, feelings of shame and guilt find expression in the parents’ in- ability to communicate with one another regarding the child (Duvdevani, 2000). Most commonly, the mother is the main caregiver for the special needs child, and this may lead to the partner’s feelings of redundancy. Both partners may feel that they do not have as much time as before to be with each other to enjoy each other’s company. In Heiman’s study (2002), when parents of a disabled child were asked about the ramifications of their situation on various areas of their life, some indicated intensification of their relationship and communication between them. Others asserted that interpersonal communication was ne- gatively affected, new problems were created, and there was a fear of taking responsibility. More arguments, expressions of anger, and impatience occur (Heiman, 2002). Parents are fun- damentally divided in their perception of the nature of their obligations towards the child. They evaluate his or her future options differently, advocate different intervention programs, and may perceive professionals in a different light. They there- fore may attempt to settle many disagreements within an atmos- phere of a profound emotional load. Each of the partners feels deep ambivalence towards the child, the future, and advice from practitioners. This ambivalence is confusing, usually kept in, but bursting out at times of conflict between the partners (Walsh, 1998; Walsh, 2003). It also strengthens the basis for disagreement in the marriage. Mixed emotions prevent both the husband and wife from listening to the other’s ideas and grasp- ing the despair and loneliness of each other. Their common ambivalence, especially if not expressed, may also limit emo- tional options and increase the distance between them (Pazer- stone, 1987). Moreover, it was found that the higher the stress, the less the parents perceive they function efficiently and the more they display negative behavior, speech, and emotion to- wards their children (Beruchin, 1990). 2) Alliance—Some parents feel that their children’s disabil- ity strengthens their feeling of obligation towards one another. The relationship of common grief and misfortune with happi- ness arising from pain may improve their relationship. The rear- ing of disabled children entails much learning, which may also preserve the vitality of a marriage. The partners’ feeling of be- ing allies in a common struggle strengthens them in the face of solitude and despair. The question is how to keep and subsist despite the present pain and how to find ways to moderate the strains imposed on the family. The difficulty does not reside in that few parents deal with the problem, but mainly because only a few freely talk about the strains on their marriage or on their ways of coping. It must therefore be determined that both par- ents and perhaps the children need external psychological help (Twoy, Connolly, & Novak, 2007). A severe disability under- mines the mental strength of the family. The couple cannot to be expected to meet all these needs without assistance; indeed, when parents do receive help from relatives and friends, or pro- fessionals, they are more apt to offer support to one another. Atzils’s (1982) study suggests improvement in the parents’ ability to cope when there is a flexible division of the burden with each of them investing according to their cognitive capa- bilities and their ability to seek and receive help in handling additional demands. Such a pattern of adjustment allows for more successful coping, based both on acknowledging the spe- cial demands and the ability to meet them, on avoiding over- load on one of the parents, and developing a mutual support system. Parents who raise disabled children are under extreme pres- sure. Both mothers and fathers have personal reactions to deal with, in addition to those of their partner. Some marriages are shattered due to the tremendous strain involved in raising a dis- abled child, while many other couples feel their relationship has grown stronger in light of the difficulties (McCormack, 1989). Many mothers and fathers need to be taught to separate be- tween their marriage and the child and his disability (Pazer- stone, 1987). 3) Leisure time—At some time in life many parents discover that family life restricts their movements. We renounce many aspects of our freedom in order to be parents. Certain people long for a pause from the emotional responsibility, the anxiety for the wellbeing of their children, their happiness and their welfare. Others long for the days when they could be more fle- xible, since a child imposes new restrictions on their job, leisure, sleep, and sexual relations. Yet a third group stresses the lack of economic independence, e.g., the inability to resign from a un- pleasant job (Baker-Ericzen, Brookman-Frazee, & Stahmer, 2005; Plumb, 2011). In more positive cases, the pleasure of be- ing a parent is balanced with the loss of freedom or surpasses it. The disability of a child may undermine this balance. Concern for the future is very burdensome for both parents. Practical du- ties affect the little leisure time they have left. Parents feel too weary to go out, while enjoyment from former recreation fades until it is finally abandoned. Tired people begin to treat their weariness as obvious and unchallengeable. “Exceptional” par- ents need to spend more time alone than other parents, yet many times they have less free time (Pazerstone, 1987; Parsons & Lewis, 2010). 4) Role division—Research (Atzil, 1982) shows that division of the burden (i.e., organizing to handle the special difficulties resulting from the situation) between the parents for the most part influences the nature of coping. Most families divide the necessary duties between family members, yet the mother is responsibility for more elements than any other family member (Pazerstone, 1987), with her burden as high as double of that carried by the father (Atzil, 1982; Carr, 1988). Whatever the arrangements are, the disability may complicate the partners’ feelings regarding the division of labor in the household. Many parents face cost-benefit considerations regarding whether to stay at home with the children and handle the household or to go out to work, with the solution depending on many factors. One of them is the nature of family life: the enjoyment vs. sor- row that is involved in staying at home with the children most of the day. When a child is too much of a burden on the mo- ther’s mental and physical resources, she feels that she gives more and receives less than she should. Even if she knows that her husband takes on some duties, she might feel resentful of his freedom and his regular breaks from “exceptional parent- hood” because he works outside the home. It seems that fathers are more apt to cut themselves off from the concerns of home and focus their attention elsewhere (Benzies & Mychasiuk, 2009; Boyd, 2002). Nevertheless, the husband’s relative dis- connectedness may deepen his guilt feelings towards the dis- ability. Such feelings do not benefit either parent, especially if they are felt by the mother. However, there is another aspect in which women are more successful: intensive occupation with Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 447  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY the immediate needs of the child provides them with many opportunities to reconcile with the loss. Mothers learn treatment routines for their children, find assistance, and locate health services. The daily necessity of taking care of the child’s prob- lems forces them to stand firm in the face of their doubts and to re-examine painful emotions (Pazerstone, 1987). It should be kept in mind that in the framework of their traditional roles, mothers are the primary caregivers, and this affects both the degree of familiarity with the functioning and state of the child and their emotional involvement. Fathers, on the contrary, are more distant by virtue of their role as breadwinners, and this affects both their familiarity and emotional involvement (Atzil, 1982). These role differences may generate preconditions for conflict. Atzils’ (1982) study on the division of the burden re- veals that women report doing more than they would want to do at home, while men report doing less than they would desire. The research also examined the degree of consent between mothers and fathers regarding parenthood and revealed that the more the mother reported greater efforts, the less effort was reported by the father, and vice versa. According to Nye (1976), mothers are expected to take on a larger part of the burden of parenthood and perceive it in a positive light, while fathers perceive it is acceptable to reduce their part in running the home. Mothers therefore lack opportunities to leave the house and occasionally disconnect themselves (Bristol, Gallagher, & Schopler, 1988). 5) Stability in marriage—Despite sincere love between the partners, the family may resemble a prison. Two undesirable possibilities confront dejected parents: they can run away, save themselves, and abandon their partner and children; alterna- tively, they can stay, but then they begin to feel hatred towards family members and mourn for lost opportunities. Some threa- ten to leave their families, whether as a way to communicate their despair or to prevent the possibility of being abandoned (Pazerstone, 1987). Adjusting to marriage is important and affects the parents’ ability to cope with raising their children, their ability to resolve conflicts, their satisfaction from marriage, their relationship with their partner, cooperation and their part- ner’s expectation of fulfillment. The birth of a child with a de- velopmental delay disturbs the balance and compels modifica- tion of the family and couple organization. Due to the multipli- city of tasks, parents have much less time for themselves (Le- vy-Shiff & Shulman, 1997; Brobst, Clopton, & Hendrick, 2009). Existing problems in the relationship in addition to coping with an autistic child may turn life intolerably hard and the familial unit may even come apart. When partners function as a team it may render coping easier (Green, 1998). Farber (1962) refers to two types of crises in family and couple life following the birth of a child with developmental delay: 1) Tragic crisis: extreme frustration due to the modification of goals, ambitions, and the substance of life. 2) Role change crisis: coping with the child demands a high level of commitment from both parents, which in the long run creates a fixation in the development of the family and in the role of the parents. This fixation generates worry, dissatisfac- tion, and grief. The child represents to his parents a psychological and physical expression of themselves, an integration of the hered- ity of their characteristic traits, both positive and negative. The characteristics of the child reflect the uniting good between the parents. Disability or retardation may represent the worse that may have come from one of the partners (Ryckman & Hen- derson, 1965). This sense of failure may cause mutual accusa- tions (Levy-Shiff & Shulman, 1997). Parents to autistic chil- dren report lower levels of intimacy in their marriage compared to parents to normative children or to children with other dis- abilities (Fisman, Wolf, & Noh, 1989). Marom (1994) found that parents to children with developmental delay perceive their marriage more negatively compared to parents of children of the same chronological or mental age. Nevertheless, some stu- dies report that the presence of an exceptional child may posi- tively affect the marriage, provided that the families have found appropriate ways to communicate and improve physical and mental cooperation. Moreover, parents can leave their problems aside and make use of the child as a uniting factor (Levy-Shiff & Shulman, 1997). Some researchers failed to find any influ- ence of the child’s disability on marital life; moreover, they claim that the marital system and the parental system should be separate. When pressure on the parental system is not transmit- ted to the marital system, an atmosphere of support and en- couragement is developed (Wikler, 1981; Kazak & Marvin, 1984). Satisfaction from marriage was found as the best pre- dictor for positive coping of a mother dealing with a disabled child (Friedrich, 1979; Twoy, Connolly, & Novak, 2007). De- spite the hardships involved in the upbringing of a child with special needs and its affect on different life stages, parents men- tion positive couple relationships as a source of support and en- couragement (Durlak et al., 2007; Heyman, 2001; Havens, 2005; Brobst, Clopton, & Hendrick, 2009). In summary, relationships take different forms in different marriages, but were found to be much more intense among pa- rents to exceptional children. The presence of a disabled child may transform the familial structure in some ways: it might loosen the boundaries protecting the autonomy of distinct sys- tems within the family; it may make the family more vulnerable to the intervention of external bodies, especially clinicians and other professionals, so that it may reinforce the traditional role division and make it abhorrent (Pazerstone, 1987; Brobst, Clop- ton & Hendrick, 2009; Black & Lobo, 2008). The aim of the present study is to examine the mental well- being of parents of children diagnosed with an autistic disorder, the social support they receive and their perceived satisfaction with it, and how these factors affect the closeness of the couple relationships of the parents. We aspire in this study to respond to some shortcomings that characterize former studies as follows: First, we have found that many essays written by parents about their family experiences lack reference to substantive disagreements between the partners. Most stress the valuable virtues of the partner and the firm support he/she offers. When describing the advancement of their children, they don’t neces- sarily reveal issues that might undermine their marriage (Pazer- stone, 1987). We hope that our research, focusing on the par- ents’ experience rather than that of the exceptional child, will allow for the sincere uncovering of hardships and obstacles in such marriages that have been scarcely studied until now. Second, since the population of autistic children is relatively scarce for empirical sampling, most studies have been con- ducted on families with diverse disabilities. The focus of our research is innovative in that it only includes the autistic popu- lation. Our research hypotheses are: H1. There is a relationship between the intensity of a child’s Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 448  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY autism and aspects of couplehood of the parents (less closeness and more distance between partners). H2. There is a relationship between social, familial and pro- fessional support and satisfaction with these sources of support, and positive couple relationship. H3. The more severe a child’s autism, the less emotional wellbeing is experienced by the parents. Method Research Population The research population included parents of children aged 4 to 17 diagnosed within the autistic spectrum. Each parent (with- in 33 couples) received a personal questionnaire; 32 women and 23 men completed the questionnaire. The participants all live in the northern region of Israel. The demographic characteristics of the sample are as follows: 27.3% (N = 15) have secondary education, 73% (N = 40) have academic education. No subject had only primary education. The average length of marriage was 15.46 years (SD = 5.91); average number of children was 2.77 (SD = 1.03); age M = 35. All participants were married at the time of the study. Research Instrument Our research questionnaire was composed of four measures: Demographic questionnaire—measuring the following vari- ables: age, gender, education, length of marriage, child’s age, family monthly income, date of child’s diagnosis, and charac- teristics of his autism. Degree of child’s autism—a measure examining the child’s autism characteristics including five items scaled 1 - 5, with the score for each child calculated as the sum, ranging from 5 (mild-level disability) to 25 (severe-level disability). Social support questionnaire—including 15 items referring to the extent to which the subjects perceive they receive help and support from various elements in his environment (partner, close family, neighbors, and professionals). The items refer also to the extent to which the respondents are satisfied with the help they receive. The questionnaire was based on the Lazarus and Folkman (1984) support questionnaire, and was adjusted to the new state of parenthood by Levi-Shieff (1995). In order to ex- amine whether items could be divided into different factors, a factor analysis was conducted separately for level of support and perceived level of satisfaction with the support. Two factors were found for level of support: the level of so- cial and familial support (items 8, 10, 12, = .803) and the level of professional support (items 14, 16, 18, = .709); addi- tionally, two factors were found for satisfaction with the sup- port: satisfaction from support from family and friends (items: 9, 11, 13; = .853) and satisfaction from professional support (items 15, 17, 19; = .709). The questionnaire was built on a five-level Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = to a great extent). High correlations were found between the support factors and the satisfaction factors, both in the familial domain (r = .78, p < .000) and in the professional domain (r = .78; p < .000). The instrument’s overall reliability was = .825. Mental wellbeing questionnaire—intended to measure the emotional adjustment of the parents to the diagnosis of their child. The questionnaire contains 16 items taken from Yaku- tiel’s (1990) measure. The subjects were required to rate the degree to which they agree with each item (five-point Likert scale) in the present. A 1 rating points to better emotional well- being, while a 5 rating indicates lower emotional wellbeing. The emotional wellbeing rate is calculated as the average of the answers to the items, after reversing reversed items. Statistical reliability of the scale was found high ( = .82) (Yakutiel, 1995). Reliability of the present sample = .839. Closeness/distance in the relationship questionnaire—intend- ed to measure the marital adjustment of the parents, and to as- sess changes in marital life that took place since the diagnosis of their child from the parents’ viewpoint. The questionnaire contains 19 items, most of which were composed by Yakutiel (1995), that include various statements referring to the marital system and the changes it underwent since the child’s diagnosis. The items are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 indicating a distant relationship and 5 indicating a close relationship). The items indicate change in the marital relationship: some indicate a positive change—more closeness, love, and understanding (items: 52, 51, 50, 49, 48, 47, 43, 41, 39, 36; = .927) and some, a negative change—more distance, anger, and feelings of neglect between the partners (items: 46, 45, 44, 42, 40, 38, 37; = .916). Two additional items (53, 54) were added by us and refer to the relationship with other children in the family. The subjects were asked to rate the degree to which each statement reflects their marital relations since the diagnosis of their child. Procedure The research population was recruited during three months through various treatment centers that deal with education and treatment of autistic children and advising their parents. The ad- ministration of the questionnaires was partially direct (question- naires were completed in the presence of the researchers and handed to them) and partially by means of communication tech- nologies (emails). Participants were promised full secrecy and that their data would not be used for any purpose other than for this study. Results To examine Hypothesis 1, Pearson correlations were calcu- lated, as presented in Table 1. Table 1 indicates that Hypothesis 1 was refuted: No rela- tionship was found between the level of a child’s autism and closeness/distance between his or her parents. In order to examine Hypothesis 2, Pearson correlations were Table 1. Pearson correlations between the severity of the child’s autism and ma- rital aspects of the parents (closeness/distance). Severity of autism Women Negative relationships (distance) N = 32 − .072 (.695) Positive relationship (closeness) N = 32 − .171 (.350) Men Negative relationship (distance) N = 24 .067 (.755) Gender Positive relationship (closeness) N = 24 − .066 (.758) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 449  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY calculated between the support received by the families—fa- milial and professional—perceived satisfaction with the support, and positive/negative relations among the parents, as presented in Table 2. Table 2 points to a moderate positive relationship between receiving social support from family and satisfaction with such support, and marital closeness. i.e., Hypothesis 2 was partially confirmed—social and familial support is related to positive marital relationships. To examine Hypothesis 3, Pearson correlations were calcu- lated between parents’ mental wellbeing and intensity of the child’s autism, see Table 3. Table 3 refutes Hypothesis 3: No relationship was found between the level of the parents’ emotional wellbeing and the in- tensity of their child’s autism. Additional Findings Table 4 presents Pearson correlations between the age of the child and the variables of emotional wellbeing and positive/ne- gative relationships among the parents. Table 2. Pearson correlations between the support (familial and professional) received by the family, their satisfaction with the support, and aspects of the parents’ marital relations (closeness/distance). Social-familial support Professional support Satisfaction with social support Satisfaction with professional support Negative relationships (distance) .213 (.116) − .044 (.746) .184 (.178) .150 (.271) Positive relationship (closeness) .315* (.018) .137 (.312) .339* (.011) .100 (.462) Child’s autism .186 (.169) .201 (.138) − .014 (.918) .090 (.511) Note: *P < .05, **P < .01. Table 3. Pearson correlations between emotional wellbeing and severity of the child’s autism. Negative well being Positive well being Women Severity of child’s autism .276 (.127) − .238 (.190) Gender Men Severity of child’s autism .157 (.465) − .059 (.785) Table 4. Pearson correlations between child’s age, emotional wellbeing and clo- seness/distance of the parents’ marital relations. Child’s age Negative wellbeing N = 56 .036 (.792) Positive wellbeing N = 56 − .309* (.020) Negative relationship (distance) N = 56 − .139 (.307) Positive relationship (closeness) N = 56 − .390** (.003) Note: *P < .05, **P < .01. Table 4 indicates a negative significant relationship between the age of the autistic child and both the positive emotional wellbeing and positive marital relationship experienced by his parents; meaning—the older the child, the less his parents feel emotional wellbeing and the more distanced their relationship. Table 5 shows Pearson correlations between the intensity of the child’s autism and the level of support received and satis- faction with it among the parents. Table 5 shows that the more severe a child’s autism, the more the fathers perceive they receive social support. No such relationship was found among the mothers. Discussion The present research examined the mental wellbeing of par- ents to autistic children, the social support they receive and their perceived satisfaction with it, and the closeness of their marital relationships. Our research focused on a population of parents living in northern Israel. The professional literature re- fers mostly to parents of exceptional children in general, and not specifically to parents to autistic children. In the present re- search, we focus our inquiry on the specific population of par- ents to autistic children, and this constitutes its main innova- tion. Contrary to our predictions, our findings indicate that the level of a child’s autism is not statistically related to the close- ness/distance of the marital relationship as reported by the par- ents, nor to the emotional wellbeing they experience; neverthe- less, we found that the severity of a child’s autism did correlate with the father’s perception of social support, but not with that of the mother. In accordance with our hypothesis, we found that the more a couple receives support from the family and the more it is satisfied with that support, the more the partners report ma- rital closeness. Finally, a negative relationship was found be- tween the child’s age and the emotional wellbeing of the par- ents and their reported marital closeness. The Severity of the Child’s Condition, the Emotional Wellbeing of the Parents, and the Closeness/Distance of Their Relationship As mentioned, we failed to find a statistical relationship be- tween reported closeness or distance in marital relations and the severity of a child’s condition, nor between the severity of a child’s condition and the parents’ emotional wellbeing. The present research was conducted among parents to children who had been positively diagnosed with autism. The literature (Dale, Jahoda, & Knott, 2006; Plumb, 2011) as well as practice indi- cates that the period of uncertainty prior to diagnosis is some- times the most difficult, and entails the potential for low emo- tional wellbeing and tense relationships between the parents. The findings of the present research may suggest a renewed Table 5. Pearson correlations between the severity of the child’s autism, level of social support, and satisfaction with the support. Receiving support Satisfaction with support Men Women Men Women Severity of autism.050* .128 .335 .487 Note: *P < .05, **P < .01. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 450  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY balance and personal and familial organization post-diagnosis, which in turn brings about fewer hardships and less interper- sonal tension. It is possible that the parents’ relationship and their wellbeing are disrupted first and foremost by the disability itself and by the definition of the child as “exceptional,” and not necessarily by the severity of the symptoms (meaning, a child’s low-severity condition may have more effect upon certain par- ents than a child’s high-severity condition, and vice versa). This may be a result of the parents’ personalities, the size of the fa- mily, existing marital conflicts, the perception of the environ- ment, etc. Another explanation relating to a mediating variable may be that the more severe the child’s condition, the more support the family receives from external factors, which relieves the strain on the parents and enables a stable couplehood and greater emo- tional wellbeing. Receiving Social Support and Perceived Satisfaction with It, and the Parents’ Relationship We found that the more social support the parents receive from their families and the more they are satisfied with it, the more they experience close relationships. In contrast, profes- sional support was not found to be related to martial closeness. These findings point to the significance and indispensability of support from the extended family, which is more intimate and more essential, and allows for rapprochement between the part- ners. These are qualities not offered by professional assistance. Additionally, social and familial support constitutes the envi- ronment in which the parents are coping with their daily life and with the child’s special needs. Practitioners as well as fami- lies themselves should be aware of the importance of social and familial support to the parents, and act to promote it. The Autistic Child’s Age and His Parents’ Emotional Wellbeing and Marital Closeness/Distance We found a statistically significant negative relationship be- tween the age of the child and his parents’ emotional wellbeing, as well as their marital closeness. This means that the more au- tistic children age, the less their parents are satisfied and the less close they feel to each other. This finding can be accounted for several ways: the development of autism-related deficiencies that accompany the children’s growing up; the parents’ concern for the fate of their children and finding the proper setting for them; economic difficulties; financing of treatments, medical care, and the like. In addition, a statistically negative relationship was found be- tween the children’s ages and the closeness between their par- ents. This means that the parents’ relationships destabilize as their children age. It is plausible that due to changes and dete- rioration in the children’s condition parents are apt to experi- ence more concerns and strains that negatively affect their cou- plehood. Also, as the children grow older, placement alterna- tives become fewer and parents face the task of finding an ap- propriate place for their children for the rest of their lives, which may cause considerable strain on a daily basis. The Relationship between the Severity of the Children’s Autism and Receiving Social Support and Satisfactio n from It We found that the more defects are displayed by their chil- dren, the more fathers report receiving support. Among mothers no such relationship was found. This finding and the next one were the only ones to be found among men but not among wo- men. It is plausible that receiving social support and being sat- isfied with it are influential variables for men, who apparently show less mental distress and apply more to the search for in- stitutional help, according to the children’s needs. For women, coping with treatment and attending to the children’s special needs rises with the severity of their condition. Since this cop- ing is intensive it may be that receiving social support and be- ing satisfied with it is not sufficient to meet the needs of the women, a fact that may point to their mental state. Receiving Social Support and Perceived Satisfaction with It In our research we found a statistically positive relationship between receiving social support and satisfaction with it, among both men and women. Apparently, support given to parents to autistic children is somehow effective and provides some secu- rity net for them. In addition, receiving all forms of support— social, familial and professional—positively affects the couple relationship. According to our present research, there are some reserve- tions regarding the effect of the severity of the autistic symp- toms. We assume that the mere fact of diagnosis of the autism condition in a child affects his or her parents, regardless of the severity of symptoms. Since most parents participating in this research have only one diagnosed child, they cannot compare the severity of his autistic state to that of other autistic children within the family. A study population will including families in which more than one sibling are diagnosed as autistic may re- veal the affect of this variable on others. In contrast to the severity of symptoms, the child’s age and social support exert significant affect upon the parents. Study Limitations 1) Analysis of the demographic questionnaires reveal that 73% of our sample had academic education, data that may have an effect on some other findings, such as parents applying to receive support; their ability to be assisted by appropriate ser- vice providers; and their understanding of their child’s condi- tion, therefore eliminating its influence on the parents’ wellbe- ing and couplehood, etc. It is possible that the education factor skewed the findings towards a more positive or optimistic di- rection, i.e., reporting fewer mental and relational problems than actually existed. 2) Data collection procedure—questionnaires were usually administered through various institutions that deal with autistic children and their parents. Many institutions expressed their op- position to participating in the study and confidentiality issues made finding relevant families difficult. 3) In the attempt to sample couples, we encountered difficul- ties in receiving responses from the men—many couples return- ed the completed questionnaire of the woman only while men re- frained from sharing their experiences. 4) Since not all the men completed the questionnaires, wo- men outnumbered men in our sample, preventing us from ex- amining intra-couple differences within a familial unit, limiting us to only gender differences among the whole sample. 5) Many autistic children suffer concomitant disorders; there- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 451  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY fore, the parents experienced difficulties in focusing their an- swers only on their autistic condition. Recommendations for Future Research 1) Future studies should try to locate parents to autistic chil- dren who are not being treated or institutionalized. This is bas- ed on the assumption that these parents have not yet entered the stage in which they receive services, and therefore it would be possible inquire as to their needs, their ability to cope with their children’s disability, and their couplehood at an earlier stage. 2) Due to the uniqueness of autism and the special needs of children diagnosed with it and their parents, there exists a need to carry out more studies that deal specifically with this popula- tion rather than with disabled children in general. REFERENCES Abbott, D. A., & Meredith, W. H. (1986). Strengths of parents with re- tarded children. Family Relations, 35, 371-375. doi:10.2307/584363 Baker-Ericzen, M. J., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Stahmer, A. (2005). Stress levels and adaptability in parents of toddlers with and without autism spectrum disorders. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 30, 194-204. doi:10.2511/rpsd.30.4.194 Bal, S., Crombez, G., Van Oost, P., & Debourdeaudhuij, I. (2003). The role of social support in well-being and coping with self-reported stressful events in adolescents. Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 1377-1395. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.06.002 Baum, M. H. (1962). Some dynamic factors affecting family adjust- ment to the handicapped child. Exceptional Children, 28, 387-392. Baxter, C., Cummins, R., & Yiolitis, L. (2000). Parental stress attribu- ted to family members with and without disability: A longitudinal study. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 25, 105- 118. doi:10.1080/13269780050033526 Bayat, M. (2007). Evidence of resilience in families of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51, 702-714. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00960.x Beck, A., Daley, D., Hastings, R. P., & Stevenson, J. (2004). Mothers’ expressed emotion towards children with and without intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48, 628-638. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00564.x Benson, B. A., & Gross, A. M. (1989). The effect of a congenitally han- dicapped child upon the marital dyad: A review of the literature. Cli- nical Psychology Review, 9, 747-758. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(89)90021-4 Benzies, K., & Mychasiuk, R. (2009). Fostering family resiliency: A re- view of the key protective factors. Child and Family Social Work, 14 , 103-114. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00586.x Black, K., & Lobo, M. (2008). A conceptual review of family resilience factors. Journal of Family Nursi ng, 14, 33-55. doi:10.1177/1074840707312237 Boyd, B. A. (2002). Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus on Au- tism and Other Developmen tal Disabilities, 17, 208-214. doi:10.1177/10883576020170040301 Bristol, M., Gallagher, J., & Schopler, E. (1988). Mothers and fathers of young developmentally disabled and non-disabled boys: Adapta- tion and spousal support. Development Psychology, 24, 441-451. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.24.3.441 Brobst, J., Clopton, J., & Hendrick, S. (2009). Parenting children with autism spectrum disorders: The couple’s relationship. Focus on Au- tism and Other Developmen tal Disabilities, 24, 38-49. doi:10.1177/1088357608323699 Carbonell, D. M., Reinherz, H. Z., Giaconia, R. M., Stashwick, C. K., Paradis, A. D., & Beardslee, W. R. (2002). Adolescent protective fac- tors promoting resilience in young adults at risk for depression. Child Adolescent Social Work Jour na l , 19, 393-412. doi:10.1023/A:1020274531345 Carr, J. (1988). Six weeks to twenty one years: A londitudinal study of children with down syndrome and their families. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 29, 407-431. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00734.x Cohen, P. (1962). The impact of handicapped child on the family. So- cial Work, 2, 137-142. Cohen, S., & Cohen, J. (1962). Support systems for families of children with severe disabilities in the USA. The Jewish Special Educator, 1, 22-23. Dale, E., Jahoda, A., & Knott, F. (2006). Mothers’ attributions follow- ing their child’s diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder: Exploring links with maternal levels of stress, depression, and expectations about their child’s future. Autism, 10, 463-479. doi:10.1177/1362361306066600 Dunn, M., Burbine, T., Bowers, C., & Tantleff, S. (2001). Moderators of stress in parents of children with autism. Community Mental Heal- th Journal, 37, 39-52. doi:10.1023/A:1026592305436 Durlak, J. A., Taylor, R. D., Kawashima, K., Pachan, M., DuPre, E., et al. (2007). Effects of positive youth development programs on school, family, and community systems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 269-286. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9112-5 Duvdevani, A. (2000). Resilience and coping of parents and families of children with developmental disabilities. In P. Klein (Ed.), Infants, toddlers, parents and caregivers (pp. 251-271). Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press. Farber, B. (1962). Effects of a severely mentally retarded child on fa- mily. In E. P. Trapp, & P. Himmelstein (Eds.), Readings on the ex- ceptional child (pp. 59-68). New York: Appleton-Century. Fisman, S. N., Wolf, L. C., & Noh, S. (1989). Marital intimacy in par- ents of exceptional children. Canadian Journa l of Psychiatry, 34, 519- 525. Friedrich, W. N. (1979). Predictors of coping behavior of mothers of handicapped children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol- ogy, 47, 1140-1141. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.47.6.1140 Green, R. (1998). The explosive child. New York: Harper Collins. Heyman, T. (2001). Coping process of parents of children with disabili- ties. Issues in Special Education and Rehabilitation, 16, 37-47. Heiman, T. (2002). Parents of children with disabilities: Resilience, co- ping and future expectations. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 14, 159-171. doi:10.1023/A:1015219514621 Hertz, P. (2003). How does parental denial regarding their child’s de- velopmental disability affect reflections and professional decisions? Issues in Special Edu cation and Rehabilitation, 18, 37-43. Hollroyd, J., Brown, N., Wilker, L., & Simmons, J. O. (1975). Stress in families of institutionalized and non-institutionalized autistic chil- dren. Journal of Community Psychology, 3, 26-31. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(197501)3:1<26::AID-JCOP2290030105>3.0 .CO;2-Y Joronen, K., & Astedt-Kurki, P. (2005). Familial contribution to adole- scent subjective well-being. International Journal of Nursing Prac- tice, 11, 125-133. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00509.x Kazak, A. E., & Marvin, R. S. (1984). Differences, difficulties and ada- ption: Stress and social network in families with a handicapped child. Family Relations, 33, 67-77. doi:10.2307/584591 Kennedy, J. (1970). Maternal reaction to the birth of a defective baby. Social Casework, 51, 410-416. Kubler-Ross, E. (1978). To live until we say goodbye. New York: Si- mon and Schuster. Kumpfer, K. L., & Alvarado, R. (2003). Family-strengthening appro- aches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. American Psy- chology, 58, 457-465. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.457 Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Coping and adaptation. In W. D. Gentry (Ed.), The handbook of behavioral medicine (pp. 225-282). New York: Guilford. Lazer, Y. (1995). Resources for coping with external factors and crises in Jewish families with children with developmental limitations. Is- sues in Special Education and Rehabilitation, 10, 17-28. Levy-Shiff, R., & Shulman, S. (1997). Families with a developmentally disabled child: Parent-child marital and family relations. In I. Dovde- vani, M. Hovav, A. Rimmerman, & A. Ramot (Eds.), Parents and per- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 452  H. DORON, A. SHARABANY Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 453 sons with developmental disabilities (pp. 15-34). Jerusalem: Hebrew University Press. Leyser, Y. (1994). Stress and adaptation in Orthodox Jewish families with a disabled child. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64, 376- 385. doi:10.1037/h0079537 Margalit, M., & Heiman, T. (1986). Family climate and anxiety of fa- milies with learning disabled boys. Journal of the American Acad- emy of Child Psychiatry, 25, 841-856. doi:10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60204-1 McCormack, A. (1989). The “tiding”: How to cope with the care of your disabled child. Tel Aviv: Ach Publishers. Nye, F. (1976). Role structure and analysis of the family. Beverly Hills: Sage. Pazserstone, H. (1987). An exceptional child in the family. Hapoalim Library Press. Parsons, S., & Lewis, A. (2010). The home-education of children with special needs or disabilities in the UK. Ryckman, D. B., & Henderson, R. A. (1965). The meaning of retarded children for his parents—A focus for counselors, Social Casework, 2, 15-20. Sameroff, A. (2006). Identifying risk and protective factors for healthy child development. In A. Clarke-Stewart, & J. Dunn (Eds.), Families count: Effect on child and adolescent development (pp. 53-76). New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511616259.004 Salisbury, C. L. (1987). Stressors of parents with young handicapped and nonhandicapped children. Journal of the Division of Early Child- hood, 11, 154-160. Rimmerman, A., & Portwicz, D. (1987). Analysis of resources and stress among parents of developmentally disabled children. Interna- tional Journal of Reha bilitation, 10, 439-445. doi:10.1097/00004356-198712000-00015 Tobing, L., & Glenwick, D. (2001). Relation of the childhood autism rating scale-parent version to diagnosis, stress, and age. New York: Fordham University. Turnbull, A. P., & Turnbull, H. R. (2002). From the old to the new pa- radigm of disability and families: Research to enhance family quality of life outcomes. In P. L. James, C. D. Lavely, A. Cranston-Gingras, & E. L. Taylor (Eds.), Rethinking professional issues in special edu- cation (pp. 115-123). New York: Ablex Publishing. Twoy, R., Connolly, P. M., & Novak, J. M. (2007). Coping strategies used by parents of children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 19, 251-260. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00222.x Walsh, F. (1998). Strengthening family resilience. New York: Guilford Press. Walsh, F. (2003). Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42, 1-18. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00001.x Wikler, L. (1981). Chronic stress of families of mentally retarded chil- dren. Family Relations, 30, 281-288. doi:10.2307/584142 Wikler, L., Wasow, M., & Hatfield, E. (1983). Seeking strengths in fa- milies of developmentally disabled children. Social Work, 28, 313- 315.

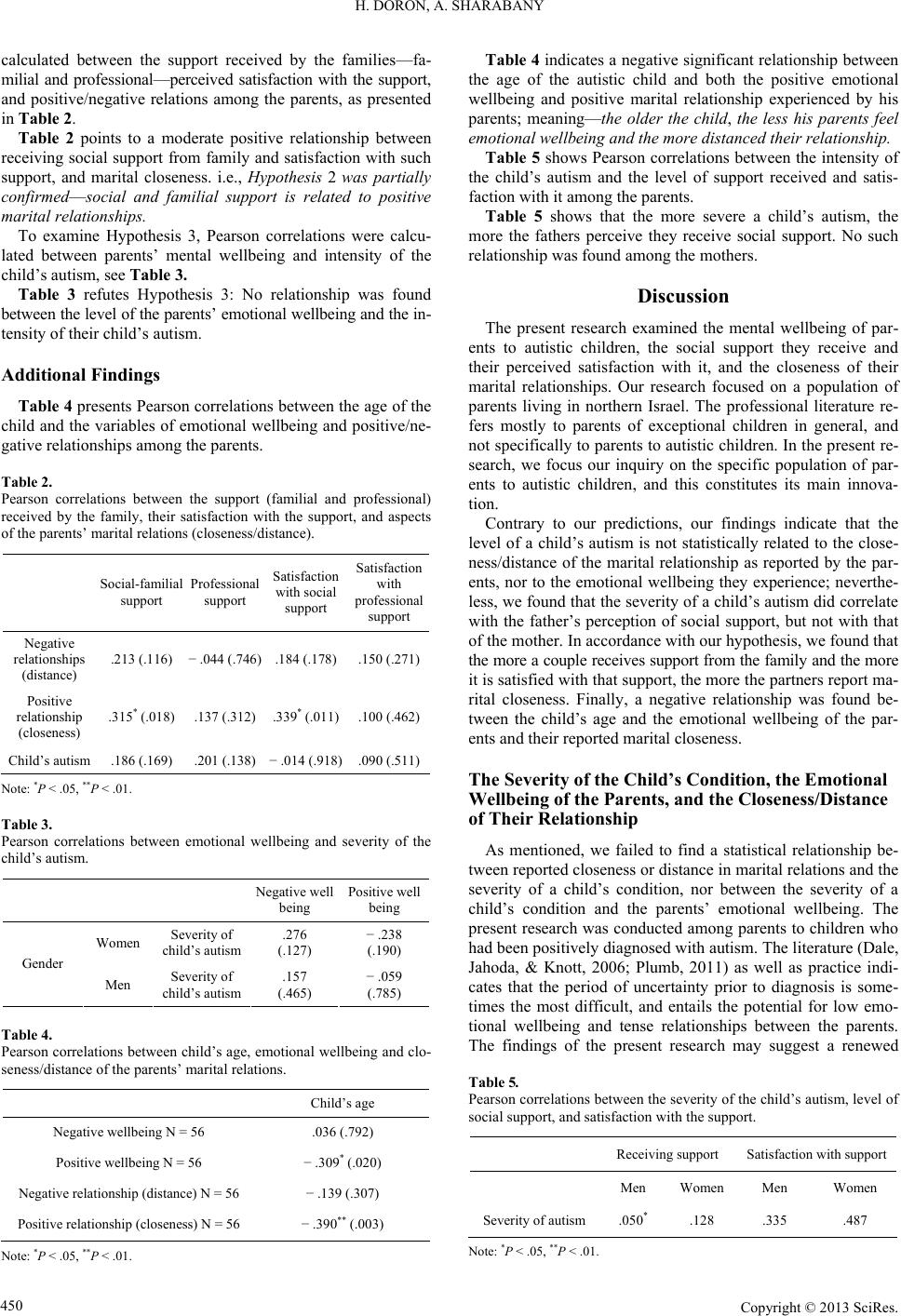

|