Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.4, 438-444 Published Online April 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.44062 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 438 Thou Shalt Not Steal: Effects of Normative Cues on Attitudes towards Theft Judith de Groot1, Wokje Abrahamse2, Sarah Vincent1 1Department of Psychology, Bournemouth University, Poole, UK 2Department of Psychology, University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada Email: jdgroot@bournemouth.ac.uk Received January 14th, 2013; revised February 13th, 2013; accepted March 11th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Judith de Groot et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In this study, we examine how normative cues influence attitudes towards theft. In a 3 × 2 × 2 within-sub- jects design (N = 120), we found that people had more negative attitudes towards theft when: 1) a higher value item was stolen than when a lower value item was stolen; 2) the theft took place in a public setting than when it took place in a private setting; and 3) the theft took place in a tidy rather than messy setting. Furthermore, our findings showed interaction effects between the value of a stolen item and 1) the clean- liness of the environment; and 2) the privateness of a setting, on attitudes towards theft. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed. Keywords: Normative Influence; Social Norms; Theft; Injunctive Norms; Descriptive Norms Introduction The number of theft related incidences declined during the period of 2009-2010 (Research Development Statistics (RDS), 2011). While this appears to be good news, the latest crime sta- tistics show that around 1440 thefts are reported each day and this figure probably even falls short of reality (Crimestoppers, 2010). Crimestoppers (2010) suggests that a figure double this size would perhaps be more representative of actual levels of theft. Given the prevalence of theft, it is an important area to study. Acts of theft may cause damage to society and individuals, and are generally characterized by a lack of consideration for other people (Cromby, Brown, Gross, Locke, & Patterson, 2010). That is, it is regarded as a typical immoral behavior. Attitudes are an important predictor of moral intentions and behaviors, including a variety of prosocial and antisocial be- haviors (e.g., Anker, Feeley, & Kim, 2010; Chen & Chiu, 2009; De Groot & Steg, 2007; Hurd, Zimmerman, & Reischl, 2011). Different scholars have shown that attitudes towards theft play an important role in predicting intentions and subsequently theft behaviors (e.g., Tonglet, 2002; Cronan & Al-Rafee, 2008; Wang, Chen, Yang, & Farn, 2009; Henle, Reeve, & Pitts, 2010). Therefore, examining the factors influencing attitudes towards theft can provide useful ways to decrease the occurrence of theft. Theft is not a desirable behavior as it is not in line with commonly held “social norms” in society. Social norms are thought to be beliefs about what are common and accepted behaviors (Schultz & Tabanico, 2009). Research suggests that attitudes that are prevalent in an individual’s social network can influence the formation of the individual’s own attitude (e.g., Huckfeldt & Sprague, 1991; Visser & Miribile, 2004). Conse- quently, social norms may be relevant for predicting attitudes. Empirical studies indeed suggest that social norms are strong predictors for attitudes (e.g., Ajzen, 1988; Jasinskaja-Lahti, Mä- hönen, & Liebkind, 2011; Nesdale & Lawson, 2011; Nikitas, Avineri, & Parkhurst, 2011). Social norms can be activated by a variety of cues in the en- vironment. In this study, we examine how normative cues in a theft context may influence attitudes towards theft. By doing so, we contribute to the theoretical development of the influence of normative cues on attitudes towards theft. Normative Cues and Attitudes towards Theft The Effect of the Value of a Stolen Item and Privateness of Setting The focus theory of normative conduct (Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno, 1991; Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990) explains how social norms influence attitudes. The theory asserts that social norms will mainly affect attitudes when they are salient Cialdi- ni and colleagues (1990; Cialdini et al., 1991; Reno, Cialdini, & Kallgren, 1993; Kallgren, Reno, & Cialdini, 2000) make a dis- tinction between two types of social norms, that is, descriptive and injunctive social norms. Descriptive social norms demon- strate what is typically done in a particular situation (Cialdini et al., 2006). Injunctive social norms refer to what ought to be done in the situation and guide behavior through perceptions of whether other people would sanction the behavior in question (Reno et al., 1993). In most societies the injunctive norm will be against theft because theft is generally not endorsed— “Thou shalt not steal.” Normative cues are elements in the environment that convey important information that may trigger social norms. Different potential normative cues may make injunctive and descriptive norms focal. An example of a normative cue is the financial  J. DE GROOT ET AL. value of the stolen item. Wenzel (2004) found that people were more likely to avoid anti-social behavior when the severity of the sanctions as a result of engaging in that behavior increased. Mulder and colleagues (Mulder, Verboon, & De Cremer, 2008) suggest that more severe sanctions evoke stronger social judg- ments with regard to breaking the rules than milder sanctions. Related to the focus theory of normative conduct (Cialdini et al., 1991), the thought of social sanctions may activate one’s in- junctive norms of anti-theft. A higher level of loss (in material or emotional value) is incurred by victims of theft when an item is more expensive. We therefore assume that the perceived so- cial sanctions of the theft of high value items are perceived to be more severe than the theft of low value items: people will have more negative attitudes towards theft if a higher value item is stolen than when a lower value item is stolen (Hypothe- sis 1). Lapinski and Rimal (2005) focus on another type of norma- tive cue that may strengthen the influence of social norms on attitudes towards theft, that is, the extent to which an environ- ment in which the theft takes place is private or public. They suggest that injunctive norms will exercise little influence over attitudes and behavior when behavior is not observable and therefore cannot be scrutinized. Related to the focus theory of normative conduct (Cialdini et al., 1991), in a private setting the non-observable character will make the anti-theft injunctive norm less focal than in a public setting. Consequently, people will have more negative attitudes towards theft when the theft takes place in a public setting, than when the theft takes place in a private setting (Hypothesis 2). Conflicting Normative Cues and Attitudes towards Theft: Effect of Tidy vs Messy Setting Normative cues can conflict in specific situations. For exam- ple, in a messy setting, the normative cue “presence of mess” signals that many people litter (making the descriptive norm of littering salient), which conflicts with the generally salient (an- ti-litter) injunctive norm. Results of studies by Cialdini and col- leagues (1990) indicate that an injunctive anti-litter norm is not as influential in this “conflicting” setting as it is in a setting where the descriptive norm supports the injunctive norm. There- fore, descriptive and injunctive norms should be aligned to be able to exert the strongest normative influence on attitudes and behavior (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005; Schultz & Tabanico, 2009). When the descriptive and injunctive norms are not aligned, the descriptive norm will overpower the injunctive norm. Studies indeed show that the injunctive norm is not as influential in a situation where the descriptive norm conflicts with the general injunctive norm (e.g., Schultz, Khazian, & Zaleski, 2008; Ja- cobson, Mortensen, & Cialdini, 2011). Even more so, Keizer, Steg and Lindenberg (2008) show that if a descriptive norm violates the injunctive norm it will not only decrease the influence of a specific injunctive norm, but also of other injunctive norms in that setting. The study showed that when the descriptive norm violated an injunctive norm, such as the anti-litter injunctive norm, it resulted in the inhibi- tion of other injunctive norms as well, such as the anti-theft injunctive norm. For example, participants were more likely to steal a letter including 5 Euros from a letterbox when this let- terbox was surrounded by litter (i.e., violation of the injunctive anti-litter norm) than when it was in a non-littered environment (i.e., no violation of the injunctive anti-litter norm). Keizer and colleagues (2008) refer to the cross-norm inhibition effect in such situations. Therefore, the cleanliness of an environment may function as a normative cue in influencing the relationship between social norms and attitudes towards theft. That is, in a tidy setting, there will be no signs indicating that specific in- junctive norms are violated and therefore the injunctive norm towards anti-theft will remain focal. However, in a messy set- ting, the injunctive norm (i.e., “you should be tidy”) will be violated which may result in a decrease in strength of the anti- theft injunctive norm. Therefore, we expect that people will have more negative attitudes towards theft when the theft takes place in a tidy setting than when the theft takes place in a messy setting (Hypothesis 3). Normative Cues and Attitudes towards Theft: Interaction Effects The possible influence of the value of a stolen item on atti- tudes towards theft is based on the perceived level of social sanctions (Reno et al., 1993) and as such may draw attention to the anti-theft injunctive norm. As suggested by Cialdini and colleagues (2006), normative influence can be exerted in tidy settings (i.e. there are no “norm-violations”), so injunctive norms such as “you should not steal”, will be salient and spur attitudes and behavior. We assume that the theft of low or high value items will draw no extra attention to the already present and salient anti-theft injunctive norm in such situations. However, in messy settings, where cross norm-inhibition takes place, the value of a stolen item may compensate for the inhibition of the anti-theft injunctive norm because the thought of social sanc- tions may strengthen or activate someone’s injunctive norms of anti-theft. Therefore, we expect an interaction between the va- lue of a stolen item and the cleanliness of the environment on attitudes towards theft: attitudes towards theft will be less af- fected by the value of a stolen item in tidy settings where the injunctive norm is already more salient than in a messy setting where the injunctive norm is inhibited (Hypothesis 4). The injunctive anti-theft norm is most salient in public envi- ronments where behavior is observable and can be scrutinized than in private settings where this is less the case (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). The influence of the value of the stolen item on attitudes towards theft is based on the level of expected social sanctions (Reno et al., 1993) which may also make the anti- theft injunctive norm focal. In public settings, where this anti- theft injunctive norm is already salient, the value of the stolen item may be less effective in focusing attention to the injunctive norm than in private settings where this norm is less salient. Therefore, we expect another interaction effect between the value of a stolen item and the level of privateness of a setting on attitudes towards theft. That is, attitudes towards theft will be less affected by the value of a stolen item in public settings where the injunctive norm is already more salient than in pri- vate settings where the injunctive norm is less focal (Hypothe- sis 5). Aim Study The aim of our study is to examine the main and interaction effects of normative cues on attitudes towards theft, hereby increasing the knowledge of how physical characteristics of theft can function as normative cues to change such attitudes. That is, we examine the main and interaction effects of: 1) the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 439  J. DE GROOT ET AL. value of the stolen item; 2) the privateness of a setting in which the theft takes place; and 3) the cleanliness of the environment in which the theft takes place on attitudes towards theft. Method Design and Variables We used a 3 × 2 × 2 within-subjects design to examine the influence of normative cues on attitudes towards theft. The first independent variable, value of a stolen item, had three levels (i.e., low/medium/high value item). The second independent variable, privateness of the setting, included two levels (i.e., private/public environment). The third variable, cleanliness of the environment, had two levels (i.e., tidy/messy environment). The dependent variable was attitudes towards theft. Participants We recruited an opportunity sample of 120 undergraduate students from Bournemouth University’s social seating areas. The sample consisted of 80 females and 40 males with a mean age of 21.4 (SD = 4.5). All participants were familiar with shar- ing accommodation with people other than family members as the questionnaire focused on theft scenarios in this type of ac- commodation. The items in the scenarios were chosen based on their relevance for this specific group of participants. Procedure and Materials A pilot study was conducted in order to gather information on which object of theft would be relevant to the population of interest. Wine was selected as it was most relevant to the focus population (100% of N = 30 had owned wine). The scenario in which it was implied that a theft was taking place was also simplified for wine as one cannot borrow the contents of a wine bottle, unlike other items such as a book. Four versions of a 12 scenario, 24 item questionnaires were created using identical scenarios detailing a theft but in differ- ent order of presentation to avoid order effects. The scenarios were designed to systematically and exhaustively manipulate all levels of the independent variables. The value of the stolen item was manipulated by stating whether the bottle of wine was either £3, (i.e., low value item), £8, (i.e., medium value item) or £20, (i.e., high value item). A pilot study (N = 30) showed high levels of agreement in operationalizing low cost wine as £3 (97% in agreement), medium cost wine as £8 (70% in agree- ment) and high cost wine as £20 (70% in agreement). The pri- vateness of the setting was made clear by indicating whether the wine was either in a room of a home (i.e., private) or in a shop (i.e., public). Finally, the cleanliness of the environment was emphasized by including a reference to a tidy and struc- tured environment or to a messy and unstructured environment. Steps were taken to ensure the layout of each scenario was consistent with the other scenarios; names included in scenarios were from the same origin to avoid possible confounding ef- fects of discrimination, and both male and female names were randomly used throughout the scenarios. An example of a “medium value, public setting, tidy envi- ronment” scenario was: “Anna is looking in her local shop [public setting] for some sweets; she does not find any she wants and so moves on to the next aisle. Anna is off to a party tonight so decides to look at the wine. She spots a bottle for £8 [medium value item] neatly lined up [tidy environment] on the shelf which she picks up and quickly drops in her handbag. Anna looks for a little longer and then leaves.” Each scenario was followed by two items measuring one’s attitude towards theft. Acceptability has been suggested as one of the main dimensions of attitudes and has been used as a tool for assessing attitudes in a number of studies (e.g., De Groot & Steg, 2009; Posthuma & Dworkin, 2000; Terrade, Pasquier, Reerinck-Boulanger, Guingouain, & Somat, 2009). Therefore, we measured attitudes towards theft was by assessing the ac- ceptability dimension of attitudes towards theft, measured on a 7-point likert-type scale ranging from “very unacceptable” to “very acceptable”. In addition to acceptability judgments, re- search has also found that an individual uses projections of their own attitudes when making inferences about the attitudes of someone else (e.g., Ames, 2004; Goel, Mason, & Watts, 2010). That is, an individual’s inference about another person’s atti- tude towards theft may be an indirect measure of their own attitude towards theft without linking the behavior directly to themselves. Therefore, a second item to conceptualize attitudes towards theft was to ask participants to evaluate how acceptable they thought other people would rate the theft in the specific scenarios. The attitude towards theft was computed by sum- ming the scores of both items and dividing them by two. The attitude scale appeared to have a good internal consistency (α = 0.90; M = 1.82, SD = 0.52). Results Main Effects of Normative Cues on Attitudes towards Theft In Table 1, we show descriptive statistics of attitudes to- wards theft for the three normative cues. These statistics sug- gest that participants’ attitude toward theft were more favorable when: the stolen item was less expensive, the theft took place in a private instead of a public setting, and when the setting in which the theft took place was messy rather than tidy. We employed a 3 × 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA to test whether the differences in mean scores were statistically signifi- cant. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the three main effects. 95% Confidence Interval MSD Lower Bound Upper Bound Privateness Setting Private Public 2.11 1.52 0.91 0.72 1.99 1.42 2.24 1.63 Cleanliness Environment Tidy Messy 1.78 1.85 0.82 0.81 1.68 1.76 1.88 1.95 Value Stolen Item Low Medium High 2.07 1.87 1.59 1.02 0.78 0.65 1.93 1.69 1.51 2.21 1.89 1.68 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 440  J. DE GROOT ET AL. was violated for the main effect of cost of the item on attitude, X2 (2) = 34.82, p < 0.001. Therefore degrees of freedom for the main effect of cost of item on attitude were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity (ɛ = 0.80), which alters the significance value of the F-ratio. There was a significant main effect of cost of the stolen item on attitudes towards theft, F (1.59, 189.56) = 46.78, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.28. Post hoc pair-wise comparisons using a Bon- ferroni adjustment indicated that participants’ attitudes towards the theft of low value items (M = 2.07) was significantly higher than for high value items (M = 1.59, F(1, 119) = 63.56, p < 0.001). And, attitude towards the theft of medium value items (M = 1.79) was significantly higher than attitudes towards the theft of high cost items (F (1, 110) = 25.83, p < 0.001). There was a significant main effect of privateness of a setting on attitudes towards theft, F (1, 119) = 75.86, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.39. Participants’ attitudes towards theft were signifi- cantly more favorable for thefts in private settings (M = 2.11) than for thefts in public settings (M = 1.52). Finally, there was a significant main effect of cleanliness of the environment on acceptability evaluations, F (1, 119) = 6.95, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.055. Participants’ attitudes towards theft were significantly more favorable for thefts in messy environ- ments (M = 1.85) than for thefts in tidy environments (M = 1.78). Interacti on E ffects of Normative Cu es on Attitude s towards Theft Table 2 shows descriptive statistics of attitudes towards theft for the interaction effect between the three normative cues. Figures 1 and 2 show the linear pattern of the mean scores. Means suggest that attitude towards thefts of low cost, medium value items and high value items increase in strength in a linear pattern in both the private and public settings and the tidy and messy settings. Attitude towards theft appear lower for the theft of low, medium and high value items in private settings and in messy settings than in public settings and tidy settings. Table 2. Descriptive statistics for interaction effects. 95% Confidence Interval M SD Lower Bound Upper Bound Privateness Setting* Value Item Public* Low Value Public* Medium Value Public* High Value 1.72 1.46 1.38 0.81 0.61 0.51 1.58 1.35 1.29 1.87 1.57 1.48 Private* Low Value Private* Medium Value Private* High Value 2.42 2.11 1.80 1.04 0.80 0.65 2.23 1.97 1.69 2.61 2.26 1.92 Cleanliness Environment* Value Item Messy* Low V alu e Messy* Medium Value Messy* High V alue 2.13 1.86 1.58 0.83 0.62 0.48 1.98 1.75 1.49 2.28 1.97 1.67 Tidy* Low Value Tidy* Medium V alue Tidy* High Value 2.02 1.71 1.61 0.79 0.60 0.53 1.87 1.61 1.51 2.16 1.82 1.70 Figure 1. Relationships between value of the stolen item and privateness of the setting on attitudes towards theft. Figure 2. Relationships between value of the stolen item and cleanliness of the environment on attitudes towards theft. Results of the ANOVA confirmed that there were indeed two significant interaction effects. First, an interaction effect was observed for the cost of a stolen item and the privateness of the setting on attitudes towards theft, F (1.86, 221.80) = 6.56, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.05. This interaction was further investigated by simple main effects. Given the fact that there were six tests of simple effects, the criterion for significance was adjusted to 0.008 (i.e., 0.05/6). In public settings, attitudes towards theft were significantly more favorable when the value of the stolen item was low (M = 1.72) compared to when the value of the stolen item was medium (M = 1.46: t (119) = 4.83, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.44) and compared to when the value of the stolen item was high (M = 1.38): t (119) = 5.64, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.51. In private settings, attitudes towards theft were more favorable in general, but especially when the value of a stolen item was low (M = 2.42) compared to medium (M = 2.11; t (119) = 4.38, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.40) or high (M = 1.80; t (119) = 6.99, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.64) value items. In pri- vate settings, the difference between the medium and high value stolen item was significant as well (t (119) = 4.67, p < Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 441  J. DE GROOT ET AL. 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.43). In line with our hypothesis, the rela- tionship between attitude towards theft and the value of the stolen item is moderated by the privateness of the setting, in such a way that the value of an item has a stronger effect on attitudes when the theft occurs in a private setting compared to when it occurs in a public setting. Second, there was an interaction effect between the value of a stolen item and the cleanliness of the environment with re- spect to people’s attitudes towards theft, F (2, 238) = 4.25, p = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.03. Simple main effects showed that in mes- sy settings, attitudes towards theft were most favorable when the value of the stolen item was low (M = 2.13) rather than me- dium (M = 1.86) or high (M = 1.58). The differences between the low value and medium value (t (119) = 4.79, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.44), low and high value (t (119) = 7.82, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.71) and medium and high value items (t (119) = 5.81, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.53) were significant. In tidy settings, attitudes towards theft were especially favorable when the value of a stolen item was low (M = 2.02) compared to medium (M = 1.71; t (119) = 4.99, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.46) or high (M = 1.61; t (119)= 6.29, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.57) value items. In tidy settings, after adjusting the signifi- cance criterion to 0.008, the difference between medium and high value items was not significant (t (119) = 2.13, p = 0.036, Cohen’s d = 0.19). In line with our hypothesis, the relationship between attitudes and value of the stolen item was moderated by the cleanliness of the environment: the value of an item was more influential in shaping attitudes in messy settings as op- posed to tidy settings. Discussion This study examined the main and interaction effects of these normative cues on attitudes towards theft. Consistent with Hy- pothesis 1, participants had most favorable attitudes towards theft when a low value item was stolen than when a medium or high value item was stolen. Attitude favorability significantly decreased between the low and medium value item and be- tween the medium and high value item. The perceived social sanctions for theft of more expensive stolen items may be more severe than for less expensive items. The thought of severe sanctions may trigger avoidance of anti-social behaviors (Wen- zel, 2004), such as theft, and, more severe sanctions will evoke stronger judgments towards rule breaking (Mulder et al., 2008); hence, the attitudes towards such behaviors may be adjusted ac- cordingly. Findings are consistent with the notion of Reno et al. (1993) that injunctive norms guide behavior through perception of whether most others would sanction the behavior and sug- gest that the thought of social sanctions may strengthen or acti- vate someone’s injunctive norms of anti-theft. Beliefs about sanction severity however, were not explicitly examined in this current research and therefore explanations of the differing in- fluence of item value are based on inference. The findings of this research are however consistent with the theory that sanc- tion severity affects the level of normative influence and there- fore severity of sanction may be an underlying influence on at- titudes towards theft. The privateness of a setting could be another potential nor- mative cue to influence attitudes towards theft. We found that people show more negative attitudes towards theft when the theft takes place in a public than a private setting, supporting Hypothesis 2. Like the findings of Kallgren et al. (2000) and Schultz et al. (2008), results of this current research indicated that the injunctive norm can have an influence in both public and private environmental settings. However this current re- search went further by examining if there was any difference in the level of influence exerted between the two types of settings. The notion for this extension was based upon suggestions made by Lapinski and Rimal (2005) that the level of normative in- fluence exercised would be dependent on the level of privacy of an environment. Our finding is in line with the notion that in- junctive norms will exercise little influence over attitudes and behavior when behavior is not observable and therefore cannot be scrutinized (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). Because norms will mainly influence behavior when focal (Cialdini et al., 1991), in a private setting the non-observable character will make the an- ti-theft injunctive norm less focal than in a public setting hereby inhibiting its potential influence on attitudes towards theft. Attitudes towards theft were significantly more negative in tidy than in messy settings, providing support for Hypothesis 3. These results provide further evidence for the observation that if the descriptive norm (littering) violates an injunctive norm (“you should not litter”) in a specific situation, it will also de- crease the influence of other injunctive norms (“you should not steal”) in that setting (see Keizer et al., 2008). This result does not only hold for changing behaviors as indicated by Keizer and colleagues (2008), but also for changing attitudes towards the behavior. Keizer and colleagues (2008) refer to this as the “cross-norm inhibition effect.” There was an interaction effect between the value of a stolen item and the cleanliness of the environment on attitudes to- wards theft, supporting Hypothesis 4. That is, attitudes towards theft were less affected by the value of a stolen item when the theft took place in clean settings, where presumably the injunc- tive anti-theft norm was more salient, as compared to a messy setting, where the injunctive norm may have been inhibited by the salient descriptive norm to litter. A significant difference was found between medium and high value items and tidy and messy environments, with the theft of a high value item pro- ducing a less dramatic increase in attitude strength in tidy set- tings than in messy settings. This difference was not significant for the theft of low value and medium value items in tidy and messy settings. As suggested by Cialdini et al. (2006), norma- tive influence may already be exerted in clean settings (con- veying an anti-littering norm) and thus the theft of low cost items drew no extra attention to the anti-theft injunctive norm; medium and high value items on the other hand may still focus some more attention to this anti-theft norm. In messy settings, which may have downplayed the saliency of the anti-theft in- junctive norm (i.e., cross norm inhibition effect, see Keizer et al., 2008), the value of a stolen item seemed to compensate, at least partly, for the inhibition of the anti-theft injunctive norm. Finally, the interaction effect between the value of a stolen item and the privateness of a setting on attitudes towards theft was in part supported (Hypothesis 5). That is, attitudes towards theft were less affected by the value of a stolen item in public settings where the injunctive norm was already more salient, than in private settings where the anti-theft injunctive norm was assumed to be less focal. There was a significant difference between medium and high value items and private and public environments, with the theft of a high value item producing a less dramatic increase in attitude strength in public than in pri- vate settings. There was no significant difference between the theft of low value and medium value items in public and private Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 442  J. DE GROOT ET AL. settings. This result is in line with assumptions from Lapinski and Rimal (2005) and Reno et al. (1993) who assume that both the privateness of the setting as well as the value of a stolen item may activate an injunctive norm towards anti-theft. Our results therefore suggest that there is a ceiling-effect for the activation of the anti-theft injunctive norm; if the injunctive norm for anti-theft is already salient, as is the case in public settings, the theft of a low value item will not draw any more attention to the anti-theft injunctive norm; medium and high va- lue items on the other hand may be focusing attention to this anti-theft norm slightly more. However, in private settings, where the injunctive norm is not salient, the value of a stolen item contribute to the attitudes towards theft regardless of whe- ther the value of the stolen item is low, medium or high. Although our results are consistent with our expectations, it may be argued that the privateness of the setting was not the factor addressed in the theft scenarios. The thefts in the private scenarios detailed the appropriation of a known housemates wine, whereas no relationship between shop owner and perpe- trator of theft was described in the scenarios for public settings. Individuals evaluating their attitudes towards theft in the private settings may have been influenced by the possibility that con- sent to take the wine would have been given if the owner knew about the circumstances. However, neither in the public or the private theft scenarios it was insinuated that consent was given to take the item. In the eyes of the law, if it is believed that consent is given, the appropriation of property is not considered theft (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1968). The fact that no such consent was insinuated in our scenarios makes it less likely that the extent to which the owner would agree with tak- ing such item was a confounding factor in our study. However, future studies should more clearly distinguish between the pri- vateness of the setting and the extent to which the perpetrator knows the victim of theft. The predictive power of attitudes has been shown to be sig- nificant in predicting a variety of normative behaviors (e.g., Anker, Feeley, & Kim, 2010; Chen & Chiu, 2009; De Groot & Steg, 2007; Hurd, Zimmerman, & Reischl, 2011), including theft intentions and behaviors (e.g., Tonglet, 2002; Cronan & Al-Rafee, 2008; Henle et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2009). How- ever, attitudes may not always result in subsequent behavior. The use of scenarios allows for complex manipulations of mul- tiple variables; which may be hard to achieve and time con- suming when using field studies. It would however be useful to know if the findings of this study are replicable in field studies that measure observable behaviors. Findings of this research show which cues in the environ- ment could function as normative cues in a theft situation which may potentially have practical implications for theft deterrence. Findings for example provide an explanation of why it is im- portant to decrease feelings of privacy to decrease positive attitudes towards theft. Decreasing feelings of privacy increases the likelihood that someone believes the behavior will be ob- served. This knowledge is already widely applied in public communities and retail via the use of CCTV cameras. But even relatively easy and less costly cues could potentially decrease one’s feelings of privacy. For example, simple cues, such as showing an image of a pair of eyes (Bateson, Nettle, & Roberts, 2006), making one believe that someone is watching them (Pi- azza, Bering, & Ingram, 2011), or priming with religious con- cepts (Shariff & Norenzayan, 2007), could potentially support an anti-theft injunctive norm. Future research should examine how such cues result in norm activation, hereby decreasing the occurrence of theft. REFERENCES Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T Ames, D. R. (2004). Strategies for social inference: A similarity con- tingency model of projection and stereotyping in attribute prevalence estimates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 573- 585. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.573 Anker, A. E., Feeley, T. H., & Kim, H. (2010). Examining the atti- tude-behavior relationship in prosocial donation domains. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 1293-1324. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00619.x Bateson, M., Nettle, D., & Roberts, G. (2006). Cues of being watched enhance cooperation in a real-world setting. Biology Letters, 23, 412- 414. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0509 Chen, C. C., & Chiu, S. F. (2009). The mediating role of job involve- ment in the relationship between job characteristics and organiza- tional citizenship behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149, 474-494. doi:10.3200/SOCP.149.4.474-494 Cialdini, R. B., Demaine, L. J., Sagarin, B. J., Barrett, D. W., Rhoads, K., & Winter, P. L. (2006). Managing social norms for persuasive im- pact. Social Influence, 1, 3-15. doi:10.1080/15534510500181459 Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental So- cial Psychology, 24, 201-234. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5 Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce lit- tering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1015-1026. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015 Crimestoppers (2010). Crime news: Latest crime statistics and surveys. Wallington: Crimestoppers. http://www.crimestoppers-uk.org/crime-prevention/latest-crime-stati stics Cromby, J., Brown, S. D., Gross, H., Locke, A., & Patterson, A. E. (2010). Constructing crime, enacting morality: Emotion, crime and anti-social behaviour in an inner-city Community. The British Jour- nal of Criminology, 50, 873-895. doi:10.1093/bjc/azq029 Cronan, T. P., & Al-Rafee, S. (2008). Factors that influence the inten- tion to pirate software and media. Journal of Busin ess Ethics, 78, 527- 545. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9366-8 De Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2007). General beliefs and the theory of planned behavior: The role of environmental concerns in the TPB. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 1817-1836. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00239.x De Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2009). Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility and norms in the norm activa- tion model. Journal of Social Psychology, 149, 425-449. doi:10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449 Goel, S., Mason, W., & Watts, D. J. (2010). Real and perceived attitude agreement in social networks. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 99, 611-621. doi:10.1037/a0020697 Henle, C. A., Reeve, C. L., & Pitts, V. E. (2010). Stealing time at work: Attitudes, social pressure, and perceived controls as predictors of time theft. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 53-67. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0249-z Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (1968). Theft act 1968. London: The National Archives. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/60/contents Huckfeldt, R., & Sprague, J. (1991). Discussant effects on vote choice: Intimacy, structure, and interdependence. The Journal of Politics, 53, 122-158. doi:10.2307/2131724 Hurd, N. M., Zimmerman, M. A., & Reischl, T. M. (2011). Role model behavior and youth violence: A study of positive and negative effects. Journal of Early Adolescen c e , 31, 323-354. doi:10.1177/0272431610363160 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 443  J. DE GROOT ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 444 Jacobson, R. P., Mortensen, C. R., & Cialdini, R. B. (2011). Bodies obliged and unbound: Differentiated response tendencies for injunc- tive and descriptive social norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 433-448. doi:10.1037/a0021470 Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Mähönen, T. A., & Liebkind, K. (2011). Ingroup norms, intergroup contact and intergroup anxiety as predictors of the outgroup attitudes of majority and minority youth. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 346-355. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.06.001 Kallgren, C. A., Reno, R. R., & Cialdini, R. B. (2000). A focus theory of normative conduct: When norms do and do not affect behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1002-1012. doi:10.1177/01461672002610009 Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2008). The Spreading of Disor- der. Science, 322, 1681-1685. doi:10.1126/science.1161405 Lapinski, M. K., & Rimal, R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication Theory, 15, 127-147. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00329.x Mulder, L. B., Verboon, P., & De Cremer, D. (2008). Sanctions and mo- ral judgments: The moderating effect of sanction severity and trust in authorities. E urope an Jo urnal of Social Psychology, 3 9, 255-269. doi:10.1002/ejsp.506 Nesdale, D., & Lawson, M. J. (2011). Social groups and children’s in- tergroup attitudes: Can school norms moderate the effects of social group norms? Child Development, 82, 1594-1606. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01637.x Nikitas, A., Avineri, E., & Parkhurst, G. (2011). Older people’s atti- tudes to road charging: Are they distinctive and what are the implica- tions for policy? Transportation Planning and Technology, 34, 87- 108. doi:10.1080/03081060.2011.530831 Piazza, J., Bering, J. M., & Ingram, G. (2011). Princess Alice is watch- ing you: Children’s belief in an invisible person inhibits cheating. Journal of Experimental Child Psycho lo gy , 109, 311-320. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2011.02.003 Posthuma, R. A., & Dworkin, J. B. (2000). A behavioural theory of ar- bitrator acceptability. International Journal of Conflict Management, 11, 249-266. doi:10.1108/eb022842 Research Development Statistics (RDS) (2011). Crime in England and Wales: Quarterly update to Septemb er 2010. London: Home Office. http://rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/whatsnew1.html Reno, R. R., Cialdini, R. B., & Kallgren, C. A. (1993). The transsitua- tional influence of social norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 104-112. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.1.104 Schultz, P. W., Khazian, A. M., & Zaleski, A. C. (2008). Using norma- tive social influence to promote conservation among hotel guests. Social Influence, 3, 4-23. doi:10.1080/15534510701755614 Schultz, P. W., & Tabanico, J. J. (2009). Criminal beware: A social norms perspective on posting public warning signs. Criminology, 47, 1201- 1222. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00173.x Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2007). God is watching you: Priming God concepts increases prosocial behavior in an anonymous eco- nomic game. Psychological Scienc e, 18, 803-809. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01983.x Terrade, F., Pasquier, H., Reerinck-Boulanger, J., Guingouain, G., & Somat, A. (2009). L’acceptabilité sociale: La prise en compte des de- terminants sociaux dans l’analse de l’acceptabilité des systems tech- nologiques. Le Travail Humain: A Bilingual and Multi-Disciplinary Journal in Human Factors, 72, 383-395. doi:10.3917/th.724.0383 Tonglet, M. (2002). Consumer misbehavior: An exploratory study of shoplifting. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 1, 336-354. doi:10.1002/cb.79 Visser, P. S., & Mirabile, P. R. (2004). Attitudes in the social context: The impact of social network composition on individual level atti- tude strength. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 779- 795. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.779 Wang, C., Chen. C., Yang, S., & Farn, C. (2009). Pirate or buy? The mo- derating effect of idolatry. Journal of B usin e ss Ethics, 90, 81-93. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0027-y Wenzel, M. (2004). The social side of sanctions: Personal and social norms as moderators of deterrence. Law and Human Behaviour, 28, 547-567. doi:10.1023/B:LAHU.0000046433.57588.71

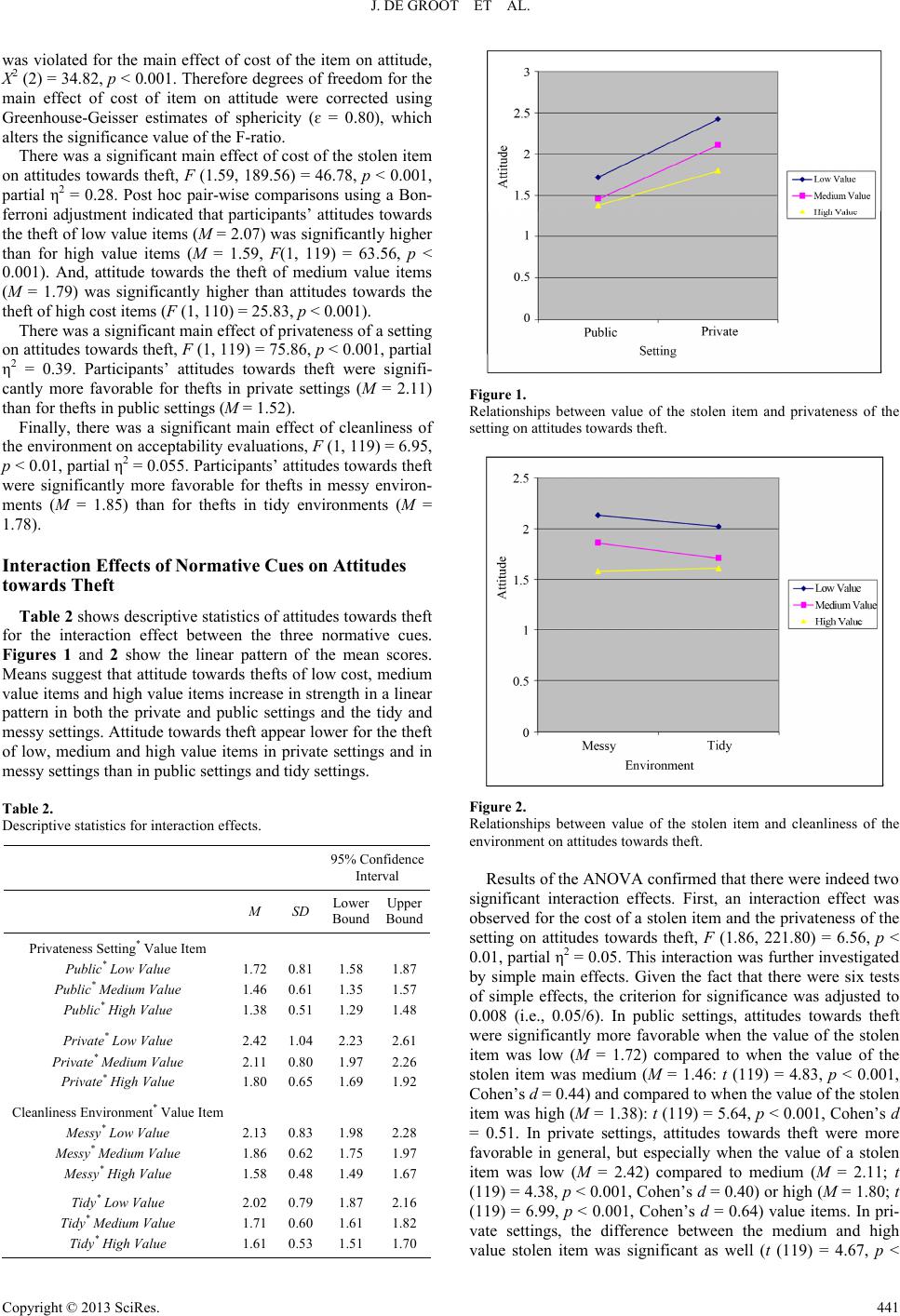

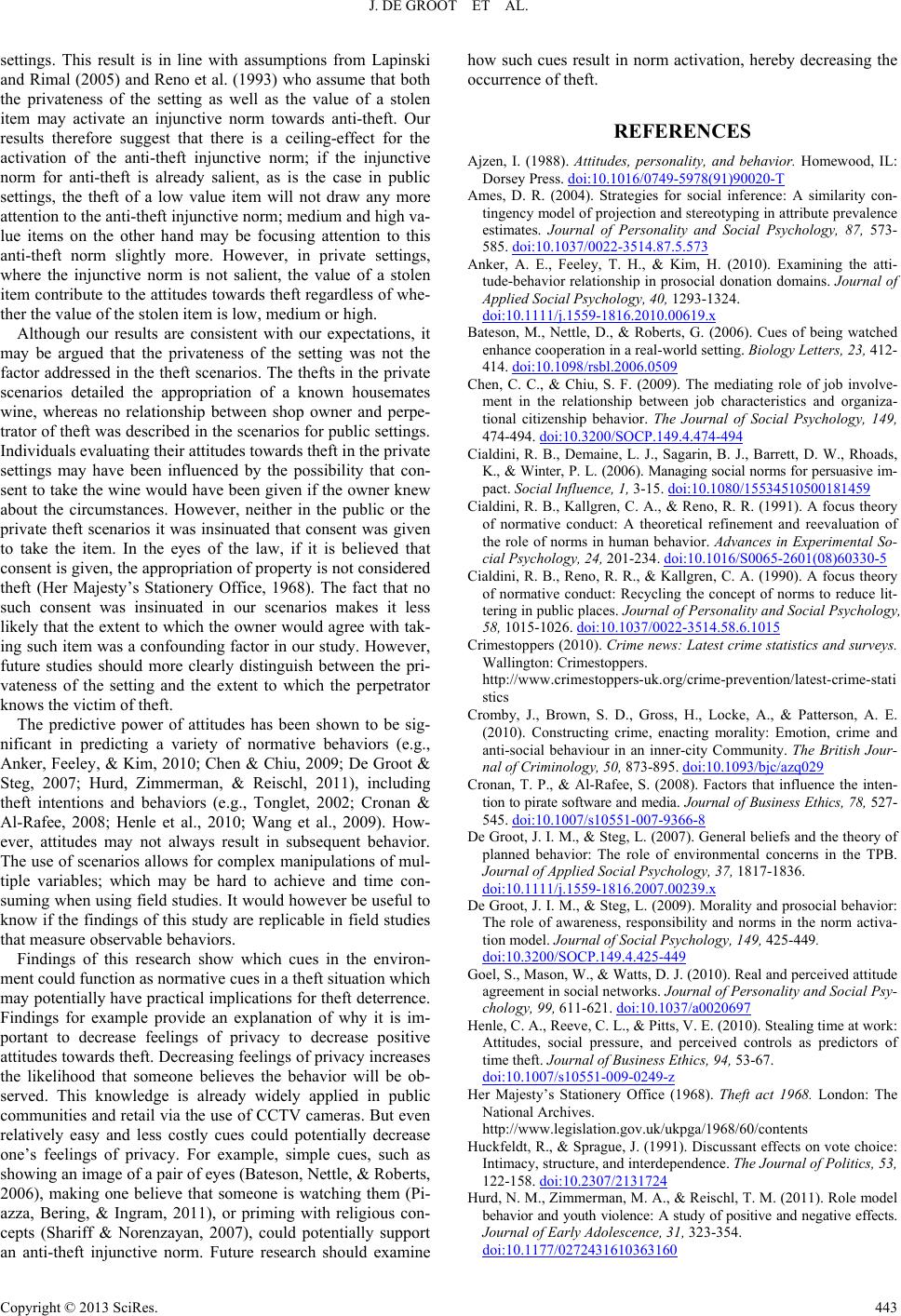

|