Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

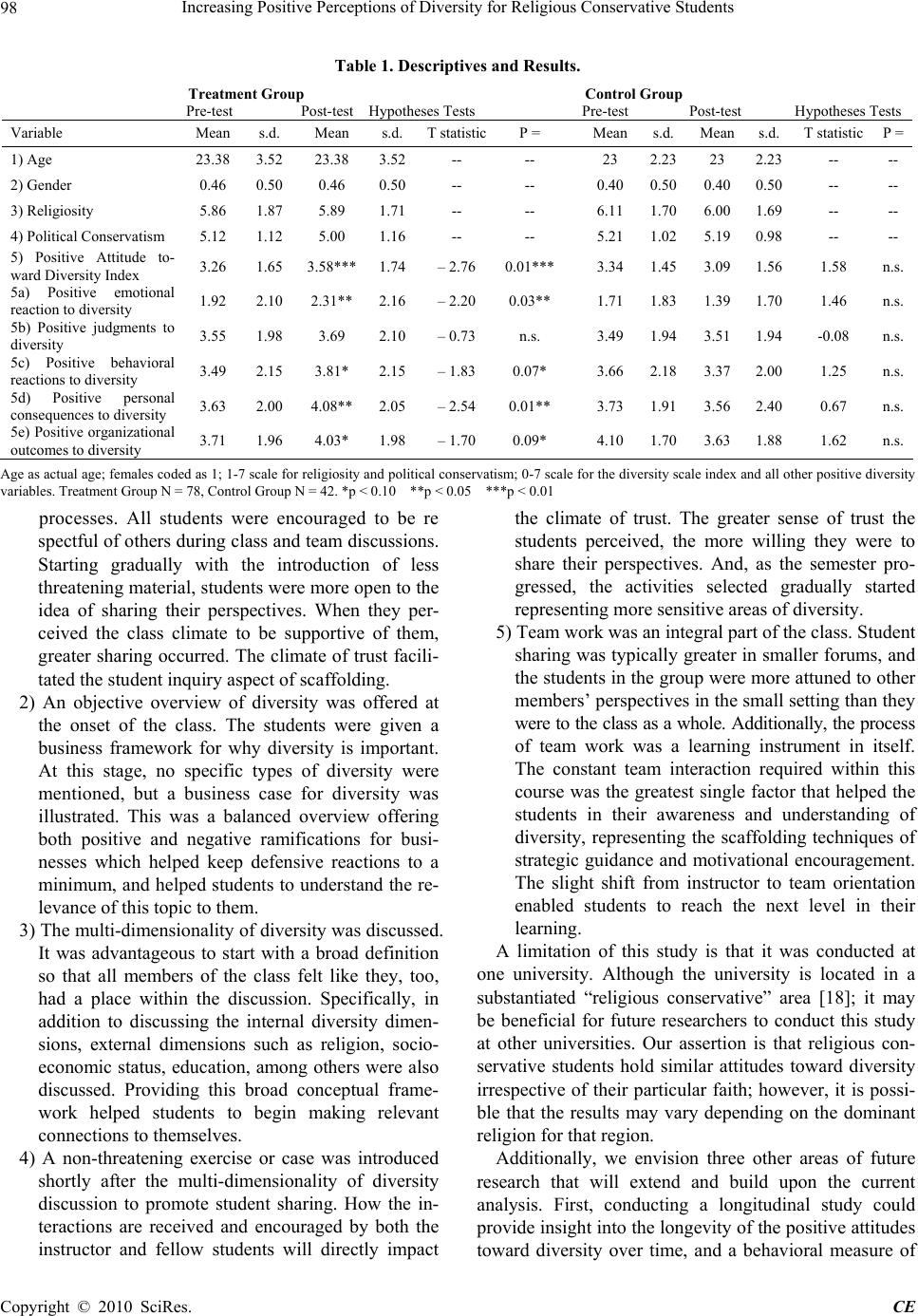

Creative Education, 2010, 2, 93-100 doi:10.4236/ce.2010.12014 Published Online September 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 93 Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Alison Cook, Ronda Roberts Callister Jon M. Huntsman School of Business Utah State University, Logan, USA Email: alison.cook@usu.edu, ronda.callister@usu.edu Received January 30th, 2010; revised July 19th, 2010; accepted July 25th, 2010. ABSTRACT Evidence suggests that positive perceptions toward diversity enhance the potential group and organizational benefits resulting from diversity. Given the make-up of today’s organizations, encountering diversity has become the norm ra- ther than the exception. As such, it is becoming increasingly important to address diversity issues, and take steps to increase positive perceptions of diversity within the business classroom in order to carry that advantage into the work- place. Religious conservative students present a unique challenge to diversity education in that they likely hold value- laden attitudes that lack alignment with diversity principles. This study prescribes a scaffolding approach to increase positive perceptions of diversity within a classroom comprised predominantly of religious conservative students. Keywords: Teaching Diversity, Positive Benefits of Diversity, Teaching Methods, Religious Conservative Students 1. Introduction Diversity is an important and complex issue for organiza- tions today, presenting both opportunities and challenges [1]. Though current research has asserted a number of potential benefits organizations may gain as a result of diversity [2-5], limitations exist that may inhibit organi- zations from reaching that potential [6-8]. Recent schol- arship suggests that positive perceptions of diversity may enhance the likelihood that diversity benefits will be achieved by the organization [6-8]. Specifically, both organization- and group-level bene- fits have been suggested as a result of individuals’ posi- tive perceptions of diversity [6-8]. Konrad and her col- leagues (2009) [7] argue that organizational benefits gained differ depending on your perception of diversity. If diversity practices are viewed as fulfilling an ethical and moral obligation only, then the potential benefits will not be realized. However, if diversity is viewed as a stra- tegic advantage to the firm, as a value-add for the or- ganization, the realization of potential benefits is probable. The argument is that value congruence is essential to diversity success. If individuals perceive diversity as a positive attribute to the firm, then value congruence is more likely to occur. This correlates with Schneider and Northcraft’s (1999) [8] assertion that by addressing the dilemmas of individual and managerial participation to- ward diversity, organizational benefits may be more im- mediately realized. Through greater positive perceptions of diversity and understanding of potential benefits, val- ue congruence will likely be enhanced, and the individual and managerial dilemmas will be reduced. At the group level, Ely and Thomas (2001) [6] found that groups with an integration-and-learning perspective, a perspective where diversity is positively perceived as a valuable re- source, were more highly functioning than the other stu- died groups. All groups were diverse in make-up; the differences existed in the perceptions held by members of the groups toward diversity. Positive perceptions re- sulted in greater productivity. Given the potential benefit for organizations when their employees hold positive perceptions about diversity, and the inevitability of encountering diversity in the workplace; it is essential that business classes not only address diversity, but work to increase positive percep- tions toward it. Research shows that although overt preju- dicial acts toward others may have decreased, discrimina- tion perseveres in society today [9,10]. It is suggested that some people, even though they support egalitarian principles and believe themselves to not be prejudiced, hold negative feelings about others [9]. Further, many only view diversity as a legal or ethical issue [11], yet given the organizational benefits possible, it is important that the business classroom works to shift the view of diversity to be positively perceived as a valuable re-  Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 94 source rather than simply a legal, ethical, or discrimina- tory issue. Our study makes an important contribution by offering guidelines for increasing positive perceptions of diversity within a classroom of predominantly religious conserva- tive students. Diversity education may be especially challenging with religious conservative students because the political positions of the religious right are typically less supportive of the principles of diversity. Scholars suggest it is difficult to make any real progress when the students are committed to their beliefs and disagree in principle with the ideals of diversity education [12,13]. Previous research has recognized the association of reli- gious denominations and beliefs with conservative atti- tudes particularly those regarding gender [14] and sexual orientation [15]. For example, Fundamentalist Protestants support traditional gender role attitudes using biblical passages portraying men as leaders and women as fol- lowers [16-18] and use the bible to argue that homosexu- ality is a sin. The United States is a religious country with 83% of the population reporting they are Christians and only 13% reporting no religion (ABC News, 2007). Defining religious conservatives is complicated both because of the large number of denominations in the U.S., almost 1200 by one estimate [19], and because many denomina- tions include a wide range of beliefs. But it is generally accepted that Protestant Fundamentalists who believe in a literal interpretation of the Bible are at the most con- servative end of the spectrum [18,20]. While white Evan- gelicals, Baptists and Mormons are less conservative than Protestant Fundamentalists, they are more conserva- tive than mainline Protestants [21,22], and can still be considered religious conservatives. Also, frequent church attendees tend to have more conservative gender attitudes even after controlling for denomination (Mason & Lu, 1988) [14]. Moore and Vanneman’s (2003) [18] study showed that the “Bible Belt” area of the U.S.—including the south and parts of the Midwest, in addition to Utah— were the areas with the highest proportions of religious conservatives, while most other areas of the U.S. have modest to significant numbers of religious conservatives. Given the potential benefits of diversity for organizations and the large number of students that have religious con- servative backgrounds, it is important that diversity edu- cation be structured in a way to influence the greatest number of students. The college years may be the ideal time to expose reli- gious conservative students to diverse perspectives and help them move toward broader perspectives-taking and increased understanding of differences. This period is frequently a time that significant social and moral devel- opment takes place as students become more aware of the social world in general and their place in it (Rest, 1986) [23]. Similarly, studies of faith development show that the college years are a common time of transition into a less literal belief system [24]. The impact of col- lege education on moral, social and faith development suggests that these changes may also benefit diversity education. We may be able to draw on the large body of research over the last 40 years of studies on moral de- velopment and moral education for guidance in how to teach diversity. “Kohlberg’s theory of moral develop- ment suggests that rather than attempt to indoctrinate or socialize students, moral education should seek to stimu- late the natural process of development toward more mature moral reasoning” [25]. There is evidence to sug- gest that making moral issues an integral part of the sub- ject matter by integrating dilemmas and role-taking ex- periences into the classroom are beneficial, as is being exposed to exemplars [26]. Education programs designed to stimulate moral judgment produce modest significant gains, particularly those programs that emphasize peer discussion of con- troversial dilemmas [23]. Diversity education is likely to parallel these findings. Moral development research suggests that the college classroom may be the ideal time to educate students about diversity using peer discussion that encourages broader perspective taking. The chal- lenge may be to find a way to present material about di- versity that allows these students to remain open to al- ternative perspectives. More specifically we examine the research question—If religious conservative students can be taught about diversity in a way that does not trigger strong or defensive reactions based on religious beliefs, will they show positive change in their attitudes toward diversity over the course of a semester? It may be that by finding a way to present material on diversity that allows engagement without defensiveness, the prospect of atti- tudinal change will be enhanced. 2. Methods 2.1. Study Participants Participants in the study were 120 students enrolled at a public university in a college town in Utah. Two organ- izational behavior courses with 78 students served as the treatment group and one human resources course with 42 students served as the control group. As illustrated in the descriptives table (refer to Table 1), the student body is composed largely of highly religious and politically con- servative individuals. Utah is notably conservative as is continually illustrated by political elections, and it has a prevailing dominant conservative religion. The average age in both the treatment and control groups was ap- proximately 23, and males represented a slightly larger  Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 95 proportion (56%) of the overall sample. 2.2. Procedure The two organizational behavior courses were taught by the same instructor, and the human resources course was taught by a different instructor. Both instructors were female and in their 30 s. Other than knowing her class was serving as a control group for an experiment, the human resources instructor was not given any other in- formation. Students in all classes were informed that the purpose of the study was to gain insight into their atti- tudes toward diversity. Included components were the pre-test questionnaire / exercise at the beginning of the 16-week semester and the post-test questionnaire / exer- cise at the end. IRB approval was acquired for all aspects of the study and student consent forms were collected. To lessen the potential of a social desirability bias occur- ring, all questionnaires were numbered and anonymous to the instructors. During the pre- and post-tests, students were asked to complete a “reaction-to-diversity” exercise. Within the diversity exercise, students were asked to circle all words that they associate with diversity. The number of words selected varied by student, and no “appropri- ate” number was suggested by the instructor. Addition- ally, religiosity and political conservatism were assessed by numerous survey items. To account for potential selection bias between the control and treatment groups, an independent samples t-test was conducted with the pretest scores. The results confirmed that no significant differences existed between the groups at the onset of the study. The instructor of the two organizational behavior classes purposefully structured the course for this ex- periment using scaffolding strategies. With higher per- centages of religious conservative students, resistance to diversity is likely to increase. Specifically, some students may feel their beliefs are being threatened, and when individuals feel threatened, they are less likely to be open to diversity [27]. As such, certain strategies for ap- proaching the subject may be helpful. In the year prior to the study, the organizational behavior course instructor collected journal entries from her students at the mid-term and conclusion of the class that detailed effec- tive strategies that were used to aid in their understanding and acceptance of diversity. These strategies, in turn, were incorporated into the planned structure for the ex- amined classes. The challenge in teaching diversity to religious con- servative students is to present material that does not trigger a defensive reaction, but connects on a level that they can find personal relevance and to engage them in higher effort cognitions where they will more likely be influenced. For example, in one of her first years, the instructor introduced a diversity case at the beginning of the course that included issues of race, gender, and sexual orientation. This case triggered strong defensive reac- tions from a large number of students. This may have occurred because the topics of gender and sexual orienta- tion are diversity issues with conflicting religious con- servative beliefs [15,18]. The following year that par- ticular case was not introduced until late in the semester and the diversity case introduced at the beginning of the class discussed a person’s weight and the potential biases that person may encounter. Weight, though it still may be a sensitive topic, is not as emotionally charged, and is something that students may see as being relevant to them at some point in their life or relevant to someone they currently know. Therefore, starting slowly with ma- terial that is personally relevant and does not contain issues that are strongly counter-attitudinal may help build a level of trust within the classroom; and in diversity education, a climate of trust is essential. The material is sensitive and students need to feel safe in expressing their perspective and questioning others’ perspectives. Scaffolding, though primarily used in K-12 education, is fitting for diversity education in that its purpose is to promote student inquiry, assist conceptual learning, ad- dress misconceptions, and encourage reflective thinking [28]. It is an approach taken by the instructor or peer that offers support, as needed, to help the students participate meaningfully [29]. Instructors must continually assess what support is needed to achieve the desired result and provide the appropriate amount at the right time. Scaf- folding techniques in the examined classes were to pro- vide students with the conceptual framework, guide the cognitive processes when needed, and provide strategic guidance in how to effectively approach the issues [28-30]. This technique was used in order to shift the ownership of learning and discovery to the students. Given the religiosity and political conservatism of the students examined and the probability of unfavorable diversity attitudes being present within the group, these techniques served to aid in student learning. First, providing a conceptual framework was a neces- sary scaffolding technique in order to help the students know what to consider and what to evaluate. The goals for integrating this material into the course were clear; the instructor wanted to increase student awareness and expand student understanding of diversity. Through pre- vious journal entries, several students noted the impor- tance of having both the explicit knowledge provided by the discussion and the tacit knowledge provided by the applied activities. Thus, the class was structured to in- corporate both theory and application. The theoretical frameworks were supported with current research findings and implications, and the applications were used to aug-  Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 96 ment the discussions and took the forms of case studies, simulations, exercises, and group work. To increase the effectiveness of scaffolds, students should readily understand how the material relates to them [29]. Therefore, the second step was to illustrate why they should care about diversity and to provide them with concrete ideas as to why it is important. This step occurred within the first week of class. Research was introduced that supports the business case for diversity and the value-in-diversity perspective. A rationale was provided to the students as to why this is an important topic that warrants further investigation and study. The third step connecting this topic to the students was the discussion of the multi-dimensionality of diversity which occurred the following week. Specifically, surface and deep-level diversity were discussed. Surface-level diver- sity is the easily identified differences such as gender and race; and deep-level diversity is the less identifiable dif- ferences such as values and personality. This discussion is especially important with a group of students that may not hold favorable attitudes toward diversity. By illus- trating the broad scope of diversity, a greater sense of inclusion is created. This broad discussion early in the semester was introduced to lower the defensiveness of the students and increase the likelihood that they would engage in the discussions. The fourth step focused on guiding the students’ cog- nitive processes and encouraging the students to become active participants. After the discussion of the mul- ti-dimensionality of diversity, a case based on weight (a non-threatening case) was introduced. With the case in- troduction, students become engaged in the learning process and the emphasis shifts to encouraging class members to share their perspectives. This sharing of perspectives offers an effective scaffold for class learning. And as affirmed through previous students’ journal en- tries, hearing others’ views and thoughts helped in their awareness and understanding of diversity. This step was intensified as the semester progressed. Case studies, si- mulations, and other applied activities became more tar- geted toward issues of gender, race, and sexual orienta- tion throughout the semester. As the level of trust in- creased and the climate of acceptance grew, student sharing and disclosure became greater. The last primary component of the class structure was inter-group contact. Strategic support and motivational encouragement were the scaffolds provided by the in- structor if needed, but the primary learning was occurring within the groups and their interaction. Although the classes were quite homogeneous, group interactions facilitated student awareness of their own identity and that of the other group members. This step was the most reported component by the students for helping them in the awareness and understanding of diversity. Teams were formed at the onset of the class and students were required to complete an overall course project and pre- sentation as well as numerous team activities throughout the semester. This constant group interaction created a comfort level within the teams that enabled all students to voice their perspectives within the small group discus- sions. Often students are not comfortable discussing some of their views with the entire class, but will share their perspectives within their team. The primary com- ponents used to teach diversity in a management class may not vary greatly between a class with and a class without a strong religious conservative contingent; how- ever, teaching diversity to religious conservative students requires increased attention to subtle details for success because of the higher risks of triggering negative defen- sive reactions. 2.3. Measures Items on the “reaction-to-diversity” exercise were drawn from De Meuse and Hostager’s (2001) [31] instruments to measure attitudes toward diversity. Given our purpose was to examine shifts in positive reactions toward diversity, we focused on the 35 positive words within the diversity exercise. The words were randomly placed with the 35 words representing five different variables of positive reactions. The five positive constructs measured were emotional reactions, judgments, behavioral reactions, personal consequences, and organizational outcomes. Each of the constructs is composed of seven terms. Spe- cifically, the terms compassionate, enthusiastic, excited, grateful, happy, hopeful, and proud compose the variable emotional reactions. The terms composing judgments are ethical, fair, good, justified, proper, sensible, and useful. Behavioral reactions consists of collaborate, cooperate, friendly, listen, participate, support, and understand. The personal consequences construct includes advancement, discovery, enrichment, merit, opportunity, rewarding, and wisdom. And asset, harmony, innovation, profitable, progress, team-building, and unity compose positive or- ganizational outcomes. Scores were computed for the participants by counting the number of words chosen within each category. The measures were scored on a scale from zero to seven. For example, if they did not select any of the words within the given construct, they were awarded a zero for that measure. If they selected all seven of the words within the given construct, they were awarded a seven. The positive attitudes toward diversity index were created by summing the diversity dimensions described above and dividing the score by five to remain on a 0-7 scale. We created this index in order to provide a comprehensive picture of the students’ overall attitude toward diversity. The coefficient alpha for the pre-test  Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 97 index is 0.85 and for the post-test index is 0.89. Age was entered in all analyses as the actual age, and gender was coded as 1 for females and 0 for males. We used three items from Sullivan (2001) [32] which was based upon the religiosity measure developed by Rohr- baugh and Jessor (1975) [33] for our religiosity measure. Representative items are “Religious beliefs are not at all important in my everyday life” and “I am definitely a religious person” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Items were aligned so the higher number reported represents greater religiosity. To create the religiosity variable, the items were summed and then divided by three to remain on a 1-7 scale. Coefficient alphas are 0.95 for the pre-test and 0.88 for the post-test. Political conservatism was measured with 9 items that were based on Wilson and Patterson’s (1968) [34] scale of conserva- tism. Specific items were updated using Collins and Hays (1993) [35] and Henningham (1996) [36]. Representative items are “I believe in legalized abortion” and “Religions should allow women clergy” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Items representing conservative and lib- eral positions were alternated in the scale and items were aligned so the higher number reported represents greater political conservatism. To create the political conserva- tism variable, the items were summed and then divided by 9 to remain on a 1-7 scale. Coefficient alphas are .86 for the pre-test and post-test. 3. Results Descriptive statistics and t-test results for the treatment group and the control group are presented in Table 1. T-tests were performed to examine differences between the pre- and post-test positive attitudes of diversity index score and also to examine differences between the sub- scale scores of the diversity dimensions composing the index. Findings indicate that there were indeed signifi- cant increases in positive perceptions of diversity occur- ring within the treatment group while no significant changes were realized in the control group. Our research question asked if it was possible to in- crease positive perceptions of diversity for religious conservative students. This was tested by conducting a repeated measures general linear model which compared students’ positive attitudes toward diversity scores by pre-test versus post-test and by treatment group versus control group. Results indicate that significant positive changes in students’ attitudes toward diversity occurred in the treatment group but not in the control group (refer to Table 1). Specifically, the overall positive attitudes toward diversity index showed a significant mean change (p < 0.01) from the pre- to post-test of 3.26 to 3.58 for the treatment group, but the mean change for the control group was non-significant. Findings, though, do suggest a decreasing trend of positive attitudes toward diversity for the control group with means reported as 3.34 for the pre-test and 3.09 for the post-test. T-test analyses of the individual dimensions affirmed the findings. The treatment groups’ mean changes sig- nificantly increased for all dimensions except positive judgments (a n.s. positive increase) while the control groups’ mean changes remained non-significant (refer to Table 1). Specifically, the dimension of emotional reac- tion showed a significant mean change (p = 0.03) from the pre- to post-test of 1.92 to 2.31, the dimension of personal consequences showed a significant mean change (p = 0.01) from the pre- to post-test of 3.63 to 4.08, the dimension of organizational outcomes showed a significant mean change (p = 0.09) from the pre- to post-test of 3.71 to 4.03, and the dimension of behavioral reactions showed a significant mean change (p = 0.07) from the pre- to post-test of 3.49 to 3.81. These results suggest that there was a significantly positive shift in overall attitudes toward diversity for the treatment group. 4. Discussion This study makes a contribution by demonstrating that religious conservative students can be positively influ- enced by diversity education. Although these students present a unique challenge to diversity education, the college classroom has the potential to help students gen- erate their own perspectives through engaging more deeply with others’ views. This study also makes a con- tribution by developing theoretical explanations for why these improved attitudes develop. We draw on the litera- tures on moral, social and faith development to show that college years are a time when students are likely to ex- perience increases in perspective taking ability [23,24,37]. Because of the increases in perspective taking that often occur in college, we suggest that this period may be an ideal time to introduce diversity to religious conservative students who may not have had much pre- vious exposure to either diverse people or ideas. Group work had the most positive impact on our reli- gious conservative students’ attitudes toward diversity which fits well with the moral development findings that peer discussions have shown a positive impact on in- creases in perspective taking. We put forth the following scaffolding strategies that appear to positively influence students when teaching diversity. 1) A climate of trust must be established. This was accomplished by encouraging all student input, and being supportive of them through their thought  Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 98 Table 1. Descriptives and Results. Treatment Group Control Group Pre-test Post-test Hypotheses Tests Pre-test Post-test Hypotheses Tests Variable Mean s.d. Mean s.d.T statisticP = Means.d. Mean s.d. T statisticP = 1) Age 23.383.52 23.38 3.52-- -- 23 2.23 23 2.23 -- -- 2) Gender 0.46 0.50 0.46 0.50-- -- 0.400.500.40 0.50 -- -- 3) Religiosity 5.86 1.87 5.89 1.71-- -- 6.111.706.00 1.69 -- -- 4) Political Conservatism 5.12 1.12 5.00 1.16-- -- 5.211.025.19 0.98 -- -- 5) Positive Attitude to- ward Diversity Index 3.26 1.65 3.58*** 1.74– 2.76 0.01*** 3.341.453.09 1.56 1.58 n.s. 5a) Positive emotional reaction to diversity 1.92 2.10 2.31** 2.16– 2.20 0.03** 1.711.831.39 1.70 1.46 n.s. 5b) Positive judgments to diversity 3.55 1.98 3.69 2.10– 0.73 n.s. 3.491.943.51 1.94 -0.08 n.s. 5c) Positive behavioral reactions to diversity 3.49 2.15 3.81* 2.15– 1.83 0.07* 3.662.183.37 2.00 1.25 n.s. 5d) Positive personal consequences to diversity 3.63 2.00 4.08** 2.05– 2.54 0.01** 3.731.913.56 2.40 0.67 n.s. 5e) Positive organizational outcomes to diversity 3.71 1.96 4.03* 1.98– 1.70 0.09* 4.101.703.63 1.88 1.62 n.s. Age as actual age; females coded as 1; 1-7 scale for religiosity and political conservatism; 0-7 scale for the diversity scale index and all other positive diversity variables. Treatment Group N = 78, Control Group N = 42. *p < 0.10 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01 processes. All students were encouraged to be re spectful of others during class and team discussions. Starting gradually with the introduction of less threatening material, students were more open to the idea of sharing their perspectives. When they per- ceived the class climate to be supportive of them, greater sharing occurred. The climate of trust facili- tated the student inquiry aspect of scaffolding. 2) An objective overview of diversity was offered at the onset of the class. The students were given a business framework for why diversity is important. At this stage, no specific types of diversity were mentioned, but a business case for diversity was illustrated. This was a balanced overview offering both positive and negative ramifications for busi- nesses which helped keep defensive reactions to a minimum, and helped students to understand the re- levance of this topic to them. 3) The multi-dimensionality of diversity was discussed. It was advantageous to start with a broad definition so that all members of the class felt like they, too, had a place within the discussion. Specifically, in addition to discussing the internal diversity dimen- sions, external dimensions such as religion, socio- economic status, education, among others were also discussed. Providing this broad conceptual frame- work helped students to begin making relevant connections to themselves. 4) A non-threatening exercise or case was introduced shortly after the multi-dimensionality of diversity discussion to promote student sharing. How the in- teractions are received and encouraged by both the instructor and fellow students will directly impact the climate of trust. The greater sense of trust the students perceived, the more willing they were to share their perspectives. And, as the semester pro- gressed, the activities selected gradually started representing more sensitive areas of diversity. 5) Team work was an integral part of the class. Student sharing was typically greater in smaller forums, and the students in the group were more attuned to other members’ perspectives in the small setting than they were to the class as a whole. Additionally, the process of team work was a learning instrument in itself. The constant team interaction required within this course was the greatest single factor that helped the students in their awareness and understanding of diversity, representing the scaffolding techniques of strategic guidance and motivational encouragement. The slight shift from instructor to team orientation enabled students to reach the next level in their learning. A limitation of this study is that it was conducted at one university. Although the university is located in a substantiated “religious conservative” area [18]; it may be beneficial for future researchers to conduct this study at other universities. Our assertion is that religious con- servative students hold similar attitudes toward diversity irrespective of their particular faith; however, it is possi- ble that the results may vary depending on the dominant religion for that region. Additionally, we envision three other areas of future research that will extend and build upon the current analysis. First, conducting a longitudinal study could provide insight into the longevity of the positive attitudes toward diversity over time, and a behavioral measure of  Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 99 diversity acceptance could be developed to assess the effectiveness of transferring the positive attitudes ac- quired to positive behaviors. Second, research is needed to determine effective methods for managing extreme polar positions within classroom discussions and activi- ties of diversity. And last, it would be beneficial for fu- ture research to differentiate between students who are new to the concepts of diversity and students with preex- isting biases toward diversity. This study’s population primarily encompassed those students new to diversity. Most are from homogeneous environments without much exposure to diversity and often do not realize what their biases may be. Other students from heterogeneous envi- ronments may enter class with established diversity biases. Both sets of students present challenges, but they may respond differently to diversity efforts. As such, more research is necessary to understand the back- grounds of our students, and how to effectively integrate those backgrounds into the methodology for teaching diversity. The research suggested would complement the current study by providing a more comprehensive under- standing of diversity teaching methods and potential outcomes for the students. REFERENCES [1] J. R. W. Joplin and C. S. Daus, “Challenges of Leading a Diverse Workforce,” Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1997, pp. 32-47. [2] D. D. Frink, R. K. Robinson, B. Reithel, M. M. Arthur, A. P. Ammeter, G. R. Ferris, D. M. Kaplan and H. S. Mor- risette, “Gender Demography and Organization Perform- ance: A Two-Study Investigation with Convergence,” Group and Organization Management, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2003, pp. 127-147. [3] L. S. Hartenian and D. E. Gudmundson, “Cultural Diver- sity in Small Business: Implications for Firm Perform- ance,” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2000, pp. 209-220. [4] O. C. Richard, T. Barnett, S. Dwyer and K. Chadwick, “Cultural Diversity in Management, Firm Performance, and the Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation Dimensions,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, No. 2, 2004, pp. 255-266. [5] O. C. Richard and N. B. Johnson, “Understanding the Impact of Human Resource Diversity Practices on Firm Performance,” Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 13, 2001, pp. 177-196. [6] R. J. Ely, “A Field Study of Group Diversity, Participa- tion in Diversity Education Programs, and Performance,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 25, No. 6, 2004, pp. 755-780. [7] A. M. Konrad, Y. Yang and C. Maurer, “Strategic Diver- sity Management: A Configurational Approach to Diver- sity-Related HRM Practices,” Presented at Wilfrid Laurier University Speaker Series, February, 2009. [8] S. K. Schneider and G. B. Northcraft, “Three Social Di- lemmas of Workforce Diversity in Organizations: A So- cial Identity Perspective,” Human Relations, Vol. 52, No. 11, 1999, pp. 1445- 1467. [9] J. F. Dovidio and S. L. Gaertner, “Affirmative Action, Unintentional Racial Biases, and Inter-Group Relations,” Journal of Social Issues,” Vol. 52, No. 4, 1996, pp. 51-75. [10] K. Kawakami, E. Dunn, F. Karmali and J. F. Dovidio, “Mispredicting Affective and Behavioral Responses to Racism,” Science, Vol. 323, No. 5911, 2009, pp. 276-278. [11] S. Brammer, G. Williams and J. Zinkin, “Religion and Attitudes to Corporate Social Responsibility in a Large Cross-Country Sample,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 71, No. 3, 2006, pp. 229-243. [12] R. J. Ely and D. A. Thomas, “Cultural Diversity at Work: The Effects of Diversity Perspectives on Work Group Processes and Outcomes,” Administrative Science Quar- terly, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2001, pp. 229-273. [13] P. L. Nemetz and S. L. Christensen, “The Challenge of Cultural Diversity: Harnessing a Diversity of Views to Understand Multiculturalism,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1996, pp. 434-462. [14] K. O. Mason and L. L. Bumpass, “U. S. Women’s Sex- Role Ideology,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 80, No. 5, 1975, pp. 1212-1219. [15] C. G. Ellison and M. A. Musick, “Southern Intolerance: A Fundamentalist Effect?” Social Forces, Vol. 72, No. 2, 1993, pp. 379-98. [16] N. T. Ammerman, “Bible Believers: Fundamentalists in the Modern World,” Rutgers University Press, New Jer- sey, 1987. [17] M. L. Bendroth, “Fundamentalism and Gender, 1875 to the Present,” Yale University Press, Connecticut, 1993. [18] L. M. Moore and R. Vanneman, “Context Matters: Ef- fects of the Proportion of Fundamentalists on Gender At- titudes,” Social Forces, Vol. 82, No. 1, 2003, pp. 115- 139. [19] J. G. Melton, “A Directory of Religious Bodies in the United States,” Garland, New York, 1977. [20] T. W. Smith, “Classifying Protestant Denominations,” Review of Religious Research, Vol. 31, No. 3, 1990, pp. 225- 245. [21] M. B. Brinkerhoff, J. C. Jacob and M. M. MacKie, “Mormonism and the Moral Majority Make Strange BedFellows?” Review of Religious Research, Vol. 28, No. 3, 1987, 236-271. [22] C. Wilcox, “Fundamentalists and Politics: An analysis of the Effects of Differing Operational Definitions,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 48, No. 4, 1968, pp. 1041-1051. [23] J. R. Rest, “Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory,” Praeger, Boston, 1986. [24] J. W. Fowler, “Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Hu- man Development and the Quest for Meaning,” Harper,  Increasing Positive Perceptions of Diversity for Religious Conservative Students Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 100 San Francisco, 1995. [25] L. Rosenzweig, “Kohlberg in the Classroom: Moral Edu- cation Models,” In: B. Munsey, Ed., Moral development, moral education, and Kohlberg: Basic Issues in philoso- phy, psychology, religion, and education, Religious Edu- cation Press, Birmingham, 1980, pp. 359-380. [26] D. Christiansen, D. Rees and J. Barnes, “How to Develop Resolve to Have Moral Courage,” Working Paper, 2007, South Utah University. [27] K. V. D. Zee and G. V. Der, “Personality, Threat and Affective Responses to Cultural Diversity,” European Journal of Personality, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2007, pp. 453-470. [28] K. D. Simons and P. A. Ertmer, “Scaffolding Disciplined Inquiry in Problem-Based Learning Environments,” In- ternational Journal of Learning, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2005, pp. 297- 305. [29] B. R. Belland, K. D. Glazewski and J. C. Richardson, “A Scaffolding Framework to Support the Construction of Evidence-Based Arguments among Middle School Stu- dents,” Educational Technology Research and Develop- ment, Vol. 56, No. 4, 2008, pp. 401-422. [30] X. Ge and S. M. Land, “A Conceptual Framework for Scaffolding Ill-Structured Problem-Solving Processes Using Question Prompts and Peer Interactions,” Educa- tional Technology Research and Development, Vol. 52, No. 2, 2004, pp. 5-22. [31] K. P. D. Meuse and T. J. Hostager, “Developing an In- strument for Measuring Attitudes toward and Perceptions of Workplace Diversity,” Human Resource Development Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2001, pp. 33-51. [32] K. T. Sullivan, “Understanding the Relationship between Religiosity and Marriage: An Investigation of the Imme- diate and Longitudinal Effects of Religiosity on Newly- wed Couples,” Journal of Family Psychology, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2001, pp. 610- 626. [33] J. Rohrbaugh and R. Jessor, “Religiosity in Youth: A Personal Control against Deviant Behavior,” Journal of Personality, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 153-169. [34] G. D. Wilson and J. R. Patterson, “A New Measure of Conservatism,” British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 7, No. 4, 1986, pp. 264-269. [35] D. M. Collins and P. F. Hayes, “Development of a Short-Form Conservatism Scale Suitable for Mail Sur- veys,” Psychological Reports, Vol. 72, No. 2, 1993, pp. 419- 422. [36] J. P. Henningham, “A 12-Item Scale of Social Conserva- tism,” Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 20, No. 4, 1996, pp. 517-519. [37] L. Kohlberg, “A Current Statement on Some Theoretical Issues,” In: S. Modgil and C. Modgil, Eds, Lawrence Kohlberg: Consensus and Controversy, Falmer, Phildel- phia, 1985, pp. 485-546. [38] Poll: Most Amer Cans Say they are Christians, 2007. http://abcnews.go.com/sections/us/DailyNews/ |