Journal of Service Science and Management

Vol.5 No.2(2012), Article ID:19187,8 pages DOI:10.4236/jssm.2012.52016

State of Content: Healthcare Executive’s Role in Information Technology Adoption

![]()

1School of Engineering, Ozyegin University, Istanbul, Turkey; 2School of Business, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Camden, USA; 3Eller College of Management, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA.

Email: neset.hikmet@ozyegin.edu.tr, snehamy@camden.rutgers.edu, mburns@cmi.arizona.edu

Received January 30th, 2012; revised March 9th, 2012; accepted March 19th, 2012

Keywords: Healthcare IT; IT Adoption; Healthcare Executives and IT

ABSTRACT

Over the past 30 years, researchers have demonstrated that health care information technology (HIT) can improve patient safety and quality of care. More recently, attention has turned increasingly to the role of information and communication technology as a means to improve clinical decision-making as well as organizational efficiency and effectiveness. Despite these streams of research, there is a lack of investigation that look at why and how health care executives leverage HIT. In this paper, the researchers investigate factors that may have an impact on health care executives’ intentions to further adopt HIT in their workplace. The analysis of collected data suggests that these factors play a significant role in increased HIT adoption in the future.

1. Introduction

The role of information technology (IT) as a catalyst to streamline business operations and improve productivity and efficiencies is globally accepted [1]. However, in spite of such acceptance, the degree of IT adoption among different industries varies greatly. The health care field, especially hospitals, is among the slowest institutions to integrate IT; about 10% of US hospitals have truly integrated health information systems [2]. While other industries average about 12% of their annual operating budget on IT related expenses, health care organizations allocate around 3% to 4%. As a result, there has been an increasing focus on the potential efficiencies that may be realized by successful implementation of HIT. The US Government, in a study conducted by the Office of Technology Assessment, stressed the need for assessing the effect of technology on the delivery of health care services [3] and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [4] stressed the importance to understand the influences of organizational factors on the adoption of new HIT.

It has been argued that proper use of information technology would be instrumental in reducing the cost of delivery of health care, increasing the quality of service, and improving the overall performance of the health care organization. In the US, health care expenditures have always been major component of Gross Domestic Product: in 2001 national health expenditures were $1424.5 trillion or 14.1 percent of GDP and these costs are expected to rise steadily to represent 16.8 percent of GDP by 2010. However, despite clear benefits such as improved staff productivity and reduced error rates, health care information technologies (HIT) such as computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems, electronic prescriptions, and disease management databases are not yet widely accepted in the medical community [2]. Even though the researchers yet to concur on how to assess and attribute the impact of the IT investment dollars with respect to the output measurement(s) under consideration; increased profits, reduced error rates, improved service quality, etc. [5], many are inclined to assume that more IT means better outcomes. This inclination especially has been the mindset of the US Government for many years [6].

It has been argued that relatively limited investment in the HIT has been the result of multitude of unsettling concerns; misaligned financial incentives, hampered by the high cost of initial investment in HIT systems, the limited available data on how HIT improves important outcomes, potentially disruptive effects on clinical workflow, cultural barriers, and competing priorities. Thus, from an executive’s vantage point little is known about the relationships between HIT and financial or other economic aspects of healthcare operations and service delivery processes and to what extend such relationships would impact their organization’s effectiveness. Predicament faced by the executives is further complicated by the fact that investing in IT does also necessitate organizations to undertake business process management activities and such transformations precipitate positive gains in many processes that are impacted on the way [7].

This paper examines the role of organizational as well as individual factors as antecedents for the attitude formation of health care executives. Understanding the process is critical since executives decisions can be influenced by their experiences and beliefs. In their study Johnson and Lederer [8] demonstrate that even though many executives agree on the importance of IT within the organization, they would significantly differ in opinion when asked to identify the magnitude of IT’s role and how much priority should it receive with respect to other outlay consideration. This dissent in IT’s perceived role in an organization is therefore induced into the investment decision process by the executive. The resource allocation for meeting the guidelines set forth by an organization’s operational structure as well as the guidelines set by accrediting and licensing agencies is very challenging for health care organizations. Thus, financial considerations play a major role in HIT investments. Executives represent the smallest group of IT users within the organization; additionally, they spend very little time making use of IT [9]. This deficiency in individual IT involvement and limited use of the many features of IT and/or the lack of understanding the role of such applications in day-to-day operations of the hospital may impact the executive’s attitude formation towards HIT. Since executives represent a major voice in the financial decision-making process in health care organizations, we investigate the underlying factors that can impact the attitudes of these key decision makers to HIT investment.

2. Prior IT Usage Research

Even though there has been considerable attention given to the use of HIT among health care practitioners, there has been a little attention given to the HIT use practices of the executives. In a health care setting, there is a duality of IT existence: the first, general-purpose applications such as spreadsheets, databases, web browsers, control systems, etc., and the second, very domain-specific application, such as EMR (electronic medical records), CPOE (computerized patient order entry), telemedicine, etc. [10]. Thus, understanding the behavior and factors that motivate the executive, is critical for successful integration of HIT with the operational and strategic IT in order to achieve an overall system efficiency.

Previous research done by [11-14] demonstrates the multiplicity and the complexity of the issues related to information technology use. These researchers were able to identify the varying impact of three major groups of factors on the adoption of information technology among different types of businesses. These factors were grouped as: 1) External factors, 2) Internal factors, and 3) Individual factors. For this study, we investigate certain individual factors (executives’ perceptions) as independent variables, and the executives’ behavioral intention to adopt HIT, beyond the current state of IT diffusion in the organization, as the dependent variable while controlling for organizational factors.

2.1. Organizational Factors

A review of literature suggests that HIT can improve the overall quality, performance and efficiency in hospitals. Many researchers report that increased use of HIT helps to reduce medical errors [15,16], improve time management and especially streamline document management [17,18], along and improve financial performance [19, 20]. As the literature regarding IT benefits has evolved, research has also begun to focus on the factors that relate to the adoption of IT by hospitals. For example, published evidence [21] suggests that large hospitals and hospitals with not-for-profit tax status tend to invest in HIT more readily. In another study, Hikmet and Bhattacherjee [22] demonstrated that facilities attaining professional certification had higher rate of HIT usage. Even though records management and process documentation guidelines defined by Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) did not mandate IT use, larger hospitals had higher IT intensity when compared to smaller facilities. Thus, we have included number of employees, hospital tax status, JCAHO certification as control variables in this study.

2.2. Theory and Hypotheses

Why people accept or reject information technology is an intriguing topic for academicians and has attracted a great deal of attention from a variety of disciplines. Rogers’ [23] diffusion theory offers us some insight in understanding how adopting innovative changes is affected in organizations. Based on diffusion theory, the personal characteristics of the individual and the perceived characteristics of innovation have an impact on the individual’s adoption of information technology. In an effort to understand the user acceptance of computer technology, researchers have studied the significance of users’ beliefs and attitudes [24,25] and how these internal beliefs and attitudes impact their continued use of information technology [26]. Individual factors such as perceived usefulness, satisfaction, subjective norms, and behavioral intentions can be critical in defining the success of information technology adoption in organizations [27]. Thus we posit that:

H1: There is a positive relationship between executives’ perceived usefulness of HIT and their consideration for further HIT adoption.

The first hypothesis is based on the Technology Acceptance Model [27]. The Technology Acceptance Model posits that perceived usefulness is of primary relevance for computer acceptance behaviors. In our study, perceived usefulness is further anchored on Bandura’s [28] outcomes expectation dimension. According to Bandura, the expectancy-value theory predicts that the higher the expectancy that certain behavior can secure specific out comes (i.e. using IT more than the current use level) and the more highly those outcomes are valued (e.g. will further improve efficiency), the greater the motivation is to perform the activity (i.e. further invest in IT). This argument is an important one since the executive’s decision on allocation of funds for certain investments (MRI or IT) may have a significant impact on the overall outcome measures that hospitals are judged by. In other words, which of the two investments, new MRI equipment or an upgrade to existing EHR, should receive priority?

H2: Subjective norms have a positive effect on executives’ consideration for further HIT adoption.

Subjective norms have been widely used in literature as a factor in attitude formation [29,30] and as a predictor of behavioral intention (for example, [23,28]). In the context of this study, a subjective norm is generated by the normative beliefs the executive attributes to what his/her peers expect him/her to do with respect to increased adoption of HIT in the hospital.

H3: Satisfaction with organizational HIT environment will have a positive effect on executives’ consideration for further HIT adoption.

This hypothesis is driven from studies done by Wixom and Todd [31] and Bhattacherjee [32] that in addition to the earlier studies that in support the role of satisfaction in system design [25,33,34], there is a parallel role for satisfaction as an antecedent for continued IT use. In our study, this role manifests itself as a proxy for the degree of satisfaction with the available technology as well as the support provided within the hospital the executive is in charge of.

In summary, the dependent variable of interest to this study is the extent of hospital executive’s intention to adopt HIT to a greater extent, and the three independent variables are perceived usefulness of IT, satisfaction with the organizational IT, and subjective norms. The hypothesized associations between the dependent and independent variables were empirically tested using a field survey, as described below.

3. Research Method

3.1. Operationalization of Construct

Measures were developed after reviewing the extant academic and trade literatures related to information technology use in organizations and from field interviews with healthcare executives. Multi-item scales were developed for each of the variables included in our research questions. For dependent variables we developed multidimensional constructs for executives’ intent to adopt HIT based on attitude towards IT and behavioral intent. Out three independent variables represent contextual factors deemed to influence an executives’ decision to invest in HIT. These measures are also composite indexes derived from multi-item scales related to each of these contextual factors based on the literature discussed above. Prior to assessing construct validity of our multiitem scales, the retained cases were examined for the presence of missing values.

3.2. Study Context and Sample

Empirical data for hypotheses testing were collected from a nationwide mail survey of healthcare administrators in the US The sampling frame consisted of a list of healthcare organizations purchased from a list broker that specialized in healthcare mailing lists. This list included the name, address, and type (e.g., hospital, long-term care, etc.) of healthcare facilities throughout the US, along with the names, addresses, phone numbers, and titles of senior executives (e.g., chief executive officers, presidents, IT managers) in those organizations. Using a two-stage stratified sampling technique, we first categorized our sampling frame into three strata based on facility type: hospitals, long term care facilities (nursing homes or assisted living facilities), and community health centers, and then along two strata based on respondent type: senior executives (upper management) and administrative line staff. We then chose a random sample of 6713 respondents, divided approximately equally among each of our six stratified groups for survey.

Our survey approach followed the approach recommended by Dillman [35], intended to maximize response rates. We first sent out post-cards to our target respondents informing them of pending arrival of a survey questionnaire soliciting their opinions on the role and use of IT in healthcare. Among our target sample, 778 of these post-cards were returned as “undeliverable” due to invalid addresses or addressee being no longer affiliated with the target organization, resulting in 5,935 usable addresses. Valid subjects were then mailed the questionnaire booklet, along with a personalized cover letter and a postage-paid envelope for mailing back responses. Five weeks after the first mailing, non-respondents were mailed a second round of questionnaire, followed five weeks later by a reminder card urging them again to respond to the questionnaire if they had not already done so.

A total of 555 responses were collected at the end of three rounds, for an overall response rate of 9.4%. To test for non-response bias, we conducted a multinomial distribution test comparing the facility type and respondent’s administrative position in our sample with those of the population (as known from our mailing list). Chisquare difference tests were non-significant for both facility type (χ2 = 5.61, p = 0.16) and respondent’s position (χ2 = 2.53, p = 0.11), suggesting that our sample was reasonably representative of our target population of interest.

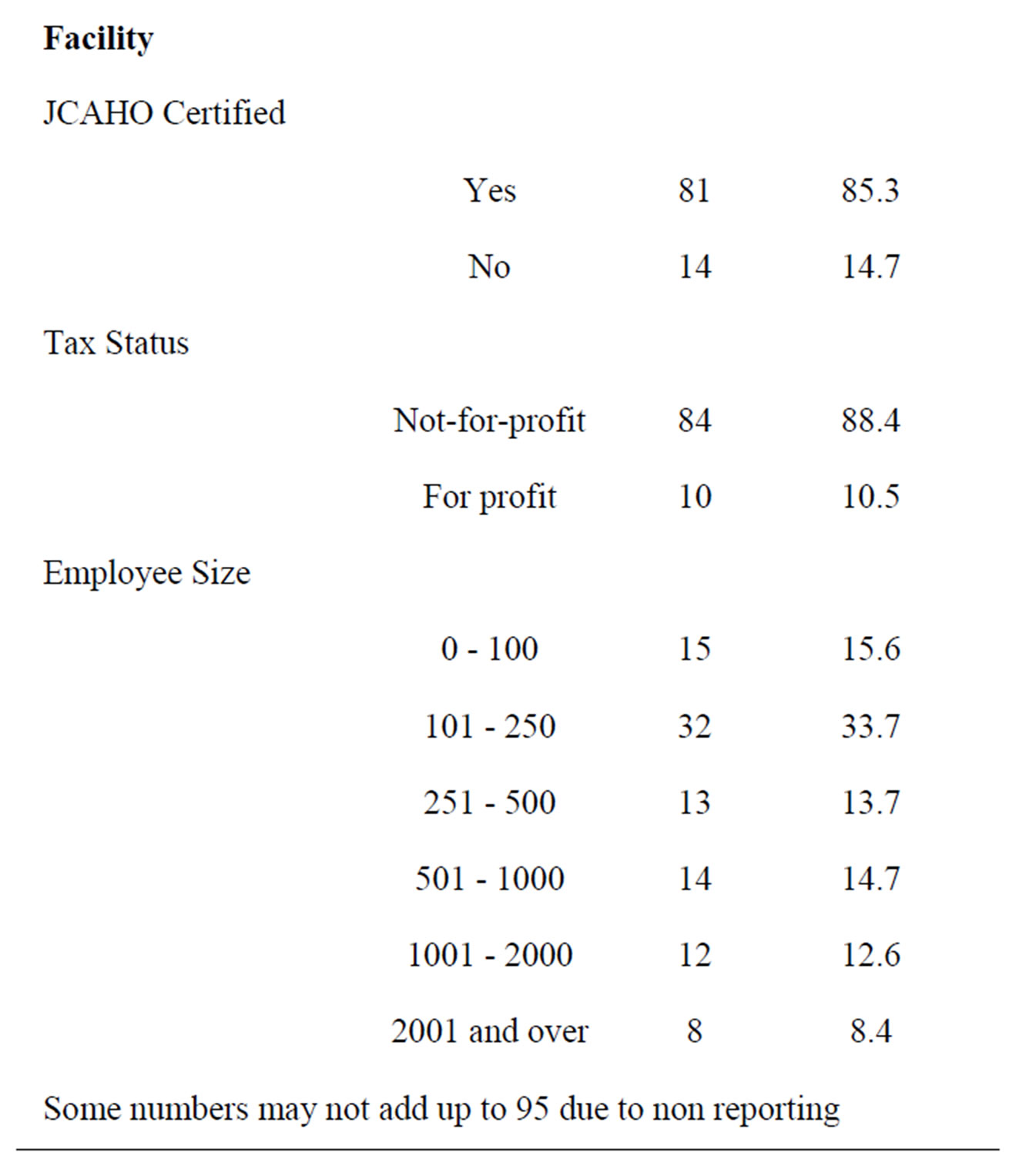

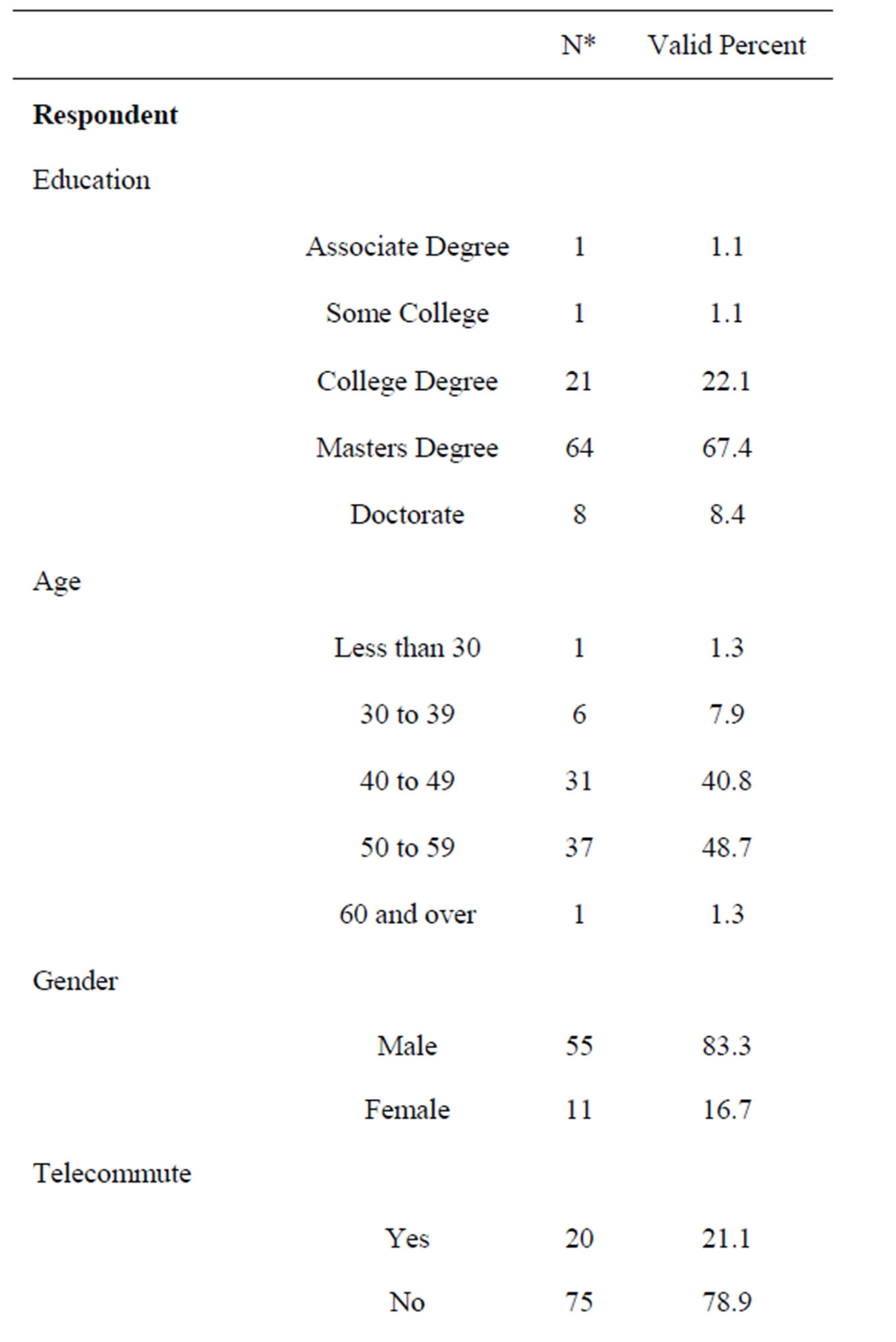

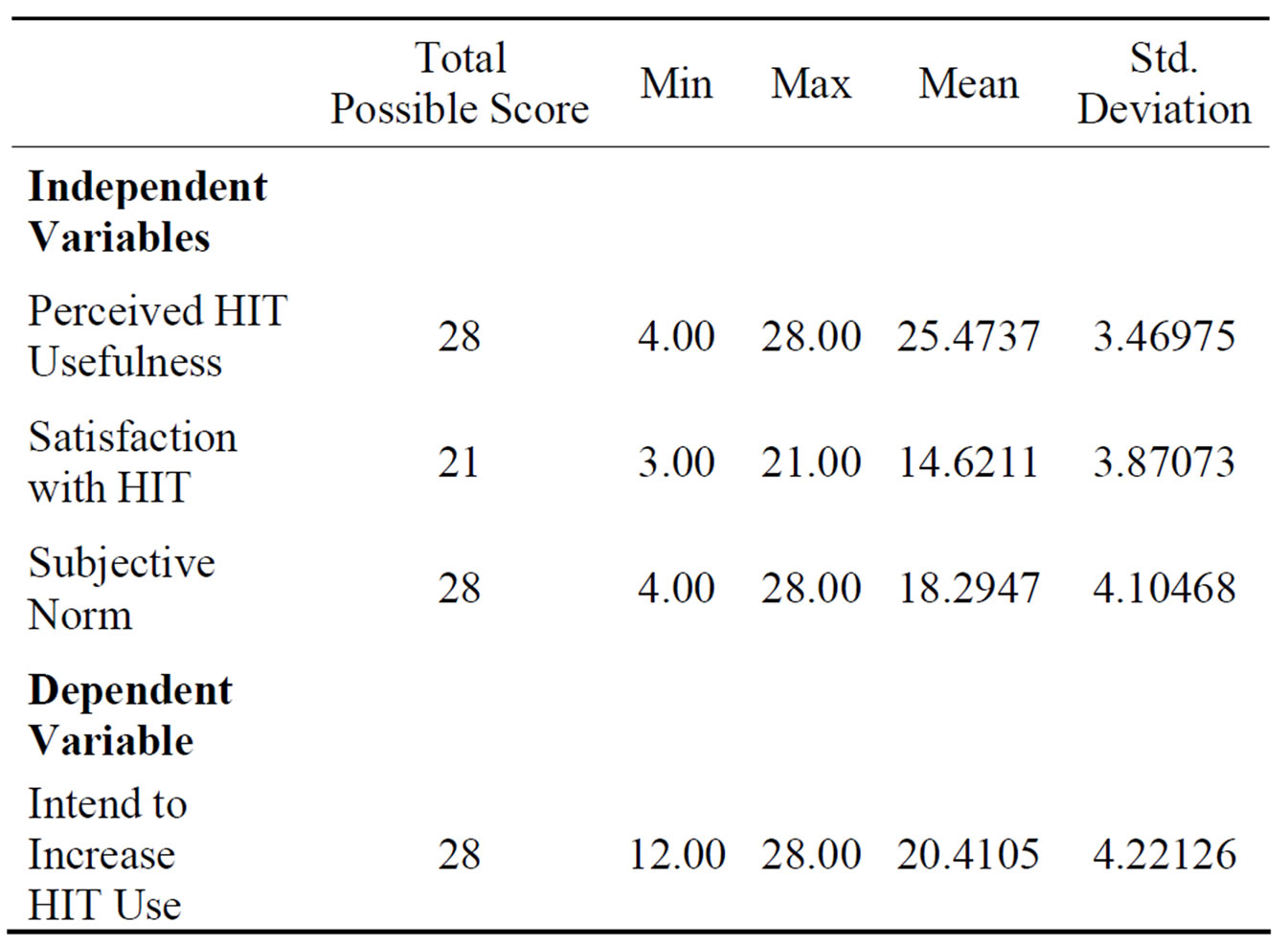

Further examination of the data found a few inconsistent user responses (e.g., subjects indicating that they did not use a computer at work but suggesting elsewhere that they used computers for more than 1 hour per week), which were dropped from our data sample. The resulting set of 456 observations consisted of 332 responses (73%) from senior executives and 124 (27%) from line staff. Of these, 113 responses (25%) came from hospitals, 274 (60%) came from long-term care facilities, and 68 (15%) were from other facilities such as community health centers. Since the perceptions, nature, and scope of IT usage can be quite divergent between senior executives and line staff, we decided to focus our analysis to responses derived only from senior executives (in contrast to line staff). For the specific purpose of this study, we then parsed out the health care executives at hospitals from the data set. This yielded 95 subjects for the category. Out of these respondents 83.3% were male and 16.7% were female subjects. Demographics about the respondents and hospital characteristics are provided in Table 1. The survey instrument consisted of 7 item Likert scale questions probing the HIT users’ perceptions about usefulness of HIT, their level of satisfaction with organizational HIT services, subjective norms, and outcome expectations resulting from increased HIT use. Descriptive statistics for these items are provided in Table 2.

4. Data Analysis and Results

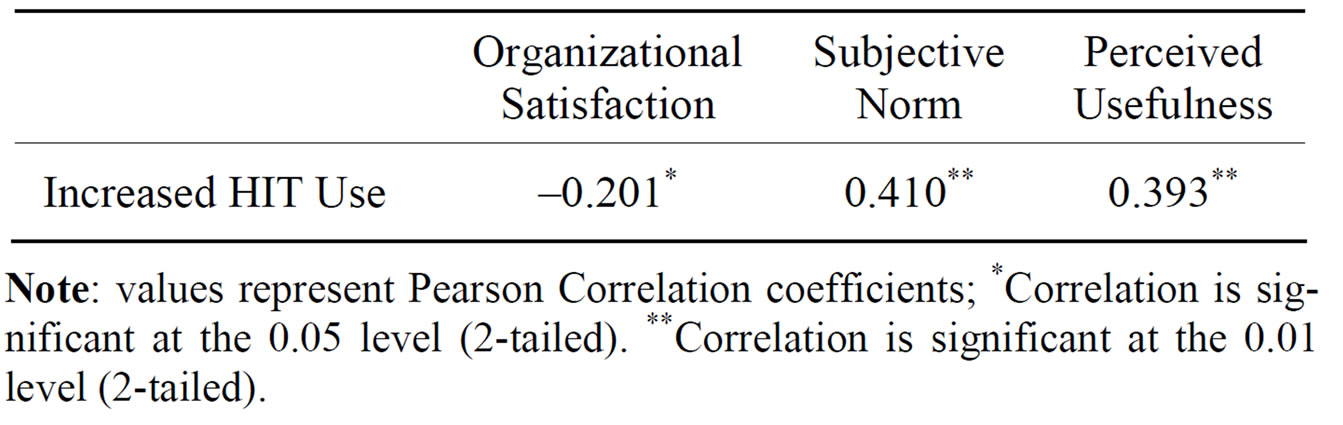

Bivariate Pearson correlations between the dependent and independent variables were computed to investigate for the potential of multicollinearity. No correlation coefficients larger than 0.410 existed among the independent and control variables of interest suggesting that multicollinearity was not deemed to be a problem (Table 3). To control for the potential effects of hospital characteristics, we included employee size, hospital tax status (not-forprofit vs. profit), and JCAHO certification (not certified vs. certified) in the models. These variables were specifically selected because the above literature suggests they each relate to IT adoption in hospitals. Descriptive statistics were first used to examine all variables and to determine their suitability for statistical analysis and regression model was run for the dependent variables in

Table 1. Respondent demographics.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of independent and dependent variables.

Table 3. Bivariate correlations for independent and dependent variables of interest.

order to test the proposed hypotheses.

Hypothesis Testing

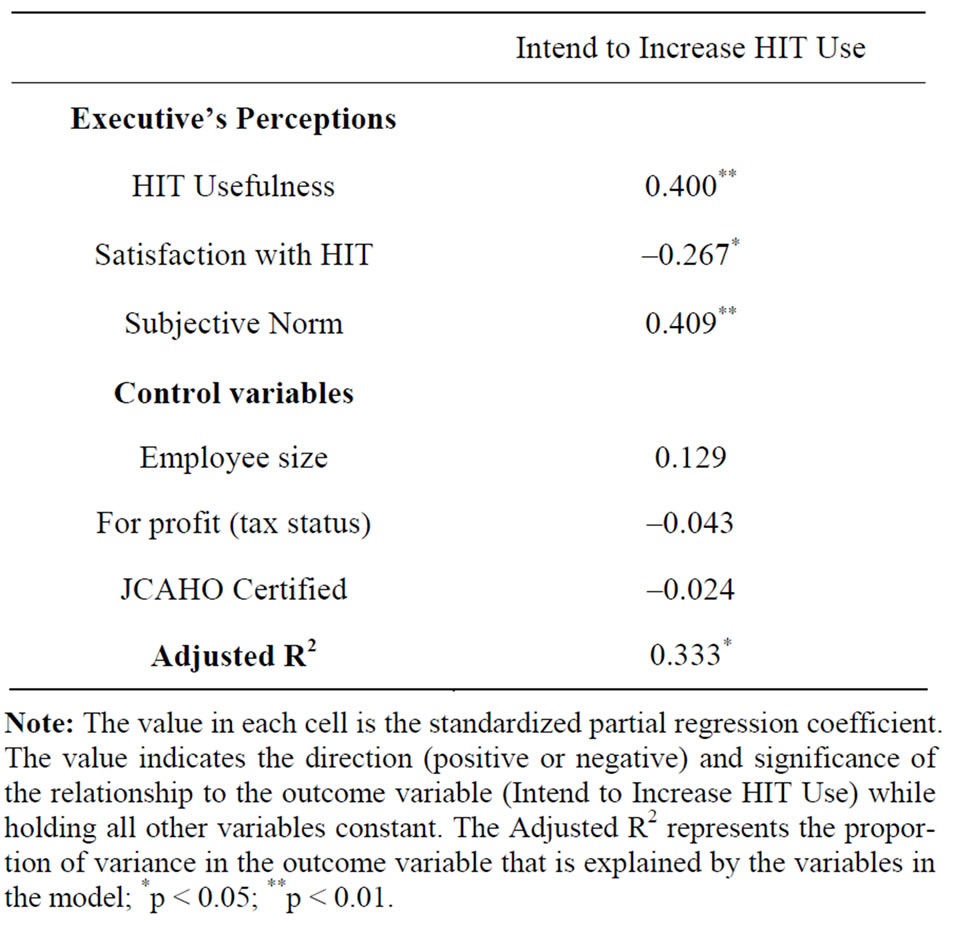

Results from the multiple regression analyses are presented in Table 4. Our model exhibited significant explanatory power with adjusted R2 = 0.33 when controlling for number of employees JCAHO certification, and tax status. Among the independent variables, perceived usefulness (β = 0.400, p < 0.01) and subjective norms (β = 0.409, p < 0.01) had a significant positive impact on an executive’s intent for increased level of HIT adoption while level of satisfaction with organizational HIT had a significant negative association with such behavioral intent (β = –0.267, p < 0.05).

In addition, none of the control variables, number of employees (β = 0.129, p = 0.206), tax status (β = –0.043, p = 0.640), and JCAHO certification (β = –0.024, p = 0.799) were related to an executive’s intent for increased HIT adoption (Table 4).

5. Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to draw attention to underlying individual factors that may be hindering or encouraging the increased use of HIT in hospitals. Based on our results, we believe that it is not an accident that the number of successful implementations of HIT in US health care facilities has been reported to be less than

Table 4. Effects of executive’s perceptions and other covariates on executive’s intend to increase hit use in hospitals.

10% [36], a number that is creating a great concern among policy makers as well as public interest groups. We found that the certain perceptions of health care executives, who are the gatekeepers of funding resources of HIT infrastructure, may play a significant role on the resource allocation for achieving fully integrated HIT.

5.1. Key Findings

The study results were very revealing and offer the readers a better understanding of the unspoken attitudes of executives. Our first hypothesis “H1: There is a positive relationship between executives’ perceived usefulness of HIT and their consideration for further HIT adoption” was supported. Indeed, true to the theory, the findings indicate that executives would consider increasing their HIT use as their perception of the HIT usefulness increased. This finding also supports the position of advocates of HIT dissemination that when executives are made aware of the many useful roles of HIT the more they would be willing to adopt and use it.

One form of adoption has been the positive influence of peers’ opinion on one’s decision with regards to acceptance and/or use of technology. Our findings are no different for the hospital executives. Our second hypothesis “H2: Subjective norms have a positive effect on executives’ consideration for further HIT adoption” was also supported. Emphasizing the role of how the opinion of an executive’s peers can have a positive impact on their intention of further use of HIT at the hospital.

However, we failed to find any support to our third hypothesis “H3: Satisfaction with organizational HIT environment will have a positive effect on executives’ consideration for further HIT adoption”. On the contrary, there was a strong support for a negative relationship (Chart 1). The model suggested that the more satisfied the executives were, the less they were interested in using HIT more than at its current state. Initially, this significant path result would raise a red flag and perhaps questions about the data. But, stepping back and putting this in a proper perspective, we can understand how the relationship is occurring. This is a major revelation of our study. In a hospital setting, the executives are less interested in further use of HIT the more that they are satisfied with the HIT infrastructure and support. One possible explanation is that since these executives are not the true HIT users but rather are the custodians of the resources that are ultimately devoted to patient well-being and quality outcomes. Therefore, their first responsibility is to put the resources where immediate outcomes can be measured. Since HIT investments’ impact on quality of care and patient outcomes measures are not that easy to quantify, their perceptions of available HIT would play an important role on their intentions about increased use of HIT.

Another important finding of the study is the insignificant role of the environmental (JCAHO certification) and the organizational factors (size and tax status) had on hospital executives’ attitudes towards the HIT and their behavioral intentions toward it. Once again this may be a reflection of executive’s decisions being driven more so by the patient welfare in spite of constrains presented by those factors. Thus, such executive mindset perhaps is a contributing factor to the reason why hospitals invest in IT in a lower rate than other industries.

5.2. Implications to Practice

Hospital and health administrators are often making capital decisions regarding resource allocation and planning for future technology investments. Our empirical findings illustrate that hospital executives’ perspective on the role of HIT is not yet well aligned with the proponents of HIT, who tout increased investment in HIT would help reduce medical errors and improve quality. Study results highlight the disassociation within the executives’ minds with regards to HIT’s role and how it pertains to hospital operations. Thus, first and foremost the proponents have to increase their efforts in better demonstration of the business value of HIT investments. Though traditional valuation methods based on financial performance outcomes (e.g., revenue per patient per day) have been used for assessing HIT value, these methods do not work very well because many hospitals are nonprofit institutions and often provide a large amount of charitable healthcare for uninsured, underinsured, or indigent populations, which are often ignored in financial metrics. Secondly, proponents have to focus on demonstrating the goal of HIT in healthcare organizations is to improve healthcare operations and delivery, rather than to maximize profits or revenues. As such, focusing on operational performance outcomes would help securing the hospital executive’s better understanding of HIT’s value and overcome the barrier for streamlining further HIT investments.

6. Conclusions

A low response rate to the mail survey can be seen as a limitation of this study. However, careful bias tests demonstrated that the data was representative of the population studied. Considering the challenges faced in collecting data from health care executives on a national basis through mailed surveys, a methodical approach to overcome potential issues related to the low response rate [37] was adopted for this study.

One of the unique features of this study is the evaluation of the executive’s perceived values in concurrence with factors related to their hospital’s characteristics. Despite the literature’s support for the relevance of organizational characteristics our study demonstrates their irrelevance on executive’s attitude towards IT investments. Most compelling finding is the fact that hospital executives lack motivation to increase their rate of use of HIT regardless of organizational characteristics. Furthermore, those executives who have high perceptions for the usefulness of HIT in job related tasks are less inclined to further increase their HIT use to achieve those perceived high values. The executive’s state of content resulting from the concurrence of the perceived usefulness of HIT and satisfaction with the expected outcomes may be the suppressant condition that renders the previously established organizational characteristics insignificant. Further research, using more finely grained measures of HIT adoption and additional moderators, is first needed to more accurately estimate the executive’s future IT investment intentions. In addition, many external factors such as geographic location (rural vs. urban, competition, size of population served), payer mix (proportion of patients with Medicare, Medicaid, or health maintenance organization coverage with fixed reimbursement schedules), and so forth, which are usually beyond hospital executive’s control should be further investigated.

REFERENCES

- A. Bharadwaj, “A Resource-based Perspective on Information Technology Capability and Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2000, pp. 169-196. doi:10.2307/3250983

- Agency for Health care Research and Quality, “Demonstrating the Value of Health Information Technology,” 2003 http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HS-04-012.html

- US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, “Bringing Health Care Online: The Role of information Technologies,” US Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1995.

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, “Effective Dissemination of Health and Clinical Information and Research Findings,” US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington DC, 1998.

- J. Glaser, “The Myths of Benchmarking Healthcare IT Spending,” Healthcare Financial Management, Vol. 60, No. 10, 2006, pp. 56-59.

- Health IT, “Health Information Technology for the Future of Health and Care,” http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt

- K. Altinkemer, Y. Ozcelik, and Z. Ozdemir, “Productivity and Performance Effects of IT-Enabled Reengineering: A Firm-Level Analysis,” Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Information Systems, Geneva, 10-14 September 2007, pp. 985-993.

- A. M. Jonson and A. L. Lederer, “The Impact of Communications between CEOs and CIOs on their Shared Views of the Current and Future Role of IT,” Information Systems Management, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2007, pp. 85-90. doi:10.1080/10580530601038246

- N. Hikmet and M. Burns, “Health Care Executives: The Association between External Factors, Use, and Their Perceptions of Health Information Technology,” Proceedings of the Tenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New York, 5-8 August 2004, pp. 220-227.

- N. Hikmet, J. Perols, J. Griffith, D. Nagy, A. Bhattacherjee and R. Fuller, “A Survey of Health Care Information Technology Research in the IS Literature,” White paper, 2005.

- S. Bretschneider and D. Wittmer, “Organizational Adoption of Microcomputer Technology: The Role of Sector,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1993, pp. 88-108. doi:10.1287/isre.4.1.88

- C. R. Franz and C. Robey, “Organizational Context, User Involvement, and the Usefulness of Information Systems,” Decision Sciences, Vol. 17, No. 3, 1986, pp. 329- 356. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5915.1986.tb00230.x

- M. Igbaria, N. Zinatelli, P. Cragg and A. L. M.Cavaye, “Personal Computing Acceptance Factors in Small Firms: A Structural Equation Model,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3, 1997, pp. 279-305. doi:10.2307/249498

- J. Y. L. Thong and C. S. Yap, “CEO Characteristics, Organizational Characteristics and Information Technology Adoption in Small Businesses,” Omega, Vol. 23, No. 4, 1995, pp. 429-442. doi:10.1016/0305-0483(95)00017-I

- D. W. Bates, “Using Information Technology to reduce rates of Medication Errors in Hospitals,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 320, No. 7237, 2000, pp. 788-791. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7237.788

- R. Kaushal, K. Shojania and D. W. Bates, “Effects of Computerized Physician Order Entry and Clinical Decision Support Systems on Medication Safety,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 163, No. 12, 2003, pp. 1409-1416. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.12.1409

- J. A. Menke, C. W. Broner, D. Y. Campbell, M. Y. McKissick and J. A. Edwards-Beckett, “Computerized Clinical Documentation System in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit,” BMC Medical Information Decision Making, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2001. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-1-3

- M. K. Pabst, J. C. Scherubel and A. F. Minnick, “The impact of Computerized Documentation on nurses’ use of time,” Computers in Nursing, Vol. 14, No. 1, 1996, pp. 25-30.

- N. Menachemi, J. Burkhardt, R. Shewchuk, D. Burke and R. G. Brooks, “Hospital Information Technology and Positive Financial Performance: A different approach to ROI,” Journal of Healthcare Management, Vol. 51, No. 1, 2006, pp. 40-58.

- R. L. Ohsfeldt, M. M. Ward, J. E. Schneider, M. Jaana, T. R. Miller, Y. Lei, et al., “Implementation of Hospital Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems in a Rural State: Feasibility and Financial Impact,” Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2005, pp. 20-27. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1553

- D. Burke, N. Menachemi and R. G. Brooks, “Diffusion of Information Technology Supporting the Institute of Medicine’s Quality Chasm Care Aims,” Journal of Healthcare Quality, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2005, pp. 24-32. doi:10.1111/j.1945-1474.2005.tb00542.x

- N. Hikmet and A. Bhattacherjee, “The Impact of Professional Certifications on Healthcare Information Technology Use,” International Journal of Healthcare Systems and Informatics, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2006, pp. 58-68.

- E. M. Rogers, “Diffusion of Innovation,” 4th Edition, The Free Press, New York, 1995.

- M. J. Ginzberg, “Early Diagnosis of MIS Implementation Failure: Promising Results and Unanswered Questions,” Management Science, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1981, pp. 459-478. doi:10.1287/mnsc.27.4.459

- B. Ives, M. H. Olson and J. J. Baroudi, “The Measurement of User Information Satisfaction,” Communications of the ACM, Vol. 26, No. 10, 1983, pp. 785-793. doi:10.1145/358413.358430

- A. Bhattacherjee and G. Premkumar, “Understanding Changes in Belief and Attitude toward Information Technology Usage: A Theoretical Model and Longitudinal Test,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2004, pp. 229-254.

- F. D. Davis, R. P. Bagozzi and P. R. Warshaw, “User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models,” Management Science, Vol. 35, No. 8, 1989, pp. 982-1003. doi:10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

- A. Bandura, “Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control,” W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, 1997.

- D. A. Harrison, P. P. Mykytyn Jr. and C. K. Reimenschneider, “Executive Decisions about Adoption of Information Technology in Small Business: Theory and Empirical Test,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1997, pp. 171-195. doi:10.1287/isre.8.2.171

- S. Taylor and P. Todd, “Assessing IT Usage: The Role of Prior Knowledge,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 4, 1995, pp. 561-570. doi:10.2307/249633

- B. H. Wixom and B. H. Todd, “Theoretical integration of User Satisfaction and Technology Acceptance,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2005, pp. 85-102. doi:10.1287/isre.1050.0042

- A. Bhattacherjee, “Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2001, pp. 351-370. doi:10.2307/3250921

- J. E. Bailey and S. W. Pearson, “A Tool for Computer User Satisfaction,” Management Science, Vol. 29, No. 5, 1983, pp. 530-545. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.5.530

- N. P. Melone, “A Theoretical Assessment of the UserSatisfaction Construct in Information Systems Research,” Management Science, Vol. 36, No. 1, 1990, pp. 76-91. doi:10.1287/mnsc.36.1.76

- D. A. Dillman, “Mail and Telephone Surveys,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1978.

- D. Burke, B. Wang, T. Wan and M. Diana, “Exploring Hospitals’ Adoption of Information Technology,” Journal of Medical Systems, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2002, pp. 349- 355. doi:10.1023/A:1015872805768

- N. Hikmet and S. K. Chen, “An investigation into Low Mail Survey Response Rates of Information Technology Users in Health Care Organizations,” International Journal of Medical Informatics, Vol. 72, No. 1, 2003, pp. 29- 34. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2003.09.002