iBusiness

Vol.5 No.2(2013), Article ID:33743,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2013.52007

Personality Mapping: Tool to Analyze Achievement Orientation

![]()

Amrut Mody School of Management, Ahmedabad University, Gujarat, India.

Email: ektas55@ rediffmail.com

Copyright © 2013 Ekta Sharma. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received April 2nd, 2013; revised May 2nd, 2013; accepted June 2nd, 2013

Keywords: Achievement Motivation; Personality; Big 5 Traits; Conscientiousness; Extraversion; Agreeableness

ABSTRACT

Personality can affect an individual’s motivation towards achievements. The analysis of personality can help recruiter to know the motives of the candidate and hence, would help in making right choice. Therefore, the current study focuses on the analysis of personality traits which affect the achievement motivation. The sample includes 168 working professsionals from diverse backgrounds. The study shows that the achievement motivation is a function of the Big five traits. As per the five factors model of personality people high on conscientiousness are considered as an organized, focused and timely achiever of their goals. They tend to be workaholic and are self-disciplined, confident, dutiful and reliable. So, the result of the research that conscientiousness is significantly related to achievement motivation seems self explanatory.

1. Introduction

Everyday exposure to a culture’s customs and practices informally socializes individuals to a culture’s values and beliefs. Different cultures cultivate different values and beliefs concerning qualities that are important, worth pursuing, and socially desirable. Individuals who acquire these cultural values and beliefs also acquire behaviors which in turn might affect their motivation and achievement [1,2].

Achievement motivation is part of the earliest psychological theory of motivation which referred to the achievement motive as one of the three basic human motives. It suggested that achievement related situations are characterised by approach and avoidance components that stimulate hope for success or fear of failure [3].

Personality can affect an individual’s motivation towards achievement. Achievement motivation is a socialpsychological theory of motivation [3]. This type of motivation falls under the category of social needs and is defined as the need to excel relative to a standard of excellence (Reeve, 2009). Situations that involve achievement can be divided into two main characteristics either approach or avoidance that in turn create feelings of hope for success or fear of failure [3]. Cassidy and Lynn (1989), formulated a measure of achievement motivation, which is assessed through seven different dimensions; pursuit of excellence, work ethic, status aspiration, competitiveness, acquisitiveness, mastery and dominance [4]. Hart, et al. 2007, reduced the number of dimensions into a two-dimensional model Extrinsic and Intrinsic [5]. Extrinsic includes status aspiration, competitiveness, acquisitiveness, dominance and intrinsic includes pursuit of excellence, work ethic and mastery. Achievement motivation is the drive to achieve success and is related to competetiveness, persistence, and striving for perfection [6]. It is the desire to accomplish a difficult task, overcome obstacles, and attain a high standard [7]. Achievement motivation is also the personal striving of individuals to attain goals within their social environment [4]. One of the first researchers to have an interest in achievement motivation was Henry Murray in 1938. The need for achievement is: “To accomplish something difficult. To master, manipulate or organize [sic] physical objects, human beings, or ideas” [8].

McClelland further developed the concept of achievement motivation and described it as a learned, unconscious drive, where behaviour involves competition with a standard of excellence. If successful a positive feeling is produced and if unsuccessful a negative feeling is produced [9]. Although achievement motivation is related to winning and high performance it is satisfied by succeeding and excelling rather than with extrinsic rewards [9].

More recent research suggested that the key to success of an individual is their achievement motivation level. Researches defined the main characteristics of achievement motivation as working ambitiously, being selfconfident, and motivated. Other characteristics included; competitiveness, independence, eagerness to learn, preferring of regular and continuous work, being focused, wanting to attain high performance goals, wanting to be responsible for any decisions made ,enjoying challenges, having a higher tendency to take risks ,valuing competence, being creative, having strong instincts of achieving individual and organisational success, and preferring achievement related feedback [9]. Individuals high in achievement motivation are usually not satiated with their current responsibilities and so consider new responsibilities. They are open to constructive criticism and likely to respond to failure positively and optimistically, and do not have fear of failure, which proves their persistence and perseverance. It has been found that individuals low in achievement motivation were considered “quitters”, expected failure, avoided meaningful challenges and were less likely to respond to failure with increased effort. [9]

2. Achievement Motivation and Personality

Correlations between the Five Factor Model and achievement motivation have been found in previous studies [10]. Achievement motivation was found to be positively correlated with conscientiousness and extraversion, and negatively with neuroticism, impulsiveness, and fear of failure [11]. The reason for this might be because there are similarities between descriptions of an individual who is high on achievement motivation, conscientious, and extraverted. Achievement motivation might have been negatively correlated with neuroticism, impulsiveness, and fear of failure as a neurotic individual was found to worry a lot, experience negative emotions, and not want to attempt a hard task for the fear of failure, which does not fit with the description of an individual high in achievement motivation [11]. According to Dweck and Leggett (1988) openness and achievement motivation was positively correlated as being creative allowed an individual to work in an environment that offered stimulation, a chance to be ambitious, and to take risks [12].

Emotional stability was found to relate to self-efficacy motivation, believing that one is capable of successfully performing a given activity [13]. The reason for this is because emotionally stable individuals were more effecttively able to control their negative emotions when performing required tasks and so had higher self-efficacy motivation [13]. Eggens, Hendriks, Bosker, and Van der Werf (2010) found that emotionally stable individuals were less likely to be concerned with achieving compared to individuals low in emotionally stability [14]. Eggens, et al. (2010) suggested the reason for this is that individuals who are low in emotional stability are easily overwhelmed and therefore work harder to try and reduce these feelings [14].

Personality can affect an individual’s motivation towards achievement. The analysis of personality can help recruiter to know the motives of the candidate and hence, would help them in making the right choice. Therefore, the current study focuses on the analysis of personality traits which affect the achievement motivation. The sample includes 168 working professionals from diverse backgrounds.

3. Literature Review

There is dearth of research in the area of personality traits and achievement motivation. Although researchers have worked for these themes but mostly in relation with academic achievement and not in the corporate environment.

Cantner, Silbereisen and Wilfling (2011), discussed about the relation between the comprehensive personality of highly innovative entrepreneurs and their disposition to fail. The research concludes that agreeable entrepreneurs have a lower probability to fail at all times from the start up of their firms. In contrast, conscientiousness increases the failure hazard rate at the time launching a firm, even if this effect diminishes over time. Neuroticism, openness, and extraversion are seemingly not related to the hazard of entrepreneurial failure in highly innovative industries [15].

Richardson and Abraham (2009) conducted a survey to identify predictors of university students’ grade point average (GPA). Big five personality traits and achievement motivation were measured. The study shows that conscientiousness and achievement motivation have impact on GPA. Latent variable structural equation modeling showed that the effect of conscientiousness on GPA is fully mediated by achievement motivation for both female and male students [16].

Premuzic and Furnham (2009) examined the relationship between broad personality traits and learning approaches. Openness to Experience and Deep learning was supported by both correlational and structural equation modeling tests in their study. Openness was also found to be negatively linked to Surface learning, but other Big Five traits were not saliently associated with learning approaches. The study concludes that there is hardly any overlap between learning approaches and personality traits [17].

Komarraju, Karau and Schmeck (2009) studied the relationship between personality, Academic Motivation and grade point average (GPA). The regression analysis indicated that conscientiousness and openness explained 17% of the variance in intrinsic motivation; conscientiousness and extraversionexplained 13% of the variance in extrinsic motivation; and conscientiousness and agreeableness explained 11% of the variance in a motivation. Further, four personality traits (conscientiousness, openness, neuroticism, and agreeableness) explained 14% of the variance in GPA; and intrinsic motivation to accomplish things explained 5% of the variance in GPA. Finally, conscientiousness emerged as a partial mediator of the relationship between intrinsic motivation to accomplish and GPA [12].

Sabry M. and Patrick (2011) examined the relationships among achievement motivation orientations and academic achievement and interest and whether achievement goals mediate these relationships. Results of the study showed individual-oriented achievement motivation (IOAM) and social-oriented achievement motivation (SOAM) are correlated positively [18].

Rivait (1969) examined the influence of certain training practices in the development of the need for achievement and also the relationship between achievement motivation and Intra-family interaction and selected personality traits. Thus, the relationship between certain dependent variables, such as-home background, personality characteristics and relationships with other family members-and, the independent variable-need achievement-was studied [19].

Seibert and Kraimer (2001) have examined the relationship between the “Big Five” personality dimensions and career success. The study concluded that extravertsion was positively related to career satisfaction, salary, and promotions. Openness was negatively related to salary. Neuroticism and agreeableness were negatively related to career satisfaction. Conscientiousness was not significantly related to any of the career outcomes. Strong predictors of achievement motivation in terms of personality are Conscientiousness (positively) and Emotional Stability (positively) [20].

A study conducted by Hart, et al. 2007 researched the relationship between the five factor model personality traits and achievement motivation; they wanted to find out if you were scored as high in certain traits are you more likely to be intrinsically or extrinsically motivated towards achievement. In this study they found individuals influenced by high intrinsic achievement motivation (IAM) were high in conscientiousness, openness to experience and extraversion and agreeableness was negatively associated with extrinsic achievement motivation (EAM). There was also a positive relationship found between EAM and extraversion and EAM and conscientiousness. Implications of these findings are related to work and school settings, by understanding an individual’s personality, you may be able to understand how they are motivated which in turn could allow them greater achievement in those settings [21].

4. Methodology

The sample has been selected and the personality and achievement motivation are taken as the research variable.

5. Objective

The objective of the study is to analyze the relation between personality traits and the achievement motivation.

6. Participants

The sample consists of 168 working professionals. Out of which 99 are males and 69 are females.

The industry-wise distribution is as follows: 26 from telecom, 31 from Information technology, 13 from education, 23 from textile, 18 from banking, 15 from health services, 15 from BPO and rest from other industry.

7. Instruments

7.1. Big Five Personality Traits

The revised NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992) is a 240 item inventory measuring the five major personality dimensions of neuroticism (anxiety, angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsivity, vulnerability to stress), extraversion (warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement seeking, positive emotions), openness (fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, activity, ideas, values), agreeableness (trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty, tender-mind-edness) and conscientiousness (competence, order, dutifulness, achievement, self-discipline, deliberation) by means of statements [22]. Studies have shown that internal consistency estimates for the five domains of the NEO PI-R have ranged from 0.86 to 0.95, and it has been shown to have good content, criterion-related, and construct validity [23]. The present Norwegian version of this inventory has replicated the factor structure and it has shown good internal consistency (alpha) as compared to international research [24]. The participants indicate their relative agreement with statements by setting a mark along a 5- point scale with anchors of 1: Strongly Disagree and 5: Strongly Agree. A principal component analysis (Varimax rotation) of data in the present study produced the expected five factor solution (Eigenvalue > 1) accounting for 58.3% of the variance.

7.2. Achievement Motivation

The achievement variable motivation has been calculated with the help of questionnaire which included General Beliefs Inventory (GBI) and Value Preference Survey

(VPS) [25]. GBI measures the perceived instrumentality, while VPS, measures the value of the various outcomes i.e. various aspects of achievement. Both the inventories have 12 items. The higher score connotes the high perseverance level of the subject and therefore higher achievement orientation.

7.3. Hypothesis Formulation and Testing

The literature review reflects that strong predictors of achievement motivation in terms of personality are Conscientiousness (positively) and Emotional Stability (positively) [26]. In our study, instead of Emotional stability, we have taken Neuroticism as one of the traits, which is opposite of Emotional Stability. So, as the emotional stability is positively related, we can derive that neuroticcism is negatively related. From this we have formulated Hypothesises 1 and 2.

Hypothesis 1: Achievement motivation is positively correlated to Conscientiousness.

Table 1 shows that the correlation between achievement motivation and conscientiousness is 0.757, which is positively significantly related. Hence, the hypothesis is accepted.

Hypothesis 2: Achievement motivation is negatively correlated to Neuroticism.

The achievement motivation and Neuroticism arenegatively correlated (−0.086) but the correlation is not very significant. (Table 1)

Extraversion has also been found to be positively related with achievement motivation [27-30].

Hypothesis 3: Achievement motivation is positively correlated to Extraversion.

The achievement motivation and Extraversion are positively correlated (0.111) but the correlation is not very significant (Table 1).

8. Discussion

The purpose of the study was to analyze the relationship between personality traits and achievement motivation. The study shows that the achievement motivation is a function of the Big five traits. As per the five factors model of personality people high on conscientiousness are considered as an organized, focused and timely achiever of their goals. They tend to be workaholic and are self-disciplined, confident, dutiful and reliable. So, the result of the research that conscientiousness is signifycantly related to achievement motivation seems self explanatory.

The research shows that even agreeableness is signifycantly correlated to the achievement motivation (Table 1). This can be due to the reason that, if people who want to achieve more, strive towards the goal by discussing the paths with others and want to be sure that they are taking the right path.

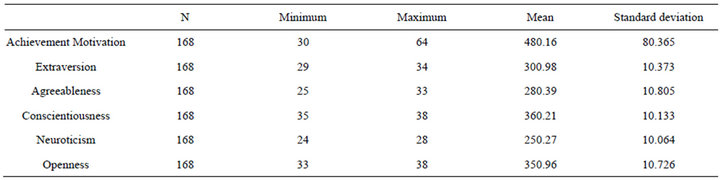

Table 2 shows that the sample is high on conscientiousness (Mean = 36.21) and openness to experience (Mean = 35.96). They are moderate on Extraversion (Mean = 30.98) and low on agreeableness (Mean = 28.39) and Neuroticism (Mean = 25.27).

Table 1. Correlation between different personality variables and achievement motivation (N = 168).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of research variables.

The insight into personality variables and achievement motivation aspects shows that although personality traits are important indicator of achievement motivation but it seems there are some more moderating variable contributing towards the achievement motivation.

9. Conclusion

The conscientiousness trait should be analyzed to infer the achievement motivation of the subject. Such analysis can be a base of the recruitment and selection process of the prospective employee. The recruiter can identify the need of achievement motivation for the job under consideration and depending on that can analyze the personality traits, to get the right people at right place with right motive.

REFERENCES

- J. G. Elliott and J. Bempechat, “The Culture and Contexts of Achievement Motivation,” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, Vol. 2002, No. 96, 2002, pp. 7-26. doi:10.1002/cd.41

- A. B. Yu, and K. S. Yang, “The Nature of Achievement Motivation in Collectivist Societies,” In: U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S. C. Choi and G. Yoon Eds., Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, Methods, and Applications, Sage Publications, London, 1994, pp. 239- 250.

- R. Steinmayr and B. Spinath, “Sex Differences in School Achievement: What Are the Roles of Personality and Achievement Motivation?” European Journal of Personality, 22, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2008, pp. 185-209. doi:10.1002/per.676

- T. Cassidy and R. Lynn, “A Multifactorial Approach to Achievement Motivation: The Development of a Comprehensive Measure,” Journal of Occupational Psychology, Vol. 62, No. 4, 1989, pp. 301-312.

- J. W. Hart, M. F. Stasson, J. M. Mahoney and P. Story, “The Big Five and Achievement Motivation: Exploring the Relationship between Personality and a Two-Factor Model of Motivation,” Individual Differences Research, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2007, pp. 267-274.

- A. Kaplan and M. L. Maehr, “Achievement Goals and Student Well-Being,” Contemporary Educational Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 4, 1999, pp. 330-358. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.0993

- S. O. Salami, “Affective Characteristics as of Determinants of Academic Performance of School-Going Adolescents: Implication for Counselling and Practice,” Sokoto Educational Review, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2004, pp. 145- 160.

- H. A. Murray, “Explorations in Personality,” Oxford University Press, New York, 1938.

- R. Glaser, “Personality and Achievement Motivation as Determinants of Career Choice,” Honours Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, 2012.

- H. Schuler and M. Prochaska, “Entwicklung und Konstruktvalidierung eines Berufsbezogenen Leistungsmotivationstests,” Diagnostica, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2000, pp. 61-72.

- M. Komarraju, S. J. Karau and R. R. Schmeck, “Role of the Big Five Personality Traits in Predicting College Students’ Academic Motivation and Achievement,” Learning and Individual Differences, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2009, pp. 47- 52. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.07.001

- C. S. Dweck, and E. L. Leggett, “A Social-Cognitive Approach to Motivation and Personality,” Psychological Review, Vol. 95, 1988, pp. 256-273. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

- L. Parks and R. P. Guay, “Personality, Values, and Motivation,” Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 47, No. 7, 2009, pp. 675-684. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.002

- L. Eggens, A. A. J.Hendriks, R. J. Bosker and M. P. C. Van der Werf, Personality, procrastination and achievement motivation, Dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Rotterdam, 2010.

- U. Cantner, R. K. Silbereisen and S. Wilfling (2011). “Which Big-Five Personality Traits Drive Entrepreneurial Failure in Highly Innovative Industries?” DIME-DRUID Academy Winter Conference 2011, Aalborg, 20-22 January 2011.

- M. Richardson and C. Abraham, “Conscientiousness and Achievement Motivation Predict Performance,” European Journal of Personality, Vol. 23, No. 7, 2009, pp. 589-605. doi:10.1002/per.732

- T. Chamorro-Premuzic and A. Furnham, “Mainly Openness: The Relationship between the Big Five Personality traits and Learning Approaches,” Learning and Individual Differences, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2009, pp. 524-529

- S. M. Abd-El-Fattah and R. R. Patrick, “The Relationship among Achievement Motivation Orientations, Achievement Goals, and Academic Achievement and Interest: A Multiple Mediation Analysis,” Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology. Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011, pp. 91-110

- E. T. Rivait, “An Investigation of Background Factors and Selected Personality Correlates of Achievement Motivation,” Master Thesis, Wilfrid Laurier University, Brantford, 1969.

- S. E. Seibert and M. L. Kraimer, “The Five-Factor Model of Personality and Career Success,” Journal of Vocational Behaviour, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2001, pp. 1-21. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2000.1757

- J. W. Hart, M. F Stasson, J. M. Mahoney and P. Story, “The Big Five and Achievement Motivation: Exploring the Relationship between Personality and a Two-Factor Model of Motivation,” Individual Differences Research, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2007, pp. 267-274.

- T. P. Costa Jr. and R. R. McCrae, “Normal Personality Assessment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory,” Psychological Assessment, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1992, pp. 5-13. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5

- R. R. McCrae and P. T. Costa Jr., “Conceptions and Correlates of Openness to Experience,” In: R. Hogan, J. A. Johnson and S. R. Briggs, Eds., Handbook of personality psychology, Academic Press, New York, 1996, pp. 825- 847.

- Ø. Martinsen, H. Nordvik and L. E. Østbø, “Norske Versjoner av NEO-PI-R og NEO FFI [Norwegian Versions of NEO-PI-R and NEO FFI]. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening,” Journal of the Norwegian Psychological Association, Vol. 42, 2003, pp. 421-422.

- U. Pareek and Purohit, “Training Instruments in HRD and OD,” 3rd Edition, Tata Mc Graw Hill Publishing House, Noida, 2010.

- E. S. Seibert and M. L. Kraimer, “The Five-Factor Model of Personality and Career Success,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2001, pp.1-21. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2000.1757.

- J. W. Hart, M. F. Stasson, J. M. Mahoney and P. Story, “The Big Five and Achievement Motivation: Exploring the Relationship between Personality and a Two-Factor Model of Motivation,” Individual Differences Research, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2007, pp. 267-274.

- T. A. Judge and R. Ilies, “Relationship of Personality to Performance Motivation: A Meta-Analytic Review,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, No. 4, 2002, pp. 797-807. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.797

- M. Komarraju and S. J. Karau, “The Relationship between the Big Five Personality Traits and Academic Motivation,” Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2005, pp. 557-567. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.013

- M. Komarraju, S. J. Karau and R. R. Schmeck, “Role of the Big Five Personality Traits in Predicting College Students’ Academic Motivation and Achievement,” Learning and Individual Differences, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2009, pp. 47- 52. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.07.001