iBusiness

Vol.1 No.2(2009), Article ID:1049,10 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2009.12010

Economic Freedom and Foreign Direct Investment: How Different are the MENA Countries from the EU1

![]()

Departamento de Economia & CEFAGE-UE, Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal.

Email: jcaetano@uevora.pt, caleiro@uevora.pt

Received September 5, 2009; revised October 15, 2009; accepted November 26, 2009.

Keywords: Economic Freedom, European Union (EU) Countries, Foreign Direct Investment, Fuzzy Clustering, Institutions, Middle East North Africa (MENA) Countries

ABSTRACT

The risk perceived by investors is crucial in the decision to invest, in particular when it concerns a foreign country. The risk associated to any (foreign) investment is a multi-faceted element given that it reflects many aspects that are relevant to (foreign) investors, such as the level of transparency, corruption, rule of law, governance, etc. In this paper we consider the level of economic freedom, as provided by the “Heritage Foundation”, for the most recent years, in order to analyse how is this measure of risk related to the inward foreign direct investment performance index, as provided by the UNCTAD. Given the subjectivity of risk an appropriate methodology consists on using fuzzy logic clustering, which is applied in the paper in order to verify how different the MENA region is from the set of EU-member states. The results show that economic freedom and inward FDI are positively associated, in particular in the cluster of countries that present a higher economic freedom. Of particular interest is the result that some MENA countries belong to the same cluster of most of the EU-countries.

1. Introduction

Since the 1990s the literature has been paying more attention to the importance of the quality of institutions and of economic freedom for the countries economic development. Economic freedom means the degree to which a market economy is in place, where the central components are voluntary exchange, free competition, and protection of persons and property. O’Doriscoll et al. [1] define economic freedom as “the absence of government coercion or constraint on the production, distribution or consumption of goods and services beyond the extent necessary for citizens to protect and maintain liberty itself”. In these terms, the economic freedom could be a key factor accounting for economic growth [2].

The incentives that economic actors face are determined in large part by the institutions in place, which can be more or less efficient. Furthermore, sustained high growth rates imply eventually great wealth, and so in the long term the economic freedom that increases growth can also be expected to increase wealth. Despite this fact, there are theoretical reasons to expect a positive relation between economic freedom and economic growth but does empirical evidence confirm this link?

A number of studies have corroborated those expectations, with varying strengths and in different forms. For instance, Adkins et al. [4] find that the level of economic freedom at the beginning of the growth period does not contribute significantly to explaining growth, but that positive changes in economic freedom do so. Yet, other studies conclude that the initial level of economic freedom is also positively related to growth [5]. In any case, the issues included in economic freedom should be taking into account once policies try to promote economic development.

Since the share of the developing countries in the global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows has been Rising2, there is also a growing interest in study the determinants of this kind of flows. In fact, the literature has accepted that FDI can provide additional resources for developing countries, by which they could improve their economic performance and factor productivity, through the diffusion of technological progress and the boost of domestic investment [6].

In this context some studies have analyzed the importance of economic freedom in the FDI performance in developing countries, especially in what concerns some aspects of a country’s trade policy, its banking and finance services and its property right protection [7]. Likewise, Gwartney et al. [8] suggested that the key ingredients to economic freedom include freedom to compete, voluntary exchange, and protection of person and property.

In order to uncover the factors that matters for foreign investment flows, it is necessary to distinguish the following types of investment: market seeking; resource seeking; efficiency seeking. Thus, the new wave of globalization has led to a reconfiguration of the ways in which multinationals pursue these various types of FDI, and changed the motives for investing abroad. Dunning [9] sustain that the FDI in developing countries has been shifting from market and resource seeking investments, to more efficiency seeking investments. Some authors argue that the relative importance of the traditional market related factors (wage costs, infrastructure or macroeconomic policy) no longer hold and suggest that less traditional determinants have become more important, like institutions or economic freedom [10].

The paper considers the Middle East North Africa (MENA) countries, vis-a-vis the European Union (EU) ones, for the following reasons. FDI flows to the MENA region have been relatively low when compared to the EU and to other developing and emerging countries [11]. Some characteristics of the MENA countries could entail an important constraint for the inward FDI performance. This region is highly anchored on oil, which weakens the economic base, has high unemployment rates, displays a weak regional economic integration and the capital and financial markets persist undeveloped.

Yet, some countries in the region are witnessing a new era in privatization, bank regulation and market-oriented financial institutions, making the need to look at the role of other determinants even more pertinent. The analysis of MENA institutional systems that influence economic freedom appears to be attractive since a significant number of this countries is been experiencing institutional reforms. Moreover, the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership Agreement, along with the progressive elimination of trade barriers, has boosted trade relations and some countries have liberalized their investment regulatory framework, creating particular regimes for FDI. Taking into account these facts and the relatively scarce empirical research on FDI in MENA countries, we consider being important to study this subject.

There is a vast literature on the determinants of FDI and the empirical studies differ in terms of the variables, methodologies, the type of FDI and the countries included. In general, variables affecting the FDI flows can be classified into two categories: market-oriented variables and institutional-oriented variables. In this study, our emphasis is the institutional-oriented variables, especially in the economic freedom issues.

In this paper we use the Index of Economic Freedom, provided by the Heritage Foundation, for the most recent years, in order to analyse how is this measure related to the Inward Foreign Direct Investment Performance Index, as provided by the UNCTAD. Given the subjectivity of economic freedom, an appropriate methodology consists on using fuzzy logic clustering [12], which is applied in the paper in order to verify how different is the MENA region from the set of EU-member states. The aim is to investigate whether there are region-specific factors in the economic freedom that are significant for FDI performance. The accomplishment of this objective adds to the literature given the methodology that is applied in the paper.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 briefly presents the empirical literature linking economic freedom issues and inward FDI, emphasizing the research on the MENA countries. Section 3 comments some descriptive statistics on the economic freedom and foreign direct investment in the MENA region and in the EU members. Section 4 explains the methodological aspects related to the data and the fuzzy logic technique analyses how economic freedom exerts influence on the FDI. Given that a certain level of perceived economic freedom can, in fact, be subject to different subjective evaluations by investors, the paper uses a fuzzy logic approach in order to determine conceivable clusters in the space economic freedom-FDI, which is done in Section 5. Section 6 presents some concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

The literature is mainly dedicated to study the impact of the economic freedom on inward FDI flows. For a number of reasons, the transparency in economic policies is an essential issue for investors, especially for foreigners. The lack of these conditions imposes extra costs to the firms, linked to the lack of information about activities or even future intentions of some governmental departments. Thus, the selection of investment location is, sometimes, biased for the presence of non-economic elements. So, a steady and actively legal framework against the corruption and promoting economic freedom can, in fact, represent a factor of attractiveness for FDI.

The positive interaction between economic freedom and FDI atractiveness is due to, in the first place, the fact that free markets promote a better factor allocation and stimulate the productivity and the investments profitability. In the second place, since FDI involve significant sunk costs (particularly the greenfield), investments become very sensitive to the degree of stability and security offered by the legal protection system of the intellectual property rights. So, the existence of clear and predictable economic policies related to liberalizing regimes of investment and trade can be powerful instruments in the way to attract FDI flows [13].

The OLI paradigm [14] is a milestone reference in the theoretical and empirical approaches of the FDI. This paradigm sustains that firm decisions in relation to foreign markets depends on the economic and institutional conditions in home and host countries. In concrete, the decision to invest in a foreign country needs the firm boast, simultaneously, three types of advantages: ownership (O), location (L) and internalization (I). The ownership advantages reveal to be a basic condition for that the firm explore it in any market. Also, the choice of the location is conditional on the existence of structural market imperfections or from specific factor endowments, being mostly relevant the risk that firm incurs when dislocating to an unknown market. Finally, firms internalize their own markets of intermediate goods, whenever the costs of transaction in the markets surpass the coordination costs that the company supports for the internal accomplishment of this type of activities.

Later, the new concept of “capitalism of alliances”, based in the mutual trust, commitments and the contractual obligations between partners, widens the original scope of the OLI Paradigm [15]. In this sense, reciprocal trust may be a key instrumental issue for the firms’ potential success. The inclusion of economic freedom issues turned to be considered in an explicit form, given its impacts on the confidence level of the agents (see [16]). This Paradigm has been important to understand the multinationals behaviour, its usefulness being able to be strengthened by the inclusion of the freedom and its impacts on FDI. In fact, this issue basically affects the location dimension and it motivates firms to reduce the degree of uncertainty associated with its entrance in a foreign market.

The linkages between FDI flows and political risk and institutions are explored by Busse and Carsten [17] for a large sample of 83 developing countries, taking into account 12 different indicators for the period 1984 to 2003. They found that the investment profile, internal and external conflict, ethnic tensions and democratic accountability are significant determinants of FDI flows. Across different econometric models, the relative magnitude of the coefficients for these political indicators are largest for government stability and law/order, suggesting that changes in these components are greatly relevant for investment decisions of multinationals.

A more recent study is provided by Dumludag et al. [19], who investigate the relationship between FDI flows and institutions in several emerging markets, employing a panel data approach from 1992 to 2004. The sociopolitical variables include juridical system, corruption, investment profile, government stability, economic, social and political risks. Those authors wrap up that institutional variables are important, particularly corruption, investment profile and government stability.

Despite those approaches, the impact of institutional differences between the home and the host countries has been little researched so far. Yet, in a recent study, using a database provided by the French Ministry of Finance network in 52 countries and the Fraser Institute database, Bénassy-Quéré et al. [20] examine the role of institutions in the both host and source country by estimating a gravity equation for bilateral FDI stocks that includes governance indicators. The analysis provides abundant evidence to carry on the idea by which institutions do matter whatever the countries development level. In fact, results show that inward FDI is positively affected by public efficiency, which includes tax system, transparency and lack of corruption, security property rights and the easiness to create a business.

In sum, literature recognizes the importance of institutional variables in empiric studies, providing support for the idea that an efficient legal and social framework promotes economic freedom and reduces uncertainties. So, most of the studies conclude that the protection of intellectual property rights, low corruption levels, enforcement mechanisms and political stability influences positively the FDI inward flows and the economic growth3. In fact, when these conditions do not exist in a country, foreign investors can face particularly high costs in establishing an operation and inhibit FDI inflows.

Despite the lack of research on determinants of FDI in MENA countries, recent studies have analysed this issue by using different methodologies and data sets. All these studies share the idea that FDI for these countries is low when compared with other developing countries. In addition, most of them concentrate on the importance of the institutional issues for the FDI inflows in these countries, concluding that institutions are vital to explain the poor performance of the MENA region in attracting FDI.

An early analysis is performed by Kamaly [21], who uses a dynamic panel model for the period 1990 to 1999. In this study, economic growth and the lagged value of FDI/GDP were the only significant determinants of FDI flows to the MENA region. However, this approach, as are most other studies on FDI in developing countries, does not cover the recent period and uses a small sample, thus raising questions about the consistency and efficiency of the coefficients of the dynamic model. Also, it does not consider the institutional factors that affect FDI flows to the MENA region.

By using a fixed effects panel data model for the period 1975 to 1999, Onyeiwu [22] compares 10 MENA countries with other developing countries, including in the study institutional aspects that may affect FDI flows to the region. He concludes that corruption is, in general, significant for all the developing countries and, in the case of the MENA countries; it is the only significant variable in explaining FDI inflows. However, the author uses government expenditure over GDP as proxy for corruption, which might not be the appropriate measure for this variable.

Chan and Gemayel [23] study the relation between macroeconomic instability and FDI in the MENA region. They employ two dynamic panel data models using two groups: one with 19 MENA countries and the other with 14 EU countries as well as Canada and USA. Their results show that the instability has a much stronger impact on FDI than risk itself, being this particularly important for the MENA region. However, the study suffers from the weak consistency of the coefficients in the dynamic models, because the sample data is not large enough to be confident on the results and the applied estimation methods are not the appropriate ones for obtaining consistent estimates in a dynamic panel data model.

Other assessment on the influence of quality of institutions on trade and FDI in MENA countries is developed by Méon and Sekkat [24], who includes data from 1990 to 1999, covering a large number of countries, including some MENA countries. They use some proxies the quality of institutions, namely corruption, political risk and governance. The results show a significant relationship between political risk and inward FDI, but failed to find clear evidence of a significant relationship between corruption and FDI flows. In fact, they employ different indicators of corruption and conclude that the results are sensitive to the index used to measure corruption. In the same line, applying the Kaufmann et al. [25] governance indexes, Daniele and Marani [26] look into the role of the quality of institutions on FDI, through a cross sectional regression analysis for 129 countries to the period 1995-2004, concluding that institutions are crucial to explain the performances of countries in attracting FDI.

Kobeissi [27] performed a testing on the impact of some non-traditional factors on foreign investment in MENA countries, focusing on factors such as governance, legal environment, and economic freedom, based on the indicators provided by the Heritage Foundation. The results reveal a consistent support for the positive impact of governance, legal system and economic freedom on the FDI flows in the MENA region, but the governance showed the most significant results followed by legal system and then economic freedom. The relatively lower importance of the last two variables could be due to the fact that investors from different countries have varying degrees of tolerance for imperfections in the host country's investment environment.

Ferragina and Pastore [28] examines FDI flows from the EU to two neighbouring regions: Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and South Mediterranean (MED) countries (including some MENA countries), to verify whether there was any diversion effect on FDI flows following the CEE integration in the EU. They use a gravity type model and a panel data approach to study the determinants of bilateral FDI flows for the period 1994-2004. Among the explanatory variables are included some institutional and economic freedom issues. They conclude that there is no evidence of FDI diversion, but results also highlight that governance is highly significant with positive sign and the current and capital account restrictions are both negative and highly significant.

Finally, in a fresh study, Onyeiwu [11] uses a logit and cross-country regressions, for 61 MENA and non-MENA countries, to examine whether scarce investment in knowledge, technology, and human capital by MENA countries explains their sub-optimal FDI profile. Results from both models suggest that investment in knowledge and technology is not significant for the MENA country’s ability to attract an optimal level of FDI. To the contrary, openness of the economy, GDP per capita and political risks are more important to attract this kind of flows. So, one implication for MENA countries is that, despite their poor science and technology infrastructure, they could still attract FDI by promoting openness and political rights and civil liberties.

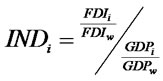

3. Discussion of the Data

Before presenting the methodological issues used in the paper we make a brief presentation of the variables included in that component and we will make an empirical analysis of trends observed over the period. In what concerns the FDI data, we use the inward FDI performance index provided by UNCTAD for the period 1999-2001 to 2004-2006, which ranks countries by the FDI they receive relative to their economic size. It is the ratio of a country’s share in global FDI inflows to its share in global GDP, that is  4. Thus, a value greater than 1 indicates that the country receives more FDI than its relative economic size, a value below 1 means that it receives less. The index thus captures the influence on FDI of factors other than market size, assuming that, other things being equal, economic size is the base line for attracting investment.

4. Thus, a value greater than 1 indicates that the country receives more FDI than its relative economic size, a value below 1 means that it receives less. The index thus captures the influence on FDI of factors other than market size, assuming that, other things being equal, economic size is the base line for attracting investment.

In this study we apply the Index of Economic Freedom provided by Heritage Foundation for 162 countries, for measuring economic freedom, which included 50 independent variables which fall into 10 categories of economic freedom. Each country receives its overall economic freedom score based on the simple average of the 10 individual factor score. Each factor is graded according to a unique scale, which runs from 1 to 5, where a score of 1 indicates an economic environment that are most conducive to economic freedom and a score of 5 signifies the opposite. The 10 variables included in the overall index are the follows5:

• Business freedom is the ability to create, operate, and close an enterprise quickly and easily. Burdensome, redundant regulatory rules are the most harmful barriers to business freedom.

• Trade freedom is a composite measure of the absence of tariff and non-tariff barriers that affect imports and exports of goods and services.

• Government size is defined to include all government expenditures, including consumption and transfers. Ideally, the state will provide only true public goods, with an absolute minimum of expenditure.

• Investment freedom is an assessment of the free flow of capital. This factor scrutinizes each country’s policies toward foreign investment, as well as its policies toward capital flows internally, in order to determine its overall investment climate.

• Property rights are an assessment of the ability of individuals to accumulate private property, secured by clear laws that are fully enforced by the state.

• Freedom from corruption is based on quantitative data that assess the perception of corruption in the business environment, including levels of governmental legal, judicial, and administrative corruption.

• Labour freedom is a composite measure of the ability of workers and businesses to interact without restriction by the state.

• Financial freedom is a measure of banking security as well as independence from government control; state ownership of banks and other financial institutions such as insurer and capital markets is an inefficient burden, and political favouritism has no place in a free capital market.

• Fiscal freedom is a measure of the burden of government from the revenue side and it includes both the tax burden in terms of the top tax rate on income and the overall amount of tax revenue as a portion of GDP.

• Monetary freedom combines a measure of price stability with an assessment of price controls, because both inflation and price controls distort market activity.

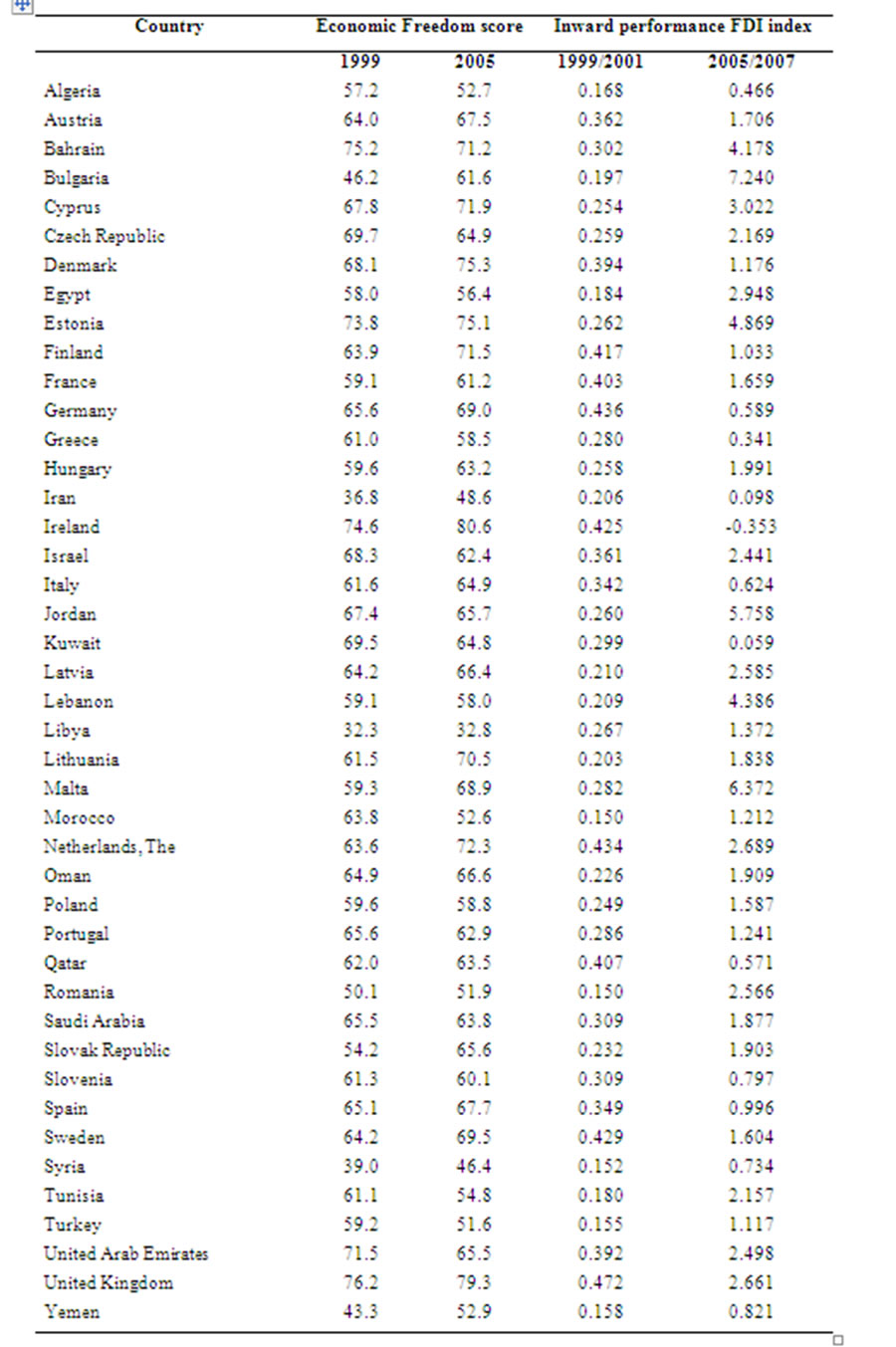

Data on these variables are presented in annex and the brief analysis of its trends allows us to emphasize the following points:

• Regarding the Inward FDI Performance Index we note that the EU presented an atractiveness clearly superior to the MENA region, with the average values in the range of 7 triennia because the EU almost double the figure recorded by MENA countries (2.12 and 1.23, respectively). However, when comparing the evolution between 1999-01 to 2005-07, the average value of that indicator for the MENA countries ore than quintupled (from 0.39 to 1.99), while for the EU growth was only 9% (from 1.94 to 2.12). As a result of such trends over the last period (2005-07) the average values of the two groups were approximated, showing the two regions as very attractive in world terms of attracting FDI flows.

• For the Index of Economic Freedom we found that the average of the period (1999-05) in the EU was around 14% higher than the recorded value in the MENA region, meaning that this gap has widened over that period, rising from 7.8% to 17.4% between 1999 and 2005, respectively. Although changes in the values for the two regions are not very significant in this period, we note that the average of the EU improved slightly (4.2%) and, in an opposite trend, worsened in the MENA region (-1.1%). We also note that the performance of countries within each group was very different and, in particular in the MENA, the dispersion was very significant, indicating the existence of very different situations as far as promoting economic freedom.

In summary, we believe that the dispersion found in the variables within the two groups over the period reflects a high diversity of countries performances in order to attract FDI flows and in promoting an economic freedom environment6. This is especially evident within the MENA countries where very different economic and institutional realities coexist. In fact, a number of countries in the region have paid special attention to making themselves investor-friendly by making the business environment more open and stepping up structural and institutional reforms, while others have been following other paths.

4. The Fuzzy Logic Approach

Given that, we think the purposes of the paper will be mainly achieved by the use of fuzzy clustering techniques, it is informative to start with a general discussion of this kind of approach.

Following the logic of crisp sets, the degree to which an element belongs to a set is either 1 or 0, by that meaning that the characteristic function discriminates respectively between members and non-members of the set in a crisp way. The generalisation to a fuzzy set is made by relaxing the strict separation between elements belonging or not to the set, allowing the degree of belonging/ membership to take more than these two values, typically by allowing any value in the closed interval [0,1] (see, for instance, [29,30]).

The values then assigned by the membership function of a fuzzy set to the elements in the set indicate the membership grade or degree of adherence of each element in the set. Larger (smaller) values naturally indicate higher (lower) membership grades, degrees, or consistency between an element of the set and the full characteristics that the set describes. Hence, using fuzzy logic, one can deal with reasoning like: ‘the observed value for the economic freedom index, say 5, can be considered high, normal or low with some degrees of membership’.

In terms of fuzzy logic, ‘high’, ‘normal’ or ‘low’ values (for the variable under question) can be considered to be subjective categories, as economic agents often evaluate those concepts differently. In what follows, it will be assumed that investors consider to be relevant their relative perception of economic freedom (in accordance to some subjective categories) for their willingness to invest, therefore assuming an approximate or qualitative reasoning.

In the particular case of this paper, we will use this kind of fuzzy logic reasoning to construct clusters in the space (FDI, Economic Freedom). This partition of the space can also be done in, say, a traditional/crisp way. The crisp/hard clusters algorithm tries to locate clusters in a multi-dimensional data space, U, such that each point or observation is assigned in that space to a particular cluster in accordance to a given criterion. Considering c clusters, the hard cluster technique is then based on a c-partition of the data space U into a family of clusters such that the set of clusters exhausts the whole universe, that a cluster can neither be empty nor contain all data samples, and that none of the clusters overlap.

Formally, the hard c-means algorithm finds a centre in each cluster, minimising an objective function of a distance measure. The objective function depends on the (Euclidean) distances between data vectors uk (k = 1, 2,…, K) and cluster centres ci. The partitioned clusters are typically defined by a c × K binary characteristic matrix M, called the membership matrix, where each element mik is 1 if the kth data point uk belongs to cluster i, and 0 otherwise. Since a data point can only belong to one cluster, the membership matrix M has the properties: (i) the sum of each column is one, and (ii) the sum of all elements is K.

The fuzzy c-means differs from hard c-means because it employs fuzzy partitioning, where a point can belong to several clusters with degrees of membership such that the membership matrix M is allowed to have elements in the range [0,1]. A point’s total membership to all clusters, however, must always be equal to unity. In this sense, and despite that, in formal terms, none of the fuzzy clusters overlap, the fact is that, in general, each data point is assigned to every cluster, although with different degrees of membership. Generally speaking, in visual terms, each data point is then associated to the particular cluster to which its degree of membership is higher.

5. How Different are the MENA Countries from the EU in Terms of the Relationship between Economic Freedom and FDI

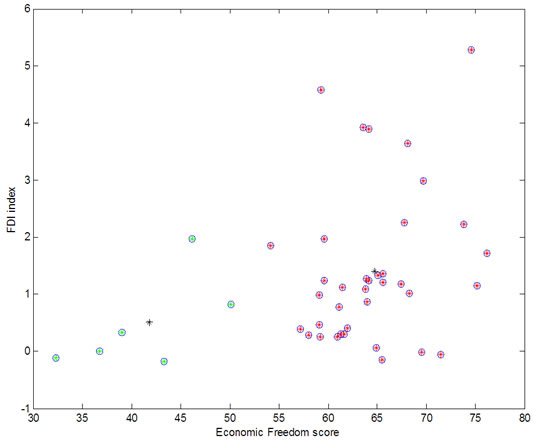

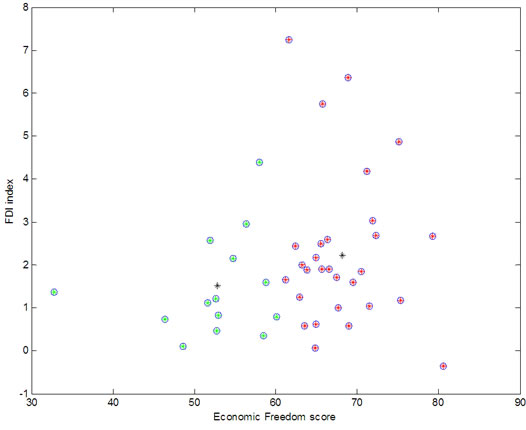

In this section we analyse a possible influence of economic freedom on FDI. Figures 1 and 2 plot the data and at the same time show the results from the fuzzy clustering technique7.

Plainly, there are two well-defined clusters (identified in figures 1 and 2 by the dotted circles and empty circles, whose centres are given by the black crosses), one being associated with the higher level of perceived economic freedom countries and another associated with the lower level perceived economic freedom countries. In fact, the splitting of the countries clearly reflects the economic freedom values as it seems possible to separate the two groups of countries in accordance to a, say, critical level of perceived economic freedom around 52 for the first period under analysis and 61 in the second period under analysis8.

Since the observed similarity between the results for the two periods, one can assert the robustness of the results. In fact, the clusters indicate a relationship between Economic Freedom and the Inward Performance of FDI, that is assumed to be of causal nature given the theoretical support of it. The results point to the fact that, in

Figure 1. The results for 1999/2001

Figure 2. The results for 2005/2007

overall terms, there is a direct relationship between Economic Freedom and the Inward Performance of FDI. This relationship is apparently stronger in the cluster of countries with higher economic freedom. In fact, as the level of economic freedom is decisive in the clustering, the overall increase that could be observed in the economic freedom from 1999/2001 to 2005/07 – which can be noted at the centre of the clusters in the two periods – led to a more homogeneous, from the point of view of the number of countries, clustering in that last period. Consequently, whereas in the first period, 4 out of the 6 countries in cluster 1 were MENA countries, in the second period, 10 out of the 14 countries in cluster 1 were MENA countries, despite the general increase in economic freedom and FDI inward performance that these countries registered from 1999/2001 to 2005/07.

6. Concluding Remarks

The results of the paper show that economic freedom and inward FDI are positively associated, in particular in the cluster of countries that present a higher economic freedom. Of particular interest is the result that some MENA countries belong to the same cluster of most of the EU-countries.

To conclude we would like to stress the main lesson from our paper as a policy implication. In order not to be considered less attractive for foreign investors and, therefore, be penalised by that, countries do indeed benefit from increased levels of transparency in order to escape from the cluster of countries where perceived levels of economic freedom are smaller. In other words, policy makers should make sure that their policies are transparent enough for potential foreign investors. After escaping from that cluster, the objective of attracting higher levels of FDI has to be crucially obtained by the use of other measures.

In the context of Dunning’s framework, we could understand the results of our empirical research as supporting the inclusion of economic freedom in the set of the relevant elements for the location tier [14,15].

Given that (perceived) economic freedom reflects a variety of factors–which are clear even in the way the economic freedom data is obtained – an interesting issue to be further explored is the analysis of the specific factors or components that assume a more significant role on the attraction of FDI.

An analysis of the dynamics of the components of economic freedom or even of economic freedom itself seems to be a quite plausible improvement as the direction assumed by policy makers towards more transparent policies may have a marginal impact on the attraction of FDI much more evident than one may expect by the analysis of the absolute position of economic freedom. Straightforwardly, the more those measures are assumed to be credible by foreign investors, the more that can be the case.

Finally, we consider this paper as a promising starting point for the analysis of the factors that reveal to be essential for FDI, either in an inward perspective or in an outward perspective, both in performance and potential measures. The combination of all these perspectives, in a dynamic way, is to be considered in future studies. As a matter of fact, this kind of analysis can easily be extended to other set of countries that show some empirical support for the existence of a relationship between institutional factors and investment decisions. Furthermore, the inclusion of geographical factors, in what concerns the localization of the host countries and of investors, in those dynamics is also in our mind as relevant elements.

REFERENCES

- O’Doriscoll, et al., “Index of economic freedom,” Heritage Foundation and Wall Street Journal, NewYork, 2001

- Berggren, N., “The benefits of economic freedom—A survey,” The Independent Review, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 193–211, Fall 2003,http://www.ratio.se/pdf/wp/nb_efi.pdf. 2003.

- UNCTAD, “World investment report 2008: Transnational corporations and the infrastructure challenge,” Geneva, UNCTAD-United Nations, 2008, http://www.unctad.org/Templates/WebFlyer.asp?intItemID=4629&lang=1.

- Adkins, L. et al., “Institutions, freedom, and technical efficiency,” Southern Economic Journal, No. 69, pp. 92– 108, July 2002.

- Weede, E. and Kämpf, S., “The impact of intelligence and institutional improvements on economic growth,” Kyklos, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 361–80, 2002.

- Sekkat, K. and Veganzones-Varoudakis, M., “Openness, investment climate, and fdi in developing countries,” Review of Development Economics, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 607–620, 2007.

- Globerman, S. and Shapiro, D., “Governance infrastructure and U.S. foreign direct investment,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 3, pp. 19–39, 2003.

- Gwartney, J., et al., “Economic freedom of the world: 2003 annual report,” The Fraser Institute, Calgary, 2003, http://www.freetheworld.com/release_2003.html

- Dunning, J., “Determinants of foreign direct investment globalization induced changes and the roles of FDI policies,” Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics, Europe 2002–2003: Toward Pro-Poor Policies-Aid, World Bank Publications.

- Becchetti, L. and Hasan, I., “The effects of (within and with EU) regional integration: Impact on real effective exchange rate volatility, institutional quality and growth for MENA countries, World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University, Research Paper No. 2005/73, 2004,http://www.wider.unu.edu/publications/working-papers/research-papers/2005/en_GB/rp2005–73/

- Onyeiwu, S., “Does investment in knowledge and technology spur ‘optimal’ FDI in the MENA region? Evidence from logit and cross-country regressions,” paper presented on 2008 African Economic Conference, promoted by The African Development Bank Group, November, Tunis, 2008, http://www.afdb.org/portal/page?_pageid=473,30752696&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL .

- Caetano, J. and Caleiro, A., “Corruption and foreign direct investment: What kind of relationship is there?” in R. Gupta, S. S. Mishra, The Causes and Combating Strategies, ICFAI Books, 2007.

- Drabek, Z. and Payne, W., “The impact of transparency on foreign direct investment,” World Trade Organization —Economic Research and Analysis Division, Working Paper ERAD-99-02, 2001, http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/wpaps_e.htm.

- Dunning, J., “The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 1–31, 1988.

- Dunning, J., “Reappraising the eclectic paradigm in the age of alliance capitalism,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 461–491, 1995.

- Voyer, P. and Beamish, P., “The effect of corruption on Japanese foreign direct investment,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 211–224, 2004.

- Busse, M. and Carsten, H., “Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment,” HWWA Discussion Paper 315, 2005, http://www.hwwa.de/Forschung/Publikationen/Discussion_Paper/2005/315.pdf.

- Graeff, P. and Mehlkopb, G., “The impact of economic freedom on corruption: Different patterns for rich and poor countries,” European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 19, pp. 605–620, 2003.

- Dumludag, D., et al., “Determinants of foreign direct investment: An institutionalist approach,” Seventh Conference of the European Historical Economics Society, Lund University, June 2007, http://www.ekh.lu.se/ehes/paper/devrim_dumludag_EHES2007_paper_new.pdf.

- Bénassy-Quéré, et al., “Institutional determinants of foreign direct investment,” The World Economy, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 764–782, 2007.

- Kamaly, “Evaluation of FDI flows into the MENA region,” The Economic Research Forum, Working Paper Series, Cairo, 2002, http://www.erf.org.eg/CMS/getFile.php?id=694.

- Onyeiwu, S., “Analysis of FDI flows in developing countries: Is the MENA region different?” Selected Published Papers from the Tenth Annual Conference of the Economic Research Forum, Cairo, Egypt, pp. 165–182, 2004, http://www.mafhoum.com/press6/172E11.pdf.

- Chan, K. and Gemayel, E., “Risk instability and the pattern of foreign direct investment in the middle east and north africa region,” International Monetary Fund, IMF Working Paper 04-139, 2004.http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2004/wp04139.pdf.

- Méon, P. and Sekkat, K., “Does the quality of institutions limit the MENA’s integration in the world economy?” The World Economy, Vol. 27, No. 9, pp. 1475–1498. 2004.

- Kaufman, D., et al., “Governance matters IV: Governance indicators for 1996-2004,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 3630, Washington, D.C., 2005, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=718081.

- Daniele, V. and Marani, U., “Do institutions matter for FDI? A comparative analysis for the MENA countries,” MPRA paper No. 2426, 2007, http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/2426/1/MPRA_paper_2426.pdf.

- Kobeissi, N., “Impact of governance, legal system and economic freedom on foreign investment in the MENA region,” Journal of Comparative International Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2005.

- Ferragina, A. and Pastore, F., “FDI potential and shortfalls in the med and ceec´s: determinants and Diversion Effects,” paper presented at XVI Conferenza Scientifica Nazionale AISSEC, Parma, 2006, https://dspace-nipr.cilea.it/bitstream/1889/886/1/Ferragina_Pastore_Aissec_07.pdf.

- Zimmermann, H. J., “Fuzzy set theory—and its applications,” 2nd Edition, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, 1991.

- Chen, C., “Fuzzy logic and neural network handbook,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 1996.

Annex: The data

NOTES

1The suggestions and remarks of an anonymous referee are gratefully acknowledged.

2From 1980 to 2004, the share of developing countries in the world FDI flows evolved by 25% to 44%, which means a significant evolution. However, data for 2007 displayed an erosion of this share for 27.3% [3].

3Literature has also been paying attention to the relationship between economic freedom and corruption. Graeff and Mehlkop [18] identify a stable pattern of aspects of economic freedom influencing corruption that differs depending on whether countries are rich or poor. So, despite there is a strong relation between economic freedom and corruption, this relation depends on a country’s level of development and, contrary to what is expectated, they find that some types of regulation reduce corruption.

4Where INDi is the inward FDI performance index of the i-th country, FDIi is the FDI inflows in the i-th country, FDIw is the world FDI inflows, GDPi is the GDP in the i-th country and GDPw is the world GDP.

5For a detailed information, see the document Methodology: Measuring the 10 Economic Freedom, disponível no site da Heritage Foundation. http://www.heritage.org/research/features/index/chapters/pdf/Index2008_Chap4.pdf.

6For example, some countries in the Persian Gufl (Bahrain and United Arab Emirates), Jordan and Lebanon have been revealing in recent years a high capacity to attract FDI flows. Interestingly, these countries, with the exception of Lebanon, are in the group that presents a higher position in relation to index of economic freedom.

7The data can be consulted in the annex. The source of the economic freedom data is the Heritage Foundation (http://www.heritage.org/ research/features/index/downloads.cfm) and the source of the FDI performance index is the UNCTAD (http://www.unctad.org/Templates/WebFlyer.asp?intItemID=2471&lang=1).

8This result makes it quite easy to identify the countries in each cluster (see the annex).