Health

Vol.5 No.11(2013), Article ID:39455,10 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.511236

Patients’ perceptions, health and psychological changes with obesity treatment: Success and failure in a triangulation study*

![]()

1School of Management and Industrial Studies, Institute Polytechnic of Porto, Porto, Portugal;

#Corresponding Author: susanasofiapsilva@gmail.com, angelam@psi.uminho.pt

2Center for Research in Psychology, School of Psychology, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

Copyright © 2013 Susana Sofia Pereira da Silva, Ângela da Costa Maia. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 29 July 2013; revised 29 August 2013; accepted 15 September 2013

Keywords: Bariatric Surgery; Success; Longitudinal Study

ABSTRACT

The present study aims to understand changes in health problems, health complaints and coping strategies, during the obesity treatment process with qualitative and quantitative data. Thirty bariatric patients were interviewed before bariatric surgery and at a 12-month follow-up, and fulfilled self-report measures about health problems, health complaints and coping strategies before surgery, at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Before surgery, failure cases differ from success on the conceptualization of obesity, However, there are no other differences between groups. At 6- and 12-month follow-ups, failure cases had the highest BMI, health problems and complaints and less % EWL than success cases. One year after the surgery, one in each three persons did not lose the expected weight, i.e., are failure cases. Before surgery, there are no differences between success and failure cases in the report of health problems, health complaints and coping strategies, but they have different conceptualizations of their obesity and treatment. One year after the surgery, success cases understood bariatric surgery as an important moment in their lives related to their expected results, whereas failures valued unexpected dimensions and still waiting for a miracle surgery without their personal commitment. Accordingly, it is necessary to consider lifestyle changes in the obesity treatment process.

1. INTRODUCTION

Obesity has increased all over the world, and, in developed countries, it is estimated that 10% - 20% of the adult population has this chronic disease [1].

The impact of morbid obesity and comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, dyslipidemia, low self-esteem, increase of morbidity and mortality is presented as a common problem among these subjects and has been studied by several authors [2-4]. The treatment of this multifactorial disease has become a challenge to health professionals and researchers. One of the most effective methods for significant and durable weight loss is treatment that includes bariatric surgery, a procedure that has been associated with several ameliorations in health condition as well as improvements in personal and social dimensions [5]. However, the outcomes of this procedure are not always successful and some failure cases have been reported [6,7] highlighting the importance of a multidisciplinary intervention that prioritizes lifestyle change.

Considering the relevance to better understand this global epidemic and the best way to deal with it, different authors [8-12] have studied the characteristics of obesity and the treatment outcomes. If the data of several studies are consensual regarding health improvements after surgery weight loss [8-10], then that is not the case for medium and long-term consequences [11-13]. Different authors [11-13] reported controversial data, suggesting the need for more studies to contribute to a better knowledge of the obese population and the treatment process. For example, Lier and colleagues [14], in a recent study, concluded that obese patients report more psychiatric disorders than community samples. In their study 43% of 141 patients that were evaluated had a current Axis I psychiatric disorder, and 26% an Axis II personality disorder. On the other hand, Mitchell and Zwaan [15] found that obese patients do not have more psychopathology than community subjects.

In the same way, there is little information about coping mechanisms and their efficacy after bariatric surgery [16]. Fischer and colleagues [17] found that emotional eating, i.e., eating in response to moderate emotional states, is frequent among obese subjects and that the practice of emotional eating can obstruct positive surgery outcomes. In this study, Fischer and colleagues [17] evaluated 144 gastric bypass patients before surgery and concluded that no statistically significant differences in BMI existed between high and low emotional eaters. However, high emotional eaters reported significantly higher rates of eating. On the other hand, Delin and colleagues [18] evaluated 20 patients two years after bariatric surgery and found that emotional eating was negatively associated with weight loss.

Additionally, a good number of studies were conducted after surgery but only few [19,20] have tried to comprehend obese characteristics before bariatric surgery, a fact that was recognized by Engström and colleagues [20] as a weakness in the literature. These authors referred explicitly to the urgency to conduct studies before surgery.

On the other hand, and independently of the evaluation time, most studies have been done using a quantitative paradigm. This is an important approach, providing relevant data based on the evaluation of several participants, allowing data generalization. However, despite the massive amount of data, several questions remained unanswered, namely the participant’s voice and perspective about obesity and treatment. Only more recently have researchers [7,12,16] recognized the importance of understanding patients’ perceptions, beliefs and expectations about obesity and its treatment. Qualitative research offers the richness of detail currently missing in the literature.

Both quantitative and qualitative approaches have made important contributions to comprehension of obesity. According to the “paradigm of choices” [21], the methodological orthodoxy that opposes quantitative to qualitative approaches should be rejected in favor of methodological appropriateness as the primary criterion for judging methodological quality. This paradigm recognizes that different methods are appropriate in different situations and to answer different research questions.

Triangulation has been suggested as a way to increase the understanding of factors influencing health status by combining research strategies to achieve a multi-dimensional view of the phenomena of interest [22]. Triangulation can include the use of multiple methods, i.e. the use of two methodologies (quantitative and qualitative), because each taps a different aspect or dimension of the problem being studied [22].

The triangulation study that we present here aims to improve on understanding of the personal expectancies and perceptions, as well as the health and psychological changes during the obesity treatment process. The main objective of the study is to comprehend if success and failure subjects differ before surgery, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups and to what extent they are distinguishable, considering quantitative and qualitative dimensions. For the quantitative analysis we consider BMI, coping strategies, health problems and complaints in the three evaluations times. Triangulated with this quantitative data collection, qualitative interviews before surgery and at the 12-month follow-up were analyzed with grounded theory procedure, in order to understand how the obese think about their obesity and what they expect and think about obesity treatment, specially focusing on perceptions and beliefs about the demands and impact of bariatric surgery. These last questions aim to contribute to the comprehension of the adaptation process after the surgery.

2. RESEARCH DESIGN

2.1. Study Design

Our objective in this triangulation research project was to understand personal expectancies and perceptions before and after bariatric surgery, and to characterize health and psychological characteristics before surgery (time 1), at the six- (time 2) and 12-month (time 3) follow-ups, comparing success and failure participants.

This study included 30 patients in the Multidisciplinary Treatment Center of Obesity in northern Portugal, divided in two groups according to the outcomes 12 months after the surgery: the success group (lost at least 50% excess weight loss-EWL) included 10 (seven women and three men) patients and a failure group (EWL < 50%) with 20 (13 women and seven men) patients. All of the patients that underwent bariatric surgery between June 2008 and June 2009 were assessed. The participants signed an informed consent form that gave permission for the subjects to be included in the study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital.

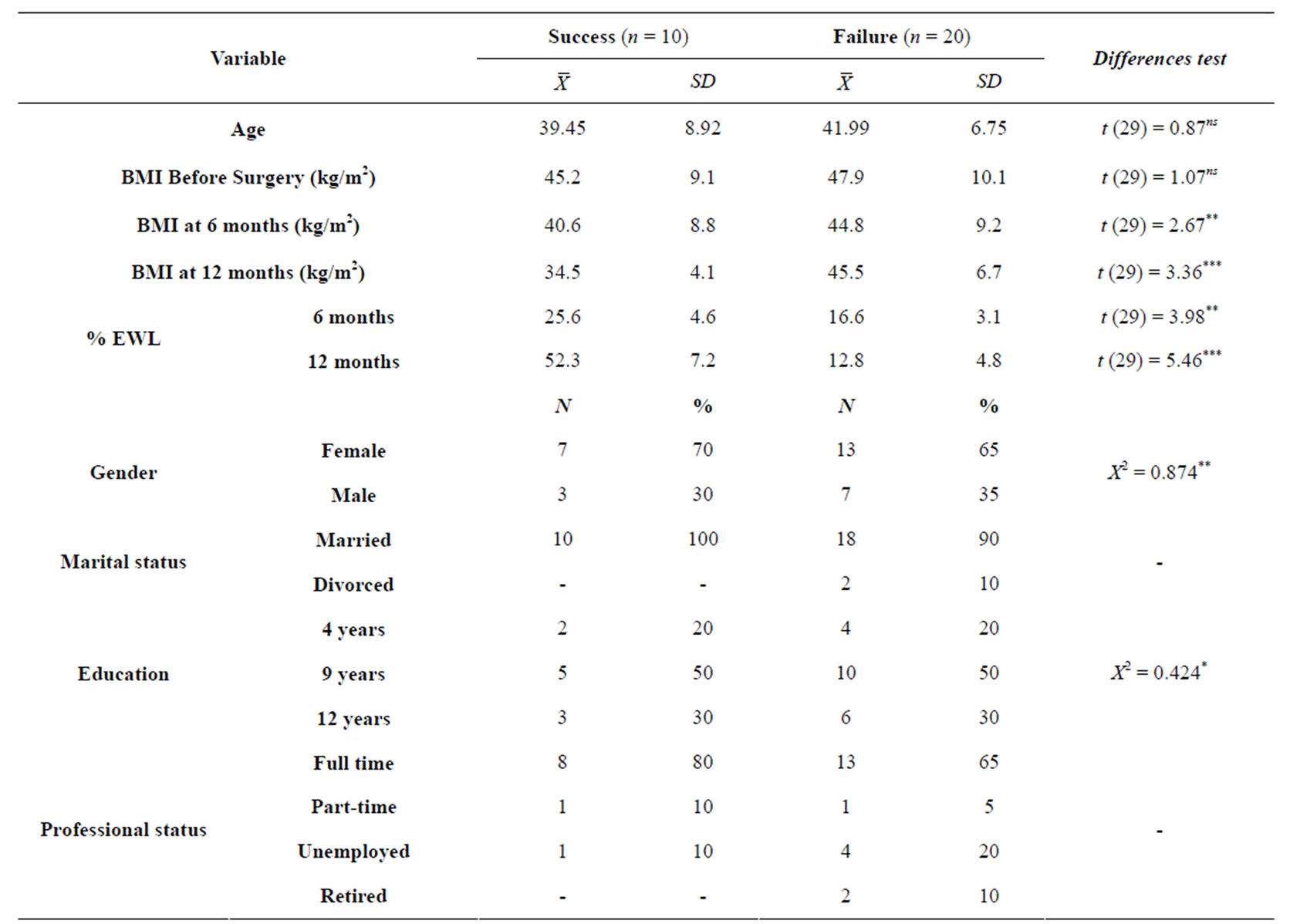

Table 1 shows the main socio-demographic characteristics of each group of the sample.

2.2. Quantitative Measures

Socio-Demographic Questionnaire [23]: a self-report questionnaire assessing socio-demographic information, including gender, age, education, weight and marital and

Table 1. Socio-demographic characterization of the sample.

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, nsno significance.

professional status.

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) [24]: a selfreport instrument that identifies the thoughts and actions individuals use to cope with stressful situations. This version has 44 items, and the answers are rated by the Parkes [25] method, which adds “1” point for the marked items and “0” points for the unmarked ones. This instrument has a global scale: general coping, i.e., all selected coping strategies, including appropriate and inappropriate ones. A sample of 86 healthcare professionals took part in the WCQ validation for the Portuguese population, and the internal consistency analysis showed good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for the general coping scale). In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Rotterdam Symptoms Checklist (RSCL) [26,27]: a 30-item instrument that measures the subjects’ psychological and physical morbidity by analyzing the intensity of the symptoms on a four-point Likert scale. In this study, we only used the physical morbidity scale, and given the specific characteristics of the obese population, the new item “joint pain” was introduced. This checklist has good psychometric qualities (for the global scale, Cronbach’s α = 0.91, and for the physical and psychological morbidity scale, Cronbach’s α = 0.86 and 0.88, respectively). In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the physical morbidity scale was 0.85.

Self-Report Diseases Checklist [28]: a list of 14 diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, and sleep apnea syndrome. An index of the total health problems of each individual was compute, varying from 0 to 14.

2.3. Qualitative Analyses

In order to understand expectancies, perceptions and beliefs about obesity and treatment before surgery, inducted directly from the patients’ perspective, we conducted interviews at the hospital. These interviews lasted from 20 to 80 minutes and included open-ended questions such as “How was to you living with the weight gain?”, “What led you to seek this treatment?” and “How is your relationship with food?” “What do you expect to happen after surgery?” All interviews were audiotaped, verbatim transcribed and analyzed according to the grounded theory procedures [29].

Towards to comprehend how patients understand the non-surgical factors that may contribute to the long-term success and failure of these procedure, namely their expectations, beliefs, difficulties and challenges, we performed interviews at 12 months follow-up. The interviews lasted from 20 to 70 minutes and included openended questions, such as “at this moment, did you achieved your expectancy?”, “how do you describe your eating behavior?” and “how do you describe the treatment process?” All interviews were audiotaped, verbatim transcribed and analyzed according to the grounded analysis procedures [15].

2.4. Data Analysis

We created two different groups: success and failure, according to the % EWL at 12-month follow-up: success group if participants had lost at least 50% EWL and failure group if subjects had lost less than 50% EWL. Quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed according to this group distribution.

Quantitative data were analyzed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.0. Univariate and bivariate statistical analyses were performed. Prior to analysis, all continuous variables were assessed for normality using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the results showed that the criteria for normality were not satisfied. In order to analyze differences in quantitative variables that measure current functioning we performed Mann-Whitney test for two independent samples.

Interview data was analyzed using the grounded theory method of qualitative research [29-32]. The basic premise essential to grounded theory is that the theory must emerge from the data rather than from preconceived notions formulated by the researcher. The data collection and analysis were deliberately interweaved, a process known as theoretical sampling, so that subsequent questions could be revised to reflect and check the emergent grounded theory [33].

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and consecutively analyzed with QSR NVivo 8.0 software according to the constant comparative method. Following these guidelines, the first step of the analysis was open coding. Data were examined line by line in order to identify the participants’ descriptions of thought patterns, feelings and actions related to the themes mentioned in the interviews. The derived codes were formulated in words closely resembling those used by the participants. This was an attempt to maintain the semantics of the data. Codes were compared to verify their descriptive content and to confirm that they were grounded in the data. As a second step the codes were sorted into categories. This was done by constant comparisons between categories, and between categories, codes and interview protocols. Data collected at later stages in the study were used to add, elaborate and saturate codes and categories. In practice, the steps of analysis were not strictly sequential; rather, we moved forward and backward, constantly reexamining data, codes, categories and the whole model.

Core categories were identified, allowing the attaching of all concepts together and unifying them in the grounded theory that permits understanding of the obesity phenomena. To ensure the validity of the analysis and the coding process, a second researcher was consulted as auditor throughout the entire data analysis process to assist the primary author by challenging ideas, assisting in the construction of the categories, and building the theory [29-32].

Matrix coding query or a cross tabulation (cross tab) analysis was used to show the joint distribution and to make comparison between success and failure group in relation to the main themes. Fischer Exact test was used to compare differences among the core qualitative categories at the surgery moment and at 12-month followup.

3. RESULTS

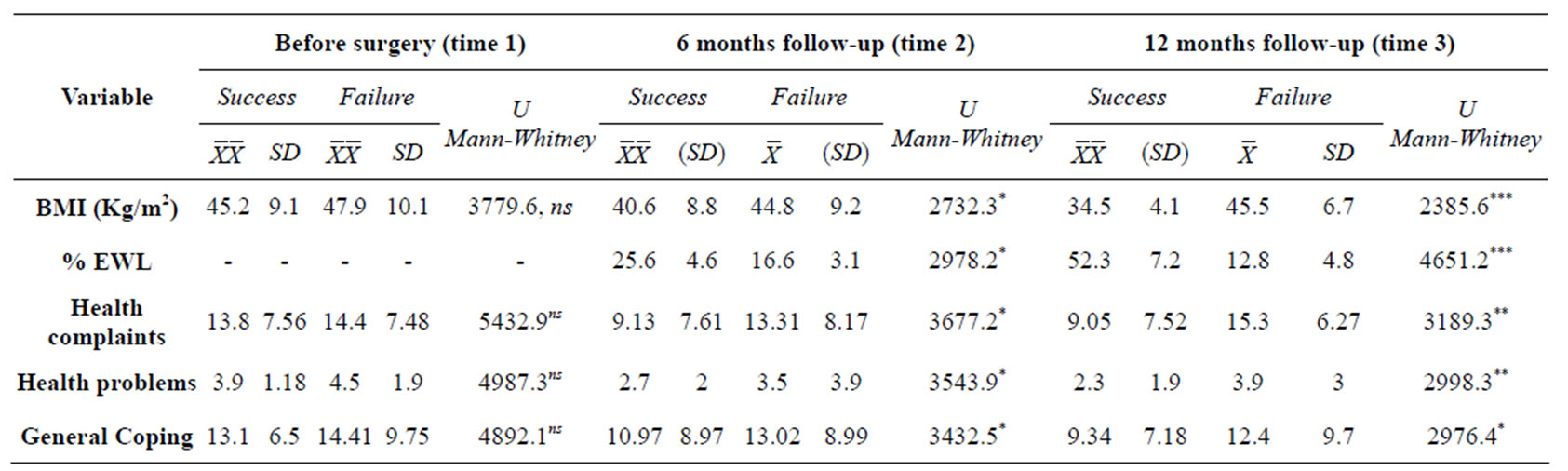

The quantitative data in Table 2 show that, before surgery, there were no differences in BMI, general coping, health complaints or health problems between the success group and the failure group.

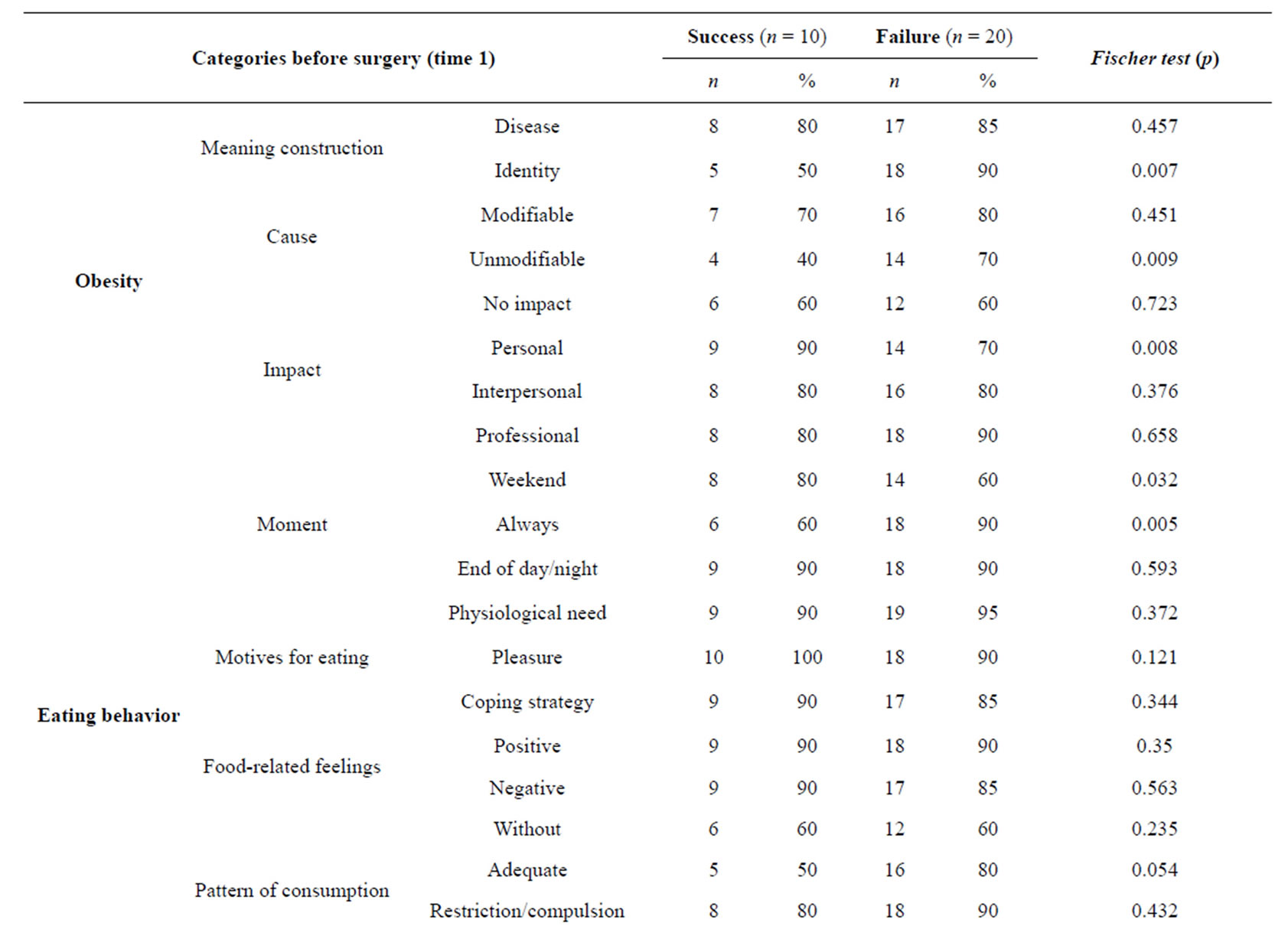

In the qualitative data, at this evaluation time, there were three core dimensions: obesity, eating behavior and treatment (Table 3). Obesity is, mainly, understood as disease or an internal immutable problem, affecting all life dimensions (professional, interpersonal and personal). Eating behavior seems to play an important role in the maintenance of obesity, and it is always present and controlling the patient’s life. At the same time, it is perceived as a coping strategy to deal with some events and imbued with negative feelings, and it is perceived as a loss of control. The treatment, especially the surgery, seems to be perceived as a miracle that will solve all life’s problems.

Before surgery subjects differ in the understanding of obesity, namely for the failure group obesity seems to be an identity and unmodifiable trait, i.e. a personal and immutable condition, whereas the success group highlight the personal impact of obesity in their lives.

In the eating behavior category, groups differ in the moment and in the pattern of consumption. Failures conceptualize their eating behavior as adequate, saying that they are always eating, while successes select the weekend as the special time for eating. For the treatment core category, groups are distinguishable in the categories “reference to multidisciplinary team” and “surgery”. The failure group describe that they were sent to the multidisciplinary team by health professionals, and con-

Table 2. Descriptive statistic for the different dimensions in the three evaluation moments and differences overtime.

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, nsno significance.

ceptualize the weight loss as an “obligation”. On the other hand, successes highlight the “family/friends” role in the reference to a multidisciplinary team, understand the surgery decision as an individual process where the person needs to have information, responsibility and power, and elect personal reasons to lose weight.

At the 6-month follow-ups (Table 2), the differences between groups were significant in all quantitative variables; namely, the failure group had higher BMI and lower % EWL. The mean of reported health complaints and problems, general psychopathology and general coping were significantly higher in the failure group.

In the same way, at the 12-month follow-ups (Table 2), differences remain between groups in all variables: the failure group had a higher BMI, general coping, health complaints and health problems and less % EWL.

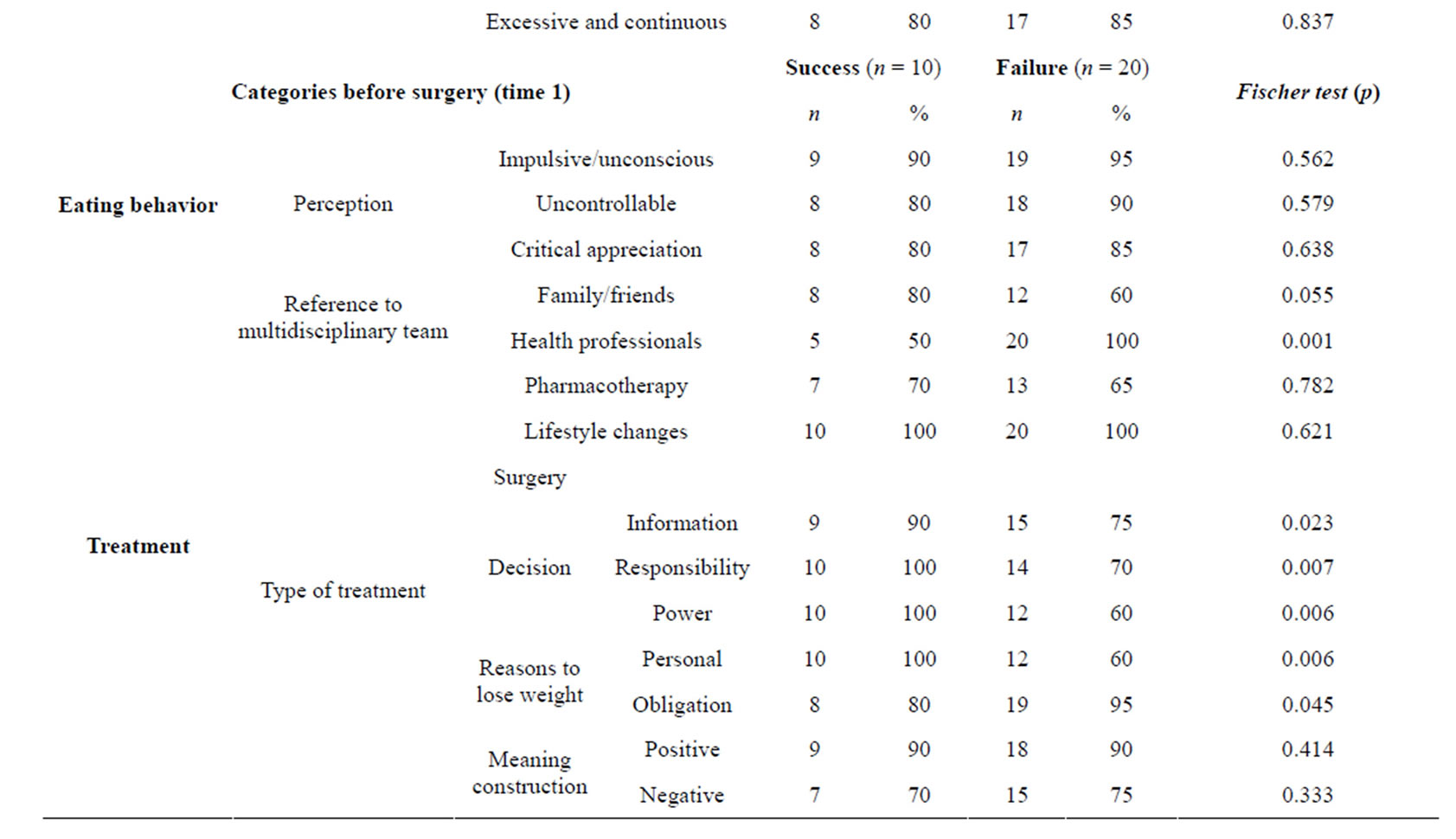

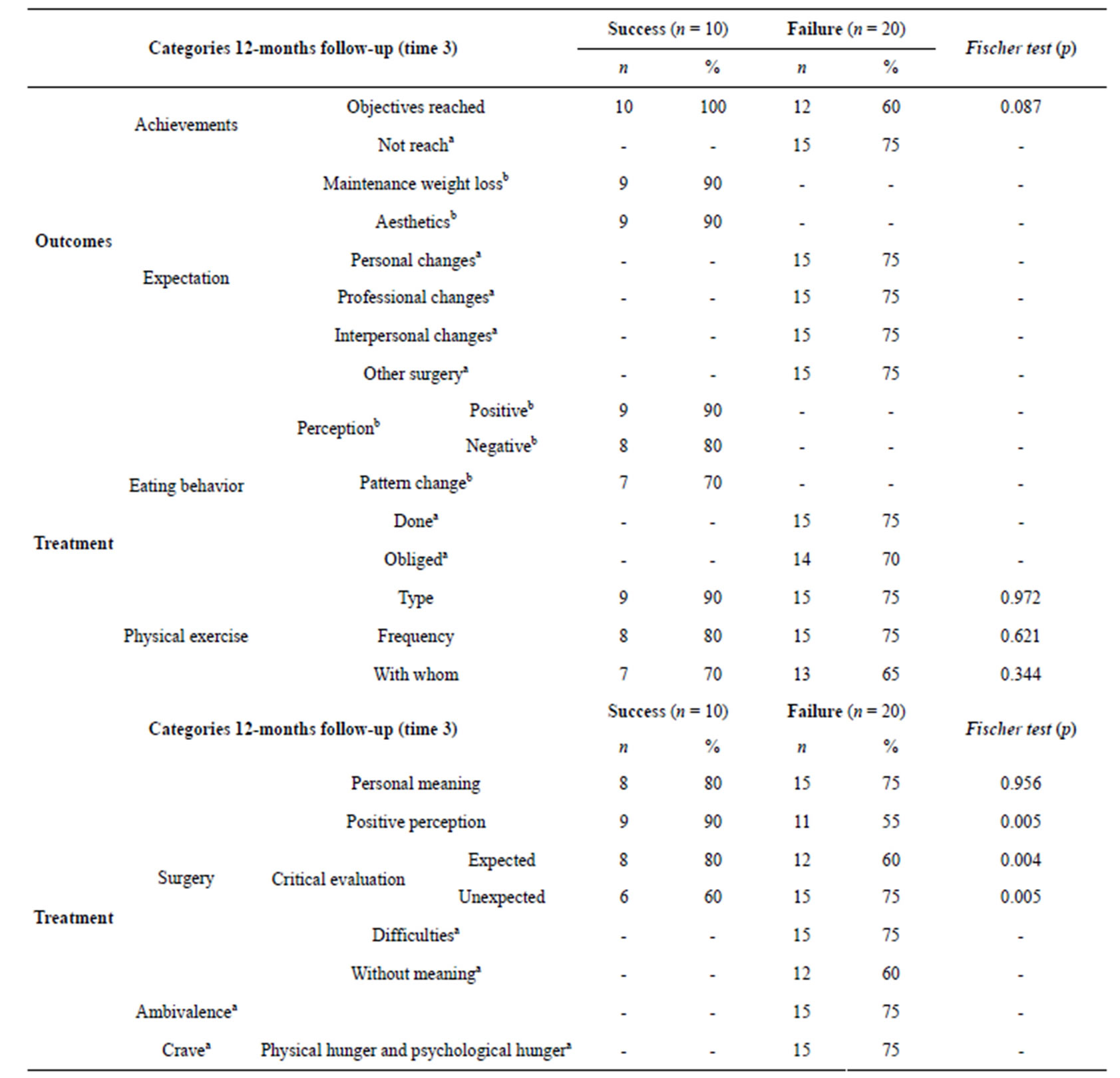

In the qualitative analysis, at this evaluation time (Table 4), patients describe themselves as cases of success or failure, with 15 persons each group. All the 10 participants that integrate the success group according to the criteria established in this study consider themselves as success cases, but five failure cases also consider themselves as success. In both self-defined groups two core categories emerged: “outcomes” and “treatment”, but the elements that compose the two categories are different in each group.

In the success group according to the patients’ selfdefinition, “outcomes” includes the objectives existing before surgery, that were achieved, and the objectives that they have for the future, mainly about weight maintenance and aesthetic issues. On the other side, for the failure group “outcomes” are organized in three sub-categories: those related to objectives that had been reached, those that had not been reached, and expectation about future changes that they would like to achieve through another bariatric surgery.

In the core category “treatment”, in the self-defined success group, eating behavior, physical exercise and surgery are described as three equally important elements. In the failure group, the surgery is the central aspect of treatment and participants reported the need for a different bariatric surgery technique, which they consider more appropriate to their own needs. In this group there was also some ambivalence between what they should be doing and their own behavior, and physical versus psychological hunger.

Matrix coding query (Table 4) shows the number and percentage of subjects’ coverage of the selected categories among success or failure as defined by our criteria, and differences between groups. One year after the surgery, some categories could not be statistically analyzed according to success/failure criteria because they only emerged in one of the groups. Only successes highlighted their preoccupation in maintaining the weight loss and some aesthetic issues related to body image and plastic surgery. On the other hand, they have both a positive and a negative perception of their eating behavior, recognizing its importance and the need to change their pattern according to the obesity treatment. Failures, but not successes, emphasized objectives not reached, the need of future changes (personal, interpersonal and professional) and the idealization of other surgery that would be more adequate to their needs. Only in unsuccessful cases eating behavior includes current eating behavior (“done”) and the obliged eating behavior, this last related to a huge sacrifice and to the health professional orientation. The surgery is also related to several difficulties and, in some failure patients’ words, did not have a specific meaning.

Ambivalence is another category that is only present in the failure group, i.e., there are some incongruence and inconsistency among their knowledge and their behavior, and a permanent struggle with physical hunger and psychological hunger.

When considering the statistical analysis in the categories of both groups, we only observe differences in the core category “treatment”, with success cases highlighting the positive perception and the expected difficulties

Table 3. Matrix coding query and differences between groups before surgery (time 1).

Table 4. Matrix coding query and differences between groups at 12-month follow-up (time 3).

Note: aonly referred for participants that describe themselves as a failure; bonly referred by participants that describe themselves as a success.

of the surgery. On the contrary, failure cases were distinguished in the unexpected difficulties of the surgery.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of our study suggest that there are differences among obese patients that can be related to the outcomes and should be considered during the obesity treatment, namely in the evaluation/preparation for the bariatric surgery.

Before surgery, success cases are characterized for low levels of psychopathology, high prevalence of health problems and complaints and use of several coping strategies. These subjects understand obesity as a disease affecting their life in several dimensions; namely personal, interpersonal and professional. These subjects elect the end of the day and weekends as times of eating compulsion related to different emotions. Eating behavior is a source of pleasure as well as a physiological need and a coping strategy, which is understood as an uncontrollable behavior. Family and friends seemed to be the main reference to a multidisciplinary team, and lifestyle changes are the principal treatment type where bariatric surgery has an important role, depending on personal commitment and the active involvement.

Failure cases also reported few psychopathology symptoms and had several health problems and complaints related to their obese condition, as also mentioned in other studies [34]. In these cases, obesity is understood as an identity trait and a disease, affecting the subjects’ life, especially professional life. Their eating behavior seems to be excessive, continuous, and understood, mainly, as a physiological need. Obesity treatment appears as an obligation imposed by health professionals. Despite life style changes are considered as a part of the treatment, surgery appears as the miracle that will solve all life problems whereas health professionals had the most important role.

Success and failure cases are not distinguishable before surgery by the BMI or any of the quantitative measures, such as general psychopathology, number of coping strategies or health problems or complaints. Regarding general psychopathology, our data suggested, as already stated in some literature [15,35] that obese patients report low levels of psychopathology and are not different from community subjects. Therefore, the groups can be differentiated according to the way they comprehend their obesity, eating behavior and treatment. Success cases seem to recognize that obesity has an important personal impact in their lives and specify the weekend as a “problematic” time, when they feel the need to eat more.

They also indicated the importance of family and friends in the referral to a multidisciplinary team. The surgery decision, namely the need for information, the responsibility and the power to decide is assigned to the person, suggesting an internal locus of control and personal commitment with the treatment. On the other hand, for failure cases, all issues related to obesity seemed to illustrate an external locus of control, with some unawareness of personal eating behavior pattern, as stated in previous literature [36]. Obesity is understood as an identity trait that is not modifiable, which only health professionals have the knowledge and the power to change. Therefore, the need to lose weight is conceptualized as an obligation. On the other hand, there is some evidence of the absence of critical evaluation of personal eating behavior, i.e. these patients describe their behavior as adequate, even after recognizing that they are always eating and have inadequate eating episodes.

At the 6-month follow-up, successes had lost 25% EWL, had normal levels of psychopathology [35] and reported less health problems and complaints resulting from the weight loss. On the other hand, failures lost 16% EWL, reported normal psychopathology levels and referred to the use of more coping strategies and health problems and complaints. At this evaluation time, there were differences between groups: success cases had a lower BMI and less psychopathology, health problems and complaints than failure cases. At the same way, success cases had a higher % EWL.

At the 12-month follow-up, successes had a BMI lower than 35 kg/m2 and lost more than 50% EWL (criteria to be included in the group), maintained normal levels of psychopathology, use less coping strategies, meaning that were more selective in the choice of these strategies, and reported less health problems and complaints. They reached their objectives, especially aesthetic changes, and the maintenance of weight loss. Treatment remains as a lifestyle change, whereas surgery was a positive and important role, as stated in other studies [12]. Failure cases remains as morbid obese subjects (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) and only lost 12% EWL. They reported normal psychopathology levels [35], more and undifferentiated coping strategies and referred to several health problems and complaints. Their main expectancies were not reached, and they are still waiting for a miracle surgery that will solve all their problems, and the unexpected dimensions and the difficulties resulting from these interventions are more valued than in the success cases. There is also huge ambivalence between their knowledge of healthy behavior and their current behavior, and between physical needs or hunger and psychological hunger or desire/eating pleasure.

At this evaluation time, the differences between groups increase, and failure cases have higher mean values for all dimensions-BMI, health problems and complaints when compared with success cases (except % EWL). Failure cases are also distinguishable from the success cases in surgery comprehension. In success cases, expected dimensions and a more positive perception of this surgery are highlighted, whereas failure patients give more attention to the unexpected dimensions. The failure group continue to suggest an external locus of control and a loss of control over eating [36], and subjects are still looking for a miracle surgery without learning with this process.

We should highlight that some failure subjects describe themselves as success cases, despite not fulfilling the demanded % EWL. This divergence in evaluation can be interpreted as a bias of some subjects that are still in the process of seeing themselves as q failure or, as suggested by other authors [19,20,37], % EWL should not be the only success criterion because, some patients, cannot achieve this goal, but still consider acquisitions with obesity treatment as successful. Moreover, patients seem to have difficulties in integrating all the information, they point out the difficulties, the obligation and the sacrifice but are satisfied with some of the results.

Our data shows that some areas, namely the way subjects understand their obesity, the absence of critical thought about their eating behavior and the idealization of the surgery, should be considered during the evaluation for obesity treatment, because they seem to be related to the outcomes. On the other hand, during obesity treatment, patients have different personal trajectories, with some patients understanding, acting and maintaining lifestyle changes, whereas others comprehend the need to change but remain at the same contemplation stage [3,38,39].

One of the limitations of our study is our small sample size. On the other hand, we only consider as a success criterion the % EWL because we only used self-report dimensions to evaluate health problems and complaints. Even with these limitations, our results showed the importance of integrating qualitative and quantitative methodologies because they can complement each other with their specificities and richness and give relevant orientations to evaluation and treatment. On the other hand, it is crucial to consider a longer follow-up. Our data showed that at 6- and 12-months follow-up, the failure group have more weight, health problems and complaints, while ameliorations are reinforced in the success group. However, the literature suggests that less favorable outcomes of bariatric surgery begin to emerge at 12- or 24-month follow-ups, reinforcing the need to maintain this evaluation. According to our data, it seems quite important to evaluate locus of control before and after surgery, as this appears to be condition to the treatment outcomes.

5. CONCLUSION

Resulting from this study, some implications should be considered for the evaluation and the treatment of obesity, because they can be related to the outcomes. Obesity treatment should be understood as a process that demands personal efforts where the individual has the principal power and health professionals are specialized members that will help giving orientation, but the individual is the expert. As stated by Kinzl [40], we also argue that bariatric surgery should be re-conceptualized; it is not the central intervention in obesity treatment, but a supportive intervention. The central issue is lifestyle change and maintenance, showing that it is not a circumstantial and time-limited treatment, but takes permanent work to change. Therefore, patients should commit to changes from the very beginning and maintain them for a considerable amount of time, because they are not only needed before surgery, but are also required every day in their life. In the same way, it is important to learn healthy eating habits, new coping strategies and adequate ways to deal with and regulate emotions, increasing the internal locus of control. And in the ones that are still not prepared for this commitment, the first work should have this taken into account and establish the reconceptualization of obesity and its treatment as the initial aim.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the Foundation for Science and Technology for financial support (SFRH/BD/37069/2007) for the study. To Dra. Aline Fernandes, Dra. Maria Lopes Pereira and Dr. Maia da Costa, members of the Multidisciplinary Evaluation Team for the Treatment of Obesity, and to the Hospital of Braga for their collaboration.

REFERENCES

- WHO (2004) WHO-special issue-diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Scientific Background Papers of the Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation, Geneva. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/PHNvol7no1afeb2004/en/index.html

- Segal, A., Cardeal, M. and Cordás, T. (2002) Obesity: Psychosocial and psychiatric aspects. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica, 29, 81-89.

- Prochaska, J.O., Norcross, J.C., Fowler, J.L., Follick, M.J. and Abrams, D.B. (1992) Attendance and outcome in a work site weight control program: Processes and stages of change as process and predictor variables. Addictive Behaviors, 17, 35-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(92)90051-V

- Fairbun, C. and Brownell K. (2002) Eating disorders and obesity. The Guilford Press, London.

- Buchwald, H., Avidor, Y., Braunwald, E., Jensen, M.D., Pories, W., Fahrbach, K., et al. (2004) Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 292, 1724- 1737. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.14.1724

- Holzwarth, R., Huber, D., Majkrzak, A. and Tareen, B. (2002) Outcome of gastric bypass patients. Obesity Surgery, 12, 261-264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/096089202762552476

- Kaly, P., Orellana, S., Torrella, T., Takagishi, C., Saff-Koche, L. and Murr, M. (2008) Unrealistic weight loss expectations in candidates for bariatric surgery. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 4, 6-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2007.10.012

- Steinmann, W.C., Suttmoeller, K., Chitima-Matsiga, R., Nagam, N., Suttmoeller, N.R. and Halstenson, N.A. (2011) Bariatric surgery: 1-year weight loss outcomes in patients with bipolar and other psychiatric disorders. Obesity Surgery. http://www.springerlink.com/content/qr27642621w31357/

- Kalarchian, M.A., Marcus, M.D., Wilson, G.T., Labouvie, E.W., Brolin, R.E. and LaMarca, L.B. (2002) Binge eating among gastric bypass patients at long-term follow-up. Obesity Surgery, 12, 270-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/096089202762552494

- Hörchner, R., Tuinebreijer, W. and Kelder, H. (2002) Eating patterns in morbidly obese patients before and after a gastric restrictive operation. Obesity Surgery, 12, 108-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/096089202321144676

- Sjöström, L., Narbro, K., Sjöström, C., Karason, K., Larsson, B., Wedel, H., et al. (2007) Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 741-752. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa066254

- Ogden, J., Clementi, C., Aylwin, S. and Patel, A. (2005) Exploring the impact of obesity surgery on patients’ health status: A quantitative and qualitative study. Obesity Surgery, 15, 266-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/0960892053268291

- Chantler, P. and Lakatta, E. (2009) Role of body size on cardiovascular function: Can we see the meat through the fat? Hypertension, 54, 459-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134452

- Lier, H., Biringer, E., Stubhaug, B., Eriksen, H.R. and Tangen, T. (2011) Psychiatric disorders and participation in preand postoperative counselling groups in bariatric surgery patients. Obesity Surgery, 21, 730-737. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0146-7

- Mitchell, J. and Zwaan, M. (2005) Bariatric surgery: A guide for mental health professional. Routledge, New York.

- Dodsworth, A., Warren-Forward, H. and Baines, S. (2010) Changes in eating behavior after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Surgery, 20, 1579-1593. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0270-4

- Fischer, S., Chen, E., Katterman, S., Roerhig, M., Bochierri-Ricciardi, L., Munoz, D., et al. (2007) Emotional eating in a morbidly obese bariatric surgery-seeking population. Obesity Surgery, 17, 778-784. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9143-x

- Delin, C., McK Watts, J. and Bassett, D. (1995) An exploration of the outcomes of gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: Patient characteristics and indices of success. Obesity Surgery, 5, 159-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/096089295765557962

- Van Gemert, W., Severeijins, R., Greve, J., Groenman, N. and Soeters, P. (1998) Psychological functioning of morbidly obese patients after surgical treatment. http://www.nature.com/ijo/journal/v22/n5/abs/0800599a.html

- Engstrom, M., Wiklund, M., Olsén, M., Lonroth, H. and Forserg, A. (2011) The meaning of awaiting bariatric surgery due to morbid obesity. The Open Nursing Journal, 1-8.

- Patton, M.Q. (1990) Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd Edition, Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Nakkash, R., Afifi Soweid, R.A., Nehlawi, M.T., ShediacRizkallah, M.C., Hajjar, T.A. and Khogali, M. (2003) The development of a feasible community-specific cardiovascular disease prevention program: Triangulation of methods and sources. Health Education & Behavior, 30, 723- 739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1090198103255521

- Silva, S. and Maia, A. (2008) Socio-demographic questionnaire.

- McIntyre, T., McIntyre, S. and Redondo, S. (1999) Portuguese version of ways of coping questionnaire.

- Parkes, K. (1984) Locus of control, cognitive appraisal, and coping in stressful episodes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 655-668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.655

- De Haes, J., Van Knippenberg, F. and Neijt, J. (1990) Measuring psychological and physical distress in cancer patients: Structure and application of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist. British Journal of Cancer, 62, 1034-1038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1990.434

- McIntyre, T. and Gameiro, J. (1997) Portuguese version of Rotterdam Symptoms Checklist (RSCL).

- Silva, S. and Maia, A. (2007) Self report diseases checklist.

- Silva, S. and Maia, A. (2012) Obesity and treatment meanings in bariatric surgery candidates: A qualitative study. Obesity Surgery, 22, 1714-1722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0716-y

- Silva, S. and Maia, A. (2013) Patients’ experiences after bariatric surgery: A qualitative study at 12-month follow-up. Clinical Obesity. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cob.12032

- Strauss, A.C. and Corbin, J.M. (1990) Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Corbin, J.M. and Strauss, A.C. (2007) Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd Edition, Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Richards, P.L. (2009) Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. 2nd Edition, Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks.

- Silva, S. and Maia, A. Psychological and health comorbilities before and after bariatric surgery: A longitudinal study.

- Torgerson, J. and Sjöström, L. (2001) The swedish obese subjects (SOS) study—Rationale and results. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 25, S2-S4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801687

- Kitsantas, A. (2000) The role of self-regulation strategies and self-efficacy perceptions in successful weight loss maintenance. Psychology & Health, 15, 811. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870440008405583

- Ogden, J., Clementi, C. and Aylwin, S. (2006) The impact of obesity surgery and the paradox of control: A qualitative study. Psychology & Health, 21, 273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14768320500129064

- Horwath, C.C. (1999) Applying the transtheoretical model to eating behaviour change: Challenges and opportunities. Nutrition Research Reviews, 12, 281-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/095442299108728965

- Prochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C. and Norcross, J.C. (1992) In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102-1114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102

- Kinzl, J.F. (2010) Morbid obesity: Significance of psychological treatment after bariatric surgery. Eating and Weight Disorders, 15, e275-e280.

NOTES

*Conflict of interest: The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.