Health

Vol. 4 No. 7 (2012) , Article ID: 21179 , 11 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2012.47059

Student capacity building of dengue prevention and control: A study of an Islamic school, Southern Thailand

![]()

1School of Nursing, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand;

*Corresponding Author: Scharuai@wu.ac.th

2Islamic School, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand

3Kumpangsou Local Administrative Organization, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand

4Ban Kank Community, Kumpangsou Sub-District, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand

5Ban Yanso Primary Health Center, Kumpangsou Sub-District, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand

6Communicable Disease Control Institute 11, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand

Received 12 March 2012; revised 3 May 2012; accepted 11 May 2012

Keywords: Student’s Capacity Building Process; Dengue Prevention and Control; Islamic School; Pondok

ABSTRACT

Dengue has been a critical problem for an Islamic School, Nakhon Si Thammarat province, Southern Thailand. Objectives: 1) to build student capacity; and 2) to evaluate the results of student capacity building. Method: Participatory Action Research: PAR was applied in three phases: 1) the school-based preparation phase; 2) the process of building student capacity phase, and 3) evaluation of the results of the student capacity building. Independent T-Test statistical method was used to analyze student capacity both before and after the intervention. Larval Indices were determined through ratio analysis. Results: Prior to the intervention, there was no clear strategy for combating dengue. In this study, three groups were formed to build student capacity: a leader group, a non-leader group, and a support group. The leader group (48 student leaders), critical to the study, was set as a dengue club named “Eliminate Ades Aegypti, the culprit of dengue” which focused on eight sets of activities: “Dengue or Death”, “Seniors educating juniors”, “Reward for good answers”, “Dengue monitoring team”, “Youth to expel mosquetoes”, “Mosquito or busy”, “Garbage elimination of Pondok”, and “Essential doctors”. The level of student capacity for the prevention and control of dengue of a sampling of 308 student representatives of the Pondok (Islamic school) showed an increase after intervention ( (SD); 56.78 (17.06); 65.33 (15.36) and different statistic significant (P < 0.001). The Larval in- dices ratio levels had decreased from the original levels (BI = 244, HI = 45, and CI = 26) after intervention (BI = 137, HI = 39, and CI = 19). Dengue morbidity and mortality rates were not found during the study. Discussion: Although there had been an increase in student capacity, a decrease in the larval indices ratio, and the absence of a dengue epidemiology index, the high risk of a dengue epidemic might still be found in the school because the ratio of larval indices were higher than the standard index. Then, the committed participation of students, school, and communities around the school vicinity is needed in building student capacity of dengue prevention and control.

(SD); 56.78 (17.06); 65.33 (15.36) and different statistic significant (P < 0.001). The Larval in- dices ratio levels had decreased from the original levels (BI = 244, HI = 45, and CI = 26) after intervention (BI = 137, HI = 39, and CI = 19). Dengue morbidity and mortality rates were not found during the study. Discussion: Although there had been an increase in student capacity, a decrease in the larval indices ratio, and the absence of a dengue epidemiology index, the high risk of a dengue epidemic might still be found in the school because the ratio of larval indices were higher than the standard index. Then, the committed participation of students, school, and communities around the school vicinity is needed in building student capacity of dengue prevention and control.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dengue is one of the most critical emerging tropical diseases [1]. In Thailand, dengue has been a significant public health problem for the past fifty years. Although the mortality rate has decreased in hospitals, the morbidity rate has unfortunately increased in all areas from 1998 to 2009. Southern Thailand, especially, has seen a higher incidence in dengue than other areas, possibly due to factors such as a greater number of rainy days, the amount of rainfall, the relative humidity, and a warmer temperature [2]. There are many sources for the reproduction of Aedes aegypt in the community and in school public areas. In Southern Thailand, the Islamic school or Pondok, a Thai Muslim community school, which promotes an autonomous Islamic culture and life-style, often accommodates students in small huts or separate rooms for 1 - 2 students to live in during school semesters. There are many structures in the school area of the Pondok for students and instructors, a mosque (a place of worship for followers of Islamam) for boy and girl students, and schoolrooms (classroom and building) for the education program. Thus, the Islamic school or Pondok can be viewed as a community onto itself.

The Islamic School, Nakhon Si Thammarat province, Southern, Thailand, has an educational program consisting of traditional Islamic studies. It is a modern Islamic school with a modern secular curriculum up to grade 12 which comprised 100 teachers and 1646 students. There were two areas: a school area with four buildings and another area with 500 Pondoks (or huts), the two areas being separated by a road. Dengue was a critical problem in the school. In the past three years, the morbidity rate of dengue in 2007, 2008, and 2009 were 797, 1036, and 79 respectively per 100,000 of the population which was much higher than the Thai Ministry of Public Health’s disease standard (<20 per 100,000 population). Although there were no mortalities experienced during this time, the morbidity rate indicated that this was a high risk area for a dengue epidemic. Related factors contributing to this were the large number of students, the Pondok’s environment with a garden and two natural canals, two bathroom’s areas with each place having more than 10 big water containers. Moreover, student attitude perceived dengue prevention and control as unimportant and received little attention and lacked concrete actions. Due to all of these mentioned factors, representatives of all stakeholders—teachers, students, community leaders of the area, the local administrative organization, health providers in the area, and the research team discussed possible approaches in solving the dengue problem of the school.

One of the challenges of dealing with the problem of dengue is to change from a centralized controlled health program to a newer epidemiological paradigm involving a community-based program [3,4]. A community-based program is defined as a combination of a bottom-up and top-down approach with the participation of all stakeholders in providing dengue prevention and control by eliminating larval habitats from the domestic environment or a source reduction [5]. Moreover, such a program should be continuous actively linking with the culture and lifestyle of the community [6]. In previous community-based studies of dengue prevention and control, community capacity building was a strategy in achieving sustainability [7]. This approach is not only concerned with the large-scale prevention and control of communicable diseases, but also focuses on individual protection within communities [8] which increases a community’s competence in the health concerns of its members [9-11]. The community capacity building process consists of preparation, assessment, planning, implementation, and reassessment [12-15].

Previously, there had been little effort in dengue prevention and control in this Pondok school. Thus, this study focused on the process of building capacity of students for dengue prevention and control based on applying appropriate aspects of Muslim culture and lifestyle. The objectives were: 1) to build student capacity; and 2) to evaluate the results of student capacity building.

2. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The student capacity building process for solving the problem of dengue in this study assumed a school-based approach which duplicated a community-based approach which consisted of three dimensions: students in school (leaders and non-leaders), a capacity building process, and dengue prevention and control outcome.

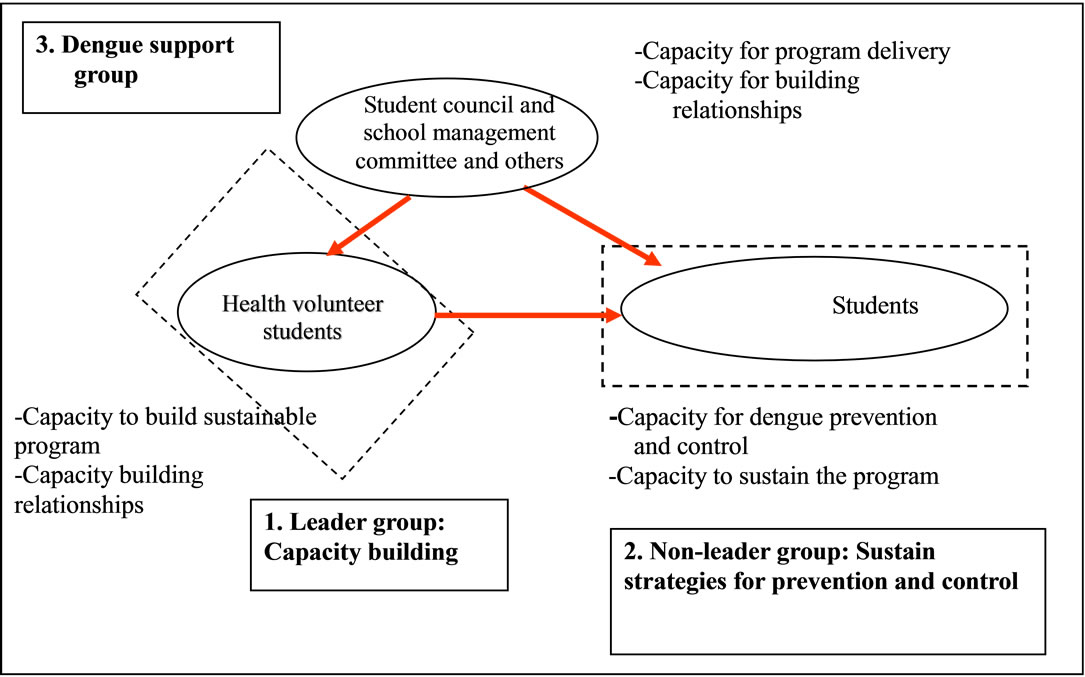

2.1. School-Based Dengue Prevention and Control Group

A school-based approach of dengue prevention and control enables key stakeholders in the school and in the community to actively prevent and control their own dengue problem. The strategies of dengue prevention and control at the school focuses on vector control and transmission of infections to humans, based on the community as the setting, target, agent and resources for dengue activities [6,16]. In this school-based dengue prevention and control study the focus at the Islamic school with dengue centred on three groups for dengue prevention and control: the first group was the leader group with students assuming the role as the “capacity building activities group”. The second group was the non-leader group whose role was to act as the “sustainable prevention and control activities group” after receiving and promoting dengue prevention and control strategies from the students of the leader group. The third group was the dengue support group who were representatives from the student council and school management committee and stakeholders of teachers, community leaders, and the local administrative organization whose function was to promote and support the building capacity process. These groups are depicted in Figure 1.

2.2. Student Capacity Building Process

In this study, dengue community capacity building is defined as a process of building student capacity for dengue prevention and control in a school. The dengue capacity building process consisted of four steps demonstrating an increase in the various domains of community

Figure 1. School-based relationships for building student capacity to overcome.

capacity in a community-based dengue prevention and control program [10,11,16-18]. The process of community capacity building involved the following steps: 1) assessment of community capacity; 2) development of a strategic plan; 3) implementation; and 4) reassessment of the outcome.

2.3. Dengue Prevention and Control Outcomes

Dengue prevention and control comprise activities through which people attempt to control and eliminate larval breeding sources, control adult mosquitoes, apply personal protection, introduce dengue symptom detection and implement outbreak prevention [6]. Such actions are measured by assessing the effective performance in specific community capacity domains, exhibiting dengue prevention and control behaviors as continuing evidence of implementing dengue strategies or activities, and the measurements of 1) Dengue student capacity levels (7 domains); 2) Dengue entomology index; Larval Indices (Breteau Index (BI), House Index (HI), and Container Index (CI); and 3) Dengue epidemiology index; morbidity rate and mortality rate [6,19-21].

3. MATERRIALS AND METHODS

Participatory Action Research was applicable in this study in searching for an appropriate dengue prevention and control pattern within an Islamic school. The study was received and forwarded to the International Review Board (IRB), the Ethical Review Committee for Research Subjects, the Health Science Group, Walailak University, Thailand.

3.1. Study Area and Participants

The study took place between April, 2010 and March, 2011, in an Islamic school, Meung District, Southern Thailand.

3.2. Methods

There were three phases in the student capacity building process: 1) the preparatory phase; 2) the process of building student capacity phase; and 3) evaluation of the results of the student capacity building.

3.2.1. The Preparation Phase

The research team discussed with the school committee and other stakeholders at a meeting about their dengue problems and solutions. The school had a high dengue morbidity rate as high larval indices indicated a high risk of dengue transmission based on WHO guidelines [22]. There were three groups such as: 1) the leader group consisted of volunteer students involved with the prevention and control of dengue active activities and participated actively in conducting and collecting data. The members of the student leader group were well trained by the research team for process conduction, data collection and were knowledgeable in the study; 2) the non leader group comprised general students whose role was to act as the “sustainable prevention and control activities group” after receiving and promoting dengue prevention and control strategies from the students of the leader group. They were representatives of various classrooms or chosen from the Pondoks through random sampling and 3) the support group consisted of a health worker representative from a primary health care station who was involved with providing dengue solutions in the school and communities, local administrative officers, representatives of student council committee, teachers and the researcher team. The role of this group was to support and facilitate activities for building student capacity, such as meeting with and training the leader group to increase their knowledge of dengue.

The student leader group was amenable to attempting to implement an approach to sustainable dengue prevention and control. The student leader group and other students in the school were empowered and encouraged by the research team.

3.2.2. Building Student Capacity Phase

This phase had four steps; 1) assessment; 2) developing strategies and planning; 3) implemen-tation; and 4) re-assessment.

1) The assessment step

The assessment step consisted of an assessment of the situation and of the community capacity level. For the situational assessment, the researcher used qualitative methods such as leader group discussions and environmental surveys. This step was selected in order to better understand the diversity of community dynamics within the overall qualitative approach [23]. The student capacity level was assessed by the leader group which was trained in data collection methods. The assessment consisted of: a) leaders group discussions, All volunteer students met at least twice per month to assess, plan, implement and reassess; b) entomological survey in 308 Pondoks or rooms and public areas in the school; c) epidemiological monitoring, morbidity and mortality rates were collected from primary health centers. The researcher provided the objectives of the study, obtained informed consent of the participants, discussed the focus group process, and obtained permission to audio record the sessions. To foster a flexible climate for discussion, the conversations were held in the local language, and lasted between ninety to 120 minutes.

2) Developing the strategic plan step

This step followed the preparation and assessment steps. The researcher and the leader group discussed techniques and methods of analyzing the problem of dengue to find solutions for the school over the next six month period. The conceptual framework of the plan focused on building student capacity for sustainable dengue prevention and control suggesting a school-based model followed by an assessment of outcomes. The non-leader group’s capabilities in student capacity were assessed in 7 domains such as a) the elimination of larval sources in school and at home; b) applying methods for prevention and control; c) survey and use of larval indices; d) communicating dengue information; e) dengue prevention and control at students’ homes; f) assessment and basic care of dengue; and g) participation in dengue prevention activities.

3) Implementation step

The basic strategies for dengue prevention and control were collective participation and engagement in leader and non-leader groups. The study activities by the students, both within the built abilities through training, operational meetings, group discussions and consensus, promotional campaigns, and local innovation of each community. The large meeting of all the student leaders was participatory and created several plans for dengue solutions from the beginning and until the end of the intervention.

4) Re-assessment step

The main activities in the re-assessment step centred on assessing the outcomes as a sustainable solution to the dengue problem—the same steps as the assessment, evaluation and comparison before and after capacity building. The meetings were structured as a series of workshops attended by the researcher, the leader group and the dengue support team who were involved in dengue prevention and control in the school with the central focus being an appropriate model for solving the problem of dengue.

3.2.3. The Results Evaluation Phase

The leader group and the support group presented the process and outcomes of the study for all students in school. The model of student capacity building process and the outcomes would be adopted as the routine activeties for dengue prevention and control in an Islamic school.

4. MEASUREMENT OF STUDENT CAPACITY

The results of student capacity building were measured both pre-post intervention, by collecting quantitative data methods such as the self-reporting in the seven domains, larval indices surveys, morbidity rate, and mortality rate. The format consisted of four parts: Part I: General characteristics, Part II: Student capacity in dealing with dengue, Part III: Household environment observation form with open ended questions, and Part IV: Larval indices survey form, consisting of the following indices: the House Index (HI), the Breteau Index (BI), and the Container Index (CI), which were calculated to indicate the density of dengue occurrence.

4.1. Student Capacity Level in Dealing with Dengue

The dengue capacity questionnaire form was developed and tested by the researcher. Student capacity for dengue prevention and control was defined as the ability of a student to undertake activities for the prevention and control dengue in 7 domains (36 items): 1) elimination of larval sources in the school and home (6 items); 2) undertake methods for the prevention and control of dengue (4 items), 3) survey and use larval indices (4 items); 4) communicate dengue information to others (6 items): 5) dengue prevention and control at the student’s home (5 items); 6) assessment and basic care of dengue (5 items), and 7) participation of dengue prevention activities (6 items). This dengue capacity questionnaire for the nonleader group comprising 36 items over seven domains, produced the best fit regarding content validity (CVI = 0.81), and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.97).

4.1.1. Participants and Sample Size of Student Capacity Level

The responsible parties for dengue prevention and control intervention in the communities were both the non-leaders as well as the leaders [6,7,24]. The nonleader group was considered to be the group with the ability to achieve sustainable dengue prevention and control activities. They were representatives of the various classrooms or pondoks in the school selected by the dengue leader group.

4.1.2. Data Collection

The researcher and the leader group of student, the members of which were well trained in data collection, introduced themselves and presented the objectives of the study to the community council representatives. They then met a health worker for assistance in collecting data and making the objectives of the study. Next, they obtained consent and cooperation from participants at the first session and began collecting data.

4.2. Entomological Survey

Standard larval index surveys [25] as epidemiological indicators of dengue transmission should be viewed with caution. The three traditional larval indices are the House Index (HI—the percentage of houses infested with larvae and/or pupae; the Container Index (CI)—the percentage of water-holding containers infested with larvae and/ or pupae; and the Breteau Index (BI)—the number of positive containers per 100 houses inspected. Additionally, these were compared before and after building capacity for dengue problem solving [6,26]. Sample size in an entomological survey usually involves a large community of more than 300 households with a sample size of approximately 10%, or at least 100 households [6]. In this study, the water containers were taken from more than 100 pondoks by the leader group which collected data for the larval indices survey. The research team then analyzed and reported this to the student leader team for further planning and discussion.

4.3. Epidemiological Surveillance Monitoring

Dengue is a complex problem because it involves entomology, epidemiology, and socio-ecological components. Therefore, secondary data collection for communities involved rates of dengue incidence. Dengue statistics for the current and previous three years, details of dengue interventions, implementation efforts in the communities, and the results of dengue programs were all collected from health centers and local administrative organizations.

5. DATA ANALYSIS

5.1. Qualitative Data

The dengue situation and community capacity building process were all use conclusion method.

5.2. Student Capacity Level

Personal information concerning the participants of the non-leaders, were collated by descriptive statistics, percentage, mean, and standard deviation.

The different mean levels of student capacity used the Independent T-test to compare the group before and after building capacity, (P < 0.05). Because of the study conducted one year, then the partial students of before-post intervention test finished the education program and changed the education level.

5.3. Entomological Indicators

As for entomological indicators and data of main breeding sites, this study used only larval classical indices which were analyzed as the House Index (HI)—the percentage of houses infested with larvae and/or pupae, the Container Index (CI)—the percentage of water-holding containers infested with larvae and/or pupae, and the Breteau Index (BI)—the number of positive containers per 100 houses inspected.

5.4. Epidemiological Surveillance

The morbidity and mortality rates of dengue were analyzed based on information from primary health care centers in nearby communities.

6. RESULTS

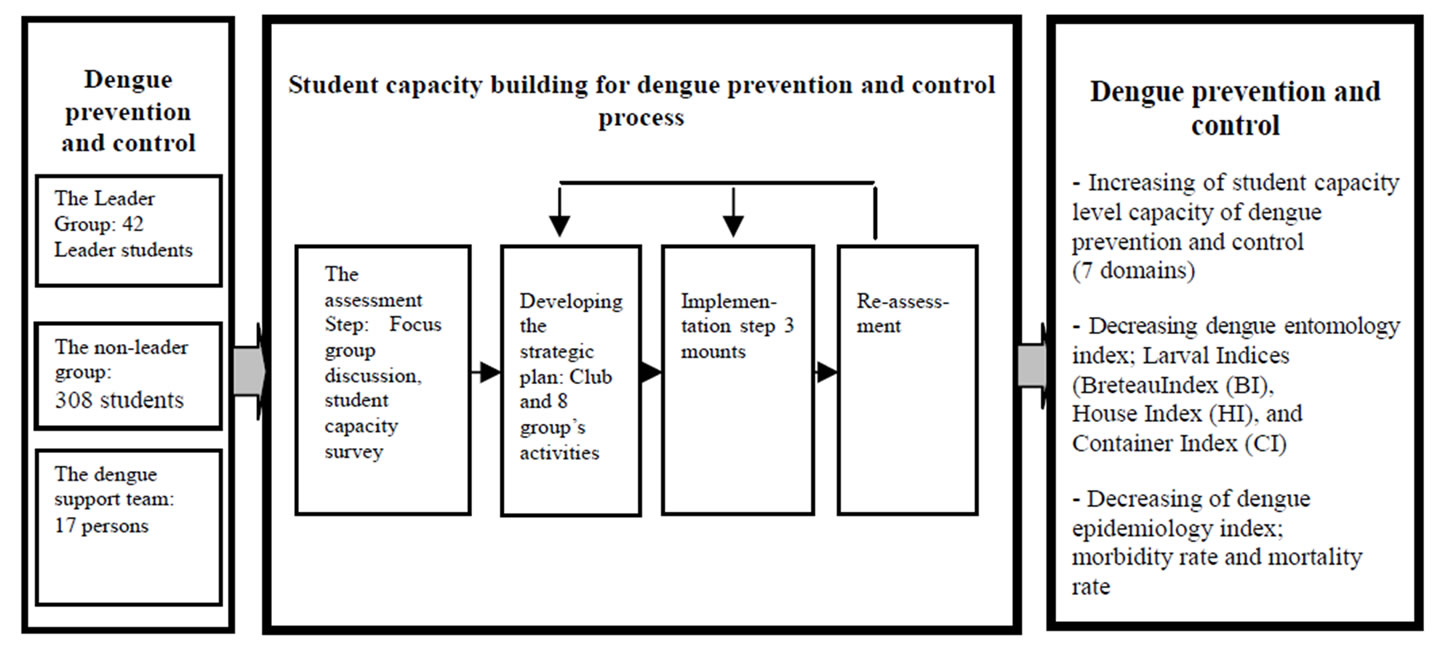

The results of the study focused on process and outcome of community capacity building which devised into two sections: 1) the model of student capacity building process as the results of the building capacity process, and 2) the results of student capacity building consisted of student capacity level, the entomological outcome, and the epidemiological outcome.

6.1. The Model of Student Capacity Building Process

The process of student capacity building followed a conceptual framework of setting up a dengue working group, preparation for dengue prevention and control, and setting up an accountable group as a student club and activities.

The dengue working groups for building capacity consisted of three groups: 1) the student leader group which comprised 48 volunteer students. The members of the student leader group were well trained in the following areas: data collection, knowledge of dengue and data analysis. They were as the assistant of researcher for conducting study; 2) there were 308 non-leader students comprising the “non leader group” who represented rooms or Pondoks which educated and promoted dengue prevention and control strategies adopted by the students of the leader group; 3) the support group comprised 17 persons consisting of a health worker representative from a primary health care station who was involved with providing dengue solutions in the school and communities, local administrative officers, representatives of the student council committee, teachers and the research team.

Preparation for dengue prevention and control. Groups in this study which participated in the dengue prevention and control educational program met regularly. An expert of entomology and a nurse were invited to the meetings. Altogether all three groups met a total for discussion study of once mouth.

A group was set as an accountable group considered as a student club named “Eliminate Ades Aegypti, the culprit of dengue” which immerged from the process of the study. They carried out eight groups of activities: “Dengue or Death”, “Seniors Educating Juniors”, “Reward for Good Answers”, “Dengue Monitoring Team”, “Youth to Expel Mosquitoes”, “Mosquito or Busy”, “Garbage Elimination of Pondok”, and “Essential Doctors”.

1) “Dengue or Death Group” set up the “Citronellas Bank”, and “Fish Bank”. The Citronellas Bank utilized a herbal for expelling mosquitoes. The Fish Bank used a biological method for eliminating larval in water containers.

2) “Seniors Educating Juniors Group” focused on dengue education including type and transmission of dengue, mosquito vector, prevention and control in the community and school. Activities took place once per week.

3) “Reward for Good Answers Group” conducted questions and answers about dengue prevention and control. Good or correct answers were rewarded.

4) “Dengue Monitoring Group” collated the results of all group activities, surveys of the environment, larval indices surveys, and preand post-intervention tests for outcomes.

5) “Youth to Expel Mosquito Group” searched out new or innovative ideas for the prevention and control. The name of their activity was called “Dengue knowledge communication”.

6) “Mosquito or Busy Group” focused on the concept of “taking time for dengue prevention and control”. They role play “Death from Dengue”.

7) “Garbage Elimination of the Pondok Group” was a group formed to apply methods of reduction, reuse and recycling for the environment of Pondok. The representatives of Pondok met to create strategies appropriate for the Pondok context.

8) “Essential Doctors Group” was a group for the basic assessment and self care when sign and symptoms of dengue prevention when discovered and consisted of sponging, drug treatment, and notifying the health teacher in the school and referring the individual to the health provider in the primary care center in the community (see Figure 2).

6.2. The Results of Student Capacity Building Process

The results of the student capacity building process were devised into non-leader student capacity level, the entomological outcome, and the epidemiological outcome.

6.2.1. Non-Leader Student Capacity Level

1) Characteristics (no present table)

The following are the characteristics of the participants of the non-leader group in preand post-intervention. Pre-intervention showed 308 participants, a mean and standard deviation ( (SD)) of age of 15 (1.5) years; an annual family income of 18,324 (23,961) Baht; time staying in school of 2.4 (1.3) years; time of dengue training of 0.4 (0.5) times/person/year. The majority percentage (%) of students were girl (42%), Nakhon Si Thammarat province address (45.5%), couple status of family (93%) member of student club (52%), education level at high school grad 10 (24%), dengue training (47%), and had dengue experience (61%).

(SD)) of age of 15 (1.5) years; an annual family income of 18,324 (23,961) Baht; time staying in school of 2.4 (1.3) years; time of dengue training of 0.4 (0.5) times/person/year. The majority percentage (%) of students were girl (42%), Nakhon Si Thammarat province address (45.5%), couple status of family (93%) member of student club (52%), education level at high school grad 10 (24%), dengue training (47%), and had dengue experience (61%).

Post-intervention showed 308 participants. The mean and standard deviation ( (SD)) were as follows: age, 16 (1.6) years; family income, 26,400 (65,187) baht; time stay in school, 3.5 (1.6) years; time of dengue training, 0.5 (0.4) times/person/year; the major percentage (%) of students were girl (56%); those with a Nakhon Si Thammarat province address (55%); couple status of family (96%), member of student club (52%), education level at high school grad 11 (30%), dengue training (52%), had dengue experience (50%).

(SD)) were as follows: age, 16 (1.6) years; family income, 26,400 (65,187) baht; time stay in school, 3.5 (1.6) years; time of dengue training, 0.5 (0.4) times/person/year; the major percentage (%) of students were girl (56%); those with a Nakhon Si Thammarat province address (55%); couple status of family (96%), member of student club (52%), education level at high school grad 11 (30%), dengue training (52%), had dengue experience (50%).

Figure 2. Model of student capacity building process in an islamic school.

The characteristics of non-leader in preand post intervention, sex, age, education level, family income, dengue training, and dengue experience, were using c2 test showing statistics significant difference (P < 0.05).

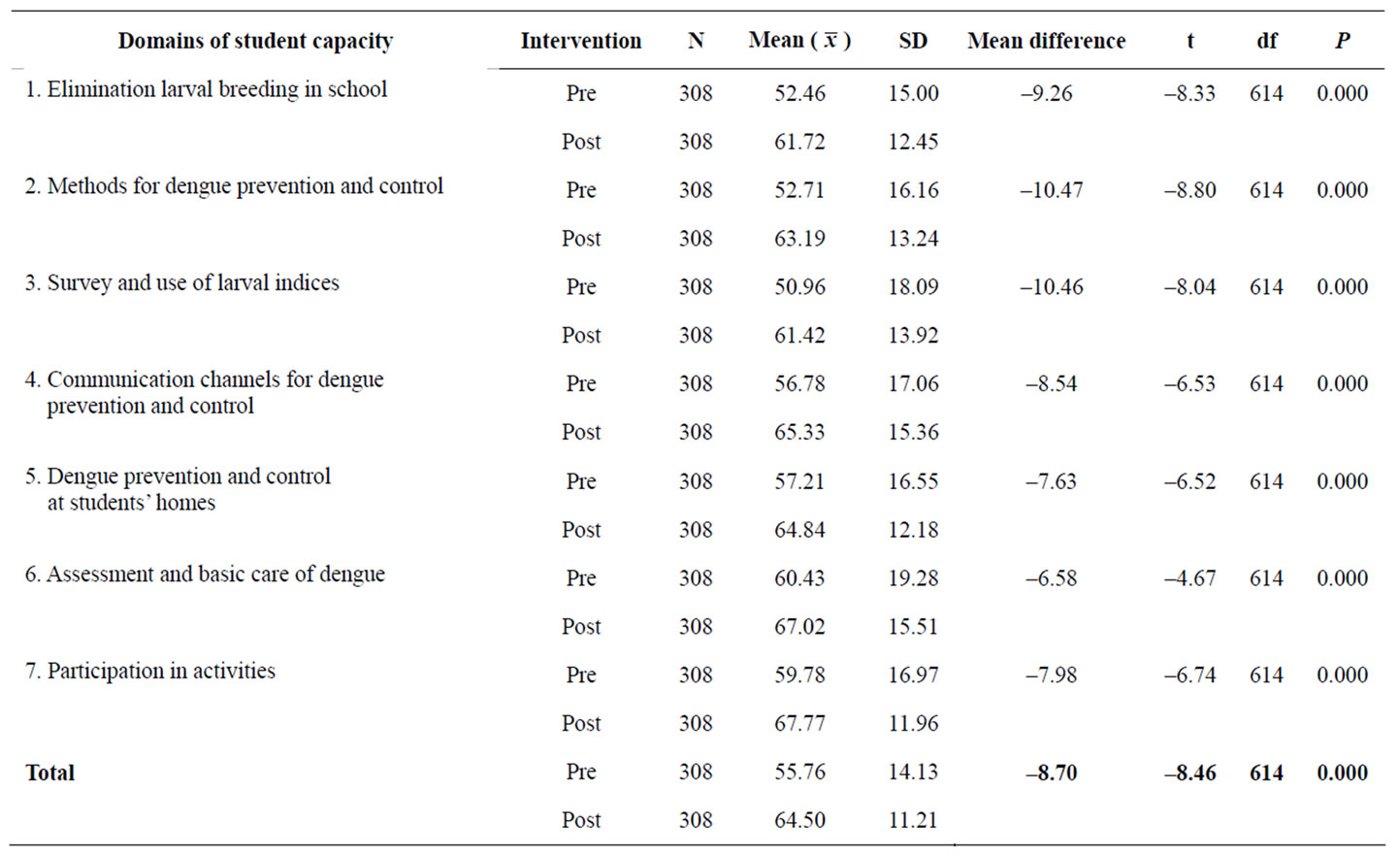

2) Student Capacity Level

Student capacity for dengue prevention and control were defined as the ability of students to undertake activities for the prevention and control of the dengue disease in 7 domains (36 items): 1) elimination of larval sources in school and home (6 items), 2) application of methods for prevention and control (4 items); 3) survey and use larval indices (4 items), 4) Utilization of communication channels for dengue prevention and control (6 items); 5) Dengue prevention and control at students’ homes (5 items); (6) Carry out assessment and basic care of dengue (5 items); and (7) Participation in dengue prevention activities (6 items).

1) Elimination of larval sources in school and in the home consisted of the ability of students to invite other students to eliminate larvae such as closed water containers, changing water every seven days, destroying unused container. The results showed mean and standard deviation ( (SD) of preand post-intervention in this capacity level of 52.46 (15) and 61.72 (12.45) respectively. The domain was compared with the different means in the preand post-intervention stages showing a statistical significance (P < 0.001).

(SD) of preand post-intervention in this capacity level of 52.46 (15) and 61.72 (12.45) respectively. The domain was compared with the different means in the preand post-intervention stages showing a statistical significance (P < 0.001).

2) Application of methods for prevention and control was determined by the ability of the students to encourage other students to use the physical technique of the “Fish Bank” to eliminate larvae and the herbal technique “Citronella Bank” to expel mosquito. The results showed a mean and standard deviation ( (SD) of preand post-intervention in this capacity level of 52.71 (16.16) and 63.19 (13.24) respectively. The domain was compared with the different means in both the preand postintervention stages showing a statistical significance (P < 0.001).

(SD) of preand post-intervention in this capacity level of 52.71 (16.16) and 63.19 (13.24) respectively. The domain was compared with the different means in both the preand postintervention stages showing a statistical significance (P < 0.001).

3) Surveying and using larval indices reflected the ability of students to encourage other students to survey breeding sources of mosquitoes, explaining the results of the larval indices, demonstrating larval survey techniques, notifying the health teacher of lar val indices, and using larval indices for dengue prevention and control planning. The results showed a mean and standard deviation ( (SD) of preand post-intervention in this capacity of 50.96 (18.09) and 61.42 (13.92) respectively. The domain was compared with the different of means in preand post-intervention showing statistical significance (P < 0.001).

(SD) of preand post-intervention in this capacity of 50.96 (18.09) and 61.42 (13.92) respectively. The domain was compared with the different of means in preand post-intervention showing statistical significance (P < 0.001).

4) Utilization of communication channels for dengue prevention and control domain was considered the ability of the students to use several channels to communicate dengue prevention and control such as to avoid risk areas, personal prevention of mosquitoes, and notification of the health teacher or primary health provider when a student had dengue symptoms. The results showed a mean and standard deviation ( (SD) of preand postintervention in this capacity of 56.78 (17.06) and 65.33 (15.36) respectively. The domain was compared the different mean in preand post-intervention showing statistical significance (P < 0.001).

(SD) of preand postintervention in this capacity of 56.78 (17.06) and 65.33 (15.36) respectively. The domain was compared the different mean in preand post-intervention showing statistical significance (P < 0.001).

5) Dengue prevention and control at students’ homes demonstrates the ability of the students to monitor other students in activities of dengue prevention and control at the home such as destroying breeding sites every seven days, promoting the elimination of breeding sites within 100 meters of households.

6) Assessment and basic care of dengue was evaluated by the ability of the students to assess the signs and symptoms of dengue fever, to explain to other students the severity of dengue, to administer the tourniquet test to diagnose the dengue disease, apply sponges to release hyperthermia (high body temperature), and to have a basic understanding in the use of drugs in treating dengue fever. The results showed a mean and standard deviation ( (SD) between the preand post-intervention stages in this capacity at a level of 60.43 (19.28) and 67.02 (15.51) respectively. The domain was compared the different mean in the preand post-intervention stages showing statistic significance (P < 0.001).

(SD) between the preand post-intervention stages in this capacity at a level of 60.43 (19.28) and 67.02 (15.51) respectively. The domain was compared the different mean in the preand post-intervention stages showing statistic significance (P < 0.001).

7) Participation in activities was measured by the ability of the students to participate in dengue prevention and control, and to encourage other students to joint in dengue prevention activities such as participating with the health teacher, the primary health care provider, people surrounding the school, and activities of “Eliminate Ades Aegypti, the culprit of dengue”. The results showed a mean and standard deviation ( (SD) of preand postintervention in this capacity at a level of 55.76 (14.13) and 64.50 (11.21) respectively. The domain compared the different means in preand post-interventions showing a statistical significance (P < 0.001) (see Table 1).

(SD) of preand postintervention in this capacity at a level of 55.76 (14.13) and 64.50 (11.21) respectively. The domain compared the different means in preand post-interventions showing a statistical significance (P < 0.001) (see Table 1).

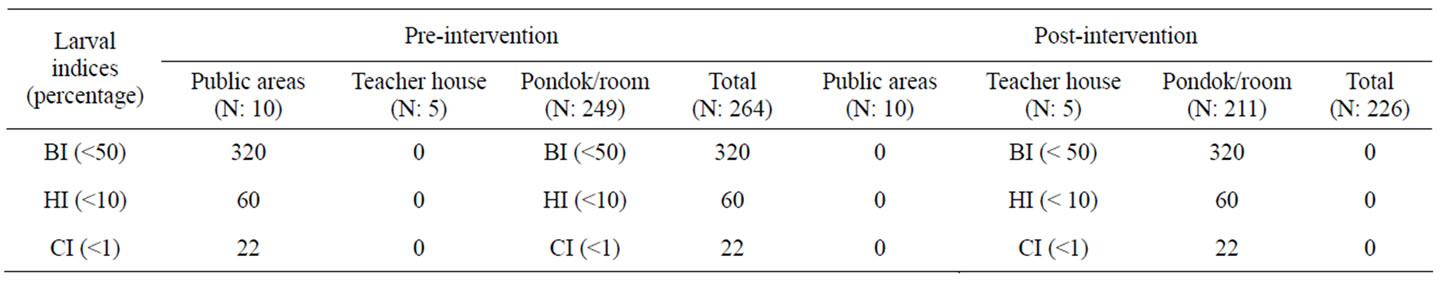

6.2.2 Entomological Outcome

1) Larval index preand post-intervention

Larval surveys were conducted to determine types of containers and larval indices in three areas: public areas (man’s and woman’s bathrooms, classroom building, mosque, and football field), teachers’ houses, and Pondok/student residential rooms. Inspections were conducted both prior to and after the intervention with 10 public areas, and 5 teachers’ houses both before and after, and 249 Pondok/rooms before and 211 after the intervenetion. In total, 249 and 226 places were inspected before and after respectively. The BI, HI, and CI in the preand post-intervention of public areas were 320, 60, and 22 prior to the intervention, which then decreased to 170, 50, and 24 respectively in the post-intervention stage. Comparing the BI, HI, and CI of the preand post-intervention condition of the Pondok/rooms, levels were 224, 45, and, 27 and 147, 42, and 19 respectively. The teacher area did not show larval indices in either the preor postintervention stages. In total, the BI, HI, and CI during pre-intervention were 224, 45, and 67, and decreased to 137, 39, and 19 respectively in the post-intervention phase (see Table 2).

2) Types of containers inspected

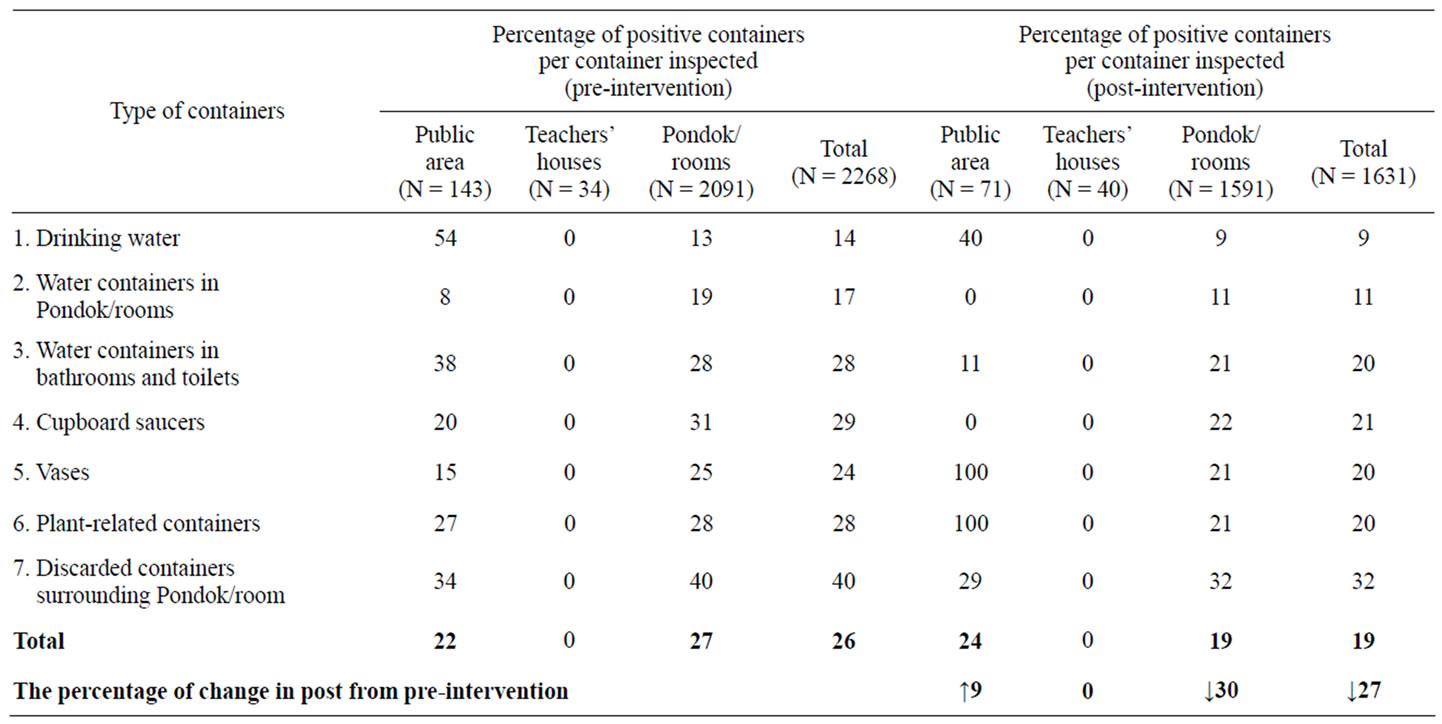

In conducting larval surveys, a total of seven types of water containers were observed during the pre-intervention (April, 2010) and post-intervention (March, 2011) periods with 2628 and 1631 containers inspected respectively. Percentage of positive containers inspected during the pre-intervention phase in the three areas (public areas, teachers’ houses, Pondok/student residential rooms) showed a very high percentage of positive containers being discarded surrounding the school, namely, 34%, 0%; and 40%, and 29%; 0% and 32% in the post-intervention phase respectively. The percentage of positive containers

Table 1. Comparison of student capacity levels between preand post-intervention (P < 0.001).

Table 2. Percentage of larval indices of areas in school during preand post-intervention.

during the post-intervention phase decreased from preintervention for five types of water containers, but for “vases” and “plant-related containers” increased from the pre-intervention phase in public areas by 100 percent. In conclusion, however, the percentage of change in positive containers inspected in the post-intervention decreased in Pondok/Student rooms (30%), total (27%) and increased in public areas (9%) (see Table 3).

6.2.3. Epidemiological Outcome

The epidemiological index is the outcome of intervenetion of student in school. In this study, the index consisted of the morbidity and mortality rates. The comparison of morbidity rate of dengue pre-intervention in 2007, 2008, and 2009 were 797, 1036, and 79 per 100,000 population and post-intervention (during the study from April 2010 to March 2011) unpresetting of morbidity rate of primary health care center and health teacher.

7. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The results of the study showed participation of all three groups—the leader group, the non-leader group, and the support group—for finding a model of dengue prevention and control appropriate for this Islamic school. This resulted in a new model for the school with schoolbased strategies associated with the study of community and school-based health education for dengue control in rural Cambodia: A Process Evaluation [27]. This model of a student capacity building process utilized a student club named “Eliminate Ades Aegypti, the culprit of dengue” and carried out eight groups of activties as “Dengue or Death”, “Seniors educating juniors”, “Reward for good answers”, “Dengue monitoring team”, “Youth to expel mosquitoes”, “Mosquito or busy”, “Garbage elimination of Pondok”, and “Essential doctors”. Their activities needed the support of the school committee which monitored the continual process: assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation associated with the conceptual sustainable dengue prevention and control [10,11, 14,17,28,29].

The student capacity level of the 308 participants increased time devoted towards dengue education after intervention increased from 47 to 58 percent in all the seven related domains and statistics of total student capacity increased significantly. The increased scores of student capacity resulted from participation in the eight groups of activities of the club, “Eliminate Ades Aegypti, the culprit of dengue” during the 12 months of the study.

The 224 from 264 Pondok/rooms were survey for larva because partial Pondoks/rooms did not have water containers. However, the sample size of representatives from the 1,646 students, and 500 Pondok/rooms can be compared to the standard used for a larval survey in a large community [6]. Larval indices during pre-intervention (BI: 244, HI: 44, and CI: 26) decreased after students had undertaken activities (BI: 147, HI: 42, and CI: 19). Although the level of index obviously decreased, the larval value was much higher than the standard criteria of WHO [26] and applied in Thai Ministry of Public Health Index (BI < 50, HI < 10 and CI < 1). Because the value indices were related to the estimated mosquito density of 600,000 - 900,000 females/1km2. [26], especially public areas were high risk breeding sites and received little attention from the students.

The morbidity and mortality rate during the time of the study showed non presentation of dengue illness. The primary health care center had been continuously monitoring these outcomes which had decreased from three years previously.

Although there was an increase in student capacity, a decrease in the larval indices ratio, and the absence of a framework of this study and the concepts of community capacity building for dengue epidemiology index, the high risk for dengue epidemic might still be found in this school because of the ratio of larval indices being higher than the standard index. Consequently, the serious participation of students, school, and communities around the school area is need for building greater student capacity for dengue prevention and control.

8. LIMITATIONS

One limitation of the study is that it was conducted only one year. A longer period is needed for assessment and to determine continuing results. Nevertheless, the study assessed the outcomes of intervention at preand post-intervention stages of the study, and should also include an assessment during the interim of the study to determine the achievements of student activities.

Table 3. Type of containers inspected, positive containers with larva and percentage before and after intervention.

9. CONFLECT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author(s) declare that there were no competing interests in caring out this study.

10. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grateful acknowledgements are to students, teachers, and representatives of the communities surrounding school and to the research team. The author(s) would like to thank Walailak University, Thailand for funding the project and the School of Nursing for the support by providing available time. Special thanks to Victor Greenspoon who has edited the manuscript.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Gubler, D.J. (2002) Epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health, social and economic problem in the 21st century. Trends in Microbiology, 10, 100-103. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02288-0

- Promprou, S., Jaroensutasinee, M. and Jaroensutasinee, K. (2005) Climatic factors affecting dengue heamorrhagic fever incidence in Southern Thailand. Dengue Bulletin, 29, 41-48.

- Lcung, M.W., Yen, I.H. and Minkler, M. (2004) Community-based participatory research: A promising approach for increasing epidemiology’s relevance in the 21st century. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 499-506.

- Guha-Sapir, D. and Schimmer, B. (2005) Dengue fever: New paradigms for a changing epidemiology. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology, 2, 1-10. doi:10.1186/1742-7622-2-1

- Gubler, D.J. and Clark, G.G. (1996) Community involvement in the control of Aedes aegypti. Acta Tropica, 61, 169-179. doi:10.1016/0001-706X(95)00103-L

- World Health Organization (1999) Prevention and control of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever: Comprehensive guidelines. WHO Regional Publication, SEARO No. 29, New Delhi.

- Toledo, M.E., Vanlerberghe, V., Perez, D., Lefevre, P., Ceballos, E., Bandera, D., et al. (2007) Achieving sustainability of community-based dengue control in Santiago de Cuba. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 976-988. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.033

- Norton, B.L., McKeroy, K.R., Burdine, J.N., Felix, M.R.J. and Dorsey, A.M. (2002) Community capacity: Concept, theory, and methods. Jossey-Bass Wiley, San Francisco.

- Laverack, G. (2001) An identification and interpretation of the organizational aspects of community empowerment. Community Development Journal, 36, 134-145. doi:10.1093/cdj/36.2.134

- Labonte, R. and Laverack, G. (2001) Capacity building in health promotion, part 2; whose use? And with what measurement? Critical Public Health, 11, 129-139. doi:10.1080/09581590110039847

- Laverack, G. (2003) Building capable communities: Experiences in a rural Fijian context. Health Promotion International, 18, 99-106. doi:10.1093/heapro/18.2.99

- Suwanbamrung, C. (2010) Community capacity for sustainable community-based dengue prevention and control: Domain, assessment tool and capacity building model. Asia Pacific Journal Tropical Medicine, 3, 499-504. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60121-6

- Suwanbamrung, C., Dumpan, A., Thammapalo, S., Sumrongtong, R. and Phedkeang. P. (2011) A model of community capacity building for sustainable dengue problem solution in Southern Thailand. Health, 3, 584-601. doi:10.4236/health.2011.39100

- Suwanbamrung, C., Nukan, N., Sripon, S., Somrongthong, R. and Singchagchai, P. (2010) Community capacity for sustainable community-based dengue prevention and control: Study of a sub-district in Southern Thailand. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 3, 1-5. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60012-0

- Suwanbamrung, C., Somrongthong, R., Sinchagchai, P. and Srigernyaun, L. (2009) Community capacity domains of dengue prevention and control. Asia Pacific Journal Tropical Medicine, 2, 50-57.

- Nguyen, M.-N., Gauvin, L., Martineau, I. and Grignon, R. (2005) Sustainability of the impact a public health intervention: Lessons learned from the Laval walking clubs experience. Health Promotion Practice, 6, 44-52. doi:10.1177/1524839903260144

- Bopp, M. and Bopp, J. (2002) Welcome to de swamp: Why assessing community capacity is fundamental to transformational work. In: Smith, N., Littlejohns, L.B. and Roy, D. Eds., Measurement community capacity: State the field review and recommendations for future research, community-level indicators: Building community capacity for health conference, David Thromp-Son Health Region, Red Deer.

- Laverack, G. and Wallerstein, N. (2001) Measuring community empowerment: A fresh look at organizational domains. Health Promotion International, 16, 179-85. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.179

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (2003) 44th directing council, 55th session of the regional committee. Washington DC, 22-26 September 2003. http://www.paho.org/english/gov/cd/cd44-28-e.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2003) Epidemic/epizootic west Nile virus in the United States: Guidelines for surveillance, prevention, and control. CDC, Colorado. http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/00Ref/MiscellaneousContents/d67.htm

- Spark, R. (2003) Dengue fever management plan for North Queensland 2000-2005. Queensland Government, Queensland.

- Wongkoon, S., Jaroensutasinee, M. and Jaroensutasinee, K. (2005) Larval infestation of Ades aegypti and Ades albopictus in Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand. Dengue Bulletin, 29, 169-175.

- Flick, U., Lardorff, Ev. and Steinke, I. (2004) A companyion to qualitative research. SAGE Publications, London.

- Gibbon, M., Labonte, R. and Laverack, G. (2002) Evaluation community capacity. Health and Social Care in the Community, 10, 485-491. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00388.x

- Focks, D.A. (2004) A review of entomological sampling methods and indicates for dengue vectors WHO, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (1933) Monograph on dengue/ dengue haemorrhagic fever. Regional Office for South-East Asia, New Delhi.

- Khun, S. and Manderson, L. (2007) Community and school-based health education for dengue control in rural Cambodia: A process evaluation. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 1, 1-10. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000143

- Labonte, R. and Laverack, G. (2001) Capacity building in health promotion, part 1; for who? And for who purpose? Critical Public Health, 11, 111-127. doi:10.1080/09581590110039838

- Suwanbamrung C. (2010) Community capacity for sustainable community-based dengue prevention and control: Domain, assessment tool, capacity building model. Asia Pacific Journal Tropical Medicine, 3, 499-504. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60121-6