Sociology Mind

Vol.4 No.2(2014), Article ID:44642,15 pages DOI:10.4236/sm.2014.42014

Open Organization Networks: Combining Closure and Openness in the Social World of an European Buddhist Monastery

José A. Rodríguez Díaz, Liliana Arroyo Moliner

Department of Sociology and Organizational Analysis, Faculty of Economy and Business, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Email: jarodriguez@ub.edu, liliana.arroyo@ub.edu

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 December 2013; revised 6 February 2014; accepted 22 February 2014

ABSTRACT

We present a social network study of a southern European Buddhist monastery that aimed at taking Buddhism from the monastery to society. It is an interesting experiment of fusion between Buddhism and the west and of its adaptation to modern times and new lands. We adopt the relational perspective to understand its adaptation process, the organizational forms used, its dynamics, its life, and its relations with the surrounding society. Our study shows that the use of social relations has been essential for the success of the organization and its project. The social system they created is rich, complex, and has a great capacity for offering services and taking action. It is an interesting case of relation between meaning and form. The meaning, the project, generates a specific organizational form (networks) to guarantee the closure necessary for certain functions and the necessary openness for its project towards society.

Keywords:Social Networks; Buddhism; Modernization; Open Organization

1. Introduction

This paper presents results of a sociological study of a Buddhist community created with the goal of taking Buddhism from the monastery to society.

Broadly, it is an example of the processes of fusion between Buddhism and the west, or the processes of its adaptation to modern times and new lands. It is an original experience of adaptation process of Buddhism and its organizational format in its recent arrival to a southern European Catholic country (Arroyo, 2013).

We wonder how a Buddhist organization, alien to the dominant Catholic religious and cultural life of the country, could survive and strive becoming a reference of a new modern form of Buddhism in the west. We are intrigued by what model of Buddhism and what organizational form make it possible.

We adopt the Social Network Analysis (SNA) approach and relational perspective to try to better understand its adaptation process, in this specific case to try to cast some light over the organizational forms used, dynamics, life and relations with the surrounding society.

2. From the Monastery to Society1

It all began with Chill Out. At the end of 2005, the Sakya Tashi Ling Buddhist Monk Community2 released the Buddhist Monks CD3 whose songs are Buddhist mantras wrapped in Chill Out, or as it was defined by the press at the time, “mantras to a pop rhythm”. In three weeks it had become a Gold Record (selling more than 40,000 copies); rapidly reaching number one on sales lists and on iTunes, and in three months had already reached Platinum (with 80,000 copies sold). In few months it sold more than 150,000 copies in Spain, and its total number of world sales was much higher.

Buddhism in Spain is a relatively new phenomenon. Its presence starts being noticeable during the seventies (of the last XX century)4, more than a decade later than in other European countries or in the United States of America. But unlike the American and Anglo-Saxon experiences, the expansion of Buddhism in Spain is not related to ethnic immigrant populations and flows. It is essentially the result of the new value system that makes that most of the Buddhist people are locals who were socialized in another religion and have voluntarily chosen to learn, believe and practice Buddhism (Philips & Aarons, 2007: pp. 329-330). In 2007, Buddhism is officially recognized by the state as a religious denomination with presence in the country and therefore granting its centers and practitioners the religious status5.

The Buddhist Monks CD is a novel product which differs from many CDs of mantras sung by monks in the traditional way or New Age music CDs that incorporate complete or partial mantras. These latter cultural products are primarily geared toward a limited public, whether it be practicing Buddhists, New Age followers, or spiritual seekers (Tweed, 1998). Buddhist Monks is a product which takes the mantras from the Monastery and brings them to a new public with no prior interest in religion, Buddhism, or spirituality. It is a product especially addressed to youth but also appropriate for a wider public. In addition to making Buddhism very visible, it offers a new vision of Buddhism, of the role of monks and of the very concept of the monastery. It is an indicator of a different type of project and organization representing the new Buddhism (Baumann, 1997b) resulting from adaptation to modern contexts (Lenoir, 1999; Baumann, 1994, 1997a).

The format as well as the transmission method used exemplarizes a new model of Buddhism that goes beyond the so-called westernization or occidental adaptation (Batchelor, 1994; Coleman, 2001; Prebish & Baumann, 2002). They shape a form of open Buddhism which somehow differs from the traditional Buddhism in its methods of transmission and dissemination as well as in its organizational forms and even in its prioritization of its content, presentation, and role in society (López, 2000; McMahan, 2008). The use of market and consumer products to introduce their values in society results, in return, in the modernization of the message and product. This adaptation of the product facilitates the reach of a wider range of Buddhist followers and, essentially, of non-Buddhists. They become messages intended to generate well-being in the general population rather than to make Buddhist converts6. In general, this approach results in greater social acceptance from a population that is just starting to become acquainted with Buddhism and its low-demanding practices. Is an example of the diversification taking place in the religious space in the last decades (Chaves & Cann, 1992; Einstein, 2008; Wuthnow & Cadge, 2004). As expected, these changes create reticence and tensions in more traditional and orthodox Buddhist groups and sectors trying to control the definition of the Buddhist space.

The model proposed and practiced by Sakya Tashi Ling (from now on STL) is also the result of the leading role played by local westerners7 in the adaptation and application of Buddhism, and as such it differs from more traditional models of organization lead by oriental monks. It fits perfectly the category of “Modern” in its organizational structures and pragmatism, in the configuration of a wide and active spiritual community of the faithful, in its link with and insertion in society and in its social role (McMahan, 2008; Shark, 1995).

Looking at Success

What originally called our attention to the study of the STL Buddhist monks was their religious, social, and cultural success in a society not open to religious phenomena, which had traditionally been Catholic, whose public practices were lay and where religion had been relegated to private practice (Díaz Salazar, 2006; Díez de Velasco, 2010). That led us to study the organizational forms used in their Project “Buddhism for Society” and specifically from the perspective of social networks8. Social networks analysis offers us a novel and appropriate way to understand these new organizational structures and their dynamics (Laumann & Pappi, 1976; Newman, 2010; Scott, 1991; Wasserman & Faust, 1994; Wellman, 1999).

STL is a Tibetan Buddhist Community belonging to the Sakya lineage and the Ngagpa tradition9. At the time of the field work (2007-2010) the ordained community was composed by thirty-five people (including two Lamas acting as Abbott and Prior) and more than two hundred active lay members regularly involved in the life of the monasteries.

Sakya Tashi Ling has two working monasteries in Spain, and one more is being finished in Peru. The community also has two Dharma houses in Spain The main Monastery, created in 1996 transforming an old mansion and estate at top of the Garraf Natural Park near Barcelona, is the headquarters from where they run their project of Buddhism for Society.

STL is not a traditional closed an inward looking type of monastery (Nietupski, 1999) but rather an outward looking provider of Buddhist services aimed at reaching society at large10. At the organizational level, taking Buddhism outward requires non-hierarchical organizational systems, in the form of networks, which transcend the dyadic and often highly centralized master-disciple relation. It seems a clear example of the neo-institutionalism theories stating that all organizations or institutions are embedded in networks of social relations that facilitate their survival and expansion (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991).

Overall, the entire project is built upon social relations and networks. And so, in order to adequately understand its organizational structures and its role in society, and to somehow understand its success, we need to understand its social networks (Barabási, 2003; Buchanan, 2003; Watts, 2003). Relations—and the networks rising from them—yield a new organizational form which transcends the closed master-disciple relation, allow for the creation of a wide spiritual community and facilitate its insertion into society by generating trust and social legitimacy.

3. Data and Methods

The social system analyzed is the complete extended community (the Sangha). To analyse the social system, we turn to relational information that we obtained through a questionnaire administered in December 2007 and January 2008 to all the members of the Sangha: 35 members in the ordained Sangha and 120 members of the spiritual community of followers. They were asked about their relations of collaboration, communication and trust among themselves (ordained and non-ordained Sangha) and with people and institutions outside the Community. The statistical analysis and the representation of the information have been carried out with Ucinet and Netdraw, programs specialized in social networks. Two large groups can be identified within it: the ordained Sangha11, consisting of Lamas, monks, nuns, novices and postulants; and the lay Sangha, which plays a very active and decisive role in the life of the monastery. The unordained part of the Community includes all the faithful following the project. They are involved in the various Dharma study and practice programs and also regularly take part in religious ceremonies (rituals and initiations) and activities (retreats, pilgrimages). It is precisely in these collective spaces of practice (courses, rituals, initiations, etc.) where relations and ties between members of the project are created making up the extended community in a network form.

The application of SNA to the study of an organization can be helpful to uncover, visualize and analyze the relational structure of the organization, its vital structure, its life. It will help to identify how organizational forms based on relations are created and maintained. It will also help identifying social relevant and central positions for the life and dynamics of the organization. We believe SNA well fit to contribute to the understanding of the types of organizational forms used to run a monastery that it is also open (to the public) and that offers services and products oriented towards the entire society outside its walls. It is also a fruitful avenue to see the social life of the institution.

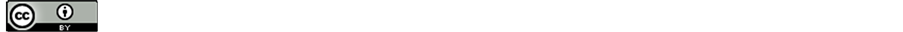

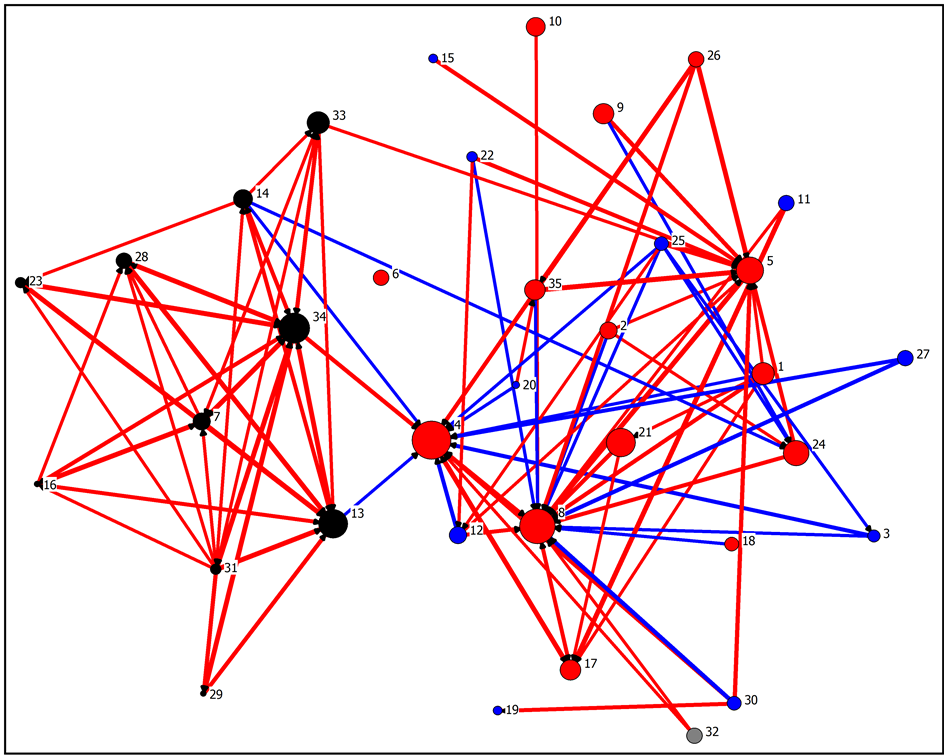

4. The Sangha: The Entire Relational System

The Sangha can be thought and visualized as a network product of the interactions between members of the community, ordained (red, blue, and black nodes) and non-ordained (in fuchsia)12. As can be seen in Figure 113, it is a complex relational system centered on the ordained Sangha (Lamas, monks, nuns, novices, postulants)14 surrounded by the lay community members. And, as expected, the strongest and most cohesive relational structure is that formed by the ordained members. But perhaps the most outstanding feature of this network, in spite of the centralization role played by the ordained, is that is not a pyramidal or hierarchical organizational structure, typical of more traditional organizational models. The organization lives (communicates, collaborates, learns, acts, etc.) as a network, an organizational structure that facilitates non-hierarchical relations among members and empowers them as a community.

The center of the network is occupied by two large substructures linked together which correspond to the two main sites of the Community: the Garraf Monastery with ordained residents (in red) and non-residents (in blue)

Figure 1. Network of the complete Sangha.

and the Castellón Monastery with resident monks and non-monks (in black). The relations among and with members of the Garraf Monastery are the most intense ones and account for a large part of the relational structure (approximately two thirds of all relationships). The network built around the residents of the Castellón Monastery (in black) is smaller and substantially less dense.

Taking as an indicator of relevance and centrality the amount of relations received by any given actor (InDegree here represented by the size of the nodes) in this network there seems to exist a double system of centrality15: global and local. The two Lamas (Actors 4 and 8) are the most central actors globally and they form what we can define as the core of the functional and religious authority structure of the Community. At the local level two additional pair of monks play central roles: nuns 5 and 24 join the Lamas in the functional authority structure of the Garraf Monastery; and monks 13 and 34 assume the local functional authority and are the reference points of the Castellón Monastery.

Even though the lay Sangha does not play a central role (in network terms), it does play a fundamental role in this system. The relationships of the faithful (indicated in the Figure with fuchsia circles) act both as a buffering and protection system of the ordained community and fundamentally as a mechanism of extending the monastic organization to society. We believe this latter feature to be key in the survival and success of the organization and its project.

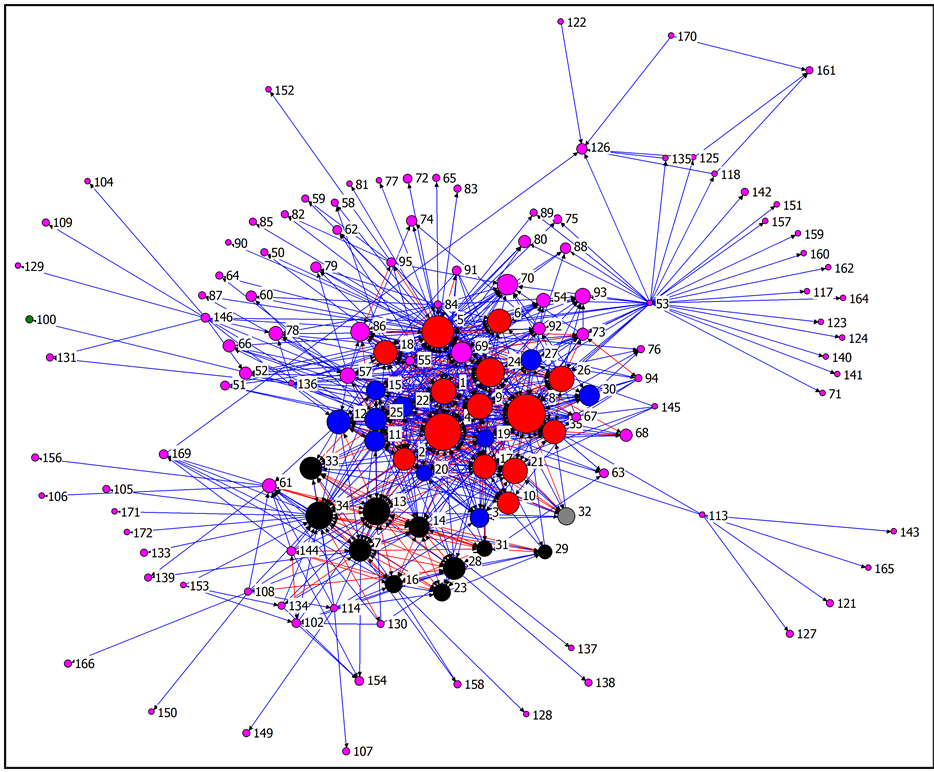

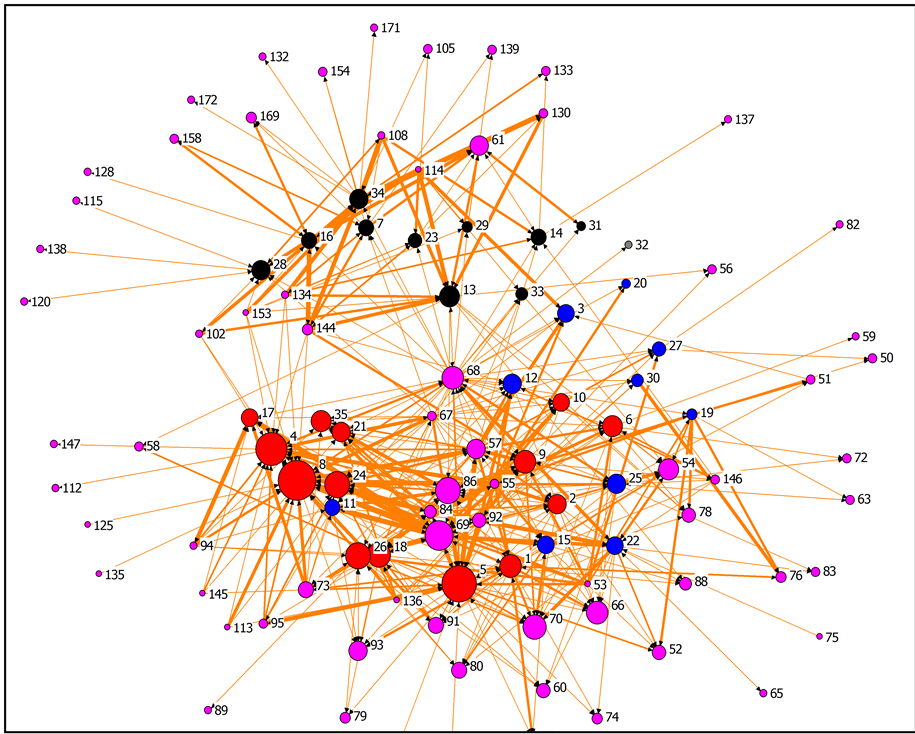

We identify the core (backbone) of an organization by looking into the structure emerging from the most intense relations among its members. The core of the Sakya Tashi Ling relational system presented in Figure 2 is the structure made up by actors who have more than six relations among themselves (Greater Than 6: GT6) of the 15 possible relations forming the system.

This neurological center somehow reproduces the features, albeit in a simplified manner, of the network in its entirety. Monks are definitely dominant in number and in centrality. And reciprocal type relations (in red), fundamentally among the members of the ordained Sangha, outnumber unidirectional relations (lines in blue) and dominate the center of this smaller relational system. Lay members are mostly placed around the center, as a loose net wrapping the denser monk’s structure, with primarily unidirectional relations precisely toward the monks.

As could be expected, the level of reciprocity among the residents living together in the Monasteries is greater than among and with non-residents. These reciprocal relations produce a highly cohesive center in two blocks: Garraf and Castellón. In both cases, the strongest and most reciprocal relations are among the residents, and the weakest relations are, in general, with and among non-residents. The core of the system is glued by those intense and reciprocal relations emerging from residence in the Monasteries.

Additionally, all of this points to a very interesting phenomena: the existence of two different and fundamental roles in the network. Strong relations make up the highly cohesive space in monastic life while weak relations (mostly with and among no residents) extend and unite the complete large Sangha. Relational weakness becomes very important here because it provides access to social spaces and resources far away from the cohesive monastic space (Burt, 1995; Granovetter, 1973). Weak links, among and with non-resident monks and nuns and lay followers, play a key and crucial role in closing the gap between the cohesive center and the world outside of the Monasteries.

Figure 2. Core of the Sangha (strong relations GT6).

In order to better understand this complex system of relations making up STL, we decompose it in its parts: relations among monks and nuns; relations between the ordained and the lay: and relations among the lay members.

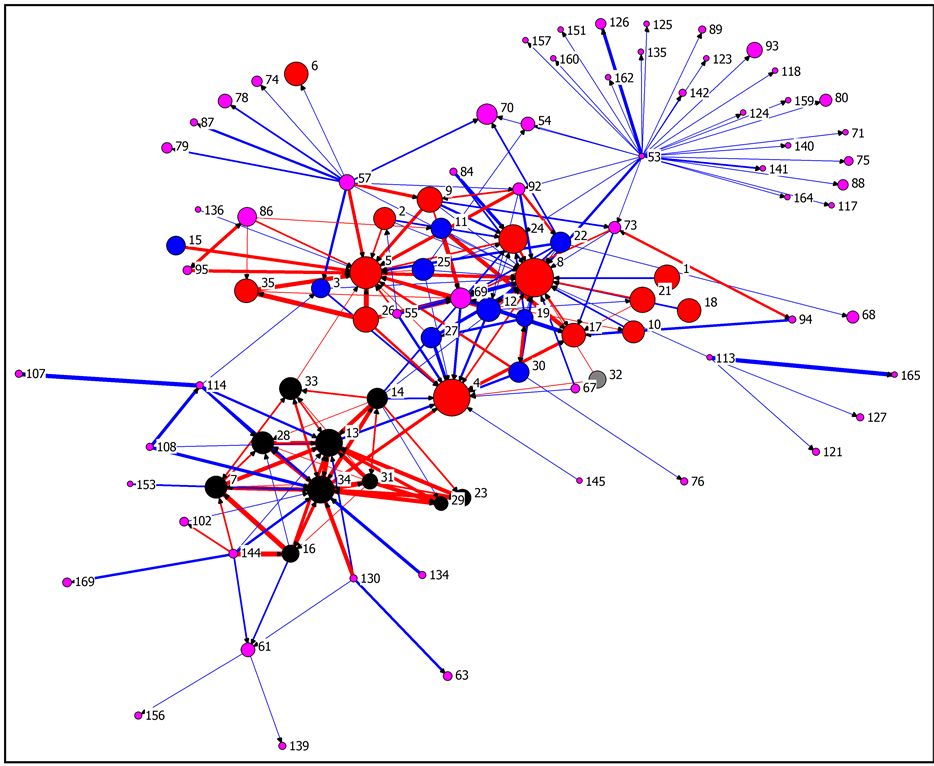

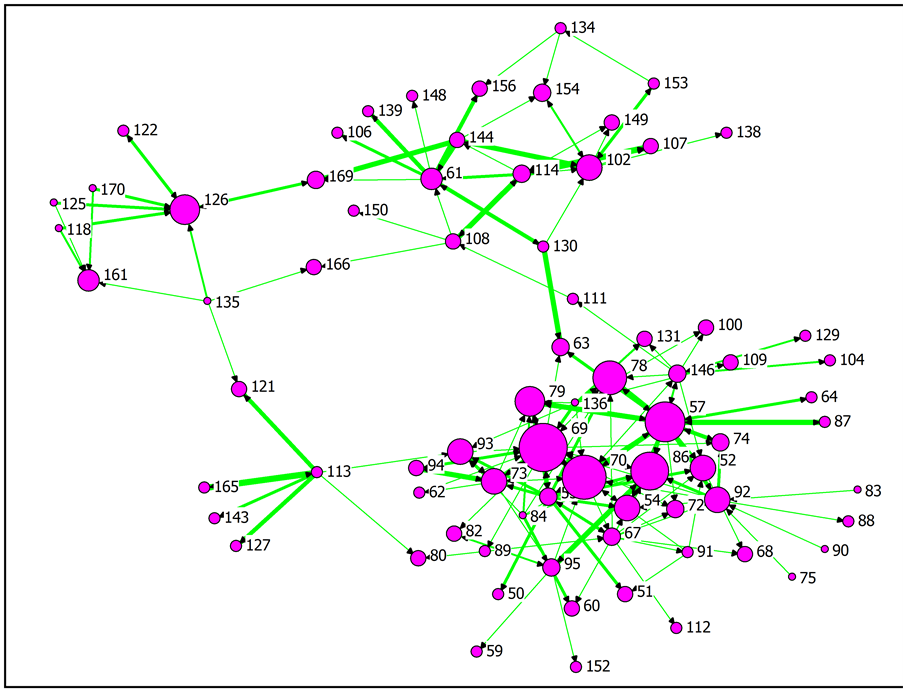

4.1. The Monastic Network

The relations among monks and nuns produce the very dense and compact monastic network shown in Figure 3. Reciprocal relations (shown in red) are clearly dominant and form the bases of the two monastic sub-structures: Castellón on the left and Garraf on the right. The relational space between the two monasteries is weaker and mostly filled by weak unidirectional relations (shown in blue).

At the individual level it is important to point out the centralizing role of the two Lamas. The Abbot (Actor 4) is the centralizer of the entire monastic network and the main connector of the two monasteries and their two social substructures. The centrality of the younger Lama acting as Prior (Actor 8) is fundamentally local. Although he is quite central in the whole network, he is especially so in the Garraf structure. As we saw in the entire Sangha network, together with the Lamas there are four monks and nuns who have a key central role at the local level: Actors 5 and 24 in Garraf and 13 and 34 in Castellón. The non-resident monks and nuns are on the outside edge of the monks’ relational system indicating a lesser centrality in the monastic community life.

The neuralgic center of the monastic network is the structure made up of the most intense relations. Like we did in the case of the entire Sangha, it is formed by actors who have more than 6 relationships of the 15 possible (GT6 in the Figure). Figure 4 shows the superiority of the reciprocal relations over the non-reciprocal ones, that is to say, the superiority of the stronger relations over the weaker. In this neuralgic center, the network breaks

Figure 3. Monastic network.

Figure 4. Center of the monastic network (strong relations GT6).

down into two subnetworks (corresponding to the two monasteries, Garraf and Castellón) internally cohesive and connected by the centralizing and bridging role of the Abbot of the Community (Actor 4). He keeps the monastic system linked.

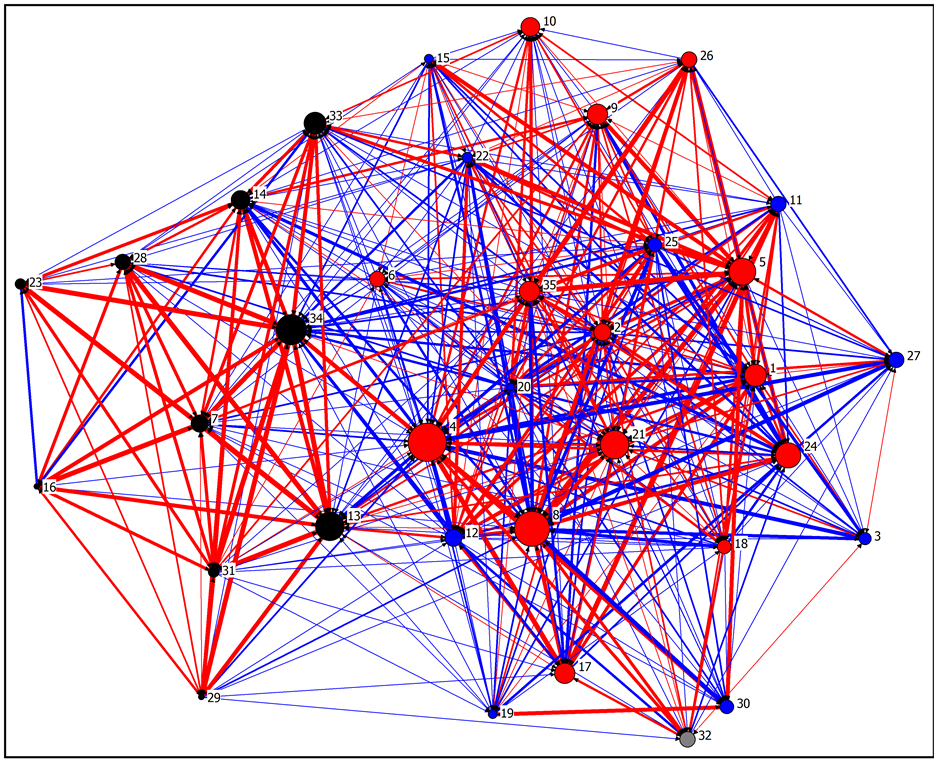

4.2. Creating a Large Community

Here we analyze the process of creation of the extended Sangha as the product of the relations of monks and nuns with lay followers. The structure emerging from those relations (Figure 5) looks like a reflection of the previously seen double grouping model, around the two monasteries of Garraf and Castellón, although with a much weaker connection between them.

Figure 5 in representation of the relational system, where the size of the nodes indicate the amount of relations received by any given actor, allows us to visualize the prominent role of the monks and nuns of the main monastery (Garraf) in the establishment of relations with the followers. These relations produce a larger and denser substructure than the one existing around the monks of the secondary monastery (Castellón). Overall, there are far more followers than monks and the result is that the number of relations initiated by the followers doubles the ones initiated by the monks. The system of relations connecting the ordained with the lay world (and as a result producing the entire Sangha) indicates a relational asymmetry which makes monks the centre of the reference system but lay people as the active engine of social creation of the large Sangha.

This system of lay-ordained relations follows a quite similar pattern to the relations that we have seen before analyzing the monastic network (the existence of two communities around both monasteries), but it has somewhat different centralization patterns. The most central roles here are those of the Lama acting as Prior (Actor

Figure 5. Relations connecting the ordained with the lay Sangha.

8), directly responsible for the educational programs and personal guidance, and Actor 5 (a nun that directs and organizes the collaboration of the followers with the monastery). They are the two most accessible public figures for the followers and play the main liaison role. Their centralizing role makes them the key monks in the creation of the lay community. The Abbot (4) joins them also with a quite central global reference role, and, at the local level, monks 13 and 34 are once again central in the relations with the followers of the Castellón monastery.

Along with these central ordained actors there also exists a group of followers that plays a very important role in the system creating the Sangha. Actors 68 and 67 are the most socially active, along with central reference actors 69, 86, 70 and 66. Their strong collaboration and ties to the monastery creates a potent relational bridge extending the sangha.

In brief, this system of relations creating the Sangha revolves around the trust vested in a reduced number of actors: the three principal monks and a small number of socially very active followers. These central monks and followers are the social action centre of the large Sangha network and make up a kind of inner-circle.

Comparing the centralization systems seen until now we can appreciate an interesting division of social action and spaces. So, while the Abbot is the key global reference actor, especially (as we have seen earlier) in the centralization of the ordained Sangha, the Prior (8), together with the nun (5), plays a centralizing role in the relations with the non-ordained Sangha. One Lama is the monastic reference while the other is the lay reference. Jointly they form a very socially powerful triad creating and maintaining together the complete Sangha.

4.3. The Spiritual Lay Community as a Network

The Monastery is an important reference point in the social lives of the faithful and their relations with it are intense. In addition to the monthly sessions of the Buddhist Philosophy Study Program, (Shedras) which most of them attend regularly, more than two thirds of them visit the Monastery frequently: 9% daily, 28% weekly, and one third at least once at month. They go to the Monastery for religious services and/or Initiation rituals (53% of the faithful), for advice and spiritual guidance from the Lamas (40%), and to do some voluntary work (44%) for the community. Buddhism becomes in this way an important social reference. It becomes a “small world” (Watts, 2003) of relational reference for the lay members of the Sangha.

The system of relations of the lay followers produces a network depicting the structure of its social life, which somehow follows the organizational structure in places of worship and/or practice (See Figure 6).

The lay community network is made up of four substructures (corresponding to two dharma houses on the left of the Figure and two monasteries on the right) linked together forming a rectangular space with the four subgroups as vertexes. Collective practices facilitate the relations among the followers which produce the ties among and within the four substructures. Every one of them subgroups corresponds to one of the spaces where regular religious practices take place: the two Dharma houses (Manresa, top left, and Cáceres, bottom left) and the monasteries of Garraf (bottom right) and Castellón (top right).

The lay component definitely makes a major contribution to the size, strength and reach of STL project and community. STL becomes a complex system that combines the practice and the project of the monks with those of the lay community. Additionally, and of most importance, the lay community plays a key role in interfacing and binding with the social milieu it acts as a perfect bridge between the religious community and society at large.

4.4. Linked to Society

Most contemporary organizational theories, and especially neo-institutional, isomorphism and resource dependency, stress the relations with the environment as fundamental for the adaptation and survival of any organiza-

Figure 6. The lay community network.

tion or institution. This would seem to be even more important for organizations open to society as is the case of STL. The study of relations between members of STL and their environment seems to confirm it and indicates an organization well embedded in society through networks.

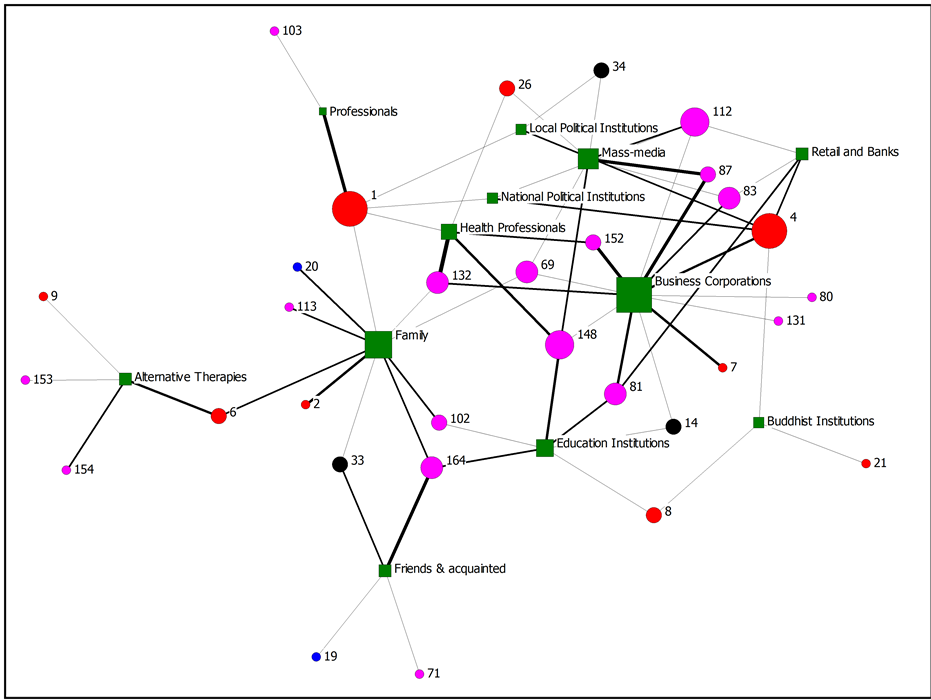

Figure 716 shows the existing relations of the ordained and lay members of the Community (represented as red and fuchsia circles) with the social, cultural, political and economic surroundings (represented as green squares)17. The dense mesh of relations clearly indicates the importance given by STL to its insertion and adjustment into its environment as a mechanism of legitimacy and survival as well as a mechanism to bring Dharma and Buddhist ideals to society.

The connections create a relational system where two differentiated spaces seem to arise: one which we could call “institutional relational space” (placed at the top right of the figure) and another which we could consider as “non-institutional” and more as a “social space” (left of the figure). Even though they are internally cohesive (especially the institutional space), the relationship between the two is weaker. This seems to point to the existence of two somehow differentiated social functions and spaces.

Relations with businesses, banks, political organizations and institutions, the mass-media, Buddhist organizations and education and healthcare institutions constitute the “institutional relational space”. It is a dense network (with many and intense relations) where corporations and the mass-media stand out as central focus of the

Figure 7. Social relations with environmenmt.

community’s relations. In this institutional space the Abbot’s role as social leader is highlighted, accompanied by some lay followers who are fundamental in creating and maintaining this part of the relational system.

The social space of “non-institutional” relations is clearly looser and less complex. It is created by relations with family and friends, and also with professionals and alternative therapy centers. The family is the main reference of this space and provides support and resources to both monks (resident and non-residents) and lay followers.

From the perspective of the neo-institutionalism contributions the “institutional relational space” can be seen as a provider of legitimacy and, from the point of view of the resource-dependency approach, as provider of religious and nonreligious resources. In terms of legitimation the relations with key social agents (businesses, political institutions, and the media) seem to grant and guarantee social approval and socio-political acceptance to the project.

We can differentiate a double system of relations and of legitimation: with the lay surroundings (the media, business, banks, political system) and with the religious lineage (Buddhist centers). The former allows for the integration and the reduction of potential conflicts with the economic, social, cultural and political milieu. The latter insures its connection with the ancestral Oriental religious tradition as well as with networks of Oriental and Western Buddhist organizations. In brief, this double system of relations supplies the resources and legitimation for the survival and continuity of the institution, be they economic, political, cultural or religious.

The relations with the media were at the time, as they had been in the past, of enormous importance in increasing the visibility of the STL Community, its project and its monasteries. The media played a crucial role in advertising a large part of the STL projects and spreading news, reports, and commentaries about their existence, their Buddhist proposals, and their activities and products such as conferences, CDs, books, motorcycle helmets, and the Medinat Project. Buddhism was opened and visible and STL Buddhist Monks became a reference in the whole country.

This “institutional relational space”, besides offering legitimacy and resources, also incorporates two avenues for their Buddhist social practice, the health and education systems, where STL brings both meditation techniques and Buddhist philosophy to contribute to wellbeing, improvement and growth.

In the “non-institutional space” the most noteworthy relations are the classic strong individual relations with family and friends. They play a double role of disseminating values and, at the same time, providing help and support to the monks and followers, acting as a support group. Also important in this space are relations with people and sectors with closely related visions, approaches, and practices (professionals and alternative therapy centers). The link to this sector of values and services is also a source for social legitimation in this specific social niche. In global terms this is fundamentally a support space based on the trust derived from strong relations and shared values.

In the complex relational system embedding the institution in its environment, the Abbot plays a key role thanks to his interaction with political, economic, and religious institutions. But, with the exception of the religious and political spaces, in the rest of the relations (with the media, the economic sectors, friends, family, etc.) the community of followers has the leading and fundamental role in the creation and maintenance of these systems. The complex of relations with the environment places STL in the political and social dynamics in such a way that it acquires social and institutional legitimacy and at the same time receives support for its projects.

5. Concluding: Buddhism and Networks

Sakya Tashi Ling (STL) is an interesting case of adaptation of old cosmovisions and forms to modern times, of how Buddhism keeps morphing to ensure its survival and expansion in new lands and new times.

STL has been experimenting with the modernization of Buddhism in two ways: adapting the product as well as its means of transmission. Its Buddhism becomes part of nonreligious products (music CDs, cookbooks, motorcycle helmets, etc.) which are distributed through nonreligious channels taking advantage of the market potential in order to transmit Buddhist values to society at large. The reach goes beyond the consumer that acquires their products. The press talks about them, they are on TV, their CDs are heard on the radio and in discotheques, and the helmet is seen on the highways. Their media impact is enormous compared to other religious groups. The fact that their message is oriented to society at large seems to imply the creation of their own social system as well as taking advantage of already existing transmission networks.

The study of STL from the Social Network Analysis perspective has allowed us to see and understand the symbiosis between its project and its organizational forms. Its way of understanding and practicing Buddhism works well with an organization open to society with a form that facilitates the creation of an extensive community (Sangha) as well as the transmission of its modern adaptation of Vajrayana, Sakya and Ngagpa Buddhist values to society at large. This implies a radical change in the organizational form and in the product: from a closed monastery model to an open monastery, from inward reclusive practice to outward open practice, and from the monks’ “enlightenment” to the whole of society’s enlightenment. The transmission of the Dharma through contemporary channels of disseminating values and knowledge, which are different from those of its time and society of origin, also implies the adaptation in the message itself.

We believe the success of the STL model lies in the combination of several dimensions and processes: being Westerner and involving aspects such as practicality, the combination of the individual dimension with the collective, and being Modern, with happiness and social relations and contacts as its key ingredients, and, above all, open to and towards society.

An important part of its success seems to be the utilization of networks, of relational systems, for the cohesion of the ordained and the lay spiritual community as well as for the connection with the surroundings as a mean to generate trust and to spread Buddhist teachings and practices.

A complex social system based in interactions between the members of the Community as well as between the different branches (the two Monastery houses and the Dharma Houses) is created. In addition to creating an extensive Community (including the ordained and non-ordained Sanghas), this network establishes bridges with society on a cultural, political and economic level. It enables the use of cultural, social and political institutions and the market itself as a diffusion mechanism. Carrying out social action through the Sangha strengthens its participation in the social fabric. As a result, the community acquires social entity and plays a role beyond religious practice.

From the organizational point of view it seems clear that the use of social relations and contacts is essential for the organization and its project. The networks created are flexible organizing mechanisms which adapt well to different functions. In this case we have seen how different structures have been formed according to their role and objective and how they combine closure with openness. Religious type relations, as well as those for the transmission of philosophical knowledge, are more centralized and create cohesive social systems. The ordained community networks are communion networks with high levels of identification, control and authority. They fulfill the function of creating a highly cohesive and compact community in communion with the guru, with the master. In contrast, action, transmission of values, and insertion into society is based on less compact and more open networks. The relations with the environment, the relations for creating the lay spiritual community, and those relations for introducing and practicing Buddhism in society, are more open, looser, and less centralized. The centralized networks fashion compact structures of religious communion. The loosest and least centralized networks facilitate the creation of the lay spiritual community and its penetration into the society that encircles it.

The result is a rich and complex social system with a great capacity for offering services and taking action. STL is an interesting case of relation between meaning and form. We have seen how the meaning, the project, generates a specific organizational form. In this case the aperture to society requires an organizational form that is also open. Networks guarantee the closure necessary for certain organizational functions as well as the necessary openness for its project towards society.

In summary, this is a model created by and for Westerners. The Vajrayana, the Sakya lineage and the Ngagpa tradition make up a value system sufficiently flexible and extensive to allow Sakya Tashi Ling to adjust its product as well as its organization to be what it wants to be: a Buddhism project in and for society. The use of Social Network Analysis has allowed us to find evidences for the conceptual frames guiding the study: organizations, interaction and creation of society, and the adaptation of Buddhism to modern times and new lands. Relations with the surrounding society are very important for legitimation and organizational survival as well as for the provision of its services (Buddhism). Interaction creates social and community life through networks that penetrate society and through which values, culture, happiness and Buddhism navigate.

6. Postscript

Impermanence is one of the central and key concepts in Buddhism. It expresses the notion that everything is changing, in a constant state of flux, and that nothing is permanent. Attachment to permanence is a source of suffering.

All organizations change. In November 2011, STL underwent an important transformatioin when a large part of the ordained Sangha left the Monastery, followed by a substantial part of the lay Sangha. Later they created another Buddhist institution called Sangha Activa (http://www.sanghaactiva.org/).

The study of the dynamics leading to such events and the later changes in STL and the creation of Sangha Activa will be the next story. The picture presented in this paper corresponds to the time period of the field work (2007-2010) but contains many elements (and tips) which will help us understand the later events.

Life is made up of moments, in very much the same way as the rivers described by Heraclitus in his quote “You could not step twice into the same rivers; for other waters are ever flowing on to you”

This paper is the analysis of one of such precious moments which we believe is worth sharing.

Acknowledgements

This research and paper has greatly benefited from the suggestions and ideas of Joanne Vitello, John Mohr, Wendell Bell, Juan Linz, José Luis C. Bosch, Anna Ramon, Alex J. Rodríguez, Juan Manuel García Jorba, Antonio Muñoz.

Funding

This paper is based on research funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation [SEJ2007-67714] and [COS2010-21761].

References

- Arroyo, L. (2013). Espiritualidad, Razón y Discordias: El Budismo Ahora y Aquí. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Barcelona: The University of Barcelona. http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/119736

- Barabási, A. L. (2003). Linked. New York: Plume.

- Batchelor, S. (1994). The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture. London: Aquarian, Harper Collins and Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.

- Baumann, M. (1994). The Transplantation of Buddhism to Germany: Processive Modes and Strategies of Adaptation. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 6, 35-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/157006894X00028

- Baumann, M. (1997a). Culture Contact and Valuation: Early German Buddhists and the Creation of a “Buddhism in a Protestant Shape”. Numen, 44, 270-295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1568527971655904

- Baumann, M. (1997a). The Dharma Has Come West: A Survey of Recent Studies and Sources. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 4, 194-211.

- Buchanan, M. (2003). Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Theory of Networks. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Burt, R. (1995). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Chaves, M., & Cann, D. E. (1992). Regulation, Pluralism, and Religious Market Structure: Explaining Religion’s Vitality, Rationality and Society, 4, 272-290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1043463192004003003

- Coleman, J. W. (2001). The New Buddhism: The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition. London: Oxford University Press.

- Díez de Velasco, F. (2009). La visibilización del Budismo en España. In M. Pintos de Cea-Naharro (Ed.), Budismo y cristianismo en diálogo (pp. 154-259). Madrid: Dykinson.

- Díez de Velasco, F. (2010). The Visibilization of Religious Minorities in Spain. Social Compass, 57, 235-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0037768610362410

- Einstein, M. (2008). Brands of Faith: Marketing Religion in a Commercial Age. New York: Routledge.

- Freeman, L. (1979). Centrality in Social Networks: Conceptual Clarification. Social Networks, 1, 215-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7

- Granovetter, M. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360-1380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/225469

- Laumann, E., & Pappi, F. (1976). Networks of Collective Action: A Perspective on Community Influence Systems. New York: Academic Press.

- Lenoir, F. (1999). The Adaptation of Buddhism to the West. Diogenes, 47, 100-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/039219219904718710

- Nietupski, P. (1999). Labrang: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery at the Crossroads of Four Civilizations. New York: Snow Lion Publications.

- Powell, W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (1991). The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Prebish, C. S., & Baumann, M. (2002). Westward Dharma. Buddhism beyond Asia. London: University of California Press.

- Prebish, C. S., & Keown, D. (2006). Introducing Buddhism. Routledge: New York.

- Prebish, C. S. (1996). Buddhist Monastic Discipline. India: Motilal Banarsidass Publications.

- Scott, J. (1991). Social Network Analysis. London: Sage.

- Tweed, T. A. (1998). Night-Stand Buddhists and other Creatures: Sympathizers, Adherents, and the Study of Religion. In D. R. Williams, & C. S. Queen (Eds.), American Buddhism. Methods and Findings in Recent Scolarship (pp. 71-90). Richmond: Curzon Press.

- Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815478

- Watts, D. J. (2003). Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Wellman, B. (1999). Networks in the Global Village. Colorado: Westview Press.

NOTES

1This article compiles results from a wide and detailed sociological study of a complex and peculiar organization, carried out during the period 2007-2010. Its framework is composed by many theoretical lines related to new organizational forms, interaction and systems for creation of society as well as forms of introducing the Buddhism in the West. We use a wide range of techniques for direct collection of data (participant and non-participant observation, interviews, surveys and different documental sources). All of them contribute to bring complementary perspectives of the complex reality of the organization.

2The authors want to express their gratitude to the Abbot of the Monasteries of Sakya Tashi Ling, as well as to the Prior of the Garraf Monastery for they collaboration and their effort to facilitate us the access to the Monasteries and the community members for this research. We would also like to thank the community members (either ordained or lay) for their generous contribution with their valuable time and their responses.

3Listening to the CD while reading this paper creates a calm atmosphere.

4Although references to Buddhism and Buddha could be found in literary pieces such as Barlaam et Iosaphat, of byzantine origin and translated to Latin in the XI century and to Spanish at the beginning of the XVII century, and in the works of such classical writers as Don Juan Manuel (in the XIII century) and Lope de Vega y Calderon de la Barca (in the XVII century) or the more recent poem of García Lorca (at the beginning of the XX century)

5The number of practitioners in 2009 was around 65.000, according to the Federación de Comunidades Budistas de España (the Spanish Federation of Buddhist Communities), and currently there are more than two hundred Buddhist centers (Arroyo, 2013). It is clearly becoming institutionalized (Díez de Velasco, 2009: p. 190).

6All of this leads us to consider the utilization of the theoretical and methodological approach of the Social Network analysis. This perspective allows us to discover dimensions that would remain hidden using any other instrument. It enables us to depict a part of the social system of the Monastery, of the social and relational system of an organization with several different dimensions: the ordained life; the communal life and the creation of a monastic collective life; the existence of a lay and very active community; and the social dimension of the Buddhist proposed by STL which implies its link with the social, cultural, political, and economical fabric to ensure its survival and the embedding of Buddhism in society.

7All members of the ordained Sangha are western natives coming from urban areas that surround the Monasteries.

8The analysis of social networks centres on the relations between the actors, and from these relations social structures are derived where social dynamics, marginalization, power, etc. are analyzed. The Social Networks Analysis is useful for studying the processes of cohesion, creation of groups, identity and articulation of collective action.

9Visit http://www.monjesbudistas.org/ and http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sakya_Tashi_Ling.

10These monks are not closed in individual cells solo-practicing to attain their own “Enlightenment”. Their main goal is to attain the “Enlightenment” for the society at large.

11The ordained Sangha is comprised of all of those who have begun the monastic path.

12For the global analysis, we have aggregated the 15 matrices derived from de questionnaire. The matrices are based on the 15 following questions:

-A1. With whom do you speak about the Sakya Tashi Ling Project (the mission, the vision, and its values)?

-A2. With whom are you in agreement about the mission, the vision and the values of Sakya Tashi Ling?

-A3. To whom do you talk about what is important for the Community?

-A4. With whom are you in agreement about what is important for the Community?

-A6. With whom do you talk about current and future projects of the Community?

-A7. With whom do you collaborate to complete your work in the Community?

-A8. With whom do you discuss about what happens and who does what in the Community?

-A9. To whom do you go to ask for advice before you make a decision?

-A10. To whom do you go when looking for help or ideas and suggestions to solve a problem?

-A11. With whom do you discuss ideas, innovations and betters ways to do things?

-A12. Who comes to you to ask for advice before making decisions?

-A13. With whom do you discuss affairs related to the needs of visitors and their requests?

-A14. To whom would you explain your spiritual problems?

-A15. Who would you ask for help to deal with others’ positions and/or approaches which you consider not adequate?

-A16. With whom do you have a friendly relationship?

13The colors of the circles differentiate the four types of monks and nuns: red (residents of the Garraf Monastery), blue (members but non-residents of the Garraf Monastery), black (residents of the Castellón Monastery), and grey (residents of the Peru Monastery). The fuchsia color identifies the non-ordained members of the community (the faithful). The color of the lines indicates if the relation is reciprocal (red) or not (blue). The thickness of the lines indicates the relational intensity. In this case, they are proportional to the number of relations between each pair of actors. The size of the circles indicates the number of direct relations that that actor receives.

14As a standard procedure, the mean value of the relational intensity in a network is used as a cut-point in order to dichotomize the matrix in order to show the core or the system of strong relations.

16The colors of the circles differentiate the four types of monks and nuns: red (residents of the Garraf Monastery), blue (members but non-residents of the Garraf Monastery), black (residents of the Castellón Monastery), and grey (residents of the Peru Monastery). The fuchsia color identifies the non-ordained members of the community (the faithful). The color of the lines indicates if the relation is reciprocal (red) or not (blue). The thickness of the lines indicates the relational intensity. In this case, they are proportional to the number of relations between each pair of actors. The size of the circles indicates the number of direct relations that that actor receives.

17Individual institutions or people with whom member of STL establish relations have been grouped in the following categories: Business corporations, Retail and Banks, Mass-media, Local political institutions, National political institutions, Health professionals, other Professionals, Educational institutions, Alternative therapies, Friends and acquainted, Family, and Buddhist institutions.