Open Journal of Depression

Vol.3 No.3(2014), Article

ID:48963,12

pages

DOI:10.4236/ojd.2014.33015

Does Early Improvement in Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Affect Remission Rates? A Post-Hoc Analysis of Pooled Duloxetine Clinic Trials

Murat Altin1*, Eiji Harada2, Alexander Schacht3, Lovisa Berggren3, Daniel Walker4, Hector Dueñas5

1Eli Lilly-Turkey, Istanbul, Turkey

2Lilly Research Laboratories Japan, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Kobe, Japan

3Eli Lilly and Company, Health Technology Appraisal Group, Bad Homburg, Germany

4Lilly USA, LLC, Indianapolis, USA

5Eli Lilly de México, Mexico City, Mexico

Email: *altin_murat@lilly.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 25 May 2014; revised 30 June 2014; accepted 23 July 2014

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and a comorbid anxiety disorder or significant anxiety symptoms have decreased functioning, increased risk of suicidality, and worse post-treatment outcomes. This pooled analysis of 8 duloxetine MDD trials was designed to determine whether early improvement in anxiety symptoms predicts MDD remission. Methods: Eight trials were pooled. Patients with a baseline 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD17) anxiety/somatization factor score ≥7 were considered to have anxious depression. Early response on the HAMD17 total score was defined as a 20% reduction at weeks 2 or 4, a 30% reduction at weeks 2 or 4, or a 50% reduction at weeks 2 or 4 in the HAMD17 anxiety subscale. Each category was analyzed separately for all patients. MDD remission is a score of ≤7 on the HAMD17 total score at study endpoint. Results: The early responder group in each analysis showed greater numerical improvement at endpoint on the HAMD17 total score than the nonresponder group. Duloxetine showed statistically significantly greater improvement than placebo in most nonresponder and responder subgroups. There were no statistically significant interaction effects for the difference between duloxetine and placebo for any of the anxious categories. Conclusion: Although patients who responded in the various response categories had greater numerical improvement and greater remission rates than nonresponding patients, the response and nonresponse groups did not differ statistically regarding the treatment effect of duloxetine. Therefore, early improvement in anxiety symptoms was not a predictor of greater endpoint remission of depressive symptoms for duloxetine treatment.

Keywords:Anxiety, Clinical Trials, Duloxetine, Early Response, Major Depressive Disorder, Remission

1. Introduction

Depression affects more than 350 million people worldwide and has a lifetime prevalence range of 10% to 15% (Lépine & Briley, 2011; World Health Organization, 2012). Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and by 2020 is predicted to be second only to cardiovascular disease in overall disease burden worldwide (Lopez & Murray, 1998; World Health Organization, 2008). Unfortunately, treatment of depression is often either nonexistent or inadequate in the majority of people with major depressive disorder (MDD) (Kessler et al., 2003; Lépine, Gastpar, Mendlewicz, & Tylee, 1997). The percentage of people with MDD in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study who were treated was only 51.6%; furthermore, only 41.9% of those patients received adequate levels of treatment (Kessler et al., 2003). The majority of patients who are not adequately treated for their symptoms will relapse (Bakish, 2001). Studies have shown that relapse rates are much higher in patients with partial remission than in those who experience complete remission (Bakish, 2001; Pintor, Gastó, Navarro, Torres, & Fañanas, 2003). In the treatment of depression, early symptom improvement may be a clinically useful indicator for successful treatment or treatment failure (Nierenberg, Qyitkin, Kremer, Keller, & Thase, 2004; Wade & Friis Anderson, 2006). Some analyses have suggested that early drug-specific symptom improvement is predictive of greater overall response and symptom resolution at endpoint (Nierenberg et al., 2004; Wade & Friis Anderson, 2006).

Anxious depression has been defined as people with MDD having a comorbid anxiety disorder or having high levels of anxiety symptoms (Fava et al., 2004). The frequency of a comorbid anxiety disorder or significant levels of anxious symptoms in people with MDD is approximately 50% (Fava et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 1996, 2003). A significant percentage of patients with MDD have comorbid anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Rush et al., 2005; Zimmerman, Chelminski, & McDermut, 2002). Anxious depression has been shown to be associated with increased symptom severity, worse functioning, greater risk of suicidality, and higher rates of unemployment (Farabaugh et al., 2012; Nelson, 2008). People with anxious depression tend to have worse outcomes than patients with nonanxious depression, including a reduced likelihood of response and remission, increased rate of side effects, and slower rate of recovery from an MDD episode (Fava et al., 2008; Nelson, 2008). Among other variables, residual anxiety symptoms, high baseline levels of anxiety, or having a comorbid anxiety disorder have been shown to predict relapse or recurrence of MDD (Dombrovski et al., 2007; Parker, Wilhelm, Mitchell, & Gladstone, 2000; Wilhelm, Parker, Dewhurst-Savellis, & Asghari, 1999; Yang et al., 2010).

A recent study found that the severity of anxiety at baseline adversely affected depression severity at 12 months and that a reduction of anxiety within the first 3 months leads to additional improvement in depression (Bair et al., 2013). Few studies in MDD patients have evaluated whether early onset of improvement in anxiety symptoms results in higher rates of remitted depression. A 12-week study of active treatment in patients with MDD found that early change (1 week) in items of the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD17) (Hamilton, 1960) anxiety/somatization factor was predictive of achieving remission at endpoint for only item 13 (general somatic symptoms) but not for the other items (Farabaugh et al., 2005). In a post-hoc analysis of a different study, only early improvement in item 12 (gastrointestinal somatic symptoms) was significantly predictive of MDD remission, although item 13 just missed reaching statistical significance (Farabaugh et al., 2010). A study by Davidson, Meoni, Haudiquet, Cantillon and Hackett (2002) found that the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine was significantly better than placebo in achieving remission in severely anxious-depressed patients, whereas the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) fluoxetine did not separate from placebo. Similarly, another study showed that venlafaxine improved psychic anxiety better than SSRIs (Silverstone, Entsuah, & Hackett, 2002).

Katz and colleagues (2004) found that antidepressant drugs with pharmacologically different mechanisms of action produced different early therapeutic effects. Duloxetine is an SNRI that has been approved for the treatment of MDD and GAD in many countries worldwide. Duloxetine has shown early separation from placebo (within the first 2 weeks of treatment) on core depressive systems, including depressed mood, guilt, suicidal ideation, psychomotor retardation, and psychic anxiety (Hirschfeld, Mallinckrodt, Lee, & Detke, 2005; Shelton et al., 2007). In a post-hoc analysis of a double-blind, placeboand active-controlled study of duloxetine in patients with MDD, several items and factors of the HAMD17 that showed early improvement were predictors of sustained MDD remission (Katz, Meyers, Prakash, Gaynor, & Houston, 2009). However, the analysis was done in all patients and not separately in anxious and nonanxious patients. In the current post-hoc analysis, 8 randomized, placebo-controlled, duloxetine trials in MDD having a duration of 4 to 12 weeks were pooled to assess whether early improvement in anxiety symptoms resulted in greater rates of MDD remission. In this analysis, patients were considered to have anxious depression if they had a HAMD17 anxiety/somatization factor subscale score of ≥7 at baseline (Fava et al., 2008). This definition of anxious depression has been used in previous studies, including analyses of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial (Farabaugh et al., 2012; Fava et al., 2008). Using this definition of anxious depression, patients from the 8 pooled duloxetine MDD trials were assigned to either having or not having anxious depression. The primary objective of this study was to determine whether early improvement in anxiety symptoms predicted remission of MDD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Data were pooled from 8 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of duloxetine for the treatment of MDD conducted by Eli Lilly and Company (Table 1). The 8 studies took place from November 2000 to March 2011. Data were taken from short-term studies and from the acute-treatment phase of those studies that had extensions. Relapse studies are not included in the analysis set. Although patients were randomized to the 60 to 120 mg/day arm of duloxetine in some studies, patients randomized to duloxetine arms ˃60 mg/day were excluded from these analyses. The HAMD17 scale had to have been included in the study. These 8 studies comprised the full set of appropriate and available placebo-controlled studies at the time this work was initiated.

All study protocols were developed in accordance with the ethical standards of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Before studies began, all patients provided written informed consent, and each clinical study site’s institutional review board approved the protocol

2.2. Patient Population

Patients were ≥18 years, male or female outpatients with MDD as defined by criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) or DSM, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Patients were excluded from each study if they had any current primary psychiatric or neurologic diagnosis other than MDD, including any anxiety disorder (1 study allowed mild dementia); had a serious

Table 1 . Summary of the 8 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in major depressive disorderused in the analyses.

HMFS: only first 12 weeks of study included in the analyses. b. Patients randomized to duloxetine arms greater than 60 mg/day were excluded from these analyses.

medical illness; had a history of substance abuse or dependence within 1 year of study entry; or had a positive urine drug screen. Details for each study can be found in the primary publication (Table 1). A total of 2630 patients from the 8 studies were included in the present study. Patients were analyzed (grouped) based on whether they were considered to have anxious depression. Anxious depression in the current analyses was defined as a HAMD17 anxiety/somatization factor score ≥ 7 at baseline (Fava et al., 2008).

2.3. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure for these analyses is the HAMD17 total score. Response was defined as ≥50% improvement from baseline to endpoint on the HAMD17 total score. Remission was defined as a score of ≤7 on the HAMD17 total score at endpoint. The 6-item HAMD17 anxiety/somatization subscale consists of the sum of items 10 (psychic anxiety), 11 (somatic anxiety), 12 (gastrointestinal somatic symptoms), 13 (general somatic symptoms), 15 (hypochondriasis), and 17 (insight). Several other scales were measured at baseline to determine whether there were significant differences between the anxious and nonanxious subgroups. These included the following HAMD17 subscales: Maier, Retardation, Sleep, Bech, and Mood. Other scales included the Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale (MADRS) (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979), the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan, & Raj, 1996) to assess functional impairment, the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994) to assess pain and functioning, the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) (Guy, 1976) to measure overall improvement, and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA) (Hamilton, 1959).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The continuous endpoints were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) via the following approach: one ANCOVA model was calculated for each study with the fixed effects including treatment, anxious (y/n), treatment by anxious (y/n) interaction, and baseline score of the endpoint evaluated as covariates. For logistic regression analyses, an additional model included all 2- and 3-way interactions between treatment, study, and anxious (y/n) to check for heterogeneity. Effect sizes in each model were calculated for least squares (LS) mean differences, divided by the standard deviation (SD) of the residuals provided by the model of this study. Overall LS mean estimates and effect sizes were calculated as a weighted mean of the corresponding estimates in all studies, with weights based on within-study variance, assuming a fixed study effect. The binary outcomes were analyzed using logistical regression adjusting for study within the anxious and nonanxious patients. The impact of anxiety being present or not at baseline on the treatment response of the endpoints will be described. The mean changes in HAMD17 total score, items, and subscales were assessed via last observation carried forward to endpoint. Early response on the HAMD17 total score was defined as one of the following: a 20% reduction at weeks 2 or 4, a 30% reduction at weeks 2 or 4, or a 50% reduction at weeks 2 or 4 in the HAMD17 anxiety/somatization subscale score. Each of these 6 categories was analyzed separately for all patients. Remission of MDD is a score of ≤7 on the HAMD17 total score at endpoint.

Fixed effects using ANCOVA for mean changes in HAMD17 total score, subscales, and items and logistic regression for binary endpoints, including study, treatment, anxious (y/n), and baseline score of the endpoint, were evaluated. An additional logistic regression model included all 2- and 3-way interactions between treatment, study, and anxious (y/n). Because this was a post-hoc analysis, no adjustment for multiplicity was made and results should be interpreted as being exploratory in nature. All confidence intervals (CIs) presented were 95% CIs, and statistical significance was defined as a p-value <5%. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

The mean age of patients (N = 2630) was 50.1 years (SD = 17.5 years), with the majority of patients being female (64%) and Caucasian (75%). Baseline patient characteristics for anxious and nonanxious-depressed patients are shown in Table2 There were statistically significant differences between the groups for gender, race, geography, and all efficacy measures. The percentage of patients completing the studies in which they were enrolled was not significantly different between the anxious and nonanxious groups (Table 3). The most common overall reasons for discontinuing the study were adverse event (8%) and subject decision (6%).

Table 2. Baseline patient characteristics.

Abbreviations: BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; CGI-S = Clinical Global Improvement of Severity; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Scale Scores; HAMD17 = 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MADRS = Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale; MDD = major depressive disorder; SD = standard deviation; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; Tx = treatment; USA = United States of America.

Table 3. Patient disposition.

Overall, the percentage of patients attaining a 50% response rate at endpoint was 38.2% (duloxetine, 42.9%; placebo, 30.3%) in the nonanxious group and 38% (duloxetine, 41.7%; placebo, 32.6%) in the anxious group. The percentage of patients attaining remission status at endpoint was 32.5% (duloxetine, 36.2%; placebo, 26.3%) in the nonanxious group and 20.3% (duloxetine, 22.9%; placebo, 16.6%) in the anxious group. The LS mean difference between duloxetine and placebo on the HAMD17 total score was –1.94 (standard error [SE] = 0.39) for the nonanxious group (duloxetine, –7.70; placebo, –5.77) and –2.26 (SE = 0.40) for the anxious subgroup (duloxetine, –8.30; placebo, –6.31). The LS mean change treatment difference within each group was statistically significant (both p < 0.0001), but the interaction effect between treatment and anxious group was nonsignificant (p = 0.575). The odds ratio (95% CI) of duloxetine versus placebo for achieving a 50% response rate at week 8 was 1.740 (95% CI: 1.371, 2.209) for the nonanxious group and 1.508 (95% CI: 1.192, 1.909) for the anxious group. The odds ratio (95% CI) for reaching remission at week 8 was 1.596 (95% CI: 1.240, 2.054) for the nonanxious group and 1.589 (95% CI: 1.187, 2.127) for the anxious group. The interaction effect between the treatment and anxious group was nonsignificant for both the response and remission rates.

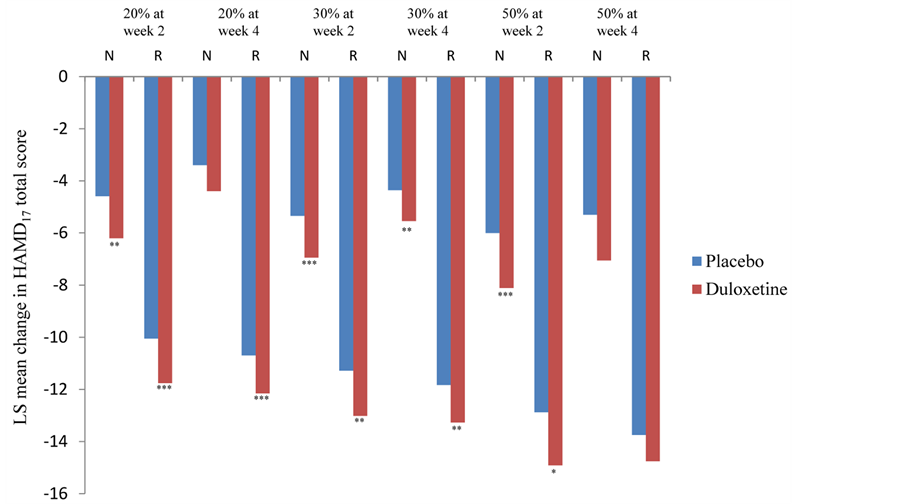

The mean change in the HAMD17 total score based on response status and week is shown in Figure 1. The responder subgroup in each analysis showed greater improvement at endpoint than the nonresponder subgroup. Moreover, duloxetine showed statistically significantly greater improvement than placebo in most (9 of 12) of the nonresponder and responder subgroups (Figure 1). However, there were no statistically significant interaction effects for the difference between duloxetine and placebo for any of the response categories. That is, the difference between duloxetine and placebo for nonresponder and responder subgroups was not significantly different within each of the 6 early-response categories.

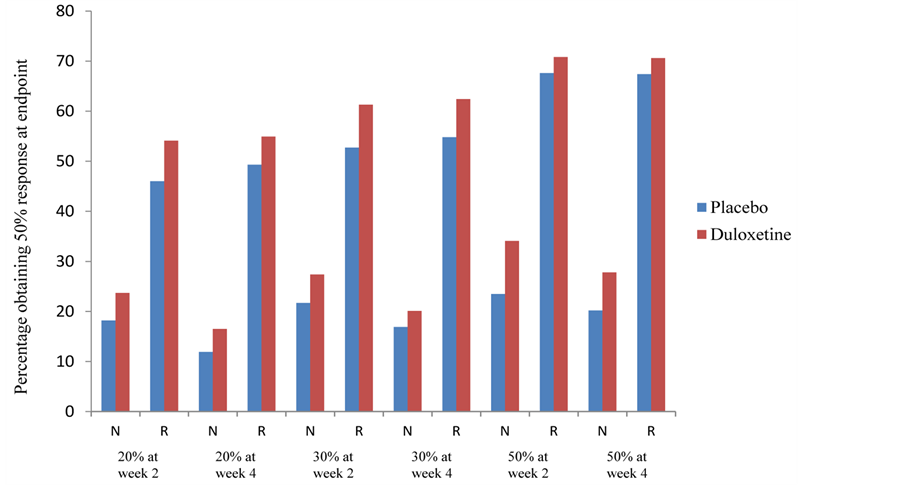

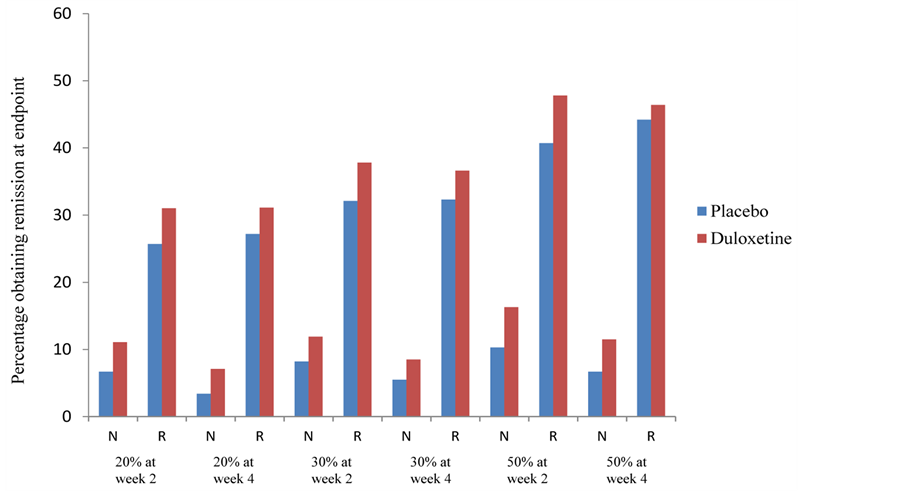

Table 4 presents the odds of whether placeboor duloxetine-treated patients (early responders and nonresponders) have a greater chance of obtaining a 50% response rate at endpoint. In all cases, duloxetine-treated patients had greater odds of achieving response at endpoint compared with placebo, although only a few reached statistical significance. Figure 2 shows the percentage of patients (early responders and nonresponders) who reached a 50% response rate at endpoint for each of the response categories. The odds ratios for early responders and nonresponders in reaching remission showed that duloxetine had numerically greater odds of doing so than placebo in all categories, although only 5 were statistically significant (Table 5). Figure 3 shows the percentage

Figure 1. Mean changes in 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD17) total score by response status for anxious-depression group at endpoint (week 8). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 versus placebo. Total number of patients: placebo = 525, duloxetine = 774. Number of patients per response status varies for each analysis. Abbreviations: LS = least squares; N = nonresponder; R = responder.

Figure 2. Frequency of 50% response at week 8 by response status as measured by the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Total number of patients: placebo = 525, duloxetine = 774. Number of patients per response status varies for each analysis. Abbreviations: N = nonresponder; R = responder.

Figure 3. Frequency of remission at week 8 by response status as measured by the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Total number of patients: placebo = 525, duloxetine = 774. Number of patients per response status varies for each analysis. Abbreviations: N = nonresponder; R = responder.

of patients that achieved remission at endpoint for each of the response categories.

4. Discussion

Overall, there was not a significant interaction effect between the treatment and anxious group for both response and remission. That is, the difference between placebo and duloxetine in the 2 groups was similar; thus, having

Table 4 . Odds ratios of duloxetine versus placebo in patients achieving or not achieving a 50% response rate at endpoint.

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HAMD17 = 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Total number of patients: duloxetine = 774; placebo = 525. Odds ratio is based on duloxetine versus placebo. aDuloxetine is statistically significantly more likely than placebo to achieve a 50% response rate at endpoint.

Table 5. Odds ratios of duloxetine versus placebo in patients achieving or not achieving remission at endpoint.

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HAMD17 = 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Total number of patients: duloxetine = 774; placebo = 525. Odds ratio is based on duloxetine versus placebo. aDuloxetine is statistically significantly more likely than placebo to achieve remission at endpoint.

anxious depression did not result in significantly lower response and remission rates than patients without anxious depression under duloxetine treatment. Similar to previous studies (Fava et al., 2008), patients with anxious depression were significantly more depressed as measured on both the MADRS and HAMD17 depression scales than patients with nonanxious-depression. Anxious patients also experienced worsened functioning, global impairment, and significantly higher levels of pain. It has been shown that longer duration of an MDD episode (Judd et al., 2000; Keller, Lavori, Rice, Coryell, & Hirschfeld, 1986) and/or a greater number of previous MDD episodes (Bulloch, Williams, Lavorato, & Patten, 2014; Kessing, Hansen, Andersen, & Angst, 2004; Lin et al., 1998) may result in patients being harder to treat. However, this does not necessarily imply that the difference between active and placebo treatment is changed, as observed in a recent analysis of pooled duloxetine studies (Dodd, Berk, Kelin, Mancini, & Schacht, 2013). In our pooled analysis, the anxious-depressed group showed nonsignificant differences from the nonanxious group for both of these baseline illness parameters. Pain levels were significantly higher in the anxious-depression group compared with the nonanxious group. Pain has been shown to be a predictor of relapse (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979) and predictor of longer time to remission (Karp et al., 2005). However, response and remission rates were similar between the anxious and nonanxious groups, although it is unknown whether relapse rates would have differed between the 2 groups based on the acute studies included in the current analysis.

Although anxious-depressed patients who met response criteria at each of the cutoffs showed much higher response and remission rates than those anxious-depressed patients who did not meet the response criteria, none of the early-response categories was found to predict significantly better endpoint remission rates under duloxetine treatment. That is, the difference between placebo and duloxetine for the responder groups was not significantly different from the comparable nonresponder group. Thus, patients with anxious depression meeting response criteria was a prognostic factor for greater mean change in depression scores, as well as better response and remission rates at endpoint, but it was not predictive of improved depressive outcomes (duloxetine vs. placebo).

The anxious-depressed patients in these analyses had a mean HAMD17 anxiety/somatization score of 8.3. The amount of anxiety these patients experienced may not be high enough to observe increased remission rates in early responders. Many patients with MDD often have much higher levels of anxiety symptoms or have a comorbid anxiety disorder (Fava et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 1996, 2003), and these patients might be a better population to study to answer the question of whether an early response in anxiety symptoms leads to increased remission rates of MDD. A mean score of 8 (24 is maximum) on the HAMD17 anxiety/somatization score is actually fairly low even though a score of ≥7 is considered to qualify a patient as having anxious depression (Fava et al., 2008).

One limitation of this study was that these were post-hoc analyses. The clinical trials had a number of exclusions, such as comorbid psychiatric disorders and various other medical illnesses. Thus, one should be cautious in extrapolating these results to the general population of patients with MDD. However, there are several strengths to these analyses, including that the pooled data all came from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. The analyses contained a sizable number of patients, including 1331 patients without anxious depression and 1299 patients with anxious depression. Importantly, the study designs of the 8 clinical trials used in these pooled analyses were similar, including most of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

5. Conclusion

In this pooled analysis of duloxetine MDD studies, anxious-depressed patients who responded early in their anxiety symptoms showed higher rates of response and remission compared with patients who did not show early improvement in anxiety symptoms. However, the differences between placebo and duloxetine were not significantly different in the response and nonresponse subgroups; thus early response in anxiety symptoms was a prognostic factor for greater endpoint remission of MDD symptoms, but it was not a predictor of greater endpoint remission for duloxetine. This was true for each of the 6 response categories.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Renee Granger for editing and proofreading the manuscript.

Role of Funding Source

This project was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Contributors

Authors MA, EH, AS, and HD designed the project. Authors DW, MA, EH, HD, and AS managed the literature searches. Authors AS and LB managed the statistical analyses and authors DW and MA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

This project was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. MA, EH, AS, DW, and HD are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. LB is a contractor working for Lilly.

References

- Bair, M. J., Poleshuck, E. L., Wu, J., Krebs, E. K., Damush, T. M., Tu, W., & Kroenke, K. (2013). Anxiety but Not Social Stressors Predict 12-Month Depression and Pain Severity. Clinical Journal of Pain, 29, 95-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182652ee9

- Bakish, D. (2001). New Standard of Depression Treatment: Remission and Full Recovery. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 5-9.

- Brannan, S. K., Mallinckrodt, C. H., Brown, E. B., Wohlreich, M. M., Watkin, J. G., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2005). Duloxetine 60 mg Once-Daily in the Treatment of Painful Physical Symptoms in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 39, 43-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.04.011

- Bulloch, A., Williams, J., Lavorato, D., & Patten, S. (2014). Recurrence of Major Depressive Episodes Is Strongly Dependent on the Number of Previous Episodes. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 72-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.22173

- Cleeland, C. S., & Ryan, K. M. (1994). Pain Assessment: Global Use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals of Academic Medicine Singapore, 23, 129-138.

- Davidson, J. R. T., Meoni, P., Haudiquet, V., Cantillon, M., & Hackett, D. (2002). Achieving Remission with Venlafaxine and Fluoxetine in Major Depression: Its Relationship to Anxiety Symptoms. Depression and Anxiety, 16, 4-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.10045

- Detke, M. J., Lu, Y., Goldstein, D. J., Hayes, J. R., & Demitrack, M. A. (2002). Duloxetine, 60 mg Once Daily, for Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63, 308-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v63n0407

- Detke, M. J., Lu, Y., Goldstein, D. J., McNamara, R. K., & Demitrack, M. A. (2002). Duloxetine 60 mg Once Daily Dosing Versus Placebo in the Acute Treatment of Major Depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 36, 383-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3956(02)00060-2

- Dodd, S., Berk, M., Kelin, K., Mancini, M., & Schacht, A. (2013). Treatment Response for Acute Depression Is Not Associated with Number of Previous Episodes: Lack of Evidence for a Clinical Staging Model For Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150, 344-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.016

- Dombrovski, A. Y., Mulsant, B. H., Houck, P. R., Mazumdar, S., Lenze, E. J., Andreescu, C. et al. (2007). Residual Symptoms and Recurrence during Maintenance Treatment of Late-Life Depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 103, 77-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.020

- Farabaugh, A., Mischoulon, D., Fava, M., Wu, S. L., Mascarini, A., Tossani, E., Alpert, J. E. (2005). The Relationship between Early Changes in the HAMD-17 Anxiety/Somatization Factor Items and Treatment Outcome among Depressed Outpatients. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20, 87-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200503000-00004

- Farabaugh, A. H., Bitran, S., Witte, J., Alpert, J., Chuzi, S., Clain, A. J. et al. (2010). Anxious Depression and Early Changes in the HAMD-17 Anxiety-Somatization Factor Items and Antidepressant Treatment Outcome. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25, 214-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e328339fbbd

- Farabaugh, A., Alpert, J., Wisniewski, S. R., Otto, M. W., Fava, M., Baer, L. et al. (2012). Cognitive Therapy for Anxious Depression in STAR*D: What Have We Learned? Journal of Affective Disorders, 142, 213-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.029

- Fava, M., Alpert, J. E., Carmin, C. N., Wisniewski, S. R., Trivedi, M. H., Biggs et al. (2004). Clinical Correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with Major Depressive Disorder in STAR*D. Psychological Medicine, 34, 1299-1308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704002612

- Fava, M., Rush, A. J., Alpert, J. E., Balasubramani, G. K., Wisniewski, S. R., Carmin, C. N. et al. (2008). Difference in Treatment Outcome in Outpatients with Anxious Versus Nonanxious Depression: A STAR*D Report. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 342-351. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868

- Guy, W. (1976). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication (ADM). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health, 76-338.

- Hamilton, M. (1959). The Assessment of Anxiety States by Rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32, 50-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x

- Hamilton, M. (1960). A Rating Scale for Depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

- Hirschfeld, R. M., Mallinckrodt, C., Lee, T. C., & Detke, M. J. (2005). Time Course of Depression-Symptom Improvement during Treatment with Duloxetine. Depression and Anxiety, 21, 170-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.20071

- Judd, L. L., Paulus, M. J., Schettler, P. J., Akiskal, H. S., Endicott, J., Leon, A. C. et al. (2000). Does Incomplete Recovery from First Lifetime Major Depressive Episode Herald a Chronic Course of Illness? The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1501-1504. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1501

- Karp, J. F., Scott, J., Houck, P., Reynolds 3rd, C. F., Kupfer, D. J., & Frank, E. (2005). Pain Predicts Longer Time to Remission during Treatment of Recurrent Depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 591-597. http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v66n0508

- Katz, M. M., Tekell, J. L., Bowden, C. L., Brannan, S., Houston, J. P., Berman, N., & Frazer, A. (2004). Onset and Early Behavioral Effects of Pharmacologically Different Antidepressants and Placebo in Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29, 566-579. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300341

- Katz, M. M., Meyers, A. L., Prakash, A., Gaynor, P. J., & Houston, J. P. (2009). Early Symptom Change Prediction of Remission in Depression Treatment. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 42, 94-107.

- Keller, M. B., Lavori, P. W., Rice, J., Coryell, W., & Hirschfeld, R. M. (1986). The Persistent Risk of Chronicity in Recurrent Episodes of Nonbipolar Major Depressive Disorder: A Prospective Follow-Up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143, 24-28.

- Kessing, L. V., Hansen, M. G., Andersen, P. K., & Angst, J. (2004). The Predictive Effect of Episodes on the Risk of Recurrence in Depressive and Bipolar Disorders—A Life-Long Perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109, 339-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00266.x

- Kessler, R. C., Nelson, C. B., McGonagle, K. A., Liu, J., Swartz, M., & Blazer, D. G. (1996). Comorbidity of DSM-III-R Major Depressive Disorder in the General Population: Results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 17-30.

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R. et al. (2003). The Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 3095-3105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.23.3095

- Lépine, J. P., Gastpar, M., Mendlewicz, J., & Tylee, A. (1997). Depression in the Community: The First Pan-European Study DEPRES (Depression Research in European Society). International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 12, 19-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004850-199701000-00003

- Lépine, J. P., & Briley, M. (2011). The Increasing Burden of Depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease Treatment, 7, 3-7.

- Lin, E. H. B., Katon, W. J., VonKorff, M., Russo, J. E., Simon, G. E., Bush, T. M. et al. (1998). Relapse of Depression in Primary Care: Rate and Clinical Predictors. Archives of Family Medicine, 7, 443-449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archfami.7.5.443

- Lopez, A. D., & Murray, C. C. (1998). The Global Burden of Disease, 1990-2020. Nature Medicine, 4, 1241-1243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/3218

- Montgomery, S. A., & Asberg, M. (1979). A New Depression Scale Designed to Be Sensitive to Change. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 382-389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

- Mundt, J. C., DeBrota, D. J., & Greist, J. H. (2007). Anchoring Perceptions of Clinical Change on Accurate Recollection of the Past: Memory Enhanced Retrospective Evaluation of Treatment (MERET?). Psychiatry, 4, 39-45.�

- Nelson, J. C. (2008). Anxious Depression and Response to Treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 297-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07121927

- Nierenberg, A. A., Qyitkin, F. M., Kremer, C., Keller, M. B., & Thase, M. E. (2004). Placebo-Controlled Continuation Treatment with Mirtazapine: Acute Pattern of Response Predicts Relapse. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29, 1012-1018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300405

- Nierenberg, A. A., Greist, J. H., Mallinckrodt, C. H., Prakash, A., Sambunaris, A., Tollefson, G. D., & Wohlreich, M. M. (2007). Duloxetine Versus Escitalopram and Placebo in the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: Onset of Antidepressant Action, a Non-Inferiority Study. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 23, 401-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1185/030079906X167453

- Oakes, T. M., Myers, A. L., Marangell, L. B., Ahl, J., Prakash, A., Thase, M. E., & Kornstein, S. G. (2012). Assessment of Depressive Symptoms and Functional Outcomes in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Treated with Duloxetine versus Placebo: Primary Outcomes from Two Trials Conducted under the Same Protocol. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 27, 47-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hup.1262

- Parker, G., Wilhelm, K., Mitchell, P., & Gladstone, G. (2000). Predictors of 1-Year Outcome in Depression. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 34, 56-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2000.00698.x

- Pintor, L., Gastó, C., Navarro, V., Torres, X., & Fañanas, L. (2003). Relapse of Major Depression after Complete and Partial Remission during a 2-Year Follow-Up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 73, 237-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00480-3

- Raskin, J., Wiltse, C. G., Siegal, A., Sheikh, J., Xu, J., Dinkel, J. J. et al. (2007). Efficacy of Duloxetine on Cognition, Depression, and Pain in Elderly Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: An 8-Week, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 900-909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.900

- Robinson, M., Oakes, T. M., Raskin, J., Liu, P., Shoemaker, S., & Nelson, J. C. (2014). Acute and Long-Term Treatment of Late-Life Major Depressive Disorder: Duloxetine versus Placebo. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22, 34-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.019

- Rush, A. J., Zimmerman, M., Wisniewski, S. R., Fava, M., Hollon, S. D., Warden, D. et al. (2005). Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in Depressed Outpatients: Demographic and Clinical Features. Journal of Affective Disorders, 87, 43-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.005

- Sheehan, D. V., Harnett-Sheehan, K., & Raj, B. A. (1996). The Measurement of Disability. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11, 89-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015

- Shelton, R. C., Prakash, A., Mallinckrodt, C. H., Wohlreich, M. M., Raskin, J., Robinson, M. J., & Detke, M. J. (2007). Patterns of Depressive Symptom Response in Duloxetine-Treated Outpatients with Mild, Moderate or More Severe Depression. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 61, 1337-1348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01444.x

- Silverstone, P. H., Entsuah, R., & Hackett, D. (2002). Two Items on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Are Effective Predictors of Remission: Comparison of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors with the Combined Serotonin/Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor, Venlafaxine. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17, 273-280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200211000-00002

- Wade, A., & Anderson, H. F. (2006). The Onset of Effect for Escitalopram and Its Relevance for the Clinical Management of Depression. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 22, 2101-2110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1185/030079906X148319

- Wilhelm, K., Parker, G., Dewhurst-Savellis, J., & Asghari, A. (1999). Psychological Predictors of Single and Recurrent Major Depressive Episodes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 54, 139-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00170-0

- World Health Organization (2008). The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/

- World Health Organization (2012). Depression, Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- Yang, H., Chuzi, S., Sinicropi-Yao, L., Johnson, D., Chen, Y., Clain, A. et al. (2010). Type of Residual Symptom and Risk of Relapse during the Continuation/Maintenance Phase Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder with the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Fluoxetine. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 260, 145-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00406-009-0031-3

- Zimmerman, M., Chelminski, I., & McDermut, W. (2002). Major Depressive Disorder and Axis I Diagnostic Comorbidity. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63, 187-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v63n0303

NOTES

*Corresponding author.