Advances in Aging Research

Vol.2 No.1(2013), Article ID:27944,6 pages DOI:10.4236/aar.2013.21003

Assessing symptoms profile and correlates of very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOSLP)

![]()

1Department of Psychiatry, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

2Research Centre for Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran; *Corresponding Author: A.javadpour@gmail.com

Received 18 October 2012; revised 20 November 2012; accepted 30 November 2012

Keywords: Late Life Psychosis; VLOSLP; Symptoms; Correlates

ABSTRACT

Objective: While the most common causes of late life psychosis are factors other than primary psychosis, but the nosology and clinical features of late life, primary psychotic is a matter of controversy. The goal of this study was to define some correlates and symptoms profile of very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis among an Iranian elderly population presenting with psychosis. Method: From 201 psychotic elderly patients, 39 (19.4%) subjects with the most possible diagnosis of very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis were selected. Socio demographic characteristics, past psychiatric history, family history of psychiatric problems, personality traits, cognitive status, history of stressful life events, and burden of medical problems assessed and compared between patients and 39 age and sex mathed controls. Results: The mean age of study sample was 76.9 years. Of 39 patients with VLOSLP, 13 (33.3%) were male and 26 (66.6%) were female. In 32 patients (82.05%) some sorts of hallucinatory experiences were detected. Visual hallucinations were the most common types of hallucinations (69.2%) followed by auditory hallucinations (51.35%) and tactile hallucinations (4%). Persecutory delusions (59%); delusions of references (20.5%); and partition delusions (15.4%) were the most common types of delusions. Significant proportion suffered from some sort of sensory deficit like visual or auditory deficits. There was no significant difference in terms of history of traumatic life events, cognitive function; cumulative burden of medical conditions and personality traits between patients and healthy controls (P > 0.05). Conclusions: Female involved two times more than male. The most common types of psychotic symptoms were visual hallucinations and persecutory delusions. Except sex, exploring other demographics, psychological and physical correlates for VLSOLP patients was not conclusive. More controlled studies using neuroimaging and biomarkers are needed in this issue.

1. INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia typically develops in early adulthood. Initial studies conducted by Manfred Bleuler described late onset schizophrenia as being similar to adulthood onset schizophrenia. On the other hand Martin Roth believed that late onset schizophrenia might be a distinct entity of psychotic disorders. Years later, the term late paraphrenia was included in the ninth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-9).

In the past few years, late-onset psychosis has begun to arouse the interest of psychiatrists with research into late-onset schizophrenia being a relatively recent endeavor.

In the United Kingdom, some studies found that late paraphrenia constituted 5% - 10% of admissions to mental hospitals [1-3]. Harris et al. suggested that the proportion of schizophrenia patients whose illness first emerged after the age of 40 was approximately 23.5% and 13% of patients with schizophrenia were reported to have experienced onset in the fifth decade, 7% in the sixed decade and 3% in later decades [4]. The 1-year prevalence rate of schizophrenia in persons 45 to 64 years of age was found to be 0.6% in one investigation, and another study reported a rate of 12.6 per 100,000 per year for new-onset schizophrenia. First admission data for patients over the age of 60, suggest that the annual incidence of schizophrenia-like psychosis increases by 11% with each 5-year increase in age [5].

While the most common causes of late life psychosis are factors other than primary psychosis, but the nosology and clinical features of late life, primary psychotic is a matter of controversy. The use of the terms paraphrenia and late paraphrenia has led to some confusion. To further examine issues surrounding late-onset schizophrenia, such as diagnostic and nomenclature inconsistency and the need for further study, an international late-onset schizophrenia group met to review the literature and reach consensus regarding the previously discussed topics. The group concluded that there was proof to support two late-onset illness classifications and proposed the following: Late-onset (onset after the age of 40 years) schizophrenia and very-late-onset (onset after the age of 60 years) schizophrenia-like psychosis [6-10].

Very late onset schizophrenia distinguished from earlyonset and late-onset schizophrenia by more female involvement; greater prevalence of persecutory and partition delusions; higher rates of visual, tactile and olfactory hallucinations; and accusatory or abusive auditory hallucinations. And lower genetic load; more sensory abnormalities; and absence of negative symptoms or formal thought disorders are other clinical characteristics of late onset schizophrenia replicated in previous studies [6,8,9,11-14]. A study comparing patients with very-lateonset schizophrenia-like psychosis to a sample of chronically ill in-patients with schizophrenia found that the very-late-onset group has stable cognitive and every day functioning compared to the inpatient group [15]. On the other hand, Jeste and colleague revealed that later onset of schizophrenia is associated with somewhat milder cognitive deficits, especially in the areas of learning and abstraction/cognitive flexibility [16].

Premorbid educational and psychosocial functioning is less impaired in late-onset than early-onset schizophrenia. Harris described a typical patient with late-onset schizophrenia as having been married, held a job or been a homemaker, and functional in the community and within the family [17]. Meanwhile a significant proportion of patients with late onset psychosis are reported to have premorbid schizoid or paranoid personality traits that fell short of currently accepted diagnostic criteria for personality disorders [8,9,18,19].

Biopsychosocial risk factors associated with clinical late-onset psychosis include female sex, low socioeconomic status, the experience of immigration, and presence of sensory or perceptual deficits [20].

Recent research by Giblin and colleagues showed that both the late-onset psychosis and late-onset depression groups of the patients, reported significantly higher levels of adverse life events than the control group. The late-onset psychosis group also scored significantly higher on four out of five schema domains (including rejection and disconnection, impaired autonomy and performance, other-directedness and over-vigilance and inhibition). Finally, the late-onset psychosis group had significantly lower overall morale with regards to aging than the control group, likely reflecting higher levels of loneliness and dissatisfaction [20]. Current study presents the results from phase two of a biphasic study in which 222 elderly with late onset psychosis were screened. In phase one symptoms profile and differential diagnosis of late life psychosis were explored. In phase two of study correlates and symptoms profile and correlates of 39 patients diagnosed as very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOSLP) were investigated. The study was approved by the University ethics committee.

2. METHOD

In a cross section simple convenient sampling study 222 elderly with late onset psychosis presenting to outpatient clinics and inpatient units affiliated to Shiraz University of medical Sciences in Iran were screened.

Subjects were included if their psychotic symptoms developed for the first time after 60 years old or more. The subjects were excluded if they were too frail to cooperate or were not agreed to participate. In phase one of study symptoms profile and differential diagnosis of late onset psychosis were explored. The research associate, a senior psychiatry resident (MS) interviewed the subjects using SCID-1 (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV) to confirm the presence of psychotic symptoms and possible differential diagnosis. Furthermore, the subjects put into 6 main categories including: psychosis due to dementia, psychosis due to delirium, psychosis due to mood disorders, psychosis due to general medical conditions, psychosis due to drugs or substances and primary psychotic disorders. According to international late-onset schizophrenia group consensus we used the term VLOSLP for patients whose psychosis had begun after age 60.

In phase two of study demographics, clinical characteristics and correlates of 39 individuals diagnosed as VLOSLP were compared to 39 non psychotic elderly mulched for age and sex. A sociodemographic questionnaire was employed to detect the demographic features including age, sex, living status, immigration and marital status. Two extra questions exploring the past psychiatric history and family history of psychiatric problem among the patients were enclosed as well. To detect some correlates of VLOSLP, personality traits, cognitive status, history of stressful life events, and burden of medical problems were compared to non psychotic controls using NEO-FF Inventory, Cognitive failures questionnaire [21], Paykel questionnaire and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) [22] respectively.

Descriptive statistics were performed on each variable of the data and categorical variables were examined using the fisher exact test, Chi-Square test, Levens test and continuous variables examined using the student’s test.

3. RESULTS

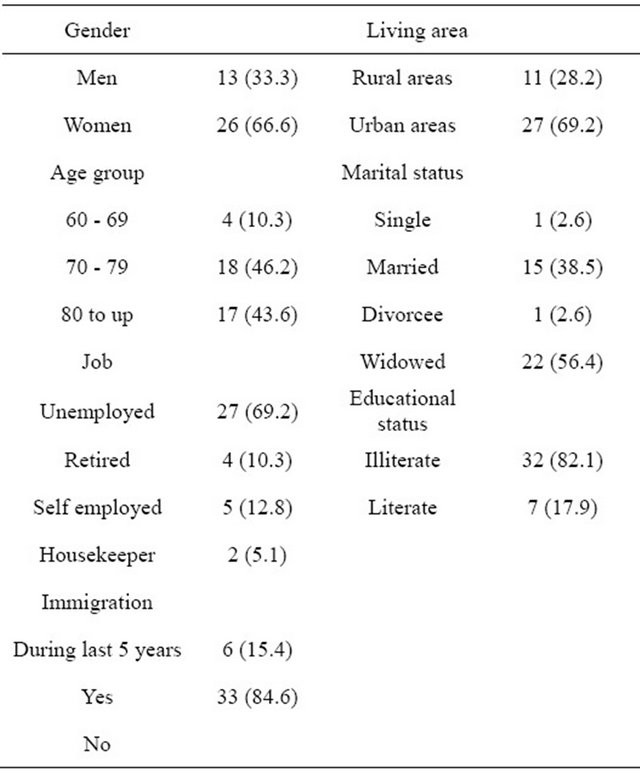

Initial descriptive analyses on demographics revealed that 66.6% (N = 26) of the patients were female and 33.3% (N = 13) were male. The mean age was 77 years old, in terms of living status, 12.8% (N = 5) lived alone and only one subject (2.6%) settled in nursing home. 33 subjects (84.5%) lived with a family member like spouse, children and other close relatives. Further details of sociodemographics of study sample are presented in Table 1.

In further descriptive analyses on some clinical variables, history of psychiatric problems other than psychosis and family history of psychiatric problems were detected in 15.4% (N = 6) and 17.9% (N = 7) respectively.

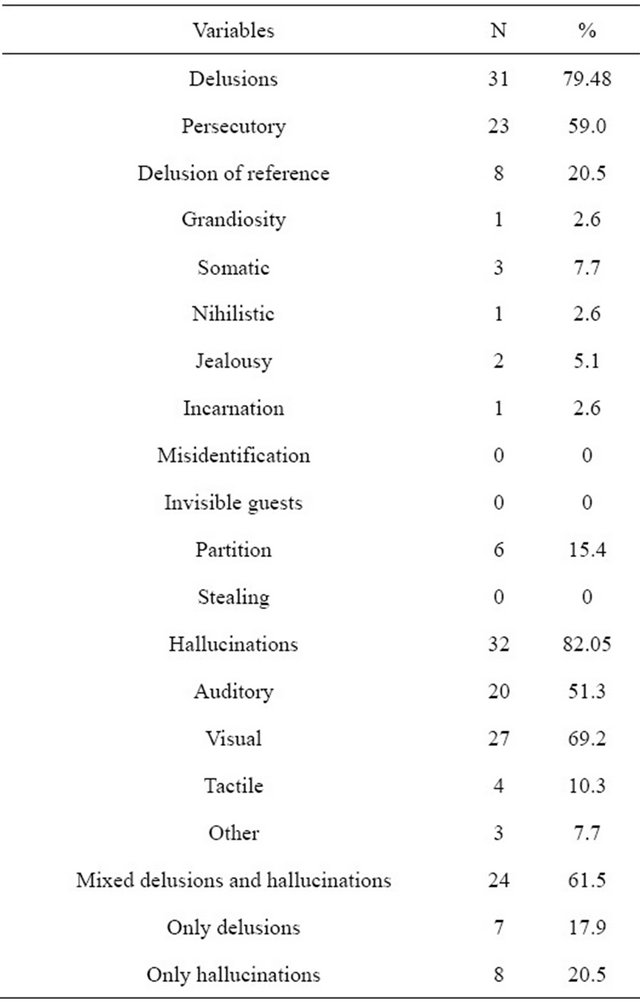

From sample study 61.5% (N = 24) had mixed hallucinations and delusions and 38.5% (N = 15) had either hallucination or delusion. Persecutory delusions (59%), delusions of references (20.5%) and partition delusions (15.4%) were the most common types of delusions. The most common hallucination was visual hallucinations (69.2%) followed by auditory hallucinations (51.3%) and tactile hallucinations (10.3%) (see Table 2). Nobody had been presented with catatonic feature, disorganization and negative symptoms.

The number of patients suffered from at least one sensory deficit was higher than non psychotic controls; 71.79% (N = 28), versus 51.28% (N = 20). The most sensory deficit in psychotic subjects was in visual domain 43.58% (N = 17), followed by auditory deficit: 56.41% (N = 22).

Table 1. Some demographic variables of the patients with very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis n (%).

Table 2. Psychotic symptoms manifested in very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis.

In comparative analysis financial problem was more prevalent among patients than controls (p = 0.035). And there was no significant difference in the prevalence of other domains of Peykel questionnaire items between the patients and control group (p-value > 0.05). In addition to that there was no significant difference in total scores of the cognitive failure test and cumulative burden of medical conditions by using Cognitive Failure questionnaire and CIRS between the patients and control group (with p-value > 0.05). Analyses on neo-E subscale did not revealed any differences in personality traits between both groups as well.

4. DISCUSSION

Late life psychosis could bring about diagnostic challenges to psychiatrist. Results from wave one of current study consistent with earlier studies revealed that psychotic symptoms including hallucinations and delusions can occur in elderly due to various causes. Dementia, depression and delirium have been the most reported causes of psychosis in old age people [23]. It was a matter of interest that primary psychotic disorders like late onset schizophrenia has been less likely explanation for late life psychosis. This information might motivate the psychiatrist to explore causes other than schizophrenia in patients suffering from late onset psychotic symptoms.

Results from phase one of current study investigating the differential diagnosis and symptom profile of psychosis among 222 psychotic elderly were reported in separate paper. Current paper discusses the symptom profile and some correlates of elderly subject diagnosed with very late onset schizophrenia like psychosis (VLOSLP) in phase one of study.

In initial descriptive analyses, the ratio of female to male was about 2 to 1 (66.6% versus 33.3%). This finding is supported by a vast number of empirical investigations which showed a clear predominance of women among the patients with late-onset psychotic symptoms [6,10,17,24,25].

The mean age of this psychotic elderly sample was 77. This result could support findings from earlier studies suggesting increase in incidence of late onset schizophrenia with increasing in age. The 1-year prevalence rate of schizophrenia in persons from 45 to 64 years of age was found to be 0.6% in one investigation, and another study reported a rate of 12.6 per 100,000 per year for new-onset schizophrenia. First admission data for patients over the age of 60, suggest that the annual incidence of schizophrenia-like psychosis increases by 11% with each 5-year increase in age [5].

The most common psychotic symptoms were visual hallucinations (62.2%) followed by persecutory delusions (59%), auditory hallucinations (51.3%), delusions of references (20.5%) and partition delusions (15.4%). It was the matter of interest that the content of these delusions was also replicated by other studies [7,12,26]. Joy Webster and colleagues found that persecutory delusions among elderly mainly centered around the patients family or neighbors, who were accused of trying to steal possessions, break in, or having initiations to harm the patient by various means such as poisoning food. The patients were less likely to present catatonic feature, disorganized behavior and negative symptoms. Findings from current study in line with earlier studies support the idea that thought disorder and negative symptoms are rare in late life psychosis [6,7,9,12,14,16,24].

It is conceivable that aging-associated psychosocial factors such as retirement, financial difficulties, bereavement, deaths of peers, or physical disability may contribute to the precipitation of the symptoms of schizophrenia in later life. The role of these factors has not, however, been studied systematically in late-onset patients. In current study more financial problems detected in patients with late onset schizophrenia than controls (p = 0.035). Other psychosocial factors such as migration, income, living status and family pattern were not significantly different between patients and controls. While social isolation is considered as a contributing factor for late life psychosis in literature, in this sample a small proportion (13%) lived alone. The explanation is that in eastern cultures like Iran the senior parents live with and supported by their children and other close relatives. Nevertheless, 56.4% of patients were widowed or widower. Of course, some sociocultural issues in this regard should be considered. Immigration was another demographic factor that we considered in the study and found that most of the patients had no history of immigration to another place (cities or villages) during the last 5 years.

Research investigating the familial distribution of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders in elderly with late life psychosis is not conclusive. This might be due to methodological problems. Nevertheless current evidence shows lower risk for relatives of late onset schizophrenia than relatives of early onset schizophrenia [9,27]. In current study 17.9% (N = 7) of subjected reported presence of psychiatry problem in one of their 1st proband. These findings support the results of some investigations reported low rate of family history for late life psychosis. [7,14].

The role of sensory deficit in very late onset schizophrenia has been stressed in many studies [7,25,28]. In current sample of VLOSLP a noticeable number (71.8%) of the patients had some degrees of visual or hearing deficits. These data support the possible role of sensory deficit in late life psychosis. Meanwhile there was no significant difference between controls and patients (chi = 0.99, df = 2). Clinical observations have shown that improved hearing or vision have led to decreased paranoid delusions and hallucinations in older patients. Thus, a clinical assessment of vision and hearing is needed.

A significant proportion of patients with late onset psychosis are reported to have premorbid schizoid or paranoid personality traits that fell short of currently accepted diagnostic criteria for personality disorders [9, 16,18,19]. Although premorbid personality traits like schizoid or paranoid traits have been reported by some authors, in our study there was no significant difference between controls and patients in regard to personality traits.

The other correlate which was investigated in present study was cognitive function of subjects with VLOSLP. Comparative analyses did not replicate findings from earlier studies showed some degree of cognitive deficits in old people with schizophrenia. This inconsistency might be due to cognitive measure used in our study. In previous studies mild cognitive deficits in area of cognitive flexibilities, learning and executive function have been reported [23,25]. The cumulative burden of medical condition also was not different between patients and healthy controls.

The most important limitation of this study was the small number of the patients due to low prevalence rate of disorder and consequently, the low number of the control people, which makes limitations in generalizing the results for the factors such as cognitive deficits, medical problems, life stressors and personality traits.

5. CONCLUSION

According to this study, we concluded that the very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis is most possibly seen, in the elderly widowed woman who is unemployed and not educated and is living in the city with her children and under financial support of them, without history of immigration during the last 5 year. Significant proportion suffered from some sort of sensory deficit like visual or auditory deficits. The most psychotic symptoms were visual hallucinations followed by auditory hallucination, persecutory delusion and partition delusions. Catatonia, disorganization and negative symptoms were less common. Very late onset schizophrenia is still an illness of controversy. Both psychological and biological process might be implicated. Possible of correlates should be considered. More systematized studies using biomarkers and neuroimaging are needed.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Blessed, G. and Wilson, D. (1982) The contemporary natural history of mental disorder in old age. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 141, 59-67. doi:10.1192/bjp.141.1.59

- Chrisie, A. (1982) Changing patterns in mental illness in the elderly. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 154- 159. doi:10.1192/bjp.140.2.154

- Henderson, A. and Kay, D. (1997) The epidemiology of functional psychoses of late onset. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 247, 176-189. doi:10.1007/BF02900214

- Harris, M.J. and Jeste, D.V. (1988) Late-onset schizophrenia: An overview. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 14, 39-45. doi:10.1093/schbul/14.1.39

- Van, O.S., Howard, R., Takei, N. and Murray, R.M. (1995) Increasing age is a risk factor for psychosis in the elderly. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 30, 161- 164. doi:10.1007/BF00790654

- Almedia, O., Howard, R., Levy, R. and David, A. (1995) Psychotic states arising in late life (late paraphrenia): psychpathology and nosology. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 205-214. doi:10.1192/bjp.166.2.205

- Hassett, A., Ames, D. and Chiu, E. (2005) Psychosis in elderly. Taylor & Francis, London.

- Jeste, D.V., Harris, M.J., Krull, A., Kuck, J., McAdmas, L.A. and Heaton, R. (1995) Clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of patients with late-onset schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 722-730.

- Pearlson, G.D., Kreger, L., Rabins, P.V., Cohen, B., Wirth, J.B., Schlaepfer, T.B., et al. (1989) A chart review study of late-onset and early-onset schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 1568-1574.

- Rabins, P.V. and Pauker, S.J.T. (1984) Can schizophrenia begin after age 44? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 25, 290- 293. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(84)90060-9

- Hebert, M.E. and Jacobson, S. (1967) Late paraphrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 113, 461-467. doi:10.1192/bjp.113.498.461

- Howard, R., Almedia, O.P. and Levy, R. (1994) Phenomenology, demography and diagnosis in late paraphrenia. Psychological Medicine, 24, 397-410. doi:10.1017/S0033291700027379

- Howard, R., Castle, D., Brien, J.O., Almedia, O. and Levy, R. (1992) Permeable walls, floors, ceilings and doors: Partition delusions in late paraphrenia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 7, 719-724. doi:10.1002/gps.930071006

- Howard, R., Castle, D., Wessely, S. and Murray, R.M. (1993) A comparative study of 470 cases of early-and lateonset schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 352-357. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.3.352

- Mazeh, D., Zemishlani, C., Aizenberg, D. and Barak, Y. (2005) Patients with very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: A follow-up study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13, 417-419.

- Jeste, D., Harris, M., Krull, A., Kuck, J., Adams, L.M. and Healton, R. (1995) Clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of patients with late-onset schizophrenia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 152, 722- 730.

- Harris, M.J. (1997) Psychosis in late life. Spotting newonset disorders in your elderly patients. Postgraduate Medicine, 102, 139-142.

- Kay, D.W.K., Cooper, A.F., Garside, R.F. and Roth, M. (1976) The differentiation of paranoid from affective psychoses by patients premorbid characteristics. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 129, 207-215. doi:10.1192/bjp.129.3.207

- Kay, D.W.K. and Roth, M. (1961) Environmental and hereditary factors in the schizophrenias of old age (late paraphrenia) and their bearing on the general problem of causation in schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Science, 107, 649-686.

- Giblin, S., Clare, L. and Livingston, G. (2004) Psychosocial correlates of late-onset psychosis: Life experiences, cognitive schemas, and attitudes to aging. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19, 611-623. doi:10.1002/gps.1129

- Wallace, J.C., Kass, S.J. and Stanny, C.J. (2002) The cognitive failure questionnare revisited: Dimension and correlates. The Journal of General Psychology, 129, 238-256. doi:10.1080/00221300209602098

- Hudon, C., Fortin, M. and Soubhi, H. (2007) Abbreviated guidelines for scoring the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) in family practice. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 212.e1-212.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.021

- Holroyd, S. and Laurie, S. (1999) Correlates of psychotic symptoms among elderly outpatients. International Journal of Psychiatry, 14, 379-384. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199905)14:5<379::AID-GPS924>3.0.CO;2-7

- Sadock, B., Sadock, V. and Ruiz, P. (2009) Comprehensive text book of psychiatry. Lippincott Williams and Willkins, New York.

- Howard, R., Rabins, P., Seeman, M. and Jeste, D. (2000) The international late-onset schizophrenia group, lateonset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenialike psychosis: An international consensus. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 172-178. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.172

- Webster, J. and Grossberg, G.T. (1998) Late-life onset of psychotic symptoms. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 6, 196-202.

- Howard, R., Graham, C. and Sham, P. (1997) A controlled family study of late-onset non-affective psychosis (late paraphrenia). The British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 511- 514. doi:10.1192/bjp.170.6.511

- Knouzam, H., Battista, M., Emes, R. and Ahless, S. (2005) Psychosis in late life: Evaluation and management of disorders seen in primary care. Geriatrics, 60, 26-33.