Advances in Linear Algebra & Matrix Theory

Vol.07 No.01(2017), Article ID:75195,11 pages

10.4236/alamt.2017.71003

A New Type of Restarted Krylov Methods

Achiya Dax

Hydrological Service, Jerusalem, Israel

Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: March 6, 2017; Accepted: March 28, 2017; Published: March 31, 2017

ABSTRACT

In this paper we present a new type of Restarted Krylov methods for calculating peripheral eigenvalues of symmetric matrices. The new framework avoids the Lanczos tridiagonalization process, and the use of polynomial filtering. This simplifies the restarting mechanism and allows the introduction of several modifications. Convergence is assured by a monotonicity property that pushes the eigenvalues toward their limits. The Krylov matrices that we use lead to fast rate of convergence. Numerical experiments illustrate the usefulness of the proposed approach.

Keywords:

Restarted Krylov Methods, Exterior Eigenvalues, Symmetric Matrices, Monotonicity, Starting Vectors

1. Introduction

In this paper we present a new type of Restarted Krylov methods. Given a symmetric matrix , the method is aimed at calculating a cluster of k exterior eigenvalues of G. Other names for such eigenvalues are “peripheral eigenvalues” and “extreme eigenvalues”. The method is best suited for handling large sparse matrices in which a matrix-vector product needs only 0(n) flops. Another underlying assumption is that k2 is considerably smaller than n. The need for computing a few extreme eigenvalues of such a matrix arises in many applications, see [1] - [21] .

, the method is aimed at calculating a cluster of k exterior eigenvalues of G. Other names for such eigenvalues are “peripheral eigenvalues” and “extreme eigenvalues”. The method is best suited for handling large sparse matrices in which a matrix-vector product needs only 0(n) flops. Another underlying assumption is that k2 is considerably smaller than n. The need for computing a few extreme eigenvalues of such a matrix arises in many applications, see [1] - [21] .

The traditional restarted Krylov methods are classified into three types of restarts: “Explicit restart” [1] , [9] , [11] , “Implicit restart” [1] , [3] , [12] , and “Thick restart” [18] , [19] . See also [7] , [11] , [14] , [16] . When solving symmetric eigenvalue problems all these methods are carried out by repeated use of the Lanczos tridiagonalization process, and the use of polynomial filtering to determine the related starting vectors. This way each iteration generates a new tridiagonal matrix and computes its eigensystem. The method proposed in this paper is based on a different framework, one that avoids these techniques. The basic iteration of the new method have recently been presented by this author in [4] . The driving force is a monotonicity property that pushes the estimated eigenvalues toward their limits. The rate of convergence depends on the quality of the Krylov matrix that we use. In this paper we introduce a modified scheme for generating the Krylov matrix. This leads to dramatic improvement in the rate of convergence, and turns the method into a powerful tool.

Let the eigenvalues of G be ordered to satisfy

(1.1)

(1.1)

or

(1.2)

(1.2)

Then the new algorithm is built to compute one of the following four types of target clusters that contain k extreme eigenvalues.

A dominant cluster

(1.3)

(1.3)

A right-side cluster

(1.4)

(1.4)

A left-side cluster

(1.5)

(1.5)

A two-sides cluster is a union of a right-side cluster and a left-side cluster. For example,  or

or .

.

Note that although the above definitions refer to clusters of eigenvalues, the algorithm is carried out by computing the corresponding k eigenvectors of G. The subspace that is spanned by these eigenvectors is called the target space.

The basic iteration

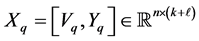

The qth iteration,  , is composed of the following five steps. The first step starts with a matrix

, is composed of the following five steps. The first step starts with a matrix  that contains “old” information on the target space, a matrix

that contains “old” information on the target space, a matrix  that contains “new” information, and a matrix

that contains “new” information, and a matrix  that includes all the known information. The matrix

that includes all the known information. The matrix  has

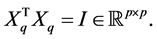

has  orthonormal columns. That is

orthonormal columns. That is

(Typical values for  lie between k to 2k.)

lie between k to 2k.)

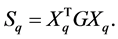

Step 1: Eigenvalues extraction. First compute the Rayleigh quotient matrix

Then compute k eigenpairs of  which correspond to the target cluster. (For example, if it is desired to compute a right-side cluster of G, then compute a right-side cluster of

which correspond to the target cluster. (For example, if it is desired to compute a right-side cluster of G, then compute a right-side cluster of

which is used to compute the related matrix of Ritz vectors,

Note that both

Step 2: Collecting new information. Compute a Krylov matrix

Step 3: Orthogonalize the columns of

Step 4: Build an orthonormal basis of Range (Zq). Compute a matrix,

whose columns form an orthonormal basis of Range (Zq). This can be done by a QR factorization of

Step 5: Define

which ensures that

At this point we are not concerned with efficiency issues, and the above description is mainly aimed to clarify the purpose of each step. Hence there might be better ways to carry out the basic iteration.

The plan of the paper is as follows. The monotonicity property that motivates the new method is established in the next section. Let

2. The Monotonicity Property

The monotonicity property is an important feature of the new iteration, whose proof is given in [4] . Yet, in order to make this paper self-contained, we provide the proof. We start by stating two well-known interlacing theorems, e.g., [8] , [10] and [20] .

Theorem 1 (Cauchy interlace theorem) Let

Let the symmetric matrix

denote the eigenvalues of H. Then

and

In particular, for

Corollary 2 (Poincarà separation theorem) Let the matrix

Let us turn now to consider the qth iteration of the new method,

and let the eigenvalues of the matrix

be denoted as

Then the Ritz values which are computed at Step 1 are

and these values are the eigenvalues of the matrix

Similarly,

are the eigenvalues of the matrix

Therefore, since the columns of

On the other hand from Corollary 2 we obtain that

Hence by combining these relations we see that

for

The treatment of a left-side cluster is done in a similar way. Assume that the algorithm is aimed at computing a cluster of k left-side eigenvalues of G,

Then similar arguments show that

for

Recall that a two-sides cluster is the union of a right-side cluster and a left- side one. In this case the eigenvalues of

3. The Basic Krylov Matrix

The basic Krylov information matrix has the form

where the sequence

where

The proof of the Kaniel-Paige-Saad bounds relies on the properties of Chebyshev polynomials, while the building of these polynomials is carried out by using a three term recurrence relation, e.g. [10] , [11] . This observation suggests that in order to achieve these bounds the algorithm for generating our Krylov sequence should use a “similar” three term recurrence relation. Indeed this feature is one of the reasons that make the Lanczos recurrence so successful, see ( [11] , p. 138). Below we describe an alternative three term recurrence relation, which is based on the Modified Gram-Schmidt (MGS) orthogonaliza- tion process.

Let

The preparations part

a) Compute the starting vector:

b) Compute

Orthogonalize

Normalize

c) Compute

Orthogonalize

Orthogonalize

Normalize

The iterative part

For

a) Set

b) Orthogonalize

c) Orthogonalize

d) Reorthogonalization: For

e) Normalize

The reorthogonalization step is aimed to ensure that the numerical rank of

4. The Power-Krylov Matrix

Assume for a moment that the algorithm is aimed at calculating a cluster of k dominant eigenvalues. Then the Kaniel-Paige-Saad bounds suggest that slow rate of convergence is expected when these eigenvalues are poorly separated from the other eigenvalues. Indeed, this difficulty is seen in Table 2, when the basic Krylov matrix is applied on problems like “Very slow geometric” and “Dense equispaced”. Let

The implementation of this idea is carried out by introducing a small modification in the construction of

(In our experiments

The usefulness of the Power-Krylov approach depends on two factors: The cost of a matrix-vector product and the distribution of the eigenvalues. As noted above, it is expected to reduce the number of iterations when the k largest eigenvalues of G are poorly separated from the rest of the spectrum. See Table 3. Another advantage of this approach is that

5. The Initial Orthonormal Matrix

To start the algorithm we need to supply an “initial” orthonormal matrix,

be generated as in Section 3, using some arbitrary starting vector

In our experiments

6. Numerical Experiments

In this section we describe some experiments with the proposed methods. The test matrices have the form

where

Recall that in Krylov methods there is no loss of generality in experimenting with diagonal matrices, e.g., ( [6] , p. 367). The diagonal matrices that we have used are displayed in Table 1. All the experiments were carried out with n = 12,000. The experiments that we have done are aimed at computing a cluster of k dominant eigenvalues. The figures in Table 2 and Table 3 provide the number of iterations that were needed to satisfy the inequality

Thus, for example, from Table 2 we see that only 4 iterations are needed when the algorithm computes

The ability of the basic Krylov matrix to achieve accurate computation of the eigenvalues is illustrated in Table 2. We see that often the algorithm terminates within a remarkably small number of iterations. Observe that the method is highly successful in handling low-rank matrices, matrices which are nearly low-

Table 1. Types of test matrices,

rank, like “Harmonic” or “Geometric”, and matrices with gap in the spectrum. In such matrices the initial orthonormal matrix,

As expected, a slower rate of convergence occurs when the dominant eigen- alues that we seek are poorly separated from the other eigenvalues. This situation is demonstrated in matrices like “Dense equispaced” or “Very slow geometric”. Yet, as Table 3 shows, in such cases the Power-Krylov method leads to considerable reduction in the number of iterations.

7. Concluding Remarks

The new type of Restarted Krylov methods avoids the use of Lanczos algorithm. This simplifies the basic iteration, and clarifies the main ideas behind the

Table 2. Computing k dominant eigenvalues with the basic Krylov matrix,

Table 3. Computing k dominant eigenvalues with the Power-Krylov matrix,

method. The driving force that ensures convergence is the monotonicity proper- ty, which is easily concluded from the Cauchy-Poincaré interlacing theorems. The proof indicates too important points. First, there is a lot of freedom in choosing the information matrix, and that monotonicity is guaranteed as long as we achieve proper orthogonalizations. Second, the rate of convergence depends on the “quality” of the information matrix. This raises the question of how to define this matrix. Since the algorithm is aimed at computing a cluster of exterior eigenvalues, a Krylov information matrix is a good choice. In [4] we have tested the classical Krylov matrix where

Indeed, the results of our experiments are quite encouraging. We see that the algorithm requires a remarkably small number of iterations. In particular, it efficiently handles various kinds of low-rank matrices. In these matrices the initial orthonormal matrix is often sufficient for accurate computation of the desired eigenpairs. The algorithm is also successful in computing eigenvalues of “difficult” matrices like “Dense equispaced” or “Very slow geometric decay”.

Cite this paper

Dax, A. (2017) A New Type of Restarted Krylov Methods. Advances in Linear Algebra & Matrix Theory, 7, 18-28. https://doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2017.71003

References

- 1. Bai, A., Demmel, J., Dongarra, J., Ruhe, A. and van der Vorst, H. (1999) Templates for the Solution of Algebraic Eigenvalue Problems: A Practical Guide. SIAM, Philadelphia, PA.

- 2. Bjorck, A. (1996) Numerical Methods for Least-Squares Problems. SIAM, Philadelphia.

https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611971484 - 3. Calvetti, D., Reichel, L. and Sorenson, D.C. (1994) An Implicitly Restarted Lanczos Method for Large Symmetric Eigenvalue Problems. Electronic Transactions on Numerical Analysis, 2, 1-21.

- 4. Dax, A. (2015) A Subspace Iteration for Calculating a Cluster of Exterior Eigenvalues. Advances in Linear Algebra and Matrix Theory, 5, 76-89.

https://doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2015.53008 - 5. Dax, A. (2016) The Numerical Rank of Krylov Matrices. In: Linear Algebra and Its Applications.

- 6. Demmel, J.W. (1997) Applied Numerical Linear Algebra. SIAM, Philadelphia.

https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611971446 - 7. G.H. Golub and C.F. Van Loan (2013) Matrix Computations. 4th Edition, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- 8. Horn, R.A. and Johnson, C.R. (1985) Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511810817 - 9. Morgan, R.B. (1996) On Restarting the Arnoldi Method for Large Non-Symmetric Eigenvalues Problems. Mathematics of Computation, 65, 1213-1230.

- 10. Parlett, B.N. (1980) The Symmetric Eigenvalue Problem. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- 11. Saad, Y. (2011) Numerical Methods for Large Eigenvalue Problems: Revised Edition. SIAM, Philadelphia.

https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611970739 - 12. Sorensen, D.C. (1992) Implicit Application of Polynomial Filters in a k-Step Arnoldi Method. SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications, 13, 357-385.

https://doi.org/10.1137/0613025 - 13. Stewart, G.W. (1998) Matrix Algorithms, Vol. I: Basic Decompositions. SIAM, Philadelphia.

- 14. Stewart, G.W. (2001) Matrix Algorithms, Vol. II: Eigensystems. SIAM, Philadelphia.

- 15. Trefethen, L.N. and Bau III, D. (1997) Numerical Linear Algebra. SIAM, Philadelphia.

- 16. Watkins, D.S. (2007) The Matrix Eigenvalue Problem: GR and Krylov Subspace Methods. SIAM, Philadelphia.

https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9780898717808 - 17. Wilkinson, J.H. (1965) The Algebraic Eigenvalue Problem. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- 18. Wu, K. and Simon, H. (2000) Thick-Restarted Lanczos Method for Large Symmetric Eigenvalue Problems. SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications, 22, 602-616.

https://doi.org/10.1137/S0895479898334605 - 19. Yamazaki, I., Bai, Z., Simon, H., Wang, L. and Wu, K. (2010) Adaptive Projection Subspace Dimension for the Thick-Restart Lanczos Method. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software, 37, Article No. 27.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1824801.1824805 - 20. Zhang, F. (1999) Matrix Theory: Basic Results and Techniques. Springer-Verlag, New York.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-5797-2 - 21. Zhou, Y. and Saad, Y. (2008) Block Krylov-Schur Method for Large Symmetric Eigenvalue Problems. Numerical Algorithms, 47, 341-359.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11075-008-9192-9