American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

Vol.05 No.09(2015), Article ID:59754,10 pages

10.4236/ajibm.2015.59059

Analysis of Psychological Factors That Influence Preference for Luxury Food and Car Brands Targeting Japanese People

Kazutoshi Fujiwara*, Shin’ya Nagasawa

Graduate School of Commerce, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan

Email: *k-fujiwara@toki.waseda.jp, nagasawa@waseda.jp

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 19 August 2015; accepted 18 September 2015; published 21 September 2015

ABSTRACT

This study examines the strong preference among Japanese people for luxury brands and makes a comparative analysis of the psychological factors that influence the development of purchase intentions and how they differ between the food and car luxury brands. An empirical analysis was performed by using psychological factors that influence the preference for luxury brands, which Sugimoto [1] demonstrated in a study on Japanese people. The results suggested the following: 1) Differentiation from Others is an important factor in developing purchase intentions for both food and car luxury brands and is a particularly important factor for cars; 2) Conformity to Group Norms is not an important factor in developing purchase intentions for both food and car luxury brands in which consumers continue to feel a sense of rarity; 3) Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance is an important factor in developing purchase intentions for both food and car luxury brands; 4) Quality Evaluation is an important factor in developing purchase intentions for food luxury brands only.

Keywords:

Luxury Brand, Japanese People, Psychological Factor, Food, Car

1. Introduction

Fujiwara and Nagasawa [2] examined the growing success of GODIVA, the Belgian-born luxury chocolate brand, in Japan [3] , and suggested the possibility that the preference for luxury brands among Japanese people is not limited to fashion and leather products, which were the subjects of many of the previous studies on luxury brands. Then, a comparative empirical study was performed on FERRARI, which belongs to the brand category of cars (a category with very different characteristics from food) by using the concept of customer experience, which was proposed by Schmitt [4] . The results showed that luxury brand strategies can be applied to the category of food, just as they can be applied to cars.

For this study, which aims to expand on the results of Fujiwara and Nagasawa [2] , a comparative analysis will be performed on the differences among the psychological factors that constitute purchase intentions by using the psychological factors that influence the preference for luxury brands, which Sugimoto [1] presented. GODIVA and FERRARI, will be subject brands for this study once again. In addition to these two brands, TORAYA (a well-known Japanese luxury confectionary brand) and DOM PERIGNON from the category of food and ROLLS-ROYCE and PORSCHE from the category of cars have been chosen as subject brands to perform a comparative analyses within the same product categories.

2. Previous Studies

2.1. Studies on Luxury Consumer Behavior

There are many previous studies on luxury consumer behaviour shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of research used to define the values of prestige.

Ever since Rae [5] and Veblen [6] pointed to conspicuousness as a purchase motive for luxury brands, numerous studies on luxury consumer behavior have been carried out. Leibenstein [7] called the effect in which an increase in the number of consumers boosts consumption the Bandwagon Effect, the effect in which an increase in the number consumers causes consumption to decline the Snob Effect, and the effect in which consumer satisfaction increases as the price of the brand increases the Veblen Effect, naming it after Veblen. Vigneron and Johnson [8] pointed out that in addition to the social factors of Bandwagon, Snob, and Veblen, which Leibenstein [7] proposed, personal matters such as hedonism and perfectionism also exist. They define hedonists as consumers who develop purchase intentions by being drawn to the beauty of products, and perfectionists as consumers who develop purchase intentions by being drawn to elements such as the advanced technique used or whether the product was handmade. Furthermore, Vigneron and Johnson [8] called the perceived values which these five types of consumers possess, namely Veblen, Snob, Bandwagon, Hedonism, and Perfectionism, in sequential order, conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality. They demonstrated that most of the perceived values presented in previous studies fall under these categories. The results of the studies carried out by Sugimoto [1] , Dubois et al. [9] , Kumagai [10] , and Miura [11] , combined with Vigneron and Johnson [8] ’s categories, are shown in Table 1.

2.2. Studies on Japanese Luxury Consumer Behavior

Miura [12] , whose study is included in Table 1, compared Japanese people with American, French, and Chinese people, and the results showed that the distinct national character of Japanese people, who show a low level of normative consciousness and a strong preference for conforming to group norms, is a factor in their preference for luxury brands. Since it has become clear that national character has an effect on purchase intentions, in order to examine the psychological factors which influence the preference for luxury brands among Japanese people, it would be ideal to carry out the study with a focus on data gathered from Japanese subjects. Of the studies shown in Table 1, the only empirical studies on Japanese people were: Miura [11] , Sugimoto [1] , and Kumagai [10] . Among these, Sugimoto [1] provides the most detailed evidence on psychological factors which influence preference for luxury brands among Japanese people. For the study, questionnaires with 33 items targeting Japanese people were conducted and a factor analysis was performed. The results demonstrated that the seven psychological factors, which are shown in Figure 1, lead to the development of the preference for luxury brands among Japanese people [21] . For this study, questionnaires will be created by referring to Sugimoto [1] , and an empirical analysis will be performed.

3. Empirical Analysis

3.1. Quantitative Definition of Luxury

Although the term luxury has been defined by many researchers in the past, there is no single definition. Therefore, coming up with a quantitative definition for the term is difficult, as many of the definitions are based on subjective views [22] . In light of this, Kapfere [23] presents a democratic approach to defining the term: asking potential customers what the word luxury means to them. To follow this approach, the participants of the questionnaires for this study will be asked about potential luxury brands and will be asked the question “Do you

Figure 1. Psychological factors which influence the preference for luxury brands among Japanese people [21] .

think X is a luxury brand?” Each question is to be answered on a scale of 1 (I strongly disagree) to 7 (I strongly agree). Furthermore, similar questions will be asked about mass brands that hold the highest market share in Japan within the same product category1 [24] -[26] . The differences in the average scores for the answers will be compared by using a t-test. If potential luxury brands show a statistically significant higher mean value compared with mass brands, those brands would represent the definition of luxury for this study.

The results of the comparisons are shown in Table 2. All potential luxury brands which were examined in this study showed a statistically significant mean value compared with mass brands (t(499) = 39.597, p < 0.0001). Therefore, all six brands will be considered luxury brands when examining them for this study.

3.2. Assumptions about the Subject Luxury Food Brands

According to GODIVA, roughly 75% of their products were purchased as gifts [27] . It is believed that this is often the case not only for GODIVA, but for luxury foods as a whole because of the characteristics of the product category (e.g. affordability). To explore this, the 500 participants of the questionnaires presented later in this paper (see Table 5) were asked the total amount of money they have spent on each brand over the past ten years according to the purpose of their purchases.

The results are shown in Figure 2, and the percentage of gift purchases were high for all three subject brands: GODIVA (86.6%), TORAYA (90.5%), and DOM PERIGNON (73.9%). Based on these results, the decision was made to conduct all research and observations on luxury foods for this study under the assumption that they are gift purchases.

3.3. Methods

The results of Sugimoto [1] [22] ’s study presented seven factors (see Figure 1) which carry out the functions of Self-expression and Optimization of the Information Gathering Process. Self-expression consists of Differentiation from Others and Conformity to Group Norms, and Optimization of the Information Gathering Process consists of Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance and Quality Evaluation. However, according to Figure 1, Avoiding

Table 2. Perception of products as luxury brands (t-test).

Note: Significance level *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2. Total amount breakdown of purchases by purpose for 3 luxury food brands of this study (n = 500).

Cognitive Dissonance is also a factor that influences the development of Conformity to Group Norms. As a result, there appears to be an inconsistency with respect to the definitions of the terms. To resolve this inconsistency, Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance and Quality Evaluation are treated as separate items in this study, and the analyses will be performed under the assumption that factors influencing the development of Conformity to Group Norms consist of only Popularity and Avoiding Deviation from the Norm.

In other words, this study examines how the four psychological factors, namely Differentiation from Others (which consists of Self-expression, Sense of Superiority, and Anticonformity), Conformity to Group Norms (which consists of Popularity and Avoiding Deviation from the Norm), Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance, and Quality Evaluation influence purchase intentions for luxury brands.

The questionnaires for this study (see Table 3) were created based on the questionnaire form used by Sugimoto [1] . “X” in Table 3 is to be replaced with the name of the subject brand being examined, and the questions are to be answered on a scale of 1 (I strongly disagree) to 7 (I strongly agree). The scores for the answers for each psychological factor will be added up and assigned synthetic variables. These will be the explanatory variables. In addition, questions will be asked on the purchase intentions (hereinafter referred to as PI) of each subject brand on a scale of 1 to 7. These will be the explained variables. Next, a multiple regression analysis will be performed, which will reveal the psychological factors that influence purchase intentions.

Table 3. Questionnaire items used for this study.

Note: Created by writers of this paper by referring to Sugimoto [1] .

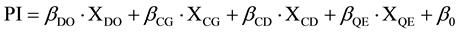

3.4. Constructing a Hypothesis and the Multiple Regression Model Equation

The sum of the scores for the questionnaire answers on the four psychological factors presented by Sugimoto [1] [21] , namely Differentiation from Others, Conformity to Group Norms, Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance, and Quality Evaluation, will be assigned synthetic variables: XDO, XCG, XCD, and XQE in order. These will be the explanatory variables. Next, βDO, βCG, βCD, and βQE in order will be assigned as standard partial regression coefficients for the explanatory variables. Assuming that β0 is the constant term, the following multiple regression model Equation (1) will result. Hypothesis will be constructed under the assumption that if a standard partial regression coefficient shows a significant positive correlation, it will mean that each psychological factor has a direct positive effect on purchase intention for the subject brands.

(1)

(1)

3.4.1. Hypotheses on Differentiation from Others

When purchasing gifts, which is the assumed setting in the questionnaires on luxury food brands used in this study, the perception of others (the people who will receive the gift(s)) will influence purchase intentions. The perception of others (how they will be perceived by people passing by when they drive the car) will also influence purchase intentions for cars. In this way, perception of others, a social factor that influences purchase intentions for luxury brands, is a factor that has a correlation with conspicuousness (the need for differentiation), which Rae [5] and Veblen [6] presented.

Fukuda [28] explains that social needs such as the need for differentiation and conformity to group norms develop as part of the functions of the limbic system and cerebral cortex and therefore are mechanisms that are necessary in beating their competition within groups. Therefore, since such needs are part of the basic functions of the human body, it is believed that the effect of differentiation on the preference for luxury brands is not something that is weeded out along with the passage of time and is a factor that can be applied today, much like what Rae [5] and Veblen [6] pointed out over a century ago. Thus, the following hypotheses (Hypotheses 1 and 2) should hold true.

Hypothesis 1. Differentiation from Others will have a direct positive effect on purchase intention for subject luxury brands in the category of food.

Hypothesis 2. Differentiation from Others will have a direct positive effect on purchase intention for subject luxury brands in the category of cars.

3.4.2. Hypotheses on Conformity to Group Norms

Conformity to Group Norms refers to behavior in which consumers, when deciding on what products to buy, choose brands that are popular among their friends and acquaintances. The group that influences the consumer’s value judgment and decision making is called a reference group2 [29] . Reference groups may include not only membership groups (e.g. family, school, company they work for), but also non-membership groups (groups they want to become a member of) as well [29] . Kotler et al. [30] points to the following three reference group factors as having a significant effect on people: (1) The reference group inspires a new lifestyle for the individual. (2) The reference group has an influence on the individual’s attitude or self-concept. (3) The reference group pressures the individual into choosing the same products as everyone else when choosing a product or brand.

First, how the aforementioned three reference group factors presented by Kotler et al. [30] influence purchase intentions for each subject brand in the food category will be examined. It was determined that the effect of reference group factors (1) and (2) on the food category would be minimal. This is because it was determined that the two factors show up in high-involvement products. It is believed that reference group factor 3 will especially influence purchase intentions for the food category. Choosing standard brands to conform to everyone else when purchasing gifts would be an example of this. It was inferred that, among the subject brands, GODIVA and TORAYA are considered as standard brands for gift purchases and that DOM PERIGNON does not fall under this category. Thus, Hypothesis 3 should hold true.

Next, the three subject brands in the category of cars will be examined. For cars, there is a possibility that reference group factors (1), (2) and (3) all influence purchase intentions. However, it is hard to imagine that the three subject brands in the category of cars are actively engaged promotional activities in Japan that would make consumers conscious of reference groups. In addition, given the extremely limited number of luxury car owners, it is expected that opportunities for being influenced by reference groups (e.g. people who are driving the same cars) will also be limited. Furthermore, generally speaking, luxury car brands have earned tremendous customer loyalty from a limited number of people. For this reason, it would be hard to imagine a situation in which a car brand has earned the loyalty of many people that the consumer knows (membership group) or one in which many people that the consumer knows have purchased the brand. Based on these reasons, it was determined that reference groups will have a minimal effect on purchase intentions for car brands. Thus, Hypothesis 4 should hold true.

Hypothesis 3. Among the subject luxury brands in the category of food, Conformity to Group Norms will have a direct positive effect on purchase intention for GODIVA and TORAYA only.

Hypothesis 4. Conformity to Group Norms will not have a direct effect on purchase intention for subject luxury brands in the category of cars.

3.4.3. Hypotheses on Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance theory was proposed by Festinger [31] and has been used in numerous studies on consumer behavior since then. This theory points out that if a person has two conflicting thoughts, it will cause a psychological burden. For instance, if a consumer discovers a defect with a product after making the purchase and if they discover the benefits of another product, which they didn’t choose, it would cause a psychological burden. Cognitive dissonance refers to that psychological burden. If a consumer experiences cognitive dissonance, they will make an attempt to maintain cognitive consistency by altering their cognition. To do this, they might gather information on the benefits of the product they purchased or the disadvantages of the product they didn’t purchase, in an effort to reduce their dissonance [21] .

Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance is believed to be an important psychological factor in the development of purchase intentions for luxury brands. This is because it is believed that the consumer’s belief that “it has to be this brand,” which is the ideal belief that a brand would want the consumer to have, would be reflected in the results, a notion that is consistent with the definition of cognitive dissonance. On the other hand, if a customer does not experience cognitive dissonance, it will mean that the consumer can experience a similar level of satisfaction from another brand. Such a product cannot be considered a true luxury brand.

Since the luxury food brands examined in this study are assumed to be purchased as gifts, it is expected that the products will be used in important settings in which an emphasis is placed on appearance. Therefore, it is believed that if a consumer experiences cognitive dissonance due to the inability to choose the right brand, the psychological burden caused by cognitive dissonance will be significant. In that sense it is believed that luxury foods give consumers an absolute sense of reassurance, which functions as a contributing factor in the development of purchase intentions. Thus, the following hypothesis (Hypothesis 5) should hold true.

As for car brands, considering the great risk involved in making the wrong choice due to the high cost of luxury cars or the low frequency of luxury car purchases, it is expected that purchase decisions in which there is still a possibility that the consumer will regret when choosing the brand will cause the them to feel a major psychological burden, much like luxury foods. It is believed that psychological factor of “it has to be this brand” influences purchase intentions for luxury cars. Thus, the following hypothesis (Hypothesis 6) should hold true.

Hypothesis 5. Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance will have a direct positive effect on purchase intention for subject luxury brands in the category of food.

Hypothesis 6. Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance will have a direct positive effect on purchase intention for subject luxury brands in the category of cars.

3.4.4. Hypotheses on Quality Evaluation

Kapfere [23] points out that luxury cars have their flaws. For FERRARI or PORSCHE, flaws such as a loud engine or limited seat space in pursuit of speed are examples of this. For ROLLS-ROYCE, an example of such a flaw would be the brand’s perception as having bad taste, which is a result of its pursuit of luxury.

The average consumer will most likely think “quality of a car = speed, comfort, mileage, noise, and safety”. In other words, there are many different evaluation axes for product quality. Therefore, it is believed that they do not consider luxury cars as quality cars because luxury cars sacrifice the quality of many features in pursuit of the quality of a single feature. Thus, Hypothesis 8 should hold true.

If these theories behind the hypothesis on luxury cars are applied to the food category, it would be hard to imagine a situation in the food category that would resemble cars in which the quality of certain elements of the product are sacrificed in pursuit of a particular element due to a trade off. In the case of food, the average consumer most likely thinks “quality of food = taste”. It is hard to imagine that many different evaluation axes for product quality exist, as is the case with cars. Furthermore, the taste of the three subject brands in the category of food, as well as their perceived quality, have been well established. Thus, Hypothesis 7 should hold true.

Hypothesis 7. Quality Evaluation will have a direct positive effect on purchase intention for subject luxury brands in the category of food.

Hypothesis 8. Quality Evaluation will not have a direct effect on purchase intention for subject luxury brands in the category of cars.

4. Hypothesis Tests

4.1. Overview of Questionnaires

Since this is a study on luxury brands, the participants of the questionnaires would be required to have a certain amount of income or assets. Furthermore, as a measure against participants who do not take the questionnaires seriously, the questionnaires were designed in a way to prevent inappropriate answers. A detailed overview of the Questionnaires is shown in Table 4. In the end, 500 sample questionnaires (250 males and 250 females) were collected.

4.2. The Hypothesis Tests

Next, a reliability analysis on the questionnaire results (see Table 3) was performed for each psychological factor. The results showed Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging between 0.384 and 0.873. Oshio [32] states that, although there are no clear standards for Cronbach’s alpha coefficient figures, a coefficient of over 0.70 or 0.80 is considered high, and the results need to be reexamined if the coefficients are below 0.50. Therefore, to ensure the validity of the results, QFOOD-3, QFOOD-6, QFOOD-7, QCAR-3, QCAR-6, QCAR-7, and QCAR-12 were removed from the equation. This resulted in Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging between 0.531 and 0.873. Next, since the range of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeded the minimum (0.50), which Oshio [32] suggested, a multiple regression analysis was performed by using the multiple regression model equation shown in Section 3-3 and the results are shown in Table 5. The results of the hypothesis tests are shown in Table 6.

5. Conclusions

Table 7 provides a Summary of these results. In the table, a circle indicates that the results of the standard partial regression coefficients (see the result of multiple regression analysis in Table 5) showed a significant correlation in at least two of the three subject brands for each product category. Moreover, a double circle indicates

Table 4. Overview of questionnaires.

Table 5. Result of multiple regression analysis about psychological factor.

Note: Significance level *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 6. Results of hypothesis tests.

Table 7. Effect of psychological factors on developing purchase intentions according to product category.

that the standard partial regression coefficients showed a significant correlation in all three subject brands and that the psychological factors for all three brands resulted in higher figures than the other psychological factors.

The results of this study suggest the following: 1) Differentiation from Others is an important factor in developing purchase intentions for both food and car luxury brands and is a particularly important factor for cars; 2) Conformity to Group Norms is not an important factor in developing purchase intentions for both food and car luxury brands in which consumers continue to feel a sense of rarity; 3) Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance is an important factor in developing purchase intentions for both food and car luxury brands; 4) Quality Evaluation is an important factor in developing purchase intentions for food luxury brands only.

The results suggested that luxury brand strategies can be applied to the category of food (a product category that was not generally thought of in the past as a product category in which luxury brand strategies can be applied), just as they can be applied to cars. This study also demonstrated which psychological factors should receive particular attention when coming up with strategies for luxury food brands. These are the contributions offered by this study.

However, the study lacks an important focal point: consumer personality traits. It goes without saying that a discussion on the effect of psychological factors on the development of purchase intentions without discussing personality traits, a psychological mechanism that is different for each person, would be incomplete. In order to make the study more exhaustive, there is a need to demonstrate how the results of this study would be different for each personality trait among consumers. This issue will be explored in future studies.

Cite this paper

KazutoshiFujiwara,Shin’yaNagasawa, (2015) Analysis of Psychological Factors That Influence Preference for Luxury Food and Car Brands Targeting Japanese People. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management,05,590-600. doi: 10.4236/ajibm.2015.59059

References

- 1. Sugimoto, T. (1992) Personal Attitude Construct Analysis for Brand Oriented Customers. Journal of advertising science, 27, 101-105.

- 2. Fujiwara, K. and Nagasawa, S. (2015) Relationship between Purchase Intentions for Luxury Brands and Customer Experience: Comparative Verification among Product Categories and Brand Ranks. Science Journal of Business and Management, 3, 1-10.

- 3. Miyazumi, T. (2014) Luxury Chocolate Brand GODIVA to Increase Number of Outlets in Japan to 300 within Next Five Years, Plans to Open Outlet in Tottori by End of Year to Achieve Goal of Having Outlet in Every Prefecture. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 22 August 2014, 14.

- 4. Schmitt, B.H. (1999) Experimental Marketing: How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, ACT, Relate. Free Press, New York. [Shimamura, K. and Hirose, M., trans. (2000) DIAMOND, Inc., 100].

- 5. Rae, J. (1834) Statement of Some New Principles on the Subject of Political Economy, Exposing the Fallacies of the System of Free Trade and of Some Other Doctrines Maintained in The Wealth of Nations. Hilliard, Gray, and Co, Boston.

- 6. Veblen, T.B. (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study in the Evolution of Institutions. Macmillan, New York. [Taka, T. trans. (1998) Chikumashobo].

- 7. Leibenstein, H. (1950) Bandwagon, Snob, and Veblen Effects in the Theory of Consumers’ Demand. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 64, 183-207.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1882692 - 8. Vigneron, F. and Johnson, L.W. (1999) A Review and Conceptual Framework of Prestige Seeking Consumer Behavior. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1, 1-15.

- 9. Dubois, B., Laurent, G. and Czellar, S. (2001) Consumer Rapport to Luxury: Analyzing Complex And Ambivalent Attitudes. Consumer Research Working Article, No. 736, HEC, Jousy-en-Josas.

- 10. Kumagai, S. (2005) Evaluation of Luxury Brands on the Basis of Acceptance Among Female College Students Using Multivariate Analysis. Journal of the Japan Research Association for Textile End-Uses, 46, 693-700.

- 11. Miura, T. (2013) Are Japanese Consumers Tough Consumers? Their Cultural and Modernistic Attributes and Marketing Strategy. Yuhikaku, Tokyo, 43-69.

- 12. Mason, R. (1981) Conspicuous Consumption: A Study of Exceptional Consumer Behavior. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

- 13. Mason, R. (1992) Modelling the Demand for Status Goods. Association for Consumer Research, Department of Business and Management Studies, University of Salford, Salford, 88-95.

- 14. Bearden, W.O. and Etzel, M.J. (1982) Reference Group Influence on Product and Brand Purchase Decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 183-194.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/208911 - 15. Rossiter, J.R. and Percy, L. (1987) Advertising and Promotion Management. McGraw-Hill Series in Marketing, New York.

- 16. Richins, M.L. (1994) Special Possessions and the Expression of Material Values. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 522-533.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209415 - 17. Dubois, B. and Laurent, G. (1994) Attitudes toward the Concept of Luxury: An Exploratory Analysis. In: Leong, S.M. and Cote, J.A., Eds., Asia Pacific Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 1, Association for Consumer Research, Singapore, 273-278.

- 18. Pantzalis, I. (1995) Exclusivity Strategies in Pricing and Brand Extension. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- 19. Dubois, B. and Paternault, C. (1997) Does Luxury Have a Home Country? An Investigation of Country Images in Europe. Marketing and Research Today: The Journal of the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research, 25, 79-85.

- 20. Wong, N.Y. and Ahuvia, A.C. (1998) Personal Taste and Family Face: Luxury Consumption in Confucian and Western Societies. Psychology and Marketing, 15, 423-441.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199808)15:5<423::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-9 - 21. Sugimoto, T. (1997) Consumer Psychology: Understanding Consumer Behavior. Fukumura Shuppan Inc., Tokyo, 82-83, 235.

- 22. Wiedmann, K.P. and Hennigs, N. (2013) Luxury Marketing: A Challenge for Theory and Practice. Springer Science and Business Media, Wiesbaden, 79-81.

- 23. Kapferer, J.N. and Bastien, V. (2009) The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands. Kogan Page, London. [Nagasawa, S., trans. (2011) Toyo Keizai Shinposha, Tokyo, 70-134.]

- 24. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, Ed. (2013) Nikkei Market Share Investigation 2014 Edition. Nikkei Publishing Inc., Tokyo, 136-250.

- 25. Fuji-Keizai, Ed. (2013) Food Marketing Handbook No.2 2014 Edition. Fuji-Keizai, Tokyo, 148.

- 26. Fuji-Keizai, Ed. (2013) Food Marketing Handbook No.3 2014 Edition. Fuji-Keizai, Tokyo, 101.

- 27. Nihon Keizai Shimbun (2006) GODIVA’s Revenues in Japan to Double within Five Years, Open 10 Outlets This Term, Expanded Business to Hotels. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 21 September 2006, 19.

- 28. Fukuda, M. (2013) Understanding Desire: From the Perspective of Brain Science. Koyo Shobo, Tokyo, 73-119.

- 29. Nihei, K. (2008) Reference Group Theory and Advertising Communication Strategy: Toward the Creation of Aspirational Group. Meidai Shogaku Ronso, 90, 75-88.

- 30. Kotler, P. and Keller, K.L. (2006) Marketing Management. 12th Edition, Prentice Hall, London. [Onzo, N. and Tsukitani, M., trans. (2009) Maruzen Publishing, Tokyo, 219.]

- 31. Festinger, L. (1957) A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Row & Peterson, Evanston.

- 32. Oshio, S. Analysis of Psychological Data.

http://psy.isc.chubu.ac.jp/~oshiolab/teaching_folder/datakaiseki_folder/09_folder/da09_02.html

NOTES

*Corresponding author.

1The brand with the largest market share for the sparkling wine market was MHD―Moët Hennessy Diageo, which owns Dom Pérignon, a luxury brand. For this reason, Suntory, which holds the second largest market share, was chosen as a subject brand. In addition, since market data for yokan (Japanese jellied dessert made of red bean paste, agar, and sugar) could not be obtained, Imuraya, which holds the largest market share in the Japanese desserts market (which includes desserts other than yokan), was chosen as a subject brand.

2What a consumer conforms to is not always a group and can be individuals such as actors or athletes they look up to.