American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

Vol.4 No.5(2014), Article ID:46426,12 pages DOI:10.4236/ajibm.2014.45031

Cote d’Ivoire’s Commodities Export and Shipping: Challenges for Port Traffic and Regional Market Size

Nomel P. Stéphane Essoh

Department of Transportation Economics and Maritime Management, School of Economics and Management, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, China

Email: stephnomel@hotmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 10 January 2014; revised 10 February 2014; accepted 28 February 2014

ABSTRACT

The global integration with the growth of the world population generated a constant need of goods where trade took place with both inputs and ready-made products. Although this global need has led to a diversification of exports of goods, it still requires special commodities from tropical Africa and trade partners in West Africa that may supply more their specialized products which can be moved in cargo between destinations. This paper identifies especially Cote d’Ivoire’s commodities export and shipping market structure with its main agricultural products which makes him the world’s dominant producer and exporter of cocoa beans. It develops the importance of export crops structure for local economy driven by the international demand for cocoa beans. And it finally could indicate in our future study whether the possibility of pricing power and export taxes affecting the shipping market has a decisive impact on the port traffic and accelerates growth.

Keywords:Commodities Export, Cote d’Ivoire, Cocoa Market, Special Crops Shipping

1. Introduction

The growth of the world population generates global and constant need of goods. Figures indicate that a 4 percent decline in GDP results in a fall of 8% for trade and 15% to 20% for transport; one in every six in the world is hungry and lacks enough foods and raw materials while the population has to be grown by 45% by 2015 [1] . This world hunger requires special commodities from tropical Africa and trade partners in Western Africa that may supply more their specialized products that can be moved between destinations through cargo that implicates seaborne trade.

This changes considerably the world trade structure and has transformed the global seaborne transportation systems while the container traffic has rapidly increased. In order to benefit from economies of scale in this competitive shipping market, the shipping lines have invaded West African ports especially in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana that constitute both leaders in cocoa production and export. This development increased the number of large ships calls at coastal ports such as the ports of Abidjan and San Pedro (Cote d’Ivoire) and the ports of Takroadi and Tema (Ghana) with their rapid market development of special crops handling and agricultural commodities export. The substantial change of commodities production and export shipping industry and port management have a decisive impact on the whole market size of Cote d’Ivoire’s commodities in West Africa and continue to influence mainly the sectors in sub-region that engorges the most populated zone of African continent. However, the global views from very few researchers like [2] -[4] studying West Africa sub-region, provide insight into how the market structure of West African cocoa has changed and may further change due to liberalization.

However, in this paper, we tend to examine Cote d’Ivoire’s commodities exports and shipping market that involve the four (4Cs) major regional crops such as coffee, cocoa, cotton and cashew nuts. An emphasis on the country’s main agricultural products like the export market structure of cocoa sector is discussed which we will attempt to find out in our future studies whether the shipping activity of these commodities at the port of Abidjan could perform taxation policy, increase the fiscal revenues and by ricochet, and generate productivity and wealth that affect the regional economy.

2. Commodities Export in Cote d’Ivoire and Its Hinterland

2.1. Port of Abidjan and Commodities Export

Following the international trade with its growing trend, the port of Abidjan has been sharing the 95% of the country’s trade mostly handled and done by sea [5] . Contributing about 60% of the country’s annual budget as published in transportation agency [6] [7] the port of Abidjan is an engine that called since four decades the lung of the country’ economy. Despite the political crisis occurred in Cote d’Ivoire since 2002 had direct drawbacks on the port throughput and affected the movement of goods and services in the export sector, the port remains the gateway for landlocked countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger that constitute a considerable portion of the port’s hinterland which remains an important asset for regional economic integration and development (see Figure 1).

Despite the global limitation of port traffic in many African ports because of several factors such as the structure of the trade, limited investment, inadequate transport facilities and procedures as well as tariffs that penalize container port traffic [8] , there was significant growth of container traffic in the whole of the continent, especially in West Africa. And the export traffic of Port of Abidjan which started informally in late 1960s is now recording a growing trend because of its capacity in handling the regional commodities for exports. Where a former French shipping line DELMAS, which is now known as CMA-CGM, is a big player in West Africa region. As illustrates [9] , this shipping line shared almost 75% of the Europe-West Africa traffic and in 2002 had a traffic size of 1,206,000 TEUs that had increased to 1,441,000 TEUs in 2005 representing a rise of 1.2% in volume. However expectation of volume increasing at the port of Abidjan in the future can be observed because of the growing trade and the increasing participation of the private sectors in their capacity to manage their respective production required for the development of the ports activity. World class carriers and terminal operators especially with a concession of terminal to operator like Bollore Africa Logistics, remain tangible factors that could contribute to the competitiveness of the country’s commodities export and market size. The additional expansion of both the ports of Abidjan and of San-Pedro in Cote d’Ivoire with their investment in new infrastructures and gantry cranes including their dredging plans, have been executively successful so that larger vessels can be accommodated, information technology can be improved as well as with a well-skilled labour performance [10] . All contribute to the improvement of the port throughput in order to facilitate the commodities export and revitalize the international trade.

2.2. Market Outlook and the Country Export per Commodity

The Cocoa beans in Cote d’Ivoire were exported through the port of Abidjan and represent 48% of the production in 2007 whereas the other percentage has been handled by the port of San-Pedro (the second port of the country). Commodities such as cotton fiber and seeds, pineapple, banana, rubber, canned fish, timber and coffee

Figure 1. Cote d’Ivoire and it hinterland in West Africa region.

were also exported through the port of Abidjan. The volume and composition of production varies from season to season according to the market prices, and seasonal rainfall patterns. As shown in Table 1, agriculture represents more than 25% of each country’s GDP and at least 70% of their working population is engaged in some form of agricultural activity which describes the importance of the agricultural sector in supporting the whole economy.

Despite that the export of general cargo at the port of Abidjan fell at 15.3% in 2011, important exports of cocoa beans with more than 52.9% and rubber (13.6%), have been recorded for which around 3.35 million tons were loaded at the end of year 2011 compared to 3.96 million tons in 2010 and 4.39 million tons in 2009. The traffic at the port level registered also major export commodities like coffee and cotton. Coffee beans with 35,100 tons in 2011 against 96,197 tons in 2010 and 87,985 tons in 2009, represents a 63.5% sharp fall comparatively to the year 2010. The export traffic related to cocoa beans was special in 2011 year with 609,443 tons compared to 398,542 tons exported in 2010 and 484,437 tons in 2009, representing a 52.9% growth comparatively to 2010. The Processed Cocoa recorded 214,701 tons in 2011, compared to 241,868 tons in 2010 and 253,154 tons in 2009 which represent a drop of 11.2% compared to the 2010 season. The export of Cotton Seeds registered 116,389 tons in 2011, 245,214 tons in 2010 and 197,993 tons in 2009 (refer to Table 2).

Despite the considerable and important production recorded globally in the agricultural crops sector as indicated in Table 1, Cote d’Ivoire had a negative export growth from 2000 to 2006 which corresponds to the period of relative political and economic instability. The −9.5% of export share of Burkina Faso is mainly due to the poor cotton harvest [11] .

3. Special and Major Crops Production

Besides cocoa, coffee and cotton, other commodities such as cashew nuts, shear nut pineapple, banana, rubber, log timber, sawn timber, and canned fish are among the products exported through the port.

The cashew-nut knew an export of 307,505 tons in 2011 and 367,406 tons in 2010 and comparatively to 352,190 tons in 2009 which represent a fall of 16.3% compared to year 2010. Pineapple in its side recorded 37,089 tons in 2011, against 48,916 tons in 2010 and 57,546 tons in 2009; representing 24.2% of a fall comparing to 2010. The sector of Banana knew a growth during four years seasons. In 2011, its export traffic registered

Table 1. Population and economic indicators of Cote d’Ivoire and its hinterland (2007) destination of crops.

Source: World Bank, 2008b.

Table 2. Major exported cargo of commodities handled by the Port of Abidjan (in tonnage).

Source: Port of Abidjan, Activity Report 2011.

259,941 tons and 294,344 tons in 2010 comparatively in 2009 with 272,247 tons. Rubber and latex accounted a growth of 13.6% where exports recorded gives 150,845 tons in 2011, 132,750 tons in 2010 and 117,215 tons in 2009. Timbers export registered 108, 495 tons in 2009, 129,500 tons in 2010 and lately in 2011 recorded 94,189 tons. The export of Processed timber in its size recorded 124,902 tons in 2009, 138,639 tons in 2010 and 118,002 tons in 2011 (refer to Table 2).

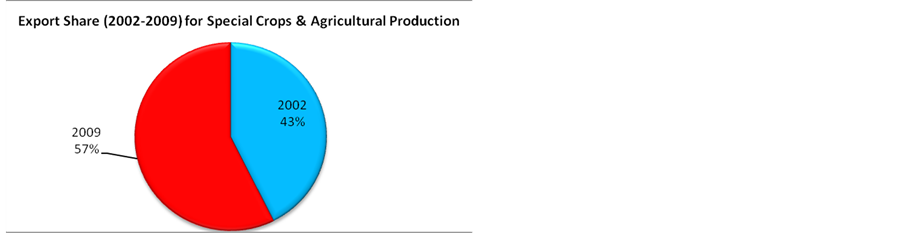

For the purpose of this study, we emphasize on the 3Cs (Cocoa, Coffee and Cotton) as special export crops because they represent the major crops exported by the countries and handled by the port. As indicated the Figure 2, the production of these special crops knew a steady increase and represented 57% of the total agricultural production in 2009 against 43.8% in 2002, with a global increase of 12% in five years. This growth has been possible because of the increase of commodities price, favorable weather and better yield with improvement of agriculture methods and practices implemented by the local producers.

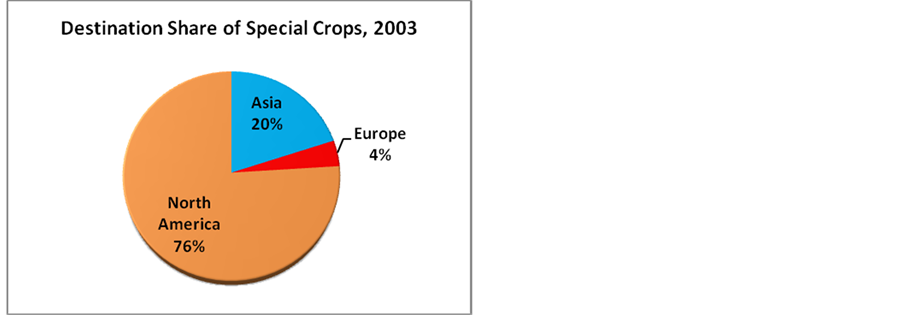

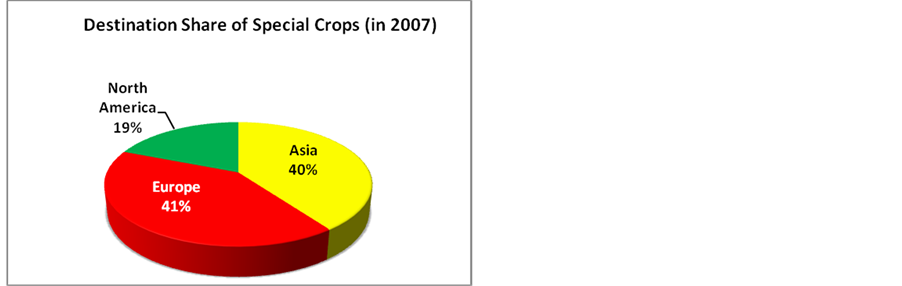

The global economic trend of Asia region with its increase of market share constitutes also a factor in the development of Cote d’Ivoire commodities export sector. Trade with Asia, especially with China and India, has increased dramatically. As illustrates the Figure 3 and Figure 4, trade of special crops from Cote d’Ivoire with Asia grown from 20% in 2003 to 40% in 2009 based on the country’s total special crops. The North American traffic in its size grows from 4% to 19%, while European Union traffic today records for 41%.

The increase in the Asian market is mainly due to the cotton export to China and cashew nuts, and timber exports to India. The export traffic growth of North America is essentially due to the increase of cocoa exports to

Figure 2. Special crops export share of agriculture.

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Port of Abidjan—Cote d’Ivoire.

Figure 3. Special crops export destination.

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Port of Abidjan—Cote d’Ivoire (2009).

Figure 4. Special crops export destination.

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Port of Abidjan—Cote d’Ivoire (2009).

the United States. While the decrease of the European export size is mainly due to the fact that the change in Government and the civil crisis during the five years period (2003-2009) have prompted the Ivorian government to diversify its trading partners. Additional reason is the globalization that has made possible the export of commodities for the county to trade cocoa with the USA and other crops directly with the Asian market. Cote d’Ivoire is a large worldwide exporter of cocoa beans, cotton and cashew nuts, and remains the world’s top country producer of cocoa beans, while its neighbors and hinterland countries such as Mali and Burkina Faso as West Africa’s largest cotton producers and both the world’s fifth largest producers of cotton [11] and cashew nuts, where their commodities are transited and exported through the port of Abidjan. However, it is relevant to take a closer look at the traffic of these commodities because of the important role they play not only in these countries’ GDP but also in the regional market development.

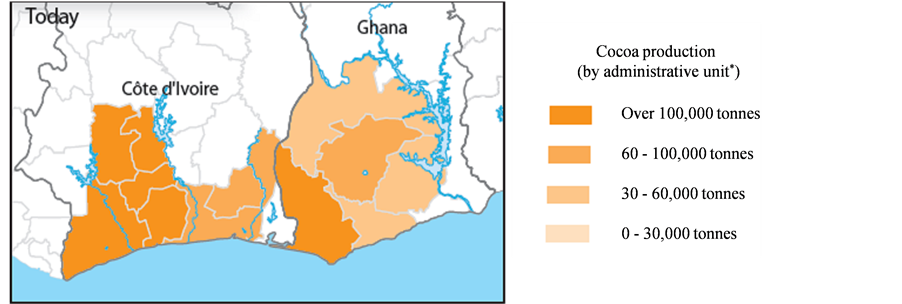

3.1. Cocoa Production and Demand Trends

Most of the world’s cocoa production is found in West Africa, as shown in Figure 5. Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana both with about 60% of the total tonnage are the world’s largest cocoa producers. The global production and demand trends indicated that the crop season of 2010-2011 was exceptional owing to the favorable impact of the La Niña weather phenomenon on all West African growing regions [12] for the second. In Cote d’Ivoire cocoa production is done in the southern part of the country mostly in the forest areas as shown in Figure 5 where transport logistics provision also accommodate this geographical area. The southwestern farms produce over 100,000 tons per administrative unit five (05) and the southeastern farms produce up to 100,000 tons per administrative unit three (03) [13] . Between 2005 and 2009 the average production in the country reached almost 1.4 million tons of cocoa beans a year, of which 97% was exported [14] . Despite the conflict which affected Cote d’Ivoire, in 2010-2011 more than 1.5 million tons of cocoa were produced while Ghanaian production in its side has reached just 1 million tons. However, the uncertainty generated by the conflict in the country with the subsequent trade embargo in 2011 has significant impact on the international prices and consequently the export contributed by rising the Asian demand.

As illustrated in Table 3, Cocoa plays a major role in the Ivoirian’s economy and represents almost 40% of the country’s total export and 50% of the agricultural exports. The Cocoa sector is the most important productive resource for the economy and contributes with 15 percent of GDP and 35% of the total export. In 2007, the sector covered more than 20% of the government revenue. The Ivorian economy relies greatly onto cocoa production whereas any impact on the market affects all the other economic sectors. This sector has generated around USD 2 billion per year of export income in recent years. Cocoa beans account for 74% of total export of cocoa, cocoa paste 12.5%, cocoa butter 9%, husk and shell 3.5% and both powder and cake 2%. And improvements of the cocoa sector are therefore highly encouraged for economic stability of the country. Cocoa production is price sensitive, and its cycle moves closely with the term of international trade [15] . Its integrity needs to be preserved by better handling from the farm to the importer.

3.2. Cotton Production

Cotton is one of the major crops produced in Cote d’Ivoire and occupies the third position behind cocoa and coffee in terms of export revenues generated. As one of the important cash crops for the Ivorian economy, Cotton production is mostly done in the northern region of the country by a small scale of farmers with an average of 4 hectors for each. Between 2000 and 2004, the total average for Cote d’Ivoire and its neighboring countries Burkina Faso and Mali was the 55% of the regional export where the cotton seed reached about 95,000 tons. Recent production of cotton fiber is estimated to 5 million tons in five years from 2007 to 2011. Cotton export from the hinterland market (Burkina Faso and Mali) represents more than 60% of the agricultural export and accounts more than 30% of the country’s total export. The cotton export is one of the determinants of the economic importance of the production in Cote d’Ivoire and its hinterland countries. However, after having received a low share of world prices around 54% during 1990s the production has reached 64% in recent years. Accounting more than 93%, cotton lint represent most of the exports the cotton production in general followed by the cotton seed (5.2%) and cotton oil (1.4%) which makes Cote d’Ivoire the fourth largest exporter of cotton in Subsaharan Africa behind Burkina Faso, Mali and Benin. However, that contributes significantly to the livelihood in rural areas. Until late 1990s a single vertically integrated state enterprise known as Compagnie Ivoirienne de Developpement des Textiles (CIDT) was responsible for organizing virtually all services required for cotton production and marketing with institutional frameworks derived from the French colonial heritage [16] . The second company is Cotton-Ivoire an equity joint venture that is active in the north-west region of the country. And a third one is a Switzerland based Aiglon group known as LCCI is active in the North-East of the country.

3.3. Coffee Productions

Coffee is the second most important crop in the agricultural production of the country and very important source of income for all holders as well as second source of foreign exchange. During the 1960s and 1970s, Cote d’Ivoire was the Africa’s largest exporter of coffee. In 2006, Coffee exports accounted 166 million with 5.4% of the total agricultural exports and 1.8% of total exports comparatively in 2004 (131 million). Coffee extracts represent one third of the coffee exports and green coffee corresponds the two third. However, Cote d’Ivoire is the third largest coffee exporter in Africa after Ethiopia and Uganda.

Figure 5. Cocoa production zone in West Africa region.

Source: Source: FAO Statistics Division.

Table 3. Economic importance of cocoa production in Cote d’Ivoire (Average for 2001-2009).

Source: FAO Statistics Division, 2010.

4. Market Structure of the 2Cs (Cocoa and Coffee) in Cote d’Ivoire

4.1. Institutional Operation Structure

The institutional and policy development in Cote d’Ivoire’s agricultural products lies on the country experience as French colony where the Caisse de Stabilité des Produits Agricoles (CAISTAB) was established [17] in regulating farm gate and export prices of the two major crops (coffee and cocoa), providing extension service and inputs and also collecting substantial taxes. Although the CAISTAB was not directly in charge of the transportation of cocoa, comparatively to the coffee that it did, it allowed private exporters to operate within a system of quotas [3] which was relatively successful for export competition in the two sectors. Consequently, despite a certain number of drawbacks of exogenous and endogenous factors such as the decline of world market prices and the country’s sociopolitical crisis occurred, the CAISTAB was dissolved and replaced by three new administrative, commercial and financial agencies in order to monitor and manage the sectors. To define and enforce a regulatory framework ensuring competition at all levels of value chain, the Authorité de Regulation du Cafe et du Cacao (ARCC) was created and established in October 2000. For managing the price stabilization systems through taxes of exports and forwarding selling, the Fonds de Régulation et du Controle (FRC) was created in August 2001 and established especially for financial regulation of the fund. The third agency is the Bourse du Café et du Cacao (BCC) that was established for stock marketing managed by farmers and exporters that are especially responsible for managing exports operations of agricultural commodities such as cocoa and coffee. The last one created in October 2001 concerns the Fonds de Développement et de Promotion des Producteurs de Café et Cacao (FDPCC). This is an agency for the development fund established by producers and funded by voluntary levy in order to finance the demand-driven development programs. All these four agencies allow the government to strengthen the position of farmers by providing information about prices and encouraging farmers to develop cooperatives in order to gain and hold more bargaining power (refer to Figure 6).

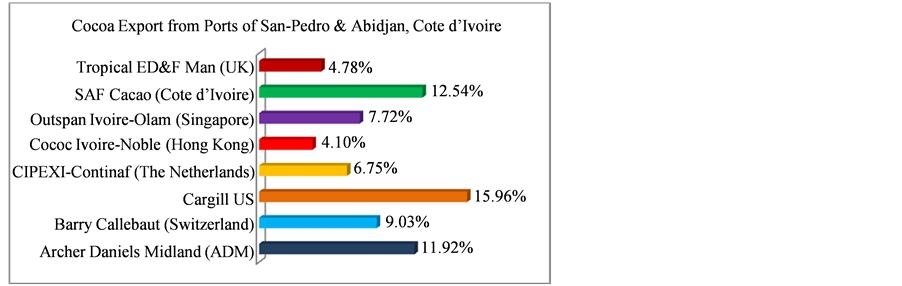

However, for export purpose, the Cocoa is conditioned once it arrives at the port of Abidjan or at the port of San-Pedro, and shipped to processors largely dominated by major multinational exporters such as Archers Daniel Midland (ADM), Cargill and Bary Callebaut operating in the sector. Figure 6 shows how the regulatory frame of cocoa supply in export from Cote d’Ivoire is structured. Three years after the dissolution of the CAISTAB which had a impact on the market configuration of the cocoa sector, 14 firms controlled more than 85% of the export market where the top 5 firms among the 61 exporters controlled almost half of the total exports. As indicates the Table 4 and Table 5 and Figure 7, Cargill West Africa (16.4%), ADM Cocoa SIFCA (11.9%) and Tropical (8.3%) are the three largest firms that still control the export market. It is possible for us to

Figure 6. The Regulatory frame of cocoa supply in export from Cote d’Ivoire.

Source: Design by author based on empirical investigation, 2011.

Figure 7. Cocoa export from ports in Cote d’Ivoire.

Source: By Author with reference data from BCC (Bourse de Café Cacao), ARCC (Autorité de Régulation du Café et Cacao), Cote d’Ivoire, Oct. 2010

conclude that at least two possibilities can be considered about the structure of the cocoa export market in Cote d’Ivoire: either the high competitive of market with many exporters competing for the output of larger number of producers, or the restricted market with a large number of domestic cocoa producers that face a few large exporters (refer to Figure 7). The other features that distinguish a perfect competitive market from an imperfect competitive one are shown in the following Table 6. The description of cocoa production process along with the value chain in order to provide an understanding of circumstances and the market environment faced by all the actors involved is crucial. Foreign multinational exporters have increased their grip on the cocoa exports from Cote d’Ivoire, while domestic export companies have been losing market influence and share which however, affected the coun

Table 4. Largest cocoa exporters from Côte d’Ivoire (March 2008).

Source: Source: Oxfam (2009), p. 9.

Table 5. Largest cocoa exporters from Côte d’Ivoire (March 2008).

Source: BCC (Bourse de Café Cacao), ARCC (Autorité de Régulation du Café et Cacao), Cote d’Ivoire, 2009.

Table 6. Characteristics of Cote d’Ivoire’s cocoa export market.

try’s economy. When the Ivory Coast’s government tried to increase its income from the cocoa trade by raising custom duties in 2001, the large exporters responded by stopping exports until the new custom duties were reduced. Ten large companies, led by the US companies Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), control exports.

4.2. Prices and Taxes

As described above, in Cote d’Ivoire, the trade of the main agricultural commodities such as cocoa and coffee is governed and monitored by Bourse du Café et du Cacao (BCC) and the Coffee and Cocoa Regulatory Authority (ARCC). The board’s quarterly task is to fix a minimum price that is paid to the farmers for cocoa production [18] . In order to prevent major exporters gaining or hold a monopoly of the market, the state of Cote d’Ivoire has imposed a ceiling on the amount of cocoa that an individual exporter can purchase per quarter. However, BCC sets a guaranteed minimum price for export, but the price may be higher depending on demand.

However, there are various external factors that determine the actual price that farmers receive per ton of cocoa beans. The daily international cocoa price is negotiated on major futures [19] such as the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange (LIFFOE) and the New York Board of Trade (NYBT) that constitute the most important futures markets which are regarded as dominant factor. Several types of prices for cocoa are involved in the export chain of cocoa in Cote d’Ivoire which economic agents are concerned with. The farm-gate prices that are calculated as an average price for the six regions and constitute the domestic prices itinerant that crops collectors pay in cash to farmers, the indicative prices is used only for general orientation of farmers and not enforced and is seasonably established by the government as an indicative farm-gate price, export prices concern the discounted world prices set by exporters as a function of cocoa future prices on international markets depending on the quality of cocoa bean for each campaign or harvest season.

Taxation of the cocoa sector is initially a combination of fiscal and quasi-fiscal levies which export taxes are considered to be an important source of fiscal revenue and that also generate profit through indirect land tax. Fiscal levies as a part of budget revenue combine three major levels of specific and ad valorem taxes. Export tax known as droit unique de sorties or DUS is a specific tax set in local currency (FCFA) per kilogram of cocoa bean that can be periodically revised. For example for 2009-2010 crop season exporters pay 210 FCFA (US $0.57) as the DUS when cocoa cargo is loaded into the vessel at the port of Abidjan and of San-Pedro. Registration tax known as tax d’enregistrement is an ad valorem tax set at a percentage of the price CIF and can be also periodically revised. Exporters pay the registration tax first when they register and fill legal formalities with the government as official cocoa exporter annually thereafter. Other state levies documented in European Union policy as implicit state charges is set per kilogram at 3FCFA (US $0.006) constitute the taxes charged to itinerant buyers.

However, the tax setting amount is a function of a complex power balance between the central government and several public entities (ARCC, BCC, FRC, and FDPCC including FGCCC) involved in management and investment in the cocoa and coffee sectors.

4.3. Export Case Study with Cocoa Crops

The first possibility in the observation indicates that although the cocoa export market in Cote d’Ivoire is high, it is not so competitive and perfect which evidence of competition can be found in what seems to be a substantial degree of pass-through to domestic producers of international prices since late 2002 year which have been trending in the same direction. A study from Alexei Kireyev [20] argued about a simple correlation between the world and domestic farm-gate prices for 2003-2009. This can therefore be interpreted as demonstrating a fair degree of competition among exporters on Cote d’Ivoire Cocoa export market. At the same time, the share of the world prices received by producers has been very unstable as it has declined from 51% in 2001 to 39% in 2004 and then increase later again to 45% in 2009. As shown in Table 6, it indicates that this competition is not perfect. Here, although the competition among exporters may be intensified, the difference with an average of 56% of the export price suggests that less than half of the export price has actually been passed to producers for the period of 2003 to 2009. From January to July 2003 the difference between domestic and international prices was never more than 41% of the international price.

The second possibility assumes that the cocoa export market structure in Cote d’Ivoire represents an oligopsony. During the 2008-2009 season with a total of 97 exporters registered, only 62 actually exported cocoa while 42 only exporting amounts has exceeded 10,000 tons. Moreover, nine largest entities exported over 70% of the country’s cocoa where the top six firms has accounted for over 50%. However, the oligopsonistic situation may not be particularly strong as there is a minimum “competitive fringe” that includes one dozens of buyers and constitutes almost the half of all purchases.

Looking at the structure as shown in the above Figure 7, it is not surprising to deduct that most of Ivorian exporters are either subsidiaries of or otherwise linked to large multinational corporations which three major firms such as Archer Daniels, Midland (ADM), Barry Callebaut, and Cargill US buy over 40% of the cocoa beans produced in the world.

Since cocoa is mainly sold through some forward contracts, the expectations of a good or bad crop in Cote d’Ivoire affect the declines or increases in the international prices. Moreover, in principle a country can improve with the pricing power its terms of trade by imposing and export tax on its main exportable commodity. And the case of Cote d’Ivoire with its leadership in cocoa export is tangible evidence. Imposed by a large country such a tax affects export supply and demand but also has substantial distributional and welfare implications. Here, same as the firm which is under non-perfect competition can face a downward sloping demand and can increase profit by suppressing output below the level where their marginal revenue equals to marginal costs, the government can restrict the exports of cocoa by way of an export tax.

4.4. Analysis of Export Market and Demand

By analyzing the export demand of Cote d’Ivoire cocoa crops, we can assume that trade is always balanced and the foreign demand growth can be given if other countries do not alter their trade policies in retaliation for export tariff, there will be a perfect competition within the country and no domestic divergences leading the supply to show the marginal social cost of export. And the revenue raised by the country authority from the export tax is spent on imports and does not affect domestic demand and supply. The optimal rate of an export tax rate depends on the price elasticity of demand for cocoa exports.

Analysis of the case in Cote d’Ivoire assumes that the optimal rate depends not only on the elasticity of export demand but also on the number of the competing firms. The larger the number of exporters, the closer the market is to perfect competition, the lower is the optimal export tax [21] [22] .

The price elasticity of export demand for cocoa seems to be relatively high although it cannot be known with any degree of certainty. Based on indirect indications, it is not perfect elastic and fairly high because Cote d’Ivoire can sell all its cocoa output in the international market. Cote d’Ivoire could export virtually all its production of cocoa. Despite the financial crisis in mid 2009, when cocoa prices for cocoa spiked, the international demand for beans remained robust.

It therefore shows that the demand for agricultural commodities plays important role in the shipping market and has a direct influence on other raw material production which may increase the cost of transport and shipping services.

Although the substitute goods like tea and coffee would suggest higher supply elasticity in the long run, consumer preferences for cocoa-based drinks and chocolates are strong. Other key factors of the cocoa production such as land, wines and climate are fixed and cannot be used as purposes. They rather support the arguments that cocoa supply has low elasticity.

The rate of an optimal export tax depends on the degree of market competition and if local exporters are perfectly competitive, the optimal rate will be a function of the inverse elasticity of demand for cocoa which may not be the case for Cote d’Ivoire’s export market. Then the optimal rate may be still positive but also lower than rates created with perfect competition if local firms are not perfectly competitive.

5. Conclusions

With exports of goods and services accounting for more than 50% of the country’s GDP in recent years, the external sector is of vital importance for the Cote d’Ivoire economy. Around 52% of the total income of rural households comes from agricultural commodities and exports, and producers of the three (3Cs) major export crops (cocoa, coffee and cotton) where agricultural production accounts for 77% of the total income. Observations indicate that Cote d’Ivoire’ export market consists of small producers that face several hundred local intermediaries; three to ten large buyers, mainly subsidiaries’ exporters controlled by ADM, Barry Callebaut and Cargill. Obviously, a few buyers control the majority of Cocoa export in Cote d’Ivoire and the world cocoa market, and therefore the taxation of cocoa export from Cote d’Ivoire can be analyzed on the assumption that the cocoa market is oligopsonistic.

However, the impact of a country on international price for a commodity depends on its export market share which also increases its shipping industry capacity. If Cote d’Ivoire alone produces about 40% of the world cocoa output, the international prices for cocoa then largely depends on the quantity and quality of cocoa exported from Cote d’Ivoire and has in the other hand impact on the shipping market and freight. Some factors such as bad weather, plant diseases and delays in the harvesting season have immediate influences and can be translated into higher international prices. However, these observations assume that the volatility of the commodities sector indicates that agricultural production depends on the seasonal factors, political stability and international trade price. But all should be improved because of the farmers’ capacity in recomposing the harvest and agricultural methodology development in their respective crops production. The competitiveness of the port of Abidjan in handling capacity of the commodities export constitutes some challenge of the regional market.

However, it is paramount to strengthen the restructuration of stakeholders by reforming the special crop sector in order to respond to the international trade demands in term of quality and assure as well the production. Building capacity for farmers community with resourceful training, course refreshment, excellent knowledge of commodity market and understanding of several specializations could contribute to a better productivity. The stabilization of the sociopolitical environment with the increase of transparency and good governance in institutional decision making constitute additional recommendation in which sustainable participation framework for commodities and special crops export can be efficiently managed in order to increase the trade volume.

References

- ITF, International Transport Forum (2009) Transport for Global Economy. Leipzig, 26-29 May 2009.

- Fold, N. (2002) Lead Firms and the Competition in “Bi-polar” Commodity Chains: Grinders and Branders in the Global Cocoa-Chocolate Industry. Journal of Agrarian Change, 2, 228-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0366.00032

- Losch, B. (2002) Global Restructuration and Linearization: Cote d’Ivoire and the End of the International Cocoa Market. Journal of Agrarian Change, 2, 206-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0366.00031

- Wilcox Jr., M. and Abbot, C.P. (2004) Market Power and Structural Adjustment: The Case of West African Cocoa Market Liberalization. American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Denver, August 1-4.

- Bonnifait, J. (2006) Dossier Port d’Abidjan. Jeune Afrique Economy. 2238, 43-100.

- Transport, M.O. and Abidjan, G.D.o.p.a.ma. (2006) Statistical Bulletin of Port & Maritime Affairs. Abidjan: General Directorate of the Port and Maritime Affairs, Abidjan.

- Nomel, E. (2013) Shipping and Invasion of Second-Hand Vehicles in West African Ports: Analysing the Factors and Market Effects at the Port of Abidjan. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 3, 209-221.

- Harding, A., Palsson, G. and Raballand, G. (2007) Port and Maritime Transport Challenges in West and Central Africa. World Bank SSATPP Working paper, No. 84.

- SSATTPP (2007) Port and Maritime Transport Challenges in West and Central Africa. World Bank SSATPP Working paper, Washington DC, No. 84.

- Gossio, M. (2010) La Compétitivité du Port Autonome d’Abidjan—25 millions de tonnes de marchandises en fin d’année. Competitiveness of the Port of Abidjan: 25 Million Tonne of Cargo by the End of the Year. Interview of Port of Authority at Africa, 24 October 2010.

- FAO, UN Food and Agricultural Organization (2006) 2005-2006 Statistical Yearbook. No. 2.

- ICCO (2012) Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics. XXXVIII, N 1, Cocoa year 2011/2012.

- FAO (2004) The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets. Commodities and Trade Division, UN Food and Agricultural Organization, Working Paper, No. 5.

- CGFCC (2009) Campagne de Commercialisation 2008/2009. Comité de Gestion de la Filière Café Cacao, Abidjan.

- World Bank (2007) Cote d’Ivoire: Volatility, Shocks and Growth. Policy Research Working Paper, No. WPS4415.

- UNCTAD (2006) Trade and Development Report, Review of Maritime Transport. United Nations, Geneva. http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/rmt2006_en.pdf

- Abbott, P. (2007) Distortions to Agricultural Incentives in Cote d’Ivoire. The World Bank Agricultural Distortions Working Paper, Washington DC, No. 46.

- USDA (2001) Cote d’Ivoire: Cocoa, New Marketing Systems for Cocoa and Coffee. Global Agricultural Information Network GAIN Report, No. IV1013. Foreign Agricultural Service US Embassy, Abidjan, 3-7, October 2001.

- ICCO (2007) Study on the Impact of Terminal Markets on Cocoa Bean Prices. International Cocoa and Coffee Organization, Market Committee Eleventh Meeting, EBRD Offices, London, September, No. MC/11/4, 3-30.

- Kireyev, A. (2010) Export Tax and Pricing Power: Two Hypotheses on the Cocoa Market in Cote d’Ivoire. IMF Working Paper, African Department, JEL Classification No. F22, F42, O15, 11-30.

- Corden, W.M. (1974) Trade Policy and Economic Welfare. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 171-172.

- Helpman, E. and Krugman, P. (1989) Market Structure and Foreign Trade. MIT Press, Product Varieties and the Measurement of International Prices. American Economic Review, 84, 84-87.