Open Journal of Gastroenterology

Vol.04 No.10(2014), Article ID:50835,10 pages

10.4236/ojgas.2014.410048

Primary Care Practitioners’ Views on the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors Associated with Alginate-Antacids for Better Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptom Control: Results of a National Survey in Spain

Carlos Martín de Argila1*, Mercedes Ricote Belinchón2, Agustín Albillos Martínez1

1Gastroenterology and Hepatology Department, Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, Alcalá University, Madrid, Spain

2Mar Báltico Primary Care Center, Madrid, Spain

Email: *cmartina@salud.madrid.org, mricoteb@gmail.com, aalbillosm@meditex.es

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 19 August 2014; revised 4 0ctober 2014; accepted 19 October 2014

ABSTRACT

Background: Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a prevalent disease in Western countries. Despite effective treatment modalities, in some patients total symptom control is not achieved in clinical practice. A cross-sectional study was designed to assess primary care practitioners’ views on the effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) as monotherapy in the control of the most common symptoms of GERD (heartburn and regurgitation), as well as to determine the level of implementation of the “combined therapy” (PPI + alginate-antacids). Methods: A questionnaire on different aspects of the management of GERD was completed by 1491 primary care physicians. The questionnaire was composed of 11 close-ended questions with one-choice answer, with a total of 52 items, covering the main data from patients presenting with GERD. Results: Treatment with PPI alone was mostly considered insufficient for the control of GERD symptoms. The combined treatment of PPI + alginate-antacids was used for 37% and 21% of physicians for treating heartburn and regurgitation, respectively. A better control of symptoms, an increase in the onset of action and to reduce nocturnal acid breakthrough were the most frequently argued reasons for the use of PPI + alginate-antacids. A high percentage of participants believed that treatment with PPI alone was insufficient for the control of symptoms and 39.8% of physicians reported the persistence of heartburn, 38.6% the persistence of regurgitation and 43.2% the persistence of epigastric discomfort in more than 25% of their patients treated with PPI as monotherapy. The most common schedule for the use of the antacid medication was on demand. Conclusions: Spanish primary care physicians consider that a high proportion of GERD patients continue to suffer from symptoms during PPI treatment alone. On-demand “combined therapy” (PPI + antacid) is considered an efficient option to control reflux symptoms still troublesome in patients with PPI treatment alone.

Keywords:

Alginate-Antacids, Cross-Sectional Study, Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Heartburn, Primary Care Physicians, Proton Pump Inhibitors, Regurgitation, Survey

1. Background

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) presents with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. It is one of the most common diseases in Western countries, with an estimated prevalence of 10% - 20% [1] [2] , and with an incidence of approximately 5 per 1000 persons a year [2] . In addition, the occurrence of GERD has been increasing during the past two decades [3] . Recent studies have determined that GERD is the most frequently diagnostic between gastrointestinal diseases in USA (8.9 millions of visits) [4] . Complications of excessive exposure of the esophagus to gastric contents are esophagitis, peptic stricture formation, Barrett’s esophagus, ultimately esophageal adenocarcinoma and several extra-esophageal symptoms [5] - [7] . The chronicity of GERD disrupts many aspects of the patients’ everyday lives, through interference with normal activities, such as eating and drinking, work, sleep, and enjoyment of social life [8] [9] . Although almost half of adults have their symptoms for 10 years or more [2] , consultation rates are low. Only 5% - 30% of individuals with GERD consult a physician about their symptoms each year [10] . It has been shown that GERD accounts for around 5% of a primary care physician’s workload [8] [11] . Patients’ perceptions of their condition, comorbidity factors and external reasons such as work and social factors are mainly related to consultation rates for GERD [12] .

The pathogenesis of GERD is multifactorial, involving an increase in the number of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations as compared with healthy subjects, which is probably the most significant abnormality [13] . Main goals of treatment include disappearance or improvement of symptoms, healing of erosive esophagitis, and prevention of relapse and complications. Although proton pump inhibitors (PPI) have emerged as the most effective therapy for symptom relief, healing and long-term maintenance in the treatment of GERD patients, there is certainly room for improvement when complete resolution of symptoms is considered as end- point. In 30% - 40% of patients PPI therapy fails to completely resolve symptoms [14] . Different explanations have been proposed for these PPI noncomplete responders, including reduced efficacy of PPI in controlling noc- turnal acid breakthrough, presence of postprandial reflux episodes related to newly secreted acid layered on the top of the ingested meal proximal to the squamocolumnar junction (“acid pocket”), large volume of reflux, weakly acidic refluxes, esophageal hypersensitivity, CYP2C19 genotype-dependent differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of PPI, and poor adherence to prolonged treatment with PPI [15] - [19] . Also, PPI provides a more modest therapeutic gain in patients with non-erosive reflux disease as compared with those with erosive esophagitis [20] . There is a clear need for GERD therapies beyond the PPI.

Recently, antacids or alginate-antacids formulations have shown greater potential to target the acid pocket and received a more prominent role as adjuvant therapies in GERD patients [21] . The combination of PPI plus antacids or alginate-antacids has proven effective for symptomatic treatment of GERD and the accompanying symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation [22] [23] . The use of PPI and antacids (and over-the-counter acid suppressants) is a frequent option in daily practice when symptoms are not adequately controlled. However, the use of combined therapy (PPI and antacids or alginate-antacids) presents a large variability among physicians and has been scarcely evaluated [24] [25] .

Therefore, a cross-sectional study was designed to assess primary care practitioners’ views on the effectiveness of PPI as monotherapy in the control of the most common symptoms of GERD (heartburn and regurgitation), as well as to determine the level of implementation of the “combined therapy” (PPI + alginate-antacids) and the modalities of administration to achieve a better symptom control in their patients.

2. Methods

A cross-sectional survey among primary care physicians who attended the 34th Annual Congress of the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians (SEMERGEN), which was held in Málaga (Spain) from 26th to 29th September, 2012 was performed. Over a period of 2 days (27th and 28th September) and from 9:00 AM to 18:00 PM uninterruptedly, a total of 15 previously trained Congress hostesses invited participants to complete voluntarily and anonymously a questionnaire on different aspects of the GERD on an iPad. No time limit was established to complete the questionnaire.

The questionnaire was composed on 11 close-ended questions with one-choice answer, with a total of 52 items, covering general data on the frequency of patients visited because of GERD, frequency of clinical symptoms, treatment regimens for each individual symptom and different gastroesophageal diseases, reasons for the use of the combination of PPI and alginate-antacids to relief individual symptoms and in the treatment of different gastroesophageal disease, and regimens for the use of alginate-antacids. Details of the questionnaire are shown in Table 1.

The results obtained for each completed questionnaire were sent via the Internet to a local server installed in the exhibition stand of the Almirall pharmaceutical company, which was the sponsor of the study. Results were periodically updated on real-time and charts were displayed in a Power Point presentation running on a screen at the stand, which in turn encouraged physicians to participate in the survey.

A descriptive analysis was undertaken.

3. Results

Of a total of 3196 registered attendees to the 2012 SEMERGEN congress, 1491 (46.6%) agreed to participate in the survey and completed the questionnaire. Around 50% of physicians (755 out of 1491) reported that they visited an average between 11 and 30 patients with gastroesophageal conditions per month. However, 235 physicians (15.8%) reported an average of more than 50 patients per month.

Table 2 shows the frequency of each individual symptom and gastroesophageal diseases as the primary reason for consultation. Among physicians reporting that 1% - 10% of their consultations were related to gastroesophageal symptoms, regurgitation was the most frequent complain (53.8%) followed by heartburn (23.9%) and distention (22.1%). When physicians reported that 11% - 20% of their consultations were related to gastroesophageal symptoms, distention was the most frequent symptom (31.1%) followed by heartburn (29.6%) and regurgitation (26.7). In the group of physicians reporting that 21% - 30% of their consultations were related to gastroesophageal symptoms, distention was the most frequent (29.2%) followed by heartburn (26.6%) and regurgitation (12.9%). Finally, among physicians reporting that >30% of their consultations were related to gastroesophageal symptoms, heartburn (19%) and distention (16.4%) were the most frequent.

In relation with gastroesophageal diseases, among physicians reporting that 1% - 10% of their consultations were related to gastroesophageal diseases, the most common gastroesophageal diseases were erosive GERD (67%), peptic ulcer disease (58%), infection by Helicobacter pylori (48%), and nonerosive GERD and non-ste- roidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)―induced gastropathy in 34.3% and 34.1% respectively. Among primary care physicians who reported visiting 21% - 30% and >30% of patients because of gastroesophageal diseases, non-ulcer dyspepsia was the most frequent condition, accounting for 30.7% and 22.1% of the diseases, respectively.

A total of 93.5% of physicians considered that some of their patients with gastroesophageal symptoms treated with PPI as monotherapy would remain symptomatic (heartburn and/or regurgitation). As shown in Figure 1, 39.8% of physicians referred the persistence of heartburn, 38.6% the persistence of regurgitation, and 43.5% the persistence of epigastric pain in more than 25% of their patients treated only with PPI.

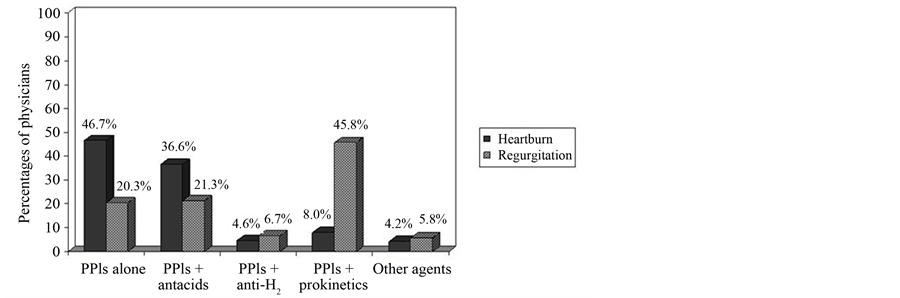

Data regarding treatment of heartburn and regurgitation are shown in Figure 2. The most common medications were PPI as monotherapy for the treatment of heartburn (46.7% of cases) and the combination of PPI and prokinetics for the treatment of regurgitation (45.8% of cases). The combined treatment of PPI and alginate-an- tacids was used by 36.6% and 21.3% of physicians for treating heartburn and regurgitation, respectively. Also, nonerosive GERD were treated with PPI as monotherapy in 61.7% of cases and with PPI combined with alginate-antacids in 17.2%. Erosive GERD (esophagitis) was treated with the combination of PPI and alginate-an- tacids in 32.1% of cases, PPI alone in 24.1%, and PPI in association with prokinetics in 18.8%. In patients with peptic ulcer, 35.7% of physicians usually used PPI alone and 25.6% the combined treatment (PPI + alginate- antacids).

Table 1. Details of the questionnaire on the management of patients with gastroesophageal diseases with combined therapy (PPI and alginate-antacids).

GE: gastroesophageal; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 2. Reasons for the selection of combined treatment (PPI + alginate-antacids) in the treatment of heartburn, regurgitation and different and gastroesophageal diseases reported by 1491 primary care physicians.

Data expressed as numbers and percentages in parenthesis.

Figure 1. Percentage of primary care physicians reporting persistence of GERD symptoms in patients treated with PPI as monotherapy.

Figure 2. Medications reported by primary care physicians for the control of heartburn and regurgitation.

When physicians were asked for the reasons for using the combination of PPI and alginate-antacids (Table 2), the arguments most frequently reported included a better control of symptoms (heartburn 20.9%, regurgitation 23.3%), increasing the rapidity of symptom relief (heartburn 33.6%, regurgitation 14.0%, epigastric pain 25.3%), decrease in nocturnal acid breakthrough (heartburn 14.1%, regurgitation 24.0%), and persistence of symptoms (heartburn 14.2%, regurgitation 12.6%). To avoid an increase in PPI doses was only reported by 5.9% of physicians for regurgitation and by 3.9% for heartburn. Better general control of the disease was also the most common reason for the use of PPI + alginate-antacids in all gastroesophageal disorders. Increase in the onset of action was the most frequent justification for patients with nonerosive GERD (30.3%) (Table 2).

With regard to the prescribed regimen of alginate-antacids in combination with PPI (Figure 3), the most common schedules were on demand (24.7%), every 8 h (21.1%), every 24 h (17.1%), after meals (11.9%), every 12 h (13.1%), and before bedtime (3.9%) in the case of heartburn. The most common regimen for the management of regurgitation were to use the antacid medication every 8 h (20.1%), every 12 h (16.3%), on demand and every 24 h (14.2% each), after meals (12.7%), and before bedtime (8.8%). Also, 5.8% and 8.9% of physicians did not use alginate-antacids combined with PPI for the treatment of heartburn and regurgitation, respectively. The reported regimens for the use of alginate-antacids in combined therapy for patients with nonerosive and erosive GERD is shown in Table 3. In patients with nonerosive GERD, alginate-antacids were mainly prescribed on demand (according to symptoms) and in the schedule of three times a day, whereas in patients with esophagitis, alginate-antacids were mostly used three times a day or every 12 h. Finally, 8.7% and 5.8% of the participants in the survey did not use the combined treatment (PPI + alginate-antacids).

Table 3. Regimens for alginate-antacids in the combined treatment (PPI + alginate- antacids) of nonerosive and erosive GERD reported by 1491 primary care physicians.

Data expressed as frequencies and percentages in parenthesis.

Figure 3. Prescribed regimens of alginate-antacids in combination with PPI for the treatment of heartburn and regurgitation.

4. Discussion

Acid suppression is the mainstay of therapy for GERD and PPI provide the most rapid symptomatic relief and heal esophagitis in the highest percentage of patients [23] . However, in those patients who prove refractory on a clinical basis [26] , the combination of a PPI plus alginate-antacids and lifestyle changes has been shown to be effective [21] [27] . It has been recognized that, as a general rule, primary care physicians see reflux symptoms in a wide spectrum and are responsible for assessing and treating the problem on a clinical basis. Therefore, primary care physicians can assume a wide scope of treatment options, which embrace a symptom-based approach, usually focusing on the predominant symptom. At the primary care level, PPI or a combination of alginate-ant- acid and acid suppressive therapy can be administered at the discretion of the physician, as combination therapy, which may potentially by more beneficial than acid suppressive therapy alone [20] [28] . The objective of this study was to gather information on the combined use of PPI and alginate-antacids in patients with GERD attended in the primary care setting.

An important finding of the survey was the fact that a high proportion of primary care physicians considered that patients with GERD remain symptomatic during treatment with PPI as monotherapy. A total of 53.7%, of primary care physicians manifested that from 1% to 25% of patients would continue suffering from heartburn; 54.7% of primary care physicians considered that patients would continue to suffer from regurgitation and 54.7% from epigastric pain. Also 39.8%, 38.6% and 43.2% of primary care physicians referred persistence of the symptoms in more than 25% of patients. This finding is consistent with data reported in other studies. In a separate online survey completed by 1002 physicians and 1013 GERD patients aimed to explore the satisfaction with PPI for GERD, 35.4% of GERD patients and 34.8% of physicians perceived patients as “somewhat satisfied” to “completely dissatisfied” with PPI therapy [29] . Also, over 35% of patients on once-daily and 54% of twice-daily PPI schedule indicated that therapy failed to completely relieve symptoms; patients who were highly dissatisfied were more likely to add over-the-counter (OTC) medications for supplemental control [29] . In a systematic review of patient satisfaction with medication for GERD using data from clinical trials and patient surveys published between 1966 and 2009, more than one-half of patients were satisfied with their PPI medication in trials [30] . An association between patient satisfaction and symptom resolution was found, suggesting that patient satisfaction is a useful endpoint for evaluating GERD treatment success.

Although the most common medication used for the management of heartburn and regurgitation were PPI alone, the combined treatment of PPI + alginate-antacids was used by 37% and 27% of physicians for treating heartburn and regurgitation, respectively. In nonerosive GERD, combined treatment (PPI + alginate-antacids) was used by 17% of physician and by 32% in cases of erosive GERD (esophagitis).This data are in agreement with results of other studies. In a US-community survey carried out in the area of central Massachusetts, among 617 patients who completed the survey, 71% used PPI once a day, 22.2% used twice a day, and 6.8% more than twice a day or on an as-needed basis [31] . A substantial proportion of patients in both subgroups (once a day and twice a day schedules) (42.2% and 41.6%, respectively) supplemented their prescription with other OTC or prescription GERD-related medications; among those users supplementing with OTC medications, alginate-antac- ids were the most commonly used (84.7% of the patients) [31] .

It is already well established that monotherapy with PPI fails in about 40% of GERD patients. Medical options for GERD patients with incomplete response to PPI therapy are limited. The addition of bedtime histamine-receptor antagonists (H2RA), prokinetic therapy with metoclopramide or domperidone in association with PPI or the usage of baclofen (GABAb agonist) has been recommended for patients with symptoms refractory to PPI. In recent years, importance is being given to the unbuffered acid pocket that may act as a potent reservoir for acid reflux. The need to target de acid pocket with antacid/alginate agents to improve reflux control and quality of life has been suggested by several investigators and also has addressed by a recent systematic review [32] [33] .

In the present study, better control of GERD-related symptoms, increase in the onset of action and reduction of nocturnal acid breakthrough were the three reasons most frequently reported by primary care physicians for the use of the combination of PPI and alginate-antacids. Moreover, in relation to the prescribed regimen of alginate-antacids in combination with PPI, the most common schedule was on demand (according to symptoms) especially for the management of heartburn and nonerosive esophagitis. In our study, patient-physician agreement concerning PPI treatment was not assessed. In a study of 1818 French primary care physicians and 5174 adult patients with GERD, the level of agreement was moderate or good for the presence of residual symptoms, moderate for treatment satisfaction, but poor for treatment expectations, indicating that residual symptoms are fairly common and their severity underestimated by physicians [24] . The SYMPATHY study, carried out in primary care settings in Spain also revealed that the degree of agreement between physicians and patients about the severity of symptoms was limited [25] .

In a meta-analysis of the efficacy of over-the-counter medications for symptomatic GERD, compared with the placebo response (which ranged between 37% and 64%) the relative benefit increase was up to 41% with histamine-2 receptor antagonists, 60% with alginate/antacid combinations, and 11% with alginate-antacids [34] . On the other hand, the use of alginate-antacids is considered is different clinical practice guidelines [21] [35] .

5. Conclusion

This study shows that primary care physicians participating in the survey believe that a high percentage of patients with GERD remains symptomatic during treatment with PPI as monotherapy. The use of alginate-antacids in an on-demand basis in the combined therapy (PPI + alginate-antacids) was considered as an effective option for the control of persistent disturbing symptoms in patients with GERD treated with PPI only.

Summary Points

· Spanish primary care physicians mostly considered that treatment with PPI alone was insufficient for the control of GERD symptoms.

· A total of 39.8% of physicians reported the persistence of heartburn, 38.6% the persistence of regurgitation and 43.2% the persistence of epigastric discomfort in more than 25% of their patients treated with PPI as monotherapy.

· The combined treatment of PPI + alginate-antacids was used for 37% and 21% of physicians for treating heartburn and regurgitation, respectively.

· A better control of symptoms, an increase in the onset of action and to reduce nocturnal acid breakthrough were the most frequently argued reasons for the use of PPI + alginate-antacids.

· On-demand “combined therapy” (PPI + antacid) is considered an efficient option to control reflux symptoms still troublesome in patients with PPI treatment alone.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

CMA and MRB conceived the study, participated in its design, coordination and execution, and participated in the writing of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Content’ Ed Net Communications, S.L. for writing and editorial assistance.

Source of Funding

This study was supported by Almirall (Barcelona, Spain).

References

- Boeckxstaens, G.E. (2009) Emerging Drugs for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs, 14, 481-491. http://dx.doi.org/10.1517/14728210903133807

- Dent, J., El-Serag, H.B., Wallander, M.A. and Johansson, S. (2005) Epidemiology of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Gut, 54, 710-717. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2004.051821

- El-Serag, H.B. (2007) Time Trends of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 5, 17-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.016

- Peery, A.F., Dellon, E.S., Lund, J., Crockett, S.D., McGowan, C.E., Bulsiewicz, W.J., Gangarosa, L.M., Thiny, M.T., Stizenberg, K., Morgan, D.R., Ringel, Y., Kim, H.P., Dacosta DiBonaventura, M., Carroll, C.F., Allen, J.K., Cook, S.F., Sandler, R.S., Kappelman, M.D. and Shaheen, N.J. (2012) Burden of Gastrointestinal Disease in the United States: 2012 Update. Gastroenterology, 143, 1179-1187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002

- Rosemurgy, A.S., Donn, N., Paul, H., Luberice, K. and Ross, S.B. (2011) Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Surgical Clinics of North America, 91, 1015-1029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2011.06.004

- Lenglinger, J., Riegler, M., Cosentini, E., Asari, R., Mesteri, I., Wrba, F. and Schoppmann, S.F. (2012) Review on the Annual Cancer Risk of Barrett’s Esophagus in Persons with Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Anticancer Research, 32, 5465-5473.

- Belhocine, K. and Galmiche, J.P. (2009) Epidemiology of the Complications of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Digestive Diseases, 27, 7-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000210097

- Liker, H., Hungin, A.P. and Wiklund, I. (2005) Management of Reflux Disease in Primary Care: The Patient Perspective. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 18, 393-400. http://dx.doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.18.5.393

- Tack, J., Becher, A., Mulligan, C. and Johnson, D.A. (2012) Systematic Review: The Burden of Disruptive Gastro- Oesophageal Reflux Disease on Health-Related Quality of Life. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 35, 1257- 1266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05086.x

- Kennedy, T. and Jones, R. (2000) The Prevalence of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Symptoms in a UK Population and the Consultation Behaviour of Patients with These Symptoms. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 14, 1589- 1594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00884.x

- Bruley Des Varannes, S., Marek, L., Humeau, B., Lecasble, M. and Colin, R. (2006) Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Primary Care: Prevalence, Epidemiology and Quality of Life of Patients. Gastroentérologie Clinique et Biologique, 30, 364-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0399-8320(06)73189-X

- Hungin, A.P., Hill, C. and Raghunath, A. (2009) Systematic Review: Frequency and Reasons for Consultation for Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease and Dyspepsia. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 30, 331-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04047.x

- Castell, D.O., Murray, J.A., Tutuian, R., Orlando, R.C. and Arnold, R. (2004) Review Article: The Pathophysiology of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease—Oesophageal Manifestations. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 20, 14-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02238.x

- Fass, R., Shapiro, M., Dekel, R. and Sewell, J. (2005) Systematic Review: Proton-Pump Inhibitor Failure in Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease—Where Next? Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 22, 79-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02531.x

- Dekel, R., Morse, C. and Fass, R. (2004) The Role of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease. Drugs, 64, 277-295. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200464030-00004

- Miner Jr., P.B. (2006) Review Article: Physiologic and Clinical Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors on Non-Acidic and Acidic Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 23, 25-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02802.x

- Sifrim, D. and Zerbib, F. (2012) Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Reflux Symptoms Refractory to Proton Pump Inhibitors. Gut, 61, 1340-1354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301897

- Hrelja, N. and Zerem, E. (2011) Proton Pump Inhibitors in the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Medicinski Arhiv, 65, 52-55.

- Frazzoni, M., Piccoli, M., Conigliaro, R., Manta, R., Frazzoni, L. and Melotti, G. (2013) Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease as Diagnosed by Impedance-pH Monitoring Can Be Cured by Laparoscopic Fundoplication. Surgical Endoscopy, 27, 2940-2946. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-2861-3

- Dean, B.B., Gano Jr., A.D., Knight, K., Ofman, J.J. and Fass, R. (2004) Effectiveness of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Nonerosive Reflux Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2, 656-664. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00288-5

- Tytgat, G.N., McColl, K., Tack, J., Holtmann, G., Hunt, R.H., Malfertheiner, P., Hungin, A.P. and Batchelor, H.K. (2008) New Algorithm for the Treatment of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 27, 249-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03565.x

- Dettmar, P.W., Hampson, F.C., Jain, A., Choubey, S., Little, S.L. and Baxter, T. (2006) Administration of Alginate Based Gastric Reflux Suppressant on the Bioavailability of Omeprazole. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 123, 517-524.

- DeVault, K.R. and Castell, D.O. (2005) Updated Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 100, 190-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41217.x

- Dorval, E., Rey, J.F., Soufflet, C., Halling, K. and Barthélemy, P. (2011) Perspectives on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Primary Care: The REFLEX Study of Patient-Physician Agreement. BMC Gastroenterology, 11, 25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-11-25

- Ferrús, J.A., Zapardiel, J. and Sobreviela, E., SYMPATHY I Study Group (2009) Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Primary Care Settings in Spain: SYMPATHY I Study. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 21, 1269-1278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832a7d9b

- Bell, N.J.V., Burget, D., Howden, C.W., Wilkinson, J. and Hunt, R.H. (1992) Appropriate Acid Suppression for the Management of Gastro-Oesophageal Disease. Digestion, 51, 59-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000200917

- Manabe, N., Haruma, K., Ito, M., Takahashi, N., Takasugi, H., Wada, Y., Nakata, H., Katoh, T., Miyamoto, M. and Tanaka, S. (2012) Efficacy of Adding Sodium Alginate to Omeprazole in Patients with Nonerosive Reflux Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Diseases of the Esophagus, 25, 373-380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01276.x

- Bell, N.J. and Hunt, R.H. (1992) Role of Gastric Acid Suppression in the Treatment of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease. Gut, 33, 118-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.33.1.118

- Chey, W.D., Nody, R.R. and Izat, E. (2010) Patient and Physician Satisfaction with Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Are There Opportunities for Improvement? Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 55, 3415-3422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10620-010-1209-2

- Van Zanten, S.J., Henderson, C. and Hughes, N. (2012) Patient Satisfaction with Medication for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology, 26, 196-204.

- Chey, W.D., Mody, R.R., Wu, E.Q., Chen, L., Kothari, S., Persson, B., Beaulieu, N. and Lu, M. (2009) Treatment Patterns and Symptom Control in Patients with GERD: US Community-Based Survey. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 25, 1869-1878. http://dx.doi.org/10.1185/03007990903035745

- Kahrilas, P.J., McColl, K., Fox, M., O’Rourke, L., Sifrim, D., Smout, A.J. and Boeckxstaens, G. (2013) The Acid Pocket: A Target for Treatment in Reflux Disease? American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108, 1058-1064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.132

- Katz, P.O., Gerson, L.B. and Vela, M.F. (2013) Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108, 308-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2012.444

- Tran, T., Lowry, A.M. and El-Serag, H.B. (2007) Meta-Analysis: The Efficacy of Over-the-Counter Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease Therapies. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 25, 143-153.

- Fennerty, M.B., Finke, K.B., Kushner, P.R., Peura, D.A., Record, L., Riley, L., Ruoff, G.E., Simonson, W. and Wright, W.L. (2009) Short- and Long-Term Management of Heartburn and Other Acid-Related Disorders: Development of an Algorithm for Primary Care Providers. Journal of Family Practice, 58, S1-S12.

List of Abbreviations

GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease;

OTC: over-the-counter;

PPI: proton pump inhibitors;

SEMERGEN: Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.