Open Journal of Gastroenterology

Vol.2 No.4(2012), Article ID:25055,5 pages DOI:10.4236/ojgas.2012.24031

Is there a role for colon capsule endoscopy in acute disease?

![]()

Department of Surgery, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Beth Israel Medical Center, New York, USA

Email: *mleitman@chpnet.org

Received 29 September 2012; revised 7 November 2012; accepted 19 November 2012

Keywords: Colitis; Carcinoma Colon; Polyp; Lower Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage; Capsule Endoscopy; Colonoscopy; Ulcerative Colitis; Regional Enteritis

ABSTRACT

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) was first put into clinical practice for the evaluation of the small bowel in patients presenting with a gastrointestinal bleed unsuccessfully diagnosed by upper GI endoscopy and colonoscopy. With the recent advent of new technology, there is improved visualization of the intestinal mucosa and subsequently a higher sensitivity for identification of mural pathology, as seen in many recent prospective studies. CCE has now been studied both in the US and in Europe as a modality for colon cancer screening as well as for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. When compared to conventional colonoscopy, CCE has been shown to have a sensitivity of greater than 88% for identifying 6mm colonic polyps and over 90% for 1 cm polyps. Therefore its use as a screening tool for colon cancer must be evaluated. In patients suspected to have colitis secondary to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), it has been shown to have 89% sensitivity for identifying active colonic inflammation. For higher risk patients that requiring urgent colonoscopy, CCE offers an attractive alternative with the potential for a reduced risk on iatrogenic injury. Colon capsule endoscopy may also play an important role in the diagnosis and surveillance of IBD with colonic manifestations. Colonoscopy during active severe disease is associated with an increased risk of perforation due to mucosal inflammation and friability, allowing us to consider CCE as a potentially safer alternative. CCE appears to be most useful for patients with acute lower GI bleeding, inflammatory bowel disease, colonic ischemia or other mucosal-based lesions.

1. INTRODUCTION

Capsule endoscopy was first put into clinical practice for the evaluation of the small intestine in patients presenting with occult gastrointestinal bleeding unsuccessfully diagnosed by upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. With the recent advent of new technology, the PillCam® Colon capsule endoscopy (GIVEN IMAGING LTD. Yokneam, Israel) was released in 2006 for evaluation of colonic pathology. The software and hardware has since been upgraded, allowing for better visualization of the intestinal mucosa and an improved sensitivity for the identification of mural pathology. With this better technology and sensitivity comes an increase in the breadth of application. PillCam Colon 2, the newest generation in colonic capsule endoscopy (CCE), has now been studied as a modality for colon cancer screening, as well as for the surveillance of dysplastic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease.

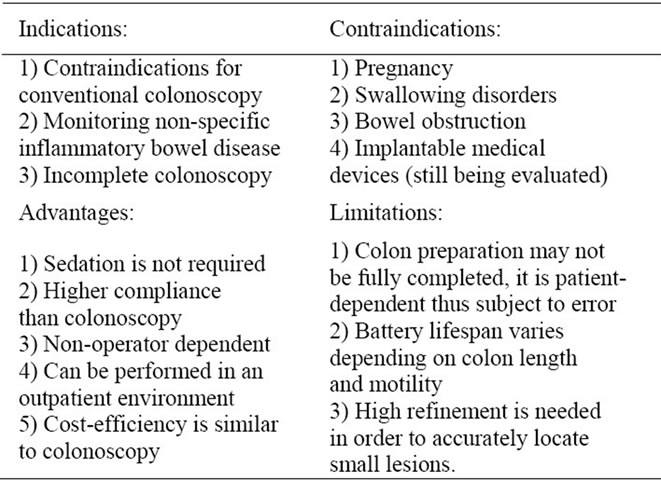

This new device has some technical differences from the small-bowel capsule in size and function. There are video-capture components on both ends of the capsule and it captures images at a rate of 4 frames per second versus 2 frames per second for the small-bowel capsule. The capsule records images for approximately 10 hours, 2 hours longer than the small-bowel device. Data are recorded via an antenna—lead array similar to that used in other capsule endoscopy procedures. CCE may be useful for patients refusing routine colonoscopy or those with contraindications to colonoscopy or when prior colonoscopy is incomplete (Table 1).

2. RISKS AND BENEFITS

The greatest risk to patients undergoing CCE is camera impaction, resulting in intestinal obstruction. Capsule retention has been reported to occur in about 1 percent [1]. Rarely, this can result in small intestinal perforation [2]. Recent studies have also shown that a reduced volume bowel preparation is just as effective as a standard preparation making allowing this imaging technique to be employed rapidly. Bowel preparation prior to CCE can even be effective without polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution [3].

On the other hand, while colonoscopy offers addi-

Table 1. Colon capsule endoscopy.

tional diagnostic and therapeutic advantages there is a real risk of perforation. In elective situations, the rate of perforation for colonoscopy is reported to be as low as 0.15 percent [4]. But under emergent situations with active colonic disease, it can be considerably higher. In certain groups, even elective colonoscopy subjects patients to increased risk for perforation. It has been shown in retrospective studies with large patient populations that advanced patient age (>75 years), female gender, sigmoid diverticulosis and the performance of therapeutic interventions are all potential risk factors for iatrogenic injury during colonoscopy [5-7]. Other complications such as bleeding or splenic injury have also been reported to occur as a result of colonoscopy [8]. It is therefore important to carefully consider and individualize the therapeutic risks and benefits for each potentially “high risk” patient, in light of newer and less invasive approaches.

Colon capsule endoscopy provides a safe alternative to colonoscopy in the early diagnosis of colon cancer. While it is not as sensitive as standard colonoscopy for the detection of colonic polyps, its does have some utility [9]. It does not require gas insufflation and trauma to the bowel is minimal. While fiberoptic colonoscopy remains the gold standard for the screening of the colonic mucosa, advances in technology have made CCE as good or better than contrast enhanced CT imaging [10]. It reliably detects polyps as small as 6 mm [11]. Two recent prospective studies compared the findings of CCE to that of conventional colonoscopy performed within 10 hrs after evacuation of the PillCam. There were no adverse events documented and the measured outcome data showed CCE to have a sensitivity of 84% - 89% for identifying colonic polyps up to 6mm and 88% for polyps up to 1 cm [12]. After selecting and analyzing those patients found to have neoplastic polyps biopsied on colonoscopy, CCE-2 had 90% sensitivity for 6 mm polyps and 93% sensitivity for 1 cm polyps [13].

Compared to colonoscopy, the rate of agreement with CCE was 76%; the sensitivity was 84% and the specificity 63%, positive predictive value 78%, and negative predictive value 71% [14]. Even in patients with an increased risk for perforation, this CCE has a minimal risk of complication as long as there are no signs of intestinal obstruction. Recently published studies have investigated the safety of capsule endoscopy in older patients (mean age 73) with patients with cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardiac defibrillators (AICD). No adverse outcomes or device malfunctions were noted, allowing the authors to conclude that capsule endoscopy is safe in this particular subset of the elderly population [15,16].

3. ACUTE INDICATIONS

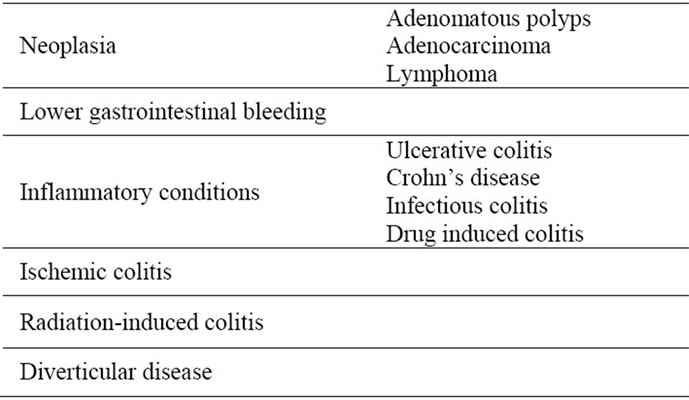

Patients with acute inflammatory colonic conditions may benefit from colonic capsule endoscopy as adequate bowel preparation may be difficult and the risk of complication from conventional colonoscopy may be slightly higher. Other diagnostic modalities such as contrastenhanced GI series, CT or MRI are also utilized but may not yield sufficient mucosal detail. Conditions for which CCE has been utilized are listed in Table 2.

4. LOWER GI BLEEDING

CCE can demonstrate the site of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in 67% to 93% of patients [17,18]. However, in patients with a negative CCE, up to 35% will have another clinically significant bleed [19]. Because as many of 15% of lower gastrointestinal bleeds occur proximal to the cecum, CCE is valuable to identification of the location and etiology [20]. Capsule endoscopy can provide information on the entire GI tract; the procedure requires no sedation and is well tolerated. However, because one cannot obtain a biopsy or precisely localize a lesion it cannot replace colonoscopy and other diagnostic studies such as nuclear scintigraphy or angiography. Also, it may provide false-positive and false-negative findings due to its patient movement and the low-resolu-

Table 2. Conditions for which colon capsule endoscopy has been shown to have clinical application.

tion images that it takes [21].

5. INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

CCE offers a safe and effective way to provide highresolution diagnostic images of the colonic mucosa with acute bowel disease while minimizing the risk of complication. Capsule endoscopy may provide useful information in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Two recent studies reviewed the overall incidence of iatrogenic colonoscopy perforation in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are at a statistically significant increased risk of colonic perforation when compared to the general population (1% vs. 0.6%). In addition, these patients are frequently on steroids, which further increases the risk iatrogenic injury [22,23]. A recent prospective, multi-center study accrued 100 patients who were suspected or known to have ulcerative colitis and evaluated the accuracy of CCE in assessing colonic inflammation when compared to convention colonoscopy. CCE was found to have a high sensitivity (89%) and positive predictive value (93%) for identifying active colonic mucosal inflammation without the occurrence of any serious adverse events [24]. Monitoring the extent of ulcerative colitis also impacts on the prognosis as patients. Those with proctitis or left-sided colitis have a better prognosis than have extensive involvement of the colon. The extent of disease also determines the beginning and frequency of surveillance for colorectal cancer, which might also be another indication for CCE [25].

The ability to distinguish Crohn’s disease from indeterminate or ulcerative colitis using CCE would be desirable and the presence of proximal small intestinal inflammatory changes would suggest Crohn’s disease. Zhao, et al, found that about 6 percent of patients previously diagnosed with ulcerative colitis actually had inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBDU), which could be managed differently. However, studies have shown that the results of CCE may be limited [26]. In addition, one has to be cautious in using CCE for patients with active regional enteritis as perforation of the small intestine has been reported [27]. CCE is commonly utilized to distinguish ulcerative colitis form other etiologies of colitis such as infectious colitis, drug induced colitis, vascular induced ischemic colitis, radiation-induced colitis, or neoplastic disease. It also facilitates the evaluation of the effects of treatment or for the diagnosis of recurrence after surgery [28]. CCE may also be helpful in patients with ulcerative colitis with unexplained anemia or abdominal symptoms. It seems reasonable to perform CCE in patients with ulcerative colitis who experience atypical symptoms or have medically refractory disease, if there are no contraindications [29]. CCE has also been used with good success in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease [30].

6. MUCOSAL ISCHEMIA

It may be helpful in distinguishing intestinal ischemia due to vascular etiologies from other causes as long as there are no signs of mechanical obstruction and there is evidence of peristaltic activity [31].

7. MUCOSAL LESIONS OF THE COLON

CCE has been used to evaluate patients with colonic lymphoma [32]. Colonic findings are also noted in patients undergoing evaluation of the small intestine using capsule endoscopy. In one study, colonic abnormalities were noted in nine percent of patients. This included cecal angiodysplasia, carcinoma, polyp, colon ulcerations with histological diagnosis of Crohn’s colitis and amebic colitis [33]. The use of CCE as an adjunct when colonoscopy was incomplete has also been demonstrated limited success [24]. CCE has also been utilized to diagnose radiation-induced colitis [34].

8. SUMMARY

Capsule colon endoscopy, with its recent technological improvements, has become a reliable, safe, minimally invasive modality for the identification of colonic pathology. While CCE has advanced our ability to obtain diagnostic non-invasive imaging of the colonic mucosa, the data thus far suggests that it has limited application. Colonoscopy remains the most effective method for diagnosing and prescribing treatment for colonic disease. Thus far, CCE has limited application to inspection of the proximal small intestine, examining the colonic mucosa in patients who cannot have colonoscopy or those in whom colonoscopy was unsuccessful. Its greatest application is in patients with lower GI bleeding, inflammatory bowel disease, colonic ischemia or other mucosalbased lesions. This technology has provided a great advance and a new tool. The application still needs to be further examined before it is universally applied.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Bandorski, D., Lotterer, E., Hartmann, D., Jakobs, R., Brück, M., Hoeltgen, R., Wieczorek, M., Brock, A., de Rossi, T. and Keuchel, M. (2011) Capsule endoscopy in patients with cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators—A retrospective multicenter investigation. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 20, 33-37.

- De Palma, G.D., Masone, S., Persico, M., Siciliano, S., Salvatori, F., Maione, F., Esposito, D. and Persico, G. (2012) Capsule impaction presenting as acute small bowel perforation: A cases series. Journal of Medical Case Reports, 6, 121. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-6-121

- Kakugawa, Y., Saito, Y. and Saito, S. (2012) New reduced volume preparation regimen in colon capsule endoscopy. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 18, 2092- 2098. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2092

- Lohsiriwat, V., Sujarittanakarn, S., Akaraviputh, T., Lertakyamanee, N., Lohsiriwat, D. and Kachinthorn, U. (2009) What are the risk factors of colonoscopic perforation? BMC Gastroenterology, 9, 71. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-9-71

- Arora, G., Mannalithara, A., Singh, G., Gerson, L.B. and Triadafilopoulos, G. (2009) Risk of perforation from a colonoscopy in adults: A large population-based study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 69, 654-664. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.008

- Anderson, M.L., Pasha, T.M. and Leighton, J.A. (2000) Endoscopic perforation of the colon: Lessons from a 10- year study. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 95, 3418-3422. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03356.x

- Lalor, P.F. and Mann, B.D. (2007) Splenic rupture after colonoscopy. Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons, 11, 151-156.

- Ghevariya, V., Kevorkian, N., Asarian, A., Anand, S. and Krishnaiah, M. (2011) Splenic injury from colonoscopy: A review and management guidelines. Southern Medical Journal, 104, 515-520. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31821e9283

- Van Gossum, A., Munoz-Navas, M. and Fernandez-Urien, I. (2009) Capsule Endoscopy versus Colonoscopy for the Detection of Polyps and Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 361, 264-270. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0806347

- Kolligs, F.T. (2012) Screening for colorectal cancer: Current evidence and novel developments. Radiologe, 52, 504-510. doi:10.1007/s00117-011-2281-0

- Spada, C., De Vincentis, F. and Cesaro, P. (2012) Accuracy and safety of second-generation PillCam COLON capsule for colorectal polyp detection. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology, 5, 173-178.

- Eliakim, R., Yassin, K., Niv, Y., Metzger, Y., Lachter, J., Gal, E., et al. (2009) Prospective multicenter performance evaluation of the second-generation colon capsule compared with colonoscopy. Endoscopy, 41, 1026-1031. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1215360

- Spada, C., Hassan, C., Munoz-Navas, M., Neuhaus, H., Deviere, J., Fockens, P. et al. (2011) Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 74, 581-589. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1125

- Herrerías-Gutiérrez, J.M., Argüelles-Arias, F., Caunedo- Álvarez, A., San-Juan-Acosta, M., Romero-Vázquez, J., García-Montes, J.M. and Pellicer-Bautista, F. (2011) PillCamColon Capsule for the study of colonic pathology in clinical practice. Study of agreement with colonoscopy. Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas, 103, 69- 75. doi:10.4321/S1130-01082011000200004

- Sung, J., Ho, K.Y., Chiu, H.M., Ching, J., Travis, S. and Peled, R. (2012) The use of Pillcam Colon in assessing mucosal inflammation in ulcerative colitis: A multicenter study. Endoscopy, 44, 754-758. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1309819

- Cuschieri, J.R., Osman, M.N., Wong, R.C., Chak, A. and Isenberg, G.A. (2012) Small bowel capsule endoscopy in patients with cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators: Outcome analysis using telemetry review. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 4, 87-93. doi:10.4253/wjge.v4.i3.87

- Carretero, C., Fernandez-Urien, I. and Betes, M. (2008) Role of videocapsule endoscopy for gastrointestinal bleeding. World Journal of Gastrointestinal, 14, 5261-5264. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.5261

- Lecleire, S., Iwanicki-Caron, I., Di-Fiore, A., Elie, C., Alhameedi, R., Ramirez, S., Hervé, S., Ben-Soussan, E., Ducrotté, P. and Antonietti, M. (2012) Yield and impact of emergency capsule enteroscopy in severe obscureovert gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy, 44, 337-342. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1291614

- Park, J.J., Cheon, J.H., Kim, H.M. and Park, H. (2010) Negative capsule endoscopy without subsequent enteroscopy does not predict lower long-term rebleeding rates in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 71, 990-997. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.009

- Chen, X., Ran, Z.-H. and Tong, J.-L. (2007) A metaanalysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with small bowel diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 13, 4372- 4378.

- Strate, L.L. (2010) Editorial: Urgent colonoscopy in lower GI bleeding: Not so fast. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 105, 2643-2645. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.401

- Calabrese, C., Liguori, G., Gionchetti, P., Rizzello, F., Laureti, S., Simone, M.P., Poggioli, G. and Campieri, M. (2011) Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: Single centre experience of capsule endoscopy. Internal and Emergency Medicine, Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s11739-011-0699-z

- Navaneethan, U., Parasa, S., Venkatesh, P.G., Trikudanathan, G. and Shen, B. (2011) Prevalence and risk factors for colonic perforation during colonoscopy in hospitalizedinflammatory bowel disease patients. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, 5, 189-195. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2010.12.005

- Riccioni, M.E., Urgesi, R. and Cianci, R. (2012) Colon capsule endoscopy: Advantages, limitations and expectations. Which novelties? World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 4, 99-107.

- Zhou, N., Chen, W.X., Chen, S.H., Xu, C.F. and Li, Y.M. (2011) Inflammatory bowel disease unclassified. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B, 12, 280-286. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1000172

- Lopes, S., Figueiredo, P. and Portela, F. (2010) Capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease type unclassified and indeterminate colitis serologically negative. Inflammatory Bowel Disease, 16, 1663-1668.

- Parikh, D.A., Parikh, J.A. and Albers, G.C. (2009) Acute small bowel perforation after wireless capsule endoscopy in a patient with Crohn’s disease: A case report. Cases Journal, 2, 7607. doi:10.4076/1757-1626-2-7607

- Rameshshanker, R. and Arebi, N. (2012) Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease when and why. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 4, 201-211. doi:10.4253/wjge.v4.i6.201

- Redondo-Cerezo, E. (2010) Role of wireless capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2, 179-185.

- Taddio, A., Simonini, G., Lionetti, P., Lepore, L., Martelossi, S., Ventura, A. and Cimaz, R. (2011) Usefulness of wireless capsule endoscopy for detecting inflammatory bowel disease in children presenting with arthropathy. European Journal of Pediatrics, 170, 1343-1347. doi:10.1007/s00431-011-1505-7

- Katsinelos, P., Vasiliadis, T. and Soufleris, K. (2008) Capsule endoscopy findings in congenital afibrinogenemia-associated angiopathy. VASA, 37, 383-385. doi:10.1024/0301-1526.37.4.383

- Beaton, C., Davies, M. and Beynon, J. (2012) The management of primary small bowel and colon lymphoma— A review. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 27, 555-563. doi:10.1007/s00384-011-1309-2

- Rana, S.S., Bhasin, D.K. and Singh, K. (2011) Colonic lesions in patients undergoing small bowel capsule endoscopy. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 26, 699-702. doi:10.1007/s00384-011-1167-y

- Hatoum, O.A., Binion, D.G. and Phillips, S.A. (2005) Radiation induced small bowel “web” formation is associated with acquired microvascular dysfunction. Gut, 54, 1797-1800. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.073734

NOTES

*Corresponding author.