Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics

Vol.03 No.03(2015), Article ID:54906,14 pages

10.4236/jamp.2015.33043

Motion of Nonholonomous Rheonomous Systems in the Lagrangian Formalism

F. Talamucci

DIMAI, Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica “Ulisse Dini”, Università Degli Studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy

Email: federico.talamucci@math.unifi.it

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 4 March 2015; accepted 19 March 2015; published 23 March 2015

ABSTRACT

The main purpose of the paper consists in illustrating a procedure for expressing the equations of motion for a general time-dependent constrained system. Constraints are both of geometrical and differential type. The use of quasi-velocities as variables of the mathematical problem opens the possibility of incorporating some remarkable and classic cases of equations of motion. Afterwards, the scheme of equations is implemented for a pair of substantial examples, which are presented in a double version, acting either as a scleronomic system and as a rheonomic system.

Keywords:

Nonholonomous Systems, Rheonomic Constraints, Quasi-Velocites, Appell and Boltzmann-Hamel Equations

1. Introduction

Nonholonomous systems are beyond a doubt more and more considered, mainly in view of the important implementations they exhibit for mechanical models.

From the mathematical point of view, the draft of the equations for such systems commonly matches the introduction of the quasi-velocities and, starting from the Euler-Poincaré equations [1] , several sets of equations have been formulated.

The time-dependent case is probably more disregarded in literature: we direct here our attention especially to rheonomic systems, admitting the holonomic and nonholonomic constraints and the applied forces to depend explicitly on time.

The nonholonomous restrictions are assumed to be linear, so that the equations of motion can be written in the linear space of the admissible displacements of the system, eliminating the Lagrangian multipliers connected to the constraints.

If on the one hand the use of quasi-velocities formally complicates calculations, on the other hand the final form of the system allows computing the equations merely by means of a list of particular matrices, once the Lagrangian function has been written and the quasi-velocities have been chosen.

We pay attention to keep separated the various contributions to the mobility of the system; the customary stationary case can be easily recovered from the general equations we will write.

An energy balance-type equation, which will be proposed in terms of the quasi-velocities, affirms the conservation of the energy in the full stationary case and shows the contributions of the different terms in the rheonomic context.

We will conclude by presenting some applications of the developed system of equations.

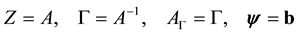

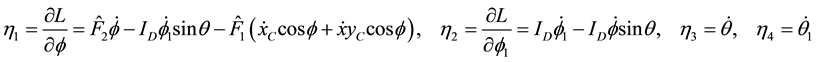

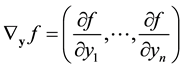

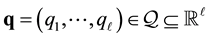

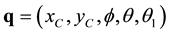

Most of the formal notation used onward is explained just below. For a given a list of variables ,

,

the operator  will compute the gradient

will compute the gradient  of a scalar funcion

of a scalar funcion , and

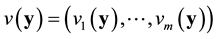

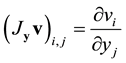

, and  calculates the

calculates the  Jacobian matrix of a vector

Jacobian matrix of a vector :

: ,

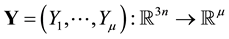

,  ,

, .

.

Anywhere, vectors are in bold type and are meant as columns: row vectors will be written by means of the

transposition symbol . Moreover,

. Moreover,  is the null column vector

is the null column vector ,

,  is the

is the  null matrix,

null matrix,

the

the

2. Modelling the System

The theoretical frame we point and expand is contained in [2] .

Let us consider a system of n point particles

where

We first make use of the

nates. The velocity of the system

differential constraints (2) which are rewritten, in terms of the Lagrangian coordinates

and

giving in each

where

where

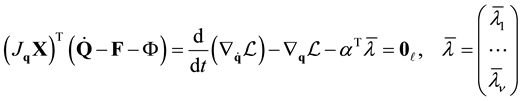

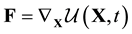

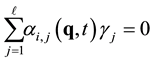

The projection of the dynamics equation on the subspace generated by the

columns of

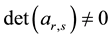

where we assumed

with

In order to improve (7), we see from (4) and (5) that

Owing to (3) and recalling (4), it is

plicitly writes

with

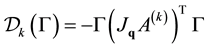

At this stage, calling

where the effect of the nonholonomic constraints (through

onomic systems is evident (in the absence of (2), say

The

Remark 2.1 Either Equation (7) or (10) can be employed not necessarily for discrete systems of point particles: once the Lagrangian coordinates have been selected and the Lagrangian function has been written, they can be the same calculated.

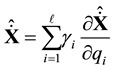

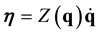

The expedience of introducing quasi-velocities (or pseudovelocities) which have to be chosen in a suitable way in order to disentangle the mathematical problem, is by custom performed in nonholonomic systems.

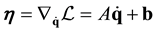

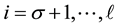

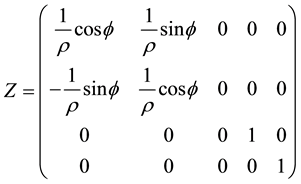

Following the adopted standpoint, the definition of the quasi-velocities steps in establishing a specific (and convenient) connection between

where

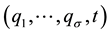

this way, each set of kinetic variables

where

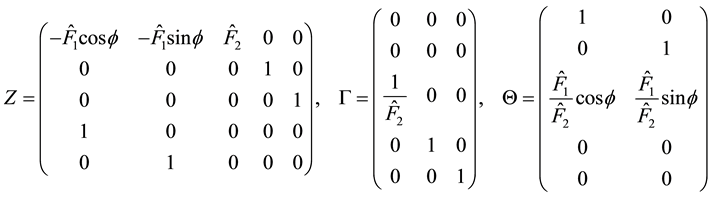

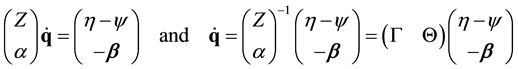

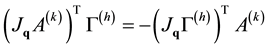

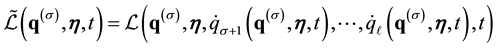

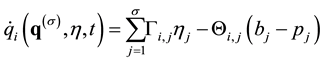

In order to express (10) as a function of the variables

and to define

where

By using the formulae (see (11))

where

we can write (10) in terms of the demanded variables (we use

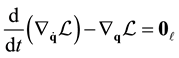

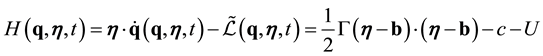

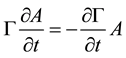

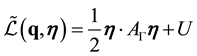

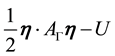

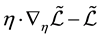

Remark 2.2 Multiplying both sides of (17) by

In the stationary circumstance

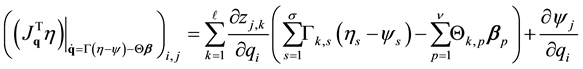

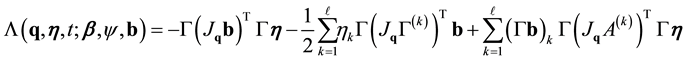

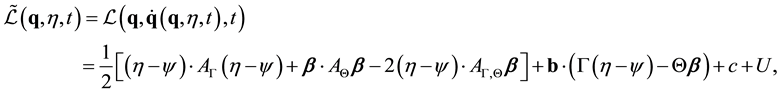

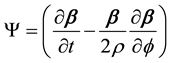

Our next step is writing (17) explicitly, sorting the terms in a suitable way: we start from the calculation

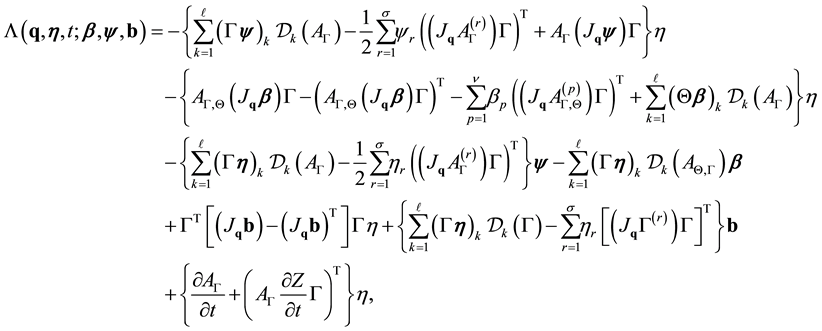

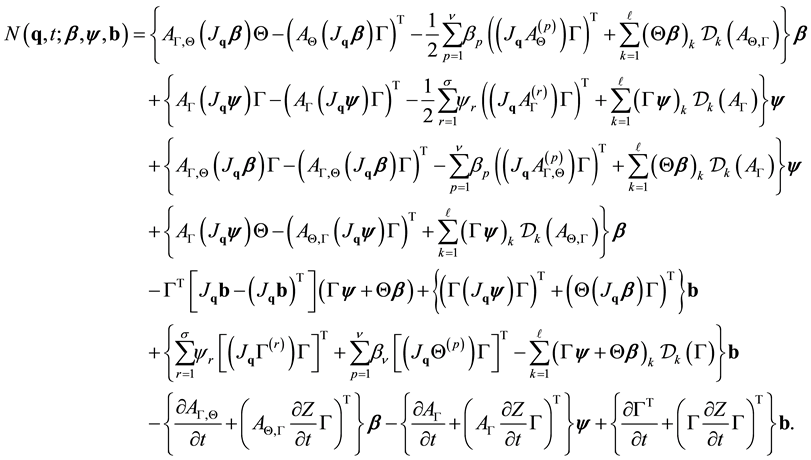

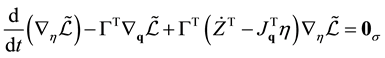

so that (17) takes the structure

Provided that

for a matrix

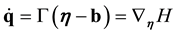

Equation (20) is sorted on the strength of the quasi-velocities

Since A is a positive-definite square matrix and

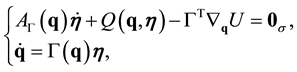

symmetric matrix. Hence, system (20) + (13) can be written in the normal form

a list of

Before commenting Equation (20), we remark that the

We see now that a certain number of significant cases are encompassed by (20):

・ merely geometric constraints, corresponding to

○ selecting

so that in (20) are written with as

thus the Lagrangian equations for geometric constraints (bearing in mind (22))

○ establishing (11) as

In this case (13) together with (20) are the Hamiltonian equations for

indeed the first one is

with

(actually from

Since

therefore (23) is

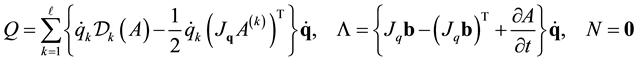

・ Stationary case, where the different contributions producing the dependence on

Conditions (24) entail

time), on the other hand (25) implies

Equation (11), if one reasonably chooses

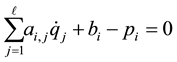

or, index by index, calling

where

Equations (27) are identified with the Boltzmann-Hamel Equations (17) for the Lagrangian function

motion, see Remark 1.2.

・ Reduced Lagrangian function for geometric constraints: in case of ν cyclic variables

(4) can play the role of the

that is

to acquire, according to (13),

only on

with

3. Some Applications

We adopt now Equation (20) in order to formulate a couple of remarkable mechanical systems, each of them in a double form, as scleronomous and rheonomous model.

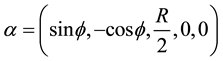

3.1. Pendulum on a Skate

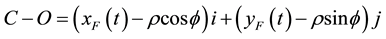

Consider a system of four points

The system represents a simple model for the motion of a bicycle, as exhibited in [5] : the mass in

Let

Since the constraints are independent and

so that

Opting for considering the segment

Figure 1. A simple model for the motion of a bicycle.

where

The only one kinetic constraint concerns with the velocity of the back “wheel”

or

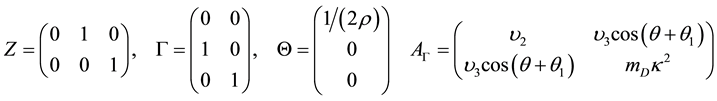

Hence

Furthermore, (12) gives

so that

By computing the first line in (26) one finds the four equations of motion

joined with the conservation of the quantity

3.2. Assignment of the Front Motion

We modify the previous model by forcing the velocity of the front “wheel” to be a known function of time (a simpler version was considered in [6] for the motion of a bike):

whereas

The constraint (30) is now

Equation (20) are written with

and correspond to

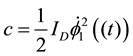

The energy balance (18) writes

with

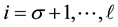

3.3. Rolling Disk with Pendulum

A different version of the model 3.1 lies in replacing the bar with a disk and obtaining the unicycle with rider model presented in [7] (see Figure 1 again, replacing the bar with the disk). The system we consider here is a disk of diameter

where

The kinematic constraint of rolling without sliding entails the zero velocity of the contact point

which is (4) with

This time

leads to

where

with

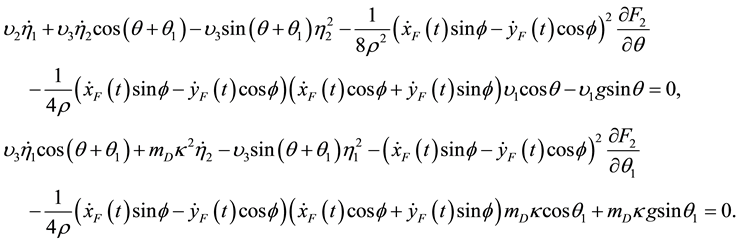

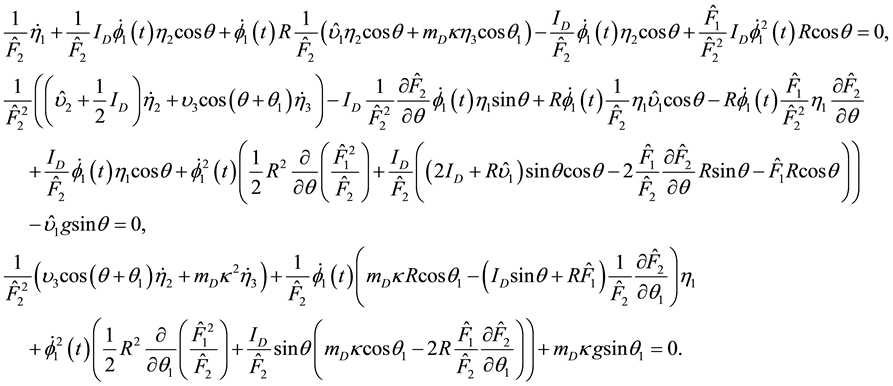

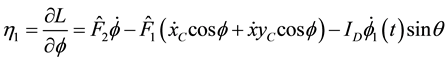

and the corresponding equations of motion (20) are

where

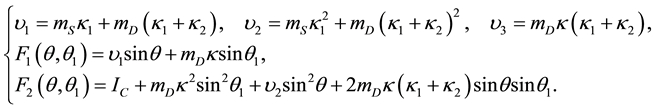

3.4. Assigned Rotational Velocity of the Disk

We finally consider the same system with the differential constraint (31), but

with

The Lagrangian fucntion (8) is written with A the same as in the previous Example 3.1, except for removing

the fourth row and the fourth column, and

Calculating the products in (15) gives

and the computation of (20) gives the three equations of motion

4. Conclusions

The paper aims at formulating a general scheme of equations for rheonomic mechanical systems exposed to either geometrical (1) and differential (2) constraints. We pay special attention to tell apart the different contributions due to the explicit dependence on time, deriving from the holonomous constrictions (via

Since the equations of motion are projected in the subspace of the velocities allowed by the constraints (both holonomous and nonholonomous), the Lagrange multipliers are absent from the equations.

The procedure proposed by (20) requires only calculation of the Jacobian matrix of vectors and the algebraic multiplication of matrices and vectors.

Making use of quasi-velocities renders the equations versatile to more than one formalism and, as it is known, the appropriate choice of them meets the target of facilitating the mathematical resolution of the problem.

The last point is part of the matters listed below and which will be dealt with in the future:

-Find an appropriate choice of the quasi-velocities in order to disentangle (20) from (13) as much as possible,

-Make use of the structure of the equations and of the properties of the various matrices involved in order to study the stability of the system,

-Take advantage of some peculiarity of the system in order to refine the set of equations and achieve information.

The latter subject is faced in [8] [9] for the stationary case by means of a robust and complex theory in connection with symmetries in nonholonomic systems.

References

- Poincaré, H. (1901) Sur une forme nouvelle des èquations de la méchanique. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sci- ences, 132, 369-371.

- Gantmacher, F.R. (1975) Lectures in Analytical Mechanics. MIR.

- Maruskin, J.M. and Bloch, A.M. (2011) The Boltzman-Hamel Equations for the Optimal Control of Mechanical Systems with Nonholonomic Constraints. International Journal of Robust and Nonlinear Control, 21, 373-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rnc.1598

- Cameron, J.M. and Book, W.J. (1997) Modeling Mechanisms with Nonholonomic Joints Using the Boltzmann-Hamel Equations. Journal International Journal of Robotics Research, 16, 47-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/027836499701600104

- Talamucci, F. (2014) The Lagrangian Method for a Basic Bicycle. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 2, 46- 60.

- Levi, M. (2014) Bike Tracks, Quasi-Magnetic Forces, and the Schrödinger Equation. SIAM News, 47.

- Zenkov, V., Bloch, A.M. and Mardsen, J.E. (2002) Stabilization of the Unicycle with Rider. Systems and Control Letters, 46, 293-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6911(01)00187-6

- Bloch, A.M., Krishnaprasad, P.S., Mardsen, J.E. and Murray, R. (1996) Nonholonomic Mechanical Systems with Sym- metry. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 136, 21-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02199365

- Bloch, A.M., Mardsen, J.E. and Zenkov, D.V. (2009) Quasivelocities and Symmetries in Non-Holonomic Systems. Dy- namical Systems, 24, 187-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14689360802609344