Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Vol.4 No.3(2014), Article

ID:48701,8

pages

DOI:10.4236/ojml.2014.43034

Exploring the Non-Symmetry of Word Derivation in Chinese-English Translation—“Wenming” for “Civilization”

Fei Deng1, Li Zhang2, Xu Wen3

1The Research Institute of Chinese Language and Documents, the Southwest University, Chongqing City, China 2The School of Foreign Languages, Southwest University of Political Science and Law, Chongqing City, China

3Foreign Language College, the Southwest University, Chongqing City, China

Email: dengfei2345@sina.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 May 2014; revised 30 June 2014; accepted 12 July 2014

ABSTRACT

The western thoughts have brought many new ideas to China in 19th century, and influenced the words’ meanings of Chinese words system. The Chinese-English translated terms and their different derivations bridge the gap between different cultures. The scholar translated English word “civilization” into Chinese word “wenming”. “Wenming” is derived from “wen” and “ming”. “Wen” means “People feel and experience the nature by heart, and then painting and describing things, at last, one can obtain knowledge through this process”. “Ming” means “based on wen, people are conducted to the correct direction, and become enlightened and civilized”. “Civilization” is derived from “civil”. And “civil”, “civis”, “civitas” and “civilitas” have the same word origin. The radical factors of the meaning of the word “civilization” are “make” and “development”. They focused on the “town” and “city”, namely, the process of cumulating wealth and remolding the nature through human being intervening in nature actively. The different word derivations between “wenming” and “civilization” disclose the differences of the location and culture when the modern thought of civilization was pervading the whole world. At the same time, with the semantic developing of “wenming”, it has the similar concept connotation with “civilization”, so it displays the compatible property and makes it possible for translation between two language units.

Keywords:Word Derivation, Translation, Civilization, Wenming, Difference, Compatible

1. The Connotation of “Civilization”

The western thoughts have brought many new ideas to China, and new meanings to Chinese words system. Chinese-English translated terms, on the one hand, has built up a bridge for us to learn foreign cultures, and on the other hand, we can get to know people’s psychological expectations of recognizing, accepting, and transforming outside thoughts. This paper aims at probing into the derivation differences between “wenming” and “civilization”, and expects to figure out the heterogeneous characteristics of “wenming” both in Chinese and western cultures.

Elias (1998) believes the word “civilization” has emerged from the mid-18th century to the late 18th century, and has been widely used in European intellectual circle at the beginning of 19th century. Guizot (1993) states that: “It seems there are two elements included in the fact called ‘civilization’, which can only exist under the two circumstances—its existence relies on two conditions—it is manifested through the two signs: social progress and individual progress; improvement of social policy, and expansion of human’s intelligence and ability.” He mentions that, in addition, “The two elements of civilization, which are intelligent development and social development, are co-related firmly.” The perfection of civilization does not only lie in their combination, but also in their synchronism, and the width, the degree of convenience, and the speed through their mutual stimulation. Liu (2011) said: “The emergence and the use of the concept and sense of ‘civilization’ in Europe are not only a linguistic and academic issue, but also a social matter. Speech is a mirror to the reality, and the changes of language reflect the progress of the society at the time, and the changes of people’s mentality who live in the society. Thus, the widely using of the word ‘civilization’ in Europe at the beginning of 19th century, is a demonstration of the period of great prosperity of quick social development and overseas expansion, motivated by the British Industrial Revolution and French Revolution, and is also a proud self representation of European people based on the progresses just mentioned.” That means, “civilization” defined by Guizot emphasizes social and individual development, and material and spiritual progress, which is in accordance with generated experiences of social and economic development and crazy overseas expansion at the time, and demonstrates the ideology of imperialism.

The verbal form of “civilization” is “civilize” (civilize). Hornby (1997) defined it as “cause sb/sth to improve from a primitive stage of human society to a more developed one”. Hornby (1989) defined it as “bring from a savage or ignorant condition to a higher one (by giving education in methods of government, moral teaching, etc.)”, and Pearsall (2004) defined it as “bring to an advanced stage of human social development”. Although there are some minor differences in the three definitions, they all cover three elements: cause/bring, primitive stage/savage or ignorant condition, and a more developed human society/higher condition/an advanced stage. And it is unignorable as well that there is a complement—“by giving education in methods of government, moral teaching, etc.” in the current edition. This could be further elaborated from the following aspects:

The verb meaning of “cause” in the 4th edition is “be the cause of something; make happen”, and the verb meaning of “bring” is “come carrying something of accompanied by somebody”, and its extended usage “bring to” means “cause something or somebody to be in a certain state or position”. Thus, word “civilize” puts emphasis on the concept of “make happen”, which demonstrates that it focuses on the effect of external force, and the differences between the initiative party and passive party, for instance, who is the initiative party and who is the passive one. It might not be seen between human society and the nature, but exist among different ethnic groups and races, and between the strong and disadvantaged people with different ideologies. The process of human civilization is the process that society develops from a low, primitive and uncivilized stage to a high and advanced stage by external force. The external force is from education, and the core content of education is the way of governing and managing society and moral instructions. It is believed that the center of “civilize” is discipline, correction and improvement. The meaning of “civilization” is “1) becoming or making somebody civilized; 2) a) (esp. advanced) state of human social development; b) culture and way of life of a people, nation or period regarded as a stage in the development of organized society”, and “make” and “development” are key words.

The word root of “civilization” is “civil”, which is cognate with the Latin words: civis, civitas and civilitas. So the new edition defines “civil” as “of or relating to ordinary citizens”, and “citizen” as “an inhabitant of a town or city”. Thus, the core meaning of “civilization” focuses on the rise of town and the essential improvement of people’s life style in the first place, and then the extended meaning “courteous and polite”, people’s gracious good manners and cares. In the Middle Ages’ Latin, the social meaning of “civilitas” has been expanded. Alighieri (1985) refers “the biggest complicated social unit” as “humana civilitas”.

1560, French scholars began to use “civilite”, the modern meaning of “civilization”, instead of “police”, which indicated the complex social revolution process of human behaviors, legal and social system. Febvre (1973) explained the usage of “civilization”, for the special need of 18th century’s ideological circle, as the evolution process of people’s behaviors and social development from a lower uncivilized stage to a more advanced educated stage; create a word to state that “rationality does not only exist in the fields of constitution and governmental administration, but also is expanding and playing a dominating role in the fields of morality and thoughts”. According to this, it can be easily drawn that “civilization” comes from the changes of people’s life style, and then causes the changes of people’s thinking mode and system. Surely, the former and the latter are inseparable. The origin of civilization focuses on the concentration of population and the rise of town. After the English Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution, as the establishment of capitalist world system and the expansion of outward colonization, the meaning of civilization is marked with Europe-centrism, and “civilized country” and “uncivilized country” have been separated.

There are plenty of researches on the process of communicating western “civilization” to China. It is widely recognized that “wenming” in the modern Chinese is from the Japanese-coined Chinese, Fukuzawa (2002) used the following terms, such as “civilization”, “civilized”, “education”. Fukuzawa Yoshi (1875: 30) elaborated that “wenming” is called “civilization” in English. Therefore, it is for some time that “civilization” is used as the equivalent term of “wenming” in Japanese-coined Chinese. Wang (2001) supports the idea that “wenming” is from Japanese-coined Chinese. It provides a new meaning of the existed expression of ancient Chinese, of which the connotation originates from the western “civilization”.

Additionally, China opened to the world earlier than Japan, so China had an earlier access to the western learning. Illustrated Annals of Overseas Countries by Wen Yuan and Brief Introduction of the World Over by Xu Ji-she were once recognized as the enlightenment works to learn the world by Japanese intellectual circle. Chinese scholars learned the word “civilization” earlier than Japanese scholars, but they translated it into “education”, “cultured”, and some other words. Fang (1999, 2004) believes translating “wenming” into “civilization” is more or less influenced by Japanese thoughts. However, how much the influence is, especially on the cognition and development of the concept, and the question that “where the concept of modern civilization comes from” could be more complicated than expectation, but one thing is for sure that it is from “Japan” and also from “the western world”. To some extent, the local factors play a very important part in spreading the concept of western civilization in China. He states that “if we focuses on the point that what word could be translated into ‘civilization’, or what is the equivalence of ‘civilization’, the way using ‘wenming’ as the Chinese equivalence of ‘civilization’ could happen even 60 years earlier.” Some Japanese and Korean Scholars believe that Liang Qichao firstly used the English word “civilization” in Lun Zhongguo Yi Jiangqiu Falv Zhi Xue, and Liu Wenming believes Huang Zunxian is the one who firstly used “civilization” in Riben Zashi Shi in 1879, but Liang made more elaboration and influence. All in all, western concept “civilization” is earlier than Japanese-coined Chinese term “wenming” being introduced into China.

2. Interpreting the Meanings of Chinese Character “Wen” in Ancient Writing

In Chinese language, “wenming” consists of two Chinese characters. One Chinese character is “wen”, and the other is “ming”. These two Chinese characters emerged early. We can see them in Oracle-Bone Inscriptions in ancient Chinese Shang Dynasty dated from B. C. 16th century to B. C. 11th century, then we can see them in Bronze Inscriptions in ancient Chinese Zhou Dynasty dated from c. 11th century to 256 BC. Here, we talk about the Chinese character “wen”.

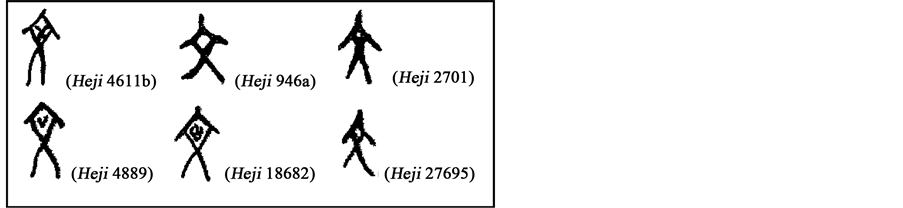

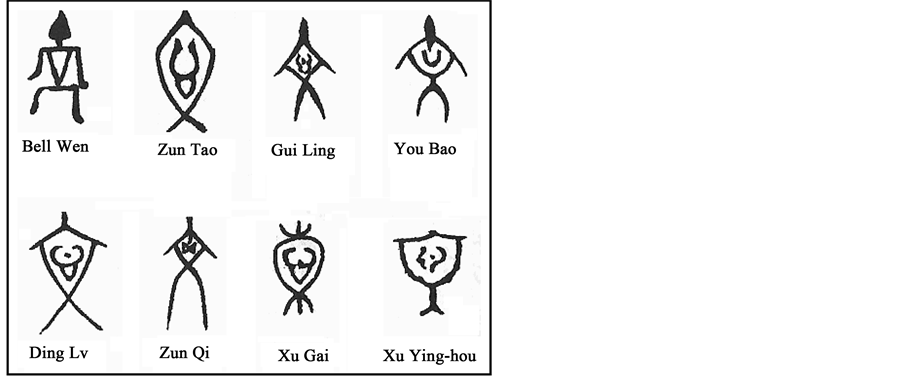

From Figure 1 and Figure 2, we can see that “Wen” sometimes consists of one part, and sometimes consists of two parts. There are a few opinions about the meanings of Chinese character “wen”. Section Wen of Shuowen Jiezi said that “wen” means to draw in the way of crossing, and Du Yu-cai, great researcher in Chinese Qing Dynasty who studied Shuowen Jiezi (说文解字), (1981: 425) added notes to it and said that “wen” means to draw pictures using the crossing lines. Xu (1988), Zhu (1962), Yan (1961) did further study of “wen” in Oracle-Bone Inscriptions, and said that the figure of Chinese character “wen” like a front standing person whose chest was decorated or curved with various pictures, so they considered that the meanings of Chinese character “wen” derived from the ancient person’s tattoo. These viewpoints can be supported by the literature proofs from ancient China.

(1) (a) Chinese literature: Chapter Wang Zhi of Li Ji (《礼记•王制》) said: Dongfang yue Yi, pifa wenshen, you bu huoshi zhe yi (东方越夷,披发文身,有不火食者矣).

Figure 1. “wen” in Oracle-bone inscriptions (See: Guo Mo-ruo & Hu Hou-xuan, 1978-1983. The Collections of the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions (甲骨文合集)—Heji).

Figure 2. “wen” in Bronze Inscriptions (See: Gao & Tu (2008)).

(b) Word-to-word translation: The oriental calls People Yi, wear one’s hair down, make tattoo, and eat raw food.

(c) Idiomatic translation: The People living in the Oriental were called People Yi. They wore their hair down, making tattoo, and eating raw food.

Zheng Xuan added notes to “wen” and said that “wen” means “making tattoo, and dying the body with red and green colors”.

(2) (a) Chinese literature: The chapter Aigong Shisan Nian of Guliang Zhuan (《谷梁传•哀公十三年》) said:Wu, Yidi zhi guo ye, zhufa wenshen (吴,夷狄之国也,祝发文身).

(b) Word-to-word translation: Nation Wu, savage people, cut one’s hair, make tattoo.

(c) Idiomatic translation: Nation Wu which has savage people, who cut their hair, and making tattoo.

Fan (1980) added notes to “wenshen” and said that “wen” means to curve, to make tattoo on their bodies with various decorations and to dye with red and green colors in order to avoid the evil dragons.

All in all, this kind of viewpoint believes that the meanings of Chinese character “wen” is to curve people’s body with various decorative patterns and dye with red and green colors, so all things or shapes in nature which have different colors and figures can be called “wen”.

From Chinese character “wen” in Oracle-Bone Inscriptions and Bronze Inscriptions, we can see a few variant figures on people’s chests, but the most important and the repeatedly-emerged figure is the heart-shape. So Wu Qi-chang and Xu Jin-xiong have raised some new opinions about the meanings of Chinese character “wen”, and they believed that it had something with ancient sacrificing.

Wu (1959) said that the meanings of Chinese character “wen” indicate the subject who would be sacrificed to when someone is dead. And Xu (2009) believed that the meanings of Chinese character “wen” disclose when human beings are dead, people will cut on their chests to let the blood flow into the ground in the ceremony of sacrificing. An ancient people believed that the Spirit never dies, and it lives with nature. It lives in the heart because it beating all long. It lives on the blood, so when human beings are dead, the Spirit should return to nature, and it can find another life form. Of course, this kind of viewpoint has some present anthropological evidences from Africa and South Pacific islands. This caused the heart-like shape become the main sign on the chest. Just as Lin (1986) said it can indicate the mental property when people curve the heart-like shape on the huge chest.

However, the meanings of Chinese character “wen” related to the primitive ideas about subtle relationship between human beings and the nature. It disclosed that human beings are a part of the nature, and human beings must be adapting to the nature from birth to death.

3. Interpreting the Meanings of Chinese Character “Ming” in Ancient Writing

Like Chinese character “wen”, we can see “ming” in Oracle-Bone Inscriptions and Bronze Inscriptions.

From Figure 3 and Figure 4, we can see that Chinese character “ming” consists of two parts. Section Ming of Shuowen Jiezi (说文解字) said that the meaning of “ming” is to shine. Duan (1981) added notes to it and said that one part is “window”. So, it is obvious that one part of “ming” is the shape of “window”, and the other is the shape of “moon”. Xu (1988) believed that meanings of Chinese character “ming” indicated that moonlight is passing through the window. Zhang (1957, 1959) considered that “ming” is a record-time term which was used by people in ancient Chinese Shang Dynasty, and it referred to the time starting-point of one day.

Based on the shape of “ming” and the meaning interpreting, the meanings of Chinese character “ming” related to moonlight shining through the window. The light drives away the black and people can see something clear in the long distance.

4. Interpreting the Meanings of “Wenming” in Language Literature of Ancient China

In Oracle-Bone Inscriptions and Bronze Inscriptions, we only see single Chinese character of “wenming”, but we can see “wen” and “ming” used together in Xian Qin Dynasty.

(3) (a) Chinese literature: Chapter Qian of Yi (《易•乾》) said:Jian long zai tian, tianxia wenming (见龙在田, 天下文明).

(b) Word-to-word translation: See dragon in the shy, whole nation shinning.

Figure 3. “ming” in Oracle-bone inscriptions (See: Guo Mo-ruo & Hu Hou-xuan, 1978-1983. The Collections of the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions—Heji).

Figure 4. “ming” in Bronze Inscriptions (See: Gao & Tu (2008)).

(c) Idiomatic translation: If dragon can be seen flying in the sky, it indicates that whole nation will be shinning with clear and happy scene.

Kong (1980) added notes to it and said: “the meanings of ‘tianxia wenming’ disclosed when the Spring is coming back, the temperature rising, the plants growing, the animals running happy, so the nature takes on clear figures, shinning with crystal pictures”.

In Example (3), “wenming” means “clear figures and shinning pictures”.

(4) (a) Chinese literature: Chapter Mingyi of Yi (《易•明夷》) said: nei wenming er wai roushun (内文明而外柔顺).

(b) Word-to-word translation: Inner good insight, but the outer gentle and agreeable.

(c) Idiomatic translation: One should have good insight when treating the inner, and to be gentle and agreeable when treating the outer.

(5) (a) Chinese literature: Dengyu biography of Houhan Shu (《后汉书•邓禹传》) said: Yu nei wenming, du xing chunbei, shimu zhixiao (禹内文明,笃行淳备,事母至孝).

(b) Word-to-word translation: Deng Yu, in the heart enlightened and good insight, politely act, carefully act, treat mother very well.

(c) Idiomatic translation: Deng Yu was enlightened and had good insight, acting politely and carefully, treating his mother well.

In Examples (4) and (5), “wenming” means “to have good insight and to be enlightened”.

(6) (a) Chinese literature: Chapter Shundian of Shangshu (《尚书•舜典》) said: jun zhe wenming, wen jian yun sai (濬哲文明,温恭允塞).

(b) Word-to-word translation: wisdom and virtue, enlightened and modest.

(c) Idiomatic translation: one had wisdom and virtue, and one was enlightened and modest.

Kong Ying-da added notes to it and said: “It is ‘wen’ that one has wide and great knowledge, and it is ‘ming’ that the sun sheds light in all directions”.

(7) (a) Chinese literature: Chaper Lvli zhi of Songshu (《宋书•律历志上》) said: shiyi junzi fan qing yi he zhi, guang yue yi cheng jiao, gu neng qing shen er wenming, qisheng er hua shen (是以君子反情以和志,广乐以成教,故能情深而文明,气盛而化神).

(b) Word-to-word translation: so gentlemen express feelings to suit spirit, enjoy music to educate people, so deep feeling, virtue and enlightenment, act perfectly, ideal condition.

(c) Idiomatic translation: a gentleman can express his feelings to suit his spirits, to enjoy music to educate persons, so he can have deep feelings, having virtue and enlightenments, and at last, he can act perfectly in an ideal condition.

In Examples (6) and (7), “wenming” means “to have good virtues and to have enlightenments”.

(8) (a) Chinese literature: He Huangyun Biao (《贺黄云表》) written by Du guang-yuan, a poet in ancient Chinese Qianshu Dynasty, said: rou yuansu yi wenming, she xiongnu yi wulve (柔远俗以文明,摄凶奴以武略).

(b) Word-to-word translation: invite the remote people using culture and education, control the evil people using military force.

(c) Idiomatic translation: we should invite the remote people to come through using cultural and educational communication, and we should get the evil people under control using military force.

(9) (a) Chinese literature: Section Gaotang Chengshou of Pipa Ji (《琵琶记•高堂称寿》), written by Gao Ming in ancient Chinese Ming Dynasty, said: bao jingshi zhi qicai, dang wenming zhi shengshi (抱经济之奇才,当文明之盛世).

(b) Word-to-word translation: embrace govern nation great capability and knowledge, suit culture and education flourishing age.

(c) Idiomatic translation: if one has great capability to govern nation, one can suit the flourishing age of culture and education which is far away from the savage age.

In Examples (8) and (9), “wenming” means “culture and education which is far away from the savage age”.

All in all, in Oracle-Bone Inscriptions and Bronze Inscriptions, we can see Chinese characters “wen” and “ming” in ancient writing respectively, but we can see “wen” and “ming” used together in Xian Qin Dynasty, and the meanings of “wenming” in ancient chinese language derived from “wen” and “ming”.

5. The Transition of “Wenming” in Chinese Language

We can see that “wenming” consists of two words in ancient Chinese language. “Wen” expresses the various and decorative phenomena in the nature, and extending from this meaning, it is a signature of infinitive knowledge that people master through inmost experiencing and reabsorbing into the nature. And extending from it, “wen” becomes a kind of inner virtue self-cultivation which can surpass the common people, and can educate people far away from the savage condition. “ming” means ‘to drive away the black, and make people see light’. Extending from this meaning, it means “people can improve themselves through obtaining ‘wen’ educated by gentlemen. With the help of this process, people gradually go out of the savage conditions and get enlightenments.” This process is like the sun shedding light on the black places.

The semantic developing process of “wenming” has been interrupted because of the English word “civilization” coming into Chinese language. The early English-Chinese translator translated English word “civilization” into Chinese phrase “wenming”, so Chinese phrase “wenming” became a word “wenming”. They have the same form and structure, but the front is a phrase, and the later is a compound. And their meanings take place subtly.

(10) (a) Chinese literature: The paper Guoming Shi Da Yuanqi Lun (《国民十大元气论》), written by Liang (1999) in Chinese Qing Dynasty, said: Jin suocheng shi shiwu zhi junjie, shu bu yue taixizhe wenming zhi guo ye, yu jin wuguo, shi yu taixi ge guo xiangdeng, bi xian qiu wuguo zhi wenming, shi yu taixi wenming deng (今所称识时务之俊杰,孰不曰泰西者文明之国也,欲进吾国,使与泰西各国相等,必先求进吾国之文明,使与泰西文明相等).

(b) Word-to-word translation: now so-called know about the ongoing circumstance outstanding talents, anyone not talk about the civilized western, want to improve our country, make it comparing the civilized westerns equal, must first make our country civilization, make it comparing the civilized westerns equal.

(c) Idiomatic translation: The present outstanding talents who know about the ongoing circumstance of the world talk about the civilized western, and if our country wants to share the same equal status with the civilized westerns, our country must have the same level of civilization as the civilized westerns.

(11) (a) Chinese literature: The poem Fenshi Die Qianyun (《愤时叠前韵》), written by Qiu Jin in Chinese Qing Dynasty, said: Wenming zhongzi yi mengya, hao zhen jingshen ai suihua (文明种子已萌芽,好振精神爱岁华).

(b) Word-to-word translation: civilization seeds have sprouted, growing up spiritedly; absorb the nutrition from the nature.

(c) Idiomatic translation: the seeds of civilization have sprouted, absorbing the nutrition from the nature and growing up spiritedly.

It is certain that “wenming” in the paper and poem written by Liang Qi-chao and Qiu Jin referred to the meanings of the English word “civilization”. They differed from “wenming” in tradition sense of ancient Chinese language. Although “wenming” and “civilization” have different word derivation, the latest extending meanings of “wenming” in ancient Chinese language and “civilization” share the similar concept connotation, so the new word “wenming” in Chinese language is perfect combination between traditional derivation and foreign meanings.

6. Conclusions

In ancient Chinese language, “wenming” and “civilization” do not share with the same semantic derivation, namely, they have non-symmetry word derivation. “civilization” came from “civil”. “Civil” shared the same word derivation with words “civis”, “civitas” and “civilitas” in Latin. “Civil” means “of or relating to ordinary citizens”, and “citizen” means “an inhabitant of a town or city”. So, the core word source of “civil” is “citizen” or “town”. The radical factors of the meaning of the word “civilization” are “make” and “development”. They focused on the “town” and “city”, namely, the process of cumulating wealth and remolding the nature through human being intervening in nature actively.

But the source of “wenming” stress to experience the nature, to cultivate the inner world. With the help of this process, one can have enlightenments and knowledge, so one can improve ordinary people, and make them far away from the savage condition. The different word derivations between “wenming” and “civilization” disclose the differences of the location and culture when the modern thought of civilization was pervading the whole world, at the same time, with the semantic developing of “wenming”, it has the similar concept connotation with “civilization”, so it displays the compatible property and makes it possible for translation between two language units.

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the following research projects: Research on the time category in the Oracle-bone inscriptions in ancient Chinese Shang dynasty (Supported by national funds for social science). Project No. 13XYY017. Research on the Semantic Domain Difference of Time Construction and Its Prototype in the Oracle Inscriptions (supported by Chinese Postdoctoral Especial Funds), Project No. 2014T70841. Research on the different expressions of the time category in the Oracle-bone inscriptions in ancient Chinese Shang dynasty (Supported by Chongqing city’s postdoctoral funds), project No. XM201359.

References

- Alighieri, D. (1985). De Monarchia (On World Government), Translated by Zhu Hong Based on the Edition of the Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., New York, 1957.

- Duan, Y. C. (1981). The Times of the Qing Dynasty, Annotation to Shuowen Jiezi (说文解字注). Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Literature Press,

- Elias, N. (1998). The Process of Civilization—Research on the Society Source and Psychology Source of Civilization (Volume 1). Translated by Wang Pei-li Based on Suhrkamp 1976’s Edition, Peking: Sanlian Press.

- Fan, N. (1980). The Jin Dynasty, Collections of Annotation to Guliang, Annotation to Thirteen Ancient Classics. Peking: Zhonghua Press,

- Fang, W. G. (1999). On Changing in Ideology of Wenming and Wenhua in Modern China (论近现代中国“文明”、“文化”观的嬗变). Shilin, Volume 4.

- Fang, W.-G. (2004). On Ideology of Wenming and Wenhua in Modern China—on the Value Converting and Concept Changing (近现代中国“文明”、“文化”观—论价值转换及概念嬗变). Www of Academic Terms in Modern China, 2014. 3.12.

- Febvre, L. (1973). Civilisation: Evolution of a Word and a Group of Ideas. In Burke, P. (Ed.), A New Kind of History: From the Writing of Febvre. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Fukuzawa, Y. (2002). The Western Things. In Shunsaku, N. (Ed.), The Collections of Fukuzawa Yukichi, Volume 1 (pp. 94-98). Tokyo: Qingying University Press.

- Gao, M., & Tu, B. K. (2008). Classifying Collection of Ancient Characters (古文字类编). Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Literature Press.

- Guizot (1993). General History of Civilization in Europe—From the Roman Empire’s Failure, Volume 1. Translated by Yuan Zhi, &Yi Xin, Peking: Commerce Press.

- Hornby, A. S. (1989). Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English with Chinese Translation. Peking: Commerce Press. Hong Kong: The Oxford University Press.

- Hornby, A. S. (1997). Oxford Advanced Learner’s English-Chinese Dictionary. Peking: Commerce Press. Hong Kong: The Oxford University Press.

- Kong, Y. D. (1980). The Tang Dynasty, Annotation to Ancient Book Zhouyi, Annotation to Ancient Book Shangshu, Annotation to Thirteen Ancient Classics. Peking: Zhonghua Press.

- Liang, Q. C. (1999). The Times of the Republic of China, on Ten Kinds of Spirits in National (国民十大元气论), The Collected Works of Liang Qichao, Volume 1. In Zhang, P. X. (Ed.), Peking: Peking Press.

- Lin, Y. (1986). Brief Review of the Research on the Ancient Characters (古文字研究简论). Changchun: Jinlin University Press.

- Liu, W. M. (2011). Review of the Spreading and Localization of European Civilization Views in Japan and China (欧洲“文明”观念向日本、中国的传播及其本土化述评). Research on History, 3.

- Pearsall, J. (2004). The Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Peking: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Wang, L. (2001). The Manuscript of Chinese History (汉语史稿). Peking: Zhonghua Press, 520.

- Wu, Q. C. (1959). Interpretation of the Oracle-Bone Inscription in the Shang Dynasty in Yin Ruins. Taipei: Yiwen Press.

- Xu, J. X. (2009). Concise Philology of Chinese Characters (简明中国文字学). Peking: Zhonghua Press.

- Xu, Z. S. (1988). The Oracle-Bone Dictionary (甲骨文字典). Chengdu: Sichuan Dictionary Press.

- Yan, Y. P. (1961). To Interpret the Character Wen. Chinese Characters, 3, 1009-1010.

- Zhang, B. Q. (1957, 1959). Interpretation of the No.3 Collections of Ancient Characters in Yin Ruins (殷墟文字丙编考释). Taipei: The Institute of Chinese Language and History.

- Zhu, F. F. (1962). Collected Interpretation of Yin-Zhou Character (殷周文字集释), Volume 2, 67-68. Peking: Zhonghua Press.