Open Journal of Business and Management

Vol.05 No.04(2017), Article ID:78572,19 pages

10.4236/ojbm.2017.54051

Predicting the Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour in Zambia, Africa

Bruce Mwiya1, Yong Wang2, Chanda Shikaputo1, Bernadette Kaulungombe1, Maidah Kayekesi1

1School of Business, Copperbelt University, Kitwe, Zambia

2Business School, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, UK

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: July 27, 2017; Accepted: August 18, 2017; Published: August 21, 2017

ABSTRACT

The current paper contributes to the entrepreneurial intention (EI) literature by applying the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) in a developing African country with unique socio-economic and cultural context. Thus it examines the influence of social norms, personal attitudes and perceived behavioural control on business start-up intentions. Based on a quantitative approach, primary survey data were collected from 306 final year undergraduate students at a public university. The data were analyzed using correlation and hierarchical regression techniques. Controlling for age, gender and field of study, the findings indicate that each of the attitudinal antecedents is significantly positively related to EI, with an overall R2 = 0.543. For scholars, enterprise support practitioners and policy makers, the study shows that the TPB can be used to understand how to promote business start-up in developing countries with socio-economic and cultural contexts which are mostly different from developed countries where the subject is heavily researched. Specifically, mechanisms to develop entrepreneurial capabilities among citizens, improve societal norms and individual attitudes toward entrepreneurship would significantly promote entrepreneurship. The study also makes a valuable contribution to the under-researched context of Zambia and African entrepreneurship.

Keywords:

Entrepreneurial Intention, Theory of Planned Behaviour, University, Students, Zambia, Africa

1. Introduction

Extant literature suggests that there has been heightened debate on entrepreneurial intention (EI) and its antecedents and yet there is limited evidence from developing countries [1] [2] [3] [4] . While multi-nation samples are believed to allow for broad understanding of entrepreneurial phenomena in developing countries [5] , it is equally important to give attention to research in individual countries as this may provide an in-depth understanding of applicability of theories in diverse socio-economic and cultural contexts [4] . Reference [6] contends that the phase of economic development has implications for EI. African developing countries, though characterised as middle-income economies [6] [7] , are unique in the sense that they all have different historical and economic characteristics making them researchable as stand-alone units.

Generally, entrepreneurship has been recognised as a vital contributor to the economic development of a country through employment generation [8] , broadened tax revenue base, innovation, competition and the consequent increase in choices for consumers [9] . In this context, governments both in developed and developing countries are now pressured into considering mechanisms to improve the level of entrepreneurial activity in their own countries [10] . It is mainly believed that university education enhances graduate employability. To the contrary, in developing nations in Africa university education is no longer an assurance of guaranteed employment especially immediately after graduation [11] . For instance, in Zambia, 72% of the unemployed graduates are youths below the age of 35 [12] . This is typical of sub-Saharan Africa where there is a youth bulge in the population and it connotes negative returns to governments’ investments in education. This is also a loss of potential contributors to economic development [13] and can lead to increase in vices associated with idleness, deprivation and poverty [14] [15] .

One of the solutions to this challenge is for various stakeholders to promote graduate entrepreneurship i.e. graduates’ involvement in business start-ups, management and growth [16] [17] . Literature indicates that, compared to non- graduate-owned firms, graduate-owned firms in the UK were more likely to have not only younger owners but also intellectual property and high growth potential [18] . With respect to external resources, such firms were more likely to have received beneficial business advice and support from informal and formal sources including trade associations, government business services, customers and suppliers. They were also more likely to have public procurement customers. In Zambia, graduates who owned businesses were more likely to be employers (26%) than non-graduates at 1% [12] . This implies that promoting graduate entrepreneurship has the potential to generate high growth firms which can result in more employment generation.

In Zambia, the proportion of graduates participating in entrepreneurship is estimated at 16% compared to 46% for non-graduates [12] . This paper makes a significant contribution to literature by isolating Zambia, an African developing economy with its uncommon characteristics and exploring factors that influence graduate entrepreneurship. Culturally, Zambia has a collectivist culture with high uncertainty avoidance and low masculinity [19] [20] . It would be insightful to explore how determinants of start-up intention play out in such a context [21] . In the literature, entrepreneurial intention (EI) has emerged as a critical factor in determining who is more likely to start up a business. Indeed EI is a measure of entrepreneurial potential in society because individuals who express an intention are more likely to engage in that behaviour than those who do not [22] [23] . Based on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), intention to start-up a business is a function of perceived favourable social norms, personal attitudes as well as perceived entrepreneurial capability [24] .

Nevertheless, prior studies on EI that have been conducted in both developed and developing nations neglect some contexts. For example, EI has been explored among Russian students [25] ; Polish students [26] ; Spanish and Taiwanese students [27] ; and, Chinese students [28] . There are also other studies conducted in other European countries [29] [30] , in the United States of America [31] and in Asia and the Middle East [28] [32] [33] . Other studies have been conducted across nations, for example, reference [34] conducted a study on EI across 12 countries while [35] studied six nations. According to Reference [5] , these studies found differences in EI across nations and none of them have gone as far as investigating whether or not these differences are a result of differences in the development status or indeed culture [5] [34] [35] of the studied nations. Scholars are quick to point out that since the environmental contexts are different between developing and developed nations, differences will arise in EI and their antecedents. All these studies have limitations in terms of generalisability of research conclusions to other contexts especially developing nations in Africa. There are also a few studies on EI among university students in South Africa [36] [37] , Ethiopia [38] , and Uganda [39] . Although a few African countries have been studied, it is important to understand that African countries are not homogeneous. They have major socio-economic and cultural differences thereby justifying the study on Zambia as a stand-alone nation in order to capture these unique characteristics [40] .

In light of the foregoing, this study has two objectives. Firstly, it seeks to contribute to entrepreneurial intention literature by applying the theory of planned behaviour in an under-research developing country context of Zambia, Africa. Secondly, it explores the influence of each of the attitudinal antecedents of intention on business start-up decision with a view to identifying the basis for promoting graduate entrepreneurship in Zambia. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 undertakes literature review and develops hypotheses; Section 3 highlights the research methods before research findings and discussion are presented in Section 4; and lastly, the conclusions, limitations and contributions of the research are provided in Section 5.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Entrepreneurial Intention

Most of the studies on entrepreneurial intention (EI) have used the theory of planned behaviour i.e. TPB [41] which was developed following the theory of reasoned action (TRA) on beliefs, attitudes and intentions as determinants of human behaviour [42] [43] . The TPB indicates that intention is the best predictor of an individual’s behaviour. This is because “intention is an indication of how hard an individual is willing to try, of how much of an effort he or she is planning to exert, in order to perform the behaviour” [41] p. 188. As a general rule, the stronger the intention to engage in a behaviour, the more likely it will lead to performance.

In the context of entrepreneurship, intention would reflect an individual’s willingness or plan to engage in new venture creation or growth [44] . It is a self- acknowledged conviction by an individual that he or she will and plans to start a new venture at some point in future [45] . This means that while intention represents a future course of action, it is not simply an expectation or prediction of future actions but a proactive commitment. The major premise for the TPB is that most goal-directed behaviours are planned and therefore preceded by intention. Nevertheless, a few scholars indicate that there may be exceptions to this premise, for example, when an individual drifts into starting up a business after stumbling on an opportunity serendipitously [44] [46] [47] . On the whole, intentionality is a state of mind directing a person’s attention, experience and actions toward a specific goal/path. Scholars indicate that intention is the most immediate antecedent of a given behaviour [48] [49] . Even though some entrepreneurial ideas begin with inspiration, intention is required for sustained attention and action. Entrepreneurs’ intentions guide their goal setting, communication, commitment, organisation and other efforts in the entrepreneurial process [50] [51] .

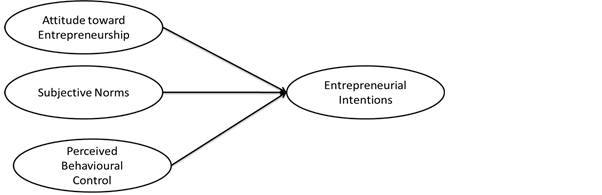

Indeed, prior research in Europe [22] [52] , the United States of America [31] , the Middle East and Asia [33] [53] , indicates that individuals with intentions to start-up a business are more likely to actually start a business than those without. Hitherto there remains a paucity of research on EI in the Zambian context. This has limited the generalisability of prior research conclusions. Reproducibility and replicability are at the centre of science and essential to the development of knowledge in any scientific field [54] . The Academy of Management Journal (AMJ), globally one of the top most journals in business and management research, indicates that replication research is important for enhanced confidence in existing knowledge even for seemingly well understood relationships. This is especially so if a) internal or external validity issues are not yet settled for whatever reasons (e.g. limited contexts of prior research) and b) there is an empirically established relationship that should serve as a basis for broad theorising in a field or that has company-wide or public policy implications [55] [56] p. 314. This limitation in the literature notwithstanding, the big question is how does EI develop? The TPB framework posits that intention to undertake a particular behaviour, including entrepreneurship [2] , is a function of perceived favourable social subjective norms and personal attitudes towards entrepreneurship as well as perceived entrepreneurial capability in the context of manageable barriers [24] . Each one of these antecedents requires separate discussion as depicted in the research model (see Figure 1).

2.2. Attitude toward Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Intention

Reference [41] conceptualises the attitude toward a behaviour as the “degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation of the behaviour in question” (p. 188). Typically, here the individual is asking him/herself the question “do I perceive that this would be a good thing to do?” In relation to entrepreneurship, the intention of launching a new business will be influenced by how personal values and attitudes have been shaped over time. The attitude reflects the extent to which the individual regards starting a venture as a good or bad thing to do, as judged by the individual [44] .

Some scholars propose that entrepreneurial motivation is largely based on “pull” factors [57] . This means that individuals seeking independence, self-fulfilment, wealth, and other desirable outcomes are more likely to find entrepreneurship attractive [58] [59] . This is because such Individuals may believe that entrepreneurship, compared to other alternatives, offers better means for achieving these desirable outcomes [60] [61] . It is expected that individuals who find the rewards of starting and managing their own businesses attractive would not only find entrepreneurship valuable but they would also choose an entrepreneurial career. Based on final year university student samples in the USA and Turkey [31] as well as Saudi Arabia [53] , scholars find that individuals with a favourable attitude toward entrepreneurship are more likely to report a high EI. Therefore, the first hypothesis is as follows:

H1: the higher the level of personal attitude toward entrepreneurship, the higher the level of entrepreneurial intention.

2.3. Perceived Subjective Norms and Entrepreneurial Intention

Reference [41] refers to subjective norms as “the perceived social pressure to

Figure 1. Research model: antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Source: Adapted from [27] [41] .

perform or not to perform a particular behaviour” (p. 188). Essentially here, the person is asking him/herself “would people important to me consider this action as a good move?” This means that how friends, relatives or colleagues consider a particular behaviour will affect a person’s perception.

In relation to entrepreneurship, subjective norms reflect the extent to which the individual’s relevant environment (peers, family, and society) regards starting a venture as a good or bad thing to do. Based on data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, a study by [62] finds that young people with either a) a parent who is an entrepreneur or b) school peers/friends that have at least one parent who is an entrepreneur, report higher business start-up intention. Similar studies in China [28] [63] , Saudi Arabia [32] and India [64] empirically establish that individuals who perceive favourable social norms (approval) from their peers, family and friends towards entrepreneurship are more likely to intend to start-up a business. This is because the prospect of social and emotional support for one’s decision provides additional impetus to engage in such behaviour. Therefore, it is postulated as follows:

H2: subjective norms are positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

2.4. Perceived Behavioural Control and Entrepreneurial Intention

Reference [41] explains perceived behavioural control (PBC) as “the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour of interest … and it is assumed to reflect past experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles” (p. 188). In essence, the person is asking him/herself the question “could I do it if I want to?” It is believed that some ability is needed for a new venture to come about [44] . When facing a specific opportunity, those with relevant education, experience or exposure may perceive themselves as more capable to exploit opportunities. This would motivate them to seize the opportunity. This resonates with expectancy theory [65] which suggests that an individual will choose (be motivated) to engage in a particular behaviour if he or she believes that not only is the outcome of those actions attractive (i.e. valence) but also if he/she expects that those actions will be followed by a given outcome i.e. expectancy. This is akin to a concept in economics that suggests that human beings are rational and so they would seek to spend resources or engage in behaviour that maximises their utility i.e. benefits.

With respect to entrepreneurship, PBC relates to the perception of technical competencies required, the financial risks, the administrative burden and the possessed resources and abilities. Based on empirical research, scholars in Spain [27] [29] , Ukraine [30] , USA and Turkey [31] , China [28] as well as Malaysia [33] establish that the higher the perceived behavioural control in relation to new venture creation, the higher the level of the business start-up intention. Perceived behavioural control would be high for individuals who feel they have the knowledge, networks and means needed to get a business going. Conversely, PBC would be lower for those who feel they lack one or more of those requirements. It is expected that individuals who not only consider themselves personally capable of starting and managing a business but also who regard entrepreneurship to be viable would choose an entrepreneurial career. Therefore, this study posits as follows:

H3: perceived behavioural control is positively correlated with entrepreneurial intention.

The antecedents of entrepreneurial intention are summarized in Figure 1.

Having developed the reasoning behind the three hypotheses reflected in the conceptual model (Figure 1), the study employed correlation and hierarchical regression analyses to test the hypotheses.

3. Methods and Measurement

This study sought to test the theory of planned behaviour in a developing African nation, Zambia. Specifically, it examines the relationships between business start-up intention and its attitudinal antecedents, namely subjective norms, attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioural control. Therefore, the study employed a quantitative survey design [66] , an approach that has been used by scholars in Saudi Arabia [32] , in Malaysia [33] as well as the USA and Turkey [31] . Based on a survey of final year university students (population 2000) at a public university in Zambia, a random sample of 323 students was required [67] . However, despite administering the questionnaire to all 323 students in the sample, only 306 responded satisfactorily. The sample size compared favourably to similar prior studies with 105 students in the USA [68] , 329 students in South Africa [37] and 61 students in Colombia [69] . Using student samples is a legitimate approach in entrepreneurship research. This is anchored on the premise that today’s university students potentially represent both tomorrow’s entrepreneurs and those who do not have any such intention of becoming entrepreneurs [31] [70] . Scholars [71] argue that by studying students, it is possible to examine the related phenomena before they happen. Particularly for final year students, the impending graduation compels them to consider career options and some may find business start-up realistic.

Based on the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) data analyses, Table 1 shows the profile of the respondents with an average age of 22.92, and this is typical of undergraduate final year students in Zambian universities [11] [72] . To take into account potential gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions [22] [73] , 57.9% of the sample represented male students and the rest female students (42.1%). Lastly, 81.5% of the respondents were business students while the rest were in non-business programmes such as mathematics, natural sciences and resources. These proportions were as a result of not only the random sampling but also the fact that business students are the majority at the public university.

Measurement Model Validity

To ensure content validity and comparison of results with prior studies [45] , the

Table 1. Respondents’ profiles.

Source: SPSS generated from survey data for this study.

construct items for the questionnaire were adopted from [29] in relation to entrepreneurial intention and its attitudinal antecedents i.e. subjective norms, attitude toward entrepreneurship and perceived behavioural control (20 items in total). To further ensure construct validity, a principal component analysis with varimax rotation [74] was executed to examine the factor structure of the theory of planned behaviour measures in entrepreneurship (see Table 2). To assess factorability of the correlation matrix, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of sampling adequacy at 0.879 was above the minimum 0.50 threshold [74] and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (Approx. Chi-Square = 2941.656, df = 190, sig. < 0.001).

Based on factor analyses, four factors with the Eigen values above 1.0 arose and they were generally consistent with prior research findings, representing the theory of planned behaviour themes of entrepreneurial intention, subjective norms, attitude towards the behaviour and perceived behavioural control [29] . These four factors altogether explained a total of 63.009% of the variance. Reliability tests for internal consistency of the respective items in the four dimensions yielded Cronbach Alpha scores above the threshold 0.7, suggesting that the constructs are reliable [74] .

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analyses

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the direction and strength of relationships among all variables. Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations of the independent variable (entrepreneurial intention), independent variables (subjective norms, attitude toward the behaviour and perceived behavioural control) as well as the control variables (gender, field of study and age). The correlations among all these variables are also presented. Relatively low correlations (all of them below 0.80), signify that multicollinearity is not a problem [74] [75] [76] . In Table 3, all the correlations are in the expected direction with respect to entrepreneurial intention (EI) and the other variables.

Table 2. Factor and reliability analyses for constructs.

Source: SPSS generated from survey data for this study.

4.2. Hierarchical Regression Analyses

In Table 4, the results of hierarchical regression are reported with entrepreneurial intention (EI) as the dependent variable. The basic EI model postulates that perceived behavioural control, attitude toward the behaviour and subjective norms are the primary determinants of business start-up intentions. In turn the EI is the best predictor of actual business start-up [52] [77] . Preliminary statistical checks in Table 4 indicate that since variance inflation factor (VIF) is less than 5 for all the independent and control variables, multicollinearity is not a

Table 3. Mean, standard deviation (SD) and correlation matrix.

Source: SPSS generated from survey data for this study.

Table 4. Hierarchical regression analyses.

Source: SPSS generated from survey data for this study.

concern [74] . All the regression coefficients are in the expected direction.

Firstly, model 1 shows the base model with only control variables age, gender and field of study. The control variables make a combined significant contribution with an adjusted R2 of 7.5% and R of 0.291, representing a combined small effect size [74] . Individually, while gender is significant, age and field of study are not significant. Prior research indicates that older individuals are more likely to have higher self-efficacy and perceived behavioural control and EI because of employment experience [22] . In the current sample, the effect of age, while positive, was not statistically significant. For the field of study, perhaps non-signi- ficance may be due to the fact that the sample was dominated by business students (81.5%). The result for gender entails that males generally have higher intention to start a business than females. In relation to entrepreneurship, prior research indicates that one plausible explanation for this relatively lower zeal and self-efficacy is that women have less early career experience, social support and fewer role models than their male counterparts [73] [78] .

Secondly, in model 2, besides the control variables, subjective norms are introduced and a significant combined effect occurs (R2 change of 3% from 8.5% to 11.4%) with R of 0.338, representing a combined medium effect size. Individually, only gender and subjective norms each make a unique significant contribution. This means that individuals who perceive that their peers, close family members and colleagues would approve of the decision to start-up one’s own business are more likely to develop an EI. Thus hypothesis H2 is confirmed.

In model 3, besides subjective norms and the control variables, attitude towards entrepreneurship is introduced and a significant combined effect occurs (R2 change of 39% occurs from 11.4% to 50.5%) with R of 0.71, indicating a combined large effect size. Individually, only gender and personal attitude are statistically significant. This entails that those individuals who have a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship, who perceive it to be a good and attractive career path, are more likely to intend to start-up a business. Thus hypothesis H1 is confirmed.

Lastly, model 4, apart from subjective norms, personal attitude towards entrepreneurship and control variables, introduces perceived behavioural control and a significant combined effect is reported (R2 change of 3.8% occurs from 50.5% to 54.3%) with R of 0.737, representing a combined large effect size. In the multiple regression model 4, individually, only personal attitude and perceived behavioural control are statistically significant. This entails that individuals who perceive that they are capable of starting, managing and growing their own businesses are more likely to develop an EI. Thus hypothesis H3 is confirmed. Model 4 reflects all the control and independent variables’ influences on EI. Personal attitude to entrepreneurship has the largest effect (Beta = 0.556, p < 0.001), followed by perceived behavioural control (Beta = 0.231, p < 0.002) and then the rest of the non-significant variables, including subjective norms (Beta = 0.023, p > 0.05), follow.

4.3. Discussion

The findings in this study indicate that subjective norms, attitude toward entrepreneurship and perceived behavioural control are each uniquely significantly positively related with entrepreneurial intention (EI). Notwithstanding this, in a multiple regression model only perceived behavioural control and attitude to entrepreneurship are statistically significant. These findings resonate with prior studies in different cultural contexts such as Malaysia [33] , USA and Turkey [31] , Saudi Arabia [32] and Spain [29] , to mention but a few. The meaning of these results is threefold. Firstly, these findings mean that individuals who believe that their peers, friends and family would approve of their decision to start- up a business are more likely to report a high EI. This is because if an individual perceives that those in the immediate social setting would approve his/her decision, the prospect of emotional, social and other support would provide extra stimulus to attempt the entrepreneurial activity. For a largely collectivist country like Zambia, the opinions of people an individual considers important in his/her life become crucial to business start-up decisions. This finding is consistent with a few prior studies [63] [79] .

Secondly, individuals who consider the benefits and rewards of business start-up, management and growth to be valuable are more likely to report a high EI. Similarly, individuals who consider themselves capable of carrying out the tasks involved in starting, managing and growing a business are more likely to engage in the activity. This is the essence of perceived behavioural control which refers to the “perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour of interest…and it is assumed to reflect past experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles’’ [41] , p. 188. These findings have not only confirmed the conceptual model hypothesised in this paper but they have also helped to show that the theory of planned behaviour is indeed applicable in a developing and collectivist society of Zambia. Until now, there has not been a similar study in the Zambian context.

Additionally, the study has shown that in a collectivist society in which individuals place more value on their connectedness with others, their perceptions of what the influential people (i.e. family, friends and peers) in their lives think about business start-up have a positive influence on EI [63] . In contrast, for individualistic societies which place less value on their connectedness with others, their perceptions of what influential people think become less influential e.g. in Spain [29] . This result resonates with perceived subjective/social norms’ strong effects on EI in collectivist contexts and contradicts its non-significance in studies undertaken in the individualistic contexts [2] [29] .

5. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

Arising from a concern about limited generalisability of findings from prior studies due to contextual limitations, this study sought to contribute to the entrepreneurial intention (EI) literature by applying the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) in the under-researched collectivist African developing nation, Zambia. Thus, it examined the influence of social (subjective) norms, attitude toward entrepreneurship and perceived behavioural control on EI. Based on a sample of 306 final year university students from a public university, the study undertook correlation and hierarchical regression analyses.

Consistent with extant literature, the study concludes that EI is a function of perceived behavioural control, attitude to entrepreneurship and social norms [31] [32] [63] . Hitherto, there has not been a similar study in the Zambian context, thereby limiting the generalisability of prior research findings. Additionally, the study has shown that in a collectivist society in which individuals place more value on their connectedness with others, their perceptions of what the influential people (e.g., family, close friends, partners, colleagues) in their lives think about new venture creation have very significant influence on EI [63] . This result corroborates perceived subjective/social norms’ strong effect on EI in the collectivist contexts and contradicts its non-significance in studies undertaken in individualistic contexts [2] [17] .

The research findings have implications for scholars, educators, enterprise support practitioners and policy makers on how to promote entrepreneurial activity in Zambia. Firstly, the theory of planned behaviour is applicable in a developing under-researched context of Zambia for exploring factors influencing business start-up decisions. Secondly, individuals who are likely to start up their own businesses are those who perceive that starting and managing one’s own business are beneficial and attractive undertakings. Additionally, it is those individuals who perceive that such a decision would receive approval from their close families, friends and peers (social norms). This requires that educators, the media and enterprise support institutions, working with accomplished and established entrepreneurs, should increase promotional programmes to make clear the importance and the benefits of entrepreneurship at individual and national levels. This would improve perceptions of attractiveness of business start-up as a career option for university graduates.

Thirdly, the results show that individuals likely to start up a business are those who not only perceive that they are capable of performing the required entrepreneurial tasks but also perceive that the environment is favourable and supportive. This conclusion requires that educators design/redesign and deliver, with appropriate pedagogical approaches, hands on entrepreneurship education courses/modules in order to develop entrepreneurial capabilities in potential entrepreneurs. In addition, enterprise support practitioners and policy makers should design/redesign, implement and promote support programmes for start- up and fledgling businesses. This would reduce barriers and obstacles to starting, managing and growing one’s own business. In turn, this would increase perceived behavioural control, high EI and actual behaviour.

The current study had some limitations which are the basis for suggestions in relation to directions for future research. Firstly, the study was cross sectional in nature and so it would only proffer a snapshot of the research context. In future, it would be necessary to conduct a longitudinal study to understand the transition for individuals from intention to actual business start-up [52] . Secondly, the study was conducted based on a sample from a public university. In future, it would be necessary to include more universities across the country to improve generalisability of the conclusions. Lastly, future studies should attempt to include some personal background and environment variables as well, and estimate their direct and indirect influence on EI. This would help uncover where attitudes, norms and control perceptions come from [44] .

6. Contributions

The forgoing limitations notwithstanding, the study makes a key contribution. In line with prior studies, the study concludes that entrepreneurial intention (EI) is a function of perceived behavioural control, attitude to entrepreneurship and social norms [31] [32] [63] . Until now, there has been a shortage of studies in the Zambian context on EI. This has limited the generalisability of prior research conclusions. Reproducibility and replicability are at the centre of science and essential to the development of knowledge in any scientific field [54] . The Academy of Management Journal (AMJ), globally the top most journal in business and management research, indicates that replication research is important for enhanced confidence in existing knowledge even for seemingly well understood relationships. This is especially so if a) internal or external validity issues are not yet settled for whatever reasons (e.g. limited contexts of prior research) and b) there is an empirically established relationship that should serve as a basis for broad theorising in a field or that has company-wide or public policy implications [55] [56] p. 314. In helping to expand the evidence base on the antecedents of EI, this study has further shown that in a collectivist society in which individuals place more value on their connectedness with others, their perceptions of what the influential people (e.g., family, close friends, partners, colleagues) in their lives think about their new venture creation have very significant influence on their decisions [63] . This result supports perceived subjective/social norms’ strong effect on EI in collectivist contexts and contradicts its non-significance in studies undertaken in individualistic contexts [2] [17] . Thus, the study makes a valuable contribution to the under-researched context of Zambia and African entrepreneurship.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Maliwa Kabika for data entry support.

Cite this paper

Mwiya, B., Wang, Y., Shikaputo, C., Kaulungombe, B. and Kayekesi, M. (2017) Predicting the Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour in Zambia, Africa. Open Journal of Business and Management, 5, 592-610. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2017.54051

References

- 1. Kolvereid, L. (1996) Prediction of Employment Status Choice Intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 21, 47-57.

- 2. Krueger, J.R., Reilly, M. and Carsrud, A. (2000) Competing Models of Entrepreneu- rial Intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411-432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- 3. Linán, F. and Fayolle, A. (2015) A Systematic Literature Review on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Citation, Thematic Analyses, and Research Agenda. Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11, 907-933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0356-5

- 4. Nabi, G., Linán, F., Fayolle, A. and Krueger, N. (2017) The Impact of Entrepreneur- ship Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16, 277-299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026

- 5. Iakovleva, T., Kolvereid, L. and Stephan, U. (2011) Entrepreneurial Intentions in Developing and Developed Countries. Education + Training, 53, 353-370. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911111147686

- 6. Wennekers, S., Van Wennekers, A., Thurik, R. and Reynolds, P. (2005) Nascent Entrepreneurship and the Level of Economic Development. Small Business, 24, 293- 309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1994-8

- 7. World Bank (2014) Country Data for Zambia. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/zambia

- 8. Birch, D.L. (2000) The Job Generation Process, US Department of Commerce, MIT Programme on Neighbourhood and Regional Change (1979). In: Storey, D.J., Ed., Small Business: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management, Routledge, Abingdon-on-Thames, 431-465.

- 9. de Wit, G. and de Kok, J. (2014) Do Small Businesses Create More Jobs? New Evidence for Europe. Small Business Economics, 42, 283-295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9480-1

- 10. Koe, W.-L. (2016) The Relationship between Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation and Entrepreneurial Intention. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0057-8

- 11. Mwiya, B.M.K. (2014) The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on the Relationships between Institutional and Individual Factors and Entrepreneurial Intention of University Graduates: Evidence from Zambia. University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton.

- 12. CSO (2013) Zambian 2010 Census Data Reports. Central Statistical Office in Zambia, Lusaka.

- 13. Carree, M.A. and Thurik, A.R. (2010) The Impact of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth. Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research, 557-594.

- 14. Agbor, J., Taiwo, O. and Smith, J. (2012) Sub-Saharan Africa’s Youth Bulge: A Demographic Dividend or Disaster. Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2012, 2012, 9-11.

- 15. Borode, M. (2011) Higher Education and Poverty Reduction among Youth in the Sub-Saharan Africa. European Journal of Educational Studies, 3, 149-155.

- 16. Matlay, H. (2011) The Influence of Stakeholders on Developing Enterprising Graduates in UK HEIs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 17, 166-182. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551111114923

- 17. Nabi, G. and Linán, F. (2011) Graduate Entrepreneurship in the Developing World: Intentions, Education and Development. Education Training, 53, 325-334. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911111147668

- 18. Pickernell, D., Packham, G., Jones, P., Miller, C. and Thomas, B. (2011) Graduate Entrepreneurs Are Different: They Access More Resources? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 17, 183-202. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551111114932

- 19. Hofstede, G.H. (2017) What about Zamba? On Cultural Dimensions. https://geert-hofstede.com/zambia.html

- 20. Hofstede, G.H. (1984) Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work- Related Values. Abridged E. Sage Publications Inc., London.

- 21. Shneor, R. and Camg?z, S.M. (2013) The Interaction between Culture and Sex in the Formation of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25, 781-803. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.862973�

- 22. Henley, A. (2007) Entrepreneurial Aspiration and Transition into Self-Employment: Evidence from British Longitudinal Data. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 19, 253-280. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620701223080

- 23. Kelley, D.J., Singer, S. and Herrington, M.D. (2012) The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. http://www.gemconsortium.org/report

- 24. Ajzen, I. (2011) The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psycho- logy & Health, 26, 1113-1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- 25. Tkachev, A. and Kolvereid, L. (1999) Self-Employment Intentions among Russian Students. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 11, 269-280. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856299283209

- 26. Jones, P., Jones, A., Packham, G. and Miller, C. (2008) Student Attitudes towards Enterprise Education in Poland: A Positive Impact. Education + Training, 50, 597- 614. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910810909054

- 27. Linán, F. and Chen, Y.W. (2009) Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 593-617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- 28. Yang, J. (2013) The Theory of Planned Behavior and Prediction of Entrepreneurial Intention among Chinese Undergraduates. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41, 367-376.

- 29. Linán, F., Urbano, D. and Guerrero, M. (2011) Regional Variations in Entrepreneu- rial Cognitions: Start-Up Intentions of University Students in Spain. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23, 187-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620903233929

- 30. Solesvik, M.Z., Westhead, P., Kolvereid, L. and Matlay, H. (2012) Student Intentions to Become Self-Employed: The Ukrainian Context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19, 441-460. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211250153

- 31. Ozaralli, N. and Rivenburgh, N.K. (2016) Entrepreneurial Intention: Antecedents to Entrepreneurial Behavior in the U.S.A. and Turkey. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6, 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0047-x

- 32. Aloulou, W.J. (2016) Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions of Final Year Saudi Uni- versity Business Students by Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23, 1142-1164. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2016-0028

- 33. Chuah, F., Ting, H., de Run, E. and Cheah, J. (2016) Reconsidering What Entrepreneurial Intention Implies: The Evidence from Malaysian University Students. Inter- national Journal of Business and Social Science, 7, 85-98.

- 34. Engle, R.L., Dimitriadi, N., Gavidia, J.V., Schlaegel, C., Delanoe, S., Alvarado, I., et al. (2010) Entrepreneurial Intent: A Twelve-Country Evaluation of Ajzen’s Model of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16, 35-57. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551011020063

- 35. Moriano, J.A., Gorgievski, M., Laguna, M., Stephan, U. and Zarafshani, K. (2012) A Cross-Cultural Approach to Understanding Entrepreneurial Intention. Journal of Career Development, 39, 162-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845310384481

- 36. Gird, A. and Bagraim, J.J. (2008) The Theory of Planned Behaviour as Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intent amongst Final-Year University Students. South African Journal of Psychology, 38, 711-724. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630803800410

- 37. Malebana, M. (2014) The Effect of Knowledge of Entrepreneurial Support on Entrepreneurial Intention. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 20, 1020.

- 38. Gerba, D. (2012) Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business and Engineering Students in Ethiopia. African Journal of Econo- mic and Management Studies, 3, 258-277. https://doi.org/10.1108/20400701211265036

- 39. Byabashaija, W. and Katono, I. (2011) The Impact of College Entrepreneurial Education on Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Intentions to Start a Business in Uganda. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 16, 127-144. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946711001768

- 40. Choongo, P., Van Burg, E., Masurel, E., Paas, L.J. and Lungu, J. (2017) Corporate Social Responsibility Motivations in Zambian SMEs. International Review of Entre- preneurship, 15, 29-62.

- 41. Ajzen, I. (1991) The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Hu- man Decision Processes, 50, 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- 42. Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980) Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood.

- 43. Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

- 44. Davidsson, P. (2004) Researching Entrepreneurship. Springer, New York.

- 45. Thompson, E.R. (2009) Individual Entrepreneurial Intent: Construct Clarification and Development of an Internationally Reliable Metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 669-694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00321.x

- 46. Bhave, M.P. (1994) A Process Model of Entrepreneurial Venture Creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 1, 223-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90031-0

- 47. Pickering, J.F. (1981) A Behavioural Model of the Demand for Consumer Durables. Journal of Economic Psychology, 1, 59-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(81)90005-2

- 48. Bird, B. (1988) Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The Case for Intention. Acade- my of Management Review, 13, 442-453.

- 49. Zhao, H., Seibert, S.E. and Lumpkin, G.T. (2010) The Relationship of Personality to Entrepreneurial Intentions and Performance: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Management, 36, 381-404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309335187

- 50. Learned, K.E. (1992) What Happened before the Organization? A Model of Organization Formation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17, 39-49.

- 51. Rotefoss, B. and Kolvereid, L. (2005) Aspiring, Nascent and Fledgling Entrepreneurs: An Investigation of the Business Start-Up Process. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 17, 109-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620500074049

- 52. Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M. and Tornikoski, E.T. (2013) Predicting Entrepreneurial Behaviour: A Test of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Applied Economics, 45, 697-707. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.610750

- 53. Almobaireek, W.N. and Manolova, T.S. (2012) Who Wants to Be an Entrepreneur? Entrepreneurial Intentions among Saudi University Students. African Journal of Business Management, 6, 4029-4040. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.1521

- 54. Evanschitzky, H., Baumgarth, C., Hubbard, R. and Armstrong, J.S. (2007) Replication Research’s Disturbing Trend. Journal of Business Research, 60, 411-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.003

- 55. Eden, D. (2002) From the Editors: Replication, Meta-Analysis, Scientific Progress, and AMJ’s Publication Policy. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 841-846. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2002.7718946

- 56. Miller, C.C. and Bamberger, P. (2016) Exploring Emergent and Poorly Understood Phenomena in the Strangest of Places: The Footprint of Discovery in Replications, Meta-Analyses, and Null Findings. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2, 313- 319. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2016.0115

- 57. Gilad, B. and Levine, P. (1986) A Behavioural Model of Entrepreneurial Supply. Journal of Small Business Management, 24, 45-53.

- 58. Keeble, D., Bryson, J. and Wood, P. (1992) The Rise and Role of Small Service Firms in the United Kingdom. International Small Business Journal, 11, 11-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/026624269201100101

- 59. Orhan, M. and Scott, D. (2001) Why Women Enter into Entrepreneurship: An Explanatory Model. Women in Management Review, 16, 232-247. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420110395719

- 60. Segal, G., Borgia, D. and Schoenfeld, J. (2005) The Motivation to Become an Entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 11, 42-57. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550510580834

- 61. Shapero, A. and Sokol, L. (1982) The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship. In: Kent, C.A., Sexton, D.L. and Vesper, K.H., Eds., Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship, Prentice-Hall, Engelwoods, 72-90.

- 62. Falck, O., Heblich, S. and Luedemann, E. (2012) Identity and Entrepreneurship: Do School Peers Shape Entrepreneurial Intentions? Small Business Economics, 39, 39- 59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9292-5

- 63. Siu, W. and Lo, E.S. (2013) Cultural Contingency in the Cognitive Model of Entrepreneurial Intention. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37, 147-173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00462.x

- 64. Roy, R., Akhtar, F. and Das, N. (2017) Entrepreneurial Intention Among Science & Technology Students in India: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management, 13, 1-29.

- 65. Vroom, V.H. (1964) Work and Motivation. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 66. Creswell, J. (2012) Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Qualitative and Quantitative Research. 4th Edition, Pearson Education, Thousands oaks.

- 67. Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2009) Research Methods for Business Students. 5th Edition, Pearson Education, London.

- 68. Pruett, M. (2012) Entrepreneurship Education: Workshops and Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Education for Business, 87, 94-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.573594

- 69. Campo, J. (2011) Analysis of the Influence of Self-Efficacy on Entrepreneurial Intentions. Prospectiva, 9, 14-21.

- 70. Mueller, S. (2004) Gender Gaps in Potential for Entrepreneurship across Countries and Cultures. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 9, 199-220.

- 71. Krueger, J.N.F. and Carsrud, A.L. (1993) Entrepreneurial Intentions: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 5, 315- 330. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985629300000020

- 72. Mwiya, B., Bwalya, J., Siachinji, B., Sikombe, S., Chanda, H. and Chawala, M. (2017) Higher Education Quality and Student Satisfaction Nexus: Evidence from Zambia. Creative Education, 8, 1044-1068. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.87076

- 73. BarNir, A., Watson, W.E. and Hutchins, H.M. (2011) Mediation and Moderated Mediation in the Relationship among Role Models, Self-Efficacy, Entrepreneurial Career Intention, and Gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 270-297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00713.x

- 74. Pallant, J. (2016) SPSS Survival Manual?: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS Program. 6th Edition, McGraw-Hill Ediucation, London.�

- 75. Wang, Y. and Ahmed, P.K. (2009) The Moderating Effect of the Business Strategic Orientation on ECommerce Adoption: Evidence from UK Family Run SMEs. The Journal of Strategic information Systems, 18, 16-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2008.11.001

- 76. Wang, Y. (2016) Environmental Dynamism, Trust and Dynamic Capabilities of Fa- mily Businesses. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22, 643-670. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-11-2015-0234

- 77. Krueger, N. (2017) Entrepreneurial Intentions Are Dead: Long Live Entrepreneurial Intentions, Revisiting the Entrepreneurial Mind. Springer International Publishing, New York, 13-34.

- 78. Shinnar, R., Hsu, D. and Powell, B. (2014) Self-Efficacy, Entrepreneurial Intentions, and Gender: Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education Longitudinally. The International Journal of Management Education, 12, 561-570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.09.005

- 79. Shinnar, R. and Giacomin, O. (2012) Entrepreneurial Perceptions and Intentions: The Role of Gender and Culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36, 465- 493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00509.x