Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:28703,9 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.31003

Development of a career-orientation scale for public health nurses

![]()

1Department of Human Health Sciences, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan

2Department of Human Nursing, Sonoda Women’s University, Amagasaki, Japan

Email: okura.mika.2e@kyoto-u.ac.jp

Received 18 January 2013; revised 27 February 2013; accepted 5 March 2013

Keywords: Career Orientation; Development of Scale; Professionalism; Public Health Nurse; Significance of Working

ABSTRACT

Objective: The purpose of this study was to develop a career-orientation scale for public health nurses (PHNs) and to validate the scale. Methods: Self-administered questionnaires were sent to 7170 PHNs in 10 prefectures. A retest survey was sent to 252 participants. Results: The valid responses from 2003 PHNs in the first survey were analyzed for major factors by varimax rotation. The analysis resulted in five orientation factors and 19 items being selected. The cumulative contribution ratio was 46.9%, and Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was 0.863. The exact match ratio of test-retest was 59.7% (from 47.7% to 72.1% for each item and from 12.0% to 92.0% for each participant). Conclusions: The reliability and validity of this survey were confirmed; however, further research is required to confirm the reproducibility. This scale can be used as a self-assessment tool when managers need to advise their staff on career development.

1. INTRODUCTION

We are currently facing the challenge of an aging population and its tremendous effect on the social security system. Therefore, it is important to better understand the factors associated with community healthcare issues that have placed increasing burdens on public health nurses (PHNs) working in local government centers [1,2]. Recently, the public healthcare and welfare systems in Japan have markedly changed to meet repeated requests by citizens for better healthcare services [3]. In addition, because of changes in the healthcare system, the number of community healthcare professionals in each section has decreased, creating more demand for policy planning and management competency. To effectively work in such a changing environment, continuing career development has become increasingly important [4,5].

For PHN career development, it is important to offer PHNs self-career orientation that can facilitate the integration of their experiences (PHNs’ career orientation).

Previous studies have been conducted on career orientation for company workers: 1) organizational orientation and professional orientation [6,7], 2) generalist orientation and specialist orientation [8], and 3) the concept of the gradual integration of motives, values, and competencies in the personal self-concept and life-work balances that occur as the result of the interaction between individual and work environments [9,10].

However, all of these studies have focused on male employees and have established scales applicable to male employees [6-10]. Therefore, in this study, the following points were considered: 1) over 90% of Japanese PHNs are female, 2) almost all PHNs are working at local government agencies in a public organization, 3) all PHNs have a national license, 4) PHNs have no night shifts, 5) PHNs have different levels of nursing targets, and 6) the turnover rate for PHNs is much lower than the rate for hospital-based nurses. Although research has contributed to hospital-based nurses’ career development for decades [11-14] and this research is still being actively promoted [15,16], the subjects in this study are different from hospital-based nurses. Therefore, we need to know the implication of career orientation specific to PHNs.

To address these issues, we conducted a research interview [17] and a questionnaire survey based on the interview [18]. However, the following two issues remain unaddressed: 1) in spite of having been identified in the qualitative research, some PHNs’ career orientations were not collected, and 2) the subjects were confined to only two prefectures.

The aim of this study, therefore, is to develop a careerorientation scale for PHNs and to examine the reliability and validity of the scale by a larger-scale questionnaire survey.

In this study, career orientation for PHNs was defined as the result of identifying one’s area of contribution over the long term, which generated criteria for the types of work settings in which PHNs want to function. This study defined the pattern of identifying ambition and criteria for success by which one can measure oneself— the pattern of self-perceived talents, motives, and values [9,10].

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

We selected 10 prefectures from different areas of Japan; the selection was based on the number of full-time PHNs [19] and the percentage of municipal mergers in each prefecture for sampling [20]. For the first survey, the subjects included 7170 PHNs in 10 prefectures.

2.2. Data Collection

We performed two surveys. In the first survey, the selfadministered questionnaires were sent to the subjects’ workplaces by mail in May and June 2007, and the responses were collected individually.

The questionnaire for a PHN’s career orientations included 25 items that were modified from our previous qualitative and quantitative research findings [17,18]. The participants were asked to, “Answer each question about your attitude toward work, including future prospects”.

They were asked to respond using a 4-point Likert scale with descriptors ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree).

The retest survey was conducted in July and August 2007, approximately 2 months after the first survey. The subjects had provided contact details and agreed to participate in the retest survey. The retest survey comprised 25 items related to PHN career orientations and 40 items of career anchors by Schein [9,10]. The career anchors were used as external criteria because they had been used frequently in previous career-orientation research [21,22].

2.3. Data Analysis

SPSS for Windows 15.0 was used for the analysis. In this study, priority was given to ease of understanding. Subsequently, the analysis method was adopted on the condition of a normal distribution.

Descriptive statistics, correlation between items, goodpoor analysis, and item-total correlation analysis were performed. Then the exclusion of certain items was considered based on the analysis results.

Test-retest as the stability reliability was computed. Internal consistency was examined by calculating the cumulative contribution ratio and Cronbach’s coefficient alpha.

Construct validity was examined as the following choice criteria of the items: 1) factor loadings were 0.4 or more, and similarity was 0.16 or more, and 2) items that overlapped with two or more factors were exempted for the development of scale [23,24]. The major factor analysis by varimax rotation was conducted based on those selection criteria. The extracted factors were then named, connecting with the content of items. Additionally, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was examined with the “career anchors” for each factor as criterion-related validity. Further, the kappa of Cohen [25] as a measure of content validity was computed [26].

2.4. Ethical Considerations

PHNs who received the questionnaire were free to choose whether to participate in this study. Those who volunteered to participate in the retest questionnaire had provided their contact details and signed a consent form. Once data from the questionnaires had been converted to electronic form, the questionnaires were stored in a lockable cupboard. The researchers conducted the research with the approval of the Medical Ethics Committee of Kanazawa University, with which they were affiliated at the time of the study.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant Demographic Characteristics

The questionnaires were received from 2065 PHNs (28.8%) for the first survey, and 2003 (97.0%) of them provided valid responses. The retest survey was received from 253 PHNs who had agreed to participate, and 222 (93.3%) of them provided valid responses. The participant demographic characteristics from the first survey are shown in Table 1.

3.2. Item Analysis

The mean total score of 25 items related to PHN career orientations was 72.0 ± 9.40, and the mean of each item was from 2.06 to 3.52 (Table 2).

In the distribution of the items, we confirmed that no more than 75% of respondents focused on any one item. As a result of the G-P analysis, a significant difference was observed between the two groups of the upper group and lower group. One item, “There are nights when I cannot sleep worrying about what I should do for others (Item 22)” was exempted as a result of I-T correlation. Because, it was shown less than 0.3 in all other items by the item-total correlation analysis.

3.3. Examination of Construct Validity

Explanatory factor analysis was conducted on 24 items

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants.

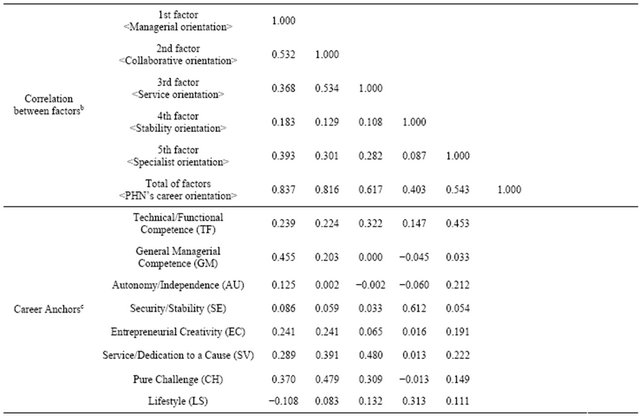

after we exempted one item found unsuitable by item analysis. As a result of conducting major factor analysis by varimax rotation based on a selection criterion, five factors consisting of 19 items were selected (Table 3). Thereafter, construct validity and reliability were performed for approximately five factors, which consisted of 19 items. The mean total score of the 19 items related to PHN career orientations was 55.4 ± 7.33 (range 23 - 76). The five factors were the subscale of the PHN career orientations.

The first factor, which was named “Managerial Orientation”, comprised six items; the second factor, “Collaborative Orientation”, comprised six items; the third factor, “Service Orientation”, consisted of two items; the fourth factor, “Stability Orientation”, included three items; and the fifth factor, “Specialist Orientation”, comprised two items.

3.4. Examination of Criterion-Related Validity

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for the “career anchors” to examine criterion-related validity. A high validity coefficient was verified for the following: Managerial Orientation and “general managerial competence” or “pure challenge”, Collaborative Orientation and “pure challenge” or “service/dedication to a cause”, Service Orientation and “service/dedication to a cause” for Specialist Orientation and “technical/function competence”, and Stability Orientation and “security/stability” or “lifestyle”. However, as for “autonomy/Independence” and “entrepreneurial creativity”, all PHNs’ career orientations were less than 0.3 of the validity coefficient (Table 3).

3.5. Examination of Reliability

Internal consistency in this study was measured with Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, which was 0.863 for the total scale and from 0.612 to 0.821 for the subscales; the cumulative contribution ratio was 46.9 (Table 3). The exact match rate of test-retest was 59.7% for the total item (from 40.3% to 63.9% for each item and from

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of PHNs’ career orientation.

Continued

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; Participants were asked, “Answer each question about your attitude toward work, including the future prospects”. aThe number and comparative percentage (%) of response to each mark. A 4-point Likert scale; with descriptors ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree); bThe mean as total of items was 59.7% (each item 47.7% - 67.1%, each participant 12.0% - 92.0%, n = 222).

12.0% to 92.0% for each participant). Further, the kappa of Cohen as a measure of content validity ranged from 0.205 to 0.406 (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Reliability and Validity of the PHN Career-Orientation Scale

A number of factors and items were appropriately selected for the PHN career-orientation scale based on the results of the factor loadings and reliability coefficients of subscales as internal consistency [27,28]. Additionally, a number of factors and items will not to have a long time for the self-assessment [23,24].

It is difficult to conclude that stability and reliability were achieved based on the exact match rate of test-retest. However, this result must be interpreted to consider the period of retest, which was conducted approximately 2 months later, and an exact individual match was not obtained.

Criterion-related validity would be nearly acceptable because the validity coefficient of the external criterion was intermediate [23,24]. However, the validity coefficient of “autonomy/independence” and “entrepreneurial creativity” was not as high. It is difficult for PHNs working in local government agencies to imagine starting a business.

4.2. Subscale of PHNs’ Career Orientation

People with Managerial Orientation have management as their ultimate goal. It is said that the demands of competency lie in a combination of the following: 1) analytical competence—to identify, analyze, and solve problems under conditions of incomplete information and uncertainty; 2) interpersonal competence—to influence, supervise, lead, manipulate, and control people at all levels toward the more effective achievement of goals; and 3) emotional competence—to be stimulated by emotional and interpersonal crisis and to exercise power without guilt or shame [9]. This orientation would be necessary for PHNs because it indicates general management and monitoring of quality in the community-nursing field, regardless of the position [5].

It is said that PHNs must establish common and empirical strategies to assess the feasibility of a new project [2]. Additionally, collaborative effects to maintain professional values across disciplines are urgently needed [29]. PHNs should have a collaborative attitude when they must address a crisis such as child abuse or elder abuse [30,31] or create a primary healthcare system [32]. Therefore, it is important for them to emphasize the process of creating new systems as advocates and behind-the-scenes supporters of people.

Service Orientation is the ability to express basic needs, talents, and values to work with others in a helping role; interpersonal competence and helping are ends in themselves rather than means to an end or result [9]. This orientation may influence PHNs’ occupational characteristics of being primarily female. It should be noted that most of the research on career orientation has been conducted on males, and it has been suggested that if women were included, one might find that a higher percentage would be oriented toward the more affiliative, service types of career occupations because of women’s prior socialization to be more affiliative [9,33]. Additionally, it can be considered an important orientation that forms the attitudes and stances not only for PHNs but also for the general nursing profession.

The source of Stability Orientation rests primarily with stable membership in a given organization, including one that is geographically based and involves a feeling of settling down, stabilizing one’s family, and integrating

Table 3. Major factor analysis of PHN’s career orientation.

Continued

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. aMajor factor analysis by varimax rotation (n = 2003); bPearson’s correlation coefficients (n = 2003); cPearson’s correlation coefficients (n = 219).

oneself into the community [9]. One of the employment motives to be a PHN is to be an official government worker without restructuring and a full member of the welfare program with little overtime work [29,34]. The following issues need to be considered carefully: how to strike a good work-life balance and how to combine that balance with the other four orientations [35].

It may be important for people of Specialist Orientation to put a high value on task accomplishment, performing a job solely within their area [9]. This orientation could be considered a new manner of career development for PHNs.

In light of these results, these sub-scales can be perceived as reflecting the original characteristics of PHN activities.

4.3. Proposals for the Practical Use of the PHN Career-Orientation Scale

We propose the following two ways to utilize our results:

First, this scale will be a good self-analysis tool. The key to effective career management, as when coping with any life task, is to become a proactive and effective diagnostician, capable of identifying the problem, operating with a maximum of self-reflection, building a repertoire of possible responses, and knowing how to select the appropriate response [34,36].

Second, the scale can be utilized when checking the compatibility of a role and the seeker. The key to coping effectively is having clear insight into what one wants of a career and an understanding of one’s talents, limitations and values and of knowing how they will fit with the organizational values and the job request [37]. PHNs should seek responsible career counseling. They should talk to their supervisors, coworkers, friends and family and should cope with career development problems just as they would with any other life task [35,37,38].

4.4. Limitations of This Research and a Future View

In this study, the response rate was not high (less than 30%); therefore, it is hard to generalize the results. However, this is a nation-wide survey, and the demographic characteristics of the participants were quite similar to those of Japanese PHNs in terms of affiliated organization, department affiliation and years of service. More outcome-based research will be needed to clarify how the PHNs’ career orientation contributes to improvements in public health.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, we tried to develop a career-orientation scale for PHNs and examine the reliability and validity of that scale. We selected five orientation factors and 19 items. The cumulative contribution ratio was 46.9%, and Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was 0.863. The exact match ratio of test-retest was 59.7%. Therefore, the reliability and validity of this survey were confirmed. However, further research is required to test its reproducibility.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to all the PHNs who contributed time from their busy schedules to participate in this study. This article will be based on a part of study first reported in a Japanese journal of public health, 58(12), 1026-1039, 2011 (in Japanese). This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Health and Scientific Research Projects for fiscal years 2002–2004 and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research Projects, Young Researchers for the fiscal years 2007- 2009 from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Olovares-Tirado, P., Tamiya, N., Kashiwagi, M., et al. (2011) Predictors of the highest long-term care expenditures in Japan. BMC Health Service Research, 11, 103. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-103

- Yoshioka, K.K. (2008) Strategies for assessing the feasibility to develop new needs-oriented services by public health nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 16, 284- 290. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00782.x

- Lin, C.-J., Hsu, C.-H., Li, T.-C., et al. (2010) Measuring professional competency of public health nurses: Development of a scale and phychometric evaluation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 3161-3170. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03149.x

- Harrington, C., Crider, M.C., Benner, P.E., et al. (2005) Advanced nursing training in health policy: Designing and implementing a new program. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 6, 99-108. doi:10.1177/1527154405276070

- Saeki, K., Izumi, H., Uza, M., et al. (2007) Factors associated with the professional competencies of public health nurses employed by local government agencies in Japan. Public Health Nursing, 24, 449-157. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00655.x

- Gouldner, A.W. (1957) Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles 1. Administration Science Quarterly, 2, 281-306. doi:10.2307/2391000

- Gouldner, A.W. (1958) Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles 2. Administration Science Quarterly, 2, 444-480. doi:10.2307/2390795

- Kotter, J.P. (1985) Power and influence. Free Press, New York, 55-116.

- Schien, E.H. (1978) Career dynamics: Matching individual and organizational needs. Addison-Wesley, Massachusetts, 124-172.

- Schien, E.H. (1990) Career anchor: Discovering your real values. Jossey-Bass Inc., Pfeiffer, 3-64.

- Sovie, M.D. (1982) Fostering professional nursing careers in hospitals: The role of staff development, part 1. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 12, 5-10.

- Sovie, M.D. (1983) Fostering professional nursing careers in hospitals: The role of staff development, part 2. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 13, 30-33. doi:10.1097/00005110-198301000-00008

- Kleinknecht, M.K. and Hefferin, E.A. (1982) Assisting nurses toward professional growth: A career development model. Journal of Nursing Administration, 12, 30-36. doi:10.1097/00005110-198207000-00008

- Benner, P.E. (2001) From novice to expert; excellence and power in clinical nursing practice (Commemorative ed.). Prentice-Hall Inc., Upper Saddle River, 2-38.

- Toth, J. (2011) Development of the basic knowledge assessment tool for medical-surgical nursing (MED-SURG BKAT)© and implications for in-service educators and managers. Nursing Forum, 46, 110-116. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6198.2011.00216.x

- Godden, B. (2011) Orientation, competencies, skills fairs: Sorting it all out. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 26, 107-109. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2011.01.006

- Okura, M., Saeki, K., Omote, S., et al. (2006) Career orientation of public health nurses working in administrative agencies by qualitative research. Hokuriku Journal of Public Health, 32, 62-72. (in Japanese)

- Okura, M., Saeki, K. and Kido, T. (2006) Major structural factors of career orientation for public health nurses working in administrative agencies. Journal of the Tsuruma Health Science Medical Kanazawa University, 30, 11-21.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (2004) The number of full-time public health nurses working local administrative agencies in each prefecture. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/c-hoken/dl/data_0002.pdf

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication of Japan (2004) The number of changes of the number of cities, towns and villages in each prefecture. http://www.soumu.go.jp/gapei/

- Kaplan, R., Shmulevitz, C. and Raviv, D. (2009) Reaching the top: Career anchors and professional development in nursing. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 6, Article 24. doi:10.2202/1548-923X.1482

- Bester, C.L. and Mouton, T. (2006) Differences regarding job satisfaction and job involvement of psychologists with different dominant career anchors. Curationis, 29, 50-55. doi:10.4102/curationis.v29i3.1095

- Carmine, E.G. and Zeller, R.A. (1979) Reliability and validity assessment. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, 51.

- Denise, F.P. and Bernadette, P.H. (2003) Nursing research: Principles and methods. 6th Edition, JB Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, 309-359.

- Cohen, J. (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37. doi:10.1177/001316446002000104

- Rungtusanatham, M. (1998) Let’s not overlook content validity. Decision Line, 29, 10-13.

- Peterson, R.A. (1994) A meta-analysis of cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 381- 391. doi:10.1086/209405

- Polit, D.F. and Beck, C.T. (2004) Nursing research: Principles and methods. 7th Edition, Lippincott Williams & WIlkins, Philadelphia.

- Bloom, J.R., O’Reilly, C.A., III and Parlette, G.N. (1979) Changing images of professionalism: The case of public health nurse. American Journal of Public Health, 69, 43- 46. doi:10.2105/AJPH.69.1.43

- Jack, S.M. (2010) The role of public health in addressing child maltreatment in Canada. Chronic Diseases in Canada, 31, 39-44.

- Baker, M.W. and Heitkemper, M.M. (2005) The roles of nurses on inter-professional teams to combat elder mistreatment. Nursing Outlook, 53, 253-259. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2005.04.001

- Merkeley, K.K. and Fraser, A.D. (2008) Effective collaboration: The key to better healthcare. Nursing Leadership, 21, 51-61.

- Kopesky, J.W., Veach, P.M., Lian, F., et al. (2011) Where are the males? Gender differences in undergraduates’ interest in and perceptions of the genetic counseling profession. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 20, 341-354. doi:10.1007/s10897-011-9365-x

- Okura, M., Saeki, K., Ohno, M., et al. (2004) The image of the public health nurse that beginner public health nurses have at the time of employment: The career choice motive, and the image of the public health nurse. Journal of the Tsuruma Health Science Medical Kanazawa University, 28, 143-150.

- Baghban, I., Malekiha, M. and Fatehizadeh, M. (2010) The relationship between work-family conflict and the level of self-efficacy in female nurses in Alzahra Hospital. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 15, 190- 194.

- Lown, B.A., Newman, L.R. and Hatem, C.J. (2009) The personal and professional impact of a fellowship in medical education. Academic Medicine, 84, 1089-1097. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ad1635

- Miller, D.B. (1977) How to improve the performance and productivity of the knowledge worker. Organizational Dynamics, 5, 62-80. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(77)90031-6

- Ford, G.A. and Lippitt, G.L. (1976) Planning your future: A workbook for personal goal setting. University Associates, San Diego, 83-104.